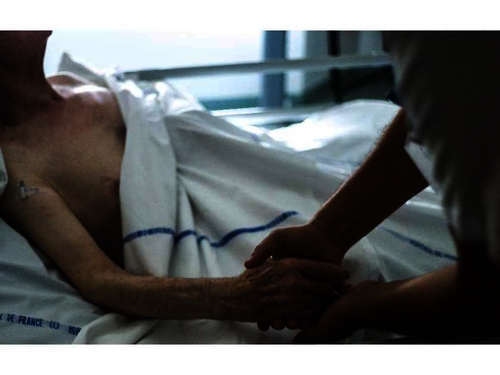

In Canada’s fragile discussions around end-of-life care, three statistics lie submerged in the rhetorical tension, dissension and fear. The first two numbers are from a 2013 Harris Decima Survey and a 2011 report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. They show, respectively, that 75 per cent of Canadians would prefer to die at home, and that 70 per cent of Canadians instead die in hospital. The third number is from a new Nanos Research poll commissioned by Cardus, which showed that 73 per cent of Canadians fear their end-of-life wishes will not be respected in whatever setting they pass their final days. A conclusion: Almost three-quarters of Canadians are not getting what they want from the care system set up to usher them over death’s threshold, and while living are denied peace of mind. This is no reflection on the skill and best intentions of those on the front lines or in the administrative roles of that system. Rather, as the Cardus report on re-framing the end of life conversation in Canada makes clear, it is a function of a system that has many overlapping, and frequently contrary, approaches and objectives. History is partly to blame. We are in a third “zig” of the zigzag that occurred during the 20th century. Through the 1930s, fewer than 30 per cent of Canadians died in hospital. By the 1950s, that had climbed to more than 50 per cent. A peak was reached in 1994 when 77 per cent of us breathed our last in a hospital bed. That was the apex of what can be called the medicalization of death. The end of life ceased to be a moment of passage, and became a test of medical perfectibility. Tools, technique and transfer of patients to ever more specialized hospital wards crowded out the family at the foot of the death bed at home. In part, economics and demographics made the move to medicalized death unsustainable. We are now living a return to older ways of saying last goodbyes. While the greying of the baby boomers, and the immense social cost of their boundless sense of entitlement, is a familiar story, something much more is behind the return to seeing death as a natural process. Modern medicine has provided us the means to mitigate much of the pain experienced at the end of life, and we can deliver it in homes and hospices as well as hospitals. Our challenge is that most health-care programs exist as stand-alone offerings rather than as a seamless continuum of care. Those confronting end-of-life issues require not only medical support from the health-care system, but emotional and spiritual support as well, including for caregivers. It’s critical to this continuum that caregivers be placed at the centre. Policy must be designed around their needs. That, in turn, requires a renewed understanding of natural death as a good and proper end of life dependent on the whole of our social architecture: family, local institutions, community in it fullest sense. Fittingly, hope for a successful transformation of our approach to death comes from what happened with life’s other inevitability: taxes. Starting in the mid-20th century, successive Canadian governments made incremental changes to the tax system to give Canadians greater control over their retirement savings. Such tools as public pensions and RRSPs became a common means to prepare for the future. They became a natural part of the continuum of conversation in Canada about life after work. Today, it’s time for a similar change in health care so Canadians have the power to plan early to ensure supports are in place to die a natural death.