The 2018 Cardus Education Survey (CES) marks nearly a decade’s worth of research into the effects of various school sectors on the academic, social, religious, and civic development of graduates in the United States. The Survey is now considered one of the most significant measures of nongovernment school outcomes. CES reports capture the views from a representative sample of 1,500 randomly selected American high school graduates ages twenty-four to thirty-nine who were asked to complete a thirty-five to forty-five-minute survey. The assessment comes at an important time—far enough away for these graduates to have had experiences in other educational institutions, in family and relationships, and in the workplace, and yet close enough to allow for some maturity, reflection, and recollection. The CES instrument includes a large number of controls for many factors in graduate development, such as parental education, religion, and income, in order to isolate a school sector’s particular impact (“the schooling effect”). 1 1 The 2018 CES respondents include 904 graduates who primarily attended public high school, 83 respondents who primarily attended non-religious private school, 303 graduates of a Catholic high school, 136 graduates of an evangelical Protestant school, and 124 who were homeschooled. In order to isolate the school effect for each of these sectors, the analysis includes a large number of control variables for basic demographics (gender, race and ethnicity, age and region of residence), family structure (not living with each biological parent for at least sixteen years, parents divorced or separated, not growing up with two biological parents), parent variables (educational level of mother and father figure, whether parents pushed the respondent academically, the extent to which the respondent felt close to each parent figure), and the religious tradition of parents when the respondent was growing up (mother or father was Catholic, conservative Protestant, conservative or traditional Catholic). A control was also included for the number of years a private school graduate spent in public school. Despite our efforts to construct a plausible control group, because families who send their children to religious schools or non-religious independent schools make a choice, they may differ from those who do not exercise school choice in unobservable ways that are therefore not accounted for in our study. Despite this, the CES use of an extensive survey instrument, together with its comprehensive application of control variables and resulting patterns of outcomes, assures us with some confidence of the accuracy of our school sectoral outcomes. Five smaller reports summarize the results of the 2018 survey. They focus on particular outcomes and themes of interest, including the following: (1) education and career pathways; (2) faith and spirituality; (3) civic, political, and community involvement and engagement; (4) social ties and relationships; and (5) perceptions of high school.

There seems to be increasing recognition of the value of faith, and of belonging to a faith community, especially in light of troubling trends related to depression and loneliness. There is also cause to believe that the sense of belonging offered by these communities of faith provide important conditions for human flourishing and the formation of virtuous citizens who can live alongside and love the “other.” Our data supports this view: religious affiliation has a number of positive effects that extend beyond the person and implicate the well-being of family life and society at large.

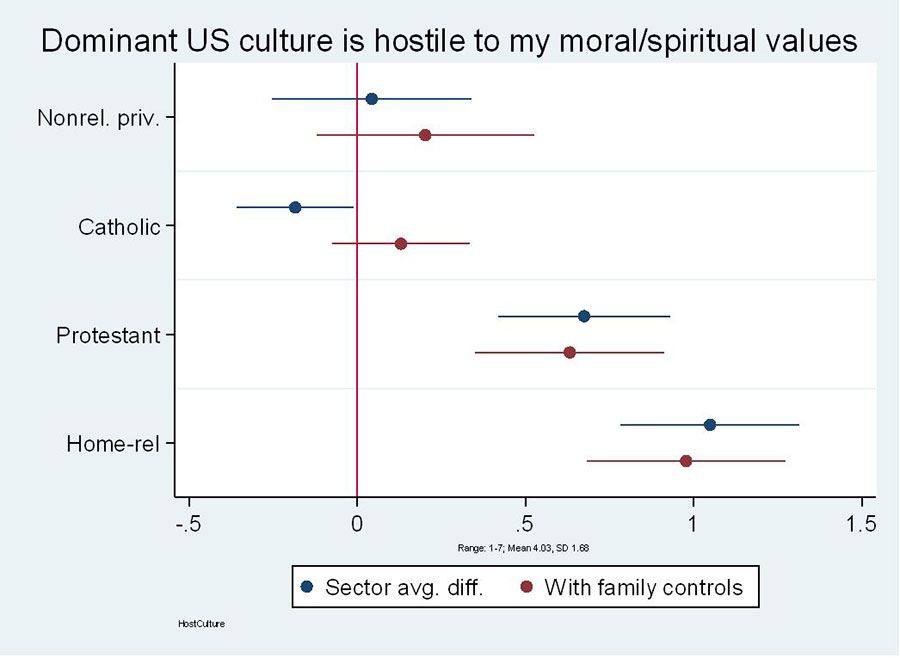

At the same time, there is recognition of the public perception that religion might negatively affect social cohesion. When religion creates inward-looking platoons that have little engagement with or tolerance for those with different views, there are potential implications for broader notions of citizenship, democracy, and the common good. In the present pluralist and globalized context, living a faith-filled life can provide much-needed rootedness, belonging, and meaning, but it must also lead to charity and love for thy neighbour. But at the same time, it is important to understand that this charity extends both ways: public narratives in the United States must also recognize and respect those with religious views. CES data findings show that Protestant school graduates and religious homeschool graduates are very likely to hold the view that the dominant culture in the United States is hostile to their moral and spiritual values, with religious homeschool graduates holding the strongest views on this measure. In fact, the average religious homeschooler is a full point higher than the average public school graduate on this measure.

Many parents choose religious schools in order to help with religious formation and to socialize students into religious practice and community. The 2018 CES asks graduates a series of questions on their religious views and practices in order to assess whether religious schools meet these expectations.

Religious Views

We would expect that religious schools foster spiritual formation, and that Protestant and homeschools are quite intentional in emphasizing the importance of orthodox religious views, as well as religious and spiritual practices. The 2018 CES data on religiosity supports this view.

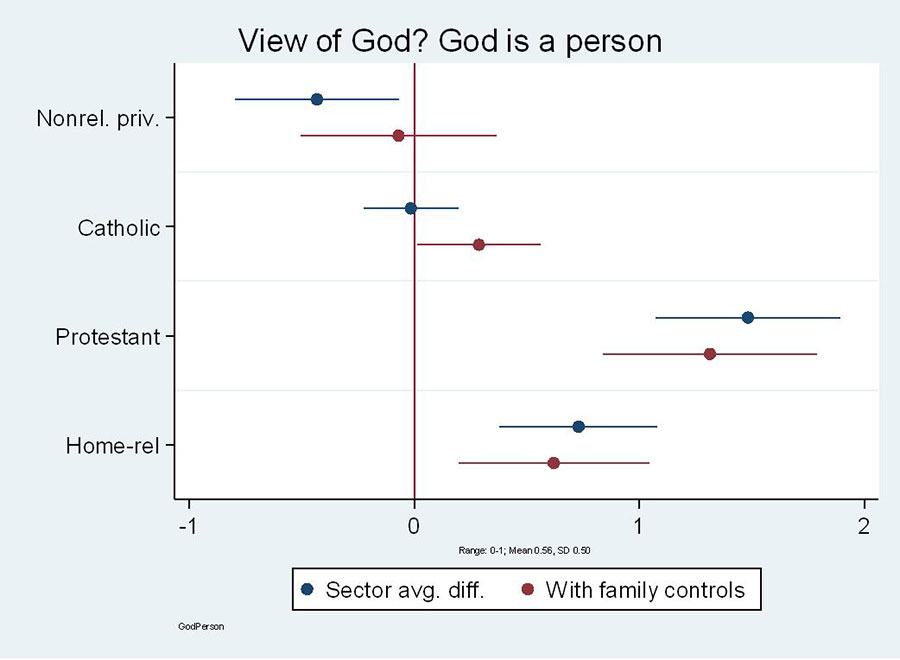

Protestant school graduates are at least four times more likely to view God as a person and demonstrate extremely high support for the infallibility of the Bible when compared to public school graduates. Religious homeschool graduates are about 1.8 times as likely to view God as a person as public school graduates, though this effect is somewhat lower than the Protestant school effect. Religious homeschool graduates are also more likely than public school graduates are to take up a sixday creationist perspective and view the Bible as infallible and without scientific or historical errors.

Catholic school graduates are likely to view God as a person, though this difference with public school graduates is not nearly as strong as for Protestant school graduates and only emerges when controlling for family background differences. It is worth noting that the Catholic-school-sector effect is significant here, as it increases the likelihood of holding these views despite a family background that on average leans toward viewing God as a life force or taking up an agnostic position.

Protestant school graduates and religious homeschool graduates are very likely to accept the authority of their church leadership. On this seven-point scale, they are over one-half a point higher on average compared to public school graduates. Catholic school graduates are slightly higher on this measure, but this effect is not statistically significant.

Spirituality

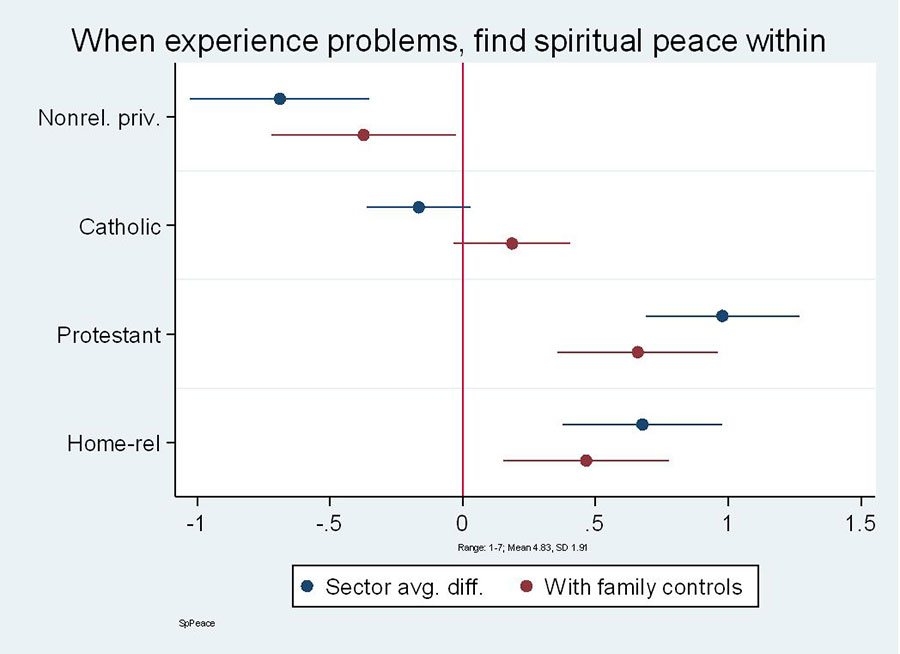

Protestant and religious homeschool graduates track quite closely on spirituality measures as well. Both groups agree on the sentiment that their spirituality brings a feeling of fulfillment as compared to public school graduates. Protestant school graduates are slightly higher on this scale, showing on average a half a point difference with the average public school graduate. A similar pattern of outcomes emerges when graduates were asked whether they can find spiritual peace within in the midst of problems and whether they experience a deep communion with God.

Slight differences emerge on other spirituality measures, however. For example, Protestant school graduates have very strong levels of agreement with the view that everything, including suffering, is part of God’s plan. Protestant school graduates are about .75 points higher on this seven-point scale than public school graduates are, after controls. Religious homeschool graduates are higher on this measure than public school graduates, but after controls this effect declines and is only marginally significant. On the question of religious doubts, the Protestant school graduates are much lower on average compared to public school graduates—nearly half a point lower on this seven-point scale. Religious homeschool graduates are lower as well, but this difference is not statistically significant after adding family background controls.

The Catholic school effects on spirituality are not strong but do show a slightly higher agreement with the statements on spiritual fulfillment, as well as slightly stronger agreement that they can find spiritual peace within when experiencing problems, and that they experience a deep communion with God as compared to public school graduates. Catholic school graduates are also more likely to say that they try to strengthen their relationship with God than public school graduates. But these graduates are not distinctive from public school graduates on the measure of whether everything that happens to them is part of God’s plan. Interestingly, the average Catholic school graduate is willing to entertain doubts about whether their religious beliefs are true, though this effect is relatively small in size and only marginally significant.

Gratitude and Sense of Purpose

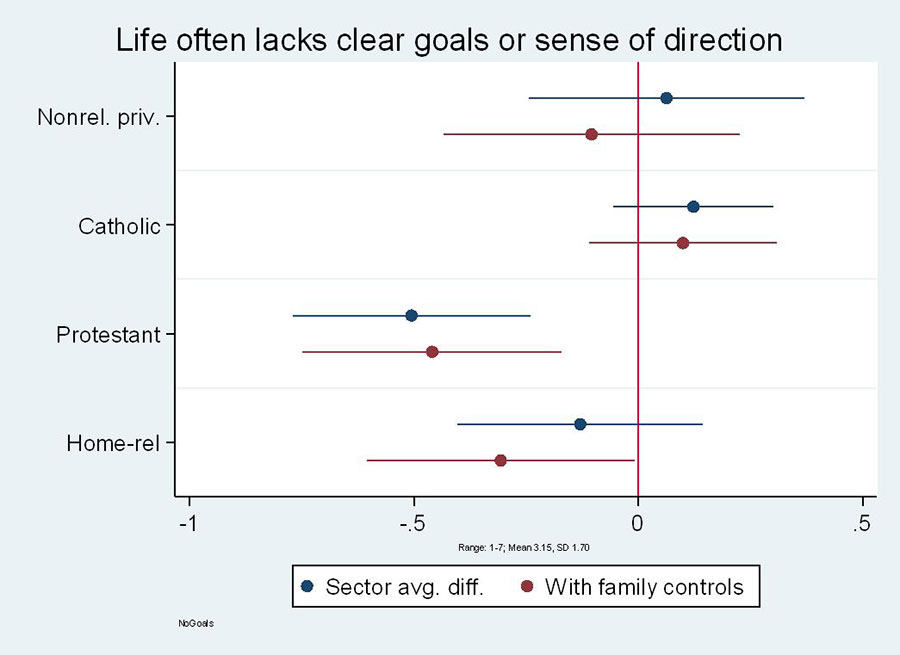

There is some evidence that religious schools have a positive impact on feelings of gratitude and purpose. Evangelical Protestant school graduates express higher levels of efficacy; they are less likely to feel helpless in dealing with life’s problems and also less likely to think that their life lacks clear goals or direction. About 37 percent of public school graduates compared to 48 percent of Protestant school graduates completely or mostly disagree that they feel helpless in dealing with life’s problems. About 54 percent of Protestant school graduates mostly or completely disagree that they lack clear goals or direction in life, while the comparable percentage for public school graduates is 43. The strength of the religious community, operating through the school but likely in combination with congregations, religious universities, and parachurch organizations, appears to increase efficacy for Protestant school graduates. Religious homeschool graduates would also not say that they lack clear goals and direction in life.

Feelings of gratitude can also be considered a measure of mental health. Interestingly, private non-religious school graduates and public school graduates express the same levels of gratitude. Both Protestant and homeschool graduates express higher levels of gratitude than do public school graduates. In the raw data, about 63 percent of Protestant school graduates completely agree that they have much to be thankful for, while 54 percent of public school graduates completely agree with this view.

Religiosity and Spiritual Practices

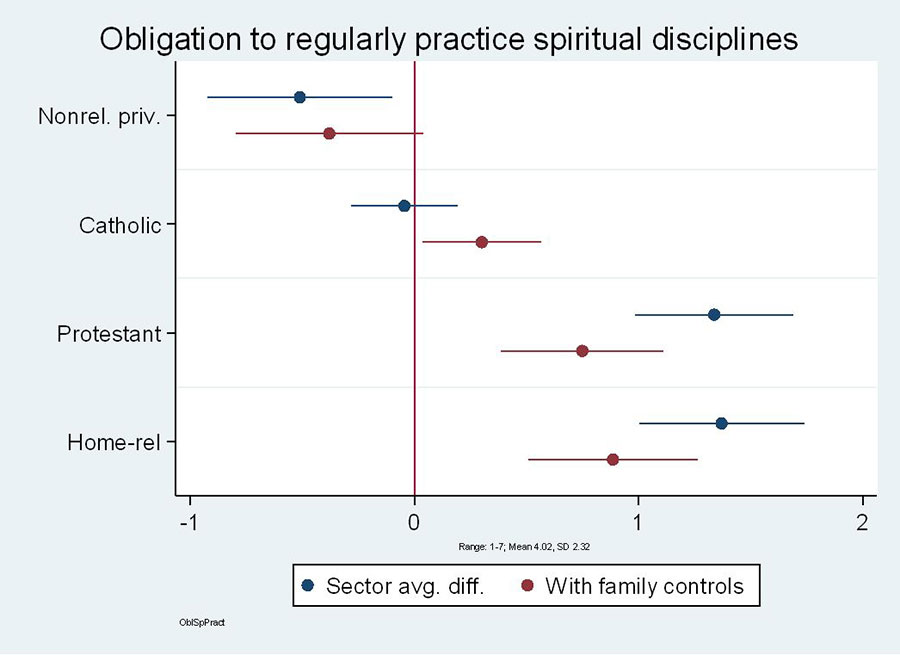

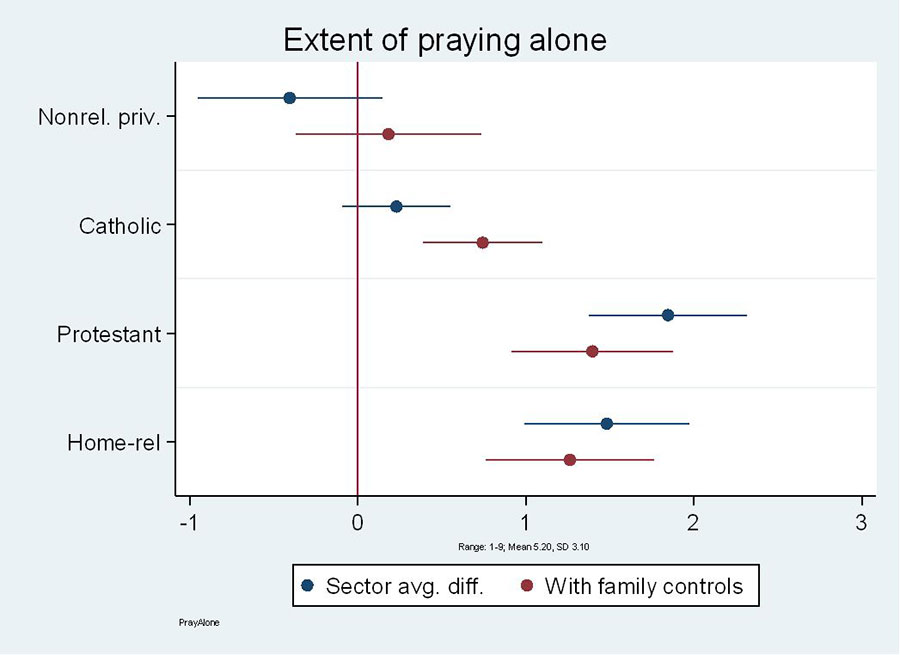

Protestant school graduates and religious homeschool graduates express high levels of agreement that they have a religious or moral obligation to regularly practice the spiritual disciplines, such as prayer or Bible reading. This is reflected in actual practice as well. The extent of personal prayer is much higher among Protestant school graduates than public school graduates—over a point and a half higher on average for this nine-point scale, which is over a half a standard deviation. The frequency of Bible reading is also much higher among Protestant school graduates. On a nine-point scale, Protestant school graduates are nearly a point and a half higher on average than public school graduates on this measure. The extent of reading other religious literature is also much higher among Protestant school graduates—about .75 points higher on this nine-point scale.

Protestant school graduates attend religious services at much higher rates than public school graduates. They are about a point higher on this eight-point scale, which would translate to, for example, an increase from three times a month to once a week. Protestant school graduates are regularly attending religious small group meetings, though this is not statistically significant after accounting for family background. Similarly, Protestant school graduates appear to be doing more evangelism than public school graduates, but this difference is explained by differences in family background.

Religious homeschool graduates are similar to Protestant school graduates in their frequency of personal prayer, which is very high relative to public school graduates. Religious homeschool graduates are also very high on the extent of Bible reading. Their frequency of reading “other religious literature” is also higher than the frequency for the average public school graduate, as is their frequency of attending religious services. They are also attending a higher number of small group meetings for spiritual support and discipleship and are more involved in evangelism than are public school graduates. Religious homeschool graduates are about half a point higher on this nine point scale of witnessing to friends or to strangers.

Catholic school graduates also tend to believe that they have an obligation to regularly practice spiritual disciplines, but this effect is not nearly as large as that for the Protestant school graduate. Catholic school graduates’ religiosity outcomes tend to trend in the same direction as other religious-school-sector outcomes but are not as pronounced when compared to public-school-graduate outcomes. For example, Catholic school graduates are about a half point higher than public school graduates on the extent of personal prayer and frequency of religious service attendance—a difference that is noteworthy though only about half as large as the Protestant-school graduate effect on this outcome.

The differences in graduate outcomes between public and non-religious private schools on these outcomes are muted. Non-religious private school graduates report less spiritual fulfillment and spiritual peace than public school graduates do. They are also less likely to report feeling an obligation for spiritual practice and less supportive of the authority of church leadership. Overall, however, the findings for non-religious private schooling are scattered and inconsistent. Most of the differences are not large, though perhaps show a tendency of lower engagement with religion and spirituality.

Perceptions of Preparedness for Religious Life and Religious Trajectory

The 2018 CES asks graduates for perceptions of how well high school prepared them for a vibrant religious and spiritual life. Protestant school graduates felt most strongly in agreement while Catholic and religious homeschool graduates are very similar on this measure. Non-religious private school graduates report higher levels of agreement with this outcome than do public school graduates but are lower on this measure than Catholic and religious private school graduates. When we analyze only those responses who believe they “were perfectly or very well prepared for a vibrant religious and spiritual life” (the two highest response categories versus all other responses), Protestant school graduates are over ten times more likely to agree with this than public school graduates.

It seems likely that these perceptions of preparedness for religious and spiritual life have some influence on a graduate’s religious trajectory. Here we see that religious tradition switching is less likely to occur among religious school graduates than public school graduates. Indeed, Protestant school graduates are very unlikely to take up a non-Christian religious tradition or to become nonreligious, and the odds that a Protestant school graduate would become non-religious or move into a non-Christian religion is at least 70 to 80 percent less than that of a public school graduate. In terms of religious identity, Protestant school graduates are more likely to take on the evangelical label, but this is accounted for by family background rather than school sector. They are also less likely to say that they are liberal Protestants, though this is only marginally significant.

Religious homeschool graduates are also less likely to become non-religious, though this is not statistically significant after controls. Interestingly, they are also no different from public school graduates in the likelihood of taking up a non-Christian religion. Religious homeschool graduates are also more likely to be evangelical, but this is not statistically significant after family controls are added, and they are less likely to adopt the “liberal Protestant” label.

Catholic school graduates are more likely to remain or become Catholic, but they are equally as likely to become non-Christian or non-religious as public school graduates.

Religious Giving and Service

In the raw data, Catholic school graduates are somewhat less likely to agree that they have an obligation to give 10 percent of their income to charitable causes. But what is interesting is that this negative effect is actually due to family background, which would often include Catholic parents. After controlling for family background, the findings for Catholic school graduates reveal that they are slightly more likely than public school graduates to believe that they have an obligation to tithe 10 percent of their income to charitable or religious organizations or causes. In this case, the Catholic school is having a generosity effect that counters the family effect. This difference with public school graduates is not large, but is statistically significant by a very small margin.

They are also more likely to contribute money or goods to their parish than public school graduates, but this is accounted for by their family background. Interestingly, they tend to donate less in terms of dollar amounts than public school graduates, but this is only marginally significant after controls. Catholic school graduates are, however, more likely than public school graduates to donate to other religious organizations or causes beyond their congregation. This effect is quite strong, and actually increases after controlling for family background differences. The odds that a Catholic school graduate will donate to a non-congregational religious organization or cause is over one and a half times that of a public school graduate.

Protestant school graduates also have a strong sense of obligation to tithe 10 percent of their income to religious or charitable causes. In terms of average levels of agreement with this obligation, Protestant school graduates are about .7 points higher on this seven-point scale than are public school graduates. Consistent with this, Protestant school graduates are also much more likely to make financial contributions to their congregations—indeed about 1.6 times as likely to give to their congregation than are public school graduates. Protestant school graduates are also more likely to donate to other religious organizations or causes—about one and a half times more likely to donate to these religious organizations than are public school graduates.

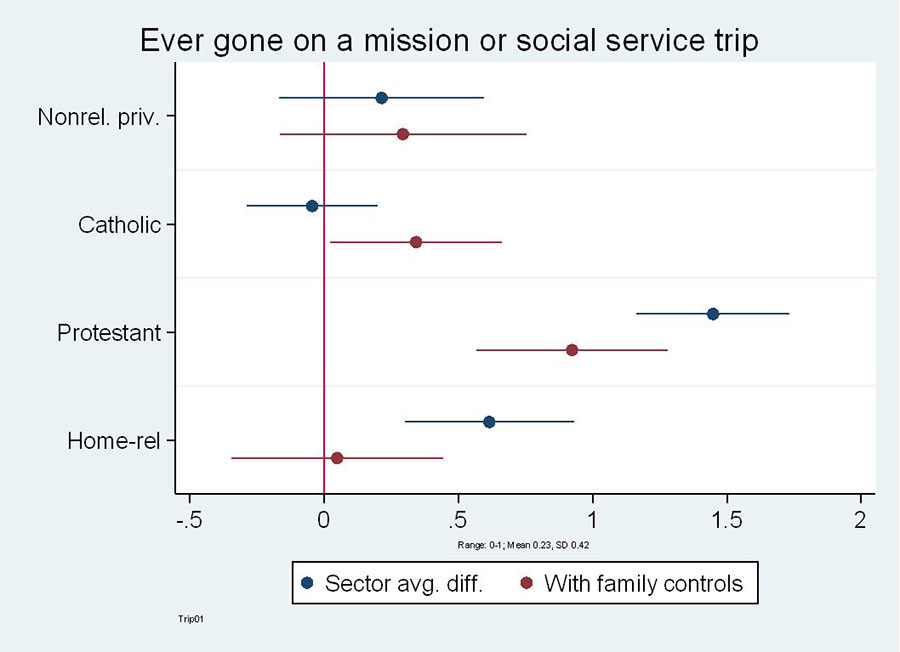

Missions and outreach trips are significantly higher among Protestant school graduates than public school graduates. In the raw data, 53 percent of the Protestant graduates have been on a mission or social service trip, while about 21 percent of public school graduates have done the same. The odds that a Protestant school graduate went on a mission or social-service trip that was primarily for evangelism is 4 times that of a public school graduate. Of course, Protestant school graduates are doing more trips overall, many of which involve evangelism but also relief and development. The Protestant school group averages 1.68 relief-and-development trips while the public school graduate averages .69 relief-and-development trips. When considering the proportion of all mission and social-service trips that is oriented to evangelism, we find no difference between Protestant school graduates and public school graduates. That is, once we take into account the total number of trips, Protestant school graduates are not more focused on evangelism than are public school graduates. Essentially, Protestant school graduates are more likely to do all kinds of mission and social-service trips, whether evangelistic or not.

Like Protestant school graduates, religious homeschool graduates are very likely to give to their congregation. These two sectors are comparable to one another and in their variation from public school graduates in terms of their likeliness to give to their congregation and the likelihood of giving to other, non-congregational religious organizations or causes. Religious homeschool graduates are much more likely to be found on a mission or social-service trip than public school graduates, but this is accounted for by family background differences. About 33 percent of religious homeschool graduates have gone on a mission or social-service trip, while the comparable figure for public school graduates is 21 percent.

Views of Marriage, Family, and Sexuality

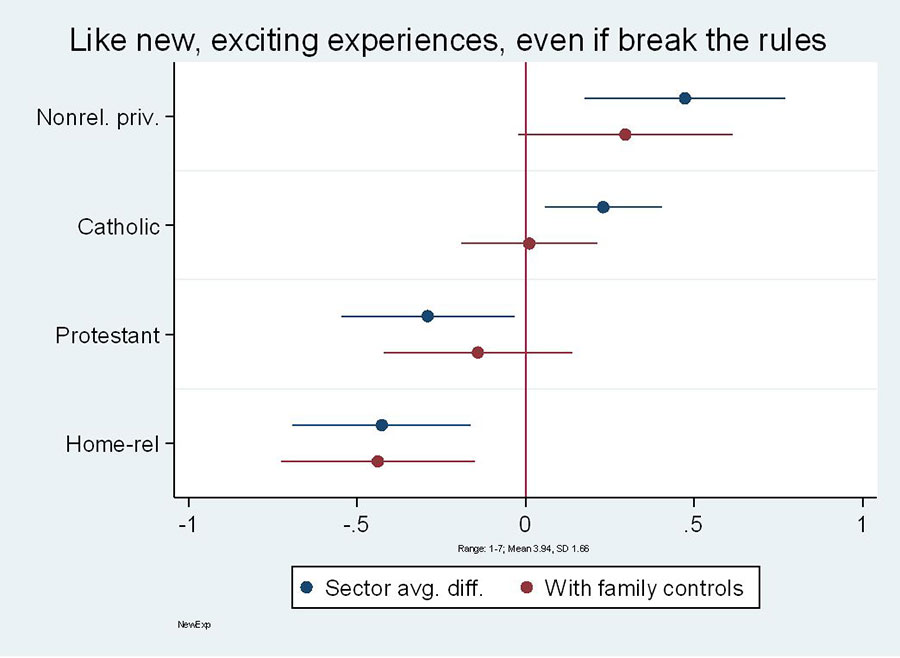

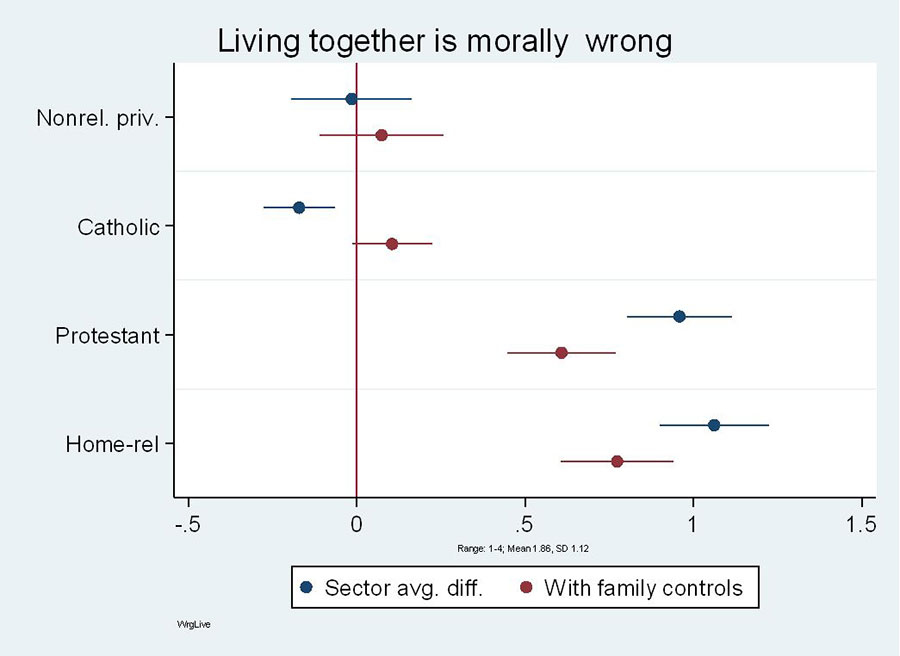

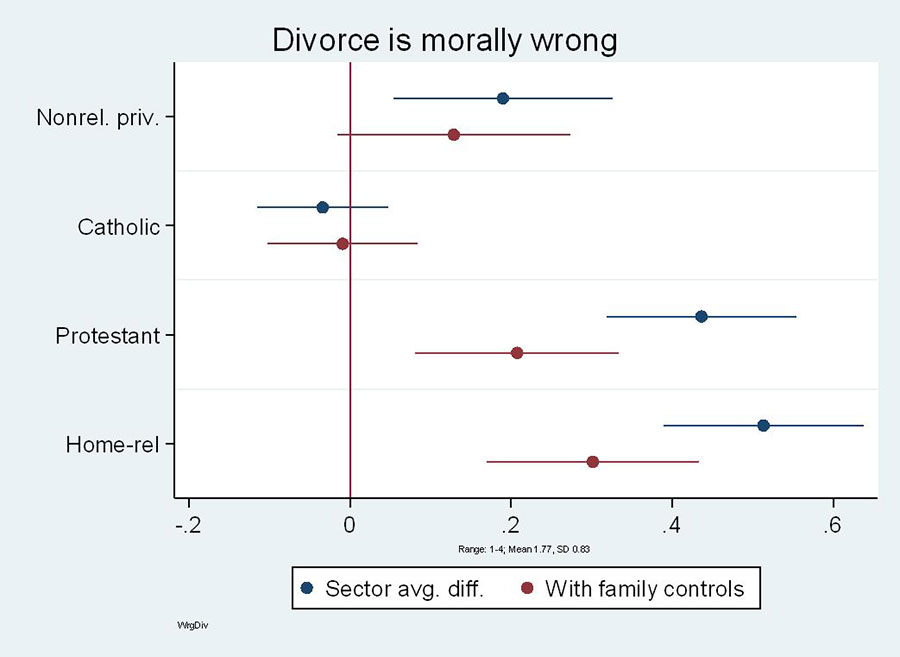

With regard to views on marriage, family, and sexuality, we would expect to find differences between public school graduates and religious school graduates, but we also find differences between Catholic and Protestant school graduates. Non-religious private school graduates are not particularly distinctive on the CES marriage and family measures. They are marginally significant in disapproving of divorce and gay marriage (as morally wrong). Catholic school graduates are somewhat different from public school graduates on their views of gender roles and are more supportive of a gendered division of labour (the man works, the woman cares for home and family), though this is only marginally significant. Catholic graduates are also more agreeable to a traditional gender ideology in which the wife gives-in to her husband when they disagree on a difficult decision. Catholic school graduates are not distinctive, however, from public school graduates on views of divorce or gay marriage, but are slightly more likely than public school graduates to say that cohabitation and premarital sex is morally wrong.

Protestant school and religious homeschool graduates are nearly identical on their views of traditional marriage and sexuality. They believe that living together, premarital sex, and gay marriage are morally wrong. On these four-point scales, Protestant school graduates are about half a point higher than public school graduates, which indicates greater support for the view that the behaviour is always or almost always morally wrong. On gender roles in the family, Protestant school graduates support the view that it is better if the man earns the living and the woman cares for the home and family. Differences between this sector and public school graduates are less sharp when asking whether the wife should give in to her husband if they have a disagreement about a major issue. Protestant school graduates are significantly higher than are public school graduates in favouring this view, though the effect is not as strong.

Conclusion

The 2018 CES asks graduates a series of questions designed to probe their views on religion and spirituality. Personal religiosity is very high among Protestant and religious homeschool graduates, with Protestant school graduates somewhat more consistent in promoting religiosity and spirituality among their graduates. In other words, these school sectors are certainly having a strong effect on the religiosity of their graduates, though when compared to earlier cohorts, the Protestant school effect does not seem quite as dramatic or consistent across all religiosity or spirituality measures.

Protestant school graduates are much less likely to stray from the Christian fold. Religious homeschool graduates follow a similar pattern, though with some slight variation. In the 2018 data, the Catholic school sector has a much smaller impact on the religion and spirituality of its graduates than the Protestant school sector, but differences from public school graduates appear to be more positive and consistent than we have seen for past cohorts. In some cases, the Catholic school sector seems to work toward the spiritual formation of its students even though their family background would push their graduates in a less religious direction. This is not surprising given that almost 20 percent of students in US Catholic schools are non-Catholic. 2 2 National Catholic Educational Association, “Enrollment,” https://www.ncea.org/NCEA/Proclaim/Catholic_School_Data/Enrollment_and_Staffing/NCEA/Proclaim/Catholic_School_Data/Enrollment_and_Staffing.aspx?hkey=84d498b0-08c2-4c29-8697-9903b35db89b.

As a final word, it is perhaps important to highlight the positive outcomes in terms of having feelings of gratitude and purpose. In the present cultural context of increasing depression, anxiety, and loneliness, the positive influence of religion school sectors on fostering feeling of gratitude, peace, and purpose should not be overlooked, and indeed deserves further research.