Is moving in together the purview of the young who are testing relationships? Not necessarily! Census data reveals that middle-aged Canadians are increasingly cohabiting. The portion of Canadians ages forty to fifty-four who cohabit has nearly doubled between 1996 and 2016.

Growing mid-life cohabitation is occurring as marriage continues its long decline. Some might consider marriage and cohabitation to be the same thing, but research shows cohabitation remains less stable, which has implications for Canadians as they age.

1

1

Dana Hamplová, Céline Le Bourdais, and Évelyne Lapierre-Adamcyk, “Is the Cohabitation–Marriage Gap in Money Pooling Universal?,” Journal of Marriage and Family 76, no. 5 (October 1, 2014): 983–97, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12138.

Cohabiters are less likely to pool financial resources that could have an impact on long-term financial planning. Another concern among Canadians moving from middle age into their senior years is caregiving and receiving care. A 2011 study suggests that cohabiting couples provide less care than married spouses do.

2

2

Claire M. Noël-Miller, “Partner Caregiving in Older Cohabiting Couples,” The Journals of Gerontology

Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 66B, no. 3 (May 2011): 341–53, https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr027.

Although middle-age cohabiters remain a minority in their cohort, the growth in cohabitation has been rapid and is an important trend to observe.

The 1996 census reported that 7.6 percent of 40 to 54 year olds lived in cohabiting relationships. That portion increased to 14.1 percent by the 2016 census. During the same period, the portion of married middle-aged Canadians declined from 69 percent to 58 percent (fig. 1).

3

3

Statistics Canada, “Marital Status (13), Age (16) and Sex (3) for the Population 15 Years and Over of Canada, Provinces and Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas, 1996 to 2016 Censuses—100% Data,” August 2, 2017,

http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?LANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=109650&PRID=10&PTYPE=109445&S=0&-SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2016&THEME=117&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=.

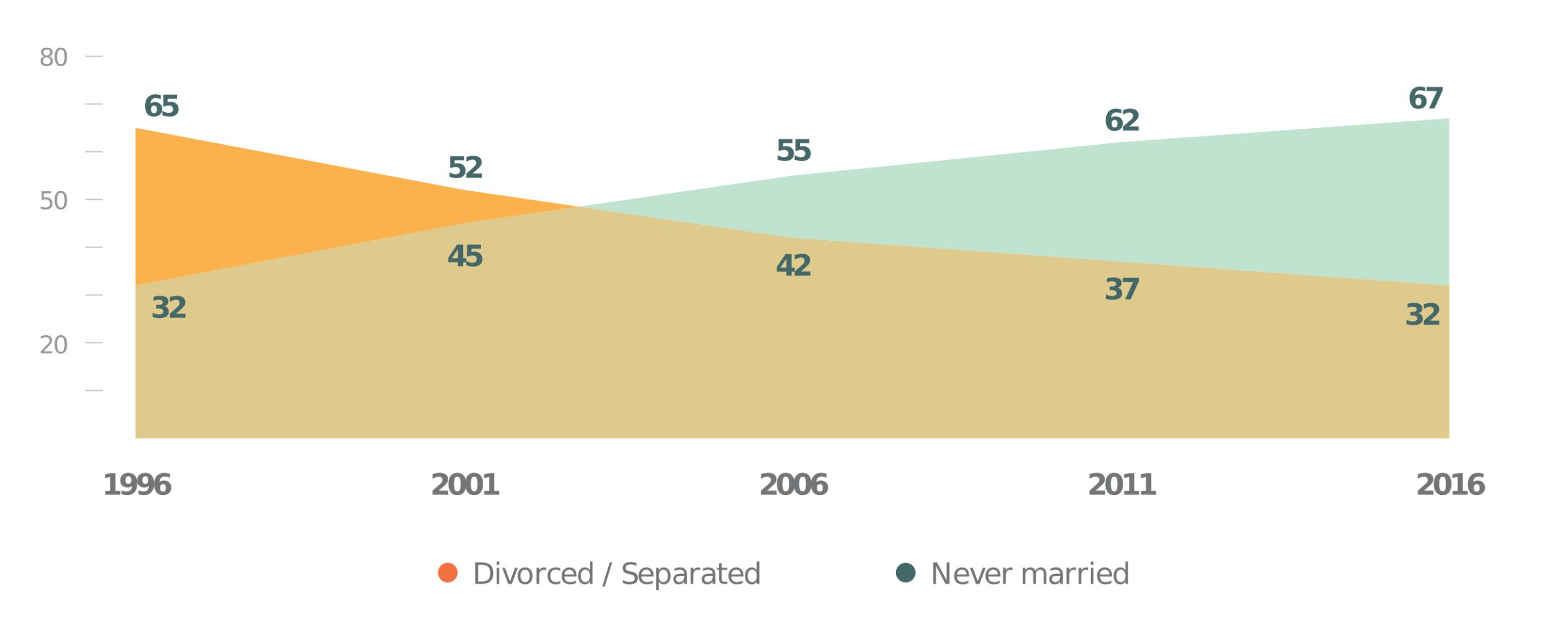

As the average age for divorce is in the mid-forties, observers might suspect that the growth in middle-age cohabitation is due to Canadians leaving marriages and moving in with new partners. In fact, the portion of middle-age cohabiters who were divorced or separated declined from nearly two-thirds to one-third of all mid-life cohabiters between 1996 and 2016 (fig. 2).

The majority of mi-life cohabiters have never been married. This represents a significant shift as the portion of never-married middle-age cohabiters more than doubled between 1996 and 2016, from 32 percent to 67 percent of all mid-life cohabiters. 4 4 Calculations by the author. Data source: Statistics Canada. Data tables, 2016 census.

A closer examination of divorced and separated cohabiters compared to all middle-aged Canadians reveals a slight increase between 1996 and 2001 followed by a sustained decline (not shown). The dramatic change in the portion of divorced/separated and never-married middle-age cohabiters shown in figure 2 is due in large part to the significant growth of never-married cohabiters.

This likely reflects current attitudes toward marriage. A 2018 Canadian survey suggested that among thirty-five to fifty-four-year-olds, about 56 percent do not think it is important for people planning to spend their lives to together to marry.

5

5

“‘I Don’t’: Four-in-Ten Canadian Adults Have Never Married, and Aren’t Sure They Want to,” Angus Reid

Institute (blog), May 6, 2018, http://angusreid.org/marriage-trends-canada/.

Other aspects of the survey show a decline in the importance of marriage for Canadians.

What might account for the increase in mid-life cohabitation and the portion of those who have never married?

Canadian public opinion data demonstrates growing ambivalence toward marriage across age cohorts. Focusing on mid-life Canadians ages thirty-five to fifty-four, about 56 percent agree that “marriage is simply not necessary” (fig. 3). While a majority of this cohort (56 percent) view marriage as a stronger commitment than cohabitation, they do not view marriage as essential, even when children are involved. 6 6 “‘I Don’t.’”

Certainly, cohabiting middle-age Canadians are a minority in their age cohort. Yet observing the growing trend is important and offers another opportunity to discuss important research on marriage and cohabitation.

Marriage is less prone to dissolution than cohabitation. About 56 percent of Canadians ages thirty-five to fifty-four agree that “marriage is a more genuine form of commitment than a common-law relationship.” 7 7 “‘I Don’t.’” Data on marriage shows this assumption to be true. The freedom to exit easily from a relationship means partners do leave more frequently.

Academics and policy-makers are paying more attention to the increasing number of Canadians living alone, and how informal networks and formal resources are important in caring for aging adults. In the same way, researchers are taking a look at the impact of “grey divorce.” An Environics analysis suggests Canadians age sixty-five and older who report being divorced has risen from 4 percent in 1981 to 12 percent by 2011. 8 8 David Macdonald, “Grey Divorce,” Environics Research (blog), accessed May 28, 2018, http://environicsresearch.com/insights/grey-divorce/. Both trends have implications for quality of life including financial well-being in the later years. The potential impact of increasing cohabitation should also be added to this concern. How might this influence financial planning as couples move toward retirement and contemplate future wealth transfers?

There has been rapid growth in cohabiting relationships among middle-age Canadians. The increase is likely to continue as Canadians display ambivalence toward marriage. Current research suggests that while marriage and cohabitation appear to be similar, they are distinct family structures with unique patterns. This trend is worth noting, particularly when considering the ways in which Canadians prepare for aging. Addressing the different economic and social realities of different relationship forms could be as important a planning measure as putting money away in an RRSP.