Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

The payday lending market in Canada is changing. Provinces across Canada have lowered interest rates and changed the rules for small-dollar loans. The goal of these policies is to protect consumers from unscrupulous lenders, and to minimize the risk of borrowers getting caught in the cycle of debt. What has worked, and what hasn’t? In this paper, Cardus continues its multi-year study of the payday loan market in Canada and evaluates which policies are working, which are not, and what yet remains unknown about payday loans, consumer behaviour, and the impact of government regulation on the supply and demand for small-dollar loans. Our study shows that many of our earlier predictions—including concerns about the disappearance of credit options for those on the margins—have come true. It also shows that alternatives to payday lending from community financial institutions and credit unions have largely failed to materialize, leaving consumers with fewer options overall. We also comment on the social nature of finance, and make recommendations for governments to better track and measure the financial and social outcomes of consumer protection policy.

Introduction

The payday lending market in Canada operates in a much different regulatory environment today, in 2019, than it did in 2016, when Cardus published a major policy paper on the subject. That paper, “Banking on the Margins,” provided a history of payday loan markets in Canada; a profile of consumers who use payday loans and how they are used; an analysis of the market of payday loan providers; an exploration of the legal and regulatory environment that governs borrowing and lending; and recommendations for government, the financial sector, and civil society to build a small-dollar loan market that enables consumers rather than hampering their upward economic mobility.

That paper, alongside other contributions from the financial sector, consumer advocacy groups, academics, and other civil society associations, contributed to major legislative and regulatory revisions to the small-dollar credit markets in provinces across Canada, including those in Alberta and Ontario. These two provinces in particular have set the tone for legislative change from coast to coast.

Cardus’s work on payday lending consisted of a variety of measures, ranging from major research papers to policy briefs and testimony at legislative committees.

Legislation aimed at protecting consumers of payday loans and making small-dollar loans more affordable passed in Alberta in 2016, and in Ontario in 2017. These legislative changes lowered the fees and interest rates that lenders could charge for small-dollar loans. New legislation also introduced a series of changes related to repayment terms, disclosure requirements, and other matters. Cardus offered an initial evaluation of those changes in 2018, and marked the various aspects of those changes for their likely effectiveness at achieving our desired goals. Cardus research suggested that the optimal result of payday legislation and regulation is a credit market that ensures a balance between access to credit for those who needed it most (which in turn assumes the financial viability of offering those products), and credit products that don’t leave customers in a situation of indebtedness that prevents upward economic mobility. We gave government policy a grade for each of the policy areas that were covered by the legislation and offered insight based on our research paper on how these changes would work out in the market.

The purpose of this paper is to turn the lens toward our own evaluations. Our research attempts to provide a dispassionate analysis of the literature and research on payday loans from within a clearly articulated set of principles, and to make recommendations that emerge from those.

What you will find below is a grading of our grading—where were our assumptions and reading of the data correct? Where have the data shown us to be wrong? What have we learned about the small-dollar loan market, the capacities of the financial and civil society sectors, and government intervention in markets? What gaps remain in our knowledge? Are there any lessons for policy-makers and researchers? How might our conversations about payday lending, markets, and human behaviour change as a result of this work? Read on to find out.

Data Sources

Our evaluation of the new legislation and regulations put in place by Alberta and Ontario was based on our research of available data and academic analysis related to payday lending read against data from the government of Alberta’s 2017 Aggregated Payday Loan Report, data gathered from Ontario’s Payday Lending and Debt Recovery section at Consumer Protection Ontario, which is within the Ministry of Government and Consumer Services, and from personal conversations with officials from the business associations representing payday lenders.

Where We Were Right

Municipal Bylaw Analysis

Grade: D

We were correct in our concerns about the provincial government’s devolution of regulatory power to municipalities. Ontario’s legislation gave municipalities the ability to use zoning bylaws to “define the area of the municipality in which a payday loan establishment may or may not operate and limit the number of payday loan establishments.” We gave this measure a D grade, citing concerns about the way in which municipal policies might unintentionally limit consumer choices and contribute to the development of monopolistic tendencies in municipal markets. We noted,

Forbidding shops from being placed next to homes for people with mental illness, for instance, would be positive. But in general, cities should try to avoid acting in ways that encourage negative unintended consequences. The recent move by the City of Hamilton to allow only one lender per ward is a classic example of this. It puts far too much focus on lenders, while leaving borrowers

with less choice and effectively giving existing lenders a local monopoly.

Our concerns about the spread of Hamilton’s policies spreading further were validated when the City of Toronto adopted a policy that limited “the number of licences granted by the City to 212. . . . [And] the number of locations where an operator is permitted to operate is limited to the total number of locations that existed in each ward as of May 1, 2018.” 1 1 “Payday Loan Establishments,” City of Toronto, https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/permits-licences-bylaws/payday-loan-establishments/.

Data from Ontario’s Payday Lending and Debt Recovery section at Consumer Protection Ontario show that five municipalities—Hamilton, Toronto, Kingston, Kitchener, and Chatham-Kent—have instituted such policies, all of which have focused on strict limits on the numbers of payday lenders, and which have grandfathered existing payday lenders.

Our research shows that two other municipalities—Sault Ste. Marie and Brantford— have considered such bylaws, and that Brantford alone has considered the ideal policy of using zoning powers as a means of preventing lenders from setting up shop close to vulnerable populations.

Our report card gave this regulation a D grade mainly due to concerns about municipalities failing to attend to the unintended consequences of these policies, and the introduction of regulatory redundancies.

It seems that our concerns were valid. Two of Ontario’s largest municipalities—Hamilton and Toronto—adopted policies that created an oligopoly for small-dollar loans. Existing payday loan locations now have an almost permanent, government-protected, and enforced oligopoly on payday loan services. Competitors who might have offered lower prices or better services to consumers are now forbidden from opening, giving incumbents—many of whom are associated with larger corporations—a huge advantage at the cost of consumer choice. And municipalities also opted to duplicate advertising and disclosure regulations that were already required by provincial regulation. It is a classic case of a government’s preferring to be seen to do something to give the aura of effective action, even if that action is suboptimal, or damaging to its citizens, and absent any evidence, let alone clear evidence of the efficacy of their policies. Recall that the policy goal of these regulations is to protect consumers while enabling access to credit. But the policies enacted by Hamilton and Toronto uses the power of government to privilege existing, big-business lenders, while limiting the availability of credit.

Interest Rate Caps

Grade: D

What the government did:

Both Alberta and Ontario made significant reductions to the interest rates between 2015 and 2018. The most substantial change to payday lending regulations in Ontario has been a reduction in the interest rate that payday lenders are allowed to charge. 2 2 Brian Dijkema, “Payday Loan Regulations: A Horse Race Between Red Tape and Innovation,” January 11, 2018, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/payday-loan-regulations-a-horse-race-between-red-tape-and-innovation/. This drop was substantial, going from $21 per $100 borrowed (in 2015) to $15 per $100 (in 2018). 3 3 Dijkema, “Payday Loan Regulations.” Expressed as an annual percentage rate, this means a drop from 766.5 percent APR to a new cost of 547.5 percent APR. Like Ontario, Alberta’s interest rate cap fell to $15 on a $100 dollar loan; however, unlike Ontario, which lowered from $21 per $100, Alberta lowered from $23 per $100. This means that they went from an annual percentage rate of 839.5 percent to one of 547.5 percent.

Cardus gave this policy intervention a failing grade: F.

Our report card noted that “reduced rates are the activists’ darling, but research shows that if you need to borrow $300 for ten days to buy necessities and pay bills, its effect is limited or negative.” Our testimony to the government committee’s reviewing the legislation noted that

it is the short-term nature of payday loans that puts the heaviest pressure on borrowers. The current average term of a payday loan in Ontario is 10 days, and it is the requirement to repay both the principal and interest at once that does the most damage to consumers. As we note, this “effectively moves the burden of illiquidity from one pay period to the next” (33) and moves the cash-flow challenged consumer into a position where they run the risk of terminal dependency on small loans.

In real life, the challenge with payday loans is less the cost of borrowing itself (though it is expensive compared with other forms of credit) and more the requirement that it be paid back all at once. People use payday loans not because they don’t have any money—you can only get a loan if you have a paycheque—it’s that they don’t have enough money on a given day. The changes in legislation lower the costs slightly (what you owe on a $300 loan went from being $363 to $345, a difference of $18) but still require most borrowers to pay it all back at once (FIGURE 1). If the reason you took the loan in the first place was that you were $300 short, the savings of $18, while significant, is not enough to prevent a secondary cash-flow crunch and the need for a second, third, or even fourth loan.

Moreover, we showed, using publicly available financial data from payday loan firms, that the $15/$100 rate would put significant pressure on the availability of credit, particularly for firms that did not have the capital backing to adjust their business structures. We noted that the reduced rate

would make firm[s] unprofitable if they maintained their current structure. . . . It is possible that such changes would force the industry to re-evaluate its current business structure. But, as we note, the bulk of the costs of providing payday loans (approximately 75 percent) are the result of the costs of overhead, including physical infrastructure and staff. If this is put against behavioural studies of payday loan borrowers—many of whom consider the physical presence of lenders an important reason for transacting with them—it’s possible that the ability of firms to adopt different cost structures is limited.

Our final word before our grade noted that “the supply of loans is likely to dry up, leaving consumers dependent on more expensive options, or lead to the growth of illegal loan-sharking. Even if some lenders adapt, which is entirely possible, it is a risk, and the new cap is likely to mean less choice for consumers.”

Who was right? While there are some qualifications and reservations, we can note that Cardus was more right than wrong in giving the government a failing grade on this intervention.

Ideally, we would have a broad suite of data on consumer behaviour that would allow us to determine the effect of these policies on actual consumers. Unfortunately, however, this data is unavailable or its collection is unfeasible. But there are data that suggest that the interest-rate changes have had a significant impact on the market, and by implication, on consumers.

Reports note a reduction in licensed payday lenders of almost 30 percent, from 230 stores in 2015 to 165 in January of 2018, and that one of the major providers—Cash Money—has ceased offering payday loans altogether. 4 4 Juris Graney, “Stricter Rules Force Closure of Alberta Payday Lending Stores, Says Industry Boss,” Edmonton Journal, January 14, 2018, https://edmontonjournal.com/news/politics/stricter-rules-force-closure-of-alberta-payday-lending-stores-says-industry-boss.

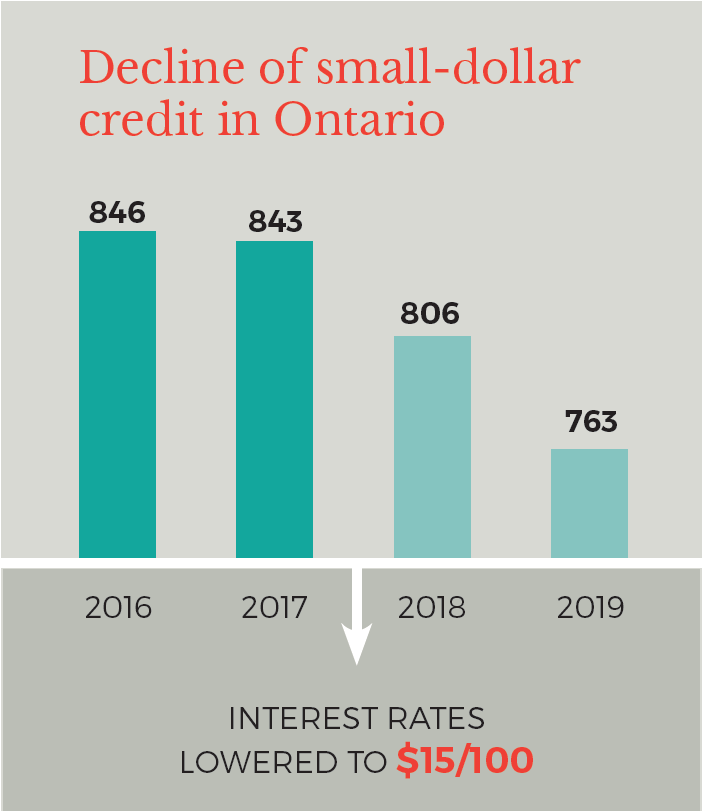

Ontario saw a significant reduction in licensed payday lenders as well, though not as marked as Alberta. Prior to the legislation being enacted in 2017, Ontario had 846 payday lenders. As of December 31, 2018, Ontario has 763 payday lenders, a loss of about 10 percent of the market (FIGURE 2).

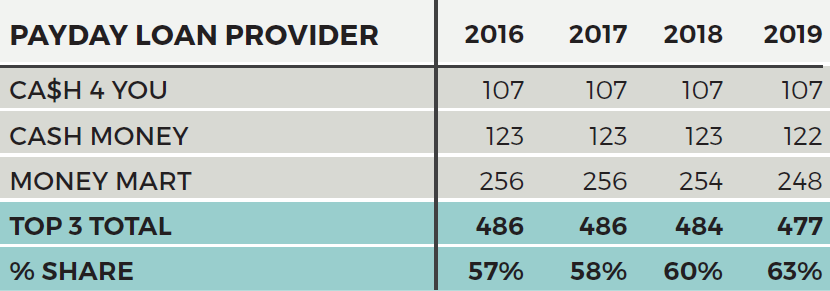

What is particularly notable about Ontario is that almost the entire loss was borne by independent payday loan stores. Our original research paper noted two major providers—Money Mart and Cash Money—made up approximately 50 percent of the Canadian market, with independent small operators making up approximately 35 percent of the market. In 2016 in Ontario, three lenders—Money Mart, Cash Money, and CA$H 4 You—made up approximately 57 percent of the total market. At the beginning of January 2019, the top three players represented 63 percent of the market (FIGURE 3).

The data show that losses were sustained almost entirely by independent firms who had one shop in operation.

Conversations with government officials and payday loan association representatives suggest that larger firms with greater access to capital and other structural advantages were able to restructure their businesses to take advantage of other revenue streams (such as term loans, on which more below) and maintain their business on products other than payday loans, while smaller firms who lacked these advantages could no longer operate profitably and had to shut down.

The vast bulk of payday loans in Ontario in 2016 were “in person” versus “remote” (which we understand to mean loans from licensed online lenders). Of the over 2.1 million payday loans taken by Ontario consumers in 2016, 93 percent of those were made in person. While Alberta did not report the percentage of loans that were taken in person versus online, the data we were able to attain from Ontario suggests that the vast, vast majority of licensees in Ontario are storefronts rather than online lenders. The ability of online lenders (whose overhead costs are potentially lower) to make up for the loss of storefronts will be a matter to watch. In any case, the loss of a significant portion of payday lenders suggests that our concerns about significant reductions in interest rates were valid; providers responded to the new rules in ways that are in line with normal economic behaviour. Some lenders have been able to adapt and restructure their businesses, but overall, there is no doubt that consumers have less choice for small-dollar loans as a result of the legislative changes.

Analytical Challenges with the Payday Lending Market

The challenge with much of the emphasis on these policies is that they place the bulk of the emphasis on providers. Do we know if this shrinking of payday loans is a net shrinking of available credit? How might we test whether our concerns about “leaving consumers dependent on more expensive options, or . . . growth of illegal loan-sharking” are valid?

Sadly, we do not have data that will allow us to readily ascertain whether there has been a growth in violations of the federal usury act, or if there have been charges related to violations of the provincial acts related to payday lending. Thus, at this point, it is not possible to say whether the decline in the market has led consumers to take loans that use violence as collateral. Likewise bankruptcy data do not provide any clear indication of an effect negative or positive from changes in payday lending legislation without significantly more statistical refinement.

The data available from Ontario related to customer complaints suggest that while there has been a 125 percent increase in complaints (from 8 in 2016 to 18 in 2018), the actual number of complaints relative to the number of loans was minimal. By way of comparison, the ratio of complaints to loans in 2016 was 8:2,101,486. Thus, even with the significant increase in complaints the total number remains almost negligible. An analysis of the violations that arose from inspections in Ontario also suggest that, on the whole, there is no indication of a widespread culture of malfeasance in lending in Ontario.

Whereas the typical advertisement might have said “Borrow up to $1,500 instantly” or “First $200 cash advance, free,” the new advertisements are more likely to say “Borrow up to $15,000. For big changes.”

But have the changes left consumers dependent on the more expensive options that we outlined in our original paper?

Again, the granular data required to make that judgment is unavailable. There is some indication (drawn from conversations with payday loan associations and government officials) that payday loan providers have shifted their business structures away from payday lending and toward term loans that offer lower rates and longer terms, though on larger amounts, and that are a subset of the more traditional lending market. Whereas the typical advertisement might have said “Borrow up to $1,500 instantly” or “First $200 cash advance, free,” the new advertisements are more likely to say “Borrow up to 15,000. For big changes.”

The longer-term loans are likely to have a lower per-dollar cost for the consumer and, when offered as a line of credit, offer significant flexibility. Yet, as they require a credit check, the ability of customers in greater short-term need to gain access to these products is likely to be curtailed. As we noted in “Banking on the Margins”, “The fact that payday lenders do not [perform credit checks or] report to credit bureaus is a double edged sword. The lack of reporting lowers the risk for the borrower and eases the consumers’ ability to access needed cash. But reporting to credit agencies also has both potential benefits and losses to the consumers.” 5 5 Brian Dijkema and Rhys McKendry, “Banking on the Margins,” February 22, 2016, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/banking-on-the-margins/. In this case, the benefit of being outside of the credit rating system that came with payday loans is likely also being curtailed. All of these challenges lead to a number of recommendations, which will be discussed below. But before we discuss those recommendations, we should own up to areas where our analysis was overly optimistic.

Where We Were Wrong

Grade: A++

Both our original report and our report card suggested that alternative products which leveraged either civil society or technology to provide lower-cost loans had significant potential to change the market. In Ontario’s case, we gave the government an A++ for completely deregulating credit unions looking to offer payday loans. We noted the following:

The single biggest problem [in the small-dollar credit market] is that demand for loans is steady, but there is a lack of a supply of positive alternatives. Freeing credit unions—which are obligated to benefit their members and their communities—gives them space to try new things and to offer new products. We have already seen a few Ontario credit unions move to offer alternatives, but this will encourage them to try more.

Likewise, Alberta, recognizing the importance of alternative products from community banking organizations in addressing the challenges related to payday lending, included measurements of alternative products in its legislation.

In Cardus’s analysis, we believed that the failure or success of the legislation would ride on the ability of credit unions to use their new freedom to build products that could compete with payday loans. Our report card noted that the legislation started a “horse race between red tape and innovation.”

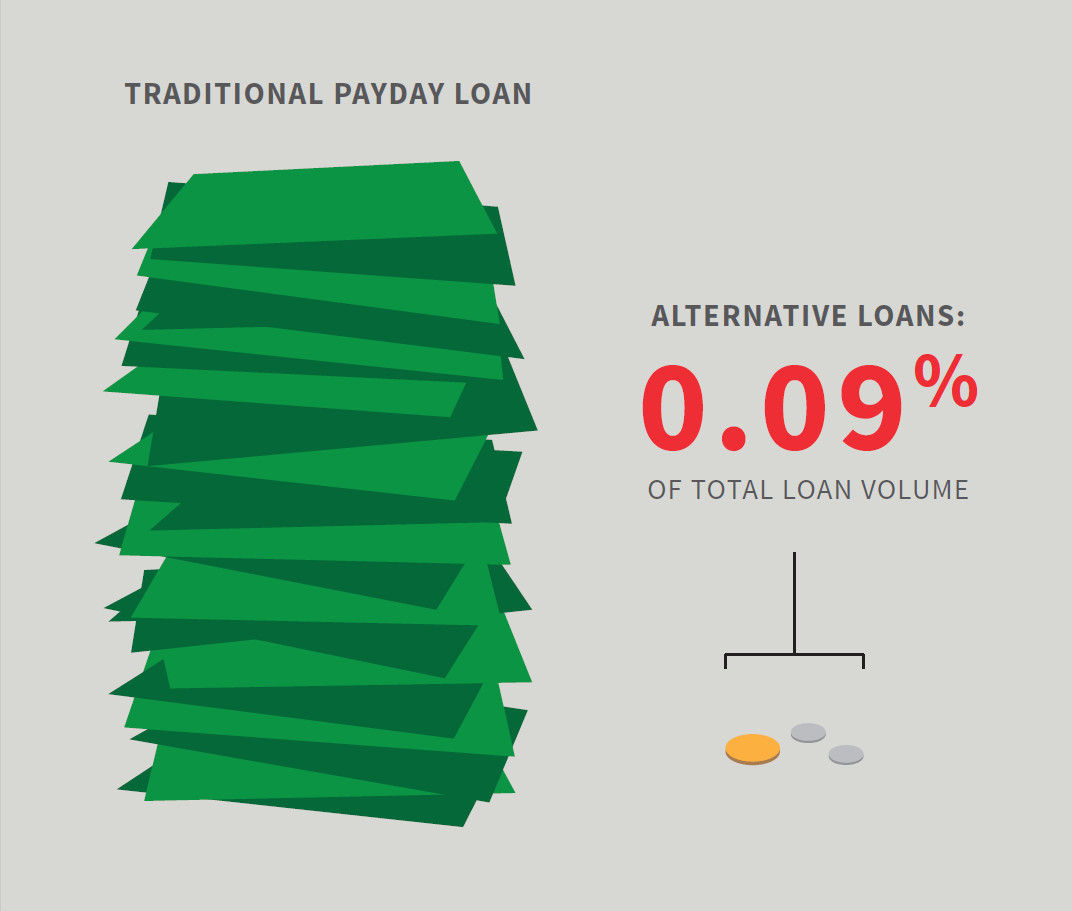

Well, the horse race is over. It wasn’t even close. The race between regulation and innovation saw the innovation horse stumble and shy almost from the starting line. Alberta’s payday loan report notes that only two credit unions—Connect First Credit Union, and Servus Credit Union—had competitive products on the market. And both total number of loans and volume of these loans were negligible in Alberta’s payday lending market. How negligible?

The total number of alternative loans amounted to just 0.04 percent of all loans in Alberta, and .09 percent of total loan volume (FIGURE 4).

While Ontario does not publish data on alternatives offered by credit unions, there are no indications to suggest that its credit unions have made any significant inroads whatsoever into the broader market, despite innovations at places like Windsor Family Credit Union and their “Smarter Cash” alternative. Other alternatives, like that initiated by the Causeway Work Center through its Causeway Community Finance Fund (in partnership with Alterna Savings, Frontline Credit Union, and YOUR Credit Union), have sputtered and are now shut down.

Likewise, while there are some promising lending alternatives in the FinTech world, they have not made any significant inroads into the payday loan market, opting to focus on disrupting the lower end of traditional lending markets. MOGO, for instance, began 2016 with five payday loan licenses and are now entirely out of the business.

Those who were betting on the innovation horse to change the market have lost their bet, and their horse is at the glue factory. However, the fact that there are few credit unions and other financial institutions offering alternatives does not negate the fact that the opportunity for alternatives still exists. Institutions motivated by a combination of economic and social ends may yet provide meaningful, easily accessible alternatives to members of their communities.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations for Next Steps

Report cards and evaluations are fun exercises—everyone loves a shiny A, and the schadenfreude of a bright red F is enjoyable too—but unless the evaluations facilitate greater learning and understanding, they amount to little more than hot air. So what lessons can we learn from this? A look back at both the actions of the government and the way that consumers and industry have reacted offer three matters for consideration.

Power, Profit, Principles, and Policy Can Be Strange Bedfellows

One of the starkest lessons from this exercise is how significant a role government regulation plays in markets. There is a very clear indication that government intervention— the setting of the rules in which firms can operate—affects not just business structures, but actual products offered to customers. The significant decline in payday lending firms shows that, at the end of the day, firms will simply not operate if the way in which they make profits is made illegal. This shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone, but it should serve as a reminder to policy-makers that their policies aren’t just for show. They have real effects.

Equally notable is that government policy combined with firm-level profit motives can result in unique, industry-wide financial adjustments. The anticipated massive shift of major payday lenders away from payday lending toward term loans shows that firms can be more flexible than one might imagine.

Finally, principled policy, without a broader cultural understanding of the moral dimensions of finance, is likely to have little effect. The broad failure of credit unions to offer products that provide long-term alternatives to people shows that even those who agree that offering lower-cost loans to those in desperate situations aren’t always able to put their money where their mouths are. The implications of this are complicated: it may represent a moral failure—a type of economic hypocrisy—but it may also point to the possibility that an equilibrium found in a free market represents a certain balance in which even people of goodwill can offer a product that, while seemingly morally troublesome, is the best that can be done at a given time.

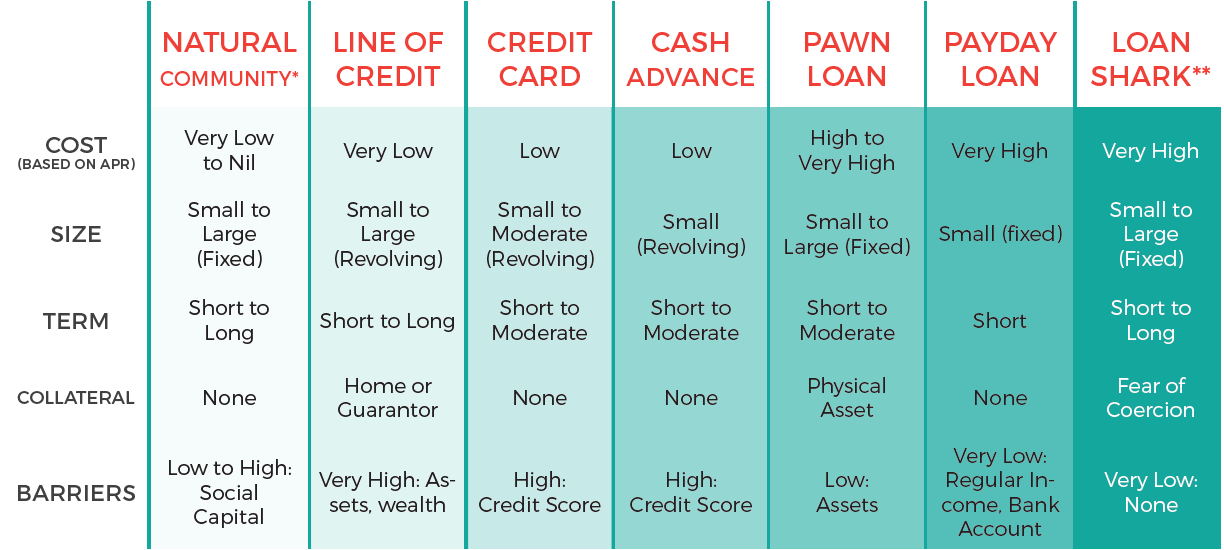

It is likely that this latter implication is true if it is assumed that the best we can do takes place within an institutional setting marked by the impersonal and transactional and a minimization of transaction costs. As we noted in our original paper, the best loans for borrowers are loans taken from those with whom a strong personal relationship is dominant, and where collateral is found in trust rather than a purely economic instrument (FIGURE 5). It may be that, because government is often as driven by lowering its own costs in terms of policy implication and enforcement (transaction costs of a policy), that policy is limited in moving lending practices to the positive side of the borrowing spectrum.

This leads to the second lesson learned from this exercise.

FIGURE 5: Comparing Consumer Credit Sources

*“Natural Community” refers to informal loans from friends, family, or community groups (either ethnic or religious, or both) that borrowers have ties to. Examples of the latter include, for instance, the Jewish Assistance Fund (http://www.jewishassistancefund.org/) or benevolence funds offered by churches.

**“Loan Shark” refers to illegal lenders that operate outside any regulatory framework, often with ties to organized crime

People Matter More Than Producers, but Government Focuses on Producers

What is most fascinating about this exercise is how little information there is about how actual consumers react to the significant changes in the payday lending market. Almost all of the government’s data is drawn from producers, and government instituted virtually zero policies dedicated to research on the impact of the market changes on actual consumer behaviour. Did the increased disclosure rules change the way that actual consumers borrowed? Do we have a sense of whether demand went down or simply shifted? Will the decline of payday loan stores lead people to take more expensive credit options? Are consumers keeping more of their money in their pockets? The short answer is that we have no idea. Virtually all of the data we have takes the businesses offering products as their measurement stick; measuring actual behaviour by real citizens was not part of the policy, and little at all was invested (at least in Ontario, on which more below) in providing public data on the effects of the change on consumers. In the future, governments should invest more heavily in measuring actual consumer behaviour, rather than focusing primarily on the producers who are trying to serve those consumers.

Which leads to a final lesson.

Policy Should Include Provisions for Measuring Its Own Effectiveness

The payday lending changes were premised on the goal of providing better, more economically enabling, small-dollar credit markets for consumers. And, while we noted above that the measurements chosen by Alberta to measure whether that goal was met were insufficient, the Alberta government should be given credit for making the public release of industry data part of its changes. This move enables researchers and others to have a clear picture of the evidence, which allows citizens, businesses, and others to make considered judgments about the efficacy of the policy at achieving its goals. Ontario, on the other hand, has no such requirements, and as such it falls to think tanks and others to request data—some of which is simply unavailable, or available in formats that prevent comparison with previous regulatory effects, and those in other provinces. Including the public release of such data as a matter of course would be a boon for effective government, sound business policy, and consumer protection.

What's Next?

Given that changes to markets and consumer behaviour occur over longer periods of time, Cardus will continue to monitor data as it comes out so that policy-makers and citizens can have a clear picture of the changing nature of the small-dollar credit market. In the next year, keep your eyes open for new analysis of data being released by Alberta, and for our continued monitoring of Ontario’s payday lending market.