Acknowledgements

Dr. Cameron Airhart (Dean [retired] Houghton College Buffalo Campus)

Rev. Dr. Tom Yorty (Westminster Presbyterian Church)

Ben Bissell (WEDI) Bryana DiFonzo (WEDI)

Yanush Sanmugaraja (WEDI)

Andrew Gaerte (Buffalo Community Foundation)

Charles Massey (retired—Houghton College)

Rev. Richard Stenhouse and Ken Peterson (Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church)

Cindi McEachon (Peace Prints)

Introduction

How can a local congregation directly support its neighbourhood’s economic growth and other forms of resource development for the common good? Are economic forms of development possible at those kinds of neighbourhood scales through faith-based groups like congregations?

In what follows, we will examine certain aspects of how Westminster Presbyterian Church in Buffalo, New York, undertook to establish the Westminster Economic Development Initiative, which is geared toward improving quality of life for local communities. Our examination is partial but seeks insight about successes and difficulties that the initiating organization and the new business-development organization may face. Our hope is that others who read this story will be able to see more clearly how they might contextualize these insights to support their own community-development plans. Although this case involves a local congregation, other types of organizations and enterprises may find ways to take advantage of these insights to support local thriving. The story of Harmac Medical Products in east Buffalo suggests one way that long-term development work at a neighbourhood level has been carried out in Buffalo.

Reports such as this are linear in nature, while what we describe is not. The dynamics of neighbourhood improvement are complex, resisting linear descriptions or solutions. We have attempted to avoid simplifying these dynamics and processes. Our success in doing so can only be limited. Attention to the dynamics and implications may be of use to other people seeking to foster projects that support their own common-good needs.

It is critical that these caveats be clearly and openly seen and understood. The reader may, in so doing, gain insight without oversimplifying a very complex process.

Founded in 1854, Westminster Presbyterian Church began as a small congregation on Buffalo’s north side. Four years later, a building project commenced and was completed in 1859.

In the first one hundred years of operation, the church underwent a few periods of growth and was involved in many different community groups. In the 1960s, it began a period of self-reflection on its place in the world, building connections with church leaders around the world.

From the 1970s until recently, the church increased its community engagement through large children’s-ministry programs, micro-loans for business start-ups, and partnerships with Habitat for Humanity. It also offered its church facilities for use by many different non-profits and community groups in Buffalo. In 2006, Westminster founded the Westminster Economic Development Initiative (WEDI), which took over the community and economic-development programs that the church had been running.

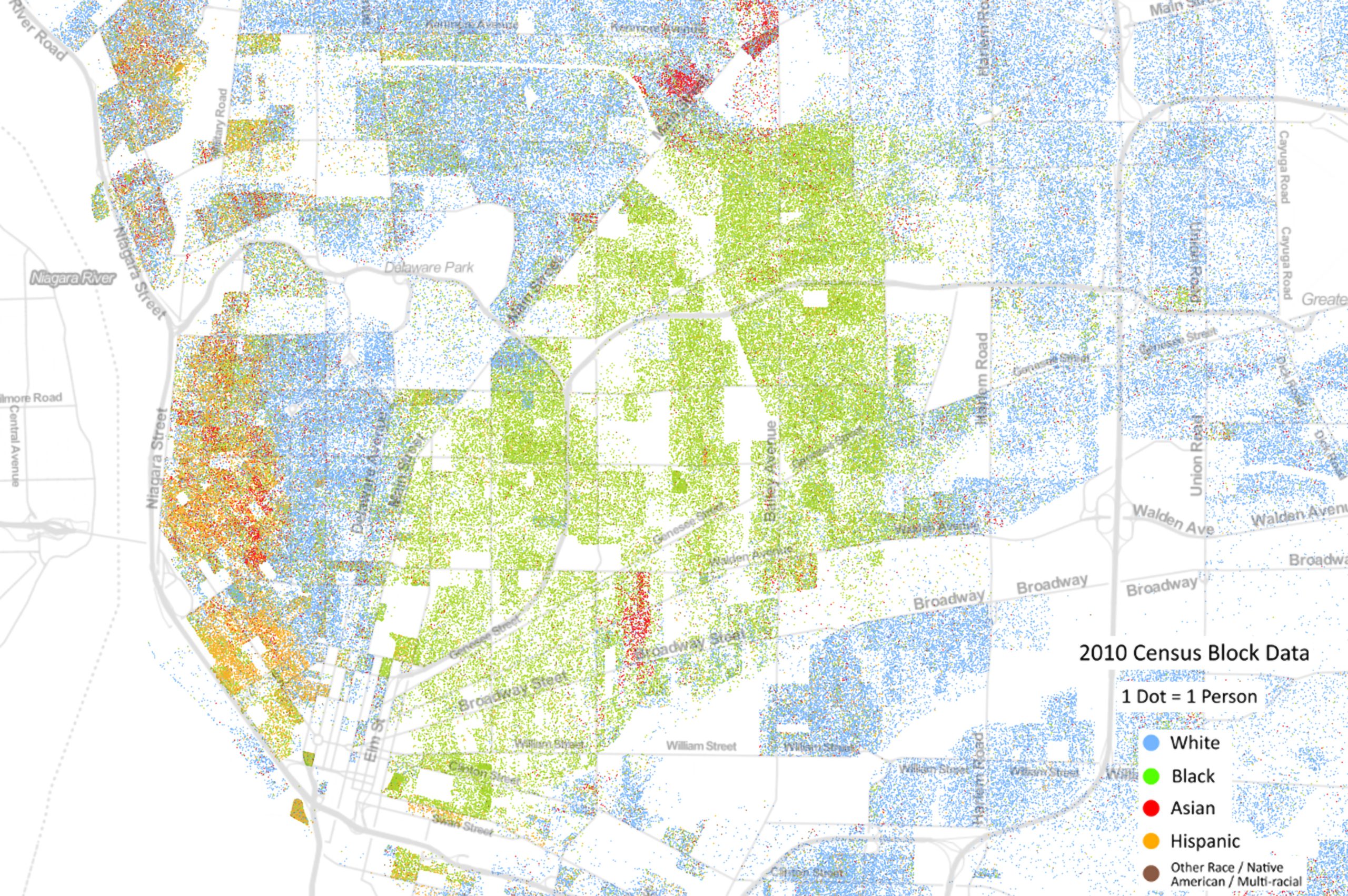

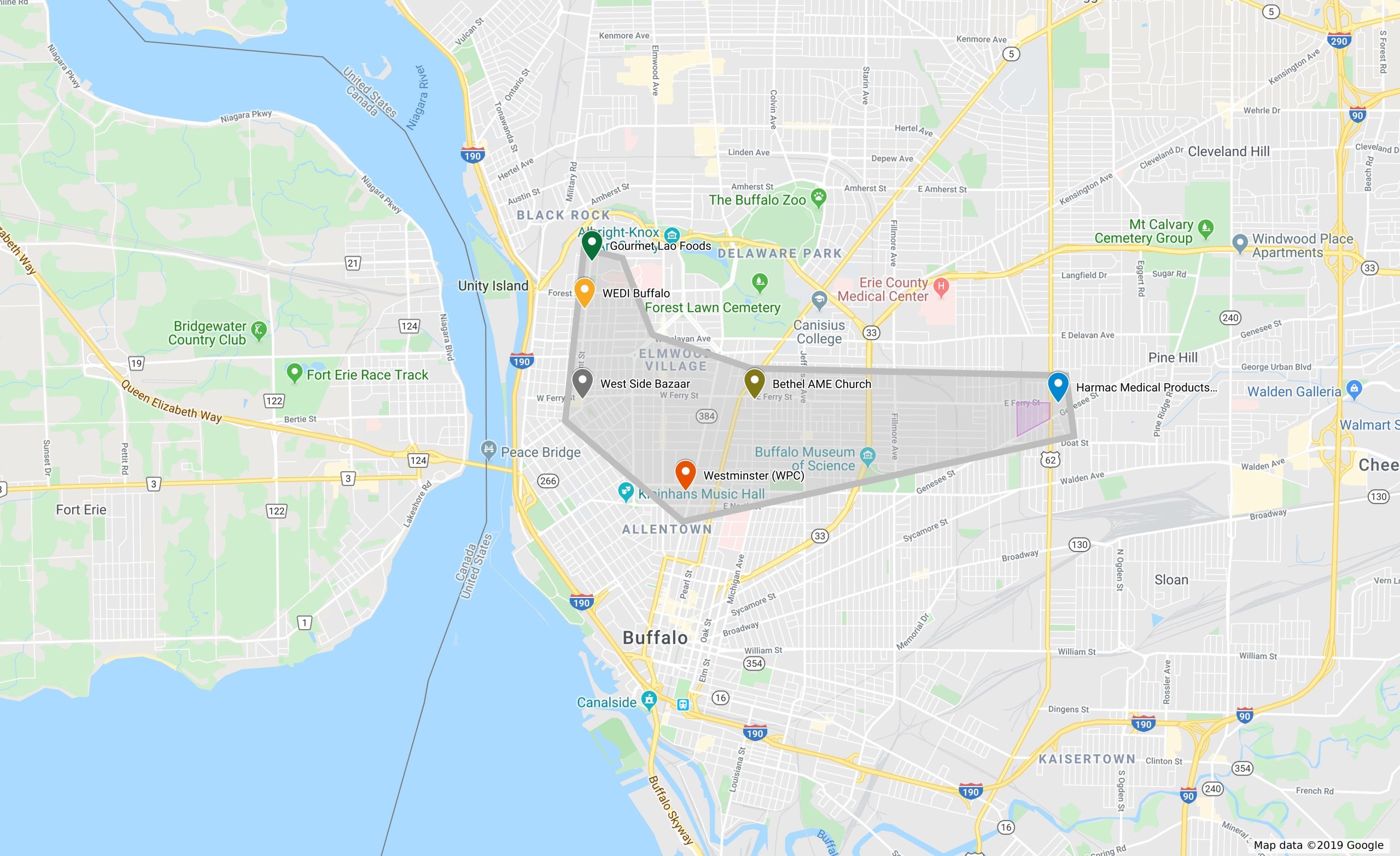

Westminster Presbyterian is located in a predominantly white, well-off neighbourhood, and the demographics of the congregation reflect that context. The church is located near the border of a noticeable socioeconomic divide in Buffalo between the east and west sides of Main Street. Residents on the west side tend to be white and wealthy, or at least middle class, while those on the east side are ethnically more diverse and lower in income. WEDI and the West Side Bazaar, which will be described below, are located on the west side of the city, where Latino and new immigrant communities are more concentrated (figure 1).

Figure 1. Plot of racial composition of Buffalo, New York. Source: http://demographics.virginia.edu/DotMap/index.html Red star is Westminster Presbyterian Church and the black star is the WEDI office location.

When faith-based organizations create community-outreach programs for “the less fortunate,” there can be a tendency to unintentionally reflect paternalistic attitudes that limit the longterm effectiveness of the program and can even harm the community and individuals that the organization initially sought to help (Corbett 2014; Lupton 2012). With a location near the racial and economic divide in Buffalo, Westminster’s decision to enter into longer-term economic and community-development programs represented a significant risk, putting to the test its stated mission:

“Westminster welcomes all people to participate in our worship of God, join our program life, support our mission and call upon our pastoral services. Our church is open and voluntary; inclusive of people of all ages and backgrounds making us a truly diverse and interesting family.”

The east-west division has deep historical roots. Reinforcement of that division has taken the form of explicitly racist zoning laws in the early 1900s, legal redlining (refusing loans based on neighbourhood demographics) in the middle of the century, and racial segregation in public housing and waiting lists for housing in the 1980s. These divisions persist today in many forms, including realestate agents providing “suitable” options to their clients based on race (Weaver 2019).

A core theme in this case study concerns how an existing institution or local organization that has resources, stability, and intention translates these into direct neighbourhood benefit. The value of local congregations to their communities has been known for some time (Cnaan, Forrest, Carlsmith, and Karsh 2013; Cnaan, Sinha, and McGrew 2004; Cnaan and Handy 2000), but that positive impact is often difficult to see or is assumed to quietly percolate into the community. Westminster sought to go beyond this built-in effect and to formalize another organizational entity that could directly foster well-being in the local neighbourhood, taking on challenges such as education, poverty reduction, employment growth, and economic development.

New Organization: Westminster Economic Development Initiative

Westminster Economic Development Initiative (WEDI) was founded in 2006 by Westminster Presbyterian Church. In line with its history, the church began this initiative with the goal of generating economic growth for the community near the church. The wide socioeconomic gap between members of the church and community members in the lower west side represented a key challenge.

Initially, WEDI was entirely volunteer-run, was completely connected to the church, and was doing work in several different sectors. It took over an after-school program called ENERGY (Education, Nurture, Encouragement, Readiness, Growth for Youth) that Westminster had previously run. WEDI also continued the micro-loan and business-training program that the church had started. Third, WEDI worked with Habitat for Humanity in revitalizing a group of homes on Ferguson Avenue.

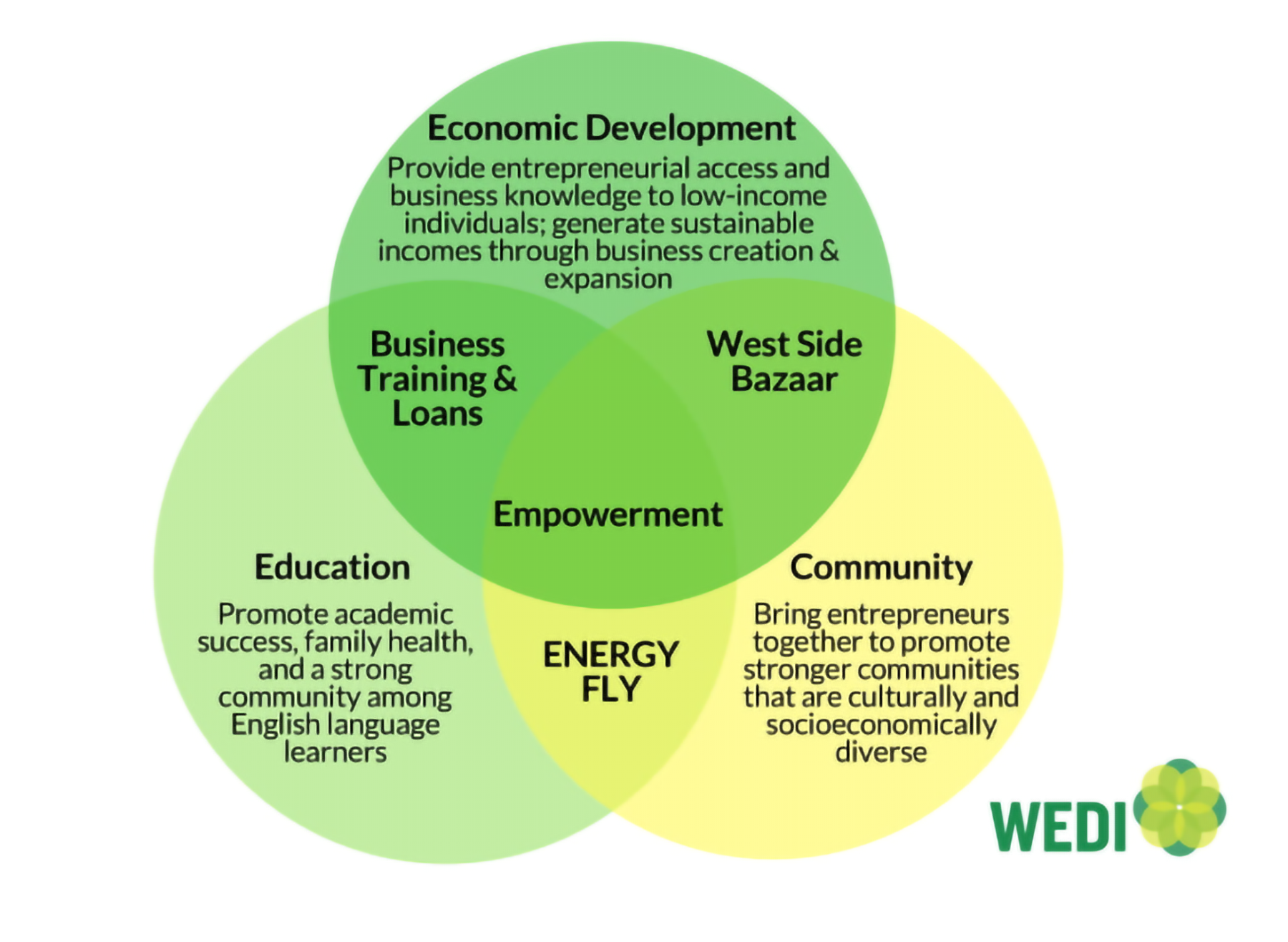

In 2007, the church decided to organize WEDI as an independent 501(c)3 charity. Around this time, WEDI also began exploring economic-development strategies, leading to the establishment of a small-vendor indoor marketplace called the West Side Bazaar. In 2013, WEDI underwent a series of changes. It hired a new executive director, Ben Bissell, and decided to discontinue its work in housing. By narrowing its scope to economic development, education, and community development, WEDI was able in 2015 to expand its reach to all neighbourhoods in Buffalo (figure 3).

Figure 3. Overview of WEDI program areas. Source: https://www.wedibuffalo.org/about

The educational projects that WEDI sponsors are ENERGY, FLY, LAUNCH, and Girls Club. Each of these projects focuses on supporting English Language Learning (ELL) students, children, and youth at different stages. ENERGY, the after-school program that Westminster Presbyterian Church founded, is for younger students (grades 1–6) and focuses on social and academic skills. The FLY program is specifically for refugee students in middle school, and runs year-round. It offers homework help and opportunities for extra learning, as well as a place for students to develop community ties and practice speaking English in a less daunting setting than their public school. LAUNCH is similar, but directed toward high-school-age ELL students and students with interrupted formal education. LAUNCH provides school support but also offers help in college and career preparedness and financial literacy training. Girls Club is a bit different, as it is not focused on formal education. Rather, each cohort of high-school girls (twenty per group) meets for four Saturday sessions covering the topics of “puberty and body changes, personal hygiene, self esteem, and bullying prevention” (wedibuffalo.org/girls_club).

West Side Bazaar

Westminster’s initial focus for WEDI’s economic-development program was a small micro-loan program and business incubator in the west end. In the founding years, a few leaders and financial backers at Westminster hoped to expand their reach, and connected with a stakeholders’ group in the area that coordinated projects. After getting the green light from the stakeholders’ group, WEDI began outreach in the west side, spreading the word about the incubator and looking for potential smallbusiness owners to partner with. Unfortunately, the initial door-knocking in the community did not lead to sufficient interest. Not discouraged, WEDI continued searching for partners and eventually found interest within Buffalo’s immigrant community. Due to this unexpected clustered response from new Americans, the idea of a general small-business incubator evolved into an “international marketplace,” named West Side Bazaar.

The Bazaar is scaled to suit immigrant communities accustomed to street-vendor booths and stalls. These small, new-business owners can access business-development help, rent a small space below market value to start a shop or restaurant, and do so in a setting where other small entrepreneurs and customers create a right-sized market. Small-business owners outside of the Bazaar and individuals considering starting a business can also access assistance and training from WEDI.

Use of the Bazaar has resulted primarily in food and retail vendors originating in the local immigrant community. The preexisting indoor retail space was divided into rentable spaces suitable for around fifteen micro-enterprises. Collaboration among vendors enables them to offer a large catering menu.

Initially, the assumption was that the Bazaar would serve primarily as a launching space for standalone enterprises, the first step in a larger business plan, but most business owners involved in the project have not shown interest in moving out of the incubator into their own storefront.

Other unexpected outcomes include Kitchen @ The Market, a shared cooking space that can be rented as needed. This represents a much lower entry point for a new chef or food business while meeting the requirements for a commercial kitchen. Located in Buffalo’s Broadway Market (an organization independent of WEDI, but similar to the Bazaar), it is accessible and very close to spaces that can be rented to sell the food made in the Kitchen. WEDI did not start this initiative but was selected to run it because of the structural similarities it has with West Side Bazaar.

Development of the social aspects of community are a key principle in all of WEDI’s work. WEDI’s website lists Kitchen @ The Market and West Side Bazaar under “community development” and “economic development” categories. This overlap between educational and community support characterizes the crossover present in other aspects of WEDI’s work such as the ENERGY, FLY, and LAUNCH programs.

This brief review of the West Side Bazaar story suggests several points of consideration for other community developers.

- Be willing to adjust, but keep sight of your main goal. WEDI initially had trouble finding potential business owners, but did not change the design of its economic-development plan, persisting until it found the right community.

- Adjustments will be ongoing. Over time it became apparent that many of the business owners preferred to stay in the Bazaar rather than move on to become stand-alone enterprises. Over the next several years, WEDI will need to decide whether it wishes to adjust the initial goals of the Bazaar, limiting how many people will be helped, or adjust the means by which those goals are reached. A good fit between size, customers, and services challenged the “launch-pad” assumptions of earlier thinking. What is the role of community development and maintenance alongside economic development? If business owners move out of the Bazaar, will their connectedness in their community suffer, offsetting the benefits of their economic growth? If this is the case, are there other models that could work better?

- Structural issues are always important. Any organization hoping to replicate the West Side Bazaar approach should keep several structural dynamics in mind:

- Funding: for the space that the incubator will be in and for providing micro loans to business owners.

- Connections: to city leaders and community members.

- A knowledgeable team: people who are able to commit lots of time, who work well together, and who have the right skill sets.

- Skills: in intercultural communication, business and financial management, understanding city regulation, and knowledge of business/food standards.

- Proper attitude: paternalism cannot accomplish what might be done with respect and a willingness to learn before jumping in with solutions.

- Guidelines: What requirements do new tenants and business partners need to meet? What will you promise to these tenants and partners? How will you know when a vendor or project isn’t working and requires intervention of some kind?

Replication of a congregationally initiated effort like the West Side Bazaar will encounter failures and difficulties. Economic development at neighbourhood scales is a deep learning process. One such learning point from West Side Bazaar relates to how business owners were initially sought.

Even though WEDI had connections to the west side, and particularly to immigrant communities, it did not consult these communities when designing the original outline for Westminster Bazaar. Why not? Perhaps business owners’ disinclination to leave the Bazaar could have been foreseen and addressed earlier if the plans had been designed after serious consultation with the community. New ventures like these may be best served by developing organizational strategies that are designed to be flexible and adaptable enough to explore and learn about new opportunities. If the planners had consulted the target community in advance, they may have developed a more effective strategy. This approach would have taken more time and faced challenges, but it would have better matched actual need.

The Founding of WEDI’s Most Famous Project

Jerry Kelly

June 13, 2018

In 2007 John Perry and I, the two founders of WEDI, decided that we wanted to begin an economic-development program to complement our Ferguson Avenue Habitat home-ownership program on Buffalo’s west side.

But what to do, and how to do it? My son Jason grew up at the Butler Mitchell Boys and Girls Club on Massachusetts Avenue. Because of this, I got to know and admire club director Nick Bonifacio, who was eventually elected Buffalo’s Niagara District councilmember and then majority leader.

John and I went to Nick and asked him what the economic-development needs of the west side were. He said that Niagara District Councilmember David Rivera was formulating a stakeholders group to assess the needs of the west side and coordinate projects.

So as newcomers, we went to this group and had many discussions about how to do economic development on the west side. At first, I think we were viewed as church dilettantes who probably didn’t want to get our hands dirty in the trenches. But after a while they learned about our Habitat home-ownership program. And most importantly, they noticed that we just would not go away. So after meeting after meeting, it was finally decided that the west side needed some type of incubator to assist new businesses with low rent and low-cost financing.

But who should do it? We were newbies. All the other agencies, however, had defined programs and were already very busy. So at one of our meetings, someone finally said, “Just let Westminster do it.”

Hence, we charged out with our already-functioning microloan program and found a storefront on Grant Street to lease. We then went out with advertising and a door-to-door solicitation to recruit entrepreneurs from the underserved population on the west side.

At first we had great difficulty in stimulating interest. That was until we started contacting the west side’s newer immigrants from regions such as Asia, Africa, and South America. Many were to show great interest and were eager to participate.

And so WEDI’s West Side Bazaar was born as an international marketplace of shops and restaurants, owned and managed by Buffalo’s growing immigrant population.

During the history of the Bazaar, only one of its vendors has moved out of the incubator and begun operating on its own: Gourmet Lao Foods. With help from WEDI, it moved to its own location at 643 Grant Street on November 31, 2018. It is a full-service restaurant open six days a week and seats forty to fifty patrons during good weather. Local media noted the opening as an exciting business- and community development story in Buffalo. This unique instance emphasizes how important it is to adjust initial expectations or plans to actual conditions and realities as they are encountered.

Could the story of Gourmet Lao Foods be replicable for other Bazaar businesses? There may be a variety of reasons for the lack of replication so far. It may be the case that the Bazaar needs a much larger number of micro-businesses before it creates favourable conditions for some to expand off site. Cultural values of start-up enterprises may place a premium on being near other likesized enterprises or the presence of a support community from within the Bazaar. There may be uncertainty about the significant costs and growth required to make a move to independent space possible. Small Bazaar businesses may also be meeting the needs of the owners and families who operate them and are sufficient at that scale. Increasing size and business complexity may be a more significant barrier than originally anticipated.

As suggested in the section about West Side Bazaar, if staying in a small booth is a preference, rather than a reflection of a lack of options or abilities, expectations about replication of Gourmet Lao Foods may have to be adjusted. The Bazaar has a waiting list to open booths. Working from the assumption that small-business owners in the Bazaar are choosing to stay because they value the non-financial benefits it offers more than the financial growth their own individual restaurant would offer, pressuring business owners to move out would be contrary to the underlying goals of the Bazaar (economic and community development). Instead, increasing the number of booths may yield a critical mass of smaller enterprises out of which stand-alone businesses could emerge.

The nature of the relationship between start-up and independence is unclear. Do such small enterprises naturally grow into larger businesses, or are independent commercial efforts simply a different kind of entity right from the start? While the Bazaar supporters and organizers may be able to answer some of these questions, the direct results of their efforts provide important insight for other local economic development initiatives regarding assumptions about growth and progress.

Bridging Institutions and People

Houghton College (Buffalo Campus)

Located just a twenty-five-minute walk from West Side Bazaar is the Buffalo campus of Houghton College—a liberal-arts college whose main campus is in Houghton, New York. The Buffalo satellite enables local students who qualify financially to graduate with an associate’s degree, debt free, in two years. Connections to WEDI and Westminster Church are bridged by Dr. Cameron Airhart, Dean of Houghton before his retirement in 2018 and an early participant in WEDI and the Bazaar. An additional supporting organization was Bak USA, one of the only laptop-manufacturing companies in the United States. The aspirations of the Bak founders and owners was to create a local, sustainable tech-assembly company. Many of Bak’s employees were new immigrants, and the company supported Houghton College by donating laptops for the students, among other communitydevelopment efforts. Unfortunately, the company struggled to remain profitable, eventually succumbing to additional tariffs on manufacturing and closing in November 2018.

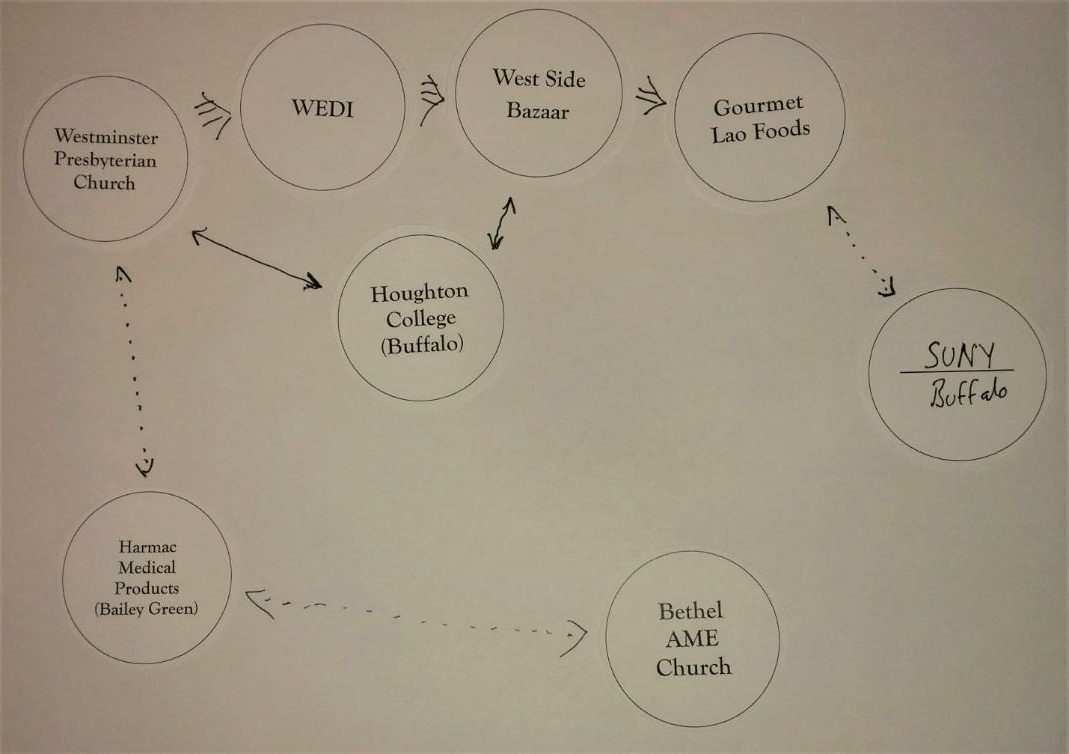

WEDI and Houghton College are just two examples of the revitalizing work being done in the waterfront area of Buffalo. They are designed to be self-sustaining and empowering projects that are well adapted to serve the unique needs of local community members. Houghton College in Buffalo, Westminster Presbyterian Church, and the Bazaar, along with the crossover role of people like Cameron Airhart, exemplify the complex and related nature of many projects that may seem to be independent at first glance. Their growth, however unique in individual cases, is often related to interdependent and complementary projects, where key people, opportunities, and capabilities can be leveraged for neighbourhood development.

Harmac Medical Products and Bailey Green

In addition to the efforts described above that are active in west Buffalo, there are complementary but distinct efforts to innovate in east Buffalo. One notable commercial-investment project is the revitalization of Bailey Green (see figure 2). The neighbourhood is home to Harmac Medical Products, a medical-device manufacturer. Harmac’s vision statement includes “Changing the lives of patients, employees and the communities in which we work” (https://www.thepartnership.org/wp-content/ uploads/2018/06/Harmac-Revised-Presentation.pdf).

Harmac Buffalo employs about four hundred people, many of them from Bailey Green and surrounding neighbourhoods. In 2008, in response to its vision statement and the marginal living conditions of the Bailey Green neighbourhoods, Harmac decided to undertake the Bailey Green Initiative. Housing and community development work has included a partnership with Habitat for Humanity, the creation of an urban farm in an old factory, and a community mentorship program. Like WEDI and Houghton College, the Bailey Green Initiative aims to create a sustainable, positive impact on the community where it is located.

Harmac is a long-established, much larger business than Gourmet Lao Foods or the Bazaar businesses. It operates independently but reflects a common desire to improve the quality of life in its neighbouring community by contributing to its economic growth. Common-good objectives arising from a for-profit firm suggest that neighbourhood renewal does not have a singular source, method, or scale. Harmac may have greater resources and therefore can explore housing and blocklevel improvements, while the Bazaar and WEDI are focused on many smaller efforts. Projects that arise from within the local context appear to be more effective than solutions that are designed outside of the local setting and prior to implementation.

Bethel AME Church

The long-standing racial divide between the geographies of east and west in Buffalo along Main Street continues to shape life for Buffalo residents in significant ways.

Harmac Medical Products’ investment in Bailey Green is an east-side development initiative that is complemented by long-standing work done by the Bethel AME Church congregation. Neither Harmac nor Bethel AME Church is formally tied to Westminster Presbyterian Church, but both reflect complementary instincts of care and development for their respective local residents.

It is challenging to consider how these other aspects of neighbourhood development should be related to the church’s efforts. The limits of this report mean that a selective process was necessary, but it is important to acknowledge, in some measure, the wide-ranging work that is constantly going on in the communities of Buffalo. Featuring specific projects can inspire, instruct, and provide warning as others endeavour to make similar investments. A lingering question involves the possible role of formal linkages between independent circles of effort. Weaving relationships, personal and organizational, across neighbourhood landscapes has never been easy, but the potential for increased social capacity suggests that those efforts are well worth undertaking.

Does the long-term vision of Westminster represent an impending and stronger partnership with Harmac or Bethel AMC Church and their respective development aspirations? Or does local development mean attending to what you can manage and leaving others to undertake their own projects as time, vision, resources, and talent allow?

Dynamics and Insights

At the risk of narrowing reflections prematurely, the following insights have been distilled from the many interviews, site visits, and conversations conducted over the years of preparing this case study.

- Westminster Presbyterian Church aspired to find ways to use the community resources that were part of its congregation, to improve life for people in its general neighbourhood. This desire, however, did not make the process of actually doing something easy, clear, or fast. Many years of work, including the long work of keeping its own community active and its property functional, were required to see a concrete project emerge.

- WEDI began with a range of ideas in mind, driven largely by the community’s needs for housing, education, and employment. Over time, through the vision and conflictmanagement process of the leadership, board, and volunteer groups, the consensus arose that housing was too much to address along with the other demands. WEDI needed to pivot, to shift, as it encountered many changing, and sometimes unexpected, dynamics. The art of changing course, of knowing when to stubbornly persist and when to consider a steep climb as a sign of terrain for which the organization is not suited, means that the path can’t be known ahead of time and will never be free of conflict and difficulty.

- West Side Bazaar was developed according to a logic that this marketplace was an incubating space that could help entrepreneurs enter the market at a level that made sense for both their means and their cultural sensibilities. However, the assumption that some number of these start-ups would lead to independent, stand-alone businesses needed to be adjusted over time. Many of the small start-ups seemed to be right-sized in the Bazaar setting. Unchecked upward mobility and business growth didn’t make sense for many of these small-business owners, who were meeting their needs in the Bazaar setting and may well have depended on that setting to stay viable.

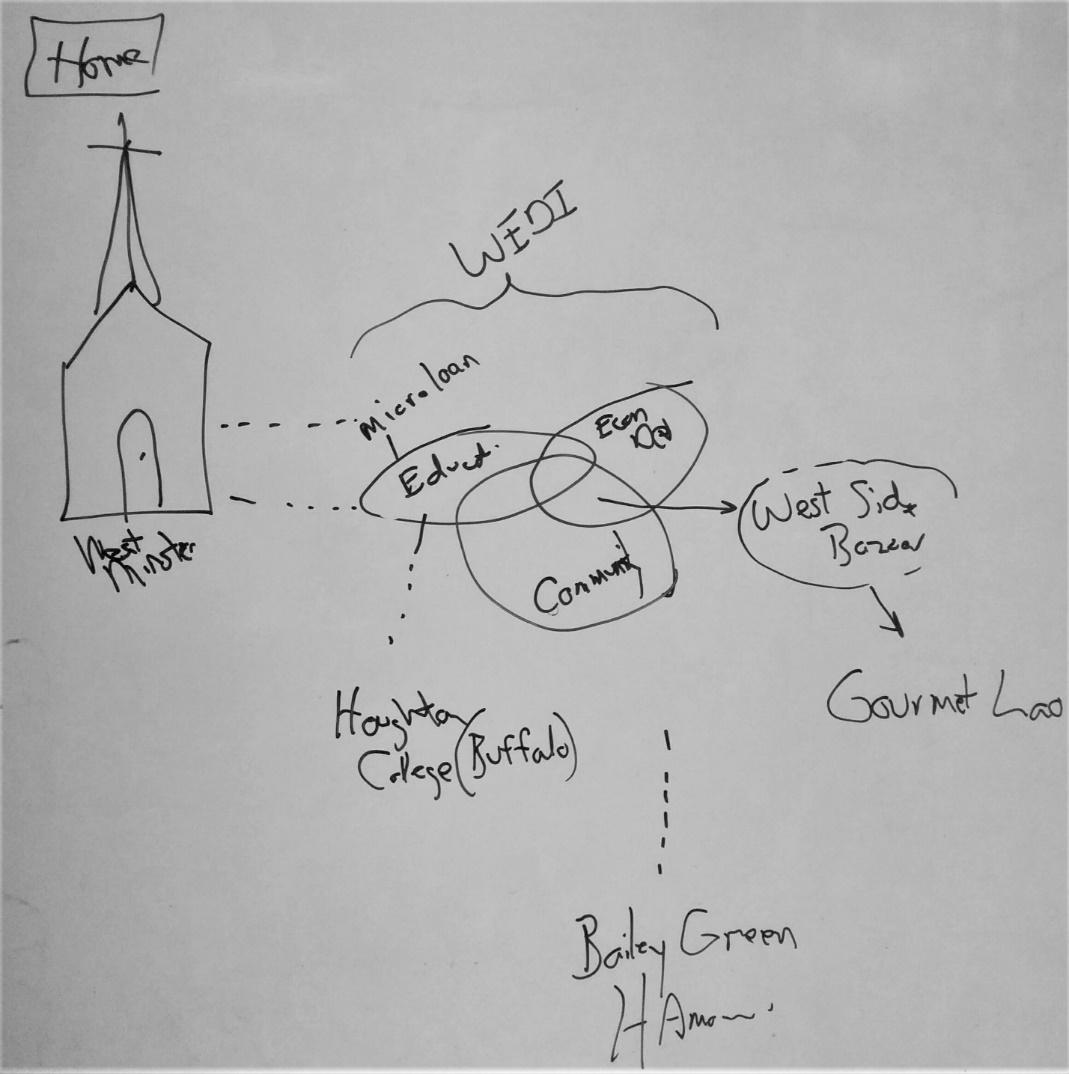

- The diagrams shown below reflect that there are many ways to understand, tell, and therefore replicate the story we have been tracing—the story of Westminster Presbyterian Church taking action in fostering well-being in its neighbourhood.

- None of the elements of this case study are static. The people and the organizational structures continue to change as they grow, decline, and adapt. Some have long, persistent histories. Others, like WEDI, exist over time with changing focus, people, and resulting investment. This implies that leadership in these settings requires continuous negotiation at individual and institutional levels.

Exercises for Alternative Ways of Understanding

If the core organizational entities noted in this report were arranged on a sheet of paper, what would the nature of their ties be? Are there key organizations missing? Would different people involved in these groups, or aware of them, arrange the pieces differently? How would they characterize the nature of those relationships? What if a time-dependent relationship were the organizing principle?

Sources Noted in Text

Cnaan, R.A., T. Forrest, J. Carlsmith, and K. Karsh. 2013. “If You Do Not Count It, It Does Not Count: A Pilot Study of Valuing Urban Congregations.” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 10, no. 1:3–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2012.758046.

Cnaan, R.A., and F. Handy. 2000. “Comparing Neighbors: Social Service Provision by Religious Congregations in Ontario and the United States.” American Review of Canadian Studies 30, no. 4:521–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/02722010009481066.

Cnaan, R.A., J.W. Sinha, and C.C. McGrew. 2004. “Congregations as Social Service Providers.” Administration in Social Work 28, nos. 3–4:47–68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J147v28n03_03.

Corbett, S. 2014. When Helping Hurts. Chicago: Moody Press.

Lupton, R.D. 2012. Toxic Charity: How Churches and Charities Hurt Those They Help. San Francisco: HarperOne.

Weaver, R. 2019. “Erasing Red Lines: Part 1—Geographies of Discrimination.” Buffalo Co-Lab, August 28. https://ppgbuffalo.org/buffalo-commons/library/resource:erasing-red-lines/.