Acknowledgements

Mayor Cam Guthrie, Rev. Dr. David Ralph, Rev. Graham Singh, Ms. Jaya James, Rev. Kevin Coghill

Purpose

Religion and religious groups have been integral to villages, towns, and cities for millennia. This is also true for communities of all sizes today. The presence of congregations in the city of Guelph is evident to anyone who visits, particularly in the downtown core, where iconic stone churches punctuate the urban skyline. What isn’t always as easy to see are the more integrated and less obvious effects of religious congregations on the community.

In this brief case study, we examine a particular set of dynamics that involve a range of congregational actors as they have developed strategies to make Guelph a better place to live for everyone. We make no attempt to be comprehensive or to offer the definitive version of this story—it is far too complex and dynamic for that to be possible. We will, however, seek to provide insight on a core set of questions.

The guiding questions for this study are as follows:

1. What led to the establishment of Hope House in a former United Church building?

2. Who were the primary actors, and what did they hope to accomplish?

3. What are the core insights that may guide groups in other cities to make a similar contribution to their communities?

4. How does Hope House compare to other church and social-purpose efforts in Guelph?

5. How do faith-based or faith-informed social-service organizations and places of worship relate to the formal structures of a municipality, such as its city-planning processes?

Context

Located in Guelph, Ontario, are seven nineteenth-century stone churches representing a long religious legacy. Changing land use and demographic trends mean that some of these historic churches are less well attended than was the case in the past. The age and design of these buildings means maintenance is often difficult and costly (Hill 2017). Shrinking numbers can lead to worries about the future of the church—both body and building. Guelph’s official plan states that “the city’s future depends on carefully balancing yesterday’s legacy, today’s needs, and tomorrow’s vision” (“Official Plan” 2018, 6). City managers and planners may encounter questions from citizens about the city’s role in maintaining these heritage sites, particularly in downtown areas as people move to the suburbs. The stone churches clearly reflect that faith and organized religion were vital to “yesterday’s legacy,” but how do they reflect Guelph’s current reality?

Studies concerning the social and economic impact of faith-based organizations (FBOs) on their cities, neighbourhoods, and communities suggest that they are continuing to have important value even where the congregational numbers are in decline. A recent study found that of the ten Toronto congregations considered, there was an average annual common-good contribution to the community of $4.5 million per congregation, in such areas as community development, education, and social care (Wood Daly 2016). Not only that, but FBOs are often key facilitators of solidarity and trust—two important elements of human existence that have been slowly declining in many Western societies (Friesen 2017a).

As we see FBOs settling themselves outside of the city centre and scattered through the everincreasing urban sprawl (Friesen 2017c), these newer suburban congregations may end up playing an important role in the life cycle of churches in the city core. Suburban congregations may wonder how they can contribute to efforts addressing the types of social problems that often cluster in the inner city, such as poverty. Naturally, not every mosque, church, gurdwara, or temple will have equal impact, but two churches in Guelph have demonstrated how historic church buildings can be maintained and used even more fully to serve the wider community.

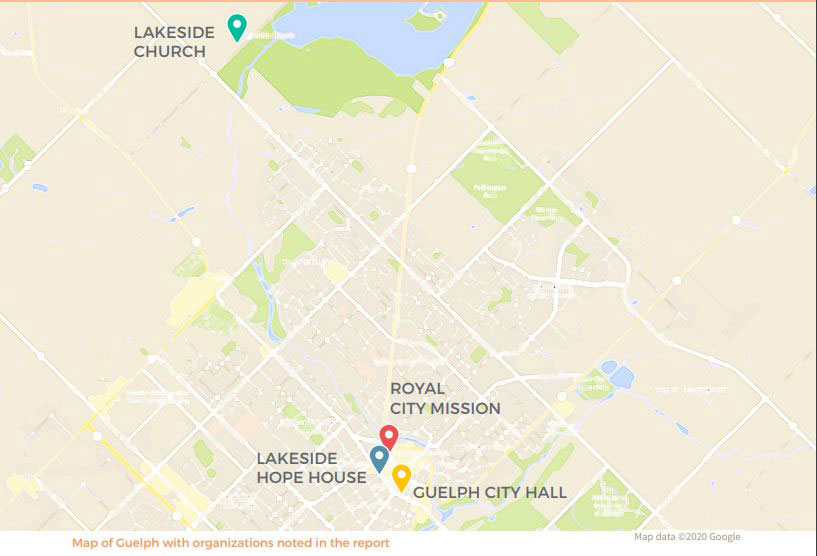

Examination of Hope House and the role that Lakeside Church has played sheds light on the current impact of FBOs. For faith groups seeking to carry out their mission within a changing culture and geography, this report offers an outline of the successes and challenges of some key players in Guelph that have invested significantly in their surrounding communities, as well as a summary of the transferable elements found in them.

Guelph Downtown Development

In March of 2018, the city of Guelph released a new consolidated plan for the city, outlining the goals it hopes to achieve by 2031. It includes goals for the density of the city and for the jobs available. According to census data, Guelph had a population of 131,974 in 2016 (Government of Canada 2017). The city’s most recent plan expects to see a population of 175,000 in 2031, a 33 percent increase in fifteen years. Based on this projection, the plan outlines eight goals involved in development for such growth. These include “planning a complete and healthy community,” “protecting what is valuable,” and “community infrastructure.” These structural and conceptual goals are noble, but the means to achieve them are less clear and may overlook important contributors to Guelph’s social capacity.

Although churches and other faith-based organizations are significant contributors to the common good of the city, the 403-page document does not include any direct apprehension of that contribution. Religious organizations or facilities are mentioned once in a definition of community facilities and four times in a discussion of zoning concerns. There are scattered references to the stone church buildings of Guelph but little else in the way of faith-based buildings, locations, or social services. The official plan thus reflects a historical and architectural understanding of FBOs rather than a more substantial understanding of the vital contemporary and communitydevelopment role that many of them play. This is not unique to the city of Guelph; for various reasons, city planners are often not aware of FBOs’ contributions to the common good of the city and do not develop their plans with these contributions in mind.

Section 7.1 of the 2018 plan states that “because a significant portion of community facility provision is not within the jurisdiction of the City’s administration, coordination between the City and public boards and agencies is essential.” Given that the plan does not recognize the unique impact of FBOs, there may be room for the city to improve its understanding of the social and economic benefits that religious organizations provide. In turn, FBOs may need to invest more in understanding the structural and functional aspects of the city, since those dynamics are closely related to the common-good mission that many of them are seeking to carry out.

Understanding the relationship between FBOs and city administration is best illuminated by examining the dynamics of a specific case in the city of Guelph.

Lakeside Church and Norfolk Street United

Lakeside Church was established in 1989 by forty families just outside of the boundaries of Guelph, and from the outset it had a clear focus on serving the needs of the community. Seven years after its inception, this non-denominational church had grown, and the facility was expanded. As the church continued to flourish, more expansions were undertaken in 2001 and 2007 before consideration was given in 2011 to purchasing a second building.

During this same period, Norfolk Street United Church in downtown Guelph (one of the seven stone churches) was experiencing declining membership, leading to the difficult question of what to do with a building that was becoming less and less affordable. Through a series of events and meetings, Norfolk eventually sold its building to Lakeside Church in 2012 (Armstrong 2018).

The seven stone churches are all listed on Guelph’s Municipal Register of Cultural Heritage Properties, and the congregation did not need to worry that the building would be demolished or become decrepit if it was sold. Via the Guelph Cultural Heritage Action Plan, the city has taken on the responsibility to ensure that heritage sites such as Norfolk United are maintained (MHBC Planning 2019). But while many congregations would prefer that their building be maintained specifically as a place of worship, after selling their property such considerations pass out of their control. What made the sale of this historic worship site easier for the Norfolk congregation, said Allan Knapp (church council chair), was that it had three years to transition to a different location and the building would be maintained as a church (“Guelph’s Lakeside Church Set to Pay $1 Million for Norfolk United” 2012). The sanctuary would continue to serve as a worship space, and the social services that it was providing to the surrounding community would also be retained and extended. Lakeside began holding regular worship services in the building shortly after the purchase and took over operation of the wide range of social and community services that Norfolk United had been providing, including distributing food hampers and backpacks for schoolchildren. Lakeside Church also continued to hold worship services, and opened a fully licensed child-care centre, at its suburban location.

Although this particular case involved a congregation-to-congregation interaction, city administration would benefit from noting that these kinds of arrangements are part of a larger network of social-service activities in a downtown area. Because the church is contributing these effects out of its own resources, the city can keep its own costs down while still supporting the common-good services that are needed.

Lakeside Hope House

For several years before purchasing the Norfolk building, Lakeside had worked with Norfolk to support a youth shelter in the downtown area. When Norfolk United was purchased, Lakeside decided to transform the shelter and incorporate Lakeside Hope House (commonly referred to simply as Hope House) as a legally independent, non-faith charity but with a structural provision requiring that three of the eight board members be elders or senior leaders of Lakeside Church. Over time, this provision has been reduced to one seat. In the early stages, funding came primarily from Lakeside Church, but Hope House has now expanded its services and funding streams, leading to greater financial independence. It now offers a wide range of services, from grocery and clothing services, to opportunities to participate in drop-in arts programs, to a “Circles” program that builds relationships between low- and middle-income families. Hope House also has support workers onsite to assist community members in navigating the social-services systems.

Hope House is organized around a five-dimensional model of well-being: (1) physical, (2) spiritual (meaning and purpose), (3) emotional, (4) relational, and (5) financial health of community members. The spiritual aspect of this model does not necessarily refer to Christianity but does reflect Hope House’s deep religious roots. Support and spiritual well-being are emphasized for all employees, even those without a personal faith, as an essential part of overall wellness. A balance of these five dimensions holds Hope House together and has been an integral part of its ability to provide support and care to the wider community. It emphasizes that poverty is about more than just money and that relationships are extremely valuable. Jaya James, executive director, summed it up by stating, “At Hope House, we say that the opposite of poverty is community.”

Communication between Hope House and the city of Guelph is intermittent. There are undoubtedly efficiencies and opportunities for coordination in areas such as homelessness, employment, and social support that would benefit from ongoing communication. The city’s plan for creating healthy communities is focused almost entirely on financial and physical considerations. Hope House is able to offer a more holistic approach in ways that lie outside the scope of most city planning. Acknowledging and supporting FBOs as vital contributors to the relational and spiritual elements of wellness could be a bridge connecting the different dimensions of community health and congregational life.

Leading Change

Like most FBOs, critical leadership during Lakeside Church’s season of intense growth shaped the nature of its long-term impact. David Ralph, senior pastor at Lakeside between 1999 and 2017, brought to the board the possibility of purchasing Norfolk United. His emphasis on the congregation’s traits of community outreach and service led to strong support for moving forward when the opportunity arose. Pastor Ralph stressed the importance of having the right mindset rather than being overly reliant on methods. He explained in an interview with Cardus that his “focus was to keep mission central—not worship style or approach.” He encouraged the church to maintain an understanding of what was driving them, what he calls the “why” or the purpose of their work as a church, rather than relying on habit alone.

Toward the end of his time leading Lakeside, Pastor Ralph began to observe more resistance to his emphasis on Hope House as an integral part of Lakeside’s church life: “There was a sense that Hope House was acceptable as something we did out there, downtown. What I had always talked about and worked toward was that as the church, it isn’t something extra we tack on.” The emergence of conflicting viewpoints between leaders and boards or congregations suggests that simple formulas or imitation will not be sufficient for those who wish to learn from or emulate the work of Lakeside Church and Hope House.

Given Lakeside’s noting and then acting to save the Norfolk United building as a place of worship and a site for community-oriented service, it is tempting to summarize the project as a success. The ongoing challenges, however, resist such simplifications. Congregations can change their focus; leadership may change, and with it careful balances of priorities can shift. The needs in a community receiving the services can also change through economic, demographic, or cultural shifts. If FBOs and the communities they serve are dynamic and complex, one of the deep insights for both city administrators and the network of agencies involved is that communication, collaboration, and negotiated adjustments are a constant. Developing, leading, and sustaining social-care organizations does not work on autopilot, nor do they ever fully arrive. A key question is whether the negotiated changes and navigational choices lead to ongoing vitality and service.

Leaders such as David Ralph argue that declining congregational engagement in work like Hope House reflects a negative change. Others caution that if too much of a church’s work with the poor is institutional, it will discourage individual friendship, mercy, and hospitality (Friesen 2017b). Jaya James would concur, noting that the work of serving others cannot be successful with an “us and them” mentality. The balance needed is dynamic, requiring effort by Lakeside Church and others who may use a similar approach. In both the FBOs and city administration, a tension exists between individual responsibility and action, and institutional delivery of services. Institutional approaches can create a service-delivery/client dynamic on the service side and a decrease in responsibility on the part of individual volunteers who may assume the organization will get things done without them.

Nearby Doesn't Mean Close: Royal City and Chalmers United

Guelph also offers a parallel story of congregational engagement, downtown service, and leadership direction. At 50 Quebec Street stands a grey granite church that was built in the second half of the nineteenth century (White 2017). Like Norfolk United, Chalmers United was declining in membership. Another downtown church, Royal City, was in a position to expand its hospitality and meal-preparation ministry, particularly its work in serving downtown Guelph people at risk. Royal City purchased the Chalmers United building in 2005 and since then has been using it as the congregation’s primary location for Sunday ministries and for a meal program called the Life Centre.

The Life Centre

The Life Centre is a formal part of Royal City Church. It is open for a meal every day except Sunday and provides up to six hundred meals weekly as well as music, art rooms, and games. Volunteers, staff, and guests are encouraged to get to know each other, and attempts are made to remove any distinctions and power dynamics, particularly between the congregational volunteers and those being served. Kevin Coghill, pastor at Royal City Church since 2010, explained the intentional decision to stop using Volunteer T-shirts as part of the effort to build a community without divisions. Royal City Church staff are expected to eat at least one meal a week as part of the community, and anyone is welcome to join in, regardless of need.

Pastor Coghill also explained that the focus of the meal program is in building relationships. “It’s not just about food. What we emphasize is that our work is about the relationships that happen around the food.” When the doors open an hour before the meal starts, music plays and the art room and games are there for people to use. Before the meal, Coghill will pray—the only overtly Christian moment in the evening—and then tables will be randomly called to come get food, to prevent long lines.

The Life Centre has faced a number of challenges. Although it is supported by other churches and businesses, both financially and in terms of volunteers, the bulk of the work is shouldered by the small congregation of one hundred people who worship and serve meals at their church at 50 Quebec Street. Unexpected problems can add significant stress in addition to the regular challenge of providing meals to so many people.

Two recent events reflect the resilience of the congregation in the face of challenges. When their industrial range oven breathed its last in 2018, the community came together and collected $9,000 in donations in just two weeks (Hallett 2012). In 2019, the city announced that it would be enforcing higher food-preparation standards, requiring that the kitchen be fully renovated to meet current codes and requirements. Meal provision has become more difficult while the renovation is being undertaken. While the benefit of a full commercial kitchen will be significant, challenges of this scale can place great strain on such a small group.

The congregational dynamics can also be daunting. While Royal City Church adheres to the Evangelical Missionary Church of Canada statement of faith and guiding frameworks, a wide range of people are part of Royal City and the Life Centre and serve in different ways. A curious challenge is that those who are formally church members may spend an hour a week at the church service, while others who are not members may be volunteering and engaging in the community for four hours a week or more. It can be difficult to evaluate what membership means with such differences of investment. “Our instinct is to move the formal church-membership requirement down and the requirement for formal church leadership up,” observed Pastor Coghill. Navigating historical structural boundaries such as church membership can be difficult but needs to be undertaken. One example of this navigation is the change in name: as of September 1, 2019, Royal City Church has become Royal City Mission.

While Lakeside is legally separate from Hope House, Royal City has stayed closely intertwined with the Life Centre. What has made the difference? It is impossible to know for sure, but perhaps the size of the congregations and the programs is part of the answer. Since Lakeside has its main location so far away from Hope House, it may be that church members prefer to spend their time volunteering somewhere closer to home. Regardless of the differences, Lakeside Hope House and Royal City Life Centre are two important examples of the usability of old church buildings in the city centre for both regular Sunday worship and as a base for community engagement and service.

The interaction between Hope House and the Life Centre occurs through a meeting every two months that includes leadership from each organization. Dialogue is intended to avoid overlaps, but active, significant collaboration has not been typical to this point in time. While some may argue that cooperation should be clearer and more intensive, it may be that maximizing the freedom for each organization to adapt to its particular niche as fully as possible is of greater benefit than if they became more self-consciously alike.

Thinking About City Structures

As an organization that directly serves the common good in Guelph, Hope House has applied for and received city grants for its operation. These include grants administered by a citizens’ committee that manages a $250,000 pool of funds to be dispersed to various groups. While its status as a non-religious rather than a religious organization may be an important qualification for some potential funders, this is not the case with the city.

Guelph, like any other human community, has religious communities of all kinds among it. Land use, buildings, and connections with city infrastructure mean that there is always some degree of interaction between faith-based organizations and the city of Guelph. The interaction has been quite consistent and usually low key, with little in the way of significant structural engagement. Points of interaction with the city have tended to be point-in-time, concerning building use or zoning or bylaw matters.

The basic framework between faith communities and city administration can be characterized as a live-and-let-live kind of interaction. The work and initiative arise from the FBO side, with secondary support from the city when purposes align. The city may work with Hope House or other agencies like Royal City with regard to homelessness or meal programs, finding ways to tune, fill gaps, and make small adjustments. These programs have led to a strong positive reputation for Hope House at the city and community level. They are visible, active, and touch many needs in downtown Guelph. The Hope House backpack program, for example, has strong support in the wider community, including from city staff and others who may not have a religious affiliation.

Hope House and similar agencies arising from faith communities are often focused on meeting immediate needs. But Guelph is facing longer-term developmental pressures that are well understood on the city-administration side, such as a projected increase of ten thousand people in the downtown population over the next twenty years. What a live-and-let-live relationship between city and church does not translate into, typically, is longer-term, more sustained exchanges involving future needs, strategic planning, or assessments of social capacity. The city does not actively seek out faith communities as part of its strategic solutions or long-term future planning. To meet demanding social challenges in growing cities like Guelph requires the best possible use of resources, including the capacities of faith communities. It is difficult to find any direct evaluation on the part of city staff concerning the carrying capacity or adequacy of the faith communities to support Guelph’s longer-term growth targets. This capacity would include places of worship for people moving to Guelph as well as the increased demand for social supports that a larger population incurs. If Hope House, Royal City, and the many other faith-based or faith-originated care and service groups are any indication, there is room to deepen our understanding of how they fit into these long-term planning and accommodation processes.

Planners tend toward what is most immediate and regular, and this means that developers and the business community are often most well understood from a process and institutional perspective. While FBOs and congregations in downtown areas are often looked at as prime real-estate sites that can be intensified through new residential construction, the role of these communities in providing spiritual and social care and service is not replicated in the new building forms, thus reducing the institutional carrying capacity of the growing community.

When St. Matthias Anglican Church was sold to an apartment developer in 2015, delegations asked the city of Guelph to review how faith communities are represented in the land-use plan. There are notable elements in this report. First, the city concluded that there is adequate land and infrastructure for faith communities for their existing activities and needs and that additional protection or provision is not required. The report noted the “fairly permissive policies” in the Official Plan, with eighteen permitted use types that are open to faith communities looking to build or expand (Jylanne 2018). Second, the report noted that the city is in compliance with provincial requirements and with other municipalities in their treatment of faith communities and land use.

Current studies such as Community Spaces in Faith Places (http://www.communityspacefaithplace. org) demonstrate that faith-based groups shelter many arts and culture groups that are not faith-based, so that a decrease in worship space or congregational space has a much wider impact than previously thought. The city report notes that Markham has a rule-of-thumb ratio of one place of worship for every six thousand residents. It is unclear how the capacity of faith-based organizations in Guelph would work out with its projected increase in residents over the next fifteen years. Will all of the existing capacity remain, to which an additional seven worship spaces will be added? These are important aspects of projected growth and capacity studies for the city of Guelph. Whether millennials or retirees or immigrant families, some of the new residents will desire to participate in religious activities or will need the social supports that FBOs offer. Pressure on Guelph’s resources will increase, as will the hope that resources will increase to meet those challenges.

Insights for Faith Communities and the Care of their Towns and Cities

The two common themes that run through Lakeside, Hope House, and Royal City Life Centre are community and narrowing the social gap between helpers and those who are helped. Everyone interviewed for this case study mentioned the importance of working with the community and building relationships. David Ralph advised that a good foundation for effective outreach is to ensure that leaders have pre-existing relationships in the communities where the work will be done.

The second theme, reducing the social distance between helpers and those helped, is enacted at Royal City by encouraging everyone at the meal to interact together and by replacing the Volunteer T-shirts that created a hierarchy between those serving and those being served. Speaking about the type of culture that he tried to create at Lakeside, David Ralph said that the church should not overstep its bounds of hospitality and that it must be aware of the power structures at play when interacting with marginalized members of society. Hope House purposefully uses the language of “community members” rather than “clients” or “guests,” to remind everyone involved of their “common nature and place [they] share.”

When asked what advice she would give a congregation looking to create a platform similar to Hope House, Jaya James noted the importance of the following:

- Searching for and using community spaces in the form of older churches and other buildings that are becoming available.

- Engaging with the community. It is essential to work with others in the community who are already doing similar things to what you plan to do.

- Looking for opportunities to share back-office support with other independent organizations.

- Knowing the importance of lived experience and ensuring that you really understand—not just intellectually but also emotionally—the problems you hope to address and the kinds of impact they have.

One of the lingering questions for Hope House, organized as a non-religious charity, is the degree to which groups that originate in religious communities are able to sustain their animating core without the formal ties to that religious community. On the other side of that question is whether over the long term Lakeside will continue to fund (by time, interest, social capital, etc.) Hope House as it operates independently. Will Lakeside members continue to invest as much? Another way to think about this is to consider whether Lakeside will be motivated to help another Hope House develop in the future, perhaps with a different mission or focus—such as an aging population, or new issues or needs that arise from population growth. Will Hope House become influenced over time by the ideas and values of those providing alternate sources of funding—government, corporate, and special interest groups?

Most of the dynamics around these questions will occur in the quiet, complex, day-to-day operations of each of these intricately connected organizations, groups, and individuals. Woven deeply into the life of the city, faith-based organizations will shift and change along with the city, sometimes pushing, sometimes pulling, but always adjusting to the changing realities of urban life. Our longterm well-being will depend in important ways on their ability to do that while still retaining the common-good service that has characterized them to this point.

References

Armstrong, K. 2018. “HOPE House Looking into Buying Downtown Home from Lakeside Church.” GuelphToday.Com, December 13. https://www.guelphtoday.com/local-news/hope-houselooking-into-buying-downtown-home-from-lakeside-church-1155688.

Friesen, M. 2017a. “Religion and the Good of the City: Report 1 (Roundtable No. 1).” Cardus, May 1. https://www.cardus.ca/research/social-cities/reports/religion-and-the-good-of-the-city-report-1/.

———. 2017b. “Religion and the Good of the City: Report 2 (Roundtable No. 2).” Cardus, August 17. https://www.cardus.ca/research/social-cities/reports/religion-and-the-good-of-the-city-report-2/.

———. 2017c. Religion and the Good of the City: Report 3 (Roundtable No. 3). Cardus, May 1. https://www.cardus.ca/research/social-cities/reports/religion-and-the-good-of-the-city-report-3/.

Government of Canada. 2017. “Census Profile, 2016 Census (Guelph).” February 8. https://www12. statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD& Code1=3523008&Geo2=CD&Code2=3523&Data=Count&SearchText=guelph&SearchType= Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&TABID=1.

“Guelph’s Lakeside Church Set to Pay $1 Million for Norfolk United.” 2012. Guelph Mercury Tribune, February 8. https://www.guelphmercury.com/news-story/2725883-guelph-s-lakeside-church-setto-pay-1-million-for-norfolk-united/.

Hallett, D. 2012. “Another Guelph Church Changes Hands.” Guelph Mercury Tribune, February 28. https://www.guelphmercury.com/community-story/5862813-another-guelph-churchchanges-hands/.

Hill, V. 2017. “Guelph’s Seven Downtown Stone Churches Inspired Photographer.” Waterloo Region Record, October 13. https://www.therecord.com/news-story/7623256-guelph-s-seven-downtownstone-churches-inspired-photographer/.

Jylanne, J. 2018. “Faith-Based Institutions: Background, Analysis and Trends [Report to Council—January 15, 2018].” City of Guelph. https://guelph.ca/wp-content/uploads/cow_ agenda_011518-1.pdf.

MHBC Planning. 2019. “Cultural Heritage Action Plan [Draft].” City of Guelph. https://guelph.ca/ city-hall/planning-and-development/community-plans-studies/heritage-conservation/culturalheritage-action-plan/.

“Official Plan.” 2018. City of Guelph. https://guelph.ca/plans-and-strategies/official-plan/.

White, R. 2017. “The Stone Churches of Downtown Guelph [Presentation].” https://www. royalcitymensclub.ca/uploads/5/2/8/3/52831869/robert_white_-_stone_churches_-_dec_7.pdf.

Wood Daly, M. 2016. “The Halo Project.” Cardus. https://www.haloproject.ca/phase-1-toronto/.