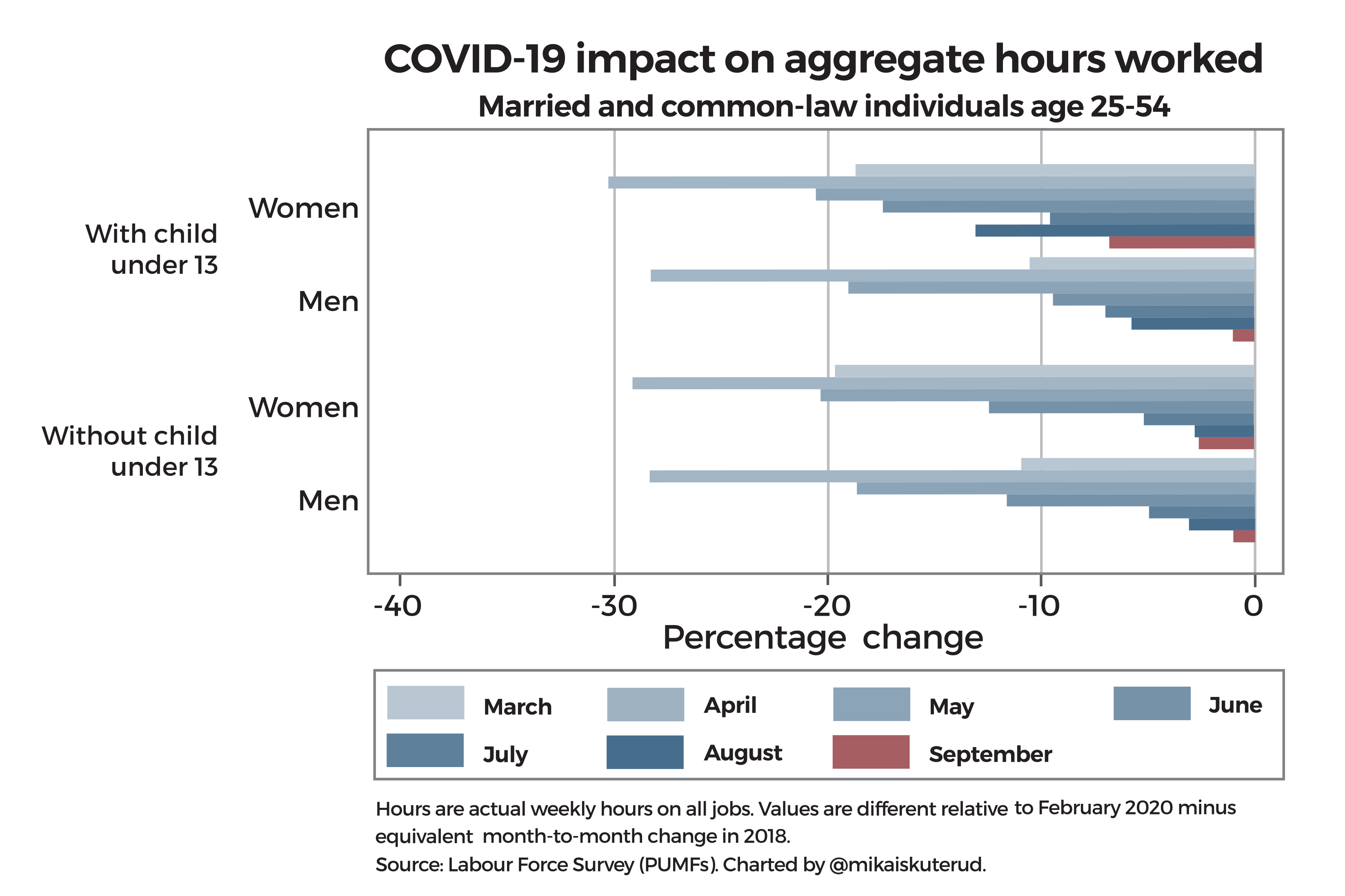

Mothers cannot return to waged work that is not there. A “universal” daycare program does not alter the realities of an economic downturn. Still, data show that mothers’ hours worked in the paid labour force is not recovering as quickly as either men’s or women’s who don’t have children.

Does this disparity indicate a lack of available care, or are there other factors contributing to how families organize paid and unpaid work?

At the same time as students were able to return to schools in September 2020, 93 percent of daycares in Ontario were opened. 1 1 Government of Ontario, “Early Years and Child Care Annual Report 2020,” http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/ childcare/annual-report-2020.html#_bookmarkExpenditures. Daycare centres in Peel Region in Ontario, for example, were at 97 percent of pre-pandemic capacity, yet only 20 percent of child-care spaces in Brampton, a municipality within Peel Region, were occupied. 2 2 Nida Zafar, “Despite Its ‘Childcare Desert’ Label Brampton Daycares Are Only 20 Percent Full Because of the Pandemic,” The Pointer, October 4, 2020, https://thepointer.com/article/2020-10-04/despite-its-childcare-des- ert-label-brampton-daycares-are-only-20-percent-full-because-of-the-pandemic.

This points to something other than daycare availability as the issue. Families are weighing the health considerations of a return to institutional care, be it daycare or schools, and making decisions accordingly.

“No system is truly pandemic-proof, as has been demonstrated in the public school system, in which provinces and school boards are struggling to adapt.”

Philip Cross, senior fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute, argues, “What is keeping women from returning to work is the same lack of demand that is depressing employment for men. Without a better recovery of demand, improved daycare will make little difference. Without a job to return to, parents don’t need daycare for their children. There may very well be good reasons to try to improve daycare in Canada, but its being a ‘magic bullet’ to boost the recovery is not one of them.” 3 3 Philip Cross, “Philip Cross: The Myth of a ‘She-Cession,’” Financial Post, October 2, 2020, https://financialpost.com/opinion/philip-cross-the-myth-of-a-she-cession. This is part of the story. In many cases, however, there is waged work outside the home available, but families are choosing to keep someone at home, and more often than not that someone is Mom. This is not a problem to be solved if this is a decision that families choose to make based on their own needs and preferences.

Another possible explanation involves the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB). During the early stages of the pandemic, the CERB paid workers to stay home. If the CERB is more money than a mother’s hourly wage in the paid labour force, then she may make an informed decision that she prefers to be paid to be with her children rather than place them in child care with its increased risk of contracting the virus. The CERB may have acted as a kind of parental benefit, allowing parents to eschew waged work to do the work of caring for their children. If families are choosing to pull their children out of institutional settings, then the question is, Why would we create more institutional settings rather than provide income supports where needed?

No system is truly pandemic-proof, as has been demonstrated in the public school system, in which provinces and school boards are struggling to adapt. Yet with the help of emergency funding, child-care providers have largely returned to service despite the absence of a universal child-care system.

The Takeaway

There are already signs that the pandemic may shift the way families engage with paid and unpaid labour in the future. Decisions about paid work and parenting are rarely about money exclusively. Mothers and fathers exercise multiple vocations in their lives, concurrently and separately. Sometimes a mom is exclusively working in the home; sometimes she is also in the paid labour force. Every mother, however, is a working mother, and no good can come from a child-care policy that compels participation in the paid labour force for the sake of increasing the GDP. Rather than turning to a one-size-fits-all policy proposal from a bygone era, the federal government should look ahead and focus on providing provinces with flexible multilateral agreements while also seeking a cohesive, coherent, and flexible family policy for Canada as a whole. Giving money to families would mean supporting other child-care options in addition to centres, such as bringing care into the home—a more attractive child-care option for many who face health concerns.

References

- Government of Ontario, “Early Years and Child Care Annual Report 2020,” http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/ childcare/annual-report-2020.html#_bookmarkExpenditures.

- Nida Zafar, “Despite Its ‘Childcare Desert’ Label Brampton Daycares Are Only 20 Percent Full Because of the Pandemic,” The Pointer, October 4, 2020, https://thepointer.com/article/2020-10-04/despite-its-childcare-des- ert-label-brampton-daycares-are-only-20-percent-full-because-of-the-pandemic.

- Philip Cross, “Philip Cross: The Myth of a ‘She-Cession,’” Financial Post, October 2, 2020, https://financialpost.com/opinion/philip-cross-the-myth-of-a-she-cession.