There's been a push for a universal daycare system in Canada for 40 years. All that time, it's been called a "crisis." Now, federal Families, Children and Social Development Minister Jean-Yves Duclos promises we'll get there "eventually." Frankly, if we never do, it will be a decided win for families. This so-called crisis has only ever been one to a thin minority of activists — which is precisely why we don't yet have a universal system. Those who bemoan the lack of a universal institutional daycare system do so on different grounds: it gets mothers of young children working, it helps boost union membership, and — for big business — it creates more workers. In short, those lobbying for a universal system make up an unholy alliance of left and right — and very little of it has anything to do with actual benefits to children. In reality, no research shows that a plurality of children in a country benefit from access to universal institutional daycare. Rather, the opposite is true — there are benefits to targeted programs, which is precisely what the federal government now proposes. Universal daycare supporters generally cite an influential study done in the 1960s in Ypsilanti, Mich., to bolster their claim. The Perry Preschool Project worked with about 58 children for 2.5 hours a day. The child-to-adult ratio was six to one. These were at-risk children whose homes the researchers visited once a week, spending time with the mothers. Tracking the results into the long term, the children who participated in this particular intervention outperformed those who did not. Were we to follow the example of this research, we would have half-day, targeted, small-scale programs for disadvantaged children. The application of this study for a Canada-wide system is so remote as to be irrelevant. Duclos may in fact be aware of the research showing adverse affects from universal systems like Quebec's. Peer-reviewed studies have shown detrimental outcomes for kids there. Behavioural problems among children have risen. The authors of a 2006 study wrote that children "were worse off in the years following the introduction of the universal child care program." They continued: "We studied a wide range of measures of child well-being, from anxiety and hyperactivity to social and motor skills. For almost every measure, we find that the increased use of child care was associated with a decrease in their well-being relative to other children." Mothers also fare poorly. When parents must use daycare (because it's the only funded option), the family experience is limited to getting up early, taking children to care, rushing to pick them up only to feed, bathe and pack them into bed, then getting up early the next morning to do the whole thing again. Meanwhile, increasing costs of daycare are the result of government meddling. When Ontario moved to full-day kindergarten, it pulled three- and four-year-olds out of daycares and into schools. Those older children were used to subsidize the care of younger children, who are more expensive to care for. Many daycares went under, while others increased rates. Good daycare, regardless of who pays for it, is expensive. It's politics, some will say, that we don't yet have universal daycare. That's a different way of saying voters don't want it. This is true. If you ask Canadians what they prefer for a child under six, a strong majority will say it's best that children be at home with a parent. Yet we know many parents must use daycare. Those who struggle to find care generally do, whether it be in a centre, with family or in a neighbour's home — the latter two types of daycare being the kind activists don't appreciate because they can't be easily unionized or regulated. A universal system is an expensive solution in search of a problem. If we never get beyond targeted interventions, Canadians should be thankful.

Bursting the universal daycare bubble

July 5, 2017

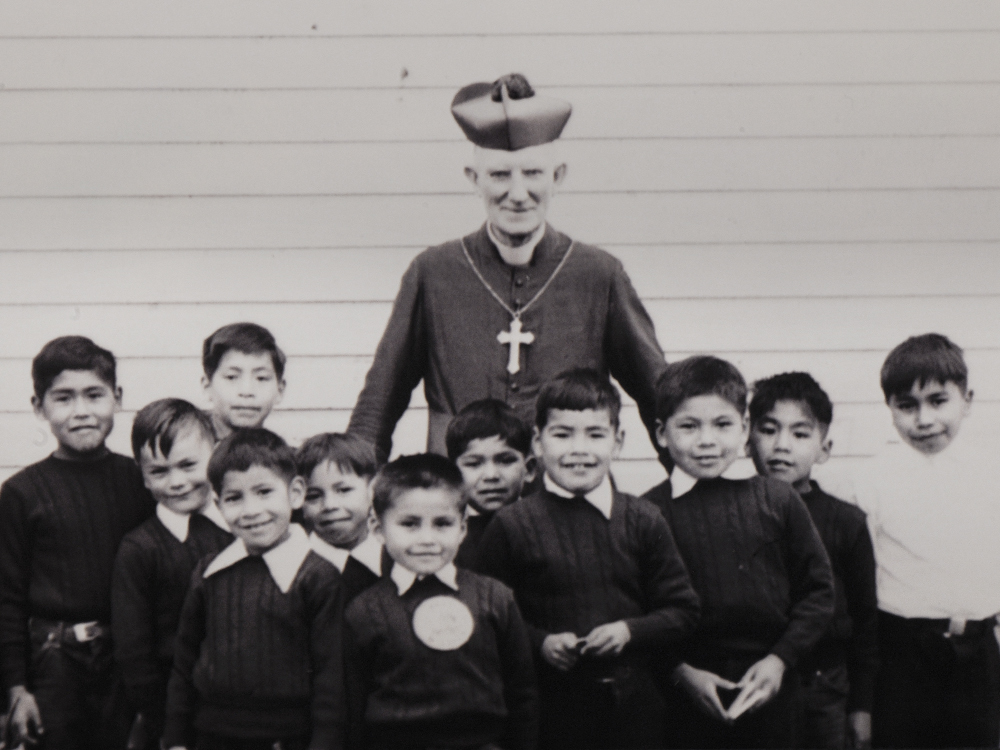

Residential schools seen as ‘major black mark’ in Canadian religious history: poll

"There is consensus on this issue and the fact that it is a dark chapter of our history that we need to own," said Ray Pennings of the think tank Cardus. Click here to read the full article.

June 29, 2017

Ray Pennings: Don’t overlook the contribution faith has made to Canada’s first 150 years

The prevalent Canadian story is one in which faith is relegated to the margins, writes Cardus Executive Vice President Ray Pennings, and many lie in the mushy middle when it comes to faith, but religion has left an imprint on our lives, neighbourhoods and institutions. Click here to read the full article.

June 29, 2017

National Viewpoint – Bursting the universal daycare bubble

To read the full article in the Brandon Sun, click here.

June 29, 2017

Millennials and Faith: Video Interview

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z5pCJRAPtZs&feature=youtu.be

June 29, 2017

Multi-Faith Summit Kicks off with Key Endorsements

OTTAWA — The Faith in Canada 150 Millennial Summit kicked off today with ringing endorsements from two different faith communities: “As you gather just days before the 150th anniversary of Canada, it is a tremendous blessing to see young Canadians, excited about their faith and claiming a space in the public square for healthy and fruitful ongoing dialogue. There is no better time to remind one another, and all those across the country, that faith matters — from coast to coast across this great land of ours. May your voices resonate for years to come!” - His Eminence Thomas Cardinal Collins, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Toronto “It’s important to recognize the role of faith in Canada’s past, present, and future. I’m thrilled to see Canadian millennials gathering in multi-faith friendship for that purpose, especially because they will define the kind of Canada we’ll celebrate at the next milestone in 50 years.” - Balpreet Singh Boparai, legal counsel for World Sikh Organization of Canada and co-chair of the Faith in Canada 150 Cabinet of Canadians Over the next two days, 75 delegates from across the country and representing various religious backgrounds will meet in friendship, exchange views, and learn from each other. These youthful faith leaders will explore questions around building genuine pluralism and the connection between religious life and the common good. In his welcome address, Dr. Andrew Bennett, former religious freedom ambassador and Chair of the Faith in Canada 150 Cabinet of Canadians, called on delegates to affirm a place for the expression of faith in the public square as part of Canada’s sesquicentennial celebration. “Many have bought into the myth that faith is a completely private affair, but it isn’t,” said Dr. Bennett. “Faith is at the core of who we are as people and has helped to make Canada the country it is. It’s important that millennials make that known as we celebrate Canada’s 150th anniversary.” The young people at the summit all had to apply in order to become delegates and either pay their own way or raise support in order to attend. The Millennial Summit will conclude on June 30th. -30- About Faith in Canada 150 Faith in Canada 150 is a program of Cardus that exists to celebrate the role of faith in our life together during Canada’s anniversary celebrations in 2017. For more than 450 years, faith has shaped the human landscape of Canada. It has shaped how we live our lives, how we see our neighbours, how we fulfill our social responsibilities, and how we imagine our life together. To learn more, visit: faithincanada150.ca/about About Cardus Cardus is a think tank dedicated to the renewal of North American social architecture. It conducts independent and original research, produces several periodicals, and regularly stages events with Senior Fellows and interested constituents across Canada and the U.S. To learn more, visit: www.cardus.ca and follow us on Twitter @cardusca. MEDIA INQUIRIES Daniel Proussalidis Cardus - Director of Communications 613.899.5174 dproussalidis@cardus.ca

June 28, 2017

Millennials and Faith

Listen here.

June 28, 2017

Faith will play a role in Canada’s successful future

“You are not my future!” he screamed. I whirled around just in time to see a mother who had been perched on a bench on the corner dart forward and pick up her two daughters. She hid them behind her, three hijabs billowing in the wind as they rushed out of harm’s way. “Not my future!” the man roared again, locking eyes with me as I stood in defiant but shaky silence. The crowd held its breath as he plunged into oncoming traffic and, upon reaching the next sidewalk, turned his wrath on yet another couple. Visibly frightened, they ducked past bystanders, the young mother clutching her hijab around her, willing the light to change so she and her family could flee across the street. I wish I could tell you that I was recounting some historical instance of intolerance and fear. Unfortunately, this incident occurred on the corner of Rideau Street and Sussex Drive just last month, right here in Ottawa. The screaming man would probably be mortified to learn that it is his attitude that is unlikely to be a part of Canada’s future. In fact, as we approach Canada’s 150th anniversary, we will increasingly hear from Canadian millennials that this country’s future can, should, and will include true pluralism. And that includes a very robust understanding of the role of religious faith in common and public life, be it the hijab worn on the street, the turban in a police uniform, or the continued operation of faith-based hospitals, schools and other institutions. This reality will dawn on that screaming man – and others with similar views – in a very real way this week when dozens of millennials from across Canada converge near the offices of think-tank Cardus at Rideau and Sussex for the Faith in Canada 150 Millennial Summit. Far from being your stereotypically apathetic millennials, these young people are active within their faith communities and will take time out of their schedules to discuss the importance of religious freedom and the true nature of pluralism. It’s a bit unusual to convene a group of folks from diverse faith and cultural backgrounds to discuss just how different we are – yet how we all fit together. Frightening encounters such as the one I experienced, however, remind me that the future of Canada depends on our common commitment to enlarge our understanding of dignity and a shared commitment to the common good. The strength of our nation lies in our ability to uphold our freedoms without fear and live peaceably among our differences. The gift of what it means to be Canadian becomes apparent as I bow my head while the Shabbat candles are lit in the kitchen of a generous friend. The importance of religious freedom is evident as I break fast during Ramadan with my generous Muslim neighbours. The beauty of pluralism shines as the Baha’i community ensures that representatives are present at each and every multi-faith gathering we’ve organized across the country. As we mark what it means to be Canadian on July 1, I’m struck by the necessity of remembering that for more than 450 years, faith has shaped the human landscape of Canada. It has shaped how we live our lives; how we relate to our neighbours; how we fulfil our social responsibilities; and, how we share a common life together as Canadians. The young leaders coming together to explore how to move forward in faith and friendship will define a new Canada, the Canada we will celebrate in 50 years on our country’s 200th anniversary. As we mark what it means to be Canadian on July 1, I’m struck by the necessity of remembering that for more than 450 years, faith has shaped the human landscape of Canada. It has shaped how we live our lives; how we relate to our neighbours; how we fulfil our social responsibilities; and, how we share a common life together as Canadians. The young leaders coming together to explore how to move forward in faith and friendship will define a new Canada, the Canada we will celebrate in 50 years on our country’s 200th anniversary.

June 26, 2017

Discomfort with death and grief is a modern ailment

There’s an old story sometimes shared during eulogies about an elderly woman planning her funeral. “Bury me with a fork,” she tells her minister. “Yes, but may I ask why?” he inquires. She explains that as a child, when the dishes were cleared from the table, the forks were occasionally left behind. She came to learn that when the forks remained on the table, a sweet dessert was to follow. “Bury me with a fork because something better is coming.” Modern western society is uncomfortable talking about death. This discomfort is on display in a recent survey by the Angus Reid Institute and Cardus aimed at exploring faith in Canada. About 60 per cent of Canadians surveyed believe in some form of life after death. There’s no consensus on what form that takes. About 55 per cent believe actions in this life have consequences in the life to come, with 57 per cent professing belief in heaven and a minority at 41 per cent stating they believe in hell. The declining presence of religion in public life is surely a contributing factor in our inability to find common language around death, in what is a community experience. Author and journalist Jonathan Kay makes this point in a recent column, noting that the once commonly held idea of an afterlife made grieving tolerable. Kay considers the wide range of public reactions to catastrophe in a secular age where God is no longer welcome at the public podium. He confides that after a recent loss in his own social circle, “I realized that I hadn’t the slightest idea how to talk to my children — or anyone — about death.” Kay is hardly alone. This summer marks the 20th anniversary of Princess Diana’s death. Among the ocean of flowers that pressed against the gates of Kensington Palace, mourners left accompanying notes and cards providing the equivalent of a core sample of the soul of the nation. N.T. Wright, biblical scholar and former Anglican bishop of Durham, summarized the sentiments as “a rich confusion of belief, half-belief, sentiment and superstition about the fate of the dead.” Faced with death, religious communities embody a narrative of hope displayed through corporate rituals and acts of support that are instinctual in compassionate communities. The presence of religious communities also matters beyond the moments of tragedy and public grief, Wright reminds us. Philosophers from Plato forward understood that what we believe about death shapes how we live. Despite the absence of a common narrative around death, we understand grief requires public expression. Yale theologian Miroslav Volf argues that western culture is in a memory boom. Every tragedy is memorialized almost the instant it happens. Volf says the obsession with erecting memorials is in part a response to our short memories amid the frenzied pace of consumer culture and 24-hour news cycles. Volf writes: “We demand immediate memorials as outward symbols because the hold of memory on our inner lives is so tenuous.” Another reason we so rapidly memorialize is our social consensus that remembering and, more concisely, our continuous remembering is “our most basic obligation to do justice.” Remembering is a matter of doing justice. Grief draws us to reflect on meaning. Kay reminds us of the common refrain, in the aftermath of tragedy, to love each other more. “It’s sentimental and unsatisfying,” he writes. “But without God by our side, it’s the best we can do.” Kay argues we find meaning in social connections, investing time and energy in those around us in order to hold on to love. Modern western society could use more, rather than fewer, religious communities integrated into public mourning. Religious communities are invested in the care of the isolated, suffering and dying, motivated by love of neighbour and love of God. They hold on to love, always remembering that the fork remains on the table.

June 25, 2017

Media Contact

Daniel Proussalidis

Director of Communications