Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Workers in Ontario’s long-term care (LTC) homes provide care and support for thousands of seniors every day—but there are not nearly enough of them. Though LTC residents have increasingly acute care needs, there is a worsening shortage of workers who provide care. At the same time, the demand for LTC beds far exceeds supply, and the growing backlog is harming the entire health-care system.

- Compared to ten years ago, LTC residents today are older, have poorer health, and need more support—yet the wages of the workers who care for them have declined.

- Low attraction and retention of LTC workers have created widespread staff shortages, increasing pressure on the remaining workers and putting both residents and staff at risk.

- Ontario’s financial problems mean it is unfeasible for the provincial government to try making the LTC sector more attractive for new and existing workers by raising wages alone; it must also improve workers’ job satisfaction (which is associated with a variety of positive outcomes, including intention to stay, performance, and productivity).

- LTC workers report lower job satisfaction when they feel they are unable to provide quality care to residents, something that has become more challenging as limited staff are stretched thin trying to meet the demands of rising resident acuity. They are particularly frustrated by excessive documentation requirements: overregulation has forced workers to spend time filling out redundant paperwork instead of caring for residents face to face.

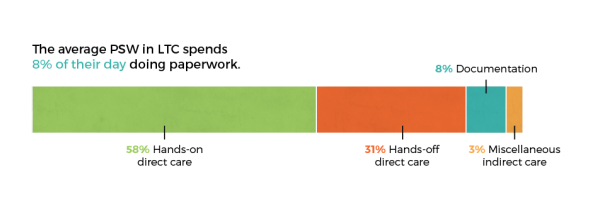

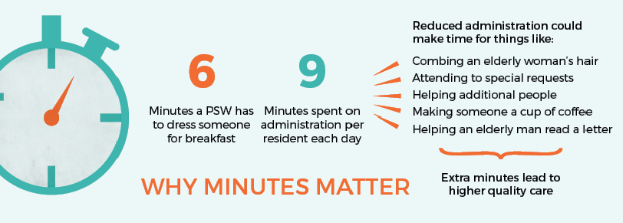

- A time-use study conducted by the union CLAC revealed that in an eight-hour shift at a LTC home, the average personal support worker spent nine minutes on documentation per resident—taking time away from hands-on care.

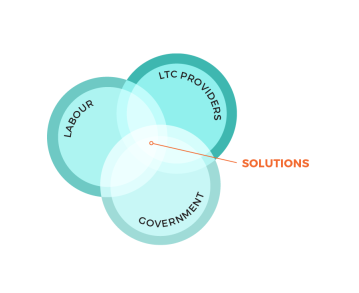

The systemic, multifaceted problems facing workers in Ontario’s LTC sector defy easy solutions, but the industry’s primary stakeholders—government, labour, and employers—can still bring significant improvement to the front lines. We urge government to bring these stakeholders together in order to correctly identify the problem LTC workers face, collaboratively develop solutions to the problem, support the implementation of solutions, and facilitate sustained engagement with the province’s LTC challenges. It’s time to build a better LTC sector for all Ontarians.

Workers in Ontario’s long-term care homes provide care and support for thousands of seniors every day.

But there are not nearly enough of them.

People over Paperwork

Headlines proclaim that worker shortages in Ontario’s long-term-care (LTC) sector are at crisis levels.

1

1

See, e.g., Ron Grech, “PSW Shortage Poses Crisis in Long-Term Care,” The Timmins Daily Press, April 24,

2019, https://www.timminspress.com/news/local-news/psw-shortage-poses-crisis-in-long-term-care; CBC News, “Overloaded and Undervalued, a Crisis for Personal Support Workers,” CBC News, May 22, 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sudbury/personal-support-workers-sudbury-crisis-1.5143707; Ontario Health Coalition, “Long Term Health Care at Situation Critical,” January 21, 2019, https://www.ontariohealthcoalition.ca/index.php/long-term-health-care-at-situation-critical-baytoday-january-21-2019/.

The problem is indeed a serious and multifaceted one. This paper will examine the nature of the challenges facing LTC workers in Ontario and conclude with recommendations for the province’s next steps.

Financial Pressures on Health Care in Ontario

As is the case with any sector dependent on public funding, the fiscal health of the province overshadows the conversation. Ontario’s finances, as has been well established, are a mess. The numbers are staggering: a $3.7 billion deficit in the most recent fiscal year; $324 billion in public debt; interest payments costing taxpayers upwards of $12 billion every year.

2

2

Ontario Treasury Board Secretariat, “Public Accounts of Ontario: Annual Report and Consolidated

Financial Statements 2017–18,” Government of Ontario, 2018, https://www.ontario.ca/page/public-accounts-2017-18-annual-report.

Ontario’s largest expense—by a substantial margin—is health care. Health-sector spending is projected to surpass $61 billion in 2018–19, representing 41 percent of total program spending.

3

3

Financial Accountability Office of Ontario (FAO), “Ontario Health Sector: 2019 Updated Assessment

of Ontario Health Spending,” March 6, 2019, https://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/health-update-2019.

Seniors are a disproportionately expensive category of health-care users: Canadians sixty-five and older use 46 percent of health-cost dollars despite making up only 16 percent of the population. Per capita spending increases with age as well, from an average of $6,400 for those age sixty-five to sixty-nine, to $8,400 for seventy to seventy-four, to $11,500 for seventy-five to seventy-nine, and then nearly doubling to $21,200 for those eighty years and older. Indeed, it is estimated that the cost of population aging alone will increase the country’s health-care spending by $2 billion annually.

The Cost of Population Aging

Canada’s population is aging, raising fears of a demographic crunch that will compound the strain on health-care systems as baby boomers approach retirement age.

4

4

Statistics Canada, “Age and Sex, and Type of Dwelling Data: Key Results from the 2016 Census,” May 3,

2017, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/170503/dq170503a-eng.htm#archived.

Adults over the age of sixty-five now outnumber children under age fifteen for the first time in Canadian history. This sixty-five-plus segment of the population grew four times faster than the population as a whole between 2011 and 2016 (20 percent vs. 5 percent), and the oldest groups have been growing fastest: the proportion of adults age eighty-five and older increased by 19.4 percent, while the number of centenarians (i.e., one hundred years and older) increased by a full 41 percent.

5

5

Statistics Canada, “Census in Brief: A Portrait of the Population Aged 85 and Older in 2016 in Canada,”

May 3, 2017, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016004/98-200-

x2016004-eng.cfm.

In Ontario, the number of seniors is projected to nearly double by 2041.

6

6

Ontario Ministry of Finance, “Ontario Populations Projections Update, 2017–2041,” modified June 25, 2018,

https://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/economy/demographics/projections/

These statistics suggest that Ontario’s health sector faces an influx of more and more patients with more and more expensive needs, increasing pressure on the health-care system.

It is dying, not aging, that is disproportionately expensive. . . . It is significantly more costeffective to care for a senior in LTC rather than in a hospital.

Multiple studies in developed countries have found evidence that it’s not age itself that drives high medical costs among the elderly, but rather their proximity to death—it is dying, not aging, that is disproportionately expensive.

7

7

Alfons Palangkaraya and Jongsay Yong, “Population Ageing and Its Implications on Aggregate Health

Care Demand: Empirical Evidence from 22 OECD Countries,” International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics 9 (2009): 391; Meena Seshamani and Alastair Gray, “A Longitudinal Study of the Effects of Age and Time to Death on Hospital Costs,” Journal of Health Economics 23, no. 2 (2004): 217–35.

This suggests that the additional cost burden that looms over our strained health-care system can be greatly mitigated by ensuring that care in the final years of life is provided in the appropriate setting. It is significantly more cost-effective to care for a senior in LTC rather than in a hospital: according to the Ontario Long-Term Care Association, it costs $175 per day to provide care for a senior in an LTC bed—less than a quarter of the average daily cost of a hospital bed ($750).

8

8

Ontario Long-Term Care Association (OLTCA), “More Care. Better Care. 2018 Budget Submission,” 2018, 8.

In 2011, the North East Local Health Integration Network estimated the cost of caring for seniors in a hospital bed to be more than six and a half times that of caring for them in an LTC bed: $934 and $140 (2019

dollars) respectively. North East Local Health Integration Network, “HOME FIRST Shifts Care of Seniors

to HOME,” August 22, 2011, http://www.nelhin.on.ca/~/media/sites/ne/assets/69a65c95-6177-4adc-b6f2-

ccc3e47cec95/bfdd7682635c42db803e3d46b1dcb2a55.pdf.

The Strain on Long-Term Care

Demand for LTC Beds is Rising

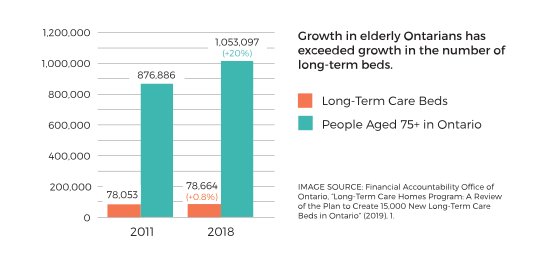

The LTC system, however, is chronically overloaded. Investment in LTC has not kept pace with the growth of Ontario’s aging population—between 2011 and 2018, the number of Ontarians aged 75 and older increased by 20%, while the number of LTC beds in the province increased by only 0.8%.

9

9

FAO, “Long-Term Care Homes Program: A Review of the Plan to Create 15,000 New Long-Term Care

Beds in Ontario,” October 30, 2019, https://fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/ontario-long-term-care-program.

Demand for LTC beds now far exceeds supply. As of early 2019, the average wait time to get into LTC was 142 days (five months), and more than thirty-five thousand people were on the LTC wait list,

10

10

OLTCA, “This Is Long-Term Care 2019,” 2019, 13, https://www.oltca.com/OLTCA/Documents/Reports/

TILTC2019web.pdf

a 55 percent increase since 2015.

11

11

In 2015, the size of Ontario’s LTC waitlist was 22,601. OLTCA, “Long-Term Care That Works. For Seniors. For

Ontario. 2019 Budget Submission,” 2019, 2, http://betterseniorscare.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/OLTCA_Budget_Submission_FINAL.pdf.

Though the province committed in 2018 to adding 15,000 new LTC beds over five years, the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario projected that the wait list will have grown by a further 2,000 Ontarians even after the addition of these new beds.

12

12

FAO, “Long-Term Care Homes Program,” 3.

The rapid growth of LTC wait lists is causing problems throughout Ontario’s entire health-care system. Every day in 2017, an average of 4,233 hospital beds—representing almost 15 percent of inpatient days—were occupied by patients waiting for care elsewhere and accordingly designated alternate level of care (ALC, defined by the Canadian Institute for Health Information as “when a patient is occupying a bed in a facility and does not require the intensity of resources/services provided in that care setting”

13

13

CIHI, “Definitions and Guidelines to Support ALC Designation in Acute Inpatient Care,” https://www.cihi.

ca/sites/default/files/document/acuteinpatientalc-definitionsandguidelines_en.pdf.

). Fully one third of ALC days in Ontario are used for patients waiting for a place in LTC, which cost the province an estimated $170 million in 2017–18.

14

14

FAO, “Long-Term Care Homes Program,” 23–24

One of the most heavily scrutinized problems associated with this backlog is “hallway medicine”—patients waiting in unconventional spaces because no hospital beds are available for them. About one thousand Ontarians could be found waiting to receive hospital treatment in hallways, on emergency-department stretchers, or in other unconventional locations on an average day in 2018.

15

15

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC), “Hallway Health Care: A System Under

Strain—First Interim Report from the Premier’s Council on Improving Healthcare and Ending Hallway

Medicine,” January 2019, http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/publications/premiers_council/report.

aspx#exec_summary

At the same time, the LTC sector is coming under increasing pressure. In 2010, Ontario expanded its Aging at Home Strategy, designed to keep seniors in their homes or communities longer and to lessen the burden of ALC patients on hospitals.

16

16

MOHLTC, “Aging at Home Strategy,” August 31, 2010, https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2010/08/aging-at-home-strategy.html.

Since then, stricter admission requirements for entry into LTC homes have been in effect—while LTC facilities have always provided care for residents who needed more support than they could receive at home, it is now only those with high and very high needs who are eligible for admission into LTC. In addition, downloading of responsibilities from hospitals to LTC has meant that high-acuity patients who formerly would have received care in hospitals now receive care in LTC facilities.

17

17

Eileen E. Gillese, Public Inquiry into the Safety and Security of Residents in the Long-Term Care Homes System: Report, vol. 2, A Systematic Inquiry into the Offences (Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2019), 86, http://longtermcareinquiry.ca/wp-content/uploads/LTCI_Final_Report_Volume2_e.pdf; Ontario

Health Coalition, “Situation Critical: Planning, Access, Levels of Care and Violence in Ontario’s Long-Term Care,” January 2019, http://www.ontariohealthcoalition.ca/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-LTC-REPORT.pdf.

As a result of these transformations in seniors’ care, more residents have been entering LTC at a later stage of their physical and cognitive decline.

Resident Acuity is Increasing

By nearly any indicator, residents in LTC have more acute needs and require more support today than they did eight years ago.

18

18

Carole Estabrooks et al., “Who Is Looking After Mom and Dad? Unregulated Workers in Canadian Long Term Care Homes,” Canadian Journal on Aging 34, no. 1 (2015): 48; Health Quality Ontario (HQO), Measuring Up 2018, 2018, 42, https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/Documents/pr/measuring-up-2018-en.pdf;

OLTCA, “This Is Long-Term Care 2019,” 4.

They are older: the proportion of residents above age eighty-five has risen from 51 percent in 2011 to 55 percent in 2016. LTC residents also suffer from more chronic conditions, with data for the same period indicating higher rates of neurological disease (from 76 percent to 80 percent), heart or circulatory disease (72 percent to 76 percent), antidepressant medication use (51 percent to 55 percent), and diabetes (26 percent to 28 percent).

19

19

HQO, Measuring Up 2018, 47.

Almost every resident (97 percent) has two or more such conditions.

20

20

OLTCA, “More Care. Better Care,” 3.

When seniors need to enter LTC, a form of age-related dementia is often a central factor.

21

21

See Janet E. Squires et al., “Job Satisfaction Among Care Aides in Residential Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review of Contributing Factors, Both Individual and Organizational,” Nursing Research and

Practice (2015): 1–24.

According to the most recent data available, 90 percent of LTC residents have some form of cognitive impairment; two in three have been officially diagnosed with dementia. The proportion of residents with severe cognitive impairment has risen from 29 percent to 32 percent—an increase that represents nearly five thousand people—in the past five years.

22

22

OLTCA, “This Is Long-Term Care 2019,” 5.

Close to half (45 percent) of residents exhibit some form of aggressive behaviour stemming from their condition.

23

23

OLTCA, “This Is Long-Term Care 2019,” 5.

It is likely that age-related dementias will only become more prevalent and more severe among LTC residents as they age: the risk of developing dementia doubles every five years after age sixty-five.

24

24

Alzheimer’s Society, “Risk Factors for Dementia,” Factsheet 450LP, 2016, 4, https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/factsheet_risk_factors_for_dementia.pdf.

Pressure on Long-Term Care Workers is Building

This spike in resident acuity translates to a greater burden on LTC workers. Residents need more help from LTC staff than they did eight years ago, requiring extensive hands-on assistance for basic activities such as eating, dressing, bathing, and toileting. Between 2011 and 2018, the proportion of residents who are almost or completely dependent on LTC workers for these kinds of daily needs rose from 76 percent to 86 percent, meaning that LTC staff must provide significant assistance to nearly thirteen thousand more people. 25 25 HQO, Measuring Up 2018, 47; OLTCA, “This Is Long-Term Care 2019,” 5.

Worker Shortages in Long-Term Care

By every measure, LTC residents need more care, but Ontario has not provided more funding to fill their care needs. LTC homes have struggled to attract and keep frontline workers—including both personal support workers (PSWs) and registered staff such as registered practical nurses (RPNs) and registered nurses (RNs)—to keep up with the increasing demands characterizing the new reality of resident care. Given that PSWs are responsible for upwards of 80 percent of hands-on care for residents in LTC homes, the shortage of these workers in particular is felt acutely on the front lines. 26 26 Whitney Berta et al., “Relationships Between Work Outcomes, Work Attitudes and Work Environments of Health Support Workers in Ontario Long-Term Care and Home and Community Care Settings,” Human Resources for Health 16, no. 15 (2018): 2.

Declining Wages

As resident acuity increases and the demand for care staff grows, however, Ontario has not provided the funding to attract more frontline workers by improving their compensation. The provincial government has not even managed to provide sufficient funding to hold their wages steady. Wage rates for PSWs vary across the province, but percentage wage increases for over 80 percent of Ontario’s LTC homes follow the bargaining results reflected in the collective agreement between Service Employees International Union and Extendicare.

27

27

CLAC, “2019 Public Sector Consultations: Submission to Peter Bethlenfalvy, Treasury Board President,

and Karen Hughes, Deputy Minister, Treasury Board Secretariat,” May 24, 2019, 3.

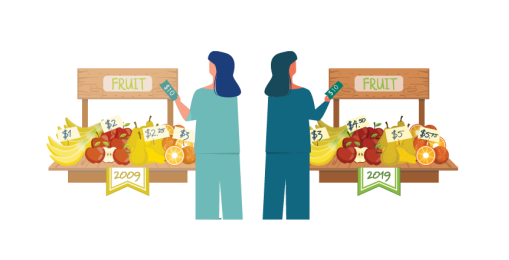

For the PSWs whose wages are tied to this agreement, wage rates have lagged behind the rate of inflation in all but one of the past ten years. In fact, the wage rate for most PSWs has declined by just over 6 percent in real terms since 2009. This means that a PSW working full-time (five eight-hour shifts per week, equal to approximately two thousand hours per year after statutory holidays) is making $2,784 less per year in 2018 than he or she was in 2009.

Long-Term Care Wages at a Glance

In hospitals, meanwhile—which are funded by the same government—wages for PSWs (and RNs) have increased even after adjusting for inflation: a PSW working in a hospital in 2016 was making $3,160 more than he or she was ten years earlier (and $4,000 a year more than a PSW working in LTC). 28 28 CLAC, “Patients First: A Plan to Combat Pressures in Ontario’s Long Term Care System,” 2016, 5. Better benefits, working conditions, and staff support also make hospitals more attractive for workers. 29 29 Gillese, Public Inquiry Report, 2:87–88. This disparity is particularly significant given that hospitals have not experienced the dramatic rise in patient acuity seen in LTC. 30 30 CLAC, “Patients First,” 5

Attraction and Retention Challenges

Given these declining wages, it is unsurprising that LTC is an unattractive field for workers and that reports of staff shortages are widespread. In a 2018 survey of LTC homes conducted by the Ontario Long-Term Care Association, which represents nearly 70 percent of LTC homes in the province, 80 percent of respondents said that they struggled to fill shifts; 90 percent reported that they struggled to recruit staff.

31

31

OLTCA, “This Is Long-Term Care 2019,” 15.

Turnover in the sector is high as well: more than half of PSWs are retained for less than five years.

32

32

AdvantAge Ontario, “2019 Pre-budget Recommendations: Backgrounders,” 1.

The public inquiry launched into Ontario LTC in the aftermath of Elizabeth Wettlaufer’s murdering eight seniors and attempting to murder six others while working as a nurse in LTC highlighted this problem in its final report, pointing out that low LTC staff levels as a result of low government funding, difficulty recruiting staff, and difficulty retaining staff (with hospitals in particular cited as a major source of competition) add to the vulnerability of residents in LTC homes.

33

33

Gillese, Public Inquiry Report, 2:87–88

A 2012 study that surveyed nearly 950 Canadian LTC employees found that 44 percent of frontline care workers reported working short-staffed on a daily basis.

34

34

Albert Banerjee et al., “Structural Violence in Long-Term, Residential Care for Older People: Comparing

Canada and Scandinavia,” Social Science & Medicine 74 (2012): 395.

This trend may represent cause for concern given the abundant evidence that increased staff time improves resident quality of care across multiple domains.

35

35

Veronique M. Boscart et al., “The Associations Between Staffing Hours and Quality of Care Indicators in Long-Term Care,” BMC Health Services Research 18, no. 750 (2018): 1–7.

Staff shortages are particularly problematic for rural LTC homes.

36

36

AdvantAge Ontario, “2019 Pre-budget Recommendations,” 1; Gillese, Public Inquiry Report, 2:253.

Many of these homes are small, with ninety-six or fewer beds: almost half (45 percent) of the province’s small LTC homes are located in rural communities, which often have limited options for those who might otherwise seek out home care or retirement-home living.

37

37

OLTCA, “About Long-Term Care in Ontario: Facts and

Figures,” https://www.oltca.com/oltca/OLTCA/LongTermCare/OLTCA/Public/LongTermCare/FactsFigures.aspx?hkey=f0b46620-9012-4b9b-b033-2ba6401334b4.

Fewer beds in turn means less funding for staff. Given that the demand for LTC staff is high throughout the province, qualified PSWs can choose to stay in large population centres—the main labour supply pool—and will have little difficulty finding local work. Attracting specialized and skilled staff, such as those with behavioural-support training or RNs, can be especially challenging for homes in a small community with a limited supply of workers. This makes it even harder for rural facilities to comply with inflexible provincial legislation regarding staff-to-resident ratios, such as the requirement that every LTC home have at least one RN on site at all times—even though the scope of practice of RPNs, for instance, has expanded significantly since these regulations were drafted.

38

38

OLTCA, “Long-Term Care That Works,” 3–6.

Concerns for Current Long-Term Care Workers

These shortages exacerbate the pressures of providing resident care for the remaining workers. The number and extent of resident care needs remain the same for each shift regardless of how many nurses and PSWs are working that day, so every absence increases the workload—as well as stress and risk of burnout—for those who do show up. 39 39 See Zenobia C.Y. Chan et al., “A Systematic Literature Review of Nurse Shortage and the Intention to Leave,” Journal of Nursing Management 21 (2013): 606; Berta et al., “Relationships between Work Outcomes, Work Attitudes and Work Environments,” 2. The additional demands often exceed the limited capacity of the reduced staff: a 2015 study of LTC homes revealed that 86 percent of care aides (analogous to PSWs) felt rushed, and 75 percent reported having missed at least one task in their previous shift. 40 40 Jennifer A. Knopp-Sihota et al., “Factors Associated with Rushed and Missed Resident Care in Western Canadian Nursing Homes: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Health Care Aides,” Journal of Clinical Nursing 24 (2015): 2818.

Many staff members experienced physical violence, verbal aggression, and unwanted sexual attention from residents on a daily basis.

Staff shortages in LTC homes are also associated with various forms of resident-to-staff violence. A survey of frontline care workers in Canadian LTC homes found that many staff members experienced physical violence (43 percent), verbal aggression (36 percent), and unwanted sexual attention (14 percent) from residents on a daily basis—only 10 percent of respondents said that they had never been subjected to physical violence by a resident. 41 41 Banerjee et al., “Structural Violence in Long-Term, Residential Care,” 393 It is important to note that outbursts of aggression from dementia patients are usually “not true aggression, but a response to something in the person’s environment and an inability to interpret the situation correctly.” 42 42 OLTCA, “This Is Long-Term Care 2019,” 7. For this reason, these actions are usually referred to as “responsive behaviours.” 43 43 Alzheimer’s Society Ontario, “What Are Responsive Behaviours,” https://alzheimer.ca/en/on/We-canhelp/Resources/Shifting-Focus/What-are-responsive-behaviours. Although residents with dementia may not be fully aware of their behaviour, the pain and stress these incidents cause staff can be significant. 44 44 James Brophy, Margaret Keith, and Michael Hurley, “Breaking Point: Violence against Long-Term Care Staff,” New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 29, no. 1 (2019): 10–35. Staff shortages heighten the risk of aggression for frontline workers. While “the one-to-one attention and care that comes from having more staff can help to alleviate some of the triggers that influence aggressive behaviour,” 45 45 OLTCA, “More Care. Better Care,” 6. residents with dementia exhibit more agitated behaviours when they become uncomfortable or are left alone. 46 46 Banerjee et al., “Structural Violence in Long-Term, Residential Care,” 390–91. Inadequate staffing and insufficient time have been associated with resident-to-staff violence 47 47 Adelheid Zeller et al., “Aggressive Behavior of Nursing Home Residents Toward Caregivers: A Systematic Literature Review,” Geriatric Nursing 30, no. 3 (2009): 177; Brophy, Keith, and Hurley, “Breaking Point,” 19–20. —indeed, the top recommendation to address resident aggression from frontline care workers was increased staffing. 48 48 Banerjee et al., “Structural Violence in Long-Term, Residential Care,” 395.

Reduce Strain by Addressing Excessive Documentation Problem

The current state of LTC calls for more funding from the province. More workers are necessary if residents’ care needs are to be met, and the province will be unable to attract quality care workers to the LTC sector if working conditions and wages continue to decline. It is equally important that the province retain the workers it already has. Providing them with just compensation for their work is critical. Given the province’s poor fiscal health, however, the government would be prudent to consider making the non-monetary aspects of LTC employees’ work more attractive as well.

Long-Term Care is Not Just a Job

Indeed, for LTC workers, caring for residents is more than a job. A recent systematic review of careaide research found that the top reason for entering the profession was a “desire to help or inclination to work with people.” 49 49 Sarah J. Hewko et al., “Invisible No More: A Scoping Review of the Health Care Aide Workforce Literature,” BMC Nursing 14, no. 38 (2015): 6. Study after study has shown that the LTC workforce is motivated by a personal passion for the nature of the work itself. For frontline staff, caring for the residents has immense intrinsic value, and evidence suggests that this is enough to keep them in their jobs even when extrinsic rewards like wages and benefits are relatively poor. 50 50 See, e.g., Shereen Hussein, “‘We Don’t Do It for the Money’ . . . The Scale and Reasons of Poverty-Pay Among Frontline Long-Term Care Workers in England,” Health and Social Care in the Community 25, no. 6 (November 2017): 1817–26; Estabrooks et al., “Unregulated Workers”; Hewko et al., “Invisible No More,” 6; Montague, Burgess, and Connell, “Attracting and Retaining Australia’s Aged Care Workers: Developing Policy and Organisational Responses,” Labour & Industry 25, no. 4 (2015): 293–305; Douglas A. Singh, Effective Management of Long-Term Care Facilities (Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2010), 430; Morgan, Dill, and Kalleberg, “The Quality of Healthcare Jobs.” This “hedonic wage” phenomenon is not limited to the LTC sector: there are workers in every field who are willing to accept less pay if they are highly satisfied with other aspects of their jobs.

Job Satisfaction in Long-Term Care

Yet the inverse is also true, particularly among frontline care workers: employees who are dissatisfied with their jobs are more likely to leave. There is evidence to suggest that burnout

51

51

The characteristics of burnout are typically understood to include “emotional exhaustion (depletion of emotional resources and diminution of energy), depersonalization (negative attitudes and feelings as well as insensitivity and a lack of compassion towards service recipients) and a lack of personal accomplishment (negative evaluation of one’s work related to feelings of reduced competence).” Natasha

Khamisa, Karl Peltzer, and Brian Oldenburg, “Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes Among Nurses: A Systematic Review,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 6 (2013): 2214–40.

and lack of job satisfaction are a bigger threat than insufficient wages for the PSW workforce in Ontario. In a survey conducted by the Ontario Personal Support Workers Association, for example, PSWs who left the field were more than twice as likely to say that they did so because of burnout than because of pay issues; among those who said they were unhappy with their job, staffing issues were more likely to be listed as a cause of job dissatisfaction than pay scale.

52

52

Joanne Laucius, “‘We Are in Crisis’: Personal Support Workers Are the Backbone of Home Care in Ontario—and There Aren’t Enough of Them,” Ottawa Citizen, July 13, 2018, https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/when-the-backbone-is-broken.

This is consistent with widespread evidence that job satisfaction is closely tied to turnover among care workers: research has consistently shown that job satisfaction is among the most important predictors of frontline care workers’ intention to leave.

53

53

Squires et al., “Job Satisfaction Among Care Aides,” 2; Mary Halter et al., “The Determinants and Consequences of Adult Nursing Staff Turnover: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews,” BMC Health Services Research 17, no. 824 (2017): 13–14; Chan et al., “A Systematic Literature Review of Nurse Shortage and the Intention to Leave,” 609.

High rates of turnover bring significant human-resources costs to LTC homes, including those associated with vacancy (e.g., hiring third-party agency staff to fill shifts), recruiting, hiring new staff, training and orientation, learning curves (getting new hires up to full productivity), and termination.

54

54

Yin Li and Cheryl B. Jones, “A Literature Review of Nursing Turnover Costs,” Journal of Nursing Management 21 (2013): 405–18.

Turnover is particularly problematic in LTC since it is not only expensive but also affects continuity of care. Research confirms that both lower levels of staff turnover and care workers having more years of experience in their current LTC home are associated with improved quality of care for residents.

55

55

Castle and Engberg, “Nursing Home Staff Turnover: Impact on Nursing Home Compare Quality Measures”; Boscart et al., “Associations Between Staffing Hours and Quality of Care Indicators in Long-Term Care.”

Turnover combines with staff shortages to create a harmful feedback loop in LTC: as workers leave and shifts go unfilled, the workload of the remaining staff increases. With a home’s already-overloaded workforce stretched even thinner, levels of stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction rise—making workers more likely to leave.

56

56

See Stephanie A. Chamberlain et al., “Individual and Organizational Predictors of Health Care Aide Job Satisfaction in Long Term Care,” BMC Health Services Research 16, no. 577 (2016): 7; Chan et al., “A Systematic Review of Nurse Shortage and the Intention to Leave”; Squires et al., “Job Satisfaction Among

Care Aides.”

If Ontario wants to attract and maintain an effective LTC workforce, then, it is critical that the province find ways to improve care workers’ job satisfaction. Again, this does not have to be limited to extrinsic aspects of LTC workers’ jobs—in fact, a recent systematic review of research on care aides’ job satisfaction found that satisfaction with salary and benefits was not as important a factor as empowerment, autonomy, facility resources, and workload. 57 57 Squires et al., “Job Satisfaction Among Care Aides,” 17 Ontario has much to gain from helping LTC workers have a better and more fulfilling work life. In addition to increasing intention to stay, higher job satisfaction increases efficiency among the LTC workforce as in other sectors, with research demonstrating that care staff’s job satisfaction is associated with greater positive work outcomes, such as performance and productivity. 58 58 Berta et al., “Relationships Between Work Outcomes, Work Attitudes and Work Environments,” 4; see also Chamberlain et al., “Individual and Organizational Predictors of Health Care Aide Job Satisfaction,” 2.

Facilitating Job Efficacy

Given the high intrinsic value that LTC workers ascribe to their work, it is unsurprising that their job satisfaction is closely connected to their perceptions of how well they are doing their jobs. Indeed, a recent study of Canadian care aides working in LTC found unusually high levels of efficacy—that is, “the sense that their work is meaningful and has purpose”—among this workforce. 59 59 Estabrook et al., “Unregulated Workers,” 53–54. There is widespread evidence that job satisfaction in the LTC sector is linked to perceptions of the quality of care provided to residents; both intrinsic job satisfaction and capacity to care have been found to increase intention to stay. 60 60 Rachel Barken et al., “The Influence of Autonomy on Personal Support Workers’ Job Satisfaction, Capacity to Care, and Intention to Stay,” Home Health Care Services Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2018): 294–312. In other words, LTC workers are more satisfied with their work and are less likely to leave their jobs when they feel they have the time and support to care for their residents well.

Conversely, LTC workers report not only dissatisfaction with their jobs but also significant personal distress when they feel they are unable to provide good care for the residents. 61 61 Squires et al., “Job Satisfaction Among Care Aides,” 2. Stephanie Chamberlain et al., “Influence of Organizational Context on Nursing Home Staff Burnout: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Care Aides in Western Canada,” International Journal of Nursing Studies 71 (2017): 67; Knopp-Sihota et al., “Factors Associated with Rushed and Missed Resident Care,” 2816; Susan Braedley et al., “We’re Told, ‘Suck It Up’: Long-Term Care Workers’ Psychological Health and Safety,” Ageing International 43, no. 1 (March 2018): 91–109. The perception that residents are receiving substandard care is alarmingly widespread among the LTC workforce, with care aides consistently reporting not having enough time or staff to get all the necessary tasks done. 62 62 See Anastasia A. Mallidou et al., “Health Care Aides Use of Time in a Residential Long-Term Care Unit: A Time and Motion Study,” International Journal of Nursing Studies 50 (2013): 1229–39; Brophy et al., “Breaking Point,” 19–20; Knopp-Sihota et al., “Factors Associated with Rushed and Missed Resident Care.” Missed care is associated with adverse outcomes for residents, including mortality, pressure ulcers, and medication errors. 63 63 Knopp-Sihota et al., “Factors Associated with Rushed and Missed Care,” 2816. In one study, fully 41 percent of frontline LTC workers said that all or most of the time, they felt “inadequate because the residents are not receiving the care they should.” 64 64 Banerjee et al., “Structural Violence in Long-Term, Residential Care,” 396. As LTC staff face increasing pressure to provide more-demanding care with fewer resources, this situation is unlikely to improve.

Personal, Hands-On Care and the Administrative Burden

The many LTC workers who are driven by a deep personal passion for resident care describe the changing nature of LTC work as frustrating and demoralizing. As resident acuity rises and the same number of care workers are responsible for a more-demanding workload, staff find themselves forced to rush through their shift to ensure residents’ basic physical needs are met. Care in LTC homes is now consistently reported to be task-focused rather than patient-centred, resembling an assembly line of resident care. 65 65 See, e.g., Knopp-Sihota et al., “Factors Associated with Rushed and Missed Resident Care,” 2825; Brophy et al., “Breaking Point,” 21. As a result, it is usually the personal, humanizing aspects of care that are neglected when homes are short on time and staff. When LTC workers describe the impact of their burgeoning workload on their work life, they frequently cite their disappointment at not having enough time for “extra” care—things like emotional care and developing relationships with residents. Since increased social and cognitive stimuli have been linked to improvement in older residents’ happiness and quality of life, it is not only carers’ quality of work life that suffers under these circumstances but residents’ well-being as well. 66 66 See Mallidou et al., “Health Care Aides Use of Time,” 1232–34; Knopp-Sihota et al., “Factors Associated with Rushed and Missed Resident Care,” 2816; Chamberlain et al., “Influence of Organizational Context on Nursing Home Staff Burnout,” 65; Margaret P. Calkins, “Evidence-Based Design for Dementia: Findings from the Past Five Years,” Long-Term Living 60, no. 1 (2011): 42–45; Brophy et al., “Breaking Point.”

LTC workers often report that the excessive documentation responsibilities that have emerged as part of the new regime are particularly frustrating. 67 67 See, e.g., Gillese, Public Inquiry: Report, 2:88–93; AdvantAge Ontario, “2019 Pre-budget Recommendations: Backgrounders,” 2; CLAC, “Patients First,” 6–8; OLTCA, “Long-Term Care That Works,” 11–13. The 2010 Long-Term Care Homes Act introduced new information-gathering and documentation requirements for LTC staff. Partly as a result of this legislation—widely considered to be among the strictest of its kind in the world—PSWs and registered staff have experienced a substantial increase in their charting responsibilities in addition to their growing care workload. 68 68 OLTCA, “Long-Term Care That Works,” 11–13; Gillese, Public Inquiry: Report, 2:88–93. Accurate, complete documentation is a critically important aspect of proper patient care. Redundant and unnecessary documentation, however, not only detracts from hands-on resident care but also demoralizes care workers. The new regulations of the 2010 Act, for example, required that LTC staff complete extra reporting in addition to what was already mandated by professional colleges and standards of practice. 69 69 OLTCA, “Long-Term Care That Works,” 12. Substantial overlap across various incident reports and resident assessments also means that the same information is frequently recorded in multiple places—duplication that unnecessarily consumes valuable staff time and clutters record systems with redundant data. 70 70 CLAC, “Patients First,” 6–8.

The immense regulatory burden in LTC is debilitating for frontline staff. As the Wettlaufer inquiry report noted, “Long-term care homes are the most regulated area of healthcare in the province. Despite limited resources, the staff in these homes must meet the regulatory dictates and provide care for residents with ever-increasing acuity.” 71 71 Gillese, Public Inquiry: Report, 1:14 Overregulation has combined with LTC’s funding structure to create a system that puts paperwork before people, and nurses and PSWs frequently report having to work unpaid past the end of their shift to get all their charting done. 72 72 See CBC News, “Nursing Home Resident Says Support Workers ‘Being Run Off Their Feet,’ Need More Staffing,” CBC News, February 1, 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/ontario-long-term-care-facility-psw-shortage-1.5003312; Gillese, Public Inquiry: Report, 2:88; OLTCA, “LongTerm Care That Works,” 13 LTC homes receive some funding directly from the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, but most of their funding is administered via the LHINs (local health integration networks). The LHIN funds are provided through four envelopes.

The more time LTC staff spend on documentation, the less time they have for hands-on resident care. Yet since funding is based on documented acuity, frontline staff must ensure all charting requirements have been thoroughly completed or risk their home losing funding.

The amount a home receives in its nursing and personal care envelope is calculated according to the acuity of its residents—that is, how demanding their care needs are—such that more funding is provided for residents with more complex health problems. For homes that struggle to maintain a staff roster sufficient to provide for residents’ increasingly acute needs, then, thoroughly documenting every resident’s acuity is critical. Yet the charting procedures involved in this process are extensive. Each resident’s acuity is assessed when he or she is admitted to an LTC facility and updated quarterly thereafter using an electronic tool called the Resident Assessment Instrument Minimum Data Set. It is intended to be comprehensive—including information about a resident’s health, medical information, mood, behaviour, mobility, food and fluid intake, continence, dressing, and bathing—and is accordingly very time-consuming to complete. It is estimated that charting for this assessment and the Resident Assessment Protocols, another common report, consumes over one million hours of care per year. 73 73 Gillese, Public Inquiry: Report, 2:88–92; OLTCA, “Long-Term Care That Works,” 11–13.

In addition to submitting data to the ministry, the LHINs, and Health Quality Ontario at monthly, quarterly, and annual intervals, Ontario’s LTC homes must be prepared to make patient information available for unscheduled inspections. The average LTC facility is subject to forty-three days of rigorous inspection per year, despite the fact that the vest majority of homes are in good standing according to Ministry data. The more time LTC staff spend on documentation, the less time they have for hands-on resident care. 74 74 OLTCA, “Long-Term Care That Works,” 11–13. Yet since funding is based on documented acuity, frontline staff must ensure all charting requirements—even those that may be redundant or excessive, such as going beyond those required by professional colleges and standards of practice 75 75 OLTCA, “Long-Term Care That Works,” 13. —have been thoroughly completed or risk their home losing funding. Nurses and PSWs have long checklists of detailed resident information to record, but the widespread lack of consistency surrounding data-entry requirements means that valuable care-worker time is frequently wasted documenting information that had already been recorded for another process or by another staff member. LTC staff who have too many tasks to do in too little time, or who are working short, or both, are confronted with the moral dilemma of prioritizing paperwork over the residents in front of them. If they do not do so, they risk losing funding and making it even more challenging to provide care in the future. 76 76 See CLAC, “Patients First,” 6 Moreover, the current funding structure means that LTC homes, somewhat paradoxically, face a reduction in funding if resident outcomes improve—a loss of income that underfunded LTC homes can ill afford. 77 77 AdvantAge Ontario, “The Challenge of a Generation: Meeting the Needs of Ontario’s Seniors,” 2019 Provincial Budget Submission, http://www.advantageontario.ca/AAO/Content/Resources/Advantage_Ontario/2019-PB-Advocacy-Pub.aspx.

Again, documentation is undoubtedly a key component of properly delivering care. But as important as it is to record the health information of residents accurately, it is equally important to acknowledge the limits of data and metrics. The models by which points of information are gathered and analyzed (or, sometimes even more importantly, deemed insignificant and left unexamined) often come with biases and consequences that are hidden from view. Measuring the wrong things in the wrong way can have significant costs. 78 78 See Jerry Muller, The Tyranny of Metrics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018); Cathy O’Neil, Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (Largo, MD: Crown, 2016). These problems cannot be addressed simply by trying to collect more data; indeed, such an approach may very well make the situation worse.

As important as it is to record the health information of residents accurately, it is equally important to acknowledge the limits of data and metrics.

Nor is turning to digital systems in the hope of improving accuracy and efficiency the solution: evidence on whether the adoption of health information technology improves patient outcomes overall, for instance, remains mixed. 79 79 See, e.g., Seth Freedman, Haizen Lin, and Jeffrey Prince, “Information Technology and Patient Health: An Expanded Analysis of Outcomes, Populations, and Mechanisms,” Social Science Research Network, paper no. 2445431 (2014): 1-35; Jeffrey S. McCullough, Stephen T. Parente, and Robert Town, “Health Information Technology and Patient Outcomes: The Role of Information and Labor Coordination,” The RAND Journal of Economics 47, no. 1 (2016): 207–36; Jeffrey S. McCullough, Michelle Casey, Ira Moscovice, and Shailendra Prasad, “The Effect of Health Information Technology on Quality in U.S. Hospitals,” Health Affairs 29, no. 4 (April 2010): 647–54; Goldzweig et al., “Electronic Patient Portals: Evidence on Health Outcomes, Satisfaction, Efficiency, and Attitudes: A Systematic Review,” Annals of Internal Medicine 159, no. 10 (2013): 677–87; Leila Agha, “The Effects of Health Information Technology on the Costs and Quality of Medical Care,” Journal of Health Economics 34 (2014): 19–30. While some LTC homes have introduced new technology designed to make documentation processes more efficient, this technology is not available for all LTC facilities. For those that do have electronic documentation systems, partial adoption and inconsistent accessibility can be new sources of frustration: redundant data entry for digital and paper-based systems, time wasted trying to overcome computer problems when the system does not work as designed, or erratic access to wireless internet, for example. 80 80 See CLAC, “Patients First,” 9.

The Wettlaufer case is a tragic illustration of the limitations of LTC data with respect to preserving resident safety. In the aftermath of Wettlaufer’s confession, the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care investigated whether her crimes could have been detected by analyzing LTC home data, developing several statistical models designed to identify higher-than-expected mortality rates based on residents’ health data. Yet in the LTC Inquiry Report, expert witnesses emphasized that “it would have been ‘virtually impossible’ to detect the Offences that Wettlaufer committed using any of the [Ministry] models.” More documentation would not have enabled the authorities to detect or stop Wettlaufer’s murders: “Following Wettlaufer’s confession, Ministry inspectors ‘plotted all shifts that [Wettlaufer] worked and correlated them with the deaths.’ However, the Ministry inspectors acknowledged that even this review ‘didn’t tell us really anything’ in respect of the Offences.” Neither could this problem have been solved with more data collected through more mandatory documentation: “We don’t have that data, and I think even if we did, it would produce an enormously complex model. . . . I would be skeptical that that much extra data would be a useful exercise.” 81 81 Gillese, Public Inquiry: Report, 3:157–65.

It is clear that trying to collect ever-more data on LTC residents—which by extension means increasing the documentation responsibilities of frontline care staff—is by no means certain to improve residents’ quality of life. There is, however, an overwhelming abundance of evidence that increasing hands-on direct care does help residents. Higher staffing levels in residential LTC and more care-worker time with residents has been linked to improvement in resident health and well-being across a wide range of categories: reduced pressure ulcers, fewer urinary tract infections, decreased physical restraints, fewer falls, less decline in assistance with daily living, and improved resident satisfaction. 82 82 John F. Schnelle et al., “Relationship of Nursing Home Staffing to Quality of Care,” Health Services Research 39, no. 2 (2004): 225–50; Margaret J. McGregor and Lisa A. Ronald, “Residential Long-Term Care for Canadian Seniors: Nonprofit, For-Profit or Does It Matter?” IRPP Study 14 (January 2011): https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/study-no14.pdf; Knopp-Sihota et al., “Factors Associated with Rushed and Missed Care,” 2816; AdvantAge Ontario, “2019 Pre-budget Recommendations: Backgrounders,” 3; Kathryn Hyer et al., “The Influence of Nurse Staffing Levels on Quality of Care in Nursing Homes,” The Gerontologist 51, no. 5 (2011): 610–16; Nicholas G. Castle, “Nursing Home Caregiver Staffing Levels and Quality of Care: A Literature Review,” Journal of Applied Gerontology 27, no. 4 (2008): 375–405; Karen Spilsbury et al., “The Relationship Between Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review,” International Journal of Nursing Studies 48, no. 6 (2011): 732–50; Haizhen Lin, “Revisiting the Relationship Between Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes: An Instrumental Variables Approach,” Journal of Health Economics 37 (2014): 13–24; Boscart et al., “Associations Between Staffing Hours and Quality of Care Indicators.”

CLAC Long-Term Care PSW Time-Use Study

In light of the increasing pressures in the LTC sector, CLAC (Christian Labour Association of Canada) developed a short-term research project to examine the impact of these systemic challenges for Ontario’s LTC workers on the ground. CLAC members regularly express their frustration at having to fill in redundant and excessive paperwork while struggling to meet the increasing demands of resident care. CLAC initiated this observational study as a step toward illuminating the administrative burden of overregulation on LTC workers and the related issues driving the alarming rates of burnout, job dissatisfaction, absenteeism, staff shortages, and turnover CLAC members experience in the LTC sector.

Quantitative time-use data for PSWs in LTC was gathered by a CLAC researcher in summer 2018. Four LTC facilities in the Hamilton-Niagara-HaldimandBrant LHIN, representing a mix of both for-profit and non-profit homes, agreed to participate in the study. At each of these homes, a steward or management team identified an “effective” PSW to be shadowed by the CLAC researcher; the researcher recorded this PSW’s activities over the course of an eight-hour shift, using a time log and a stopwatch to track how much time was spent on each activity. A PSW steward accompanied the researcher to clarify the nature of care tasks and ensure the time-use data was captured as accurately as possible. The CLAC researcher observed and tracked three shifts at each home—morning, evening, and night—to gather a total of ninety-eight hours of data.

CLAC members regularly express their frustration at having to fill in redundant and excessive paperwork while struggling to meet the increasing demands of resident care.

Analysis of these data revealed that PSWs spent an average of ninety-six minutes per resident per day on direct resident care. Of direct care time, sixty-two minutes were spent on hands-on activities (e.g., feeding, toileting, mobility assistance, bathing, changing clothing, social engagement) and thirty-four minutes on hands-off care (preparing for direct care, e.g., fetching medication and bath products, changing bed linens, serving food). An average of three minutes per resident per day was spent on miscellaneous indirect care (such as reviewing policy or care plans). Documentation or charting, meanwhile, took up approximately nine minutes per day for each resident; the average PSW spent thirty-two minutes of his or her eight-hour shift 83 83 After factoring in breaks. on documentation. Due to the nature of this study, this did not include time PSWs spent on documentation after their shifts had ended, though the researcher noted that this was significant in some cases.

This study was conducted on a small scale and as such is subject to important limitations. It is possible that the presence of an observer led to differences in worker behaviour. Since the research took place over a short period of time, it was not possible to compare the administrative burden at time of observation to other time periods or to measure its proportionate change in size over time. The sample was not large, consisting of a small number of homes confined within a single geographic region; results may not be generalizable to other LTC facilities in Ontario.

Nevertheless, it is reasonable to infer that these findings are an accurate reflection of reality for many PSWs in LTC. The researcher spent a substantial amount of time observing multiple staff members in a variety of homes. The findings of this observation project are also consistent with the evidence discussed above, which was drawn from a wide range of rigorous studies, as well as with anecdotal reports from care workers in the industry.

Numbers in Context: Assembly Line of Care

Although thirty-two minutes may not seem like much time at first glance, the demands on care workers’ time have become so pressing that every minute counts. The morning rush at LTC homes illustrates this point well. In January 2018, the private-sector union Unifor drew attention to the time constraints on LTC workers through a social-media campaign that challenged the public to complete their morning routine in six minutes—the average amount of time available for PSWs in Ontario to rouse and prepare each LTC resident in the morning. As one PSW remarked of the Six Minute Challenge: “When you have six minutes to get a single person ready, there’s no way you can get that person ready in a dignified way. There’s no way that person is feeling like themselves, feeling good about themselves. . . . It just feels so wrong.” 84 84 Jackie Dunham, “Six Minute Challenge: Can You Get Ready as Fast as Nursing Home Residents?” CTV News, January 10, 2018, https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/six-minute-challenge-can-you-get-ready-as-fastas-nursing-home-residents-1.3753212.

Maximizing efficiency is a useful goal for tasks like manufacturing cars, but to treat the work of caring for people the same way as the work of an assembly line is profoundly dehumanizing for both residents and care workers. LTC homes are not factories, nor should the care their workers provide be treated as such. It is imperative that Ontario pursue solutions to the systemic problems that have allowed assembly-line characteristics to influence its LTC sector. In the meantime, any step that improves the frontline-care situation should be taken, no matter how small it may appear. Resident care should never have become a matter of minute-by-minute task management, but any extra minute that can be devoted to resident care is a victory in the province’s broken LTC system.

Recommendations

The challenges facing LTC in Ontario do not have easy solutions. The LTC system is crippled by a series of deep, multifaceted, and interconnected issues that cannot be resolved without sustained engagement with all relevant stakeholders and substantial policy changes. While we do not believe there is a simple, “silver-bullet” answer to LTC’s problems, we are convinced that there are realistic steps Ontario can take that can—and will—significantly improve the situation on the ground. We therefore offer the following broad recommendations, which we urge the government to consider and pursue as quickly as possible for the sake of our LTC sector:

1. CORRECTLY IDENTIFY THE PROBLEM. If Ontario is serious about improving the well-being of workers and residents in its LTC sector, it must first acknowledge that the current state of LTC poses serious problems for workers and that this challenge manifests itself in particular ways. We note four interrelated areas where this challenge exists:

- Wages: the sector has seen pressure related to an increase in minimum wages, where the difference between predominant wages in the sector and the minimum wages have shrunk at the same time that the difference between LTC and the hospital sector has grown.

- Access to technology: there is a significant disparity between homes in access to technology that could lower the administrative burden on staff.

- Lack of consistency in data entry and redundancy in data collection: determining which data are necessary for better health outcomes and providing a clear-eyed audit of the cost-benefit analysis of collecting data remain key challenges.

- Attraction to and retention in the LTC sector: the ability to attract and retain a skilled labour force—and the factors related to both attraction and retention—need to be identified and addressed.

Providing a forum for addressing these challenges will demonstrate that the government is listening and responsive to the voices of those on the front lines of LTC, who for years have been pleading with the province to recognize the challenges they confront on a daily basis.

2. SUPPORT LTC STAKEHOLDERS’ EFFORTS TO COALESCE AROUND THE PROBLEM AND DEVELOP AND IMPLEMENT SOLUTIONS. Ontario’s LTC workforce has three main groups of stakeholders: labour, representing the workers themselves; employers, who own and operate LTC facilities; and government, which provides the bulk of the funding for LTC homes and workers’ wages. Many stakeholders have been working, both independently and in collaboration with one another, to address the issues facing LTC workers for years. Given government control over legislation and public funding, it is crucial that the government of Ontario be actively engaged in these efforts as well—including by fulfilling its leadership role in bringing stakeholders together. Sustainable solutions can be developed only when all actors are involved. An example of this kind of collaborative engagement on important issues is the Infrastructure Health and Safety Association: employers, labour, and government work together to promote worker safety throughout Ontario. 85 85 Infrastructure Health and Safety Association, https://www.ihsa.ca/. We recommend that the provincial government bring together a similar group for LTC.

3. SUPPORT THE RECOMMENDED SOLUTION TO THE PROBLEM. When developing policy responses to the challenges confronting LTC workers, take seriously the recommendations offered by those who know LTC and the issues it faces best. We urge government, labour, and employers to commit to being part of the process of seeking appropriate policy solutions to the challenges that LTC workers face, especially the administrative burden, and urge government to implement the response it develops in collaboration with other stakeholders.

4. CONVENE AN ACTION GROUP of relevant stakeholders to facilitate sustained engagement with the issues facing LTC in Ontario. Again, there is no silver-bullet policy change that will resolve LTC’s challenges overnight. Meaningful, lasting improvement will require ongoing commitment from and dialogue among government, employers, and labour, working together to build a better LTC system in our province.

References

AdvantAge Ontario. “2019 Pre-budget Recommendations: Backgrounders.” http://www.advantageontario.ca/AAO/Content/Resources/Advantage_Ontario/2019-PB-Advocacy.aspx.

———. “The Challenge of a Generation: Meeting the Needs of Ontario’s Seniors.” 2019 Provincial Budget Submission. http://www.advantageontario.ca/AAO/Content/Resources/Advantage_Ontario/2019-PB-Advocacy-Pub.aspx.

Agha, Leila. “The Effects of Health Information Technology on the Costs and Quality of Medical Care.” Journal of Health Economics 34 (2014): 19–30. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.12.005.

Alzheimer’s Society Ontario. “What Are Responsive Behaviours.” https://alzheimer.ca/en/on/We-can-help/Resources/Shifting-Focus/What-are-responsive-behaviours.

Alzheimer’s Society. “Risk Factors for Dementia.” Factsheet 450LP. April 2016. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf/factsheet_risk_factors_for_dementia.pdf.

Banerjee, Albert, Tamara Daly, Pat Armstrong, Marta Szebehly, Hugh Armstrong, and Stirling Lafrance. “Structural Violence in Long-Term, Residential Care for Older People: Comparing Canada and Scandinavia.” Social Science & Medicine 74 (2012): 390–98. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.037.

Barken, Rachel, Margaret Denton, Firat K. Sayin, Catherine Brookman, Sharon Davies, and Isik U. Zeytinoglu. “The Influence of Autonomy on Personal Support Workers’ Job Satisfaction, Capacity to Care, and Intention to Stay.” Home Health Care Services Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2018): 294–312. DOI: 10.1080/01621424.2018.1493014.

Berta, Whitney, Audrey Laporte, Tyrone Perreira, Liane Ginsburg, Adrian Rohit Dass, Raisa Deber, Andrea Baumann, Lisa Cranley, Ivy Bourgeault, Janet Lum, Brenda Gamble, Kathryn Pilkington, Vinita Haroun, and Paula Neves. “Relationships Between Work Outcomes, Work Attitudes and Work Environments of Health Support Workers in Ontario Long-Term Care and Home and Community Care Settings.” Human Resources for Health 16, no. 15 (2018): 1–11. DOI: 10.1186/s12960-018-0277-9.

Boscart, Veronique M., Souraya Sidani, Jeffrey Ross, Meaghan Davey, Josie d’Avernas, Paul Brown, George Heckman, Jenny Ploeg, and Andrew P. Costa. “The Associations Between Staffing Hours and Quality of Care Indicators in Long-Term Care.” BMC Health Services Research 18, no. 750 (2018): 1–7. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-3552-5.

Braedley, Susan, Prince Owusu, Anna Przednowek, and Pat Armstrong. “We’re Told, ‘Suck It Up’: Long-Term Care Workers’ Psychological Health and Safety.” Ageing International 43, no. 1 (March 2018): 91–109. DOI: 10.1007/s12126-017-9288-4.

Brophy, James, Margaret Keith, and Michael Hurley. “Breaking Point: Violence Against Long-Term Care Staff.” New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy 29, no. 1 (2019): 10–35. DOI: 10.1177/1048291118824872.

Calkins, Margaret P. “Evidence-Based Design for Dementia: Findings from the Past Five Years.” Long-Term Living 60, no. 1 (2011): 42–45.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. “Definitions and Guidelines to Support ALC Designation in Acute Inpatient Care.” https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/acuteinpatientalc-definitionsandguidelines_en.pdf.

———. “National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2016.” 2016. https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/NHEX-Trends-Narrative-Report_2016_EN.pdf.

Castle, Nicholas G. “Nursing Home Caregiver Staffing Levels and Quality of Care: A Literature Review.” Journal of Applied Gerontology 27, no. 4 (2008): 375–405. DOI: 10.1177/0733464808321596.

CBC News. “Nursing Home Resident Says Support Workers ‘Being Run Off Their Feet,’ Need More Staffing.” CBC News, February 1, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/windsor/ontario-long-term-care-facility-psw-shortage-1.5003312.

CBC News. “Overloaded and Undervalued, a Crisis for Personal Support Workers.” CBC News, May 22, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/sudbury/personal-support-workers-sudbury-crisis-1.5143707.

Chamberlain, Stephanie A., Andrea Gruneir, Matthias Hoben, Janet E. Squires, Greta G. Cummings, and Carole A. Estabrooks. “Influence of Organizational Context on Nursing Home Staff Burnout: A CrossSectional Survey of Care Aides in Western Canada.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 71 (2017): 60–69. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.02.024.

Chamberlain, Stephanie A., Matthias Hoben, Janet E. Squires, and Carole A. Estabrooks. “Individual and Organizational Predictors of Health Care Aide Job Satisfaction in Long Term Care.” BMC Health Services Research 16, no. 577 (2016): 1–9. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-016-1815-6.

Chan, Zenobia C.Y., Wu San Tam, Maggie K.Y. Lung, Wing Yan Wong, and Ching Wa Chau. “A Systematic Literature Review of Nurse Shortage and the Intention to Leave.” Journal of Nursing Management 21 (2013): 605–13. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01437.x.

CLAC. “2019 Public Sector Consultations: Submission to Peter Bethlenfalvy, Treasury Board President, and Karen Hughes, Deputy Minister, Treasury Board Secretariat.” May 24, 2019. https://www.clac.ca/Your-voice/Article/ArtMID/4829/ArticleID/1051/2019-Ontario-Public-Sector-Consultations.

———. “Patients First: A Plan to Combat Pressures in Ontario’s Long Term Care System.” 2016. https://www.clac.ca/Your-voice/Article/ArtMID/4829/ArticleID/130/Patients-First-A-plan-to-combat-pressures-in-Ontario%e2%80%99s-long-term-care-system.

Dunham, Jackie. “Six Minute Challenge: Can You Get Ready as Fast as Nursing Home Residents?” CTV News, January 10, 2018. https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/six-minute-challenge-can-you-get-ready-as-fast-as-nursing-home-residents-1.3753212.

Estabrooks, Carole A., Janet E. Squires, Heather L. Carleton, Greta G. Cummings, and Peter G. Norton. “Who Is Looking After Mom and Dad? Unregulated Workers in Canadian Long-Term Care Homes.” Canadian Journal on Aging 34, no. 1 (March 2015): 47–59. muse.jhu.edu/article/567366.

Financial Accountability Office of Ontario. “Long-Term Care Homes Program: A Review of the Plan to Create 15,000 New Long-Term Care Beds in Ontario.” October 31, 2019. https://fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/ontario-long-term-care-program.

———. “Ontario Health Sector: 2019 Updated Assessment of Ontario Health Spending.” March 6, 2019. fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/health-update-2019.

Freedman, Seth, Haizhen Lin, and Jeffrey Prince. “Information Technology and Patient Health: An Expanded Analysis of Outcomes, Populations, and Mechanisms.” Social Science Research Network. Paper no. 2445431 (2014): 1–35.

Gillese, Eileen E. Public Inquiry into the Safety and Security of Residents in the Long-Term Care Homes System: Report. 4 vols. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2019. https://longtermcareinquiry.ca/en/final-report/.

Goldzweig, Caroline Lubick, Greg Orshansky, Neil M. Paige, Ali Alexander Towfigh, David A. Haggstrom, Isomi Miake-Lye, Jessica M. Beroes, and Paul G. Shekelle. “Electronic Patient Portals: Evidence on Health Outcomes, Satisfaction, Efficiency, and Attitudes: A Systematic Review.” Annals of Internal Medicine 159, no. 10 (2013): 677–87. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-20131119-00006.

Grech, Ron. “PSW Shortage Poses Crisis in Long-Term Care.” The Timmins Daily Press, April 24, 2019. https://www.timminspress.com/news/local-news/psw-shortage-poses-crisis-in-long-term-care.

Halter, Mary, Olga Boiko, Ferruccio Pelone, Carole Beighton, Ruth Harris, Julia Gale, Stephen Gourlay, and Vari Drennan. “The Determinants and Consequences of Adult Nursing Staff Turnover: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews.” BMC Health Services Research 17, no. 824 (2017): 1–20. DOI: 10.1186/ s12913-017-2707-0.

Health Quality Ontario. “Measuring Up 2018.” 2018. https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/Documents/pr/measuring-up-2018-en.pdf.

Hewko, Sarah J., Sarah L. Cooper, Hanhmi Huynh, Trish L. Spiwek, Heather L. Carleton, Shawna Reid, and Greta G. Cummings. “Invisible No More: A Scoping Review of the Health Care Aide Workforce Literature.” BMC Nursing 14, no. 38 (2015): 1–17. DOI: 10.1186/s12912-015-0090-x.

Hussein, Shereen. “‘We Don’t Do It for the Money’. . . The Scale and Reasons of Poverty-Pay Among Frontline Long-Term Care Workers in England.” Health and Social Care in the Community 25, no. 6 (November 2017): 1817–26. DOI: 10.1111/hsc.12455.

Hyer, Kathryn, Kali S. Thomas, Laurence G. Branch, Jeffrey S. Harman, Christopher E. Johnson, and Robert Weech-Maldonado. “The Influence of Nurse Staffing Levels on Quality of Care in Nursing Homes.” The Gerontologist 51, no. 5 (2011): 610–16. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnr050.

Khamisa, Natasha, Karl Peltzer, and Brian Oldenburg. “Burnout in Relation to Specific Contributing Factors and Health Outcomes among Nurses: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10, no. 6 (2013): 2214–40. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph10062214.

Knopp-Sihota, Jennifer A., Linda Niehaus, Janet E. Squires, Peter G. Norton, and Carole E. Estabrooks. “Factors Associated with Rushed and Missed Resident Care in Western Canadian Nursing Homes: A Cross-Sectional Survey of Health Care Aides.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 24 (2015): 2815–25. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.12887.

Laucius, Joanne. “‘We Are in Crisis’: Personal Support Workers Are the Backbone of Home Care in Ontario— and There Aren’t Enough of Them.” Ottawa Citizen, July 13, 2018. https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/when-the-backbone-is-broken.

Li, Yin, and Cheryl B. Jones. “A Literature Review of Nursing Turnover Costs.” Journal of Nursing Management 21 (2013): 405–18. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01411.x.

Lin, Haizhen. “Revisiting the Relationship Between Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes: An Instrumental Variables Approach.” Journal of Health Economics 37 (2014): 13–24. DOI: 10.1016/j. jhealeco.2014.04.007.

Mallidou, Anastasia A., Greta G. Cummings, Corinne Schalm, and Carole A. Estabrooks. “Health Care Aides Use of Time in A Residential Long-Term Care Unit: A Time and Motion Study.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 50 (2013): 1229–39.

McCullough, Jeffrey S., Michelle Casey, Ira Moscovice, and Shailendra Prasad. “The Effect of Health Information Technology on Quality in US Hospitals.” Health Affairs 29, no. 4 (April 2010): 647–54. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0155.

McCullough, Jeffrey S., Stephen T. Parente, and Robert Town. “Health Information Technology and Patient Outcomes: The Role of Information and Labor Coordination.” The RAND Journal of Economics 47, no. 1 (2016): 207–36. DOI: 10.1111/1756-2171.12124.

McGregor, Margaret J., and Lisa A. Ronald. “Residential Long-Term Care for Canadian Seniors: Nonprofit, For-Profit or Does It Matter?” IRPP Study 14 (January 2011): https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/study-no14.pdf.

Montague, Alan, John Burgess, and Julia Connell. “Attracting and Retaining Australia’s Aged Care Workers: Developing Policy and Organisational Responses.” Labour & Industry 25, no. 4 (2015): 293–305. DOI: 10.1080/10301763.2015.1083367.

Morgan, Jennifer Craft, Janette Dill, and Arne L. Kalleberg. “The Quality of Healthcare Jobs: Can Intrinsic Rewards Compensate for Low Extrinsic Rewards?” Work, Employment and Society 27, no. 5 (2013): 802–22. DOI: 10.1177/0950017012474707.

Muller, Jerry Z. The Tyranny of Metrics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018.

North East Local Health Integration Network. “HOME FIRST Shifts Care of Seniors to HOME.” August 22, 2011. http://www.nelhin.on.ca/~/media/sites/ne/assets/69a65c95-6177-4adc-b6f2-ccc3e47cec95/bfdd7682635c42db803e3d46b1dcb2a55.pdf.

O’Neil, Cathy. Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. Largo, MD: Crown, 2016.

OLTCA. “About Long-Term Care in Ontario: Facts and Figures.” https://www.oltca.com/oltca/OLTCA/LongTermCare/OLTCA/Public/LongTermCare/FactsFigures.aspx?hkey=f0b46620-9012-4b9b-b033-2ba6401334b4.

———. “Long-Term Care That Works. For Seniors. For Ontario. 2019 Budget Submission.” 2019. http://betterseniorscare.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/OLTCA_Budget_Submission_FINAL.pdf.

———. “More Care. Better Care. 2018 Budget Submission.” 2018. https://www.oltca.com/OLTCA/Documents/Reports/2018OLTCABudgetSubmission-MoreCareBetterCare.pdf.

———. “This Is Long-Term Care 2019.” 2019. https://www.oltca.com/OLTCA/Documents/Reports/TILTC2019web.pdf.

Ontario Health Coalition. “Situation Critical: Planning, Access, Levels of Care and Violence in Ontario’s LongTerm Care.” January 2019. http://www.ontariohealthcoalition.ca/wp-content/uploads/FINAL-LTCREPORT.pdf.

Ontario Health Coalition. “Long Term Health Care at Situation Critical.” January 21, 2019. https://www.ontariohealthcoalition.ca/index.php/long-term-health-care-at-situation-critical-baytoday-january-21-2019/.

Ontario Ministry of Finance. “Ontario Populations Projections Update, 2017–2041.” Modified June 25, 2018. https://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/economy/demographics/projections/.

Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. “Aging at Home Strategy.” August 31, 2010. https://news.ontario.ca/mohltc/en/2010/08/aging-at-home-strategy.html.

———. “Hallway Health Care: A System Under Strain—First Interim Report from the Premier’s Council on Improving Healthcare and Ending Hallway Medicine.” January 2019. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/publications/premiers_council/report.aspx#exec_summary.

Ontario Treasury Board Secretariat. “Public Accounts of Ontario: Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements 2017–2018.” Government of Ontario, 2018. https://www.ontario.ca/page/public-accounts-2017-18-annual-report.

Palangkaraya, Alfons, and Jongsay Yong. “Population Ageing and Its Implications on Aggregate Health Care Demand: Empirical Evidence from 22 OECD Countries.” International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economics 9 (2009): 391. DOI: 10.1007/s10754-009-9057-3.

Schnelle, John F., Sandra F. Simmons, Charlene Harrington, Mary Cadogan, Emily Garcia, and Barbara M. Bates‐Jensen. “Relationship of Nursing Home Staffing to Quality of Care.” Health Services Research 39, no. 2 (2004): 225–50. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-5773.2004.00225.x.

Seshamani, Meena, and Alastair Gray. “A Longitudinal Study of the Effects of Age and Time to Death on Hospital Costs.” Journal of Health Economics 23, no. 2 (March 2004): 217–35. DOI: 10.1016/j. jhealeco.2003.08.004.

Singh, Douglas A. Effective Management of Long-Term Care Facilities. 2nd ed. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2010.

Spilsbury, Karen, Catherine Hewitt, Lisa Stirk, and Clive Bowman. “The Relationship Between Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 48, no. 6 (2011): 732–50. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.014.

Squires, Janet E., Matthias Hoben, Stefanie Linklater, Heather L. Carleton, Nicole Graham, and Carole A. Estabrooks. “Job Satisfaction Among Care Aides in Residential Long-Term Care: A Systematic Review of Contributing Factors, Both Individual and Organizational.” Nursing Research and Practice (2015): 1–24. DOI: 10.1155/2015/157924.

Statistics Canada. “Age and Sex, and Type of Dwelling Data: Key Results from the 2016 Census.” May 3, 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/170503/dq170503a-eng.htm#archived.

———. “Census in Brief: A Portrait of the Population Aged 85 and Older in 2016 in Canada.” May 3, 2017. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016004/98-200-x2016004-eng.cfm.

Zeller, Adelheid, Sabine Hahn, Ian Needham, Gerjo Kok, Theo Dassen, and Ruud J.G. Halfens. “Aggressive Behavior of Nursing Home Residents Toward Caregivers: A Systematic Literature Review.” Geriatric Nursing 30, no. 3 (2009): 174–87. DOI: 10.1016/j.gernurse.2008.09.002.