Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Regulatory Framework

The provincial government sets the broad policy direction of BC’s gambling industry, but has little involvement in the day-to-day organizational affairs of the sector. Most commercial gambling activities in BC are conducted and managed by BCLC, a Crown corporation whose official mandate involves “enhancing the financial performance, integrity, efficiency, and sustainability of the gaming industry in the province.”

BCLC is subject to regulatory oversight from the Gaming Policy and Enforcement Branch (GPEB), whose responsibility it is to ensure the overall integrity of all gambling activities in BC. GPEB also licenses any gambling activities not operated by BCLC, including horse racing and charitable gambling fundraising events run by not-for-profit community organizations. Gaming service providers in the private sector—companies that contract with BCLC to do things like operate facilities, supply equipment, or sell lottery tickets—must be registered by GPEB.

Operations

Where the Money Comes From

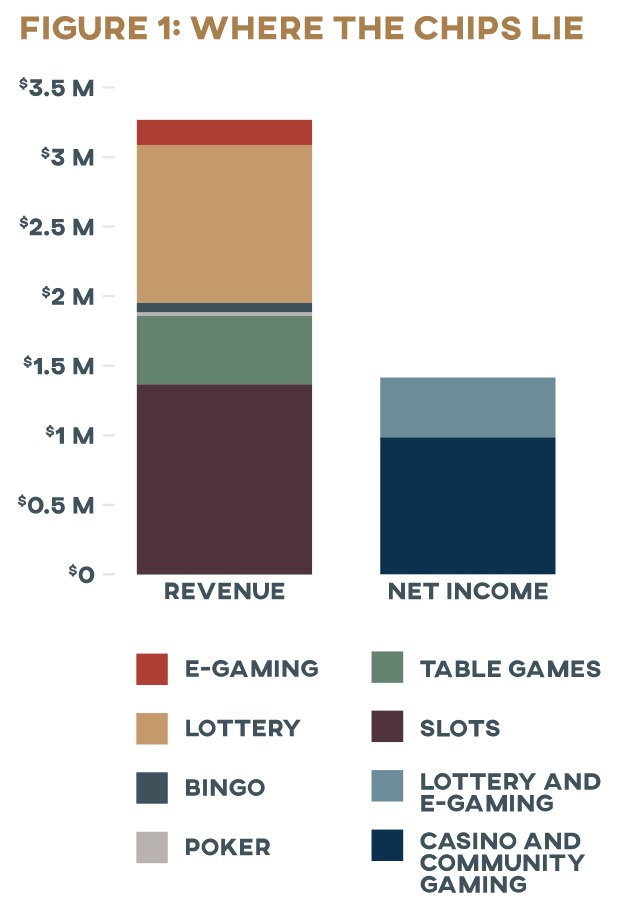

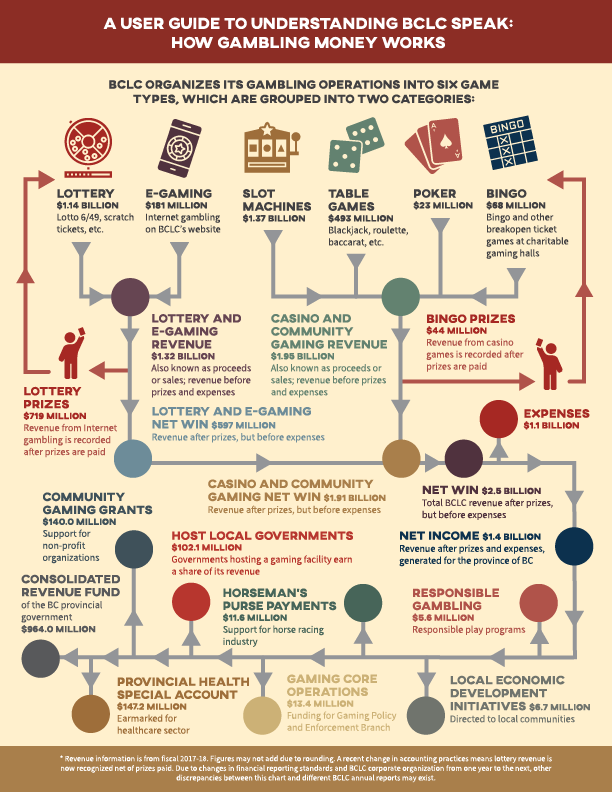

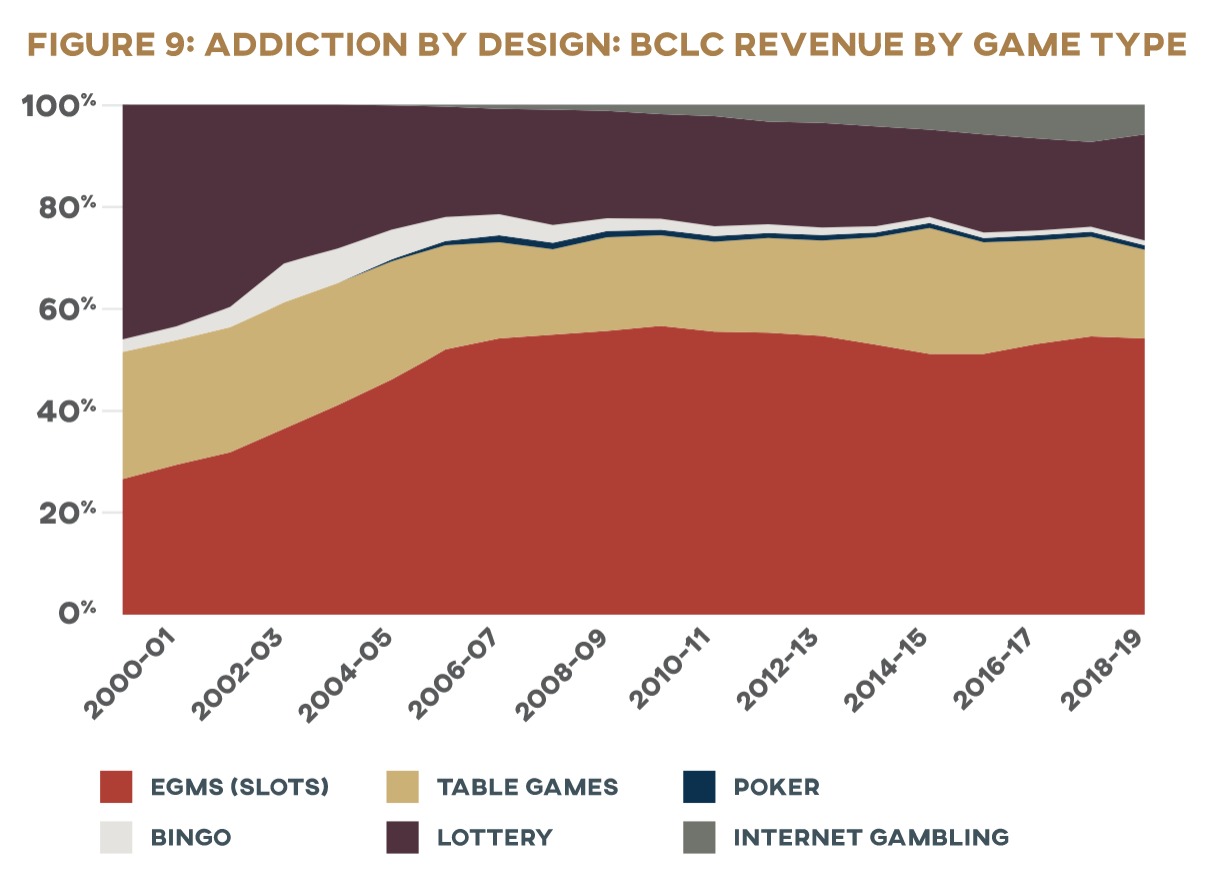

BCLC generated close to $3.3 billion in revenue over the 2017–18 fiscal year. This revenue comes from a range of different gambling operations, which are recorded under two categories: “Lottery & eGaming,” which consists of ticket lottery games and online gambling, and “Casino & Community Gaming”: slots, table games, poker, and bingo. The largest share of gambling revenue comes from the most addictive medium: slot machines (the control-inhibiting design elements of which are discussed below) bring in about 42 percent of total revenue at $1.37 billion. The other major revenue source is the lottery, which took in another 35 percent at $1.13 billion. Table games are a distant third at 15 percent of revenue ($493 billion), with the remaining 8 percent split between e-gaming ($181 million), bingo ($70 million), and poker ($22 million). BCLC’s net win—revenue after prizes have been paid to players, but before expenses—was $2.5 billion. Prize payments also shift the overall profitability of these games: lottery net win is only $416 million (17 percent), while slots account for more than half (55 percent) of net win. There is a substantial difference in the profit margins of BCLC’s two gaming categories: casino & community gaming’s net income (after prizes and expenses) was $1.02 billion (52 percent of proceeds) in 2018, while lottery and e-gaming contributed only $378 million (29 percent of proceeds) to provincial coffers (Figure 1). 1 1 BCLC, “2017/18 Annual Service Plan Report,” July 2018, https://corporate.bclc.com/content/dam/bclccorporate/reports/annual-reports/2018/2017-18-annual-service-plan-report.pdf. Due to a change in international accounting standards that came into effect in 2018, figures from fiscal 2018–19 are not directly comparable to earlier years; in order to facilitate comparability over time, 2018 figures are used.

Where the Money Goes

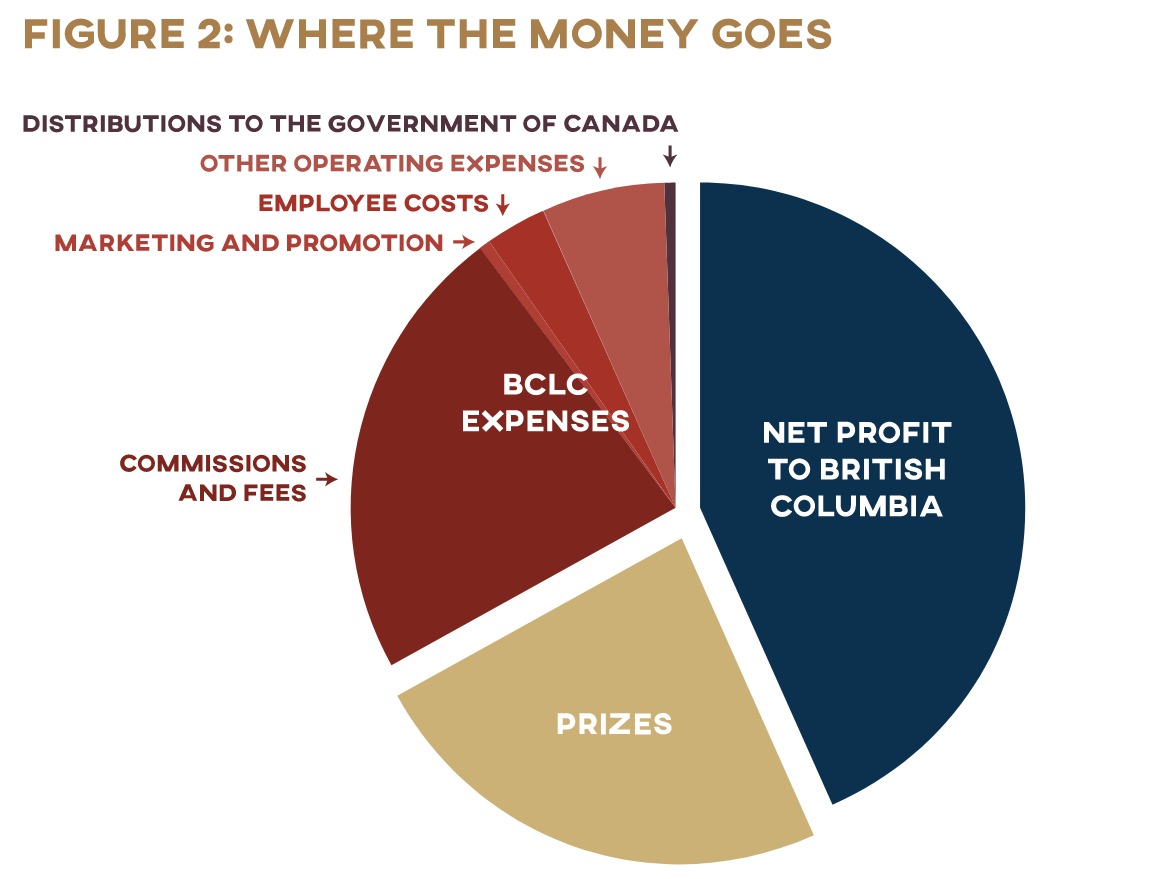

This revenue is destined for many different pots (Figure 2). BCLC’s largest expense is prizes: $764 million was paid out to winners across the province in 2017–18. Commissions and fees—many of which are paid to private-sector businesses such as lottery retailers and facility service providers—were a close second at $723 million. All other operating expenses, such as maintenance, gaming licenses, and ticket printing—totaled $319 million. In accordance with the federal-provincial gambling agreement of 1985, BCLC sends a portion of its profits to Ottawa ($9.8 million in 2018). Everything left over after all these bills have been paid—about a third of total revenue—goes to the province.

Who’s Hooked? Gambling Profits as a Proportion of Provincial Revenue

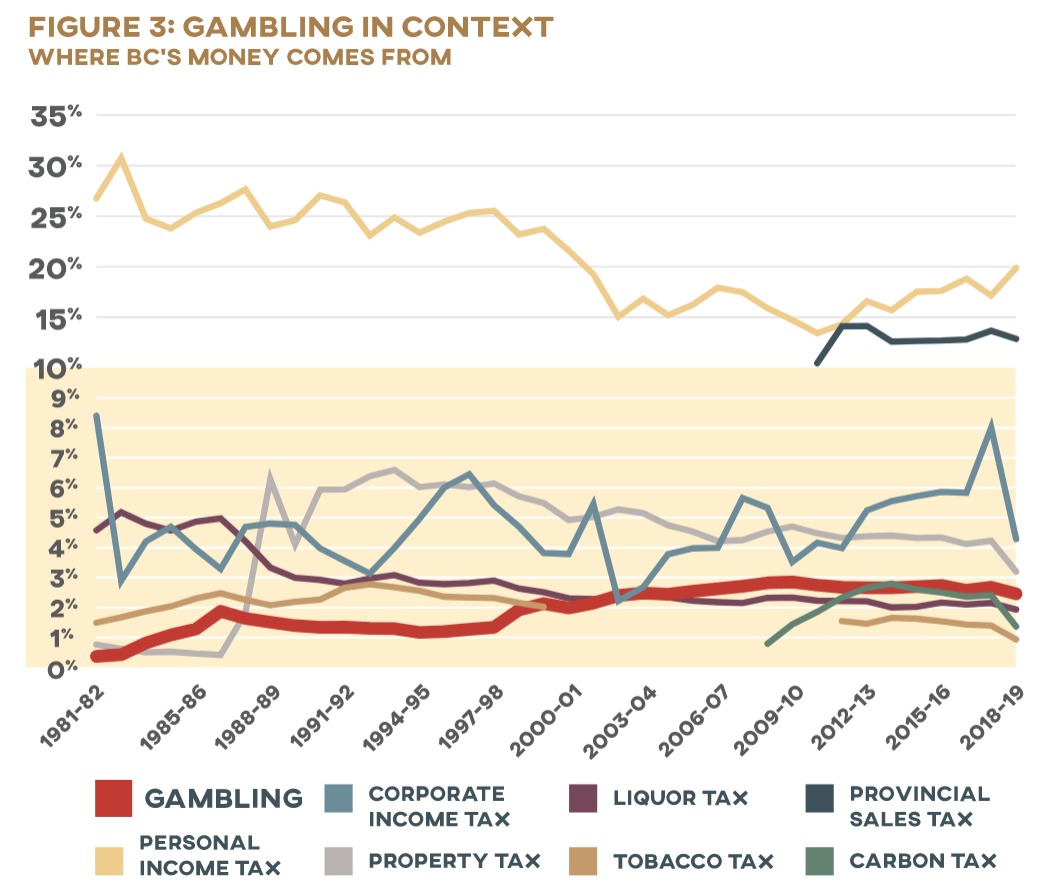

Gambling has become a lucrative source of funds since the first legal lotteries were introduced to the province in 1974. The BC government’s first gambling cheque from the Western Canada Lottery Foundation was for a mere $1.5 million; its most recent gambling cheque from BCLC came in at $1.4 billion. 2 2 BCLC, “2018/19 Annual Service Plan Report.” As the gambling industry has grown in BC, so too has the provincial government’s reliance on it as a source of revenue. Nearly 2.5 percent of public funds in BC are now collected at slot machines, casino tables, and lottery checkout lanes (Figure 3).

But where is this money coming from? Who, and what communities, are the source of these funds?

P(l)ayer Profile: Gambling Demographics

Most of British Columbia’s population is paying into the pockets of BCLC in one form or another. Survey data indicates that around two-thirds to three-quarters of British Columbians (63–73 percent 3 3 Katherine Marshall, “Gambling 2011,” Statistics Canada, Perspectives on Labour and Income (Winter 2011): 6, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-001-x/2011004/article/11551-eng.htm; BC Ministry of Finance, “2014 British Columbia Problem Gambling Prevalence Study,” October 2014, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/sports-recreation-arts-and-culture/gambling/gambling-in-bc/reports/rpt-rg-prevalence-study-2014.pdf; British Columbia Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, “British Columbia Problem Gambling Prevalence Study,” January 25, 2008, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/sports-recreation-arts-and-culture/gambling/gambling-in-bc/reports/rpt-rg-prevalence-study-2008.pdf. )gamble in a given year. This is roughly consistent with estimates of the Canada-wide average (which hover around 67–81 percent 4 4 Marshall, “Gambling 2011,” 6; John McCready et al., “Gambling and Seniors: Sociodemographic and Mental Health Factors Associated with Problem Gambling in Older Adults in Canada,” report on research award for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre, April 2010, 57, https://www.greo.ca/Modules/EvidenceCentre/Details/gambling-and-seniors-sociodemographic-and-mental-health-factors-associated-problem-gamblin-1; Martha MacDonald, John L. McMullan, and David C. Perrier, “Gambling Households in Canada,” Journal of Gambling Studies 20, no. 3 (Fall 2004): 194. ).

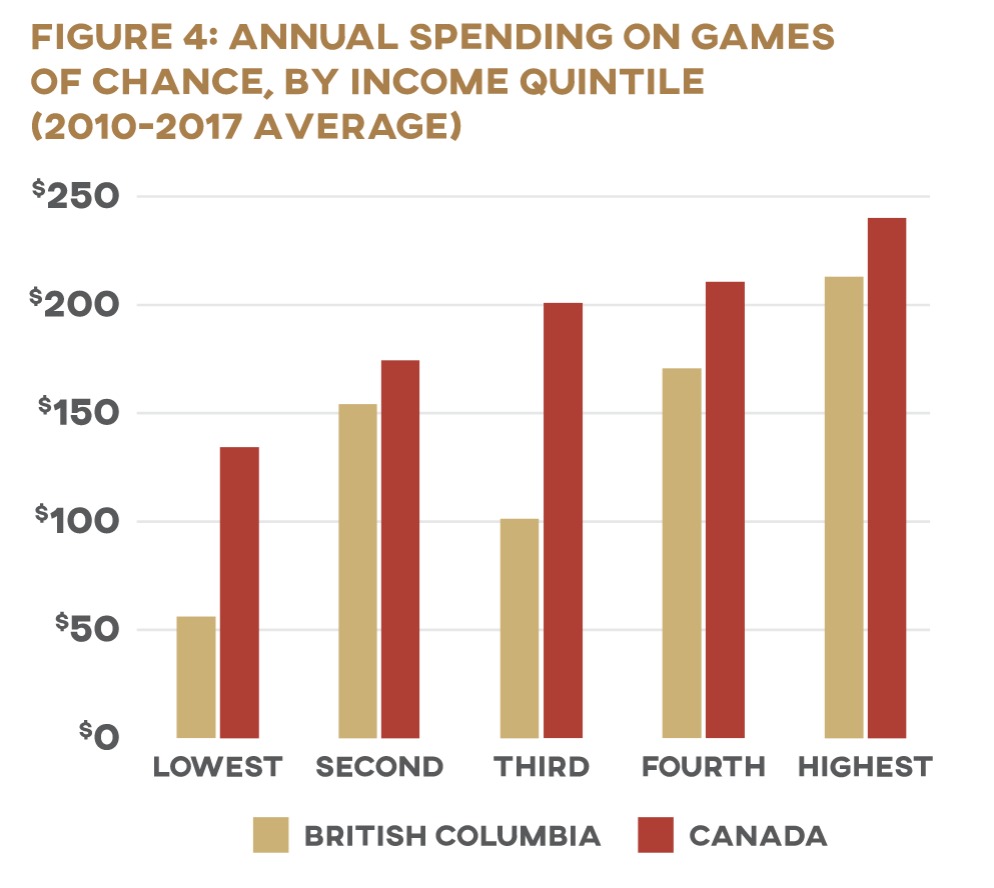

Money In, Money Out: Gambling Spending by Income

BC’s population is not, however, paying BCLC equally. The regressive nature of gambling revenue is hard to see on the surface. The data collected by Statistics Canada’s Survey of Household Spending (SHS) seem to show that those who have more money are more likely to gamble and to spend more money when they do: the average household in Canada’s highest income quintile spent $240 on gambling each year, while the average lowest-quintile household spent a mere $134. 5 5 Author’s calculations based on data from Statistics Canada, “Table 11-10-0223-01: Household Spending by Household Income Quintile, Canada, Regions and Provinces,” https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110022301. Limited data were available at the provincial level, so national-level data are used. While very limited data are available for BC, a similar pattern emerges: highest-quintile households report spending $213, while those in the lowest quintile report spending only $56 (Figure 4). 6 6 Since only one data point was available for lowest-quintile households in BC, this figure should be treated with caution.

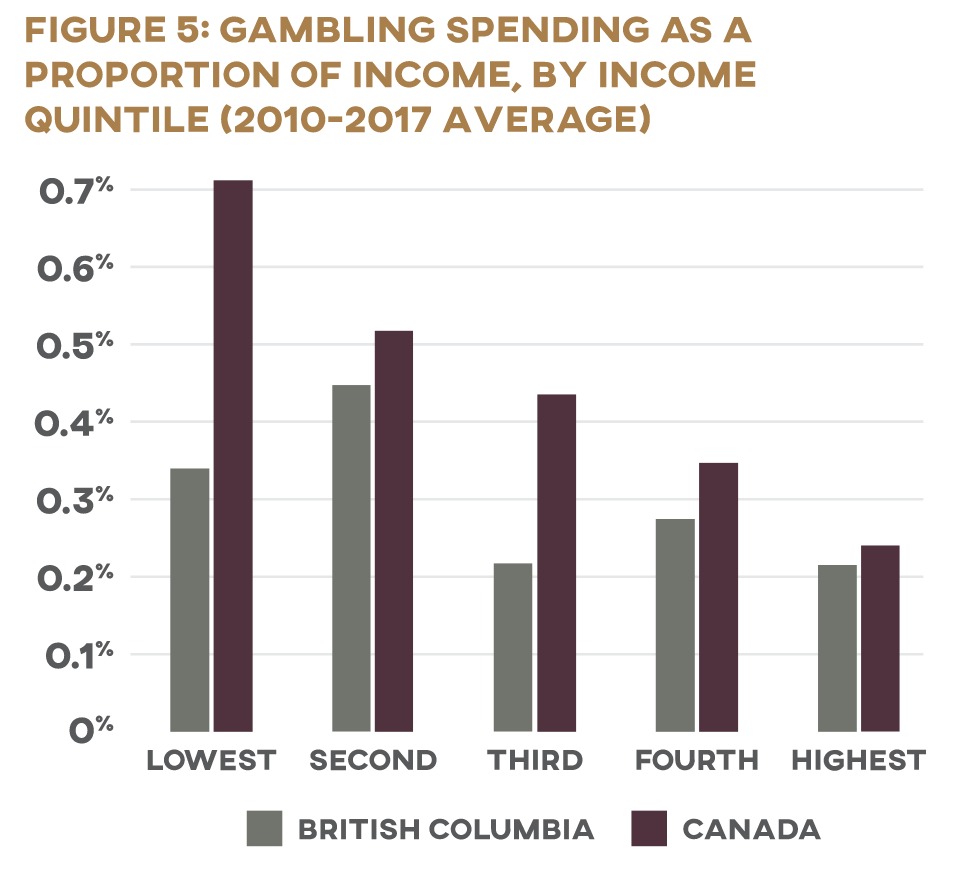

But first glances can be deceptive. Higher earners may be spending more of their paycheques at the casino, but gambling eats up a much higher proportion of the poor’s income (Figure 5). According to SHS data from 2010–17, households in Canada’s highest-income quintile spend an average of 0.24 percent of their after-tax earnings on games of chance each year; those in the lowest quintile spent nearly three times as much, at 0.71 percent. BC’s poorest households spent more than half again as much of their income on gambling as did the richest (0.34 percent compared to 0.22 percent according to available data). 7 7 All figures are author’s calculations based on data from Statistics Canada’s Canada Income Survey and Survey of Household Spending. See appendix 1 for details. Statistics Canada, “Household Spending”; User Guide to the Survey of Household Spending, 2015 (Ottawa: Income Statistics Division, 2017), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/62F0026M2017001; Statistics Canada, “Table 11-10-0193-01: Upper Income Limit, Income Share and Average of Adjusted Market, Total and After-Tax Income by Income Decile,” https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1110019301.

Less than 1 percent of a household’s annual earnings may not seem like a lot of money, even for a low-income family. These seemingly low numbers, however, should not distract us from the high-stakes problem at play: when BC collects lottery and casino money, it is digging deeper into the pockets of the poor than the rich. Gambling may be a “voluntary” tax (more on the accuracy of this description below as well), but it’s a tax the BC government is reliant on nonetheless—which means the province is paying its bills in a way that hits low-income families hardest.

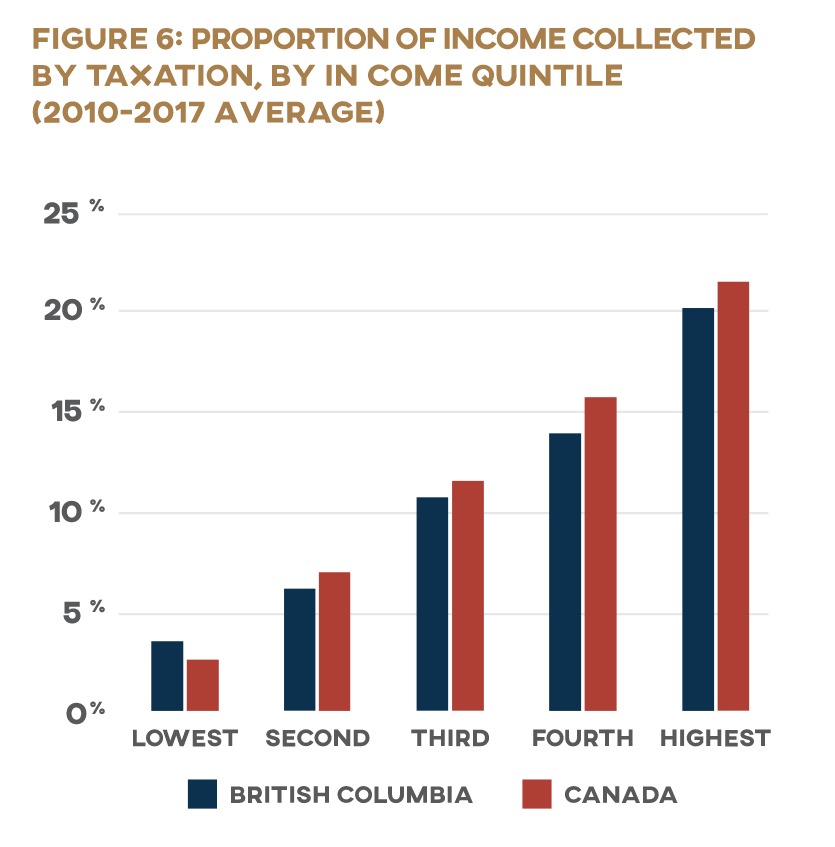

The regressive nature of gambling taxes is no secret: research both within Canada and internationally has consistently found that poor households spend a greater percentage of their income on gambling than their wealthier neighbours do. 8 8 See, e.g., MacDonald, McMullan, and Perrier, “Gambling Households in Canada”; Jon D. Wisman, “State Lotteries: Using State Power to Fleece the Poor,” Journal of Economic Issues (Association for Evolutionary Economics) 40, no. 4 (December 2006): 955–66; Jim Orford et al., “The Role of Social Factors in Gambling: Evidence from the 2007 British Gambling Prevalence Survey,” Community, Work & Family 13, no. 3 (August 2010): 258; Thijs Bol, Bram Lancee, and Sander Steijn, “Income Inequality and Gambling: A Panel Study in the United States (1980–1997),” Sociological Spectrum 34, no. 1 (January 2014): 64; K. Brandon Lang and Megumi Omori, “Can Demographic Variables Predict Lottery and Pari-Mutuel Losses? An Empirical Investigation,” Journal of Gambling Studies 25, no. 2 (June 2009): 173; Sari Castrén et al., “The Relationship Between Gambling Expenditure, Sociodemographics, Health-Related Correlates and Gambling Behavior—A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Survey in Finland,” Addiction 113, no. 1 (2018): 91–92. And yet this is exactly the opposite of how other tax revenue functions. Our progressive tax system is designed to tax the rich more heavily than the poor: those who have more pay more. The lowest-income quintile in BC loses barely 3.5 percent of its total income to federal and provincial income tax, while the average household in the province’s highest-income quintile turns over to the government nearly six times more of its total income, at 20 percent. (Figure 6) 9 9 Author’s calculations based on data from Statistics Canada, “Upper Income Limit.”

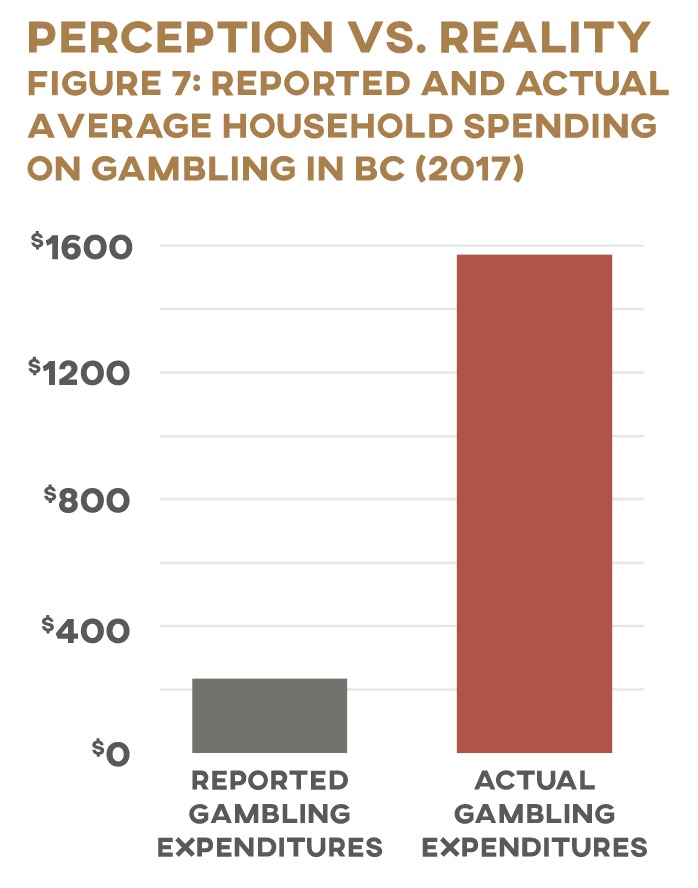

The Demographics Data Gap

Statistics Canada’s data on spending and income across the country provide a window into the relationship between gambling and household earnings. But these figures are not without their limitations. As with other addictions, most of us don’t want to admit we have a problem—but we’re gambling more than we think. According to the SHS, the average BC household spent $234 on games of chance in 2017. Multiply this figure by the number of households in BC that year (2.0 million 10 10 Statistics Canada, “Table 36-10-0101-01: Distributions of Household Economic Accounts, Number of Households, by Income Quintile and by Socio-demographic Characteristic,” https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=3610010101#timeframe. ), though, and the provincial population’s total gambling spending comes to only $476 million—a mere 15 percent of BCLC’s recorded revenue that year ($3.2 billion 11 11 BCLC, “2016/17 Annual Service Plan Report,” https://www.bcbudget.gov.bc.ca/Annual_Reports/2016_2017/pdf/agency/bclc.pdf. Figures adjusted for inflation. ). Put another way, the average BC household would have to have gambled close to $1,600 in 2017 for BCLC’s books to balance. And yet the match between self-reported and actual revenue in 2017 was better than usual: the average match between BCLC earnings and SHS expenditure data was only 10.5 percent from 2010 to 2016. This inconsistency is not uncommon: people typically underestimate how much they actually spent gambling in self-reported household expenditure surveys, often dramatically (Figure 7). 12 12 Robert T. Wood and Robert J. Williams, “‘How Much Money Do You Spend on Gambling?’ The Comparative Validity of Question Wordings Used to Assess Gambling Expenditure,” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10, no. 1 (2007): 63–77.

Cause for Concern

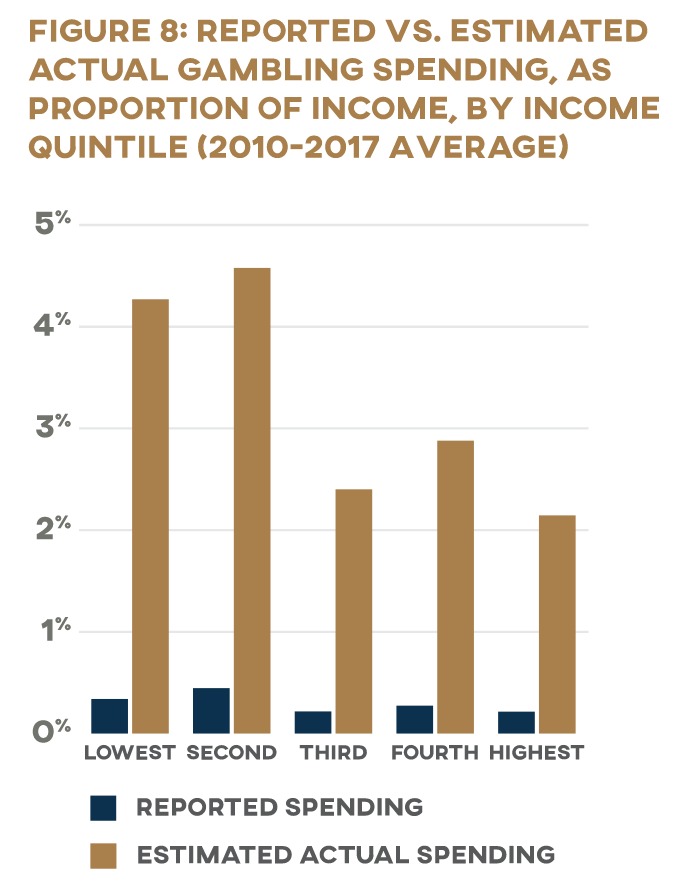

Though SHS data must be interpreted with caution, the core issue at hand remains: gambling disproportionately burdens the poor, a finding that is not only consistent across provinces in SHS data but has been repeatedly borne out by other research as well. If households across all income quintiles underestimate their gambling spending by approximately the same margin in their SHS expenditure records, it would mean BC’s lowest-income households are spending nearly 5 percent of their income—about $800 a year—on government-sponsored gambling. 13 13 Author’s calculations based on BCLC Annual Reports and Statistics Canada, “Household Spending.” For detailed calculation methodology, see Turning Bad Habits into Good. The BC government uses income taxes—which are set through a transparent process and for which it is held publicly accountable— to collect an average of $2,022 per month from households making $10,310 and only $55 from households making $1,557 a month. At the same time, and away from the gaze of the public eye, it takes another $67 of what remains in the poorest British Columbians’ pockets—an average of $1,502 for the month—but just $124 more ($191) from those who have $8,288 of their paycheques left to pay their monthly bills (Figure 8).

There’s strong evidence that those at the margins of society are paying disproportionately into the coffers of BCLC. Take, for example Canadian and international studies that establish links between lower levels of education and higher levels of gambling participation. 14 14 See, e.g., Mohamed Abdel-Ghany and Deanna L. Sharpe, “Lottery Expenditures in Canada: Regional Analysis of Probability of Purchase, Amount of Purchase, and Incidence,” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 30, no. 1 (Sept. 2001): 64–78; MacDonald, McMullan, and Perrier, “Gambling Households in Canada”; S. Castrén et al., “The Relationship Between Gambling Expenditure, Socio-demographics, Health-Related Correlates and Gambling Behaviour: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Survey in Finland: Gambling Expenditure in Relation to Net Income.” Addiction 113, no. 1 (2018): 91–106; Andrew Tan, Steven Yen, and Rodolfo Nayga Jr., “Socio-demographic Determinants of Gambling Participation and Expenditures: Evidence from Malaysia,” International Journal of Consumer Studies 34 (2010): 316–25; Tanya Davidson et al., Gambling Expenditure in the ACT (2014): By Level of Problem Gambling, Type of Activity, and Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics (Canberra: Australian National University, 2016), 11, https://www.gamblingandracing.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/982774/2014-Gambling-Expenditure.pdf; Jens Beckert and Mark Lutter, “The Inequality of Fair Play: Lottery Gambling and Social Stratification in Germany,” European Sociological Review 25, no. 4 (August 2009):475–88. Given that lower levels of education are also linked to lower earnings, 15 15 Sean Speer, “Forgotten People and Forgotten Places: Canada’s Economic Performance in the Age of Populism,” Macdonald-Laurier Institute, August 2019, https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/files/pdf/MLI_Speer_ScopingSeries1_FWeb.pdf. the overrepresentation of less-educated groups in the lottery market is likely to amplify the lottery’s regressive effect. Indigenous peoples also have disproportionately lower incomes compared to majority populations and as such are disproportionately affected by the expansion of gambling. 16 16 An in-depth review of the literature on gambling among indigenous communities is beyond the scope of this paper, but readers are encouraged to explore the substantial body of research on this topic. See, e.g., Helen Breen and Sally Gainsbury, “Aboriginal Gambling and Problem Gambling: A Review,” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 11 (2013): 75–96; D. Wardman, Nady El-Guebaly, and David Hodgins, “Problem and Pathological Gambling in North American Aboriginal Populations: A Review of the Empirical Literature,” Journal of Gambling Studies 17, no. 2 (2001): 81–100; Robert J. Williams, Rhys M.G. Stevens, and Gary Nixon, “Gambling and Problem Gambling in North American Indigenous Peoples,” in First Nations Gaming in Canada, ed. Yale Belanger (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2011), 166–94; New Zealand Ministry of Health, “Gambling and Problem Gambling: Results of the 2011/12 New Zealand Health Survey,” 2015, https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/gambling-and-problem-gambling-results-2011-12-new-zealand-health-survey; Lorna Dyall, “Gambling: A Poison Chalice for Indigenous Peoples,” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 8 (2010): 205–13; R.J. Williams and R.T. Wood, “The Demographic Sources of Ontario Gaming Revenue,” report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre, 2004. http://nodowntowncasino.ca/sites/default/files/Demographic%20Sources%20of%20Casino%20Revenue%202004.pdf; Matthew Stevens and Martin Young, “Betting on the Evidence: Reported Gambling Problems Among the Indigenous Population of the Northern Territory,” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 33, no. 6 (December 2009): 556–65; Cheryl Currie et al., “Racial Discrimination, Post Traumatic Stress, and Gambling Problems Among Urban Aboriginal Adults in Canada,” Journal of Gambling Studies 29, no. 3 (2013): 393–415; Williams

Research also suggests that British Columbia’s gambling addiction is being fed disproportionately by gambling addicts. Those classified as problem gamblers make up an estimated 2–3 percent of BC’s total adult population, depending on how problem gambling is defined and measured in a given survey.

17

17

For a collected summary of provincial gambling prevalence studies conducted in Canada, see Alberta Gambling Research

Institute, “Prevalence—Canada Provincial Studies,” last modified June 17, 2016, https://abgamblinginstitute.ca/resources/reference-sources/prevalence-canada-provincial-studies.

As with other addictions, there is an abundance of evidence suggesting that problem gambling is more likely to afflict society’s vulnerable and marginalized, having been linked to lower income, minority ethnic status, less formal education, alcohol abuse, and higher rates of psychiatric disorders.

18

18

For a concise overview of this research, see Rachel Volberg, Lauren McNamara, and Kari Carris, “Risk Factors for Problem Gambling

in California: Demographics, Comorbidities and Gambling Participation,” Journal of Gambling Studies 34 (2018): 360–63; see also Felicity K. Lorains, Sean Cowlishaw, and Shane A. Thomas, “Prevalence of Comorbid Disorders in Problem and Pathological Gambling: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Population Surveys,” Addiction 106 (2011): 490–98; Robert Williams, Rachel Volberg, and Rhys Stevens, “The Population Prevalence of Problem Gambling: Methodological Influences, Standardized Rates, Jurisdictional Differences, and Worldwide Trends,” report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, February 2012, https://opus.uleth.ca/handle/10133/4838.

Even after controlling for the effect of these mental-health risk factors, problem gamblers are more likely than the rest of the population to have attempted or thought about committing suicide.

19

19

Heather Wardle et al., “Problem Gambling and Suicidal Thoughts, Suicide Attempts and Non-suicidal Self-Harm in England: Evidence

from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007,” research report for the Gambling Commission, Birmingham, UK, 2019, https://www.gamblingcommission.gov.uk/PDF/Report-1-Problem-gambling-and-suicidal-thoughts-suicide-attempts-and-nonsuicidal-self-harm-in-England-evidence-from-the-Adult-Psychiatric-Morbidity-Survey-2007.pdf.

If half of the province’s gambling tax is collected by machines designed to override players’ conscious control, can this tax really be called “voluntary”?

One of the most consistent correlates of problem gambling is game type: those who report gambling on electronic gambling machines (EGMs, usually known as slot machines when found inside casinos and video lottery terminals, or VLTs, when found in other venues like pubs and bars) have a much higher risk of problem gambling than gamblers who report never playing EGMs. 20 20 https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/sports-recreation-arts-and-culture/gambling/gambling-in-bc/reports/rpt-rg-prevalence-study-2014.pdf, R.J. Williams, Y.D. Belanger, and J.N. Arthur, “Gambling in Alberta: History, Current Status, and Socioeconomic Impacts,” final report to the Alberta Gaming Research Institute, Edmonton, Alberta, April 2, 2011, 105, https://prism.ucalgary.ca/handle/1880/48495. These machines have faced particular scrutiny for their addictive design. 21 21 Natasha Dow Schüll, Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), discussed in Matthew Crawford, “Autism as a Design Principle: Gambling,” in The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 89–112. EGMs have provocatively been described by some researchers as “the crack cocaine of gambling” (Nicki Dowling, David Smith, and Trang Thomas, “Electronic Gaming Machines: Are They the ‘Crack-Cocaine’ of Gambling?,” Addiction 100 [2005]: 33–45), though Dowling et al. conclude that despite the consistent association between EGMs and “the highest level of problem gambling” in the literature, the empirical evidence available at time of writing was insufficient to definitively “establish the absolute ‘addictive’ potential of EGMs” (42). See also Vance Victor MacLaren, “Video Lottery Is the Most Harmful Form of Gambling in Canada,” Journal of Gambling Studies 32, no. 2 (June 2016): 459–85; Gambling Research Exchange Ontario, “Slots and VLTs,” https://www.greo.ca/en/topics/slots-and-vlts.aspx; Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, “About Slot Machines,” https://www.problemgambling.ca/gambling-help/gambling-information/about-slot-machines.aspx; John Rosengren, “How Casinos Enable Gambling Addicts,” The Atlantic, December 2016, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/12/losing-it-all/505814/. EGMS are built with features that impair players’ rational control, such as losses disguised as wins—where audio and visual effects celebrate a player “winning” an amount less than he or she wagered, even though the player lost money—and near misses, where the display of symbols makes it appear that the player was close to winning even though the outcome of each play is completely random. These structural characteristics manipulate players’ emotional and cognitive perceptions of the game to keep them playing longer and spending more. 22 22 Charles Livingstone, “How Electronic Gambling Machines Work,” 2, https://aifs.gov.au/agrc/sites/default/files/publication-documents/1706_argc_dp8_how_electronic_gambling_machines_work.pdf; see also K.A. Harrigan et al., “Research Briefing Note: Summary of the Effect and Regulation of Electronic Gaming Machine Near Misses and Losses Disguised As Wins (LDWs) on Players,” Gambling Research Exchange, April 29, 2016, https://www.greo.ca/Modules/EvidenceCentre/Details/research-briefing-note-summary-effect-and-regulation-electronic-gaming-machine-near-misses; Harrigan, “Gap Analysis: Structural Characteristics of EGMs as Indirect Risk Factors for Problem Gambling Versus the Gaming Regulations,” Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre, 2007, https://www.greo.ca/Modules/EvidenceCentre/files/Harrigan%20(2007)Gap_analysis_Structural_char; C. Jensen et al., “Misinterpreting ‘Winning’ in Multiline Slot Machine Games,” International Gambling Studies 13, no 1 (2012): 112–26, DOI:10.1080/14459795.2012.717635. Even though VLTs are illegal in BC, the province still generates just over half (51 percent) of its gambling revenue from EGMs (slot machines) in casinos and community gaming centres (Figure 8). If half of the province’s gambling tax is collected by machines designed to override players’ conscious control, can this tax really be called “voluntary”?

Gaming Out a Government Gambling Policy

BC’s government is addicted to gambling. BCLC money is treated exactly the same way as general tax revenue—even though this “voluntary tax” is not collected equitably, as the data show. Through the gambling industry, the state is digging deeper into the pockets of those who have the least so that it can keep public programs and services artificially cheap for everyone in the province. How, then, can the government be weaned off this unhealthy and unjust dependency?

Getting Clean: Cold Turkey

We suggest the massive economic upheaval created by the COVID-19 pandemic and its containment measures represents a unique opportunity for the provincial government to cut its addiction to gambling money cold turkey. At time of writing, the total cost of the outbreak on BC’s finances is impossible to predict, but the $1.4 billion BC stands to lose in gambling income is certain to pale in comparison. The province’s finances will need to be rebuilt after the COVID-19 crisis subsides, and this rebuilding project should include structures preventing the government from depending on BCLC profits to pay its bills. Social-distancing measures have already cut off the province’s flow of gambling money: BCLC facilities have been shut down the same as most others, and the amount of revenue going into public coffers from gambling is likely to be at historic lows. 23 23 Kendra Mangione, “All Casinos in B.C. Are Being Shut Down Due to Novel Coronavirus: BCLC,” CTV News, March 16, 2020, https://bc.ctvnews.ca/all-casinos-in-b-c-are-being-shut-down-due-to-novel-coronavirus-bclc-1.4855219. COVID-19 provides the province with an unprecedented opportunity for it to start clean. The costs to the treasury will never be lower. Moving gambling revenue out of the consolidated fund, and into a specific fund—preferably aimed at relief of poverty—would be the equivalent of the government admitting it has a problem, admitting that it has harmed the public it is intended to protect, and forming the first steps to making direct amends. 24 24 Gamblers Anonymous, “Recovery Program,” http://www.gamblersanonymous.org/ga/content/recovery-program.

Habit Forming

Once BCLC funds have been disentangled from legitimate tax revenue, then, how could they be used to advance the state’s responsibility to administer justice for the most vulnerable? One approach is to redistribute gambling money back to the poor directly. A second strategy is using BCLC profits to incentivize saving in accounts geared toward financially fragile households. The economic fallout of the COVID-19 outbreak, involving sudden layoffs on an unprecedented scale, has drawn attention to the importance of assets like emergency savings to cover an unexpected loss of income.

25

25

Many Canadians are asset-poor, making them particularly vulnerable to the loss of income accompanying an unexpected layoff. See Jennifer Robson, “Assets in the New Government of Canada Poverty Dashboard: Measurement Issues and Policy Implications,” presentation to the Canadian Economics Association, May 31, 2019, https://www.dropbox.com/s/4ty0pqay5vkuq7j/Presentation_Robson_CEA2019.pdf?dl=0; Compass Working Capital, “Why Asset Poverty Matters,” https://www.compassworkingcapital.

org/why-asset-poverty-matters; McGill Newsroom, “Half of Canadians Don’t Have Enough Savings,” May 11, 2015, https://www.mcgill.ca/newsroom/channels/news/half-canadians-dont-have-enough-savings-250447.

Yet close to half of Canadians do not have enough assets to cover their living expenses for three months.

26

26

David Rothwell and Jennifer Robson, “The Prevalence and Composition of Asset Poverty in Canada: 1999, 2005, and 2012,” International Journal of Social Welfare 27, no. 1 (January 2018): 17–27; https://www.mcgill.ca/newsroom/channels/news/half-canadians-dont-have-enough-savings-250447; Erica Alini, “Coronavirus: Nearly 1 Million Canadians Applied for EI Last Week,” Global News, March 24, 2020, https://globalnews.ca/news/6726111/coronavirus-ei-claims-1-million/.

Why not channel British Columbians’ desire for the excitement of chance toward activities that help them build up an emergency fund? Prize-linked savings (PLS) products, in which account holders forgo some or all of the interest they would normally earn on their savings in exchange for the chance to win a prize, have met with notable success in other jurisdictions, from Britain’s national lottery bonds to the “Save to Win” program offered by credit unions across the United States.

27

27

National Savings and Investments, “Premium Bonds,” https://www.nsandi.com/premium-bonds-25?ccd=NQBPAC; Save to Win, “History of Save to Win,” http://www.savetowin.org/product-info/history-of-save-to-win; Michigan Credit Union League, “Save to Win Celebrates 10 Years, $50 Million Saved in First Half of 2019,” July 23, 2019, https://www.mcul.org/News?article_id=29123.

Making Sure the Right House Wins

One of the responsibilities of government is to enable and encourage good habits, including economic ones, and to shape structures that promote the economic well-being of its citizens. It is important to remember that the saturation of our society with gambling both fosters in its inhabitants a distinct set of habits, attitudes, and dispositions that have social and economic consequences. Gambling is not the way to financial security, neither for individuals nor for the province.

28

28

Lucy Dadayan, “State Revenues from Gambling: Short-Term Relief, Long-Term Disappointment,” The Nelson A. Rockefeller

Institute of Government, April 2016, https://rockinst.org/issue-area/state-revenues-gambling-short-term-relief-long-term-disappointment/.

Contrary to what lottery ads would have us believe, people shouldn’t hope to get something for nothing—nor should the state encourage this insidious get-rich-quick impulse. When the state does its part to advance a positive vision of economic life, it nurtures in its citizens virtues that benefit not just pocketbooks (both private and public) but society as a whole.

29

29

Deirdre N. McCloskey, “Bourgeois Virtues?,” Cato Policy Report, May 18, 2006, https://www.deirdremccloskey.com/articles/bv/cato.php.

It’s time for government to fulfill its responsibility to turn bad habits into good.