The phrase “hewers of wood and drawers water” used to be bad. From its original use in the King James Bible to today, the term stood for a lifetime of economic bondage. It stood for workers subject to the whims of those who are free, whether imperial overlords or the capitalists who buy materials cheap, manufacture, and then sell them back at a premium.

But not everyone sees it that way. For some, hewing wood, and drawing water, along with oil, chromite, gold, copper, diamonds, natural gas, and potash is more like a land flowing with milk and honey than indentured servitude. As Russ Kuykendall noted in a recent Cardus Policy in Public, “Canada’s energy endowment brings new meaning to the expression ‘an embarrassment of riches.'” And, as one commentator noted, those riches have contributed not only to increased corporate profits, but also to significant wage increases across the country.

Much of the media discussion has focussed on the Alberta oil sands and its impact on the environment, the Canadian dollar, manufacturing, and jobs. Yet the Canadian economy is changing in ways that are not easily seen from the daily news cycle. Four observations in particular stand out, each of which presents significant challenges and opportunities for Canada’s economic and social infrastructure.

- Canada’s resource economy is not contained in Alberta. It is diverse, and well established in all regions.

- Canada’s construction sector employment growth correlates positively with losses in manufacturing sector employment.

- Canada’s infrastructure is old, and in dire need of repair.

- Construction’s importance for the Canadian economy will grow, not shrink, over the next decade. It will be a lynchpin for economic growth for the foreseeable future.

Resource Rich from Sea to Sea

Canadian media focuses on the Alberta oil sands for a good reason. The oil sands account for billions of dollars worth of investment every year, and will continue to draw high levels of investment for the next decade. The Canadian Energy Resource Institute reports that initial capital requirements alone for oil sands development hover at 10 billion dollars for 2012, rising to over 20 billion over the next 5 years. Sustaining those projects will also require billions of dollars for the next three decades. These numbers suggest that Alberta oil sands development is central to Canadian economic development.

The scope of Alberta’s resource sector has led some to suggest that we can expect regional divides between provinces that have resources, and those that do not. Lawrence Martin, for instance, suggests that Canada is “an industrial nation divided against itself.” He notes that “the increasing lopsidedness of the economy, the trending toward a raw resources mecca that hurls some provinces forward and others back needs address and redress.”

But Alberta is not the only beneficiary of Canada’s resource economy. Reed Construction Data’s Canadian Construction Overview shows construction work on major resource-based projects across the country. Seven of Canada’s twelve provinces and territories have multi-billion dollar projects in hand, and many more projects planned. A glance at upcoming or current construction projects outside of Alberta shows a wide range of projects. From a 3.3 billion dollar modernization of an aluminum smelter in B.C. to a 3.7 billion dollar iron ore mine in Aupaluk, Quebec, to the Hebron site in Newfoundland, resource-driven construction is present in almost every province.

Not all provinces are represented, of course. Atlantic Canada remains an outlier. A recent report notes that construction activity, as well as a number of other indicators, is waning in Maritime provinces outside of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Yet, with that notable exception, natural resources and economic activity spurred by their extraction can be found in all corners of our country. In short, rather than being lopsided, Canada is a country rich in a variety of resources from sea to sea.

Rise in Construction Projects, Rise in Construction Jobs

The decline in employment in the Canadian manufacturing sector is well documented. The Canadian numbers reflect a larger global trend in which global employment in manufacturing also declined. A recent McKinsey & Company study notes that “manufacturing’s share of employment will remain under pressure as a result of ongoing productivity improvements, faster growth in services, and the force of global competition, which pushes advanced economies to specialize in activities requiring more skill.”

“Faster growth in services” and “activities requiring more skill” is often understood in terms of an increase in service jobs which cannot be outsourced, along with an increase in high-tech or professional jobs. The typical picture is a divergence between low-skilled, low-paid workers who are still required because their jobs cannot be outsourced on one hand and highly skilled and highly-paid professionals on the other.

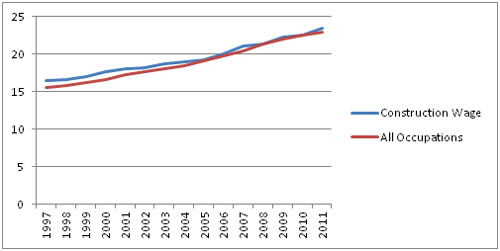

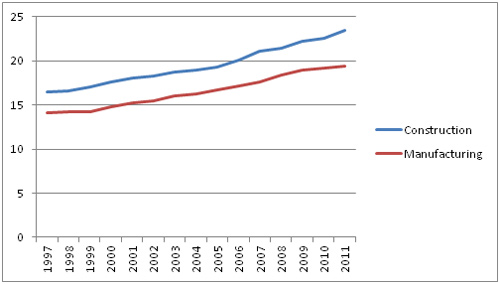

However, less attention is paid to employment in construction, which stands at the crossroads of these two trends. Construction employment cannot, by its nature, be outsourced. While modular construction is a developing trend in the industry, the bulk of construction work must be conducted by workers close to the site of the project. And, while construction wages tend to track almost exactly with the average wage rates for all Canadian occupations, Stats Canada indicates that construction wages track above the average wage of those in manufacturing. 1 1 Stats Canada. Table 282-0069: Labour force survey estimates (LFS), wages of employees by type of work, National Occupational Classification for Statistics (NOC-S), sex and age group, unadjusted for seasonality. http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&retrLang=eng&id=2820069&paSer=&pattern=&stByVal=1&p1=1&p2=37&tabMode=dataTable&csid= Accessed 26/11/12.

These trends are notable because Reed’s data indicates that the loss of manufacturing jobs is mirrored by the increase in construction employment. While manufacturing employment has declined from just over 2.2 million to just over 600,000 in the decade between 2002 and 2012, construction employment has risen from approximately 800,000 to just below 1.3 million in the same time period. And, given the scope of work needed in the resource sector over the next decade, that number is likely to go up. There is also another reason to pay attention to construction as a key driver of employment: aging infrastructure.

Canada's Infrastructure Passes Middle Age

Canada’s infrastructure, like the baby boom generation that built much of it, is getting old. Stories of concrete falling off of bridges or bursting water pipes are so common that we barely notice them in the news. But the reality is that most of Canada’s infrastructure – a necessity for economic and social well-being- is past the middle of its lifespan. In almost every category – roads, bridges, tunnels, water and sewer treatment plants – Reed’s data indicates that Canada’s infrastructure will require refurbishment or replacement. In some categories, sewage treatment plants for instance, those investments will be required very soon.

The Federation of Canadian Municipalities notes that “municipal infrastructure has reached the breaking point” and that failure to deal with the crumbling infrastructure is a “looming crisis for our cities and communities and ultimately for the country as a whole.”

And it’s not only existing infrastructure that requires attention. The development of new resource projects in Northern Ontario, Newfoundland, and elsewhere will require roads, rails, and power lines. As is evident from the development of Fort McMurray, resource extraction requires more than warm bodies and shovels. People need to live and play, resources need to be shipped and refined, and all of this requires energy and infrastructure.

The scope of work needed for municipalities – the FCM’s estimate from 2007 was 123 billion dollars- and the increased need for new infrastructure to accommodate the development of new resource sites, points to a continuation of the trend toward more jobs in construction, as well as an increased role for the sector in Canada’s overall economy.

Challenges and Opportunities in the New Canadian Economy

The sector is already facing significant labour shortages in skilled trades, and if current employment trends continue, these shortages will worsen, and may hamper growth not only in this sector, but in Canada’s overall economy. Two items on this front emerge as particularly worthy of policy makers’ attention:

- Labour mobility – Given the cyclical nature of construction, and given that projects often require massive amounts of labour for short periods of time, it is possible that large segments of skilled workers in province A will be unemployed even while Province B is facing labour shortages. Removing barriers which prevent workers in one part of the federation from working in another should be a high priority for policy makers. This presents challenges not only for streamlining qualification recognition, but also for labour unions, training centres, and other bodies working with labour.

- Labour standards – Closely tied to questions of labour mobility is the assurance of the highest quality standards for construction work. Given the flow of workers in and out of provinces with different qualification regimes – exacerbated even more by the influx of temporary foreign workers, and workers who are immigrating to Canada – the standardization of these regimes to allow for the greatest mobility of Canadian workers while maintaining the highest safety, skill standards, and productivity should be top priorities for provincial and federal governments. Trade unions and industry stakeholders also play a vital role in addressing this challenge.

Further, the question of who will pay for the massive infrastructure needs in Canada already presents significant challenges for federal, provincial, and municipal governments. While these discussions revolve around the sources of funding – who pays? – policy makers should also work to find ways to reduce costs of construction. A key part of this price reduction can be found by assuring that public construction procurement is fair, open, and transparent. As Canada’s leading procurement expert, Stephen Bauld, notes

It is in the interest of both Government and its suppliers for the procurement system to work well. In Canada, we have attained a level of honesty in Government contracting that is the envy of most of the World. Nevertheless, there remain serious problems with the process, which lead to frequent disputes and to significantly higher costs for Government than prevailing market conditions necessitate.

As we note in our Construction Competitiveness Monitor, eliminating legislative barriers which prevent qualified parties from bidding on public construction work is one of the most effective ways of achieving these savings.

Finally, the specific nature of construction’s role in our economy a raises important questions about the effects it will have on our social fabric. As noted above, much of the construction related to our resources takes place in remote parts of Canada, sometimes far removed from the tight social fabrics of our cities and towns. Likewise, construction employment is highly cyclical and, on an individual level, considerable less steady than other sectors. How will the influx and retreat of large numbers of workers in small towns affect workers’ health, crime rates, family cohesion, employment insurance programs, and other factors? Considerable work needs to be done to further that started in Cardus’ Working Mobile and Working Local papers.

Conclusion

Canada’s economy is driven by resources, and while much of these are found in Alberta, most other Canadian provinces have, or could have, similar opportunities. Canada’s resource base is varied and rich. In the process of developing these resources, construction has risen in importance. Mines, refineries, rails, and energy are all needed to keep that engine running and all of these require considerable construction investment.

The increase in this investment, combined with the global decline in manufacturing, means that construction employment is set to eclipse manufacturing as a leading source of Canadian employment. If more labour and investment is required to extract resources, an equal amount, or more, is required to meet Canada’s increasingly urgent infrastructure needs. These factors present significant challenges to Canadian policy makers and industry stakeholders, including owners, construction companies, and associations.