Introduction

Canada’s federal budget for 2021 included a $27 billion commitment to establish a $10-a-day childcare program within five years. Combined with additional funding, a total of $30 billion was committed in years one through five, with a projected annual cost of at least $9.2 billion in year five and later. The federal government then entered into negotiations with each province and territory (negotiating a unique asymmetrical agreement with Quebec, which has a program already) to jointly determine the funding and goals. These negotiations resulted in a “Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement” with each province and territory (which we refer to as “the Agreement” in this brief).

Cardus conducted its own costing estimate in 2021 prior to the release of the agreements, concluding that the federal government had underestimated the cost and complexity of implementing a national childcare program. 1 1 A. Mrozek, P.J. Mitchell, and B. Dijkema, “Look Before You Leap: The Real Costs and Complexities of National Daycare,” Cardus, 2021, https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/reports/look-before-you-leap. Cardus is now studying the funds spent and goals achieved in each province and territory annually. We will issue provincial and territorial reports for each year of the agreements as data become available.

The Agreement with Saskatchewan was signed on August 13, 2021. 2 2 Government of Canada, “Canada–Saskatchewan Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement—2021 to 2026,” August 13, 2021, https://www.canada.ca/en/early-learning-child-care-agreement/agreements-provinces-territories/saskatchewan-canada-wide-2021.html.

This brief presents the results for year one for Saskatchewan (fiscal year 2021–22, which is April 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022).

Year-One Summary

The province should be commended for meeting its obligation to publicly report on the progress under the Agreement, as many provinces and territories have not done so. 3 3 Government of Saskatchewan, “Canada–Saskatchewan Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement: 2021–2022 Annual Report,” 2022, https://pubsaskdev.blob.core.windows.net/pubsask-prod/138630/2021-22%252BAnnual%252BReport%252BCan-Sask%252BELCC%252BAgreement.pdf.

As the Agreement was signed in August of 2021, the province had a truncated term to complete ambitious targets, and the results reflect the difficulty of actioning a sudden influx of funding. The province sought an amendment to the Agreement to increase the percentage of first-year funding to be carried over to year two, from 60 percent to 64 percent. The province will have to overcome a stunted start in order to achieve targets in future years.

Families who are able to access licensed care in Saskatchewan saw a 50 percent reduction in fees, on average, during the second year of the program and were among the first in Canada to pay an average of $10 a day in fees by the beginning of the third year (April 1, 2023).

Despite notable achievements in the affordability of licensed care, the province fell well short of space-creation targets and struggled with other measures in the Agreement. It was able to allocate only 37 percent of the targeted 6,000 new spaces in year one, despite exceeding the year-one funding allocated for this purpose. This will increase the burden to create more spaces in subsequent years of the Agreement. According to the Ministry of Education, a net gain of 642 new spaces were operational by the end of year one.

As of the end of year one, only a minority of children under age six (about 18,500 children) were able to access highly subsidized care.

Future efforts to create spaces will have to contend with the shortage of early childhood educators. Efforts to address recruitment and training of personnel are scheduled for subsequent years of the Agreement, while funding from the “2017–2021 Canada–Saskatchewan Bilateral Early Learning and Child Care Agreement Workforce Annex” funded efforts in year one. The percentage of certified early childhood educators decreased by one percent during year one.

Efforts towards inclusion targets were underwhelming at best. The province struggled to provide greater accessibility for the targeted one hundred children in year one, overspending the allocated annual funds by 55 percent while meeting only 46 percent of its target. The province did not report how many vulnerable children it helped transition into childcare, though it set a target of 150 children. The province spent $400,000 of the $975,000 allocated for this goal in year one. No dollars were spent on developing a plan for First Nations and Métis engagement, although two meetings were held to discuss options. It should be noted that additional inclusion efforts were funded under the “Canada–Saskatchewan Bilateral Early Learning and Child Care Agreement.”

Regrettably the province did not report on the administrative costs associated with the first year of the Agreement. This is a key omission and a loss for public accountability.

The first year reflects the complexity and cost of administrating a provincial childcare system. The province reached its goal to reduce parent fees ahead of schedule, but results from year one overall illustrate the challenges in implementing the Canada-wide programs.

Agreement at a Glance

Term: April 1, 2021 to March 31, 2026

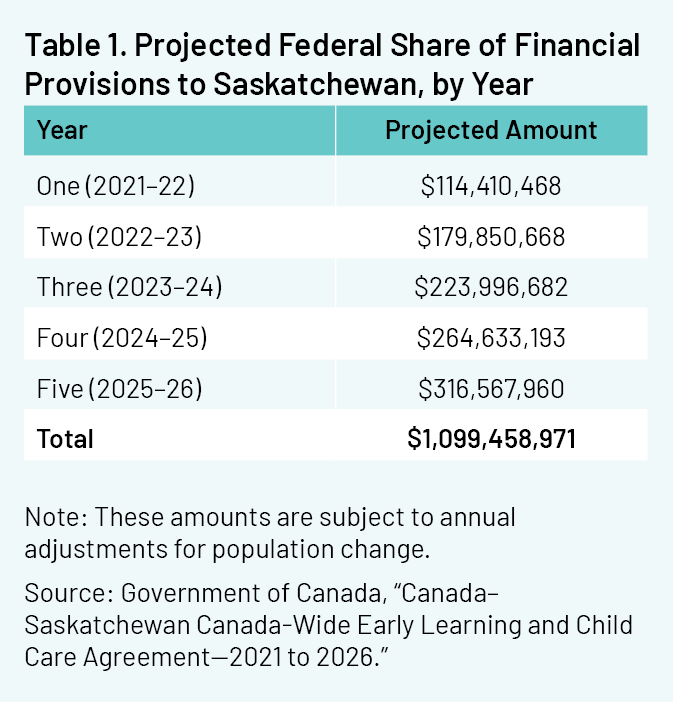

Federal Funding Estimate

Table 1 displays the projected federal share of financial provisions for each year of the Agreement.

Major Targets

- Reduce fee to 50 percent of the 2019 average fee in year one, and to an average of $10 a day by year five.

- Increase the number of regulated childcare spaces to 59 percent coverage for children under age six by year five.

- Create 12,100 full-time-equivalent spaces within years one and two, exclusively in not-for-profit and public providers, and a total of 28,000 new spaces in not-for-profit and public providers by year five.

Pre-Agreement Baseline Measures

- Provincial childcare budget of $71.2 million in 2019–20. 4 4 Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, “Annual Report for 2020–21,” Government of Saskatchewan, 2021, 37.

- Average parental fees of $335 to $1,300 a month as of March 2021, depending on the child’s age and type of facility. 5 5 Government of Canada, “Canada–Saskatchewan Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement.” This is the equivalent of about $11 to $43 a day.

- 17,665 full-time-equivalent regulated spaces as of March 2021. 6 6 Government of Canada, “Canada–Saskatchewan Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement.”

Agreement Targets and Results

The Canada-wide agreements share a similar structure, focusing on four priorities: affordability for parents, increasing access through space creation, making childcare more inclusive, and improving the quality of care.

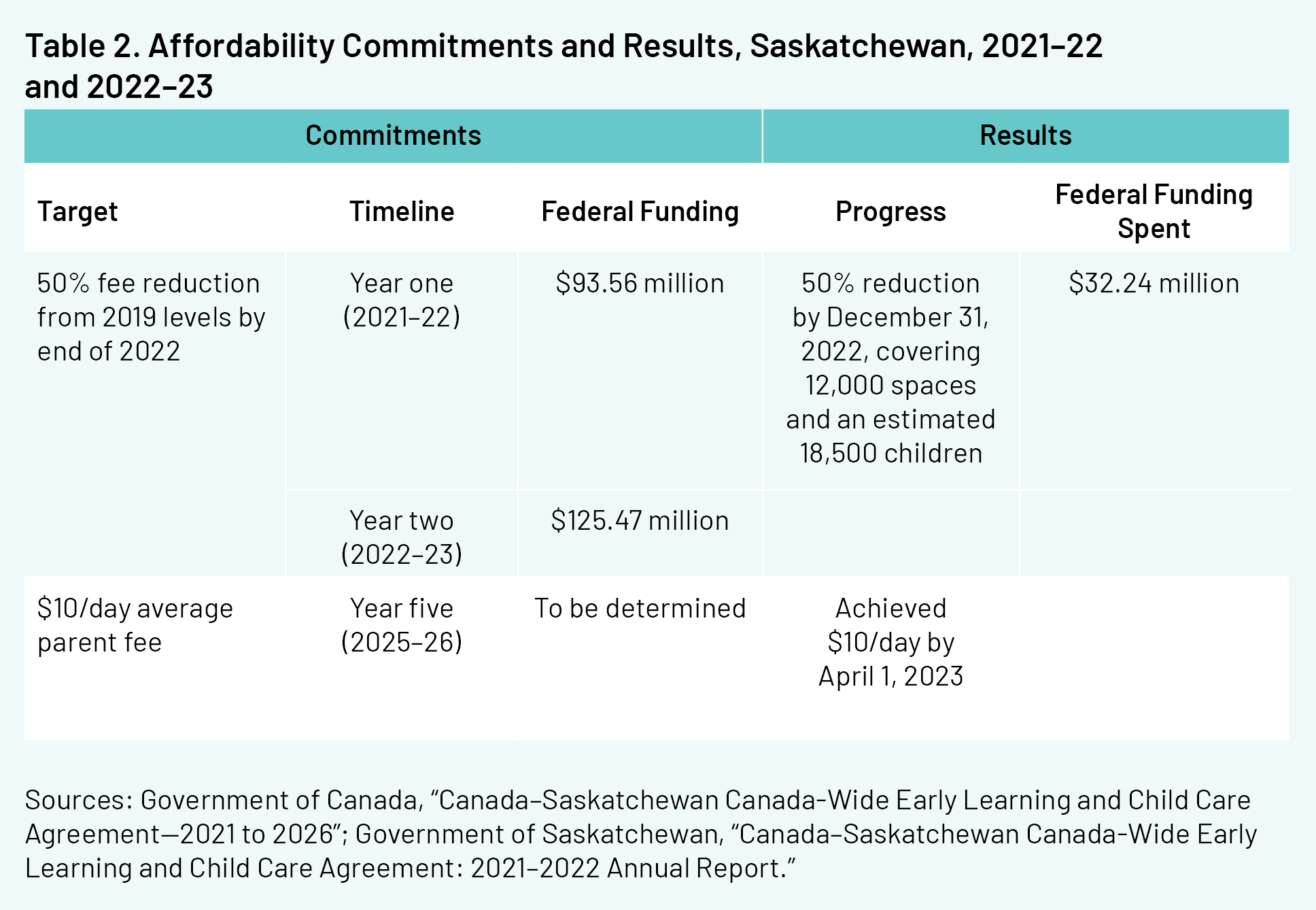

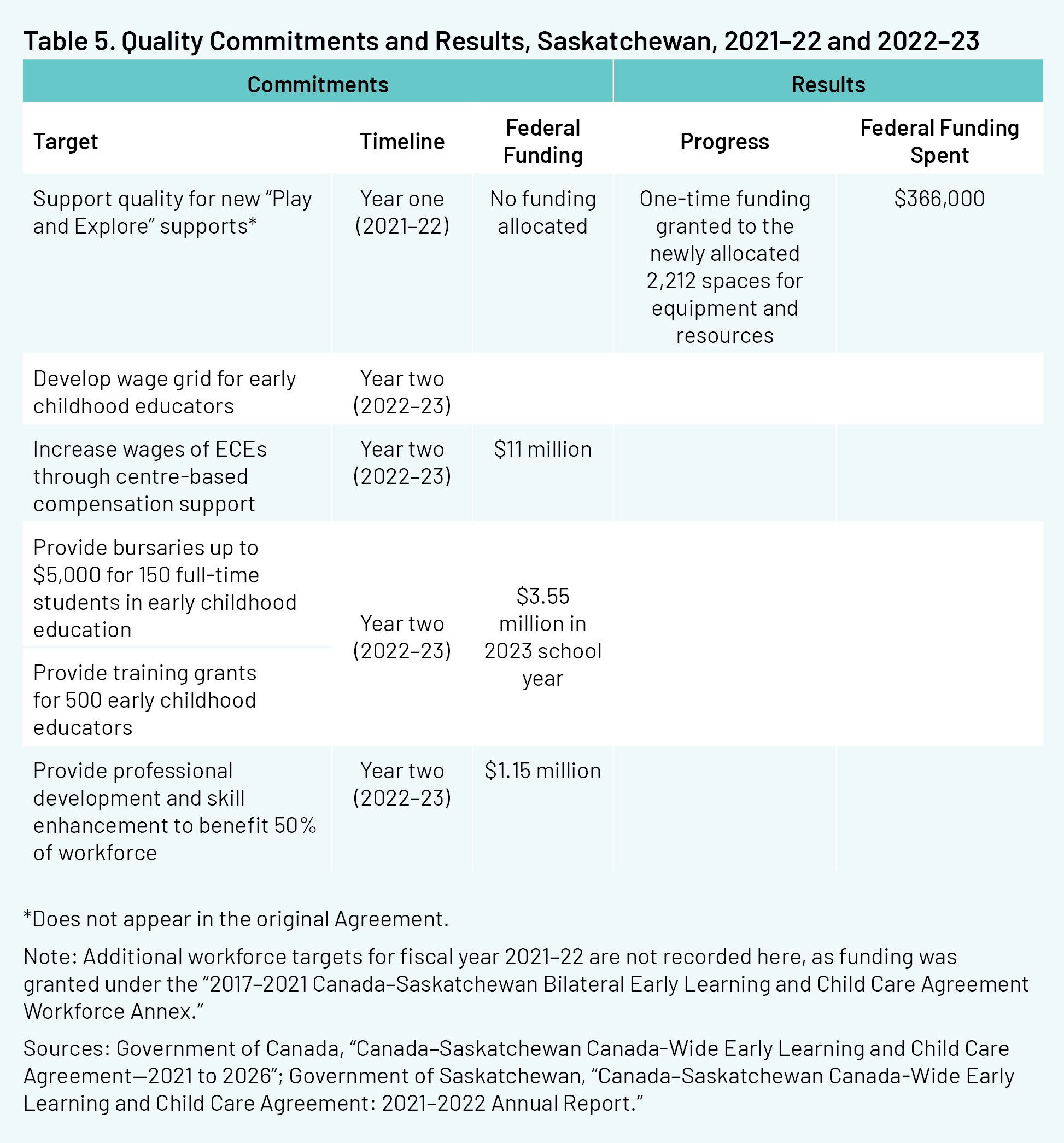

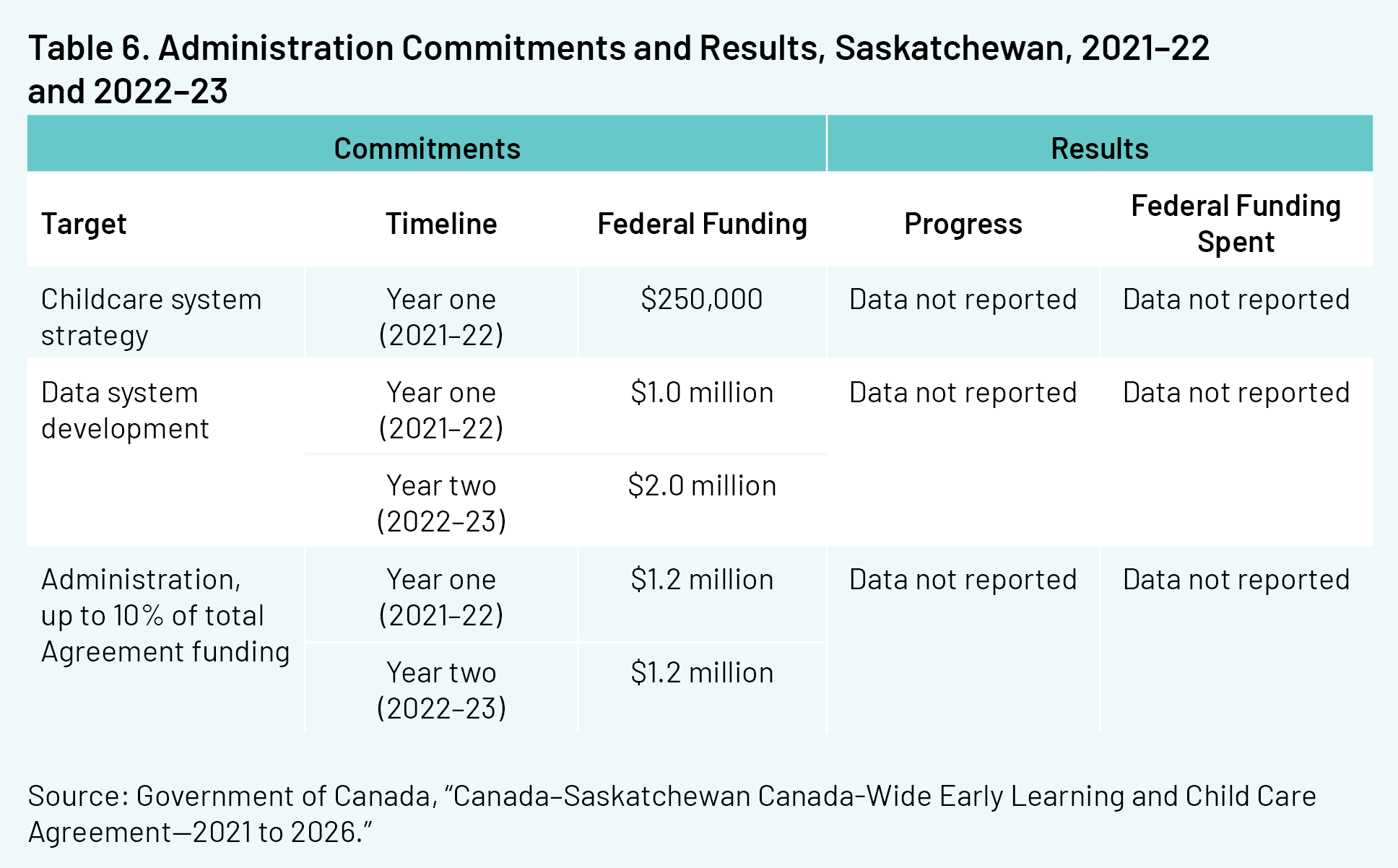

Saskatchewan provided an action plan for the first two years of the Agreement (2021–22 and 2022–23). The tables that we show here summarize the commitments made, the year in which targets are to be achieved, and the federal funding allocated to the targets.

The tables also summarize the progress made towards the target and the funding spent on these efforts in year one. Results and spending were publicly reported, per section 5.2.2.e of the Agreement, and the results that we show are taken from “Canada–Saskatchewan Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement: 2021–2022 Annual Report,” unless otherwise noted.

Affordability

While our brief focuses on the results of year one, it should be noted that Saskatchewan achieved its goal of reducing parent fees to 50 percent of the average 2019 fee by the end of year two. The province reports that in year one it spent about one third of the funding allocated toward this target (table 2). The reduction was applied to about 12,000 spaces. According to the Ministry of Education’s annual report for 2021–22, there were 18,308 full-time-equivalent licensed spaces in the province as of March 2022. 7 7 Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, “Annual Report for 2021–22,” Government of Saskatchewan, 2022, 22. As the Agreement applies only to children under age six, not all spaces qualify for the fee reduction.

In addition to attaining a fee reduction of 50 percent in year two, the province is among the first to reach a province-wide average fee of $10 a day. While families able to obtain a subsidized licensed spot will benefit from this significant fee reduction before their peers in most other provinces, it is important to note that a majority of the 87,574 children under age six in the province are not in licensed care and receive no benefit from this achievement. 8 8 The number of children in the province is taken from “Saskatchewan Population by Age and Sex: 1971 to Date,” Demography, Census Reports and Statistics, Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics, https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/government-data/bureau-of-statistics/population-and-census. As noted above, there were 17,665 regulated full-time equivalent spaces for children of all ages in 2021, meaning a majority of children under age six are not in a regulated child care space.

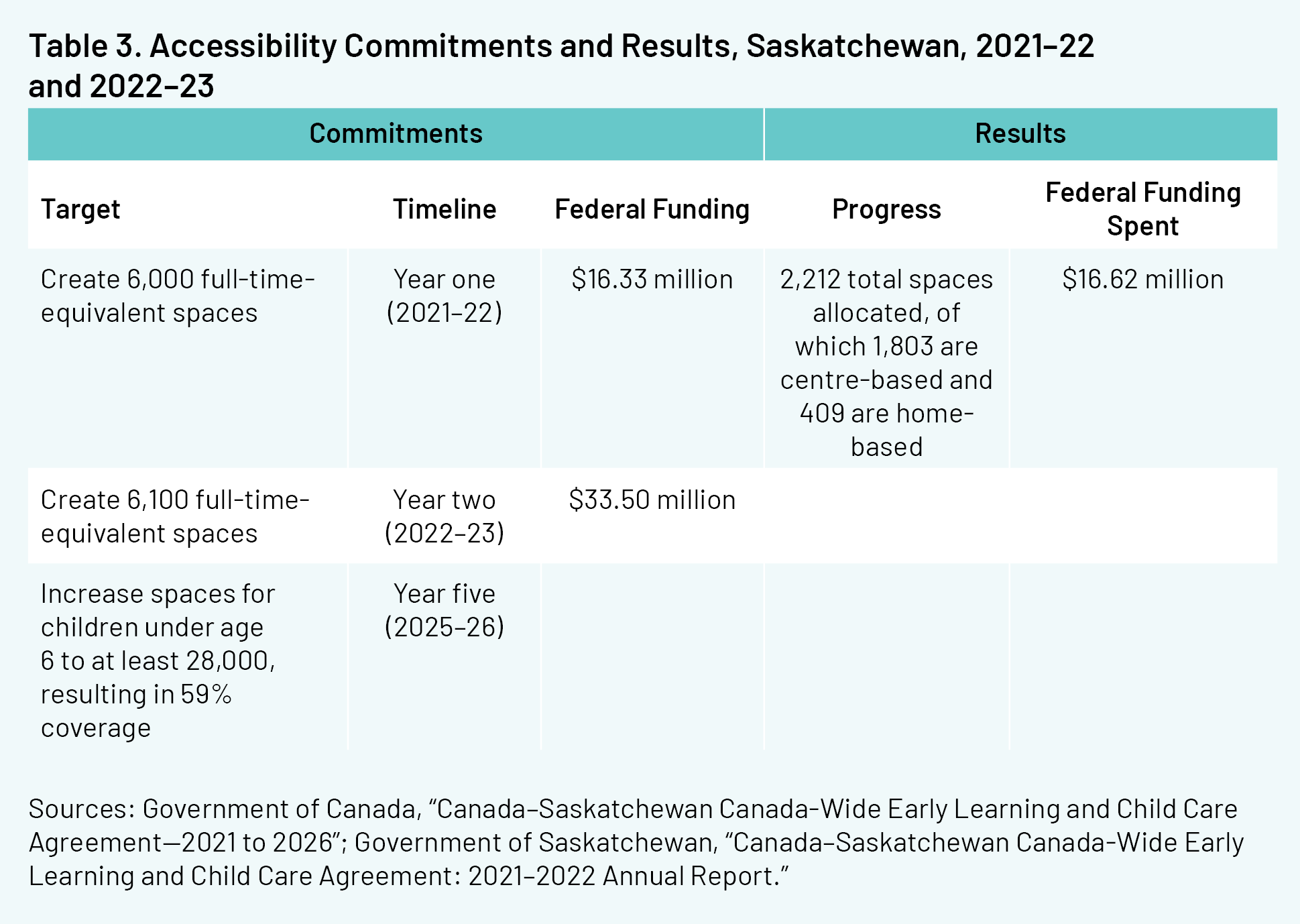

Accessibility

The province underperformed in its efforts to create new childcare spaces in year one, allocating only 37 percent of the targeted number (table 3). The action plan called for the creation of 6,000 full-time-equivalent spaces, but the province managed to allocate only 1,803 centre-based spaces and 409 home-based spaces, for a total of 2,212 new allocated spaces. Despite falling short of the space-creation target, the province exceeded the space-creation budget by $289,000.

Allocated spaces are not necessarily operational spaces, nor does the number of allocated spaces account for the number of licensed spaces lost due to facility closures. A comparison of Ministry of Education annual reports for 2020–21 and 2021–22 shows a net gain of 97 licensed home-based spaces and 545 licensed centre-based spaces, for a net addition of 642 operational licenced spaces by the end of year one. 9 9 Calculations by author from Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, “Annual Report for 2020–21,” 25; Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, “Annual Report for 2021–22,” 22. The annual reports do not specify how many of these spaces are for children under age six.

Having allocating only 8 percent of the spaces promised under the five-year Agreement in year one, and presuming that all allocated spaces become operational, the province will need to create 25,788 spaces over four years to reach its 2026 target: a pace equal to 6,447 new spaces a year.

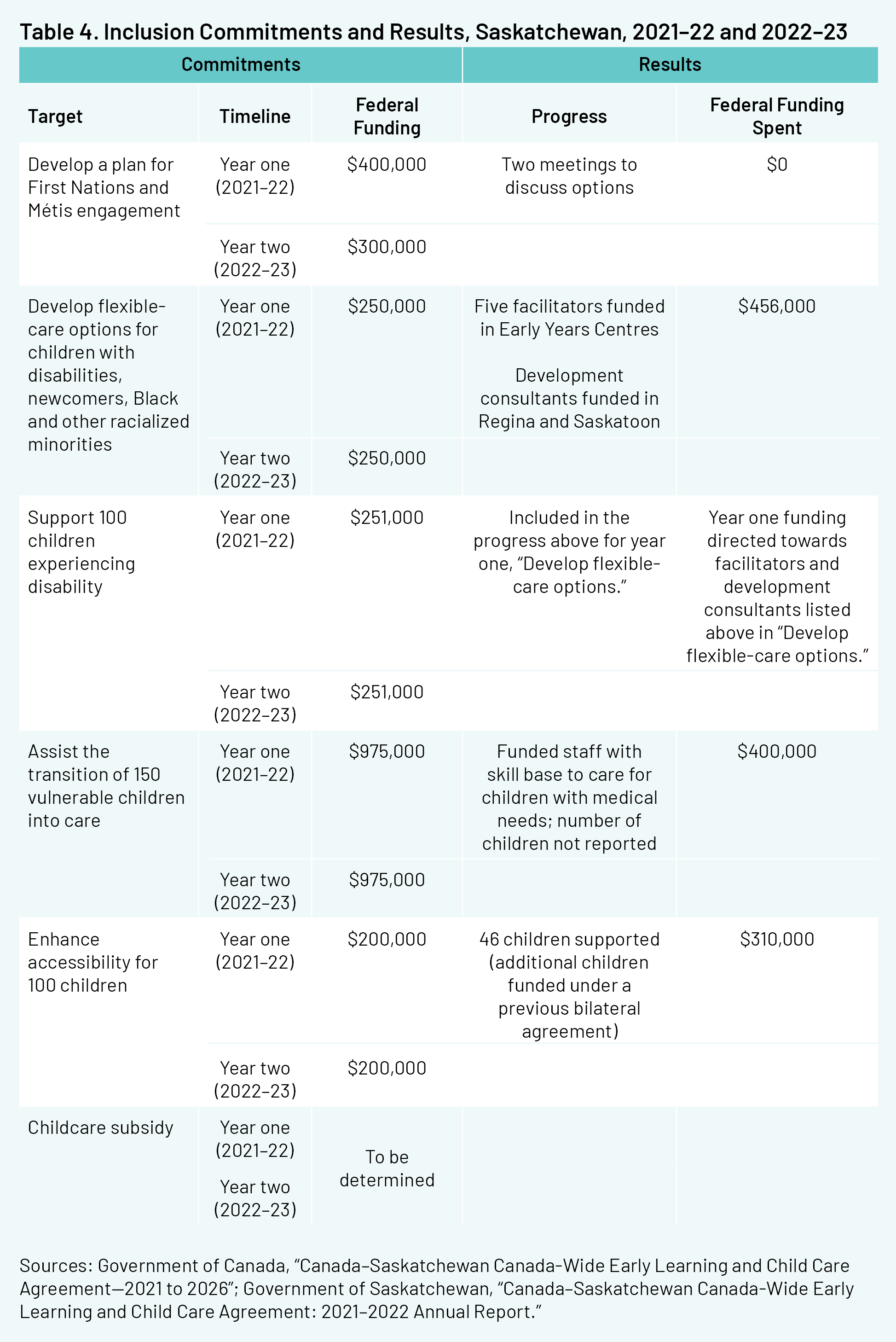

Inclusion

Efforts to address inclusion in year one focused on planning, grants to providers, and funding facilitators and consultants. Although the targets specify the number of children to be served, publicly released data are sparse. Where the number of children served is reported, the numbers fall well short of the target.

The province reports spending none of the $400,000 granted to develop a plan for First Nations and Métis engagement, though two meetings were held to discuss options (table 4). Five childcare facilitator positions were funded in Early Years Resource Centres to develop flexible-care options for children with disabilities and minority children. These centres provide a number of support services for families and host activities for children. Additionally, two developmental consultants were funded to help build capacity in centres and home-based care, to accommodate newcomers, children with disabilities, and minority children. Funding earmarked to support an additional one hundred children with disabilities was committed to this target. Transferring funds between targets is permitted within the first year of the Agreement.

Less than half of the amount of funding to assist the transition of 150 vulnerable children into childcare spaces was spent. Funding was directed toward staff with the skill base to care for children with medical needs. The number of children served was not reported.

The province overspent by $110,000 to enhance accessibility, reaching 46 percent of its target number of children. Funding was distributed to providers through the Enhanced Accessibility and Inclusion Grants, which are funded from provincial funding, an existing bilateral agreement, and the “Canada–Saskatchewan Canada-Wide Early Learning & Child Care Agreement,” and supported an additional 487 children. According to Ministry of Education annual reports, the province increased the number of Enhanced Accessibility grants by sixteen over the previous year, for a total of 412. An additional two Inclusion grants were provided, for a total of 75. 10 10 Calculations by author from Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, “Annual Report for 2020–21,” 25; Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, “Annual Report for 2021–22,” 22.

It should be noted that additional inclusion efforts were funded under an existing bilateral agreement, beyond the targets set in the Agreement.

Quality

Additional workforce targets for year one are not recorded here, as funding was granted under annex 3 of the “Canada–Saskatchewan Early Learning and Child Care Agreement.” 11 11 Government of Canada, “Canada–Saskatchewan Early Learning and Child Care Agreement,” annex 3.

Recruitment of early childhood educators appears to be a challenge in the province, as it is across the country. Much of the work of recruiting and retaining qualified personnel was funded under the “Canada-Saskatchewan Bilateral Early Learning and Child Care Agreement—2017 to 2021” and are not reflected in this evaluation. Those efforts included professional development and one-time funding for wage enhancement.

Quality targets under the Agreement are heavily weighted toward the future years of the Agreement. In year one, a one-time grant available for the newly allocated 2,212 spaces was intended for the purchase of equipment and resources to enhance active play and to implement the province’s framework in regulated childcare that is outlined in “Play and Explore: An Early Learning Program Guide.” 12 12 Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, “Play and Exploration: Early Learning Program Guide,” Government of Saskatchewan, April 2008, https://publications.saskatchewan.ca/#/products/74066. The province aims to increase the percentage of staff with the qualification of early childhood educator levels I, II, and III by 15 percent by the end of year five. The portion of qualified early childhood educators decreased one percentage point during year one of the Agreement (table 5). 13 13 Government of Saskatchewan, “Canada–Saskatchewan Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement: 2021–2022 Annual Report,” 14.

Administration

The province did not report on the progress toward or funding for planning, reporting, and administration. This is a significant shortcoming in public accountability. The Agreement allows the province to spend up to 10 percent of funding on administrative costs. Just under $2.5 million was budgeted for these costs in year one (table 6).

Legislative and Policy Changes

The Agreement allows the province to carry forward up to 60 percent of funding from year one to year two. An amendment dated March 1, 2022 increased the carry-forward allowance to 64 percent. 14 14 Government of Canada, “Agreement to Amend the Canada–Saskatchewan Canada-Wide Early Learning and Child Care Agreement—2021 to 2026,” 2022, https://www.canada.ca/en/early-learning-child-care-agreement/agreements-provinces-territories/saskatchewan-canada-wide-2021/amendment.html.

Additional Observations

In a November 2021 press release, the province encouraged unregulated providers to join the licensed system and indicated that applications for licensing from existing unregulated providers would be given priority. 15 15 Government of Saskatchewan, “Government of Saskatchewan Encourages Home-Based Child Care Providers to Become Regulated,” November 25, 2021, https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/news-and-media/2021/november/25/government-of-saskatchewan-encourages-home-based-child-care-providers-to-become-regulated. The provincial report does not specify how many unregulated providers transferred into the system. While transfers into the system would represent a growth in the supply of licensed spaces, most of these spaces would already be occupied and have little impact toward increasing care options.

Predictably, some parents left unlicensed providers for heavily subsidized care, as not all unlicensed providers chose to or were able to meet licensing requirements. One parent who used an independent home-based provider told Global News that “her previous provider looked into getting licensed but couldn’t meet the requirements for licensing because they are renting their space.” 16 16 T. Charles, “Providers and Parents Struggle to Navigate Saskatchewan Child Care Regime,” Global News, April 2, 2022, https://globalnews.ca/news/8729848/saskatchewan-child-care-competitive-industry-providers-parents/. A licensed home-based provider who planned to open an additional service told Global News, “Other providers have called me saying sadly they have to close because of their house or others issues. They cannot get licensed so they are losing parents.” 17 17 Charles, “Providers and Parents Struggle.”

The province initiated a similar campaign in November 2022 (year two) to encourage unregulated home-based providers to join the licensed system. The province has not provided data on the number of unregulated providers who joined, but it indicated in an April 2023 email to Cardus that the application form and the “Becoming a Regulated Family Child Care Home Checklist” were each downloaded over one thousand times from the province’s website. 18 18 Government of Saskatchewan, “CWELCC Annual Report,” email correspondence with author, April 25, 2023. The province did not provide data on how many applications were submitted.

While families using licensed care in Saskatchewan will receive significant reductions earlier than parents in some other regions, media reports suggest that this achievement may come at the cost of part-time licensed care. 19 19 L. Sciarpelletti, “Sask. Child-Care Providers Say They’re Scrambling to Prepare after Province Rushed $10/Day Program Rollout,” CBC News, March 15, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/child-care-10-a-day-program-rollout-rushed-1.6778743. These spaces are not covered by the funding. The difficulty and expense of providing these spaces are a disincentive for providers.

As the province fell significantly short on space-creation goals during year one, Saskatchewan will need to significantly increase space creation in future years in order to meet its obligations under the Agreement. As objectives and funding amounts increase over the term of the Agreement, the province should be proactive in publicly reporting administrative costs associated with implementing the Agreement.