This paper was first delivered as a public lecture on November 9, 2023 at Cardus in Ottawa, Ontario. The text has been lightly adapted for publication.

Key Points

- This paper offers key perspectives on current trends in independent education in North America. It argues that the goal of education is two-fold: the formation of personhood—body, mind, and spirit; and the formation of citizens, who participate in a shared society. These goals are best achieved through a plurality of educational options, including independent schools.

- Subsequently, this paper highlights current trends in education innovation:

- increases in student enrolment in independent schools and homeschooling,

- increases in the types of independent school, and start-ups of new ways of educating, such as hybrid schools, microschools, and other pedagogical approaches,

- increases in research on independent schooling and strengthening of policy supporting school choice across North America,

- and a renewed interest in philanthropic and corporate support of new and innovative forms of education.

- Concurrent with these trends are a consequence of challenges within district (public) education, and this paper describes research outcomes on pandemic learning loss and declines in academic achievement, rising concerns of chronic absenteeism, increased violence in schools, difficulties retaining teachers, and significant reports of declining mental health and wellbeing among both students and educators. These concerns are compounded by public perception that district systems increasingly provide education that is ideological in content.

- This paper concludes that we are leaving an era of educational uniformity and entering an era of education plurality, evident through a diversity of providers, approaches, learners, and funders. Pluralism, by definition, does not prioritize or prize one version of education over another. Rather, all are expected to be excellent spaces. What is key is that a variety of secular, philosophical, and religious schools can all contribute to the common good, to flourishing students, and to healthy civic formation.

- Finally, a call to action is issued for the expansion of educational pluralism: for generous funding and philanthropy in support of independent education, for meaningful participation in local education initiatives, and for advocacy toward a renewed commitment to plural education.

Introduction

It is almost four years since we got word that we were experiencing a global pandemic and were instructed to head home. And since then, you’ve had a hunch that things might not go well for kids or schools. You knew, no matter whether you were a parent, teacher, or regular Canadian, that the immediate and the longer-term impact of cloistering all students in their own homes for extended periods, without real external supports, was going to be significant.

You were correct, and you still are. What we are seeing in elementary and secondary education today is markedly different from what we could observe even four or five years ago. And it certainly is different from when you sent your kids to school or went to school yourself. Absenteeism is up. Achievement is in decline. Violence in schools is growing. Teacher retention is in free fall. A few dominant ideologies reign. Regard for history is low. Book removals are on the rise. Mental well-being is down. Anxiety is up. And learning loss is real.

But there is hope. Beautiful changes are happening too. So let’s take a walk over to the window, throw open the shutters, and take a look. What we are seeing is nothing short of dramatic. Taken together, the changes in the alternatives to K–12 public schooling are staggering. Enrolments are up in many independent schools across the country. Wait lists are now common. Homeschooling uptick is significant. And not only are enrolments up, more independent and private schools are opening than ever. All in all, more types of schools and approaches to schooling are available.

First, different curricular content is blooming: think forest schools or arts-based schools. Different delivery approaches are also on the rise: think hybrid schools, microschools, learning pods, part-time at home and part-time at school. Are they even schools, or are they homeschool cooperatives of a new sort? Then consider the spaces being used for schools. Public spaces, community centres, and religious hubs are all being multi-purposed so they can be sites for K–12 education during the weekdays.

Now, I have a unique position as leader of a vibrant independent-school association in Ontario, and my team and I get phone calls the average person might not get. But together they add up to a trend. And I want to give you a peek into them.

I’m thinking of my conversation with William this week, the lead pastor of a thriving church with thousands of weekly worshippers. The church recently opened a daycare for seventy-five, hit capacity, and has more than three hundred on the wait list. “We’re thinking of opening a JK–6 school,” he said in our Zoom call. “We already have a dance studio, a tech studio, multi-purpose gymnasium, and classrooms. Let me bounce ideas off you.” We discussed curriculum with lots of space for experiential learning, parent roles, teachers, and governance. In the end, his biggest question to me was, “Do you think we can get this up and running by September 2024?”

Or what about my conversation with Marcus two weeks ago. “We’re an independent K–8 Christian school, a few decades old. We’re in a key city in a northern region of the province, and we just did a beautiful facilities upgrade. We’re humming with growth. We’ve connections with local leaders in the natural-resources industry, think we have an educational niche, and want to start a high school. Do you think we can do it?” And like William, Marcus added, “And do you think we could we do it by next year?”

I’m also thinking of conversations I’ve been having with Allison, who is the owner-operator of an international shipping company, and several of her friends in a central Ontario area. A key priority for this parent group, they said, is that “no child should spend more than ten minutes in a vehicle on their way to school. So we want to set up a multi-campus hybrid school. Do you think this is possible to do?” And like others, they are asking, “Do you think it is possible by next year?”

So many similar stories; so many similar calls. The tone is always tentative, but underneath is a tenacity. All across the province of Ontario, and in many provinces beyond. I recall the homemade bread and sausages that Brielle, one potential school founder, baked for our early-morning exploratory meeting in a Maritime province last September.

As you may expect, there’s more to this story that I am shaping here. It isn’t just parents who are fed up and making new choices for their kids’ education. Or teachers or community members or religious leaders who are exasperated with their current options and coming together to discuss and to creatively open up new schools based on innovative ideas and approaches. Other stakeholders have entered the space in serious ways. Philanthropists, researchers, businesses, and governments are changing their posture and becoming involved.

So, why do these trends matter? Why take this time to identify them and try to understand them? They matter because education matters. It matters for our individual well-being, for our civic health, and for our national and global stability, growth, and flourishing. It matters for our children and grandchildren. Everything hangs on this. And it all depends on ordinary people recognizing this moment, coming together, and then acting.

I’ll begin by outlining and arguing why this moment is significant. Then I’ll give evidence for the trends we’re seeing. Finally, I’ll conclude with what these trends mean about our current education moment and, if this analysis is correct, what it all means for what needs to happen next.

Why Education Matters

Let’s begin with why this matters. In fact, why does education matter? Of course, there are many reasons, but a few stand out. On these the flourishing of humans and of civilizations rest.

Personhood

First, it matters because the children we are responsible to raise and educate are persons—whole human beings with bodies, minds, and spirits. They are not free-floating, autonomous, isolated beings, designed to live a utilitarian existence of and for themselves, alone and even lonely. Rather, they are born in and for relationship—with other personal selves and with the non-personal world—for to be a person is to be a being in relation.

The philosopher Michael Polanyi says that student learning is about “commitment to the truth, capacities to perceive value of potential discoveries, active engagement in inquiry, the exercise of artful skills, reliance on tacit understanding, the making of judgements of beliefs, the discernment of patterns and meanings in holistic gestalts of data, appreciation for the beauty of the known world. . . passion for and joy in discovery. . . . All . . . clearly activities of a thoroughly personal nature.” 1 1 C. Smith, What Is a Person? Rethinking Humanity, Social Life, and the Moral Good from the Person Up (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 181, paraphrasing M. Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-critical Philosophy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962).

The education of persons, philosopher James K.A. Smith says, is not primarily about absorption of ideas and information but about the formation of hearts and desires, about “shaping our hopes and passions—our visions of ‘the good life.’” In fact, Smith asks, “What if the primary work of education is the transforming of our imagination rather than the saturation of the intellect? . . . What if education wasn’t first and foremost about what we know, but about what we love?” 2 2 J.K.A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009), 18.

Perhaps Charlotte Mason, the influential British theorist of education from the early twentieth century, summarizes personhood and its implications for education best when she states that “education is the science of relations.” 3 3 M. Mason, An Essay Towards a Philosophy of Education: A Liberal Education for All (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co, 1925), 154. “We owe it to [children] to initiate an immense number of interests,” 4 4 M. Mason, School Education (Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1989 [1907]), 170. that is, “to build relationships and love for persons . . . for the natural world and mysterious aspects of the universe, and for the transcendent, the divine, for God,” 5 5 D. Van Pelt and J. Spencer, Students as Persons: Charlotte Mason on Personalism and Relational Liberal Education, Charlotte Mason Centenary Series (McKinney, TX: Charlotte Mason Institute, 2023), 64. and to do so through a wide and “generous curriculum, that would introduce them to the great ideas of history, art, music, architecture, science, mathematics, and poetry.” 6 6 D. Van Pelt and Spencer, Students as Persons, 60.

Through it all, “the question is not,” Mason says, “how much does the youth know? when he has finished his education—but how much does he care? And about how many orders of things does he care? In fact, how large is the room in which he finds his feet set? And, therefore, how full is the life he has before him?” 7 7 C.M. Mason, School Education, 171.

So, education matters because it is the formation and flourishing of human persons that we are dealing with.

Civic Formation

But there’s more. Think Canada for a moment. Our civic posture, our civic organizations, Indigenous reconciliation, and our valuing of our most vulnerable citizens depend on our children being well educated: knowledgeable, moral, and caring. Our moment of constitutional fragility demands that our young be historically knowledgeable and in magnanimous relation with other Canadians past, present, and future. Our economic prosperity depends on ambitious, innovative, knowledgeable, and virtuous citizens: employers and leaders building healthy and sustainable ways to live and work and flourish, and employees committed to good work and innovation. Furthermore, Canada needs culture-makers, creators of beauty, contributions for now and for our future.

Think global posture. Do we care about being internationally competitive? Do we want to be a society that attractively offers a place for the world’s best and brightest to call home? How will we contribute to justice in this world? What will be our participation in or response to horrific moments of global conflict? Our posture toward human dignity and the flourishing of persons—each with inherent, immeasurable, God-image-bearing value—is pressing. And the stances and solutions are found in the relations with ideas and knowledge that we build through the education we offer.

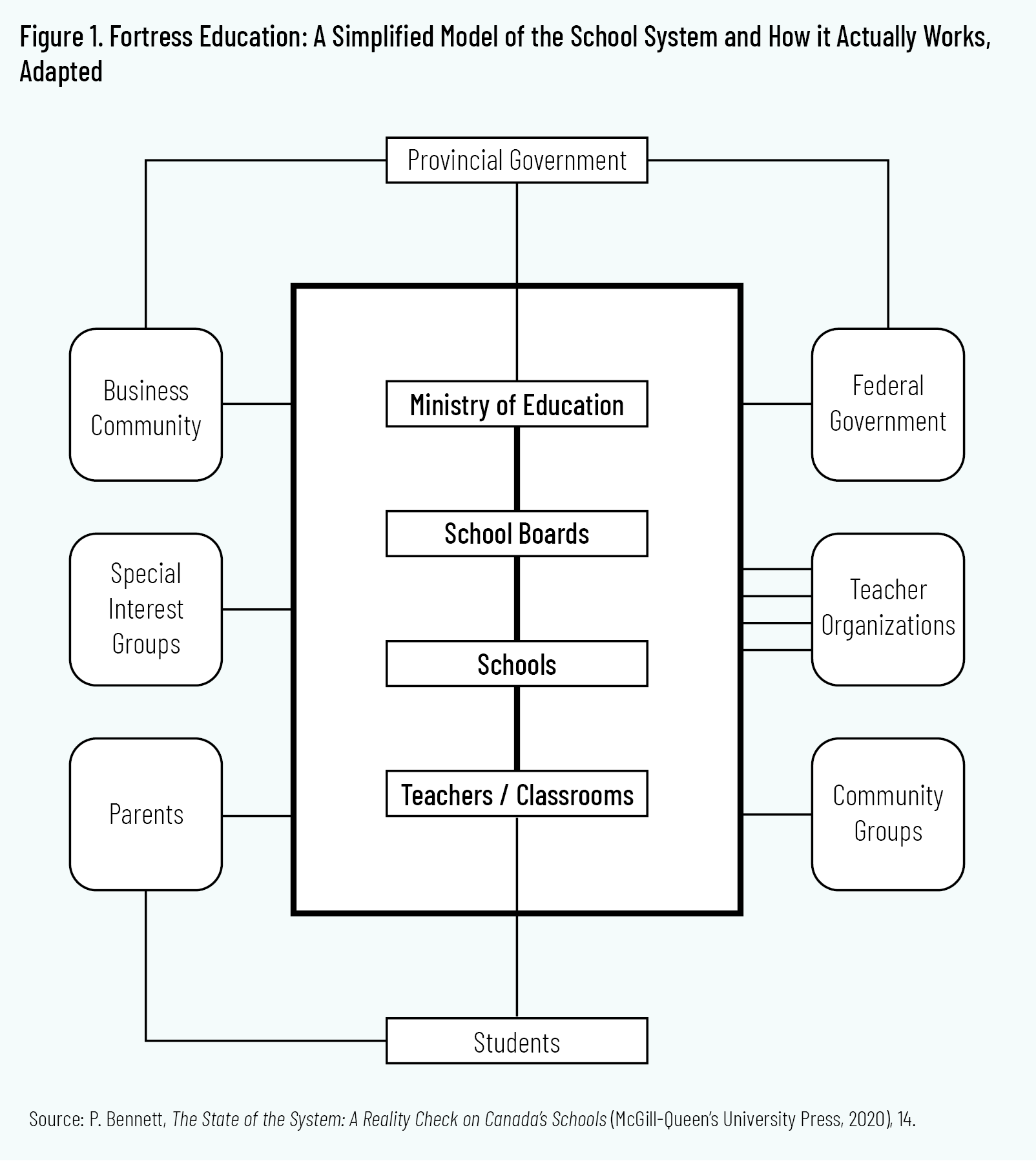

Let’s talk about the trends we’re seeing, many of which I hinted at in the beginning of this talk. The trends could be understood to be of two types, those inside “the fortress,” and those outside. Allow me to explain. Paul Bennett, in his work The State of the System: A Reality Check on Canada’s Schools (published just before the pandemic), reminds us of a model of the Ontario school system drawn up in 1993 and which Bennett suggests still applies today. 8 8 P.W. Bennett, The State of the System: A Reality Check on Canada’s Schools (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020). It uses the label “fortress education” to describe the closed-system world of education in Ontario, divided into insiders and outsiders.

While my talk today focuses on education in Canada, not just Ontario, and while we might quibble about what is or isn’t labelled on some of the bits of figure 1, the metaphor of a fortress is apt for the phenomenon that I am considering, and I’ll use it here as I analyze some of the trends I’m seeing.

Trends Outside the Fortress

Let’s look first at the trends outside the fortress, the education space where government is not the primary agent offering or delivering the education, the space, beyond public schools, where other forms of K–12 education takes place. Inside the fortress, education is directly governed by government policy and delivered by educators for the government. Outside the fortress, K–12 education may not be offered, but is not delivered by government.

I’d like to build my argument by taking a look at trends in enrolments, school start-ups (including hybrids and microschools), and types of independent schools, along with trends in research and policy and other areas of support for independent schooling.

Increasing Enrolment

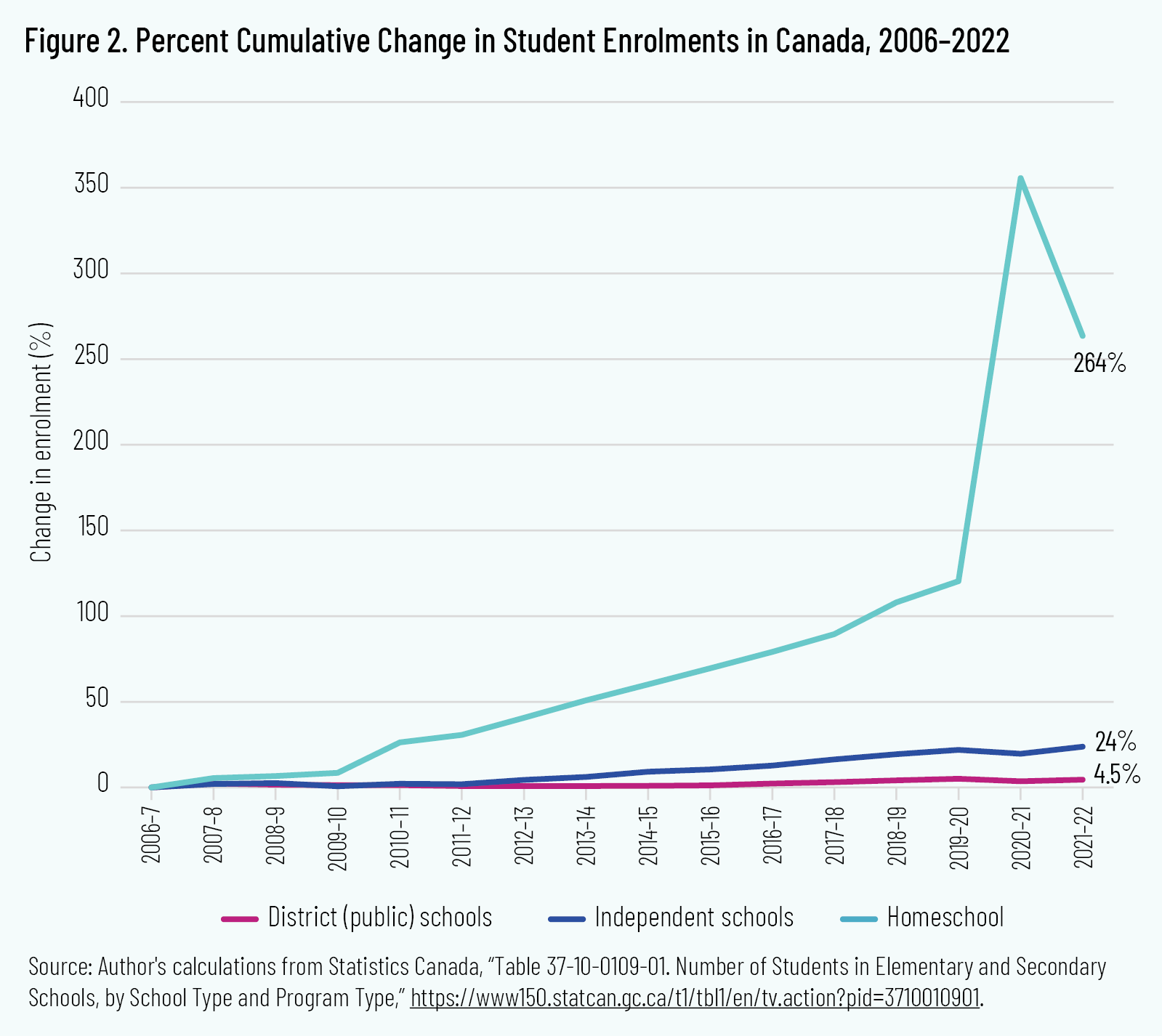

Our latest data for Canada that is comparable across provinces is already two years old. But comparing 2021–2022 data with previous years is still very instructive. Statistics Canada gives us sixteen years of data that we can use for comparison purposes, the period from 2006 to 2022.

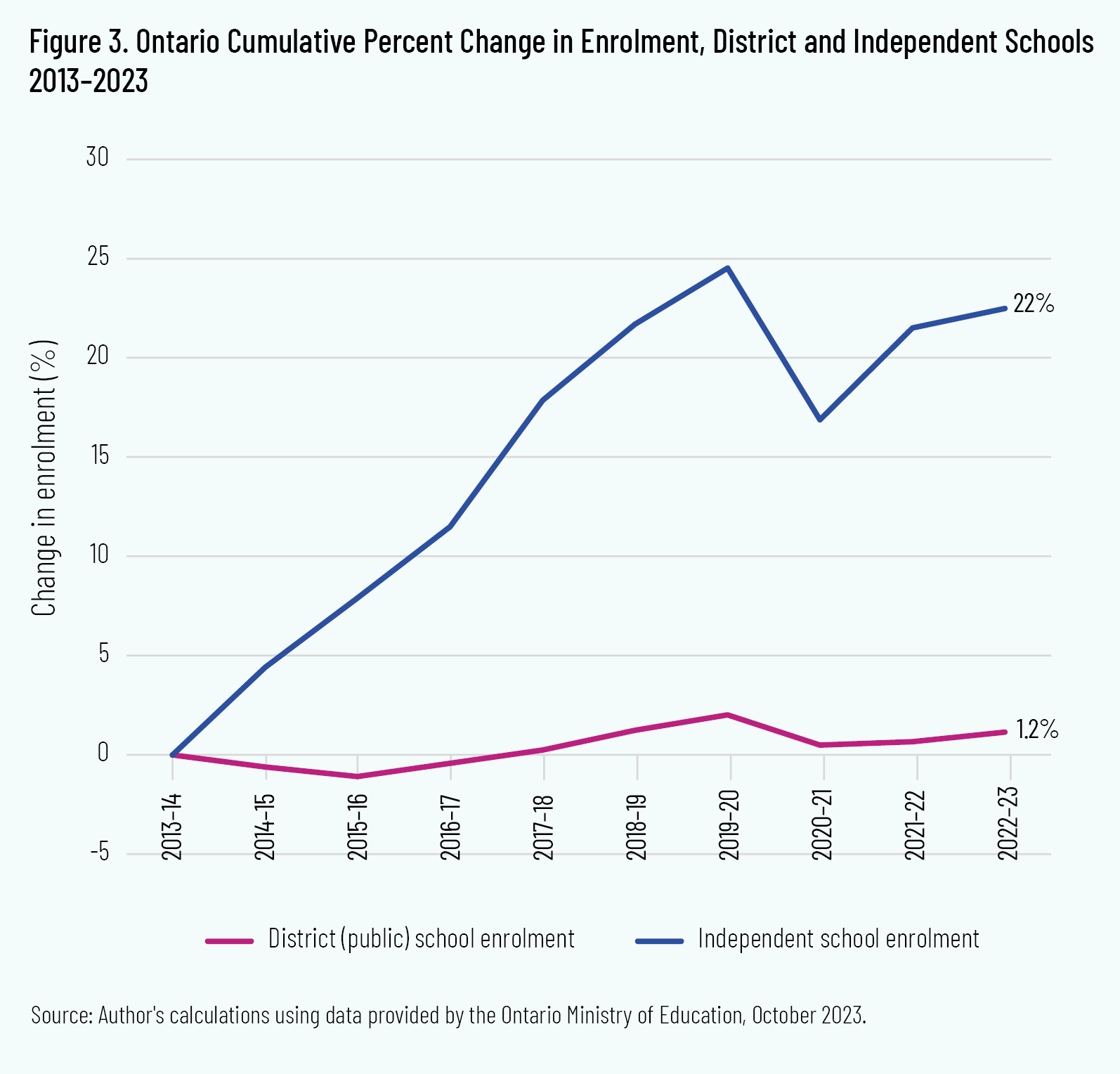

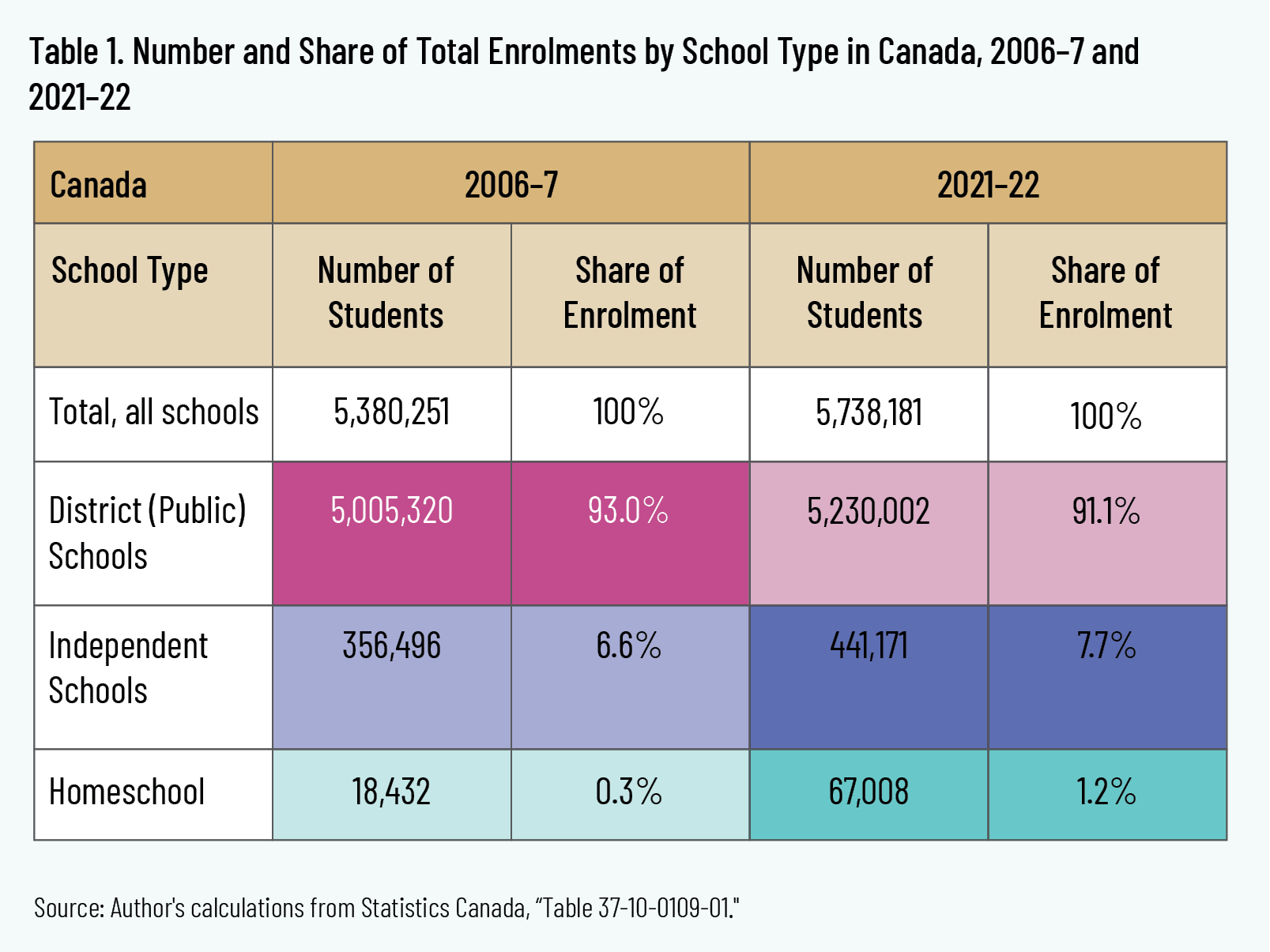

Taken together, all types of K–12 schooling in Canada saw enrolment increases (figure 2). Public schooling showed the smallest total increase, 4.5 percent, with independent-school enrolments growing by about one-quarter (23.8 percent), and homeschooling enrolments almost tripling (264 percent). Notably, the Washington Post recently reported similar enrolment changes in the US. 9 9 For a visual depiction of the percent increase in student enrolment in the US from 2017 to 2023, see the first figure in P. Jamison et al., “Home Schooling’s Rise from Fringe to Fastest-Growing Form of Education,” Washington Post, October 31, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/interactive/2023/homeschooling-growth-data-by-district/. Notice as well the increase in independent-school enrolments over the last decade compared to public-school changes in Ontario, for example: 22 percent growth, compared to just over 1 percent (figure 3).

Christian School Enrolments

We know that enrolment in Christian schools has continued to increase. The Association of Christian Schools International, reporting data for the US, shows that about one-third of Christian schools had an enrolment increase from 2019 to 2022, following lockdowns and pandemic-related school closures. 10 10 L. Swaner, J. Eckert, E. Ellefsen, and M. Lee, Future Ready: Innovative Missions and Models in Christian Education (Colorado Springs: Association of Christian Schools International and Cardus, 2023), 3.

The association that I am most familiar with, Edvance Christian Schools Association, is reporting consistent and sustained interest and increase in enrolment, solid year-over-year increases through new schools, and increased enrolments in existing schools. 11 11 Edvance, 2023 student enrolment comparisons, proprietary data provided by the author.

Share of Total Enrolments

The changes in the share of all students in each sector in Canada also tells a story. Where 93 percent of students attended public school in 2006, as of 2021 this proportion had declined to about 91 percent. Where 6.6 percent of students attended independent schools in 2006, as of 2021 it was 7.7 percent. And where 0.3 percent were registered as homeschooled in 2006, in 2021 it had risen to 1.2 percent of all students. 12 12 Statistics Canada, “Table 37-10-0109-01. Number of Students in Elementary and Secondary Schools, by School Type and Program Type,” https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710010901. Thus 9 percent of all students were educated outside government schools. And we know these statistics under-report the actual case.

Today, with two more years of trending and under-reporting, we can assume that up to 11 or 12 percent of all students in Canada are educated somewhere other than government schools.

- Independent-school enrolment in any one province is as high as 13 percent (in British Columbia). Nearly 15 percent of K–12 students in BC are educated either at independent schools or at home or, increasingly, a combination of the two.

- Boundary “public school” enrolment (excluding separate and francophone schools) is as low as 66 percent (in Alberta). 13 13 D. Hunt and J. DeJong VanHof, “Pluralist Province: The Landscape of Independent Schools in Alberta,” Cardus, forthcoming. In other words, one in three Albertan kids are educated somewhere other than their local government-run school.

- In absolute terms, of course, Ontario has the largest number of independent and homeschool students, at almost 166,000 in 2021. Even without any public funding, they make up almost 8 percent of K–12 enrolment in the province.

- Homeschool participation in some provinces is nearly as high as 3 percent (in Saskatchewan and Alberta). And that’s only what’s reported by Statistics Canada; credible estimates peg homeschoolers closer to 6 percent in the prairie provinces.

Enough about enrolments. In all, the story for Canada is that the share of enrolments outside the fortress is growing.

New Schools Starting

This is also a moment of growth for new school starts. A decade ago, in 2013, Ontario had 954 independent schools in operation. Now, according to October 2023 ministry data, the province has 1,587 independent schools. That’s 66 percent growth over the decade. In fact, 48 more independent schools were listed in October than in September of 2023—3 percent growth in the number of independent schools in one month.

School start-ups are burgeoning with different types of schools, with different curricula focus or different delivery format (a combination of at-home and at-school being especially prevalent).

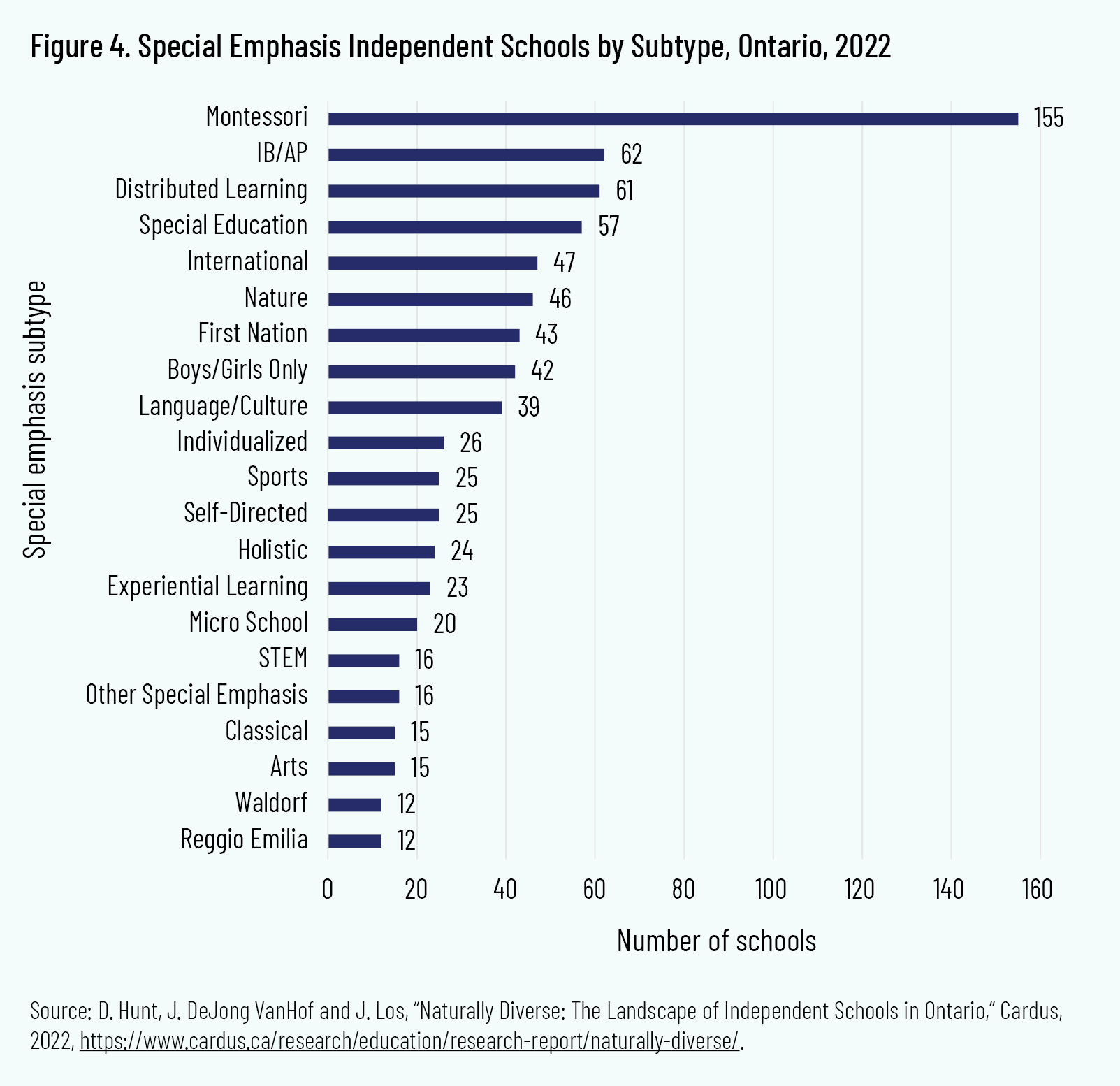

Ontario

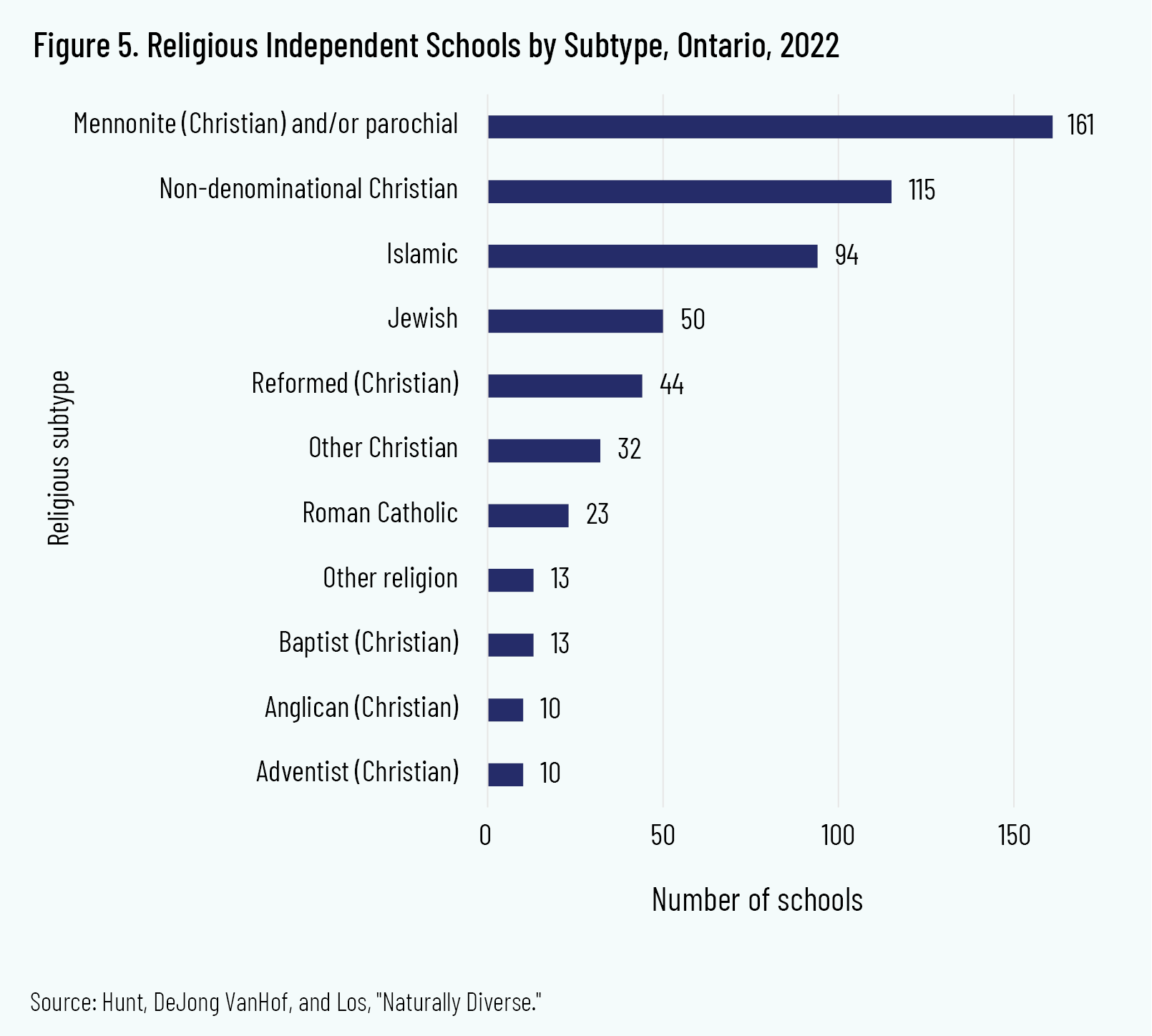

Cardus’s recent study “Naturally Diverse: The Landscape of Independent Schools in Ontario” provides a snapshot of the increasing diversity in school types within Ontario. 14 14 D. Hunt, J. DeJong VanHof, and J. Los, “Naturally Diverse: The Landscape of Independent Schools in Ontario,” Cardus, 2022, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/research-report/naturally-diverse/. It found that 39 percent are religious schools and another 41 percent are special-emphasis schools (having a distinct educational philosophy, curriculum, or pedagogy). In fact, there are almost two dozen different types just within the special-emphasis category. The largest group here are Montessori schools, at 155. Other types include special education, nature schools, First Nations, and classical schools, with significant growth in the art, sports, and science- and tech-focused schools over the last decade.

The “Naturally Diverse” study in Ontario showed a consistent increase in the number and size of Islamic and Jewish schools, alongside Christian counterparts. In total, more than one hundred religious schools have opened in Ontario in the last decade, and enrolment in religious schools was up by 24 percent between 2013–2014 and 2019–2020.

Alberta

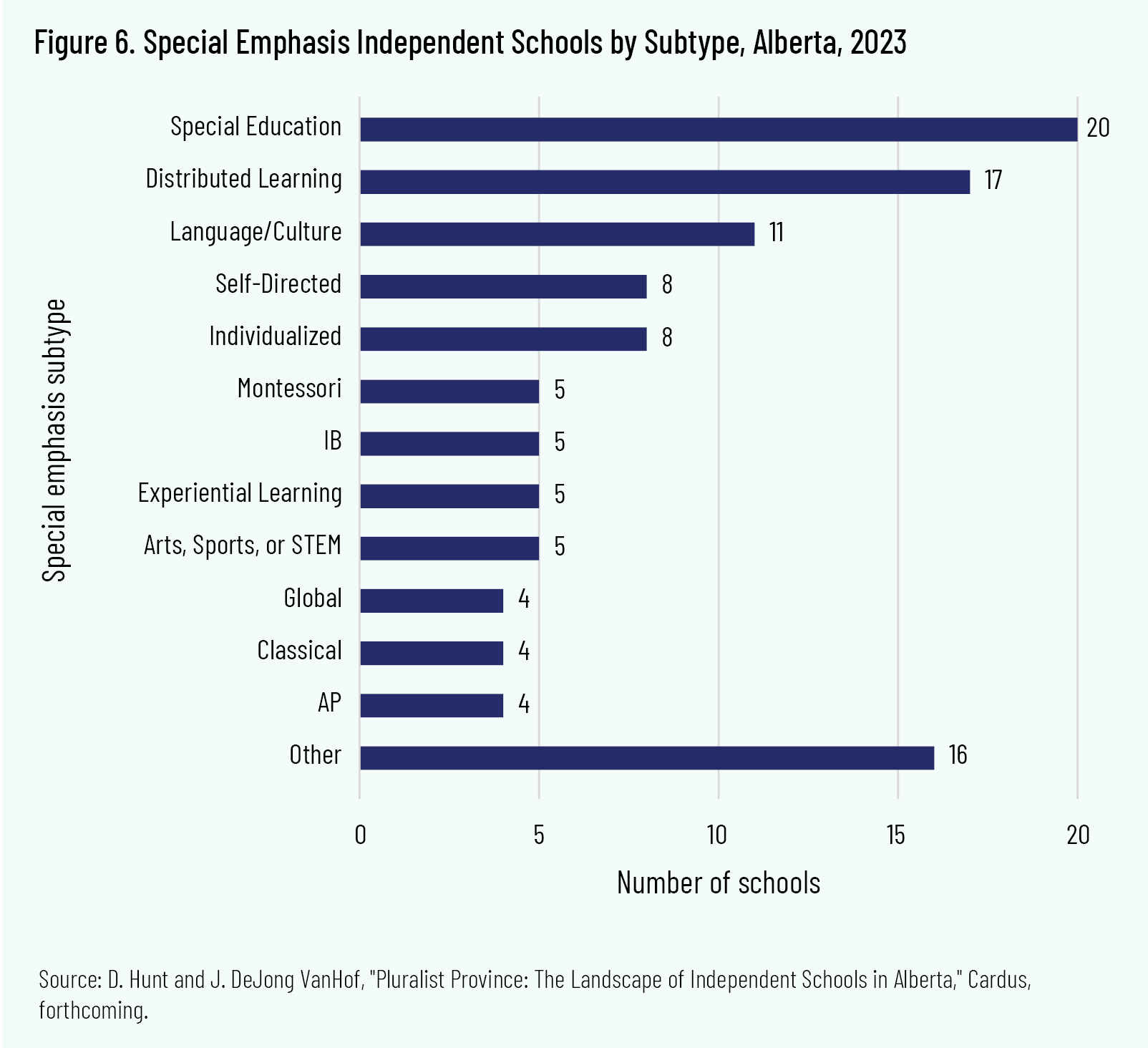

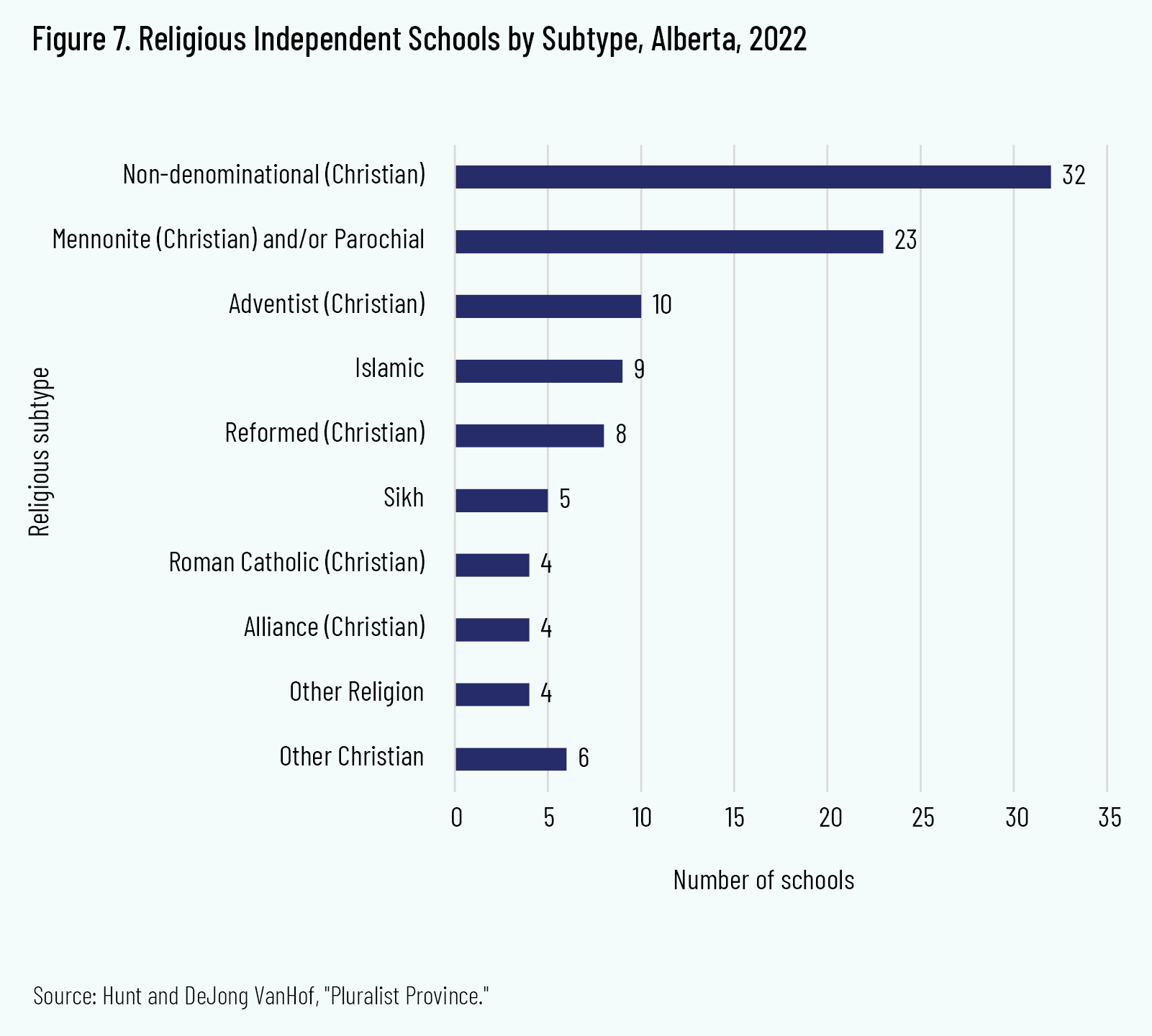

Cardus has since applied the same analysis to Alberta’s independent-school sector, and pre-publication results show a similar pattern—an extraordinary amount of diversity in school type. 15 15 D. Hunt and DeJong VanHof, “Pluralist Province.

Alberta’s overall independent-school sector is much smaller than Ontario’s, so the diversity here is perhaps all the more remarkable. The largest category of special-emphasis schools is those serving students with special needs, followed by distributed-learning schools and schools focused on language and culture. There has been significant growth in schools that have a mixed emphasis—say, both a religious focus and a special approach to curriculum and pedagogy. Data from Alberta reflects similar religious diversity as Ontario, with enrolments in religious schools seeing tenfold growth.

Another fascinating aspect of our time are the new kinds of schools starting, many with different conceptions of how education should be done. We caught a glimpse of the diversity through the conversations with William, Marcus, and Allison that I shared earlier: learning pods (small groups of students or families who hire a teacher for some or all subjects), hybrid schools, and microschools. Did we even hear of these five years ago? These start-ups set our time apart from others.

Hybrid Schools

The rise in hybrid schools across the US and Canada is noteworthy. Hybrid schools combine homeschooling and traditional schooling, with educators typically overseeing the curriculum but forging a strong partnership with parents. Students attend class in-school two or three days a week. Scholars at the University of Kennesaw in Georgia have begun the National Hybrid Schools Project, a yearly survey of American hybrid schools. In 2023, more than one hundred schools responded, yielding some interesting results, including evidence of strong growth. 16 16 For a visual depiction of the average enrolment in hybrid schools from 2018–2022, see figure 5 in E. Wearne and J. Thompson, “National Hybrid Schools Survey 2023,” National Hybrid Schools Project, Kennesaw State University, May 2023, https://www.kennesaw.edu/coles/centers/education-economics-center/docs/2023-hssurvey-report.pdf.

Interestingly, the majority of hybrid schools classify themselves as private religious schools, followed by identification as private non-religious schools. Students within these schools report with equal frequency that they are either homeschool students or students enrolled in a school, highlighting the hybrid character of these schools. These survey results represent a small sampling of hybrid schools, which are located in almost every state in the US.

Microschools

Microschools are small, multi-family schools in which learning progress is tailored to each student’s needs. Researchers at EdChoice, an American education think tank, estimate that there were up to 2.2 million children in the US microschooling full-time in 2022–2023. 17 17 M. McShane and P. Diperna, “Just How Many Kids Attend Microschools?,” EdChoice, September 12, 2022, https://www.edchoice.org/engage/just-how-many-kids-attend-microschools/. Similarly, the National Microschooling Center in the US provides a recent (April 2023) analysis of more than one hundred current microschools across thirty-four US states, as well as of one hundred prospective microschool leaders. The findings suggest that these schools are increasing in the ethnic diversity of the microschool leaders and of leaders planning to open microschools. Currently, about one in five of the surveyed prospective founders is Black and one in twenty is Latino. 18 18 For a visual depiction of the racial/ethnic makeup of microschool counders, see National Microschooling Center, “American Microschools: A Sector Analysis,” April 2023, 3, https://microschoolingcenter.org/american-microschools.

Survey results also showed that 70 percent of microschool founders are certified teachers who are interested in the opportunity to emphasize specialized, new, and alternative learning philosophies, and half of the microschools offer unique, specialized approaches to teaching and learning.

Also interesting to note is that just over a third register as private schools, while almost 45 percent are organized as learning centres serving homeschooled students.

While we don’t have comparable data for Canada, the US trends are illustrative of the types of changes that can be seen in the sector in North America.

Research and Policy

More researchers, more think tanks, and more institutes are focusing their work on education alternatives. There was a time not many decades ago when it was almost unheard of for a credible academic researcher to study aspects of education that didn’t involve or apply directly to public schools. It no longer raises eyebrows if a top education scholar studies something other than aspects of public schooling.

Studies, research, and funding for research on aspects of independent schools and educational choice now abound. Some universities, including the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas (a recent recipient of $20 million in funding for this purpose), stand out for significant scholarly contributions to aspects of school choice. The impact of their graduates is being felt across the world.

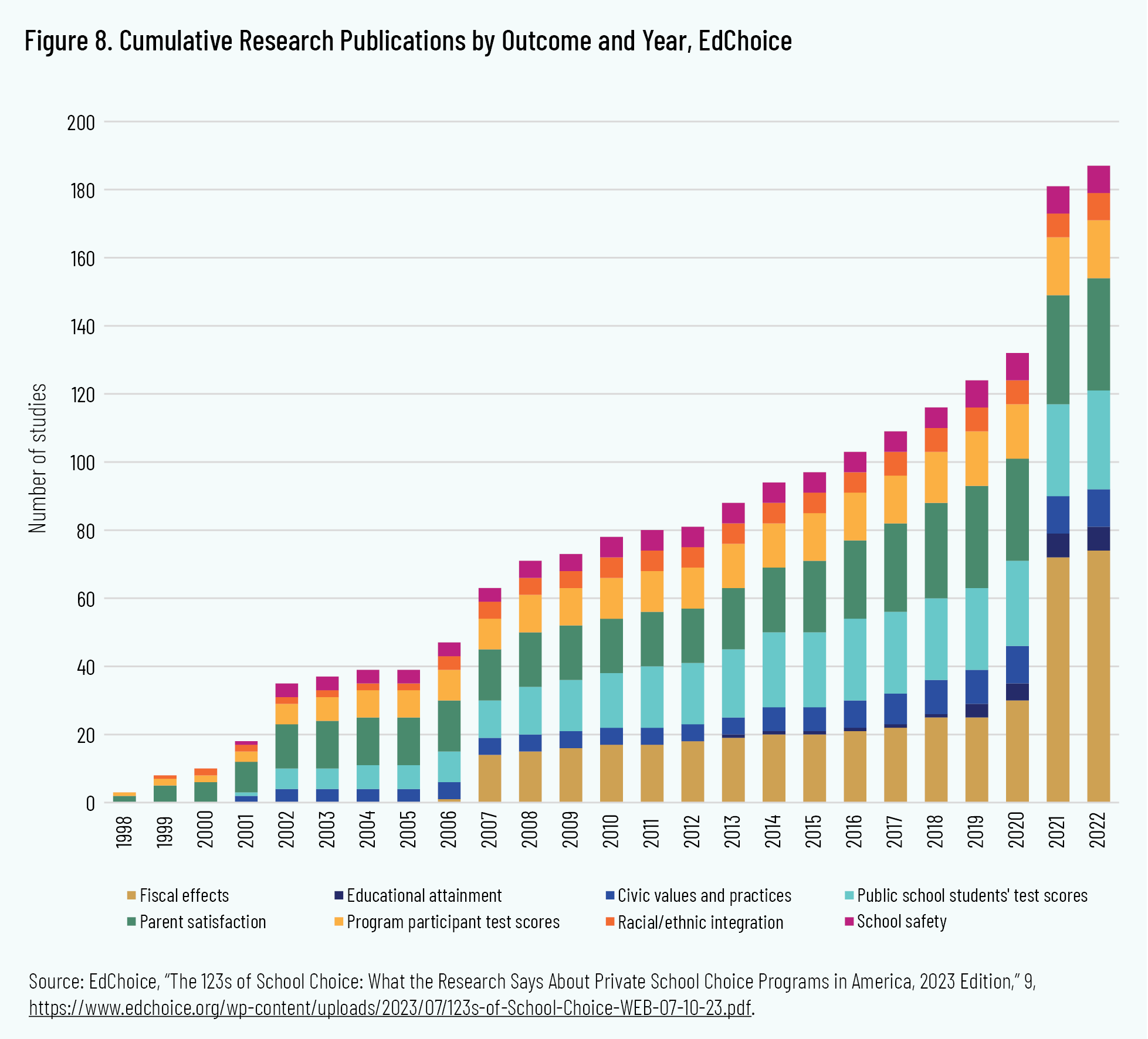

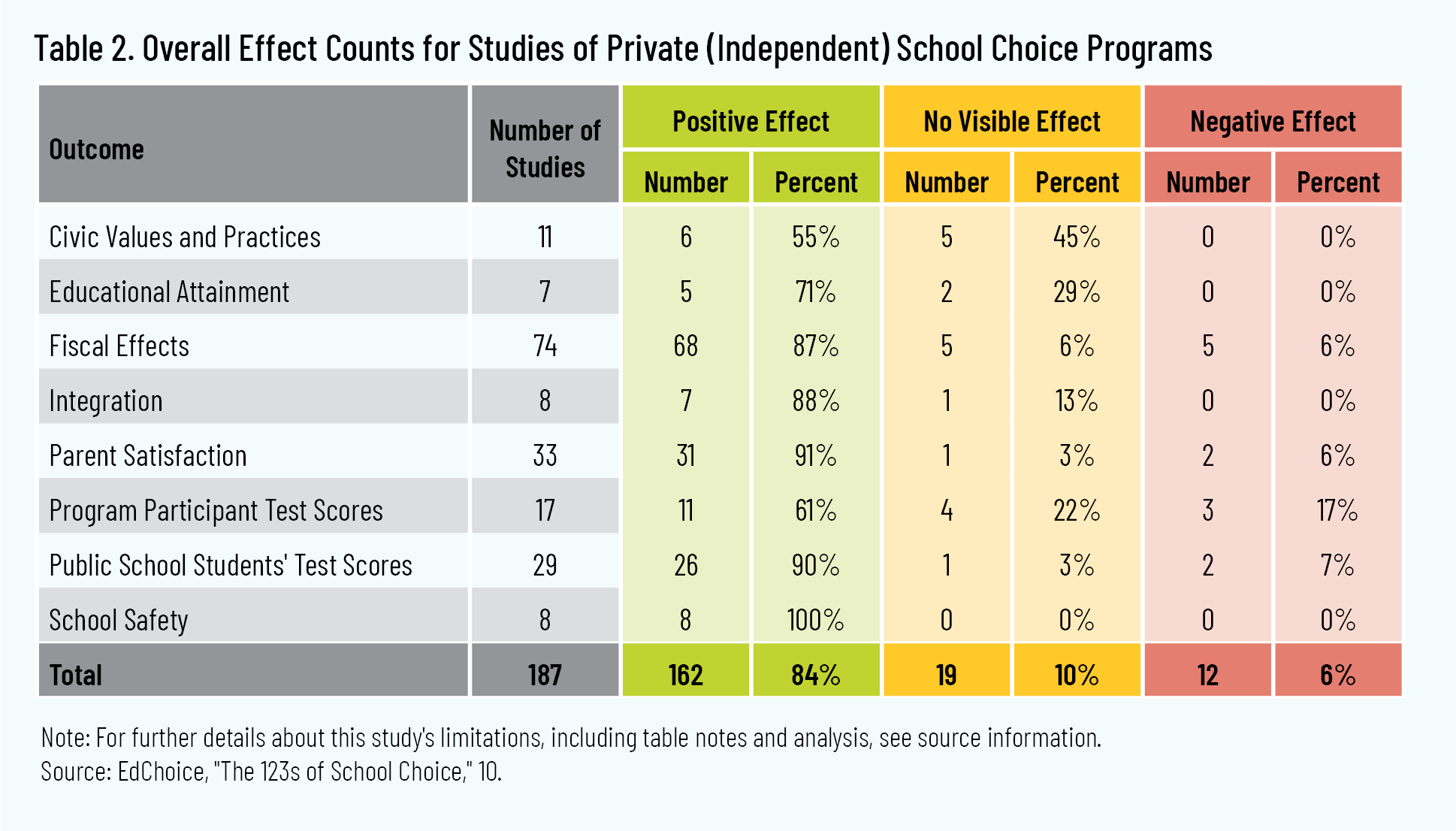

Leading think tanks and institutes across the US and several in Canada have whole departments focusing on education reform. Taken altogether, the impact is significant, and their presence is noted. One roundup of studies by EdChoice found that, as of March 2023, at least 187 studies were conducted on the impact of school choice. 19 19 EdChoice, “The 123s of School Choice: What the Research Says About Private School Choice Programs in America, 2023 edition,” https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/123s-of-School-Choice-WEB-07-10-23.pdf. As you might expect, the vast majority of studies (84 percent) have found positive effects of school-choice programs: better academic attainment, increased satisfaction, positive fiscal effects, and enhanced school safety.

Government and Regulatory Changes

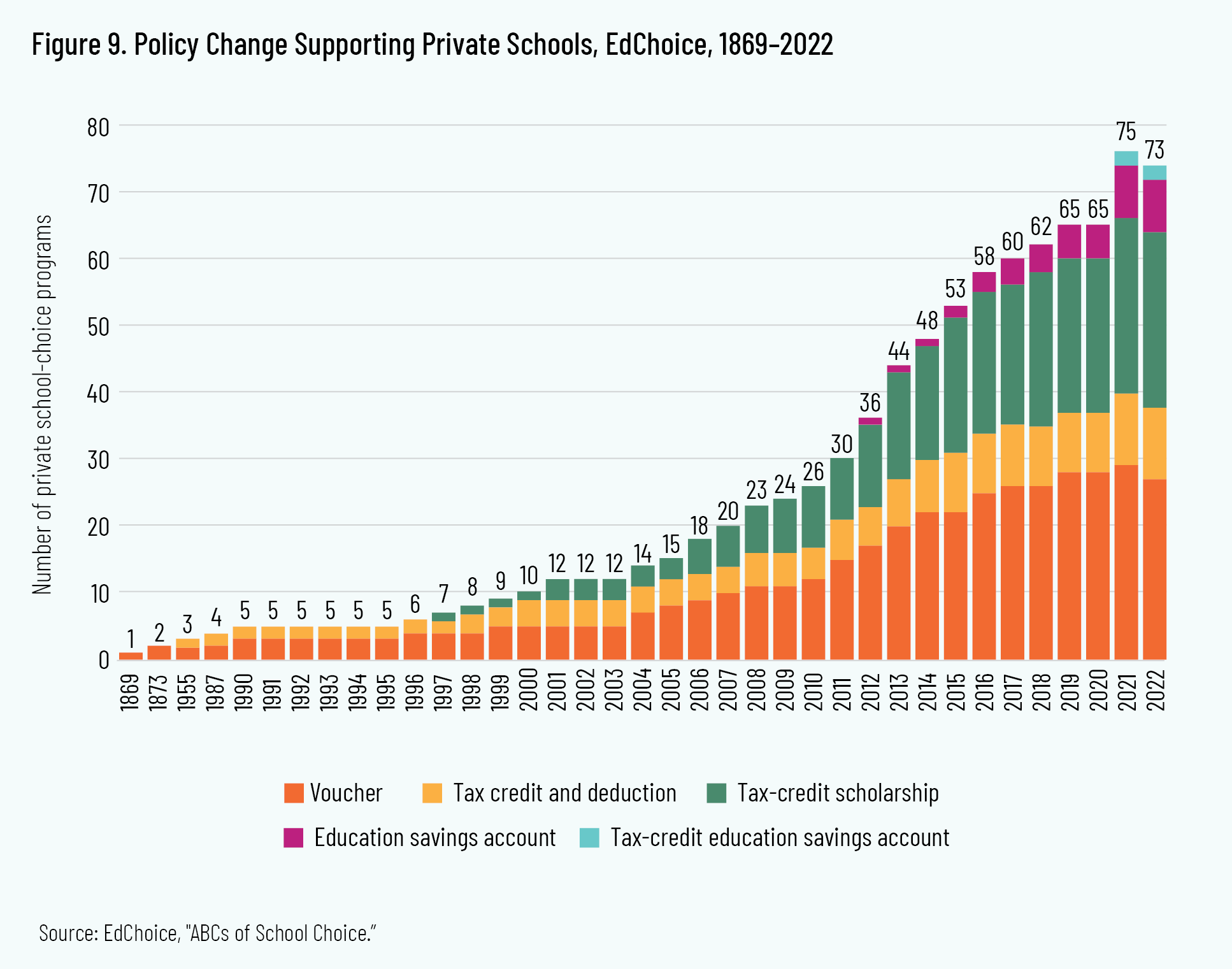

In the last several years, particularly in the US, the regulatory changes opening up school choice to more students and providers has been nothing short of dramatic. For example, a vast number of recent statutory and policy changes are getting baked into the regulatory DNA of the US. Many of these involve new funding approaches, and favour more forms of education than those designed and delivered by the government.

In 2021 and 2022 alone, we saw almost 150 new policies enacting government financial support of school choice. 20 20 EdChoice, “The ABCs of School Choice, 2023 Edition,” 7, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2023-ABCs-WEB.pdf. These included education savings accounts, vouchers, tax-credit education savings accounts, tax-credit scholarships, and other tax credits and tax deductions. More than 60 percent of US states now financially support school choice.

Foundations and Philanthropy

Another trend is in the work of foundations and philanthropists. The rise of foundations making significant contributions to education offered outside the public system is notable. Take the Herzog Foundation in Missouri, for example, which opened in 2020 with several hundred million dollars to invest in Christian education. 21 21 Herzog Foundation, “About Us,” 2023, https://herzogfoundation.com/about/. Or the VELA Education Fund, with millions of dollars per year being given in grants to catalyze “a diverse ecosystem of out-of-system providers.” 22 22 la Education Fund, “Grant Programs,” https://velaedfund.org/grants/. EdChoice is the decades-old Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice that produces research, training, and advocacy with significant reach and impact. Many more foundations, including family foundations, are aware of the importance of education and are directing increasing amounts of funds to contribute to the work in the sector.

Business Attention

More business leaders are paying attention, as they experience major challenges in attracting the right talent at the right time. Business innovation needs education innovation. Furthermore, the skill sets that businesses are now seeking in their employees are formed in K–12 settings. Businesses are paying attention and are starting to look outside government-provided education for solutions to their talent needs.

Trends Inside the Fortress

Let’s return to the fortress. The news has been bleak recently.

Learning Loss

We know that the pandemic was a system-changing event. K–12 students have paid a steep price. Poor data collection during the pandemic makes learning loss difficult to quantify. 23 23 A. Birioukov, “Absent on Absenteeism: Academic Silence on Student Absenteeism in Canadian Education,” Canadian Journal of Education 44, no. 3 (fall 2021), https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/cje/1900-v1-n1-cje06491/1082839ar.pdf. Yet a recent Fraser Institute report (September 2023) was able to look at two provinces, Ontario and Nova Scotia, finding that in both, math scores have declined significantly across most grades with provincewide tests between 2018–2019 and 2021–2022. In Ontario, grade 9 students’ performance declined by 23 percentage points in three years. Only 52 percent of students met expectations in 2021–2022, compared to 75 percent just three years earlier. 24 24 P. MacPherson and K.P. Green, “The Forgotten Demographic: Assessing the Possible Benefits and Serious Cost of COVID-19 School Closures on Canadian Children,” Fraser Institute, 2023, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/covid-19-essay8-forgotten-demographic-benefits-and-cost-of-school-closures.pdf/.

Declining Achievement

Pandemic learning loss is actually not just a recent trend in an overall picture. Derek Allison has looked at Canadian students’ performance on the internationally standardized test PISA (Program for International Student Assessment). His findings are not encouraging. Overall, since the first years of participating in international testing in the early 2000s, Canadian student performance has been in steady decline in the areas of reading, math, and science. 25 25 Allison, “What International Tests (PISA) Tell Us About Education in Canada,” Fraser Institute, September 7, 2022, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/what-international-tests-PISA-tell-us-about-education-in-canada.pdf. These findings are corroborated by the Ontario Human Rights Commission’s “Right to Read” report. About one in four students in grade 3 and nearly one in five students in grade 6 are failing to meet provincial reading standards. 26 26 tario Human Rights Commission, “Right to Read: Public Inquiry into Human Rights Issues Affecting Students with Disabilities,” Government of Ontario, February 2022, https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/right-to-read-inquiry-report.

Increasing Absenteeism

Absenteeism is increasing. The Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table reported a sixfold increase in severe absenteeism during the pandemic. 27 27 Gallagher-Mackay et al., “COVID-19 and Education Disruption in Ontario: Emerging Evidence on Impacts,” Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, June 2021, 13–14, https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.34.1.0. Both the US and the UK report increases in chronic and severe absenteeism of students; the UK’s Centre for Social Justice found a 137 percent increase in severe absenteeism between 2020 and 2022. 28 28 McPherson and Green, “The Forgotten Demographic,” 11. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University found a 25 percent increase in chronically absent students during the first year of the pandemic. 29 29 McPherson and Green, “The Forgotten Demographic,” 11.

Growing Violence

Violence in schools appears to be increasing. In May 2023, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario published results of a survey on school violence. 30 30 Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario, 2023 EFTO all-member violence survey results, May 2023, https://www.etfo.ca/news-publications/publications/etfo-violence-survey-results. Nearly 25,000 educators responded. Eighty percent said that the number of violent incidents had increased, and 66 percent said that the severity of violent incidents was worse than when they first started teaching. Eighty-seven percent thought that violence had a negative impact on their teaching and working, and more than one in three said that they had participated in a classroom evacuation due to a violent incident during the 2022–2023 school year.

Teacher Retention

It is increasingly difficult for schools to retain teachers. US data by McKinsey & Company show that 64 percent of educators who left teaching in 2022 did so voluntarily—an increase of almost 10 percent over four years. 31 31 J. Bryant, S. Ram, D. Scott, and C. Williams, “K–12 Teachers Are Quitting. What Would Make Them Stay?,” McKinsey & Company, March 2023, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/k-12-teachers-are-quitting-what-would-make-them-stay/. Recent news reports in Canada have decried the shortage of teachers across the country. 32 32 CBC News, “Quebec Schools Lacking Support Staff, Union Warns: Shortage Affects Secretaries, Special Education Technicians, Out of School Staff,” August 28, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-education-staff-shortage-1.6949232; S. Previl, “Canada’s Teachers Say Ongoing Shortage Creating ‘Crisis.’ What’s Behind It?,” Global News, September 5, 2023, https://globalnews.ca/news/9940451/canada-teacher-shortage/. Teacher burnout and mental health and well-being of educators are real challenges and may be some of the reason that we see these shortages.

Mental Well-Being

The social isolation of the pandemic has had a severe impact on students. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health analyzed recent survey responses of more than two thousand students in grades 7–12, from thirty-one participating school boards. 33 33 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, “The Well-Being of Ontario Students: Findings from the 2021 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey,” 2021, https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdf---osduhs/2021-osduhs-report-pdf.pdf. It found that almost three of every five students said that the pandemic had made them feel depressed about the future. More than a third said that the pandemic had a negative impact on their mental health. The statistics on loneliness and self-harm were startling. Indeed, almost one in five students reported that they had seriously contemplated suicide in the past year. This is a devastating reality, with real consequences for educators and the classroom.

Dominant Ideologies

Headlines have also begun to reveal the contours of an ideological focus that is increasingly of deep concern to parent communities, especially communities of faith. Hostility toward Muslim students abstaining from participation in Pride events, 34 34 T. Hopper, “‘You Don’t Belong Here’: Canadian Teacher Lambastes Muslim Student for Eschewing Pride,” National Post, June 7, 2023, https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/you-dont-belong-here-canadian-teacher-lambastes-muslim-student-for-eschewing-pride. wide divides in opinion on sex-education curriculum, 35 35 Q. Amundson, “Parental Rights March Returning as Gender Ideology Conflict Expands,” B.C. Catholic, October 13, 2023, https://bccatholic.ca/news/canada/parental-rights-march-returning-as-gender-ideology-conflict-expands; A. Carter, “Thousands Gather in GTA for Protests over Gender, Sexual Identity in School Curriculum, 1 Arrested,” CBC News, September 20, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/gta-sexual-education-protests-1.6972566; K. Molina, “Revised Sex-Ed Curriculum Gets Mixed Reviews from Parents,” CBC News, August 21, 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/mixed-reaction-ontario-sex-ed-curriculum-1.5254757. and the co-opting of school-board meetings for the expression of politicized viewpoints have disintegrated the public’s trust in the institution.

Book Removals

It is perplexing when this disintegration of trust is not recognized for what it is, but instead is doubled down on. The recent removal of all books published before 2008 from school libraries in the Peel District School Board is a bewildering response to government directives. 36 36 C. Alfonso, “Peel District School Board Faces Backlash for Removing Books Published Before 2008 from Its Libraries,” Globe and Mail, September 13, 2023, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-peel-school-board-libraries-removing-books/. It suggests that these ideologies are, for some, deeply entrenched, and students will pay the price through a narrow vision of history and literature.

What is the result of all of this? Taken together, learning loss, local and international achievement declines, absentee increases, prevalence of violence, teacher departures, decline in student mental well-being, prevalence of narrow ideologies, and rise in book removals show a fortress in disarray.

Implications

If the trends to more and different education happening outside of the fortress are indeed an established fact, we can draw at least one significant conclusion. Considering all the evidence, we can only conclude that we are leaving an era of educational uniformity and entering an era of education plurality. This plurality is evident through a diversity of providers, of approaches, of learners, of funders.

Pluralism, by definition, does not prioritize or prize one version of education over another. Rather, all are expected to be excellent spaces. What is key is that a variety of secular, philosophical, and religious schools can all contribute to the common good, to flourishing students, and to healthy civic formation.

You might join others in contesting me, though, by claiming that it is not pluralism but tribalism that we are witnessing. “Everyone,” you might say to me, “is searching for their own people, for their own way. And surely this division cannot be healthy.” Yet leading scholars of education pluralism Ashley Berner, Charles L. Glenn, and Jan de Groof argue that education plurality is well suited for a polarized time. According to Berner, there are several core ideas inherent to educational pluralism: 37 37 A. Berner, “Why ‘School Choice’ Is a Strange Term: America’s Schools in International Context,” Johns Hopkins University, May 20, 2020, YouTube video, https://youtu.be/iS4Ytm1rc5o?si=YqbSB0O6bKSNpLdf.

- It is impossible for education to be morally neutral. Therefore, the state has a duty to fund a plurality of options for a diverse citizenry.

- Education belongs to the realm of the individual (but it should not be totally privatized) and to the realm of the state (yet it is impossible for a uniform system to meet the needs of each of its citizens). Thus civil society—consisting of those voluntary institutions that are core to a healthy democracy—plays an important role in ensuring the quality and delivery of education.

- Educational pluralism insists on funding equity, as flexible and responsive to the needs of its constituents as possible.

- Educational pluralism insists on quality: education is a common good in which neighbours care about the civic outcomes of schooling for one another’s children and thus includes accountability for structures for education.

- This civic responsibility includes strong curricula and healthy school culture, both of which are key to student success.

Thus, pluralism allows for moral difference, encourages civil society to play a role in education, and insists on equity and quality. The core of what can hold diverse communities together in pluralism, and thus avoid balkanization, is agreed-on broad curriculum standards, a shared understanding of which core concepts are necessary to know.

Pluralism in its most complete form is not just the presence of diverse approaches or the tolerance of diverse approaches. It is a system of education in which the government funds and regulates, but does not deliver, all education options. Indeed, in pluralism, perhaps there is no fortress. There are no insiders and no outsiders.

Conclusion

Let’s summarize and conclude. I’ve held various roles in education since I earned my bachelor of education at the University of Toronto thirty-five years ago, and I have never seen such real and material level of interest in educational choices. In all my years of education-choice research and advocacy, I have never seen this kind of growth, diversity, and momentum. This moment in education has no parallel in our recent history. And so, if there ever was a time to work together toward accelerating education reform, now is it.

I also sense that this moment cannot be ignored. The momentum cannot be left to dwindle, the embers to die out into the darkness of more despair, hopelessness, violence, or boredom within the declining monolith that public schooling has become for many students, teachers, and families.

I still recall Melissa’s email to me early this year, asking me to meet with a group of parents feeling an urgent need to start a new school, so urgent in fact that we all drove through an ice storm to meet. “We need a Christian high school for kids in our region,” Melissa told me. “And we’ve needed one here for years. Now is the time. We’ll take eighteen months to open our doors. We’re close to securing a location.” “Do you think we can thrive,” the group asked, “if we especially focus on having a strong co-op program and place special emphasis on getting students prepared for real-world participation?” The energy in the room was palpable.

I am also thinking about a group of parents I met with six years ago. “Our children are not flourishing where they are. We need to do something differently.” Courageously, cautiously, and with tireless determination, they opened their independent school with eighteen students in 2018. “We’re at 160 students now,” my friend Grant recently shared with me, “and with students on our wait list, we now need a site, a place to call our home.”

And I am thinking of the crying need of refugees and recent immigrants, of the parents flocking to a new school start-up in Manitoba that opened its doors a few years ago with eight children of refugees and that is now, with a wait list, dedicatedly educating nearly two hundred newcomers to Canada.

So, what can we do? What ought we to do? May I propose three actions?

Give

First, build into the movement through your finances. Find the organizations best positioned to support the movement and the sector overall. Find the foundations best at leveraging funds, that can best move funds to where they are needed most and will be put to best use at this moment. I see three places where funding will make a significant difference in the immediate term:

- Tuition relief for families who deeply, even desperately, desire to choose an independent school, perhaps a Christian school, for their children right now, but who find the tuition, or even only some of it, too much of a barrier.

- Facilities funding for existing schools that are at capacity and have wait lists, so they can get new spaces designed, built, and opened to new students as soon as possible.

- School start-up support, so that the hundreds of groups across Canada that want to open the doors of a new school, a new hybrid school, or a microschool, even by 2024, can get off the ground and opened up.

So, build into the movement overall, by contributing financially to a foundation that is in touch with the needs and opportunities on the ground and has the mechanisms in place to efficiently, responsibly, and fairly distribute the funds where they are needed and will have the most impact. The Christian School Foundation has my vote in this regard.

Participate

Second, build into societal vibrancy, by participating in education locally. When a society’s education sector is vibrant, all of society benefits.

When many citizens create vibrancy in the education space, wrestling with good ideas and approaches and co-delivery arrangements, that is a societal good. Let’s get involved in establishing and supporting various manifestations of education excellence. The vibrancy and vitality of local educational communities pursuing different pedagogical or philosophical approaches—experts and ordinary citizens linking arms together—create attraction. Such nodes of meaning and purpose are vitalizing, energizing, new places for the safe welcome and education of our children and grandchildren.

And if you are a person of faith, I ask you to consider with some urgency this question of contributing locally to the vibrancy of a new or existing school. By this I’m getting at the following question: Might vibrant, faith-based schools take this opportunity to welcome our communities into faith-based spaces? Traditional religious institutions are increasingly inaccessible to an increasingly secular world. Might your vibrant, local, independent, faith-based school become the portal for children of our time to begin flourishing as whole persons, the flourishing that comes when the spiritual dimension of who they are as persons is recognized? In a time of increased immigration, we know that many people who arrive in Canada are people of faith. Let’s be places of welcome to the religiously committed, a place for newcomers to become established and offer their beauty and vibrancy to our schools, communities, and country.

Your local involvement in educational innovation creates community vibrancy. And more than that, it offers life to children who would otherwise not have had such an offer.

Advocate

Third, we need to become ignited in protecting and advocating for forms of education operating outside the fortress. After more than a decade of showing the economic and civic contributions of independent-school graduates to the public arena—and many of you are well acquainted with the Cardus Education Survey findings on the academic, spiritual, and civic outcomes of independent schools—it’s now time that the discriminatory regulatory barriers against our sector be removed. It is time that governments and policy-makers recognized that we are entering an era of education plurality. We need equity in this era. The continuing discrimination against diversity in education providers and education design must end.

The discrimination is worse in some Canadian provinces than others, but all jurisdictions can continue to or start to remove barriers to the flourishing of diverse approaches to education. Our clear message to government and policy-makers needs to be: Offer clarity about standards, establish the accountability for all schools to meet them, and then give them the freedom to pursue these standards in their own way.

Fund boldly. Build vibrancy locally. Advocate provincially. You can be secure in knowing that any act you take will not be done in isolation. Your act will be one of many within this larger movement in our time. Taken together, all of your acts of funding, building, and advocating will have an impact.

Are you ready to join in and contribute to one of the most promising education moments in your lifetime? Let’s walk together in unlocking access to a promising future for our children, for our provinces, and for our country.

References

Alfonso, C. “Peel District School Board Faces Backlash for Removing Books Published Before 2008 from Its Libraries.” Globe and Mail, September 13, 2023. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-peel-school-board-libraries-removing-books/.

Allison, D. “What International Tests (PISA) Tell Us About Education in Canada.” Fraser Institute, September 7, 2022. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/what-international-tests-PISA-tell-us-about-education-in-canada.pdf.

Amundson, Q. “Parental rights march returning as gender ideology conflict expands.” B.C. Catholic, October 13, 2023. https://bccatholic.ca/news/canada/parental-rights-march-returning-as-gender-ideology-conflict-expands.

Berner, A. “Why ‘School Choice’ Is a Strange Term: America’s Schools in International Context.” Johns Hopkins University, May 20, 2020. YouTube video. https://youtu.be/iS4Ytm1rc5o?si=YqbSB0O6bKSNpLdf.

Bennett, P. The State of the System: A Reality Check on Canada’s Schools. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2020.

Birioukov, A. “Absent on Absenteeism: Academic Silence on Student Absenteeism in Canadian Education.” Canadian Journal of Education 44, no. 3 (fall 2021). https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/cje/1900-v1-n1-cje06491/1082839ar.pdf.

Bryant, J., S. Ram, D. Scott, and C. Williams. “K–12 Teachers Are Quitting. What Would Make Them Stay?” McKinsey & Company, March 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/k-12-teachers-are-quitting-what-would-make-them-stay/.

Carter, A. “Thousands Gather in GTA for Protests over Gender, Sexual Identity in School Curriculum, 1 Arrested.” CBC News, September 20, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/gta-sexual-education-protests-1.6972566.

CBC News. “Quebec Schools Lacking Support Staff, Union Warns: Shortage Affects Secretaries, Special Education Technicians, Out of School Staff.” August 28, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-education-staff-shortage-1.6949232.

Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. “The Well-Being of Ontario Students: Findings from the 2021 Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey.” 2021. https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdf—osduhs/2021-osduhs-report-pdf.pdf.

EdChoice. “The 123s of School Choice: What the Research Says About Private School Choice Programs in America, 2023 Edition.” https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/123s-of-School-Choice-WEB-07-10-23.pdf.

———. “The ABCs of School Choice, 2023 Edition.” https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2023-ABCs-WEB.pdf.

Edvance. 2023 Student enrolment comparisons. Proprietary data provided by the author.

Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario. 2023 EFTO all-member violence survey results. May 2023. https://www.etfo.ca/news-publications/publications/etfo-violence-survey-results.

Gallagher-Mackay, K., P. Srivastava, K. Underwood, E. Dhuey, L. McCready, K.B. Born, A. Maltsev, et al. “COVID-19 and Education Disruption in Ontario: Emerging Evidence on Impacts.” Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, June 2021. https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.34.1.0.

Herzog Foundation. “About Us.” 2023. https://herzogfoundation.com/about/.

Hopper, T. “‘You Don’t Belong Here’: Canadian Teacher Lambastes Muslim Student for Eschewing Pride.” National Post, June 7, 2023. https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/you-dont-belong-here-canadian-teacher-lambastes-muslim-student-for-eschewing-pride.

Hunt, D., and J. DeJong VanHof. “Pluralist Province: The Landscape of Independent Schools in Alberta.” Cardus, forthcoming.

Hunt, D., J. DeJong VanHof, and J. Los. “Naturally Diverse: The Landscape of Independent Schools in Ontario.” Cardus, 2022. https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/research-report/naturally-diverse.

Jamison, P., L. Meckler, P. Gordy, C. Ence Morse, and C. Alcantara. “Home Schooling’s Rise from Fringe to Fastest-Growing Form of Education.” Washington Post, October 31, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/interactive/2023/homeschooling-growth-data-by-district/.

MacPherson, P., and K.P Green. “Forgotten Demographic: Assessing the Possible Benefits and Serious Cost of COVID-19 School Closures on Canadian Children, 2023.” Fraser Institute, September 2023. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/covid-19-essay8-forgotten-demographic-benefits-and-cost-of-school-closures.pdf/.

Mason, C.M. An Essay Towards a Philosophy of Education: A Liberal Education for All. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner, 1925.

———. School Education. Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1989 [1907].

McShane, M., and P. Diperna. “Just How Many Kids Attend Microschools?” EdChoice, September 12, 2022. https://www.edchoice.org/engage/just-how-many-kids-attend-microschools/.

Molina, K. “Revised Sex-Ed Curriculum Gets Mixed Reviews from Parents.” CBC News, August 21, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/mixed-reaction-ontario-sex-ed-curriculum-1.5254757.

National Microschooling Center. “American Microschools: A Sector Analysis.” April 2023. https://microschoolingcenter.org/american-microschools.

Ontario Human Rights Commission. “Right to Read: Public Inquiry into Human Rights Issues Affecting Students with Disabilities.” Government of Ontario, February 2022. https://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/right-to-read-inquiry-report.

Polanyi, M. Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-critical Philosophy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

Previl, S. “Canada’s Teachers Say Ongoing Shortage Creating ‘Crisis.’ What’s Behind It?” Global News, September 5, 2023. https://globalnews.ca/news/9940451/canada-teacher-shortage/.

Smith, C. What Is a Person? Rethinking Humanity, Social Life, and the Moral Good from the Person Up. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Smith, J.K.A. Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2009.

Statistics Canada. “Table 37-10-0109-01. Number of Students in Elementary and Secondary Schools, by School Type and Program Type.” https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710010901.

Swaner, L., J. Eckert, E. Ellefsen, and M. Lee. “Future Ready: Innovative Missions and Models in Christian Education.” Colorado Springs: Association of Christian Schools International and Cardus, 2023.

Van Pelt, D., and J. Spencer. Students as Persons: Charlotte Mason on Personalism and Relational Liberal Education. Charlotte Mason Centenary Series. McKinney, TX: Charlotte Mason Institute, 2023.

Vela Education Fund. “Accelerating Education Innovation and Opportunity for Every Learner.” 2023. https://velaedfund.org/.

Wearne, E., and J. Thompson. “National Hybrid Schools Survey 2023.” National Hybrid Schools Project, Kennesaw State University, May 2023. https://www.kennesaw.edu/coles/centers/education-economics-center/docs/2023-hssurvey-report.pdf.