The 2018 Cardus Education Survey (CES) marks nearly a decade’s worth of research into the effects of various school sectors on the academic, social, religious, and civic development of graduates in the United States. The Survey is now considered one of the most significant measures of nongovernment school outcomes. CES reports capture the views from a representative sample of 1,500 randomly selected American high school graduates ages twenty-four to thirty-nine who were asked to complete a thirty-five to forty-five-minute survey. The assessment comes at an important time—far enough away for these graduates to have had experiences in other educational institutions, in family and relationships, and in the workplace, and yet close enough to allow for some maturity, reflection, and recollection. The CES instrument includes a large number of controls for many factors in graduate development, such as parental education, religion, and income, in order to isolate a school sector’s particular impact (“the schooling effect”).

1

1

The 2018 CES respondents include 904 graduates who primarily attended public high school, 83 respondents who primarily attended non-religious private school, 303 graduates of a Catholic high school, 136 graduates of an

evangelical Protestant school, and 124 who were homeschooled. In order to isolate the school effect for each of these sectors, the analysis includes a large number of control variables for basic demographics (gender, race and ethnicity, age, and region of residence), family structure (not living with each biological parent for at least sixteen years, parents divorced or separated, not growing up with two biological parents), parent variables (educational level of mother and father figure, whether parents pushed the respondent academically, the extent to which the respondent felt close to each parent figure), and the religious tradition of parents when the respondent was growing up (mother or father was Catholic, conservative Protestant, conservative or traditional Catholic). A control was also included for the number of years a private school graduate spent in public school. Despite our efforts to construct a plausible control group, because families who send their children to religious schools or non-religious independent schools make a choice, they may differ from those who do not exercise school choice in unobservable ways that are therefore not accounted for in our study. Despite this, the CES use of an extensive survey instrument, together with its comprehensive application of control variables and resulting patterns of outcomes, assures us with some confidence of the accuracy of our school sectoral outcomes.

Five smaller reports summarize the results of the 2018 survey. They focus on particular outcomes and themes of interest, including the following: (1) education and career pathways; (2) faith and spirituality; (3) civic, political, and community involvement and engagement; (4) social ties and relationships; and (5) perceptions of high school.

One of the important contributions of the 2018 CES is to report on how graduates from the various school sectors are participating in public life. The following report summarizes these findings into five categories: trust, political views and orientations, political engagement, civic views, and civic engagement and volunteerism. These findings provide significant nuance to our understanding of how graduates contribute to public life, citizenship, and the common good by offering a deeper understanding of how graduates from the various school sectors consider and balance obligations to their community and the nation. These measures also get at something beyond politics; they say something about how graduates live within a shared civil society and how they are involved in the life of their community, how they work toward the common good, and their capacity to love their neighbours.

Citizenship, volunteerism, and civic and political engagement is about building the social infrastructure of society; the middle layers between the state and the individual. These activities occur in public spaces where families worship and gather and children go to school, as well as the community centres and local youth shelters. These are the spaces where “civicness” is strengthened and thick community is built, where people come together regardless of their possible divisions and work toward something in common. The 2018 CES seeks to understand how the various school sectors influence these important civic virtues and orientations, and includes a number of questions on trust, political and civic orientation, civic engagement, and volunteerism.

Trust

The precipitous decline in trust is a recent and troubling trend in the United States. Richard Edelman, president and CEO of the Edelman firm, which conducts the international “Edelman Trust Barometer,” notes that the steep decline in trust was “happening at a time of prosperity, with the stock market and employment rates in the U.S. at record highs.” 2 2 Quoted in Uri Friedman. “Trust Is Collapsing in America,” The Atlantic, January 21, 2018, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/trust-trump-america-orld/550964/. This is unusual. Increased distrust usually follows calamities of foreign policy or economic recession. Nevertheless, today only one-third of Americans trust their government to do what is right, which is a 14 percent decline from last year. Only 42 percent trust the media, and the general trust in business and in NGOs has decreased by nearly 10 percentage points each. 3 3 Edelman Trust Barometer, 2018 Annual Global Survey. New York Times columnist David Brooks writes, “The pervasive atmosphere of distrust undermines actual intimacy, which involves progressive self-disclosure, vulnerability, emotional risk and spontaneous and unpredictable face-to-face conversations.” 4 4 David Brooks. “The Avalanche of Distrust.” The New York Times. September 13, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/13/opinion/the-avalanche-of-distrust.html The lack of trust is part of the path to social isolation, and the path of social isolation leads to ill health for individuals and societies.

The CES gauges social trust by asking a series of questions designed to understand graduates’ orientations to and perceptions of public institutions and persons, including the federal government, mass media, public school personnel, and scientists. Non-religious private school graduates have a higher degree of institutional trust in absolute terms than do public school graduates, but the explanation for this difference is rooted in family rather than in school processes. These graduates are more likely to trust the federal government, scientists, and the mass media than all other graduates. On the other end of the spectrum, religious homeschool graduates tend to trust the federal government the least.

The Catholic school effect on institutional trust is intriguing. Catholic school graduates do not differ from public school graduates in their level of trust in the federal government and their trust in the mass media is lower but not significantly lower than public school graduates. On the other hand, their trust in scientists is significantly higher than that of public school graduates.

The findings reveal that Protestant school graduates’ level of trust in the federal government is slightly lower than that of public school graduates, but this effect is not nearly significant, and is in fact higher than we have seen in past cohorts. At the same time, trust in the mass media remains low for Protestant school graduates: the average Protestant school graduate’s level of trust in mass media, measured on a six-point scale, is about .35 points lower than that of the average public school graduate. Protestant school graduates are substantially less likely to trust public school teachers or administrators, and also express a lower level of trust in scientists, though these views seem largely shaped by whether the scientist is secular. Interestingly, however, when asked if science and religion are mostly compatible, Protestant school graduates strongly agree, though there is a good deal of variation within the group.

Levels of institutional trust are lowest among religious homeschoolers. Even after family-background controls are added, religious homeschoolers are less trusting of the federal government, the mass media, public schools, and scientists. However, the religious homeschool sector is also most likely to agree with the view that science and religion are mostly compatible. The religious homeschool sector is also more supportive of the view that it is acceptable to say things in public that are offensive to religious groups. Their average level of support for this view is nearly a half point higher on this seven-point scale. In a similar vein, when asked if society should be more tolerant of non-Christian religions, the religious homeschool graduates are far less likely than their peers from public school to believe this. Protestant school graduates are also less likely to agree with this view than public school graduates.

Political Views and Orientations

When we consider views on the place of religion in public life, the evidence suggests that nearly all private-school-sector graduates have higher levels of support for religion in the public square. Even the non-religious private school graduates oppose the view that religion should be kept out of debates over social and political issues. Catholic school graduates have about the same levels of support for religion in public life as public school graduates. Protestant and religious homeschool graduates are the most supportive of an active role for religion in public life.

In terms of political ideology, protestant school graduates are much more likely than public school graduates to describe their political ideology as conservative and to report that they are closer to the Republican Party than the Democratic one. On a seven-point scale, they are about 1.25 points closer to the Republicans. They are also significantly less likely to say that the federal government should do more to solve social problems. Religious homeschool graduates follow suit for the most part; however, they are not as strongly in support of the Republican Party as the Protestant school graduates. Catholic school graduates trend toward political conservatism in ideology, but this is only marginally significant. They see themselves as closer to the Republican Party, though the Catholicschool-sector effect is less than half that of the Protestant-school-sector effect on this measure.

Protestant school graduates are no more or less likely than are public school graduates to have a sense of obligation to care for the environment. Non-religious private school graduates are slightly lower on a sense of obligation to care for the environment, and the Catholic school effect is similar to that of the public school, though it is only marginally significant.

Civic orientation also includes a sense of identity or belonging to the nation, which may conflict with other global or religious identities. In the CES data, we find strong school-sector differences regarding the sense of being a citizen of the world rather than a citizen of a particular country. Nonreligious private school graduates are much more likely than public school graduates to consider themselves as citizens of the world. Catholic school graduates are in line with public school graduates in their views on global citizenship. Protestant school graduates and religious homeschoolers tend to see themselves less as global citizens, though their high levels of involvement in mission and service work throughout the globe provides important nuance to this picture. Catholic school graduates are more willing than public school graduates to participate in international or foreign policy issues, whereas Protestant school graduates are nearly identical on this measure. Non-religious private school graduates are more likely to volunteer for an international cause, though this large effect—nearly 1.8 times the public-school-graduate odds—is only marginally significant. Religious homeschool graduates are strongly and significantly less likely to volunteer for international issues or causes— indeed, 70 percent less likely than are public school graduates.

Political Engagement

Civic researchers have pointed to the importance of expressed interest in politics as a measure of political engagement and a healthy democracy. On this outcome, non-religious private school graduates and Catholic school graduates are no different from public school graduates. Protestant school and religious homeschool graduates express lower levels of interest in politics and public affairs. The average on this four-point scale of political interest is about .3 points lower, which corresponds to a third.

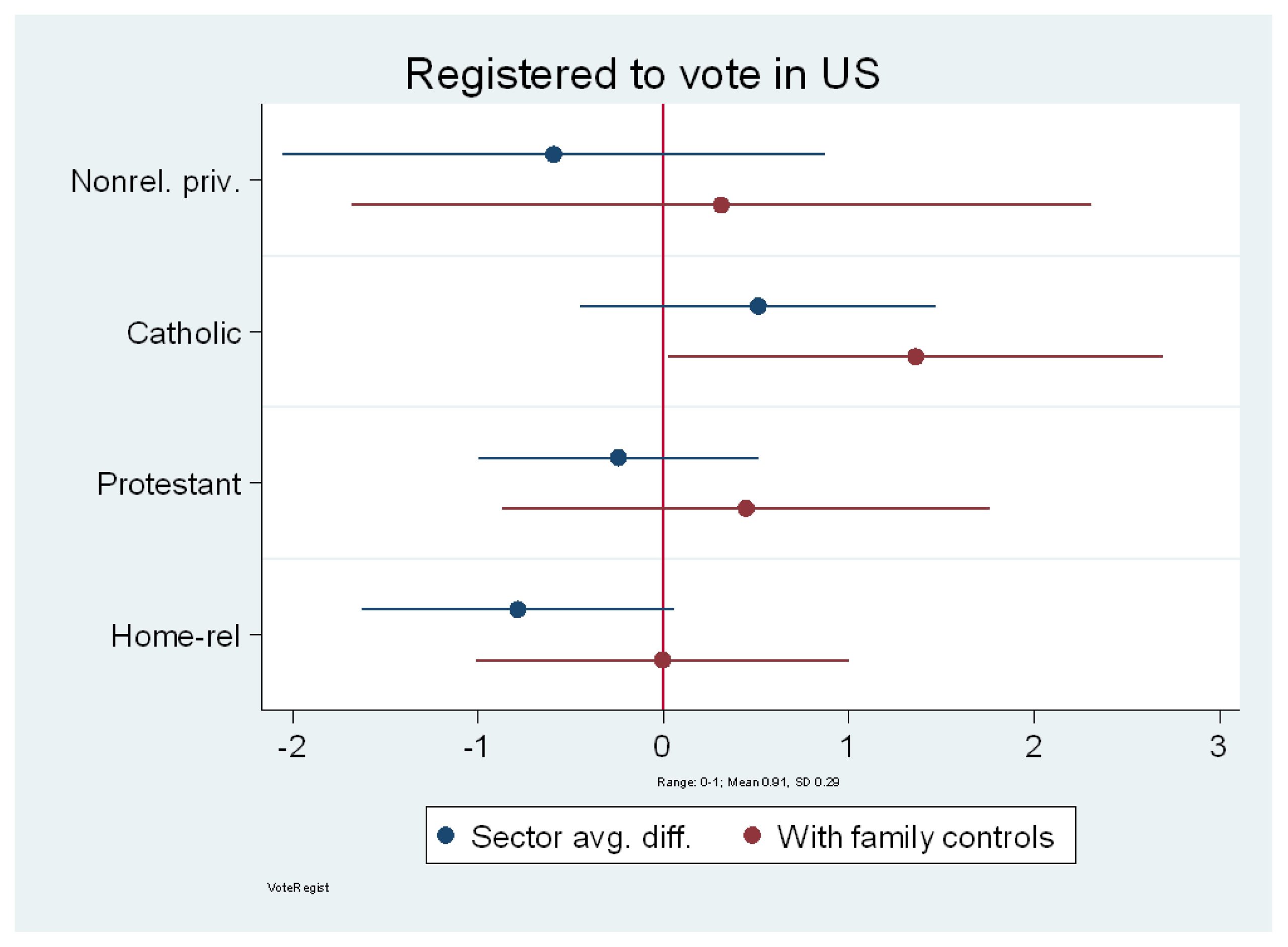

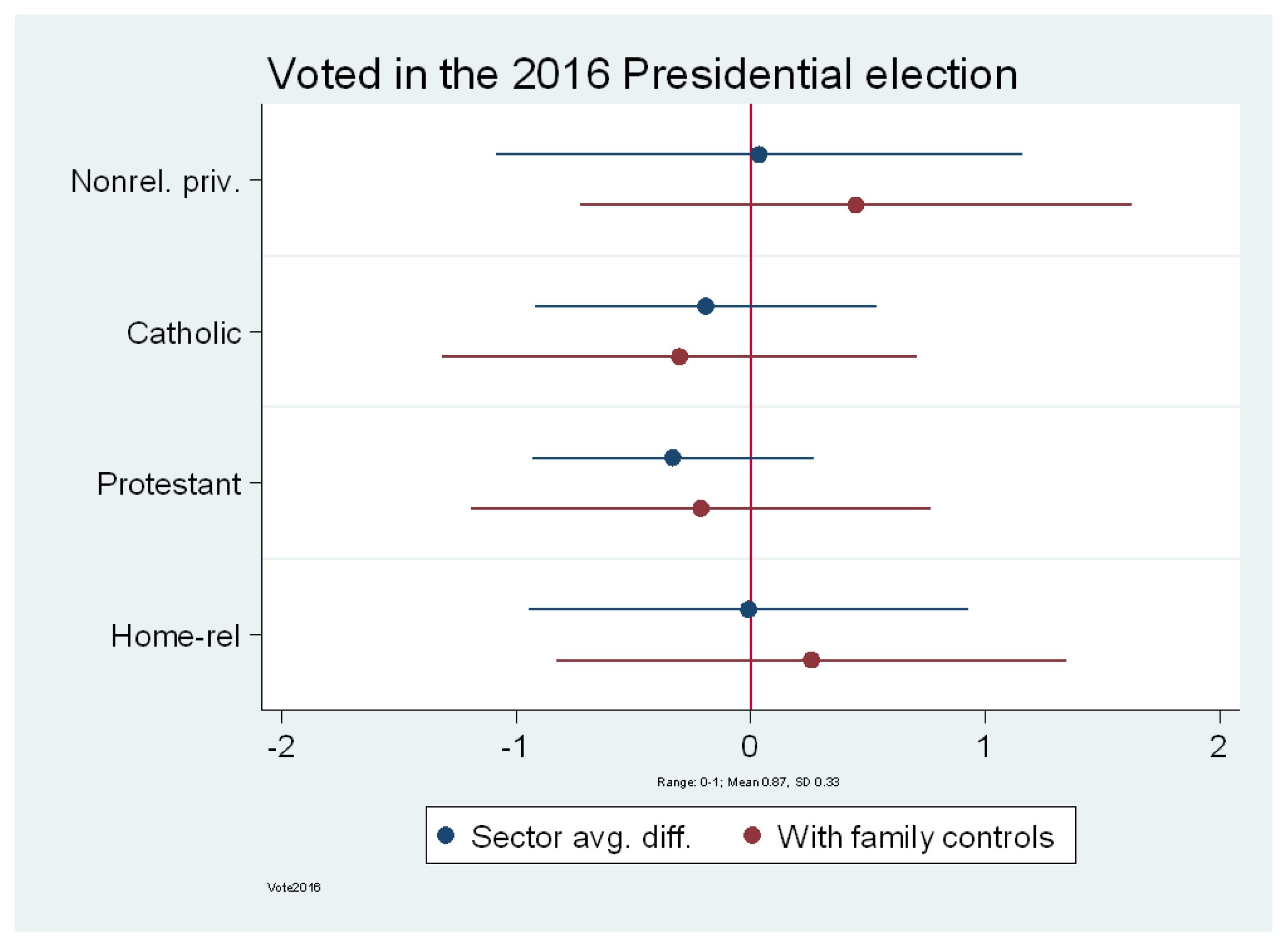

A useful indicator of positive civic attitude is voting behaviour because it demonstrates the willingness of an individual to become engaged. Interestingly, non-religious private school graduates are nearly split down the middle on this outcome. They are also no more or less likely than public school graduates to vote in presidential or local municipal elections. Catholic school graduates, though, are much more likely—indeed, four times more likely—to be registered to vote than are public school graduates. Protestant school graduates are no more or less likely to report being registered to vote than public school graduates and are no more or less likely to have voted in the last presidential election, though they are slightly less likely than public school graduates to vote in local elections. Religious homeschool graduates are less likely to be registered to vote in national elections and significantly less likely to vote in local elections than public school graduates.

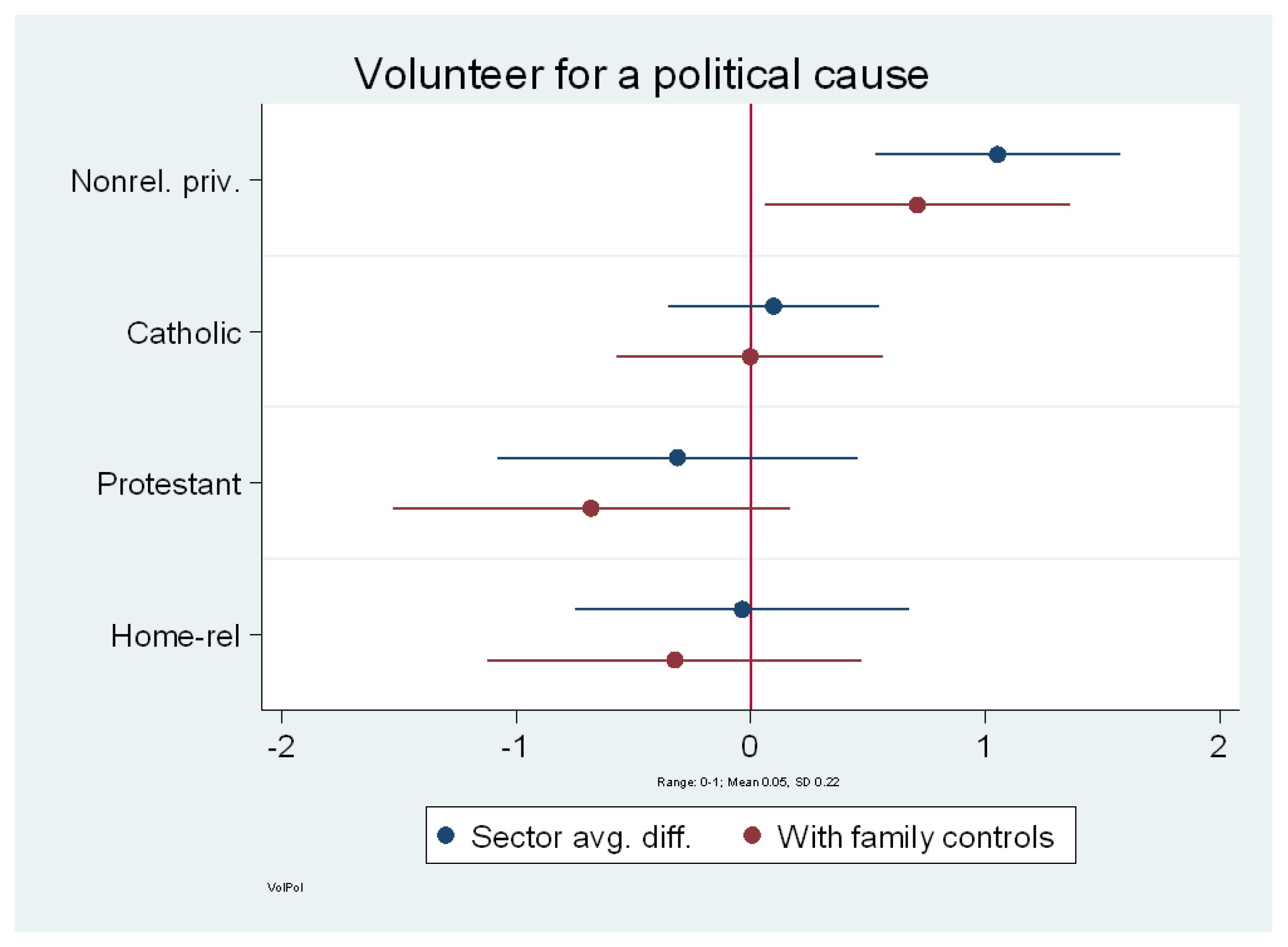

In terms of volunteering for a political cause or organization, non-religious private school graduates are over twice as likely to volunteer as public school graduates. Protestant school graduates are trending lower than public school graduates on the likelihood of volunteering for a political cause. No other school-sector differences emerge.

The level of donations made by graduates is not strongly related to school sector, with two possible exceptions. Catholic school graduates are more likely to make a political donation, though this is not significant after family background is accounted for. Protestant school graduates are significantly less likely to donate money to a political cause than a public school graduate. It is likely that Protestant graduates donate larger amounts of money or tithe to their local congregation.

Catholic school graduates are more likely to express their opinions about political and community affairs on the internet, but they are less likely to have participated in a protest or rally. Protestant school graduates, on the other hand, are equally as likely to have participated in a protest or demonstration and to have written a letter or email to a newspaper as public school graduates. But they are slightly less likely to have contacted a government official and to use the internet to express their opinions on politics and community affairs.

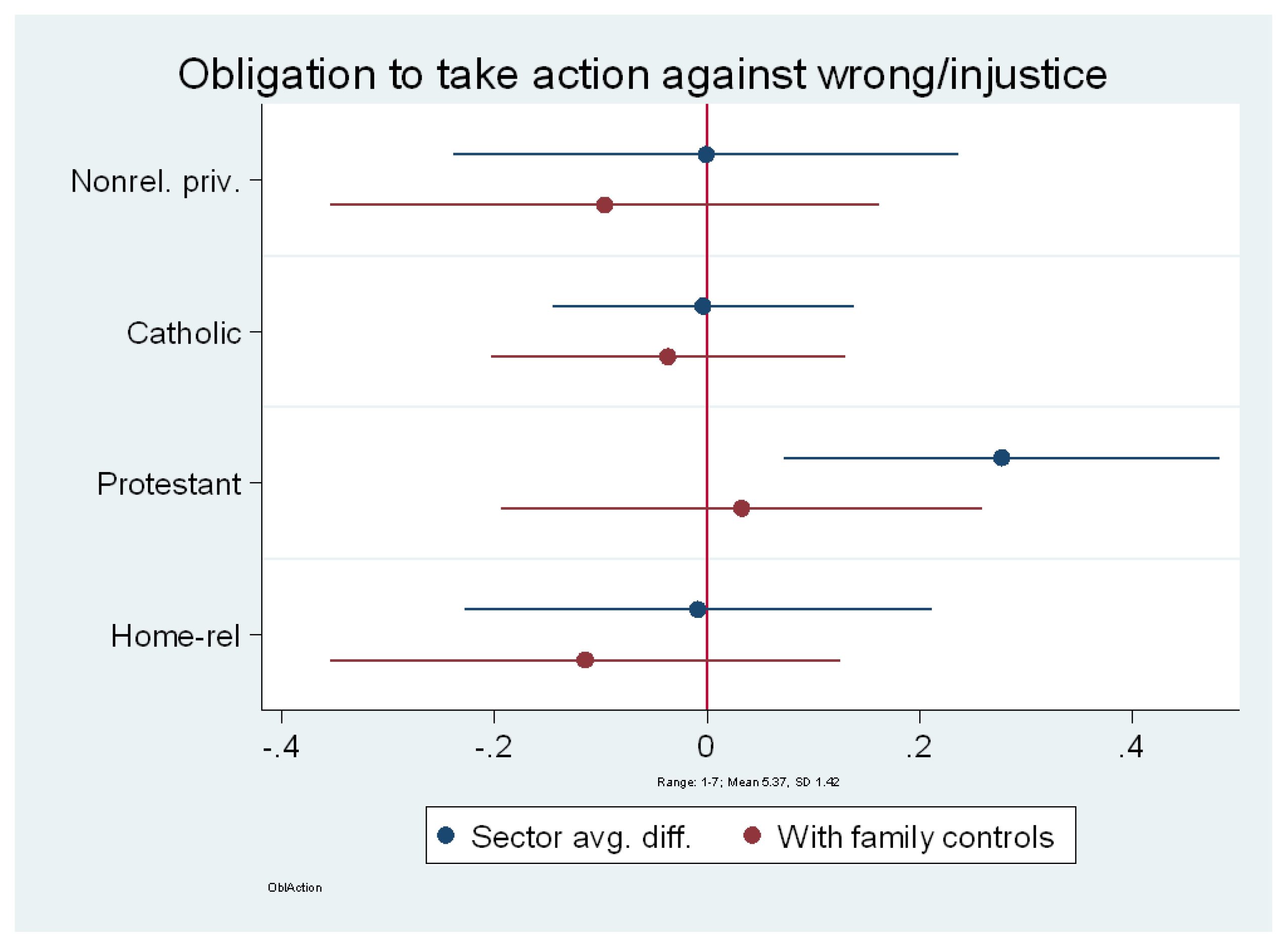

Religious homeschool graduates are also less likely than public school graduates to express their political opinions through the internet but equally likely to have contacted a public official than public school graduates. They are also less likely to feel obligated to participate in politics than public school graduates and are on average about .3 points lower on this seven-point scale.

In terms of the total number of political activities including protest behaviour, contacting a government official, and participation in political campaigns, non-religious private school graduates are slightly more engaged than public school graduates. Protestant school graduates are less engaged in absolute terms—about an average of .2 fewer activities on this five-point scale. When we look at both political activity and civic engagement in political affairs, we also find important religious school differences: Protestant school graduates and religious homeschool graduates are significantly lower than public school graduates on this eight-point scale, though the homeschool sectoral difference is not statistically significant. No other school-sector differences are statistically significant.

Civic Views and Orientations

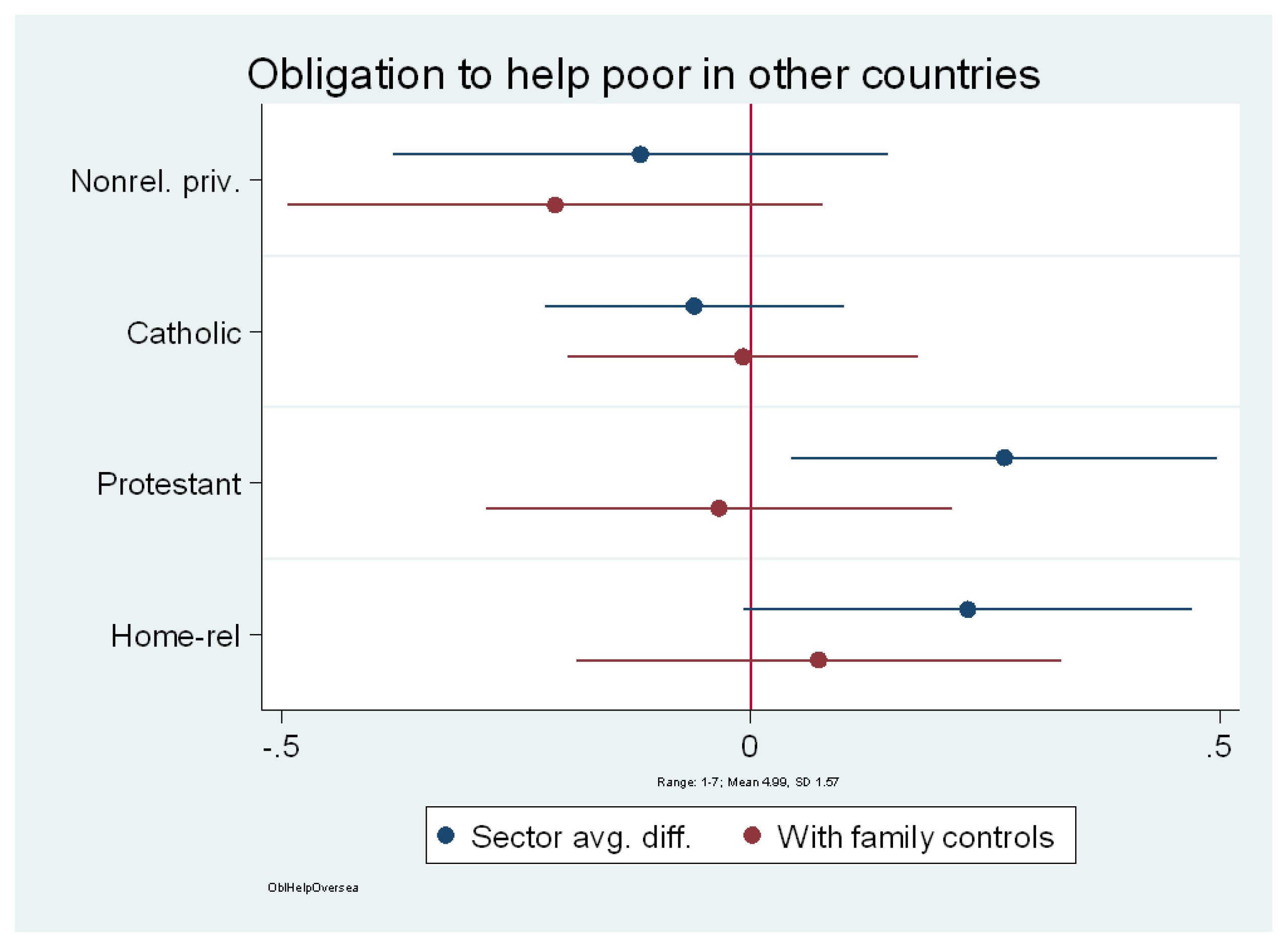

On several measures of public obligations, Protestant school graduates express a greater sense of obligation, though these levels are likely attributed to family background rather than the school sector. For example, Protestant school graduates express a high sense of obligation to participate in politics, but this is not statistically significant. These graduates also have a stronger sense of obligation to take action against wrongs or injustice in life, but this again is accounted for by family background. The Protestant school sector is also effective in cultivating in its graduates, a strong sense of obligation to help the poor in other countries. Fairly similar patterns are evident among religious homeschool graduates.

Non-religious private school graduates have a slightly stronger sense that they can have an impact on community and political affairs. In contrast, Catholic school graduates have a much higher sense of efficacy than public school graduates. This average is about .15 points higher on a five-point scale. This sense of efficacy in politics and community involvement is slightly lower for Protestant school graduates, though these graduates were just as likely as public school graduates to have taken a civics class. The other private-school-sector graduates are significantly less likely to report having taken a civics class in high school.

Civic Engagement, Volunteering, and Giving

The 2018 CES data collects data on civic engagement by looking at activities both within and outside of a congregational setting, recognizing that church activities are not separate from the public good and that activities in these spaces are also contributing to the good of society. Churches have for long been involved in different kinds of public ministries, including working with the poor, the elderly, the socially isolated, new immigrants, and those suffering from various forms of addictions. In this way, churches play a crucial role in contributing to the public good of society. The CES data is clear in highlighting some important nuances in terms of the differently lived norms and patterns of civic involvement depending on school sector.

Protestant and religious homeschool graduates are less likely to report that they volunteer for a neighbourhood or civic organization. Religious school graduates also report being involved in a lower average number of civic organizations. In contrast, Catholic school graduates report a higher number of civic organizations, but this is only marginally significant. But this picture changes quite drastically when we look at volunteering activity taking place within a religious congregation. Generally, Protestant school graduates are doing more in their congregations, though most of these findings are not attributable to the influence of the school (after controlling for family and demographic variables). Even when considering data on volunteering on a committee, as a leader, organizing activities, or other forms of congregational volunteering, Protestant school graduates are more likely to do at least one of these forms of volunteering than are public school graduates.

When we look at the number of volunteer hours occurring outside of a religious congregation, the results show that the school sectors do not significantly differ on this measure. Protestant school and home school graduates are not significantly different from public school graduates, and Catholic school graduates are, in fact, significantly higher than public school graduates on this measure. However, when graduates were asked to estimate how many non-congregational organizations they volunteered for, it is clear that non-religious private school and Catholic school graduates participate in a greater number of organizations than do public school and Protestants school graduates.

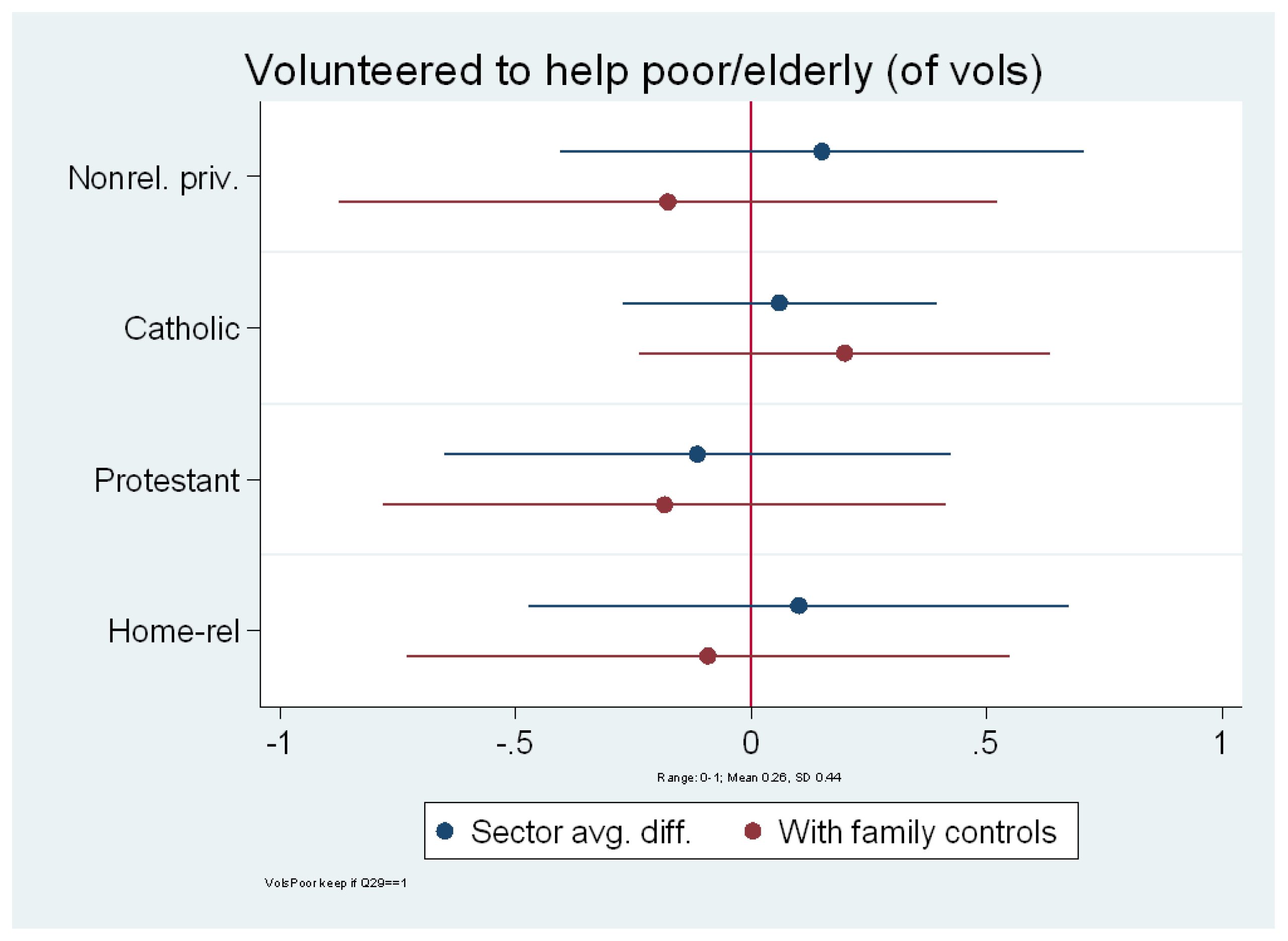

A number of school-sector differences and volunteering patterns emerge when we look more closely at the nature of these volunteering efforts. Non-religious private and Catholic school graduates are more likely to volunteer in health-care organizations. Catholic school graduates are somewhat more likely to volunteer in schools and youth programs, and also more likely to volunteer to help the poor and elderly than public school graduates. Religious homeschool graduates are somewhat less likely to participate in school volunteering, though this difference is only marginally significant. And nonreligious private school graduates are more likely to volunteer for arts and cultural organizations, and to volunteer for a political or an international cause than public school graduates.

Volunteering in a neighbourhood and civic organization is less likely among Protestant and religious homeschool graduates. Indeed, when we look at volunteering patterns outside of a congregational setting, some school-sector differences become apparent. Non-religious private and Catholic school graduates tend to favour health-care causes and organizations. Non-religious private school graduates tend to focus on arts and cultural, political, or international organizations or causes.

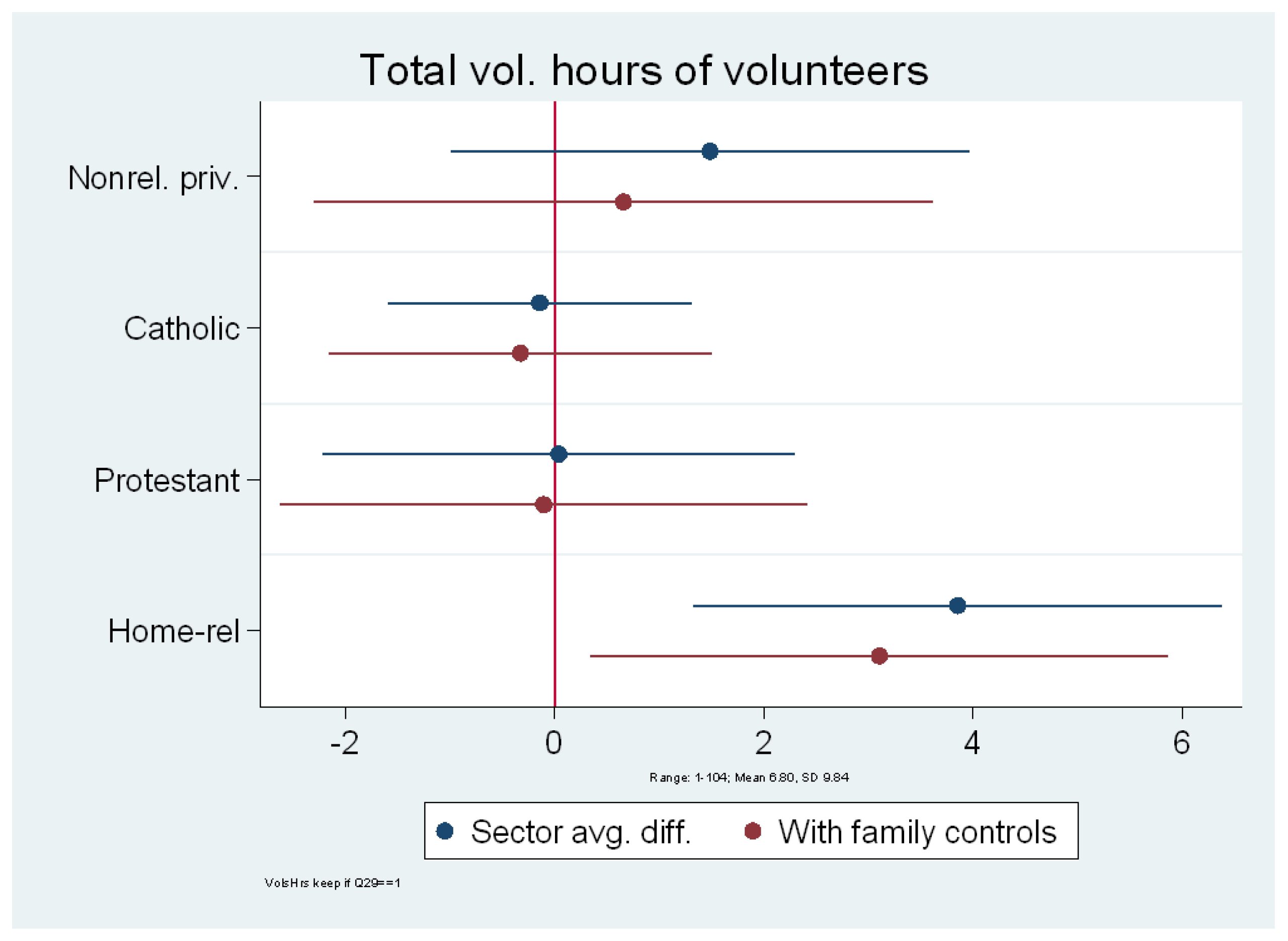

Interestingly, when we consider the total number of volunteer hours, adding together the congregational volunteering and non-congregational volunteering, we find no statistically significant difference on this measure between the sectors, once family controls are applied. When we consider the proportion of hours that are over the median on this measure, about forty-eight percent of public school graduates are above the median on this measure while fifty-seven percent of Catholic school graduates are above the median number of hours. Interestingly, before family controls are applied, Protestant school graduates are well above the public school graduates on this measure: about fifty-six percent of Protestant school graduates are above the median number of total volunteer hours. After family background controls are added, however, the estimate for Protestant schoolers is forty-nine percent, which means these graduates are just as likely to dedicate more than the median number of volunteer hours as the public school graduate.

Mission and Social Service Trips

Less traditional forms of volunteering and community service, such as mission and social service trips, tend to favour the religious school graduates. The likelihood of going on a mission or socialservice trip is much higher among Protestant school graduates, and somewhat higher among Catholic school graduates than public school graduates. Religious homeschool graduates were also more likely, but this is accounted for by demographic and family background variables.

While Protestant school graduates were much more likely to take a mission or social-service trip in elementary or secondary school, they are more likely to take a trip as an adult as well. Considering the entire sample, we do find that the Protestant school sector is the only sector significantly different from the public school sector in the likelihood of taking at least one trip that involved relief and development activities. They are also the only sector to significantly differ from public school graduates in the likelihood of taking at least one trip outside of the United States and Canada, and are more likely to take at least one trip during college than public school graduates. Non-religious private school graduates are marginally more likely to take a mission or social-service trip during college.

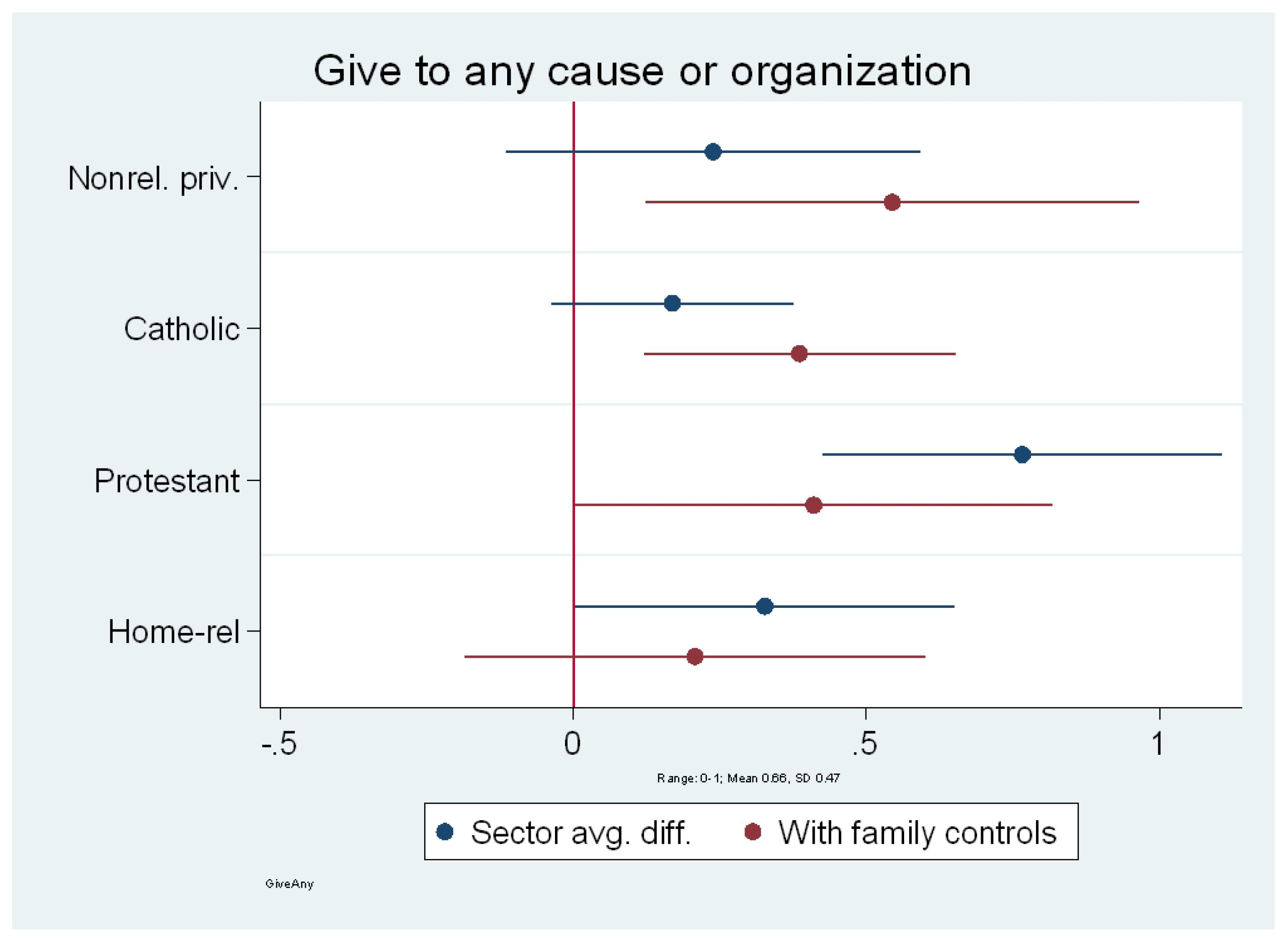

Donations

School sector is associated with the type of organizations and causes that are supported by Americans. All of the private school sectors are more likely to yield graduates who donate money or goods to some cause or organization than the public school sector, with the protestant sector being particularly high when we consider donations to “any cause or organization.” As would be expected, the likelihood of donating to a religious congregation is higher among all religious school graduates, especially among Protestant school and religious homeschool graduates. Religious school graduates are also more likely than public school graduates to donate money or goods to other types of religious organizations or causes as well. Interestingly, Catholic school graduates are slightly more likely to give to secular organizations and causes and to political causes than are public school graduates. The likelihood of giving for disaster relief is somewhat lower among Protestant school graduates as compared to public school graduates.

Conclusion

The story of the 2018 CES findings requires some nuance, but a number of patterns emerge in relation to trust, as well as political and civic engagement, when we analyze outcomes across the various school sectors. In terms of trust, we see that Protestant and religious homeschool graduates express lower levels of trust in politicians and the media. This may have important implications for how these groups engage both civically and politically and provides an important finding that is worthy of further analysis in the future. Importantly, however, we see that these groups remain very much engaged—indeed, offering higher levels of volunteer hours than public school graduates— but these efforts are taking place in particular areas. Protestant school graduates are highly involved in giving and volunteering in and for religious congregations and organizations, but this doesn’t preclude other forms of volunteering and giving. Mission and social-service trips are a strong suit of Protestant-school-graduate engagement, and many of these trips involve relief and development activities.

The 2018 Cardus Education Survey collects data on civic engagement by looking at activities both within and outside of a congregational setting, recognizing that church activities are not separate from the public good and that churches play a crucial role in contributing to the public good of society. Our analysis of this data highlights some important nuances in terms of the differently lived norms and patterns of civic involvement depending on school sector. Overall, religious school graduates are very active in giving and volunteering in their young adulthood years. Catholic school graduates are the most consistently positive on giving and volunteering, showing a higher likelihood of volunteering outside the congregation and donating to charity, including secular and political causes. In addition, Catholic school graduates are somewhat more likely to participate in mission and social-service trips than are public school graduates, and these graduates tend to be involved in a wide variety and number of volunteer causes and organizations, including health care, poverty, and the elderly and youth. Non-religious private school graduates are more likely than public school graduates to donate to charity and volunteer in the areas of health care, arts and culture, and political and international causes and organizations.