The 2018 Cardus Education Survey (CES) marks nearly a decade’s worth of research into the effects of various school sectors on the academic, social, religious, and civic development of graduates in the United States. The Survey is now considered one of the most significant measures of nongovernment school outcomes. Cardus Education Survey reports capture the views from a representative sample of 1,500 randomly selected American high school graduates ages twenty-four to thirty-nine who were asked to complete a thirty-five- to forty-five-minute survey. The assessment comes at an important time—far enough away for these graduates to have had experiences in other educational institutions, in family and relationships, and in the workplace, and yet close enough to allow for some maturity, reflection, and recollection. The CES instrument includes a large number of controls for many factors in graduate development, such as parental education, religion, and income, in order to isolate a school sector’s particular impact (“the schooling effect”). 1 1 The 2018 CES respondents include 904 graduates who primarily attended public high schools, 83 respondents who primarily attended non-religious private schools, 303 graduates of a Catholic high school, 136 graduates of an evangelical Protestant school, and 124 who were homeschooled. In order to isolate the school effect for each of these sectors, the analysis includes a large number of control variables for basic demographics (gender, race and ethnicity, age and region of residence), family structure (not living with each biological parent for at least sixteen years, parents divorced or separated, not growing up with two biological parents), parent variables (educational level of mother and father figure, whether parents pushed the respondent academically, the extent to which the respondent felt close to each parent figure), and the religious tradition of parents when the respondent was growing up (mother or father was Catholic, conservative Protestant, conservative or traditional Catholic). A control was also included for the number of years a private school graduate spent in public school. Despite our efforts to construct a plausible control group, because families who send their children to religious schools or non-religious independent schools make a choice, they may differ from those who do not exercise school choice in unobservable ways that are therefore not accounted for in our study. Despite this, the CES use of an extensive survey instrument, together with its comprehensive application of control variables and resulting patterns of outcomes, assures us with a 90 percentile confidence interval for each coefficient of the accuracy of our school sectoral outcomes. Five smaller reports summarize the results of the 2018 survey.

They focus on particular outcomes and themes of interest, including the following: (1) education and career pathways; (2) faith and spirituality; (3) civic, political, and community involvement and engagement; (4) social ties and relationships; and (5) perceptions of high school.

One of the important contributions of the 2018 CES is to report on how graduates think about their experiences in high school, including an assessment of their high school’s quality and climate, the relationships they formed there, and how well they felt prepared for key dimensions of adulthood, including university, career, and personal relationships. Parents and graduates seem especially interested in understanding how graduates perceive their high school years, reflecting perhaps the concern with deeper aspects of happiness and well-being as an equally important dimension to academics of the high school years. These are often difficult and complicated years in the life of the student, sparking deep interest by parents and education researchers alike to better understand the connections between school culture and the wellbeing of students. For these reasons, the following measures of graduate perceptions form an important public barometer for the influence of the different school sectors.

Perceptions of High School

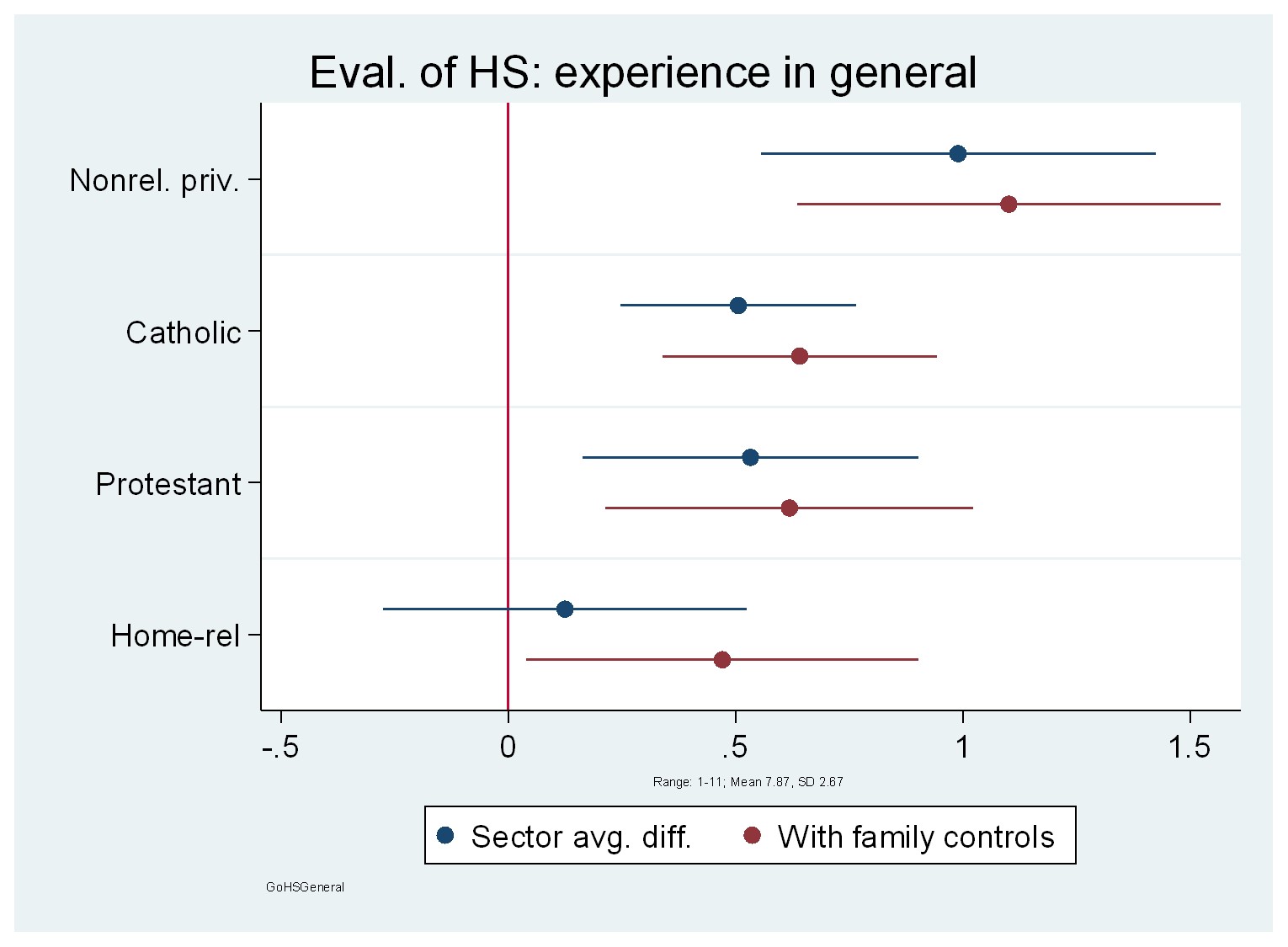

We begin with an overall assessment of the graduates’ experiences in high school. We have seen in every CES report that graduates of private school sectors consistently rank their high school experience more highly than do graduates of the public sector, based on a question that asks respondents to place how they felt about their “high school experience in general” on an elevenpoint scale, from very favourable to very unfavourable. The non-religious private school sector is about a full point higher on this measure—representing a large effect. Catholic and Protestant school graduates report a similarly high evaluation of their high school experiences. When we analyze the data to understand the percentage of students in each sector who rate their school as greater than the median score of eight on this measure, about forty-four percent of public school graduates are above this median, while sixty-four percent of non-religious private school graduates and roughly fifty-four percent of religious school graduates rate their high school experience very highly. While lower on this scale than Catholic and Protestant school graduates, the religious homeschool graduates provide a more positive general assessment of their high school experience than do public school graduates. Unlike most other measures included in the 2018 CES, each of the religious school sectors as well as the non-religious private school sector expressed higher views on this measure than do public school graduates. The 2018 CES survey also asks graduates whether they enjoyed their high school. Here again, while the sector differences are somewhat muted, still the private school sectors are significantly higher on this outcome relative to public school graduates. Religious homeschool graduates express equal levels of enjoyment to public school graduates.

When asked whether graduates were proud to have graduated from their high school, perhaps surprisingly, non-religious private school graduates expressed the same level of pride in their high school as did public school graduates. Catholic school graduates were on average prouder of their school than were public school graduates. Protestant school graduates’ level of pride varies considerably, but they remain on average higher on this measure than do public school graduates.

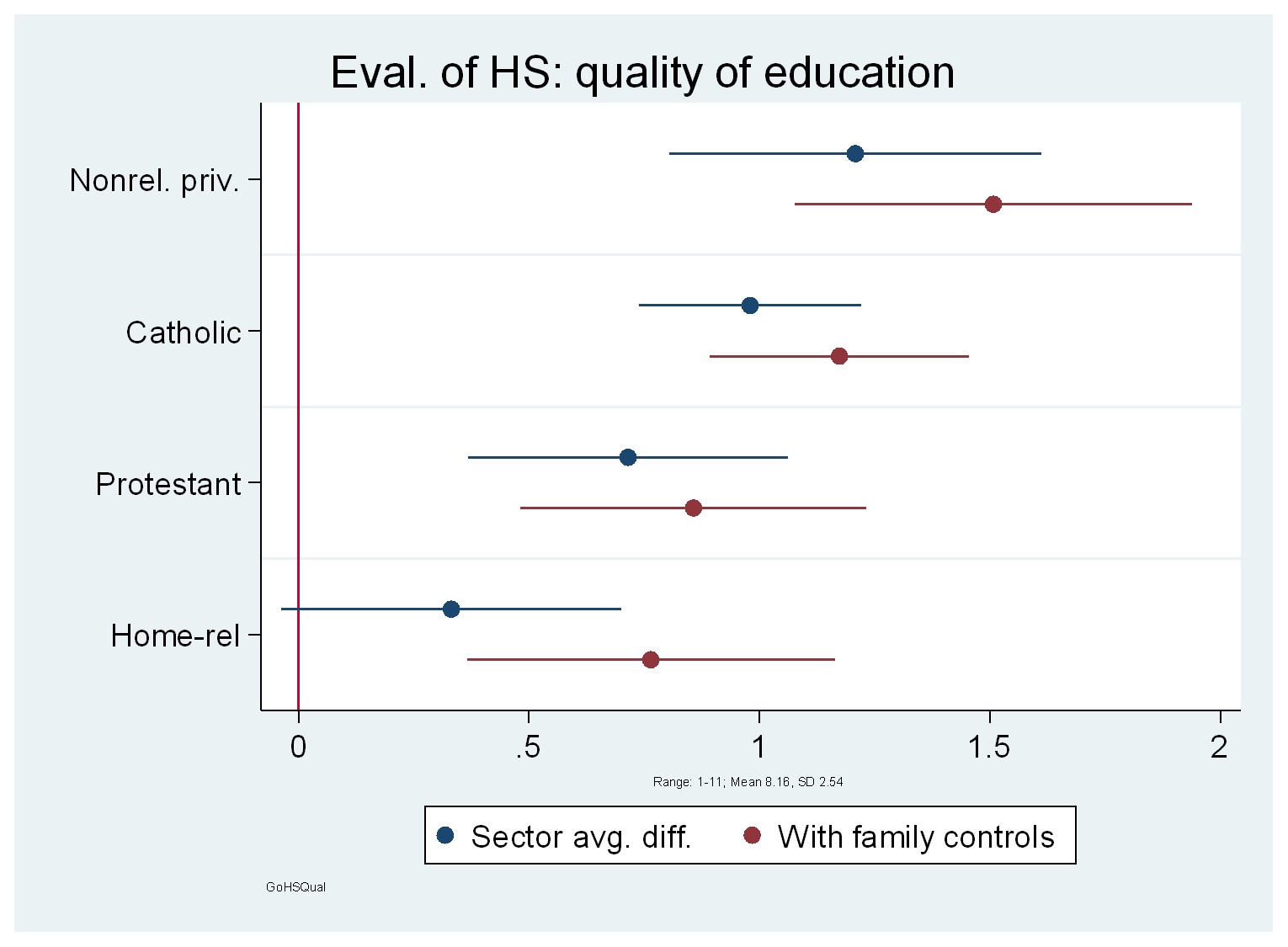

Graduates were asked to offer perceptions of their high school’s general quality of education. On this measure, private school graduates generally believe they received a higher quality of education relative to public school graduates. The sectoral differences on these measures are very strong, with non-religious private and Catholic school graduate estimates being over half a standard deviation on this measure. The average public school graduate (after controls for family background) is at about a 7.9 on this eleven point scale, while the average private school graduate is at nine or higher. If we consider the percentage in each sector that reports the highest score or second highest score (ten or eleven) on the quality of education in their school, we find that about twenty-nine percent of public school graduates (after accounting for family background) give their school the highest marks on this measure. In contrast, sixty-two percent of nonreligious private school graduates and fifty-seven percent of Catholic school graduates give their school the highest score. The Protestant school graduates are somewhat lower, at forty-five percent, but are still well above the public school graduates on this assessment of school quality. Interestingly, while previous Cardus Education Surveys of homeschool graduates found that they were mixed in their assessment of academic quality, 2018 findings reveal positive assessments by homeschool graduates of the academic quality of their education relative to public school graduates.

Perceptions of High School Climate

The 2018 CES also asks graduates a series of questions about their perceptions of the general climate of their high school, including whether it was too strict, the extent of social and athletic opportunities, and its religious climate. When graduates were asked whether they felt the rules were too strict at their high school, private school graduates were most in agreement with this statement. Catholic school graduates appear somewhat less likely to agree with this than other private school graduates, but remain significantly higher on this measure than public school graduates. The stronger normative climate in private schools, along with the religious formation goals of many religious schools, may explain these sectoral differences. A similar pattern of responses was found when graduates were asked whether they felt too sheltered in their high school environment; each private school sector is significantly higher on this measure than public school graduate responses. Not surprisingly, religious homeschool graduates appear to express the highest level of agreement in this sentiment, though Protestant school graduates express high levels of agreement as well.

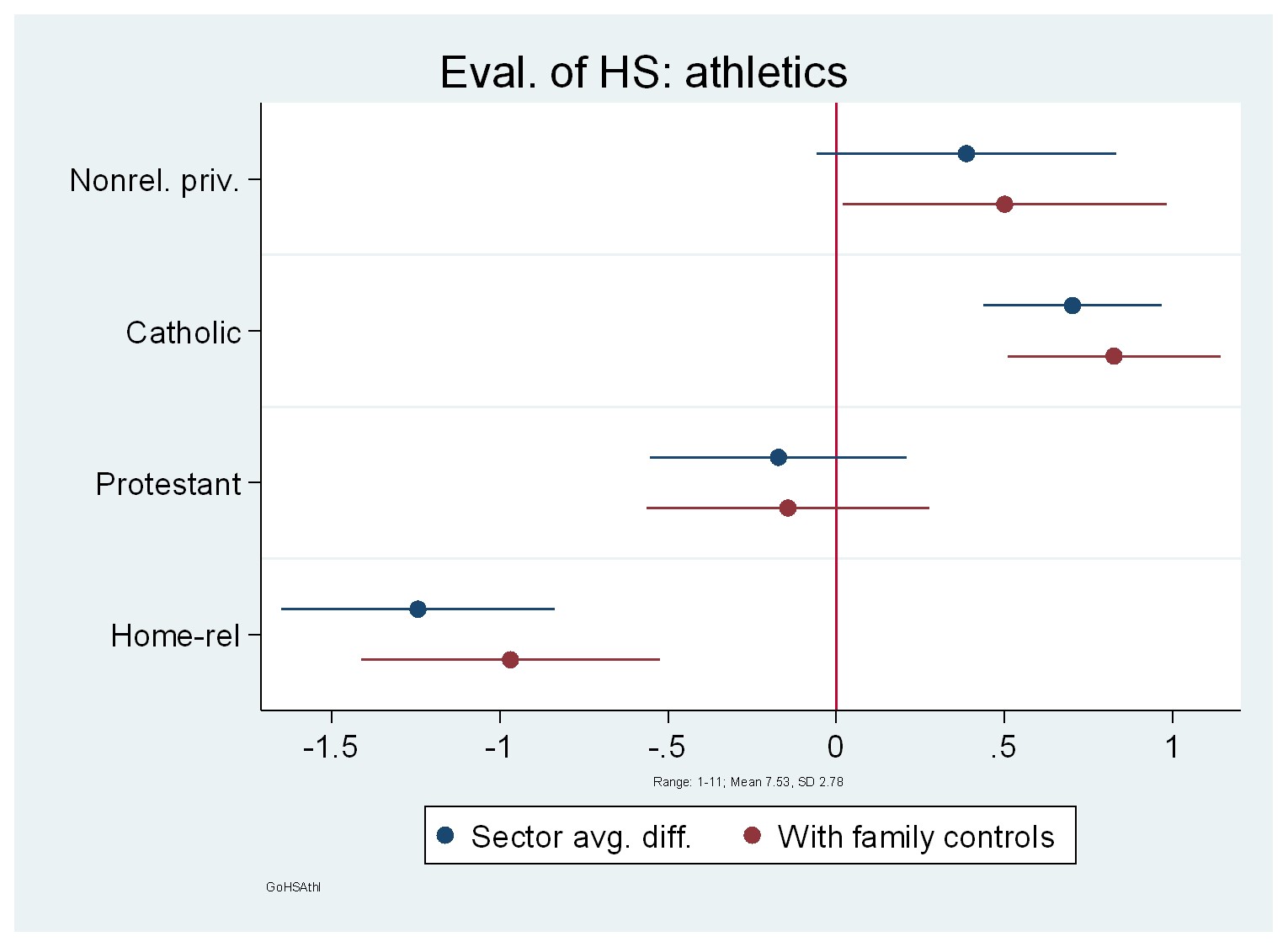

In terms of social opportunities available during the high school years, here as well we find that private school measures are significantly higher than public school graduates, with the exception of religious homeschool graduates, who were similar to public school graduates on this measure. Of course, it is important to keep in mind that homeschool graduates are in effect assessing their relationships with family in several of these evaluation measures. But on other measures the homeschooling differences are more directly interpretable. For example, religious homeschool graduates report significantly lower evaluations of the athletic opportunities in their high school relative to public school graduates; obviously, public school athletic opportunities are difficult to replicate through homeschool networks and cooperatives. Protestant school graduates are not overly impressed with their high school athletic opportunities either. Meanwhile, perhaps not surprisingly given Catholic school athletic traditions, the Catholic school graduates in our sample express a significantly more positive evaluation of the athletic opportunities in their high school. Non-religious private school graduates are also positive on this score relative to public school graduates.

The private school sectors are on average much higher in terms of their evaluation of their high schools’ religious and spiritual climate. The differences between the private school sectors are not large on this measure, which may result in part from a “religious matching” process in which families and students decide between private school sectors based on how religion is handled within the school. Still, it seems reasonable to argue that respondents to some extent conformed to the religious and spiritual climate of their school or developed an appreciation for it, whether this was within a non-religious or religious private school setting.

Relationships with Teachers, Other Students, and Preparation for the "Real World"

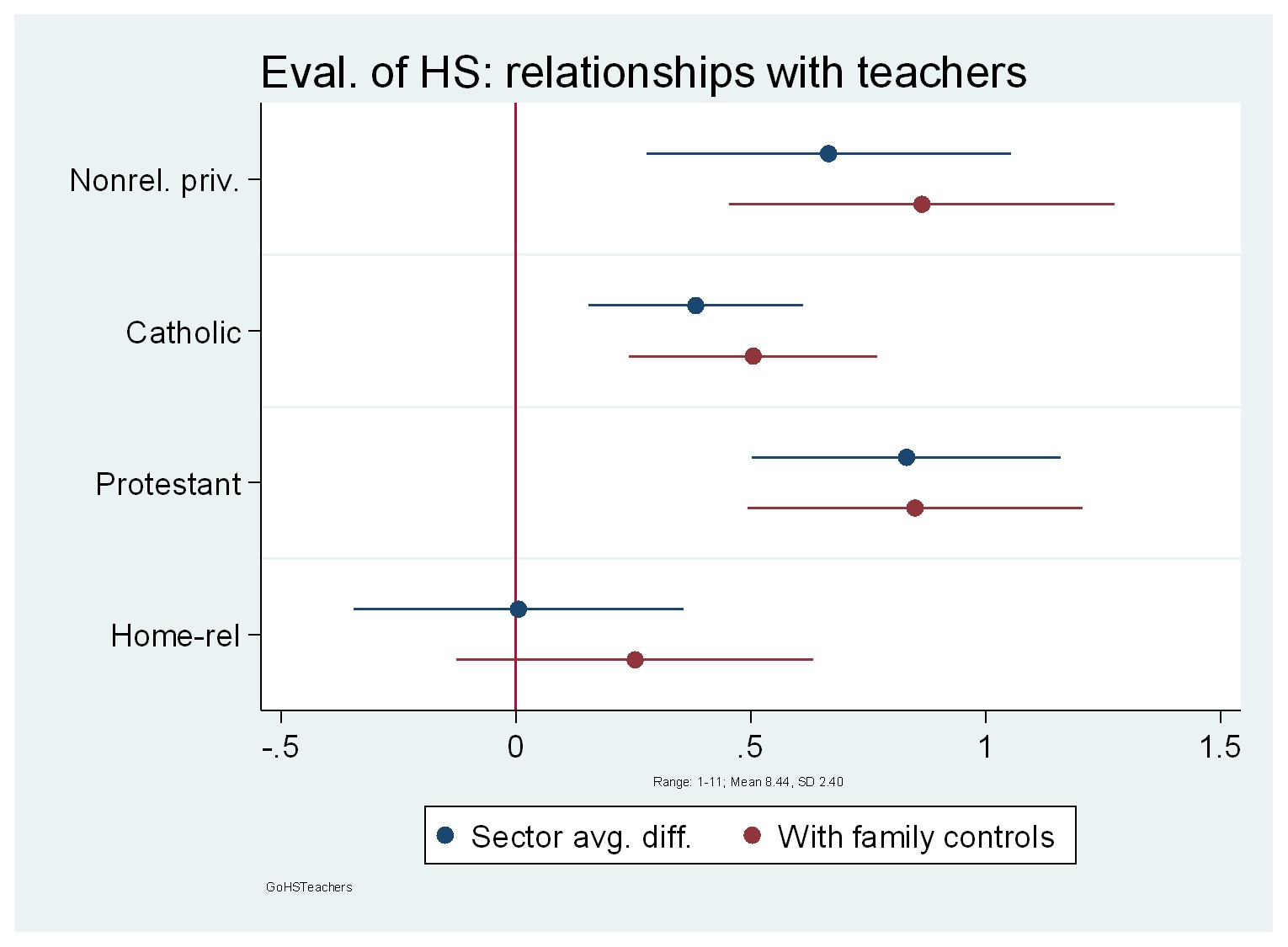

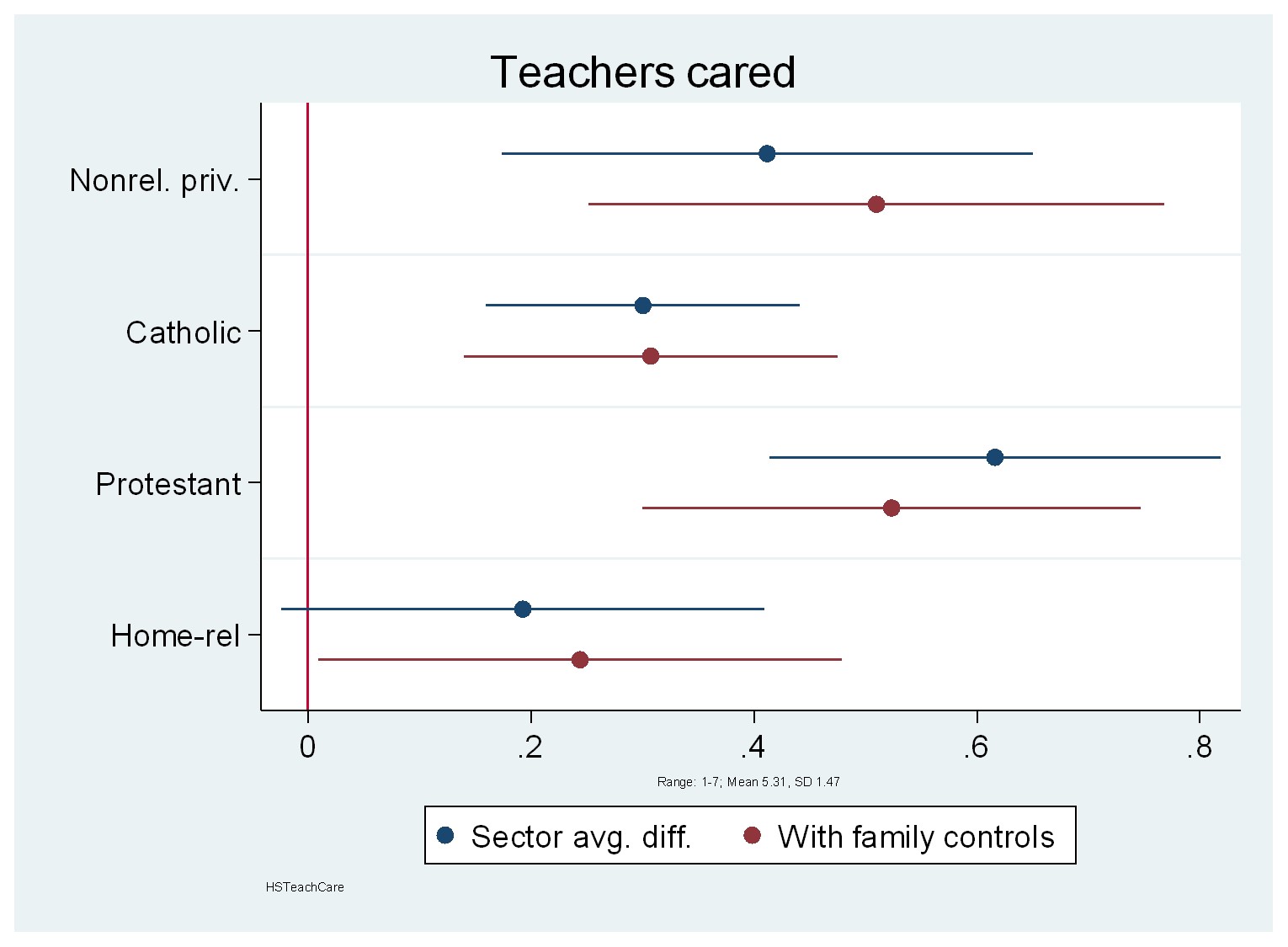

Relationships with teachers and having the sense that they really care is an important aspect of a positive schooling experience. The 2018 CES found that relationships with teachers are significantly more positive in the private school sectors. Religious homeschool graduates rated these relationships lower than did public school graduates, but the comparison is not a helpful one here as these graduates are essentially ranking family dynamics for the most part. All private school sectors are substantially higher than public school graduates in their agreement with the claim that teachers cared about the students in their high school. The adjusted averages reveal that public school graduates are closer to five on this seven-point scale while Protestant school graduates are closer to six (“mostly agree”). The percentage of graduates who give their teachers the highest score (“completely agree”) differs markedly across the school sectors. After accounting for family background, about fifteen percent of public school graduates “completely agree” that their teachers cared. In contrast, forty seven percent of nonreligious private school graduates and forty percent of Protestant school graduates “completely agree” that their teachers cared. Catholic school graduates are somewhat lower, at thirty-three percent, but are still much more likely to completely agree on this measure than are public school graduates. Relationships with administrators are also consistently much higher among the private school sectors relative to the public school sector. This may reflect the more personal and often pastoral role of administrator in a private school relative to the more bureaucratic and professional administrative role of the administrator in the public schools.

Relationships with other students are also reported to be very positive in private high schools. Similarly, private school graduates express much stronger agreement with the statement that their high school was “close-knit” than do public school graduates. The private school effects here are similarly high across all private school sectors, and well over half a standard deviation. The claim that students got along is also higher in the private school sectors, and while the Protestant and non-religious sectors appear to be most in agreement on this score, the private-school-sector differences are not significant.

By far the strongest divide in responses is found between public school graduates and all other private school sectors when they were asked whether they felt their high-school prepared them well for relationships in life. On average, public school graduates report a 2.2 on this four-point scale (1=not at all; 3= very well; 4=perfectly well), while the private school graduates are close to 2.6. The percentage of graduates who report being “very or perfectly well” prepared for dealing with relationships vary greatly across the different sectors, with only about thirty-seven percent of public school graduates on the high end of this scale.

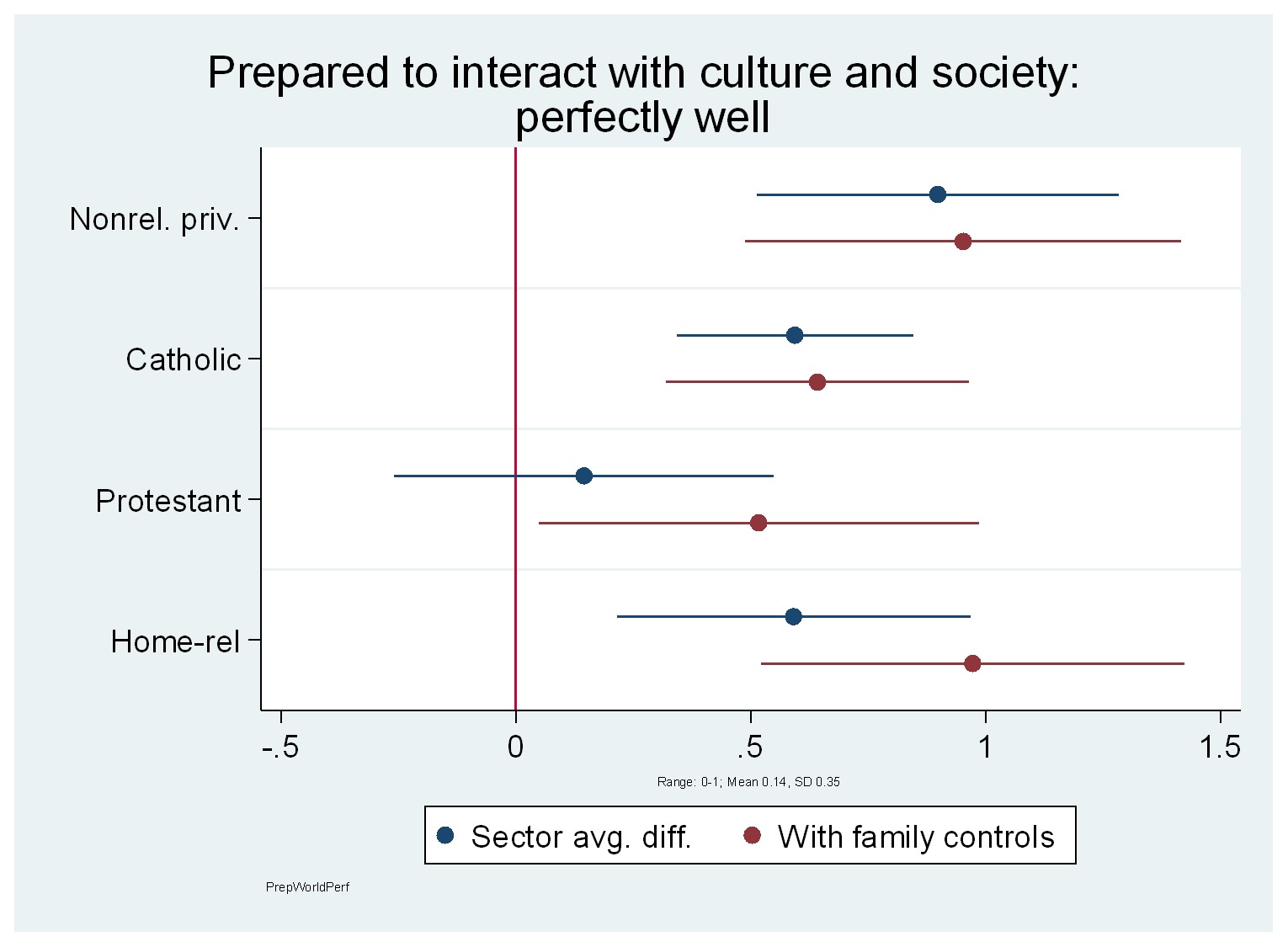

The 2018 CES probed graduates’ assessments of how well prepared they were for interaction with the dominant American society and culture. On this measure, non-religious private school graduates are in much stronger agreement that they are prepared for interaction “in the real world,” and Catholic school graduates are slightly lower on this measure. The Protestant school effect is less than half of the non-religious private school effect on this measure, though this private school difference is only marginally significant after controls. Protestant school graduates are slightly higher in their assessment of how well they were prepared for interaction with culture and society than publicschool-graduate assessments on this measure. Interestingly, non-religious private school graduates and religious homeschool graduates are over two and a half times more likely than public school graduates to believe that they were “perfectly well” prepared for interaction with culture and society.

Perceptions of Preparedness for University and Employment

The survey asked graduates to reflect on how well their high school prepared them for university and the job market. Private school graduates—both religious and non-religious—report higher levels of agreement than public school graduates that their high school experience prepared them well for a job. Graduates from the non-religious private school sector report the highest levels of agreement with this statement, but Catholic school graduates are not far behind. Interestingly, when we look only at respondents who felt “perfectly well prepared for a job” (versus not perfectly well prepared), religious homeschool graduates were on par with the non-religious private school sector and twice as likely as public school graduates to say they were perfectly or very well prepared for their job.

Non-religious private school graduates express a very high level of preparedness for university, as we would expect. Indeed, non-religious private school graduates are over four times more likely than public school graduates to report that they were “perfectly well prepared for university.” Again, Catholic school graduates are not far behind; they are about twice as likely as public school graduates to report that they were perfectly or well prepared for university. Protestant school graduates and religious homeschool graduates felt less prepared for university than public school graduates. When we look at only those respondents who felt “perfectly well” prepared, the non-religious private school advantage is more distinctive, significantly greater than Catholic and Protestant as well as public school graduates.

Conclusion

Private schools—both religious and non-religious—take the lead in terms of how well perceived they are by graduates in a number of areas. Reflecting on their high school years, young adults who attended private schools have a much more favourable assessment of these years than do public school graduates—a finding with important public implications and worthy of deeper exploration in future research. They also feel better prepared for university or the job market. The relationship between school culture and outcome measures of success—not only on the academic end but also in other areas of well-being—is an area of increasing interest to parents, school administrators, and researchers alike.

Public school graduates have, on average, the least favourable perceptions of the quality of their schools and of the relationships within it. What are the conditions within the public school context that might be influencing these perceptions? Do these conditions spark the need for new approaches within the public school? And what does this suggest for the role of private schools in contributing to well-being and social and mental health outcomes? Certainly, the contrast of private-school- and public-school-graduate responses on many of these measures points to a number of important areas for future research. What we do know with some certainty at this point is that private school graduates are, on average, feeling much more positive about their high school experience than are public school graduates.