Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

As educators navigate an increasingly complex landscape, collective leadership—working toward shared goals—is necessary to catalyze effective schools. In chemistry, a catalyst is a substance that accelerates a reaction without being used up. In leadership, a catalyst is someone who accelerates the good work of others in a sustainable way without burning out. Collective leadership enhances collective teacher efficacy, builds leadership pipelines, and spreads teaching expertise. Collective teacher efficacy refers to the educator’s belief in his or her ability to motivate and promote learning. High levels of collective teacher efficacy result in significantly higher levels of student achievement. At a time when school leaders are searching for opportunities to improve, collective leadership offers a process—not a panacea—for that improvement.

Christian independent-school leaders have a significant opportunity to leverage collective leadership as a catalyst for school improvement. Building on biblical models, Christian leaders in general, and leaders of Christian schools in particular, are well positioned to lead collectively. Survey data demonstrate differences between district and independent schools on the seven conditions that support collective leadership. Some of these differences can be attributed to different conceptions of leadership. Effective leadership of Christian schools is exemplified by ensuring that leaders serve others, using attributes of leadership in the early church while not conflating school and church, focusing on the gospel, building the body of Christ, and grounding leadership in confident humility.

Collective leadership that catalyzes school improvement ensures a shared vision and strategy, develops administrators who see collective leadership as a biblical model of leadership, aligns resources to ensure that teaching expertise spreads, uses supportive relationships and social norms to enhance shared influence, and supports networks of schools that can grow together. The collective leadership of Christian school leaders can be life-giving and has the potential to catalyze flourishing for each student.

Introduction

A pandemic, social unrest, political polarization, and mental-health issues have created unprecedented challenges for school leaders in North America. These challenges are manifesting themselves in myriad ways.

- Teacher morale is at an all-time low. 1 1 M. Will, “As Teacher Morale Hits a New Low, Schools Look for Ways to Give Breaks, Restoration,” Education Week, January 6, 2021, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/as-teacher-morale-hits-a-new-low-schools-look-for-ways-to-give-breaks-restoration/2021/01.

- In recent polls, 62 percent of parents do not want their children to become teachers, 2 2 PDK International, “PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools: 54th Annual Poll,” 2022, https://pdkpoll.org/2022-pdk-poll-results/. and enrollment in teacher preparation programs has decreased by 19 percent over the past decade. 3 3 US Department of Education and Office of Postsecondary Education, “Preparing and Credentialing the Nation’s Teachers: The Secretary’s Report on the Teacher Workforce,” 2022, 2, https://title2.ed.gov/Public/OPE%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

- Some states are resorting to filling classrooms with untrained educators. 4 4 M. Will, “States Crack Open the Door to Teachers Without College Degrees,” Education Week, August 2, 2022, https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/states-crack-open-the-door-to-teachers-without-college-degrees/2022/08.

- Student achievement in mathematics and reading has declined significantly over the past three years. 5 5 National Center for Education Statistics, "Long-Term Trends in Reading and Mathematics Achievement," US Department of Education, 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=38.

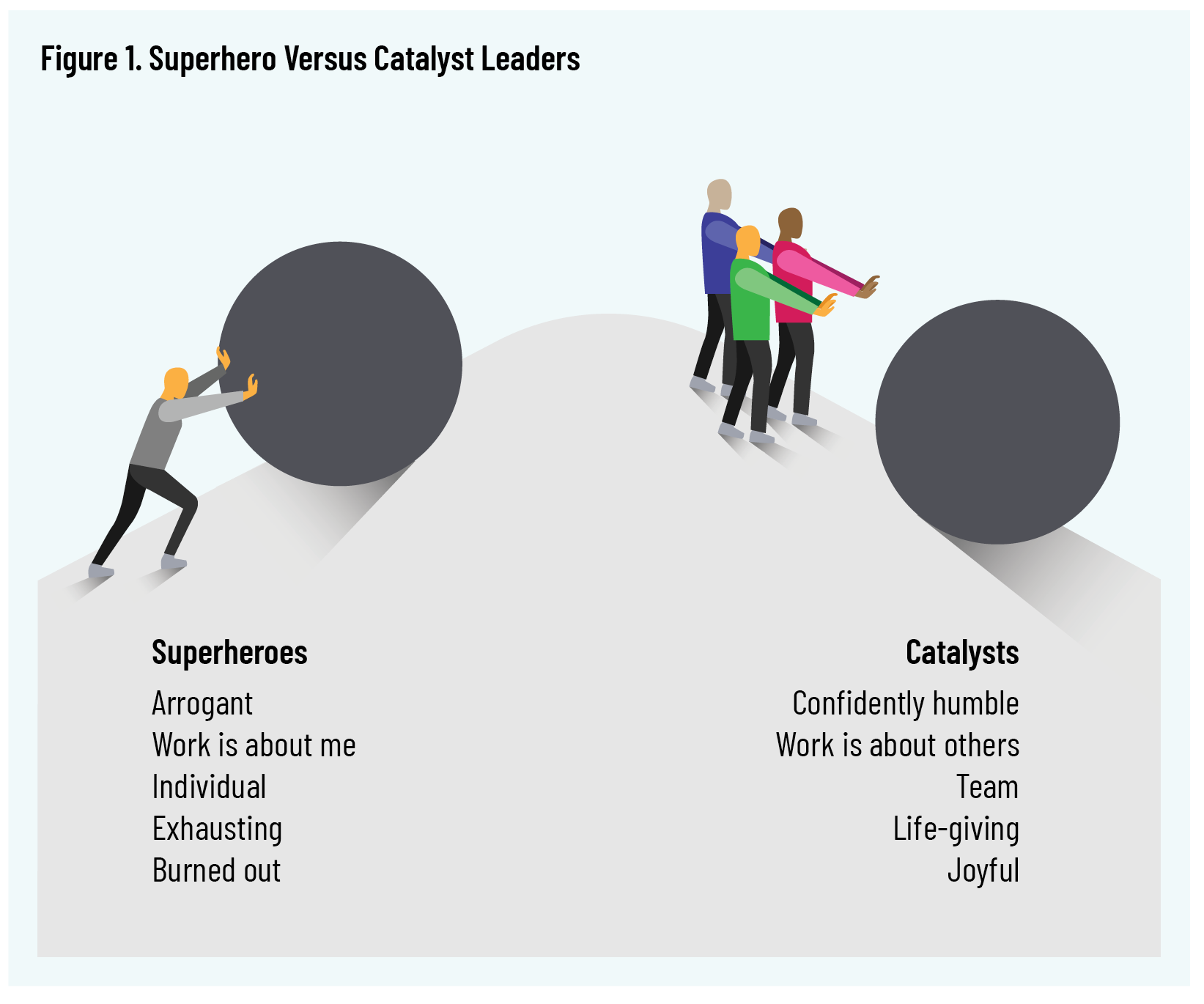

We regularly hear school leaders speak of confusion, inaction, frustration, unsustainability, friction, and burnout. School mission statements can sound hollow and incoherent. To cope and even to thrive in our current context, Christian independent schools don’t need superhero leaders who try to respond to these challenges single-handedly. This leads only to burnout for them and frustration for others. Instead, we need leaders to serve as catalysts. In chemistry, a catalyst accelerates a reaction without being used up. Catalyst leaders accelerate good work in ways that are sustainable, because the work is not about them. Catalysts tap others’ expertise, look for steps that can be eliminated, and try to find an easier way that serves more people. Figure 1 demonstrates the difference between leaders who attempt to function as superheroes and as catalysts.

Through the Baylor Center for School Leadership, we increasingly find that Generation Z and Millennial teachers are particularly drawn to leadership that is catalyzing. This is true beyond the education field also. 6 6 U. Kralova, “Millennial Managers Can Change Company Culture for the Better,” Harvard Business Review, October 27, 2021, https://hbr.org/2021/10/millennial-managers-can-change-company-culture-for-the-better; L. S. Rikleen, “What Your Youngest Employees Need Most Right Now,” Harvard Business Review, June 3, 2020, https://hbr.org/2020/06/what-your-youngest-employees-need-most-right-now. They tend toward collaboration and more flattened organizations, in which leadership and respect are based on skills and expertise as much as on positional authority. The generations that have seen billionaire CEOs in their twenties are ready to lead in innovative ways. Their ideal administrator provides coherence, mission clarity, and support for their emerging leadership and innovation. One way in which this leadership can be enacted is through a leadership style named collective leadership.

Collective leadership is the work of teachers and administrators toward shared goals. I have written extensively about this over the past decade, and there are more technical and nuanced definitions of this leadership style available. 7 7 J. Eckert, Leading Together: Teachers and Administrators Improving Student Outcomes (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2018); J. Eckert, “Collective Leadership Development: Emerging Themes From Urban, Suburban, and Rural High Schools,” Educational Administration Quarterly 55 no. 3 (2019): 477–509, https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X18799435; J. Eckert, G. B. Morgan, and R. N. Padgett, “Collective Leadership: Developing a Tool to Assess Educator Readiness and Efficacy,” Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 40, no. 4 (2022): 533–48, https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829211072284; J. Eckert and J. Butler, “Teaching and Leading for Exemplary STEM Learning: A Multi-Case Study,” Elementary School Journal 121, no. 4 (2021): 674–99, https://doi.org/10.1086/713976 However, in the simple definition that I give here, there are three key words: work, and, and shared. First, when teachers and administrators view leadership as being about the work, rather than the person as a leader, more people step up to leadership roles. They do not wonder if they are the right person, or if they have positional authority. They lead because they see work that needs to be done. Second, if students are going to thrive, teachers and administrators must lead together. Teaching and learning rarely improve based on administrative decree. And third, while leadership theorists in every sector emphasize the need for vision and strategy, these must be shared across teachers and administrators. If not, change or improvement will be sporadic or disjointed at best.

Collective leadership is an inclusive form of leadership in which expertise and willingness to work determine the way that leadership occurs. Collective leadership is more of a web than a hierarchy and emphasizes multiple paths to improvement. 8 8 W. W. Burke, Organizational Change: Theory and Practice, 4th ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014). In collectively led organizations, authority is based on expertise. Key leaders serve as hubs of productive work, rather than being deferred to because of a title or organizational chart. Those leaders become multipliers, helping everyone to contribute and to influence student outcomes. 9 9 L. Wiseman, Multipliers: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone Smarter, rev. ed. (New York: Harper Business, 2017); L. Wiseman, Impact Players: How to Take the Lead, Play Bigger, and Multiply Your Impact (New York: Harper Business, 2021). Roles still matter, because roles indicate expertise and responsibility. Not every individual in a school has the same level of influence, authority, or expertise. But collectively led organizations maximize each member’s knowledge, skills, and work in support of the shared mission.

Collective leadership has a stronger influence on student achievement than does individual leadership. A five-year study of forty-three school districts found that in almost all cases, teacher teams, parents, and students in high-performing schools have greater influence on school decisions than they do in low-performing schools. 10 10 L. Swaner et al., Future Ready: Innovative Missions and Models in Christian Education (Colorado Springs: Association of Christian Schools International and Cardus, 2022). Additionally, principals do not lose influence as others gain influence. 11 11 K. Leithwood and B. Mascall, “Collective Leadership Effects on Student Achievement,” Educational Administration Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2008): 529–61; K. S. Louis et al., “Investigating the Links to Improved Student Learning: Final Report of Research Findings,” Wallace Foundation, July 2010, http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Investigating-the-Links-to-Improved-Student-Learning.pdf. In schools that are collectively led, teams of educators lead work that results in better outcomes for students, while also growing leaders. Thriving educators and students are the desired outcome of collective school leadership.

Collectively led schools with strong orientations toward improvement also create leadership pipelines. As teachers and administrators work together, they better understand the positions of others and begin to appreciate and elevate others’ talents. When collective leadership occurs over years, teachers increasingly step into administrative roles, while some continue to lead from the classroom. Both avenues develop formal and informal leadership pipelines that schools need. When school boards and administrators believe in the collective expertise of teachers and students to meet context-specific missions, we have seen schools make remarkable progress. We have observed entrepreneurship programs, inclusive approaches to special education where each student has a sense of belonging, community-building projects, and deep impact through teacher and student-led initiatives. 12 12 For more on these stories, see Swaner et al., Future Ready. Since educational pluralism contributes to the public good, schools require inclusive, innovative leadership that cultivates learning communities committed to improvement. We have found that collective leadership enhances collective teacher efficacy, builds leadership pipelines, and spreads teaching expertise. Additionally, when leaders begin to see leadership as being about work, they stop wondering if they have the right position or personality and take ownership of the work that supports organizational goals. 13 13 For research findings, see Eckert, Leading Together; Eckert, “Collective Leadership Development,” 477–509; Eckert, Morgan, and Padgett, “Collective Leadership,” 533–48; Eckert and Butler, “Teaching and Leading,” 674–99.

This form of leadership is not a panacea for the challenges that Christian independent schools are facing, but it does support adaptive improvement that is more likely to meet contextualized needs. To illustrate, consider the sequoia redwood. These trees can live to be more than 2,500 years old. They can grow taller than three hundred feet and can weigh more than six thousand tons. Yet their roots are typically only six to twelve feet deep. How is this possible? The answer is that the roots exist in dense networks that provide nutrients and support. If schools are going to grow students into thriving giants, educators must develop those networks and provide opportunities for students to do the same.

Developing Collective Leadership

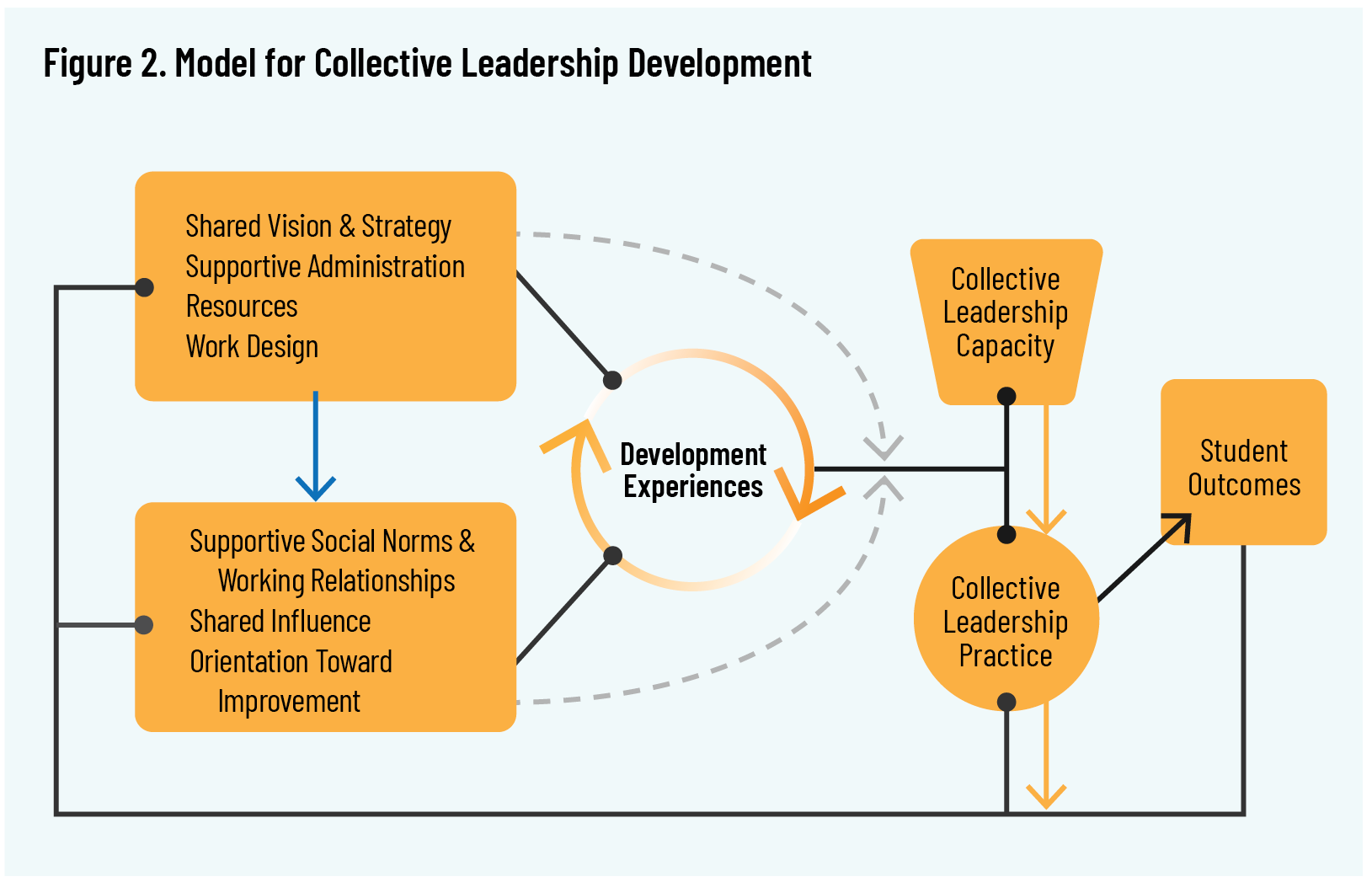

We have found that seven conditions are necessary to support the development of collective leadership:

- Shared vision and strategy of administrators and teachers is

- catalyzed by supportive administrators, who celebrate the leadership of others

- who have the financial and human capital to expand the mission of the school, because there is margin

- to design the work of educators so that expertise can spread (e.g., peer observation and feedback)

- to develop supportive working relationships and social norms that avoid the “crab bucket culture” 14 14 When crabbing, the bucket needs no lid. This is not because the crabs cannot climb out; in fact, they can. But when one crab makes progress up the inside of the bucket, other crabs pull it back down. This is a picture of what happens in schools if emerging leaders are dismissed or diminished by colleagues. See D. Duke, “How Do You Turn Around a Low-Performing School?” (paper presented at the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Annual Conference, New Orleans, March 15–17, 2008).

- so that the shared influence of administrators on teachers, teachers on administrators, and teachers on other teachers leads to a

- strong orientation toward improvement, where strategic risk-taking results in learning.

These seven conditions contribute to development experiences, that in turn develop capacity and improve leadership practices, leading to improved student outcomes (see figure 2).

The conditions in the upper box precede those in the lower box. The seven conditions influence the development experience in two ways. First, the black lines from the conditions feed the experiences. For example, in a school with a shared vision and an administrative team that supports the well-being of teachers and students, improving student well-being is likely to be more attainable than in a school where those conditions are lacking. Second, the dotted lines after the experiences either catalyze or diminish the effects of the experiences. To continue with the example, supportive administrators can accelerate good work that comes out of the well-being development experience by sharing power with teachers who will lead the work across classrooms, or they can diminish the work by under-cutting efforts due to fear of a loss of power. Depending on the strength of the development experience and the supporting conditions, schools will experience increases in collective-leadership capacity, which improves leadership practices that enhance student outcomes. Those outcomes then influence leadership practices and the seven conditions that support development, as the returning black lines indicate. Collective leadership is inclusive and iterative by design.

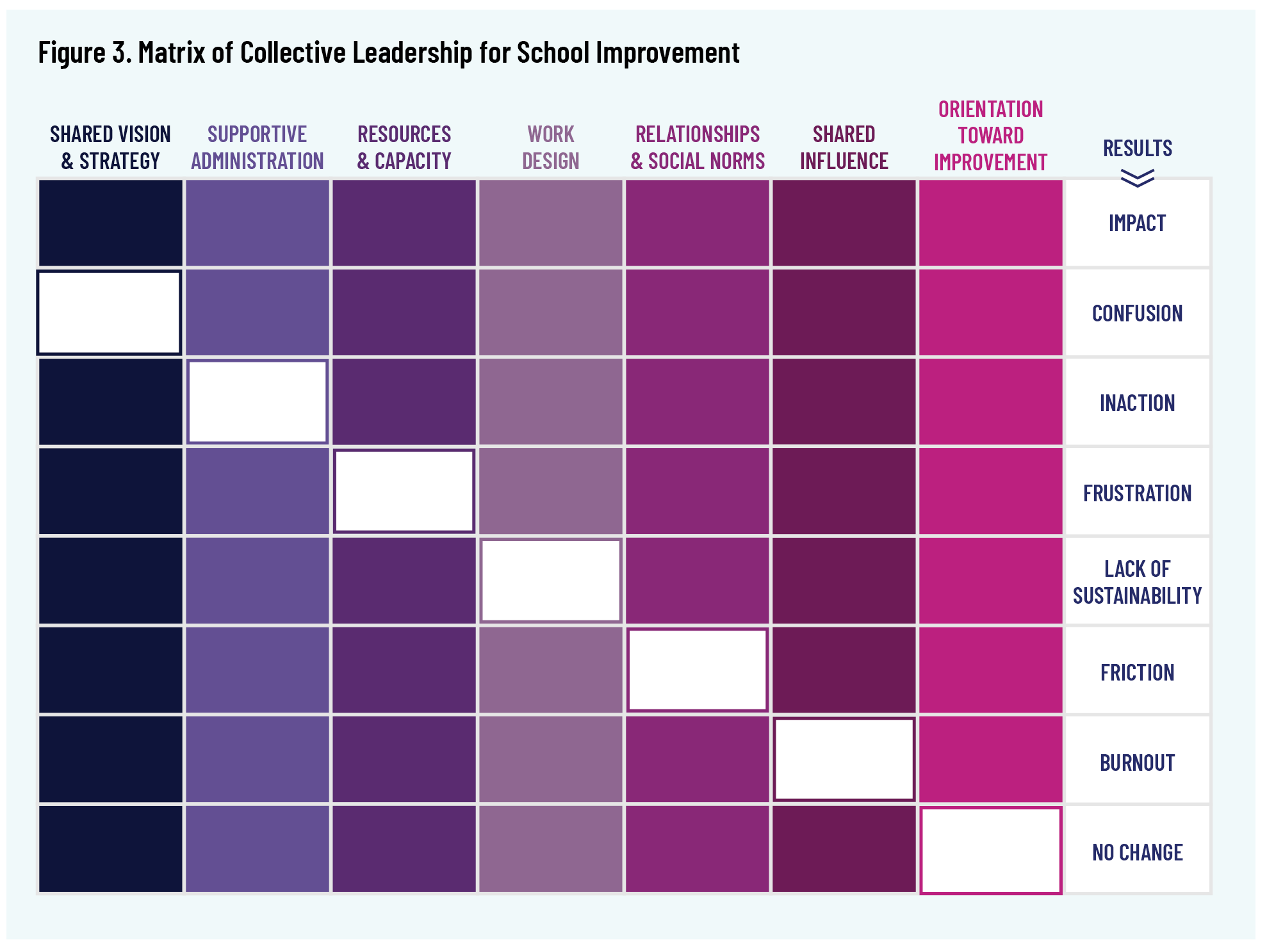

In schools that we work with, we often introduce collective leadership with the depiction shown in figure 3. Starting with the column on the right, labelled “Results,” we ask school leaders to identify which word best describes their school. If they are at “Impact,” this means that they are meeting their entire mission and each student is thriving. If all seven conditions are in fact present, then “Impact” is possible, although rare. Typically, school leaders choose another word or phrase. Whichever one they choose, together we look back across the row to see which condition is missing. If they choose the word “Burnout,” for example, then the hypothesis is that burnout results from a lack of shared influence. Certainly, the conditions influence one another, but the matrix begins to give school leaders insight for where they most need to improve.

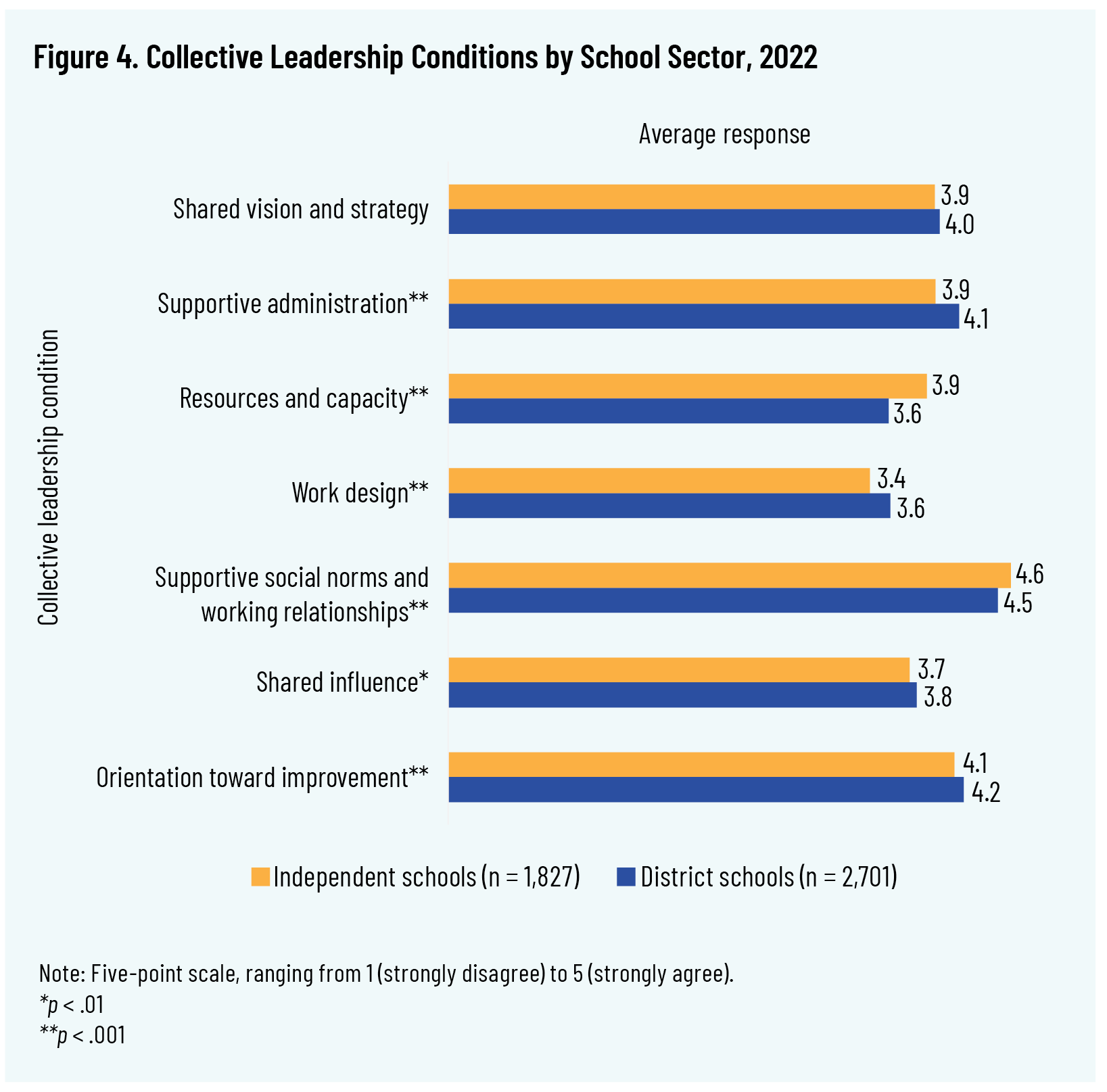

Since 2018, the Baylor Center for School Leadership has collected data on district and independent schools’ approaches to leadership. We surveyed 2,701 educators at forty-three district schools and 1,827 educators at forty-two independent schools (all but one of these were Protestant Christian schools). The samples are not representative of the sectors as a whole; these were schools that expressed interest in developing their collective leadership through the Baylor Center for School Leadership or the Center for Teaching Quality.

In figure 4 we provide the average rating of each collective leadership condition. The conditions come from a survey probes based on a five-point Likert-type scale, with response options ranging from “strongly disagree to “strongly agree.” We aggregate the responses to these items, as there are between one and four probes per condition. 15 15 For more information on the survey construction and analysis see Eckert and Butler, “Teaching and Leading,” 674–99.

We plan to explore these findings in more detail in future reports. Here are a few observations that demonstrate opportunities for collective leadership:

- There was no statistically significant difference for shared vision and strategy across respondents from district and independent schools. We assumed that Christian schools (forty-one of the forty-two independent schools surveyed) that shared a similar faith mission would be more aligned on a shared vision and strategy than other kinds of schools, but that was not the case. As with all the conditions, the responses were overwhelmingly positive, however, which might be due in part to the fact that all the schools that participated in the survey had already expressed some interest in collective leadership to improve their schools.

- Respondents, primarily classroom teachers, reported that district school administrators were significantly more supportive and more likely to share power (one of the underlying questions that informs this condition) than those in independent schools. While both groups of respondents reported average responses near “agree,” the district school respondents were significantly more positive.

- Independent school educators were significantly more positive about resources and capacity than were those in district schools. Their perception that they had adequate facilities, finances, time, and support was significantly higher than their district school counterparts. The difference in perception was the largest of any of the seven conditions (0.31). Although they perceived themselves to have greater resources, the independent school respondents were significantly less positive about work design, as related to professional learning and peer observation. In district schools, there was a much greater likelihood that teachers and administrators were examining student work during planning time and providing feedback to others on future learning experiences.

- Independent school teachers and administrators reported significantly more supportive relationships and social norms than district school educators. In both district and independent schools, this was the most highly rated construct, by a significant margin. Interestingly, while independent school respondents reported stronger relationships, they also reported significantly lower levels of shared influence when compared to district schools. When combined with the lower rating for work design, this seems to indicate that there is untapped potential in these independent schools for increased collaboration and shared influence that could enhance and spread teaching expertise.

- While both district and independent schools reported average responses between “agree” and “strongly agree” to items related to their orientation toward improvement, independent school educators were significantly less positive. When combined with the other conditions that are significantly lower—supportive administration, work design, and shared influence—there seems to be potential for improvement. Through document analysis and interviews, we have found that some independent schools do not have school improvement plans to organize their efforts. The district schools in our study are all required by their states to have school improvement plans. Several district schools in the study have taken their plans to a higher level of impact by inviting students—even elementary students—to participate in the development of their plans. This type of planning could provide some insights for independent schools as well.

Collective Teacher Efficacy

Collective teacher efficacy refers to the educator’s belief in his or her ability to motivate and promote learning. High levels of collective teacher efficacy result in significantly higher levels of student achievement. 16 16 A. Bandura, “Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning,” Educational Psychologist 28, no. 2 (1993): 117–48; R. D. Goddard, W. K. Hoy, and A. W. Hoy, “Collective Teacher Efficacy: Its Meaning, Measure, and Impact on Student Achievement,” American Educational Research Journal 37, no. 2 (2000): 479–507, https://doi.org/10.2307/1163531; J. Hattie, “The Applicability of Visible Learning to Higher Education,” Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 1, no. 1 (2015): 79–91, https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000021. In fact, researchers have found that collective teacher efficacy has the largest effect size on student learning compared to any other aspect of teaching and learning. 17 17 Hattie, “The Applicability of Visible Learning,” 79–91. Collective leadership seems to spur higher levels of collective educator efficacy, which results in higher levels of student achievement. 18 18 Eckert, Leading Together; Eckert, “Collective Leadership Development,” 477–509.

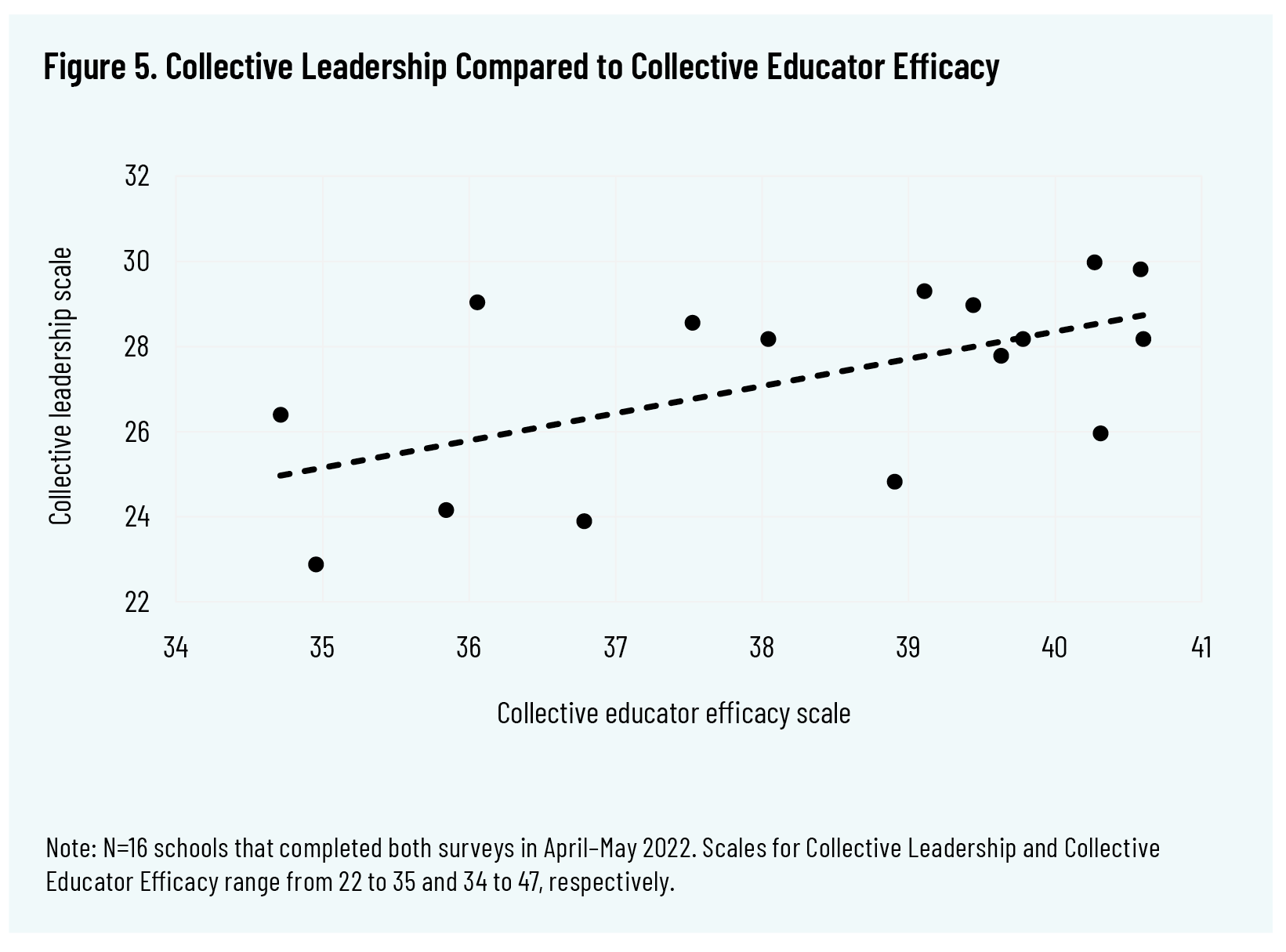

Our most recent analysis of data from sixteen district schools has found a strong correlation between collective leadership and collective teacher efficacy, based on two separate surveys given within one month of each other (see figure 5). 19 19 For a more detailed analysis of these data, see my forthcoming peer-reviewed paper. Additionally, each of the seven conditions has a moderate to strong correlation with collective teacher efficacy. These findings need to be replicated in independent schools, but for the first time, we have been able to connect the more distant influence of collective leadership to the more proximate benefit of collective teacher efficacy, which is likely to lead to improved student outcomes.

Objections and Opportunities

Collective leadership holds out great promise for Christian independent schools. Below, I address some concerns or objections that this sector might have, and offer my response.

Objection 1. Collective Leadership Is Messy; Someone Just Has to Make a Decision.

Yes, leaders must make decisions, and not every decision requires collective involvement. The greater the consequential impact of a decision, however, the better it is to seek input. A process that invites input might reduce efficiency on the front end, but it will increase the likelihood of effectiveness on the back end.

One Christian school administrator asked us, “How do we consider power dynamics in collective leadership conversations? It does not make sense to ‘mute’ a leader if he is the one making decisions.” Collective leadership does not “mute” anyone. Decision-makers in a collective-leadership setting should prioritize listening, though, because they hold the positional power that can discourage dissent in an unhealthy way. They should be catalysts of the conversation.

Objection 2. People Operate Out of Their Own Self-Interest. Teachers Do Not Understand the Full Picture.

People do operate out of self-interest, which brings conflict. This is one reason why we need collective leadership: to check the self-interest of leaders. It is also the case that when collective leadership is enacted, more information is shared and participants can expand their perspectives. Everyone is more likely to see opportunities for course correction and to lead humbly. Everyone is better able to understand the broader leadership picture. We have worked with hundreds of Christian schools over the past three years, and the schools that have been the most effective in leading through significant disruptions have been the ones that relied on teams of administrators and teachers, responsive to their communities. As one Christian school leader shared, “Anyone who believed they could lead through a pandemic, polarization, and social upheaval on their own is probably not leading now.”

Objection 3. Collective Leadership Is Not a Biblical Leadership Style.

There is biblical evidence for collective leadership. Christians often point to leaders such as Moses, David, or Paul to suggest that God works through individual leaders, but while these biblical figures made lonely decisions and boldly called others to follow God, in fact they did not lead alone. Moses had Aaron, Miriam, and Zipporah. His father-in-law even told him, “What you are doing is not good. You and the people with you will certainly wear yourselves out, for the thing is too heavy for you. You are not able to do it alone” (Ex 18:17b–18), and instructed Moses to find trustworthy men to help lead. David had his mighty men and prophetic counsel from Samuel and Nathan. Paul had Priscilla, Lydia, Aquila, Silas, Barnabas, and Timothy. Indeed, throughout the New Testament, the disciples consistently empower others to lead. Biblical leadership is moored in God’s Word, other believers, and God himself. Biblical leadership is not solitary.

Some Christian schools view leadership according to the pastoral model. But even when schools are connected to churches, they themselves are not churches, and the head of school is not the same as a pastor. While there are certainly characteristics that should be shared by school leaders and pastors, 20 20 J. W. Ferguson Jr., “The Headmaster as Pastor: Examining the Pastoral Leadership of Evangelical Christian Heads of School” (PhD diss., Dallas Baptist University, 2018), https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/headmaster-as-pastor-examining-pastoral/docview/2036846743/se-2; R. K. Greenleaf, The Servant as Leader (Cambridge, MA: Center for Applied Ethics, 1970). a school is not meant to function as the local church.

The idea that schools are churches can perpetuate the notion that because Christian schools are missional they can be less professional. Comments such as “Our teachers believe in the mission and are not here for the pay” and “We care about academics, but we are really about shaping students’ hearts and helping them be more like Christ” indicate that leaders in schools see their work as primarily missional. While these impulses are positive, they can erode a professional and academic culture. Some of these impulses are rooted in the anti-intellectualism of fundamentalism. 21 21 M. A. Noll, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994). Missional professionals who have a high view of their mission and of their profession should be leading Christian schools.

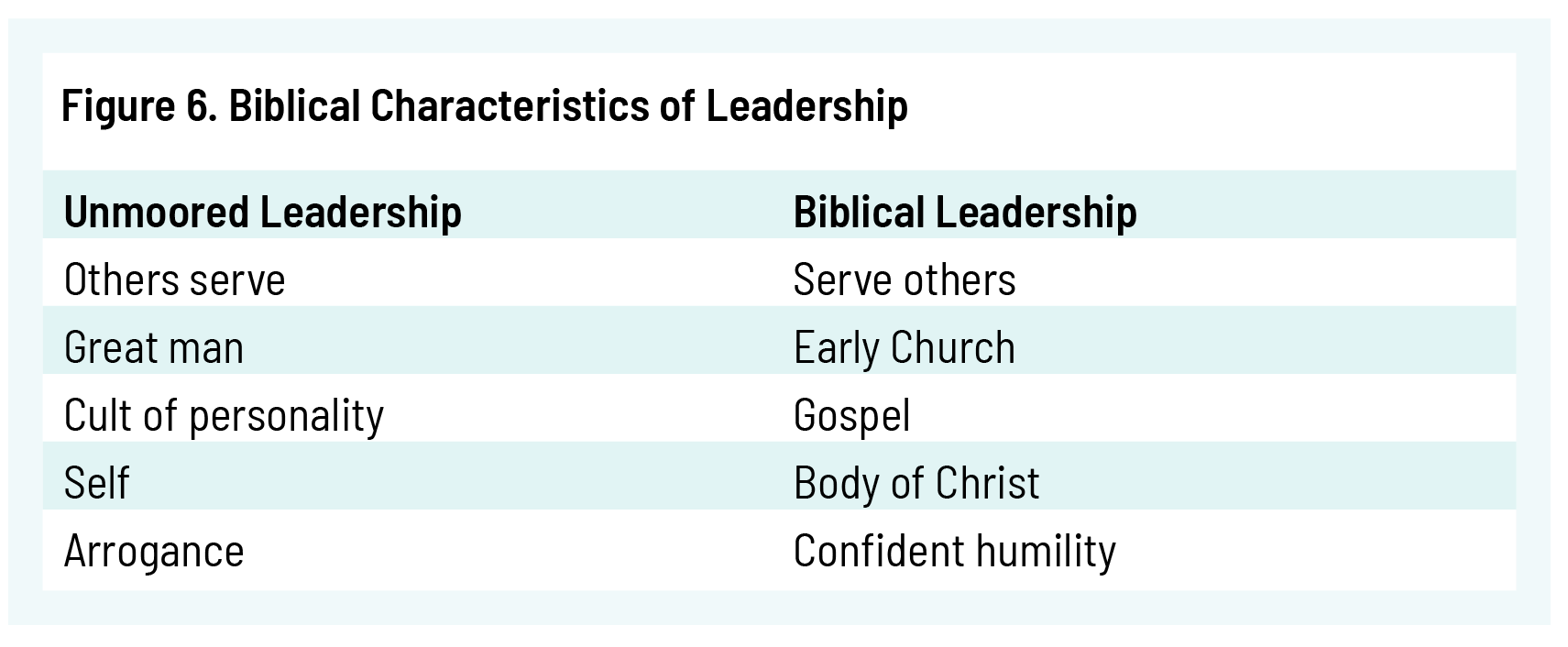

Figure 6 contrasts leadership that is unmoored and leadership that demonstrates biblical characteristics.

Others Serve Versus Serve Others

Leaders who desire to be catalysts of others see leadership as service toward a common goal, leadership that accelerates good work. Leaders who see the work as being about their own goals see others serving them. We hear this in the way that some leaders talk about people who “work for” them and leaders who need “buy in.” The term “buy in” conveys that there is an idea that is being sold to others to get them on board. Leaders who subscribe to a collective leadership philosophy will seek instead to tap the collective expertise of an organization, prioritizing shared ownership over “buy in.”

Great Man Versus Early Church

Although schools are not churches, the early church provides excellent examples of leadership to emulate. Hebrews 13:17 exhorts the church to obey their leaders. The word “leaders” is plural. 1 Peter 5:3–4 refers to elders and Christ as the chief shepherd or the shepherd of shepherds. Paul also refers to elders in Ephesus in Acts 20:17. The early church was not led by a single person but by a plurality of elders. A plurality of leaders is well suited to schools in our current context, with so much complexity facing the education sector and educators themselves. Christian schools serve the spiritual, physical, emotional, social, and mental development of each student—a task that requires the gifts of the entire body of Christ.

In the hundreds of Christian schools that we have served through the Baylor Center for School Leadership, we estimate that men are the heads of school in approximately 85 percent of these schools, and that approximately 80 percent of the teachers are women. 22 22 T. Thomas et al., “2021–22 AASA Superintendent Salary and Benefits Study,” American Association of School Administrators, 2022, https://www.aasa.org/docs/default-source/resources/reports/finalsuptsalary2022nonmemberversion.pdf?sfvrsn=cd84e58a_6; National Center for Education Statistics, “National Teacher and Principal Survey,” US Department of Education, 2015–16, https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ntps/tables/Principal_raceXgender_Percentage&Count_toNCES_091317.asp; National Center for Education Statistics, “Condition of Education 2022: At a Glance,” US Department of Education, 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2022/2022144_AtAGlance.pdf; M. H. Lee, A. Cheng, and K. Wiens, “2020 Principal Survey,” Council on Educational Standards and Accountability, 2021, https://www.cesaschools.org/assets/docs/cesa-survey-final-final1.pdf. In US district (public) schools, 24 percent of superintendents, 54 percent of school principals, and 76 percent of teachers are female. While there is no direct district-school corollary to a head of school position, a brief review of one of the leading Christian school organizations in the US, the Council on Educational Standards and Accountability, shows that approximately 90 percent of their Member of Council schools have male heads of school. Of those schools, 56 percent of principals are male, and 92 percent are white. Moreover, the percentage of teachers and leaders of colour is extremely low as well. We work with many talented leaders, but these data points suggest that there is a tremendously underutilized pool of talent and expertise that collective leadership could unleash. The early church was “multicultural and multiethnic from the outset” and today is “the most diverse, multiethnic, and multicultural movement in all of history.” 23 23 R. McLaughlin, Confronting Christianity: 12 Hard Questions for the World’s Largest Religion (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), 45. While the movement began with the leadership of men and women of different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds, Revelation 7:9 makes clear that this diversity is God’s good plan for eternity. In the present, if Christian schools are going to flourish, collective leadership is an ideal way to cultivate leaders from diverse backgrounds and enable them to work alongside each other with a common purpose.

Cult of Personality Versus Gospel

As Christians, we are called to live out the gospel and be conduits of love, grace, mercy, and justice in ways that reflect God’s glory. Paul provides a compelling example of this kind of life. The Holy Spirit made him a catalyst of exploding church growth, not a celebrity who stayed in one place to build an audience. Paul’s letters are to churches that he helped grow, but he did not stay to take advantage of the potential benefits of his status. 1 Corinthians 3:4–11 demonstrates the extent to which Paul eschewed the notion that his work was about him. When asked whether people should follow Paul or Apollos, his answer was that they should follow Christ.

Self Versus Body of Christ

Collective leadership that is biblically based is inclusive, gifts-based leadership. Most of the school leaders we have worked with through the Baylor Center for School Leadership know from their COVID-19 pandemic experience that they are more dependent than ever on the gifts, skills, and knowledge of their team. 1 Corinthians 12:19 reminds us, “If all were a single member, where would the body be?” To lead in schools in the decades to come, we will need the entire body of Christ.

Arrogance Versus Confident Humility

Micah 6:8 calls leaders to “walk humbly with their God.” Confident humility is the belief that we do not have all the answers, but that truth can be found. 24 24 A. Grant, Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know (New York: Viking, 2021). Christians know the source of truth and can balance confidence and humility. By contrast, arrogant leaders believe that they have the right answers regardless of what the truth might be. James 4:6 states, “God opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble.” Similarly, Paul writes, “Far be it from me to boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ by which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world” (Gal 6:14). Christian leaders should be marked by their confident humility.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Collective leadership for its own sake is inconsequential. When we lead for the ultimate sake of each student, we will cultivate thriving learning communities. Christian schools can lead the way in this work because they are well suited to serve a shared mission that helps students become all God created them to be. Missional professionals should fill Christian schools. After all, teaching is the profession that makes all others possible, and education serves the public well when individuals are maximizing all God created them to be. The following recommendations will increase the probability that collective leadership can be a catalyst for Christian schools to be thriving contributors to the public good.

- Ensure shared vision and strategy. School leaders can explicitly state the purpose and mission. Teachers and administrators can shape the vision and strategies together using continuous improvement. Inviting the collective expertise to contribute to consequential decisions will enhance the mission and increase ownership by teachers and administrators.

- Develop administrators who see collective leadership as a biblical model of leadership. For Generation Z and Millennials in particular, inclusive leadership based on expertise is particularly appealing. Moving away from models of school leadership that are singular, lonely, personality driven, and role based is desirable. This will lead to more inclusive leadership that is more representative of the Christian faith as a diverse movement at home and around the world.

- Align resources with work design, to ensure that teaching expertise spreads. Through collaboration, examine student work, provide opportunities for peer observation and feedback, and enhance collective teacher efficacy. Given the perceived resource advantages of independent schools, allocating resources for work that makes teaching more public should also improve teaching and learning.

- Use supportive relationships and social norms to enhance shared influence. The relationships that educators have with one another in Christian schools are a relative strength. Using these relationships to develop professionals who give and receive feedback for improvement can elevate school quality.

- Network schools using improvement science tools. When leaders ground their identity in Christ, not in their performance, they can work together to honestly appraise where they are at and where they need to be. Using disciplined inquiry and tools that collect evidence of how schools are meeting their mission, Christian schools can develop strong orientations toward improvement and take strategic risks that lead to learning.

Collective leadership is an effective way to grow giants because it provides roots and light. Like the sequoia redwoods, educators need intertwining roots that provide support and give life. Those same educators are better able to help students develop networks of support when they are all part of the same community. If Christian school educators can fully embrace collective leadership to catalyze the collective gifts of their teams, they can lead the way, grounded in truth, toward more vibrant learning communities that reflect the glory of our Creator. In Ephesians 5:13, Paul writes, “Everything that is exposed by the light becomes visible—and everything that is illuminated becomes a light.” Leadership is not about us or our light; we merely reflect God’s light so that others can do the same. When we do that in deeply connected communities, God grows giants through us.

References

Bandura, A. “Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning.” Educational Psychologist 28, no. 2 (1993): 117–48. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3.

Burke, W. W. Organizational Change: Theory and Practice. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014.

Duke, D. “How Do You Turn Around a Low-Performing School?” Paper presented at the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Annual Conference. New Orleans: March 15–17, 2008.

Eckert, J. “Collective Leadership Development: Emerging Themes From Urban, Suburban, and Rural High Schools.” Educational Administration Quarterly 55 no. 3 (2019): 477–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X18799435.

———. Leading Together: Teachers and Administrators Improving Student Outcomes. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2018.

Eckert, J., and J. Butler. “Teaching and Leading for Exemplary STEM Learning: A Multi-Case Study.” Elementary School Journal 121, no. 4 (2021): 674–99. https://doi.org/10.1086/713976.

Eckert, J., G. B. Morgan, and R. N. Padgett. “Collective Leadership: Developing a Tool to Assess Educator Readiness and Efficacy.” Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 40, no. 4 (2022): 533–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829211072284.

Ferguson, J. W., Jr. “The Headmaster as Pastor: Examining the Pastoral Leadership of Evangelical Christian Heads of School.” PhD Diss., Dallas Baptist University, 2018. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/headmaster-as-pastor-examining-pastoral/docview/2036846743/se-2.

Goddard, R. D., W. K. Hoy, and A. W. Hoy. “Collective Teacher Efficacy: Its Meaning, Measure, and Impact on Student Achievement.” American Educational Research Journal 37, no. 2 (2000): 479–507. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163531.

Grant, A. Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know. New York: Viking, 2021.

Greenleaf, R. K. The Servant as Leader. Cambridge, MA: Center for Applied Ethics, 1970.

Hattie, J. “The Applicability of Visible Learning to Higher Education.” Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology 1, no. 1 (2015): 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000021.

Kralova, U. “Millennial Managers Can Change Company Culture for the Better.” Harvard Business Review, October 27, 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/10/millennial-managers-can-change-company-culture-for-the-better.

Lee, M. H., A. Cheng, and K. Wiens. “2020 Principal Survey.” Council on Educational Standards and Accountability, 2021. https://www.cesaschools.org/assets/docs/cesa-survey-final-final1.pdf.

Leithwood, K., and B. Mascall. “Collective Leadership Effects on Student Achievement.” Educational Administration Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2008): 529–61.

Louis, K. S., K. Leithwood, K. L. Wahlstrom, and S. E. Anderson. “Investigating the Links to Improved Student Learning: Final Report of Research Findings.” Wallace Foundation, July 2010. http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/Investigating-the-Links-to-Improved-Student-Learning.pdf.

McLaughlin, R. Confronting Christianity: 12 Hard Questions for the World’s Largest Religion. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Condition of Education 2022: At a Glance.” US Department of Education, 2022. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2022/2022144_AtAGlance.pdf.

———. “Long-Term Trends in Reading and Mathematics Achievement,” US Department of Education, 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=38.

———. “National Teacher and Principal Survey.” US Department of Education, 2015–16, https://shorturl.at/hyC25.

Noll, M. A. The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994.

PDK International. “PDK Poll of the Public’s Attitudes Toward the Public Schools: 54th Annual Poll.” 2022. https://pdkpoll.org/2022-pdk-poll-results/.

Rikleen, L. S. “What Your Youngest Employees Need Most Right Now.” Harvard Business Review, June 3, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/06/what-your-youngest-employees-need-most-right-now.

Swaner, L., J. Eckert, E. Ellefsen, and M. H. Lee. Future Ready: Innovative Missions and Models in Christian Education. Colorado Springs: Association of Christian Schools International and Cardus, 2022.

Thomas, T., C. H. Tienken, L. Kang, and G. J. Petersen. “2021–22 AASA Superintendent Salary and Benefits Study.” American Association of School Administrators, 2022. https://www.aasa.org/docs/default-source/resources/reports/finalsuptsalary2022nonmemberversion.pdf?sfvrsn=cd84e58a_6.

US Department of Education and Office of Postsecondary Education. “Preparing and Credentialing the Nation’s Teachers: The Secretary’s Report on the Teacher Workforce.” 2022, https://title2.ed.gov/Public/OPE%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

Will, M. “As Teacher Morale Hits a New Low, Schools Look for Ways to Give Breaks, Restoration.” Education Week, January 6, 2021. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/as-teacher-morale-hits-a-new-low-schools-look-for-ways-to-give-breaks-restoration/2021/01.

———. “States Crack Open the Door to Teachers Without College Degrees.” Education Week, August 2, 2022. https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/states-crack-open-the-door-to-teachers-without-college-degrees/2022/08.

Wiseman, L. Impact Players: How to Take the Lead, Play Bigger, and Multiply Your Impact. New York: Harper Business, 2021.

———. Multipliers: How the Best Leaders Make Everyone Smarter. Rev. Ed. New York: Harper Business, 2017.