Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Ontario schools closed on March 12, in response to COVID-19, and they will remain closed for the rest of the 2019/2020 school year. Although enrichment materials are available online and some teacher-led, remote, online-based learning resumed April 6, the inadequacy of the response has revealed cracks in the school system and government-run schools.

Context: Starting With The Deeper Issues That Preceded The Crisis

Adjusting to remote, online-based instruction is a challenge—for students, parents, and teachers. But in addressing the crisis at hand, it is important to first highlight the following deeper public-policy issues that preceded it:

- Even at the best of times, not all students learn the same way. Just as the current reality is not a good fit for many students, neither is the status quo.

- If the rationale for the existence of local school boards is so that decisions will be made as close to those affected by them as possible—which they should be—then Ontario needs to reconsider how education is funded and who is best able to identify what is best for each particular child.

- Alternative methods of educational delivery are poorly understood and underappreciated. This results in an impoverished concept of public education—devoid of its full potential.

Cracks In The System

Not only was the COVID-19 response slow and limited in delivering remote instruction, but the very students who are most likely to get left behind in times like the 2020 lockdown are those who most need education in order to move up the economic ladder. For example:

Low-income households are less likely to have the resources to accommodate home-based online education, which requires strong-bandwidth internet and a productive internet-enabled device, such as a laptop or desktop.

Special needs students face unnecessary burdens and inequities in Ontario. Unlike other provinces such as British Columbia that fund special education on a per-pupil needs basis without regard to the type of school attended, Ontario’s Ministry of Education does not provide any funding for students with special needs enrolled in independent schools.

For Comparison: How Did Independent Schools Respond?

Importantly, Ontario’s independent schools responded much faster and more fully to the crisis, not only because they are nimble, but because they are profoundly accountable to parents. Their administrators and teachers worked through spring break to ensure a rapid transition with minimal educational disruption. They cannot risk a slow or insufficient response, as at any time their parents can walk away and take their funds with them. Parents of students at government-run schools do not have that luxury—nor do taxpayers. So, although it is natural to adjust education expectations amid this unprecedented crisis, independent schools have actively demonstrated that a relatively smooth pivot is possible.

Public Policy Problems

The recent lockdown reveals three problems for Ontario’s K-12 education system and its government-run schools:

- Inflexibility in crisis response and remote instruction

- Inequity in the delivery of education

- Inefficiency in the Ministry of Education’s funding model and the allocation of its resources

The first step in addressing these policy problems is to better understand both (1) what is being done effectively elsewhere and (2) where the problem is already being addressed in Ontario—in other words, in independent schools—before considering the policy recommendation proposed by this paper.

Learning From Educational Pluralism In Europe

In OECD countries where independent schools receive greater proportions of taxpayer funding, the socio-economic disparities between government and non-government schools disappears. Put differently, when there is a greater quantity and variety of highly taxpayer funded non-governmentmanaged K-12 education options, the differences between advantaged and disadvantaged populations narrows. Europe has many examples of this, like the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, and the Slovak Republic.

An educational system in which independent schools and robust parental choice are structurally embedded in government policy is a key tool for the reduction of inequality.

Embracing Imagination In Public Education

In addition to being an integral component of a truly pluralistic educational ecosystem—the democratic norm in progressive Europe—independent schooling should be considered within Ontario’s conception of taxpayer-funded public education because it is a merit good: meaning, it has spillover effects that positively affect all of society, not just the individual students being educated, their families, or their school communities. In other words, K–12 education has public benefit and thus is in the public interest, even when administered independent of the state.

Understanding Independent Schools

Despite myths to the contrary, at least 96 percent of Ontario “private” schools are not bastions of privilege. Independent-school parents are typically middle-class Canadians who choose their independent school for its safety, nurturing environment, and a variety of other reasons unique to each particular family. Independent schools—and religious independent schools, in particular—do not threaten civic formation but actually form thoughtful graduates who are more likely to be civically minded, committed to personal growth, and contributors to the public good.

Given the evidence, how might the Ontario government make more space for graduates of this sort to emerge, and for increased diversity in the Ontario education system?

Policy Recommendation: Innovation Through Direct Education Assistance (Idea)

To do this flexibly and efficiently, the policy paper makes the case for introducing the Innovation through Direct Education Assistance (IDEA) program to route education funds directly to parents of program-participating students to support the child’s education. IDEA funds can have multiple uses but will be restricted to the purpose of education, such as: independent school tuition, personal tutoring, software and learning equipment (e.g. computer), therapies for special needs, and educational materials, to name a few. Basic eligibility in the program should be open to all Ontario school-age children but require opting in, with funding particularly targeting students from low-income families or with special needs. Ontario students with special needs, especially, should be fully respected and receive full funding to support them in identifying and experiencing the best possible education for their unique needs—whether at an independent school, a blended-learning cooperative education program, or an entirely new innovation.

Introduction

Due to COVID-19, Ontario schools are closed throughout the province (Ministry of Education 2020c), and they will not reopen before the end of the school year (Office of the Premier 2020). The lockdown has revealed cracks in the flexibility, equity, and efficiency of the school system and, in particular, in government-run schools.

What if there were ways to make our current system more organic? What if we could change some of its structures to make it less fragile? What if, as a society, we moved toward a more diffused, distributed, and diverse education system that allows the system to respond in myriad ways to crises that affect us all? This paper makes the case for expanding Ontario’s conception of public education, reimagining the non-government school sector, and supporting innovation in adapting to the challenges of the present crisis and the post-pandemic education landscape.

Adding Value

Cardus is a social-policy think tank, committed to a flourishing society for the common good. Our education research is used by education experts throughout the globe. Two of our data sets—the Cardus Education Survey (CES) and Who Chooses Independent Schools and Why (hereafter, Who Chooses)—are the primary sources informing this policy paper.

Prior to 2011, there was very little quantitative measurement to prove or disprove any claims made about religious-independent-school-graduate outcomes in Canada and the United States, so we launched the CES. Now, with nearly a decade’s worth of data (the largest data set of its kind), we are proud that our education measurements have become the benchmark study of non-government religious-school outcomes in North America. Similarly, the Who Chooses data is the first of its kind, comparing representative findings in the three provinces of Ontario, British Columbia (BC), and Alberta.

Context

In identifying and responding to the public-policy problem, it is important to consider both the crisis at hand and the deeper issues that, although exposed by the crisis, preceded it and will remain if unaddressed.

Responding to the Crisis at Hand

The COVID-19 lockdown caught Ontario’s Ministry of Education, and its peers across Canada and around the world, unprepared. The general public understands the unexpected nature of the challenge and Ontarians are—and will likely continue to be—relatively generous in their assessment of how the crisis was handled by government and educational institutions.

But what about next time? Parents, students, and the electorate will be less forgiving if those who are responsible for delivering education remain unprepared.

And “next time” may be soon. Although new COVID-19 cases and fatalities have declined, the ministry needs to be prepared for a second and future waves. New data may emerge indicating it is still unsafe to reopen schools in the near future. Or, after returning to school, we may experience another outbreak in the months or years ahead.

Responding to the Deeper Themes

The lockdown did not cause but rather exposed a deeper public-policy issue. Even at the best of times, not all kids fit in and not all students learn the same way. That is the first deeper theme that needs to be addressed.

And in tandem with an appreciation for the differences in student need, a second underlying theme concerns who is best able to identify what is best for a particular child. Much of Ontario’s education budget is entrusted to district school boards, suggesting that decisions are made at a local level. But Ontario’s school boards are hardly “local.” For example, the Toronto District School Board oversees 583 schools and more than 243,000 students, making it not only Canada’s largest school board but also one of North America’s largest (Toronto District School Board 2020). Or take the Upper Canada District School Board; it covers approximately 12,000 kilometres (Upper Canada District School Board 2020), from Arnprior to Gananoque to Hawkesbury—an over-four-hour drive, without traffic. Moreover, Ontario has 444 municipalities, but only 72 school districts. If the rationale for local school boards is so that decisions are made as close to those affected by them as possible—which it should be—then Ontario needs to reconsider how education is funded and who is best able to identify best fit.

A third theme is the need to address systemic stereotypes around the role of government and parents in education, and around the types of structures through which public education is delivered. The policy problem cannot be resolved without a significant change of perspective on independent schooling, the structures in which education is delivered, and the goals of public education.

Cracks in the System

Well before the lockdown, the most recent University of Toronto OISE Survey 1 1 Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE). showed that Ontarians were not satisfied with K–12 education (Hart and Kempf 2018). Only 35 percent of Ontarians reported a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in Ontario schools. Only 50 percent and 53 percent of Ontarians were satisfied with the school system and the job teachers were doing, respectively. And 38 percent and 42 percent are satisfied with schools’ contribution to children/students’ physical and social/ emotional development, respectively (Hart and Kempf 2018, 10–12).

With that context, let us turn to three cracks exposed by the lockdown—namely, a lack of flexibility, equity, and efficiency.

Inflexibility: Cracks in Response and Remote Instruction

The first and most obvious issue brought on by COVID-19 is the slow and limited response in delivering remote instruction, exposing the inflexibility throughout the system, and how ineffective a one-sizefits-all approach is to K–12 education.

On March 12, heading into the eve of spring break, the Ontario government was the first in Canada to close all schools in response to COVID-19 (Lecce 2020a). However, it was not until March 24 that Minister of Education Stephen Lecce informed parents of the government’s lockdown policy (Lecce 2020a), and although enrichment materials were made available online, it was not until April 6 that teacher-led learning resumed with limited instructional support. The expected weekly workload per student is just five hours for kindergarten to grade 6, ten hours for grade 7 and 8, and three hours per course for semestered students or 1.5 hours for non-semestered students in grades 9 through 12 (Lecce 2020b; 2020c). Very little instruction is being provided, and as no tests or grades will be given, participation is essentially optional—for students (and teachers).

By contrast, Ontario’s independent-school administrators and teachers worked through spring break to ensure a rapid transition with minimal educational disruption. So, although it is natural to adjust education expectations amid this unprecedented crisis, independent schools have actively demonstrated that a relatively smooth pivot is possible.

Yet the switch to primarily online delivery of education is difficult for many—regardless of school type. The challenges include not enough devices for all the school-aged children in a household, not having a parent or guardian available to help, limited or no internet access, and simply struggling to learn in a remote and online environment. But regardless of setting—whether remote and online, or in a conventional classroom—this crisis has reiterated the truth that one size certainly does not fit all in K–12 education.

Inequity: Cracks in the Promise of Education for All

The second issue relates to equality of opportunity. The very ones who are most likely to get left behind in times like the 2020 lockdown are those who most need education in order to move up the economic ladder. Low-income households are less likely to have the resources to accommodate home-based online education, which requires strong-bandwidth internet and a productive internet-enabled device such as a laptop or desktop computer (Statistics Canada 2020). Moreover, of all families with children, female lone parents are nearly four times more likely than any other family group to live in poverty (Sarlo 2019). The financial struggle is thus compounded with the challenges of supporting at-home education while parenting alone and likely working.

COVID-19 has exacerbated previous inequalities. Pre-lockdown, one’s postal code tended to reveal the quality of one’s local school. A school in a wealthy community can raise a lot of revenue with a little fundraising, and parents in such schools have more options in how they can support the school—not only financially but also by volunteering their time and social capital (Miller 2019). Schools in disadvantaged neighbourhoods live a very different experience, and where enrolment is declining, decreasing budgets compound the problem. And despite policy innovations at the districtschool-board level (e.g., optional attendance, alternative schools, specialized schools and programs, e-learning), school choices for many Ontario families are practically limited. The challenges of the lockdown have only widened these disparities, especially for families on the lower end of the income spectrum and students with special needs.

Importantly, it does not help that the inequity in special-education funding is compounded by sector discrimination. Unlike other jurisdictions that fund special education on a per-pupil needs basis indiscriminate of school attended—such as British Columbia 2 2 In BC, schools receive per-pupil operating grants for students in grade 9 and under, but for grade 10 through grade 12 funding is on a per-course basis. The basic annual per-pupil allocation is $7,468 for government-run schools, $3,734 for regulated independent schools that spend less on operations than government schools (“Group 1” schools), and $2,614 for regulated independents that exceed their government-run peers’ operating expenses (“Group 2” schools); plus additional supplements (Hunt and Van Pelt 2019). Special education supplements are fully funded regardless of school type and are categorized into three levels of need, ranging from $10,250 for students with serious mental illness or intensive behaviour interventions to $42,400 for students with physical dependence or deafness or blindness (BC Ministry of Education 2019, 6). It is simple, efficient, and effective. —Ontario’s Ministry of Education does not provide any funding for students with special needs enrolled in independent schools. 3 3 Ontario’s Ministry of Health provides limited funding for specified health-related disabilities Critically, BC students and parents are supported in finding the very best option, as all BC special education is fully funded, whether at a government-run or independent school. 4 4 Cardus’s 2019 policy paper “Funding Fairness for Students in Ontario with Special Needs” details the unique and extreme inequity in Ontario’s treatment of special-needs students outside government-run schools (Van Pelt, Pennings, and Jackson 2019), which contradicts the ministry’s specified goal for Special Education Grants of “[ensuring] equity in access to learning for all students with special education needs”(Ministry of Education 2019a, 1). COVID provides the ideal time for Ontario to pivot to such a model.

Inefficiency: Cracks in the Funding Model

The third issue is Ontario’s funding model. It is inefficient: full of burdensome complexity and with funds distributed to school boards, not students. 5 5 Ontario’s district school boards are funded through Grants for Student Needs (GSN) on a per-pupil, per-school, or per-board basis. The GSN has two major components: (1) Foundation Grants to cover basic costs, on a per-pupil and per-school basis, and (2) Special Purpose Grants to target extra funding to unique student and school needs, including but not limited to special education, Indigenous education, and remote geographic circumstances. (Ministry of Education 2019b). Although the largest allocation ($10.57 billion) of the province’s roughly $24.66 billion education budget (for 2019/2020) is calculated on a per-pupil basis, many funding entitlements are on a per-school or per-board basis (Ministry of Education 2019a). 6 6 The bulk of these Pupil Foundational Grants pay the salaries of teachers and teaching staff, and its remaining funds cover textbooks and supplies and computers for the classroom. The other grants are the School Foundation Grant ($1.52 billion) to fund administration staff and supplies, and the twelve Special Purposes Grants (approx. $12.09 billion combined): special-education grants ($3.1 billion), cost adjustment and teacher qualifications and experience grants ($2.83 billion), school-facility operations and renewal grant ($2.5 billion), student transportation grants ($1.1 billion), language grants ($866.8 million), school-board administration and governance grant ($683.0 million), learning-opportunities grants ($514.2 million), geographic-circumstances grants ($214.7 million), continuing education and other programs ($137.9 million), Indigenous-education grants ($80.2 million), safe- and accepting-schools supplements ($49.7 million), and declining-enrolment adjustments ($11.9 million) (Ministry of Education 2019b). Accordingly, there are considerable layers—which amount to costs—in between taxpayers’ dollars and students’ education. And even after controlling for changing prices, costs keep rising despite declining enrolment (Hill, Li, and Emes 2020). Adjusting for inflation, Ontario per-student government-school spending has increased from $11,238 in 2006–7 to $13,894 in 2016–17, or 23.6 percent, of which 83 percent is due to increased public-school-teacher and staff compensation, despite a 4.6-percentagepoint decline in public-school enrolment. 7 7 Author’s calculations based on MacLeod and Emes (2019) and Hill, Li, and Emes (2020).

In light of COVID-19, how much value has each student seen for taxpayers’ $13,894? This is not a criticism of teachers (at all!), as their job has never been more challenging and demanding. But, for the Ministry of Education and the taxpaying electors it is accountable to, this is a critical question. Independent schools responded faster to the crisis, not only because they are nimble, but because they are profoundly accountable to parents. They cannot risk a slow or insufficient response, as at any time their parents can walk away and take their funds with them. Parents of students at government-run schools do not have that luxury—nor do taxpayers.

Public Policy Problem

The public policy problem to address is threefold. The Ontario school system and its government-run schools are (1) inflexible and (2) inequitable, and (3) the Ministry of Education’s funding model and the allocation of its resources are inefficient.

Importantly, the policy problem is a public—as opposed to private—one, as K–12 education is a merit good: It has spillover effects that positively affect all of society, not just the individual students being educated, their families, or their school communities. In other words, K–12 education has public benefit and thus is in the public interest, even when administered independent of the state.

So how can Ontario move toward a more flexible, equitable, and efficient education ecosystem?

Toward a Robust Pluralistic Educational Ecosystem

Before looking at the policy recommendation, the first step in addressing the policy problem is to understand what is being done effectively elsewhere and to understand where the problem is already being addressed in Ontario.

Moving from School System to Education Ecosystem

To begin, it is necessary to embrace a fresh perspective on how to view education, starting with lessons from Europe.

Learning from Europe: Educational Pluralism Is the Norm

Taxpayer support for diverse learning and educational pluralism is the democratic norm around the world, and for good reason. For example, in many European nations—and Finland, most notably— online and blended learning are viewed as “another arrow in any teacher’s pedagogical quiver” (Barbour 2014, 37).

Using Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) data, the OECD (2017b) finds that in the advanced countries where non-government-managed schools receive greater proportions of taxpayer funding, the socioeconomic disparities between government and non-government schools disappears. A robust and pluralist educational system in which non-government-run schools are present is a driver of economic equality. In other words, when there is a greater quantity and variety of fully taxpayer-funded, non-government-managed K–12 education options, the differences between advantaged and disadvantaged populations narrows.

Europe has many examples of this, including countries that are considered highly progressive, such as the Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, and the Slovak Republic. Over 90 percent of their “private” school funding comes from taxpayers, and these schools are not only highly heterogenous in terms of pedagogy, curriculum, and family background, but the difference in socioeconomic profiles between them and government-run schools is practically nonexistent. The difference in socioeconomic profiles is increasingly pronounced in OECD nations with less taxpayer funding for non-government schools, such as Belgium, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, and Slovenia. True to this relationship, in Mexico, where non-government schools receive less than 1 percent taxpayer funding, socioeconomic disparities between school sectors is extreme.

The Netherlands is probably the best example for summarizing the aforementioned findings. There, schooling is primarily a function of civil society rather than of the state, and non-government schools are nearly fully funded (Casagrande, Pennings, Sikkink 2019). Educational pluralism is the unchallenged norm, and Dutch students are not only high performers; they are also some of the world’s happiest (OECD 2017a; World Health Organization 2017; 2012; UNICEF 2013).

In short, an educational system in which independent schools emerge as an organic expression of civil society and robust parental decisions are structurally embedded in government policy is a key tool for the reduction of inequality.

Embracing Imagination in Clarifying Language

A current controversy is how to define independent schools, brought to light by the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS). Are they public institutions, as indicated in the federal government’s announcement (Government of Canada 2020)? Are they businesses? By default, the latter is how the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Labour, and municipalities treat them, as—unlike other provinces— Ontario’s Education Act does not define independent schools (Allison et al. 2019). Public institutions and business enterprises, however, are opposites, and yet both definitions are used to deny funding students at non-government schools. And neither term accurately captures what independent schools do for students and for the public.

It is worth remembering: Whether government-run or independent, all K–12 education is in the public interest and for the common good. As such, the following terminology warrants re-imagining, within a more integrated framework that views all education through a public-good lens.

Government Schools

All K–12 education, whether provided by government directly, or emerging out of civil society, is public education, as it is compulsory, regulated by and accountable to the Ministry of Education, and for society’s good. Within public education, there are two types of schools: government and nongovernment. Accordingly, the former should be called just that: “government” schools, not “public” schools.

Independent Schools

Very few independent schools are bastions of privilege, but this misinformed stereotype is the image “private school” invokes. Both the connotation and actual term, “private,” are inaccurate. Nothing is private about Ontario’s independent schools. There are at least two additional reasons to the three aforementioned.

First, Ontario independent schools may have selection criteria, but they are not socially exclusive. The overwhelming majority of Ontario parents find it easy to discover (78%) and enrol (91%) in their preferred independent school. And even religious independent schools welcome non-religious students (Van Pelt, Hunt, and Wolfert 2019).

Second, decades of research, most notably the six Cardus Education Survey data sets, 8 8 For a few examples, see Pennings et al. (2014), Casagrande et al. (2019), and Berner et al. (2019) show that independent-school (and homeschool) graduates are consistently and significantly more active in their local community and a wide variety of civic activities—volunteering, charitable giving, voting, visiting the local library, and more. The most public, least privatized Ontarians are independent-school students, parents, and graduates.

Charitable Sector

Although the Ministry of Education treats Ontario’s non-government schools as businesses, as they may be for-profit, the reality is that most independent schools in Ontario have non-profit status, with the majority being registered charities. Accordingly, Ontario’s independent schools should be viewed in this light, as not-for-profit charities, and thus ought to qualify for the CEWS grant and similar programs.

In summary, near fully funded taxpayer support for diverse learning and educational pluralism is the democratic norm in progressive nations in Europe. As their PISA data shows, an educational system in which independent schools and robust parental choice are structurally embedded in government policy is a key tool for the reduction of inequality. Moreover, given that most Ontario independent schools are charities and their graduates have a track record of robustly contributing to the public good, it is time to include independent schools in Ontario’s conception of taxpayer-funded education.

Understanding Independent Schools

In Ontario, independent schools (still referred to in legislation as “private” schools) are defined as an institution that provides daytime instruction in elementary or secondary school courses to five or more school-aged students and that operates independently of the Ministry of Education. These schools, which can operate as non-profit organizations or as businesses, are required to comply with the legal requirements established by the Education Act but can set their own policies and procedures (Ministry of Education 2018). 9 9 Independent schools offering the Ontario Secondary School Diploma are inspected by the Ministry of Education for compliance with Ministry credit-granting requirements, while non-inspected schools, mostly elementary schools, operate with few regulatory constraints

Ontario independent schools receive no provincial funding, unlike their counterparts in the other five largest and economically competitive provinces in Canada. British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Quebec all provide qualifying independent schools with partial funding equivalent to, on average, 50 percent of the government-run schools’ annual per-student operating costs (Van Pelt, Hasan, and Allison 2017).

Number of and Enrolment at Independent Schools

As of April 27, 2020, there are 1,423 independent schools in Ontario (Ministry of Education 2020d), a sharp increase of 21 percent in three years. But for comparison’s sake, given incomplete and limited access to enrolment data, 2016–17 is used as the most recent year for analysis. From 2006–7 to 2016– 17, the number of independent schools increased from 821 to 1,179, up nearly 44 percent (Ministry of Education 2019c). 10 10 Data include First Nations and overseas secondary and combined schools. First Nations and overseas schools at the elementary level do not report to the Ministry. During the same period, the number of government-run schools remained relatively static, declining 1 percent, from 3,247 to 3,209 schools. 11 11 Excluding hospital programs and Provincial Schools; care and/or treatment, custody, and correctional (CTCC) facilities; and continuing education.

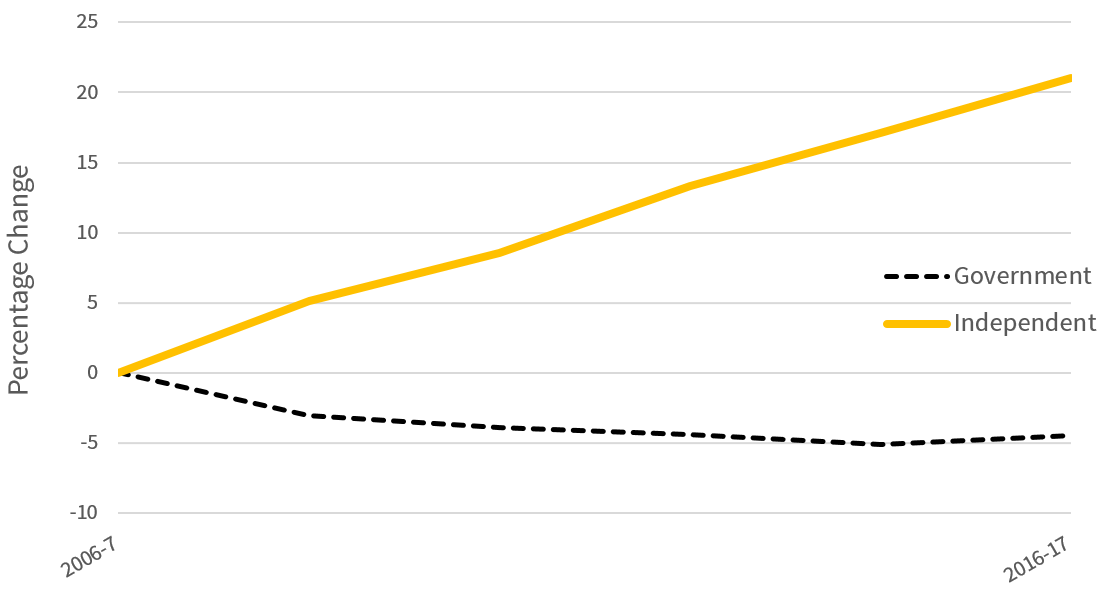

Similarly, as presented in figure 1, enrolment at Ontario’s independent schools has steadily increased from 114,375 in 2006–7 to 138,412 in 2016–17, or 21 percent, while government-run-school enrolment has declined over 4 percent, from 1,431,785 to 1,368,125 students over the same period (Ministry of Education 2019c).

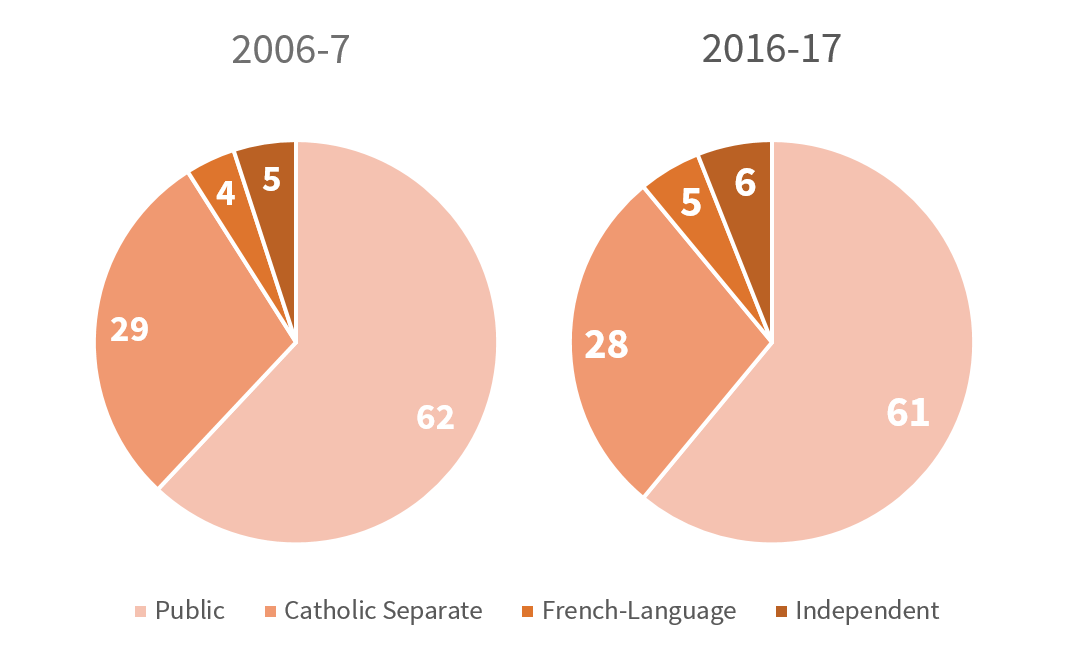

The share of total provincial enrolment of both sectors has also followed the same divergent trend, increasing and decreasing by approximately one percentage point, respectively, as shown in figure 2. Independent-school enrolment has increased from 5 to 6 percent of total provincial enrolment, compared to government-run schools’ decline from 62 percent to 60.8 percent, in 2006–7 and 2016– 17, respectively (Ministry of Education 2019c). Figure 2 also includes fully funded Catholic separate schools and French-language schools, revealing the full distribution by sector across the province.

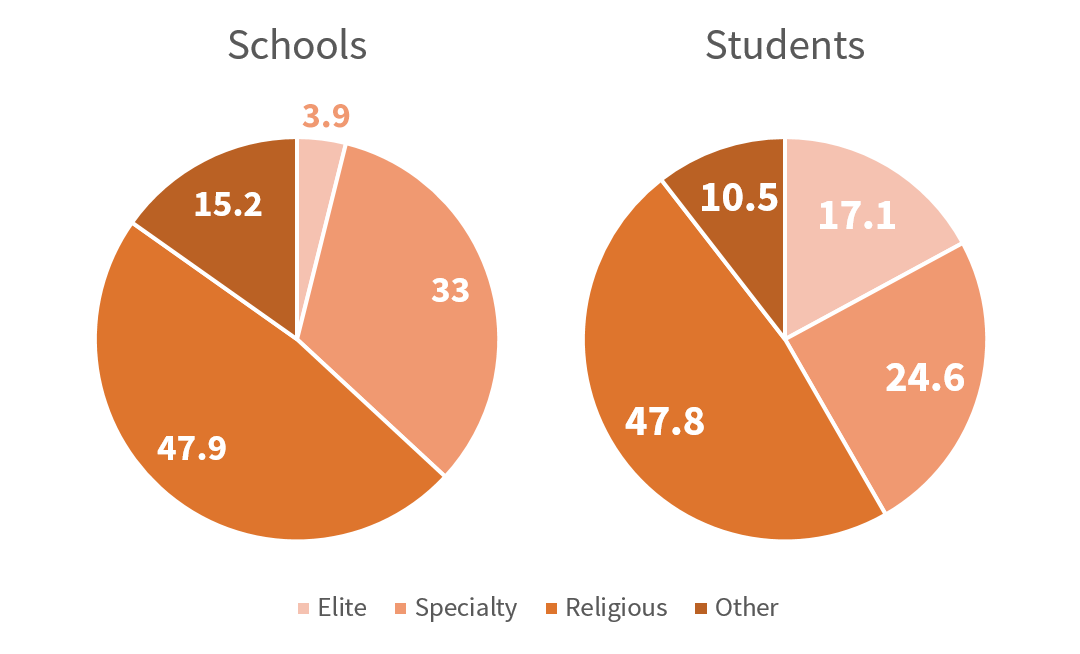

Types of Independent Schools

Ontario’s independent school landscape is characterized by its deep diversity. Figure 3 displays that nearly half of Ontario’s independent schools (48%) and independent-school enrolment (48%) are religious schools. Of these, the majority (61%) attend independent Christian schools (mostly non-Catholic), followed by Jewish (20%), Islamic (18%), and other religious schools (2%). One-third of Ontario’s independent schools, representing a quarter of the sector’s enrolment, are “specialty” schools emphasizing a unique pedagogical approach, including Montessori (54% of specialty enrolments), special education (8%), distributed learning (4%), Waldorf (4%), and various others. Less than 4 percent of Ontario’s independent schools and 17 percent of independent-school enrolment are at Canadian Accredited Independent Schools (CAIS)—premier schools known for their excellence in university preparation, distinguished alumni, and high tuition. Put differently, 96 percent of Ontario independent schools and 83 percent of independent-school enrolment are at non-elite schools (Allison, Hasan, and Van Pelt 2016).

Who Chooses Independent Schools

Not only are the prevailing elitist stereotypes of Ontario independent schools inaccurate, but so are the many assumptions and popular myths surrounding the families attending independent schools. Three out of four parents with a child in an Ontario independent school attended a government-run school themselves, and six in ten did so exclusively. In other words, the overwhelming majority of students in the sector are first-generation independent schoolers. In fact, over one-third of students first attended a government-run school before enrolling at their independent school. Moreover, independent-school parents largely work typical middle-class jobs. For example, they are twice as likely as average Ontarians to be teachers or nurses. Also, more than two-thirds made major financial changes to afford the cost of tuition (Van Pelt, Hunt, and Wolfert 2019). 14 14 Although many independent schools provide bursaries for students from low-income households, the reality is that tuition at Ontario independent schools is double that of their BC peers and nearly triple the average Alberta independent-school tuition, due to Ontario’s unique lack of taxpayer funding for independents. However, even with abnormally high tuition, few independent-school families are wealthy (Van Pelt, Hunt, and Wolfert 2019; Hunt and Van Pelt 2019; Hunt and Van Pelt forthcoming).

Why Parents Choose Independent Schools

Based on representative surveys of independent-school parents in Ontario, BC, and Alberta, there is a seemingly endless variety of motivations for choosing an independent school, and this reflects the diversity of parents choosing them (Van Pelt, Hunt, and Wolfert 2019; Hunt and Van Pelt 2019; Hunt and Van Pelt forthcoming). Yet, the top two reasons are identical in the three provinces for which we have data. Parents choose their independent school because they believe their independent school is a safe school and offers a supportive, nurturing environment for students. In Ontario specifically, the following are the top five reasons for choosing an independent school (Van Pelt, Hunt, and Wolfert 2019):

- This is a safe school.

- This school offers a supportive, nurturing environment for students.

- This school emphasizes character development.

- We trust the curriculum at this school.

- This school has outstanding teachers.

But perhaps most importantly, 93 percent of Ontario independent-school parents are highly likely to recommend their school—the highest of the three provinces surveyed (Van Pelt, Hunt, and Wolfert 2019).

How Independent Graduates Are Different

We have even more data on independent-school graduate outcomes. The following are some of the characteristics that differentiate graduates of independent schools from government-run schools, based on the findings of the Cardus Education Survey (Pennings et al. 2012; 2014; Green et al. 2016; 2018a; 2018b):

- More engaged: Independent-school graduates participate in more neighbourhood and community groups as well as in arts and culture initiatives.

- More generous: They volunteer and give more of their financial resources than their government-school peers, to a wide variety of causes.

- More focused on neighbour: Evangelical-Protestant-school graduates, in particular, contribute to the common good in a culture in which they express feeling unwelcome. Regardless, they are committed to constructively engaging with the culture and contributing to it.

- Express their identity through their work: Graduates of independent non-religious schools are more likely to hold higher-status employment positions, and they have a wide variety of fulfilment expectations of their job, such as that it be helpful, creative, worthwhile, and relational. Graduates of Evangelical Protestant schools (and of religious homeschooling) have a strong sense of vocational calling and seek jobs that fulfil that calling. (In terms of religiousfamily homeschoolers, while the most likely to have high school as their highest credential, they are also the most likely to earn a PhD or advanced professional degree.)

- Graduates are highly satisfied with the independent schools they attended. Even with fifteen or so years of hindsight, independent-school graduates evaluate their school cultures positively, claiming them to be close knit and expressing a high regard for teachers, students, and administrators. They reflect that their independent school offered good preparation for post-secondary education, as well as for later life.

- Stronger families: Graduates of independent schools are less likely to be divorced or separated. This is particularly important for the future of education in Ontario, as children from intact homes perform significantly better in school, regardless of socioeconomic background (Jeynes 2015).

In summary, despite myths to the contrary, at least 96 percent of Ontario “private” schools are not bastions of privilege. Independent-school parents are typically middle-class Canadians who choose their independent school for its safety, nurturing environment, and a variety of other reasons unique to each particular family. Independent schools—and religious independent schools, in particular—do not threaten civic formation but actually form thoughtful graduates who are more likely to be civically minded, committed to personal growth, and contributors to the public good.

Given the evidence, how might the Ontario government make more space for graduates of this sort to emerge, and for increased diversity in the Ontario education system?

Policy Recommendation: Innovation through Direct Education Assistance (IDEA)

The Ontario Government’s March 25 announcement of the Support for Families payment of $200 per child (and $250 for special needs) is a step in the right direction, as it is the first time in decades that the provincial government’s approach treats children in independent schools as equal to children in government schools (Ministry of Education 2020c). The type of school a student attended before the pandemic does not affect a child’s eligibility for this benefit. Although the earlier Support for Parents program 15 15 The Support for Parents program financially supported parents when government-run schools were closed due to the 2019–20 labour strike. did not include independent schools (Ministry of Education 2020a), the idea of directing funds to parents to assist them in supporting their child’s learning is a concept to expand on in welcoming diversity in the education ecosystem.

Looking beyond these one-time reliefs and the challenges of the lockdown, this concept should be expanded considerably to address the policy objectives of flexibility, equity, and efficiency.

IDEA Program

Specifically, the Ministry of Education should establish an Innovation Through Direct Education Assistance (IDEA) program that routes education funds directly to parents 16 16 The term “parents” refers to parents, guardians, and caregivers. to support their child’s education. IDEA funds can have multiple uses but will be restricted to the purpose of education, such as independent-school tuition, personal tutoring, online courses or subscriptions, software and learning equipment (e.g., computer), therapies for special needs, field trips and extracurricular activities, textbooks, and other educational materials. Parents will receive an IDEA Handbook (also available online) that details eligible and ineligible expenses. Basic eligibility in the program should include all Ontario school-aged children, regardless of school attended, but require opting in, with funding particularly targeting students from low-income families or with special needs.

Funding

All school-aged Ontarians should be eligible for basic IDEA funding, with a rising scale tied to household earnings, as well as additional benefit for special needs. Basic IDEA funding should be one-third of the per-pupil average, 17 17 An average $13,894 per pupil is the most recent estimate (Hill, Li, and Emes 2020). or $4,630 per student, 18 18 $4,630 is lower than all Pupil Foundation Grant amounts (i.e., the basic per-pupil allocations). with a maximum of $12,500 for students in deep poverty, 19 19 $12,500 or 75 percent of household income, whichever is lower. and up to a maximum of $45,000 for students with physically dependent or deaf/blind special needs. 20 20 To help ensure no additional costs burden taxpayers, IDEA funding should be formulaically simple and set to a maximum of 90 percent of existing allocations (which allows for administrative expenses and a sizeable margin of safety). The income-targeted maximum should then be reduced by 10 percent of the greater of individual adjusted net income over $30,000 or adjusted family net income over $60,000 (similar to Ontario’s Low-income Individuals and Families (LIFT) Tax Credit calculation), resulting in only households with less than approximately $78,700 household income qualifying for any of the income-targeted supplement in addition to the basic $4,630 funding.

For comparison, the BC government spends an average $2,015 less per student than Ontario 21 21 Per-pupil spending in government-run schools is $13,894 in Ontario and $11,879 in BC (Hill, Li, and Emes 2020, 8). $13,894 - $11,879 = $2,015. and yet, on average, BC independent schools receive approximately $5,050 per student in taxpayer funding for operating expenses. Moreover, all BC special-needs students receive full funding, regardless of school attended (Hunt and Van Pelt 2019, 12).

Ontario students with special needs should be equally respected and receive full funding to support them in identifying and experiencing the best possible education for their unique needs—whether at an independent school, blended learning co-op, or entirely new innovation. 22 22 Special-education and income-targeted supplements should not be mutually exclusive. A student in deep poverty with physically dependent or deaf/blind special needs should qualify for up to the maximum of both supplements.

IDEA Accounts

In terms of distributing funds, although they could be directly deposited into parents’ existing bank accounts—similar to the approach taken for the Support for Families and Support for Parents programs—we recommend the IDEA program use specially designated government-authorized bank accounts, called IDEA Accounts. The account can only be used for allowable education expenses for K–12 and post-secondary. There are at least three reasons for this:

- A government-authorized bank account will give the most marginalized families access to this funding. As with high-speed internet, although nearly all Ontario households have bank accounts, some do not, and those without access to banking (or the internet) are those who are most likely on the margins (Dijkema and McKendry 2015; Hunt et al. 2018).

- The use of only a debit card or online equivalent for payment of allowable education expenses from one designated and exclusive bank account will make tracking expenses much easier for parents and auditors. This will also strongly alleviate misuse or abuse of resources, in addition to requiring parents to have proof of all education expenditures and submit receipts for regular random audits.

- A designated savings account incentivizes efficient use of funds, and so long as post-secondary education is an eligible expense (as it should be), this has the additional benefit of encouraging families to save for their child’s post-secondary education who otherwise could not afford to.

Incentivizing efficient use of education resources is critical for saving taxpayer dollars and saving for post-secondary, but it also has the added benefit of encouraging good habits and helping mitigate the risk of artificially inflated independent-school tuition. It is also worth noting that incentivizing efficient use of pre-existing K–12 resources to fund post-secondary education is a quadruple win, as it (1) increases post-secondary opportunity for students (particularly for low-income families), 23 23 IDEAs, in addition to improving the K–12 experience of disadvantaged students, will help improve their post-secondary opportunities. Currently, low-income households are less likely to participate in Canada’s Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP) program. Even when combining middle-income and low-income families, the majority do not participate in RESPs, unlike higher-income families. Some have highlighted that this gap is closing, but that is as much a result of fewer higher-income families participating in RESPs. From 2008 to 2018, low- and middle-income families’ participation increased and higher-income families’ participation decreased by an identical 17.5 percentage points (Government of Canada 2019). (2) stretches provincial budget dollars for K–12 and advanced education, (3) strengthens the economy by investing in human capital, and (4) benefits society at large (as post-secondary students are more likely to be responsible citizens).

Ecosystem of Pluralistic Education

The IDEA program’s unique advantage is that it allows for innovation within a truly pluralistic ecosystem and welcomes a democratic education model where decisions are made at the citizen level, instead of top-down by state authority, in a relatively non-disruptive, incremental manner. Some recipients, perhaps many, will use their education funds for independent-school tuition. Others may focus more online.

24

24

There is limited methodologically sound research on the effectiveness of online education. From what we know, it is much better for some but not ideal for most. Specifically, online learning works well for highly motivated and/or academically advanced students, but it has the opposite effect for unmotivated and/or struggling students (Hess 2020).

Others may find blended learning—a mix of home-based and in-class instruction—works best. And others may create their own fully tailored educational experience. That is IDEA’s distinctively student-centred nature: it is highly personalized, with maximum flexibility.

25

25

Although the research on mobile learning, and even online learning, is limited, we do know that a student-centred pedagogy that

prioritizes personalizing the learning experience is essential for “creating positive outcomes in the use of technology” (Cavanaugh, Maor, and McCarthy 2014, 391). In embracing the future of education, it is worth highlighting—in addition to the benefits of independent education previously discussed—a synthesis of the empirical research on “anytime, anywhere learning” or K–12 learning with mobile devices. Cavanaugh, Maor, and McCarthy (2014) found from 2010 to 2013:

• The highest educationally performing countries integrate mobile devices into education.

• There is a strong link between a country’s internet usage, spread of broadband access, and GDP.

• In a mobile-learning setting, students become “collaborators in designing their own learning process.”

• And, “as students become independent learners, they become more prepared in the skills needed for college and in their careers.”

In summary, we recommend the Ontario government introduce the IDEA program to route participating students’ education funds directly to support their unique educational needs, with a particular funding emphasis on students from low-income households and students with special needs. 26 26 The IDEA program is based largely off Dan Lips’s (2005) concept and the body of literature it has spawned.

For Further Consideration

To further address the issue of low-income families’ inability to afford independent-school tuition, the Ontario government can introduce a corporate-sector tax credit to fund independent-school scholarship programs for socioeconomically disadvantaged students, to eliminate the financial barrier to enrolment. By allowing businesses (and individual donors and couples) to make dollar-for-dollar tax-deductible contributions to independently operated, non-profit scholarship-granting organizations, students currently without access to independent schools can gain access without any additional taxpayer burden. Where similar programs have been tried, they yield $1.44 in private funding for every dollar of forgone corporate income-tax revenue.

Conclusion

Not all students learn the same way, and not all kids fit in. This is why it is critical to have a robust education ecosystem of diverse delivery systems, as well as to re-imagine how we understand the K–12 education experience. Specifically, the IDEA program should be introduced to expand and improve Ontario students’ educational options, from home-based and blended learning to independent schooling. A decade of sound research shows that increased independent-school enrolment will produce graduates who are more civically minded and committed to personal growth and contributing to the public good. Moreover, for a wide variety of reasons, independent-school graduates and parents of current students are overwhelmingly likely to recommend their independent school. On average, they are highly satisfied with their independent-school experience. Should not more Ontarians have the opportunity to share in this positive experience?

References

Allison, D.J., P. Allison, B. Bierman, J. Cook, A. Dervaitis, T. Kamphuis, and M. Van Pelt. 2019. Modernizing and Streamlining Ontario’s Education System: Cutting Red Tape, Removing Barriers. Burlington: Edvance.

Allison, D.J., S. Hasan, and Van Pelt, D. N. 2016. “A Diverse Landscape: Independent Schools in Canada.” Fraser Institute.

Barbour, M.K. 2014. “A History of International K–12 Online and Blended Instruction.” In Handbook of Research on K–12 Online and Blended Learning, edited by R. E. Ferdig and K. Kennedy, 25–49. Pittsburgh: ETC Press.

BC Ministry of Education. 2019. “Operating Grants Manual 2019/20.” Resource Management Division. Government of British Columbia.

Berner, A., D. Bradford, and R. Pennings. 2019. “Making the Public Good Case for Private Schools.” Cardus.

Casagrande, M., R. Pennings, and D. Sikkink. 2019. “Rethinking Public Education: Including All Schools that Contribute to the Public Good.” Cardus.

Cavanaugh, C., D. Maor, and A. McCarthy. 2014. “K–12 Mobile Learning.” In Handbook of Research on K–12 Online and Blended Learning, edited by R. E. Ferdig and K. Kennedy, 391–413. Pittsburgh: ETC Press.

Dijkema, B., and R. McKendry. 2015. “Banking on the Margins: Finding Ways to Build an Enabling SmallDollar Credit Market.” Cardus.

Government of Canada. 2019. “Canada Education Savings Program—2018 Annual Statistical Review.” Employment and Social Development Canada.

———. 2020. “Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS): Who Is an Eligible Employer?” May 12. https:// www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/subsidy/emergency-wage-subsidy/cews-whoeligible-employer.html.

Green, B., D. Sikkema, and D. Sikkink. 2018a. “Cardus Education Survey: British Columbia Bulletin.” Cardus.

———. 2018b. “Cardus Education Survey: Ontario Bulletin.” Cardus.

Green, B., D. Sikkema, D. Sikkink, S. Skiles, and R. Pennings. 2016. “Cardus Education Survey: Educating to Love Your Neighbour: The Full Picture of Canadian Graduates.” Cardus.

Hart, D., and A. Kempf. 2018. “Public Attitudes Toward Education in Ontario.” Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto (OISE).

Hess, F. M. 2020. “Is Remote Learning Better?” National Review, May 6. https://www.nationalreview. com/2020/05/education-remote-learning-effectiveness-depends-on-motivation-of-students/.

Hill, T., N. Li, and J. Emes. 2020. “Education Spending in Public Schools in Canada.” Fraser Institute.

Hunt, D., and D. Van Pelt. 2019. “Who Chooses Independent Schools in British Columbia and Why?” Cardus.

———. Forthcoming. “Preliminary Results: Who Chooses Alberta Independent Schools and Why?” Cardus.

Hunt, D., N. Lodewyk, S. Barsen, L. Minderhoud, K. Filipic, and M. Wood. 2018. “From Dependency to Sustainability: Reforming Payday Lending in British Columbia.” Simon Fraser University.

Jeynes, W. 2015. “A Meta-analysis on the Factors That Best Reduce the Achievement Gap.” Education and Urban Society 47, no. 5:523–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124514529155.

Lecce, S. 2020a. “March 24, 2020: Minister Launches Phase 1 of Learn at Home.” Government of Ontario, March 24. https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education#section-2.

———. 2020b. “March 31, 2020: Minister’s Letter on Phase 2 of Learn at Home.” Government of Ontario, March 31. https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education#section-1.

———. 2020c. “April 28, 2020: Minister’s Letter on Phase 2 of Learn at Home.” Government of Ontario, April 28. https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education#section-0.

Lips, D. 2005. Policy Report No. 207. Goldwater Institute.

MacLeod, A., and J. Emes. 2019. “Education Spending in Public Schools in Canada.” Fraser Institute.

Miller, J. 2019. “Rich School, Poor School: Private Money Affects Ottawa’s Public Education System.” Ottawa Citizen, August 8. https://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/rich-school-poorschool/.

Ministry of Education. 2018. “Private Elementary and Secondary Schools.” Government of Ontario. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/privsch/#requirements.

———. 2019a. “2019–20 Education Funding: A Guide to the Special Education Grant.” Government of Ontario.

———. 2019b. “2019–20 Education Funding: A Guide to the Grants for Student Needs.” Government of Ontario. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/funding/.

———. 2019c. “Quick Facts: Ontario Schools, 2016–17.” Government of Ontario. http://www.edu.gov. on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/quickfacts/2016_2017.html.

———. 2020a. “Education Contract Talks: Stay Updated.” Government of Ontario, May 12. https://www. ontario.ca/page/education-contract-talks-stay-updated.

———. 2020b. “Get Support for Families.” Government of Ontario, April 24. https://www.ontario.ca/ page/get-support-families.

———. 2020c. “Learn at Home.” Government of Ontario, May 12. https://www.ontario.ca/page/learnat-home.

———. 2020d. “Private School Contact Information.” Government of Ontario. https://www.ontario. ca/data/private-school-contact-information?_ga=2.62177903.218285855.1563499740- 1885849427.1519762790.

OECD. 2017a. “PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being.” doi:https://doi. org/10.1787/19963777.

———. 2017b. “School Choice and School Vouchers: An OECD Perspective.”

Office of the Premier. 2020. “Health and Safety Top Priority as Schools Remain Closed.” Government of Ontario, May 19. https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2020/5/health-and-safety-top-priority-asschools-remain-closed.html

Pennings, R., D. Sikkink, A. Berner, J. W. Dallavis, S. Skiles, and C. Smith. 2014. “Cardus Education Survey: Private Schools for the Public Good.” Cardus.

Pennings, R., D. Sikkink, D. Van Pelt, H. Van Brummelen, and A. von Heyking. 2012. “Cardus Education Survey: A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats.” Cardus.

Sarlo, C. A. 2019. “The Causes of Poverty.” Fraser Institute.

Statistics Canada. 2020. “COVID-19 Pandemic: School Closures and the Online Preparedness of Children.” April 15. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00001- eng.htm.

Toronto District School Board. 2020. “Financial Facts: Revenue and Expenditure Trends.” April 15. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/About-Us.

UNICEF. 2013. “Child Well-Being in Rich Countries: A Comparative Overview.”

Upper Canada District School Board. 2020. “Board Map.” http://www.ucdsb.on.ca/for_families/ucdsb_ schools/board_map.

Van Pelt, D., D. Hunt, and J. Wolfert. 2019. “Who Chooses Ontario Independent Schools and Why?” Cardus.

Van Pelt, D., R. Pennings, and T. Jackson. 2019. “Funding Fairness for Students in Ontario with Special Education Needs.” Cardus.

Van Pelt, D., S. Hasan, and D.J. Allison. 2017. “The Funding and Regulation of Independent Schools in Canada.” Fraser Institute.

World Health Organization. 2012. “Social Determinants of Health and Well-Being Among Young People.”

———. 2017. “Adolescent Obesity and Related Behaviours.”