Executive Summary

Education funding reform is long overdue for students with special needs in Ontario. Currently education funding for students with special education needs is based on the school attended rather than the special needs of the child. Unlike health funding in Ontario which is based on the needs of the student and follows the student into their school regardless of the type of school attended, education funding is based on the type of school the student with special needs attends.

Currently students with special needs receive special education funding only if they attend a public government school. Students whose parents choose an independent non-government school for their children with special needs—often because the school more closely aligns with the family’s religious, philosophical or pedagogical convictions—are barred from receiving education funding for their special needs.

One in five schools in Ontario is an independent school and 6.4 percent of students in Ontario attend independent schools; currently over 138,000 students attend one of Ontario’s 1,285 independent schools. Just under half of the independent schools are religiously-oriented, the remainder operate with a distinct pedagogical or philosophical orientation.

In this paper we calculate the expenditure required for funding reform for students with special education needs who attend an independent non-government school.

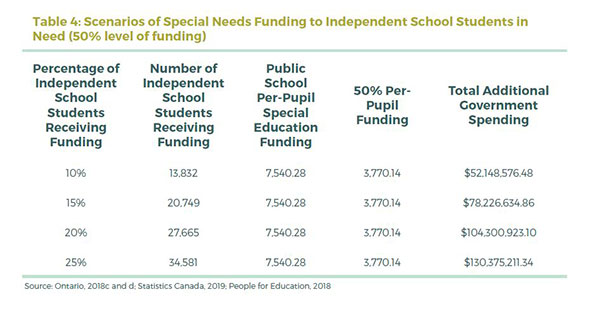

If funding were at 75 percent of the per pupil allocation for students in public government schools, the expenditure required would be between $78 and $195 million, depending on the share of students in the schools that require special education funding. If the funding were at 50 percent of the public school per pupil allocation, the expenditure required would be between $52 and $130 million,

Fortunately, implementation of the necessary corrections of moving from school-based to needs-based funding aligns with current government values and priorities. Furthermore, family resilience, so necessary for families caring for societies’ most vulnerable members, increases when children are educated within a supportive school community that aligns with their family’s values. This funding reform will enhance family resilience.

Not only are the funding reforms needed consistent with government priority of protecting the most vulnerable in our communities and for efficient and effective value in all government spending, it is a demonstration of respect for the inherent dignity of all students with special needs in Ontario.

Introduction and Background

Funding reform is long overdue for students with special needs in Ontario. Fortunately, the necessary—and overdue—reforms align with the provincial government’s values and priorities.

Current education funding for Ontario students with special needs depends on the school students attend. Specifically, education funding for students with special needs (also called exceptional students) is only available for students who attend government schools (that is, English public, French public, English Catholic, and French Catholic). Exceptional students who attend non-government schools are not eligible to receive education funding for their special education needs.

This unfairly penalizes the most vulnerable in our communities. Students whose families follow their conscience rights in selecting a school for their children that more closely aligns with their religious, pedagogical or philosophical convictions are barred from receiving education funding for their special education needs.

Correcting this unfair practice, as this paper demonstrates, will require modest spending. Not only will this expenditure restore equity and choice for the families who raise and care for Ontario’s most vulnerable citizens, but it will also be a practical means for the government to demonstrate its values and priorities: values that include the belief “that taxpayers should be respected, and that the role of government is to help those who need it most and to protect the most vulnerable in our communities” (Ministry of Finance, 2018a, p. vii), and priorities that include value, effectiveness and efficiency for all spending. 1 1 The government has committed to examining spending practices “to identify ways the government could transform programs and services to ensure sustainability and value for money” (Ministry of Finance, 2018b, p. 3). It claims that its actions have already included “making existing government programs more effective” (p. 3) through providing families more choice in at least two program areas (child care and autism). It has “found savings and efficiencies, while giving individuals, families and businesses important tax relief” (p. 3) and it is taking action “to make programs and services more efficient” (p. 3).

Providing the special education needs funding correction proposed here will also further align the government’s practices with the recent statement from the Ontario Human Rights Commission as well as the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2 2 Details of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities see: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html . The Policy on Accessible Education for Students with Disabilities by the Ontario Human Rights Commission makes reference to the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities stating it is an international treaty designed to “promote, protect, and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity.” Making the changes proposed in this brief would further align Ontario’s spending towards adequate and appropriate community supports and accommodations allowing for equal opportunities for students with disabilities and respect for their inherent dignity. 3 3 See, for example, page 15 of Ontario Human Rights Commission (March 2018). Policy: Accessible Education for Students with Disabilities located at http://www.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/Policy%20on%20accessible%20education%20for%20students%20with%20disabilities_FINAL_EN.pdf.

Independent Schools in Ontario

Almost one in five schools in Ontario is an independent school 4 4 The Education Act and government policy typically refers to these schools as “private schools” although in popular nomenclature they are know as “independent schools” because they are owned and operated independent of government agencies. On occasion they are called non-government schools (NGSs). . Ontario has more students being educated in independent schools than any province in Canada, and parents are increasingly turning to the independent school sector for the education of their children. More than half of Ontario independent schools are non-religious schools with unique pedagogical visions while 48 percent have a religious orientation. 5 5 Allison, D.J., Hasan, S., & Van Pelt, D.A. (June 2016). A Diverse Landscape: Independent Schools in Canada. Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute. Located at:

https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/a-diverse-landscape-independent-schools-in-canada Almost 5 percent of all independent schools in Ontario are established solely to serve students with special needs, and they enrol about 2 percent of independent school students. Less than 5 percent of all independent schools in the province are schools that some might traditionally refer to as elite, university-preparatory schools, and they enrol about 17 percent of the province’s independent school students.

Close to half of the independent schools are religiously-defined, while the rest have distinct pedagogical visions. Three-quarters of the religiously-oriented independent schools are Christian schools (a handful of which are Catholic); Islamic and Jewish schools make up the majority of the remaining religiously-defined schools. The non-religious independent schools include schools with a unique learning or academic emphasis often rooted in a distinct educational philosophy such as Montessori, Waldorf, special education, arts, sports or science/technology/engineering/math. 6 6 See Tables 4-9 in Allison, D.J., Hasan, S., & Van Pelt, D.A. (June 2016). A Diverse Landscape:

Independent Schools in Canada. Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute. Located at:

https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/a-diverse-landscape-independent-schools-in-canada

From 2005/06 to 2015/16, public school enrolments in Ontario (including public Catholic schools) declined by 5.9 percent (from 2,118,544 to 1,993,432 students). During those years, the number of public schools stayed virtually the same (from 4,886 to 4891). 7 7 Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2018a). Quick Facts, Ontario Schools, 2015-16. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/quickfacts/2015_2016.html

Over the same period, private school enrolments increased by 12 percent (from 119,584 to 133,919) and the number of schools increased by 24.9 percent (from 895 to 1,118). Recent data show 1,285 independent schools in 2018/19 in Ontario 8 8 Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2018b). Private Schools Contact Information 2018. At: https://www.ontario.ca/data/private-school-contact-information 9 9 , a 43.6 percent increase in just 13 years.

Ontario independent schools are key contributors to the education landscape in this province by providing education to over 138,000 students. Currently 6.4 percent of Ontario students are educated through the independent school sector. As they are almost entirely funded by parents and philanthropists, independent schools save Ontario taxpayers at least $1.8 billion dollars annually. 10 10 Based on average per pupil spending in Ontario of $13,321 (2015/16 spending is the latest data available). See Macleod, A. & Emes, J. (2019). Education Spending in Public Schools in Canada, 2019 Edition. Vancouver, Fraser Institute. At: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/education-spending-in-canada-2019_0.pdf.

Not only do independent schools contribute to the financial well-being of the province, but their graduates, as shown in 2018 research from Cardus, also contribute to the civic and social well-being of the province. 11 11 Green, B., Sikkema, D. Sikkink, D. (2018). Cardus Education Survey 2018: Ontario Bulletin. Located at: https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/cardus-educationsurvey-2018-ontario-bulletin/ Growth in the sector suggests parents are increasingly turning to independent schools for the education of their children.

The Issue

Unfair Funding Allocation. Education funding for children with special needs is unfairly allocated. It is based on the type of school the student attends rather than on the need of the child.

If a child with special needs attends a government school, that is, a public or Catholic school in Ontario, they receive government funding for equipment and services to help them learn, regardless of their disability. This is known as “accommodation” and, by law, all recognized special needs are covered.

By contrast, students with special needs enrolled in a non-government independent school, receive limited funding from Ministry of Health related to specified health-related disabilities; there is no Ministry of Education funding for students with special needs enrolled in a non-government independent school.

For example, while students with special needs in independent schools receive funding (sourced through Ministry of Health) for nursing services, dietetics, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, articulation (speech), they receive no funding (the source of which would be through the Ministry of Education) for learning disabilities, language impediments, deafness, blindness, physical equipment for learning such as cushions, therapy balls, ball chairs, adaptive equipment, nor do they receive funding for learning technology such as desktop computers, laptops, programs such as Kidspiration, Inspiration, Draft Builder, Kurzwell, etc. This restriction also plays out in the allocation of the Special Education Amount funding, as students in independent schools cannot access equipment and services to support their disability.

Indeed, one story we hear from families is that adaptive trays for holding lunch materials such as those used by children with high physical needs are provided (Ministry of Health jurisdiction) but adaptive trays for holding learning materials (Ministry of Education jurisdiction) are withheld from students whose parents choose to send them to a non-government school.

Under the current arrangements, if a student with special needs transfers from a public school to an independent school, they are not permitted to transfer any equipment and services which had been provided, regardless of individualized custom fitting or design. Without even discussing the waste involved in this, this is discrimination based on school choice which disregards the needs of the child.

Furthermore, it is commonplace to see children in independent schools sitting next to each other, one student with a speech impediment who is assisted by permitted government funded equipment and services (because the source is Ministry of Health, and thus not school-dependent, but needs-dependent) and the next student with an auditory processing disorder, who is denied necessary equipment and services (because the source is Ministry of Education, where funding is school-dependent and disregards need).

This is discrimination based on disability. Parents are forced to choose either a school which shares their educational philosophy or faith perspective while their child’s disability may go largely untreated or treated in underfunded ways or a school that does not share their convictions in order for their child to receive services for their disability.

Resilient families. The reasons families choose an independent school for their children vary. The most common reasons cited are quality education, safety, and teacher care. But even more, research has found that parents choose, for example, religiously-oriented schools because of the close co-operation and collaboration with the home. 12 12 See table 2 (p. 23) of Van Pelt, D., Allison, D.J. and Allison, P.A. (May 2007) Ontario’s Private Schools: Who Chooses Them and Why? Vancouver: Fraser Institute. This is essential to recognize because family resiliency is critical for families caring for and raising children with moderate to complex special needs. Communities of belonging that are frequently experienced in independent schools leads to family resiliency over the long term, which is vital to the wellbeing of parents and children with special needs. Family resiliency is undermined when families are essentially forced to send their children with special needs to government schools that do not match their religious, philosophical or pedagogical convictions, or additionally troubling, if they must split their children across schools simply because of the barriers the current arrangement for special education funding places on the family.

Effective and Efficient Schools. In many ways, measured and unmeasured, independent schools are effective. They serve the needs and expectations of families, and this explains continued growth in the sector. They are financially efficient and even in the five Canadian provinces where independent schools receive partial funding (from 35 to 80 percent of the per pupil allocation for a public-school student), the savings to taxpayers because of independent schools is significant.

Certainly, if as this paper proposes, funding for students with special needs who attend non-government schools was at even 75 percent of what is allocated for students with special needs who attend government schools, the financial efficiency and savings test would also be met in this sector.

The Structure of Ontario Public School Special Needs Education Funding

Ontario has been steadily increasing its total funding for special needs education in public schools over the last five years. For the 2018/19 school year, the Ontario government has committed to spending approximately $3 billion on special needs education through the Special Education Grant (see Table 1).

The Special Education Grant is comprised of six different allocations and provided to school boards for funding programs, services, and/or equipment for special needs education (see Table 2). 13 13 This grant can only be used for special education and any unspent funding must be set aside for special education uses in the next school year. Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2018c). 2018-19 Education Funding: A Guide to the Grants for Student Needs. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/funding/1819/GSNGuide2018-19Revised.pdf The two largest components of the grant are the special education per pupil amount (SEPPA) and the differential special education needs amount (DSENA). The SEPPA provides school boards with foundational funding for special needs education, and it is based on a school board’s total enrolment and differential per-pupil amounts. 14 14 There are different per-pupil amounts for grades K-3, 4-8, and 9-12. For example, per-pupil amounts to earlier grades are higher in order to direct more funding to early intervention. While the SEPPA provides a baseline level of funding to all school boards, the DSENA provides additional funding to school boards with the recognition that there is variation across school boards in the share of students with special needs, the nature and degree of those needs, and the capabilities of boards to meet student needs. 15 15 In 2018/19, a new component was added to the DSENA that provides increase support for programs and services students with all special needs, including students with mental health and Autism Spectrum Disorder needs. The other components of the Special Education Grant include allocations for special equipment, students who require more than two full-time staff, in addition to other areas.

Ontario’s special needs education funding for public schools covers a wide variety of purposes, ranging from providing students who need extra help with the resources they require to the provision of specialized equipment and staff to meet student’s needs. The funding is also available both to students who have gone through the province’s formal identification process and those without a formal identification. Students without a formal identification are typically supported through Individual Education Plans (IEPs) and their range of needs vary from needing more time on tests to providing assistance with learning disabilities. 16 16 People for Education (2018). 2018 Annual report on schools: The new basics for public education. At: https://peopleforeducation.ca/report/2018-annual-report-on-schools-the-new-basics-for-public-education/

Students with special needs who have been formally identified through the province’s Identification Placement and Review Committee (IPRC) process have had their needs classified into at least one of five categories, including: behavioural, communicational, intellectual, physical, and multiple. 17 17 Note that the intellectual category includes those students identified as being ‘gifted’ in that they have “an unusually advanced degree of general intellectual ability”. Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2017). Special Education in Ontario: Policy and Resource Guide. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/document/policy/os/onschools_2017e.pdf Students that have gone through the formal identification process tend to be those with higher needs. 18 18 Ibid., People for Education (2018).

Based on a number of different sources, the share of students receiving funding from the special education grant who have formally versus informally identified needs has varied over time. For example, a 2010 report from Ontario’s Auditor General revealed that, of students receiving special education services, approximately 68 percent were those who are formally identified and only about 32 percent were non-identified. 19 19 Almost 10 percent of identified students receiving funding were classified as gifted. Auditor General of Ontario (2010). Chapter 4, Section 4.14: Special Education. At: http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en10/414en10.pdf In more recent years, the share of funding being received by students not formally identified has increased, possibly reflecting a greater priority for students who have not been formally identified by the province’s process to receive the help they need in a timely manner. According to government figures, in the 2012/13 school year 56 percent of funding went to students who had been formally identified as “exceptional” by an IPRC, while the remaining 44 percent of students receiving special needs funding had not been formally identified. 20 20 In 2012/13, 9.18 percent of all students had been formally identified as “exceptional” and were receiving funding, while a further 7.14 percent of all students were also receiving special needs educational programs or services. Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2014). Support Every Child, Reach Every Student: An Overview of Special Education. At: http://www.ldao.ca/wp-content/uploads/Special-Education-Overview-Oct-2014.pdf By 2014/15, only 52 percent of students receiving special needs educational resources were formally identified as being “exceptional”. 21 21 Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2019). An Introduction to Special Education in Ontario. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/speced/ontario.html To be clear, it is not necessarily negative that students who have not been formally identified as being “exceptional” are making up a larger share of students receiving funding but rather the broader inclusion of special needs programs and services likely explains some of why the share of the total student body receiving such funding has been rising over time as discussed below.

Indeed, it is important to understand how many public-school students are receiving funding from the Special Education Grant in totality. In general, data on this issue appear to be few and far between. One publicly available estimate from the Ontario government for the 2014/15 school year indicated that 17 percent of students were receiving funding from programs or services stemming from the Special Education Grant. 22 22 Nine percent of all Ontario students receiving special education funding were identified as exceptional and eight percent were not. Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2019). An Introduction to Special Education in Ontario. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/speced/ontario.html Another indicator as to the share of Ontario public school students receiving special education funding comes from the public school advocacy group, People for Education. 23 23 People for Education (2018). 2018 Annual report on schools: The new basics for public education. At: https://peopleforeducation.ca/report/2018-annual-report-on-schools-the-new-basics-for-public-education/ The group surveyed Ontario principals in 2018 and found that, on average, 17 percent of students in elementary schools and 27 percent of students in secondary school students received special education funding. 24 24 Ibid. Combining these estimates with forecasts of enrollment for 2018/19, a little over 20 percent of Ontario public school students were receiving some form of special education support. This means that the per-special needs student funding for the Ontario public school system in 2018/19, based on the approximately $3 billion in special education funding, was $7540.28 per student. Given that these estimates of the share of students receiving special needs funding are the most recent we could find, they serve as the basis for modeling the cost of extending similar funding to independent school students discussed below.

Special Education Funding for Ontario Independent Schools

This section provides estimates as to what it would cost for the Ontario government to provide a level of per-special needs pupil special education funding to students in independent schools. Two different broad ranges of estimates are provided in order to capture a series of possible cost scenarios. The estimates below are based on 2016/17 Ontario independent school enrollment data from Statistics Canada, the latest year available. 25 25 Statistics Canada (2019). Table 37-10-0109-01—Number of students in elementary and secondary schools, by school type and program type. At: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710010901 The groups of estimates are based on a 50 and 75 percent level of funding compared to the funding available to public school students in need. 26 26 This is a lower level of funding parity than that provided by other provinces. For example, in British Columbia (BC) public schools, students with severe special needs receive $38,800 in special education funding, while students with moderate and mild special needs receive $19,400 and $9,800 respectively. This special education funding is matched 100% in BC for both Group 1 and Group 2 independent schools. Group 1 independent schools employ BC-certified teachers and meet program and administrative requirements set by the BC curriculum. Group 2 independent schools have the same requirements, however have higher per-pupil operating costs compared to local public schools (British Columbia, 2018). While in Alberta, students with designated mild to moderate special needs enrolled in independent schools receive no additional funding above baseline per pupil funding for students in independent schools which is 60 percent or 70 percent of the per public pupil funding allocation, unless they are attending a Designated Special Education Private School (DSEPS). However, students with designated severe disabilities are eligible to receive additional funding dependent on the level of support needed on a case-by-case basis (Alberta, 2018). The funding level of 75 percent has also previously been proposed by Hepburn and Mrozek in their 2004 paper which can be found here: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/LettheFundingFollowChildren.pdf and thus we use it for our first set of calculations.

Within each level of funding, estimates are provided for different possible percentages of students meeting the criteria for funding as set out in the public sector. The range of potential student (with special needs) shares in the independent school sector used are from 10 to 25 percent (this is compared to 20 percent of students in the public-school sector in Ontario). 27 27 In Alberta, which does provide some funding for independent school special needs students, approximately 7.5 percent of independent school students are designated as having special needs, meaning that the upper-end of our range is likely a high cost scenario for the Ontario government (Alberta, 2019). It is important to note that these estimates are also likely high due to the fact that there will be some savings from students shifting from the public school sector where they are receiving full funding to the independent school sector where they will be funded at a lower rate. 28 28 These savings were not included in our estimates given that we cannot say how many students with special needs could transfer to the independent school sector after the funding change.

Table 3 displays the outcomes of the 75 percent funding scenario. In the enrollment levels utilized below, the additional expenditures from the Ontario government to provide similar special needs funding to independent school students ranges from approximately $78 to $195 million.

If instead a 50 percent per-public school special needs funding for independent school students is utilized, the additional expenditures for the Ontario government range from $52 to $130 million (see Table 4).

Conclusion and Discussion

Services for a child’s disability should be based on need and not on the school the child attends. This is an issue of fundamental justice in a progressive democracy aligning with recent statements about the inherent dignity of all by the Ontario Human Rights Commission and by the United Nations convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Implementing the necessary changes would offer protection and respect for the most vulnerable in our society and will lead to enhancing family resilience for those who care for our society’s most vulnerable. Furthermore, the proposal here contributes to financial value and efficiency in government spending.

As stated in the Special Education in Ontario Policy and Resource Guide 29 29 http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/document/policy/os/onschools_2017e.pdf , we believe all students can succeed: each student has a unique pattern for learning and fairness is not sameness. Providing equitable access to equipment and services to children with special needs in all schools, government and non-government (public and independent) will enable all of Ontario’s exceptional children to learn, thrive and succeed.

Correcting the long-standing inequity—of school-based rather than need-based funding for students with special needs—will enable this government to unfold its commitments, values and priorities for protecting the most vulnerable in society and providing value, efficiency and effectiveness for all government spending.

The change proposed in this brief will be a modest cost for the government, ranging as this paper demonstrates, from $78 to $195 million if the government provides 75 percent of the funding available to public school students to those students with special needs in independent schools; and $52 to $130 million if only 50 percent funding is provided.

Equitably sharing responsibility for Ontario’s exceptional children in both public and independent schools will empower Ontario’s future, supporting diversity and fairness. This correction is long overdue.

References

Alberta, Ministry of Education. (2018). Funding Manual for School Authorities 2018/19 School Year. At: https://education.alberta.ca/media/3795601/2018-19-funding-manual-fall-update.pdf

Alberta, Ministry of Education. (2019). Student Population Overview: Alberta’s Student Population. At: https://education.alberta.ca/alberta-education/student-population/everyone/student-population-overview/

Allison, D.J., Hasan, S., & Van Pelt, D.A. (June 2016). A Diverse Landscape: Independent Schools in Canada. Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute. At: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/a-diverse-landscape-independent-schools-in-canada

Auditor General of Ontario (2010). Chapter 4, Section 4.14: Special Education. At: http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en10/414en10.pdf

British Columbia, Government of. (2018). Funding Rates for Independent Schools 2018/19. At: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/administration/kindergarten-to-grade-12/independent-schools/funding_rates_1819_preliminary.pdf

Green, B., Sikkema, D. & Sikkink, D. (2018). Cardus Education Survey 2018: Ontario Bulletin. At: https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/cardus-educationsurvey-2018-ontario-bulletin/

Hepburn, C. & Mrozek, A. (2004). Let the Funding Follow the Children: A Solution for Special Education in Ontario. Vancouver, Fraser Institute. At: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/LettheFundingFollowChildren.pdf

Macleod, A. & Emes, J. (2019). Education Spending in Public Schools in Canada, 2019 Edition. Vancouver, Fraser Institute. At: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/education-spending-in-canada-2019_0.pdf

Ontario Human Rights Commission. (March 2018). Policy: Accessible Education for Students with Disabilities. Government of Ontario. At: http://www.ohrc.on.ca/sites/default/files/Policy%20on%20accessible%20education%20for%20students%20with%20disabilities_FINAL_EN.pdf.

Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2014). Support Every Child, Reach Every Student: An Overview of Special Education. At: http://www.ldao.ca/wp-content/uploads/Special-Education-Overview-Oct-2014.pdf

Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2017). Special Education in Ontario: Policy and Resource Guide. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/document/policy/os/onschools_2017e.pdf

Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2018a). Quick Facts, Ontario Schools, 2015-16. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/quickfacts/2015_2016.html

Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2018b). Private Schools Contact Information 2018. At: https://www.ontario.ca/data/private-school-contact-information

Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2018c). 2018-19 Education Funding: A Guide to the Grants for Student Needs. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/funding/1819/GSNGuide2018-19Revised.pdf

Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2018d). Grants for Student Needs Projections for the 2018-19 School Year. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/funding/1819/GSNProjections2018-19.pdf

Ontario, Ministry of Education. (2019). An Introduction to Special Education in Ontario. At: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/general/elemsec/speced/ontario.html

Ontario, Ministry of Finance. (2018b). Taking Action to Put Ontario’s Fiscal House in Order. At: https://www.fin.gov.on.ca/fallstatement/2018/fes18-fiscal-accountability-en.pdf

Ontario, Ministry of Finance. (2018a). A Plan for the People—2018 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, Background Papers. At: https://www.fin.gov.on.ca/fallstatement/2018/fes2018-en.pdf

People for Education (2018). 2018 Annual report on schools: The new basics for public education. At: https://peopleforeducation.ca/report/2018-annual-report-on-schools-the-new-basics-for-public-education/

Statistics Canada (2019). Table 37-10-0109-01—Number of students in elementary and secondary schools, by school type and program type. At: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3710010901

United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. At: http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf

Van Pelt, D.A., Allison, D.J. and Allison, P.A. (May 2007). Ontario’s Private Schools: Who Chooses Them and Why? Vancouver: Fraser Institute. At: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/OntariosPrivateSchools.pdf

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express sincere appreciation to Sara Pot for her personal insight as a mom of two medically fragile children with complex needs. Her family’s experience with non-government schools and publicly funded children’s rehabilitation services offered us a unique perspective to the vision of seeing all of Ontario’s children thrive.