EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS provide a variety of learning opportunities enhanced through membership in school associations. These associations strengthen the voice of the independent school sector, increase capacity, and promote values and standards among the diverse forms of quality non-government K–12 education.

This paper is a first effort to understand the place of associations in the Canadian independent school landscape. We map the functions of fifty-six provincial, national, and international education associations in which independent schools in Canada participate. The analysis explores four key functions of education associations: professional development, public relations, administrative operations, and student services. We are particularly interested in the relationship between religiously oriented associations and the services these groups provide. Finally, we compare the activities of associations in provinces that offer some level of funding for independent schools with associations in non-funded provinces.

Professional development is a near universal feature of the associations in this study, including development opportunities for trustees, administration, and front-line educators. Most associations are involved in public relations, with nearly two-thirds of associations engaging in government relations on behalf of member schools. A significant portion of associations are involved in administrative operations, with nearly two-thirds involved in administrative policy development and one-third offering quality assurance services. Associations place the least emphasis on student services, with only a third facilitating events and less than a fifth assisting in student assessment.

Approximately three-quarters of associations in our study hold to a faith or pedagogical orientation, with nearly half being religiously oriented. We find that religiously oriented associations are more frequently involved in sector advocacy, administrative policy development, student events, student assessment, and professional assessments. While most associations provide some form of professional development, non-religiously oriented associations are more likely to be involved in governance development, administrator development, school marketing, and government relations.

About three-quarters of associations are headquartered in the five provinces that offer some level of direct funding to qualifying independent schools. This raises questions about the nature of the relationship between funding and the presence of associations.

Associations in funded provinces are more likely to collaborate in marketing schools, provide curriculum support, and engage in government relations. We find that associations in non-funded provinces are more likely to engage in self-regulatory activities and quality measures such as teacher certification, quality assurance, and governance development.

Independent schools do not operate in isolation, but rely on associations to enhance the delivery of quality education. This study is a first attempt to understand how associations function in the independent schools landscape.

INTRODUCTION

THE INDEPENDENT SCHOOL sector in Canada is a diverse and vibrant landscape. Canada is home to approximately fifteen thousand public government schools, but it is also home to about two thousand independent, non-government schools. Independent schools provide a variety of educational options for parents and students and communities, often emphasizing particular pedagogical approaches or faith-based orientations. While independent schools are subject to government regulation and, in some provinces, eligible for partial government funding, they are owned and operated independent of government bodies and government schools. Typically registered as non-profits, most operate under the authority of an independent board of governors or trustees. Nevertheless, although diverse and independent, these schools participate in a vibrant and interconnected web of associations.

This paper maps the functions of the associations in which independent schools in Canada participate. It offers a first attempt to understand how these associations function within the independent school landscape in Canada and gives particular attention to the services they provide in the delivery of education by independent schools.

DATA SOURCES AND APPROACH

TO THE BEST of our knowledge, an overview of the Canadian independent school association landscape has never been prepared. 1 1 A web and academic database search was conducted between January 22 and January 26, 2018. A diverse group of organizations represent the interests of independent schools and provide services to schools that are members (or affiliated in some manner). 2 2 For ease of writing we will use the term “members” in this paper when referring to the schools that the associations represent and serve through membership, association, or some other affiliating means. For the purpose of this study, an independent school association is defined as an organization that includes member or associated schools, educators, and/or administrators operating in the independent school sector in Canada and provides services or benefits to those members or associates.

To be included in this present analysis, associations must have had a publicly accessible web presence excluding social media accounts. Associations were identified and data collected through web searches conducted between February 12 and April 9, 2018. International associations were included when identified by Canadian association websites and when international association websites identified Canadian schools, educators, or administrators as members. The web search identified sixty-five potential associations for inclusion in the study.

A second criterion was applied to the sixty-five associations. For inclusion in the analysis, there must have been publicly available evidence that the association provided services or benefits to members in at least two of four categories: professional development, public relations, administrative operations, or student services. Data were collected from publicly accessible portions of association websites, member websites, and government charity listings, where available. After applying these criteria, fifty-six associations remained for analysis.

After associations were analyzed and classified for the above characteristics, the noted characteristics were then analyzed for frequencies. Cross-tabulations were then conducted to investigate for association differences across two key features: first, between associations serving provinces where government funding is available for independent schools and associations in those provinces where no funding is provided, and second, between differences in activities of those associations established to serve religiously oriented schools and those established to serve schools without a stated religious orientation.

LIMITATIONS

OUR ANALYSIS is limited by several factors, and we list the ones of which we are aware. The identification of associations is limited to those with a publicly accessible online presence. Data collection is limited to publicly available data, and it is possible that detailed information may be present on member-only portions of associations’ websites and thus was not included in our analysis. Furthermore, publicly available data is self-reported, often estimated by associations, and also at risk of being out of date. In addition, it is possible some associations corresponding to our criteria remain unidentified and thus have not been included in this analysis.

ASSOCIATION PROFILES

THE FIFTY-SIX associations identified in this study are diverse in size, purpose, and function. While associations often provide a variety of services to members, they emphasize specific functions on their website. The associations included in this report display a diverse range of structures and perform varied services. Some associations function much like a district school board, while others are democratic, member-driven networks. As a result, independent schools often hold membership in multiple associations. It is important to note that associations often identify other associations as partner organizations, and in some cases the associations are regional derivatives of other associations.

Our definition of an association states that the organization must have independent school as members or associates. While many of the associations exist solely to serve independent schools, we did note, as mentioned above, that several of the associations serve both public and independent schools.

The associations are diverse in size, membership, and influence, ranging from representing 1 independent school to as many as 298 schools. Associations have a wide range of staffing scenarios and budgets, reflecting the reality that there is no typical association type. Several of the variations are noted below.

MISSION AND PURPOSE. Associations representing independent schools typically have mission statements that emphasize strengthening the voice of the independent school sector, and promoting values relating to faith, pedagogy, or other standards for quality education.

Although our present analysis focused mainly on four identified functions of the associations—professional development, public relations, administrative operations, and student services—and did not include a systematic analysis of the mission and purpose statements of the associations, a cursory review of these statements reveals a fair amount of diversity.

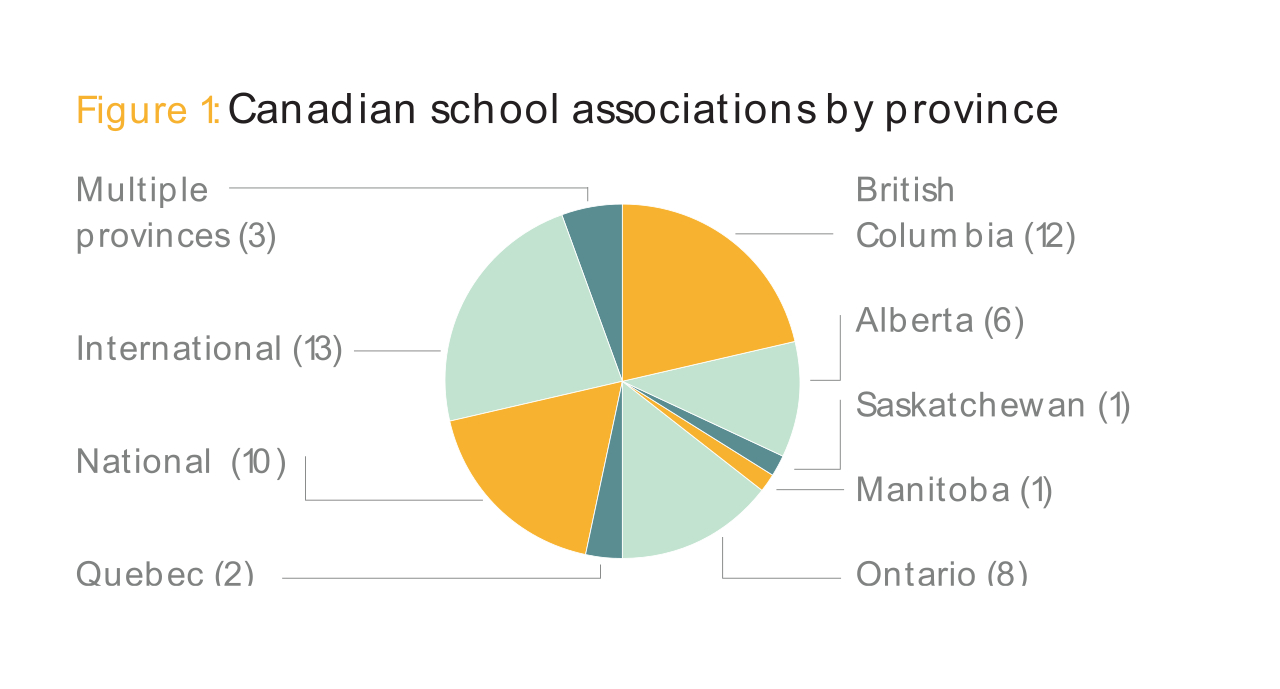

GEOGRAPHICAL SCOPE. As education is under provincial jurisdiction in Canada, and given that Canada is a country with a significant landmass, it is unsurprising that thirty-three of the fifty-six associations focus on provincial and regional membership. Based on association mailing addresses, as shown in figure 1, British Columbia has the largest portion of associations, with twelve. Ontario and Alberta, with eight and six associations respectively, have the next largest portion of associations, with headquarters in those provinces. Although some associations serve independent schools in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador, no associations meeting our criteria are headquartered in the Atlantic provinces (Figure 1).

It is worth noting that this analysis reveals that provinces with the largest proportions of the Canadian population have more associations. Quebec, however, is an outlier, with only two headquartered associations meeting our criteria, despite having the second largest population and a public policy environment favorable (through funding) to independent schools.

Nearly 60 percent of associations are provincial or regionally focused, but note that a strong minority of over 40 percent of associations are national (17.9 percent) or international (23.2 percent) in scope and presence. 3 3 A number of associations have independent school members in multiple provinces. Provincially focused associations occasionally accept out-of-province members. For the purpose of our analysis, we classified three associations that intentionally represent members in more than one province as multi-regional.

The interprovincial and international orientation of such a significant share of the associations serving independent schools is worth further investigation. When two of every five associations serve a national or global membership, this could well be an indicator of the coherence and collaboration across provincial and national boundaries in the independent school sector. It could also suggest that the ideas, innovations, and issues addressed have similarity across provinces. On the other hand, it could simply be a function of the smaller size of the independent school sector in each province and larger-scale collaboration necessitates cross-province initiative. In any event, this finding is worth more study.

FAITH AND PEDAGOGICAL ORIENTATION.

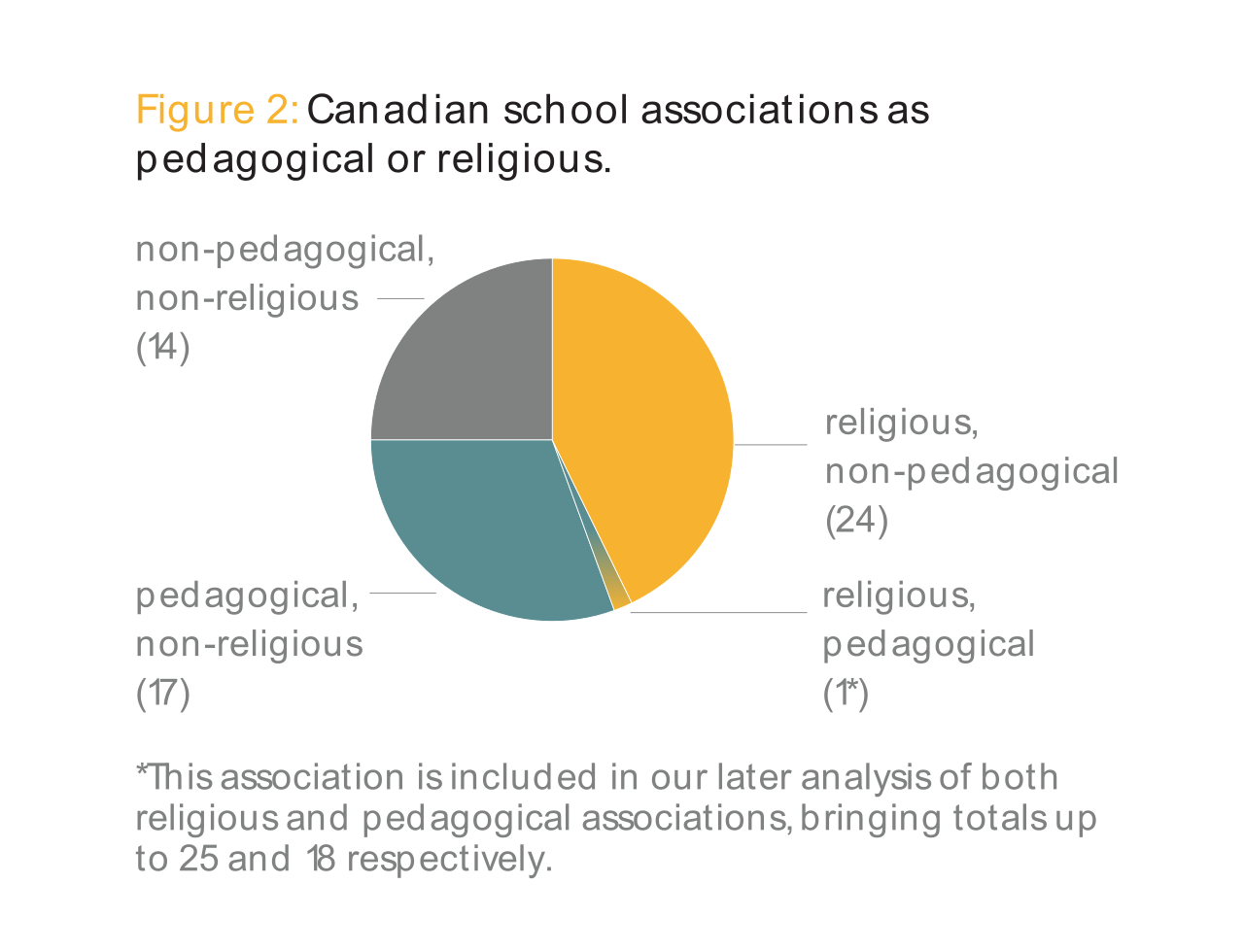

A majority of the fifty-six associations are organized around either a specific pedagogy or faith orientation. These elements are an important aspect of an association’s identity.

We determined that an association is pedagogical or faith-oriented based on the mission statement of the association. Using this measure, we found that 75 percent of associations have either a religious or a pedagogical orientation or both (as was the case in one instance). Stated another way, as shown in figure 2, 25 percent are not defined by a distinct religious or pedagogical orientation. Nearly half (44.6 percent) of all associations (twenty-five in total) have a faith orientation, and 32.1 percent (eighteen in total) are pedagogically oriented (one association is counted in both categories) (Figure 2).

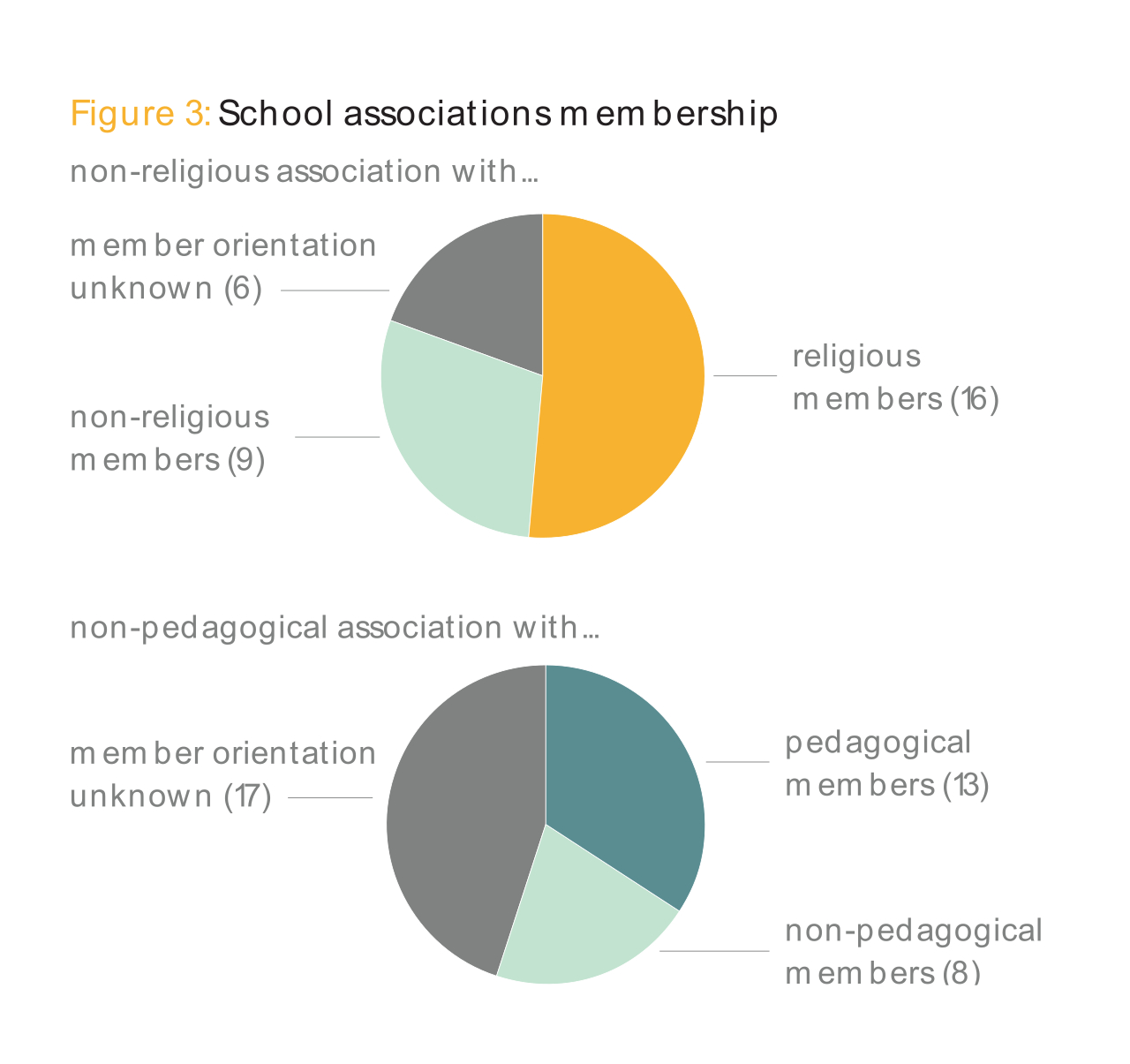

These orientations are a significant factor in the formation of about three of every four independent school associations in Canada. As important as these distinguishing features are, independent schools are not necessarily sequestered into faith or pedagogical associations. As noted above, many independent schools hold membership in multiple associations. We investigated for religiously oriented school membership in non-religiously oriented associations and for pedagogically oriented school membership in non-pedagogically defined associations.

More than half (55.4 percent) of identified associations do not have a religious orientation. Even so, of those associations, just over half (51.6 percent) were determined to have religiously oriented members. This finding may even under-represent the reality as the presence of religiously oriented members could not be determined in approximately 19.4 percent of non-religious associations, and thus more may well be present.

Associations without a specified pedagogical orientation account for 67.9 percent of identified associations (thirty-eight of fifty-six associations), with 34.2 percent of those associations having pedagogically oriented independent school membership. As above, and as shown in figure 3, the presence of pedagogically oriented independent schools is undetermined in 44.7 percent of non-pedagogically oriented associations (Figure 3).

The pattern for diversity of membership held at the national level as well. Ten organizations met our criteria for a national association. Half were not religiously oriented and among these, three associations have religiously oriented members. Five of the national associations were not pedagogically oriented, with one of these associations having pedagogically oriented membership.

Similar findings were noted at the international association level. We identified thirteen international organizations of which ten do not have a faith orientation. Among the ten, two had faith-oriented member schools. We identified seven international organizations that are not pedagogically oriented. Among those associations, three have pedagogically oriented members.

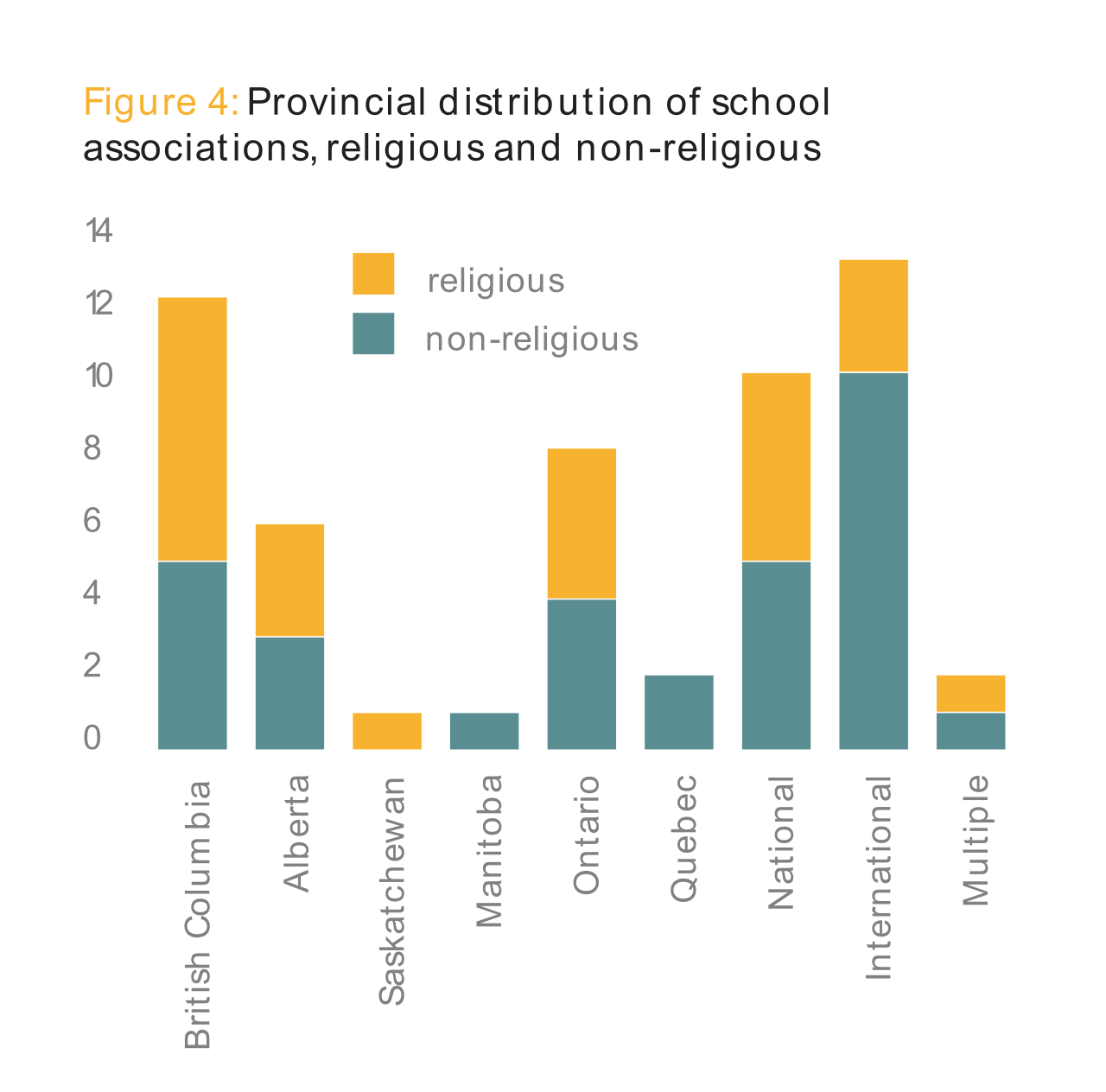

The provincial distribution of religiously oriented associations, as shown in figure 4, is also worthy of note. The percentage of faith-oriented provincial associations is similar for three of the four largest provinces. Faith-oriented associations account for approximately 58.3 percent of associations in British Columbia and 50 percent in Alberta and Ontario. Quebec has no religiously oriented associations meeting our criteria. Of the associations serving at the national level, again half are religiously oriented (Figure 4).

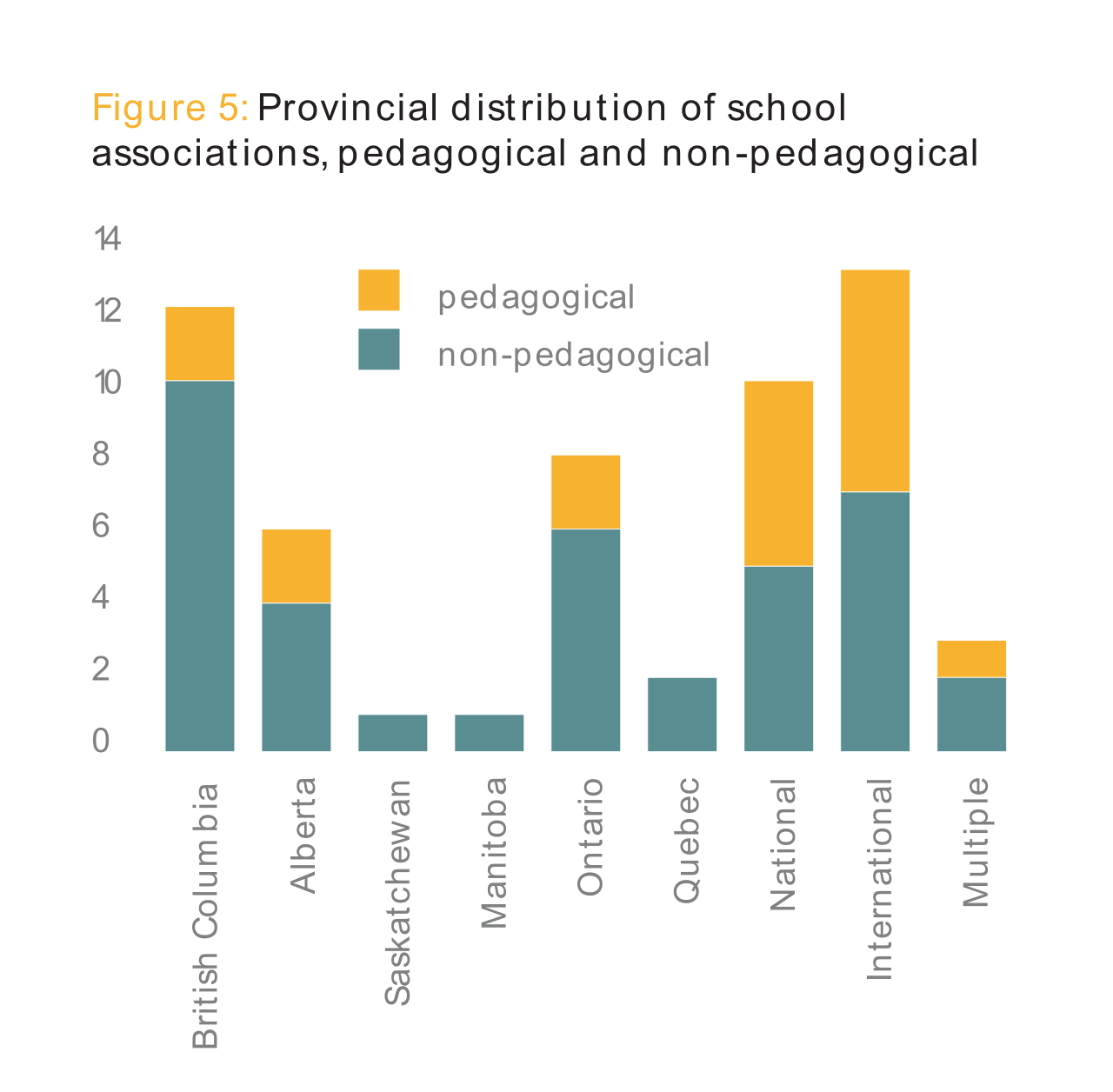

In terms of pedagogically oriented associations, in the larger provinces, fewer than half are defined as such. in British Columbia, 16.7 percent of the associations are pedagogically oriented associations, while 33.3 percent of associations in Alberta are. In Ontario, as shown in figure 5, 25 percent of associations are pedagogically oriented, and, as above, none of the associations in Quebec are. Half of national level associations are also pedagogically defined (Figure 5).

In all, several key findings emerge. First, independent school associations, despite their religious or pedagogical definitions, serve member schools that do not necessarily define themselves in the same way. And second, while Quebec’s associations are neither religiously nor pedagogically defined, in the remaining three largest provinces, British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario, more than half of the associations have a religious orientation and up to a third have a pedagogical orientation.

ASSOCIATION ACTIVITIES AND SERVICES

ASSOCIATIONS SERVING independent schools have distinct identities but often engage in similar activities. We identified four broad categories under which these activities can be organized: professional development, public relations, administrative operations, and student services. We developed subcategories, explained below, to delineate further the activities and services within each of those four main areas.

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT.

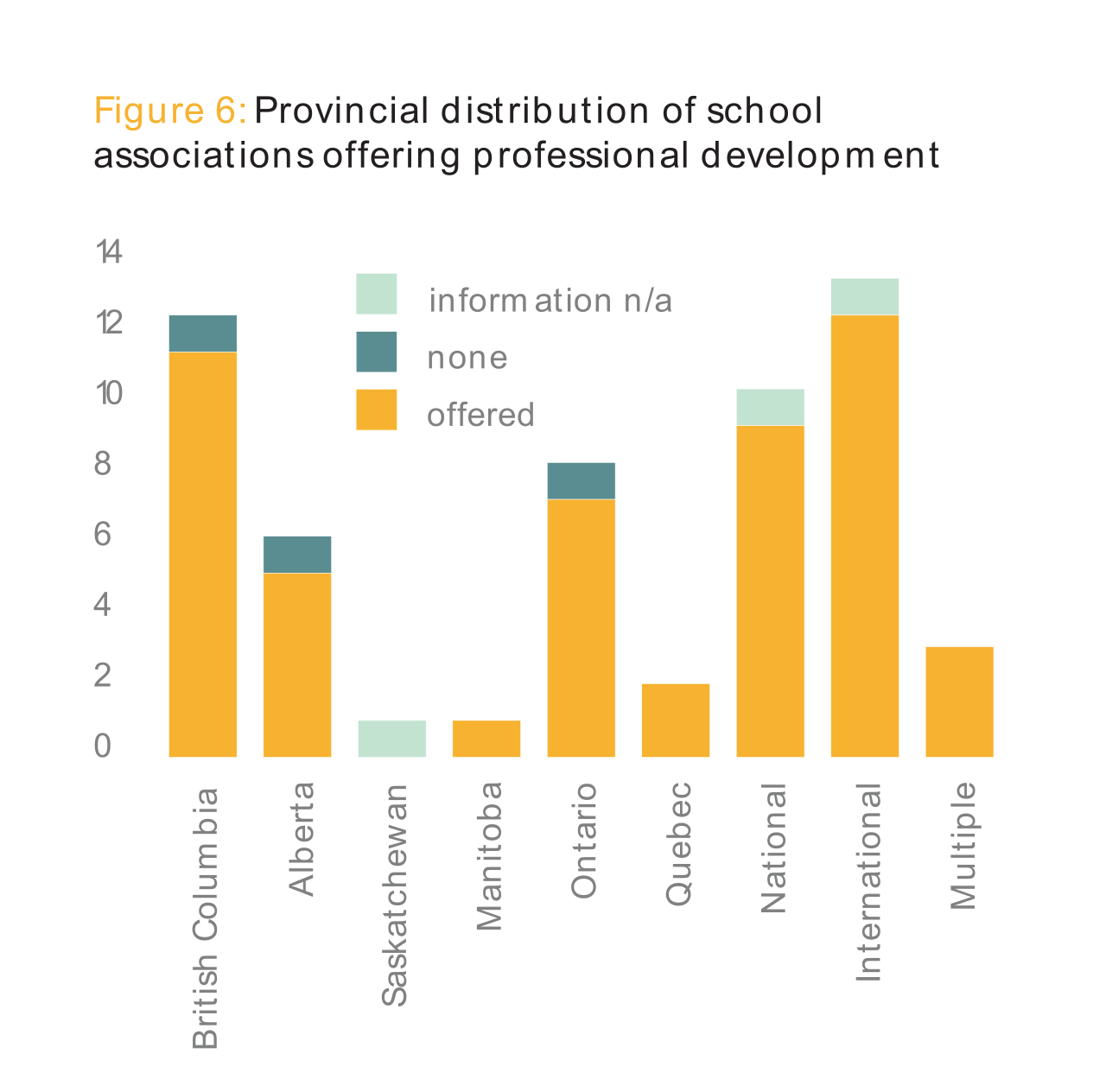

Professional development is a near universal feature of the associations in our study. Fully 89.3 percent of associations, as shown in figure 6, provide some aspect of professional development (Figure 6). 4 4 For seven percent of associations, professional development activities could not be determined from publicly available web sources.

We developed five subcategories to understand the nature of the professional development. Three sub-categories are identified by the recipients: governance development, principal / administrator development, and educator development; the final two sub-categories note aspects of curriculum resources and professional assessment. 5 5 In this section, findings are reported for all 56 associations. If we were unable to determine the presence of a type of professional development we did not exclude that the association. Thus it is possible that our findings noting the presence of specific professional development activities will under-represent the extent or presence of professional development activities offered.

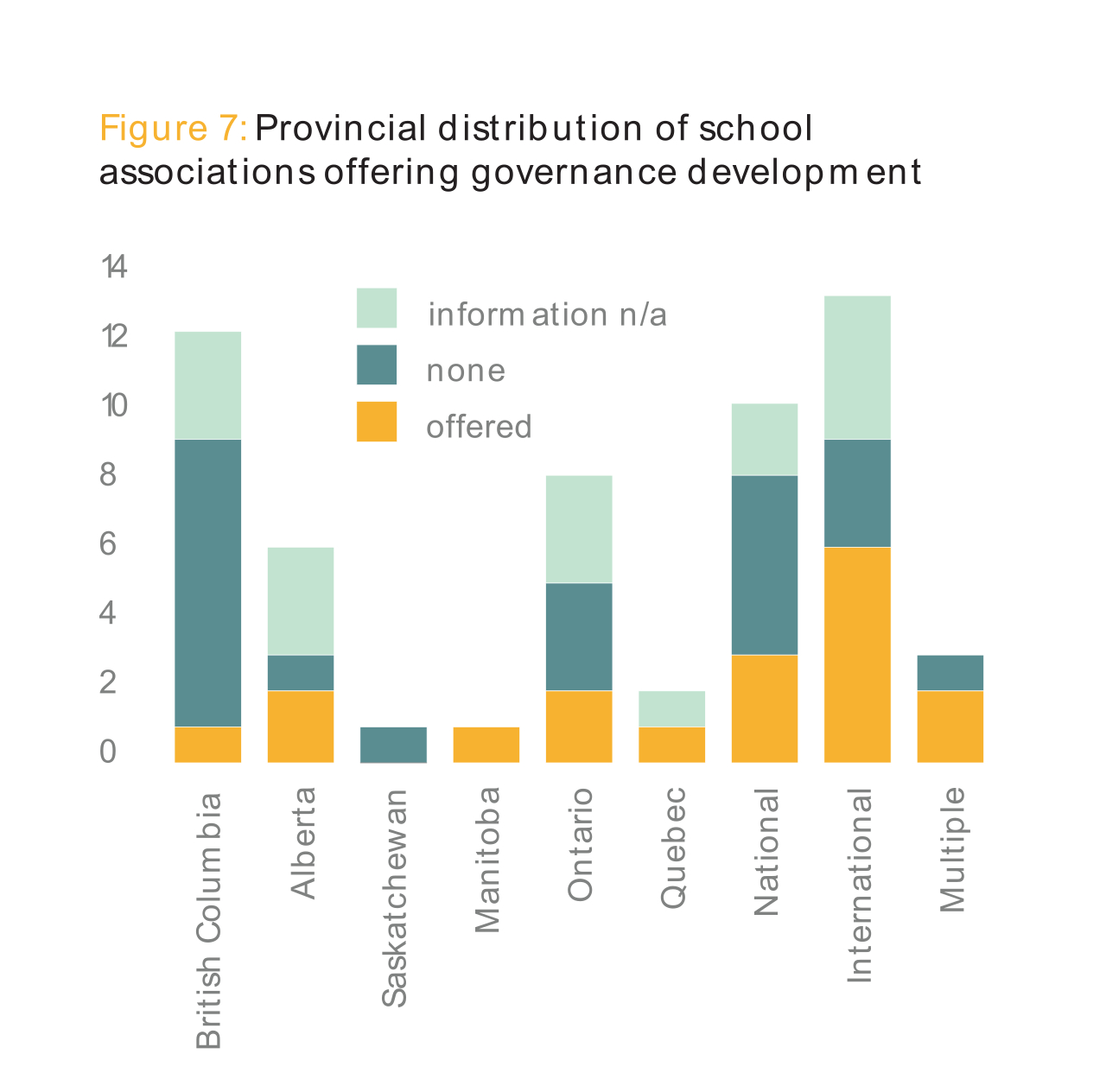

Governance development

The study measures the share of associations providing materials, presentations or consultations for the purpose of professional development for trustees or board members. Almost a third of the associations, as shown in figure 7, were found to provide services for governing boards and trustees. We caution readers that for about 30 percent of associations the presence of governance development was undetermined. While it appears that a majority of associations do not offer governance development, about a third certainly do, and in addition, a small number of associations specifically focus on boards and trustees as a critical aspect of their work (Figure 7).

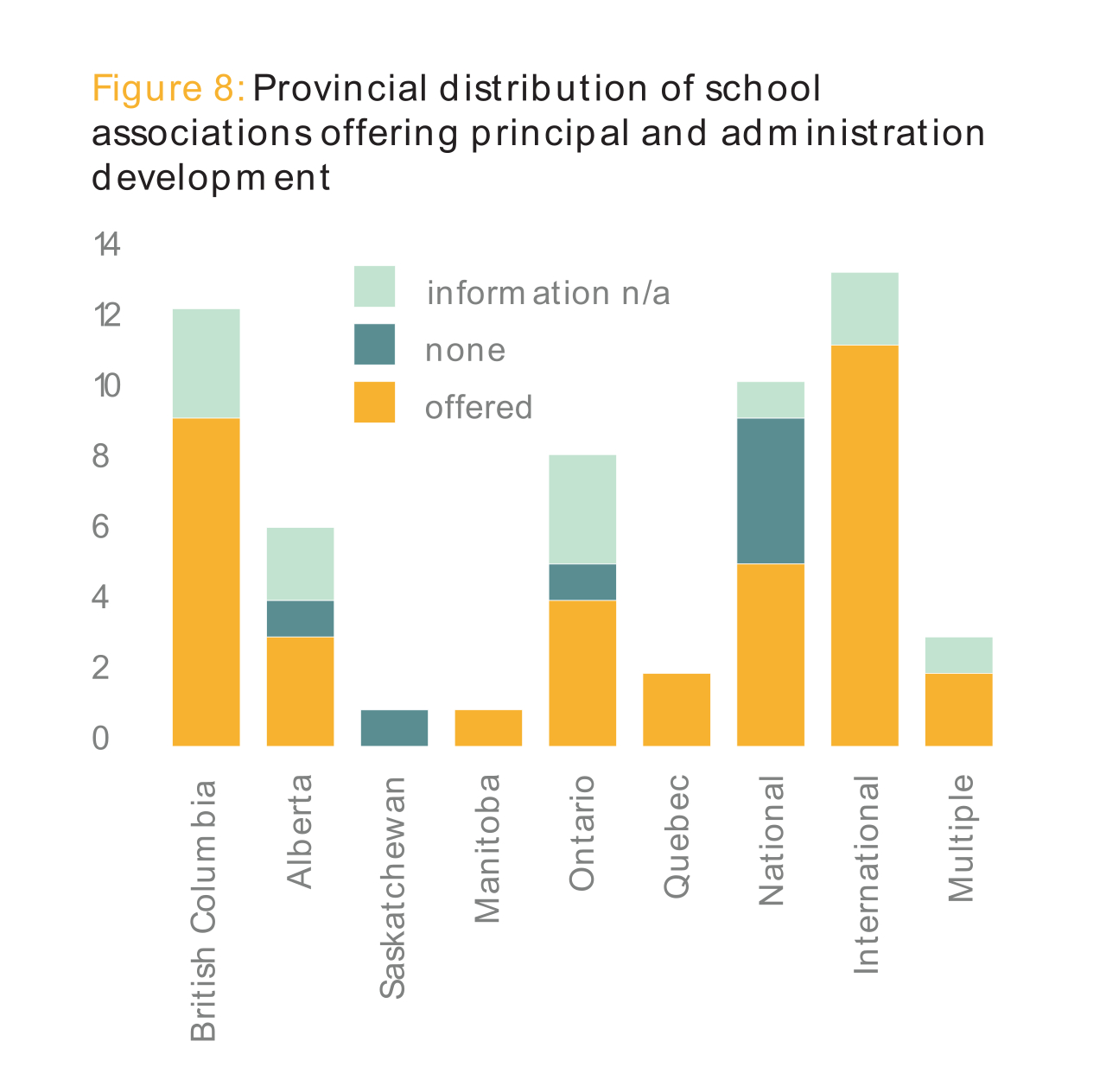

Principal and administration development

About two-thirds (66.1 percent) of associations provide materials, presentations, or consultation for the purpose of professional development for principals and administration. For 21.4 percent of associations, such activities could not be determined. Regional variations among provinces with more than two associations shows that between 50 and 75 percent of associations offer this type of professional development. In British Columbia, nine of 12 associations provide professional development for administrators. See figure 8. International associations overwhelmingly focus on independent school administration with 84.6 percent providing this service (Figure 8).

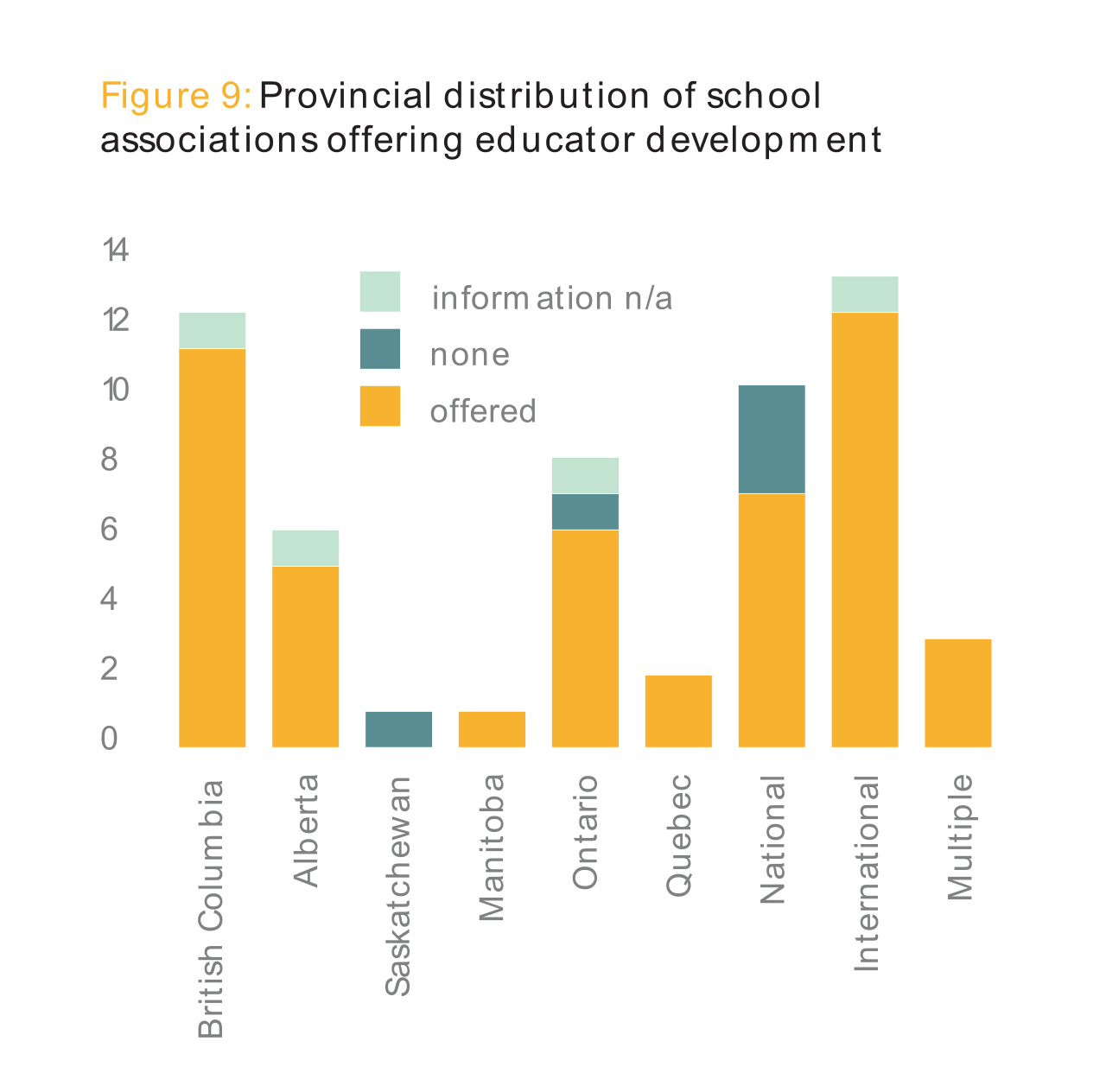

Educator development

Teachers and educators are the largest intended beneficiary of professional development offered by associations. Fully 83.9 percent of associations provide materials, presentations or consultations for the purpose of professional development for teachers and educators, as shown in figure 9, in order to enhance student learning. Regional organizations are well positioned to facilitate workshops where national organizations tend to incorporate professional development into national conferences. Even so the majority of national and international associations all provide educator development (Figure 9).

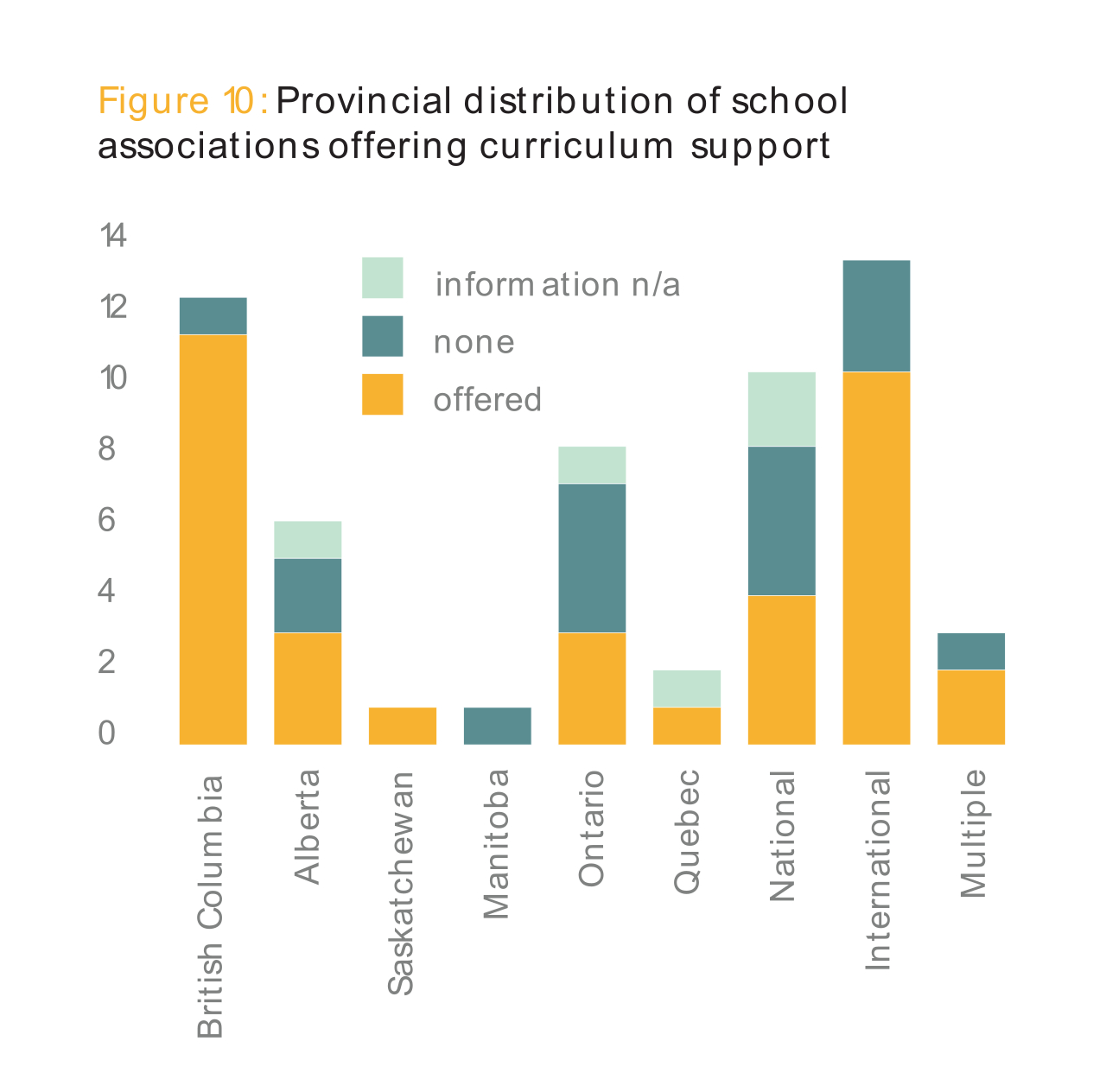

Curriculum resources

Further to learning development, 35 of 56 associations (62.5 percent) provide resources that enhance curriculum including materials, whether online or print, workshops and presentations. Nearly all British Columbia associations and half of the Alberta associations provide curriculum resources. Only in Ontario did a minority of associations (37.5 percent) offer curriculum resources. See figure 10. International associations overwhelmingly provide curriculum resources with 10 of 13 associations doing so, while national associations were less likely with 40 percent offering resources. It may be worth further attention to understand why associations in British Columbia and those internationally situated were more frequently found to offer curriculum support. And, perhaps of even more intrigue, why were almost two of every three Ontario associations not involved in curriculum support? Does this in any way reflect a deeper independence of independent schools in Ontario compared to a more highly regulated province like British Columbia with more specific curriculum requirements and expectations? (Figure 10)

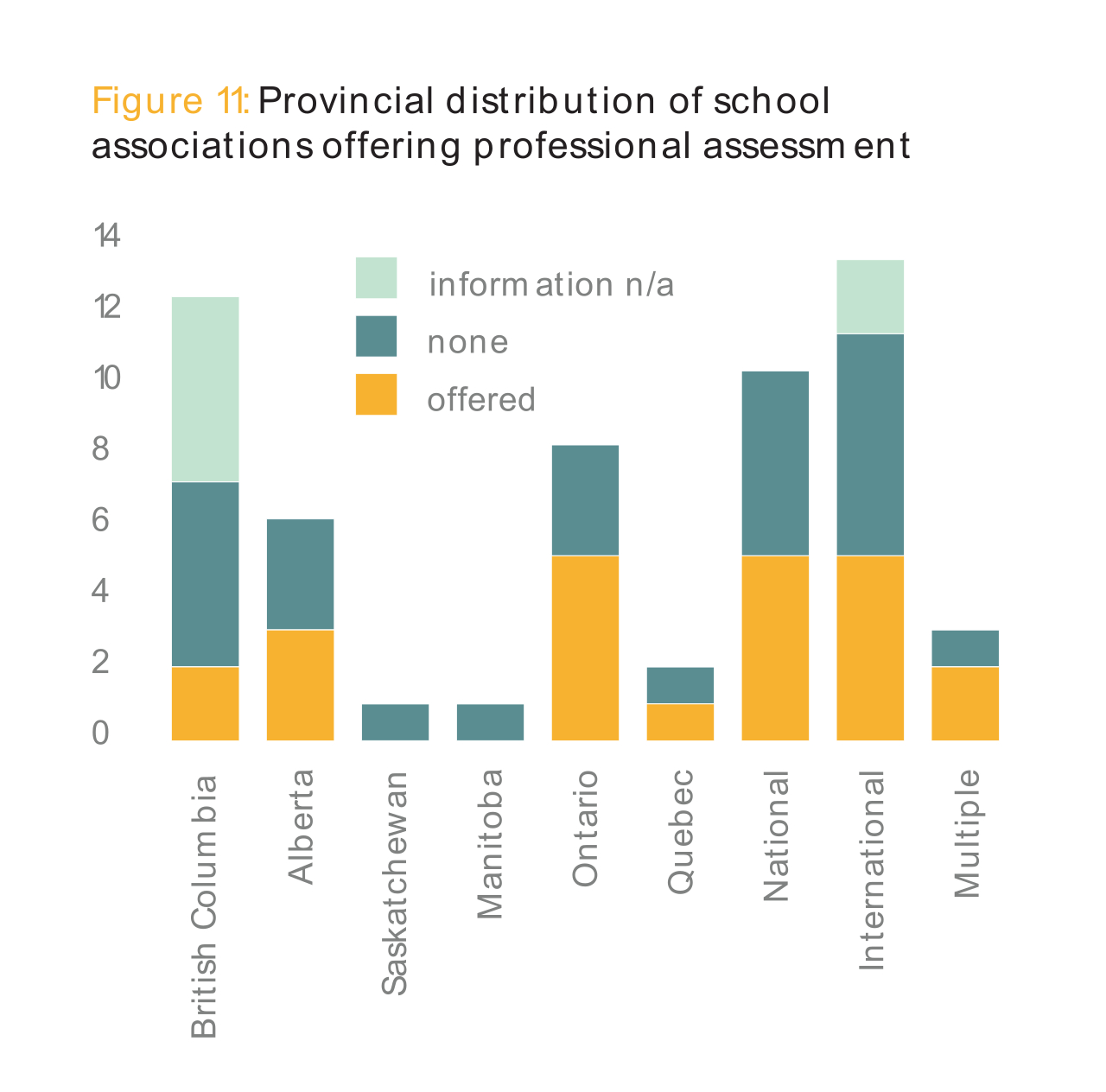

Professional assessment

Associations that provide assessment materials, conduct staff assessments, or provide certification for trustees, principals, administrators, teachers or educators are noted. Assessment services are wide ranging and can include inschool evaluations of educators and professionals. Other services under this sub-category include coursework or workshop participation resulting in certification within the association. 6 6 Many of the 56 associations require members to meet and maintain minimum standards to join and remain in the association. The professional assessment measure in this study observes services provided by associations beyond minimum standards required for membership.

While teacher accreditation is a provincial matter, some associations provide accreditation in pedagogical methods to ensure consistent standards of teaching methods and performance.

Fewer than half (41.1 percent) of associations, as shown in figure 11, provide professional assessment or certification. British Columbia shows 16.7 percent and Alberta and Quebec show 50 percent of associations while in Ontario 62.5 percent of associations provide professional assessment. Half of the national associations provide the service while 39 percent of the international associations provide assessment or accreditation (Figure 11).

Thus, the professional development activities and services most likely to be offered by independent school associations are services to the educators (almost 84 percent of associations). The focus on teacher development whether by a provincial association or one with a larger reach, is an emphasis for independent school associations. Even so, the majority of associations (more than 66 percent) also provide development activities for principals and school administrators. Board and governance development was offered by just under a third of all associations. Association focus on educators and on leaders indicates demand for such support and may be worthy of further study. Curriculum support was most prevalent in British Columbia with over 90 percent of associations involved in this, and overall, curriculum support was noted in three fifths of all associations. Assessments for quality or certification are most prevalent in Ontario associations, and overall were noted in over two fifths of all associations. In all, professional development of a variety of types is key to the function and services of the vast majority of independent school associations.

PUBLIC RELATIONS.

The second most common function of independent school associations is public relations. The three subcategories under public relations are advocating for faith or pedagogical oriented education, marketing member schools, and government relations.

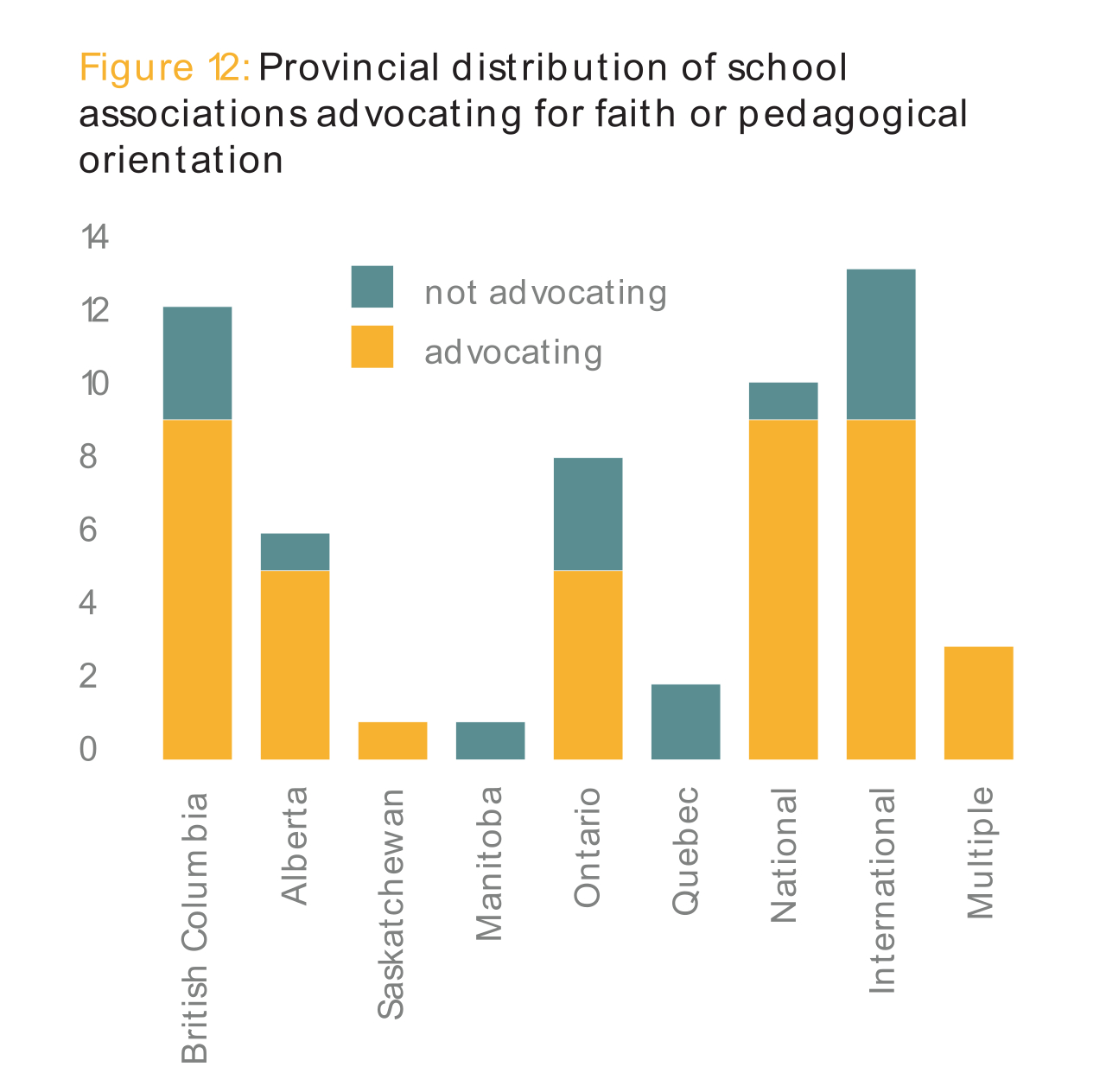

Pedagogical and faith orientation advocacy

Fully 73.2 percent of associations advocate or promote the benefits of faith-oriented or pedagogically distinct education, as shown in figure 12. It is unsurprising that associations which indicate such orientations in their mission statements promote these forms of education.

Notable observations include the absence of religiously or pedagogically oriented associations meeting the criteria in Quebec. In contrast, nine of ten national organizations advocate for religiously or pedagogically oriented education (Figure 12).

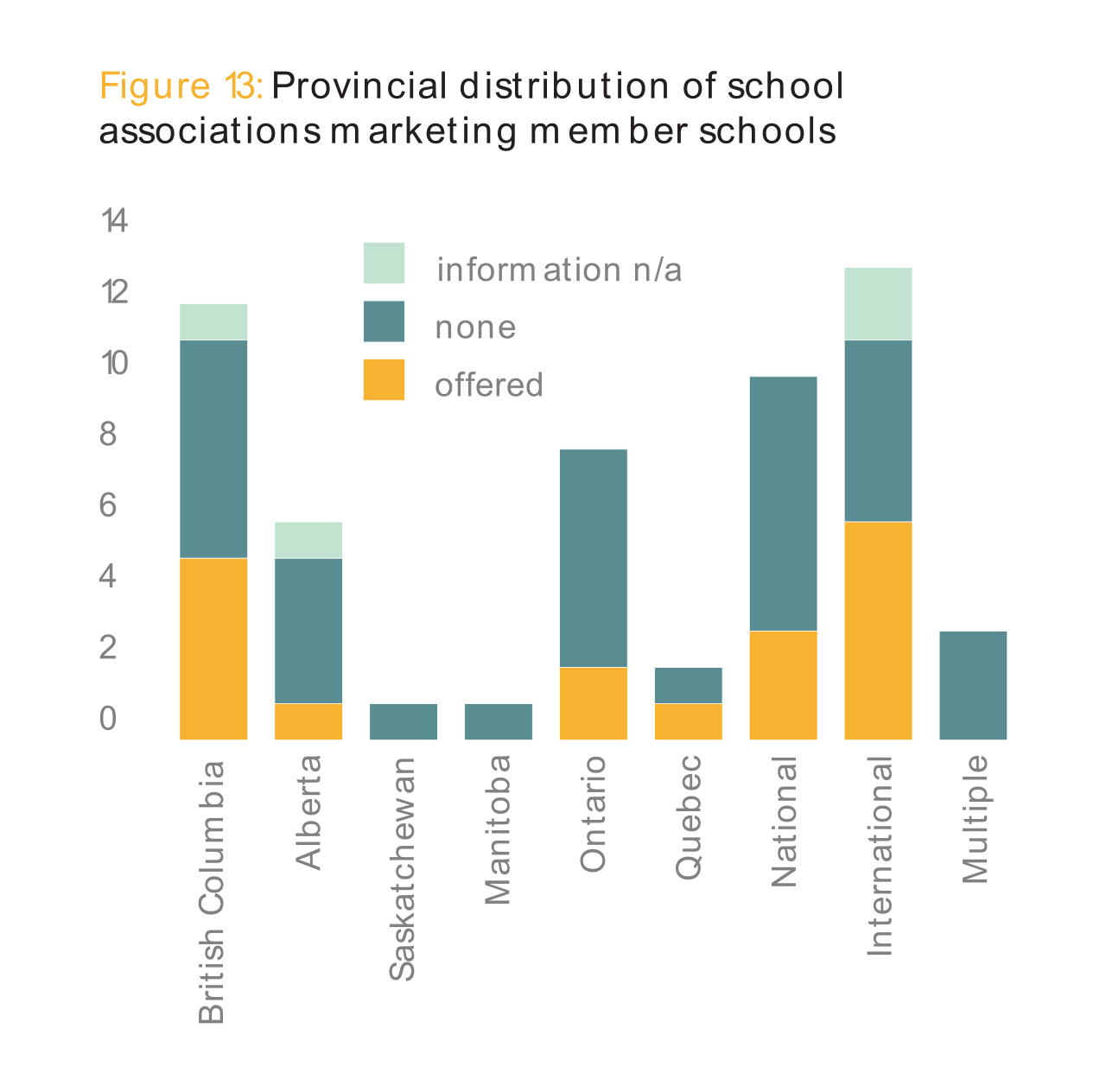

This subcategory includes associations that promote or advertise member schools, facilitate promotional events, or provide materials to aid member schools’ self-promotion. In our analysis, to measure active promotion, the subcategory includes more than simply listing member schools on the association website or permitting the association logo in member-school promotional materials, because both of these are common practice. To be included in this analysis more was required, such as featuring stories of schools.

Just under a third of associations (32.1 percent) demonstrate publicly available evidence of promotional activities meeting the criteria for this measure. See figure 13. It’s possible, of course, that promotional activities and events are not recorded on association websites, and websites do not include the full extent to which member schools are marketed by the associations. While independent schools likely benefit from website listings and the advertising of their association membership, promotion is likely targeted to the local community, and thus promotional results may best be achieved by schools themselves. The exceptions are schools who seek international students. Nearly half of the international associations (46.2 percent) market member schools beyond school listings on their website (Figure 13).

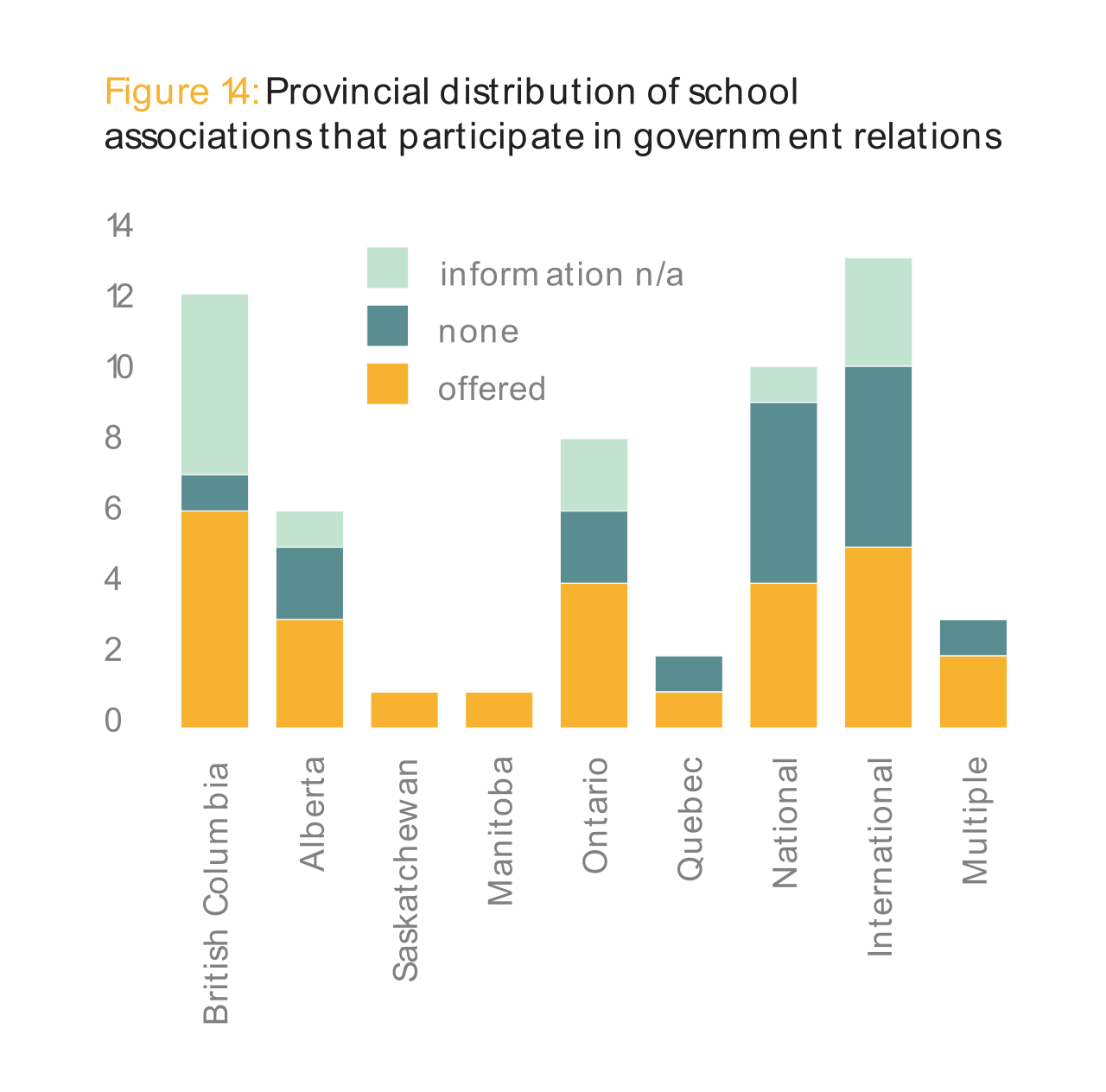

Almost half (48.2 percent) of associations, as shown in figure 14, communicate with governments at any level on behalf of members. Participation in government relations are undetermined for 23.2 percent of associations.

Provincially, 50 percent of associations across the country participate in government relations, with higher percentages in provinces where there are fewer associations. About five out of thirteen international associations interact with government and four out of ten national associations do.

The degree to which associations interact with government likely varies. Association mission statements and self-reported histories suggest that some associations were founded around public policy issues. These associations may be more oriented toward advocacy and public policy issues (Figure 14).

Thus the public-relations function of associations includes promoting the faith or pedagogical orientation of the associated schools (almost three-quarters of associations do so), marketing of member schools (almost a third do more than list member schools’ names and logos on their websites), and communicating on behalf of the sector to government (almost half were noted as doing so).

ADMINISTRATIVE OPERATIONS.

Assisting administrative operations is the third most common function observed in this study. These activities are divided into two subcategories: administrative policy development and quality assurance support.

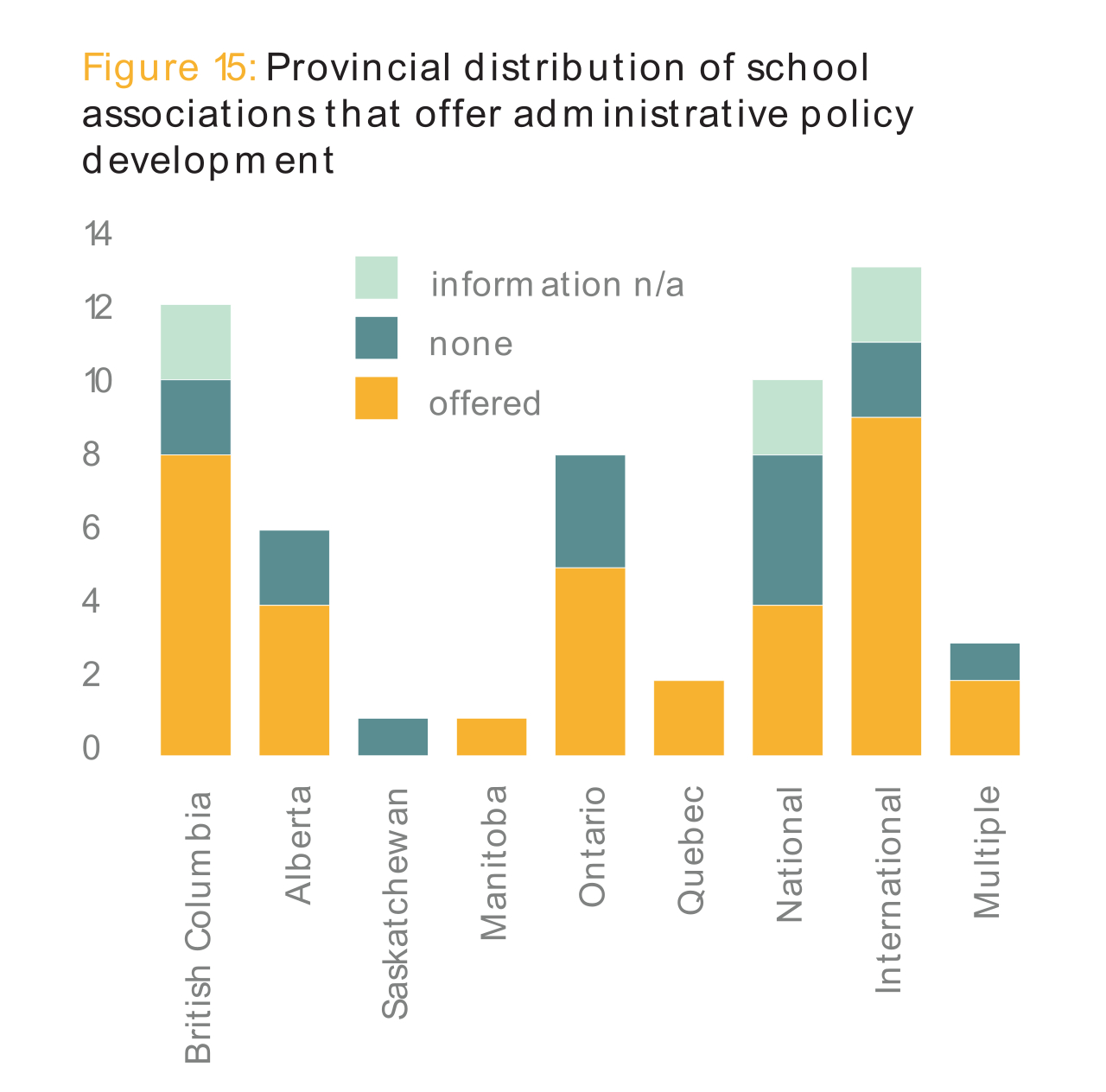

Administrative policy development

The activities in this subcategory include offering resources, templates, consultations, or symposiums that assist members with school policy development and implementation. Policies include governance, compliance, and the implementation of regulations and standards. Among the fifty-six associations identified, thirty-five (62.5 percent) assist with administrative policy development. See figure 15. Provincial associations generally reflect the overall average, with British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario hovering around the average. The share of national associations involved in administrative policy development is below average, at 40 percent, with a third of associations’ activities in this subcategory unknown. Among international associations, nine of thirteen provide administrative policy services (Figure 15).

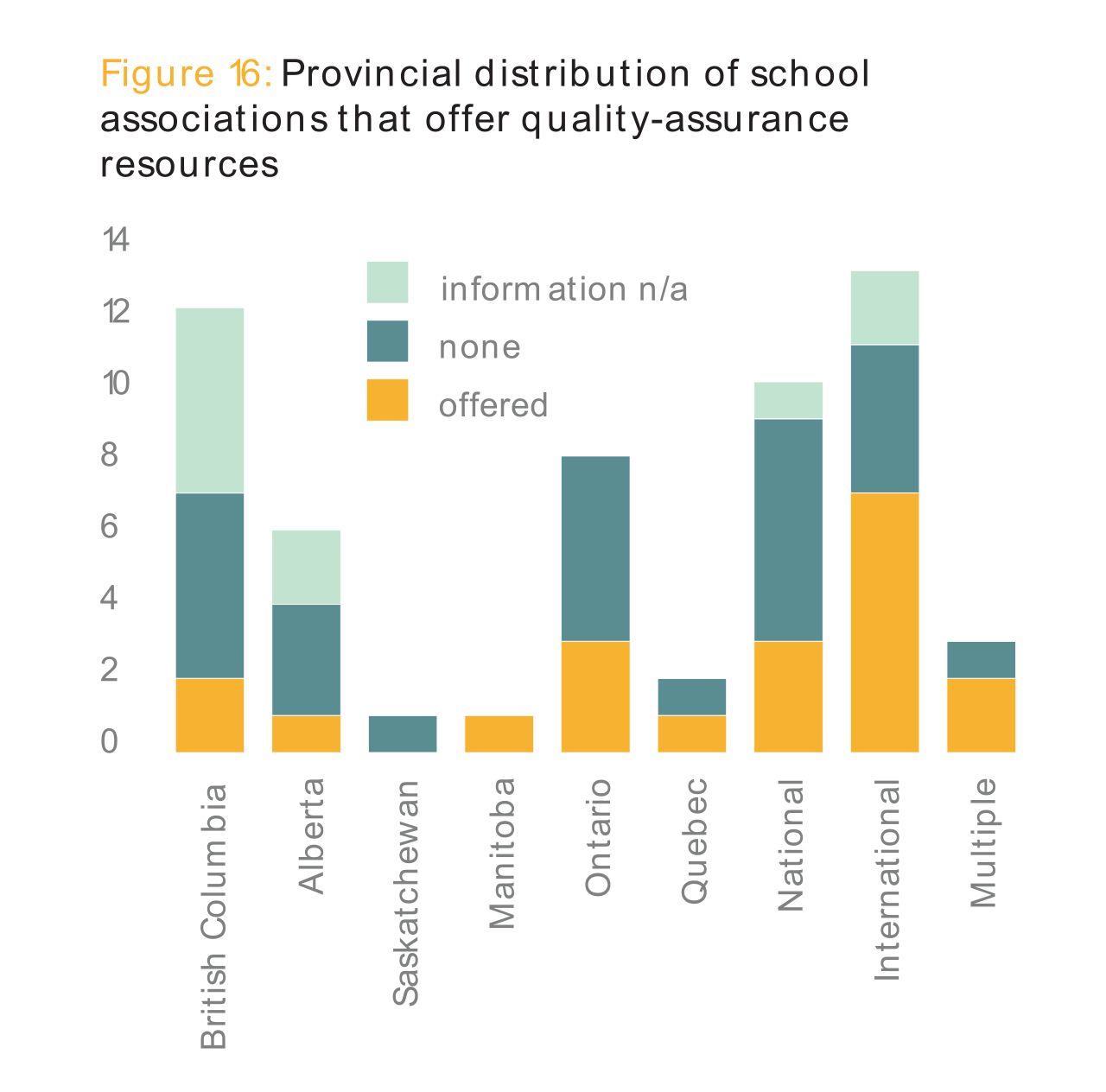

Quality assurance

Quality assurance activities are defined as inspections, evaluations, or consultations with member schools, or the provision of resources to assist member schools with quality assurance. School inspections and consultations are labour and resource intensive, likely preventing many associations from offering these services. We observe that some quality assurance measures require service fees in addition to membership fees.

Nonetheless, more than a third (35.7 percent) of associations offer quality-assurance provisions, as shown in figure 16. Only 16.7 percent of associations in British Columbia and Alberta are observed to offer quality assurance, although caution is warranted as the presence of such services are undetermined among 41.7 percent of associations in British Columbia and 33.3 percent in Alberta.

The national associations mirror the overall average of a third offering such quality assurances, while about half of the international associations offer quality-assurance resources (Figure 16).

Thus administrative operations were supported by independent school associations in at least two areas: administrative policy development, with almost two-thirds involved here, and quality assurance, with over one-third offering services in this area.

STUDENT SERVICES.

Student services has the smallest portion of associations providing services. Subcategories include facilitation of student events and student evaluation.

Facilitation of student events

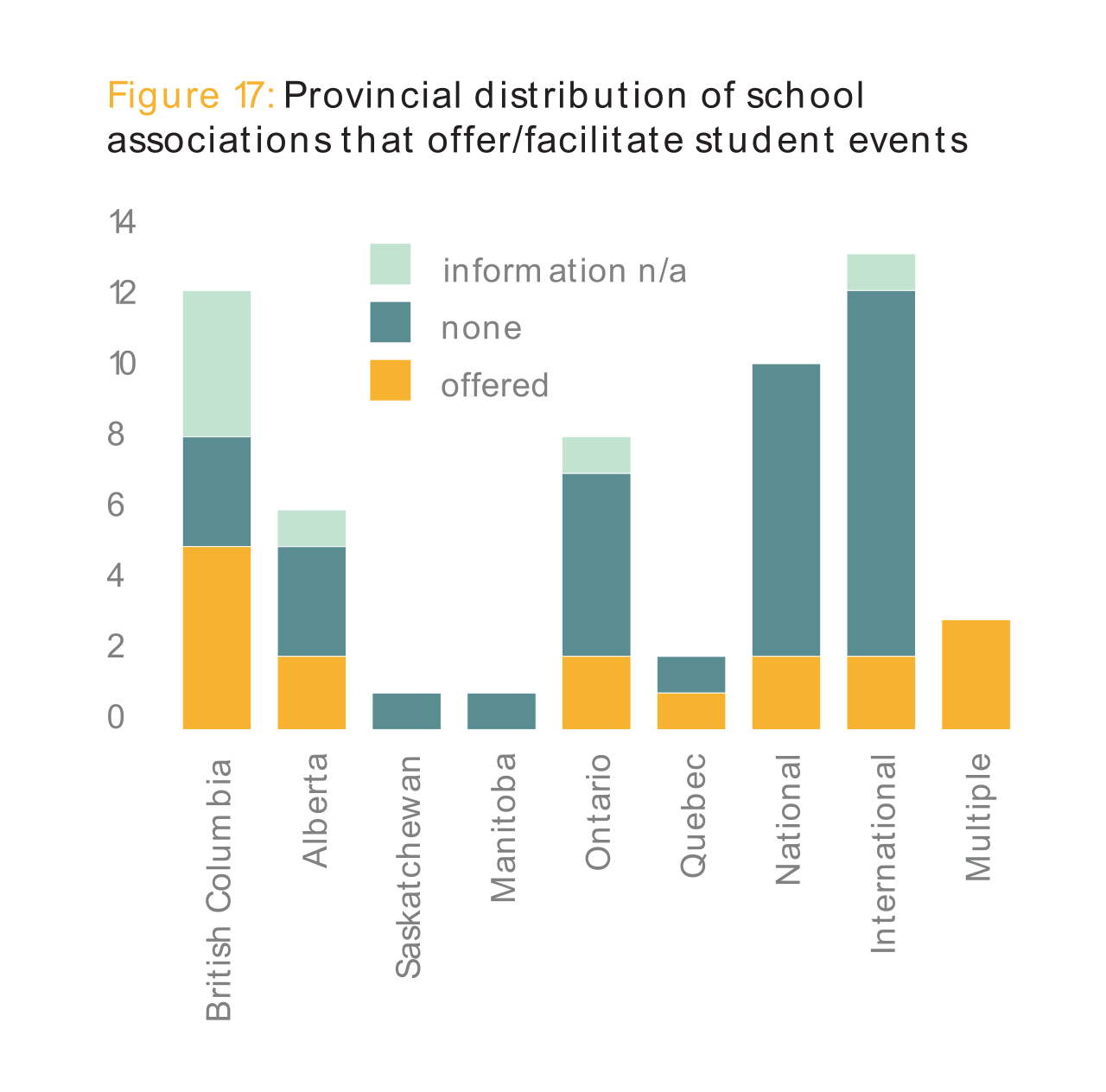

As can be noted from figure 17, approximately 30 percent of associations facilitate conferences, activities, and other events for students of member schools. While a small fraction of associations facilitate sports leagues or ongoing activities, many student activities are yearly events. Student activities can be expensive to facilitate, and travel costs can be prohibitive. International associations (15 percent) and national associations (20 percent) have the smallest shares of associations facilitating student events. British Columbia has the largest share, with 41.7 percent of associations offering or facilitating events (Figure 17).

Student assessment

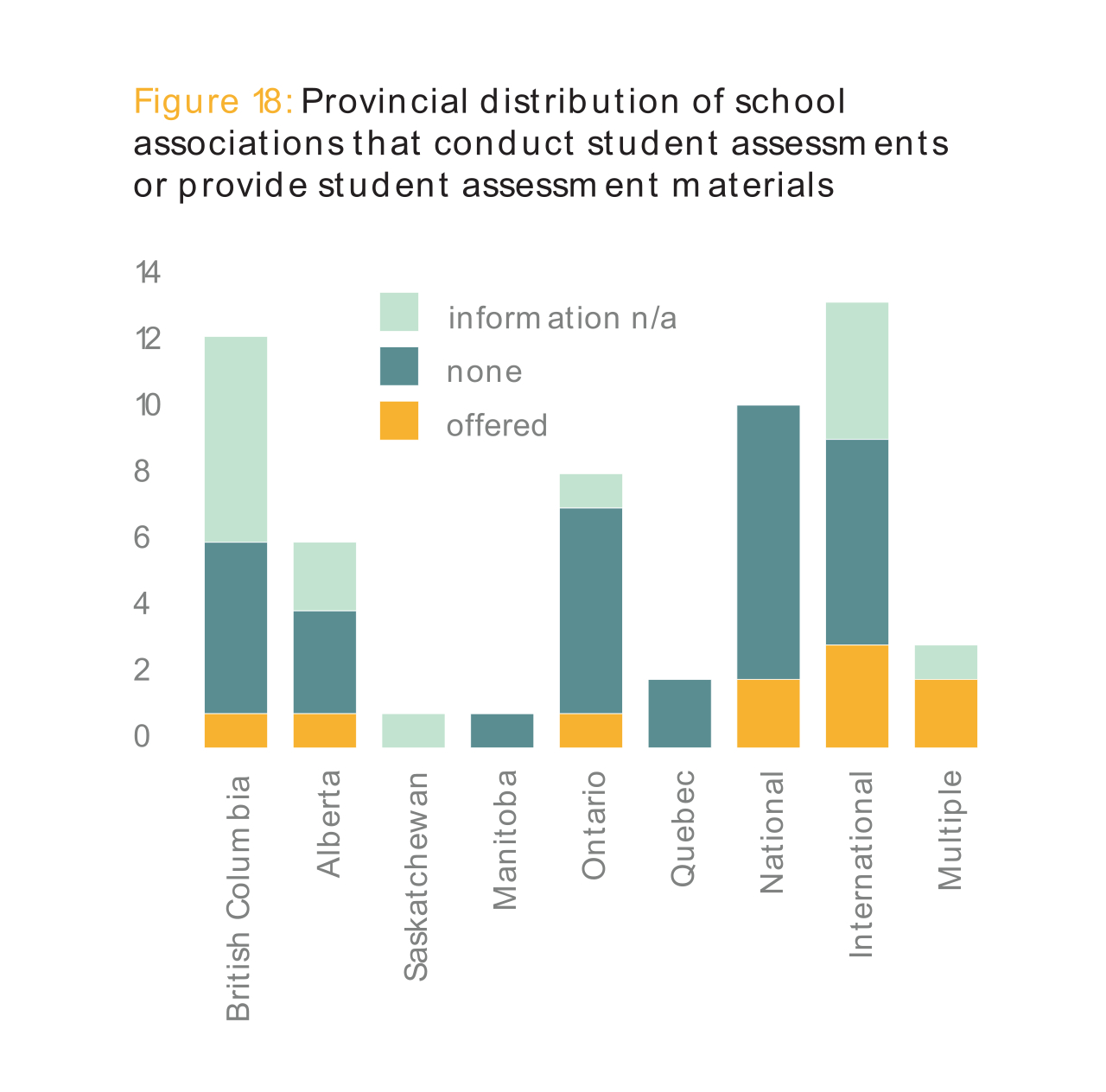

Only ten of fifty-six associations, as shown in figure 18, conduct student assessments or provide materials or discount access to student assessment materials. Student assessment activities are undetermined for about 27 percent of associations. Many provinces have standardized or province-wide testing, although independent schools often have to opt in and pay significant fees to participate. Whatever the case may be, less than 18 percent of associations provide standardized tests or assessment materials (Figure 18).

SUMMARY OVERVIEW OF ASSOCIATIONS’ ACTIVITIES

The mapping of associations’ activities focuses on services observed from publicly accessible websites. Not mapped here are the networks and informal knowledge transfers among members facilitated through association membership. We acknowledge that the relational capital developed and exchanged between association members is an important feature of membership. Measuring this capital is beyond the scope of this paper.

The provision of professional development is one of the significant contributions of associations. While the largest portion of associations provide professional development resources to educators (84 percent), many associations (about two-thirds) provide professional development to administrators and principals as well as trustees and board members (about a third). Fully 89 percent of associations provide some measure of professional development.

A notable aspect of the associations’ activities concern the advocacy of religiously and/ or pedagogically oriented education. Almost three-quarters (73.2 percent) of associations participate in this type of promotion. We have shown above that independent schools often hold membership in multiple associations, including those with no faith or pedagogical orientation. This indicates that these independent schools seek broader networks beyond their stated faith or pedagogical orientation. In addition, almost two-thirds of the associations (for which evidence was available) participated in government relations, suggesting that the associations play an important role in representing the independent school sector to government agencies and bodies.

A significant role of associations is administrative operations support. About 63 percent of associations offer policy resources, templates, and consultations. We also noted that a third provide quality-assurance services such as inspections or evaluations.

Of the four categories of activities mapped in this study, student services are the least likely for activity associations to participate in—less than one in five. It could be speculated that independent schools utilize other avenues to fulfill student-service needs or that those activities most closely aligned with students are delivered at the local level rather than through the more removed associational level.

PROVINCIAL FUNDING

DOES THE PRESENCE of funding for independent schools affect the functions of independent school associations? Our preliminary analysis here suggests that this may be the case.

As mentioned earlier, in Canada education is under provincial jurisdiction, and thus the statutory environments for the operation of independent schools varies by province. Five provinces offer some funding directly to qualifying independent schools toward the operational expenses (not capital expenditures) of the education they provide. Typically, funding is calculated based on a percentage of what is offered to a local public school in the district in which the independent school operates. Depending on school type, British Columbia typically offers 35 or 50 percent of the per-pupil amount, Alberta 60 or 70 percent, Saskatchewan between 50 and 80 percent, Manitoba about 50 percent, and Quebec about 60 percent. Essentially Ontario, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador offer no funding for independent schools. 7 7 In the analysis in this paper we label the first five provinces “Funded” and the second five “Non-Funded.”

We noted that the vast majority (75.8 percent) of the provincial associations were headquartered to serve in provinces that offer funding for independent schools. This in itself is a finding worth noting and leads to asking the question of whether the presence of funding stimulates the presence of more associations and of more associational activity. To be specific, recall that only eight associations were found to be headquartered in Ontario and none in the four Atlantic provinces, meaning that less than a quarter (24.2 percent) of all provincial associations in Canada are located in the non-funded provinces. Given that 52.3 percent (in 2013/2014) of independent schools in Canada are located in those five provinces, 8 8 Deani Van Pelt, Sazid Hasan, and Derek J. Allison, A Diverse Landscape: Independent Schools in Canada (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2016). and almost half of independent schools in Canada (49.3 percent) were located in Ontario alone, this finding does lead to further questions.

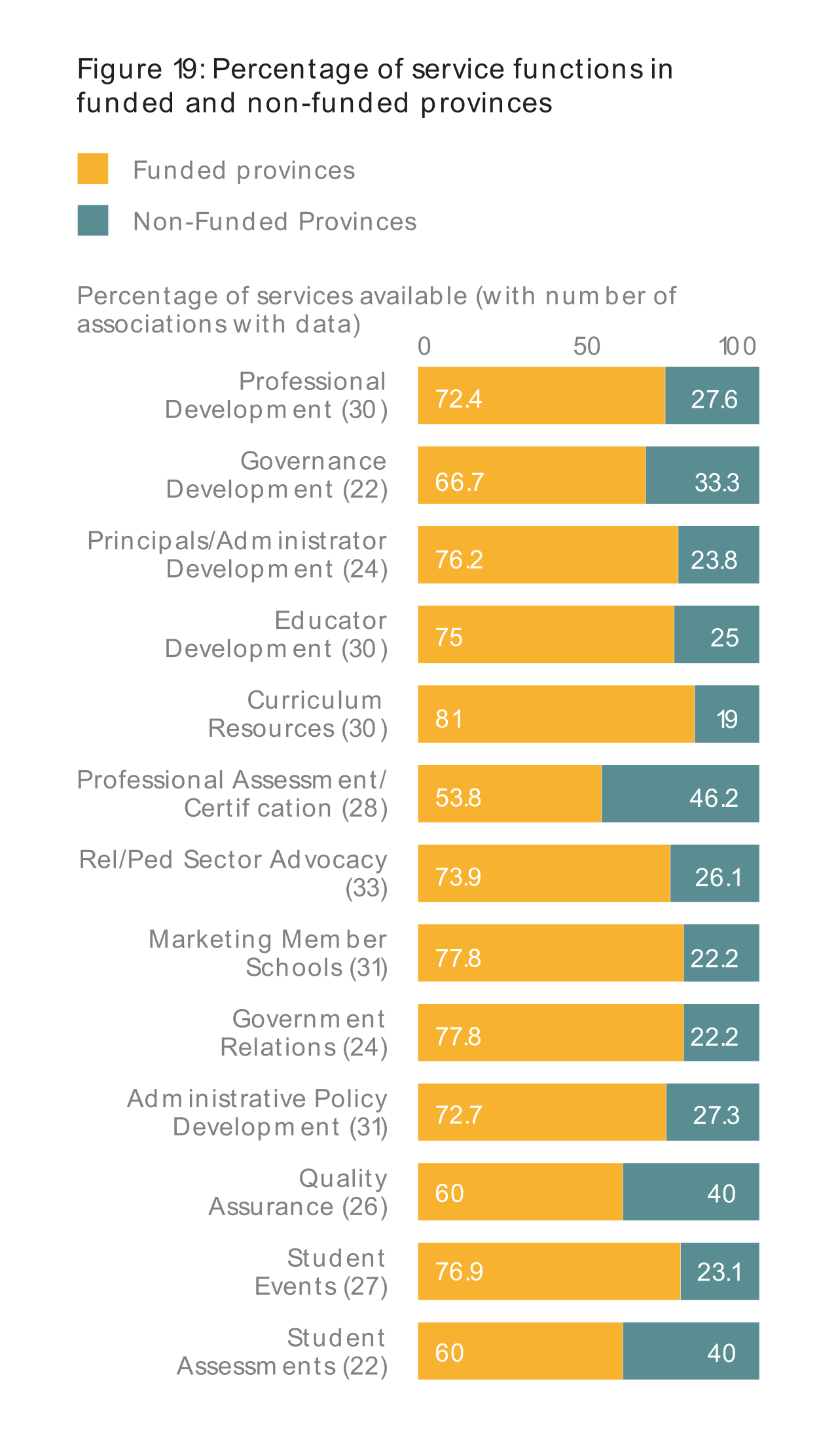

Second, when all associational activities are considered as a whole, given that the majority of provincial associations are located in funded provinces, it is then no surprise that more of each type of association activity or function would be present in the funding provinces. The distribution of the specific services across funded and non-funded provinces (despite the expected imbalance given that more associations are in funded provinces) are still worth noting. Consider the following. As might be expected given that about three-quarters of all provincial associations are in funded provinces, about three-quarters of most associational activities offered are in funded provinces. Stated the other way, about 25 percent are offered in the non-funded provinces. This is shown in figure 19. Four functions, however, stand out slightly from this trend in that a higher share of that function is offered in the non-funding provinces, and one stands out because a lower share is offered in the non-funding provinces. Consider the first four. A slightly higher share (from 33.3 to 46.2 percent) of the governance development, professional assessment/certification, quality assurance, and student assessment take place in the non-funded provinces. The one that stands out in the other direction is curriculum resources, at only 19 percent occurring in non-funded provinces. So, we can conclude that in non-funded provinces more associational quality-control activities take place and less curriculum resourcing. Stated another way, with less government regulation, more industry-initiated quality indicators are offered and more curricular diversity (thus less specific curriculum support) may result (Figure 19).

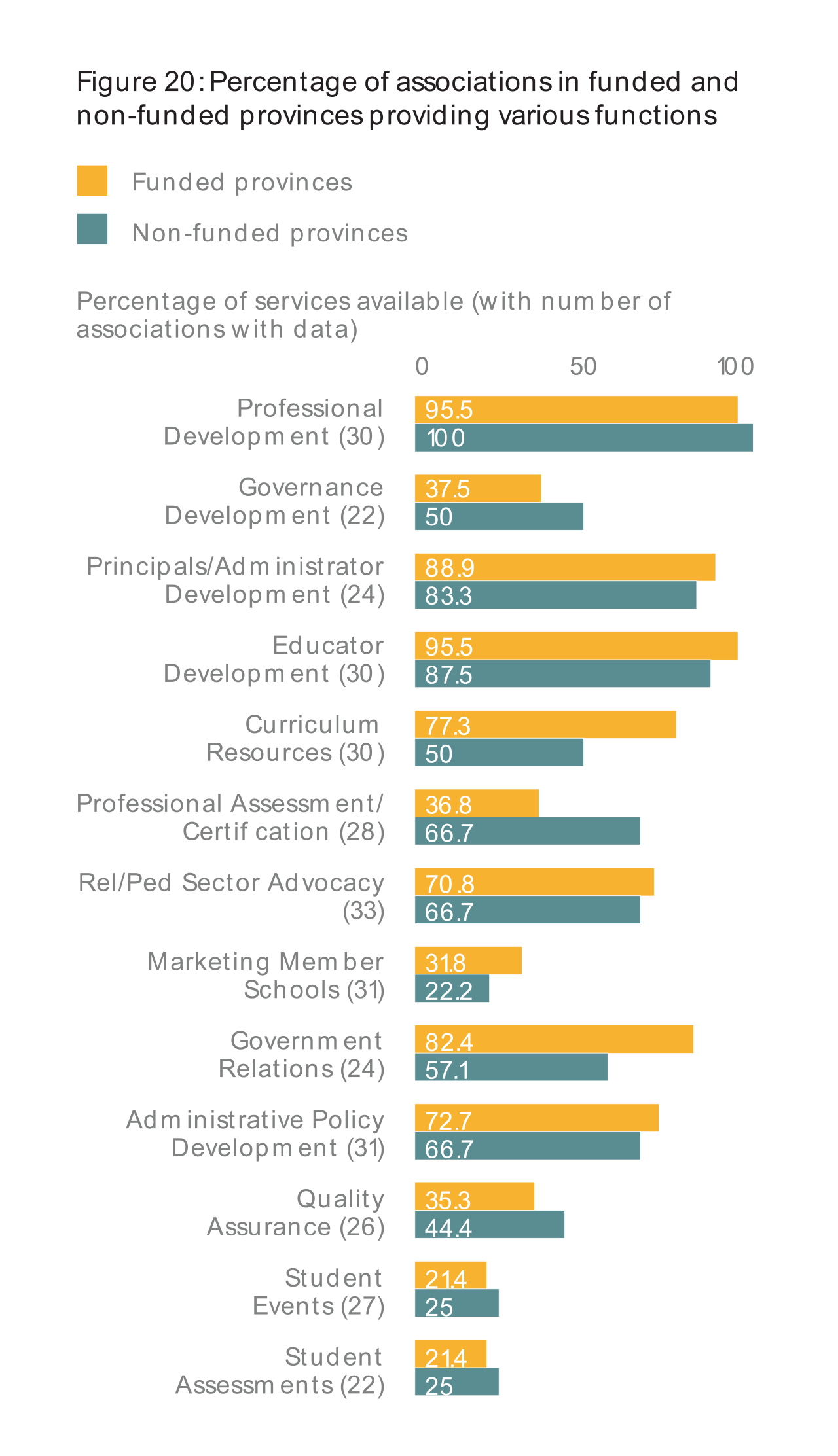

A slightly different set of cross-tabulation calculations assists in our addressing these questions. Figure 20 considers the activities in an alternative direction. The associations in funded provinces as a whole are considered first, and the share of those associations offering each of the various services are considered. Then the non-funded provinces are considered as a whole, and the share of those that offer each service. By comparing across the funded and non-funded categories, we note that once again the non-funded stand out with a notably higher share offering governance development (50.0 percent versus 37.5 percent) and professional assessment and certification (66.7 percent versus 36.8 percent) as well as the somewhat higher quality assurance (44.4 percent versus 35.3 percent); and, in the other direction, we note that only half of associations in non-funded provinces offer curriculum support, while more than 77 percent in funded provinces do. These findings appear to reinforce the direction of the findings in the last paragraph.

Of potential further interest from this cross-tabulation analysis, government relations stands out as showing one of the most dramatic differences between association activities in funded versus non-funded provinces. Fully 82.4 percent of associations in funded provinces are involved in government-relations activities, while the comparatively lower share of 57.1 percent of those in non-funded provinces are involved in government relations. This may indicate a slightly more inward service orientation of associations in non-funded provinces and a more external posture of those in funded provinces. It could also be an unsurprising result of the engagement required when government funding is involved (Figure 20).

Thus the cross-tabulation analysis shows that the vast majority of the support and professional development offered by associations occurs in provinces that provide funding for independent schools. Even though we’d expect that to be the case given there are more associations in those funded provinces, it is nevertheless a key point to note in its own right.

It appears that associations are as likely to be involved in pedagogical or religious-sector advocacy regardless of whether a province offers funding for independent schools. Indeed, twothirds of associations in provinces with no funding (66.7 percent) and just slightly more (70.8 percent) in provinces with provincial funding are involved in either advocating for either the pedagogical or religious orientations of their associated schools.

Another point on which funding appears to make little difference is that fully 100 percent of all associations (for which we have data) in non-funded provinces and 95.5 percent in funded provinces (not shown) are involved in professional development.

One final point worth noting is that associations in provinces with funding more frequently market their member schools (three of every ten), while only two of every ten do so in provinces without funding. Certainly of all the associations that do market member schools, more than three-quarters are located in provinces with partial funding.

Thus we might conclude that funding does encourage associations to behave differently, and it appears to influence the activities of associations.

The presence of partial provincial funding correlates with a higher presence of associations. Does it stimulate their presence? Or is the presence of funding stimulated by their presence and impact? Despite only about half of the independent schools in Canada being located in those provinces, fully three-quarters of the provincial associations were located in provinces where funding is available for independent schools. As a consequence, although there were some exceptions, about three-quarters of each type of associational function were noted in provinces that offer funding.

The preliminary analysis we offer here found that associations in provinces without funding may be more involved in self-regulation (teacher certification, quality assurance, and governance development) while the presence of funding seems to stimulate more collaboration in school marketing and curriculum support, as well as more engagements with government (government relations). Associations across provinces, regardless of provincial funding, appear similarly active in promoting a pedagogical/religious orientation in their members, in developing administrative policies, and in professional development of educators.

RELIGIOUS ORIENTATION

WE ALSO INVESTIGATED whether religiously oriented associations offer services distinct in any way from those offered by non-religiously defined associations. Recall that almost half (44.6 percent) of all associations had a religious orientation.

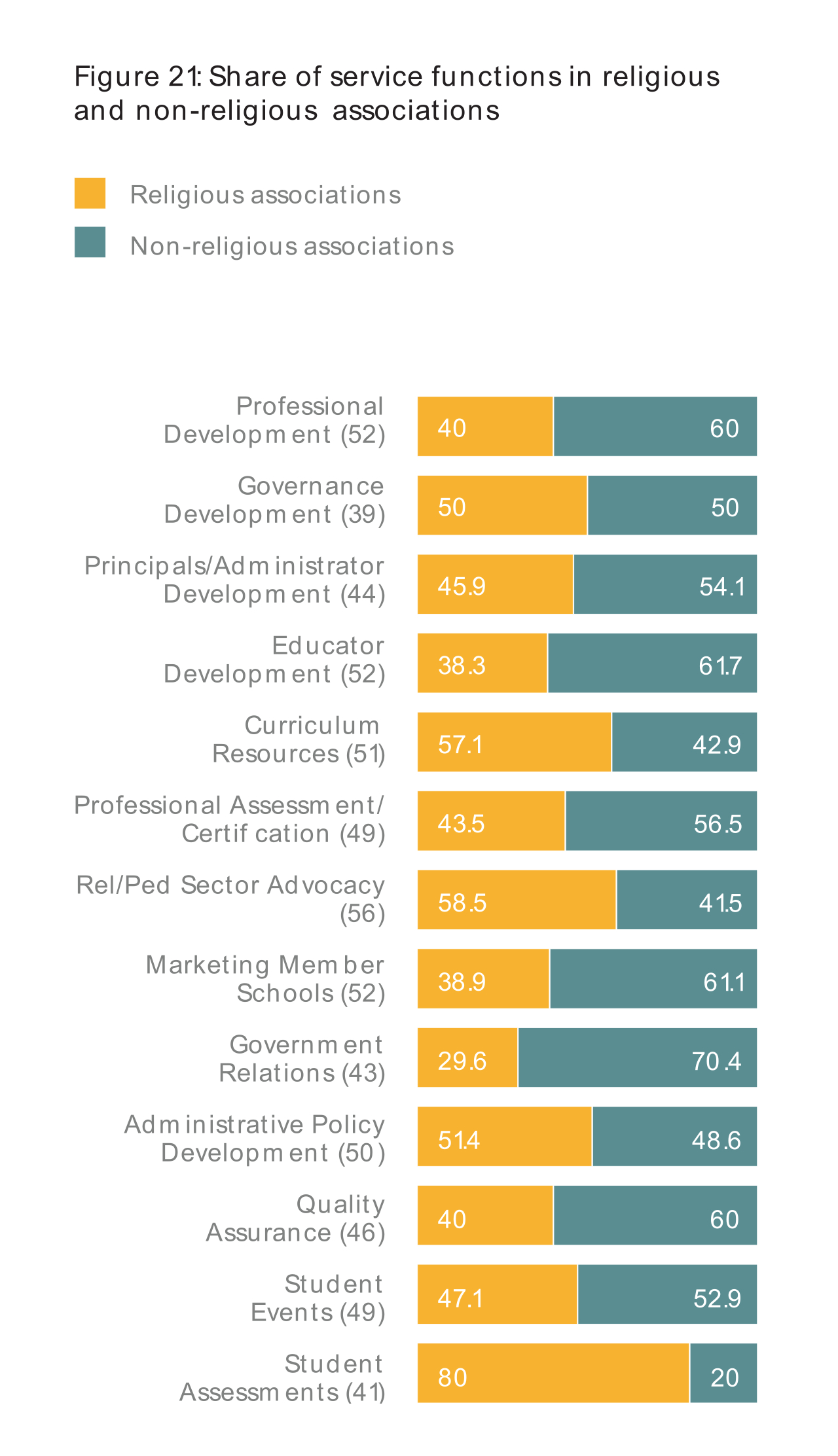

Consider first each of the functions and the share of each function offered by religious versus non-religious associations. We found, as shown in figure 21, curriculum resources (57.1 percent) and student assessment (80 percent) to be offered by a higher share of religious associations, and 58.5 percent of sector-advocacy function was at religiously oriented associations. On the other hand, a higher share of several other functions was undertaken by non-religious associations. Fully 70.4 percent of associations reporting government relations were non-religious associations. As well, 61.1 percent of associations that marketed their member schools were non-religious associations (Figure 21).

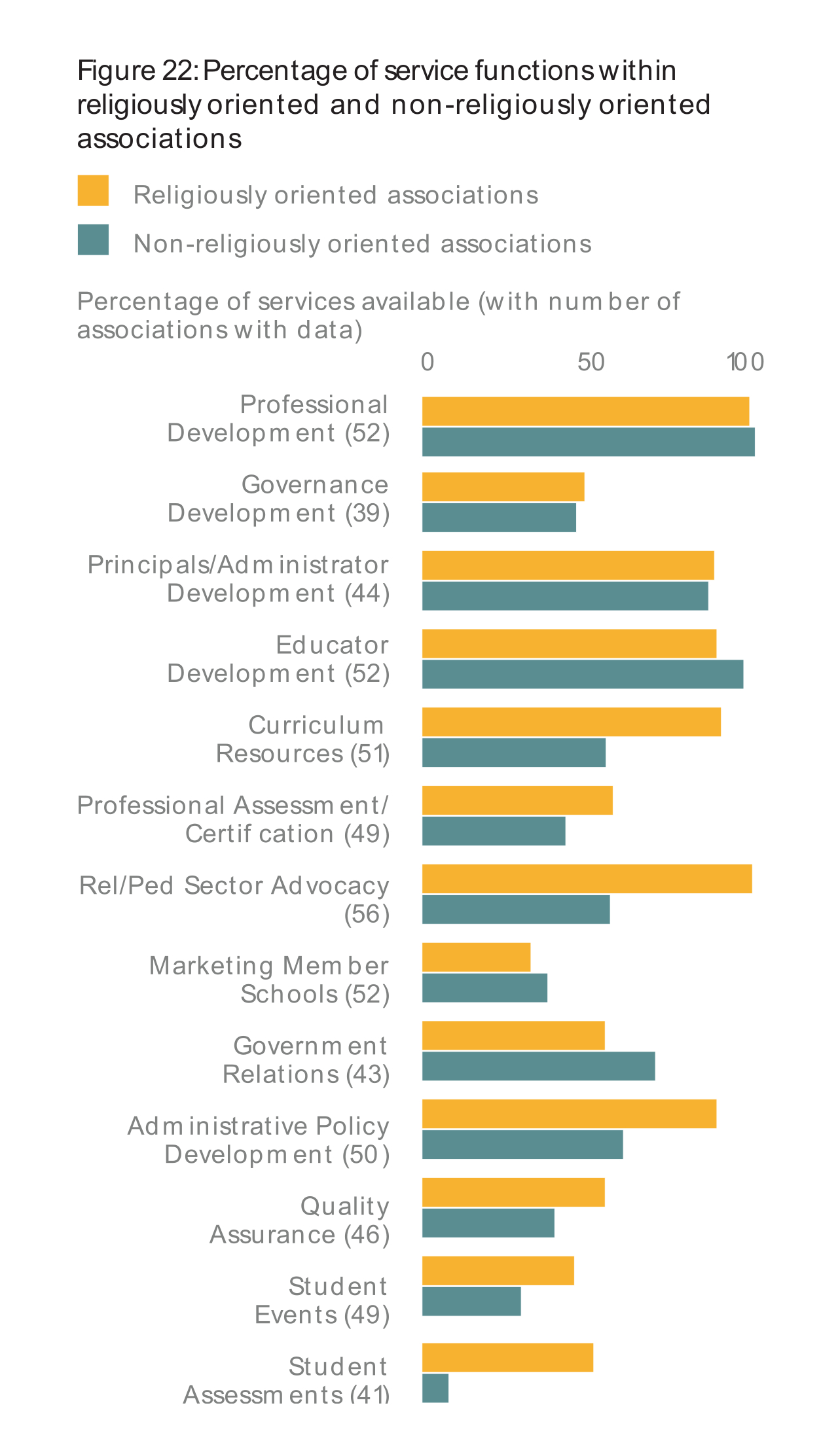

We then considered religiously oriented associations as a group and the non-religious associations as another group and investigated what percentage within each group offered the various service functions. In general, a higher share of the religiously oriented associations was involved in almost all service functions. For example, as shown in figure 22 below, a higher share was involved in offering curriculum resources (87 percent versus 53.6 percent), professional assessment and certification (55.6 percent versus 41.9 percent), sector advocacy (96 percent versus 54.8 percent), administrative policy development (85.7 percent versus 58.6 percent), quality assurance (53.3 percent versus 38.7 percent), student events (44.4 percent versus 29 percent), and student assessment (50.0 percent versus 8 percent). There were some areas in which the non-religious associations showed a higher share of involvement. For example, although almost all associations in both groups offered educator development, the non-religious groups were slightly higher at 93.5 percent (compared to 85.7 percent). A higher share was also involved in government relations (67.9 percent versus 53.3 percent) (Figure 22).

Associations that serve religiously oriented schools differ from those associations that are not defined by religion. Associations that are religiously oriented appear more involved in a larger variety of activities than those without a religious orientation. This preliminary analysis finds they are more likely to organize student events, assess students, assess professionals, offer administrative policy development, and be involved in sector advocacy. Both types of associations appeared as likely to be involved in professional development overall, and specifically in governance development and principal and administrator development, as well as in school marketing. Nonetheless, non-religious school associations were found to be more likely to be involved in professional development overall and government relations.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

ASSOCIATIONS THAT EXIST to serve independent schools focus on strengthening the voice of the independent school sector, increasing capacity within the independent school sector, and promoting values and standards relating to faith, pedagogy, or other aspects of diverse forms of quality non-government K–12 education.

Fully thirty-three of the fifty-six independent school associations analyzed in this study (59 percent) focus on provincial and regional membership, with British Columbia showing the largest portion of associations, with twelve. Ontario (eight) and Alberta (six) have the next largest portion of associations with headquarters in those provinces. Although some associations serve independent schools in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland and Labrador, no associations meeting our criteria are headquartered in the Atlantic provinces. Quebec is an outlier among the large provinces, with only two associations.

The interprovincial and international orientation of 41 percent of the associations in Canada (twenty-three of fifty-six) is worth noting. Two of every five associations serve a national or global membership. This could well be an indicator of the coherence and collaboration across provincial and national boundaries. It could also indicate that the educational ideas, innovations, and issues addressed are more likely to travel outside of the individual provinces. On the other hand, it could simply be a function of the small size of the independent school sector in each province, and larger-scale collaboration is only possible with moving beyond one’s province. In any event, this finding may be worth more study given the otherwise provincial jurisdiction for education delivery in Canada.

The vast majority of independent school associations represent, even reflect and embody, a religiously or pedagogically distinct identity. Fully 75 percent of the associations have an explicitly religious and/or pedagogically defined orientation. Nearly half (44.6 percent) of all associations (twenty-five in total) have a faith orientation, and 32.1 percent (eighteen in total) are pedagogically oriented, with one association having both orientations. But that does not mean the associations operate in isolation from other orientations. More than a third of the associations without pedagogical definition had member schools that were pedagogically defined. Similarly, more than half of the associations without religious definition had religiously defined member schools. It is clear from this analysis that independent schools seek broader networks beyond their stated faith or pedagogical orientation.

Our analysis focused on four key functions that the independent school associations serve: professional development, public relations, administrative operations, and student services.

The key professional-development activities and services most likely to be offered by independent school associations are services to the educators (almost 84 percent of associations). Even so, the majority of associations (more than 66 percent) also provide development activities for principals and school administrators. Board and governance development was offered by close to a third of all associations. Curriculum support was most prevalent in British Columbia, with over 90 percent of associations involved; overall, curriculum support was noted in three-fifths of all associations. Assessments for quality or certification are most prevalent in Ontario associations and overall were noted in over two-fifths of all associations. In all, professional development of a variety of types is key to the function and services of the vast majority of independent school associations.

Public-relations functions of associations were noted and analyzed in three activities: Promoting the religious or pedagogical orientation of the associated schools (almost three-quarters of associations do so); marketing of member schools (almost a third); and communicating on behalf of the sector to government (almost half were noted as doing so).

Administrative operations were supported by independent school associations in at least two areas. Almost two-thirds of the associations were involved in administrative policy development, and over a third offered quality-assurance services.

Student services showed the least emphasis across the associations. Less than a third were involved in facilitating student events and programs, and less than a fifth in student assessment.

A comparison of the provincial associations in provinces that offered funding for independent schools to those provinces that did not fund independent schools showed more associational activity in funded provinces. Certainly, it appears that the presence of funding may well stimulate the presence of associations. It could be the case, alternatively, that strong associations contributed to the presence of funding. Despite only about half of the independent schools in Canada being located in those provinces, fully three-quarters of the provincial associations were located in provinces where funding is available for independent schools. As a consequence, although there were some exceptions, about three-quarters of each type of associational function were noted in provinces that offer funding.

Does provincial funding for independent schools make a difference on association activity? The preliminary analysis we offer here found that associations in provinces without funding may be more involved in self-regulation (teacher certification, quality assurance, and governance development), while the presence of funding seems to stimulate more collaboration in school marketing and curriculum support as well as more engagement in government relations. Associations across provinces, regardless of provincial funding, appear equally as active in promoting the pedagogical or religious orientation of their members, in supporting administrative policy development, and in professional development of educators.

Does the presence of a religious orientation make a difference in association activity? Associations representing religiously oriented schools appear to be more likely to be involved in a larger variety of types of activities than those serving non-religious schools. This preliminary analysis finds they more frequently are involved in sector advocacy, offering administrative policy development, and organizing student events, assessing students, and assessing professionals. Both types of associations, religiously oriented and non-religiously oriented, appeared as likely to be involved in professional development overall, and specifically in governance development and principal and administrator development, as well as in school marketing. Nonetheless, non-religious school associations were found to be more likely to be involved in professional development and government relations.

In all, independent schools in Canada, although independently owned and operated, do not function in isolation. Fully 56 associations varying in membership from 1 to 298 schools served the independent school sector in offering at least two of four functions (professional development, public relations, administrative operations, or student services). Independent schools, through their associations, tend to collaborate cross-provincially, nationally, and internationally, as fully two of every five associations are national or international in scope. Provinces with funded independent schools are host to more associations. Associations in non-funded provinces tend to be more involved in more self-regulatory quality measures. Religiously oriented associations are involved in more varieties of internally supportive and development functions, while non-religiously oriented associations may be involved in fewer functions but prioritize educator professional development and external government relations. Independent schools do not operate in isolation, but rely on associations to enhance the delivery of quality education. This study is a first attempt to understand how associations function in the independent schools landscape.

References

Accelerated Christian Education

Alberta Association of IB World Schools

Agency for French Teaching Abroad

“Associate Member Group of FISABC.” Federation of Independent Schools Associations British Columbia.

fisabc.ca/who-are-we/member-associations/associate-member-group

Association of Christian Schools International (Eastern Canada)

Association of Christian Schools International (Western Canada).

Association of IB World Schools.

ibo.org/contact-the-ib/associations-of-ib-schools

Association of Independent Schools and Colleges in Alberta

Association Montessori Internationale Canada

British Columbia Association of IB World Schools

Calgary Reggio Network Association

Cambridge Assessment International Education

Canadian Accredited Independent Schools

Canadian Adventist Teachers Network

Canadian Association of Montessori Teachers

Canadian Catholic School Trustees Association

Canadian Council of Montessori Administrators

Canadian Federation of University Preparatory Schools

Catholic Independent Schools Diocese of Prince George

Catholic Independent Schools – Kamloops Diocese

Catholic Independent Schools Nelson Diocese

“Catholic Independent Schools of British Columbia.” Federation of Independent School Associations.

fisabc.ca/who-are-we/member-associations/catholic-independent-schools-britishcolumbia

Catholic Independent Schools Vancouver Archdiocese

Christian Schools Canada

Christian Schools International

csionline.org/christian-schools-international-members

Council of International Schools

Edmonton Christian Schools.

“Education.” Eglise Adventiste du Septieme Jour Quebec Conference

sdaqc.org/article/38/liens-utiles/home/ministries/education

“Education.” Islamic Circle North America

icnacanada.net/about-2/education

“Education.” Manitoba-Saskatchewan Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

mansaskadventist.ca/education-2

Fédération des Établissements D’enseignement Privés

Federation of Independent School Associations British Columbia

Independent Schools Association of British Columbia

Island Catholic Schools

League of Canadian Reformed School Societies in Ontario

“List of charities.” Canada Revenue Service

canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/charities-giving/charities-listings.html

Manitoba Federation of Independent Schools

National Association of Independent Schools

National Coalition of Girls Schools

“New Church Schools.” New Church

newchurchvineyard.org/schools/our-schools

North American Reggio Emilia Alliance

Oakville Independent Schools

“Office of education.” Seventh-day Adventist Alberta Conference

“Office of education.” Seventh-day Adventist Church in Canada

adventist.ca/departments/education

Ontario Alliance of Christian Schools

Ontario Christian School Administrators Association

Ontario Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

adventistontario.org/Directory/Schools.aspx

Ontario Federation of Independent Schools

Ontario Reggio Association

Our Kids

Prairie Association of IB World Schools

Quebec Association of Independent Schools

Round Square

Saskatchewan Association of Independent Church Schools

“Schools in Canada.” Muslim Association of Canada

macnet.ca/English/Pages/Schools-in-Canada.aspx

“Schools.” Maritime Conference of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

“Search the Charity Register,” Government of the United Kingdom

gov.uk/find-charity-information

Seventh-day Adventist British Columbia Office of Education

Society of Christian Schools in British Columbia

Sterling Education

The Association of Boarding Schools

The Canadian Reformed Teachers Association

The Prairie Centre for Christian Education

Torah Umesorah

Ummati

ummati.ca/index.phpoption=com_content&view=article&id=1&Itemid=101

Vancouver Reggio Consortium Society

vancouverreggioconsortium.ca/home.html