Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

This study concludes that during the early months of the COVID-19 global pandemic, students in independent Christian schools had opportunity for a better educational experience than their peers in government schools. Far fewer days of instruction were lost, and the curriculum remained well rounded; teachers stayed closely connected to each student; students requiring special education supports continued to be served; and communities, including board members and donors, contributed to the well-being of the school and its participants. This was accomplished without provincial funding, by ordinary families working together in community with dedicated educators and school leaders. The question remains whether this resilience is possible only in the short-term during a period of intense crisis, or whether it is in the nature of this sector and might have potential to play out over a longer period of extreme hardship.

Background and Approach to Study

In mid-March of 2020, all school buildings—of both public and independent schools—in Ontario and Prince Edward Island were required to close due to a global coronavirus pandemic. The buildings remained closed through the remainder of the school year. At the time, Edvance Christian Schools Association had eighty-one affiliate schools—all independent schools—in these two Canadian provinces. This paper reports how these schools pivoted from offering face-to-face education to remote learning from March to June 2020.

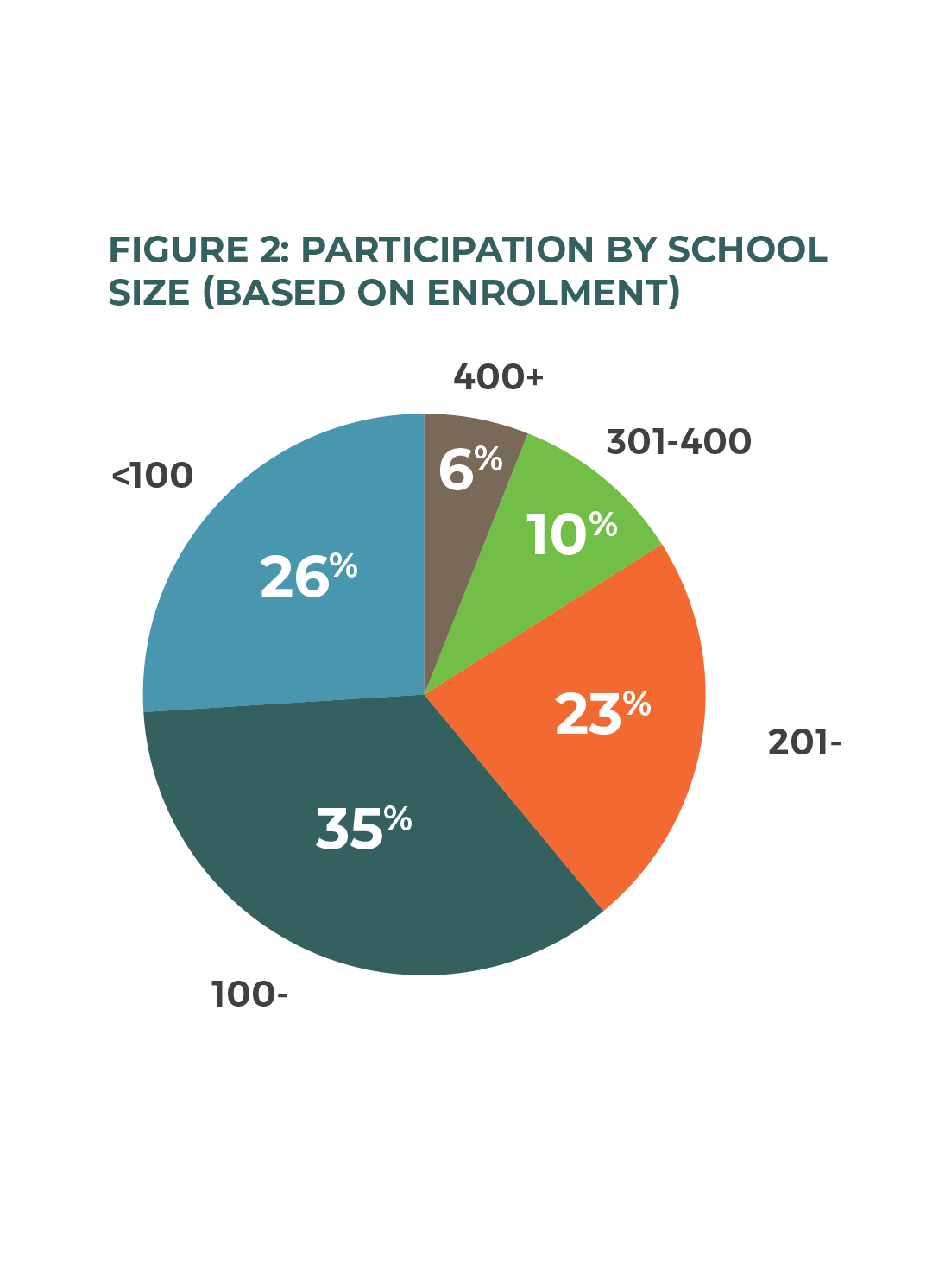

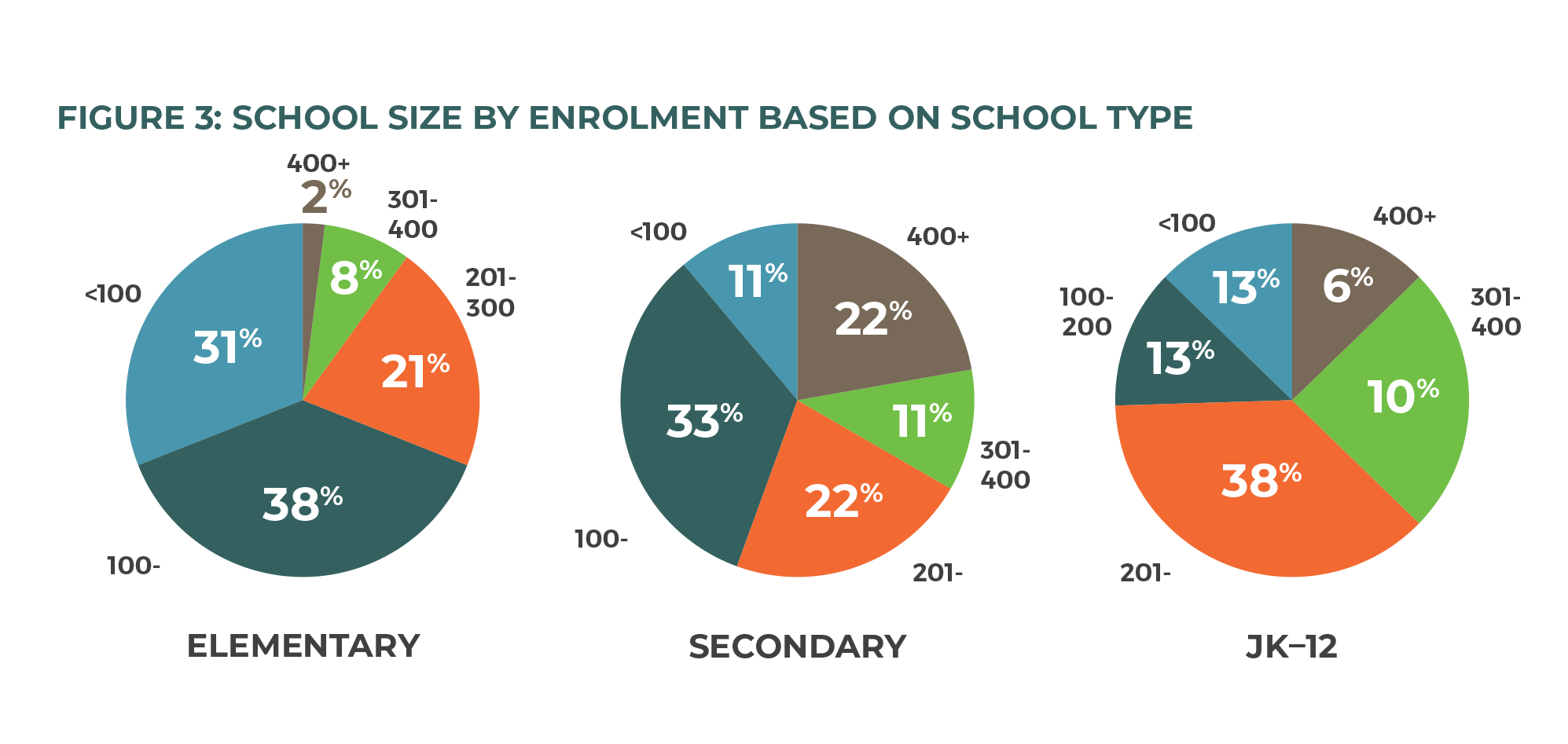

Eighty-five percent of the affiliate-school principals completed an online survey between June 9 and 16, 2020, and findings are reported here. The participants’ schools were elementary, usually serving junior kindergarten to grade 8 (75 percent); secondary, serving grades 9 to 12 (13 percent); or junior kindergarten to grade 12 schools (12 percent). Of the participating schools, 26 percent had fewer than one hundred students, 35 percent had between one hundred and two hundred students, and 39 percent had more than two hundred students.

Learning Continuity

Independent schools responded to the closures with agility. As schools pivoted quickly from face-to-face to remote learning, they also proved able to implement previously unused technology and tools to engage students in their learning activities and interactions.

Although the closures occurred during the March break, schools pivoted so quickly that almost half (48 percent) missed no instructional days and 84 percent missed just three days or fewer. The majority of schools exceeded the suggested instructional hours per week published by the Ontario Ministry of Education, and most reported multiple sessions per week for engagement in real-time lessons, activities, and meetings with students.

The schools also prioritized, and often enhanced, special-education services. Of the schools that offered special-education services (97 percent), most continued offering special-education support services for their students (88 percent).

At the nexus of the remote-learning journey were the educators. Principals reported many examples of the role that teachers played in the successful delivery of education during these first months of the pandemic. Teachers were critical to maintaining personal connections with each student and their families. Journeying together within the support community that surrounded the school appears to be another of the key strengths and benefits to families and students during the closures.

Business Continuity

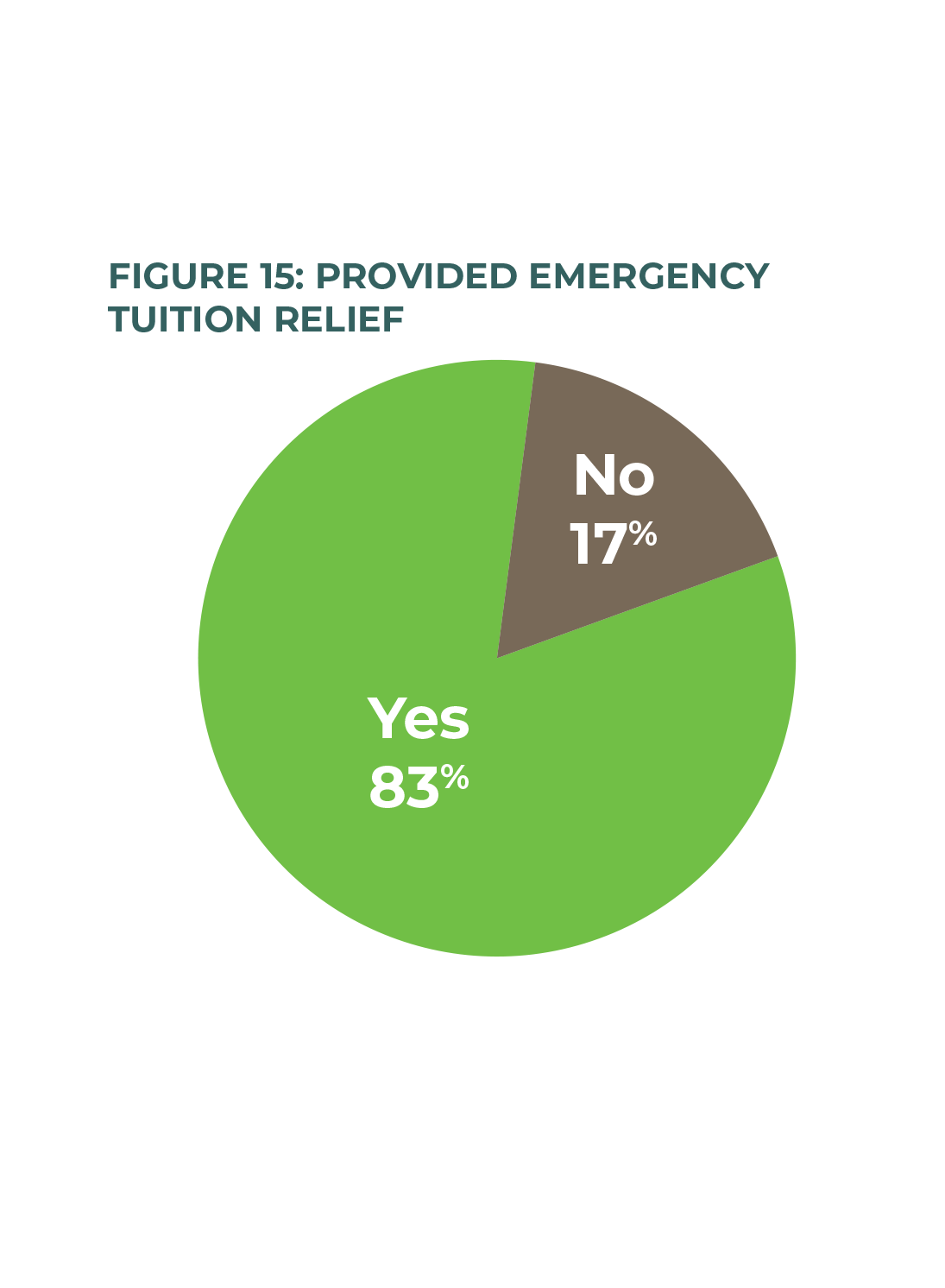

Independent schools in Ontario and Prince Edward Island receive no government funding for the education they provide. Instead, tuition and fundraising constitute the bulk of the revenues. Many surveyed schools (eight in ten) responded to the unexpected situation of the pandemic by offering emergency tuition relief to families who needed assistance. On average, some tuition relief was offered to eight families per school, with 457 total families benefiting.

In turn, the schools experienced the generosity of donors, with reports that donors gave in unexpected ways to tuition assistance and other needs during this period.

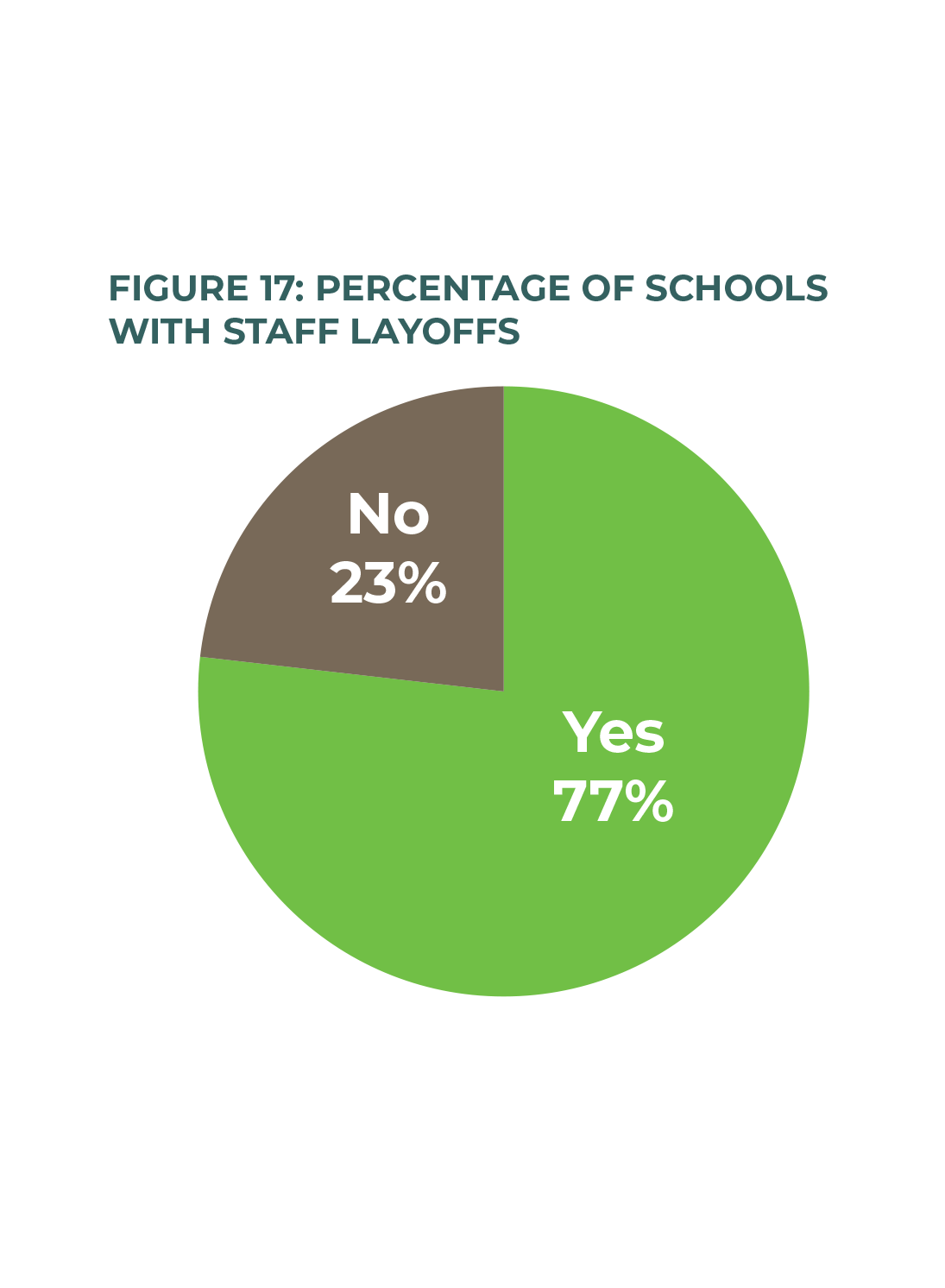

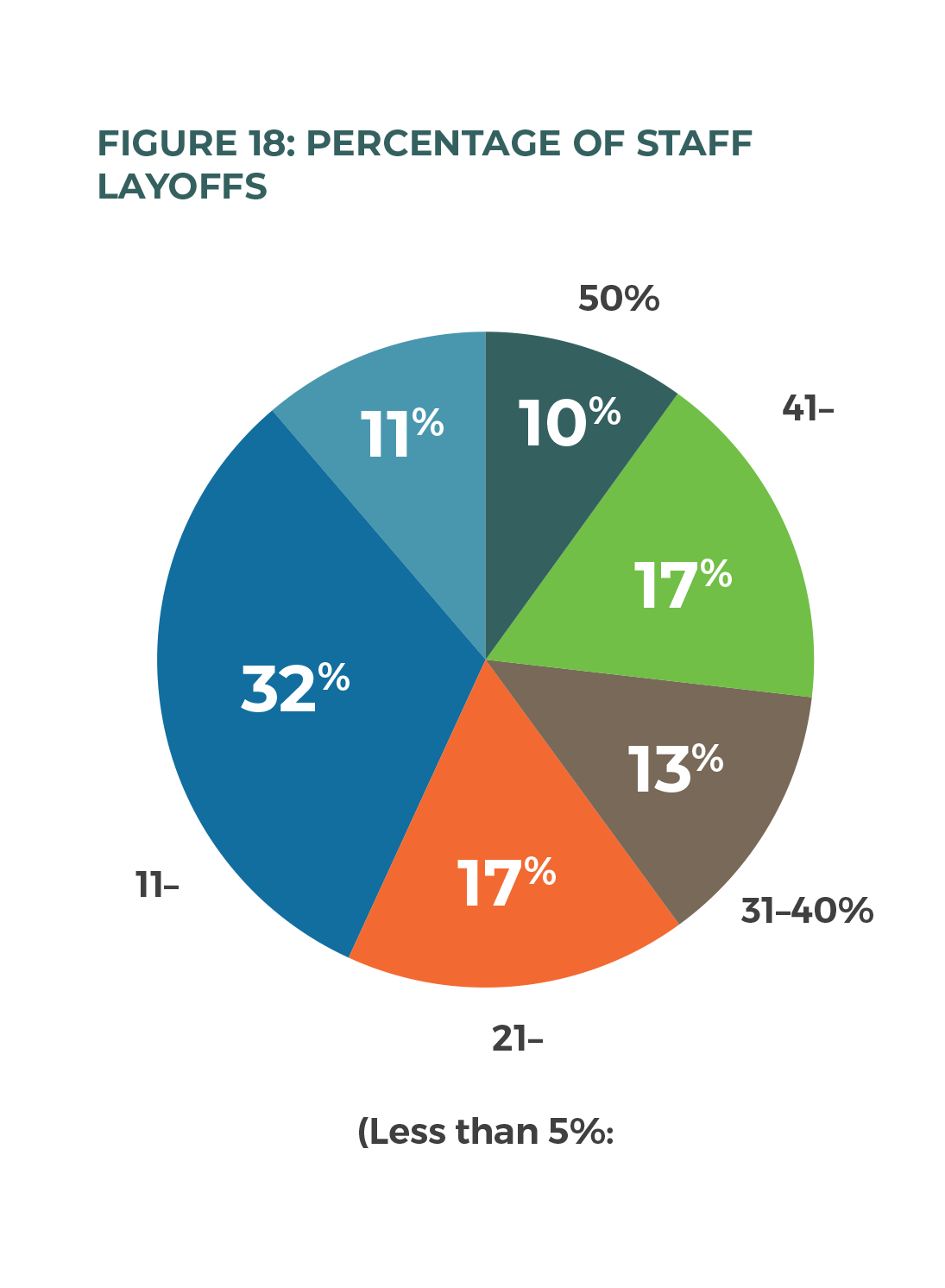

Still, independent Christian schools made difficult employment decisions in order to steward their expenses. Seventy-seven percent of participating schools laid off one or more staff members. Of those that laid off staff, 43 percent reported laying off 5 to 20 percent of their staff, and 47 percent reported laying off 21 to 50 percent.

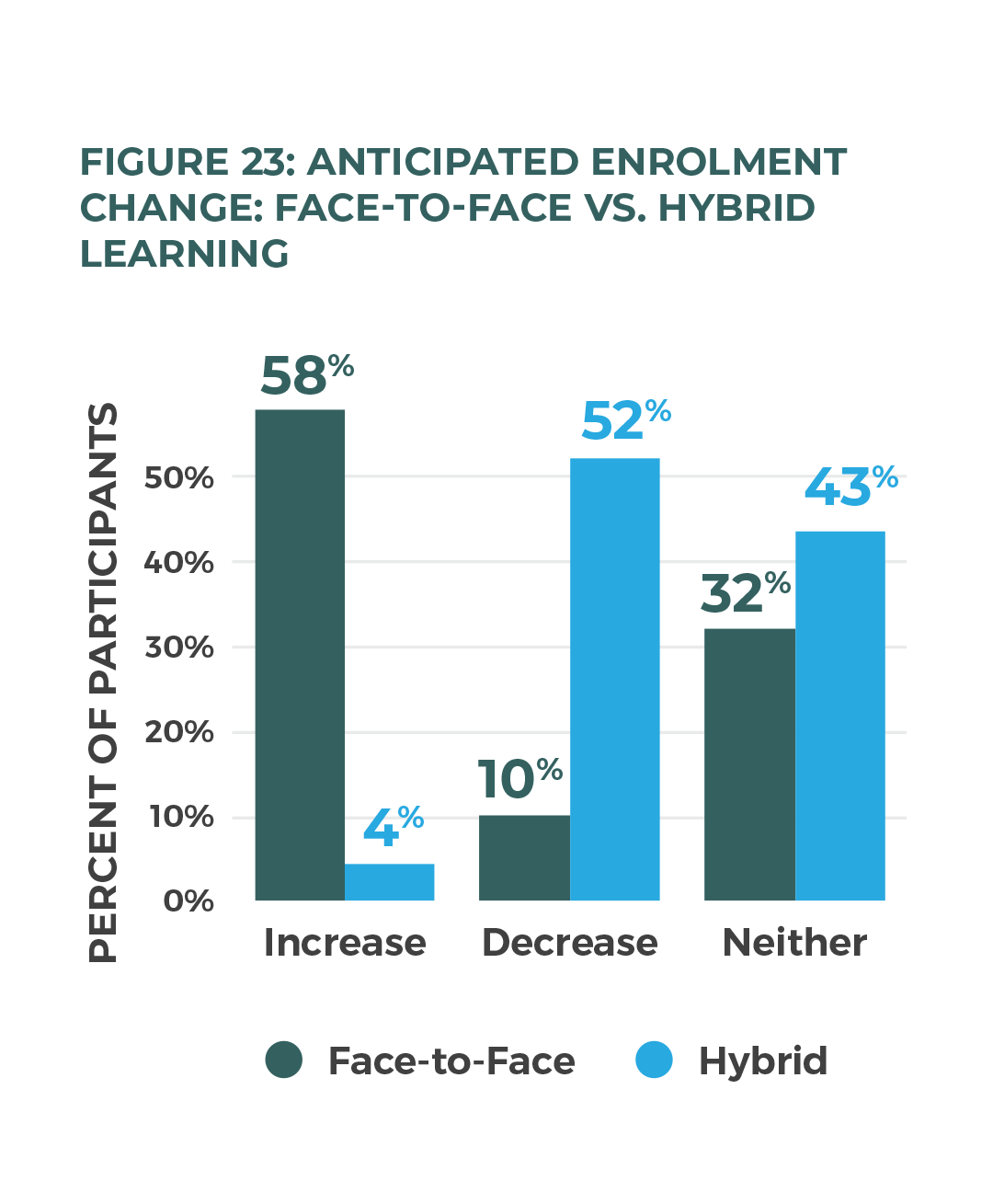

While the schools studied demonstrated their ability to maintain solvency in the short term, the principals viewed the future as less bright. Most (58 percent) anticipated growth if face-to-face schooling were to resume in fall 2020, whereas only 4 percent projected growth if the 2020–21 school year were to include continued remote or hybrid learning. Elementary-school principals, in particular, expected enrolment decreases should hybrid or remote learning still be in place in September.

Conclusions

In contrast to government schools—which, even with significant additional pandemic-related resources, provided little formal education from March 12 through September in Ontario—Christian independent schools demonstrated resiliency and agility in the short term, showing an ability to adapt to new requirements and circumstances while still continuing to offer an engaging and effective program of learning.

Concerns for the whole child remained evident even when physical presence was not possible. Student support continued. Communication was not one direction only, with a simple goal of keeping parents and students informed, but was designed to foster and enhance relations with parents and students.

This group of independent schools not only appeared financially resilient in the short-term but also demonstrated a posture of generosity. It is remarkable that with diminished revenues and smaller staffs, schools were still able to effectively deliver education that was widely appreciated.

Creative, timely, effective, and caring design and delivery of learning, using new media and platforms, characterized the impressive contribution of Christian school educators during the closures of spring 2020. Collaborative communities; capable, caring educators; and confident, engaged students appeared to be at the heart of the resiliency in these schools during this time. As of June 2020, however, principals were left wondering whether this situation could be sustained into another school year. This is a question that Cardus will examine in future research.

Introduction

The social, emotional, academic, and economic implications of the global COVID-19 pandemic will be studied for years to come, particularly the closures of many enterprises and venues that daily life and education ordinarily revolve around, and the prolonged, stay-at-home measures enforced on much of society. This report captures one part of that story, through a quantitative and self-reporting study of a small group of Christian schools in Canada in the initial months of the pandemic.

One effect of the pandemic was the sudden announcement of school-building closures in Ontario on March 12, 2020. 1 1 Office of the Premier, “Statement from Premier Ford, Minister Elliott, and Minister Lecce on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19).” Government of Ontario, March 12, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2020/03/title.html. Many Edvance affiliate schools were just completing their last day (or had one day remaining) before the start of one or two weeks of scheduled March break. The closure announcement resulted in altered or cancelled vacation plans and a pivot from (largely) face-to-face, in-classroom learning to emergency at-home learning.

This report aims to address the questions of whether and how learning and learning celebration (including graduation) continued in the sector and investigates the financial and business impact of the building closures. The study contributes to what is known about how independent Christian schools and their students fared in the early stages of the pandemic. 2 2 [1] Other helpful insights into the well-being of the sector include a series of qualitative, journalistic stories published in May and June 2020 in Convivium based on interviews with Christian school heads, educators, and students. P. Stockland, “Independence and Inequality.” Convivium, May 21, 2020. https://www.convivium.ca/articles/independence-and-inequality/; P. Stockland, “Recalibrating Education.” Convivium, May 25, 2020. https://www.convivium.ca/articles/recalibrating-education/; P. Stockland, “Upholding Community.” Convivium, May 27, 2020. https://www.convivium.ca/articles/upholding-community/; P. Stockland, “Beyond Academics.” Convivium, June 1, 2020. https://www.convivium.ca/articles/beyond-academics/.

Independent Christian schools, like all private schools in Ontario and the four Atlantic provinces but unlike those in Quebec and the four provinces to the west, receive no government funding for operations or capital. On average, 96.6 percent of revenue derives from tuition and fundraising. 3 3 Based on the 2018–19 “Cash Basis Tuition Listing” from Edvance Financial Services “Cost Per Pupil” calculations. Previous demographic research about the families that choose independent Christian schools shows that these are largely middle- or working-class families. Their incomes are similar to those of other taxpaying families who send their children to “free,” publicly funded schools. 4 4 D. Van Pelt, D. Hunt, and J. Wolfert, “Who Chooses Ontario Independent Schools and Why?” Cardus, September 9, 2019. https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/who-chooses-ontario-independent-schools-and-why/; A. MacLeod, S. Parvani, and J. Emes, “Comparing the Family Income of Students in Alberta’s Independent and Public Schools.” Fraser Institute, October 2017. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/comparing-the-family-income-of-students-in-albertas-independent-and-public-schools.pdf; J. Clemens, S. Parvani, and J. Emes, “Comparing the Family Income of Students in British Columbia’s Independent and Public Schools.” Fraser Institute, March 2017. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/comparing-family-income-of-students-in-BCs-independent-and-public-schools.pdf. In other words, wealth does not explain their reason for enrolling their children in independent Christian schools. 5 5 Although, for example, Ontario’s Education Act in subsection 1(1) and the “Private Schools and Home Education Regulation” under Prince Edward Island’s School Act refer to non-government schools as “private schools,” the term “private” should not invoke images of elite, university-prep schools but rather that the schools are owned and operated independent of local school districts or the respective ministry (Ontario) or department (PEI) of education, and that these schools operate without provincial government funding. Instead, recent research suggests that “parents who sent their children to non-religious independent schools chose their school because it is safe, instills confidence in students, and teaches students to think critically and independently. Families who chose a religious independent school, meanwhile, cite their school’s support for their values, teaching right from wrong, and reinforcement of their faith or religious beliefs” as top reasons for their choice. 6 6 Van Pelt, Hunt, and Wolfert, “Who Chooses Ontario Independent Schools and Why?”

Methodology

Design

This report is based on data gathered through an online survey. The survey was developed and piloted in May and June 2020 and was based on a survey designed and administered by the US-based Association of Christian Schools International in a separate study. 7 7 We are grateful to L.E. Swaner, C. Marshall Powell, and ACSI-USA for permitting us to use and adapt their survey instrument. We have also modelled our report on theirs, which discusses their findings for the schools in their association. L.E. Swaner and C. Marshall Powell, “Christian Schools and COVID-19: Responding Nimbly, Facing the Future.” Association of Christian Schools International, May 2020. https://www.acsi.org/docs/default-source/website-publishing/research/acsi-covid-19-survey-report-final.pdf?sfvrsn=b4b7bf3d_2.

Potential participants in the survey were the principals (or school heads) of the eighty-one schools affiliated with Edvance. Participants were given one week to complete the survey. Access was distributed by email on June 9, with a letter of explanation and invitation to participate. Three reminders were sent between June 11 and June 16. The survey was closed at midnight on June 16. The full survey can be found in appendix C.

Participation Rate

The survey had a response rate of 85 percent. Sixty-nine schools in Ontario and Prince Edward Island participated. Respondents identified themselves as principals (100 percent), with 6 percent also identifying as teachers.

School Size and Grade Levels

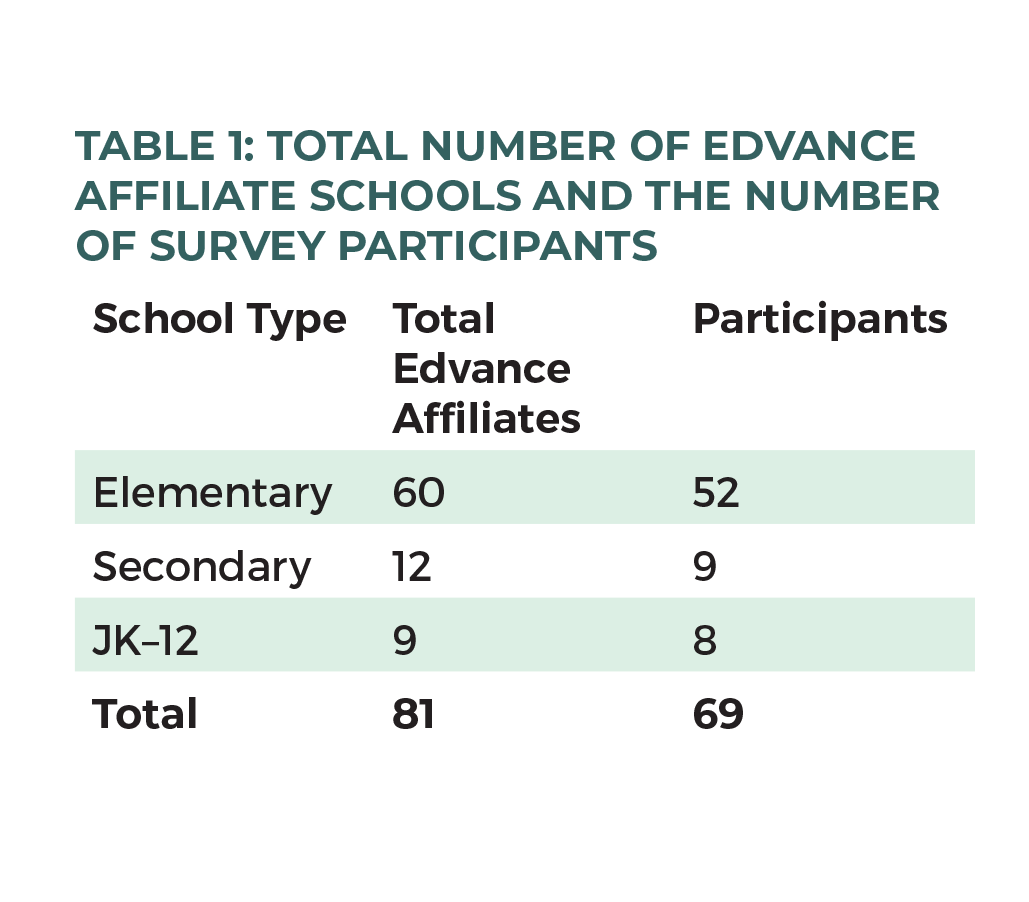

The participating schools were representative of Edvance affiliates in terms of grade levels offered and school size. Table 1 shows the actual number of participants in each school-level type and the total number of schools at each level. 8 8 Please note that although not specifically referenced throughout the report, appendix A provides tables with additional detail to accompany many of the tables and figures in this report. Methodological limitations are discussed in appendix B.

As shown in figure 1, 75 percent of participating schools were elementary (typically junior kindergarten [JK] to grade 8), 13 percent were secondary (typically grades 9 to 12), and 12 percent spanned elementary and secondary (typically JK to grade 12).

Findings

School Closures

Buildings and Campuses

At the time the survey was conducted, all physical campuses of the participating schools were closed. The school closure began on March 12 in Ontario and on March 17 in Prince Edward Island.

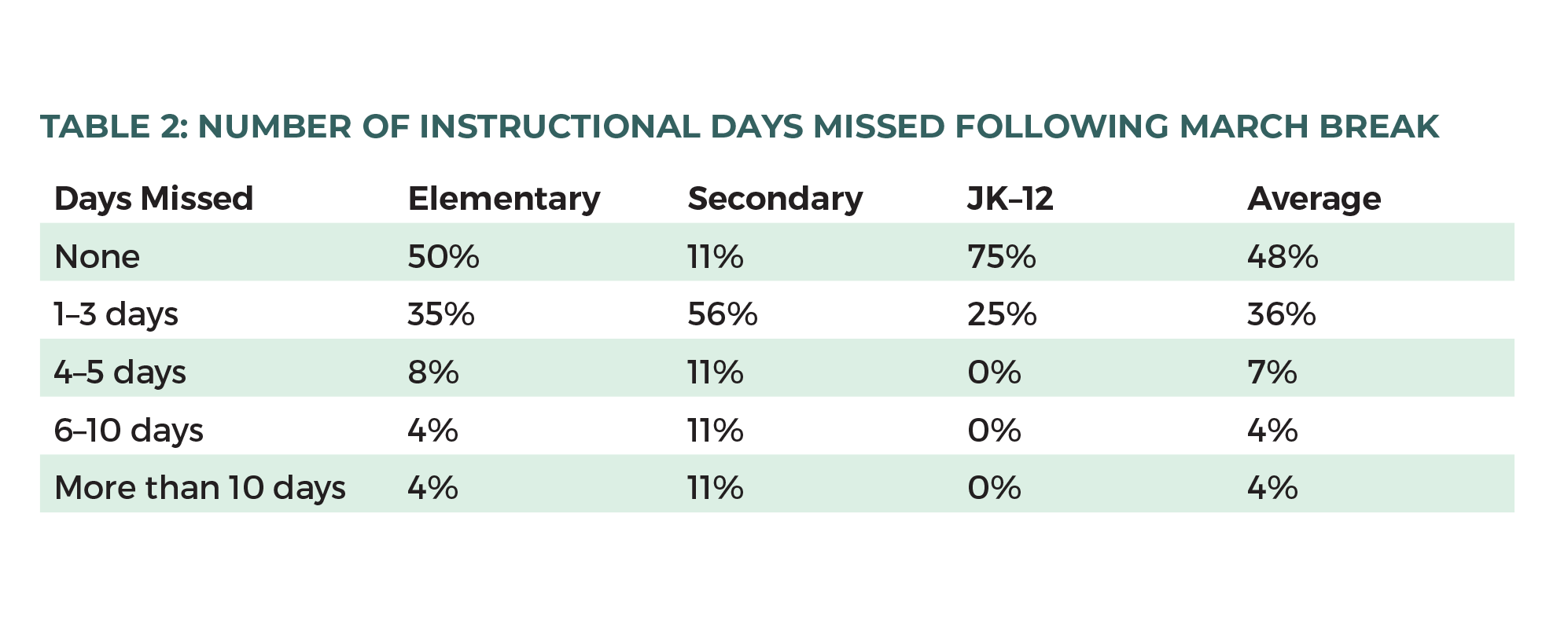

The survey asked about instructional days missed due to the physical closures, not including holidays, professional-development days, or planned breaks. A goal of this question was to gauge the timeline of the schools’ transition to remote learning. Across all levels, as shown in table 2, nearly half of all schools missed no instructional programming, 84 percent missed three days or fewer, and one of every twenty-five schools missed ten days or more. 9 9 One school that missed ten-plus instructional days discontinued remote learning early. It did, however, begin at least one parent-support group to encourage and assist parents to navigate the delivery of education for the rest of the year. The schools pivoted nimbly from face-to-face instruction to remote learning.

Remote Learning

Preparedness

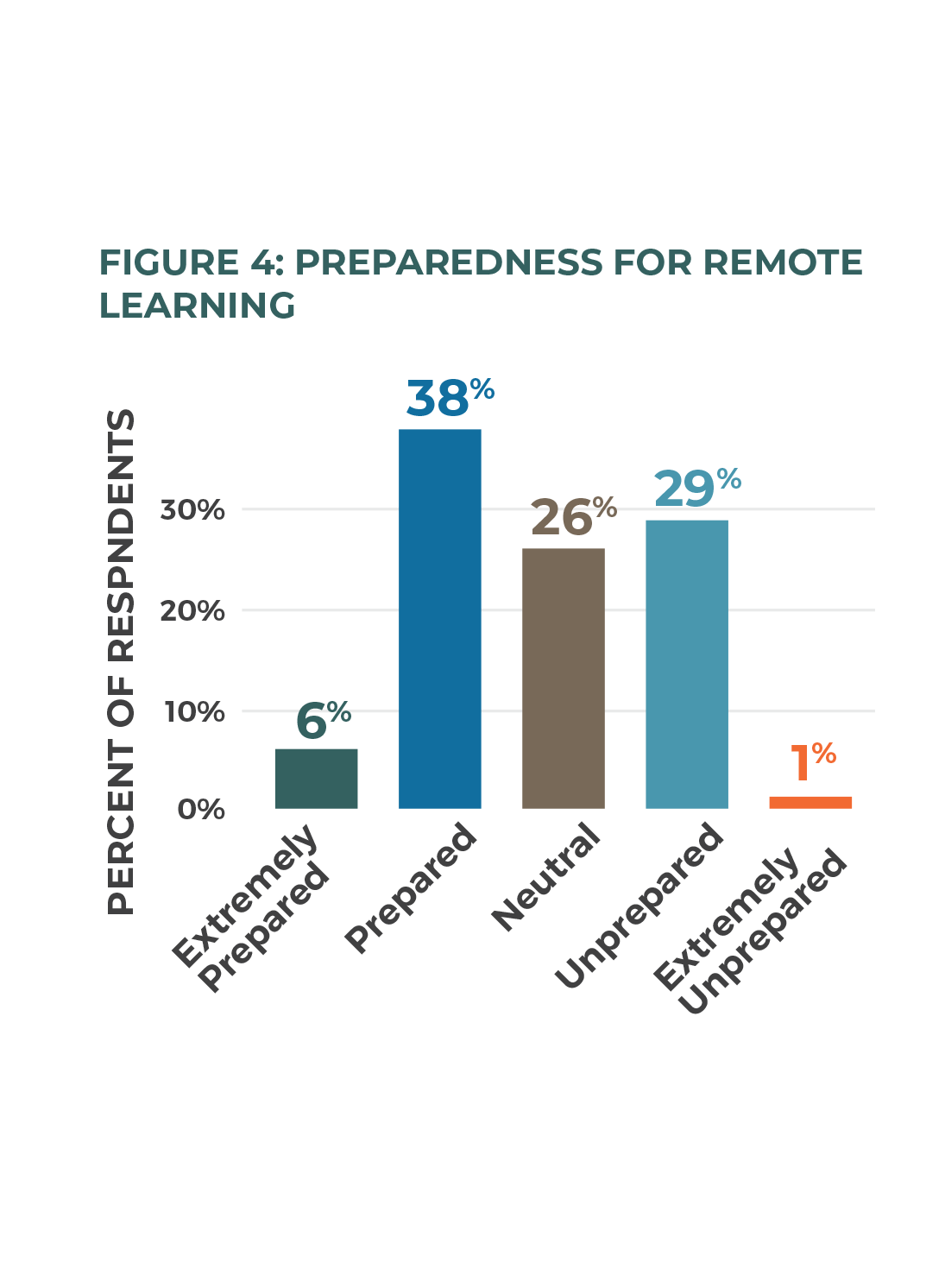

Participating schools were asked to gauge their prior readiness for offering remote learning. They were asked to self-assess their preparedness on a five-point scale from “extremely prepared” to “extremely unprepared.” Nearly half of all schools reported feeling either extremely prepared or prepared (44 percent), while 30 percent reported feeling unprepared or extremely unprepared. About one-quarter of participants reported a neutral answer (fig. 4).

When disaggregated by school type, JK–12 schools reported feeling most prepared for the transition, while secondary schools felt least prepared. Given the very few instructional days missed, as reported in table 2, it is surprising that more schools didn’t report feeling prepared for the transition, as most of them successfully did so in short order.

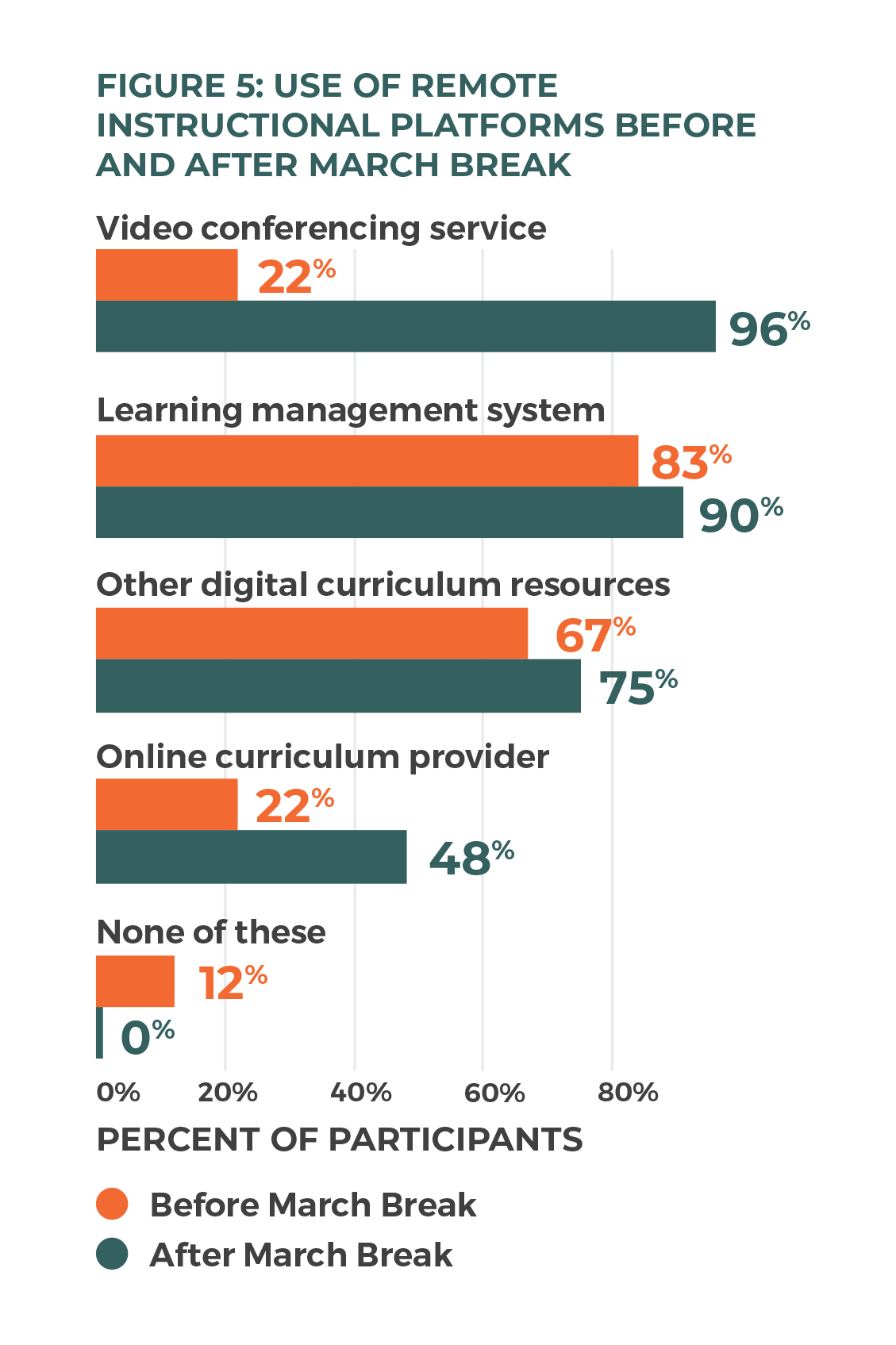

During the transition to remote learning, schools had to identify and implement technologies and tools to reach their learners in the new environment. In order to gauge their preparedness to do so, the survey asked participants to identify all of the remote-learning tools and platforms that were already in use before the buildings were closed. As shown in figure 5, learning-management systems such as Google Classroom and Edsby had already been in use by 83 percent of schools. Many schools (67 percent) reported using digital curriculum resources before the closure.

The use of remote-learning tools increased dramatically after the closures, with almost all schools reporting use of both a learning-management system and a video-conferencing service as part of their strategy (fig. 5). Use of an online curriculum provider more than doubled. Schools thus proved able to adopt and implement previously unused technology and tools to engage students in their learning activities and interactions.

“Our parents have been incredibly happy [during school closures] with the involvement of our teachers. Each class has a morning meeting on Zoom. Then the class has either French or PE in the afternoon on Zoom and closes off with a shorter meeting with homeroom teacher. We have chapel together as a school on Friday afternoon, with about 130 screens. The grade 7 and 8 teachers created a virtual tour and scavenger hunt of Montreal to help replace the graduation trip. Very creative!” —Oakville Christian School, Oakville

“Even though we would not have chosen to transition all of our learning online, both teachers and students have discovered blessings and benefits of this remote platform, which have stretched and challenged us to be more intentional, flexible, and resourceful. Our students and teachers were patient and gracious throughout this transition to a new delivery model. We value our community and relationships during this period of change and uncertainty.” —Redeemer Christian High School, Ottawa

Remote Learning Hours

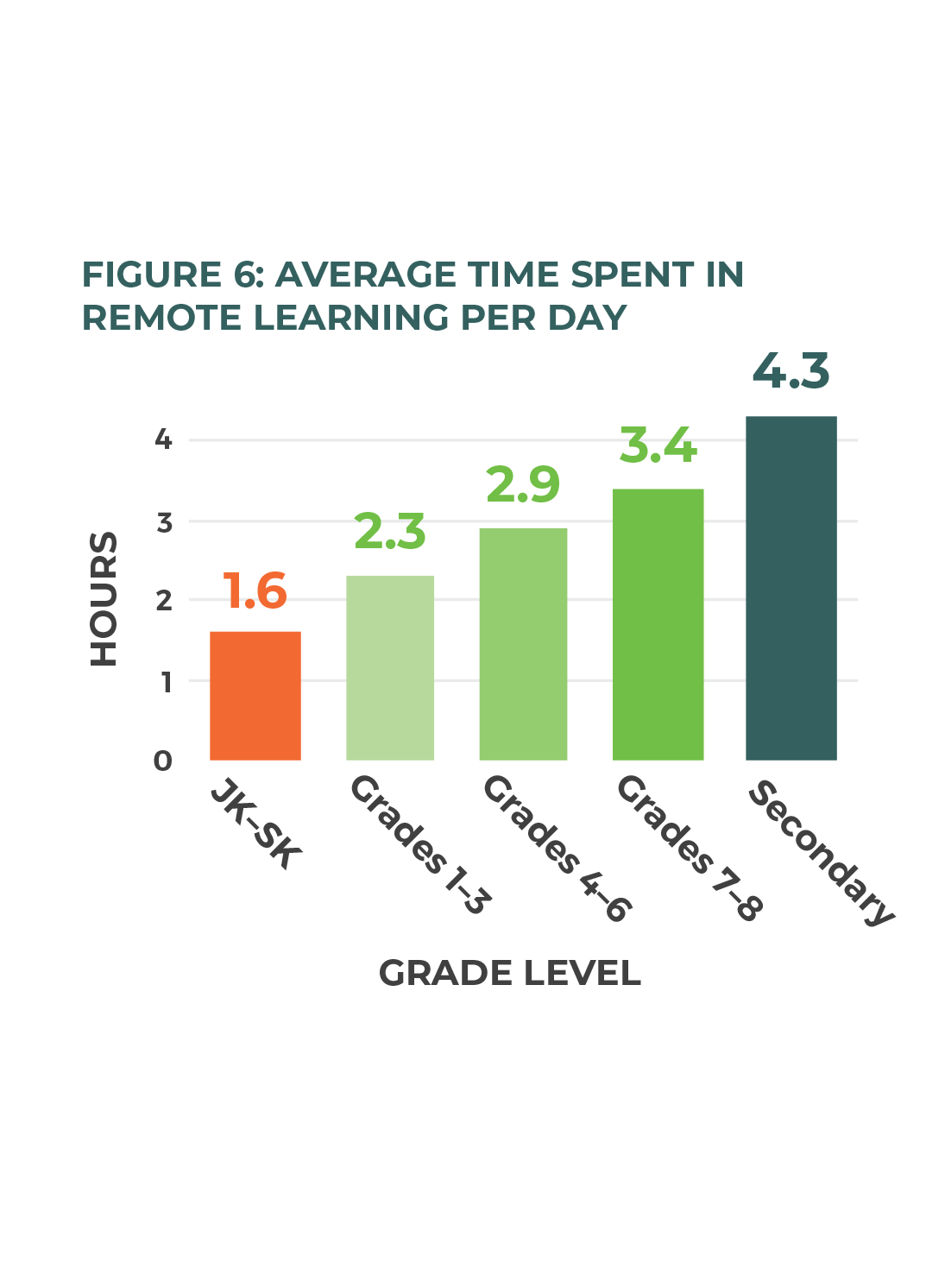

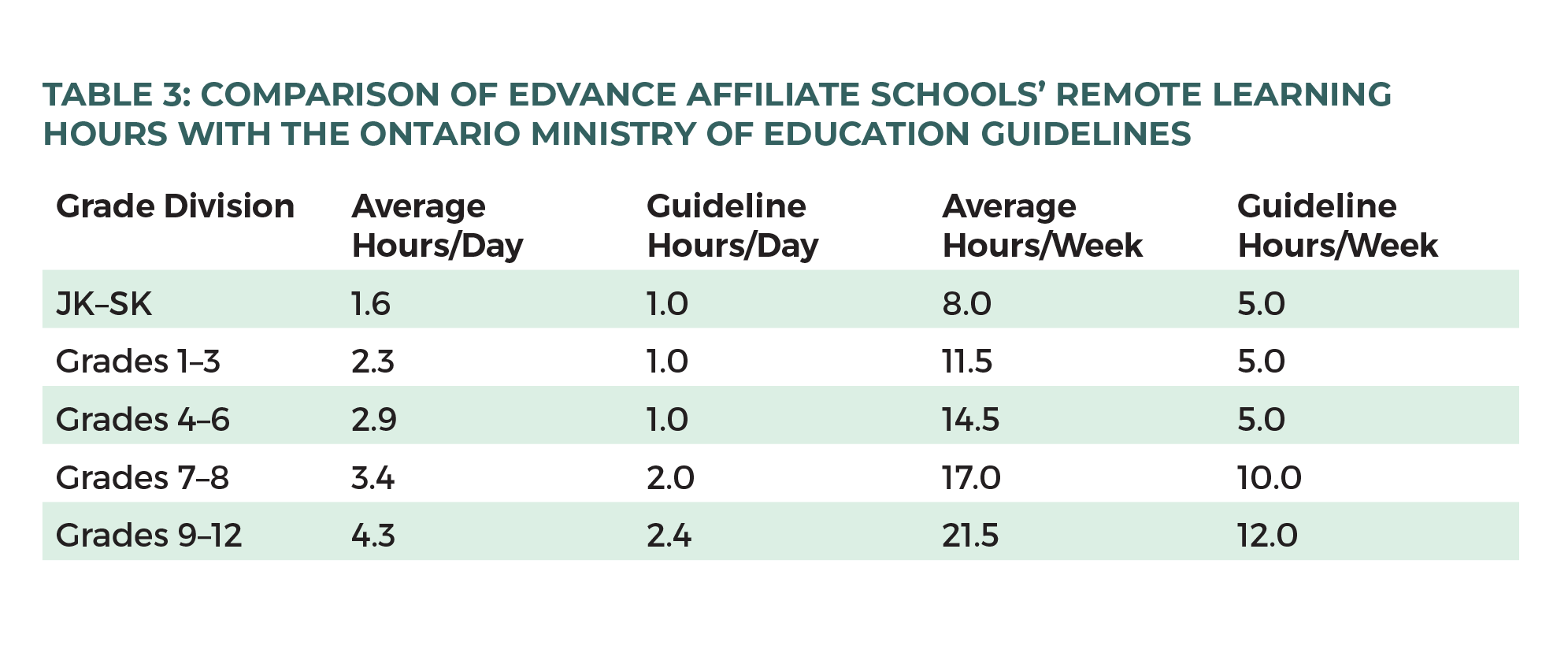

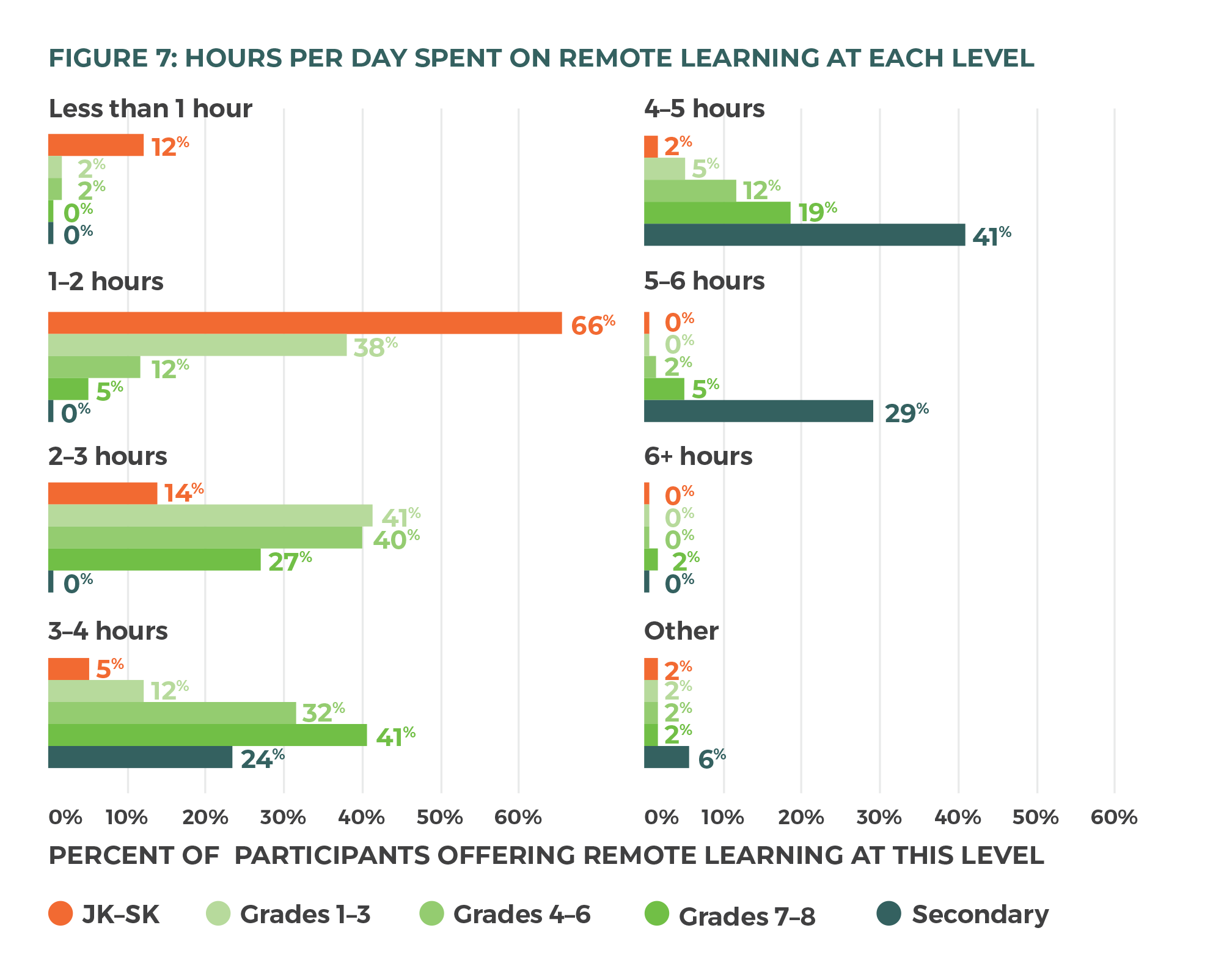

Schools transitioning from face-to-face instruction to remote learning had to determine how many hours of instruction were attainable in the new modality. Participants were asked to report how many hours of remote learning per day were provided to particular grade categories. Nearly all secondary schools reported between three and six hours of remote learning per day. There was much variation in elementary school reporting. Eighty-two percent of JK/SK students received one to three hours of remote learning per day (five to fifteen hours per week). Ninety-one percent of students in grades 1–3 received between one and four hours per day. Eighty-four percent of students in grades 4–6 received two to five hours per day. And 87 percent of students in grades 7–8 received two to five hours per day, with some schools reporting some level of variation from the given choices (fig. 6). The majority of the schools met and often exceeded the hours-per-week guidelines published by the Ontario Ministry of Education, as listed in table 3. 10 10 S. Lecce, “Letters to Ontario’s parents from the Minister of Education.” https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education.

The average hours of remote instruction, as shown in figure 7, rose steadily for each cohort of students from junior kindergarten to secondary school. This is an expected result, given the differences in children’s ages and their learning at various grade levels. A junior kindergarten student, for example, would be expected to spend much of their time engaged in play and socialization, whereas a grade 12 student would be more heavily engaged in individual academic activities.

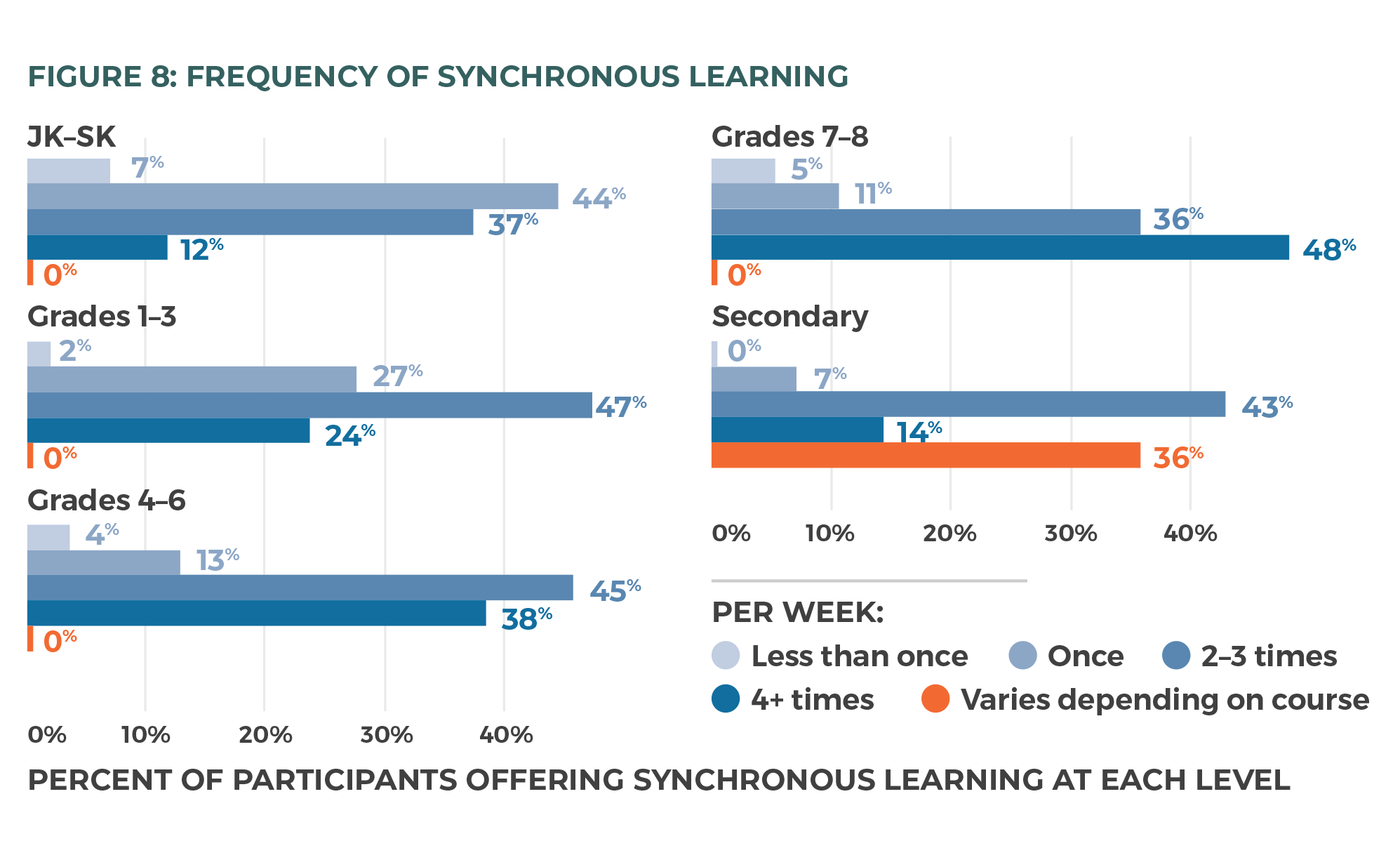

Involvement of teachers synchronously (that is, “live” or “in real time” with students) was a much-debated topic in remote learning. It was also a contentious issue politically in Ontario during this time. Very few of the surveyed schools, as illustrated in figure 8, reported less than one time per week engaged in real-time lessons, activities, and meetings with students. This suggests that schools felt that synchronous learning was an integral part of their connections with students. The frequency of synchronous learning varied by grade level, with the youngest students receiving less synchronous learning than senior students.

The exception here is the secondary schools, for which fewer synchronous hours than their counterparts in grades 4–8 were reported. It is possible that students working at the secondary-school level were able to work more independently than those in elementary school and thus require less real-time teacher interaction, as is the case in the face-to-face classroom.

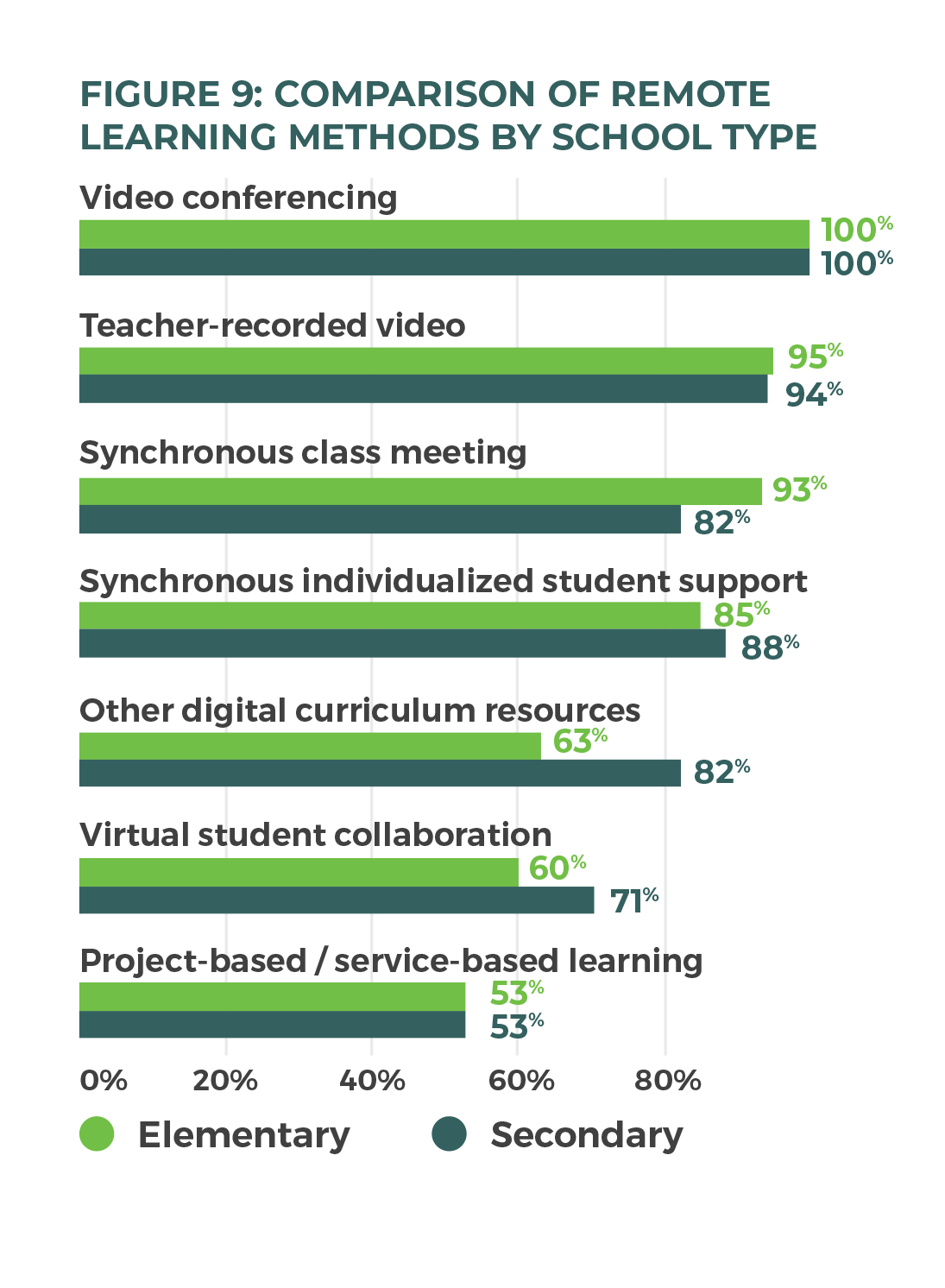

It is likely that teacher-recorded videos, synchronous class meetings, and synchronous individualized student support were methods that had been used sparingly before the March break. Yet many schools began using all of these tools to meet their students’ needs during remote learning. It is notable that fewer schools employed virtual means of student collaboration (fig. 9).

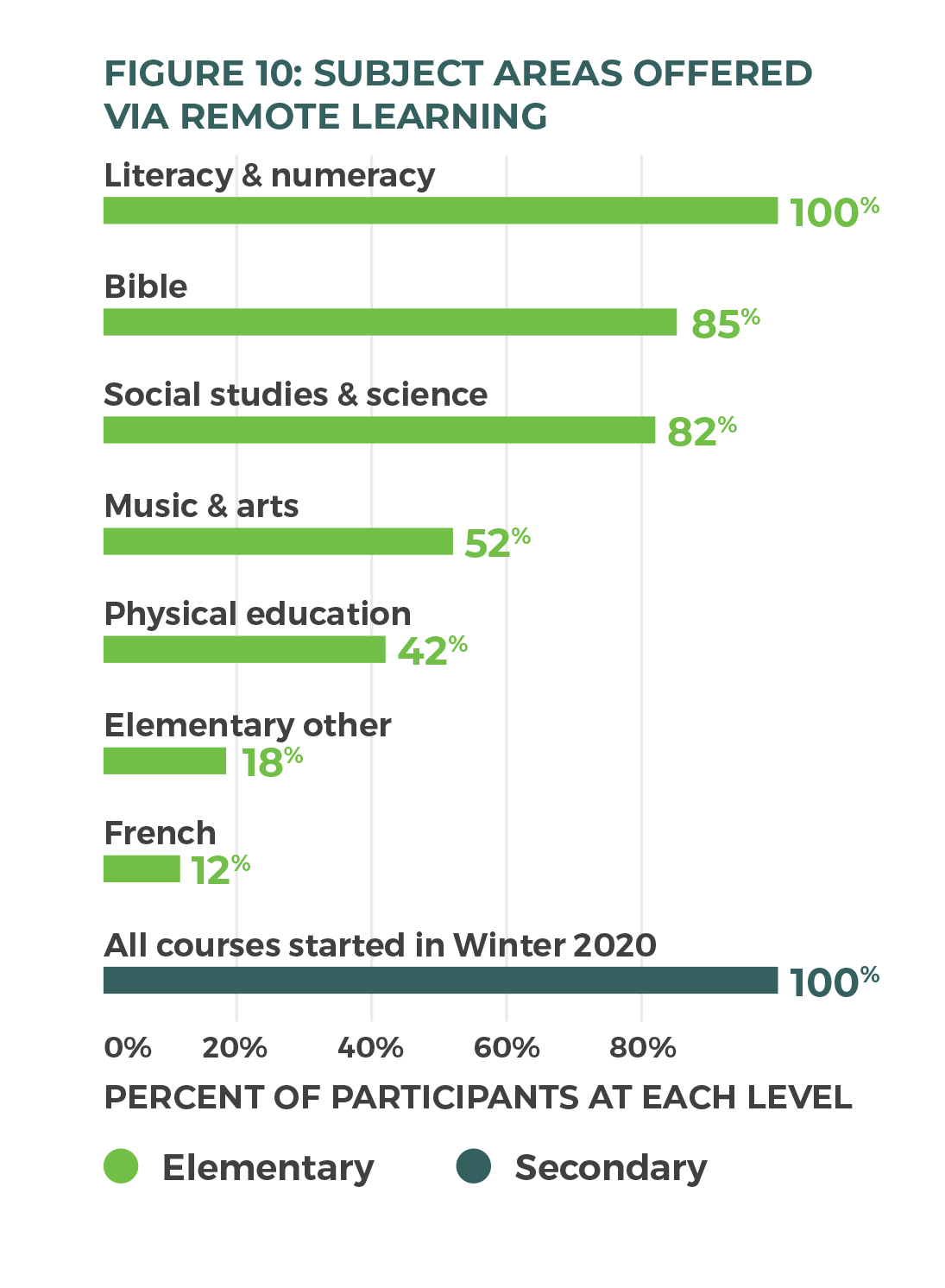

Subject Areas

All of the schools were able to transition to remote learning with their students in certain subject areas (fig. 10). All secondary schools reported continuing the courses that had begun in winter 2020. All elementary schools reported providing grade-level literacy and numeracy programming for their students. Over 80 percent of elementary schools were able to continue offering social studies, science, and Bible from a distance. One in two schools continued to offer music and arts, and two in five reported continuing physical-education classes.

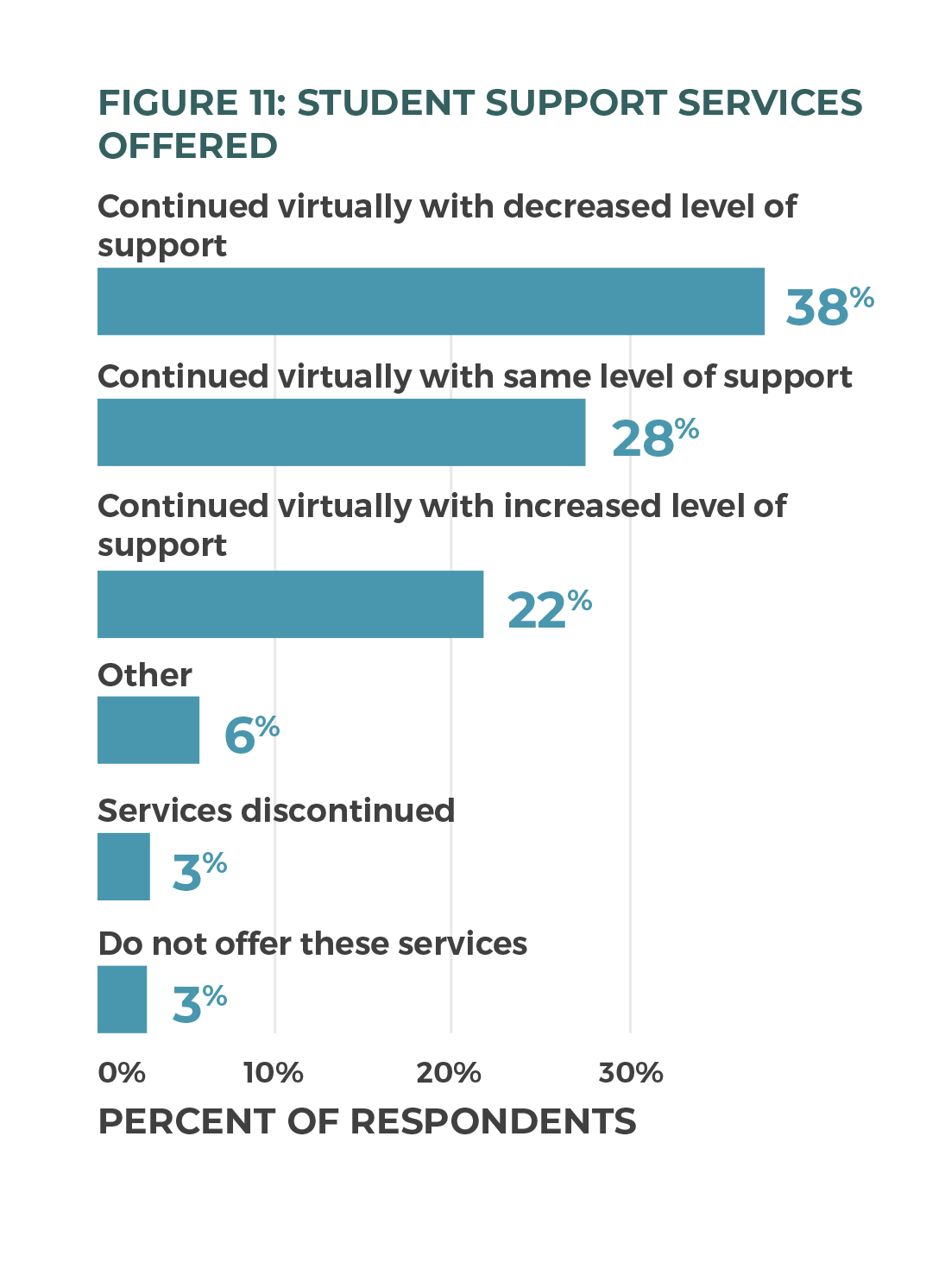

Special Education (Student-Support Services)

When asked to what extent special education (increasingly called student-support services) continued during remote learning, the schools’ responses indicate that they clearly prioritized, and often enhanced, this service. Of schools that offered special-education services (97 percent), most continued offering special education support services (88 percent) either fully, at the same level, or at a decreased level (fig. 11). Only 4 percent of schools reported that they had discontinued these services. Almost nine in ten secondary schools (89 percent) either increased their level of support or maintained their pre-remote level.

Community Connections

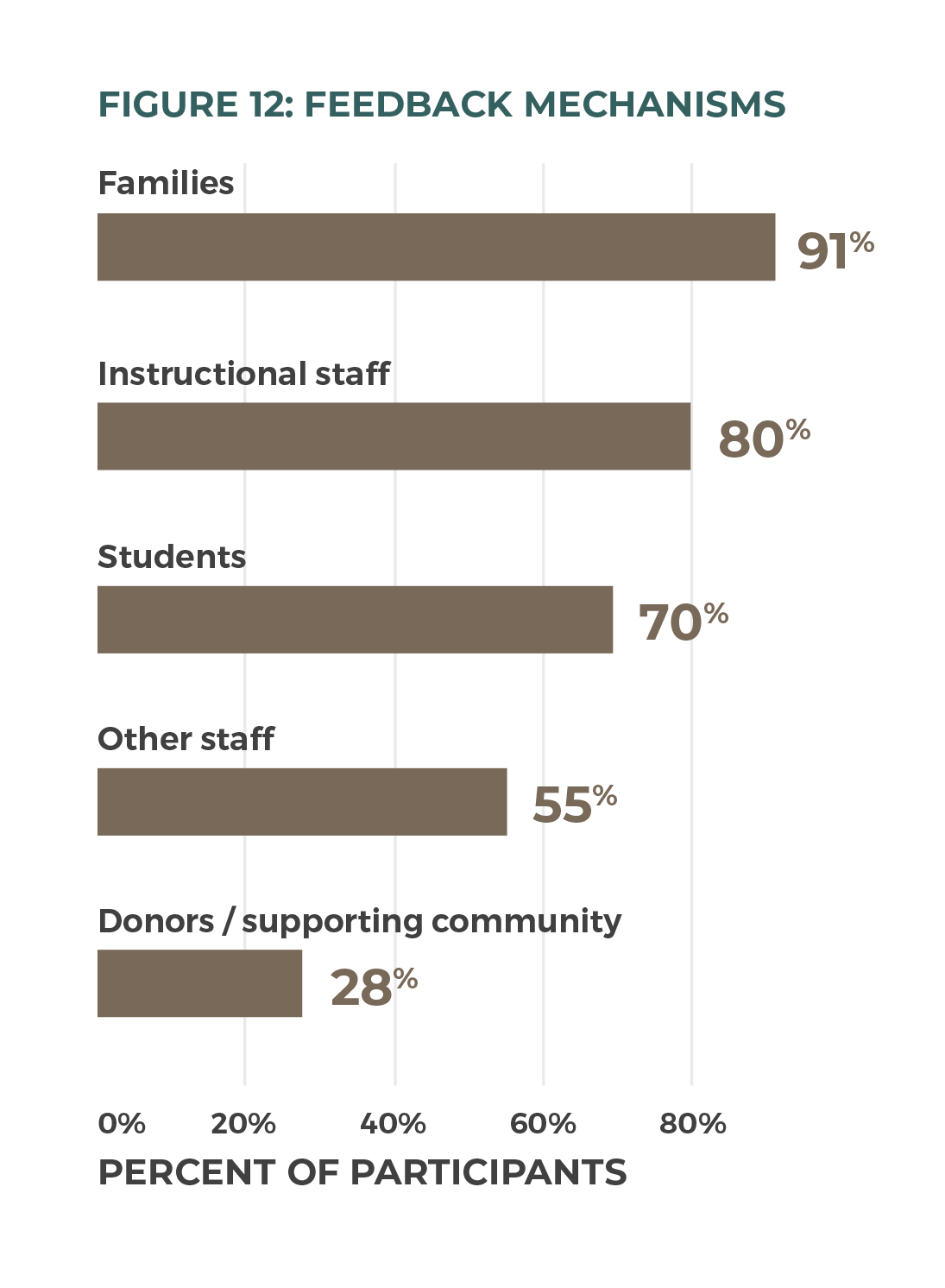

Feedback Mechanisms

As schools worked to find ways to connect with their families from a distance, participants were asked to disclose whether they had feedback mechanisms in place to collect non-anecdotal data from particular stakeholders. Nine in ten schools (fig. 12) created ways to connect with families, while eight in ten connected with instructional staff and seven in ten with students. Schools reported less contact with other staff, or with donors and the broader support community.

Types of schools differed slightly in how well they were able to connect with their various stakeholders. It appears that secondary schools and JK–12 schools were able to consistently find ways to solicit feedback from families, instructional staff, and students. All school types struggled with consistently finding ways to connect with other staff, and with donors and the broader support community. It is likely that “other staff” included staff who had been laid off and were therefore not part of regular communications.

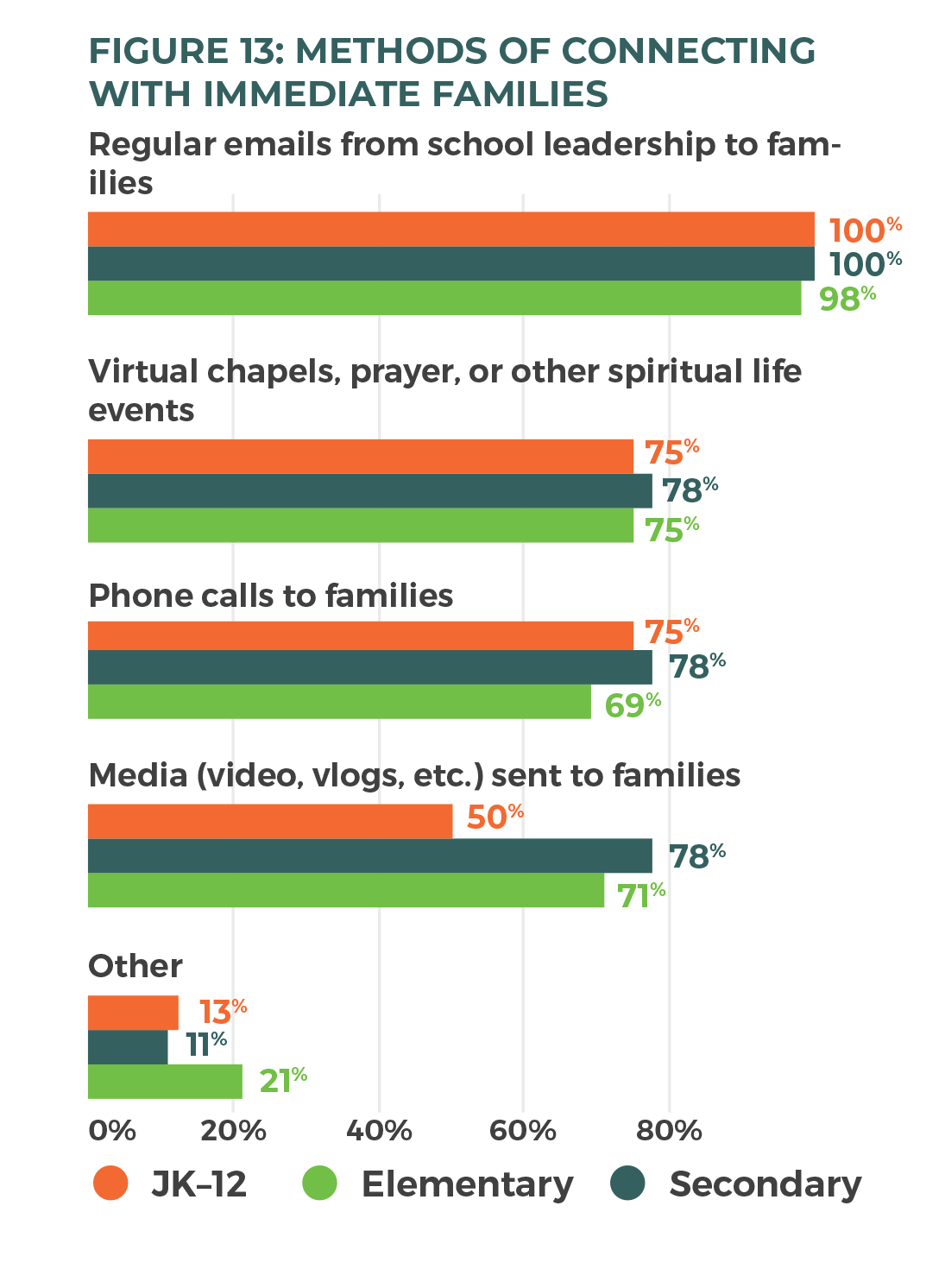

Connecting with Immediate Families

It is clear that all schools prioritized communications with their immediate families over other stakeholders. We asked participants to recount how they connected with their school families. Universally, schools employed regular emails from school leadership to families. It is unclear whether the following methods were employed before remote learning began, but over 70 percent of schools communicated with families by means of virtual chapels, phone calls, and media (video, vlogs, etc.) (fig. 13).

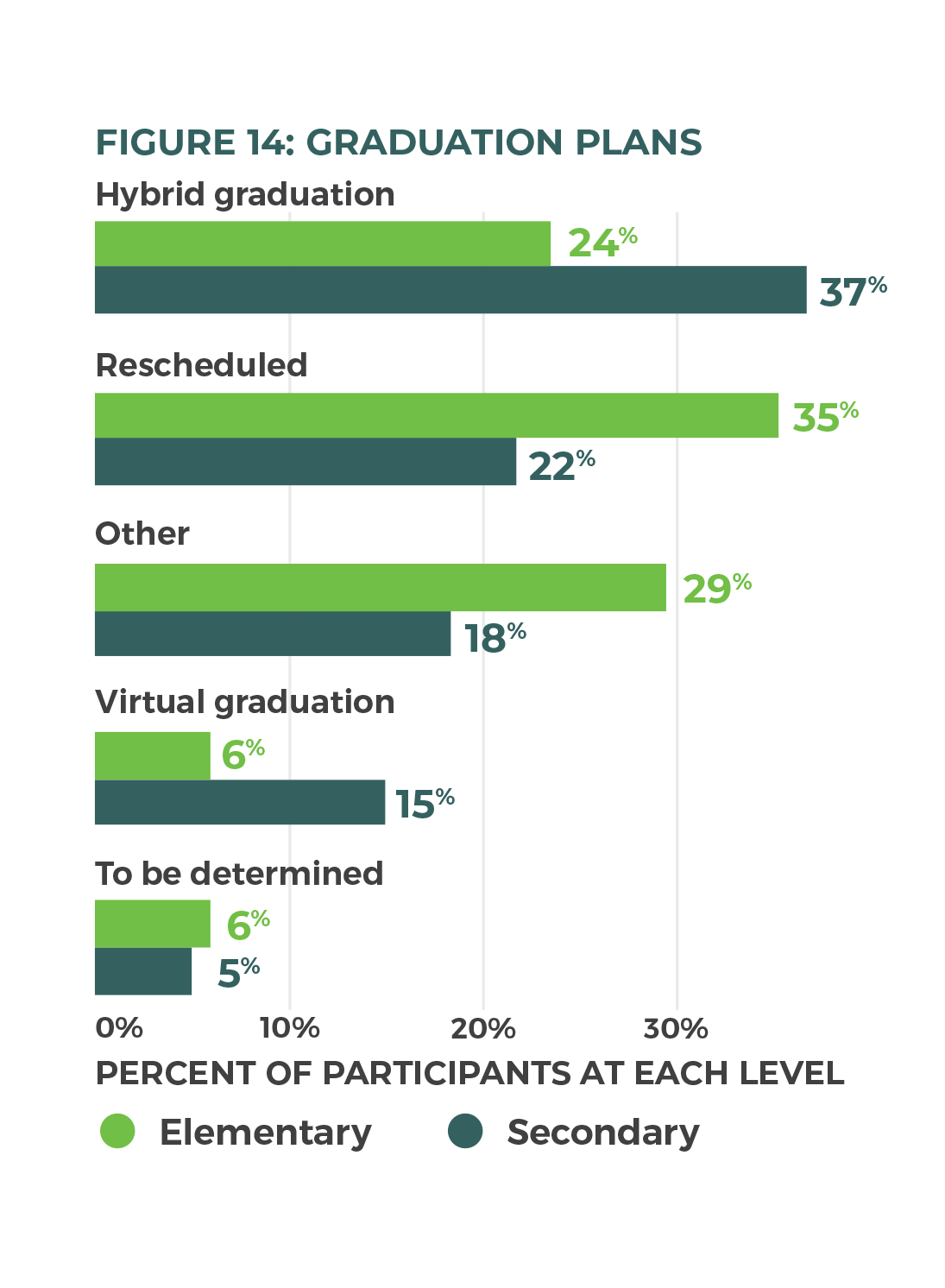

Graduation

Schools came up with new and innovative ways to host their graduation ceremonies for the class of 2020. Notably, none cancelled their festivities completely. There was some variation by school type. For example, 35 percent of secondary schools decided to reschedule their graduation to a later date, whereas over 50 percent of elementary schools decided either to proceed with graduation virtually or to create a hybrid graduation plan (fig. 14). In all, the schools creatively celebrated their graduates and maintained or enhanced community connections through this period.

Financial Impact

Tuition

Edvance affiliate schools depend largely on tuition fees to meet their operating expenses. Some families’ finances were negatively affected by the closure of businesses deemed non-essential. Many of the schools (eight in ten, as shown in fig. 15) responded by offering emergency tuition relief to families who needed assistance.

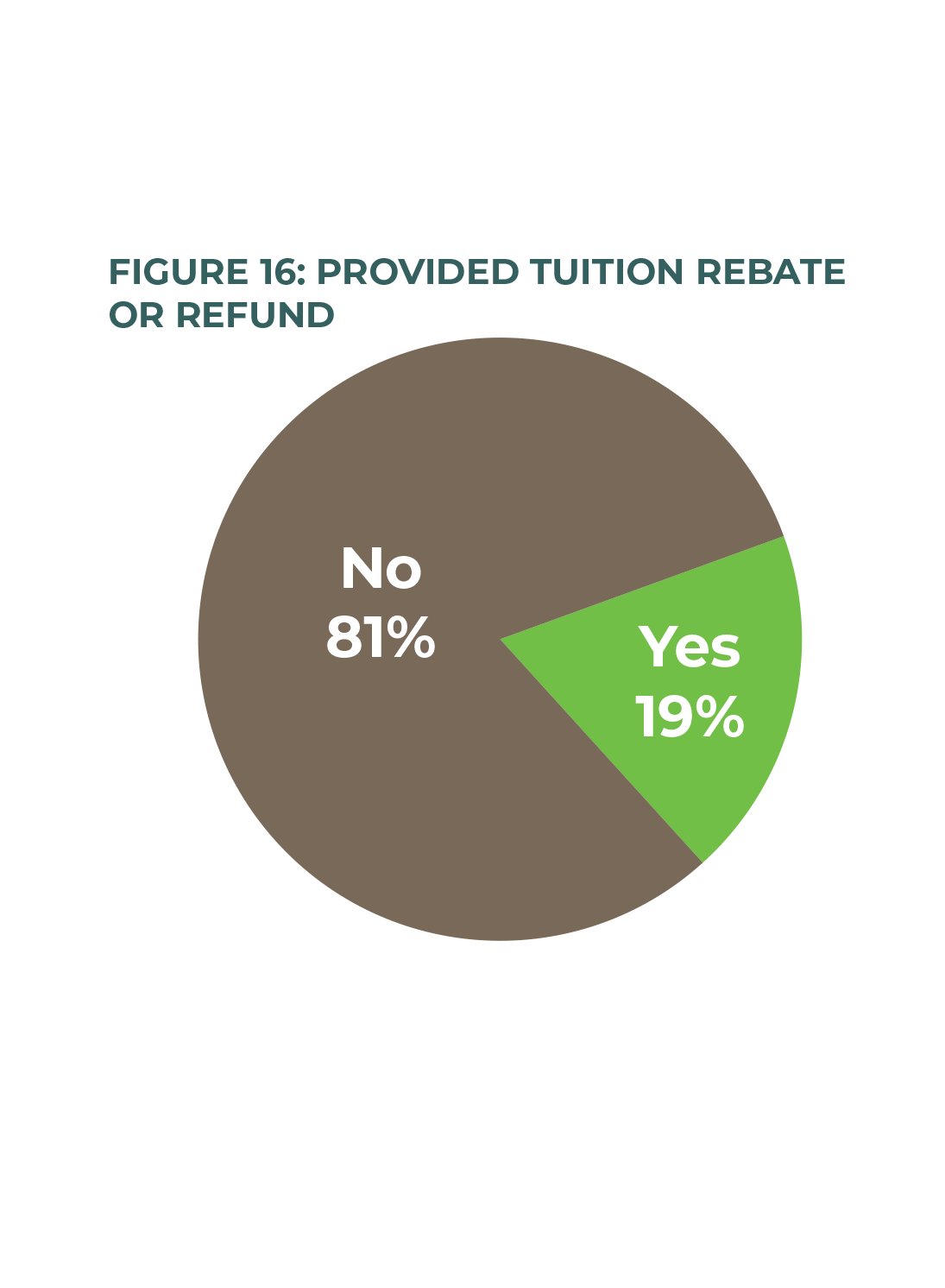

On average, each school offered tuition relief to eight families, with 457 total families benefiting. Some schools (19 percent, as shown in fig. 16) decided to provide tuition rebates or refunds. If rebates were given, they were typically small and included rebates of specific fees (extracurriculars, transportation, etc.).

Staffing

Schools were asked to report whether they had laid off any staff. As shown in figure 17, over three-quarters of schools (77 percent) reported laying off some staff. Forty-nine percent of schools that reported laying off staff said that they laid off 11–30 percent of their employees (fig. 18).

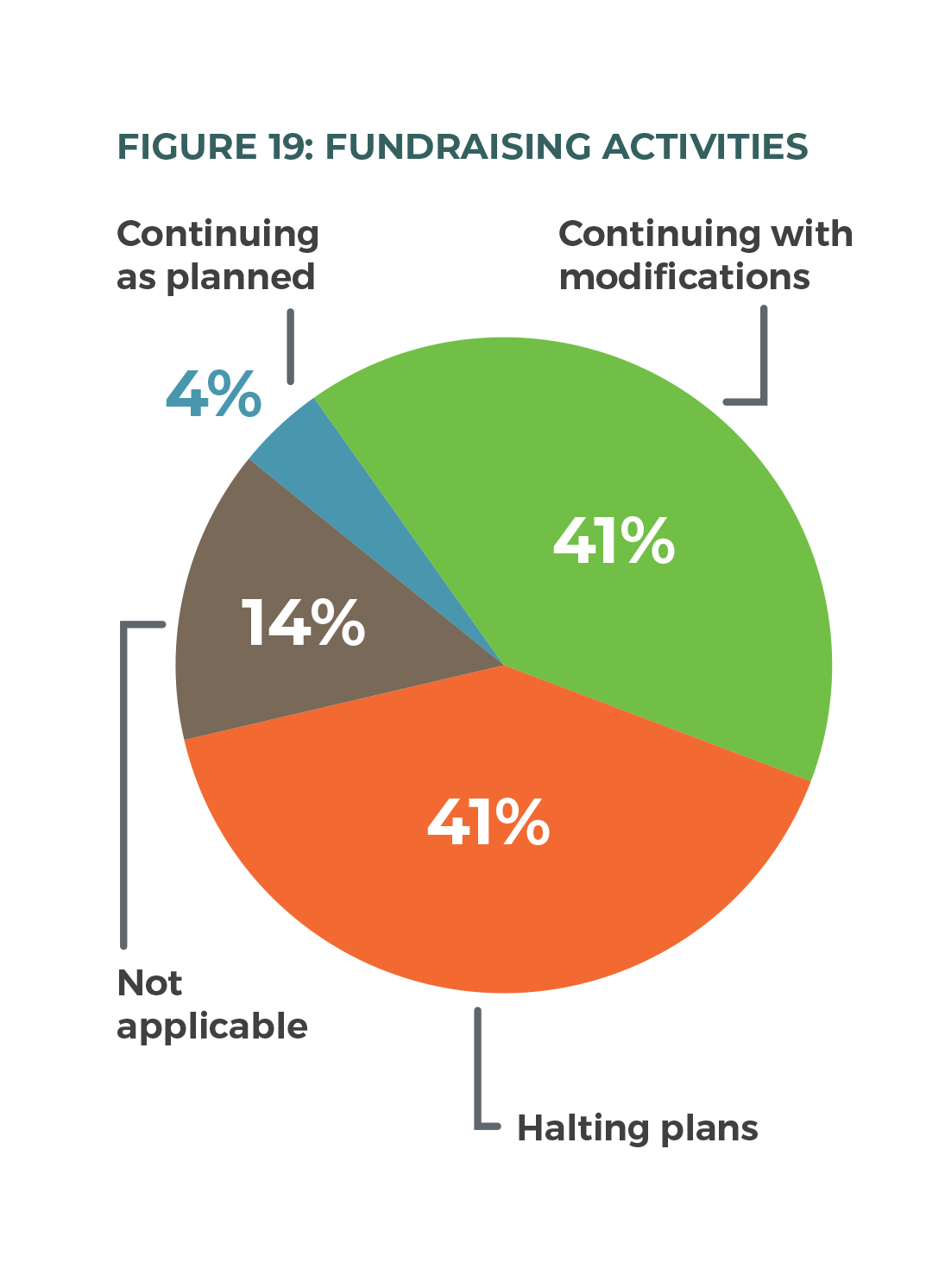

Fundraising

The school-building closures affected fundraising activities heavily. Participants were asked to describe how their school was intending to handle their planned fundraisers. Most schools (82 percent, as shown in fig. 19) either modified their planned fundraisers or completely halted fundraising efforts. Qualitative data, however, provides strong evidence that schools continued to experience the generosity of some donors, with occasional reports that donors gave in unexpected ways to tuition assistance and other needs during this time.

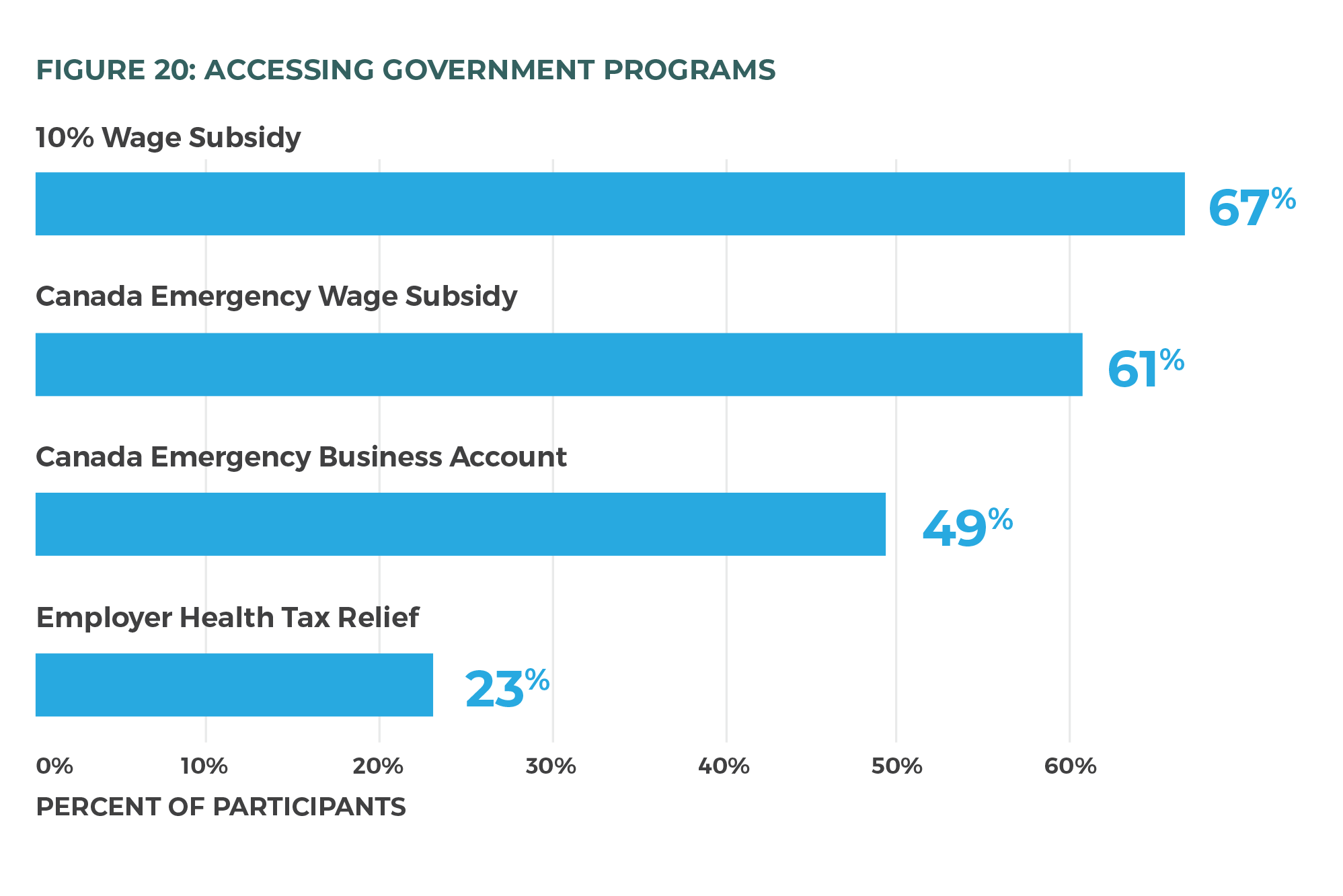

Accessing Government Programs

Many schools chose to participate in one or more government-assistance programs, including the 10 percent Wage Subsidy (67 percent), Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (61 percent), and Canada Emergency Business Account (49 percent) (fig. 20).

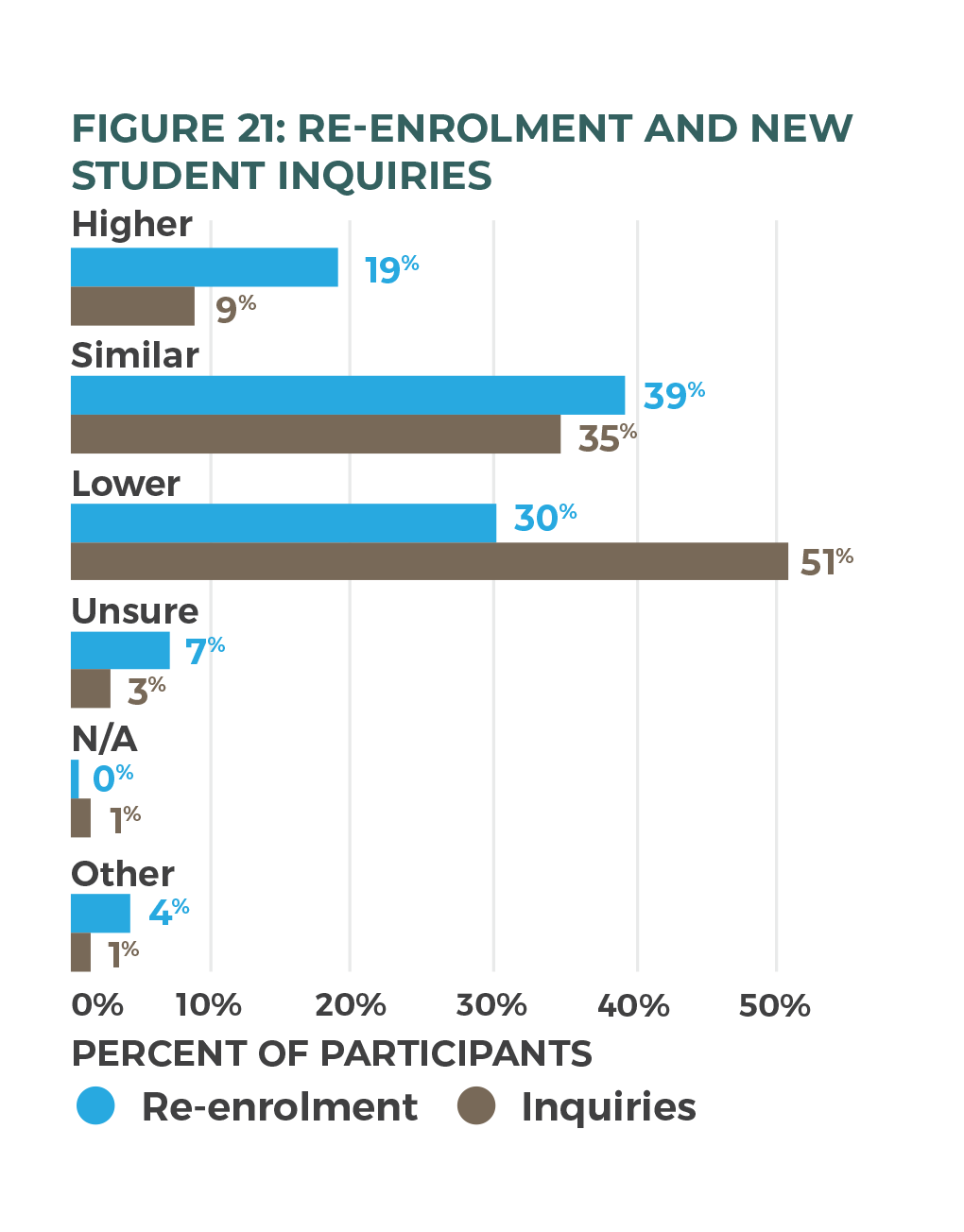

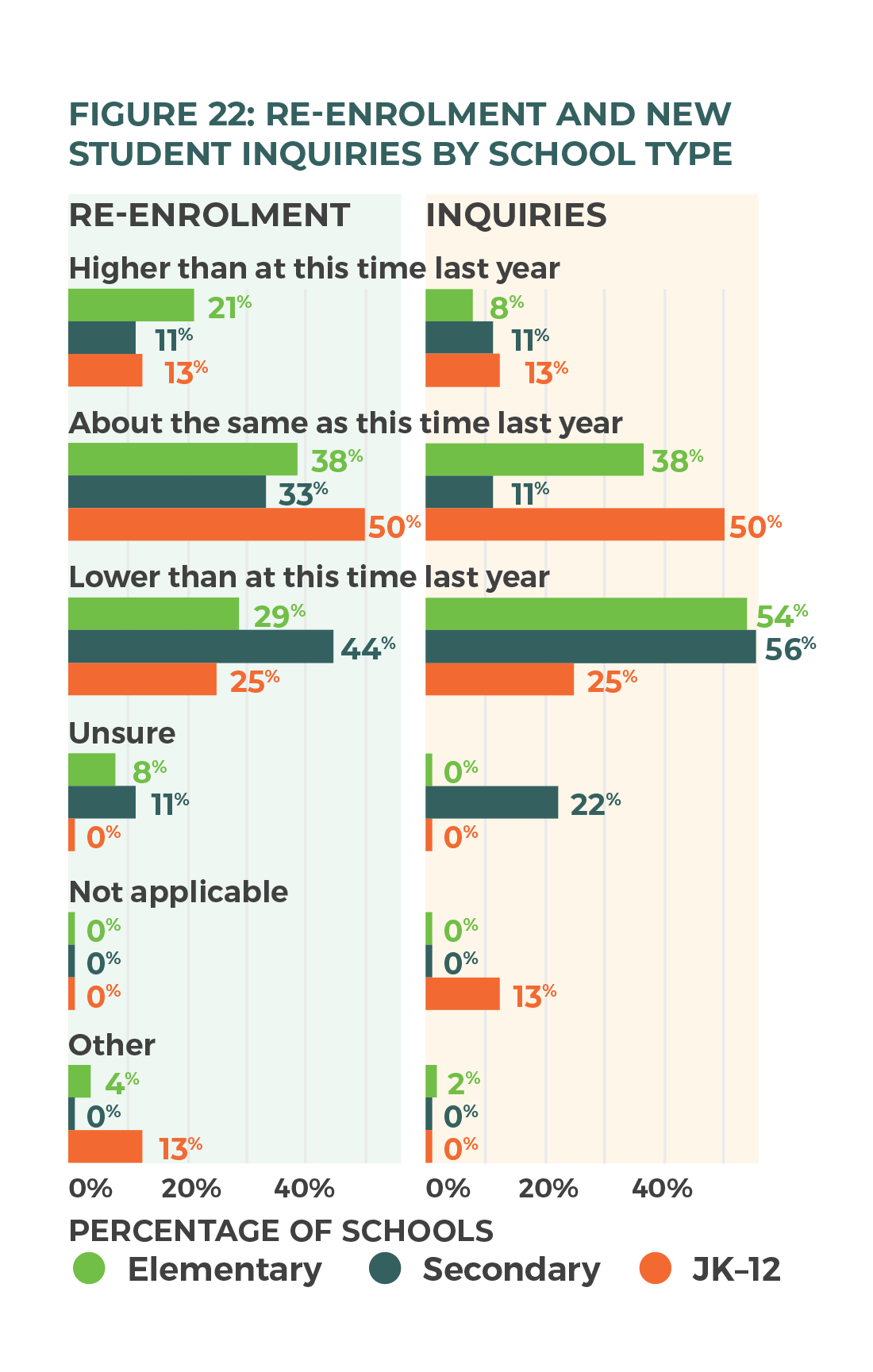

Looking Ahead to 2020–21

In addition to questions about the current year’s financial outlook, the survey asked participants to respond to questions about enrolment planning for the 2020–21 school year. Most participants (69 percent, as shown in fig. 21) reported that that their projections for re-enrolment (enrolled families returning) were either the same or lower than at the same time the previous year. A majority of schools (51 percent, as shown in fig. 21) reported lower new-student inquiries when compared to the same period in the previous year. Secondary schools reported the lowest number of re-enrolments and inquiries compared to the previous year (fig. 22). This may in part reflect the uncertainty surrounding international student enrolment.

When asked to predict their enrolment in the event of return to full-time face-to-face schooling in fall 2020, the respondents showed optimism. Most schools (58 percent, as shown in fig. 23) anticipated growth if face-to-face schooling resumed, whereas only 4 percent of schools projected growth if the new school year was not entirely face-to-face and would include remote or hybrid learning. Elementary-only schools reported that they expected an enrolment decrease if hybrid or entirely remote learning was in place in September. It is possible that school leaders anticipated that parents of very young children would be unwilling to enrol if they were faced with facilitating their child’s learning at home.

Some additional anecdotal responses suggest that respondents anticipated that enrolment would depend on the form schooling would take in September. Given the success that schools appear to have had with their remote-learning models and the good retention of students during this time, the level of pessimism toward enrolment for the next school year, should it not be entirely face-to-face delivery, is perhaps surprising. Still, success in short-term remote learning in an emergency context is different from sustaining the approach over the longer term.

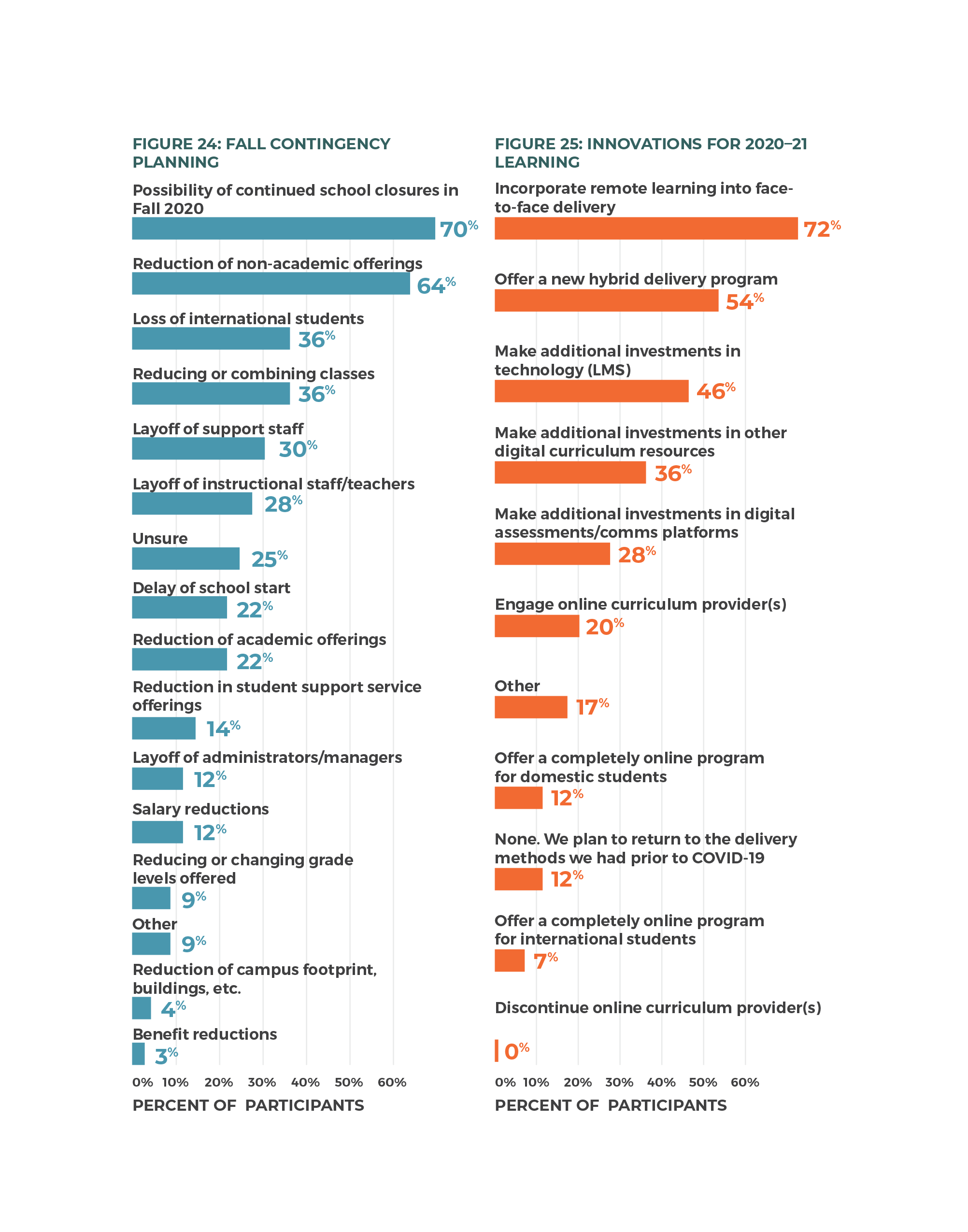

Contingency Planning

The pandemic disruption presented many difficulties for schools in terms of finances, operations, and instruction. Participants were asked to identify the contingency plans that they were considering for the next school year. Many schools reported that they expected continued school-building closures (70 percent) and a reduction of non-academic programs (64 percent, as shown in fig. 24).

Participants were also asked about innovations they were considering. Significantly, most schools (72 percent, as show in fig. 25) were planning to incorporate remote learning into their face-to-face delivery, while over half (54 percent) also indicated that their innovations in learning could include a “new hybrid delivery program.” Indeed, 46 percent indicated that they would make additional investments in technology. In identifying “other” innovations, participants listed innovations such as 1:1 devices, cohorting students, part-time rotation of students, multi-site learning, low-tech approaches, expansion of partnerships with other Christian schools, and using school spaces in unique ways.

The schools have proven their ability to be nimble and innovative. Overall, principals indicated that their planning for future programming would include at least some remote-delivery elements within a primarily face-to-face, in-person instructional model, with a slight majority indicating exploring new models of hybrid programming (not all of which, it should be pointed out, include digital technology). Taken together, this presumably points toward a future of rather different models for instructional delivery in Christian schools. Indeed, a propensity toward increasing instructional variation and pedagogical innovation positions these schools to grow and flourish in the new educational landscape that could emerge following the pandemic.

Stories

When invited to share a positive story about their school from this time, seventy-four participants provided responses of various lengths. Some have been quoted individually throughout this report, offering examples in the school leaders’ own voices. Reflection on the comments as a whole reveals at least three distinct themes: community collaboration, educator capacity, and student agency.

Community Collaboration

Principals overwhelmingly reported on the collaboration experienced during this period. In the words of one respondent, it was a time of “responsive engagement.” Parents, donors, volunteers, and boards were highlighted as critical to the schools’ well-being and even flourishing “during this challenging time,” in the words of one respondent.

Many reflected on parents. “We have a . . . close partnership with our parents, who are very supportive and engaged in their child’s education; this has allowed learning to continue almost untainted for especially our older students.” One respondent noted a “growing appreciation between parents and staff for the way in which we are dependent upon each other within our community.” Several mentioned parents and teachers “getting to know one another better,” “parents having greater appreciation for what teachers do,” and remarked that parent “gratitude is overwhelming.” The gratitude was reciprocal, as many principals expressed appreciation for the role that parents played throughout these days. Many noted that families were also reaching out to one another, even setting up support groups. Evidently, the parent satisfaction spilled over, causing one school leader to note that “parents were so appreciative and vocal about the level of instruction being offered their children [that] we are responding to [new] parents requesting admission for their children, solely due to reports of [our current] parents.” And in another’s words, “[Experiencing] the growth of community is a vital reason families want to return. They are proud of the commitment and [are] sharing it with others.”

Donors and volunteers also played unexpected roles in schools’ well-being. As noted earlier, although 82 percent of schools had to halt or alter usual fundraising activities, several principals reported that they received unsolicited donations from members of the school community and grandparents who perceived the “possibility of need.” Respondents also expressed appreciation for the increased role that boards played in navigating the challenges. The readiness of independent-school board members to support the school in time of crisis is a significant insight. Typically, local community members are elected or appointed to serve for a term on an independent-school board, and it is most common that the role is one more of governance than of operations. This study points to the seriousness with which board members approach their position and indicates their willingness to accept responsibility for increasing involvement (perhaps even at the operational level) during times of hardship and crisis in independent schools.

In all, the manner in which the school community journeyed together appears to be one of key strengths and benefits to families and students of independent Christian schools throughout the difficult circumstances in spring 2020.

Educator Capacity

At the nexus of the remote-learning journey were the educators. Principals reported many examples of the role that teachers played in the successful delivery of education during these first months of the pandemic. Teachers were critical to maintaining personal connection with each student. “The teachers have been excellent,” said one, “and stepped up to the plate, connecting with students and making impromptu deliveries and phone calls to encourage students and support the community.” “I think the teachers throughout Edvance [affiliate] schools are heroes,” claimed another. “They were the gatekeepers of our school culture and ensured that students’ spiritual, academic, and emotional needs were attended to. Their genuine and sacrificial care of our school community was such a blessing.” Another principal reported, “I am so impressed with the way my staff has gone above and beyond to connect ‘in person’ with each of their students. Staff have dropped little packages off on doorsteps, provided graduation attire and staged grad photos on student front lawns . . . made extensive videos presentations including all their students.”

In terms of the curriculum delivery or remote learning offered, many principals were lavish in their praise. “The staff have been amazing in the way they pivoted to remote learning,” one effused. Another said, “We have been delighted by the ability and willingness of teachers to adapt to the challenging circumstances of this spring.” Another stated, “While the circumstances are difficult, it has been amazing to see the staff respond and work with kids to continue learning. Staff have been open to new technology and pedagogy, new ways of thinking about assessment, and many of these things will carry forward into the regular class. My staff has always valued collaboration, but it has been inspiring to see them share ideas, offer support and encouragement, as well as share beautiful student work.” One reported, “One of our older intermediate teachers who was not very tech savvy is now leading the pack with ideas and ways to make the online learning exciting for the students.” Another wrote similarly about positive uptake of use of digital technology: “Staff members who had very little experience with technology have started to include technology in great ways. To see their development and excitement, to see them find out it’s not actually that hard, has been valuable.” Another expressed similar appreciation for “the way the teachers have stepped up and been willing to learn new formats in order to produce incredible lessons.”

Many talked about how weekly chapel, often mixed with daily (remote) meetings with students, were important parts of the learning program offered during this period. “We started into remote learning the very first day following the March break, with very little preparation available. Our teachers have done a fabulous job engaging with students on a daily basis and keeping positive learning going. A highlight for building community into the midst of isolation [has] been our weekly online chapels carrying on with worship and teaching in alignment with our theme from Philippians 2 of ‘Jesus Christ is Lord.’ We carried on with a mantra of ‘Separate but Together.’”

Numerous principals reflected on the engaging use of digital technology to deliver learning. Some planned virtual field trips (some even in place of planned end-of-year trips). One told of a virtual track-and-field day that teachers planned and delivered remotely. Another said, “We hosted school-wide read-alouds each afternoon, where various teachers read some of their favourite books. Our daily school gathering each morning gave opportunity to go deep in teaching biblical truths in powerful ways. . . . We were enriched by weekly talent shows . . . hosted on Friday [afternoons] as a way to start our weekends with some fun. It was delightful, the ‘acts’ that auditioned for a spot in the show. We never would have hosted these events had we been in regular school. Some very special memories were made.” One school “challenged families to recreate famous pieces of artwork” and reported delight at the creativity and effort that their school Facebook page now displays.

Some designed virtual group meetings and chats so well that one young student claimed “he was enjoying the Zoom classroom chats so much that he hoped they would continue every Saturday once we returned to the classroom.” Moving to remote platforms has “stretched and challenged us to be more intentional, flexible, and resourceful,” stated another.

In addition to art, geography, physical education, read-alouds, Bible, and chapel, learning in core math and literacy also continued. Several fascinating stories were shared about unexpected student success. We share one story here: “A beautiful by-product of remote learning was the opportunity (with the blessing of parents) to expand a multi-grade Resource Spelling Class from two periods per week to the equivalent of four periods [per week] during remote learning. Students really enjoyed the classes, laughed often, and felt very successful in their learning. To our collective delight, the year-end diagnostic evaluation revealed that most students gained between two and four grade levels of spelling ability in this one school year!”

Creative, timely, effective, and caring design and delivery of learning, using new media and platforms, characterize the impressive contribution of these Christian school educators during this challenging time.

Student Agency

And at the heart of it stands the learner. If the stories told and comments offered by school heads in this survey provide a small window into the well-being and even flourishing that occurred during the pandemic’s early months, then perhaps we are all being given a glimpse of what is possible with students and student learning in the months and years ahead.

Repeatedly, the stories highlighted unexpected places and moments of flourishing. We were told of students who struggled in the ordinary classroom, now shining. We were told of students’ improvements in some subject areas due to more time, fewer distractions, and personalized and adaptive instruction. Most important perhaps, we caught an impression of what is possible when students experience increased ownership and responsibility for their learning, or, as it has been described, “when students take an active role in their education rather than having school ‘done to them.’”

These stories give us sightings of what took place when students found more agency in their learning during these days. It did not happen in a vacuum, but it did happen. An atmosphere and a vision were created by community, parents, and educators, supports were offered, and ultimately many more learners experienced real ownership of their learning and of their educational experiences.

“We were all caught off guard,” one principal said. “We all floundered at the start. But with perseverance and God helping us, most survived and many even thrived. Google Classroom was more manageable for the students in the grade 7 and 8 class than [for] the very young. Those who were already developing strong self-regulation skills were able to grab hold of this new learning and run confidently. Those who were still at the starting gate quickly realized they had to grab onto what was hitherto not their own. Many did, and they grew by leaps and bounds. One student in particular flourished and rose to the top. In the brick-and-mortar classroom, her perseverance skills were strong, but it was all just so hard. Classmates were distracting, the pace was too fast, and there were always the comparisons. COVID-19 burst in, and school shut down. This student was now free to spend as much time as she chose on her Google Classroom assignments, and this she did. Home-based learning, though abbreviated in scope, quickly became the opportunity to pore over her schooling for seven hours a day. Gone were the unsettling factors of the physical classroom. Welcome were the quiet and all the time wanted. In twelve short weeks, this student rose from a struggling student in the classroom to a robust and capable graduating grade 8 student. In many ways, we thank you, Lord, for school shutdown. You provided some unexpected triumphs!”

Another story of student initiative was as follows: “This good-news story involves a grade 8 student who was a competitive CrossFit athlete who had to give up the sport due to injury. He started making two workout videos a week that were shared with the students from grade 5 to 8 via YouTube. It was great to see him overcome his disappointment and share his passion with his fellow students.” Another story runs, “A student in grade 7/8 math had been struggling with math. They were quite shy and quiet, not the kind of student to ask for help. When asked if they needed help, they usually said they were doing fine. During the COVID-19 time at home, this student was able to spend time with their mom to work through the lessons. On occasion, they even joined in a Zoom meeting for ‘math help.’ I was afraid at times the student would become very frustrated and want to give up on math, as the content was getting quite difficult. This student not only continued diligently working each day, often several hours, but became more comfortable with the content and was able to successfully complete their work. The student has expressed an increased appreciation for math and in their abilities as a math student. Praise the Lord who was able to use this time for a renewed interest and commitment to the students’ work and for their parents’ input and assistance!”

Other encouraging stories of student initiative and agency have to do with finding ways to help others. Not only did some external donors offer support to several school, but the stories tell of a number of students in different schools becoming donors themselves, making donations of funds they had raised for now-cancelled field trips and other events. Respondents told of student groups giving their group funds to seniors’ homes, women’s and children’s shelters, and food banks.

When students own their own education, the learning becomes vibrant and real. The teacher genuinely becomes a respected guide alongside the student, who takes ownership and initiative over the approach to learning, including pacing, location, approach, and sometime content. Remote learning provided just such opportunities for many students to experience guided self-regulation and thus enhanced their own educational agency.

Conclusions and Discussion

We draw several conclusions from our analysis of the survey responses.

Successful Pivot Through Committed Educators

The schools affiliated with Edvance demonstrated resiliency and agility in the short term, showing an ability to adapt to new requirements and circumstances all while continuing to offer an engaging and effective program of learning. The transition to remote learning was quick, even though many felt unprepared. It is useful to note that, by way of contrast, that as late as August 19, 2020, the chair of the Toronto District School Board stated that “we just do not have enough resources to provide [remote learning] on an individual school basis.” 11 11 CBC News, “TDSB Wants to Centralize Remote Learning in a ‘Virtual School’ as Part of COVID-19 Plan.” August 19, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/Canada/Toronto/tdsb-remote-learning-virtual-school-1.5691770.” Not only did the surveyed independent schools adopt new technology quickly, they also engaged a wide variety of platforms in doing so. Indeed, within a single week, all schools, up from one school in five prior to the building closures, were using video conferencing to connect with students. As another point of contrast, publicly funded schools went entirely without teacher-led instruction from March 12 to April 6. On April 28 Ontario minister of education Stephen Lecce announced that work was now being assigned to students. 12 12 S. Lecce, “Letters to Ontario’s Parents,” March 24, 2020. https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education#section-9; S. Lecce, “Letters to Ontario’s Parents,” March 31, 2020. https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education#section-8; S. Lecce, “Letters to Ontario’s Parents,” April 28, 2020. https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education#section-7. But as these schools remained closed until the fall, 13 13 Office of the Premier, “Health and Safety Top Priority as Schools Remain Closed.” Government of Ontario, May 19, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2020/5/health-and-safety-top-proiority-as-schools-remain-closed.html. and no tests or grades were administered, it is reasonable to conclude that limited instruction, and most likely little formal education, took place in publicly funded schools from March 12 through to September.

Student Learning

The average number of hours that students spent in learning each day (as defined by school expectations) was significantly higher than the number expected by the Ontario Ministry of Education for publicly funded schools. 14 14 See S. Lecce, “Letters to Ontario’s Parents,” April 28, 2020. The “minimum suggested standard” was five hours for K–6, ten hours for grades 7–8, and three hours per course for semestered students, or 1.5 hours for non-semestered students, for grades 9–12. These higher hours were decided at the individual-school level, giving continued evidence of the presence of self-regulation and pursuit of high standards within the sector. Not only were learning hours per day higher, but synchronous learning was also frequently used as a key means of connecting with students—a measure that families and students appreciated. Synchronous learning, sometimes several times per day, contributed to academic success but also to students’ social, emotional, and spiritual well-being. Concern for the whole child remained evident even when physical presence was not possible.

Rounded Curriculum

While the Ontario Ministry of Education emphasized literacy and numeracy, our surveyed schools focused on those core subjects as well as on social studies, science, and Bible. Over half also included art and music, and two in five physical education. Christian education values the whole person, and offering a well-rounded curriculum is one demonstration of that priority. It was evident that this priority continued to be pursued and, in many cases, achieved. Celebrations of learning continued as well, and most schools found creative ways to celebrate their graduates—kindergarten, grade 8, and grade 12—while still respecting physical-distancing requirements.

Special Education

Almost all (97 percent) of participating Christian schools offer special-education services, with only 4 percent discontinuing these student-support services after mid-March. In fact, more than half of the secondary schools (56 percent) increased their level of student support. Not only was the whole student a priority; serving all students regardless of circumstances was evidently a priority as well.

Community Connections

Communication with families, parents, and students was a priority during this period. Communication was not one-directional, with the simple goal of keeping parents and students informed, but rather was designed to foster and enhance relations.

Communication with donors and the support community was a lower priority during this period.

Financial Resourcefulness

This group of schools appeared to be financially resilient in the short-term and also demonstrated a posture of generosity. More than four in five schools offered tuition assistance if requested, to an average of eight families per school. 15 15 Edvance affiliate schools serve an average of 98.5 families, thus an average of just over 8 percent requested financial assistance in this short-term period. About one in five schools also offered some refunds for extra fees and transportation. The short-term resiliency was apparent, given that four of every five schools had to alter or discontinue their usual fundraising in spring 2020. About three-quarters of schools laid off some staff, with 30 percent of schools laying off 31–50 percent.

It is remarkable that with diminished revenues and smaller staffs, the schools were still able to effectively deliver education that was widely appreciated. We point again to the significant contrast here with district school boards. Despite receiving additional resources to support remote learning in spring 2020, even as late as August, school districts stated that they lacked the resources to provide remote learning on an individual-school basis. 16 16 S. Lecce, “Letters to Ontario Parents”; CBC News, “TDSB Wants to Centralize Remote Learning.”

Short-Term Resiliency and Longer-Term Concern

When asked to look ahead, principals were less optimistic than when reflecting on the past. Almost three in five expected enrolment growth, even dramatic growth—but only if schooling returned to face-to-face delivery for the 2020–21 year. By contrast, only 4 percent expected growth if learning continued remotely. As of mid-June 2020, most schools reported that they were receiving fewer new-student inquiries, given the uncertainty of what the coming year would bring.

Considered for its broader and longer-term implications, beyond the independent school sector, this study elicits questions and almost demands reflection on the limits of centralized, bureaucratic structures in time of crisis. What is it about independent autonomous small schools embedded within the reciprocity of community relationships that not only leads to student wellbeing and achievement, but does so quickly, efficiently, and with fewer financial resources during time of pandemic and other hardship? And thinking beyond, what might this case study of resilience and effectiveness mean for excellence and equity in education, for student wellbeing and achievement, and for educator and community vitality in non-crisis times? If principles of subsidiarity hold such promise for times of crisis, might that also be true for non-crisis periods? If so, as we exit COVID, it might be time for us to consider that question anew.

References

CBC News. “TDSB Wants to Centralize Remote Learning in a ‘Virtual School’ as Part of COVID-19 Plan.” August 19, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/Canada/Toronto/tdsb-remote-learning-virtual-school-1.5691770.

Clemens, J., S. Parvani, and J. Emes. “Comparing the Family Income of Students in British Columbia’s Independent and Public Schools.” Fraser Institute, March 2017. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/comparing-family-income-of-students-in-BCs-independent-and-public-schools.pdf.

Lecce, S. “Letters to Ontario’s Parents from the Minister of Education.” https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education.

MacLeod, A., S. Parvani, S., and J. Emes. “Comparing the Family Income of Students in Alberta’s Independent and Public Schools.” Fraser Institute, October 2017. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/comparing-the-family-income-of-students-in-albertas-independent-and-public-schools.pdf.

Office of the Premier. “Health and Safety Top Priority as Schools Remain Closed.” Government of Ontario, May 19, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2020/5/health-and-safety-top-proiority-as-schools-remain-closed.html.

Office of the Premier. “Statement from Premier Ford, Minister Elliott, and Minister Lecce on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19).” Government of Ontario, March 12, 2020. https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2020/03/title.html.

Stockland, P. “Beyond Academics.” Convivium, June 1, 2020. https://www.convivium.ca/articles/beyond-academics/.

———. “Independence and Inequality.” Convivium, May 21, 2020. https://www.convivium.ca/articles/independence-and-inequality/.

———. “Recalibrating Education.” Convivium, May 25, 2020. https://www.convivium.ca/articles/recalibrating-education/.

———. “Upholding Community.” Convivium, May 27, 2020. https://www.convivium.ca/articles/upholding-community/.

Swaner, L.E. and C. Marshall Powell. “Christian Schools and COVID-19: Responding Nimbly, Facing the Future.” Association of Christian Schools International, May 2020. https://www.acsi.org/docs/default-source/website-publishing/research/acsi-covid-19-survey-report-final.pdf?sfvrsn=b4b7bf3d_2.

Van Pelt, D., D. Hunt, and J. Wolfert. “Who Chooses Ontario Independent Schools and Why?” Cardus, September 9, 2019. https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/who-chooses-ontario-independent-schools-and-why/.