The American idea is rooted in a belief that people from varied religious and ethnic backgrounds can unite to create a single nation: E Pluribus Unum. That is no easy task. As history bears witness, identity differences can easily become a source of social tension, discrimination, and conflict.

- Aspen Institute, “The Inclusive America Project”

Introduction

Non-government, and especially religious, schools are often considered damaging to social cohesion. Advocates of public, government-run schools suggest that the inclusiveness and diversity that comes from being available to every student in the community teaches students about learning to live together in difference. The implication is that the very existence of non-government schools as an alternative undermines the government system. To add to the challenge, the perception is that identity differences are emphasized, rather than mitigated, by such schools. In short, religious schools are peace-breakers rather than peacemakers.

This report challenges that assumption. Relying on outcome-based data from several surveys of adults who graduated from religious schools, as well as a survey of religious leaders, we argue that the value of religious schools for creating civic virtue has been underappreciated. Further, that religious schools and places of worship, at their best, offer vital seedbeds of belonging, trust-building, and civic formation for a “principled pluralism.” While we suspect that this is true more generally, the data suggests that new conversations are necessary between parents, church leaders, and school leaders to better understand, benefit from, and use religious schools in a manner that would maximize their ability to contribute to social virtue in increasingly pluralistic societies.

But America today seems void of a vision—a vision that gives meaning and order to the present chaos, a vision that inspires trust again, and a vision that includes the recollection of shared humanity and a common narrative, shared purpose and the common good.

America's Fractured Culture

That we are in the midst of a culture war with fractured trust there can be little doubt. American media now offers up a daily dose of fuel for a war that has been framed as a zero-sum game. American society remains the most highly religious in the Western world, despite its growing diversity and secularization. Religion increasingly aligns with political affiliation, and with media, further exacerbating these divides. While Americans may not be on the battlefield at home, life increasingly feels like a war is being played out for the American heart, mind, and soul. Amid this so-called culture war, Americans are growing weary of a culture that feels chaotic and negative, and increasingly suspicious of its leading institutions. Leaders, on the other hand, concern themselves with the fracturing of trust, social cohesion, and civil discourse that have been at the very heart of the American ideal. On a personal level, an atmosphere of distrust undermines the capacity for meaningful relationships. This retreat within, so to speak, is no doubt connected to the growing numbers of people who feel socially isolated—one of the most significant mental-health epidemics of our time. The universal need for belonging, meaning, respect, and community seems to become all the more evident in a highly fractured world. But so too is the need to live together well in our difference; to live out the biblical call to love our neighbours.

Principled pluralism offers a social and political vision that allows different competing or conflicting views to coexist in respect and peace and tension, each oriented in its own way toward a shared public good.

Some paint a picture of religious spaces as ammunition factories in a culture war or as bunkers for like-minded combatants. Others could not disagree more. They argue that these spaces offer valuable—if not crucial—incubators of public goods and virtue, and much-needed spaces of belonging. Religious schools and places of worship are increasingly the subject of these debates. Careful attention to data can help us discern which picture is more accurate as a general rule. What role do these religious institutions really play in a pluralistic and fractured society? Are they peacemakers or peace-breakers in the current culture war? As these debates grow, both sides seem to be talking past one another or speaking into echo chambers that can further entrench these divides. The challenge, for both critics and defenders alike, is to move beyond these tendencies and narratives. But America today seems void of a vision—a vision that gives meaning and order to the present chaos, a vision that inspires trust again, and a vision that includes the recollection of shared humanity and a common narrative, shared purpose and the common good.

A Vision for America's Restored Culture

In a 2013 Comment magazine article, “The Point of Kuyperian Pluralism,” Jonathan Chaplin makes the argument that Abraham Kuyper’s vision of pluralism should still inspire Christians and others today. The goal of Abraham Kuyper, prime minister of the Netherlands between 1901 and 1905 and influential political reformer and neocalvinist theologian, was that Christians should be seeking parity, not privilege. The intended outcome: equity and justice—for all, and not justice for “just us.” To do so would be a correction to politics as usual, elevating the common good over the self-interest of one’s tribe, right or left, Christian or secularist. The aim is, therefore, “to enjoy equal rights alongside other communities within a constitutional democracy marked by wide freedom of expression, fair representation, and a diversity of voices.” Chaplin cites James Bratt in the opening of Abraham Kuyper: Modern Calvinist, Christian Democrat, in which Bratt offers this judgment: “Perhaps Kuyper’s greatest significance for our own religiously and culturally fractured world is the way he proposed for religious believers to bring the full weight of their convictions into public life while fully respecting the rights of others in a pluralistic society under a constitutional government.” Kuyper’s leadership inspired a number of democratizing movements in nineteenth-century Dutch society, including the establishment of genuinely pluralistic arrangements in education, health care, labour, broadcasting, and elsewhere. In such systems, a diversity of both religious and secular service providers were integrated into a public system, supervised, and eventually funded, by the state.

Where does a generic, secular liberalism provide communities of practice where citizens can acquire the dispositions of tolerance, humility, and patience?

Religious Education and the Common Good

Determined to live together well, to respect difference, and to enlarge public conversation on key policy issues, Cardus has a long-standing interest in the connections between faith, society, and the public good. For almost a decade now, the Cardus Education Survey (CES) has been collecting data from a representative sample of 1,500 American high school graduates between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-nine. The CES is intent on exploring a number of key questions, including: Do religious schools form isolated enclaves that could promote mistrust and withdrawal? Do these spaces make valuable social and civic contributions to society at large? Cardus Education Surveys—released in 2011, 2014, and forthcoming in 2019—are now considered the most significant representative measurement of academic, cultural, civic, and spiritual outcomes in independent and religious schools the United States.

What does this data show? Interestingly, it shows that private and religious school attendance exerts a long-term positive influence on civic measures and outcomes, with one component of adult civic engagement standing out in particular: giving and volunteering. Religious school graduates make more charitable donations and are more likely to have volunteered in “Other Causes” than public school graduates. Graduates from protestant schools are much more likely to go on a social service trip and to donate money or goods to an important cause or organization. And graduates from Catholic schools are the most consistently positive on giving and volunteering, showing a higher likelihood of volunteering outside the congregation and donating to charity, including secular and political causes. In other areas of civic engagement, religious school graduates report levels similar to public school graduates and have strikingly similar attitudes and experiences in civic and political matters as well. This is evident in levels of political interest, feelings of obligation to participate in civic affairs, levels of civic participation, and trust in organizations.

Seeing themselves as citizens of the world, these graduates live out their faith by contributing to and engaging with society in a number of important ways. Beyond this, CES data also points to the value of religious schools in offering spaces of social cohesion and belonging—aspects that can have longer-term effects on civic engagement. Graduates of religious schools are more likely than public school graduates to think positively of their high-school years. Their capacity for close friendships and intimate conversations are also positively connected to these schooling experiences.

Private and religious school attendance exerts a long-term positive influence on civic measures and outcomes, with one component of adult civic engagement standing out in particular: giving and volunteering.

In fact, the positive contributions of faith institutions to the broader public good have been largely recognized by mainstream society. It is difficult to overstate the impact of these institutions in areas such as health, education, and poverty; something that is not at all surprising given their historical emphasis on charity and social service. More recently, serious attempts have been made by a number of researchers, including Cardus Social Cities Program Director, Milton Friesen, to develop methodologies to quantify these public-good contributions at a community level. See, for example, the Halo Project at haloproject.ca.

Religious Education in the Public Square

But while these public contributions have been largely acknowledged, the potential value of these religious spaces for cultivating civic virtue has been largely ignored. At their best, religious schools and other religious spaces can offer valuable communities of practice where particular dispositions of tolerance, humility, and patience can be formed. Failing to see these connections, opponents of “school choice” commonly argue that regardless of output, public tax dollars should not be spent on supporting non-public schools, as if families using these schools were not part of the public itself. Despite the regional and cultural variations within American government school districts, there is still a prevailing view that government-run schools are the only places where the “fringes” can be civilized and neutralized. However, in actual fact, nothing is “neutral.” As Cardus senior fellow Ashley Berner explains, all schools—religious or not—are “meaning-making spaces.” A pluralistic society engenders the need for differentiated spaces, and these differentiated spaces may in fact be critical for belonging, cohesion, and civic formation.

While a principled pluralism sees value in plurality, it also understands the need for important conversations around its limitations and challenges. […] It is necessary to engage deeply and honestly with faith leaders themselves to understand how they envision their civic role in the current context.

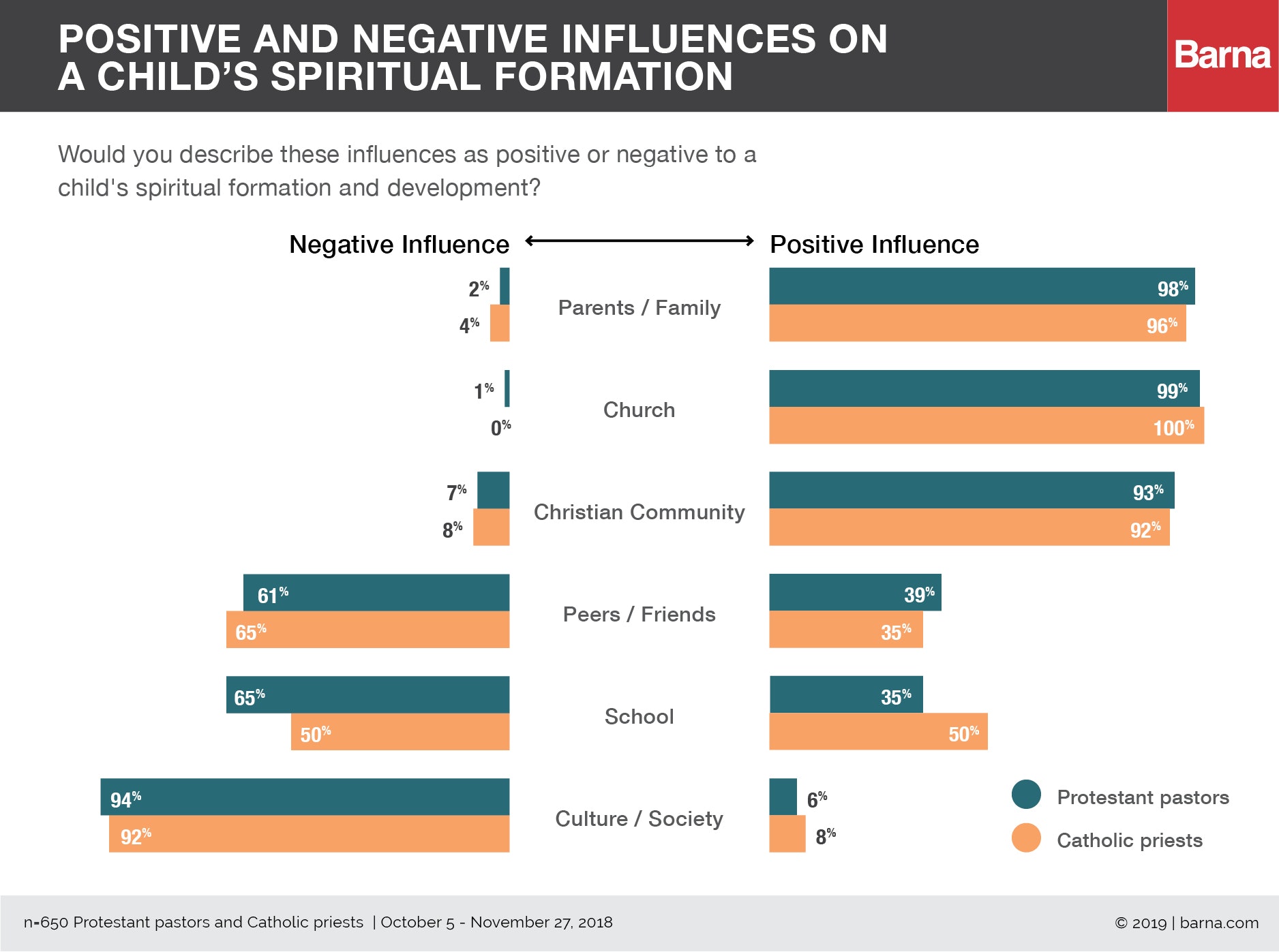

But at the same time, while a principled pluralism sees value in plurality, it also understands the need for important conversations around its limitations and challenges. If faith spaces, at their best, are to play a key role in a new civic vision, then it is necessary to engage deeply and honestly with faith leaders themselves to understand how they envision their civic role in the current context. Are they having key conversations about this, building relationships and trust in and beyond their own communities? Keen to probe these questions, Cardus in partnership with Barna Research recently conducted a survey of 650 Protestant and Catholic clergy to gather their perceptions and experiences of education, child development, and spiritual formation. Perhaps the most important finding from the survey is that churches, parents, and schools are not speaking to one another on these important matters nearly enough. In fact, our data points to disconnected and stifled conversations, both within and between these spaces. Church leaders universally agree that family has the most significant influence on a child’s development and spiritual formation and that churches play a secondary role. Both Protestant and Catholic leaders perceive schools—alongside peers—as having a largely negative influence on a child’s spiritual formation and development. Christian community is ranked by pastors as having the least amount of influence in either a positive or negative direction.

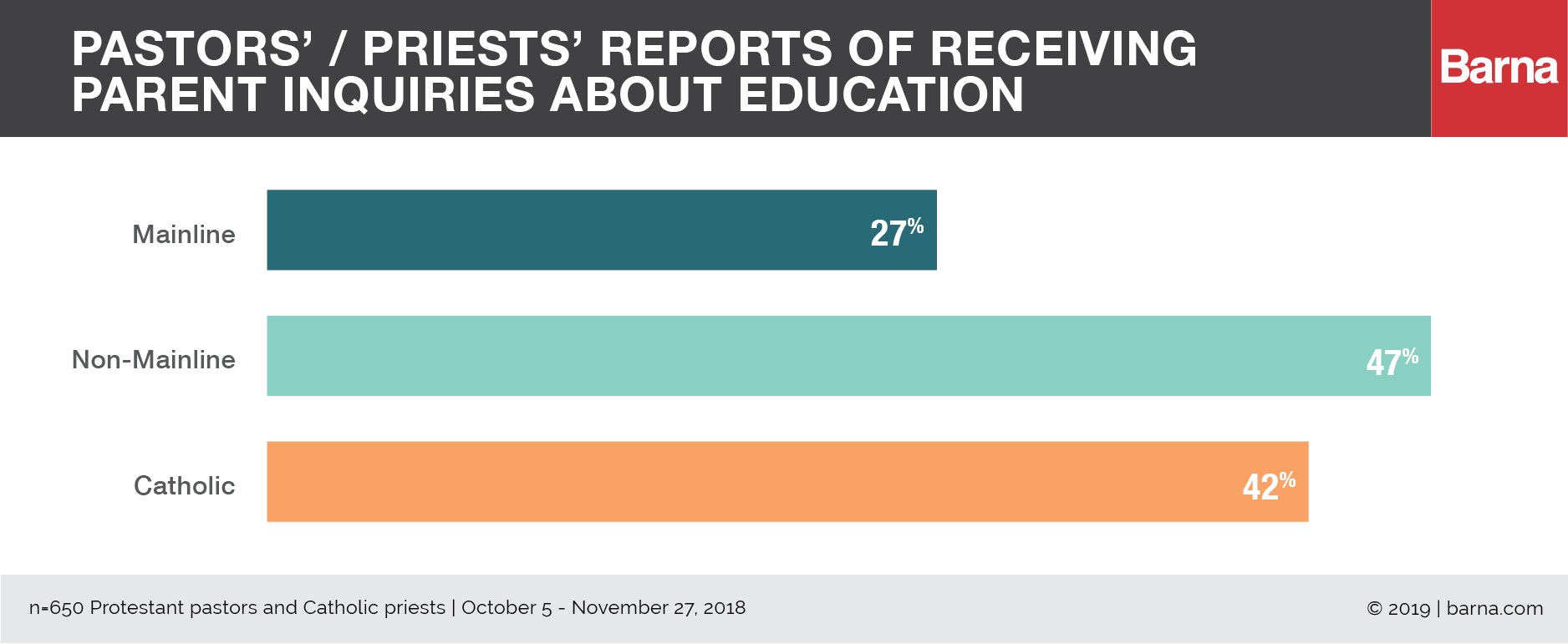

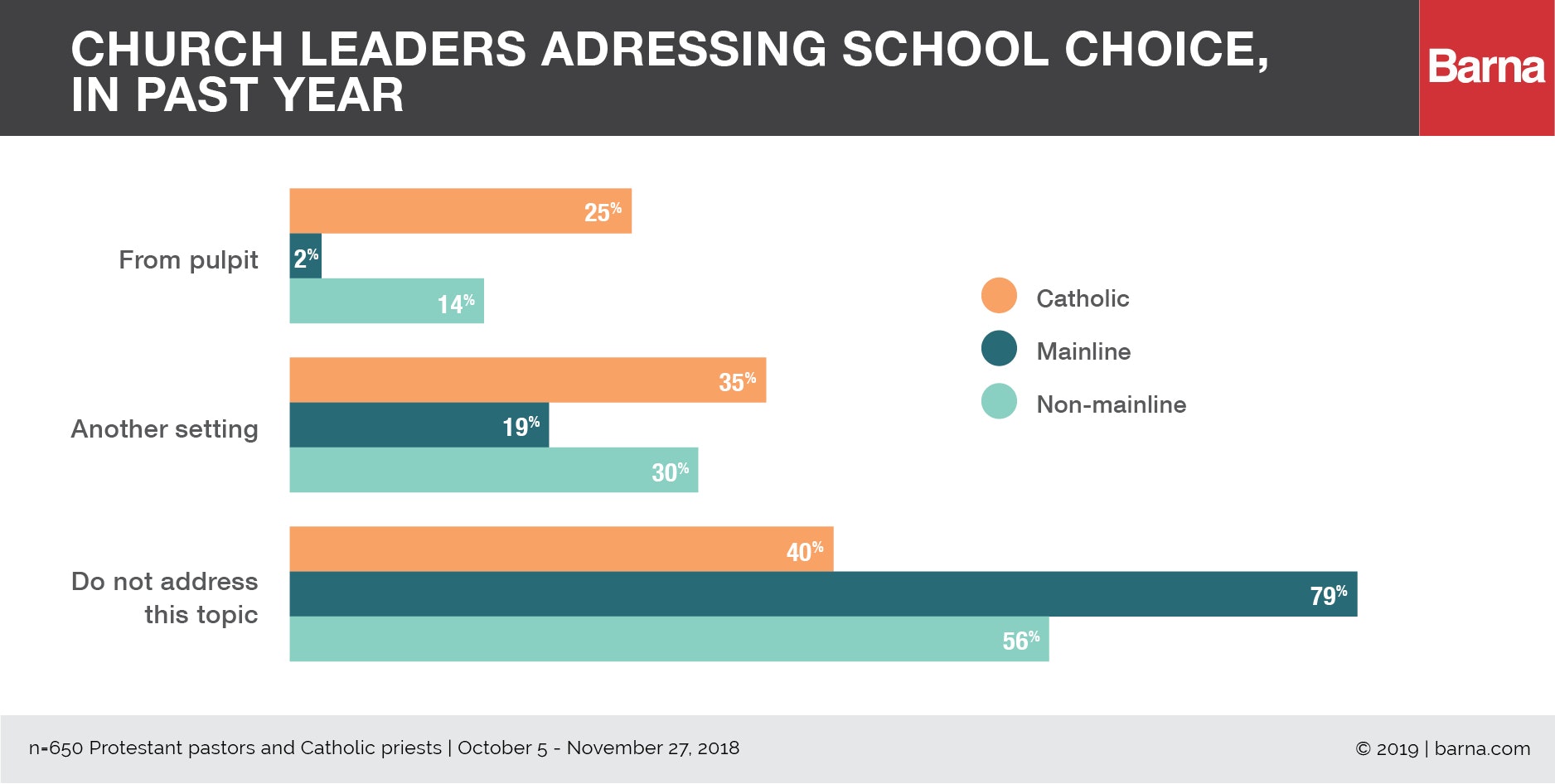

Yet despite these perceptions, the majority of Protestant churches have never been associated with a school, and the majority of both Protestant and Catholic clergy have not been asked by a parent for an opinion on what school might be best for their child. Moreover, of those Protestant pastors who have been approached over the past year, just 48 percent said they recommended an independent Christian school, citing affordability as a main concern. Only 2 percent of mainline Protestant and 14 percent of non-mainline pastors have addressed school choice from the pulpit in the past year, though 19 percent of mainline and 30 percent of non-mainline pastors have addressed this in another setting.

Catholic priests were much more likely (at 69 percent) to have attended a Catholic school and to recommend Catholic schooling (90 percent). They were also more likely to address school choice from the pulpit or in another setting. The greater comfort and connection between Catholic churches and schools can be largely explained by the historical arrangements between these institutions.

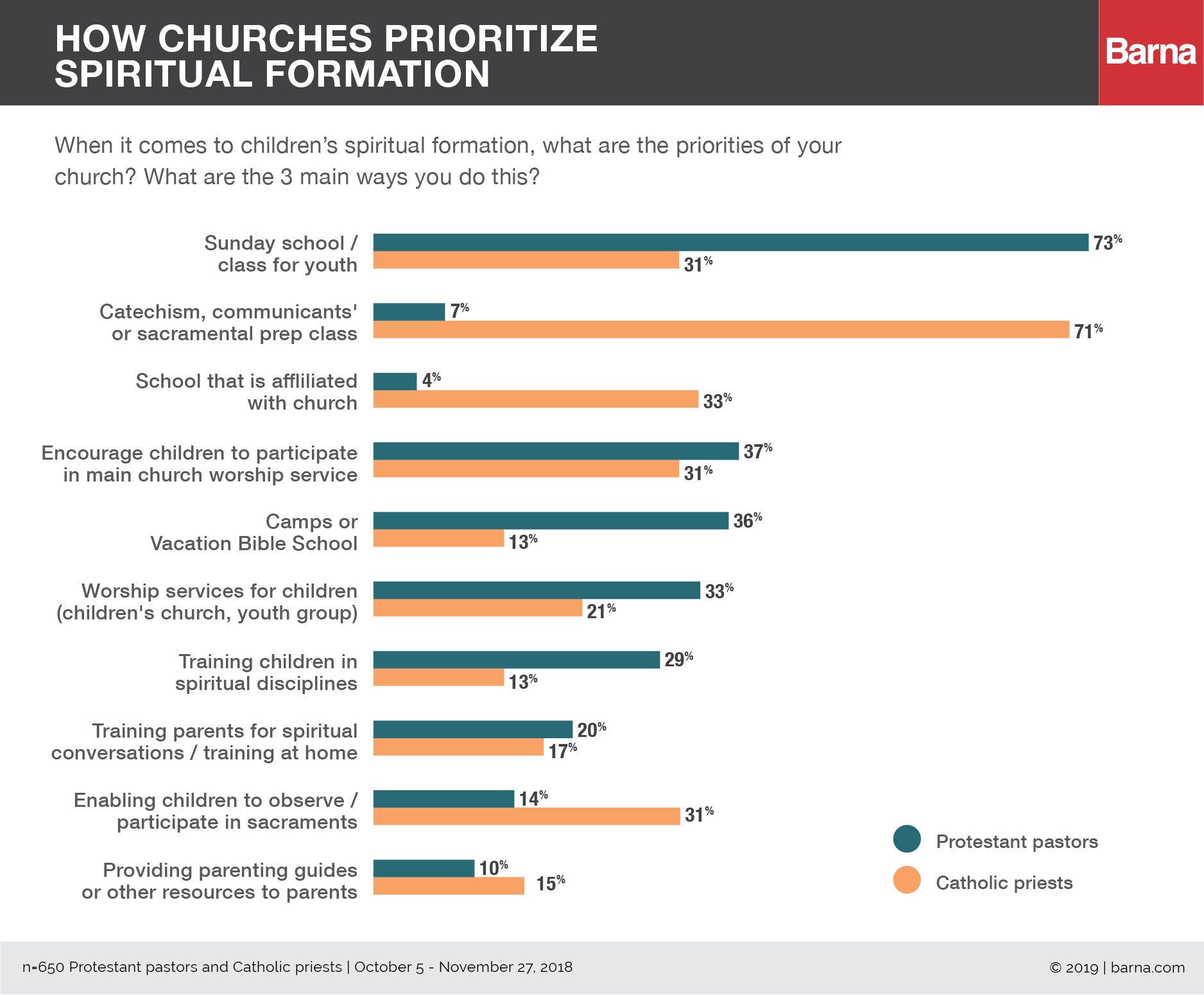

Our survey of clergy also exposes a gap between churches and parents. While Protestant and Catholic churches dedicate a large amount of time and energy to spiritual formation, less attention is given to facilitating effective formation and transmission beyond the immediate church context. There is very little emphasis placed on equipping parents to provide spiritual guidance or hold spiritual conversations at home, despite viewing parents as bearers of the primary responsibility for child development. Church leaders can play a vital role in child formation and development, but conversations with parents are key to understanding the particular challenges they are facing.

How can we explain these stifled conversations? A recent Barna report, “Faith Leadership in a Divided Culture,” concludes that American culture raises the stakes for faith leaders as they address many of the controversial issues of the day. Pastors feel most pressured to speak out on the same issues that they feel limited in talking about. In other words, the squeeze comes from all sides: those demanding that the church take a stand and those outraged when it does. Churches and church leaders are, therefore, not immune from the counter-pressures of society. These spaces, in fact, reflect and translate societal debates at a local level. In so doing, places of worship also offer important community spaces where parents, teachers, and church leaders come together to develop a shared sense of meaning in the midst of societal tension and confusion. However, our recent survey of church leaders paints a picture of fracture within the church. Faith leaders are withdrawing from key conversations with both parents and teachers on education and faith formation. Further, their hesitation to recommend religious schooling suggests a need for stronger relationships and more dialogue between churches, parents, and schools to explore the possible benefits of religious schools. But perhaps most troubling of all, the stifled and disconnected conversations in these spaces may have broad implications for civic engagement and society as a whole.

“Spaces of grace,” which connect the need for belonging with human flourishing and civic formation, are vital for flourishing at both the personal and societal levels, precisely because they connect the formation of internal virtues and dispositions with external orientations and engagement. Spaces of grace engender the kinds of virtues that translate into an outward generosity of spirit and capacity to love amid the difference.

Moving toward a principled pluralism means engaging with differences—both in and between religious and secular communities—more deeply. Building a society that is deeply diverse and also “just” means thinking about those particular spaces or communities of practice that are poised to help cultivate important civic virtues. As communities of practice and belonging—based on shared norms and values—religious schools and places of worship can offer important incubators of both human flourishing and civic virtue. These “spaces of grace,” which connect the need for belonging with human flourishing and civic formation, are vital for flourishing at both the personal and societal levels, precisely because they connect the formation of internal virtues and dispositions with external orientations and engagement. Spaces of grace engender the kinds of virtues that translate into an outward generosity of spirit and capacity to love amid the difference. Spaces of grace can offer much hope for a principled pluralism.

Our surveys of graduate outcomes and church leaders provide a deeper look into these religious spaces to uncover some important nuances. Faith spaces do not automatically translate into spaces of grace, and faith communities must come to understand these important distinctions, think critically about the challenges before them, and collaborate with one another. Our research attests to the fact that these communities are not immune from outside pressures and show similar tendencies to withdraw from the important conversations that need to take place. Faith leaders play a vital role in driving the needed conversations and collaborations, even in—and perhaps especially in—the sensitive areas of education and civic formation.

Faith spaces do not automatically translate into spaces of grace, and faith communities must come to understand these important distinctions, think critically about the challenges before them, and collaborate with one another.

Works Cited

Bratt, James. Abraham Kuyper: Modern Calvinist, Christian Democrat. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. 2013.

Cardus Education Surveys. 2011–2018. https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/carduseducation-survey/.

Chaplin, Jonathan. “The Point of Kuyperian Pluralism.” Comment, November 1, 2013. https://www.cardus.ca/comment/article/the-point-of-kuyperian-pluralism/.

Inazu, John D. Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving through Deep Difference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Smith, James K.A. “Reforming Public Theology: Neocalvinism and Pluralism.” Herman Bavinck Lecture, Theological University Kampen. June 27, 2016. https://www.tukampen.nl/informatiepagina/smith-bavinck-lecture

“Principled Pluralism: Report of the Inclusive America Project.” The Aspen Institute, Justice and Society Program. June 2013. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/publications/principled-pluralism-report-inclusive-america-project/.

“Who Is Responsible for Children’s Faith Formation.” Barna. March 19, 2019. https://www.barna.com/research/children-faith-formation/.