Introduction

Indigenous Voices of Faith is a series of interviews conducted by Cardus in the fall of 2022, in which we asked twelve Indigenous people in Canada to tell us about their religious faith and experiences. Since 47 percent of Indigenous people in Canada identify as Christians, Christian voices are the primary but not sole focus of this interview series. The purpose of this project is to affirm and to shed light on the religious freedom of Indigenous peoples to hold the beliefs and engage in the practices that they choose and to contextualize their faith within their own cultures.

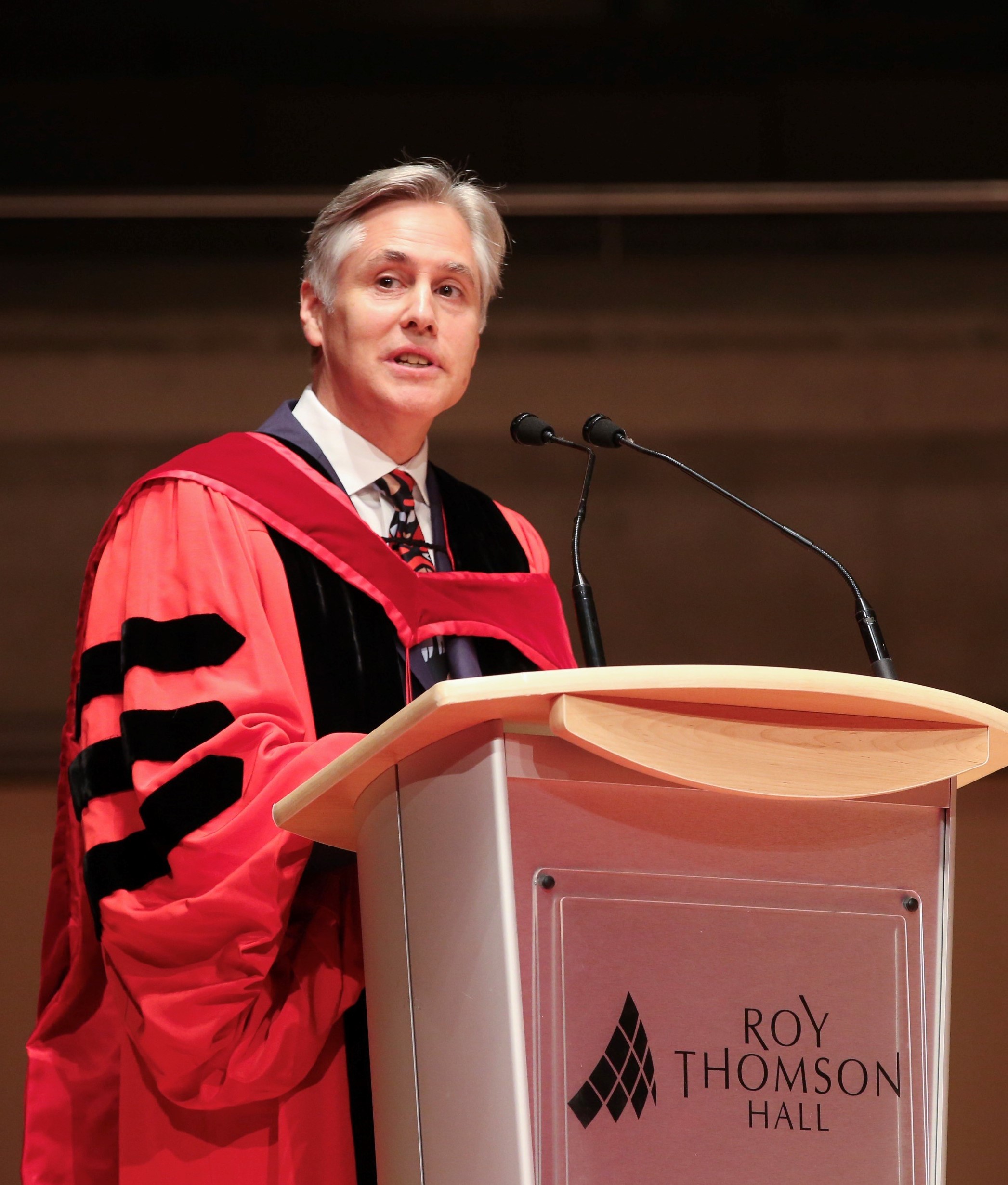

Father Deacon Andrew Bennett, program director for Cardus Faith Communities, interviewed Professor John Borrows in Victoria, British Columbia, on November 1, 2022. The interview has been edited for clarity.

Interview Transcript

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: John, thank you very much for taking the time to participate in this project. I appreciate it.

John Borrows: Yeah, happy to do it.

Fr. Dcn Andrew: So maybe to start, you can tell me a little bit about your Indigenous background and a little bit about your professional work, your family, wherever you’d like to go.

John Borrows: So, I’m Anishinaabe, and my nation is the Chippewa of the Nawash First Nation. We’re called Neyaashiinigmiing. It’s on the shores of Georgian Bay, Lake Huron, about three hours north of Toronto or four hours north of Detroit; our home territory is sometimes called the Bruce Peninsula or the Saugeen Peninsula. And that’s where my mom and sister live today, and that’s where my family on my mother’s side has been for generations.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Tell me a little bit about your professional work as a lawyer.

John Borrows: So, I’ve been teaching now for thirty years as a law professor. I’m currently the Loveland Chair in Indigenous Law at the University of Toronto Law School. That’s where I did my law degree and a portion of my graduate work. I teach Canadian law dealing with Aboriginal peoples. I also teach Indigenous peoples’ own law and their revitalization processes. And I like to write; and of course I love to teach as a part of what I do. It’s been rewarding to try to figure out the relationship and how it can be improved, between Indigenous peoples and others in the country.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Wonderful. And you’re married and have a family. Tell me a bit about your family.

John Borrows: So, I’ve been married now for thirty-eight years, I think it is. And I have two children, thirty-six and thirty-four. My thirty-six-year-old has autism, and she is my greatest teacher, and she’s an amazing person of light. And then my thirty-four-year-old daughter, my youngest daughter, is now a professor at Queen’s University Law School, and she works in the same field that I do. I have two grandchildren, Waseya and Akeeka. Waseya is an Anishinaabe word, meaning “shining bright and clear.” And then the youngest one is Akeeka, which means “the fullness of the earth” or “there’s lots of earth, an abundance of earth.” And so it’s wonderful to see their names reflecting the earth and the sky and the way that they’re coming into this beautiful life together.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Wonderful. So much of the focus of this project is really to understand how Indigenous Canadians engage with their faith. So, can you tell me a little bit about your own faith, your faith journey, and how your faith informs your life, your work? Just feel free to speak freely on that topic.

John Borrows: Sure, sure. So, some of my formative experiences were trying to understand the mystery of life. I can remember being a young boy watching hockey every Saturday with my father and enjoying time socializing with him. One night though, I remember withdrawing myself, and going to my room because I felt unsettled about life’s seeming uncertainty. And withdrawing myself, and facing those feelings of unsettledness and uncertainty really took me to a place of deeper contemplation. I was eight or ten years old at the time and I felt a little overwhelmed, wanting to know what was around me.

And in the quiet of that small room I found a presence, a comfort, a connection, a purpose, an understanding that life is more than the mere unfolding of days. In those quiet moments, I understood there is something beyond ourselves. And so, as I grew, I would look for quiet places. I often found peace in the beauty of the natural world around me. We lived on a farm, 150 acres, with a hardwood bush and ravine and pond. And so I’d wander across the land finding connection and feeling that beauty. And for me this was a very spiritual experience.

So, contemplation was found in the beauty of the land. I can remember going to the forest and praying. I can remember noticing the sound of the birds and the streams and the changing of the seasons and understanding the relationship we have with the Creator of the earth and having that feeling as a part of life, even as I treasure evolution’s truths too. This is an important dimension in my spirituality.

And I think my mother helped introduce me to that way of being. It was a part of her practice of spirituality. Whenever she needed to feel peace, she would go outside to some quiet place, and contemplate, pray, and look up at the stars; she would take the snowmobile out in the winter, and lie on the seat and look up at the heavens. So that was fantastic.

But, also, when I was probably about four or five, she bought me some illustrated Bible stories, in eight volumes. They were various Old Testament stories, from what I remember. She read them to me. Those stories are also a part of my spiritual formation. And she herself had experienced being nurtured in the United Church. And my great, great, great, grandfather, my third great grandfather, converted to Christianity as a Methodist back in about 1811, somewhere around there. And so we have been Christian for many generations.

The Methodism of my great-great-great-grandfather was passed on to my great-great-grandfather and then it was passed on to my great-grandfather, and he was the person that taught my mother how Anishinaabe and Christian teachings came together. He was the most loving male figure in her young life. And there was a church that my great-grandfather built on the reserve. It’s still standing, a beautiful stone church. She could always remember going to church, and he would have the stove prepared so that the place was warm and welcoming when people arrived. She remembers going there, and people only singing in Anishinaabemowin and worshipping God through their language, songs and sociality. She felt like she was welcomed in so many ways.

And she would often go to her grandfather’s (my great-grandfather) for dinner on Sunday. And while they were gathered, hosting other people in the community, he would always read the Bible with them. And he carried a deep devotion through prayer, through scripture study. This really impressed my mother. And so spirituality came into my life through my mother’s relationship to the land and also through her love of God and Jesus Christ and scriptural traditions.

Christianity was a challenge for her too, because her father had been abused on the reserve in day school by Christians. And so he was somewhat antagonistic to church. Although he felt like there was a place for it, ultimately, I think he rejected it. And so there was a little conflict between my mother and her father in that regard. On the other hand, my mother’s mother, who is non-Indigenous, was raised in Salt Lake City. Her father played the organ for a living. And in that city you couldn’t get paid for playing the organ if you were in a Latter-day Saints (LDS) congregation, because they are lay congregations and people participate without being paid. I think my grandmother felt and remembered the LDS people there. She eventually moved on to Los Angeles where she met and married my grandfather, who was a Hollywood Indian in the 1930s! They worked in Universal Studios. He was on set, acting, and she was a set costume designer, and these experiences brought them together. When Pearl Harbour was bombed in the Second World War she eventually went to the reserve to live with him there.

And then many years later, when the LDS missionaries came along, she said, “I recognize you,” having had that experience growing up in Salt Lake City. And my mother, in fact, had already joined this church. She converted from the United Church to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in about 1969. And so the LDS church started to be a part of my background as well. I can remember when my mother was baptized and what a change that was for her. And then I started going to church with her, and then I myself was baptized when I was eighteen.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: So that’s a very formative time for you. That would’ve been in your mid-teens, I guess?

John Borrows: Actually, it was a little earlier in my life. My mother joined the church when I was six. I didn’t attend at first, but started when I began high school. And I attended what’s called seminary in those years, which is an early-morning scripture study every day. I did this for five years because we had grade 13 in Ontario; so I had a religious education from grade 9 to 13, from about 6:30 to 7:30 every morning. And I loved this experience. It was great to learn. My mother was even my formal seminary teacher for one of those years. And like I said, my baptism occurred when I was eighteen. My father didn’t want me to be baptized when my mother first joined the church. He wanted me to wait until I was more fully formed. And so eighteen was the year he said I would be free to make my own choices in such matters. So I went to church with my mother for six or seven years without being formally a member. When it came time to decide for myself, at eighteen, I took that step and was baptized.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: And your father is also a Latter-day Saint?

John Borrows: My father’s not a Latter-day Saint. He grew up in Yorkshire, and he came across the ocean, after the Second World War. He was from outside of Sheffield, in a place called Rotherham and Barnsley. It was bombed often. And so he was fleeing those sorts of traumas. And he came to Canada in that way. His favourite subjects in school were scripture and Latin, but he didn’t feel he could commit to religion.

So I had options in my home: a pathway for embracing Christianity, and a pathway for respecting Christianity but holding it at arm’s length. And I feel like I benefited from both of these views. I can see the value of immersion in a tradition, but I also see the value of critical thinking and understanding different perspectives and holding other possibilities in mind. And perhaps part of my life is worked out by trying to negotiate between these two perspectives developed in those formative years. This means I value critique, and I value doubt, but frankly I also value faith and I value action and activity in a tradition.

I can see the value of immersion in a tradition, but I also see the value of critical thinking and understanding different perspectives and holding other possibilities in mind.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Well, there’s nothing wrong with doubt. As one priest said to me once, “Doubt is not a sin, but it’s a process whereby we come into a deeper engagement with God and to understand him more fully. Even though he’s not fully understandable, we can enter in full more fully into his presence.”

John Borrows: And that’s what I feel like. I still feel like that young boy of eight years old, wondering whether there is more to life than the present moment. My feeling of emptiness led to life filling with meaning. And I find that doubt, or questioning, or inquiring . . . seeking, I guess is a better word. Being a seeker is not feeling like I’m certain about everything but continuing to try to find what those horizons are. When I do the work, I feel filled by it.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: And are you active in a local LDS stake here in Victoria?

John Borrows: Yes, that’s right. We have seven congregational units organized as our ‘Stake,’ here is the Victoria, British Columbia Stake. And I am in one of those congregational units (called a ward) here. And in the past I was part of our Stake presidency, which is an ecclesiastical responsibility, and now I serve through facilitating communication about our and other’s faiths. This largely sees me as being the chair of the Victoria Multifaith Society (VMS) here in the city. And so I feel like that’s my calling: to work in that multi-faith space.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Well, it’s wonderful because I know a lot of my exposure to the Latter-day Saint world has been through Sandra Pallin, who is very much involved not only public affairs but also in a lot of interfaith work. So, tell me a little bit about your interfaith work for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, what that looks like and how that maybe fits in with that seeking you were speaking of.

John Borrows: Yeah, that’s right. I know Sandra well. We are similar in age and we are both law graduates, and we are both interested in interfaith work. And multifaith work is beautiful. One of our teachings by one of our prophets, Gordon B. Hinckley, is to “keep all the good that you have and add to it,” and “if there’s anything virtuous, lovely, and of good report we seek after these things.” And so I find so much truth, beauty, and inspiration for faith in that multifaith space. This is one of the reasons I’m on the VMS board. I’m actually the chair right now in the Indigenous spirituality space. But there’s also members of the board who are Christian and Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Bahá’í, Buddhist, Hindu, and non-affiliated. There are nine of us on the board.

And we support one another by asking this question: “How does our faith tradition help us deal with X issue in the following ways?” And so we gather and we talk about how our faith traditions help us deal with racism, or environmental challenges, or feeling the struggles of the pandemic, those sorts of things. We’re always asking about how our faith traditions are relevant in a contemporary setting. It’s enlightening to listen to someone who’s Jewish, or Muslim, or Hindu, or Sikh talk about how their faith helps them deal with pressing issues. It reminds me of why I love the living nature of faith. I love the fact that I can learn from other faiths and apply their teachings in my life as well. It’s an expansive celebration of finding support for one another.

And then of course we do work more generally in the community, with memorials related to the Holocaust, or the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, or whatever the case might be. We also gather and celebrate holidays, whether they be Hindu, or Sikh, or Jewish—whatever the case might be. And it’s an environment of friendship. And again, for me, it bolsters my faith because I feel it advances one of the central tenets of being LDS.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Now the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is very mission-oriented. Did you yourself go on mission?

John Borrows: Yes.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Maybe you could say a little bit about that.

John Borrows: As I mentioned, I didn’t join the LDS church until I was eighteen. And at that time, young men could serve as missionaries at the age of nineteen. And so when I was baptized, even though I had been going to seminary for about five years, I felt a kindled desire to want to serve in that capacity. So I spent grade 13 preparing for a mission as well as preparing to graduate from high school. We were expected to pay for our mission from our own funds, so I was working and saving money, and also reading the Bible and the Book of Mormon and other scriptures to prepare to serve others.

And so, when I turned nineteen, I put my papers in, requesting a call to service, and that call came to serve in the Nevada Las Vegas Mission. So I went to the southwestern deserts of the United States, and that was a great experience for me. The congregation I had grown up in was quite small, about forty people. And when I got to Las Vegas, I realized there were fifty plus congregational wards there, and it was a huge LDS centre of population. This is partially because Nevada is in the inter-mountain west, with the Latter-day Saint population spread out along those rocky mountain corridors. And there were many, many congregations and people who I associated with who helped me to see (in addition to a theological beauty to the church), that there was also an incredibly rich sociality to the church that I had never experienced.

Additionally, there were young men I served with from all over the place, including people from Washington and Minnesota and Tonga and England and Australia, and other parts of the world. It was a fantastic chance to get to live with people who were living their faith. And we would get to know the goodness of the local people too, as we were invited into their homes. I saw many different people from various walks of life, living their faith in different ways.

I have to say, I felt the world was a loving and beautiful place. Even though not everyone wanted to hear what we had to say, people would welcome us in. They’d give us glasses of water. They’d wish us well, even when they said, “We don’t want to hear what you have to say.” I felt wrapped in love and supported in so many different ways.

So yeah, that was my experience on a mission. I served in some leadership capacities too. We visited other companionships throughout Nevada, northern California, and northern Arizona. And so we had a really nice wider view of the area too.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Now in that part of the United States is a fairly significant Indigenous population. Did you have much interaction at all or any with the Indigenous communities?

John Borrows: Not so much. The Paiute communities are there and the Shoshone communities are there. And there were people from these communities who I got to meet who were part of the church there. But Nevada is not like Arizona, where there are twenty-two tribes that make up 25 percent of the state’s land base. And we meet some of the Indigenous folks in northern Arizona, in the Peach Springs area, for instance, who were very, very much a part of our church congregations. But in the other parts of the state, Indigenous peoples would tend to be intermingled without our units, as opposed to some predominantly Indigenous congregations you would find if you went further into Arizona or in some places in Utah.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: And what would you say about your Anishinaabe heritage and that early kind of spiritual experiences you had of encountering God’s presence in nature? How do they inform your Latter-day Saint faith?

John Borrows: I think my Anishinaabe and Christian spirituality complement one another. For example, when I was a young man I went on a Vision Quest, just like some other Anishinaabe people. After preparation, fasting and being alone in the forest I found myself in a closer relationship with the natural world and with my Creator—the power we often call the Great Spirit, Gitche-Manidoo. I have also prayed and fasted throughout my life as part of my Christian faith. This has also brought me closer to God and the earth’s beauty.

Another example relates to my everyday life. I’m a daily runner, and every morning I’m outside, I’m praying and I’m trying to receive the beauty that the world has to offer. Of course, you don’t have to be Anishinaabe or spiritual to do this. But being Anishinaabe and LDS, I find a particular meaning in greeting the day in this way. It sets the right tone for what I do. Before running, I wake up in the morning and I study scriptures for about an hour, and I’m very wide in my study. For example, I’ll study the Old Testament. Right now I’m going through Robert Alter’s translation of the Hebrew Bible. He’s a Jewish scholar. And I’m loving his translation and insights. Before that, my friend Ben Berger gave me a copy of the Tanakh and the Etz Hayim, and I was able to read (in translation) the Torah with the commentary around that.

And then, recently, for about two years I was reading a translation of the Qur’an every day. There’s The Study Quran by S.H. Nasr that was produced about maybe seven years ago. I also read Buddhist texts, such as the Dhammapada; in fact I was reading it this morning. Thomas Merton is someone I very much admire, so he’s often in the rotation of reading. I also read the Book of Mormon as a part of my study too, and the New Testament. And right now I am reading a translation of the Bible by Eugene Peterson, called The Message.

So anyways, I read these sorts of things, and then I go out running, and as I’m running, I’m carrying the ideas in my mind, and at the same time I am also carrying my love and appreciation for the beauty of the world. And I feel like this practice sets my day and helps me with the rest of what follows. And yeah, I mean, we could have a conversation right now about some of these things, and that’s my daily spiritual practice.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Well, if there’s one theme, I would say, John, that’s come out in many of these interviews that I’ve undertaken for this project, it’s this idea of integration, that as human beings, we are tripartite body, mind, soul. And to try and separate out different aspects of ourselves is really a bit of a fool’s errand. And so we were talking before we began the interview of this, I would call it certainly a very false narrative, that somehow Indigenous Canadians can’t live out a faith tradition that is somehow foreign or perceived as being foreign to what might be called Indigenous spirituality. How do you respond to that narrative that is present, especially in the media these days and in various elite circles?

John Borrows: So, I understand this important narrative, because there have been many challenges that Indigenous peoples have encountered with many traditions. I see these challenges in my own profession in the way the common law undermines Indigenous communities. Christianity has also marginalized Indigenous peoples, and I don’t want to ignore this problem either. It’s huge. But for myself, I find the teachings of Jesus coincide with my love for others, and for the earth. I love his invitation to, “Consider the lilies of the field, how they toil not, neither do they spin, but Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like unto one of them.” I feel this verse invites me to find God’s love for us in the lilies of the field—in nature. Or when I think about his parable of the mustard seed I find my hope for the future expands. Jesus taught that if you have a faith the size of a grain of a mustard seed, and you cultivate that seeded faith, it can grow to be a great tree that will accommodate others. Faith can provide nourishment and shelter when it is generative and expansive. I also appreciate Jesus’s teaching about how seeds that fall in different types of ground prosper according to the ground’s broader conditions. Jesus is comparing the grounds of our soul, to the seeds of truth found in his teachings. From this teaching, I look at the earth and I look within myself, and I see the connection regarding the need for receptivity. Or I think of the words of Isaiah, who teaches us about the Creator’s power through coastlines and the mountains, or about how faith helps us rise up like eagles.

And there’s so much in the tradition that has us find God in the beauty of the world that surrounds us. And so for me, those aren’t two things. I read those scriptures and I practice Anishinaabe spirituality, and I feel like there’s an integration. I’m not walking in two worlds at that moment. I’m walking in a world that’s both Anishinaabe and Christian, and I feel whole, I feel complete. I feel like they are challenging me to do the same thing, which is to love God and love creation, love our fellow beings and all that’s given us. And so I delight in trying to find that connectivity. So, for me, my faith is putting those things together.

I’m walking in a world that’s both Anishinaabe and Christian, and I feel whole, I feel complete. I feel like they are challenging me to do the same thing, which is to love God and love creation, love our fellow beings and all that’s given us.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Wonderful. Well, thank you very much. Any last thoughts you’d like to offer on some of these topics that we’ve covered?

John Borrows: There’s such a beauty to the world, I think this is what I want to say. I really do believe in grace. I think we receive blessings that are unbidden. We are living beneath our privileges, there are so many opportunities for us to receive what is immanent. And that’s part of what I’m trying to live into. I want to say, yes, there’s a place for work and striving, and as we were talking about earlier, being active in a faith tradition, but there’s also a place to be open, to receive what’s already present. And for me, that’s what I’m trying to do, is clear away some of the world’s distracting clutter, so that I can be in a space of receptivity and peace. Peace is what I feel often in this world because of this approach. And there’s a lot of turmoil. And I work in a field that’s about adversarial systems, but that’s not all that I deal with in the world. And my faith brings me peace.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: That same peace that eight-year-old John Borrows encountered on the land.

John Borrows: Absolutely.

Fr. Dcn. Andrew: Wonderful. Well, thank you, John. God bless you. God bless your work.

John Borrows: Thank you so much.

Photos provided by John Borrows.