Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Introduction

For decades now, Canadians have been hearing there is a shortage of daycare spaces. It seems that no matter the city or province, the urgent-shortage storyline remains the same.

In fact, the empirical evidence contradicts this narrative. In two jurisdictions—the City of Toronto and the province of British Columbia—daycare vacancy rates are persistent and growing.

In April 2017, we re-investigated the City of Toronto, where the space surplus grew by 45 percent between 2009 and 2016. In Toronto, in the first three months of 2017, the average number of vacant daycare spaces was more than 4,600. 1 1 Helen Ward, “Is There Really a Daycare Shortage? A Toronto Case Study Shows Vacancies Despite Waiting Lists and Subsidies,” Institute of Marriage and Family Canada, April 2015. https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/articles/is-there-really-a-daycare-shortage/.; Andrea Mrozek, “Toronto’s Increasing Daycare Surplus,” Cardus Family, April 25, 2017. https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/5057/torontos-increasing-daycare-surplus/.

While this finding contradicts the usual narrative, it is based on data from a publicly available Ministry of Children and Family Development Performance Management Report. 2 2 Ministry of Children and Family Development. Performance Management Report. Volume 8, March 2016. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/family-and-social-supports/services-supports-for-parents-with-young-children/reporting-monitoring/00-public-ministry-reports/volume_8_draftv7.pdf.

Given the concern for evidence-based policy, high vacancy rates expose a shortage of demand rather than a shortage of supply. In British Columbia, the disparate vacancy rates among jurisdictions also indicate a need to consider how best to use allocated child care funds more efficiently. After all, “[e]fficient use of child care spaces will be reflected in high utilization rates,” the report’s authors write. 3 3 Performance Management Report, 15.

This article first examines the data showing daycare vacancies in British Columbia. Second, we’ll examine why those vacancies exist. Finally, we’ll discuss some of the possible reasons why we hear only about a shortage, and we’ll present new policy recommendations.

Vacancy Rates

The average daycare vacancy rate across British Columbia, including licensed centre-based care and family care, and across all child ages from infant through to school age, is 30.9 percent. 4 4 Calculations based on “Group and Family” utilization rate. Ibid., 17.

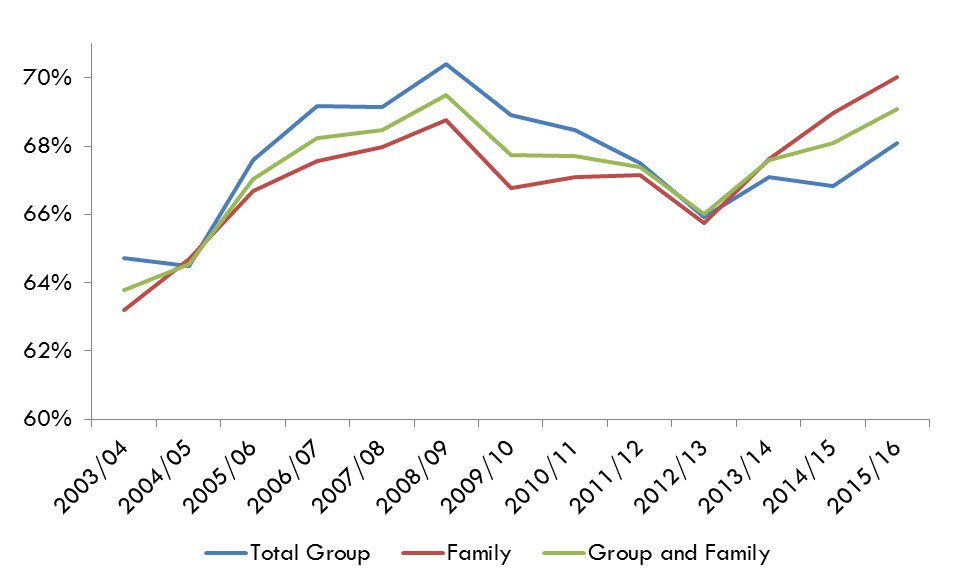

It’s worth noting the term “vacancy” is not used. Instead, the Ministry of Children and Family Development presents the data in the form of “utilization rates”—the percentage of spaces used, rather than the percentage vacant. Utilization rates going back to 2003 are shown in Chart A, which is reproduced from the ministry’s report.

Chart A: Trend in Child Care Space Utilization Rates by Type of Providers, Monthly Average, 2003/04 to 2015/16

*Source: Ministry of Children and Family Development. Performance Management Report. Volume 8, March 2016, p. 15. This is taken directly from the report. Note that the utilization rates have varied over the years, but have not surpassed about 70 percent. This means at their lowest, vacancy rates were 30 percent.

Instead of utilization rates, we present vacancy rates in Chart B below by subtracting the utilization rate from 100 percent (utilized spaces + vacant spaces = 100%). The vacancy rates are actually higher because available spaces in “licence not required” home daycare and “licensed” preschool (which may provide up to four hours of care per day) are not included in the data. 5 5 “Licensed ‘preschool’ child care spaces have been excluded from these calculations as preschool facilities may be open on a part-time basis both with morning and/or afternoon sessions, and from one to five days per week,” Ibid., 14

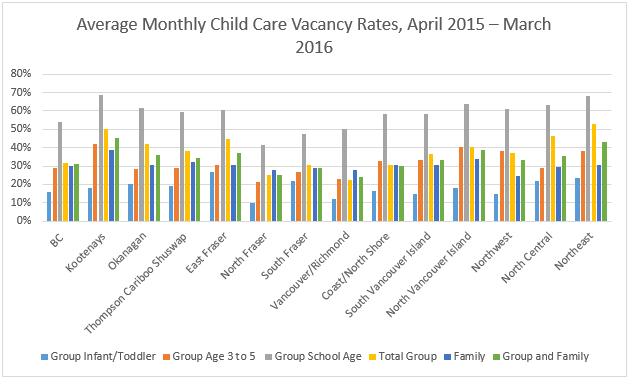

Vacancies by Geography

The province is divided into thirteen service delivery areas (SDAs). 6 6 Please check page two of the Performance Management Report to see what part of the province each service delivery area includes. Vacancy rates across those SDAs vary. The highest vacancies are in the northeast (42.9%) and the Kootenays (45.1%). 7 7 Calculations based on “Group and Family” utilization rate. Ibid., 17. Put bluntly, in the Kootenays, almost half of daycare spaces are vacant.

The lowest vacancy rates are in Vancouver/Richmond at 24 percent. To emphasize the point, that means that in the area with the highest child care utilization rates, roughly a quarter of spaces are still available.

The next lowest vacancy rates are North Fraser and South Fraser at 25.2 percent and 28.7 percent respectively.

The report discusses the varying vacancy rates by community size, as well. Larger communities, such as Vancouver/Richmond, have lower vacancy rates. In communities with fewer than 10,000 people, vacancy rates are high across the board, at an average of 43.2 percent. 8 8 Ibid., 19.

Chart B: Average Monthly Child Care Vacancy Rates, April 2015 - March 2016

*Source: Ministry of Children and Family Development. Performance Management Report. Volume 8, March 2016, p. 17. The document shows utilization rates by service delivery area across the province, which we have converted here into vacancy rates.

9 9 Community Care and Assisted Living Act, Child Care Licensing Regulation. November 8, 2007. http://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/loo96/loo96/332_2007#section2Vacancies by Age Group

Infants/Toddlers

In British Columbia, the age range with the lowest vacancy rate is the infant/toddler group, which includes children under thirty-six months of age. The average vacancy rate for these children is 16.1 percent. One of the lowest vacancy rates is found in North Fraser at 10.1 percent. This is followed closely by Vancouver/Richmond where the vacancy rate is 11.8 percent. South Vancouver Island has a vacancy rate of 14.5 percent. South Fraser has a much different vacancy rate than North Fraser at 22.1 percent. 10 10 Calculations based on Performance Management Report, 17.

Children Aged Three to Five

Nowhere do “utilization rates” ever reach 100 percent, least of all for children aged three to five. The authors of the Performance Management Report discuss decreasing utilization for this age group: “With the growth in group Age three to five child care spaces typically surpassing growth in enrollments, the group Age three to five utilization rate has a decreasing trend since 2007/2008.” 11 11 Ibid.

For children aged three to five in British Columbia, the average vacancy rate across the province is 28.7 percent. Across the province’s SDAs, the vacancy rates range from 21.5 percent in North Fraser to 42.2 percent in the Kootenays for children aged three to five.

School-Aged Children

The vacancy rates for school-aged children are the highest, ranging from 41.5 percent in North Fraser to 68.6 percent in the Kootenays.

Vacancies by Daycare Size

A final point about daycare usage: The report indicates parents do not choose large daycares with many spaces. Since 2003, the highest vacancy rates exist in centre-based group facilities with forty or more spaces. The lowest vacancy rates in daycare centres exist in those with ten or fewer spaces. 12 12 Ibid., 20. Family-based daycare has lower vacancies overall despite higher fee subsidies for centre-based care. 13 13 https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/family-and-social-supports/child-care/subsidy_rate_table.pdf.

In fact, we know that centre-based care (the type most often proposed by governments aiming to create spaces) is the least popular with parents. The first preference for child care is for children under six to be at home with a parent; however, if that is not possible, the next choice is a relative, then a neighbourhood home daycare. 14 14 “Canadian Daycare Desires,” Institute of Marriage and Family Canada, May 2013, 3. https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/articles/canadian-daycare-desires/. This result holds true going back to 2005 when Reg Bibby, in conjunction with the Vanier Institute, surveyed on the same topic. “Child Care Aspirations,” Vanier Institute of the Family, February 2005. http://www.reginaldbibby.com/images/ChildCareAspirations_Feb1005.pdf.

The report highlights how centre-based care does have vacancies. Excluding preschool spaces, the authors write, “From April to September 2015, approximately 770 Group facilities had 40 or more spaces, 1,060 Group facilities had between 11 and 39 spaces, and 340 Group facilities had 10 or fewer spaces.” 15 15 Performance Management Report, 20.

Subsidy Surplus

Looking at these vacancy rates, some would argue there are plenty who want to find a daycare space, but they simply do not have the money with which to do so. Here we turn to examine budgeted subsidy dollars in British Columbia. The amount budgeted for child care fee subsidies in 2016/2017 was $119 million. The amount used was $105 million in the same year. 16 16 Dayna Slusar, Cardus researcher, in phone communication with Kelly Douglas from the British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development, November 28, 2017. This amounts to $14 million in unused, but budgeted subsidy dollars.

Why do We Hear so Much About the Stress of Finding Care?

Like many aspects of child-rearing, finding high quality, non-parental child care that suits a family’s situation can be stressful. However, given these data, it is clear that vacancies exist across the province. At the same time as there are vacancies, there are advocacy groups working hard toward increasing funding for non-parental child care. In the last provincial election, held in May 2017, the New Democratic Party ran on a campaign of $10-a-day daycare and the creation of thousands more daycare spaces, alongside the hiring of more early childhood educators. The Green Party promised free non-parental child care as well as $500 per month for parental child care. 17 17 “Free Child Care and Preschool,” Greens of British Columbia. http://www.bcgreens.ca/childcare. This has far more to do with ideology than need; there are many who believe the creation of publicly funded and run daycare is the only way to offer child care.

It is not our intent to say that no parent has problems with finding suitable non-parental child care across British Columbia. Problems are likely for those seeking infant care in densely populated areas, for example. Finding high quality care for any age range, given that the quality of care in the majority of licensed daycares in Canada has been found to be inadequate, could likewise be a problem. 18 18 “Instead, the majority of the centres in Canada are providing care that is of minimal to mediocre quality,” Gillian Doherty, Donna Lero, Hillel Goelman, Annette LaGrange, and Jocelyne Tougas, “You Bet I Care! Caring and Learning Environments: Quality in Child Care Centres Across Canada,” Centre for Families, Work and Well-Being, University of Guelph, 2000, ix. https://www.worklifecanada.ca/cms/resources/files/4/ybic_report_2_en.pdf. That said, the idea of an outright shortage is demonstrably false when looking at the evidence for every part of the province. There are other relevant policy options.

Suppressed Evidence

Evidence of daycare vacancies has been documented since at least 2000. A federally funded report written by some of Canada’s leading proponents of institutional daycare found that only 46.3 percent of daycare centres Canada-wide reported no vacancies, and 30.6 percent reported vacancy rates over 10 percent in 1998. The authors write: “A comparison of the number of centres with all spaces filled in 1991 (37.5%) and in 1998 (46.3%) suggests that maintaining enrollment is less of a problem than it was.” They then bluntly note, “Vacancy rates of this magnitude make it extremely difficult to sustain financial viability.” 19 19 Ibid., 167, http://www.ccsc-cssge.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/Projects-Pubs-Docs/ybic_report.pdf.

The City of Toronto’s child care website used to provide current data on vacancies in each centre it funds, but removed these data at some point after 2009. In 2015, “Is There Really a Daycare Shortage?” revealed that between 2009 and October 2014, the daycare vacancy rate in Toronto fluctuated from a low of 3.58 percent to a high of 6.64 percent. 20 20 Ward, 7.

Policy Suggestions

A better approach to child care would broaden its definition to include parents. Child care is the care of a child, regardless of how or where that care takes place. Governments should direct child care funding directly to parents, rather than building more spaces where they are not needed.

Funding for parents should be based on income. Higher-income families are more likely to use daycare centres than lower-income families, according to Statistics Canada. This is why higher-income families receive more child care funding. “In general, parents belonging to a higher income household were more likely to have used some form of non-parental care. More precisely, about two-thirds (65%) of parents with an annual household income of at least $100,000 used child care for their preschooler. This was nearly double the rate recorded for households with an income below $40,000 (34%),” writes the author of the Statistics Canada report. 21 21 Maire Sinha, “Child Care in Canada,” Ottawa: Statistics Canada, October 30, 2014, 6. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2014005-eng.pdf.

Thus, preferential funding for centre-based care discriminates against those who cannot or prefer not to use that form of care and creates an incentive for parents to use the subsidized care. It is important to note that only 18 percent of children aged zero to four are in daycare centres or preschools, according to Statistics Canada. 22 22 Calculations by authors based on data from Sinha, Table 1, 7. The calculation of the 18 percent is based on all children including those who are in parental care. According to the Sinha report, 54 percent of parents with children aged four and under used regulated child care (4). Sinha’s Table 1, 7 says 33 percent of children aged four and under whose parents use child care are in a daycare centre. Government must remain neutral in its approach to funding child care options.

Parents never pay the actual full costs for daycare, which are far higher than the fees, because all care in daycare centres and preschools is subsidized. The government provides funding for various operational and capital costs. Some facilities have additional subsidies, too. 23 23 Performance Management Report, 22. This shows $210.029 million total expenditure subsidizing non-parental child care; the fee subsidy portion is only about half of the total at $109.037 million. For example, the University of British Columbia provides rent-free premises and covers all janitorial and administrative costs at UBC daycare centres.

On top of these direct system subsidies are fee subsidies for lower-income families and tax deductions available for higher-income families for non-parental child care. In B.C., fee subsidies are much lower for care in the child’s own home—as low as $147 per month for a third child than for daycare centres, which can be as high as $750 per month. 24 24 Child Care Subsidy Rate Table. Effective April 1, 2012. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/family-and-social-supports/child-care/subsidy_rate_table.pdf.

The federal child care expense deduction of $8,000 per child aged zero to seven and $5,000 for a child up to age fifteen also lowers parents’ costs. This provides up to over $3,500 per child in public funding to parents with higher taxable incomes. 25 25 Jaime Golombek, “Why 2017 May Prove to be a Taxing Year if You’ve Got Kids,” Financial Post, January 6, 2017. http://business.financialpost.com/personal-finance/taxes/why-2017-may-be-a-taxing-year-if-youve-got-kids. and Child Care Expense Deduction 2016 form, Canada Revenue Agency https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/cra-arc/migration/cra-arc/E/pbg/tf/t778/t778-16e.pdf.

Currently, the discrepancy in how we fund child care in Canada is great. By funding spaces rather than children, the vast majority of children and families receive no child care funding. Public funding per daycare space is over five times greater than the child care funding per child in Canada: $436 per child vs. $2,775 per regulated space (outside Quebec). 26 26 For more detail on how child care funding works, please see Ward, 5-8.https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/articles/is-there-really-a-daycare-shortage/.

Overturning this discriminatory discrepancy requires a look at the evidence and the desire to serve all parents and children, regardless of the forms of care they use.