Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Introduction

If Presbyterian clergyman and children’s television innovator Fred Rogers was correct that “childhood lies at the very heart of who we are and who we will become,” 1 1 F. Rogers as quoted by “The Messages,” Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood (blog), accessed September 24, 2019, https://www.misterrogers.org/the-messages/. then the problem of childhood is that so little serious attention is paid to it. Children are unique from adults. Yet, when children are invited into the adult world, they are often burdened with adult concerns, and treated as adults-on-the-way. Too often there is disruption within the organic social structures they rely on. The Christian tradition possesses the tools to aid the Christian community in asking the right questions regarding the cultivation of a healthy participation of children in public life.

Children have always lived in an adult world, with their fate held in the hands of grown-ups. At times, children have been treated as silly and irrational, no better than slaves. In other moments, children have been considered with almost angelic otherness. No doubt the status of children has improved in modern life, with attention paid not only to their developmental needs but also to their rights. Still, most of modern life operates as an adult sphere, where children are accommodated and provided spaces designed and directed by adults. Even in a society that is more attentive to children’s rights, author Sarah Dahl argues there is a deep ambivalence toward children. 2 2 S. Dahl, “Selling Our Birthright for a Quiet Pew,” Comment, April 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/comment/article/selling-our-birthright-for-a-quiet-pew/.

Children’s vulnerability leaves them susceptible not only to the obvious cruelties of the grown-up world, but the adult-centred orientation of life means children are always slightly askew in the world. Our most basic social institutions, marriage and family, are far less centred on the needs of children than in the past, and are increasingly stretched and reconfigured to meet the romantic desires of adults.

The emergence of the children’s-rights movement, as demonstrated in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, recognizes the powerlessness of children in an adult world but also codifies notions of autonomy that estrange children from natural relationships that should nurture and protect them. Despite an emphasis on the best interests of children, autonomy as conceived in children’s-rights language has positioned children in direct tension with the natural communities and institutions that best serve and protect their interests. Vigen Guroian, retired professor of theology most recently at the University of Virginia, observes, “To the extent that these notions of individualism and autonomy influence contemporary thought on childhood, there is a tendency to define childhood apart from serious reflection on the meaning of parenthood. Yet a moment’s pause might lead one to recognize that there is hardly a deeper characteristic of human life than the parent-child relationship.” 3 3 V. Guroian, “The Ecclesial Family: John Chrysostom on Parenthood and Children,” in The Child in Christian Thought, ed. Marcia J. Bunge (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 61.

Christian community is not immune to the influences of individualism and autonomy. Guroian devotes equal criticism to the church, writing, “The Christian faith would have us look more closely at the fundamental parent-child nexus. Yet in the churches far too little discussion is given over to the vocation of parenthood and the child’s obligations to parents. Instead, churches ape the culture’s obsessive interest in individual psychology and . . . personal autonomy.” 4 4 Guroian, “Ecclesial Family,” 62. Author Jerome Berryman argues that Christian community is prone to the same ambivalence in dominant culture that accounts for “the church’s delight and aversion, attraction and repulsion, and emotional closeness to and distance from children.” 5 5 J. Berryman as quoted in Dahl, “Selling Our Birthright.”

Scholars often point out that theology has not focused pointedly on children. But the Christian intellectual tradition has not ignored children either. Historically Christian community has advocated for and ministered to children. Contemporary Christian community should poke and prod the assumptions about children evident in dominant culture and often “aped” in communities of faith. Christian community faces a distinct challenge not only in how we think and speak about children but also in how we include children in public life. As Dahl reminds us, children are our brothers and sisters in Christ, and fellow “sojourners on the Way.” 6 6 Dahl, “Selling Our Birthright.”

In this paper we survey the child in Christian thought to contribute to foundational thinking that will further our consideration of the treatment of children in North American public policy. In part 1, we briefly examine how children are presented in Scripture, focusing on the nature of childhood, children in the family, and children in the community. In part 2, we provide a historical overview of the shifting treatment of childhood in the Christian tradition from the early church to the twentieth century, focusing on the nature of childhood and the relationship between children, their families, and their communities. In part 3 we explore the renewal of contemporary interest in children through the emergence of the child-theology movement, and themes from research projects at the University of Chicago and Emory University. These projects consider the implications of the Christian tradition for law and policy concerning children. In part 4, we consider entry points for further discussion between Christian thought and contemporary theories that inform children’s rights and advocacy for greater personal autonomy for children.

Our intent for this paper is to inform our understanding of the Christian tradition, identify sources for further study and reflection, and raise questions regarding our engagement with issues concerning children in public life. We acknowledge that this paper is a broad survey of themes and that space limits our engagement with a rich and diverse history of thinkers and traditions within the Christian faith.

Children in Scripture

Contemporary scholars share a near consensus that serious, scholarly theological work has paid little attention to children and childhood. Historically, theologians have addressed children within the context of household relationships and responsibilities but have left childhood largely unexplored. Scripture, however, has much to say about children. In this section we survey general themes within Scripture, focusing on the nature of childhood, children in families, and children in communities. Further exploration of children within the life of biblical communities would provide valuable insight for our work at Cardus.

The Nature of Childhood

The concept of childhood has varied across geographic and historical contexts, including within Scripture. 7 7 N. Steinberg, The World of the Child in the Hebrew Bible (Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2013), xi, xxiii. Characteristics such as gender and birth order significantly influenced how children were viewed and treated. Nevertheless, a coherent and complex, positive understanding of children emerges from Scripture.

Essential to understanding the nature of children in Scripture is the proposition that children are created in the image of God and therefore have full dignity and value. The Jewish tradition within Scripture presents children as a divine gift and evidence of God’s blessing. 8 8 J.M. Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest: Children in the New Testament,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 35. Furthermore, children are an affirmation of God’s command to fill and subdue the earth. 9 9 A.J. Köstenberger and D.W. Jones, God, Marriage, and Family: Rebuilding the Biblical Foundation, 2nd ed. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010).

Yale scholar Judith Gundry-Volf argues that the Jewish tradition presented in the Old Testament valued children without romanticizing childhood. The Old Testament frequently speaks of blessing passed down from generation to generation, with particular attention to the firstborn male.

The Gospels begin with the incarnation of Jesus as a baby. Church of England vicar W.A. Strange notes, “If the incarnate Christ had assumed the experience of childhood . . . then childhood itself took on dignity and importance.” 10 10 W.A. Strange, Children in the Early Church: Children in the Ancient World, the New Testament and the Early Church (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2004), 46. One might argue that the incarnation confirmed the dignity previously bestowed on children as image bearers. Yet the larger point is that Christians can draw significance from Christ coming as a child. Irenaeus argued that in becoming a child, Christ sanctified children as he did people at each life stage. 11 11 Irenaeus, Against Heresies 2.22, in Ante-Nicene Fathers, ed. A. Roberts, J. Donaldson, and A.C. Coxe, trans. A. Roberts and W. Rambaut, vol. 1 (Buffalo: Christian Literature Publishing, 1885), http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0103222.htm. Jesus himself displayed the inherent dignity and value of children through his teaching and interactions with children in the Gospels.

Gundry-Volf points out that this dignity and value are present in Christ’s treatment of children as an example of the proper posture before God. Jesus beholds children as a model for entry into the reign of God. Adults are called to adopt a childlike status and “presumed childlike quality.” 12 12 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 39. This posture embodies humility and dependence on God.

Gundry-Volf reflects on Matthew 21, when children call out in praise as Jesus enters Jerusalem. Faced with criticism, Jesus declares that the Lord called forth their praise. The children recognize Jesus as Messiah, in contrast to the religious leaders. Gundry-Volf connects this passage with Luke 10:21, where Jesus states that God reveals hidden truth to children. She concludes that little children are capable of authentic belief and that God can choose to reveal his truth to them. 13 13 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 48.

The Epistles frequently engage childhood as a symbol of developing spiritual maturity. The recipients of the Epistles are often endearingly referred to as children. Although childhood is utilized as a symbol of maturing faith, the Epistles are clear that children are no less capable of knowing God (see 1 John 2).

Children in Families

Families were viewed as a central actor in the preservation and transmission of the faith. Parents were responsible for instructing children in the way of the Lord, and in return, children were to obey and honour parents.

The parent-child relationship was bound to the larger understanding of children in the community. As a sign of God’s blessing, children were part of the fulfillment of God’s covenant with Abraham. Pragmatically, children were essential to the economic well-being and survival of families. 14 14 Strange, Children in the Early Church, 9–19; Köstenberger and Jones, God, Marriage, and Family. The responsibility for children was more than economically motivated. The instruction of children in the faith within the family ensured that the faith and tradition remained embedded within the community.

Professor Joseph Atkinson argues that the family served an “active and critical role in the passing on of the covenant from generation to generation.” 15 15 J.C. Atkinson, “The Family: The Church in Miniature,” Catechetical Review 2, no. 3 (September 2016): 14–28, https://review.catechetics.com/family-church-miniature. Abraham admonished his children and household to keep the way of the Lord.

Reflecting on child-rearing in the Jewish community in the first century, Gundry-Volf states, “Indeed, Jews distinguished themselves from many of their contemporaries by rejecting brutal practices toward children, including abortion and the exposure of newborns, which can be traced to less positive views of children, and by placing limits on the Jewish father’s power over his children.” 16 16 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 35–36.

The Epistles address the obligations of children and parents within the family. The family codes in Colossians and Ephesians instruct children to obey their parents, referencing the Hebrew Scriptures (see Ephesians 6:1–4; Colossians 3:20–21). Fathers are to refrain from provoking children to anger and instead are to instruct and disciple children.

Theologians note that the relationship between father, mother, and child reflects the trinitarian relationship within the Godhead. The fourth-century church father St. John Chrysostom grounded his understanding of the family in trinitarian thinking. He pointed to the reciprocal relationship of love between the members of the Trinity as an example for parents and children to emulate. Summarizing Chrysostom, Guroian writes, “Together, through love, parents and children participate in the triune Life of God.” 17 17 Guroian, “The Ecclesial Family,” 64. American theologian Bruce Ware likewise writes, “The Trinity provides us with a model in which we understand the members of a family as fully equal in their value and dignity as human beings made in God’s image.” 18 18 B.A. Ware, “The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit: The Trinity as Theological Foundation for Family Ministry,” Journal of Discipleship and Family Ministry 1, no. 2 (Spring 2011): https://www.sbts.edu/family/2011/10/10/the-father-the-son-and-the-holy-spirit-the-trinity-as-theological-foundation-for-family-ministry/.

Children in Communities

The family in Scripture was essential to the function of community. Scripture speaks to the place of children in the family and community.

Jesus’s treatment of children in the Gospels is instructive in understanding the relationship between children and the community in the kingdom of God.

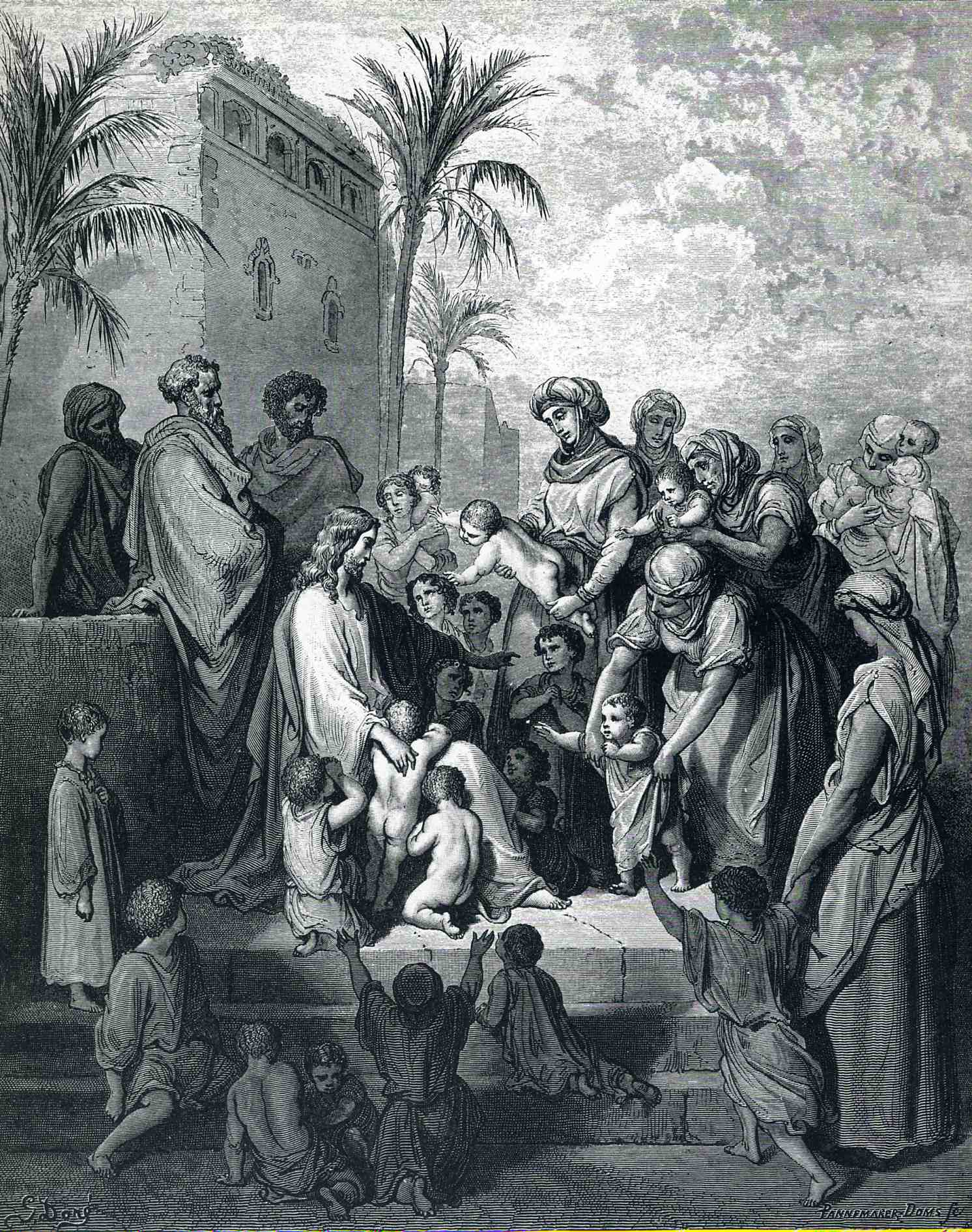

Gundry-Volf highlights Matthew 19, in which Jesus blesses children and announces that the reign of God belongs to them. 19 19 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 38. Jesus’s inclusion of children stands in contrast to the disciples’ attempt to dissuade people from bringing their children to the Master. Not only are children welcomed, Jesus elevates the status of children, declaring that the reign (or kingdom) of God is for them.

Treating children with dignity is an act of service to God. Specifically, welcoming children as Jesus did in Mark 9 is akin to welcoming Christ. Gundry-Volf states, “Welcoming children thus has ultimate significance. It is a way of receiving and serving Jesus and thus also the God who sent him.” 20 20 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 44. She boldly argues that rejecting children is a rejection of Jesus and that the vulnerability of children reflects “Jesus as a humble, suffering figure.” 21 21 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 44. She grounds this claim in the context of the practices of the Greco-Roman period that frequently mistreated children. In this context, welcoming children affirms Christ’s mission as the suffering Son of God, although this is not explicit in Christ’s teaching. 22 22 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 45.

From the same passage of Scripture, Gundry-Volf notes that to welcome (in Greek, dechomai) children implies hospitality and service. 23 23 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 43. The humble posture of serving children is the mark of greatness. She argues that Christ’s act of welcoming children places them at the centre of the community’s attention. By implication, Jesus’s welcoming children structures social practices that form and strengthen faith in Christ. 24 24 Gundry-Volf, “The Least and the Greatest,” 46.

In summary, children are recognized in Scripture as image bearers of God with full human value and dignity. They are gifts from God, a sign of his blessing, and welcomed into families and community. The vulnerable status of children and the need for direction and protection is consistent throughout Scripture. Jesus welcomed children as participants in his reign and as examples of spiritual humility for adults to emulate. Children are participants in the community of faith, to whom God also reveals himself. Serving children is faith-forming service to God. This service also occurs in the context of family, where children are called to obey parents who discipline, teach, and protect them. This intra-family relation has positive implications for the common good within society as a whole.

Children in the Christian Tradition

In this section we provide a brief, general survey of children and childhood in the Christian tradition. We have chosen to organize the material by historical period, structuring each period according to three organizing themes: the nature of childhood, children in families, and children in society.

The nature of childhood concerns questions of theological anthropology and the understanding of spiritual development within the Christian tradition. We then examine the child within the family, recognizing that family is the first (spiritual) community, with profound responsibilities for the development of children. Family has both private and public responsibilities and contributions to childhood. Finally, we consider the implications of Christian thought for children as participating members in society. We use the term “society” to include children’s relationships with formal and informal social institutions, the church, and the state.

Early Christianity and the Church Fathers

The Nature of Childhood

Children were held in low esteem in Greco-Roman culture. They lacked the ability to reason, a necessary faculty for the virtuous life. Church historian O.M. Bakke writes that children were perceived as “malleable” and “requiring cultivation.” 25 25 O.M. Bakke, When Children Became People: The Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity, trans. B. McNeil (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2005), 20. This perception of childhood permitted physical discipline in the absence of the ability to reason. Considered foolish and irrational, children occupied similar social standing as slaves and barbarians within the dominant culture. Their susceptibility to disease and death only confirmed their weak physical stature and low social standing. 26 26 Bakke, When Children Became People, 18.

While children had low social standing in Greco-Roman culture, they were not without value. Prosperous families understood that the legacy of wealth and reputation continued through the next generation. For lower-status families, children were an economic resource and future means of support.

The Christian community may have adopted some cultural practices of the surrounding culture, including authority structures within the family. Early Christian teaching, however, stood in stark contrast to the dominant culture. Compared to their neighbours, Christians showed greater involvement in and attentiveness to the upbringing of children. 27 27 N. R. Pearcey, Love Thy Body: Answering Hard Questions About Life and Sexuality (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2018), 106. Author Nancy Pearcey argues that “Christianity invented a novel concept of childhood, a new mindset that regarded children as persons to be valued, cherished and cared for.” 28 28 Pearcey, Love Thy Body, 106. Bakke cautions that children’s voices are less present in historical study, but he concludes, “Christianity introduced new anthropological viewpoints, a new ethical evaluation and new ideas for upbringing. All of this had effects on the societal life of children.” 29 29 Bakke, When Children Became People, 286. What shaped this anthropological viewpoint within a culture that marginalized children?

The church fathers did not devote specific attention to childhood outside of baptism and the nature of sin; however, they did contemplate Jesus’s elevation of children as an example for adults to emulate, 30 30 Pearcey, Love Thy Body, 105. viewing young children as reflections of moral simplicity, innocence, and purity. 31 31 Bakke, When Children Became People, 104. There was some divergence on the exact nature of children and sin. Eastern church fathers such as Origen, John Chrysostom, and Clement of Alexandria ascribed this sense of purity to children’s lack of temptation toward sexual sin and lower susceptibility to grief, anger, and greed. This perspective is also evident among Western thinkers like Tertullian. For Clement and Origen, the development of the ability to reason in a child corresponded with the loss of innocence, but reason is required to overcome passions.

In general, the early church fathers treated infants as morally neutral. In the fifth century, however, the Western church broke from this position. Bakke writes, “Although Eastern theologians agreed with the Western tradition, which emphasized that Adam’s sin had consequences for his posterity, and some even came close to affirming, or at least implicitly presupposing the idea of original sin, this was asserted with much greater vigor by Augustine.” 32 32 Bakke, When Children Became People, 105.

Augustine introduced a shift in thinking about the nature of children and sin. Augsburg University professor Martha Ellen Stortz argues that Augustine believed infants were neither innately innocent nor innately depraved but rather summarizes Augustine’s position on the sin nature of infants as a non-harming non-innocence. 33 33 M.E. Stortz, “Whither Childhood? Conversations on Moral Accountability with St. Augustine,” Journal of Lutheran Ethics 4, no. 1 (2004): https://www.elca.org/JLE/Articles/799. Infants experience passions such as jealousy, but they do not possess the physical ability to act on impulses. Augustine advocated for a progressive accountability as children developed through adolescence into adulthood. 34 34 Stortz, “Whither Childhood?”

Common among the church fathers was the sense that educating children was oriented toward developing a foundation for a virtuous life. Describing the influence of Gregory of Nyssa on patristic teaching about children, Bakke writes, “The child shares in God’s life and that the goal of education is to sow the virtues in the child, so that its soul will be cleansed of the consequences of the fall, and it can truly achieve that degree of sharing in God for which it was created.” 35 35 Bakke, When Children Became People, 108.

Children in Families

Chrysostom believed that passions were present before reason in young children. 36 36 Bakke, When Children Became People, 105. Chrysostom also believed that children should be guided and shaped but that they possessed full human status as image bearers of God. He implored parents to engage in their vocation of revealing the image of God in their children. 37 37 Guroian, “The Ecclesial Family,” 69. In this way, the family existed as a little church. Guroian argues that Chrysostom believed parents held an ecclesial office that is soteriological in nature. A child’s inheritance of the kingdom of God largely depends on the care and duty of parents. 38 38 Guroian, “The Ecclesial Family,” 69. It follows that the neglect of this obligation by parents is a grave injustice. 39 39 Guroian, “The Ecclesial Family,” 72.

Children in Society

Children in Greco-Roman culture were excluded from public life and served as a “negative counterfoil to the free male urban citizen.” 40 40 Bakke, When Children Became People, 20–21. Bakke reports that his studies find no evidence that the culture viewed the suffering of young children as problematic. Consistent with a Stoic view of grief, Cicero and Seneca criticized fathers who grieved the death of young children. 41 41 Bakke, When Children Became People, 108. The culture surrounding the early church tolerated abortion, infanticide, and exposure—the practice of abandoning unwanted infants.

The early Christian community continued the Jewish opposition to these established practices. Bakke argues that opposition to abortion, infanticide, and exposure were primarily grounded in two fundamental beliefs. As noted above, children were understood to be fully human image bearers of God and were not to be killed. The second underlying belief for the protection of children was the commandment to love one’s neighbour. 42 42 Bakke, When Children Became People, 149. Clement, Justin Martyr, and Lactantius strongly opposed these practices but did not ground their opposition in creation theology.

It should be acknowledged that some pagan perspectives also opposed exposure for pragmatic, non-moral reasons. Yet the eventual legal prohibitions against these practices were influenced in part by the Christian anthropological perspective on children. 43 43 Pearcey, Love Thy Body, 105.

Another contributing factor to the unique treatment of children in Christian community may have been the equally unique status of women in the early church. Sociologist Rodney Stark points out that women were overrepresented in the church compared to the general population, which may have contributed to their improved status in the faith community. Additionally, the teaching of the apostles encouraged respect for women compared to pagan culture. One quantifiable result was that there were much lower rates of child marriage in the Christian community. 44 44 R. Stark, “Reconstructing the Rise of Christianity: The Role of Women,” Sociology of Religion 56, no. 3 (1995): 229–44.

In summary, the treatment of children in the early church and evidence in the writings of the church fathers stand in contrast to the Greco-Roman world. Christian communities recognized that children are created in the image of God and possess full human value. The church fathers debated the nature of sin in children and the importance of developing virtue in children as they grow to maturity. The Christian family was responsible for developing faith and virtue in children, as articulated by John Chrysostom. Early Christian opposition to abortion, infanticide, and exposure eventually had some influence in curbing the mistreatment of children.

The Middle Ages

The Nature of Childhood

Children were not a prominent topic of theological consideration in the Middle Ages. Some contemporary scholars state that many medieval thinkers spent little time with children, contributing to the absence of focused study on the young. 45 45 N. Orme, “Children and the Church in Medieval England,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 45, no. 4 (October 1994): 563; J. W. Berryman, Children and the Theologians: Clearing the Way for Grace (Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse, 2009), 64; C.L.H. Traina, “A Person in the Making: Thomas Aquinas on Children and Childhood,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 116. An additional challenge is the dearth of available sources from the period on the topic. Yet even with these challenges, it is possible to identify key themes.

Philosophical debates over the nature of human beings, particularly about the nature of sin, loomed large in the few theological discussions of childhood. 46 46 J.M. Ferraro, “Childhood in Medieval and Early Modern Times,” in The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World, ed. P.S. Fass, Routledge Histories (London: Routledge, 2013), 72. Augustine’s emphasis on original sin greatly influenced medieval thought. Children were understood to have been born into sin and driven by unrestrained, misdirected desires. 47 47 M.J. Bunge and J. Wall, “Christianity,” in Children and Childhood in World Religions: Primary Sources and Texts, ed. M.J. Bunge and D.S. Browning, Rutgers Series in Childhood Studies (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2009), 89; Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 106. This pessimistic view was moderated by Thomas Aquinas, the dominant philosopher and theologian of the Middle Ages. Aquinas drew heavily from Augustinian theology but incorporated more optimistic ideas about human nature from Aristotle, whose writings were at the time enjoying a resurgence in the West. Aristotle had emphasized children’s innate moral and rational potential, viewing children not as evil but simply as immature, with an undeveloped capacity for reason. 48 48 Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 106; Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 89. Aquinas held these two opposing perspectives in tension. While affirming the doctrine of original sin, he emphasized that the role of divine grace in a child’s development was to complete rather than to correct nature. Children’s physical and rational immaturity left them with a sense of incompleteness that distinguished them from adults, but this was a natural stage that would be outgrown. 49 49 Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 106–11; Reynolds, “Thomas Aquinas and the Paradigms of Childhood,” 162–68, 183. Clerics encouraged parents to discipline their children appropriately so as to prevent them from developing bad habits. Children were to be directed toward virtue as they matured. 50 50 V.L. Garver, “The Influence of Monastic Ideals upon Carolingian Conceptions of Childhood,” in Childhood in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, ed. Albrecht Classen (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2005), 70, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110895445.67.

Thinkers in the Middle Ages commonly divided childhood into seven-year periods. The first period, infancy, encompassed birth to age seven and was characterized by the absence of reason. 51 51 Reynolds, “Thomas Aquinas and the Paradigms of Childhood”; Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 126; see also Bunge and Wall, “Christianity,” 114. Although children’s reasoning capacity was still deficient after the first stage, a child possessed sufficient reason to be held accountable for behaviour, including mortal sins. 52 52 S. Ozment, When Fathers Ruled: Family Life in Reformation Europe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009), 144. Pueritia, the period from ages eight to fourteen, was considered proper childhood. As children entered puberty, they were considered to possess sufficient capacity for reason and were granted more responsibility for their own decisions. 53 53 Reynolds, “Thomas Aquinas and the Paradigms of Childhood”; Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 126; see also Bunge and Wall, “Christianity,” 114. Puberty marked the transition into legal-majority status. They could enter binding commitments such as marriage or holy orders. 54 54 J.L. Nelson, “Parents, Children, and the Church in the Earlier Middle Ages (Presidential Address),” in The Church and Childhood, ed. D. Wood, Studies in Church History 31 (Oxford: Ecclesiastical History Society, 1994), 86–87; Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 126; Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 114; Reynolds, “Thomas Aquinas and the Paradigms of Childhood,” 177. The child in medieval Christian thought gained increased responsibility and autonomy with the growing capacity to reason.

Children in Families

A tension existed within the medieval family between viewing children as possessions and acknowledging their status as independent subjects. 55 55 Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 109. On the one hand, young children effectively belonged to their families. Adults leveraged children to forge and maintain relationships to advance family interests. Children were given away through marriage or in oblation to monasteries or convents. 56 56 Garver, “Influence of Monastic Ideals,” 71; Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 107. Children were expected to submit obediently to the authority of their parents, especially their fathers. Mothers held primary responsibility for children under the age of seven. 57 57 H. Cunningham, Children and Childhood in Western Society Since 1500, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2005); Nelson, “Parents, Children, and the Church”; Traina, “A Person in the Making.”

Christian parents in the Middle Ages were expected to love and provide for their own children. 58 58 C.J. Reid, Jr., Power Over the Body, Equality in the Family: Rights and Domestic Relations in Medieval Canon Law (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 93. Drawing from the Aristotelian understanding of rightly ordered family relationships, Aquinas argued that adults had responsibilities to their dependent offspring, derived from natural law. The strong love between children and their parents, Aquinas explained, is natural and rational since they are of the same substance. 59 59 Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 121. Parents and children have unique obligations to each other. These obligations are inherent in familial relationships and cannot be fulfilled by other relationships. 60 60 D.H. Jensen, “Adopted into the Family: Toward a Theology of Parenting,” Journal of Childhood and Religion 1, no. 2 (2010): 5, http://childhoodandreligion.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/JensenApril2010.pdf. M. Moschella, To Whom Do Children Belong? Parental Rights, Civic Education, and Children’s Autonomy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 21–48. Parental responsibilities extend beyond the provision of material needs and include education and instruction in the faith. 61 61 Orme, “Children and the Church in Medieval England,” 564; Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 121; Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 118–19. The responsibilities of children as pre-rational beings were absolute dependence and submission. Significantly, Aquinas insisted that children’s dependence required parents to remain bound to one another in lifelong, monogamous marriage. 62 62 Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (Crownhill, UK: Authentic Media, 2012), II-II.154.2.

Despite the possessive view of children within families, by the end of the twelfth century a growing emphasis was placed on personal spiritual development and individual conscience. Aquinas argued that children could reject their parents’ wishes for them concerning marriage or joining holy orders once they reached puberty. Parents were urged to rely on sound arguments rather than raw authority to persuade young people. 63 63 Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 107–8. While medieval children were denied access to some sacraments such as the Eucharist and extreme unction, they gained greater autonomy over their lives, particularly concerning binding commitments such as marriage and holy orders. 64 64 Orme, “Children and the Church in Medieval England,” 572–75; Reynolds, “Thomas Aquinas and the Paradigms of Childhood,” 177. The practice of child oblation was likewise rejected after the twelfth century, as it was incompatible with the church’s growing insistence on personal spiritual understanding. 65 65 Nelson, “Parents, Children, and the Church,” 111–12; M. de Jong, In Samuel’s Image: Child Oblation in the Early Medieval West (Leiden: Brill, 1996), 1–15. Children assumed greater responsibility and autonomy after puberty. 66 66 Nelson, “Parents, Children, and the Church,” 87.

Children in Society

Aquinas argued that parents’ position as the primary authority over children was evident through natural justice. 67 67 The language of children’s “belonging” to certain adults and/or communities is drawn from Moschella, To Whom Do Children Belong? The scope of parental authority included determining how a child would be raised. Notably, Aquinas argued that parental authority superseded community authority even when there were conflicting notions about the child’s best interest. Aquinas firmly rejected the idea that the children of Jewish parents should be forcibly baptized, “despite his conviction that Catholicism surpasses Judaism in offering a fuller account of the truth about God, and that knowledge of this truth is crucial for happiness both here and in the hereafter.” 68 68 Moschella, To Whom Do Children Belong?, 25. In other words, Aquinas argued that Jewish children should forgo Christian baptism at the wish of their parents, even though he believed this would result in their eternal exclusion. 69 69 Traina, “A Person in the Making,” 115–16.

Parental authority was nevertheless understood to be exercised within the thick network of authoritative relationships that made up medieval society. Committing children to the church through the practice of oblation “worked to forge, and reinforce, on-going relationships between landed families and particular churches.” 70 70 Nelson, “Parents, Children, and the Church,” 110. Given that monastic prayer and stability were understood to be an indispensable component of public order, oblation—which helped maintain the monastic population—was implicitly a political practice as well. 71 71 De Jong, In Samuel’s Image, 231.

More important was the sacrament of baptism, which positioned the child and parents in the wider community. Not only did a child’s baptism bond family and church, 72 72 Nelson, “Parents, Children, and the Church,” 97. but it also formalized the child’s connection to the broader social community. The sacrament confirmed that children from their earliest days would be raised and educated according to Christian virtues. The virtues of medieval Christendom were the shared virtues of the political community. 73 73 Nelson, “Parents, Children, and the Church,” 98. The act of selecting godparents at baptism also embedded the child in the community. The social ties confirmed in godparenthood were a powerful force within medieval society, “crossing class lines and providing emotional support and solidarity.” 74 74 M.L. King, “Children in Judaism and Christianity,” in Fess, Routledge History of Childhood, 53.

Children’s relationship within society was facilitated by their parents. Clergy generally ministered to and exercised authority over children through the adult laity rather than on children’s own terms. Despite the fact that a third of the church’s members were children, ecclesiastical practices were designed to meet the needs of adults. 75 75 Orme, “Children and the Church in Medieval England,” 484–87; Nelson, “Parents, Children, and the Church.” Indeed, the fact that adults were the main beneficiaries of the connections forged in baptism and oblation highlights that children’s welfare was almost always secondary to adult concerns.

Augustine’s theology of original sin loomed large in medieval thought. Aquinas argued that divine grace corrected and completed children’s nature as they matured toward a greater capacity for reason. Parents remained primarily responsible for the spiritual formation of children, navigating the tension between a developing sense of a child’s autonomy and duty of obedience to the family. Baptism played a societal role, connecting children to the community, but also parents to the church and other members of society.

The Protestant Reformation

The Nature of Childhood

Just as in previous ages, Reformation theology devoted little energy toward children and childhood as a specific area of study. What theological work was conducted focused on the transition to adulthood. 76 76 J.E. Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology: ‘For What Purpose Do We Older Folks Exist, Other Than to Care for . . . the Young?,’” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 134; Barbara Pitkin, “‘The Heritage of the Lord’: Children in the Theology of John Calvin,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 161. Heated controversies over the sin nature of human beings influenced conceptions of the nature of children. There was a growing debate over the baptism of children, particularly with the rise of the Anabaptist movement. 77 77 K.E. Spierling, Infant Baptism in Reformation Geneva: The Shaping of a Community, 1536–1564 (London: Routledge, 2017), 4. Although the majority of Reformers believed children were inherently depraved, they did not advocate or condone the unduly harsh treatment of children. Instead, Reformation-era thinkers focused on the work of spiritual formation. 78 78 Ozment, When Fathers Ruled, 147–63; Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology”; Pitkin, “The Heritage of the Lord”; K.G. Miller, “Complex Innocence, Obligatory Nurturance, and Parental Vigilance: ‘The Child’ in the Work of Menno Simons,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 194–226. Children’s clear tendency toward selfish and harmful behaviour was an inevitable result of original sin, but “such behavior could not be the foundation of either society or salvation; obedience to a higher standard of conduct had to be established if a child was to emerge as an adult with a civil and religious will.” 79 79 Ozment, When Fathers Ruled, 163. Parents bore the primary responsibility for addressing misbehaviour with firm discipline, preferring rational persuasion where possible, and corporal punishment where necessary. 80 80 A. Fletcher, “Prescription and Practice: Protestantism and the Upbringing of Children, 1560–1700,” Studies in Church History 31 (1994): 326, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0424208400012961 ; Ozment, When Fathers Ruled, 163.

As in the medieval era, writings from the Reformation reveal a nuanced approach to children’s morality. The Reformers preserved the medieval system of dividing childhood into seven-year stages, with children gaining moral accountability as they matured and their capacity for reason increased. Renaissance humanists such as Erasmus influenced Reformation-era thinking on the developmental significance of early childhood. 81 81 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 43–45; C.W. Atkinson, “‘Wonderful Affection’: Seventeenth-Century Missionaries to New France on Children and Childhood,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 231. It was believed that the pre-puberty stage was critical for formation as children became more intellectually, spiritually, and morally mature over the course of childhood. It was also believed that the plasticity of childhood decreased significantly upon puberty, when rebellion and sexual desire tainted formation. 82 82 Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology”; Pitkin, “The Heritage of the Lord”; Miller, “‘The Child’ in the Work of Menno Simons.” Shaping a child according to Christian virtues and values became an increasingly difficult task as the child grew older and more corrupted by the world. 83 83 Ozment, When Fathers Ruled, 147. Many thinkers believed a child’s core moral character was set by the end of puberty. 84 84 J.R. Watt, “Calvinism, Childhood, and Education: The Evidence from the Genevan Consistory,” Sixteenth Century Journal 33, no. 2 (2002): 144, https://doi.org/10.2307/4143916. This led Luther and his fellow Reformers to insist that “discipline and teaching in the receptive years of childhood were crucial if the person was to make the passage through puberty and into full adulthood successfully.” 85 85 Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology,” 145.

Children in Families

The family gained renewed prominence in the Reformation period. Luther viewed the status of marriage, the home, and parenthood as a hallowed vocation. Every believer had a calling to serve as an “apostle and bishop” within the household. 86 86 Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 89–90; Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology,” 139; Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 46. The abolition of the priest’s authority as the mediator between God and humankind gave new authority to parents. The primary responsibility for the family’s faith formation rested with fathers, whom the Reformers believed had been set as bishops over their families by God. This was a distinct departure from the medieval practice of relegating parental authority over children under age seven to mothers. 87 87 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 42–55; Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology,” 141; Watt, “Calvinism, Childhood, and Education,” 445–47.

The core responsibility of parents to their families was to train their children in godliness from an early age. A central component of this task was educating children in the faith. “Luther, Calvin, and other reformers definitely encouraged religious education in the home, promoting private family devotions and exhorting parents to lead the religious education of their children.” 88 88 Watt, “Calvinism, Childhood, and Education,” 445. Appropriate application of discipline was also an important parental duty. Parents received some portion of the credit or blame for the moral outcomes of their children. 89 89 Pitkin, “The Heritage of the Lord,” 173; Miller, “‘The Child’ in the Work of Menno Simons,” 206–17. Both parental leniency and excessive discipline were thought to reveal a deficit of parental love. 90 90 Ozment, When Fathers Ruled, 146–47; Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 46–47.

The Reformers emphasized children’s duty to obey their parents, believing it to be a central part of discipleship in childhood. 91 91 Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology”; Pitkin, “The Heritage of the Lord”; Ozment, When Fathers Ruled, 150–51. Calvin underscored the importance for all believers to submit to the authority of those God had placed over them. Parents were the primary divinely ordained authority over their children. 92 92 Pitkin, “The Heritage of the Lord,” 172. Strong paternal authority and corresponding filial obedience were seen as crucial elements of a stable society. 93 93 Watt, “Calvinism, Childhood, and Education,” 448; Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 42. Indeed, children in this era “had more duties toward their parents and society than they had rights independent of them.” 94 94 Ozment, When Fathers Ruled, 177. A child was, however, granted some measure of autonomy. According to Luther, parents were not to force children to marry against their will, providing civic officials with the authority to intervene when prudent. Although children were under obligation to obey their parents, Luther provided leniency to children for the sake of obedience to God as the ultimate authority. 95 95 Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology,” 156.

Children in Society

The moral development of children spanned both private and public spheres. The wider community had some authority over and obligations toward children, though this remained secondary to parental authority. 96 96 Spierling, Infant Baptism in Reformation Geneva; Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology”; Pitkin, “The Heritage of the Lord”; Miller, “‘The Child’ in the Work of Menno Simons.” Baptism continued to be an important rite where the obligations between parental and public authority were negotiated. Though the Reformers’ theological understanding of baptism diverged from the medieval church, the sacrament retained its profound social and political implications. The infant was welcomed into the community, while the community members assumed their respective measures of responsibility for and authority over the child. 97 97 M. Halvorson, “Theology, Ritual, and Confessionalization: The Making and Meaning of Lutheran Baptism in Reformation Germany, 1520–1618” (PhD diss., University of Washington, 2001), https://digital.lib.washington.edu:443/researchworks/handle/1773/10335; Spierling, Infant Baptism in Reformation Geneva; Watt, “Calvinism, Childhood, and Education.”

While parents remained the primary authority over children, the church (clergy) and the state (civil magistrates) also exercised a measure of responsibility. 98 98 Spierling, Infant Baptism in Reformation Geneva, 26. Church authorities held parents accountable for their children’s actions. The rise of formal catechism programs may indicate that the church assumed greater responsibility for children’s faith formation. 99 99 Watt, “Calvinism, Childhood, and Education,” 448. One significant result of the growing emphasis on catechesis was a new insistence on universal education and literacy for both boys and girls. 100 100 Watt, “Calvinism, Childhood, and Education,” 449; Ferraro, “Medieval and Early Modern Childhoods,” 71. The state also assumed a more direct role when parents abdicated their responsibilities. 101 101 Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology,” 152. The state ensured that the structures and conditions of society facilitated children’s faith formation. 102 102 Pitkin, “The Heritage of the Lord,” 174.

The Reformation emphasized catechesis and education of all children for the common good. 103 103 Ferraro, “Medieval and Early Modern Childhoods”; Pitkin, “The Heritage of the Lord,” 179–80. Luther’s insistence that all vocations were holy gave new urgency to the task of cultivating each child’s unique gifts. 104 104 Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 89–90. He supported universal education, arguing that parental opposition to education was a sin against children, society, and God. 105 105 Luther, “To the Councilmen,” 727, quoted in Strohl, “The Child in Luther’s Theology,” 151. Parents were accountable to society to foster obedience in their children. It was argued that unchecked selfish behaviour during childhood would lead to selfish adults pursuing self-interest over the common good. “The great fear [in Reformation Europe] was not that children would be abused by adult authority but that children might grow up to place their own individual wants above society’s common good.” 106 106 Ozment, When Fathers Ruled, 177.

Reformation leaders sought to forge distinctive new communities, with Calvin’s Geneva being the most well-known example. For this reason, they focused on the communities’ most malleable members, children. The virtuous formation of children had implications for the future success of these communities. Creating and maintaining the religious and political community’s distinctive identity began with children. Parents held a critically important role in the formation of future citizens. Not only does this context explain Reformers’ insistence on proper discipline and education, but it also fuelled the intensity behind baptismal controversies. Some scholars argue that controlling the initiation of children into the community and setting the terms by which they would be a part of society by regulating parents’ treatment of children was a key way that clergy and civil authorities determined and enforced the character of that community. 107 107 See Watt, “Calvinism, Childhood, and Education”; Halvorson, “Theology, Ritual, and Confessionalization.”

Corrupted by sin, children’s malleable nature required parental attention to spiritual formation. Protestant families gained a renewed sense of vocation toward the virtuous formation of children for the sake of the wider community. Luther and other Reformers emphasized the importance of universal education in the formation of children as a benefit to wider society.

Early Modern Christianity

The Nature of Childhood

The early modern period, encompassing approximately the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, initiated significant changes in the Western understanding of childhood. Influential Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau published tracts on education that “provided a foundation for new concepts of childhood which not only acknowledged the individuality of the child, but by arguing that children were inherently innocent, recognized their potential for goodness.” 108 108 L.A. Ryan, John Wesley and the Education of Children: Gender, Class and Piety (London: Routledge, 2017), 5. A child’s nature was to be preserved and protected from external corruption rather than corrected due to inherent corruption. 109 109 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 58–59.

The focus on childhood as a critically important period of development had only increased since the influence of the Renaissance humanists. Theorists believed the malleable nature of children solidified as they matured. 110 110 John Amos Comenius summarized this belief well in a warning to parents that “although God can make an inveterately bad person useful by completely transforming him, yet in the regular course of nature it scarcely ever happens otherwise than that as a thing has begun to be formed from its origin so it becomes completed, and so it remains. Whatever seed one sows in youth, such fruit he reaps in age. . . . It is impossible to make the tree straight that has grown crooked” (Comenius, The School of Infancy [1633], quoted in Bunge and Wall, “Christianity,” 129–30); see also C.A. Brekus, “Children of Wrath, Children of Grace: Jonathan Edwards and the Puritan Culture of Child Rearing,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 302; R.P. Heitzerater, “John Wesley and Children,” Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 285. Not only were children understood to be uniquely malleable, but they were also vulnerable to negative influences that could irreparably distort their natural goodness. 111 111 Ryan, John Wesley and the Education of Children, 5–17; Brekus, “Children of Wrath, Children of Grace,” 308. Despite the growing dominance of this view, Christian communities such as the Puritans staunchly affirmed the doctrine of original sin. Even still, philosophical opposition to original sin was gaining intellectual ground by the eighteenth century. 112 112 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 58–59.

This intellectual and philosophical shift left its mark on early modern Christianity. Yet many Christian thinkers continued to view rational and moral accountability as a process of child development. Most thinkers conceived of childhood in three stages: infancy ranged from birth until age seven, childhood spanned from age eight until age fourteen, and youth encompassed age fifteen to age twenty-five. Ministry to children required attentiveness to the distinct spiritual needs of each stage of development. 113 113 Brekus, “Children of Wrath, Children of Grace,” 302; M.J. Bunge, “Education and the Child in Eighteenth-Century German Pietism: Perspectives from the Work of A.H. Francke,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 269; Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 90.

Early modern theologians devoted increased attention to childhood. 114 114 Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 90–91. Children were understood to have a unique connection to God. 115 115 Bunge, “Education and the Child,” 270; A.C. Schutt, “‘What Will Become of Our Young People?’ Goals for Indian Children in Moravian Missions,” History of Education Quarterly 38, no. 3 (1998): 268–86, https://doi.org/10.2307/369156. Some theologians specifically addressed the spiritual lives of children, recognizing that childlike faith served as an example for adults. Leading Protestant preachers such as Jonathan Edwards and Nikolaus von Zinzendorf addressed sermons specifically to children, 116 116 Brekus, “Children of Wrath, Children of Grace”; Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 131. while parents were advised to respect and nurture the individuality of each child. 117 117 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 58–69. Children on both sides of the Atlantic participated in the evangelical revivals of the seventeenth century. The New England Puritans and European Pietists spoke of the conversion experiences of children and encouraged childlike spiritual virtues such as simplicity, trust, dependence, and openheartedness. 118 118 A.C. Schutt, “Complex Connections: Communication, Mobility, and Relationships in Moravian Children’s Lives,” Journal of Moravian History 12, no. 1 (2012): 38–39.

Children in Families

During this period, the household was regarded as “an emblem and bastion of the Church and state.” 119 119 A. Walsham, “Holy Families: The Spiritualization of the Early Modern Household Revisited,” Studies in Church History 50, no. 1 (2014): 160, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0424208400001686. Properly ordered family life was central to godliness and the health of the social and political order. 120 120 A. Walsham, “Introduction: Religion and the Household,” Studies in Church History 50, no. 1 (2014): xxi–xxxii. The Puritans emphasized the importance of family worship and viewed filial obedience as an indispensable component of societal stability. 121 121 W. Coster, Baptism and Spiritual Kinship in Early Modern England (London: Routledge, 2017), 275, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315261751; C.J. Robinson, “The Home Is an Earthly Kingdom: Family Discipleship Among Reformers and Puritans,” Family Ministry Today, March 25, 2013, https://www.sbts.edu/family/2013/03/25/3221/. Nevertheless, the large-scale economic and social changes of the early modern period shifted traditional authority structures within family life. 122 122 Brekus, “Children of Wrath, Children of Grace,” 307–8; Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 42. Mothers gained new recognition as the moral centre of the household and assumed a greater role in the education and formation of young children in the home. 123 123 Atkinson, “Wonderful Affection,” 234; Heitzerater, “John Wesley and Children,” 285.

Although family life was shifting, the focus for Christian families remained on raising children devoted to the love of God and neighbour. Parents bore the primary responsibility for this task and were exhorted to begin the process early in a child’s life. 124 124 Bunge, “Education and the Child”; Brekus, “Children of Wrath, Children of Grace”; Ryan, John Wesley and the Education of Children. Moravian bishop Johann Amos Comenius, for instance, wrote that “inasmuch as every [child] ought to be competent to serve God and be useful to human beings, we maintain that he ought to be instructed in piety, morals, in sound learning, and health. Parents should lay the foundations of these in the very earliest age of their children.” 125 125 Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 130. In addition to these virtues, Puritan and Pietist revivals brought a new focus on spiritual experience, which parents were to share with their children. 126 126 D. Devries, “‘Be Converted and Become as Little Children’: Friedrich Schleiermacher on the Religious Significance of Childhood,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 333; Brekus, “Children of Wrath, Children of Grace,” 301. Christians placed greater emphasis on children’s inclination toward imitation, resulting in increased attention to ensuring that parents modelled the piety and virtues children were to adopt. 127 127 Heitzerater, “John Wesley and Children,” 282; Bunge, “Education and the Child,” 264–65; Ryan, John Wesley and the Education of Children, 15; Brekus, “Children of Wrath, Children of Grace,” 321. Even though parents retained the primary role of spiritual formation, the growth in the prevalence of educational institutions meant that children’s instruction in the faith was increasingly no longer the exclusive responsibility of parents. 128 128 See Bunge, “Education and the Child,” 270; Ryan, John Wesley and the Education of Children, 7–9.

Corporal punishment was beginning to decline in popularity throughout the West. Although corporal punishment continued to be an acceptable means of discipline, theologians argued that it should be a last resort. 129 129 Bunge, “Education and the Child”; Ryan, John Wesley and the Education of Children; Atkinson, “Wonderful Affection.” Christian child-rearing advice reflected this trend, with social reformer and Moravian bishop Nikolaus von Zinzendorf exhorting parents that “[children] must be drawn to the Christian life lovingly, not by force.” 130 130 N. von Zinzendorf, “Brief Essay on the Christian Nurture of Children,” quoted in Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 132. This coincided with the growing emphasis on parental modelling of virtues.

Children in Society

Social and economic developments in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries resulted in greater community and state involvement in the formation of children. Catholic and Protestant traditions devoted increased attention to education. The massive economic transformations experienced in the West in the early modern period made literacy increasingly important. 131 131 Ryan, John Wesley and the Education of Children, 6. Greater attention was paid to the plight of poor children, and providing universal education was a central focus among Christian social reformers. They saw education as a means to increasing knowledge and piety, 132 132 Heitzerater, “John Wesley and Children,” 292–93; Bunge, “Education and the Child,” 269–70. renewing the population as a whole. 133 133 Ryan, John Wesley and the Education of Children, 7–9. Lutheran pastor August Hermann Francke consistently argued in his writings that “the education of children and young people and the care of the poor are the two best vehicles for improving church and society in all ‘realms’ (the household, the school, the church, the government).” 134 134 Bunge, “Education and the Child,” 259. International Christian missions were proliferating during this period, and education was key to the Christianization of non-Western Indigenous societies. 135 135 Atkinson, “‘Wonderful Affection’”; Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 90.

The concern for the moral and religious instruction of every child entailed a shift toward formal, institutional learning. Churches and the laity founded schools as an important charitable activity directed toward children in poverty. 136 136 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 115. Jesuit schools became renowned for their educational excellence, 137 137 Atkinson, “Wonderful Affection,” 230. while Moravian communities operated boarding schools for children as young as eighteen months. 138 138 Schutt, “Complex Connections.” The shift toward institutional learning began to displace previous notions of parental responsibility for instruction and formation.

The church maintained the central role within formal education, determining curriculum and employing clergy as teachers. Meeting educational needs, particularly among the impoverished, proved to be challenging. Toward the latter half of the eighteenth century the state increasingly became involved in the provision of education. 139 139 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 122–28. As a result, by the end of the early modern era, Western Christians found themselves in a society in which “central governments were increasingly taking the lead in issues to do with childhood.” 140 140 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 118.

The Enlightenment profoundly shaped views on the nature of children. Uncorrupted, children were viewed as malleable but also vulnerable. There was a greater emphasis on children’s autonomy. This philosophical shift contributed to growing consideration for who should be protecting and influencing children. Puritan and Pietistic movements continued to focus on the primary role of families in the formation of virtue in children. Increased emphasis was placed on children and their role as spiritual examples. Although families retained the primary authority over children, as educational institutions proliferated they assumed more authority in the lives of children.

Late Modern Christianity

The Nature of Childhood

The nineteenth century witnessed a revolution in childhood in the West, with the dominance of a sentimental view of children, particularly within middle-class Victorian families. The shift was influenced by the Romantic idealization of nature and Enlightenment notions of the uncorrupted nature of the child. Childhood became idealized as the most valuable stage of life. 141 141 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 58. Children in wealthier classes were viewed with a newfound sense of vulnerability and dependence, at risk of corruptibility. 142 142 R.R. Ruether, Christianity and the Making of the Modern Family (Boston: Beacon, 2001), 83; M. Bendroth, “Children of Adam, Children of God: Christian Nurture in Early Nineteenth-Century America,” Theology Today 56, no. 4 (January 1, 2000): 500, https://doi.org/10.1177/004057360005600405. Children from wealthier families were relied on less as economic assets and were viewed as “objects of intensive nurture and dependency.” 143 143 Ruether, Christianity and the Making of the Modern Family, 90.

The late modern era witnessed the rapid growth of psychology and other academic disciplines that focused on the formation of children from a scientific perspective. 144 144 T. Kössler, “Towards a New Understanding of the Child: Catholic Mobilization and Modern Pedagogy in Spain, 1900–1936,” Contemporary European History 18, no. 1 (2009): 14–15, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960777308004803; Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 90–91. Christian education adopted these ideas, tailoring instruction to developmental stages. 145 145 M.A. Hinsdale, “‘Infinite Openness to the Infinite’: Karl Rahner’s Contribution to Modern Catholic Thought on the Child,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 439. Twentieth-century Spanish Catholic headmaster Mario Franco, for example, insisted that educators “study child behaviour with the same patience biologists use in the study of insects.” 146 146 Kössler, “Towards a New Understanding of the Child,” 15.

By the nineteenth century, the centuries-old notion regarding the original sin nature of children had been significantly challenged within the popular Western imagination. 147 147 M. Bendroth, “Horace Bushnell’s Christian Nurture,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 357–58. The evangelical revivals at the end of the eighteenth century reinvigorated the doctrine of original sin into the first half of the nineteenth century; 148 148 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 66. however, a number of Christian thinkers articulated a moderated position concerning children. 149 149 Hinsdale, “Infinite Openness to the Infinite,” 429. Influenced by Romantic thought, other Christian thinkers adopted a different position articulated by the future Cardinal Newman (1801–1890) in the 1830s, who described the child as proceeding “out of the hands of God, with all lessons and thoughts of Heaven freshly marked upon him.” 150 150 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 69. Similarly, influential theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834) viewed children as models of the untainted revelation of the divine. 151 151 Devries, “Be Converted and Become as Little Children,” 339. Historical concerns about the sin nature of children were eclipsed by anxiety about the corrupting influence of external forces. 152 152 Bendroth, “Children of Adam, Children of God,” 499.

As the notion of child depravity began to wane, Christian theologians moderated the earlier emphasis on children’s sin nature. For example, American Protestant theologian Horace Bushnell (1802–1876) maintained a position positing inborn sin within children, but criticized the strong emphasis that revivalist preachers placed on the issue as extreme and harmful. 153 153 Bendroth, “Horace Bushnell’s Christian Nurture”; Bendroth, “Children of Adam, Children of God.” A century later, Catholic theologian Karl Rahner (1904–1984) rejected the Romantic idea of the child as “a pure source which only becomes muddied at a later stage” and called for a reinvigorated doctrine of original sin that was nevertheless much more moderate compared to that of Augustine. 154 154 Hinsdale, “Infinite Openness to the Infinite,” 429. Even these moderated positions were increasingly out of step with the growing consensus in Western culture that “the very idea of infant depravity seemed irrational and unjust.” 155 155 Bendroth, “Children of Adam, Children of God,” 496.

Children in Families

As in earlier periods, the Christian family remained the primary authority responsible for children’s faith formation. 156 156 Bendroth, “Horace Bushnell’s Christian Nurture,” 356; C. McDannell, The Christian Home in Victorian America, 1840–1900 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), xv. Children were exhorted to obey their parents, subordinating their own desires for the sake of the common good. 157 157 Devries, “Be Converted and Become as Little Children,” 344. Larger cultural shifts in the understanding of the nature of childhood influenced parental approaches to formation. Corporal punishment continued to slowly decline, as some considered it an ineffective means by which to instill a genuine desire for the good in a child’s heart. 158 158 Devries, “Be Converted and Become as Little Children,” 343; Bendroth, “Horace Bushnell’s Christian Nurture,” 356. Some Christian thinkers also challenged this form of discipline, including Schleiermacher, who argued, “Just as the law never effects anything better than the knowledge of sin, and not the strength for good action, just as little can punishment produce anything but an external prevention of sin, and not any turning away of the heart from evil, for punishment derives its power from fear or from bitter experience.” 159 159 F. Schleiermacher, The Christian Household: A Sermonic Treatise, quoted in Bunge and Wall, “Children and Childhood in World Religions,” 136. With the popular emphasis on children’s extreme impressionability, a number of Christian thinkers focused instead on the household environment as a key contributor to faith formation. 160 160 Bendroth, “Horace Bushnell’s Christian Nurture,” 354. Protestants and Catholics alike viewed the cultivation of piety within the household as the foundation of public morality and faith in society. 161 161 Bendroth, “Horace Bushnell’s Christian Nurture,” 356; McDannell, The Christian Home in Victorian America, xv.

The economic changes of industrialization created greater separation between the private sphere of the household and the public sphere, 162 162 Bendroth, “Horace Bushnell’s Christian Nurture,” 358; L. Wilson, “‘Domestic Charms, Business Acumen, and Devotion to Christian Work’: Sarah Terrett, the Bible Christian Church, the Household and the Public Sphere in Late Victorian Bristol,” Studies in Church History 50, no. 1 (2014): 405–6, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0424208400001868. particularly as men’s paid work occurred outside the home. Child-rearing increasingly became the focus within households with the emergence of the middle class. 163 163 Bendroth, “Children of Adam, Children of God,” 500. This shift fuelled sharper distinctions between the role of fathers and mothers within the family. 164 164 Devries, “Be Converted and Become as Little Children,” 332. Unlike it had been in the past, raising children became almost exclusively the mother’s responsibility, according to some scholars. 165 165 Wilson, “Domestic Charms,” 411; Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 64–71; Devries, “Be Converted and Become as Little Children,” 332. With the growing emphasis on the role of children’s environment in formation, mothers faced increasing pressure to protect their children from negative influences and to facilitate proper formation toward virtuous behaviour. 166 166 G. Atkins, “‘Idle Reading’? Policing the Boundaries of the Nineteenth-Century Household,” Studies in Church History 50, no. 1 (2014): 333; Bendroth, “Children of Adam, Children of God,” 500. Vanderbilt scholar Bonnie Miller-McLemore argues that this was a relatively new anxiety, arguing, “The very idea that improper maternal love could permanently harm a child’s development, dictating how they would turn out as adults, was virtually unheard of in the Middle Ages” 167 167 B.J. Miller-McLemore, Let the Children Come: Reimagining Childhood from a Christian Perspective (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2019), 6.

Children in Society

The late modern era’s new valuation of childhood led to public efforts to preserve childhood as a protected stage of life. Christians had traditionally been at the forefront of ministering to children, focusing on their religious education and moral formation. Beginning in the nineteenth century, however, “a concern to save children for the enjoyment of childhood” began to drive public initiatives to improve child welfare. These activities were initially spearheaded by Christian philanthropists. 168 168 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 137. Throughout the West, philanthropic societies sought to intervene on behalf of at-risk children in order to transform the character of both the child and the wider community. 169 169 See J.J.H. Dekker, “Transforming the Nation and the Child: Philanthropy in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and England, c. 1780–c. 1850,” in Charity, Philanthropy and Reform: From the 1690s to 1850, ed. H. Cunningham and J. Innes (Houndmills, UK: Macmillan, 1998), 130–47. The primary responsibility for this task began to shift toward the state at the turn of the century. 170 170 Cunningham, Children and Childhood, 140.

St. John Bosco (1815–1888) challenged the authoritarian pedagogy of his day, practicing what he called a Preventive System among his students. Working with abandoned boys, Bosco’s approach focused on reason, religion, and kindness. He argued that educators must teach and practice reason, walking alongside students much the way we think of mentors today. Religion focused on catechesis as a means of pursuing fulfillment in a life of grace. Finally, loving-kindness encapsulated his desire to create a family-like environment, focusing on gentle correction. 171 171 L. Frith-Powell, “The ‘Preventive System’: Walking Alongside,” Humanum, Education, no. 1 (2015), https://humanumreview.com/articles/the-preventive-system-walking-alongside.

Maria Montessori understood that children’s psychic and spiritual needs must be met for healthy development. She argued that early development was formative for later adulthood, stating, “It is the child who makes the man.” 172 172 Montessori as quoted in E. Roderick, “‘Living in the Condition of Love’s Gift’: Hans Urs von Balthasar’s Theological Anthropology of Childhood and Its Significance for the Form of Human Freedom” (ThD diss., Washington, DC, The Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and the Family at the Catholic University of America, 2014), 53. Montessori grounded her understanding of children in the revelation of God as creator and redeemer. “God has given the child a nature of its own and has fixed certain laws for his development.” 173 173 Montessori as quoted in Roderick, “Living in the Condition of Love’s Gift,” 58. Montessori argued for an apostolate of the child to build civilization. The invitation to love a child changes adults. She stated, “The child can annihilate selfishness and awaken a spirit of sacrifice” in adults. 174 174 Montessori as quoted in Roderick, “Living in the Condition of Love’s Gift,” 60.

Devout Anglican Charlotte Mason (1842–1923), founder of the Parents’ National Educational Union (PNEU) and one of the late modern period’s most influential educationalists, built her philosophy of education on the foundational premise that children were born persons. 175 175 S.S. Macaulay, For the Children’s Sake: Foundations of Education for Home and School (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2009), 12; S. Spencer, “‘Knowledge as the Necessary Food of the Mind’: Charlotte Mason’s Philosophy of Education,” in Women, Education, and Agency, 1600–2000: An Historical Perspective, ed. S.J. Aiston, J. Spence, and M.M. Meikle, Routledge Research in Gender and History 9 (London: Routledge, 2010), 105–25, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203882610; M.A. Coombs, Charlotte Mason: Hidden Heritage and Educational Influence (London: Lutterworth, 2015), 2. She held that each child is “not born either good or bad, but with possibilities for good and for evil.” 176 176 C.M. Mason, An Essay Towards A Philosophy of Education: A Liberal Education for All, Routledge Library Editions: Education 146 (London: Routledge, 2012), xxix. Education thus played a critical role in bringing out the good in every person. 177 177 See J.C. Smith, “Charlotte Mason: An Introductory Analysis of Her Educational Theories and Practices” (PhD diss., Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2000), 84–87, https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/27029/jcsmithfinaldissertation.pdf. Mason argued that the religious instruction of children was an indispensable component of proper education: “We allow no separation to grow up between the intellectual and ‘spiritual’ life of children, but teach them that the Divine Spirit has constant access to their spirits, and is their continual Helper in all the interest, duties, and joys of life.” 178 178 Mason, An Essay Towards a Philosophy of Education, xxxi.

The role of non-family institutions in children’s development continued to expand. The upheaval experienced by working-class families, for instance, led to calls to supplement the family’s role in early childhood nurture with child care outside the home, such as kindergartens. 179 179 A.T. Allen, “Gardens of Children, Gardens of God: Kindergartens and Day-Care Centers in Nineteenth-Century Germany,” Journal of Social History 19, no. 3 (Spring 1986): 433–50; M.Y. Riggs, “African American Children, ‘The Hope of the Race’: Mary Church Terrell, the Social Gospel, and the Work of the Black Women’s Club Movement,” in Bunge, The Child in Christian Thought, 365–85. Laws instituting compulsory education reflected greater encroachment of the state into affairs of childhood, particularly for poorer children. 180 180 S. Auerbach, “‘Some Punishment Should Be Devised’: Parents, Children, and the State in Victorian London,” Historian 71, no. 4 (2009): 761, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6563.2009.00249.x. Yet the secularization of cultural institutions meant that the society in which Christians raised their children was changing dramatically. The influence of social institutions that were increasingly less supportive of, if not hostile to, Christian formation became a new source of anxiety for parents and the church. 181 181 Hinsdale, “Infinite Openness to the Infinite,” 417; T. Winright and T.D. Whitmore, “Children: An Undeveloped Theme in Catholic Teaching,” in The Challenge of Global Stewardship: Roman Catholic Responses, ed. M.A. Ryan and T.D. Whitmore (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1997), 162, https://www.academia.edu/24400826/_Children_An_Undeveloped_Theme_in_Catholic_Teaching_in_Ryan_and_Whitmore_eds._The_Challenge_of_Global_Stewardship_University_of_Notre_Dame_Press_1997_. Education systems in particular were a cultural battleground in Western nations as church authorities, whose traditional jurisdiction over schooling was being eroded, and secular theorists each attempted to further their respective visions for social order. 182 182 Kössler, “Towards a New Understanding of the Child,” 2.