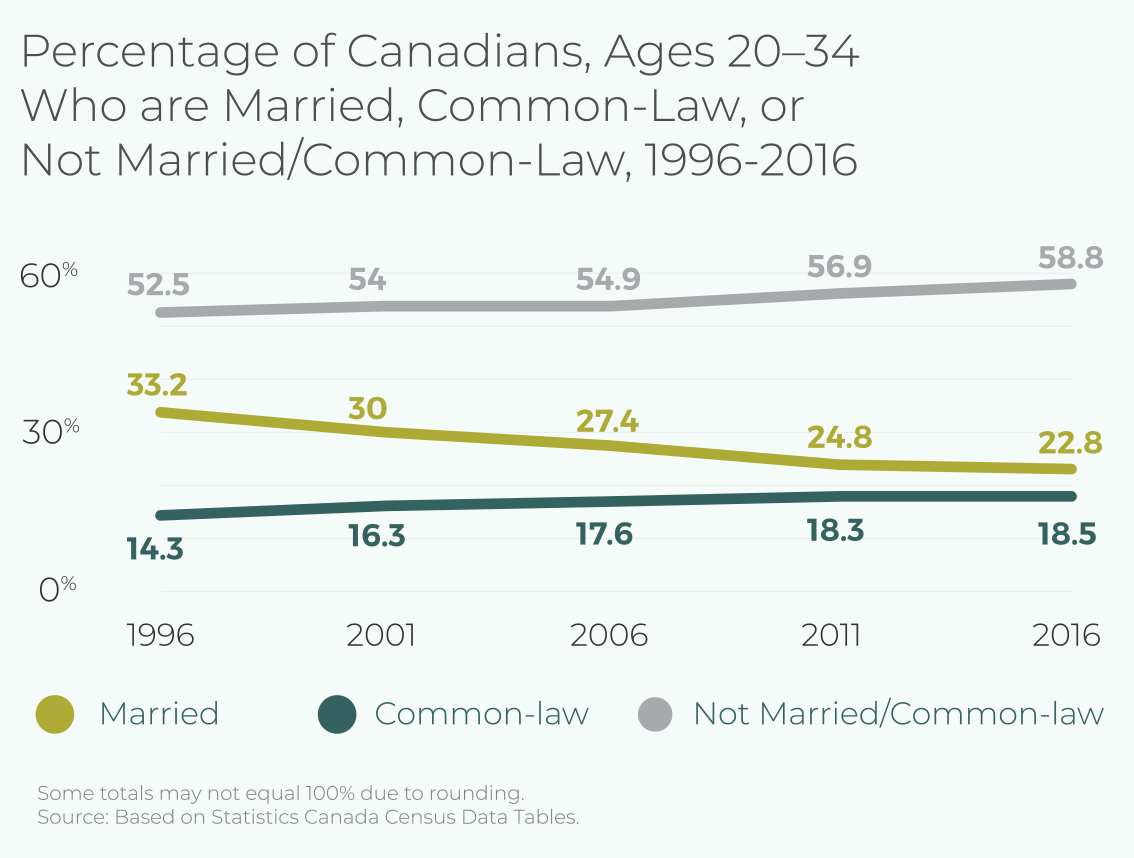

As the Canadian Marriage Map 1 1 “Canadian Marriage Map,” Cardus, 2020, http://www.marriagemap.ca. illustrates, an increasing proportion of young adults aged twenty to thirty-four are living unpartnered, and those who do marry are marrying at later ages. While many are choosing to live common-law before marriage, or to remain common-law instead of marry, the increase in common-law coupling among young adults is outpaced by the decline in marriage. In short, young Canadian adults are partnering less.

This decline in partnering is evident over several census cycles. Census data in Figure 1 shows that between 1996 and 2016 the portion of Canadians aged twenty to thirty-four who were not living in a partnership rose from about 53 percent to about 59 percent. As young adults age, they are more likely to partner, but even among thirty- to thirty-four-year-olds, about 35 percent are living unpartnered.

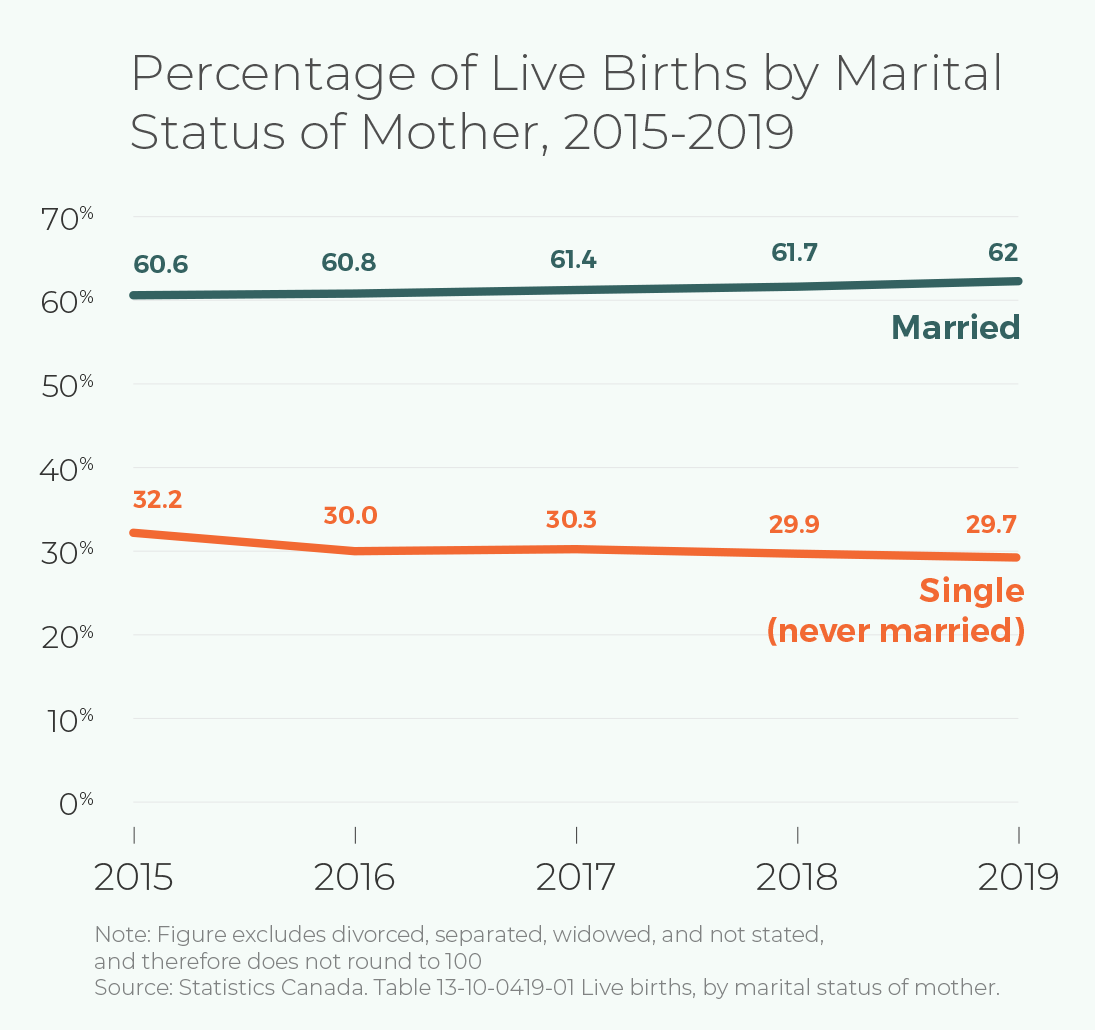

Prior to the pandemic, Canada’s fertility rate was at a historic low. Given that the majority of Canadian children are born into couple families and the majority of these couples are married, reversing this trend toward delayed fertility will be unlikely without a corresponding reversal of the trend toward delayed or forgone partnering and marrying.

Why Are Young Adults Partnering Less?

Numerous factors have contributed to the decline in partnering. The pathway to adulthood has become elongated, with young adults reaching the traditional markers of adulthood, such as marriage, children, and home ownership, at later ages. The cost of housing is rising faster than incomes. Many young Canadians are spending longer in school, with increased student debt, but experience uncertain employment prospects. Those with lower educational attainment are even less likely to marry than their peers. One sign of this elongation is that the portion of young adults between the ages of twenty and thirty-four that live with at least one parent has been increasing in every census since 2001. 2 2 “Young Adults Living with Their Parents in Canada in 2016,” Statistics Canada, August 2, 2017, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/98-200-x/2016008/98-200-x2016008-eng.cfm. Disinterest in work and education among some young men may be contributing to this trend, while other young adults face barriers to achieving the stable independence they desire. Economic factors are only one part the equation. Shifting cultural attitudes have reshaped how many young adults approach marriage. Andrew Cherlin, sociologist at Johns Hopkins University, describes that in the past, couples tended to view marriage as the foundation on which to develop other elements of adult life. He argues that couples today frequently view marriage as a capstone, to be entered into once career aspirations and other markers of stability are secured. 3 3 A.J. Cherlin, The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today (New York: Vintage, 2010).

University of Virginia sociologist Brad Wilcox argues that a “soulmate” view of marriage has been the dominant approach over the last few decades. The soulmate model prioritizes individual fulfilment through intense romantic, emotional connection, in contrast to an “institutional” view of marriage that focuses on aspects of the relationship such as economic partnership, parenthood, and mutual love and support. Yet Wilcox’s research suggests that the institutional model is more stable and more likely to lead to a higher-quality relationship. 4 4 W.B. Wilcox and J. Dew, “Is Love a Flimsy Foundation? Soulmate versus Institutional Models of Marriage,” Social Science Research 39, no. 5 (2010): 687–99, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.05.006.

These shifts in the approach to marriage reflect a larger cultural shift in North America in the way that people engage with institutions generally. Author and scholar Yuval Levin argues that institutions are intended to form people, shaping character and behaviour toward a task or goal. He notes that increasingly institutions are viewed less as a means of formation and more as a platform for self-expression. 5 5 Y. Levin, “Opinion: How Did Americans Lose Faith in Everything?,” New York Times, January 18, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/18/opinion/sunday/institutions-trust.html.

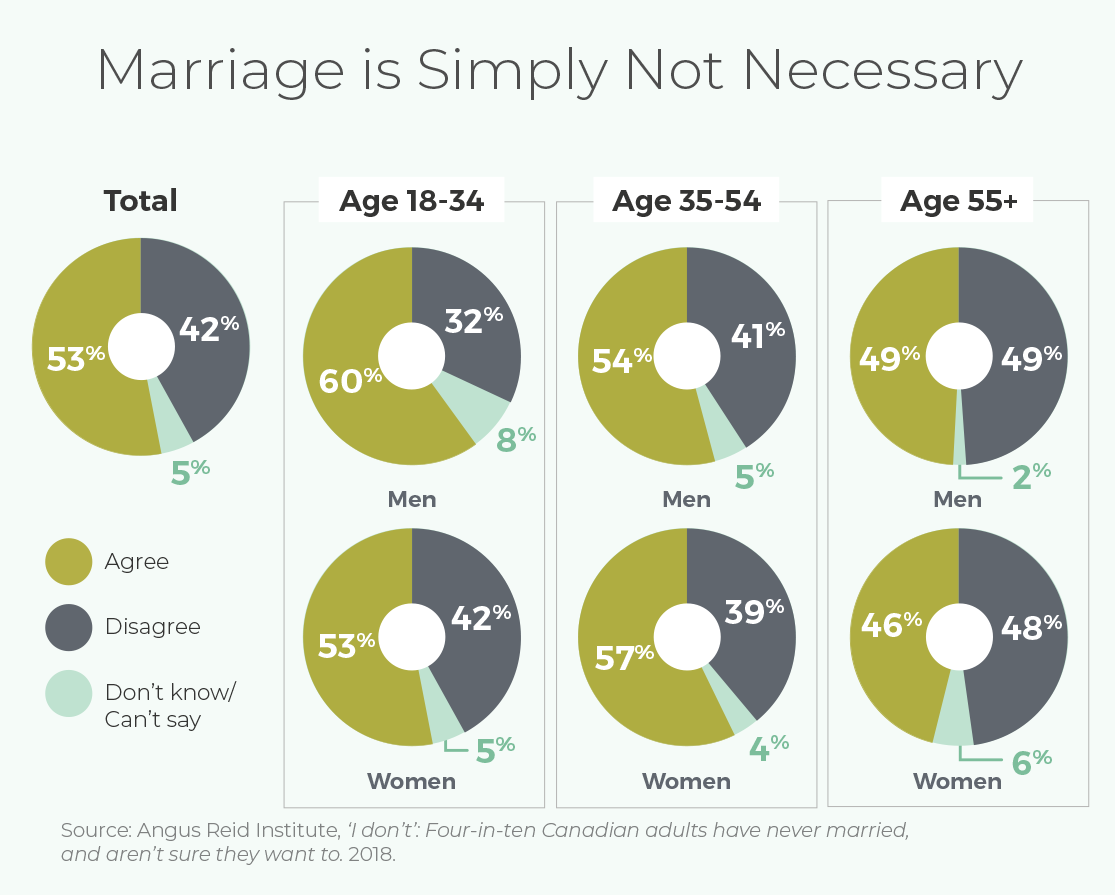

The shift from understanding marriage as a formative relationship to seeing it as an expressive status decreases the importance of marriage for some young adults who consider other options for individual expression. As illustrated in Figure 2, an Angus Reid Institute survey found that 57 percent of eighteen- to thirty-four-year-olds agree that “marriage is simply not necessary.” For many young adults considering their options today, marriage is a “nice to have,” not a necessity.

Is the Growing Portion of Unpartnered Young Adults a Concern?

A healthy pluralism recognizes that marriage isn’t for everyone. So why pay attention to shifting attitudes toward marriage, its decline, and the corresponding increase in adults living unpartnered?

First, plenty of evidence suggests that stable, healthy marriage is good for society and individuals. 6 6 N. Schulz, Home Economics: The Consequences of Changing Family Structure (Washington, DC: AEI Press, 2013); S. Martinuk, “Marriage Is Good for Your Health,” Cardus, September 29, 2016, https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/reports/marriage-is-good-for-your-health/. For example, such marriages correlate positively with better mental and physical health and lower risk of poverty, which contributes to greater social stability. Children raised in stable married-parent homes show, on average, better emotional, cognitive, and physical health compared with peers in other environments, which makes them more likely to grow up into adults equipped to contribute positively to societal well-being. 7 7 D.C. Ribar, “Why Marriage Matters for Child Wellbeing,” The Future of Children 25, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 11–27, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1079374.pdf. Declining rates of marriage and partnership also have a number of social implications. One of these is the effect on fertility: the majority of children are born into couple families, and the delay and decline in stable couple relationships contributes to declining fertility.

The decline in partnership is also correlated with rising inequality. Data suggest that individuals with greater educational attainment and access to higher income are more likely to meet, marry, have children, and stay together than their less-educated peers. In addition, these more stable families transfer their wealth and social capital more easily to their children than less-stable families. 8 8 W.B. Wilcox, “Home Economics: As the Family Goes, So Goes the Economy. Event Summary,” Cardus, May 29, 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Home-Economics-Summary-v2.pdf; P.J. Mitchell and P. Cross, “The Marriage Gap Between Rich and Poor Canadians,” Institute for Marriage and Family Canada, February 25, 2014, https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/articles/the-marriage-gap-between-rich-and-poor-canadians/.

Canada’s Pre-Pandemic Fertility Problem

Prior to the pandemic, Canada posted a total fertility rate of 1.47, the lowest in the nation’s history. 9 9 “Births, 2019,” Statistics Canada, September 29, 2020, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200929/dq200929e-eng.htm. As in many other Western countries, fertility in Canada has been declining for decades, and there are a number of contributing factors. Where children were once an important contributor to the household economy on family farms or in other family businesses, couples today are more likely to desire a sense of financial stability before bearing the cost of raising children.

Unsurprisingly, the same factors affecting partnership trends also affect fertility. The economic and cultural factors discussed above have contributed to delayed and forgone childbearing. Reliable birth control and women’s increased participation in the labour force have also resulted in shifts in the timing and number of children.

Prior to the pandemic, Canada posted a total fertility rate of 1.47, the lowest in the nation’s history. 10 10 “Births, 2019,” Statistics Canada, September 29, 2020, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200929/dq200929e-eng.htm. As in many other Western countries, fertility in Canada has been declining for decades, and there are a number of contributing factors. Where children were once an important contributor to the household economy on family farms or in other family businesses, couples today are more likely to desire a sense of financial stability before bearing the cost of raising children.

Unsurprisingly, the same factors affecting partnership trends also affect fertility. The economic and cultural factors discussed above have contributed to delayed and forgone childbearing. Reliable birth control and women’s increased participation in the labour force have also resulted in shifts in the timing and number of children.

Demographer Lyman Stone argues that international historical evidence shows that cultural values and attitudes have significant long-term influences on fertility. 11 11 L. Stone, “What Makes People Have Babies? The Link Between Cultural Values and Fertility Rates,” Public Discourse (blog), May 7, 2019, https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2019/05/51661/. In most Western nations, people are not having the number of children that they say they desire. At the same time, cultural shifts influence the level of intended fertility. For example, Statistics Canada data suggest that fertility intentions are higher among religious adherents. 12 12 D. Dupuis, “What Influences People’s Plans to Have Children?,” Canadian Social Trends 48 (Spring 1998): 3, http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/statcan/11-008/CS11-008-48-eng.pdf. Thus the increased secularization of Canadian society may play a role in lower fertility.

Stone and his co-author, sociologist Laurie DeRose, argue that the low fertility observed in high-income countries is partly explained by the value that people put on work and careers as a source of meaning. Increased educational attainment and resulting employment do not in themselves compete with fertility, but the value put on meaning derived from work competes with interests in forming and growing families. 13 13 L. DeRose and L. Stone, “More Work, Fewer Babies: What Does Workism Have to Do with Falling Fertility?” (Charlottesville, VA: Institute for Family Studies and Social Trends Institute, March 2021), https://ifstudies.org/ifs-admin/resources/reports/ifs-workismreport-final-031721.pdf. They argue that this partially explains fertility decline even in countries with generous social benefits that lower the cost of having children and increase workforce attachment among parents.

The Pandemic

Data from around the world suggest that the global pandemic has led women to delay or forgo having children. 14 14 M.S. Kearney and P.B. Levine, “The Coming COVID-19 Baby Bust: Update,” Brookings Institution, December 17, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/12/17/the-coming-covid-19-baby-bust-update/. Labour-force conditions and personal incomes are a chief consideration in the rise and fall of fertility rates. 15 15 M.S. Kearney and P.B. Levine, “Opinion: We Expect 300,000 Fewer Births Than Usual This Year,” New York Times, March 4, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/04/opinion/coronavirus-baby-bust.html. Data suggest that previous economic hardship has been a significant factor in fertility decline in Canada. Fertility fell after the 2008 financial crisis in Canada’s most populous provinces, Ontario and Quebec, and the declines have still not recovered. 16 16 M. Moyser and A. Milan, “Fertility Rates and Labour Force Participation among Women in Quebec and Ontario,” Statistics Canada, July 18, 2018, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2018001/article/54976-eng.htm. Early indications are that the number of births in several Canadian provinces fell in 2020. 17 17 P. Cain, “Nine Months after the Pandemic Arrived, Births Fell Sharply: Data,” CTV News, March 6, 2021, https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/nine-months-after-the-pandemic-arrived-births-fell-sharply-data-1.5335809; A. Tucker, “Albertans Should Expect a Baby Bust—Not Boom—and Fewer People Tying the Knot, Statistics Reveal,” CBC, February 14, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/alberta-fewer-births-fewer-marriages-in-2020-statistics-1.5912936.

What Are the Implications of Low Fertility?

The decision to have children, and when to have them, is deeply personal, but these decisions taken collectively have significant public implications. Fertility rates have an impact on labour supply and on the state’s ability to meet entitlement obligations such as health care and public pensions. Like many Western nations, Canada’s population is aging, with more people over the age of sixty-five than under the age of fifteen. This age imbalance will strain the future ability to finance social programs and meet other fiscal obligations. There is also evidence that chronically low fertility influences the decline in interest rates, increasing the long-term financial impact. 18 18 M. Bird, “The Covid Baby Bust Could Reverberate for Decades,” Wall Street Journal, March 5, 2021, https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-covid-baby-bust-could-reverberate-for-decades-11614962945.

It’s not just the economic impact that Canadians should be concerned about. Low fertility and an aging population will also affect aspects of civil society, as fewer people will share an increased obligation to provide unpaid caregiving.

Finally, lower levels of partnership and desired fertility may indicate that some people are not achieving the family life they desire, affecting happiness and overall sense of well-being.

What Can Be Done?

imply increasing the number of married or partnered young adults won’t necessarily increase fertility, but it is difficult to see how current fertility trends can change while the portion of partnered young adults continues to decline. What can be done to address the various factors contributing to low fertility and declining partnership?

Public policy is part of the response, and many nations have attempted to legislate their way to a solution. Internationally, some governments have tried to mitigate the impact of low fertility through increased immigration. Some have tried to incentivize families to have more children, with cash benefits and allowances, government loans, extended parental leaves, and public child care, among other initiatives. The data suggest that these policies can marginally increase fertility rates, but at a substantial cost that is difficult to maintain. 19 19 L. Stone, “Pro-Natal Policies Work, But They Come With a Hefty Price Tag,” Institute for Family Studies (blog), March 5, 2020, https://ifstudies.org/blog/pro-natal-policies-work-but-they-come-with-a-hefty-price-tag. Writing in the New York Times, economist Melissa Kearney observes, “Even in Scandinavian countries, with their more generous government programs for families and less gendered division of household roles, birthrates have been falling.” 20 20 Kearney and Levine, “Opinion: We Expect 300,000 Fewer Births Than Usual This Year.”

Lyman Stone argues that even small increases in fertility in response to financial incentives should be given consideration by policymakers. In addition to governments considering cash incentives, he argues, “It’s vital that policymakers also think about how they can remove obstacles to marriage, facilitate access to decent housing, and accelerate completion of education—all vital elements in the modern economic life cycle leading up to childbearing. Without such a broad approach, pro-natal efforts will involve spending a great deal of money without a lot of results to show for it.” 21 21 Stone, “Pro-Natal Policies Work, But They Come With a Hefty Price Tag.”

So public policy, at substantial cost, can mitigate some of the factors that make partnering and childbearing difficult, particularly when these roadblocks are financial. Cultural attitudes are more complex. Perhaps one cultural consideration is the value of children and the parent-child relationship. Connection between marriage and parenting risks becoming a casualty of the soulmate model of marriage, centred as it is upon the adults’ romantic relationship. Theologian Vigen Guroian writes, “To the extent that these notions of individualism and autonomy influence contemporary thought on childhood, there is a tendency to define childhood apart from serious reflection on the meaning of parenthood. Yet a moment’s pause might lead one to recognize that there is hardly a deeper characteristic of human life than the parent-child relationship.” 22 22 V. Guroian, “The Ecclesial Family: John Chrysostom on Parenthood and Children,” in The Child in Christian Thought, ed. M.J. Bunge (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2001), 61.

Policies that attempt to mitigate pressure on families can inadvertently devalue parenthood by having the state assume primary responsibility for children. Bruce Fuller, professor of education and public policy at the University of California, Berkeley, has written on the push for pre-kindergarten learning, arguing that policymakers “exemplify how elites within civil society recurrently attempt to push a normative way of raising children, even a standard institution, into the lives of America’s breathtakingly diverse array of families.” 23 23 B. Fuller, Standardized Childhood: The Political and Cultural Struggle over Early Education (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), xv. He concludes, “I do worry that the push to universalize and standardize pre-schooling in America will disempower parents from the most essential human task of all: raising young children.” 24 24 Fuller, Standardized Childhood, xxii. In helping families, policy should not disincentivize parenting work or the value of time with children.

Conclusion

The decline in the number of married and partnered young adults in Canada has implications for our country’s fertility rate. While many factors contribute to declining fertility, the trend is not likely to reverse if partnering continues to decline. Public policy can address economic issues that make family formation more difficult, and this deserves far more attention in Canada. There are limits to what policy can accomplish, however, and policymakers should be cautious about inadvertently intruding on important aspects of family well-being. We should begin by asking about the family life that young adults aspire to, and then seek to identify and address all of the barriers that keep them from achieving these aspirations.