Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Across Canada, people with disabilities experience significant disadvantages in the labour market. Despite decades of efforts by policy-makers to improve their access to work, employment rates for people with disabilities remain unacceptably low—and their risk of poverty is disproportionately high. In this paper, we take a closer look at the human costs of Canadians with disabilities’ exclusion from work and identify some of the key questions standing in the way of positive policy reform.

Three key assumptions inform our approach to this paper: (1) work is a fundamental human good to which all persons, including those with disabilities, should have access; (2) wherever possible, our social policy framework should be biased towards supporting work with its both monetary and non-monetary benefits; and (3) every person should receive a living wage, whether through private earnings, public income support, or some combination of the two. We review research showing that, for people with disabilities just as people without, work matters not only as a pathway to financial security but also as an important contributor to human well-being, both individual and social.

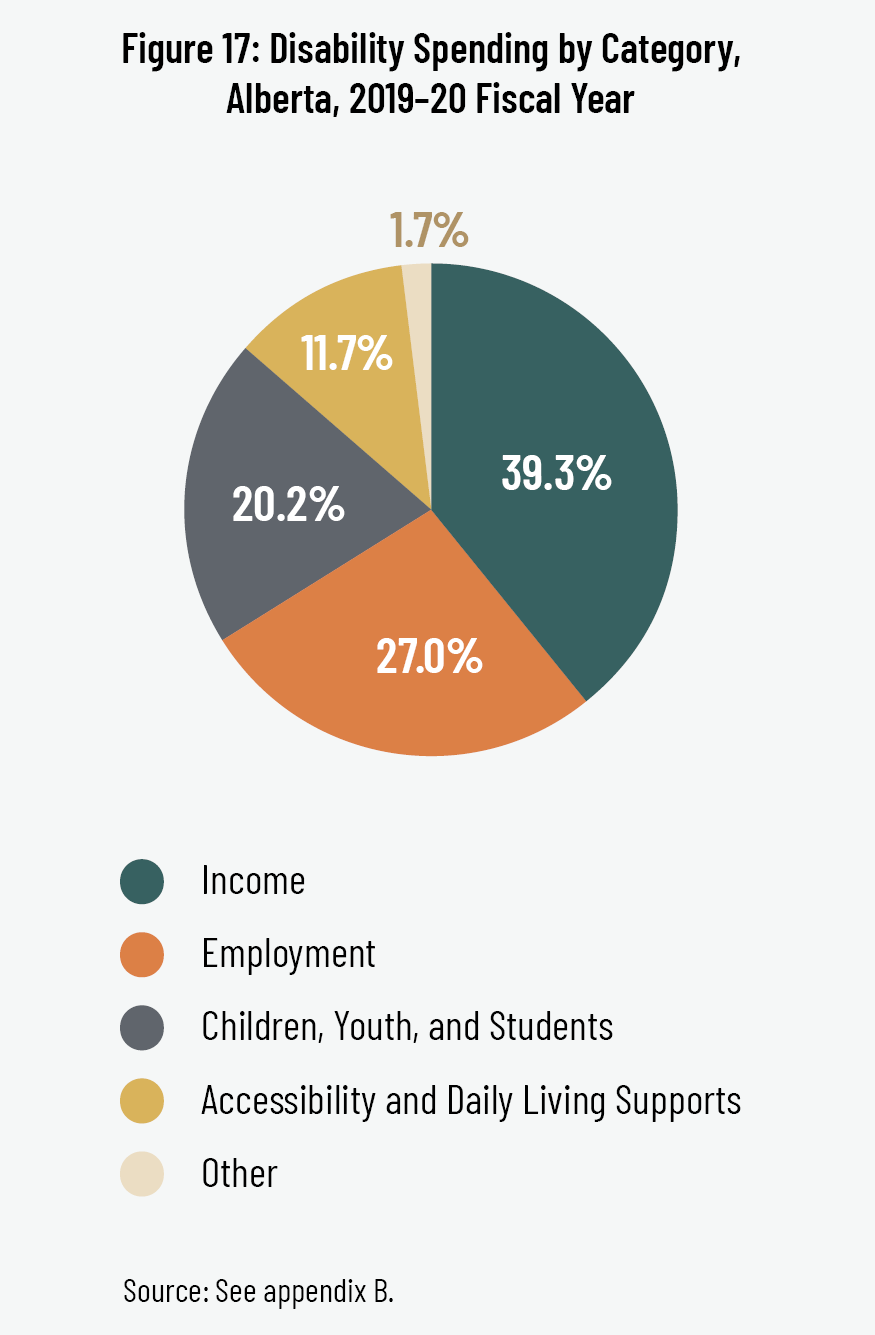

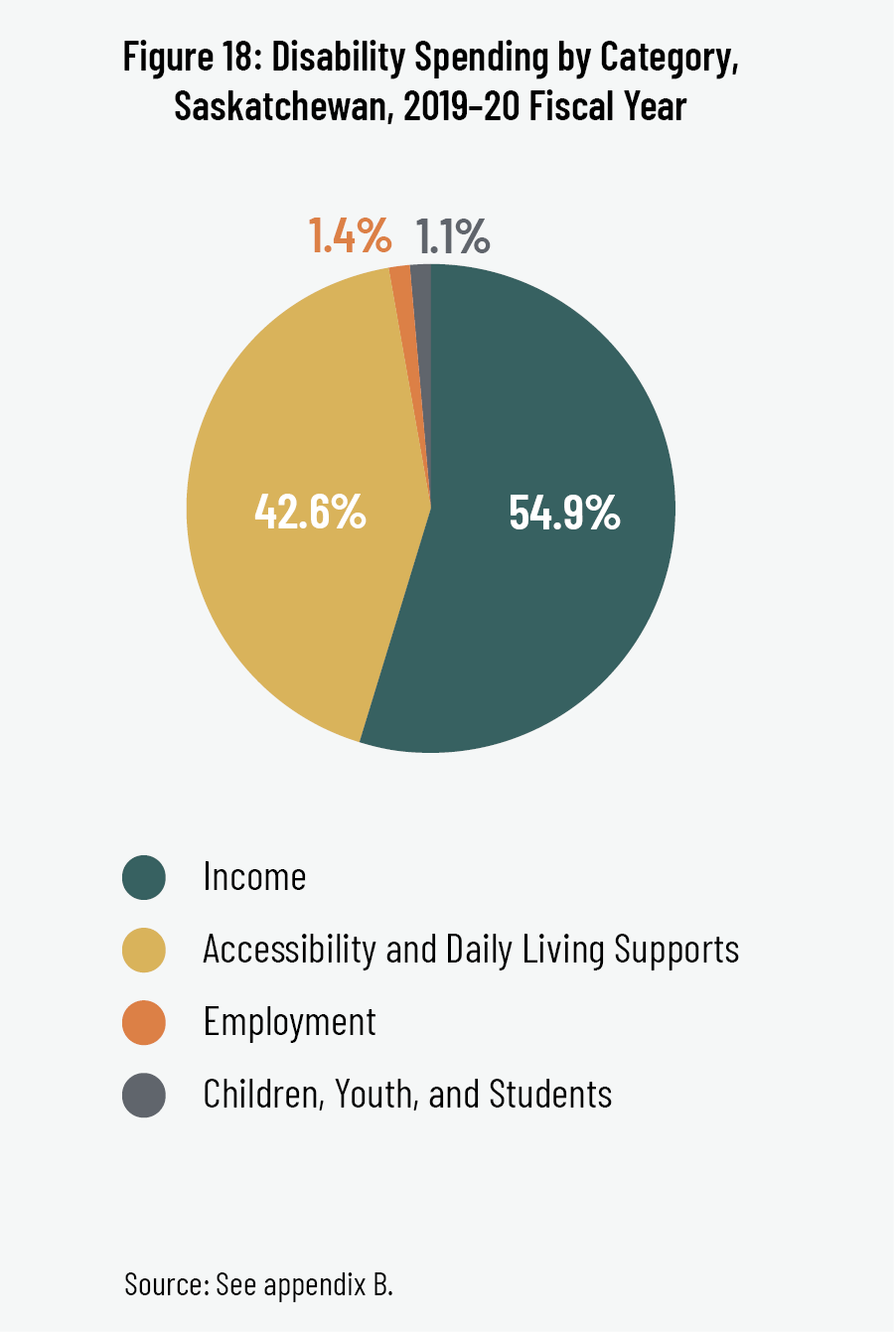

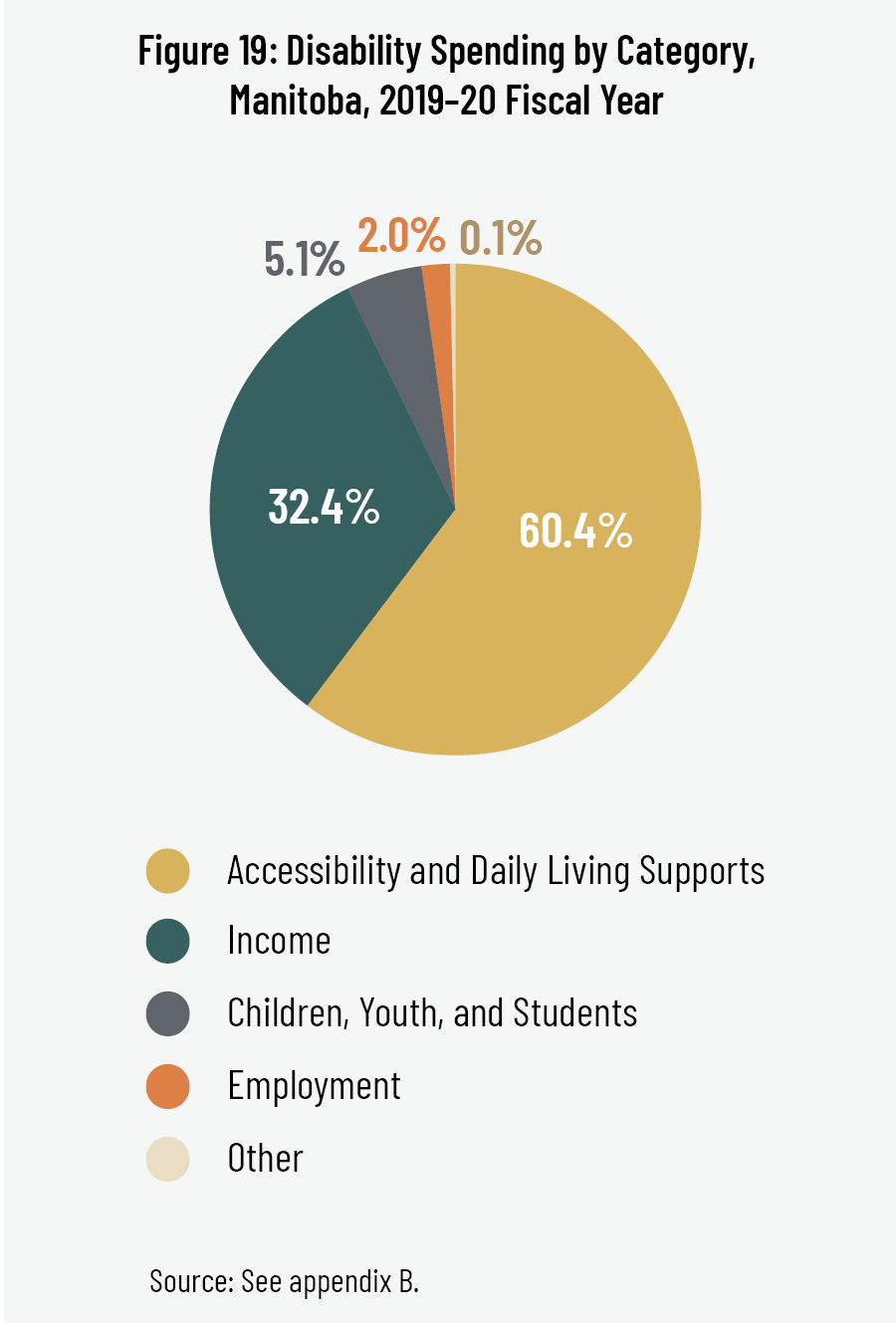

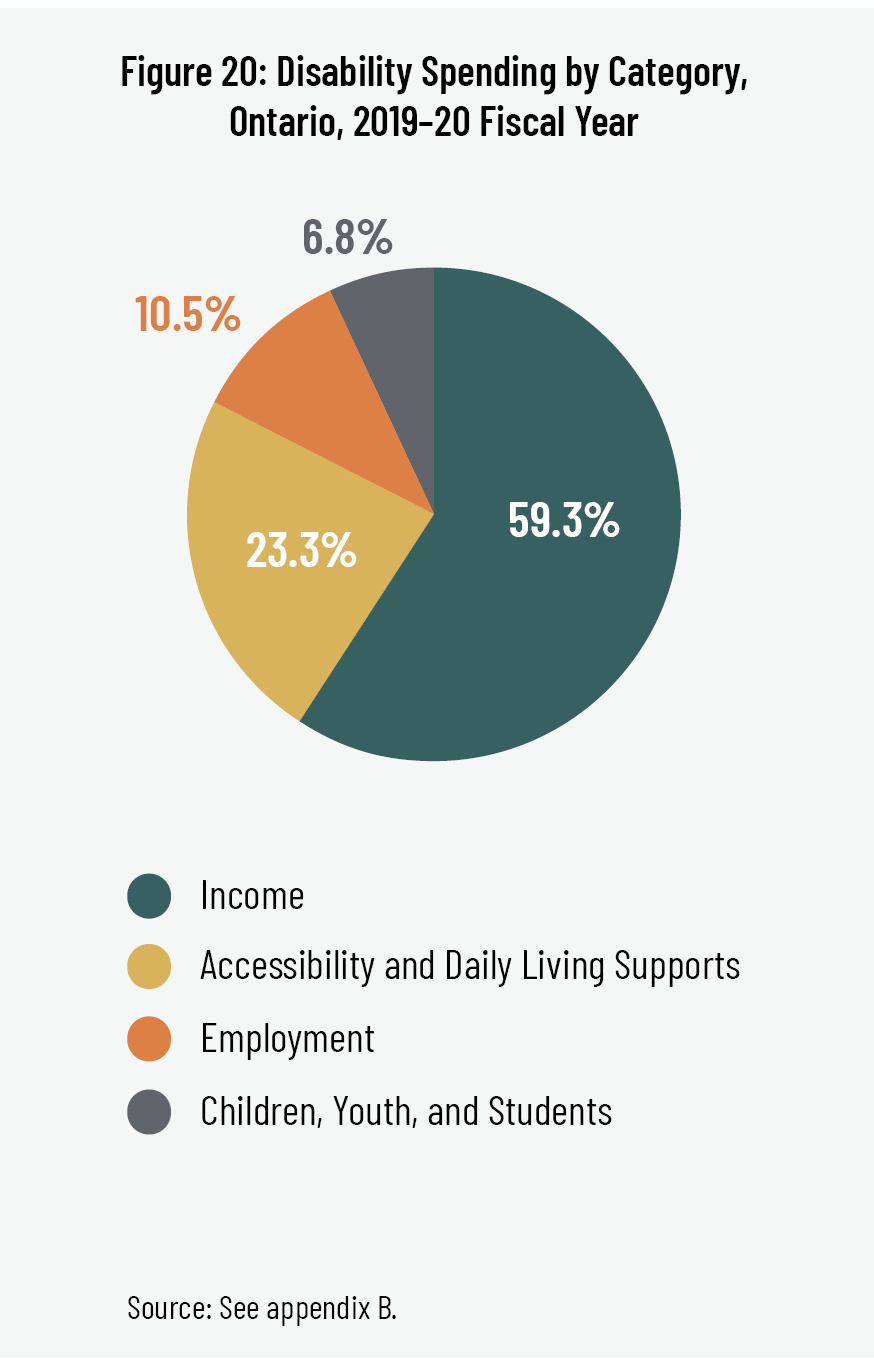

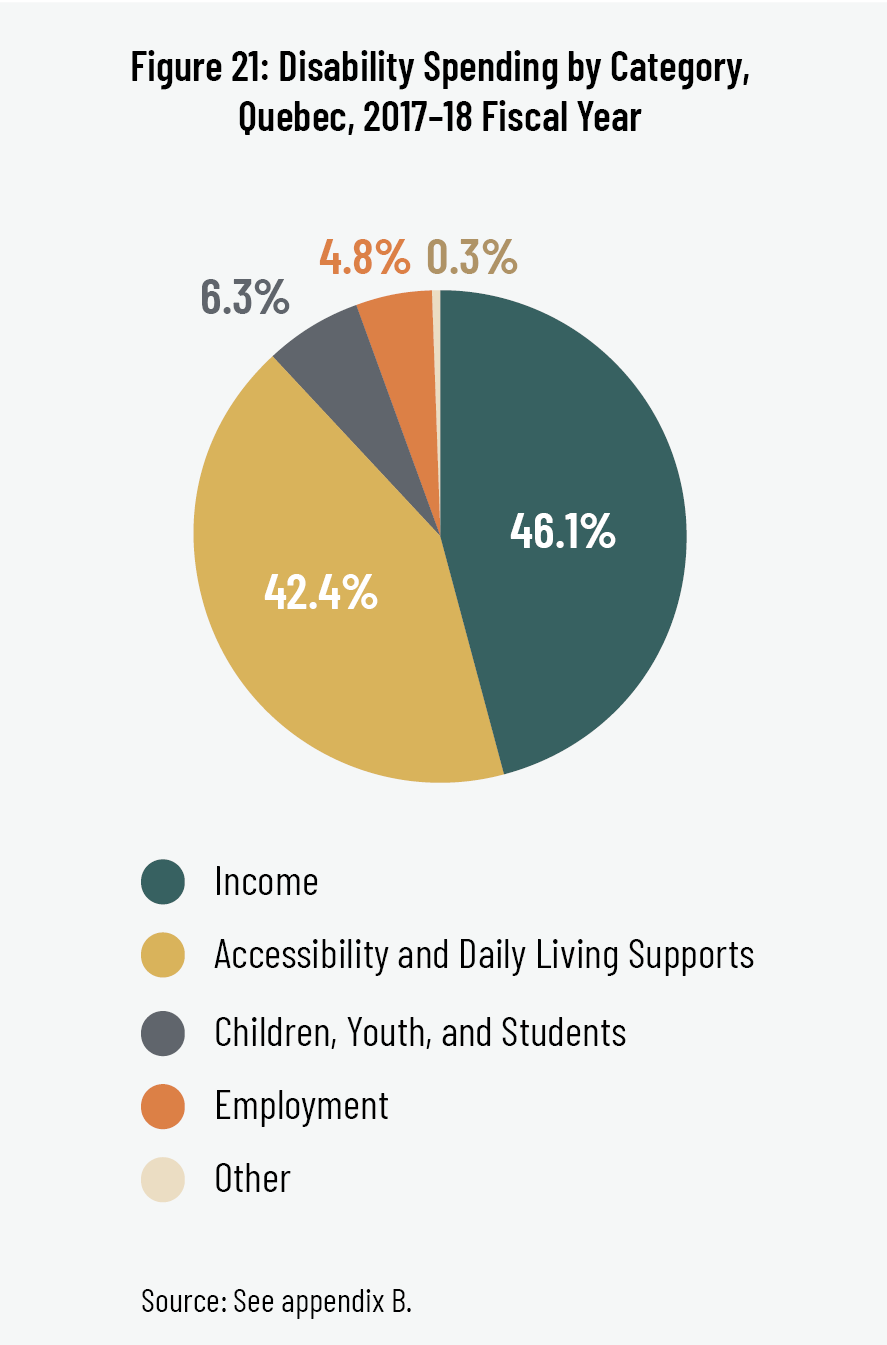

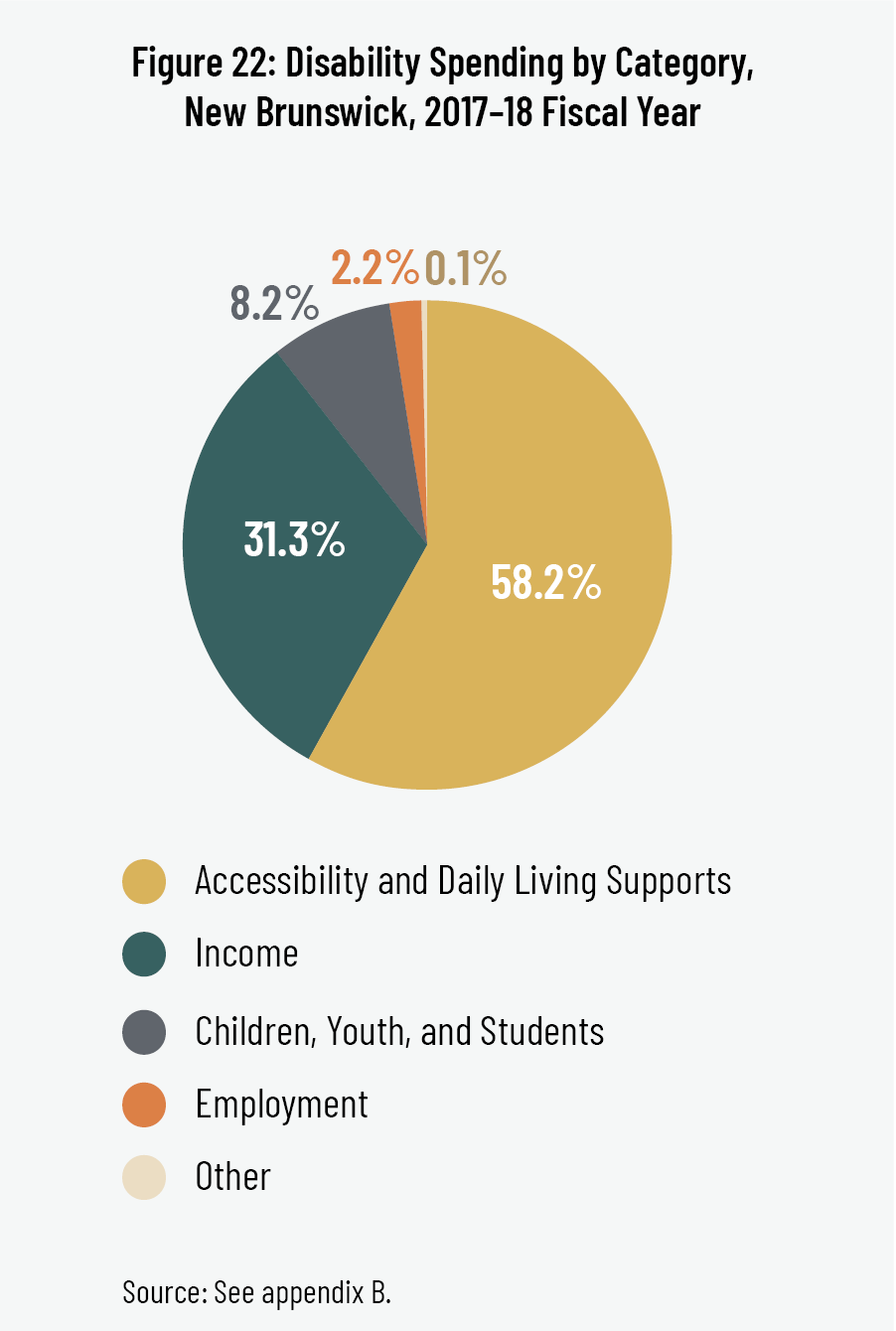

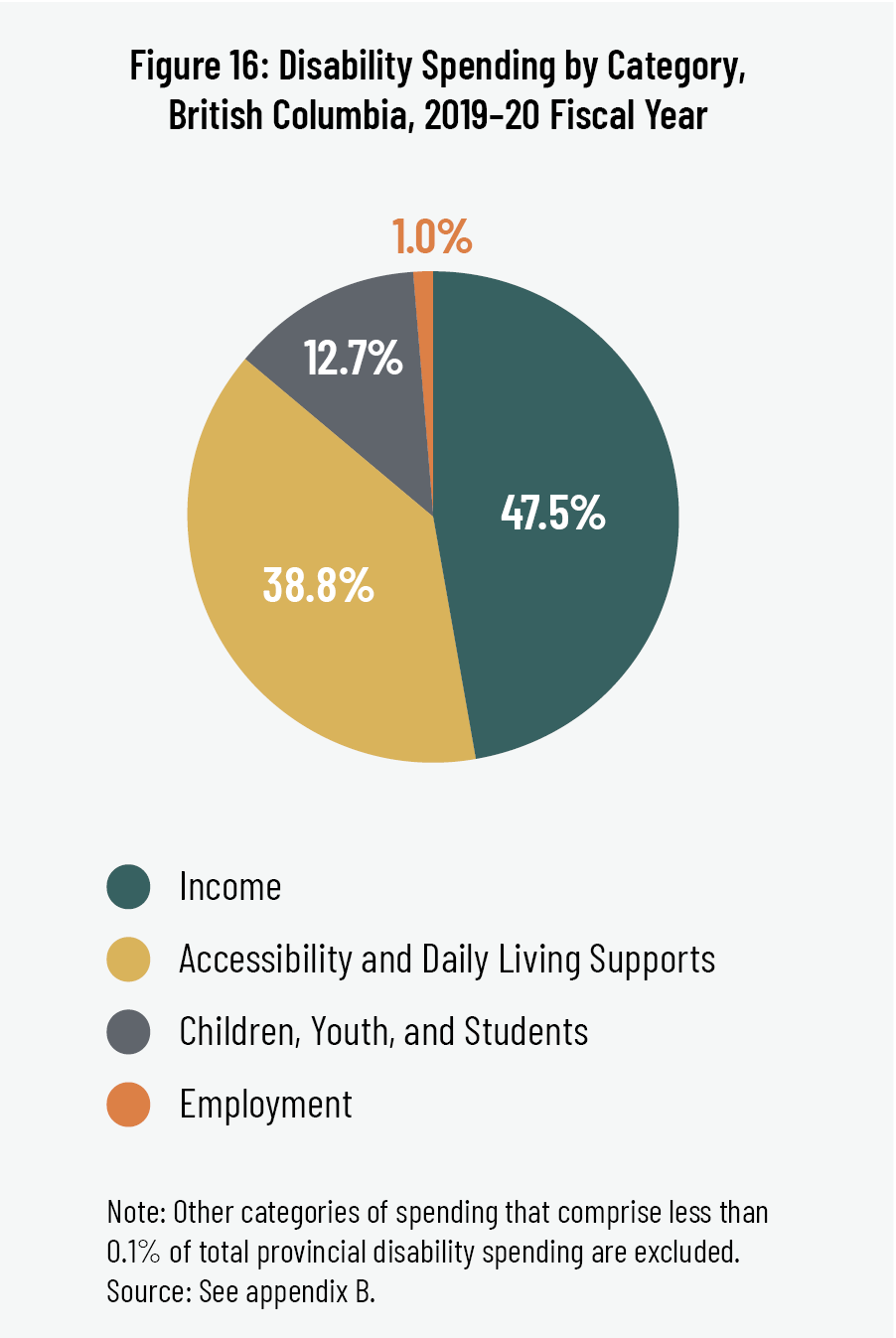

For the past several decades, policy-makers’ primary approach to people with disabilities’ exclusion from work has been to provide them with financial support. Unfortunately, this focus on standing in the income gap has not been matched by efforts to close the employment gap. Our review of federal and provincial disability-spending data for the 2019–20 fiscal year suggests that government expenditures on employment supports are dwarfed by income-assistance programs, even as poverty rates for people with disabilities remain inordinately high.

The goal toward which this paper aims is a work disability policy that recognizes and aligns with a holistic understanding of human needs—including but certainly not limited to financial security. To that end, we identify key questions relevant to disability-policy reform. We make no attempt to answer these questions here. Rather, our aim is to lay the groundwork for a productive conversation.

Introduction

Work has many non-financial benefits for people with disabilities, and most of these people are willing and able to participate in the labour market. For more than a decade, Canada has recognized work as a right for people with disabilities. However, many people with disabilities have been and continue to be excluded from meaningful employment. As a result, they have not only been excluded from the non-financial benefits of work, they also experience high levels of poverty. Policy-makers have spent decades trying to improve this situation, with little success. Employment rates remain stubbornly low for people with disabilities, while low-income rates remain stubbornly high.

In this paper, we review the benefits of work—both financial and non-financial—for people with disabilities. We then compare this research to the data on disability and employment, which reveals a troubling gap between these proven benefits of work, governments’ stated commitment to equality of opportunity in employment, and the reality of labour-market exclusion for many people with disabilities. The gap reflects a variety of barriers, not least the challenging complexity involved in designing, implementing, and evaluating effective pro-work disability policy. Our goal in this paper is to take a closer look at some of these barriers and to identify some of the key unanswered questions surrounding disability policy reform. Our approach is grounded in three central assumptions: (1) work is a fundamental human good to which all persons, including those with disabilities, should have access; (2) our social policy should be biased toward facilitating access to meaningful work and its both monetary and non-monetary benefits; and (3) every person should have secure access to a living wage that allows them to meet their basic needs with dignity—through employment earnings and/or government income support.

Our aim in this paper is not to give conclusive answers to the questions raised below. Instead, we seek to highlight some of the key work-disability policy issues raised by existing research, in the hope of stimulating further discussion. In other words, this paper is meant to be the start of a productive policy conversation—not by any means the final word.

Defining Disability

Any discussion of work-disability policy needs to begin with a clear definition of disability. Developments of the past half century are particularly important. In the late 1970s, disability advocates pushed for a fundamental change in the definition of disability. Disability, they argued, is distinct from impairment. While the latter concerns the physical or cognitive limitation of an individual, the former is properly understood as a matter of social exclusion: “[impairment] is individual and private, [disability] is structural and public.” 1 1 T. Shakespeare, “The Social Model of Disability,” in The Disability Studies Reader, ed. L.J. Davis (New York: Routledge, 2013), 216. Put another way, having an impairment—physical, mental, or otherwise—does not automatically lead to disability. Rather, disability emerges in environments that have been designed to serve the needs and capacities of people without (particular kinds of) impairments and therefore act as barriers to everyone else. Someone with impaired hearing, for instance, has limited capacity in a workplace where speaking and other audible sounds are the primary form of communication, but is not disabled at tasks in which no sound is involved, while mental illness may be a disability in a fast-paced workplace with high pressure and no scheduling flexibility for employees. 2 2 K. Vornholt et al., “Disability and Employment—Overview and Highlights,” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 27, no. 1 (2018): 42.

This new socio-environmental framework came to be known as the social model of disability and is now widely accepted over the impairment-centred medical model of disability. 3 3 M. Oliver, Social Work with Disabled People (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1983); M. Oliver, The Politics of Disablement (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1990); M. Oliver, “The Social Model of Disability: Thirty Years On,” Disability & Society 28, no. 7 (2013): 1024–26; C. Barnes, “Re-thinking Disability, Work and Welfare,” Sociology Compass 6, no. 6 (2012): 475–76. This paper follows the social model of disability and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health of the World Health Organization, which refers to disability as “the interaction between individuals with a health condition (e.g., cerebral palsy, Down syndrome and depression) and personal and environmental factors (e.g., negative attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social supports).” 4 4 World Health Organization, “Disability and Health,” November 24, 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health. See also the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: “Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” United Nations, “Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol,” article 1, https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convoptprot-e.pdf. The employment barriers faced by people with disabilities, then, are a matter not simply of individual impairments but of the social organization of the labour market. 5 5 S. Lindsay et al., “Improving the Participation of Under-utilized Talent of People with Physical Disabilities in the Canadian Labour Market: A Scoping Review,” Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, December 2013, 5; C. Barnes and G. Mercer, “Disability, Work, and Welfare: Challenging the Social Exclusion of Disabled People,” Work, Employment and Society 19, no. 3 (2005): 527–45.

Our Working Assumptions

As mentioned above, at the foundation of this paper are three basic assumptions informed by our prior beliefs about what it means to be human. Our primary motivation in advocating for policy reform is to align public policy with fundamental human needs. As we examine in more detail below, there is a glaring gap between the stated desires of most people with disabilities, Canada’s official recognition of their right to work, the many proven benefits of work, and the reality that people with disabilities experience: consistent, widespread exclusion from the labour market. Crucially, this gap comes at a severe human cost for Canadians with disabilities, denying them the dignity and benefits (both financial and non-financial) of work. It is clear that many people with disabilities want to work and have the capacity to do so, but the current system restricts rather than supports that capacity. What makes the employment gap faced by people with disabilities such a serious problem, in our view, is that our current policy framework is failing to uphold for all people a key aspect of human life.

Our three main working assumptions are explained below.

1. Work Is a Fundamental Human Good to Which All Persons Should Have Access.

What is work, and what is work for? As we review briefly in our previous paper, “Work Is About More Than Money,” this question has been answered in many different ways. 6 6 B. Dijkema and M. Gunderson, “Work Is About More Than Money: Toward a Full Accounting of the Individual, Social, and Public Costs of Unemployment, and the Benefits of Work,” Cardus, October 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/work-is-about-more-than-money/. Given that there are competing visions of the meaning, purpose, and implications of work, it is important that we begin by stating our framework for the concept of work and labour. All our research on work is shaped by our conviction that work is integral to human dignity; this paper is no exception. We believe work is an important part of life for all people, including those with disabilities. The significance of working for human well-being is supported by a wide body of research: working offers extensive non-monetary benefits—including social, psychological, and physical- and mental-health benefits—even independent of the income attached to having a job. 7 7 Dijkema and Gunderson, “Work Is About More Than Money.” As we examine at length in the following section, this finding holds true for people with disabilities as well. Moreover, participation in the open labour market is an important part of full participation in society as a whole, and disability advocates have long insisted that exclusion from paid employment is a major barrier to broader social integration. 8 8 D. Galer, “‘Hire the Handicapped!’ Disability Rights, Economic Integration and Working Lives in Toronto, Ontario, 1962–2005” (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2014). In 2010, Canada formally acknowledged the importance of work for people with disabilities when it ratified the United Nations Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which recognizes “the right of persons with disabilities to work, on an equal basis with others; this includes the right to the opportunity to gain a living by work freely chosen or accepted in a labour market and work environment that is open, inclusive and accessible to persons with disabilities.” 9 9 United Nations, “Convention,” article 27; S. Morris et al., “A Demographic, Employment and Income Profile of Canadians with Disabilities Aged 15 Years and Over, 2017,” Canadian Survey on Disability 2017, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-654-X2018002, November 28, 2018, 11, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-654-x/89-654-x2018002-eng.pdf?st=l_tCVByS.

2. Wherever Possible, Our Social-Policy Framework Should Be Biased Toward Supporting Work.

Given the many human benefits of work, our policies—including those that support Canadians with disabilities—should be designed to make access to work the first resort for those they support. We believe meaningful employment is the best source of income for all people, including those with disabilities, because of the research outlined below, but we by no means believe it should be the only (or even primary) source of income in every case. Short- and long-term cash benefits are an important source of income security for those who experience barriers to living-wage employment. Nevertheless, to rely exclusively on these programs means focusing only on the financial needs of people with disabilities and neglecting the other dimensions of human life and social inclusion. Employers and governments can both write cheques used to pay for rent or groceries, but a provincial income-support program cannot provide the many additional non-financial benefits a person stands to gain from working.

Wherever possible, financial incentives for all players in the disability-policy system must align with the stated desires of people with disabilities and the human need for work—that is, policy incentives must reward work in the open labour market over long-term cash benefits. Canadians with disabilities must be rewarded for working or seeking work. The employment system must make it a rewarding option for businesses—not a more difficult one—to hire people with disabilities and to retain workers who acquire a disability in the course of their careers. Employment service providers and the benefit system’s gatekeepers must be rewarded for upskilling workers and helping them find sustainable employment, discouraging assignment to long-term government-income support in all but the most exceptional cases (even though it may be easier and less time-consuming than personalized employment coaching, vocational training, and job placement support). 10 10 OECD, “Improving Social and Labour Market Integration of People with Disability,” Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers, 2010, 4, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/46488022.pdf. See also OECD, “Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers: Canada,” 2010, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264090422-en.

This pro-work orientation is important because work matters to human beings. People with disabilities should have—and have expressed the desire to have—access to the dignity, social inclusion, and other non-financial benefits a good job provides. If this approach also happens to offer long-term cost savings to governments, that would be an added bonus for public balance sheets. On the other hand, if the government needs to spend more on disability programs to make access to work possible, we believe the extra investment in the well-being of people with disabilities is well worth it.

3. Every Person Should Receive a Living Wage, Whether Through Private Earnings, Public Income Support, or Some Combination of the Two.

No person should be forced to live in poverty because of barriers to employment, and one of the proper responsibilities of the government is to provide income support to vulnerable groups to ensure they are able to meet their basic needs with dignity. Yet income-support programs have too often failed to provide liveable incomes to people with disabilities, who continue to be more likely than Canadians without disabilities to experience poverty. One of the goals of this paper has been to emphasize that money is not the only thing that matters, but that is by no means to say money doesn’t matter—it does, particularly for those who don’t have enough of it to get by.

Every Canadian, regardless of his or her disability status, should be able to meet their basic needs and live with dignity above the poverty line. Where working cannot provide a viable source of income, governments should be ready to stand in the gap. Yet employment earnings and government income support don’t need to be mutually exclusive—indeed, we believe cash-transfer programs can and should encourage and support recipients in working as much as they are able. The best policy framework, in our view, is one in which cash transfers supplement employment earnings where necessary to provide a stable, reliable, living wage.

Work Matters

Work offers much more than the opportunity to gain a living, however. The financial benefits of employment are important (especially for people with disabilities), but many years’ worth of research has made it clear that work is about more than money. 11 11 Dijkema and Gunderson, “Work Is About More Than Money.” Few studies on the non-monetary aspects of work focus specifically on workers with disabilities. In the literature on disability and work, economic outcomes have traditionally received more research attention than what one group of researchers describes as “the human experience of work” for people with disabilities. 12 12 A. Jahoda et al., “Feelings About Work: A Review of the Socio-emotional Impact of Supported Employment on People with Intellectual Disabilities,” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 21, no. 1 (2008): 2. Yet there is little reason to believe the non-monetary benefits of work (or negative consequences of unemployment) apply any less to people with disabilities, given that they “have the same needs and want similar things in their work as do non-disabled people.” 13 13 A. Akkerman, S. Kef, and H.P. Meininger, “Job Satisfaction of People with Intellectual Disabilities: The Role of Basic Psychological Need Fulfillment and Workplace Participation,” Disability and Rehabilitation 40, no. 10 (2018): 1–2. Indeed, researchers have found that those with disabilities and those without disabilities perceive the same benefits of work. 14 14 B. Kirsh et al., “From Margins to Mainstream: What Do We Know About Work Integration for Persons with Brain Injury, Mental Illness and Intellectual Disability?,” Work 32, no. 4 (2009): 394.

Work has a positive psychological impact on the worker. This finding has been well-established in research on the general population, 15 15 See Dijkema and Gunderson, “Work Is About More than Money,” for a review of this literature. and though far fewer studies have specifically considered people with disabilities, the existing evidence suggests that the finding holds true among this group as well. A review of the research on supported employment for workers with intellectual disabilities, for example, found that work was associated with increased quality of life, well-being, autonomy, and self-esteem, as well as with lower levels of depression. 16 16 Jahoda et al., “Feelings About Work.” Work offers the opportunity for personal growth. 17 17 Akkerman, Kef, and Meininger, “Job Satisfaction of People with Intellectual Disabilities,” 1. A number of studies have established links between employment and improved quality of life for people with disabilities, especially when work outcomes are positive. 18 18 E. Cocks, S.H. Thoreson, and E.A.L. Lee, “Pathways to Employment and Quality of Life for Apprenticeship and Traineeship Graduates with Disabilities,” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 62, no. 4 (2015): 422–37; H. Memisevic et al., “Predictors of Quality of Life in People with Intellectual Disability in Bosnia and Herzegovina,” International Journal on Disability and Human Development 15, no. 3 (2016): 299–304; R. Forrester-Jones et al., “Supported Employment: A Route to Social Networks,” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 17, no. 3 (2004): 199–208; S. Beyer et al., “A Comparison of Quality of Life Outcomes for People with Intellectual Disabilities in Supported Employment, Day Services and Employment Enterprises,” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 23, no. 3 (2010): 290–95; C.J. Van Dongen, “Quality of Life and Self-Esteem in Working and Nonworking Persons with Mental Illness,” Community Mental Health Journal 32, no. 6 (1996): 535–548, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8905226/. While much of the research has focused on paid employment, this is not the only type of work. Evidence suggests that working in other productive social roles, such as volunteering or working at home, is also linked to subjective well-being for people with disabilities. 19 19 A. Haigh et al., “What Things Make People with a Learning Disability Happy and Satisfied with Their Lives: An Inclusive Research Project,” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 26, no. 1 (2013): 26–33; R. Lysaght et al., “Inclusion Through Work and Productivity for Persons with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities,” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 30, no. 5 (2017): 922–35. Losing a job (which may be a greater risk for people with disabilities given their overrepresentation in entry-level jobs with higher turnover rates), meanwhile, can be traumatic. 20 20 P. Banks et al., “Supported Employment for People with Intellectual Disability: The Effects of Job Breakdown on Psychological Well-Being,” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 23, no. 4 (2010): 344–54.

Work offers many social benefits. Though employment does not automatically guarantee new positive social relationships for people with disabilities, workplaces do offer an opportunity for social interaction and forging new connections. 21 21 Forrester-Jones et al., “Supported Employment.” Work thus has the potential to reduce loneliness and social isolation, which are experienced at higher rates among people with disabilities. 22 22 Vornholt et al., “Disability and employment,” 41; Angus Reid Institute, “A Portrait of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Canada Today,” June 17, 2019, https://angusreid.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019.06.14_Loneliness-and-Social-Isolation-Index.pdf; L. Schur, “The Difference a Job Makes: The Effects of Employment Among People with Disabilities,” Journal of Economic Issues 36, no. 2 (2002): 340. Jahoda et al., for example, note that “relationships at work have also been found to be significant for people with intellectual disabilities, with a link between social relationships and QOL [quality of life] in people with intellectual disability.” 23 23 Jahoda et al., “Feelings About Work,” 2. In addition, as disability advocates have long argued, employment is an important component of greater societal participation and inclusion. 24 24 Schur, “The Difference a Job Makes,” 339. One study found a correlation between employment and a higher rate of participation in groups for people with disabilities. Notably, the positive effect of employment on group participation did not extend to people without disabilities, “indicating that the lack of employment is more isolating for people with disabilities.” 25 25 Schur, “The Difference a Job Makes,” 344. Social integration at work can create a positive feedback loop: employees with (and without) disabilities who are able to participate in their workplaces not only are more likely to feel like accepted and valued members of the team but also increase their chances of succeeding at their jobs (both in terms of tenure and performance); 26 26 Akkerman, Kef, and Meininger, “Job Satisfaction of People with Intellectual Disabilities,” 3. this in turn promotes further participation in the workplace community. Perceived social support from supervisors and co-workers has also been linked to a higher quality of working life for employees with disabilities. 27 27 N. Flores et al., “Understanding Quality of Working Life of Workers with Intellectual Disabilities,” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 24, no. 2 (2011): 133–141.

The benefits of work extend not simply to people with disabilities but to their families as well. Researchers have found evidence that working outside the home can lead to a greater satisfaction with home life for people with disabilities 32 32 Forrester-Jones et al., “Supported Employment.” and increased quality of life for their families. 33 33 Jahoda et al., “Feelings About Work,” 10. One study found that families of young adults with intellectual disabilities who worked in open employment reported higher quality of life, even though hours worked could be quite small. 34 34 K.R. Foley et al., “Relationship Between Family Quality of Life and Day Occupations of Young People with Down Syndrome,” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 49, no. 9 (2014): 1460, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24414088/. Though a somewhat small sample size means results should be interpreted with caution, the authors stressed the importance of these findings: “The young people we categorised as attending open employment may have spent as little as 2 h a week in open employment, supplementing this time with attendance at other day occupations. Therefore, a small amount of time in open employment was associated with better family quality of life.” 35 35 Foley et al., “Family Quality of Life and Day Occupations,” 1460. The positive effects of work and family can amplify each other: research has demonstrated that the support of families—in transitioning from school to the workforce, in job searching, in providing practical advice and encouragement—plays an important role in getting people with disabilities into the labour force and affects employment outcomes, including by mediating other employment supports. 36 36 M. Donelly et al., “The Role of Informal Networks in Providing Effective Work Opportunities for People with an Intellectual Disability,” Work 36, no. 2 (2010): 228; Kirsh et al., “From Margins to Mainstream,” 396; see also Holwerda et al., “Predictors of Work Participation,” 118, 124; Foley et al., “Family Quality of Life and Day Occupations,” 1456. Researchers have documented improved outcomes for both children with disabilities and their families when these families have access to better resources and higher incomes. 37 37 Foley et al., “Family Quality of Life and Day Occupations,” 1463; C. Cunningham, “Families of Children with Down Syndrome,” Down Syndrome Research and Practice 4, no. 3 (1996): 87–95, https://doi.org/10.3104/perspectives.66. This evidence underscores the important link between support for families and support for people with disabilities—disability policy should not be separated from family policy.

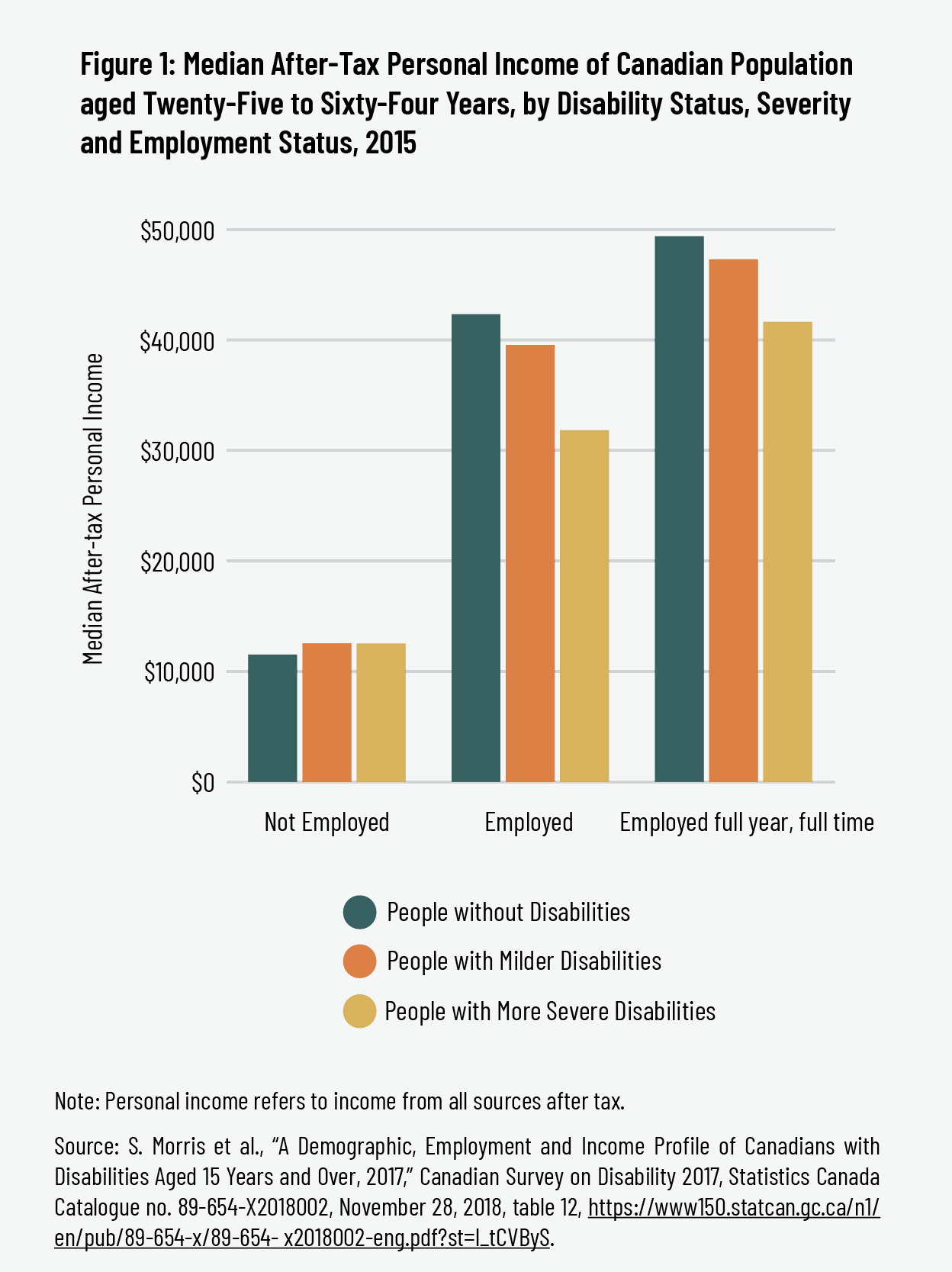

Work, of course, also offers financial benefits for persons with disabilities—benefits that may be even more pronounced than they are for those without disabilities. One study estimated that despite lower average earnings among persons with disabilities, employment raised household income levels by 49 percent, compared to just 13 percent for those without disabilities. The same study also found that employment had a larger effect on a person with disabilities’ likelihood of escaping poverty, lowering poverty rates by 20 percent among the population with disabilities compared to 17 percent among the population without. 38 38 Schur, “The Difference a Job Makes,” 343–44.

The financial consequences of labour-market exclusion, meanwhile, have been devastating for the disability community. People with disabilities are far more likely to experience poverty and have lower levels of household income, 39 39 Vornholt et al., “Disability and Employment,” 40; Schur, “The Difference a Job Makes,” 340. and most of this vulnerability is due to low employment rates.

Not only are working-age Canadians with disabilities twice as likely as Canadians without disabilities to live below the poverty line, but also poor people with disabilities have lower average incomes than poor Canadians without disabilities. Given the employment barriers experienced by Canadians with disabilities, it is unsurprising that the largest share of these Canadians’ incomes comes from social assistance. 40 40 C. Crawford, “Looking into Poverty: Income Sources of Poor People with Disabilities in Canada,” Institute for Research and Development on Inclusion and Society (IRIS) and Council of Canadians with Disabilities, 2013, i, http://www.ccdonline.ca/media/socialpolicy/Income%20Sources%20Report%20IRIS%20CCD.pdf. Government transfers make up nearly two-thirds (65.2 percent) of income for working-age poor people with disabilities, with just over a third coming from private-market sources (34.8 percent). 41 41 Crawford, “Looking into Poverty,” 1. Working-age Canadians who live above the poverty line and do not have disabilities, in contrast, receive nearly all of their income (94.8 percent) from private-market sources such as wages, salaries, and self-employment, rather than from government transfers. Even if Canadians without disabilities were poor, they still earned 71.4 percent of their income from market sources. 42 42 Crawford, “Looking into Poverty,” 9. For Canadians experiencing disability and poverty, government income support has come to function not as a safety net or stopgap measure to hold them over until they can return to the workforce, but rather as a long-term income replacement system 43 43 Crawford, “Looking into Poverty,” 36. —a system that can (and in many cases does) act as a barrier to work. It is encouraging that Canadians with disabilities have seen some improvement in their financial status in the past three decades—Fang and Gunderson found that poverty rates declined somewhat from 1993 to 2010; 44 44 T. Fang and M. Gunderson, “Poverty Dynamics Among Marginal Groups in Canada: Longitudinal Analysis Based on SLID 1993–2010” (paper presented at the IRPP-CLSRN Conference, Inequality in Canada: Driving Forces, Outcomes and Policy, Ottawa, Ontario, February 24–25, 2014), http://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/Uploads/fang.pdf. more recently, Statistics Canada reported that the poverty rate of people with disabilities fell from 20.7 percent in 2015 to 13.5 percent in 2019. 45 45 Employment and Social Development Canada, “Over 1.3 Million Canadians Lifted Out of Poverty Since 2015 According to the 2019 Canadian Income Survey,” March 24, 2021, https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2021/03/canadian-income-survey-2019.html. The reason for this seven-point drop is unclear. However, the persistence of unemployment and disproportionate levels of poverty for this group remain pressing policy concerns.

The Employment Characteristics of and Labour-Force Challenges Facing People with Disabilities

Given the many proven benefits of work, it should come as no surprise that most people with disabilities say they want to work. 46 46 Lindsay et al., “Participation of Under-utilized Talent,” 5; Kessler Foundation, “2015 National Employment & Disability Survey: Executive Summary,” 2015, https://kesslerfoundation.org/sites/default/files/filepicker/5/KFSurvey2015_ExecutiveSummary.pdf. While Canadian data is limited, surveys from the United States suggest the majority of non-employed working-age adults with disabilities would prefer to be employed. 47 47 S. Bonaccio et al., “The Participation of People with Disabilities in the Workplace Across the Employment Cycle: Employer Concerns and Research Evidence,” Journal of Business and Psychology 35, no. 2 (2020): 144–51; C.S. Hunt and B. Hunt, “Changing Attitudes Toward People with Disabilities: Experimenting with an Educational Intervention,” Journal of Managerial Issues 16, no. 2 (2004): 267. The 2004 National Organization on Disability/Harris Survey, for example, reported that nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of unemployed Americans with disabilities said they would rather be working. 48 48 National Organization on Disability/Harris Polls, NOD-Harris Survey of Americans with Disabilities (Washington, DC: National Organization on Disability, 2004). More recently, Ali, Schur, and Blanck analyzed responses to the General Social Survey, a representative national survey of American adults, and found “almost no difference between people with and without disabilities in the desire for paid work. Four-fifths (80 percent) of non-employed people with disabilities would like a job now or in the future, compared to 78 percent among the non-disabled.” 49 49 M. Ali, L. Schur, and P. Blanck, “What Types of Jobs Do People with Disabilities Want?,” Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 21, no. 2 (2011): 202. The study also notes that non-employed people with a disability are more than twice as likely as their counterparts without a disability (42 percent vs. 20 percent) to say that they would prefer to spend “much more” time in paid work. 50 50 Ali, Schur, and Blanck, “What Types of Jobs,” 204. Other studies have since added further evidence that “people with and without disabilities attach the same significance to work-related outcomes such as job security, income, promotion opportunities, having an interesting job, and having a job that contributes to society.” 51 51 Bonaccio et al., “Participation of People with Disabilities in the Workplace,” 144. Research examining the experience of adults with intellectual disabilities, for instance, has found that they have the same preference for employment over unemployment—and for paid work over unpaid work—as their counterparts without disabilities. 52 52 Kirsh et al., “From Margins to Mainstream,” 394; R. Lysaght, H. Ouellette-Kuntz, and CJ. Lin, “Untapped Potential: Perspectives on the Employment of People with Intellectual Disability,” Work (Reading, Mass.) 41, no. 4 (2012): 409; Holwerda et al., “Predictors of Work Participation,” 1983.

Contrary to misconceptions and stereotypes, moreover, most people with disabilities have a strong capacity for employment. Though disability by definition includes barriers inhibiting full participation, many employees with disabilities have no trouble matching the work capacities of their counterparts without disabilities when provided with the appropriate accommodations. Many more have at least partial work capacity, and for some, the reduction in capacity is only temporary. 53 53 International Labour Organization (ILO) and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Labour Market Inclusion of People with Disabilities” (paper presented at the first meeting of the G20 Employment Working Group, Buenos Aires, Argentina, February 20–22, 2018), 15, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_646041.pdf According to the Canadian Survey on Disability, three in five (59 percent) working-age Canadians with disabilities were employed in 2017. The survey also estimated that of people with disabilities who were not working (or in school), nearly 645,000 people (39 percent of unemployed people with disabilities) had the potential to work. 54 54 Morris et al., “A Demographic, Employment and Income Profile,” 11–14. This means that three in four (76 percent) people with disabilities—the overwhelming majority—have the capacity to work.

Despite strong work potential and several decades’ worth of government initiatives to encourage their integration into the labour force, people with disabilities continue to be “disproportionately disadvantaged in the labour market.” 55 55 Barnes, “Re-thinking Disability, Work and Welfare,” 7; D. Mont, “Disability Employment Policy,” Social Protection Discussion Paper Series No. 0413, Social Protection Unit, Human Development Network, The World Bank, July 2004, 7–10; Kirsh et al., “From Margins to Mainstream,” 392; Burge, Oullette-Kuntz, and Lysaght, “Public Views on Employment of People with Intellectual Disabilities,” 29. Across OECD countries, people with disabilities experience employment rates that are 40 percent lower than the overall average and double the average unemployment rate. 56 56 OECD, Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers (2010), 10, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264088856-en. Nationally, the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability reports that among working-age adults, 59 percent of Canadians with a disability were employed compared to 80 percent of those not reporting a disability (a gap that widens dramatically when considering severity of disability, as we discuss below). 57 57 Morris et al., “A Demographic, Employment and Income Profile,” 11–14. Though many developed countries have passed legislation in the past few decades aimed at increasing employment of people with disabilities—often through prohibiting employer discrimination and requiring the provision of workplace accommodations—employment rates for people with disabilities have barely budged since the 1980s. 58 58 I. Duvdevany, K. Or-Chen, and M. Fine, “Employers’ Willingness to Hire a Person with Intellectual Disability in Light of the Regulations for Adjusted Minimum Wages,” Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 44, no. 1 (2016): 34.

Even when people with disabilities are able to enter the labour market, research consistently finds that people with disabilities “work less, earn less, and earn lower wages when they do work.” 59 59 T. DeLeire, “The Wage and Employment Effects of the Americans with Disabilities Act,” The Journal of Human Resources 35, no. 4 (2000): 698. Their employment disadvantages include

- fewer hours and lower wages; 60 60 L. Schur et al., “Disability at Work: A Look Back and Forward,” Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 27, no. 4 (2017): 482–97; L. Schur, “Dead End Jobs or a Path to Economic Well Being? The Consequences of Non-standard Work Among People with Disabilities,” Behavioural Sciences and the Law 20, no. 6 (2002): 601–20; R. Haveman and B. Wolfe, “The Economics of Disability and Disability Policy,” in Handbook of Health Economics 1 (2000): 1008; M.K. Jones, “Disability and the Labour Market: A Review of the Empirical Evidence,” Journal of Economic Studies 35, no. 5 (2008): 408; Vornholt et al., “Disability and Employment,” 45.

- disproportionate employment in part-time, seasonal, contract-based, and precarious jobs; 61 61 D. Kruse et al., “Why Do Workers with Disabilities Earn Less? Occupational Job Requirements and Disability Discrimination,” British Journal of Industrial Relations 56, no. 4 (2018): 798–834; Lysaght, Ouellette-Kuntz, and Lin, “Untapped Potential”; Lindsay et al., “Participation of Under-utilized Talent”; Holwerda et al., “Predictors of Work Participation”; Schur, “Dead End Jobs.” Some researchers suggest that the reason for the disproportionate prevalence of part-time work among employees with disabilities is flexibility in work schedules required by many of these workers. Other researchers note that while flexible or modified hours are a common accommodation requirement for employees with disabilities, these workers may have preferred full-time work if it had been available to them. See Jones, “Disability and the Labour Market,” 412; L. Schur, “Barriers or Opportunities? The Causes of Contingent and Part‐Time Work Among People with Disabilities,” Industrial Relations 42, no. 4 (2003): 589–622; Bonaccio et al., “Participation of People with Disabilities in the Workplace,” 144.

- greater likelihood of holding entry-level positions with fewer opportunities for professional or economic advancement; 62 62 Holwerda et al., “Predictors of Work Participation,” 1983; Kirsh et al., “From Margins to Mainstream,” 398; H.S. Kaye, “Stuck at the Bottom Rung: Occupational Characteristics of Workers with Disabilities” Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 19, no. 2 (2009): 115. and

- higher risk of involuntary job loss and being laid off during recessions. 63 63 S. Mitra and D. Kruse, “Are Workers with Disabilities More Likely to Be Displaced?,” International Journal of Human Resource Management 27, no. 14 (2016): 1550–79; H.S. Kaye, “The Impact of the 2007–2009 Recession on Workers with Disabilities,” Monthly Labor Review 133, no. 10 (2010): 19–30; Haveman and Wolfe, “The Economics of Disability and Disability Policy,” 1008.

Beneath these general barriers lies substantial diversity in labour-market participation, employment outcomes, and income related to the type of disability and especially the severity of disability. Though research often compares those with disabilities to those without, the heterogeneity of the population experiencing disability means there are limits to how useful these binary distinctions can be. It is at least equally as important to examine differences within the disability community, such as the nature, severity, and timing of the disability, as well as demographic factors. 64 64 Jones, “Disability and the Labour Market,” 417. Several studies have found worse labour-market outcomes for those who acquired disability in adulthood. 65 65 Jones, “Disability and the Labour Market,” 413. Unsurprisingly, those whose disabilities severely limit their activities are more likely to be unemployed, 66 66 Schur, “The Difference a Job Makes,” 342. and job retention and income are lower for those with more severe disabilities. 67 67 Jahoda et al., “Feelings About Work,” 2; Banks et al., “Supported Employment for People with Intellectual Disability,” 345. People with intellectual disabilities have the lowest labour-market participation compared to those with other disabilities (such as musculoskeletal or sensory), 68 68 A. Khayatzadeh-Mahani et al., “Prioritizing Barriers and Solutions to Improve Employment for Persons with Developmental Disabilities,” Disability and Rehabilitation 42, no. 19 (2020): 2696; Kirsh et al., “From Margins to Mainstream,” 392. are more likely to work in sheltered workshops or other segregated work settings, 69 69 Holwerda et al., “Predictors of Work Participation,” 117. and have a relatively high level of job breakdown. 70 70 Banks et al., “Supported Employment for People with Intellectual Disability,” 345. Women with disabilities work fewer hours, earn less income, and are at a substantially higher risk of poverty than men. 71 71 Jahoda et al., “Feelings About Work,” 2; D. Galer, “Life and Work at the Margins: (Un)employment, Poverty, and Activism in Canada’s Disability Community Since 1966,” Centre for Research on Work Disability Policy, April 2016, 6, https://www.crwdp.ca/sites/default/files/Research%20and%20Publications/life_and_work_at_the_margins.pdf.

This diversity is clear in labour-market data for Canadians with disabilities. For instance, the employment gap between those without disabilities and those with mild disabilities is dwarfed by the gap between mild and severe disabilities. According to the 2017 Canadian Survey on Disability (CSD), 76 percent of working-age Canadians with mild disabilities were employed (a number very close to the overall population, which had an employment rate of 80 percent). Among those with severe disabilities, however, the employment rate fell to 31 percent, about two and a half times less than the overall population. 72 72 The Canadian Survey on Disability uses four classes of disability severity in its data analysis: mild, moderate, severe, and very severe. These levels are “calculated for each person using the number of disability types that a person has, the level of difficulty experienced in performing certain tasks, and the frequency of activity limitations.” Morris et al., “A Demographic, Employment and Income Profile.” 7. Canadians with severe disabilities were also at a higher risk of poverty, being twice as likely as those with milder disabilities (28 percent vs. 14 percent)—and almost three times as likely as those without disabilities (10 percent)—to live below the poverty line. 73 73 Morris et al., “A Demographic, Employment and Income Profile.” Age matters as well: younger and middle-aged adults with milder disabilities resemble those without disabilities in terms of employment, with around eight in ten Canadians aged twenty-five to fifty-four employed across both groups. 74 74 Morris et al., “A Demographic, Employment and Income Profile.” 11. Research suggests the age of onset is another significant predictor of employment. Those who become disabled during their working years are more likely to be employed (especially if they get back into the labour market soon after acquiring their disability), in large part because they have work history and experience. 75 75 M.J. Prince, “Inclusive Employment for Canadians with Disabilities: Toward a New Policy Framework and Agenda,” IRPP Study No. 60, Institute for Research on Public Policy, August 2016, 4, https://irpp.org/research-studies/inclusive-employment-for-canadians-with-disabilities/. Labour-market participation also varies by type of disability. Intellectual or developmental disabilities are associated with lower employment rates: half of those with a disability related to pain or hearing are employed, for example, but only a quarter of those with cognitive disabilities. 76 76 Prince, “Inclusive Employment for Canadians with Disabilities,” 5. As these data make clear, no two Canadians experience disability in the same way, and no single policy can address the diverse labour-market barriers Canadians with disabilities face.

Common Good: The Shared Benefits of Employment Inclusion

Taken together, these employment data point to a glaring gap between the stated desires of most people with disabilities, the many proven benefits of work, Canada’s public recognition of the “right of persons with disabilities to work, on an equal basis with others,” and the reality that people with disabilities experience: consistent, widespread exclusion from the labour market. This gap does not necessarily reflect a lack of concern on the part of governments, businesses, or individuals, but rather points to the complexity of the barriers involved. Crucially, this gap comes at a severe human cost for Canadians with disabilities, denying them the dignity and benefits of work. It is clear that many people with disabilities want to work and have the capacity to do so, but the current system restricts rather than supports that capacity. The driving motive behind this paper’s focus on employment is to identify barriers that stand in the way of a policy framework more aligned with human needs and desires: to allow people who are ready, willing, and able to participate in the labour market to have access to the financial and non-financial benefits of work.

Everyone—not just people with disabilities themselves—can benefit from a more inclusive workforce. Businesses, for example, have much to gain from hiring applicants with disabilities. The business case for inclusive employment has been made by disability-advocacy organizations across Canada, including Hire for Talent; 77 77 Hire for Talent, “Employer Toolkit: Business Case,” https://hirefortalent.ca/main/toolkit/business-case. Ready, Willing and Able, of Inclusion Canada and Canadian Autism Spectrum Disorder Alliance; 78 78 Ready, Willing and Able, “Inclusive Hiring Works: The Business Benefits of Hiring People with an Intellectual Disability or Autism Spectrum Disorder,” https://readywillingable.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/RWA-Business-Case_EN_October-2019.pdf; Ready, Willing and Able, “Business Case: Hiring People with Intellectual Disabilities or Autism Spectrum Disorder,” https://inclusioncanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/RWA_BusinessCase_FactSheet_FA_WEB.pdf. the Canadian Disability Participation Project and the Work Wellness Institute; 79 79 Canadian Disability Participation Project, “Mythbusting: Employees with Disabilities,” 2020, https://cdpp.ca/sites/default/files/CDPP%20Mythbusting%20Final.pdf; S. Bonaccio and M. Haan, “The Case for Hiring People with Disabilities in the Workplace—What Are the Myths and What Does the Research Show?,” Work Wellness Institute, December 10, 2019, https://workwellnessinstitute.org/the-case-for-hiring-people-with-disabilities-in-the-workplace-what-are-the-myths-and-what-does-the-research-show-2/. the Canadian Council on Rehabilitation and Work; 80 80 Canadian Council on Rehabilitation and Work, “The Business Case for Hiring Persons with Disabilities,” https://www.ccrw.org/i-am-an-employer/the-business-case-for-hiring-persons-with-disabilities/. Rotary at Work BC; 81 81 M. Wafer, “Don’t Lower the Bar—Whitepaper,” Rotary at Work, April 2014, https://rotaryatworkbc.com/dont-lower-bar-whitepaper-mark-wafer/. and the Ontario Disability Employment Network. 82 82 Ontario Disability Employment Network, “Business Benefits,” https://odenetwork.com/businesses/why-hire. The Ready, Willing and Able (RWA) initiative of the Centre for Inclusion and Citizenship, to take just one example, has convinced many employers of the benefits of hiring qualified candidates with disabilities. When RWA surveyed participating employers, 95 percent of respondents rated the employees with disabilities hired through RWA as on par with or better than the average employee, and almost two-thirds indicated that they would likely try to hire more of these employees in the next year. 83 83 T. Stainton, R. Hole, and C. Crawford, “Ready, Willing and Able Initiative: Evaluation Report,” Centre for Inclusion and Citizenship, January 2018, 18, https://cic.arts.ubc.ca/files/2019/05/Ready-Willing-and-Able-Evaluation-Final-Report-January-2018-1.pdf. Most of those not considering new hires in the next year said their firm did not need more employees or cited budgetary reasons. RWA’s success is all the more noteworthy given that they support candidates with autism spectrum disorder or intellectual disabilities, for whom labour-market participation is particularly low, as noted above.

Nor is it only individual employers who stand to benefit from increased employment of people with disabilities: the national economy could get a significant boost as well. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), a nation that managed to bring employment rates of people with disabilities to the same level as those of people without disabilities could experience an economic boost of up to 3 to 7 percent of its GDP. 85 85 ILO and OECD, “Labour Market Inclusion,” 2. The authors were not able to fully review the paper’s methodology, so we advise caution when using this data. The International Social Security Association estimates that for every $1.00 spent on vocational rehabilitation and work reintegration for workers forced to leave the labour market due to health problems, the return on investment is up to $3.70 for employers, $2.90 for welfare systems, and $2.80 for the economy as a whole in productivity gains. 86 86 N. Echarti, E. Schüring, and G. Kemper, “The Return on Work Reintegration,” International Social Security Association, 2017, https://ww1.issa.int/sites/default/files/documents/publications/2-RoW-WEB-222487.pdf. Given that the prevalence of disability is likely to increase as Canada’s workforce ages, policy-makers and market actors have much to gain from tapping into this underutilized talent pool.

Identifying the Challenges and Complexities of Good Disability Policy

Why, then, have decades of policy innovation and investment by multiple levels of government failed to make the benefits of employment equally available to people with disabilities? In the following section, we identify some of the key questions relevant to an effective work-disability policy. This list is intended to be suggestive, not exhaustive, and to raise key questions for further consideration by stakeholders rather than provide definitive answers to them.

It is important to acknowledge that the way we define disability shapes our approach to disability policy. Since the medical model views disability through the lens of a condition impairing an individual’s body or mind, interventions based on this model focus on “fixing” the impaired individual. The social model, in contrast, views disability as arising from an interaction between the individual and his or her environment. Interventions based on this model—including those discussed in this paper—focus on addressing the disabling barriers that prevent a person’s full participation in various aspects of society. 87 87 C. Collin, I. Lafontaine-Émond, and M. Pang, “Persons with Disabilities in the Canadian Labour Market: An Overlooked Talent Pool,” Library of Parliament Background Papers no. 2013-17-E, Library of Parliament, 2013, 17, https://lop.parl.ca/staticfiles/PublicWebsite/Home/ResearchPublications/BackgroundPapers/PDF/2013-17-e.pdf.

How Should Policy-Makers Define and Measure Disability?

The complexity and fluidity of disability make it difficult to define and measure from a policy perspective. Since disability refers to limitations that are sensitive to environmental factors rather than a demographic characteristic, there is no single method used to identify those with disabilities in a given population. Population surveys measuring disability usually ask respondents whether they have a health condition limiting their daily living or work activities, which means that disability is effectively self-assessed. 88 88 Jones, “Disability and the Labour Market,” 404. Most developed nations have some form of disability benefits, but relative to other elements of the social safety net like old age security, determining who is eligible for public disability benefits is subjective: age is a simple standard to determine who qualifies for public pensions, but there is no obvious or easily verifiable way to determine who qualifies for long-term disability benefits. 89 89 R.V. Burkhauser, M.C. Daly, and N.R. Ziebarth, “Protecting Working-Age People with Disabilities: Experiences of Four Industrialized Nations,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper Series 2015–08, 2015, 8, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/wp2015-08.pdf. This means the prevalence of disability in the working-age population is highly sensitive to the stringency of the definition of disability used, 90 90 Haveman and Wolfe, “The Economics of Disability and Disability Policy,” 1001. and that the number of people who qualify for public disability-support programs at any given point will depend on the official eligibility criteria set by the government. The experience of disability can vary significantly over a person’s lifetime, at different stages of the employment cycle, and from one place to another, which means the size and composition of the population experiencing disability are constantly in flux.

Key Questions for Sound Policy

- What is/are the most accurate and reliable definition(s) of disability for government, given its particular capacities and goals?

- How should a government measure and track the prevalence of disability in its population?

Why Are Disability-Benefit Caseloads Rising? What, if Any, Is the Connection Between Disability Policy, Unemployment Policy, and Individual Behaviour?

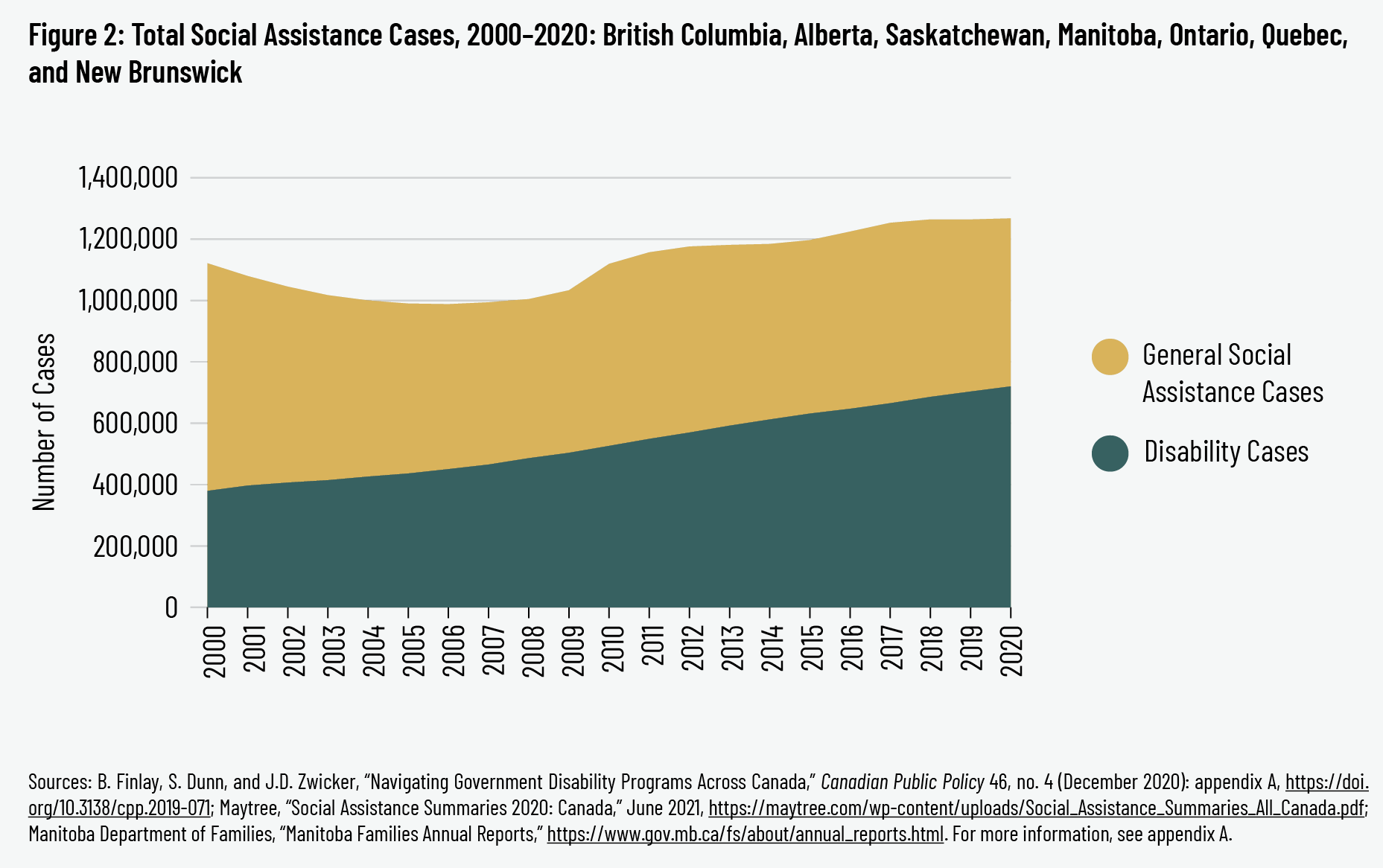

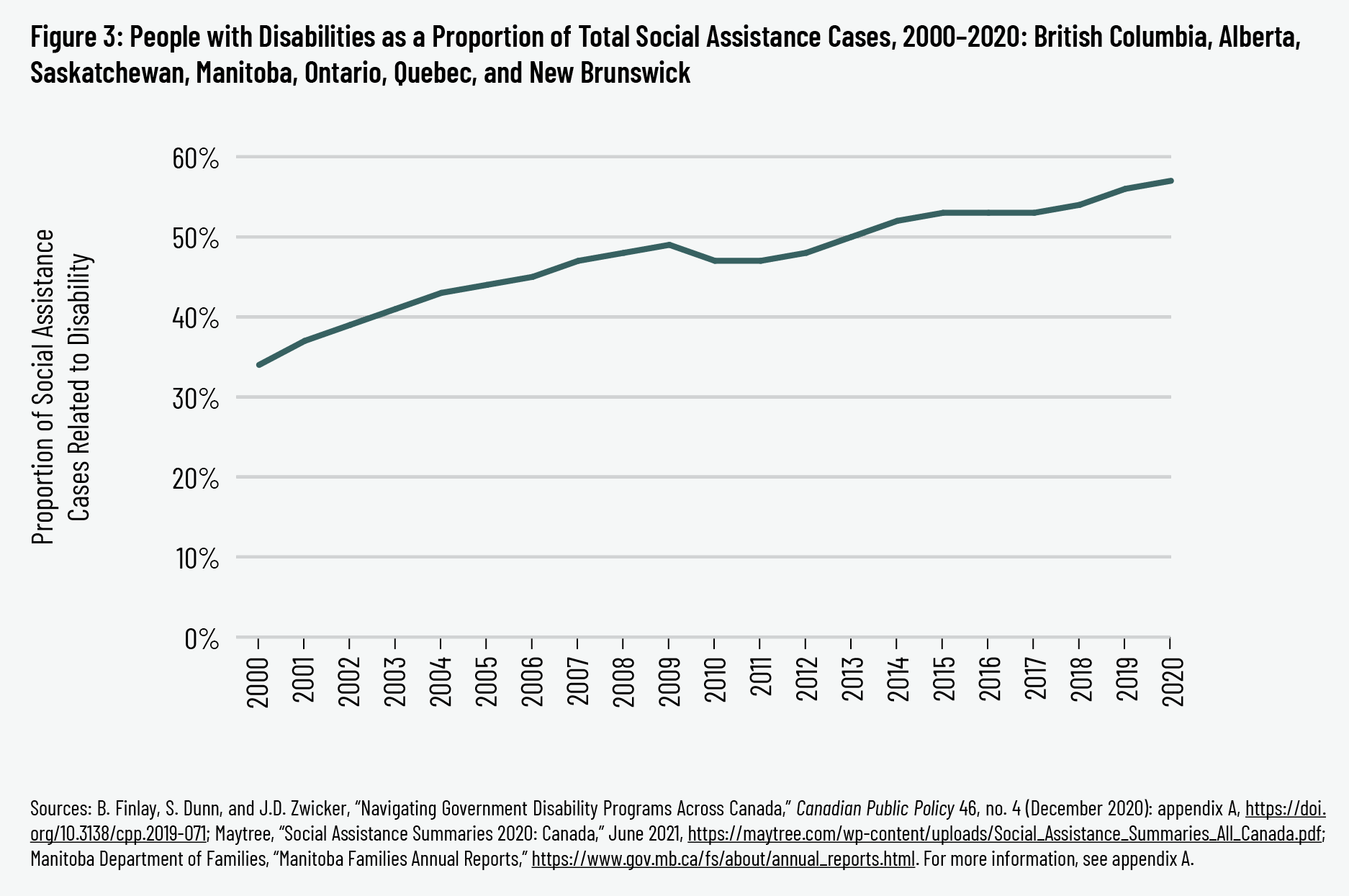

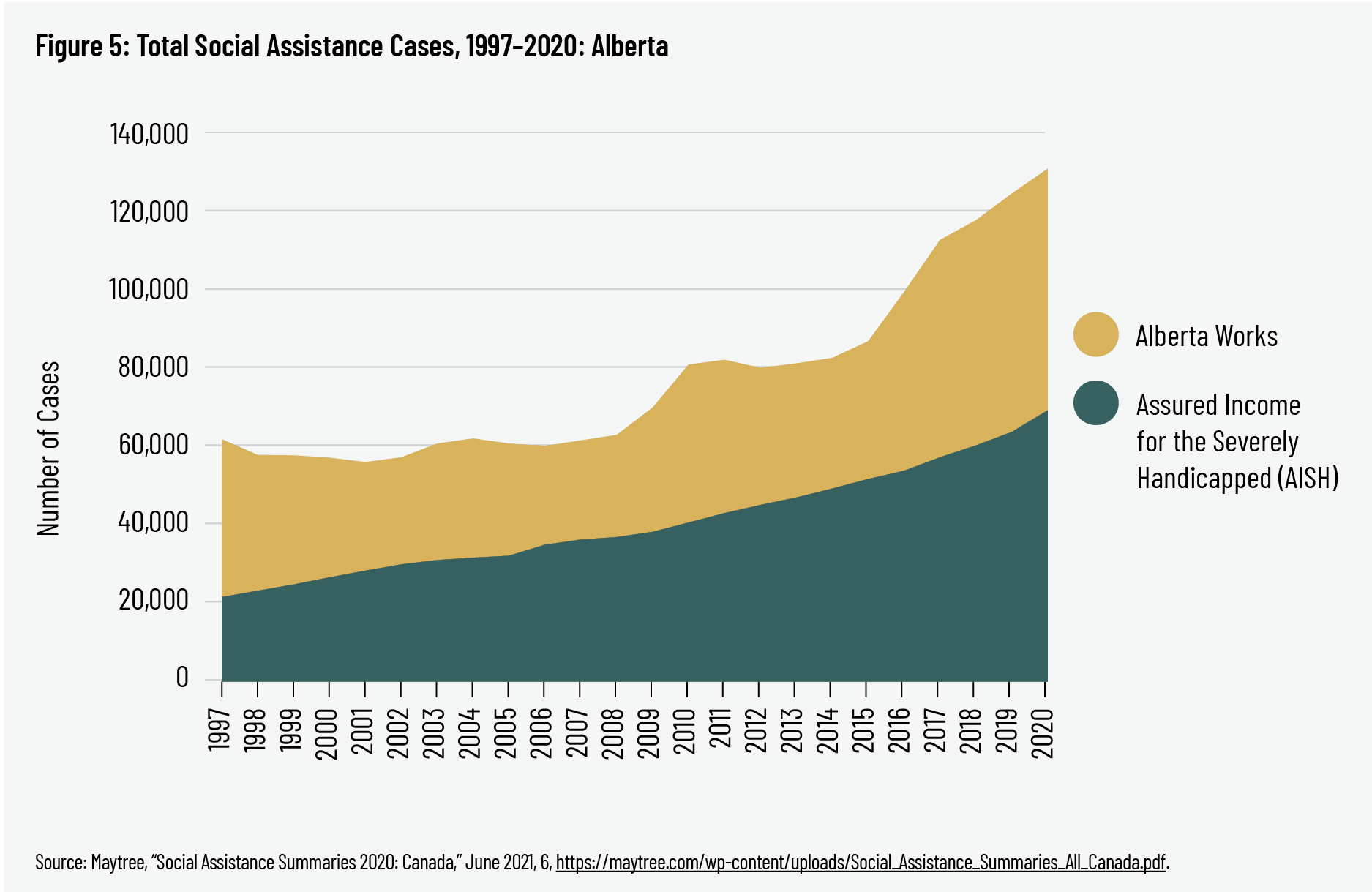

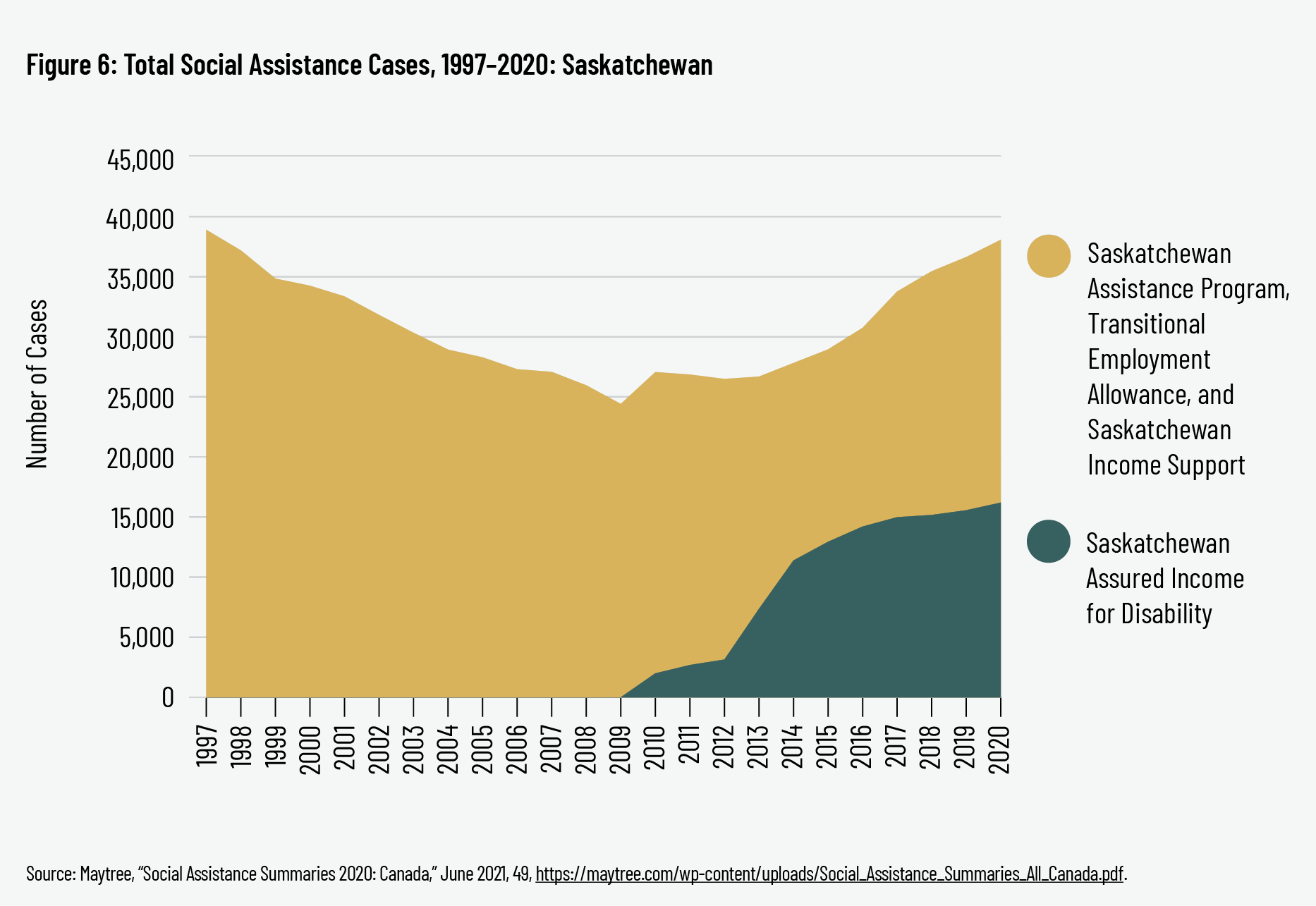

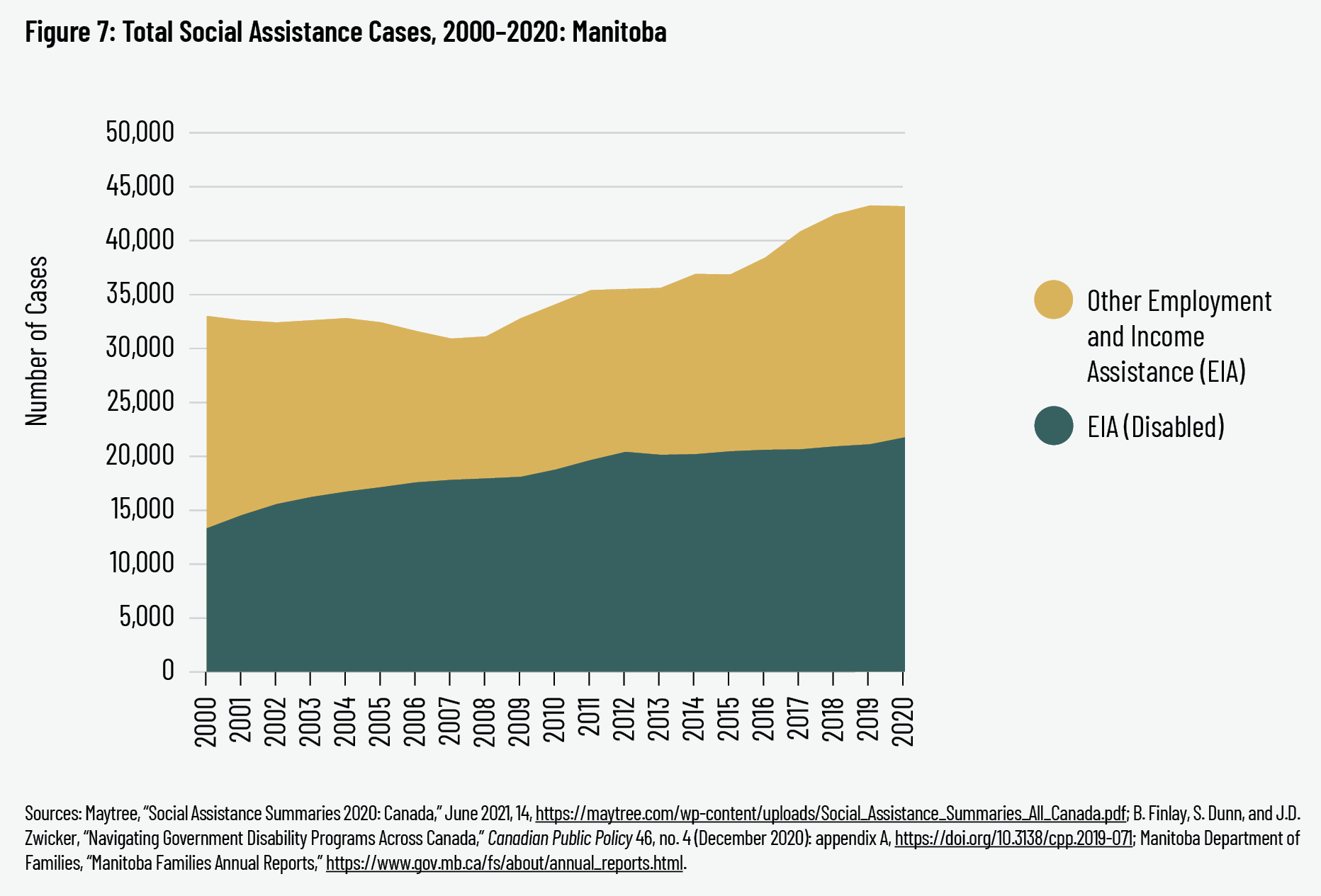

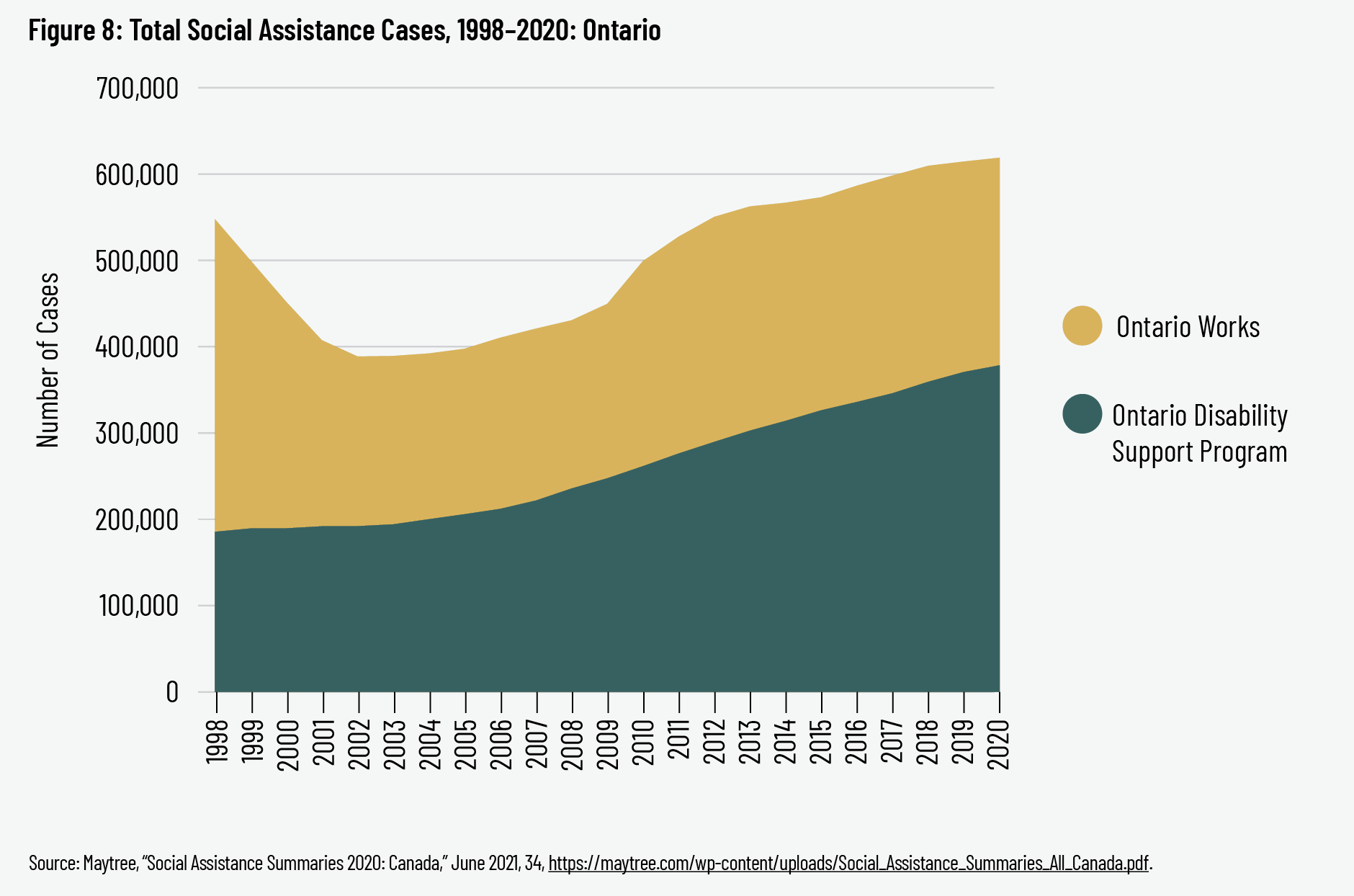

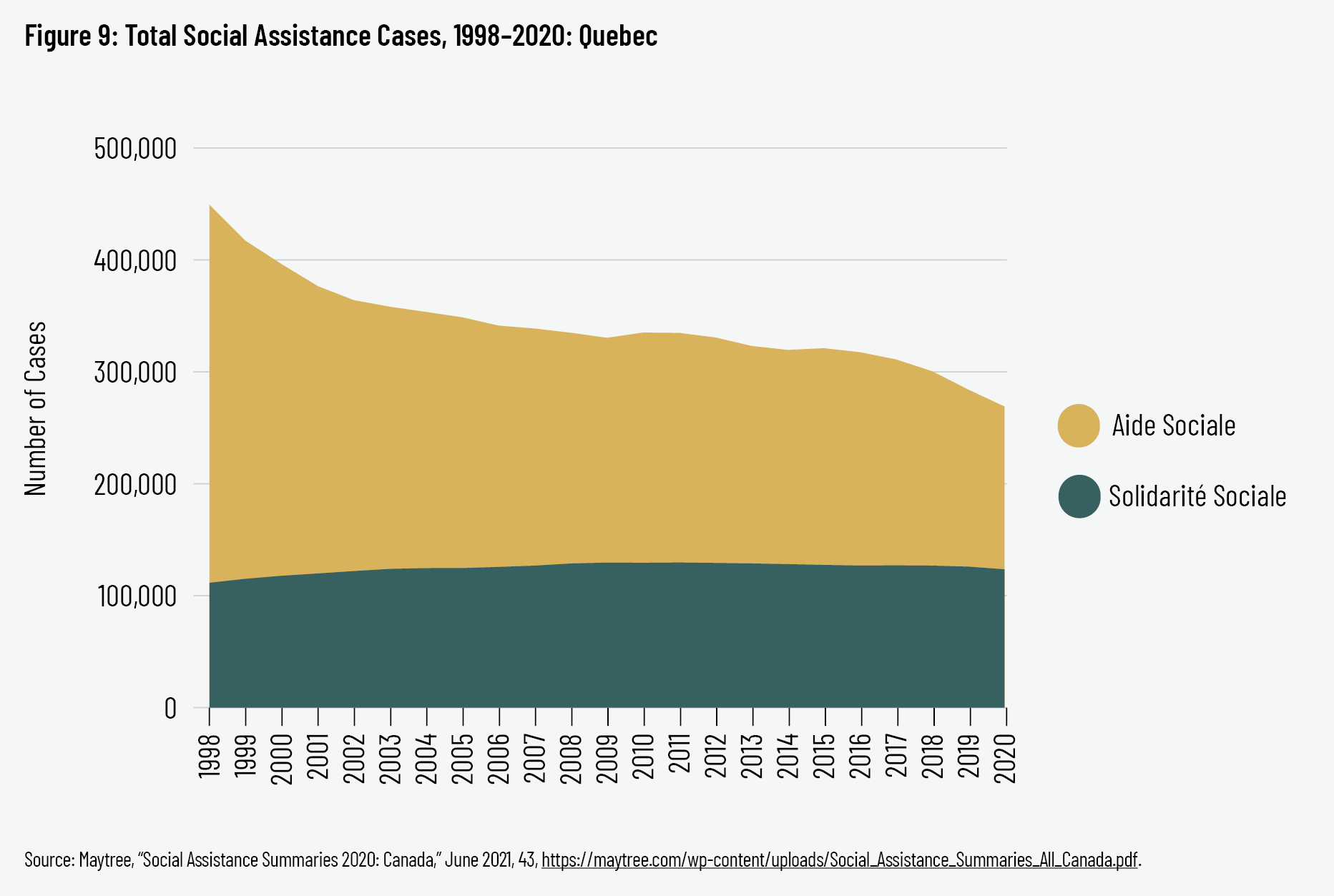

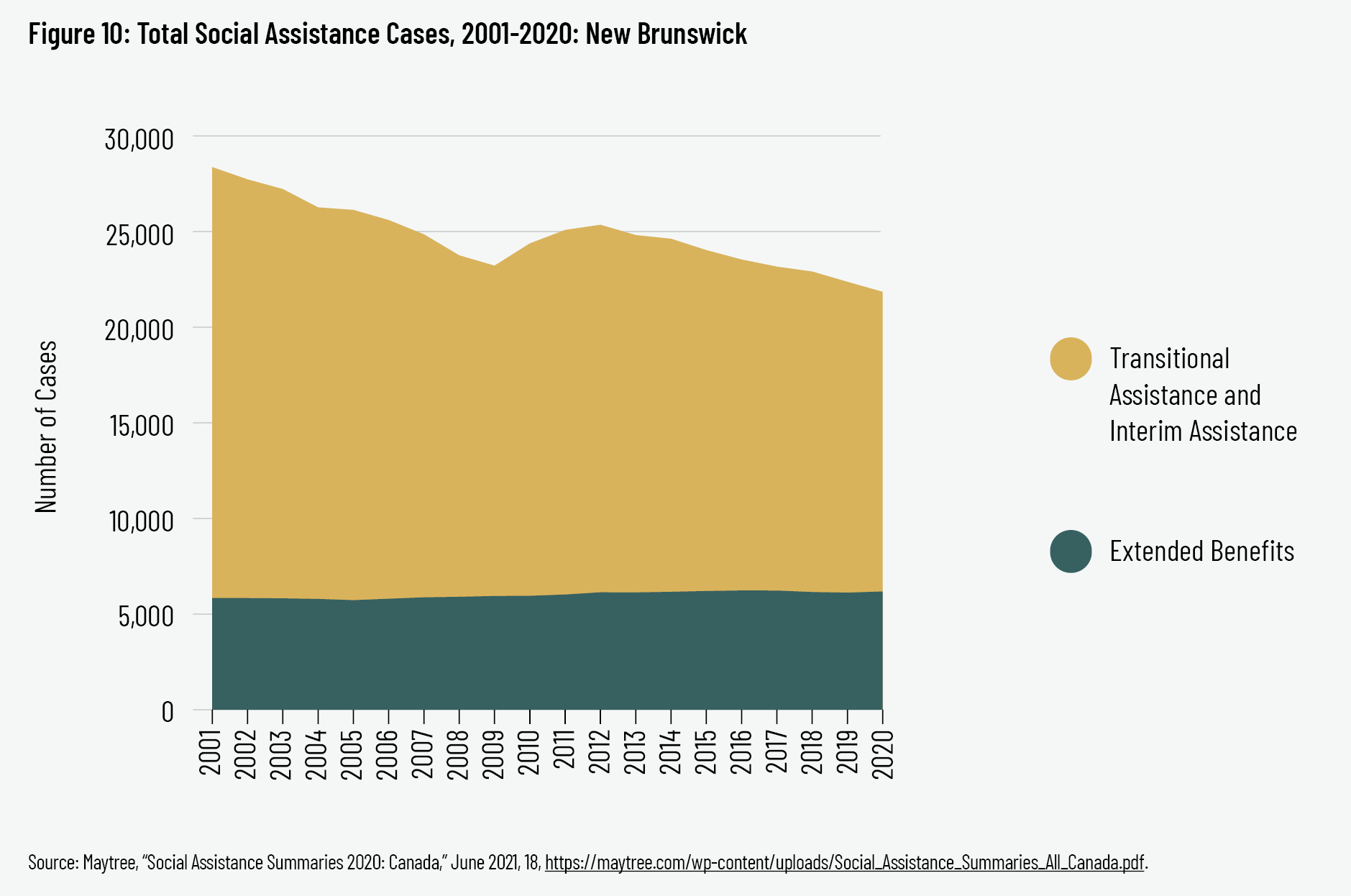

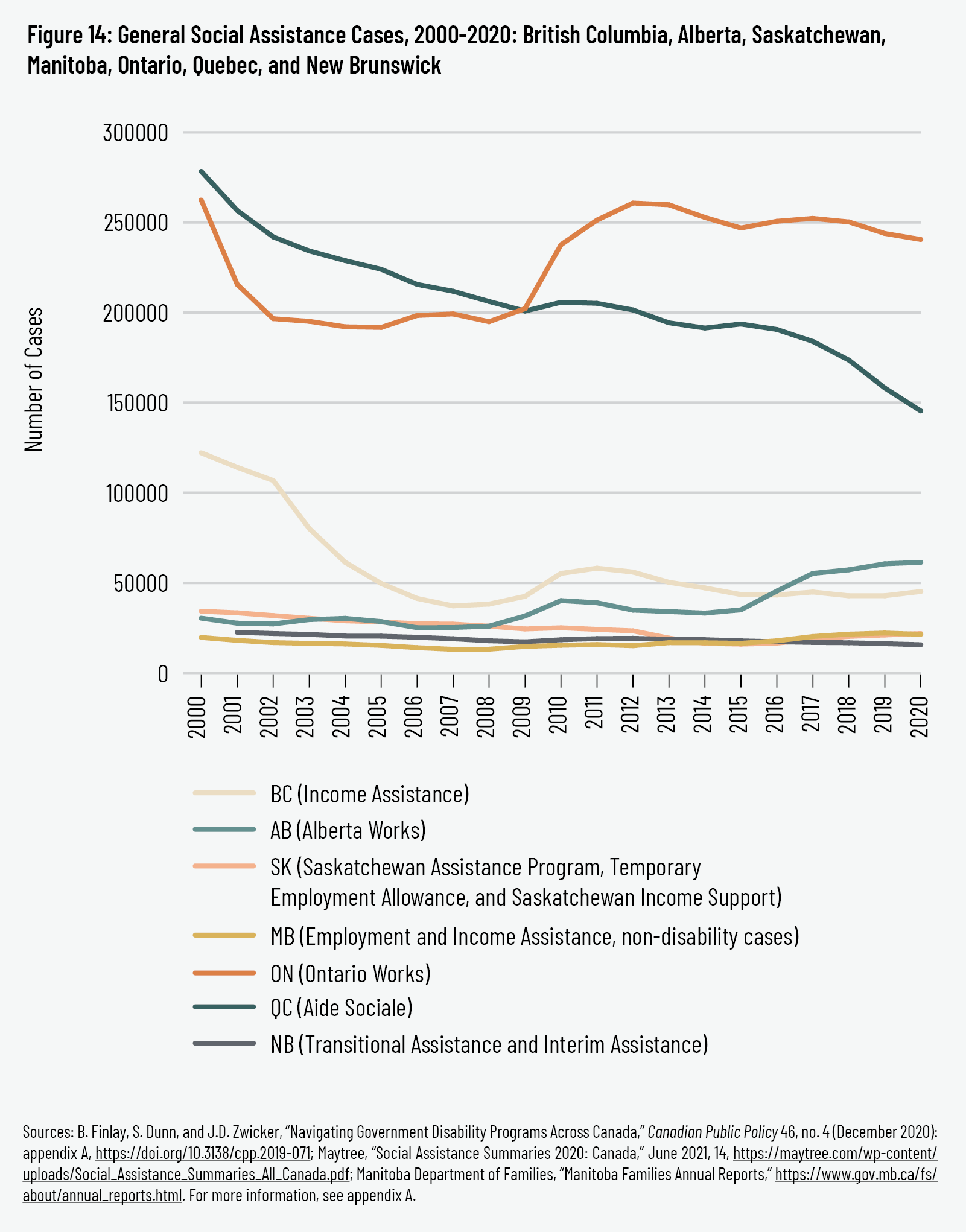

Over the past two decades, the number of Canadians receiving income support because of a disability has risen, both in absolute terms and as a proportion of total social-assistance cases. We examined caseload data for income-assistance programs in all provinces for which data were available—Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, New Brunswick, Ontario, Quebec, and Saskatchewan, which together represent more than 95 percent of Canada’s total population. 91 91 Data were also available for Prince Edward Island, but only for 2008 to 2018, so we did not include these figures in our total calculations. Caseload figures represent authors’ calculations based on data from B. Finlay, S. Dunn, and J.D. Zwicker, “Navigating Government Disability Programs Across Canada,” Canadian Public Policy 46, no. 4 (October 2, 2020): appendices A and B, https://www.utpjournals.press/doi/suppl/10.3138/cpp.2019-071; Maytree, “Social Assistance Summaries 2020: Canada,” June 2021, https://maytree.com/wp-content/uploads/Social_Assistance_Summaries_All_Canada.pdf; and (for Manitoba) Manitoba Department of Families, “Families Annual Reports,” https://www.gov.mb.ca/fs/about/annual_reports.html. Population figures represent Q4 2020 estimates by Statistics Canada, “Table 17-10-0009-01: Population Estimates, Quarterly,” September 29, 2021, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=10&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2020&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=10&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2020&referencePeriods=20201001%2C20201001. For more information, see appendix A. Between 2000 and 2020, the number of disability-income-support cases has grown from around 382,000 to 725,000, an increase of 90 percent, while the caseload for all other social-assistance programs shrank by more than a quarter, from 747,000 to 552,000. Between the growth of disability-related cases and the decline of other cases, the share of social-assistance cases connected to disability has risen from 33 percent in 2000 to 57 percent in 2020, a 70 percent increase over the past two decades. As we examine in more detail below, it is unclear whether and/or to what extent these trends represent a transfer from one social-assistance program to another as opposed to an influx of new cases.

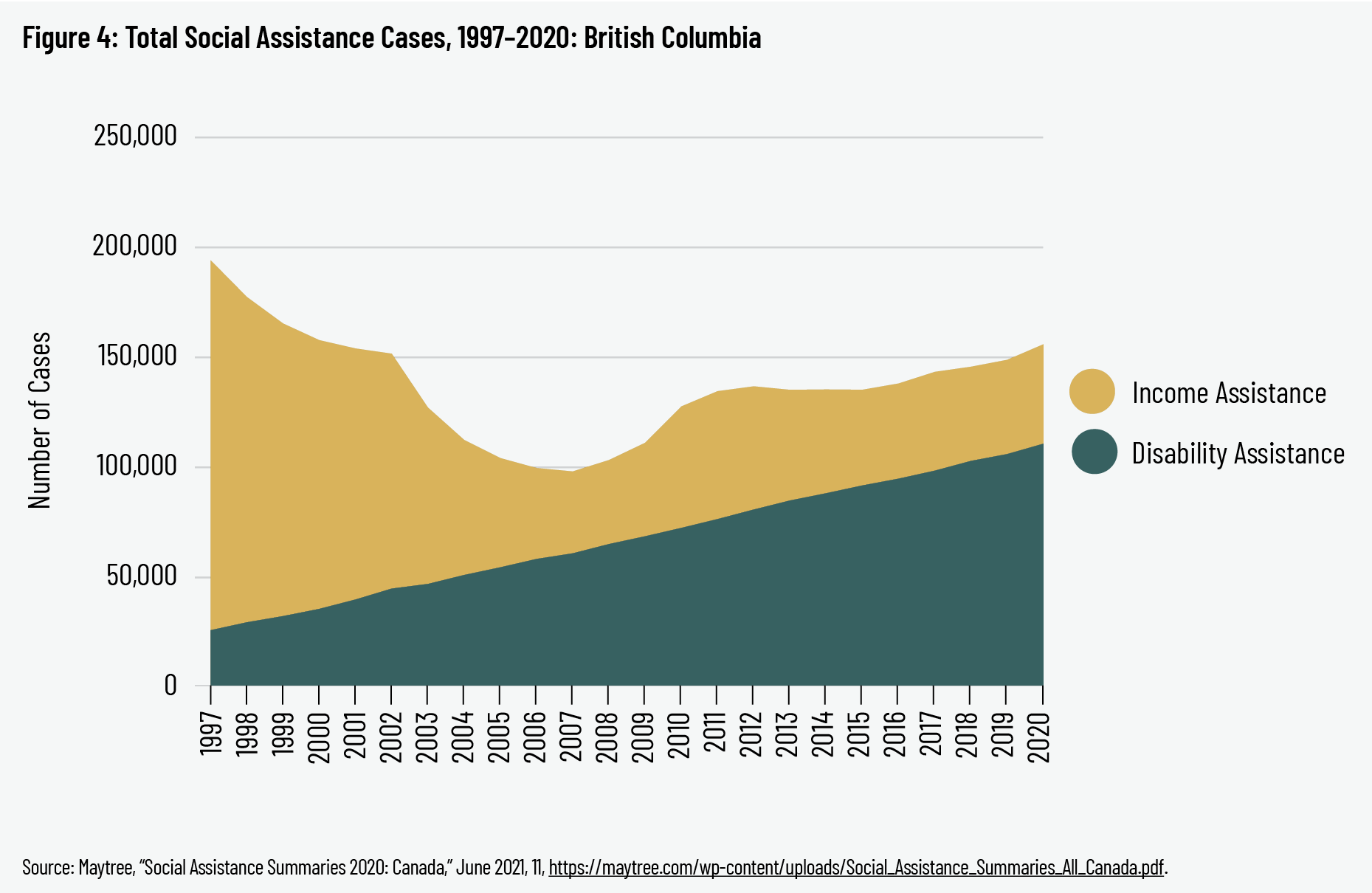

The rate at which the share of disability-related cases is rising in social-assistance programs varies from province to province. In Alberta, for example, cases in the Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) program represented 47 percent of social-assistance cases in 2000 compared to 53 percent in 2020, a relatively small increase of only 13 percent. Similarly, the share of New Brunswick’s social-assistance cases in its Extended Benefits program 92 92 “For those who are certified by the Medical Advisory Board as blind, deaf or disabled.” New Brunswick Social Development, “Social Assistance Rate Schedule A,” https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/social_development/social_assistance/social_assistancerateschedules.html. has grown by a moderate 37 percent since 2001 and in 2020 made up only 28 percent of cases. In Ontario and Quebec, in contrast, the numbers are higher: since 2000, Ontario Disability Support Program and Solidarité Sociale cases have grown by 46 and 55 percent, respectively, as a share of each province’s social-assistance caseload; in 2020, 61 percent of income support cases in Ontario and 46 percent of cases in Quebec were disability related. However, the largest increase by far has occurred in British Columbia. In 2000, there were around 34,800 Disability Assistance cases in the province, representing a modest 22 percent of income support recipients. By 2020, the Disability Assistance caseload had ballooned to just shy of 110,000 cases and 71 percent of the province’s income support program—an increase approaching 220 percent on both fronts.

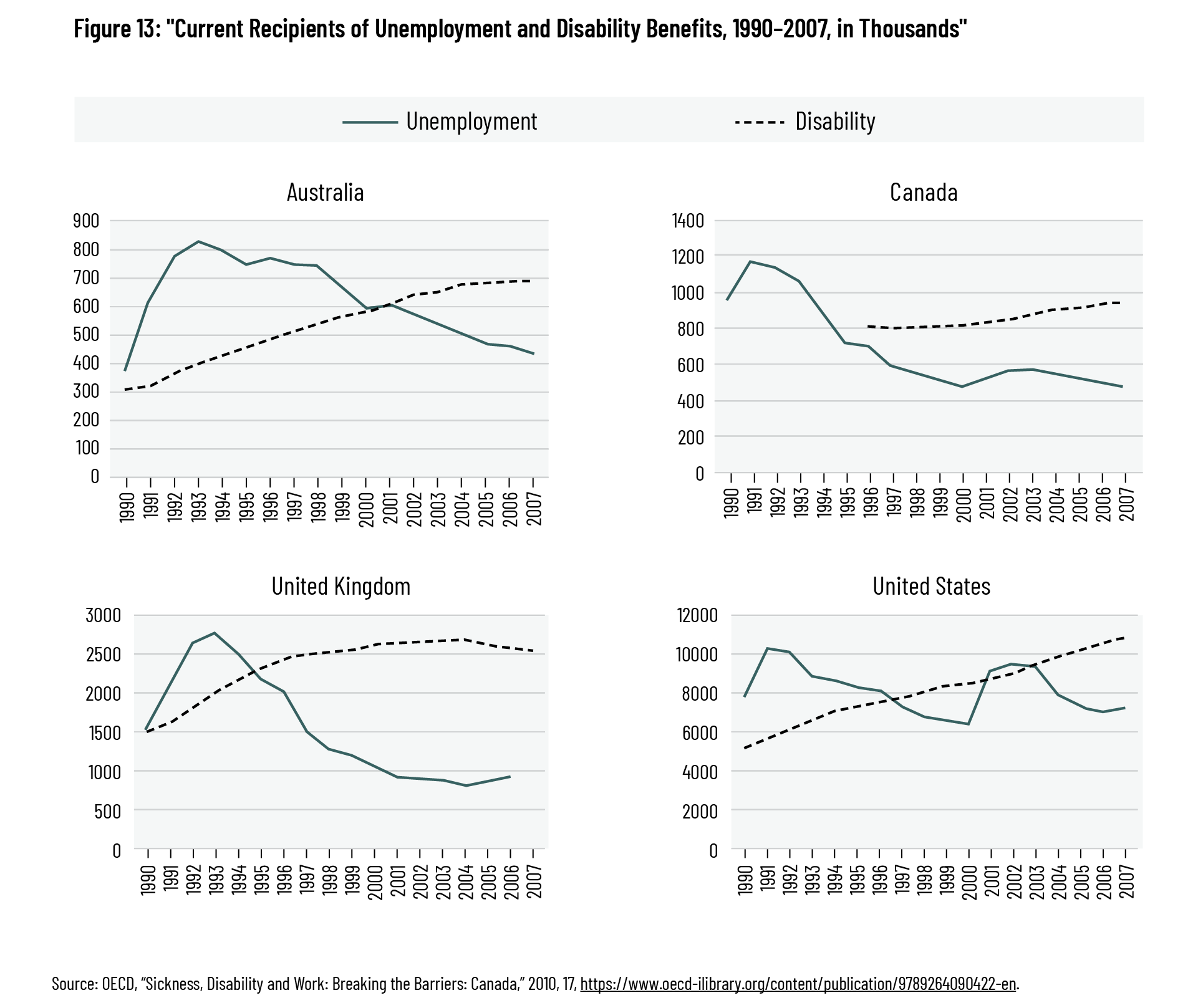

This pattern is consistent across other developed nations. The number of working-age adults receiving disability assistance has risen substantially both in absolute terms and as a proportion of the working-age adult population in most OECD countries in the past four decades. 93 93 R.V. Burkhauser et al., “Disability Benefit Growth and Disability Reform in the US: Lessons from other OECD Nations,” IZA Journal of Labor Policy 3, no. 4 (2014): 2. This growth cannot be explained only by changes in self-reported health or other demographic indicators, which have remained fairly stable in contrast to the fluctuation in disability-recipience rates, suggesting policy changes are playing an important role. 94 94 Burkhauser et al., “Disability Benefit Growth and Disability Reform in the US,” 4; see also R.V. Burkhauser, M.D. Schmeiser, and M. Schroeder, “The Employment and Economic Well Being of Working-Age Men with Disabilities: Comparing Outcomes in Australia, Germany, and Great Britain with the United States” (paper presented at the HILDA Survey Research Conference 2007, University of Melbourne, July 19, 2007), https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/assets/documents/hilda-bibliography/hilda-conference-papers/2007/Burkhauser-Schmeiser-Schroeder-6-28-07.pdf.

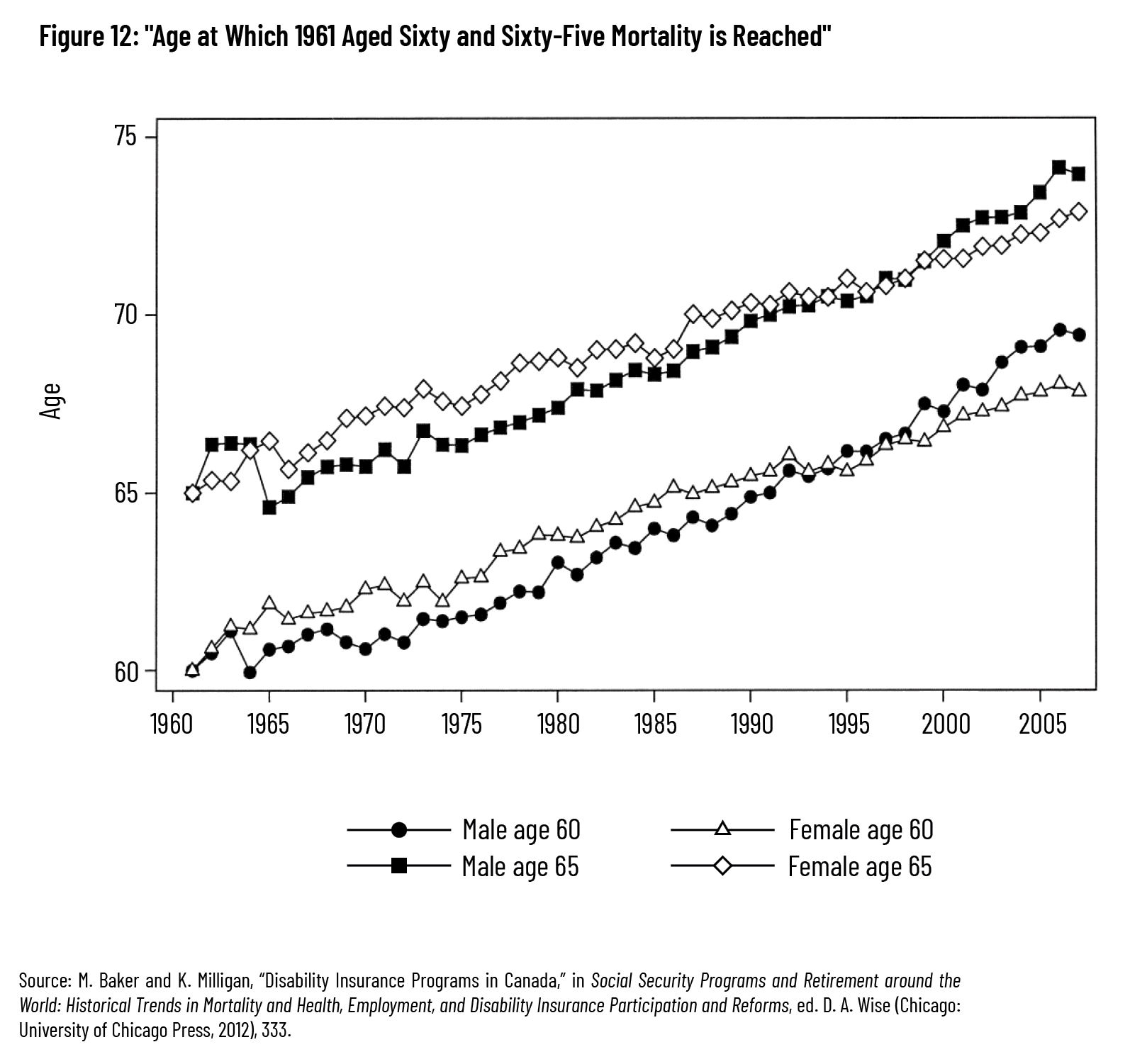

But why is this happening? Definitive answers have been elusive. Demographic trends are responsible for at least some of the increase. As the population ages, more Canadians are experiencing late-onset disabilities, and Canadians whose disabilities were present from birth or early life are living longer. 95 95 J. Stapleton, A. Tweddle, and K. Gibson, “What Is Happening to Disability Income Systems in Canada? Insights and Proposals for Further Research,” Disabling Poverty/Enabling Citizenship, Council of Canadians with Disabilities, February 2013, http://www.ccdonline.ca/en/socialpolicy/poverty-citizenship/income-security-reform/disability-income-systems.

Yet policy also plays a significant role. Since disability is not a static state but emerges from the interaction between individuals and their environment (both of which are dynamic), disability policies affect the behaviour of affected individuals. 96 96 Burkhauser et al., “Disability Benefit Growth and Disability Reform in the US,” 2. It is possible that worthwhile policy initiatives could inadvertently lead to the growth of disability-benefit rolls. Anti-discrimination legislation, for example, is often designed to improve the employment security of people with disabilities by requiring employers to offer reasonable accommodations. However, another effect of the legislation might be to reduce (perceived) public stigma surrounding disability, such that some people feel comfortable identifying a previously concealed disability as the reason for their unemployment. 97 97 This “composition effect” was suggested by Acemoglu and Angrist as a potential explanation for employment trends observed after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), but they did not find evidence for a composition effect of the ADA in their study. D. Acemoglu and J.D. Angrist, “Consequences of Employment Protection? The Case of the Americans with Disabilities Act,” Journal of Political Economy 109, no. 5 (October 1, 2001): 935. Another positive development has been the increasing recognition of certain mental health conditions as disabilities. 98 98 See, for example, the fictional case of Bob in Stapleton, Tweddle, and Gibson, “What Is Happening to Disability Income Systems in Canada?” In either of these cases, disability-benefit rolls could grow despite—or even because of—the successful implementation of the policy.

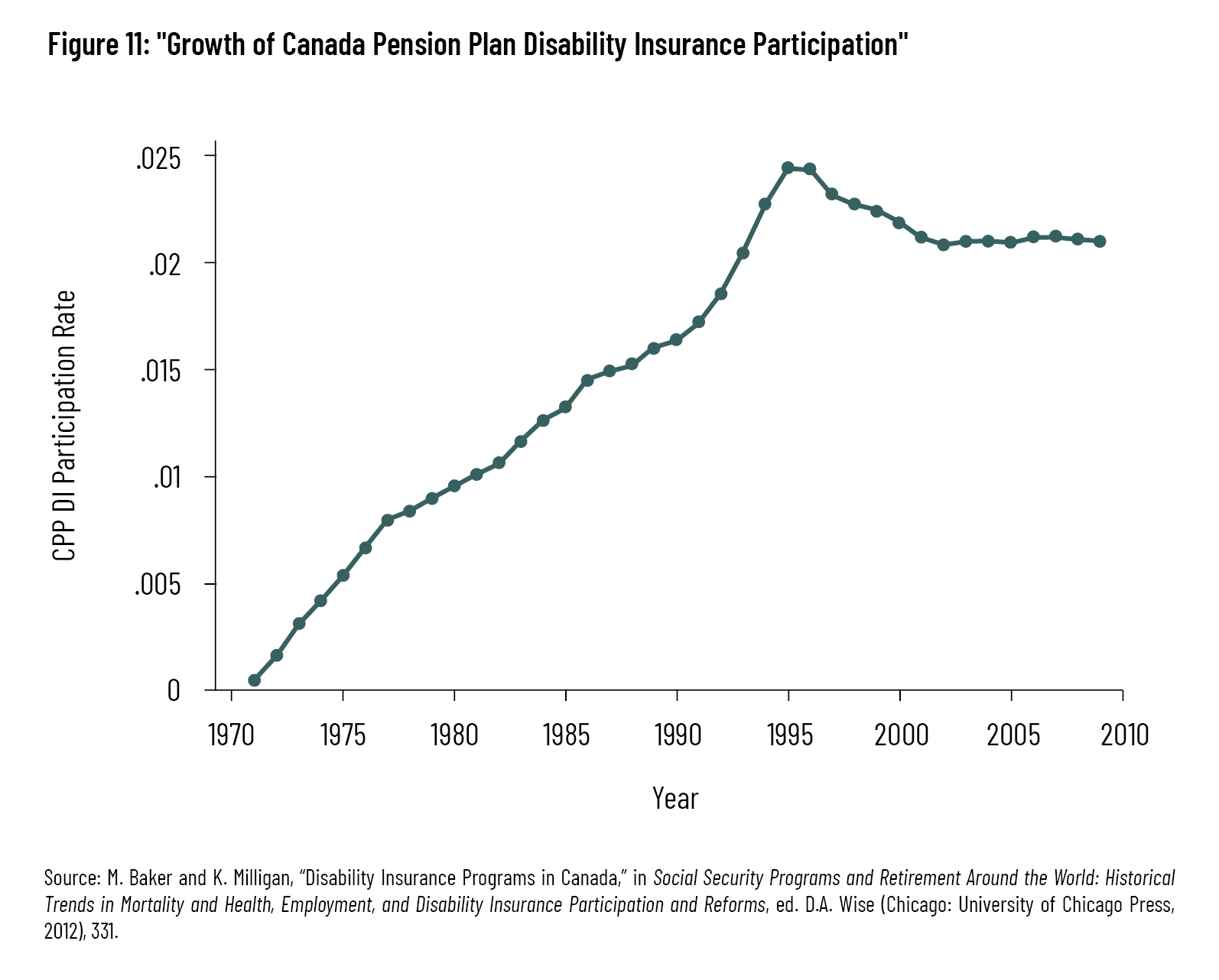

The design of disability-benefit programs also affects behaviour, though exactly how it does so is unclear. Some research has found, perhaps unsurprisingly, that more generous benefits attract more applicants. 99 99 Mont, “Disability Employment Policy,” 17–18. Benefit levels do not have a significant effect on the number of people leaving disability programs: regardless of the generosity of benefits, very few people who start receiving long-term disability ever leave the program (see below). Baker and Milligan, for example, examine the history of the Disability Insurance (DI) program added to the Canada/Quebec Pension Plan (CPP/QPP) in 1970. They find a strong link between program changes and the number of Canadians receiving disability insurance; the link between observed health trends and disability-benefits recipience, in contrast, was weak. Participation began increasing more sharply in 1987, the same year in which reforms were introduced to make the DI program more generous. 100 100 M. Baker and K. Milligan, “Disability Insurance Programs in Canada,” in Social Security Programs and Retirement Around the World: Historical Trends in Mortality and Health, Employment, and Disability Insurance Participation and Reforms, ed. D.A. Wise (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 327–58. The stringency of screening criteria can also play a role. Baker and Milligan observe a decline in the CPP-DI participation rate after 1995 when reforms were introduced that tightened eligibility criteria for the program. 101 101 Baker and Milligan, “Disability Insurance Programs in Canada.” This observation is in line with Campolieti’s study of the Canada/Quebec Pension Plan, which found evidence to suggest that the 1987 reforms making CPP/QPP disability benefits more generous led to an increase in claims for disability from hard-to-diagnose soft-tissue and musculoskeletal impairments. 102 102 M. Campolieti, “Moral Hazard and Disability Insurance: On the Incidence of Hard-to-Diagnose Medical Conditions in the Canada/Quebec Pension Plan Disability Program,” Canadian Public Policy 28, no. 3 (Sept. 2002): 419–41.

Moreover, disability policies interact with other policies constituting a nation’s social safety net and with broader labour-market conditions. 103 103 Burkhauser et al., “Disability Benefit Growth and Disability Reform in the US,” 7. These factors make it difficult for researchers to determine the precise nature of the relationship between the various disability-policy reforms of the past several decades and the significant growth in disability-benefit caseloads. Some researchers have noted that the recent shift toward a knowledge-based economy has created new barriers to labour-market participation for low-skilled workers. They suggest that the growth of disability rolls experienced by many developed countries in the past three decades might be attributable to “a combination of both an increase [in the] generosity of disability benefits and the deterioration in the labour market for low skilled workers.” 104 104 Jones, “Disability and the Labour Market,” 407. See also D.H. Autor and M.G. Duggan, “The Rise in the Disability Rolls and the Decline in Unemployment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 118, no. 1 (2003): 157–206. If public disability insurance is more generous than unemployment insurance, it can create an incentive for those who acquire a mild impairment to apply for disability insurance rather than seek accommodations and/or rehabilitation. 105 105 Haveman and Wolfe, “The Economics of Disability and Disability Policy,” 1021; see also Jones, “Disability and the Labour Market”; A. Kapteyn, J.P. Smith, and A. van Soest, “Work Disability, Work, and Justification Bias in Europe and the United States,” in Explorations in the Economics of Aging, ed. D.A. Wise (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 269–312. In 2003, for example, OECD governments spent more than double on disability programs than they did on unemployment compensation. 106 106 Jones, “Disability and the Labour Market,” 405. As in other OECD nations, by 2010 more working-age Canadians were on disability programs than unemployment programs, and the growth in disability recipients since the early 2000s coincided with a drop in unemployment recipients. 107 107 OECD, “Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers: Canada,” 17.

While our partial caseload data is merely descriptive and cannot imply a causal relationship between programs, they at the very least do not explicitly contradict this pattern. Disability cases have been growing as a share of social-assistance caseloads not only because the number of disability cases has been growing but also because the growth of other income-support programs has been slower or even negative. Alberta is a notable exception—the caseload for the general social-assistance program Alberta Works doubled in size between 2000 and 2020 (though most of this growth has occurred since 2015), and Manitoba also saw a modest 9 percent increase in non-disability cases in its Employment and Income Assistance (EIA) program. In other provinces, however, general income-support caseloads have been shrinking over the past two decades, falling by 8 percent in Ontario, 24 percent in New Brunswick, 36 percent in Saskatchewan, 48 percent in Quebec, and 63 percent in British Columbia. 108 108 Excluding caseload data from 2000 in the province of New Brunswick.

Other researchers have pointed to an increasing proportion of workers in precarious—part-time, temporary, and contract-based—jobs, which do not provide workers with access to employer-triggered disability-income programs if they experience disability. Without the protection of workplace compensation programs, more workers with disabilities are forced to turn to public social assistance. 109 109 J. Stapleton, “The ‘Welfareization’ of Disability Incomes in Ontario,” Inclusive Local Economies, Metcalf Foundation, December 2013, https://metcalffoundation.com/publication/the-welfareization-of-disability-incomes-in-ontario/; Stapleton, Tweddle, and Gibson, “What Is Happening to Disability Income Systems in Canada?” In other words, there may not be significantly more people applying for disability benefits overall; they are simply forced to apply for benefits from different sources. In Canada, Stapleton, Tweddle, and Gibson have documented a trend in disability income systems from programs based on workforce participation—Employment Insurance sickness benefits, the disability component of the Canada Pension Plan and Quebec Pension Plan, veterans’ disability pensions, private short- and long-term disability-insurance plans, and worker’s compensation—to programs without any labour-force connection—namely, disability tax credits, the Registered Disability Savings Plan, and especially provincial social-assistance programs. 110 110 Stapleton, Tweddle, and Gibson, “What Is Happening to Disability Income Systems in Canada?”

While the interactions between labour-markets conditions, government policies, and individual behaviour are complex, the examples above illustrate possible pathways by which passive disability-benefit programs can become a long-term (and in many cases permanent) substitution for time-limited unemployment programs. 111 111 Researchers have found evidence that disability benefits act to some extent as substitutes for unemployment benefits. See, e.g., A. Bíró and P. Elek, “Job Loss, Disability Insurance and Health Expenditure,” Labour Economics 65 (2020): 101856; P. Koning and D. van Vuuren, “Hidden Unemployment in Disability Insurance,” LABOUR 21, nos. 4–5 (2007): 611–36; P. Koning and D. van Vuuren, “Disability Insurance and Unemployment Insurance as Substitute Pathways,” Applied Economics 42, no. 5 (2010): 575–88. This can add yet another barrier to work by shifting beneficiaries from a labour-market-oriented program to one with little to no focus on workforce attachment. In addition to its negative impact on the social, physical, psychological, and financial lives of people with disabilities who say they would prefer to work, this pattern has major implications for public balance sheets. Stapleton, Tweddle, and Gibson, for example, found that spending on social-assistance disability-income programs across Canada grew by nearly 30 percent between 2005–6 and 2010–11, from $23.2 billion to $28.6 billion. 112 112 Stapleton, Tweddle, and Gibson, “What Is Happening to Disability Income Systems in Canada?” This pattern was particularly pronounced in Ontario and the western provinces.

Key Questions for Sound Policy

- What factors are driving the increase in disability-related caseloads as a proportion of provincial social-assistance cases?

- What factors are responsible for the variation in social-assistance-caseload trends between provinces?

- Have certain policy changes contributed to the increase in disability caseloads? If so, how and to what extent?

How Should Governments Balance Spending on Financial Assistance and Employment Supports?

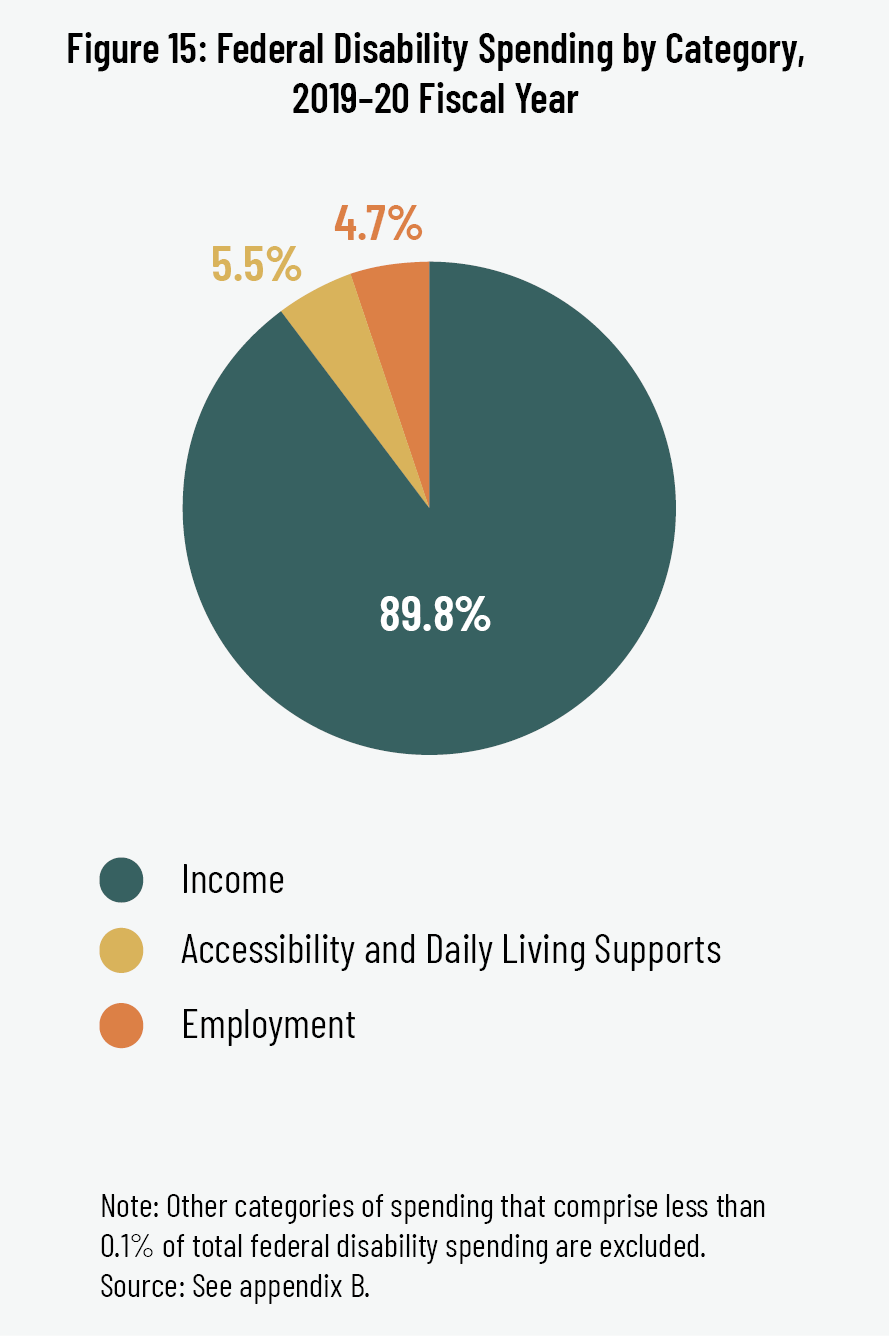

Government policies to support the economic well-being of citizens with disabilities usually aim to achieve two related goals: ensuring income security for those who are unable to work because of a disability, and promoting employment for those who are able to work through incentives and supports. 113 113 OECD, “Sickness, Disability and Work,” 11; ILO and OECD, “Labour Market Inclusion,” 5. A common third pillar of government disability policy is accessibility supports—i.e., programs to improve the accessibility of private and public spaces (resources for home or workplace modifications, for example), as well as daily living supports for individuals and families experiencing disability, such as assisted living arrangements or extended health benefits. Both goals are critically important. Yet despite the many benefits of work—both monetary and non-monetary—for individuals, families, businesses, and societies, as well as the significance of employment for social inclusion, work has received a dramatically lower share of government investment. Until the mid-1990s, most OECD countries made generous disability benefits a priority and put little emphasis on employment supports. Despite making some pro-work reforms in the 1990s, the balance remained skewed toward income assistance: the OECD has estimated that by 2010, nearly all OECD nations were devoting more than 90 percent of disability spending to passive cash benefits. 114 114 OECD, “Sickness, Disability and Work,” 11–12. Canada was no exception, dedicating only 4–6 percent of its incapacity-related spending to active labour-market programs. 115 115 OECD, “Sickness, Disability and Work: Breaking the Barriers: Canada,” 45.

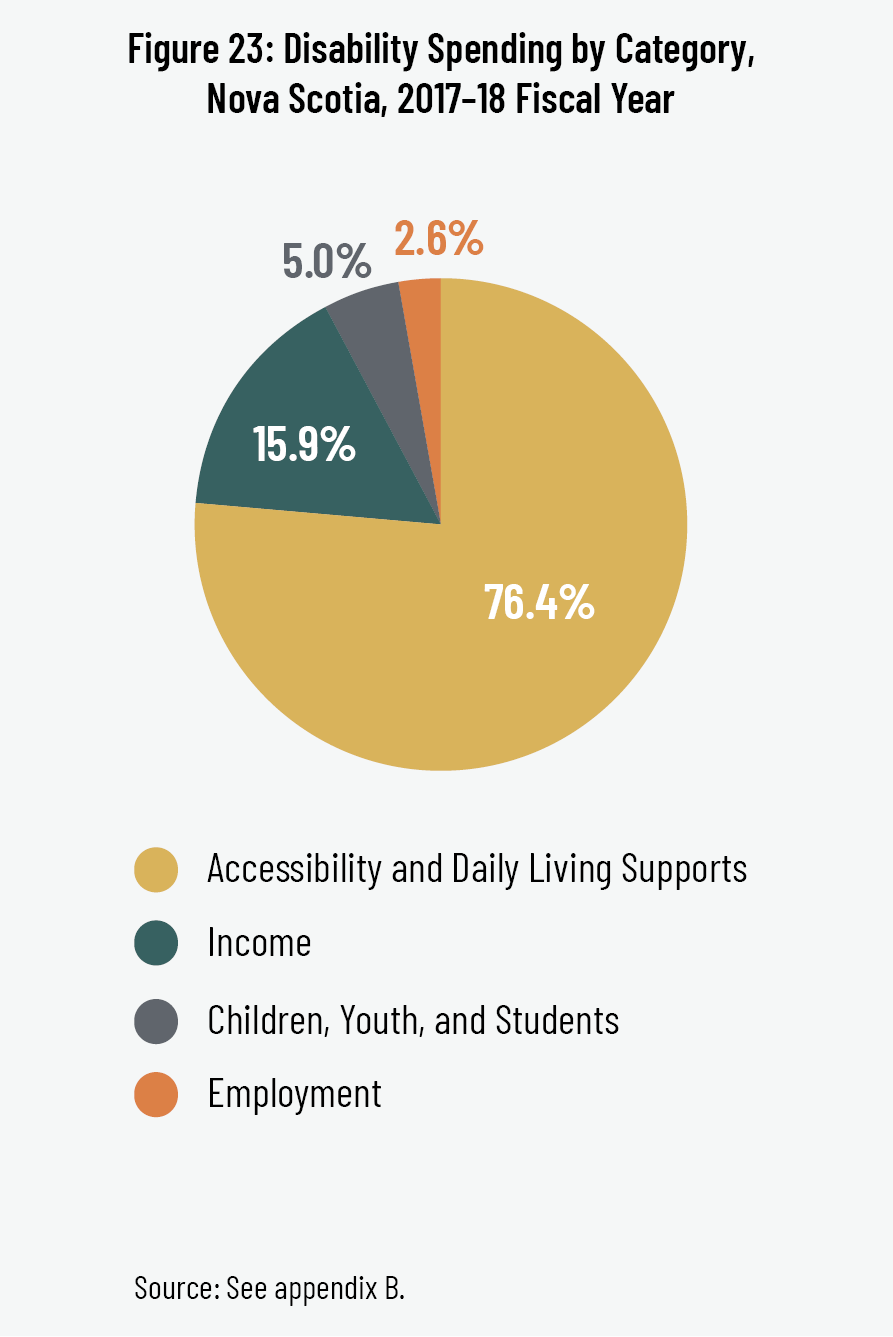

We review federal disability-related programs and find a similar expenditure pattern for 2019–20: 116 116 While more recent data were available in some cases, we used 2019–20 data because they precede the large fiscal impact of COVID-19 containment and relief measures, and as such offer a more accurate reflection of typical government spending patterns. While we made every effort to include all disability-focused programs that were in operation at the time of writing in our analysis, expenditure data were not available for all programs. nearly $8 billion—90 percent of Canada’s total annual disability spending at the federal level—is dedicated to income support, compared to just $414 million, or 5 percent, on programs promoting employment.

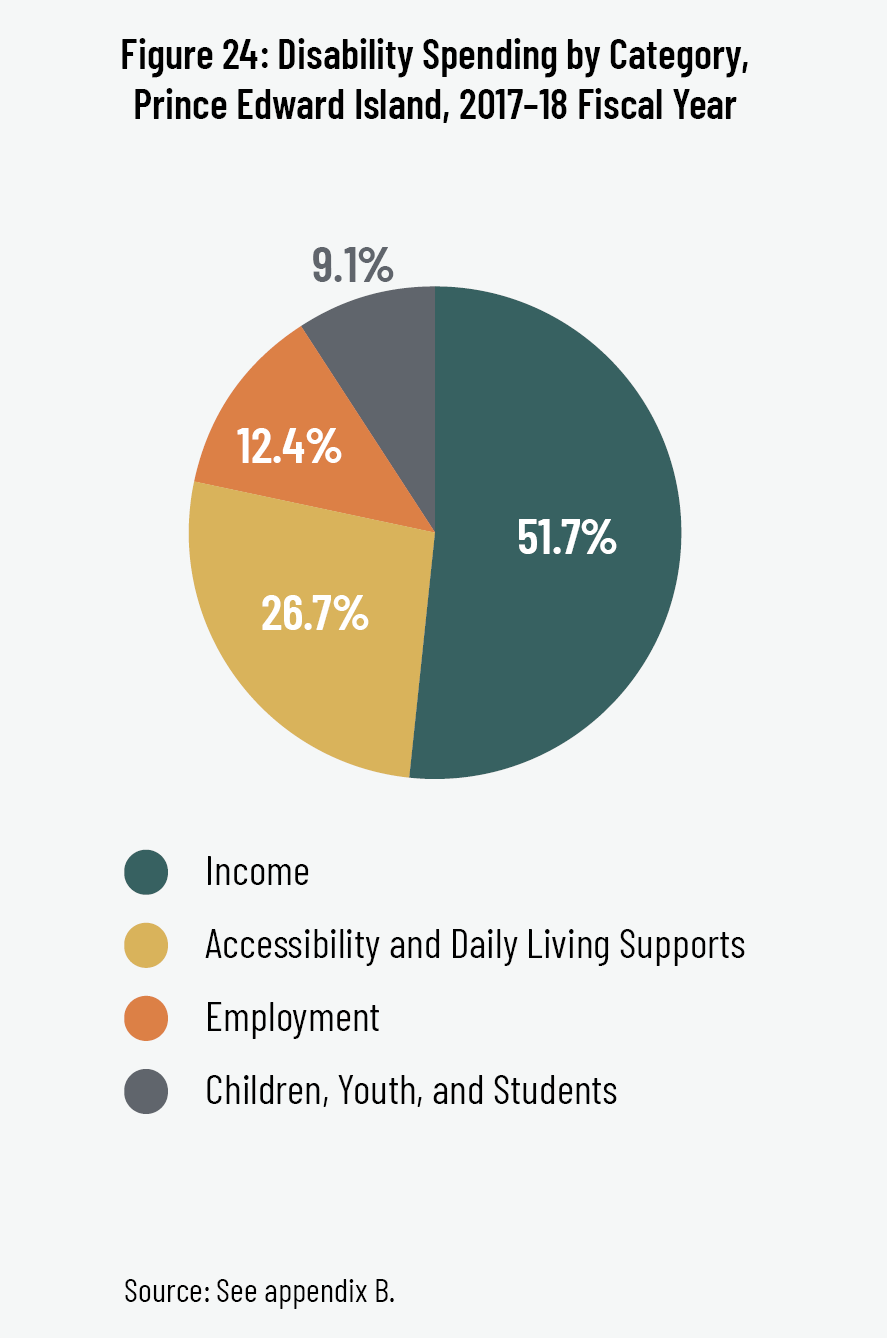

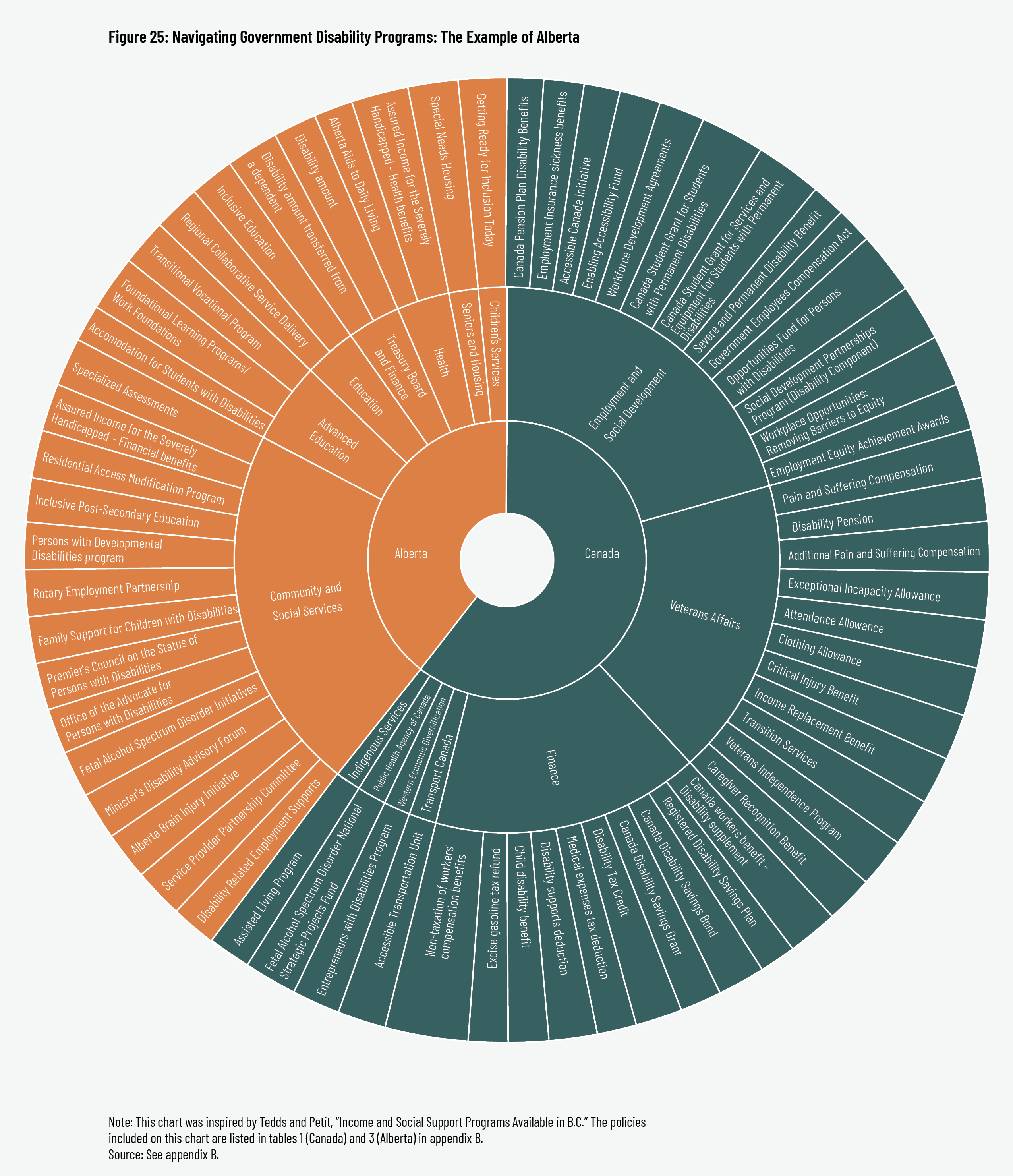

We also examine spending data at the provincial level. Our estimates reveal a similar, albeit in some cases less severe, imbalance in government spending on disability. While spending data were not available for all programs and provincial spending patterns vary, none of the provinces we examined spent anywhere near as much on employment programs as they did on income assistance. 117 117 Since 2019–20 data were not available for Quebec and the Maritime provinces, we use 2017–18 data. Newfoundland and Labrador is not included because financial information was not available for any of its income support programs. For provincial disability policy information, we are indebted to Finlay, Dunn, and Zwicker, “Navigating Government Disability Programs Across Canada,” particularly for Quebec and the Atlantic provinces. For British Columbia, we are indebted to L. Tedds and G. Petit, “Income and Social Support Programs Available in B.C.,” 2019, http://bc-programs.surge.sh/. See appendix B for program lists, data, and calculation details.

Yet persistent high poverty rates among people with disabilities suggest this income-focused approach has thus far failed to achieve either goal. Has a disproportionate focus on benefits inadvertently furthered the exclusion of people with disabilities from employment opportunities that would reduce their risk of poverty? Some researchers have found a link between generous (relative to other pillars of the social safety net) disability-benefit systems and lower labour-market participation for people with disabilities. 118 118 Lindsay et al., “Participation of Under-utilized Talent,” 3. To what extent has governments’ default, “first-resort” approach to supporting Canadians with disabilities—that is, offering them indefinitely and in most cases, inadequate income assistance—hindered rather than helped when it comes to securing the meaningful jobs people with disabilities say they want? 119 119 For an examination of the ways in which provincial social assistance has come to function as the first-resort program for Canadians with disabilities, see M.J. Prince, “Entrenched Residualism: Social Assistance and People with Disabilities,” in Welfare Reform in Canada: Provincial Social Assistance in Comparative Perspective, ed. D. Béland and P.M. Daigneault (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015), 289–304.

There is some evidence from European nations’ reforms to suggest that replacing cash-oriented programs with reasonable pro-work programs will not send people with disabilities into poverty but may actually improve their economic position by allowing them to return to work (and earn income) with reasonable levels of support. 120 120 Burkhauser et al., “Disability Benefit Growth and Disability Reform in the US,” 26. If a pro-work policy is, as we have argued, most in line with human needs, how can income-support programs work with employment programs to advance that goal? How should various levels of government allocate public dollars across different programs to best meet the diverse needs of people with disabilities?

Key Questions for Sound Policy

- To what extent, if any, do existing cash benefit programs for people with disabilities act as a barrier to employment and long-term economic security? To what extent, if any, do cash benefit programs act as a springboard into employment and long-term economic security?

- What balance of disability-related spending—that is, between income supports, employment supports, and other programs—would allow governments to offer the most effective investment in the long-term personal, social, and financial well-being of people with disabilities?

In What Ways Does the Income-Support System for People with Disabilities Act as Both a Direct and Indirect Barrier to Employment?

Of course, developing and implementing effective pro-work policy is easier said than done. If people with disabilities are only able to find a low-paying job, lose their job, or are unable to find a job at all, they will have to turn to the welfare system to make ends meet. Yet disability-income-support programs can quickly become a significant barrier to employment. 121 121 Kirsh et al., “From Margins to Mainstream,” 398. When income assistance is only available to those who declare themselves unable to work, it creates an incentive for recipients to stay out of the labour market in order to continue receiving the support they need to get by. In addition, many benefits are clawed back as a recipient’s income rises, which incentivizes working fewer rather than more hours. 122 122 Prince, “Entrenched Residualism,” 298; Haveman and Wolfe, “The Economics of Disability and Disability Policy,” 1021; Galer, “Life and Work at the Margins,” 6–7. The income-support system thus can perpetuate a cycle of unemployment and lock recipients out of the labour market. 123 123 Galer, “Life and Work at the Margins,” 6–7. The situation is further complicated by the fact that different disability income systems have different approaches to returning to work, as John Stapleton explains: “The clear irony is that contributions-based programs [e.g., the CPP/QPP disability component, worker’s compensation, private insurance] generally do not provide income support when a recipient returns to work (except through specific return-to-work incentives and limited capped allowable earnings), while social assistance, which serves people who have traditionally been too disabled to work, robustly supports entering the workplace with money, supports, and benefits.” 124 124 Stapleton, “The ‘Welfareization’ of Disability Incomes in Ontario,” 7.