PROCUREMENT HAS LONG BEEN THE realm of bureaucrats. They quietly and competently go about purchasing goods required for the public good in ways that align with the responsibilities of governments and in the interest of the public. It is not typically the stuff that makes headlines.

In recent months, however, construction procurement has made headlines in Ontario, Manitoba, and British Columbia.

In May, the government of Manitoba moved to ensure that government projects would be tendered according to procurement best practices, and legislated that “in evaluating bids, a public sector entity must not use, as evaluation criteria, whether the bidder employs unionized employees, non-unionized employees or a combination of the two.”

1

1

“Bill 28: The Public Sector Construction Projects (Tendering) Act,” Legislative Assembly of Manitoba, https://web2.gov.mb.ca/bills/41-3/b028e.php

The legislation was an attempt to rectify the use of previous legislation that allowed project labour agreements on past government contracts to contain clauses requiring contractors to affiliate with, or pay dues to, a subsector of construction unions, and to prevent companies with different labour models from completing public works.

2

2

For details on those previous arrangements, see Brian Dijkema, “Open Tendering Briefing Note,” Cardus Work and Economics,

May 21, 2013, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/open-tendering-briefing-note/

And in Ontario, headlines emerged this spring about the negative effects of restrictive tendering on municipalities, and its effects on municipal budgets and local construction markets. 3 3 Waterloo Region’s Construction Bidding Process ‘Unfair’ and ‘Uneconomic’: Report,” CBC News, March 1, 2018, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/kitchener-waterloo/region-waterloo-construction-tendering-unfair-cardus-1.4556977. And recent comments by the new premier have indicated that they too are moving in the direction of a return to competitive tendering in government procurement. 4 4 “Pencils to Paper: Doug Ford to Tender Bids for All Government Operations,” Global News, June 8, 2018, https://globalnews.ca/video/4262410/pencils-to-paper-doug-ford-to-tender-bids-for-all-govt-operations; as well as video from one of the unions that arecurrently disqualified from bidding in Toronto: LiUNA! Local 183 (@liuna183), Twitter, June 5, 2018, 6:12 p.m., https://twitter.com/liuna183/status/1004169029886435328.

The latest headlines to emerge are from British Columbia, whose government is in the midst of modernizing its procurement practices—many of which do need updating. But in doing so it has also signalled the possibility that it will use that process to provide preferential treatment for companies affiliated with certain unions. 5 5 Vaughn Palmer, “Horgan to Pay It Forward with Projects for Trade Unions,” Vancouver Sun, March 9, 2018, https://vancouversun.com/opinion/columnists/vaughn-palmer-horgan-to-pay-it-forward-with-projects-for-trade-unions.

Suddenly, the issue of public procurement— typically the domain of competent, quiet, apolitical civil servants—has been thrust into the political limelight and in the media.

The possibility that certain companies will be given preferential treatment because of their union affiliation, or that community-benefits agreements would be structured in such a way as to tilt the balance in favour of one labour model, has led to a series of tit-for-tat op-eds by various players in the construction industry.

And central to that debate are various assertions about the ability of various contractors, with various labour models, to complete work on time and on budget (or not). A recent editorial in the Times Colonist is a case in point. Tom Sigurdson, executive director of the BC Building Trades highlighted four open-shop projects in British Columbia that went over budget, 6 6 Open-Shop Projects Went Way Over Budget,” Times Colonist, June 28, 2018, http://www.timescolonist.com/opinion/letters/openshop-projects-went-way-over-budget-1.23350905. while others have noted that the project touted as an example of the success of procurement which favours the Building Trades itself went way over budget. 7 7 Chris Gardner, “Horgan Needs to Rethink Project Labour Agreement Intentions,” Vancouver Province, November 12, 2017, republished in The Independent, https://www.icbaindependent.ca/2017/11/12/oped-horgan-needs-rethink-project-labour-agreement-intentions/.

What are we to make of this?

This purpose of this paper is to offer a cleareyed look at these assertions and to show that the reliance on lists of projects that went over under-budget on a case-by-case basis is not the best means to evaluate government construction procurement practices. Instead, we will show—using industry benchmarks and best practices—a better view of evaluating procurement practices, and also the effects that diversion from these best practices can have on the industry, workers, and the public good.

PICKING CHERRIES VERSUS SOUND PRACTICES AND INSTITUTIONS

WHAT THE METHOD THAT SIGURDSON and others are employing—the listing of projects that go over budget done by companies affiliated with one type of labour model or another—misses is the fact that a lot of construction projects and contracts (especially big ones) go over budget. The issue, according to scholars, is endemic. University of Toronto scholar Matti Siemiatycki and others note that cost overruns and delays are “a problem that unites the nation” and that they pose “a global challenge,” 8 8 Matti Siemiatycki, Andy Manahan, Ehren Cory, and James Purkis, “Over Budget and Behind Schedule: The Causes and Cures of Infrastructure Cost Overruns,” Institute of Municipal Finance and Governance, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, January 21, 2016, https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/imfg/uploads/335/imfg_event_presentation_costoverruns_mattisiemiatycki_jan21_2016.pdf. with huge percentages of projects going significantly over budget on an ongoing basis.

And lest anyone think that this is simply a problem in the public sector, University of Calgary scholar George Jergeas has shown that the problem is also endemic to megaprojects in the private sector, including those done by highly sophisticated, global companies that are traded on public stock exchanges. 9 9 George F. Jergeas and Janaka Ruwanpura, “Why Cost and Schedule Overruns on Mega Oil Sands Projects?,” Practice Periodical on Structural Design and Construction 15, no. 1 (2010): https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/%28ASCE%29SC.1943-5576.0000024.

At the same time, it is also true that many projects completed by union, non-union, and alternative union firms are completed on time, and on budget, or even ahead of time and ahead of budget. A line-by-line review of each project completed in Canada will produce a range of results, and anyone can cherry-pick their preferred examples.

It is important to remember the bigger picture of what it takes to build any project, but especially public construction projects.

It is important to remember the bigger picture of what it takes to build any project, but especially public construction projects. There is absolutely no doubt that skilled trades workers are integral to public projects. A construction company without skilled carpenters, electricians, scaffolders, labourers, or any of the other trades is an oxymoron. But workers alone don’t build projects. It is construction firms—a broader endeavour consisting of skilled trades, capital, accountants, engineers, estimators, logistics managers, safety officers, and many other moving parts—that build projects. Labour matters; it’s a big part of cost, but it’s not the only cost. And likewise, labour is not simply a cost; it is also a function of the productivity of the firm. Different firms organize and deploy workers in different ways.

This means that issues of how workplaces are organized, the amount of workers deployed, the skill and experience of those workers, their ability to work safely, and many other things can add costs; but it can also increase efficiencies and productivity. Some firms will be better at deploying their workforces than others. And that applies to union, alternative union, and non-union firms in different ways.

As noted by Ray Pennings already in 2003:

There is a continuum of organizational models, with the pure craft model on one side and a pure multi-craft, wall-to-wall model on the other. Today the presence of multiple labour pools [traditional craft unions like the BC Building Trades, alternative unions like CISIWU, CLAC, CWU, organized non-union pools like ICBA] available to major construction projects is simply part of the construction marketplace. A construction buyer can put out a tender and realistically expect three bidders who will each employ a different labour pool and model if they win the project. 10 10 Ray Pennings, “Competitively Working on Tomorrow’s Construction,” Cardus Work and Economics, July 1, 2012, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/competitively-working-in-tomorrows-construction/.

Fair, open, competitive, transparent—all of these matters are articulated not by some narrow interest group, but as core principles that stand behind public procurement.

That reality is even truer in British Columbia— and indeed everywhere in Canada west of Quebec—today than it was a decade ago. And as we noted in 2008, these pools have emerged in response to realities and changes within the construction market as a whole, including changes within traditional models. 11 11 Ray Pennings, “Why Is Construction So Competitive in Ontario?,” Cardus Work and Economics, November 25, 2008, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/why-is-construction-so-expensive-in-ontario/.

In fact, a look at a recent ranking of Canada’s “Top 40” construction companies shows this reality. On-Site, a leading construction magazine, produces an annual list of Canadian construction companies with the largest revenues. 12 12 “The Top 40,” On-Site, June 2018, 3, https://www.on-sitemag.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/31/2018/06/ONSITE_TOPCONTRACTORREPORT-2018.pdf. Among the top ten companies listed, every single one of them has workers who have chosen to affiliate in some way with alternative unions in some jurisdiction in Canada, including British Columbia (FIGURE 1).

Other companies on the Top 40 list are affiliated entirely with traditional unions; others have various aspects of their business that are affiliated in different ways, in different trades, in different jurisdictions, with both traditional and alternative unions; some have portions of their workforce that are unaffiliated. The basic point is that a variety of highly successful companies—all of which do public work in various jurisdictions across the country—work with a variety of labour models to deliver value to their customers (FIGURE 2).

THE HEART OF THE ISSUE

WHAT THE DEBATE IN BRITISH COLUMBIA about projects going over or under budget is really about is how—under what structures—the government should adjudicate between the various value propositions brought by each model when they tender public work. On what principles should they be guided while doing so? In the case of British Columbia, the principles are articulated clearly in its comprehensive Core Policy and Procedures Manual, which sets the “policy for all aspects of procurement of goods, services and construction, including: planning; pre-award and solicitation; contract selection and award; contract administration and monitoring; evaluation and reporting.”

What are those principles?

The following objectives for government procurement of goods, services and construction are based on the principles of fair and open public sector procurement: competition, demand aggregation, value for money, transparency and accountability. 13 13 “CPPM Policy Chapter 6: Procurement,” British Columbia, Provincial Government, https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/policies-for-government/core-policy/policies/procurement?keyword=procurement&keyword=policy#6i1 (emphasis added).

Fair, open, competitive, transparent—all of these matters are articulated not by some narrow interest group, but as core principles that stand behind public procurement.

It is competition among an array of different firms that drives value.

In British Columbia, as it was in Manitoba, and as it is in Ontario, the question that is cloaked by media disputes about various projects that go over or under budget is whether it is in the public interest that the government should structure procurement in a way that favours one particular model of labour relations or another. Put differently, the question is whether a government should or should not use the affiliation of a given firm as a criteria for evaluating bids on public work.

And, on that front, one of Canada’s leading procurement experts notes,

membership in a particular trade union does not provide an objective criterion for the purposes of public procurement. Trade union membership is a function of the choices of particular members and does not signify that any objective standard of qualifications has been met by union members. In this way, union membership cannot be relied upon as an industry standard in the same way as membership in a regulated profession or even in a trade association can. Furthermore, union membership is often localized to certain geographic areas. To restrict potential bids in a public procurement process to members of such an organization would mean eliminating a great deal of potential competition on the basis of geography alone. And, as we noted above, restricting competition leads to higher prices. 14 14 Stephen W. Bauld and Brian Dijkema, “Hiding in Plain Sight: Evaluating Closed Tendering in Construction Markets,” Cardus Work and Economics, September 9, 2014, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/hiding-in-plain-sight-evaluaingclosed-tendering-in-construction-markets/.

To return to the key economic point, it is competition among an array of different firms that drives value.

Within a given firm, the price for a given project is an emergent property of the workers doing the building, the engineers, the logistics planners (those steel girders have to come from somewhere and have to arrive on time for the steelworkers to be productive), the state of the market (in slow times, companies may be willing to take smaller profits to maintain workforces), the profit motive of the company (private firms have different obligations than publicly trades ones), those who do the financing (maybe one company can leverage size or relationships to secure cheaper financing), safety records, insuring and all other aspects of the hugely complicated business of building major infrastructure projects that determines value, cost, and all the rest of it. Firms working in different sectors develop different specialities—some firms, for instance, may specialize in building hockey arenas. Others may excel at water treatment plants. And as the firms develop this expertise, they can tune their operational structures to lower costs for owners while still making a profit. Having a diversity of labour pools changes the composition of firms in ways that introduce unique possibilities for efficient, effective, safe work (FIGURE 3).

So when governments use the procurement process or other tools to favour or disqualify any labour model, it does not just favour or disqualify a given set of workers on the tools, it stacks the deck in favour of certain firms. It picks between businesses on the basis of one aspect of their work. Disqualifying a set of firms because their frontline workers choose one labour model over another is akin to disqualifying a firm because they get financing from RBC rather than TD, or from the Canada Infrastructure Bank rather than, say, a pension plan. To quote a scholarly journal that focuses on anti-trust issues: “Although the economic crisis has prompted some policy-makers to reconsider basic assumptions, the virtues of competition are not among them.” 15 15 Maurice E. Stucke, “Is Competition Always Good?,” Journal of Antitrust Enforcement 1, no. 1 (2013): 162–97, https://t.co/u9iX8DeXD1.

Even taking the most modest of estimates related to additional costs that arise from restricting bidders based on union certification would result in almost a billion dollars worth of savings.

Again, it is competition among a diverse pool of bidders that itself brings a diverse set of elements to their bids that brings value to taxpayers. Reducing that diversity not only puts upward pressure on prices—our studies comparing bidding data in diverse versus non-diverse jurisdictions shows those upward pressures to increase the gaps between winning bids and next bids by over 100 percent, 16 16 Morley Gunderson, Tingting Zhang, and Brian Dijkema, “Up, Up, and Away,” Cardus Work and Economics, December 6, 2017, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/up-up-and-away/. and adds anywhere from 8 to 25 percent on costs 17 17 Brian Dijkema and Morley Gunderson, “Restrictive Tendering: Protection for Whom?,” Cardus Work and Economics, January 17, 2017, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/restrictive-tendering-protection-for-whom/. —but also undeniably leads to a reduction in the diversity of the contractors able to perform public work with the labour model their workers choose. Our research shows that restricting bidding based on union affiliation reduced the pool of bidders by eighty four percent. 18 18 Brian Dijkema, “No Longer the Best: The Effects of Restrictive Tendering on the Region of Waterloo,” Cardus Work and Economics, March 1, 2018, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/no-longer-the-best-the-effects-of-restrictive-tendering-onthe-region-of-waterloo/.

To use an analogy from the world of ecological conservation, restricting the diversity of approaches by contractors leads to a type of shifting baseline syndrome; “the phenomenon whereby severe ongoing losses (e.g. in biodiversity) are normalised in the minds of each new generation, thus redefining the ‘natural’ according to an impoverished standard.”

19

19

I’m grateful to the phenomenal Robert MacFarlane for alerting me to this term. Robert Macfarlane (@RobGMacfarlane), Twitter,

May 22, 2018, 11:00 p.m., https://twitter.com/RobGMacfarlane/status/999168127740104705.

In the long run the construction industry as a whole becomes less diverse and innovative. It is thus not simply a matter of economics, but of the health of the diverse set of institutions that provide the conditions for sound markets that can build the infrastructure necessary to help British Columbia and other jurisdictions thrive.

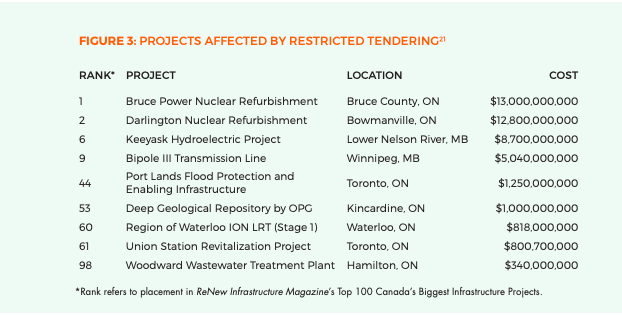

A review of another industry list brings the broader social picture to light. ReNew Canada: The Infrastructure Magazine, produces an annual “Top 100” list, which highlights the one hundred biggest infrastructure projects in Canada. 20 20 "Top 100 Projects for 2018,” ReNew Canada: The Infrastructure Magazine, https://top100projects.ca/2018filters/.

The top two projects in Canada—the Bruce Power Nuclear Refurbishment and the Darlington Nuclear Refurbishment, worth a combined $25.8 billion—are both subject to closed tendering based on union affiliation. Other major projects, including Keeyask Hydroelectric Project on the Lower Nelson River in Manitoba ($8.7 billion), the Bipole III transmission line ($5.04 billion) in Winnipeg, the Port Lands Flood Protection and Enabling Infrastructure ($1.25 billion), the Deep Geological Repository by OPG in Kincardine ($1 billion), Stage 1 of the Region of Waterloo ION LRT ($818 million), Union Station Revitalization Project ($800.7 million), and the Woodward Wastewater Treatment Plant ($340 million). This does not include projects where the city of Toronto (currently under significant restrictions) is a partial owner, or is involved in ancillary construction (as it is on some Metrolinx projects, which constitute a major portion of major projects in Ontario), or on non-ICI work (like the $2.44 billion Gardiner Expressway rehabilitation) (FIGURE 3). 21 21 The Manitoba projects listed here are subject to closed tendering for existing work per section 4 of Bill 28: The Public Sector Construction Projects (Tendering) Act,” Legislative Assembly of Manitoba, https://web2.gov.mb.ca/bills/41-3/b028e.php which states “Nothing in this Act limits or affects the operation of an agreement, including a collective agreement, to which a public sector entity is a party that is in effect on the day this Act comes into force.” See Bill 28: The Public Sector Construction Projects (Tendering) Act,” Legislative Assembly of Manitoba, https://web2.gov.mb.ca/. Conversely, the Region of Waterloo, subject to closed tendering since 2014, tendered work for its ION LRT when the Region was open. We include it here now as any future work related to LRT that is owned by the Region will be subject to closed tendering.

All told, about $43.75 billion worth of work is currently under restrictions in Canada, and that just from a list of the largest projects. It grows as you take into account the billions of dollars worth of smaller projects that don’t make this list. Even taking the most modest of estimates related to additional costs that arise from restricting bidders based on union certification would result in almost a billion dollars worth of savings. 22 22 43.75 billion x 2% = 875 million. However, the city of Toronto’s estimate of 2 percent is almost certainly erroneous as we show here: Brian Dijkema, “Tuning Up Ontario’s Economic Engine: A Cardus Construction Competitiveness Monitor Brief,” Cardus Work and Economics, April 9, 2015, https://www.cardus.ca/research/work-economics/reports/tuning-up-ontarios-economic-engine-a-cardus-construction-competitiveness-monitor-brief/.

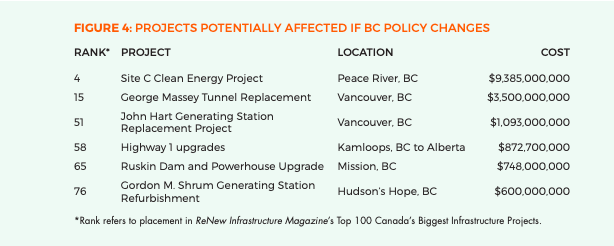

Hypothetically, if British Columbia were to move to restrict bidding on projects in which it, or BC Hydro, is the owner, and we were to account simply for those projects listed in the top one hundred, we would add $9.385 billion for the Site C Clean Energy Project, $3.5 billion for the George Massey Tunnel Replacement project, $1.093 billion for the John Hart Generating Station Replacement Project, $872.7 million for Highway 1 upgrades from Kamloops to Alberta, $748 million for the Ruskin Dam and Powerhouse Upgrade, $600 million for the Gordon M. Shrum Generating Station refurbishment, which would account for an additional $16.2 billion of projects in British Columbia alone (FIGURE 4). The low estimate of 2 percent means an additional $324 million of additional funds needed to complete these projects. Adding the more likely range of 8–25 percent additional costs to these projects would add $1.3–4.05 billion onto British Columbian citizens’ shoulders. Effectively, British Columbians would be losing out on costs equivalent to two generating stations up to an additional George Massey tunnel. It is the loss of this broader social capacity that highlights the underlying social problem with closed tendering.

IT’S THE MORALITY, STUPID

THIS BROADER SOCIAL LENS BRINGS clarity to another, more basic problem: the moral case that workers should not be penalized for their private choices, and that companies should not be penalized for the freely exercised rights of its workers.

Workers have a constitutional right to associate with whomever they wish. We have labour boards to adjudicate whether they’ve done so properly. It is the provincial labour board’s responsibility to determine whether the choices of workers were made freely. If they aren’t, they have legislative authority to impose penalties. That is the appropriate venue for determining issues of labour relations. The government, in its purchasing procedures, should not—cannot—penalize workers for exercising that right.

Workers have a constitutional right to associate with whomever they wish…The government should not penalize workers for exercising that right.

Governments have a legal, but more importantly a moral obligation and responsibility to treat all of its citizens equally, and to provide neutral space for the existence of a plurality of institutions that operate freely according to the interests of their members. To disqualify a firm whose workers have made a choice to join one union or another is completely contrary to the purpose of government, whose job it is to rule for all, and which has a constitutional obligation not to discriminate against people for exercising their rights.

Cardus has noted in the context of Ontario that polarizing the labour relations environment with massive swings that change with each successive left or right government accomplishes little for workers, the economy, and society as a whole.

This is the cumulative effect of 10 years of rocking the boat left then right. Some may argue we have more balance than before. But balance in labour relations is very much in the eye of the beholder. Rather than moving the province towards a more cooperative, democratic approach based on mutual trust and respect, the changes, if anything, have intensified an already hostile labour relations atmosphere. . . .

Across the political spectrum, most agree that the relative merits of a market economy far outweigh those of a managed economy. Most would also suggest market values alone should not determine labour and living standards. Labour is not just another factor of production. Considerations other than just supply and demand must be brought to bear when dealing with fellow human beings. 23 23 Ray Pennings, “Has Harris Really Changed Things?,” Comment, May 1, 2001, https://www.cardus.ca/comment/article/has-harrisreally-changed-things/.

Ultimately, it is this that lies at the heart of debates about closed tendering. And it would behoove those who govern to keep this in mind as they consider how to build their provinces to serve the good of all, not just a few.