Introduction

We’re almost there! The pandemic’s terrible toll on people’s lives and our country as a whole is coming close to an end. Notwithstanding the talk of a few doomsayers, Canadians are getting out to local clinics, pharmacies, hockey arenas, and other venues in order to roll up their sleeves for the one thing that will ultimately crush COVID-19’s deadly threat: vaccines.

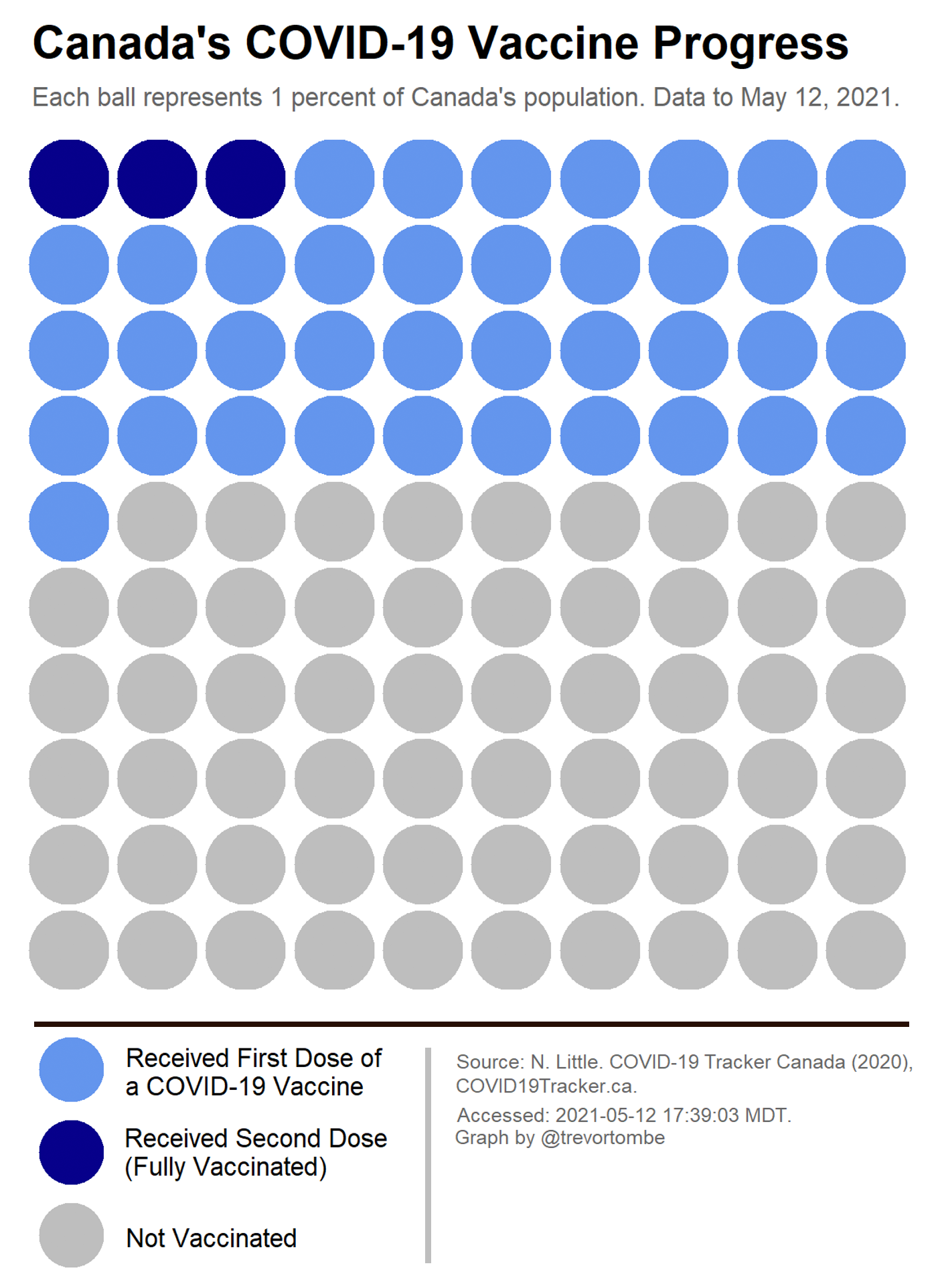

University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe, who is doing an extraordinary public service with his daily graphical representations of Canada’s vaccine progress, produced a graph this week that shows just how far we have come.

We’re getting very close to having half of our population vaccinated with their first dose, and given the pace at which vaccine supplies are now arriving, it’s likely that the dark blue dots will start to increase quickly as well. Tombe’s reaction was absolutely correct:

The key at this stage of the game is to keep our eye on turning that final ball into the sweet, soothing blue of pandemic freedom that comes with herd immunity. That outcome will depend on two separate yet related factors: sustained levels of vaccine supply, and ongoing high rates of vaccine demand. There’s some evidence in the United States, for instance, that the latter is now a bigger impediment than the former to reaching herd immunity.

As we start to resolve our own vaccine-supply challenges, there’s now a need for Canadian policymakers to think about how public policy can boost vaccine demand among a share of the population that isn’t opposed to vaccinations but may not be motivated, either. There could be various factors contributing to their ambivalence, including confusion, complacency, and competing family and work demands. Reaching this cohort will be crucial to completing Tombe’s infographic and achieving broad community protection from the virus.

Thinking Like an Economist

How to think about the role for public policy to target this ambivalent group can draw on economic theory and concepts. As a group of Canadian economists (including Tombe) observed in a recent Globe and Mail op-ed, getting a vaccine isn’t just something that protects you (though it does!), but it has positive knock-on effects that protect others as well. This gap between private and public benefits is what economists call “positive externalities.”

It’s broadly accepted that there’s a role for public policy to close such a gap. This is the typical policy rationale for child benefits, post-secondary student grants, and various other policies and programs that increase the supply of and demand for goods, services, and resources that generate external benefits.

There are obvious implications for our vaccination efforts. If we hit a wall of vaccine ambivalence, we’ll lose the cumulative benefits of more and more people getting vaccinated, and our progress toward defeating the pandemic will stall. The result will be a slower emergence from lockdowns, unnecessary deaths, continued expansion of our medical backlogs that are already threatening lives, continued economic pain, and kids who remain unable to head back to school. In short, individual choices will necessarily affect (and possibly harm) our collective ability to return to normal.

We need to avoid the phenomenon of ambivalence that’s setting in elsewhere around the world, and which has led to a slowing of the pace of vaccinations. We don’t want to hit a vaccination wall. We need to use the tools of economics to target and incentivize ambivalent Canadians to get vaccinated.

Thinking for the Common Good

Economics isn’t the only field, however, that offers policymakers insight on how to address the challenge of vaccine ambivalence. We’d argue that moral considerations are just as important for thinking about the proper messaging and policy design for vaccine-related incentives. We cannot just appeal to homo economicus. As we outline in the next section, an effective framework for vaccine-related communications and policy must also account for people’s instincts toward social solidarity.

The idea of social solidarity is most often equated with the trade-union movement, but it has deeper roots and broader application than the world of organized labour. In our North American context, we have become so used to thinking solely in terms of individual rights that we too often neglect to consider the objective reality that those rights are socially situated and rely on a vast network of social relationships to flourish. And we often neglect to consider that rights, while good in themselves, take on their fullest meaning only when they extend beyond the simplistic “I’ll do what I want, and no one can tell me what to do.” Our individuality emerges out of a rich web of social relations—starting with our family, but extending to our friends, our neighbourhood, schools, and other communities that we are part of. To paraphrase John Donne, no one is an island. Solidarity is to act in accordance with this fact, to join with other members of society to achieve a good that we hold in common and that we can achieve only by acting together.

In order to achieve herd immunity we have to reach a point where enough individuals become immune (through vaccinations) so that “the whole community becomes protected, not just those who are immune.” Herd immunity is the common good that we are seeking in this situation, and the public-health effort of vaccination will work only if there is a high degree of solidarity among Canadians, especially those who aren’t at high risk of serious illness or death from COVID. Moreover, while efforts of solidarity often require tremendous sacrifice (think of Canadian soldiers who fought in Europe during World War II, in behalf of people they never met), vaccines are a relatively low-sacrifice effort.

Canada needs a significant and positive policy and communications effort to reinforce the individual and collective good that will come as a result of people getting vaccinated, one that does so in a way that provides people with a moral incentive—namely, that getting a vaccine is an act of social solidarity, or, to use a biblical frame, one way to love your neighbour as yourself.

Governments should lead with public communications efforts that give people a glimpse of life on the other side of the pandemic. There’s lots to gain from everyone getting vaccinated. Show the public what’s coming—including weddings, hugs from grandparents, and drinks with friends in a pub!

But moral incentives matter, too, and it’s worth reinforcing these with material incentives. Yes, vaccines are their own reward, and yes, getting them is good for your neighbour also, but given the collective downsides of a vaccination wall, and given the massive gains to be had from herd immunity, why not offer a foretaste of the material rewards that come from beating the pandemic, so that all of us can get there faster? And why not do this in a way that capitalizes on human nature’s responsiveness to calls for solidarity and collective purposes?

Designing a Material and Moral Incentive

So how might we do this?

Various jurisdictions and institutions are experimenting with forms of material and individualistic incentives to encourage people to get vaccinated. As journalist Sean Boynton recently reported for Global News, American governments are offering everything from free beer to lottery tickets for those who get vaccinated. The state of Ohio, for instance, even announced a new, weekly $1 million lottery to encourage people to get their shots. Other governments are offering public servants cash payments of $100 to get theirs.

Closer to home, we’ve seen hints of businesses and other civil-society institutions offering their own material incentives. One particularly inventive and positive example is the University of Lethbridge, which is offering students a chance at winning a free year of tuition if they are vaccinated. We need more of this encouragement from the private sector and government to boost the positive externalities of vaccinations.

While some might be dubious about more public spending at a time of unprecedented budget deficits, this one is arguably the most productive expenditure that governments could undertake.

Almost any incentive program is likely to cost significantly less than the cost of providing ongoing pandemic relief to businesses and households (the wage subsidies alone have cost the federal treasury more than $100 billion). But it should also reduce the lost economic output from ongoing public-health restrictions. There’s massive value to be gained for our economy by reaching herd immunity months, weeks, or even days faster, and we should not be shy to spend even large amounts of public monies to help get there.

The good news is that incentives appear to work. A major research paper in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, published in advance of Australia’s implementation of vaccine-related incentives, reviewed the literature on incentive programs in the UK, the US, and other places around the world and concluded that “all studies reviewed showed that incentives have a positive influence on immunization uptake.”

Canada’s own C.D. Howe Institute’s research of Australia’s experience with vaccine-related incentives finds that after implementing incentives, “Australia’s immunization coverage has improved dramatically, exceeding 90 percent for all recommended vaccines.” The authors note that “financial incentives, while a blunt instrument, also might be an effective option” for increasing vaccinations, “especially if other approaches are failing.”

But research also indicates that there are limits to material incentives on their own. Individualistic appeals may not be sufficient to induce a behavioural response for the betterment of the broader society. One study, for instance, notes that “considerable research shows that payments in some contexts can send the signal that an action is undesirable, unpleasant, or even dangerous and not worth taking based purely on personal benefit” and that “financial incentives are likely to discourage vaccination (particularly among those most concerned about adverse effects); instead, contingent nonfinancial incentives are the desired approach.”

The takeaway here is twofold: 1) incentives have been shown to have some positive effects on vaccination take-up, but 2) the most effective combination of incentives is one that has financial and non-financial dimensions—or, to put it differently, that appeals to people on material and on moral terms.

There is, in our view, a policy approach that can bridge this gap between studies showing that financial incentives work in the form of tax credits, lotteries, or direct cash payments, and those showing that direct financial incentives cause citizens to think of vaccines as compensation for a loss or injury, which in turn may have an inadvertent yet deleterious effect on public-health efforts. In line with the approach to incentives recommended by late economist Samuel Bowles, we believe that Canadian government(s) should design vaccine-related incentives that put moral solidarity at the heart of all vaccination efforts, with material incentives that also benefit the individual.

Our alternative approach provides a contingent material incentive—in the form of direct cash transfers—while, in the name of solidarity, directly and practically addressing the damages suffered uniquely by two parts of our society: local businesses and charities.

Local businesses have suffered disproportionately from the pandemic lockdowns. Statistics Canada notes that “small businesses were more likely to experience a year-over-year decrease in revenue, and also less likely to take on more debt and adopt or incorporate various technologies.” Over a quarter of small businesses reported revenues down 30 percent or more, while only one-fifth of large businesses reported the same.

Charities—especially local charities—experienced similar declines in revenue and broader capacity. Imagine Canada, an advocacy group for Canadian charities and nonprofit organizations, estimates that charitable revenues were down on average 30 percent overall relative to the previous year. Canada Helps Annual Giving Report projects that overall giving in Canada will be down by 10 percent, dropping to numbers not seen since 2016.

Giving vaccinated citizens money to give to local charities or spend at local businesses can serve both as a personal incentive (who wouldn’t want money to spend at a local restaurant, or feel good giving their gift to a charity in need?) and also as a clear sign of solidarity with their neighbours whom the pandemic has hit particularly hard. As with vaccines themselves, the personal benefit and the public benefit are boosted at the same time.

Provincial governments could provide funding to municipal public-health units that, in partnership with local chambers of commerce and with Canada Helps, which can provide payment services to every registered charity in Canada, could grant those who have received their vaccines with gift cards (or online prepaid credits), which could be spent at local businesses and/or donated to local charities.

How Might Such a Material and Moral Incentive Be Structured

- The incentive should be substantial enough to influence, on the margins, people’s decision to get their vaccines. Given the daily loss of economic output and government revenues (and, in turn, ongoing elevated relief spending) resulting from the pandemic and lockdowns, governments should tend toward the generous.

- The ideal financial incentive is situated at an equilibrium between an amount that will influence individual behaviour and an amount that will encourage incremental personal spending at the point of sale at a local business or charity. That is, the goal should be to both incentivize individuals to get vaccinated and boost their own spending at local businesses or charities.

- A possible benchmark could be set at two to three times the average hourly Canadian wage, which currently stands at approximately $30. The total expenditure per person covers the time it takes to get a vaccine and then effectively doubles it. If such an incentive ($60–$90) was offered to every Canadian, the one-time price tag would be $2.1–$3.15 billion, which is a small fraction of the funds that the government has spent on pandemic-related household and business supports. If the incentive was given only to Canadians over the age of 18, the range would be $1.84–$2.8 billion. It’s plausible to suggest that the net fiscal cost would be significantly lower, after accounting for the likelihood that it would induce incremental consumer spending (think of a household that uses the $60 vaccine-related incentive at a restaurant and then spends another $60 of their own money) as well as accelerate progress towards herd immunity.

- A vaccine-related incentive targeting registered charities could involve governments partnering with Canada Helps to allocate Canadians who get vaccinated to make a donation via its platform. Basically, the government could provide a prepaid grant to Canada Helps, and individuals would get personalized codes to use on the Canada Helps site following vaccination. An incentive targeting local businesses might involve partnerships between local public-health authorities and community businesses. The key would be to design an incentive such that it leads to incremental consumer spending with local businesses.

- Timing will be of the essence. Vaccine-related incentives should be introduced before we experience any significant plateauing of vaccine demand and must be accompanied by a mass communications campaign to encourage broad participation in the collective vaccination effort. The key here is to draw on the evidence and research of people’s instincts toward solidarity and apply it to public policy.

Conclusion

The pandemic has been extremely difficult for Canadians across the country. Policymakers should seize any measure or initiative that can help to end it as soon as possible. The research and evidence tell us that the sweet spot for vaccination demand is the adoption of public-policy incentives that account for both material and moral motivations.

Thus we’ve sought to put forward policy ideas, including vaccinated-related for businesses or charities, that would connect individuals to their communities. The incentive would encourage vaccinations, address an existing policy challenge that local communities face (and that has a broader impact on provinces and the nation as a whole), but it would also encourage citizens to contribute their own funds to that same effort, building social solidarity at the same time. It’s a win-win-win-win.