“New Ontario Mother Discovers She Doesn’t Qualify for Parental Leave Benefits,” read a recent headline on the CTV News website. 1 1 M. Walker, “New Ontario Mother Discovers She Doesn’t Qualify for Parental Leave Benefits,” CTV News, September 17, 2021, https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/new-ontario-mother-discovers-she-doesn-t-qualify-for-parental-leave-benefits-1.5590297. Kaitlin Ward was laid off from her job as a hairstylist during the pandemic and did not accrue sufficient hours to qualify for benefits through the Employment Insurance system. The report noted Ward would be returning to work months sooner than she had anticipated.

The story illustrates the pressure that the pandemic has applied to existing vulnerabilities in Canada’s parental benefits program. Canadians enjoy a more generous plan than their neighbours to the south, yet evidence suggests that the design of the policy contributes to uneven uptake of parental benefits available under Employment Insurance based on socioeconomic status and sex. Calls to reform the program are not new, but recent federal party platforms and a 2019 mandate letter to the Minister of Families, Children, and Social Development indicate a willingness to address parental benefits.

The purpose of this backgrounder is to provide context for conversations at Cardus on the advantages, challenges, and potential reforms needed to improve Canada’s parental-leave benefits policies.

Diverse Interests

Parental-benefit policies serve potentially competing interests. On one hand, policies are intended to attach parents to the paid work-force. On the other, benefit policies provide time for parent-child attachment that is necessary for healthy development and well-being. This tension requires careful consideration when formulating policy options.

Our desire to study this policy issue stems from two primary objectives. The first is to promote policy approaches that embrace a larger conception of the social good of families beyond only economic and labour-force concerns. Second, parental benefits provide time and financial relief for parents to bond with their children, forming deep attachments that are critical for healthy child development. Parental benefits reflect the kind of whole-family approach to children and their development that we believe policies should foster.

At the same time, we recognize that there is a spectrum of motivations for supporting parental-benefit policies. Our intent is to gather diverse perspectives to speak to the issues and challenges in order to envision better federal policy.

Current Federal and Quebec Benefit Policy

Quebec implemented a separate paid-benefit program in 2006. This section provides a brief overview of the federal and Quebec benefits programs.

Federal Maternity and Parental Benefits

While this brief focuses on paid parental benefits, it should be acknowledged that unpaid job-protected leave is regulated by the provinces and territories, and by the federal government in federally regulated industries. For this reason, there are differences in unpaid job-protected leave, including the length of continuous employment required to qualify and the number of weeks’ notice to the employer required before going on leave. Unpaid job-protected leave is not discussed in this brief.

Paid parental benefits, on the other hand, are administered through federal Employment Insurance. In this system, maternity and parental benefits require employees to meet certain qualifications. Employment Insurance premiums and benefits are adjusted annually.

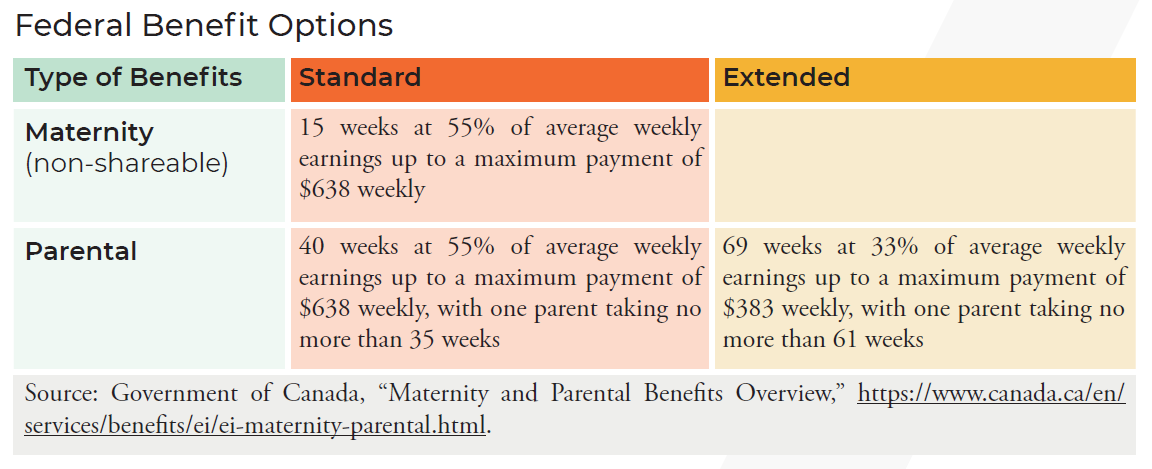

The Employment Insurance maternity benefit provides up to fifteen weeks’ leave at 55 percent of earnings, to a maximum of $638 per week for 2022. Mothers can enroll up to twelve weeks before their due date, or the date they give birth. The maternity benefit cannot be shared with the other parent.

Parents can share the parental benefit, claiming the benefit at the same time or consecutively. Mothers can claim the parental benefit after the week the child was born. Parents can also choose from the standard benefit or extended benefit. The standard benefit provides coverage up to forty weeks, with one parent eligible to take up to thirty-five weeks. Similar to the maternity benefit, the parental benefit pays 55 percent of earnings, to a maximum of $638 weekly for 2022. The extended benefit covers up to a maximum of sixty-nine weeks, with a maximum of sixty-one weeks taken by one parent. The benefit pays 33 percent of earnings, up to a maximum of $383 weekly.

Prior to the pandemic, any parent intending to take maternity or parental benefits was required to accumulate 600 hours of eligible employment in the previous fifty-two weeks to qualify. The qualifying hours have been reduced to 420 hours in the previous fifty-two weeks, until September 2022.

In 2010, self-employed workers became eligible to participate in Employment Insurance special benefits including maternity and parental benefits. Self-employed workers must opt in twelve months before claiming benefits and must accumulate at least $7,555 in net income to qualify. The amount of benefits received is based on insurable income in the previous fifty-two weeks, with the highest-earning weeks taken as the standard. To qualify, recipients must have reduced the amount of time spent on their business by more than 40 percent.

Recipients, including the self-employed, can earn limited income while receiving benefits. Parents keep fifty cents of Employment Insurance benefit for every dollar earned, up to 90 percent of previous insurable earnings. Earning over this amount results in a dollar-for-dollar clawback.

In addition, low-income families earning up to $25,921 per year may receive the Family Supplement. The supplement increases the Employment Insurance benefit payment up to 80 percent of the claimant’s average insurable earnings. The amount received is determined by household income and by the number and age of children in the household. The threshold for this benefit has been unchanged since 1997.

Adoptive parents can qualify for the federal parental benefit, but do not qualify for maternity benefits.

Quebec Parental Insurance Plan (QPIP)

Quebec administrates a separate parental benefit program, with some distinct differences from the federal plan.

The QPIP has three categories of worker status: wage earner, self-employed worker, and self-employed wage earner. 2 2 For information on worker status, see Revenu Québec, “Criteria Used to Determine a Worker's Status,” https://www.revenuquebec.ca/en/citizens/self-employed-persons/your-status/criteria-used-to-determine-a-workers-status/. Parents in each of the three categories can qualify by earning a minimum of $2,000 of income during the qualifying period (usually fifty-two weeks), reducing weekly income by 40 percent, or reducing time spent on business activities by 40 percent weekly for self-employed workers and self-employed wage earners, and paying QPIP premiums during the qualifying period.

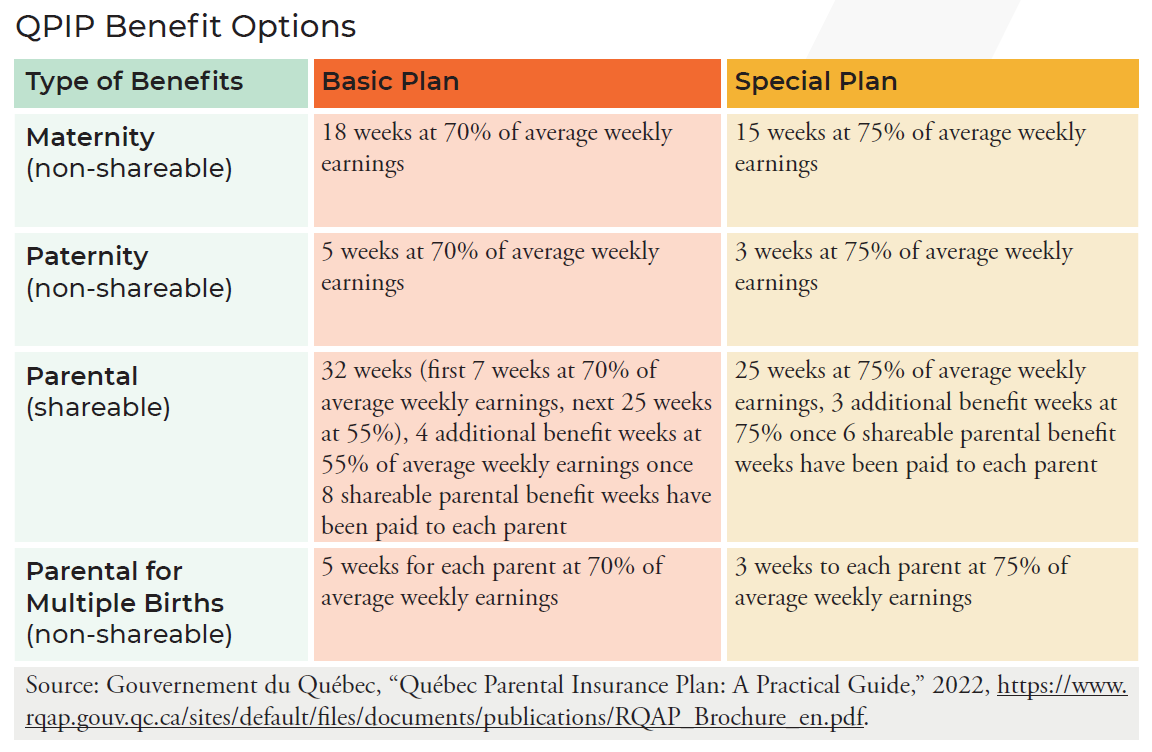

The QPIP offers maternity benefits, paternity benefits for the non-birth parent, sharable parental benefits, and a leave for multiple births. Parents can choose from the basic plan or opt for the special plan. The basic plan allows for up to eighteen weeks of maternity benefits, five weeks for paternity benefits, both at 70 percent of average weekly earnings. The basic plan offers an additional thirty-two weeks of shareable parental benefits. The first seven weeks are paid at 70 percent of earned income, and the final twenty-five weeks at 55 percent. If parents share the benefit with eight weeks of the benefit going to each parent, the family qualifies for an additional four weeks of benefits at 55 percent of earnings.

The special plan offers up to fifteen weeks of maternity benefits, three weeks of paternity benefits, both at 75 percent of average weekly earnings, and an additional twenty-five weeks of shareable parental benefits. The first twenty-five weeks of parental benefits are paid at 75 percent of earned income. If parents share the paid leave with six weeks of benefits going to each parent, the family qualifies for an additional three weeks of benefits at 75 percent of earnings.

In short, the special plan offers fewer weeks but at a higher percentage of earnings.

The QPIP also offers specific basic and special plans for adoptive parents.

The distinguishing features of the QPIP from the federal program are the income-based minimum-earnings qualifier and the more generous benefit payout. Another unique feature is the non-transferable paternity benefit, designed to increase leave uptake among fathers and partners.

Use of Parental Benefits

According to the “2018/2019 Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report,” over 200,000 new parental benefit claims were made during that fiscal year in Canada outside of Quebec. Women accounted for 83.2 percent of the claims made, and men made about 16.8 percent of claims. In terms of the amount of money distributed through claims, women received 90.6 percent of the total amount of parental benefits during fiscal year 2018–19. 3 3 A. Doucet et al., “Canada Country Note,” International Review of Leave Policies and Research, 2021, 172.

Examining the use of benefits by household shows that families utilize almost all the maternity and parental benefits available to them. 4 4 Doucet et al., "Canada Country Note," 172.

The extended benefit option was introduced in 2017. By 2019, nearly a third of mothers applying for benefits intended to use the extended option. 5 5 Doucet et al., “Canada Country Note,” 174.

Data suggest that the portion of fathers claiming benefits is increasing, though there is a significant difference between men in Quebec and the rest of Canada. In 2018, nearly 80 percent of Quebec fathers claimed benefits, compared to 15 percent of fathers in the rest of Canada. Statistics Canada data suggest that fathers rely heavily on vacation time when a new child arrives, with about 42 percent using vacation benefits after the birth of a child. 6 6 Statistics Canada, “The Daily—Study: Family Matters: Parental Leave in Canada,” February 10, 2021, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210210/dq210210a-eng.htm.

Economist Jennifer Robson points to noteworthy differences among workers who use and don’t use parental benefits. She states that between 10 and 20 percent of mothers who work before giving birth do not receive paid benefits, either because they do not work enough hours to be eligible, or their employment type does not qualify. 7 7 J. Robson, “Parental Benefits in Canada: Which Way Forward?,” Institute for Research on Public Policy, March 2017, 19, https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/study-no63.pdf. Robson also notes that socioeconomic factors are evident in who claims benefits. She argues that outside of Quebec, “new families whose children might most benefit from income support—parents who are young, less educated and have lower income, as well as single-earner or single-parent families—are least likely to get public maternity or parental benefits.” 8 8 Robson, "Parental Benefits in Canada," 19. Robson suggests that differences in uptake may be due to stronger labour-force attachment among higher-educated mothers.

Leave and Benefits Policies in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom

Reviewing parental-benefit policies outside of Canada can provide insight into the strengths and weaknesses of Canadian policies. For the purposes of this backgrounder, we provide a brief overview of parental-leave policies, both paid and unpaid, within Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

Australia

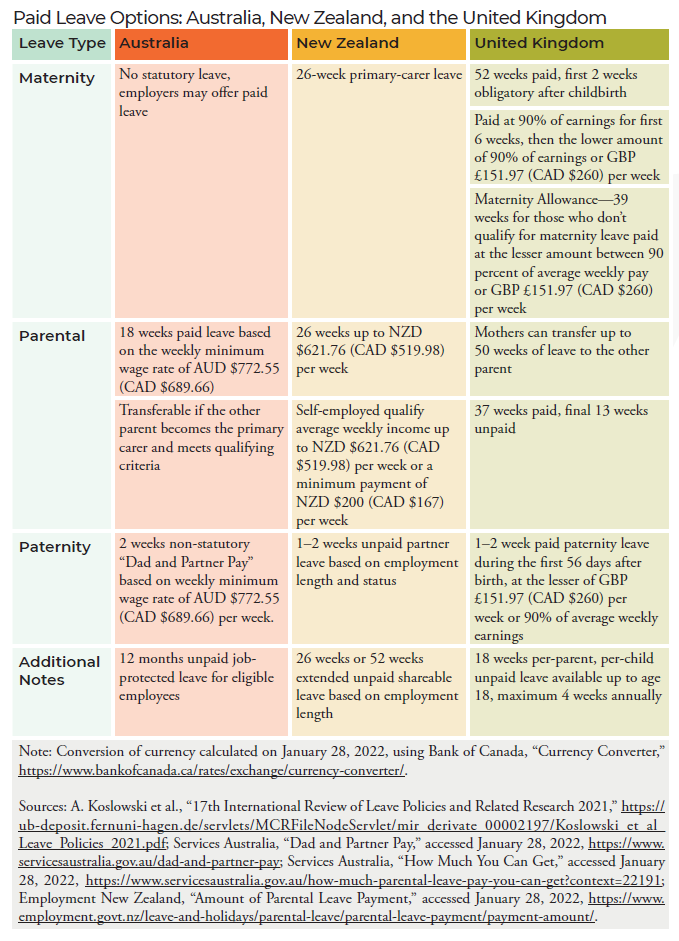

The term “parental leave” encompasses paid and unpaid leave in Australia, where there is no statutory maternity leave or paternity leave. 9 9 Information in this section is from G. Whitehouse, M. Baird, and J. Baxter, “Australia Country Note,” International Review of Leave Policies and Research, 2021; Services Australia, “Dad and Partner Pay,” accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/dad-and-partner-pay; Services Australia, “How Much You Can Get,” accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/how-much-parental-leave-pay-you-can-get?context=22191. Many employers, however, choose to offer paid leave at replacement levels for mothers.

Working parents are each provided with up to twelve months of job-protected unpaid leave, eight weeks of which can overlap between qualifying partners. Parents can begin leave six weeks before the due date but must complete leave within twenty-four months after the birth.

An eighteen-week government-funded paid leave based on the weekly minimum wage rate of AUD $772.55 (CAD $689.66) 10 10 Conversion of currency calculated on January 28, 2022, using Bank of Canada, "Currency Converter," https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/exchange/currency-converter/. is available for qualifying employees and self-employed individuals. To qualify for the benefit, workers must accumulate 330 hours of qualifying work within a ten-month period, with no more than a twelve-week gap between consecutive working days. This ten-month period must be achieved within the thirteen months prior to the due date.

The benefit is based on net minimum wage and can be transferred to the other partner if that partner becomes the primary care-giver and meets the qualifying criteria. The program is funded from general government revenue and is frequently administered through employers, although a minority of recipients receive the benefit directly from the government. Those with an individual income over AUD $150,000 (CAD $133,905) are ineligible for government-paid leave.

Australia does not have a statutory paternity leave as such, but offers up to a two-week “Dad and Partner Pay” based on the weekly national minimum wage. This can be combined with leave transferred from the eighteen-week leave noted above, but transferred-leave payment and Dad and Partner Pay cannot be received concurrently. Some employers choose to offer a paid paternity leave.

Australia provides a special maternity leave for pregnancy-related illness and pregnancy loss within twenty-eight weeks of the due date. Recipients of the special maternity leave also qualify for the twelve-month unpaid leave. In the event of a stillbirth or death of a child within the first twenty-four months after birth, an employee can take up to twelve months of unpaid parental leave.

Parents who adopt can claim unpaid parental leave, paid parental leave, and Dad and Partner Pay when adopting a child under sixteen years old. Parents who adopt a child who lives with them prior to the adoption, such as adopting a stepchild, may not be eligible for parental leave pay.

Australian parents of children who are school aged or younger have the statutory right to request flexible work arrangements.

New Zealand

New Zealand offers a twenty-six-week paid primary-carer leave. 11 11 Information for this section is from A. Masselot and S. Morrissey, “New Zealand Country Note,” International Review of Leave Policies and Research, 2021; Employment New Zealand, “Amount of Parental Leave Payment," accessed January 28, 2022, https://www.employment.govt.nz/leave-and-holidays/parental-leave/parental-leave-payment/payment-amount/. The leave provides 100 percent of earnings up to NZD $621.76 (CAD $519.98) a week before tax. The leave can begin up to six weeks before the due date but must be taken in one continuous block. Self-employed parents may also receive 100 percent of earnings up to NZD $621.76 (CAD $519.98) per week. Self-employed parents who make less than minimum wage working a minimum of ten hours a week, or who make a loss, can receive a minimum payment of NZD $200 (CAD $167) per week. The leave is funded through general tax revenue. Employees and the self-employed are eligible if they have worked an average minimum of ten hours per week for any twenty-six weeks in the fifty-two-week period prior to the due date.

When the health of the mother or baby is a concern, leave can be taken before the six-week window prior to the due date, in which case the mother retains up to twenty weeks leave after the due date. In addition to paid leave, mothers are entitled to ten unpaid days for pregnancy-related reasons, such as appointments and antenatal classes.

New Zealand provides “keeping in touch” days in which mothers can work up to sixty-four hours while receiving paid benefits, beginning twenty-eight days post-birth. Additional leave and “keep in touch” days are available when the birth is pre-term. Mothers can transfer a portion of their leave to another carer.

Partners may be eligible for one or two weeks of unpaid leave, to be taken in the period between twenty-one days before the due date and twenty-one days post-birth. To qualify, workers must have worked an average minimum of ten hours a week with the same employer for at least six months immediately before the due date in order to access one week leave, and at least twelve months to access two weeks of leave.

Extended leave is an unpaid leave covering up to fifty-two weeks in the twelve months following the birth. Extended leave can be shared but has work requirements. A primary carer or partner must have worked an average minimum of ten hours a week for six months immediately prior to the due date with the same employer to receive twenty-six weeks’ leave, or twelve months to receive fifty-two weeks. Partners can take leave consecutively or at the same time.

Parents who adopt a child are eligible for the same benefits as birth-parents. Couples who jointly adopt a child under age six can select which parent receives payment.

Employees have a statutory right to request flexible hours, days, or place of work, and to request breaks for breastfeeding.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom offers maternity leave, shared-parenting leave, and paternity leave. 12 12 Information for this section is from J. Atkinson, M. O’Brien, and A. Kosloski, “United Kingdom Country Note,” International Review of Leave Policies and Research, 2021.

Maternity leave is a paid fifty-two-week leave that can be taken eleven weeks prior to the due date. The first two weeks of leave after childbirth are obligatory. Women with employee status and who have worked for their employer continuously for twenty-six weeks up to the fifteenth week before the week the baby is due are eligible for maternity leave if they earned a minimum of GBP £120 (CAD $205) per week. The first six weeks are paid at 90 percent of average earnings with no upper limit, and the following thirty-three weeks are paid at the lesser of 90 percent of earnings or GBP £151.97 (CAD $260) per week. Those with worker status, self-employed, or on contract do not qualify but may be eligible for a Maternity Allowance (see below). Maternity-leave payment is administered through the employer. Medium and large employers are compensated at 92 percent of the benefit, and small employers at 103 percent of the benefit. In addition to leave, ten “keep in touch with work days” are available that do not affect benefits. Some employers provide additional provisions.

Mothers can transfer up to fifty weeks of their leave to their partners, but must commit to a return-to-work date. Shared leave can be taken in one-week blocks, and can be alternated between parents. Both parents must meet the qualifying requirements in order to share paid leave. The leave is paid at the lesser of 90 percent of the wage or GBP £151.97 (CAD $260) a week for thirty-seven weeks. The final thirteen weeks are unpaid. Minimum work requirements are required of both partners to share the leave.

Maternity Allowance provides thirty-nine weeks’ pay at the lesser amount between 90 percent of average weekly pay or GBP £151.97 (CAD $260) per week. This benefit is aimed at those who do not qualify for maternity leave because they have changed jobs, are self-employed, or recently left work. To qualify, women must have worked twenty-six weeks in the previous sixty-six weeks prior to the week of the due date, earning a minimum of GBP £30 (CAD $51) per week in at least thirteen weeks.

One- or two-week paternity leave is offered within the first fifty-six days after the birth at the lesser of 90 percent of the average weekly wage or GBP £151.97 (CAD $260). Funds are administered through the employer much like maternity leave. To qualify, the partner must early a minimum of GBP £120 (CAD $205) per week, provide fifteen weeks’ notice, and have worked continuously for the same employer for twenty-six weeks prior to the fifteenth week before the due date.

An eligible individual or one eligible parent in an adopting couple can claim fifty-two weeks of adoption leave. The benefit is paid at 90 percent of earnings for six weeks with no upper limit. The following thirty-three weeks are paid at the lower amount of either 90 percent of average gross weekly earnings or GBP £151.97 (CAD $260). An additional thirteen weeks of unpaid leave are available. The non-leave-taking parent can claim the paid paternity leave.

In addition to these benefits, there is an eighteen-week per-parent, per-child unpaid leave that can be drawn on until the child is eighteen years old. No more than four weeks per year can be claimed, unless otherwise permitted by the employer. 13 13 The earnings thresholds and standard rates for statutory maternity pay, maternity allowance, paternity pay, shared parental pay, and adoption pay will slightly increase in April 2022 to 2023. For more information, see Government of the United Kingdom, "Proposed Benefit and Pension Rates 2022 to 2023," January 11, 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/benefit-and-pension-rates-2022-to-2023/proposed-benefit-and-pension-rates-2022-to-2023.

Exploring Reform

As stated above, the purpose of this backgrounder is to provide context for further conversations on reforms to the federal parental-benefit system. As acknowledged earlier, there are various motivations and interests for supporting parental benefit policies, and these perspectives can exist in tension with each other. Below we offer questions for further discussion.

Access

Evidence suggests that the current structure of benefits in Canada inhibits equitable access. For example, younger workers have more difficulty accessing parental benefits, especially if they work part time. Many parents who reduce their work hours after having a child are at a disadvantage in accumulating enough qualifying hours to access benefits between children. 14 14 Robson, “Parental Benefits in Canada,” 4. As benefits are based on a percentage of income, lower-income workers receive a relatively small benefit amount at precisely the time when household expenditures increase.

How could benefits be made more accessible, particularly for those who would be helped most from a robust payment? Does continuing to administer the program through the Employment Insurance system still make the most sense?

Benefit Structure

The perennial question with parental benefits is whether they provide sufficient funds and length of leave for families. Should Canada adopt substantially longer benefit periods? Additionally, should the federal benefit structure focus on increasing participation of fathers and non-birth partners, as is the case in Quebec? Would this make a substantial difference in the amount of time off that fathers take after the birth of a child? Should the structure provide more flexibility to allow parents to stay connected with the workplace while on benefits without seeing a clawback? Finally, should the Family Supplement threshold, unchanged since 1997, be increased? If so, how should the increase be determined?

Employers

Parental benefit policies have implications for employers who must manage absences but also profit from worker retention that benefits tend to facilitate. How do potential reforms affect employers, and should they have a more hands-on role in the system? Should the state incentivize greater flexibility in the workplace?

Families

There are numerous motivations and policy options when considering reforming benefit policies. What are the elements of parental benefits that are most important to Canadian families? How can their needs and desires inform policy-making?