Key Points

- In an attempt to better understand fertility ideals and intentions, Cardus surveyed 2,700 Canadian women and found that almost half of those who are near the end of their reproductive years report that they desire more children that they will likely not have.

- This report examines the extent to which Canadian women’s concerns about climate change or overpopulation affect their fertility choices.

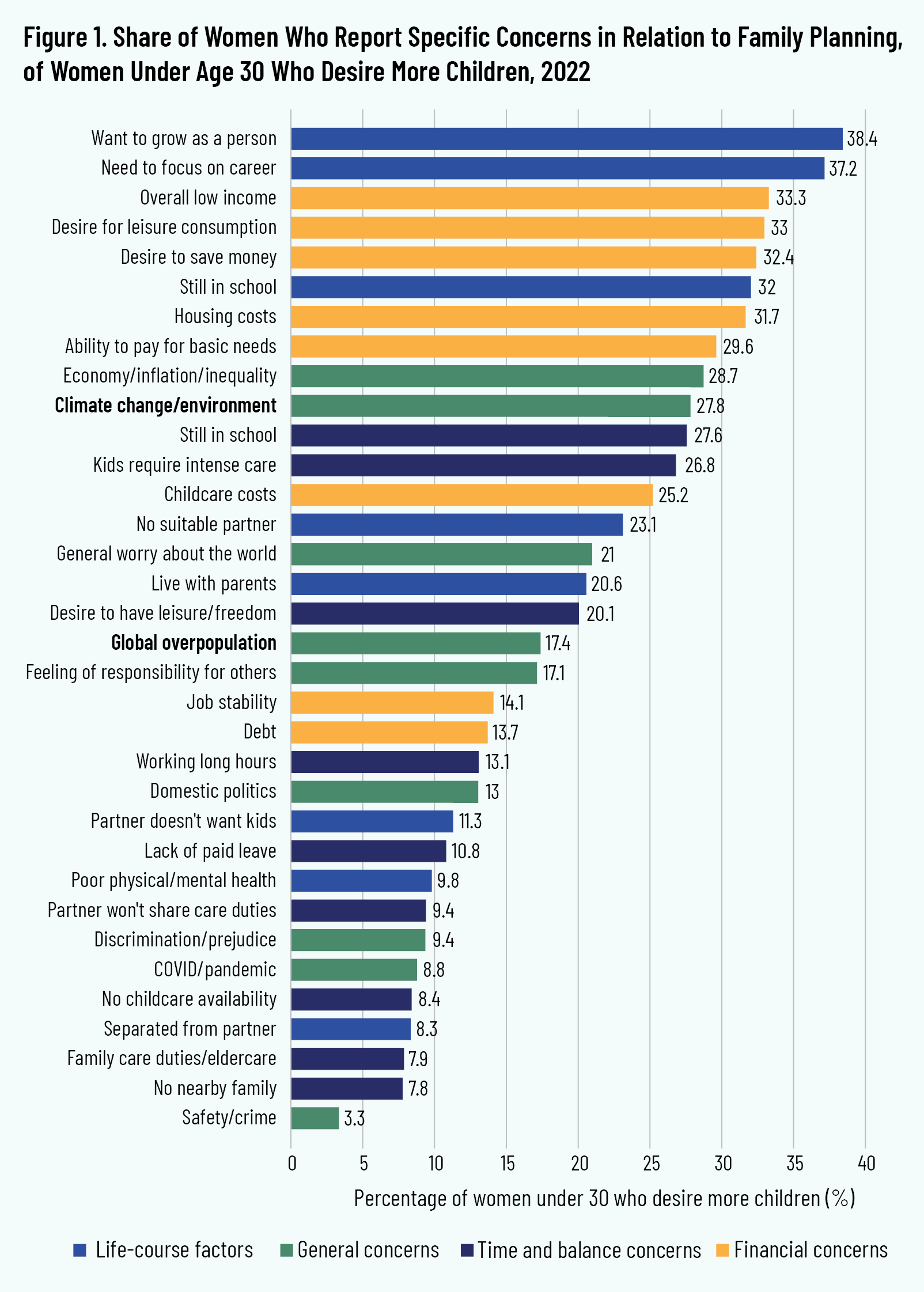

- Twenty-eight percent of women under age thirty who desired to have more children than they currently had cited climate change as a concern that influences their family-planning decisions, making this concern the tenth-most prevalent of all concerns surveyed.

- Seventeen percent of women under age thirty who desired to have more children than they currently had cited overpopulation as a concern that influences their family-planning decisions.

- The top five family-planning concerns were, in order: “Want to grow as a person,” “Need to focus on career,” “Overall low income,” “Desire for leisure consumption,” and “Desire to save money.”

- Women who expressed worry about climate change also generally had lower fertility ideals, a smaller reduction in fertility intentions, and no significant difference in actual fertility behaviours compared to those who did not have this worry. This suggests that climate-change worries are not a major determinant of Canadian fertility behaviours.

- To the extent that climate-change worry correlates with fertility attitudes and behaviours, it may operate more as a rationalization for postponed fertility than as motivating permanently lower fertility. Concern about climate change is part of a larger set of cultural or political beliefs, and these broader beliefs are actually a stronger predictor of fertility outcomes.

- Both women who are worried about climate change and women who are not worried about it are likely to have fewer children than they desire or intend. Even women who report that climate-change worry influences their childbearing plans desire more children than they are actually likely to have.

- Policymakers should examine the broader package of impediments to achieving the fertility goals that women say they want, and in particular explore how broader anxieties about the difficulty of childrearing can be allayed. Highly specific worries (such as climate change) are not the core underlying factor driving low fertility.

Introduction

Climate change is one of the most contentious and widely discussed issues of our day. Discussions about this issue touch on many aspects of life, such as transportation, housing, fashion, food, and even childbearing. Media coverage creates a picture of young people struggling with the idea of having children due to worry about climate change. 1 1 As one example, see B. Wray, “Deciding to Have a Baby Amid the Climate Crisis: Whatever You’re Feeling, You’re Not Alone,” CBC News, November 24, 2022, https://www.cbc.ca/documentaries/deciding-to-have-a-baby-amid-the-climate-crisis-whatever-you-re-feeling-you-re-not-alone-1.6662734. A related but different concern, particularly when examining fertility, is overpopulation.

This report does not study how having children may contribute to these planetary pressures, nor how these may affect the lives of children born today. Rather, this report examines the extent to which Canadian women’s concerns about climate change or overpopulation affect their fertility choices, in terms of both their ideals and their actual intentions.

This study finds that climate-change and overpopulation worries are associated with lower ideal family sizes for Canadian women. However, this effect is illusory: climate-change or overpopulation worries have much smaller negative associations with intended family size, they have no significant effect on actual fertility behaviour, and their effect on ideal family size is mostly a product of the correlation between climate-change worry and political affiliation.

Just as a prior Cardus study showed that religiosity predicts fertility preferences and outcomes, so does political affiliation: women who voted for left-leaning parties tended to want fewer children. In general, this report finds that climate-change worry probably does not influence fertility very much. Rather, this concern is symptomatic of overall more generalized worry or anxiety in some groups of Canadian women.

Understanding why some groups of women are systematically more likely to report almost any given kind of worry or concern is important for understanding low fertility in Canada, since this high level of general worry is far more strongly associated with low fertility than any specific worry is.

Moreover, this study finds that fertility gaps (that is, older women who have fewer children than they say they would like) exist regardless of climate-change worry: both climate-change-worried women and other women who do not share this worry report appreciable shortfalls in their actual fertility versus their fertility ideals or intentions.

Methodology

In 2022, Cardus with the Angus Reid Institute surveyed 2,700 women in Canada aged eighteen to forty-four about family and fertility. The sample had three stratified elements: 1,000 native-born women surveyed in English, 1,000 native-born women surveyed in French, and 700 foreign-born women surveyed in French or English. The sample was stratified in this way in order to ensure good coverage of Canada’s diverse society. Respondents were re-weighted to ensure that they were representative of Canadian women on the whole by age, language, income, province, sexual orientation, and household structure (marital status and children). Incidence rates and completion times for native-born Anglophone and Francophone respondents were similar and within normal ranges; incidence rates for foreign-born respondents were low, indicating some difficulty recruiting these respondents.

The first Cardus report that was based on these data, “She’s (Not) Having a Baby,” explored family and fertility preferences. The second report, “Religion and Fertility in Canada,” explored correlations between fertility and religious affiliation. 2 2 L. Stone, “She’s (Not) Having a Baby: Why Half of Canadian Women Are Falling Short of Their Fertility Desires,” Cardus, 2023, https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/reports/she-s-not-having-a-baby/; L. Stone, “Religion and Fertility in Canada,” Cardus, 2023, https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/reports/religion-and-fertility-in-canada.

Each paper examines women’s fertility ideals versus intentions. In these reports, “ideals” or “desires” are used to refer to the number of children that women say they would ideally like to have (or to have had, if they are at the end of their reproductive years), and “intentions” to refer to the number of children that women say they actually expect to have (reflecting practical realities). It is exceedingly rare in contexts where women have equality before the law for women to “intend” children that they do not “desire.” But it is very common for women to “desire” children that they do not “intend,” because they think those children are unobtainable, for various reasons. Thus, intentions represent a compromise between desires and reality and are almost always lower than ideals or desires.

This third report examines the manner in which fertility ideals and intentions are affected by concerns about climate change or overpopulation. While most of this report analyzes all adult women under age forty-five as one group, it devotes some additional attention to women under age thirty who report fertility ideals in excess of their current family size. This subsample is of particular interest because such women are mid-course in their reproductive lives, and their childbearing intentions could conceivably be directly affected by concern about climate change, overpopulation, or some other concern.

Survey respondents were offered a structured list of thirty-four possible concerns that might affect their childbearing plans, and they could also write in any concerns not on the list. They were presented first with a set of broadly worded concerns relating to finances, time and balance, stage of life, and general social worries. If a respondent selected any of these, she was then offered a more detailed list of options. Two of these were “climate change/environment” and “global overpopulation.” This report refers to these as “climate change” and “overpopulation.” In cases where write-in responses were very similar to an unselected response option, that option was recoded as selected.

It is important to note that the survey did not ask women about their general worry about climate change or overpopulation; rather, it asked if worry about these issues influenced their childbearing plans. Thus, the survey does not measure the general prevalence of worry about climate change or overpopulation; instead, it measures the prevalence of these worries insofar as women perceive them to influence their childbearing plans. Although this report uses the shorthand “climate-change worry” or “overpopulation worry,” it analyzes only that subset of worries that women perceive to be linked to their childbearing plans. It is entirely possible that women might worry about climate change very much without it factoring into their childbearing plans.

Climate-Change and Overpopulation Worries

Figure 1 shows the percentage of women under age thirty who desire (more) children who selected each of the thirty-four concerns. Twenty-eight percent cited climate change, making it the tenth-most-prevalent concern, and 17 percent cited overpopulation, making it the eighteenth-most-prevalent concern.

That this core demographic of women at a key stage to make family-planning decisions does not report climate change or overpopulation as top-priority concerns affecting their family planning suggests that these factors are probably not major drivers of low birth rates in Canada.

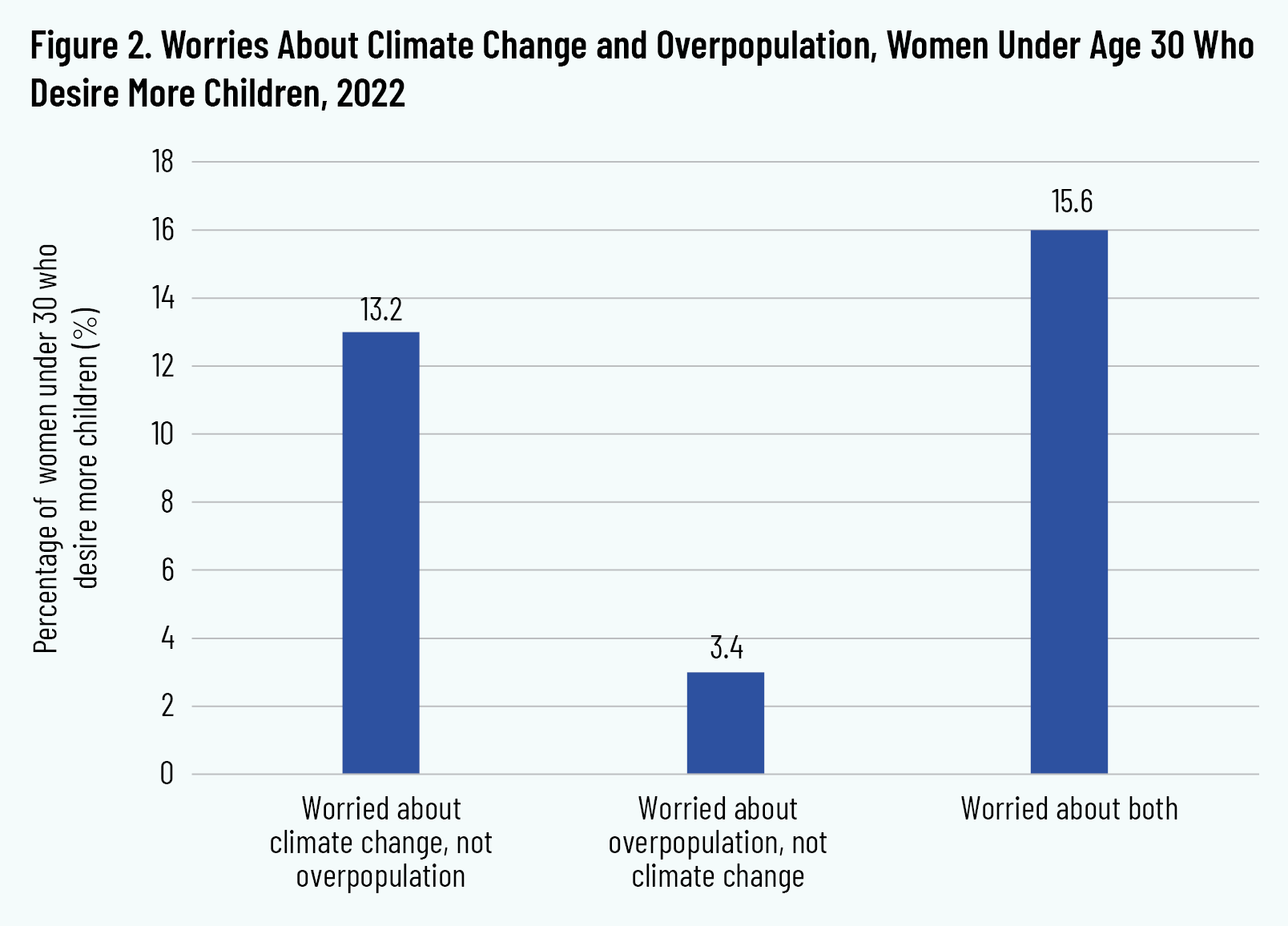

These data also suggest that concern about climate change and concern about overpopulation are not two ways of expressing one same concern. As figure 2 shows, 13 percent of the cohort selected climate change as a factor they considered when making childbearing decisions, but not overpopulation. Another 3 percent selected overpopulation as a factor, but not climate change. And a final 16 percent selected both factors.

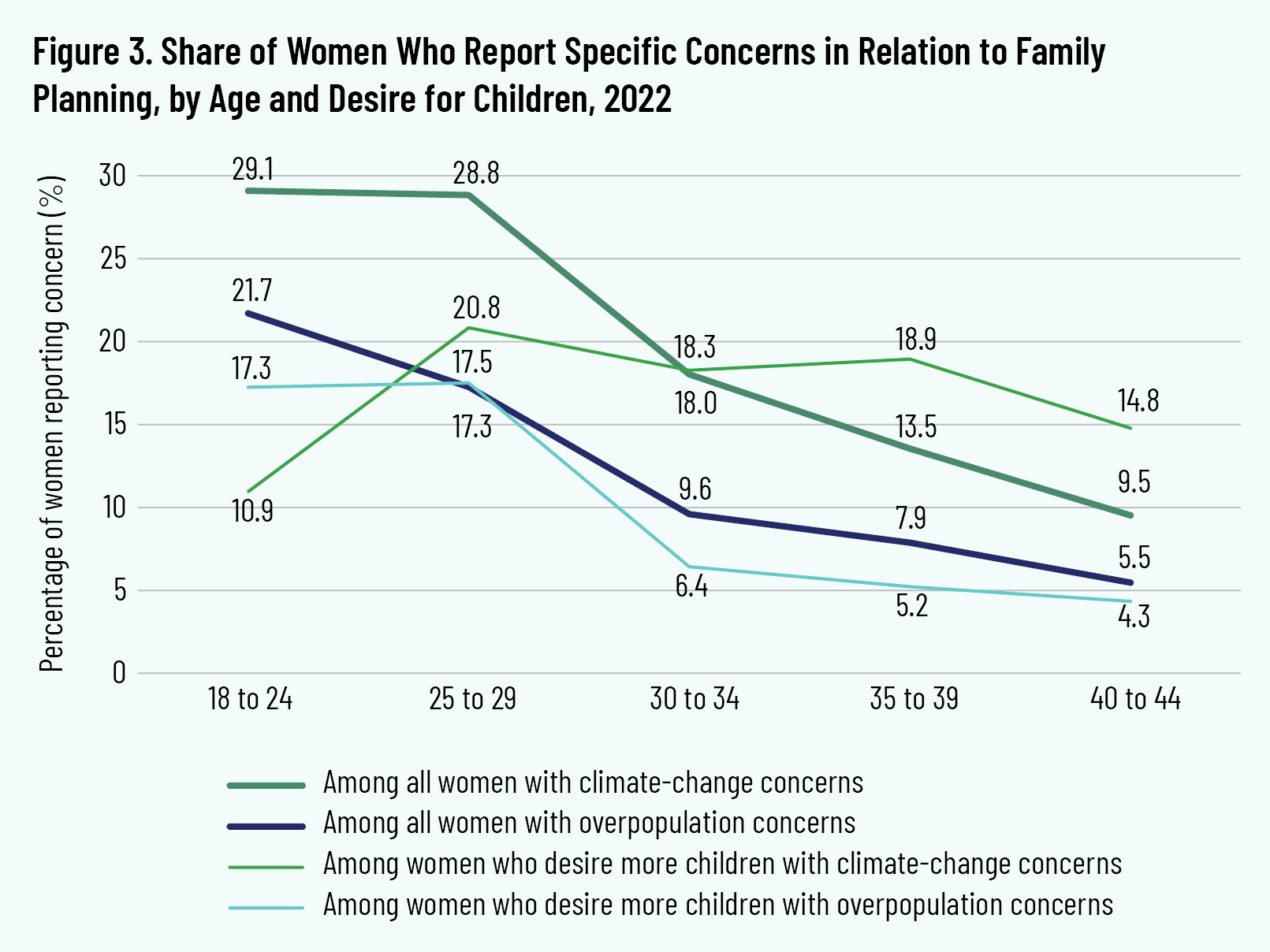

Concern about climate change and concern about overpopulation are much more common among younger women, as shown in figure 3. Among all women under age thirty, almost 30 percent report that climate-change worry influences their childbearing plans, versus under 10 percent for women in their forties. Overpopulation worry shows a similar trend, at about 22 percent for those under the age of twenty-five, versus 5 percent for women in their forties.

Of women who would ideally like to have more children, concern about overpopulation still tends to decline with age—but concern about climate change does not. Among women who would ideally like to have more children, climate-change worry affects the childbearing plans of about 10–20 percent of women across all age categories. That climate-change worry is a more prevalent family-planning influence among women in general than among women who ideally would like more children may suggest that climate-change worry is more strongly associated with ideals than with actual intentions. Additional evidence for this possibility is presented below.

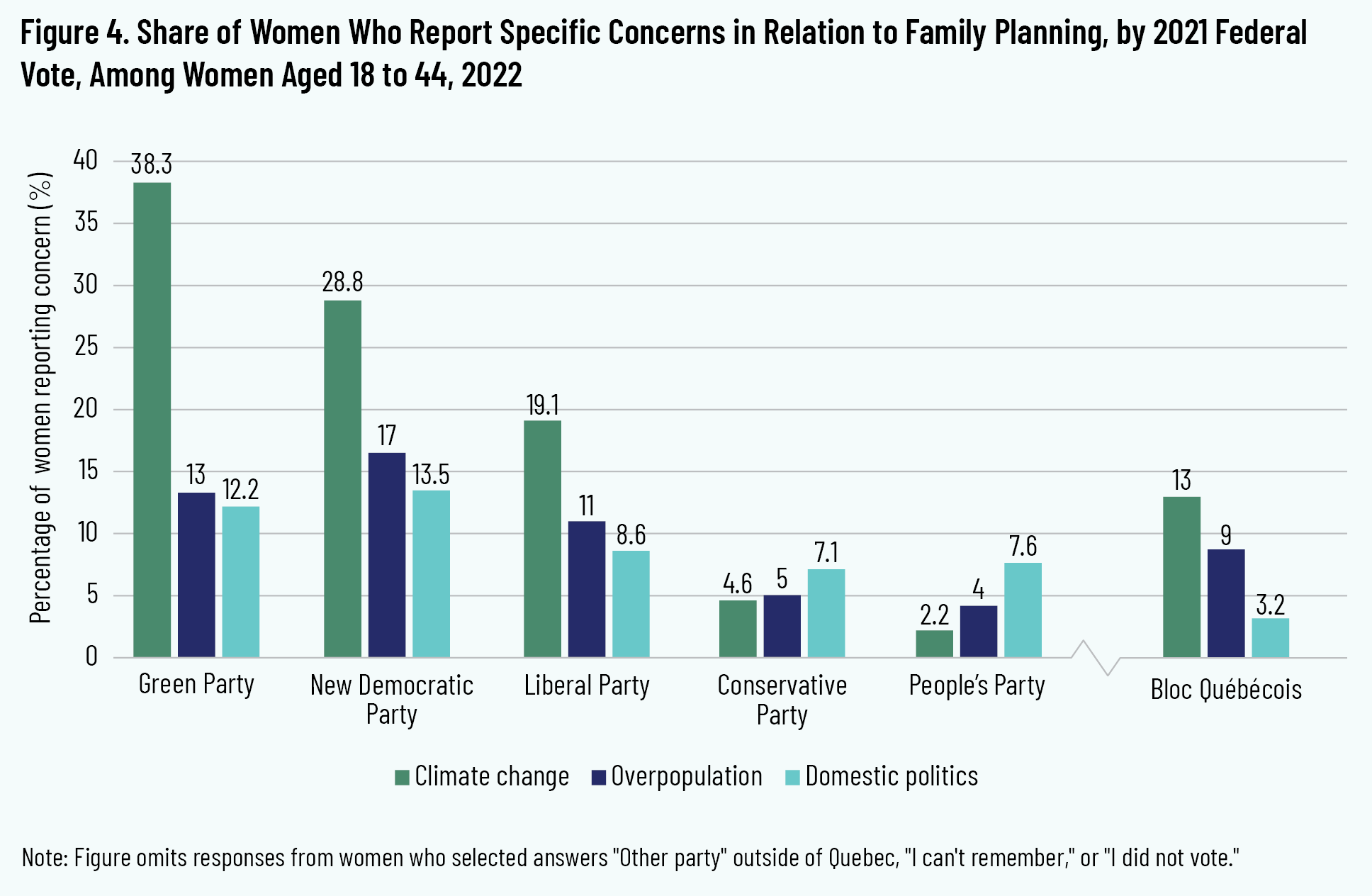

Age is not the only factor that increases the likelihood of having climate-change worry—political affiliation does too. Figure 4 shows the share of women who selected climate change or overpopulation as concerns affecting their childbearing plans, by their self-reported voting behaviour in the most recent federal election.

Among women who voted for parties that are commonly perceived as left-leaning on the political spectrum, climate-change worry is much more common. Of women who voted for the Green Party, 38 percent cited climate-change worry as a factor influencing their childbearing plans, as did about 29 percent of those who voted NDP and 19 percent of those who voted Liberal. About 5 percent of those who voted Conservative and 2 percent of those who voted for the People’s Party cited this worry, and 13 percent of those who voted for the Bloc Québécois did so. 3 3 Due to an oversight, “Bloc Québécois” was not offered as a response option in the survey. For women residing in Quebec, the response “Other” was interpreted as a vote for the Bloc Québécois. (This party does not field candidates outside of Quebec). “Other” response selection was far more common in Quebec than in any other province, and the “Other” share of the sample in Quebec closely approximates the actual vote share that the Bloc received in Quebec in the last federal election.

Climate-change worry, then, varies significantly among women based on their political affiliation. There appears to be less divergence among women who reported overpopulation worry, though overpopulation worry was more common among women who reported voting for the more left-leaning parties (13 percent for the Green Party, 17 percent for the NDP, 11 percent for the Liberal Party; versus 5 percent for the Conservative Party and 4 percent for the People’s Party; Bloc Québécois is at 9 percent).

In general, women who reported left-leaning voting behaviour are likelier to report most worries and concerns on the list as affecting their childbearing decisions, similar to the dynamic that was observed for less-religious women in the earlier Cardus report. For this reason, worry prevalence was also modeled with an important control variable: the total number of worries or concerns that the respondent selected. For all subsequent figures after figure 4, results are presented from a model that controls for the fact that respondents who reported any worry (such as climate change) were likelier to report any other worry, by including a variable equal to the summed number of worries or concerns reported. This is because reporting any individual worry increases the likelihood that a respondent may have a generally high level of worry or concern. This report refers to this dynamic as “worry-proneness.”

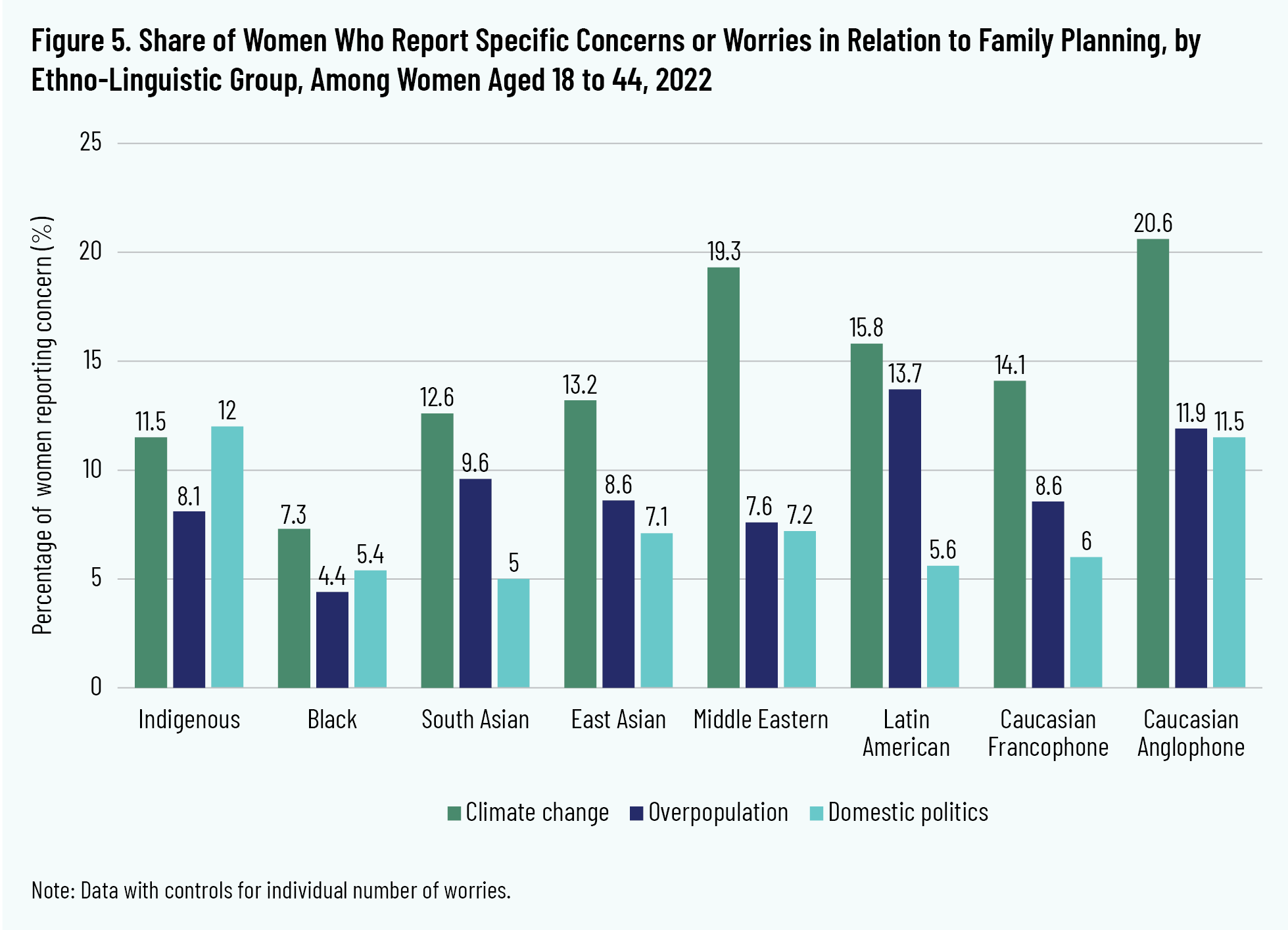

This report also examines how worries about climate change and overpopulation vary across Canada’s diverse ethnic and linguistic groups. For this study, respondents were grouped into eight categories: two language groups of Caucasians (Anglophone and Francophone) and six groups of non-Caucasian women (regardless of language). Figure 5 shows that across every group except Indigenous women, once worry-proneness is controlled for, concern about climate change is more prevalent than concern about overpopulation. Caucasian Anglophone women reported the highest level of concern about climate change, followed by women of Middle Eastern descent. Black and Indigenous women, and women of South Asian descent, reported the lowest levels of climate-change concern.

When it comes to concern about overpopulation, a higher percentage of women of Latin American descent and Caucasian Anglophone women reported this concern, followed by women of South Asian descent, compared to the other groups. Overall, Black and Indigenous women and women of Middle Eastern descent reported the lowest concern about overpopulation.

Many women are worried about climate change and overpopulation and about a quarter of women report that climate-change worry influences their family plans. The women most likely to be concerned about climate change and overpopulation tend to be under the age of thirty, voted for a left-leaning party in the 2021 federal election, are Caucasian, and are Anglophone. On the other hand, the women who are the least likely to report worries about climate change and overpopulation tend to be older, members of ethnolinguistic minorities, and voted for a right-leaning party in the 2021 federal election.

Thus, the moderate prevalence of climate-change worry masks considerable variation. In some subgroups of women (such as young women who voted for a left-leaning political party) large shares of women report that climate-change worry influences their childbearing plans. But in other subgroups, such as Conservative voters or Black and Indigenous women, very few women report climate-change worry as influencing their childbearing plans.

Fertility Preferences and Climate-Change Worry

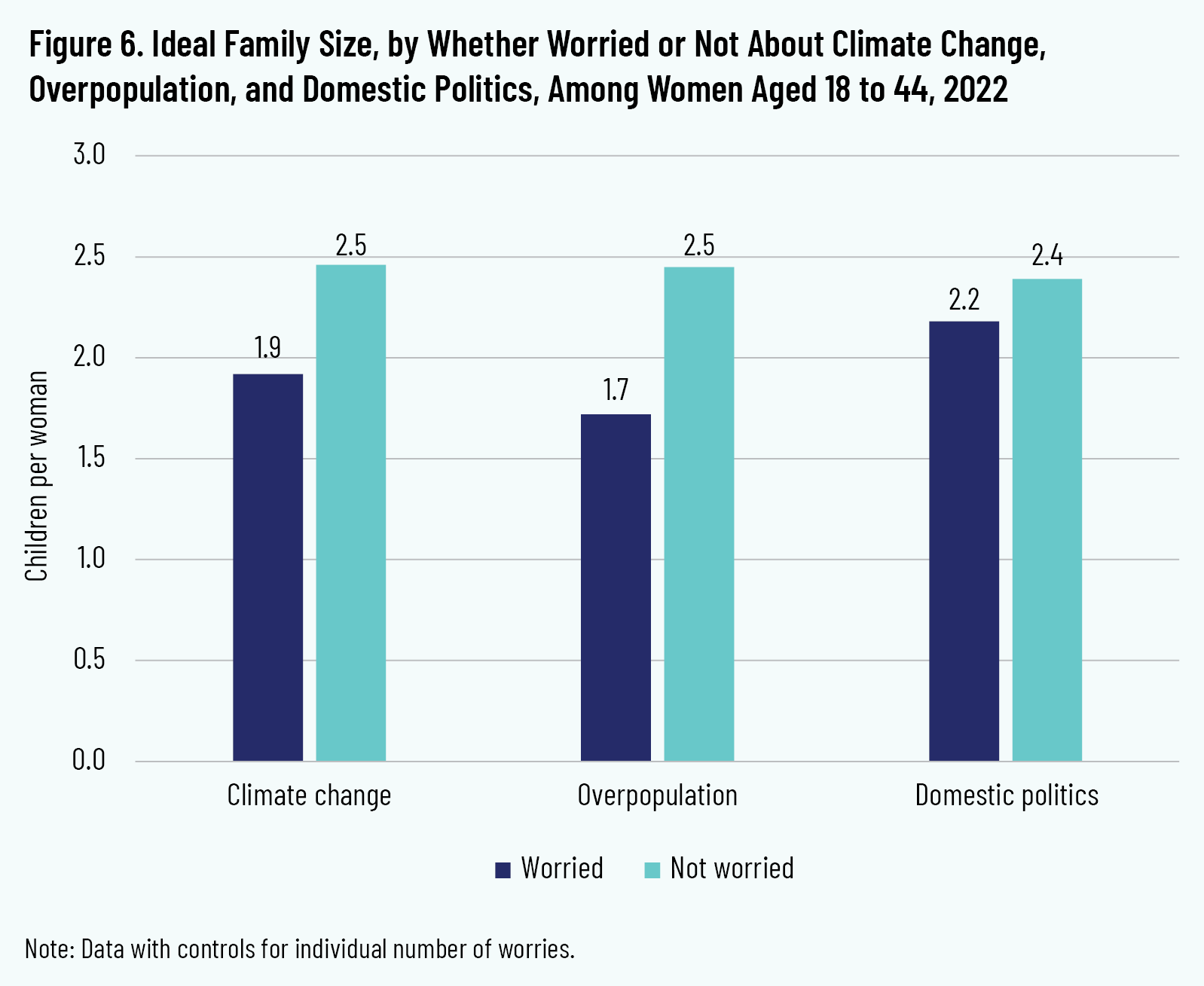

Having established the general prevalence of climate-change worry as it relates to childbearing decisions, this study now turns to how women who worry about climate change or overpopulation differ from women who do not share these concerns in relation to their fertility preferences. Figure 6 shows the average ideal family size reported by women who do or do not report each given worry. Women’s overall number of other worries was controlled for as described earlier, to ensure that the differing family-size ideals between those who are worried about climate change or overpopulation and those who are not worried are not driven by general differences in worry-proneness.

Women worried about climate change reported an ideal family size of about 1.9 children, versus 2.5 for women not worried about climate change, for a gap of about 0.6 children. Overpopulation worry was even more decisive, though: women who had concerns about overpopulation had an ideal of just 1.7 children per woman, versus 2.5 for women who did not share that concern.

Thus, while climate change is associated with lower fertility ideals, overpopulation worry was associated with fertility ideals that are even lower. As noted above, many women worried about climate change are not worried about overpopulation, and some women worried about overpopulation are not worried about climate change. This intersection is explored in further detail below.

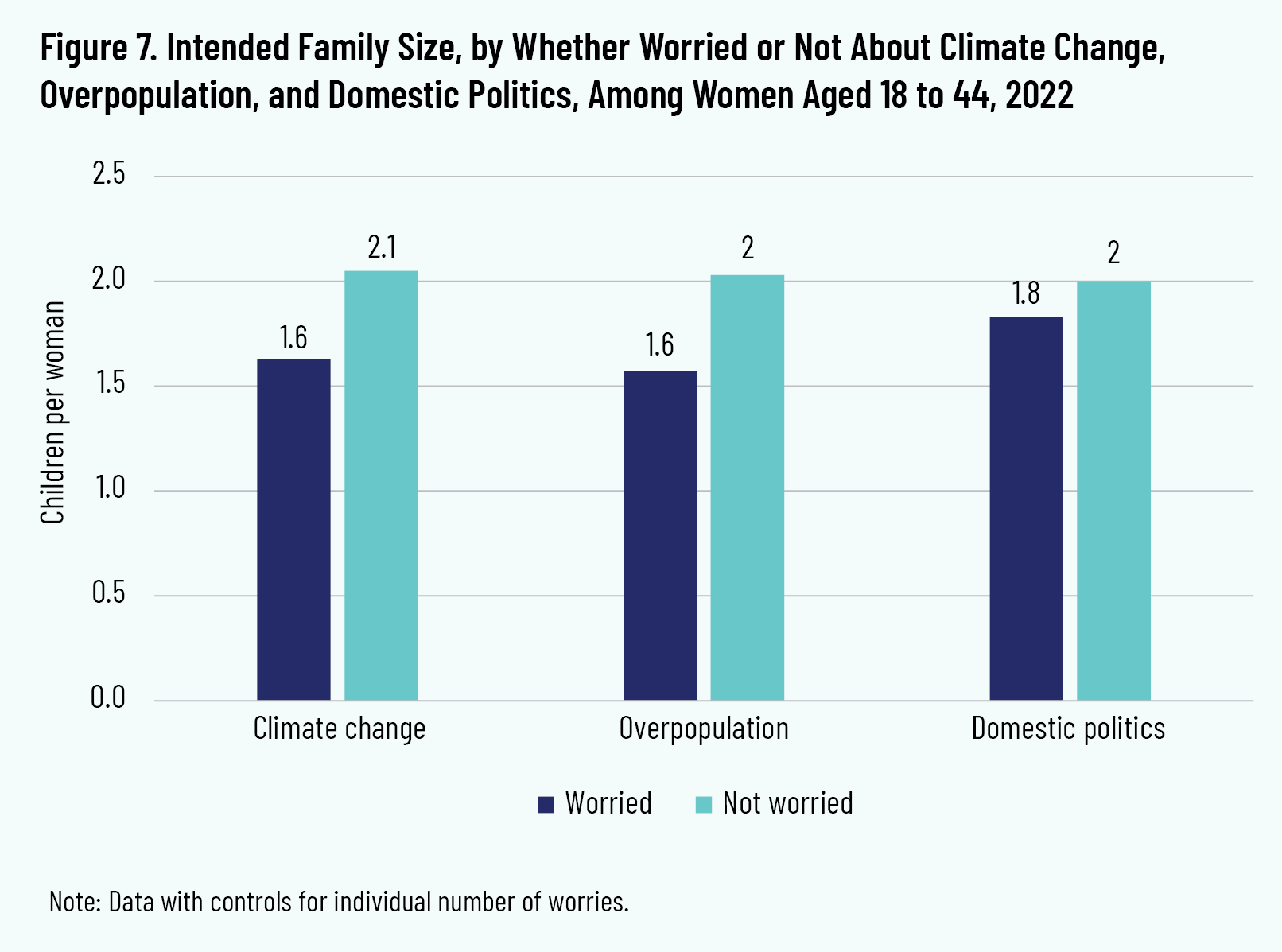

Fertility ideals are a good measure of general fertility values and attitudes and the kinds of lives women might like to have, but may not always be predictive of what women realistically expect for their own lives. For that, fertility intentions must be turned to, shown in figure 7. Women who said that climate-change concerns influence their childbearing plans reported that they intended about 1.6 children on average, similar to women who were concerned about overpopulation.

On the other hand, women who did not share these specific concerns reported intending two children, for all factors under consideration. An important difference emerges when figure 6 and figure 7 are compared. Women worried about climate change had an ideal that was 0.6 children below other women, but intentions only 0.5 lower; for overpopulation-worried women, the ideals gap was 0.8 in figure 6, but the intentions gap was just 0.4 in figure 7. In other words, as noted earlier, climate-change and overpopulation worries have more negative associations with ideals and broad value sets than with more concrete intentions.

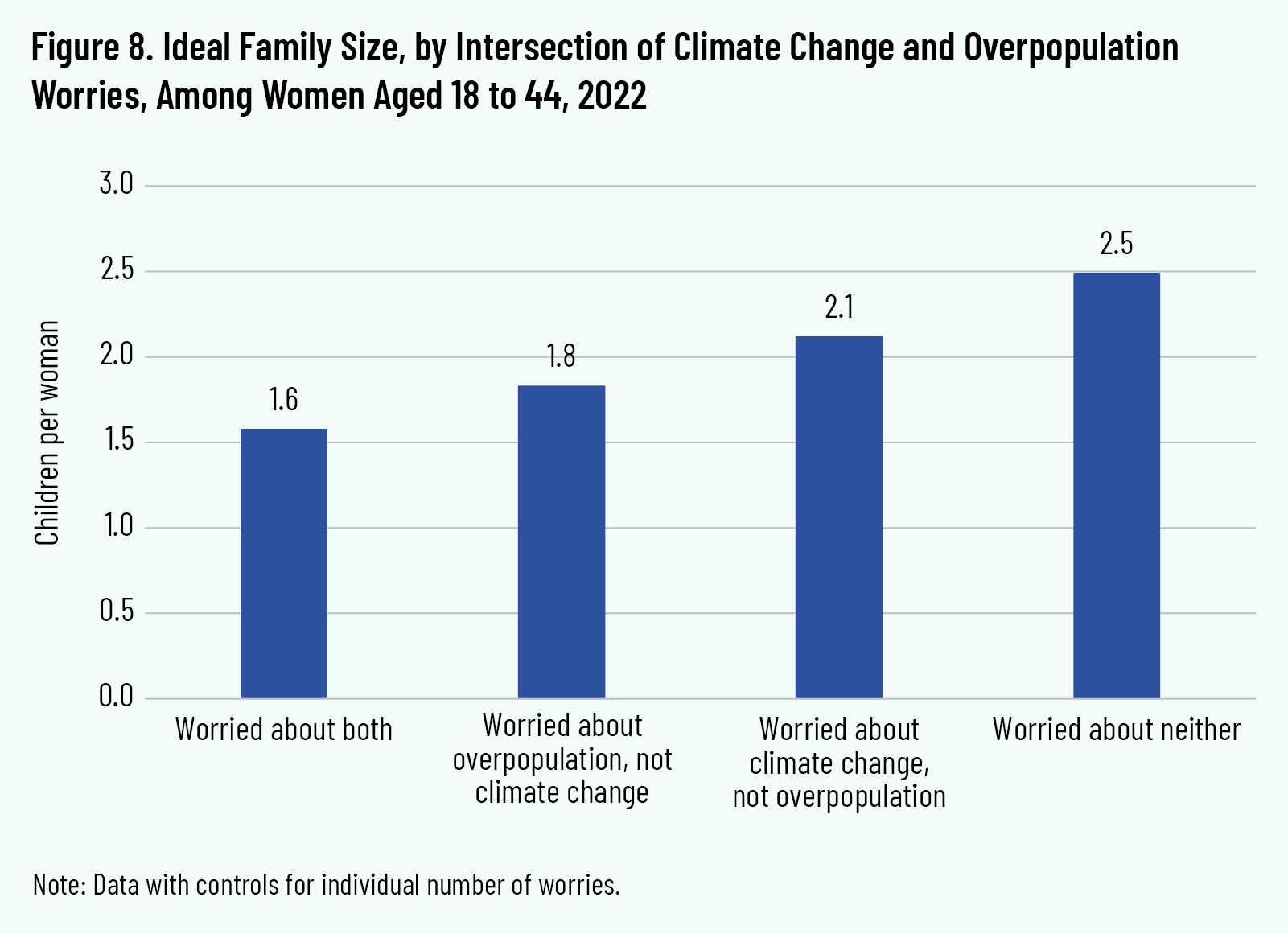

Next, the possible joint influence of climate change and overpopulation worries on women’s ideal family size were assessed, as shown in figure 8. There is a large difference between women who report concerns about neither climate change nor overpopulation (ideal family size of 2.5) and women who report worry about both (ideal family size of 1.6). For women who have concerns about climate change but not overpopulation, the ideal family size is 2.1. But for women reporting worry about overpopulation but not climate change, the ideal family size is 1.8 children.

Climate-change worry was associated with a 0.2 to 0.4 decline in ideal number of children within the group of women who express overpopulation worry. Within the group of women who express climate-change worry, overpopulation worry was associated with a 0.5 to 0.7 child decline.

In other words, overpopulation worry is approximately twice as influential on fertility ideals as climate-change worry is. These results suggest that overpopulation worry apart from climate-change worry does exist and does drive meaningfully smaller family-sizes preferences. Some women worry about overpopulation for reasons not related to climate change, and this worry has a profound impact.

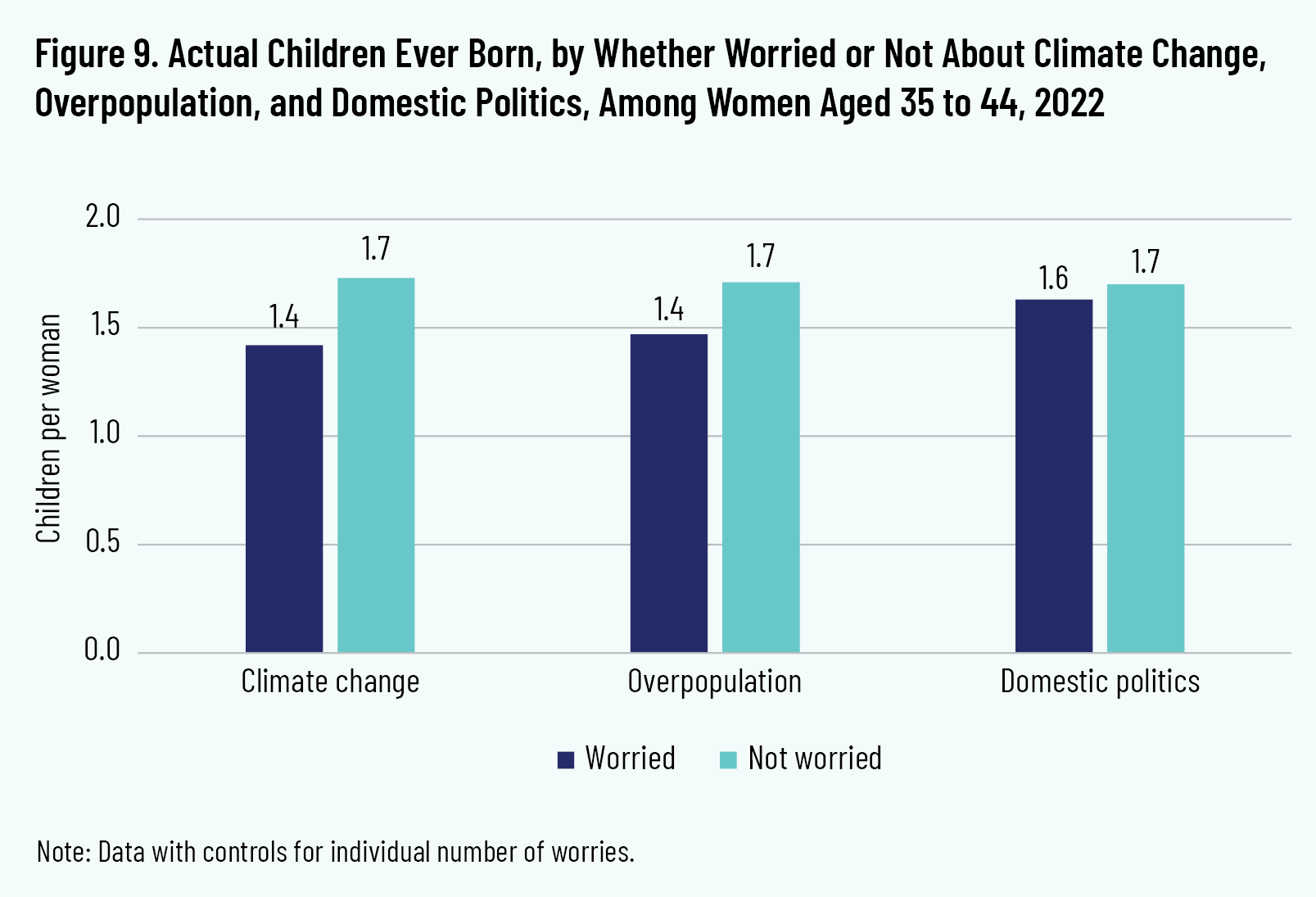

Finally, as shown in figure 9, within the subset of women aged thirty-five to forty-four, whether they report climate-change and overpopulation worries is associated with even smaller differences in childbearing history.

Climate-change and overpopulation worries are associated with 0.2 to 0.3 fewer children ever born among women aged thirty-five to forty-four. Given the sample size of women in this age range, however, these differences are not statistically significant. In other words, no statistically meaningful association is identified between climate-change worry, overpopulation worry, and actual childbearing by ages thirty-five to forty-four. The 0.6 to 0.8 child differences in ideals became 0.4 child differences in intentions, collapsing to a statistically insignificant 0.2 child difference in actual fertility histories.

It seems that climate-change and overpopulation worries have fairly modest effects on fertility outcomes, that is, on the number of children born, if any. The lack of a statistically meaningful effect among women nearing the end of their reproductive years suggests that climate-change and overpopulation worries could operate more as rationalizations for postponed or delayed fertility than as motivations for ultimately lower fertility.

In additional tests not shown here, climate-change worry was found to be not associated with lower childbearing for women at any point under age thirty or over age thirty-four. It predicts lower childbearing only at ages thirty to thirty-four, consistent with the idea that climate-change worry is most associated with postponement of fertility into the late thirties instead of late twenties, rather than associated with a total reduction in fertility. While there could be unobserved cohort differences affecting these comparisons, further evidence is discussed below to support the view that climate-change worry does not greatly shape fertility behaviour.

The Role of Broader Attitudinal Sets

Climate-change worry varies dramatically by political affiliation, ranging from practically zero among women voting for some political parties, to a near-majority of women voting for other political parties (figure 4). This wide variation invites the question of how political affiliation interacts with women’s perceptions of worries and risks that may influence their childbearing plans.

This report does not argue that political affiliation is a uniquely powerful cause of fertility ideals or values. Rather, it may be one of many possible proxies for differences in broad attitudinal sets, values, or even subcultures within Canadian society. This exploration of political differences continues a line of inquiry begun in the previous report that assessed the role of religion in shaping fertility preferences, suggesting that religiosity may have a protective role with respect to many common worries and anxieties. Here, the focus is on the extent to which reported worries about climate change and overpopulation may predict differences in fertility dispositions among women with particular political affiliations.

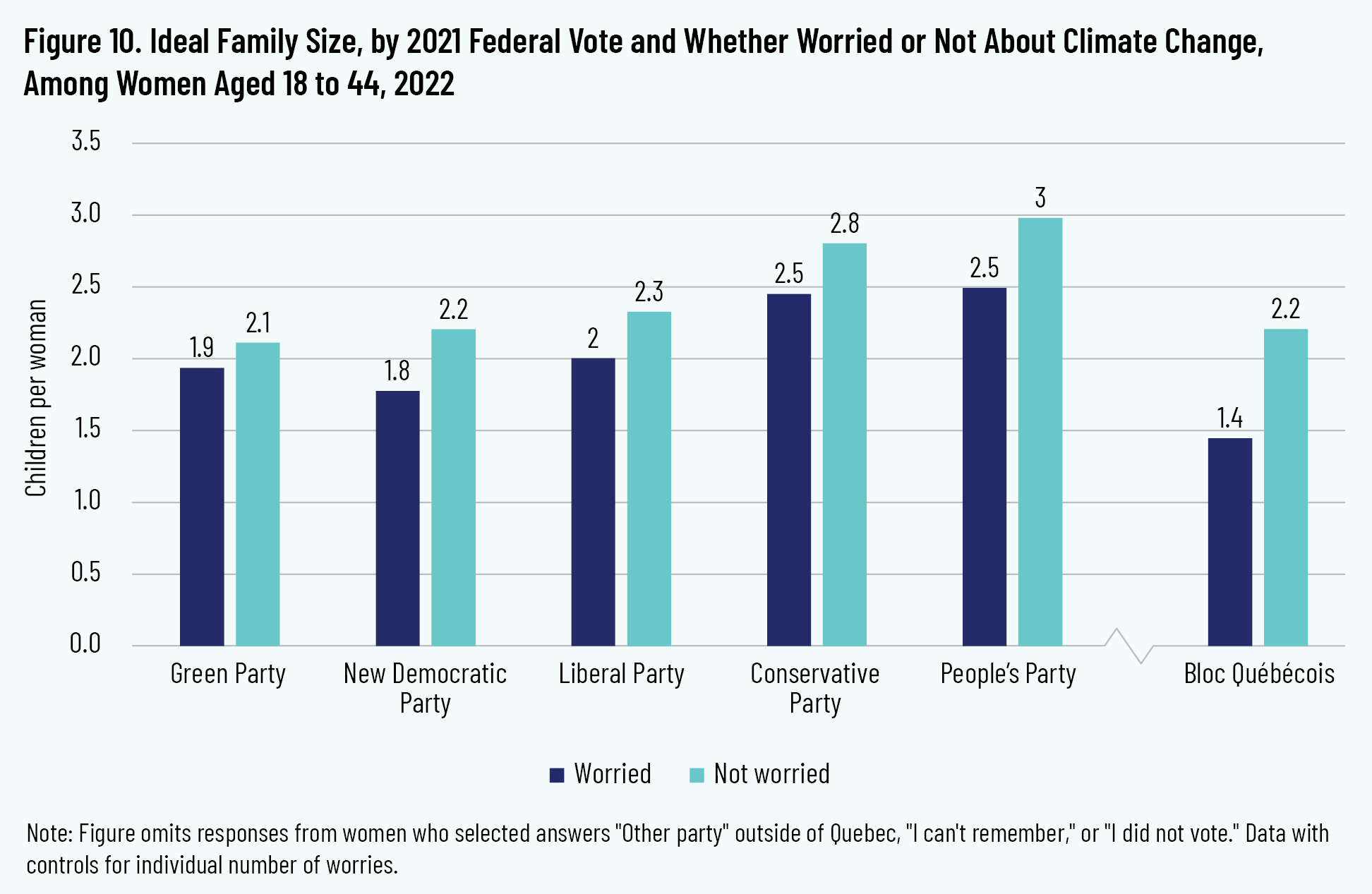

In essence, this approach explores the extent to which climate-change worry predicts actual lower family size because women are worried about climate change, versus simply because this worry is part of a package of belief associated with broader support for a particular political party. Figure 10 below shows results for ideal family size.

Across voting behaviour for the six major parties, women who report concern about climate change do tend to have lower ideal family sizes than women who do not share this concern. These effects are most noticeable for Bloc Québécois voters, with a difference of 0.8 children per woman between worried and not-worried voters. For women who voted for the other five parties, however, gaps range from 0.2 to 0.5 children per woman, in every case smaller than the 0.6 gap found in figure 6.

Within the same political party, given the modest sample sizes involved, ideal family sizes for women worried about climate change are not significantly different from ideal family sizes for women who are not worried about climate change. This was true in every political party analyzed. Whether Green Party voters do or do not report that climate-change worry influenced their childbearing plans, these voters overall reported lower fertility ideals than did those who voted for other parties. The opposite is true for women who voted Conservative. For example, Conservative-voting women who were worried about climate change desired more children (2.5) than Liberal-voting women who were not worried about climate change (2.3), to say nothing of the gaps for the parties that are further from the centre of the political spectrum.

It appears that voting behaviour in the past federal election is strongly associated with ideal family size, and that concerns about climate change do not predict much additional difference in fertility ideals. Most of the association between climate-change worry and fertility ideals is really an association between political affiliation and ideals, and an association between climate change and political affiliation.

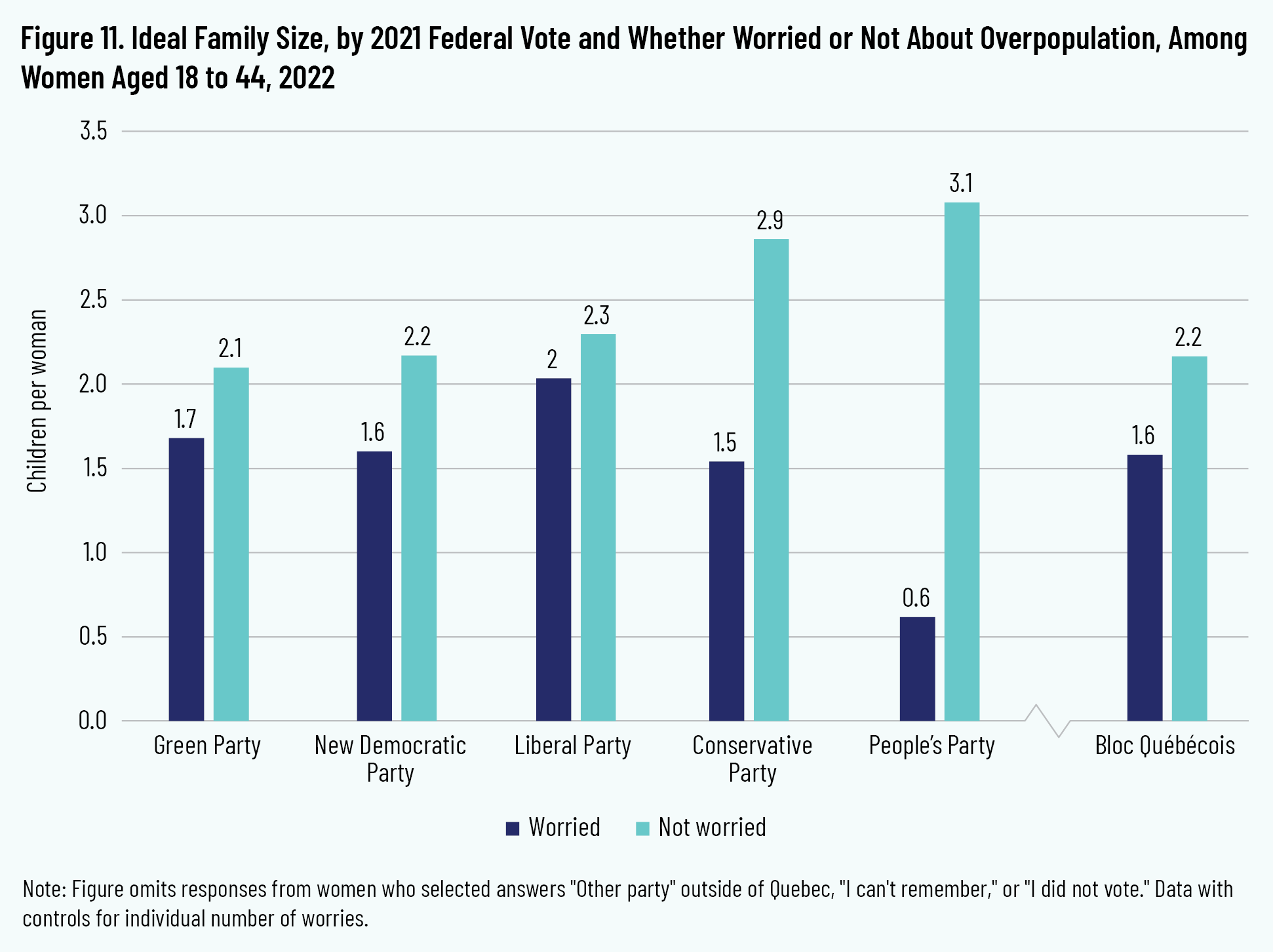

Figure 11 uses the same approach, but for overpopulation worry instead of climate-change worry. Here, there are larger effects. For women who voted for the NDP, Conservative Party, and People’s Party, overpopulation worry did predict statistically significant lower ideal family size. Overpopulation worry is rare in the right-leaning parties (as shown in figure 4), but where it does occur, it predicts far lower fertility ideals. Future studies with larger samples of women who voted for right-leaning parties should explore the nature of this phenomenon.

Thus, while climate-change worry is not very predictive of different fertility preferences once political affiliation is controlled for, overpopulation worry is still somewhat predictive of lower ideals, especially for women who voted for a right-leaning political party.

Fertility Gaps and Climate-Change Worry

Finally, the survey data were assessed to determine whether women with climate-change worry differed from other women who did not have this worry in terms of the congruence between their fertility preferences and outcomes. For each age group of women, and controlling for general worry-proneness, figure 12 shows their ideal family size, intended family size, and actual children ever born.

There is not much variation across age groups in ideal family size or intended family size. As described above, however, there is considerable difference between women who are or are not worried about climate change. Women worried about climate change ideally would like about 1.8 children, and intend to have about 1.5. Other women ideally would like about 2.4 or 2.5 children, and intend about 2. Actual number of children, however, changes a great deal across age groups. At every age group, women who are worried about climate change have fewer children, although (as discussed earlier) this effect is statistically significant only for women aged thirty to thirty-four.

From these estimates, computation can be made for the approximate fertility gaps, that is, the mean number of “excess” or “missing” children that women have near the end of their reproductive years. For women worried about climate change, actual fertility at ages forty to forty-four is about 0.4 children below their ideals and about 0.1 children below their intentions. For other women at ages forty to forty-four, actual fertility is about 0.8 children below their ideals and about 0.2 children below their intentions.

Thus, regardless of climate-change worry, Canadian women want more children, and they are undershooting even their intentions. While many Canadian women worry about the impact that climate change may have on their children (and about the impact that their children may have on climate change), they nonetheless want more children.

Conclusion

Climate change is a pressing issue of public concern, one that is frequently associated with overpopulation. As such, it is often thought to have dramatic implications for fertility outcomes. Media stories often feature young people curtailing family formation with the aim of not adding to this challenge of climate change. And yet, this study has found relatively little evidence that worry about climate change does in fact shape fertility rates. This finding is in keeping with recent academic research, which has found inconsistent effects of climate-change worry and fertility attitudes, with generally very small effects outside of declines in desires for very large families.

4

4

S. Arnocky, D. Dupuis, and M.L. Stroink, “Environmental Concern and Fertility Intentions Among Canadian University Students,” Population and Environment 34, no. 2 (2012): 279–92, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-011-0164-y; A. De Rose, and M.R. Testa, “Climate Change and Reproductive Intentions in Europe,” in Italy in a European context: Research in Business, Economics, and the Environment, ed. D. Strangio and G. Sancetta (Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015); A.C. Davis, S. Arnocky, and M. Stroink, “The Problem of Overpopulation: Proenvironmental Concerns and Behavior Predict Reproductive Attitudes,” Ecopsychology 11, no. 2 (2019): 92–100, https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0068; H.M. Rackin, A. Gemmill, and C.S. Hartnett, “Environmental Attitudes and Fertility Desires Among US Adolescents from 2005–2019,” Journal of Marriage and Family 85, no. 2 (2023): 279–292, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12885.

The present study has found that Canadian women reporting that a concern about climate change influences their childbearing plans also reported lower fertility ideals than women who did not report this concern (0.6 children lower), but this gap shrinks for intentions (0.4 children lower), and shrinks still further for actual fertility outcomes (0.2 children lower).

Moreover, the apparently large gap in ideals is mostly attributable to the broader attitudinal set associated with political affiliation rather than to worry about climate change per se. Both women worried about climate change and other women who are not worried about it report considerable gaps between desired and actual fertility, suggesting that climate-change worry doesn’t prevent women from desiring more children than they currently have.

On the other hand, overpopulation worry, which is not synonymous with climate-change worry, may have a more significant effect on fertility outcomes. In this survey of Canadian women, overpopulation worry predicted lower fertility ideals (0.8) and intentions (0.4), and insignificantly lower actual fertility (0.2). However, the negative association between overpopulation worry and fertility ideals persisted even after controls for political affiliation were included.

Perhaps surprisingly, overpopulation worry existed even among women who did not express climate-change worry, and overpopulation worry had the largest association with fertility among women who voted for a right-leaning party in the most recent federal election.

Despite the idiosyncratic low fertility preferences of a small subset of overpopulation-concerned right-leaning women, right-leaning women in general still reported much higher fertility ideals. Due to the limited sample size, further conclusions cannot be drawn about this data point, and the relation between these two variables would be a valuable area for future study.

The findings suggest in general that the much-heralded role of climate-change worry in shaping fertility behaviours is overstated. Rather, some women who, based on their voting behaviour, may be viewed as being in broadly “less family-oriented” circles, may adopt climate-change concern as rationalization for broader value sets or life experiences influencing their childbearing plans. Other women in those circles shared other concerns influencing their childbearing plans, but had similar ultimate ideals and plans.

The key take-away, however, is that many of these fertility concerns may be rationalizations: women with similar voting behaviour, but with different concerns, have about the same ideal family size. Ideal family size (and subsequent fertility behaviour) is complex and based in a comprehensive package of cultural beliefs, not just one or two specific concerns.

As policymakers think about climate change and fertility, then, it would be prudent for them to be less concerned with a link between climate change and fertility (or any specific worry and fertility), and more concerned with why many women today feel a need to adopt various rationalizations for low fertility. Prior research suggests that the rise in mood and behavioural disorders may be a major culprit in driving low fertility. 5 5 L. Stone, “More Anxiety, Fewer Children: Mental Health and Fertility in America,” Institute for Family Studies, September 20, 2022, https://ifstudies.org/blog/more-anxiety-fewer-children-mental-health-and-fertility-in-america. This report is not able to assess whether the worry-proneness that it measured is correlated with diagnosed mood and behavioural disorders, or symptoms of them. In general, however, public-health interventions aimed at promoting healthy cognitive patterns, and better understanding of the etiology of recent increases in these conditions, may do more to support fertility than efforts to address one or another specific worry.

A better predictor of low fertility preferences and outcomes than concerns about climate change or overpopulation is simply the total number of worries that a woman reported in the survey. Even when controlling for political affiliation, religion, level of education, age, and ethnic background, the sheer number of worries that a woman selected on the list of worries strongly predicted her fertility ideals, intentions, and outcomes. Instead of focusing on one worry or another (whether climate change, childcare availability or cost, overpopulation, housing costs, or some other), policymakers should consider what life course and socialization factors are generating systematically higher rates of fertility-related worry or anxiety for some women.

References

Arnocky, S., D. Dupuis, and M.L. Stroink. “Environmental Concern and Fertility Intentions Among Canadian University Students.” Population and Environment 34, no. 2 (2012): 279–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-011-0164-y.

Davis, A.C., S. Arnocky, and M. Stroink. “The Problem of Overpopulation: Proenvironmental Concerns and Behavior Predict Reproductive Attitudes.” Ecopsychology 11, no. 2 (2019): 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2018.0068.

De Rose, A. and M.R. Testa. “Climate Change and Reproductive Intentions in Europe.” In Italy in a European Context: Research in Business, Economics, and the Environment, edited by D. Strangio and G. Sancetta. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Rackin, H.M., A. Gemmill, and C.S. Hartnett. “Environmental Attitudes and Fertility Desires Among US Adolescents from 2005–2019.” Journal of Marriage and Family 85, no. 2 (2023): 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12885.

Stone, L. “More Anxiety, Fewer Children: Mental Health and Fertility in America.” Institute for Family Studies, September 20, 2022. https://ifstudies.org/blog/more-anxiety-fewer-children-mental-health-and-fertility-in-america.

———. “Religion and Fertility in Canada.” Cardus, 2023. https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/reports/religion-and-fertility-in-canada.

———. “She’s (Not) Having a Baby: Why Half of Canadian Women Are Falling Short of Their Fertility Desires.” Cardus, 2023. https://www.cardus.ca/research/family/reports/she-s-not-having-a-baby/.

Wray, B. “Deciding to Have a Baby Amid the Climate Crisis: Whatever You’re Feeling, You’re Not Alone.” CBC News, November 24, 2022. https://www.cbc.ca/documentaries/deciding-to-have-a-baby-amid-the-climate-crisis-whatever-you-re-feeling-you-re-not-alone-1.6662734.