Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Canada’s fertility rate has fallen persistently for the last 15 years with no clear bottom in sight. To some commentators, this is a harbinger of troubles ahead, as smaller and smaller cohorts of young Canadians may struggle to bear the load of supporting retirees and integrating immigrants. To others, this is cause for celebration—a victory for women’s equality and a boon in combatting climate change.

In this report, we introduce another perspective on Canada’s falling fertility rates, asking not how the fertility choices of Canadian women affect the economy or the environment but whether those behaviours reflect what women want. Through a novel survey of nearly 3,000 women aged 18 to 44, we explore family and fertility preferences, expectations, and outcomes.

We find that few women in Canada have “excess” (undesired) births but that a considerable share of Canadian women will end their reproductive years with “missing” children, that is, reporting that they desire more children that they will not likely have. Women with “missing” children are not an exception. They make up almost half of women near the end of their reproductive careers, and they report lower life satisfaction than women who achieve their family-size desires.

We also investigate what factors influence Canadian women’s fertility plans. Investigating issues as diverse as work-life balance, finances, climate change, and many other topics, we assess the extent to which women who report specific concerns revise their concrete fertility plans to levels below those they say would be ideal for them. We find that pared-down family plans do not arise from positive circumstances but instead are strongly associated with women reporting life challenges of various kinds, ranging from concerns about the demands of parenting, to unsupportive partners, to excess housing costs, to feeling that they have not yet had suitable opportunities for self-development. In short, low Canadian fertility rates are not the product of wanting few children but of a structural problem in advanced economies: the timeline that most women follow for school, work, self-development, and marriage simply leaves too few economically stable years left to achieve the families they want. This dynamic leaves Canadian women with fewer children than they would like, alongside reduced life satisfaction.

This study is based on a survey commissioned by Cardus and conducted by the Angus Reid Group in July 2022. It surveyed 1,000 native-born women aged 18–44 who chose to complete the survey in English, 1,000 native-born women aged 18–44 who chose to complete the survey in French, and 700 foreign-born women aged 18–44 who completed the survey in either language. Respondents were then re-weighted to match the population of Canadian women by province, age, language, income, sexual orientation, and household structure (marital status and children).

Introduction

Canada’s fertility rate has fallen persistently for the last 15 years, with no clear bottom in sight. 1 1 “The total fertility rate in a specific year is defined as the total number of children that would be born to each woman if she were to live to the end of her child-bearing years and give birth to children in alignment with the prevailing age-specific fertility rates.” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Fertility Rates,” 2023, https://data.oecd.org/pop/fertility-rates.htm. To some commentators, this is a harbinger of troubles ahead, as smaller and smaller cohorts of young Canadians may struggle to bear the load of supporting retirees and integrating immigrants. To others, this is cause for celebration—a victory for women’s equality and a boon in combatting climate change. In this report, we introduce another perspective on Canada’s falling fertility rates, asking not how the fertility choices of Canadian women affect the economy or the environment, but whether those behaviours are the result of women achieving the lives that they want.

Demographers around the world have often pointed to various problems associated with excessively high or low fertility rates. High fertility is said to contribute to climate change and environmental degradation, limit women’s achievement in their career aspirations, and create health risks for women. Low fertility is said to lead to economic stagnation and inequality, labour shortages, and increased tension between native-born citizens and immigrants. What all of these concerns disregard, however, are the hopes and plans of women themselves. They all refer to effects of changes in aggregate fertility independent of women’s desires. Public policy that does not first and foremost consider the affected human persons and their own wishes may result in dehumanizing and illiberal results, as it has for example with forced sterilization in Canada. 2 2 Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights, “Forced and Coerced Sterilization of Persons in Canada,” June 2021, https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/432/RIDR/reports/2021-06-03_ForcedSterilization_E.pdf. In short, when women’s fertility desires are not taken into account, family policy can go awry.

Childbearing is a biological human universal. In every culture and society, children are born, parental rights are recognized, and mothers want help from partners and wider society in raising their children. Academic research using longitudinal data has found that survey reports of fertility preferences are among the strongest predictors in existence of subsequent fertility outcomes. 3 3 L. Bumpass and C.F. Westoff, “The Prediction of Completed Fertility,” Demography 6, no. 4 (1969): 445–54; L.C. Coombs, “Reproductive Goals and Achieved Fertility: A Fifteen-Year Perspective,” Demography 16, no. 4 (1979): 523–34; J. Cleland, K. Machiyama, and J.B. Casterline, “Fertility Preferences and Subsequent Childbearing in Africa and Asia: A Synthesis of Evidence form Longitudinal Studies in 28 Populations,” Journal of Population Studies 74, no. 1 (2020): 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2019.1672880. When women say in surveys that they want to have more children (or that they’ve had more children than they would have preferred), they are typically giving accurate answers to questions that they are well equipped to answer. We should listen to the answers these women give.

Methodology

We surveyed 2,700 women in Canada aged 18 to 44 about family and fertility. 4 4 Only respondents who are natal females (that is, who indicated that their sex at birth was female) were included in the survey, as they are the only ones able to gestate children and thus the core population of interest for questions about fertility. Natal female respondents who indicated that they do not identify as women were included in the survey and made up fewer than 2 percent of respondents; as a result, we generally refer to respondents as a group as women. Our sample had three stratified elements: 1,000 native-born women surveyed in English, 1,000 native-born women surveyed in French, and 700 foreign-born women surveyed in French or English. The sample was stratified in this way in order to ensure good coverage of Canada’s diverse society. Respondents were re-weighted to ensure that they are representative of Canadian women on the whole by age, language, income, province, sexual orientation, and household structure (marital status and children). Incidence rates and completion times for native-born Anglophone and Francophone respondents were similar and within normal ranges; incidence rates for foreign-born respondents were low, indicating some difficulty recruiting these respondents.

Overall, four major findings arise from this survey:

- Women in Canada at the end of their reproductive years have about 0.5 fewer children than they desire, on average. “Missing” births vastly outnumber “excess” births. Nearly half of women at the end of their reproductive years have had fewer children than they wanted.

- Women who accomplish their fertility desires are happier than women who have more or fewer children than they desire. Although “excess” births have a larger unhappiness effect than “missing” births individually, Canadian women lose more aggregate life satisfaction from “missing” than from “excess” births, because “missing” births are almost four times as common. In short, “missing” births are a larger social problem.

- Many factors influence Canadian women in having fewer children than they desire, but the most influential factors relate to the ideas that children are burdensome, that parenting is intensive and time-consuming, and that women want to finish self-development and exploration before having children. The view that parenting is demanding is a bigger factor for low fertility than is housing or childcare costs.

- In Canada, unlike many other countries, fertility rates and desires rise with income: richer Canadians have more children. Children increasingly come as a capstone to material and relational success, and thus later in life, rather than as a building block for family life.

Key Fertility Indicators for Canada

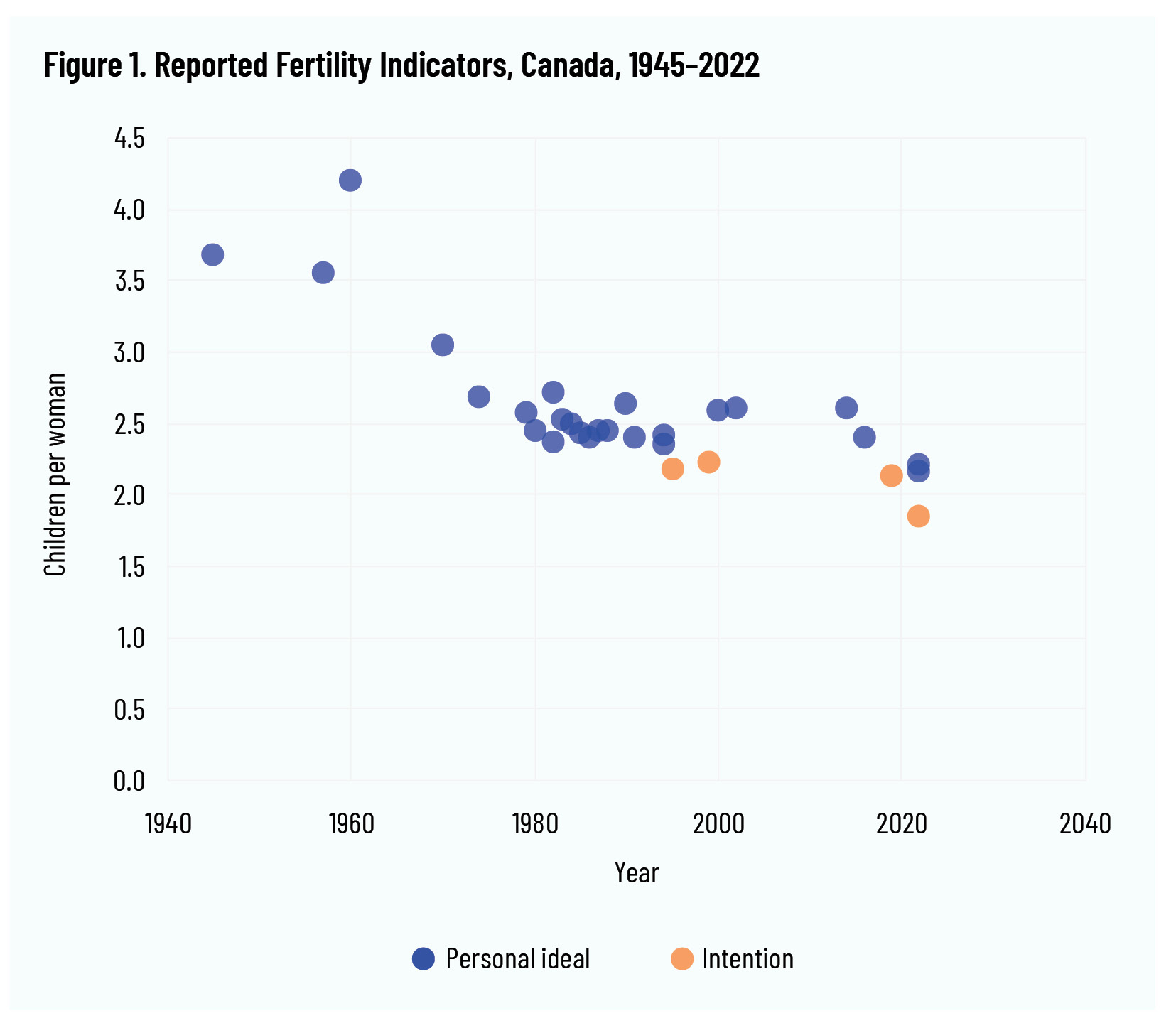

Surveys of fertility preferences in Canada have a long history, with the first such survey conducted in 1945 by Gallup. We identified a total of 26 prior surveys that collected fertility-preference indicators for Canada. Figure 1 shows women’s personal ideal versus intended family size, from 1945 to 2022. The mean number of children desired (ideal family size) is in blue, and the intended number is in orange.

It is exceedingly rare in contexts where women have equality before the law for women to “intend” children they do not “desire.” But it is very common for women to “desire” children they do not “intend,” because they think those children are unobtainable, for various reasons. Thus, intentions represent a compromise between desires and reality and are almost always lower than ideals or desires.

In the 1940s to 1960s, Canadian women tended to say that they desired three or four children. But by the 1980s, there had been a decline to around two or three. Starting in the 1990s, surveyed fertility intentions were appreciably lower than desires, just above two children per woman. While the difference may not seem large, it is highly significant. Essentially, there were a considerable number of women who report desiring three children but intending two, or desiring two but intending just one.

The survey we have just completed is the last set of indicators in figure 1: two blue dots for two indicators of desire, and one orange dot indicating intention. We used two fertility-desire questions, one modelled on the US General Social Survey (“How many children would you say is ideal for a family to have?”) and one duplicated from the international Demographic and Health Surveys (“If you could choose exactly the number of children to have in your whole life, how many would that be?”). We also duplicated the Canadian General Social Survey Family Cycle’s question about how many more children women intended to have.

As can be seen, we found lower fertility intentions than any prior survey, at around 1.85 children per woman, as well as lower fertility desires, at around 2.2 children per woman. This is consistent with a December 2021 Statistics Canada report suggesting that Canadian women’s fertility desires fell during the COVID-19 pandemic. 5 5 A. Fostik and N. Galbraith, “Changes in Fertility Intentions in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Statistics Canada, December 2021, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00041-eng.htm. Fertility preferences in Canada have fallen markedly as the shock of COVID-19 and other world events may have led many women to reconsider what kind of family life they want. Nonetheless, most Canadian women still want two or more children.

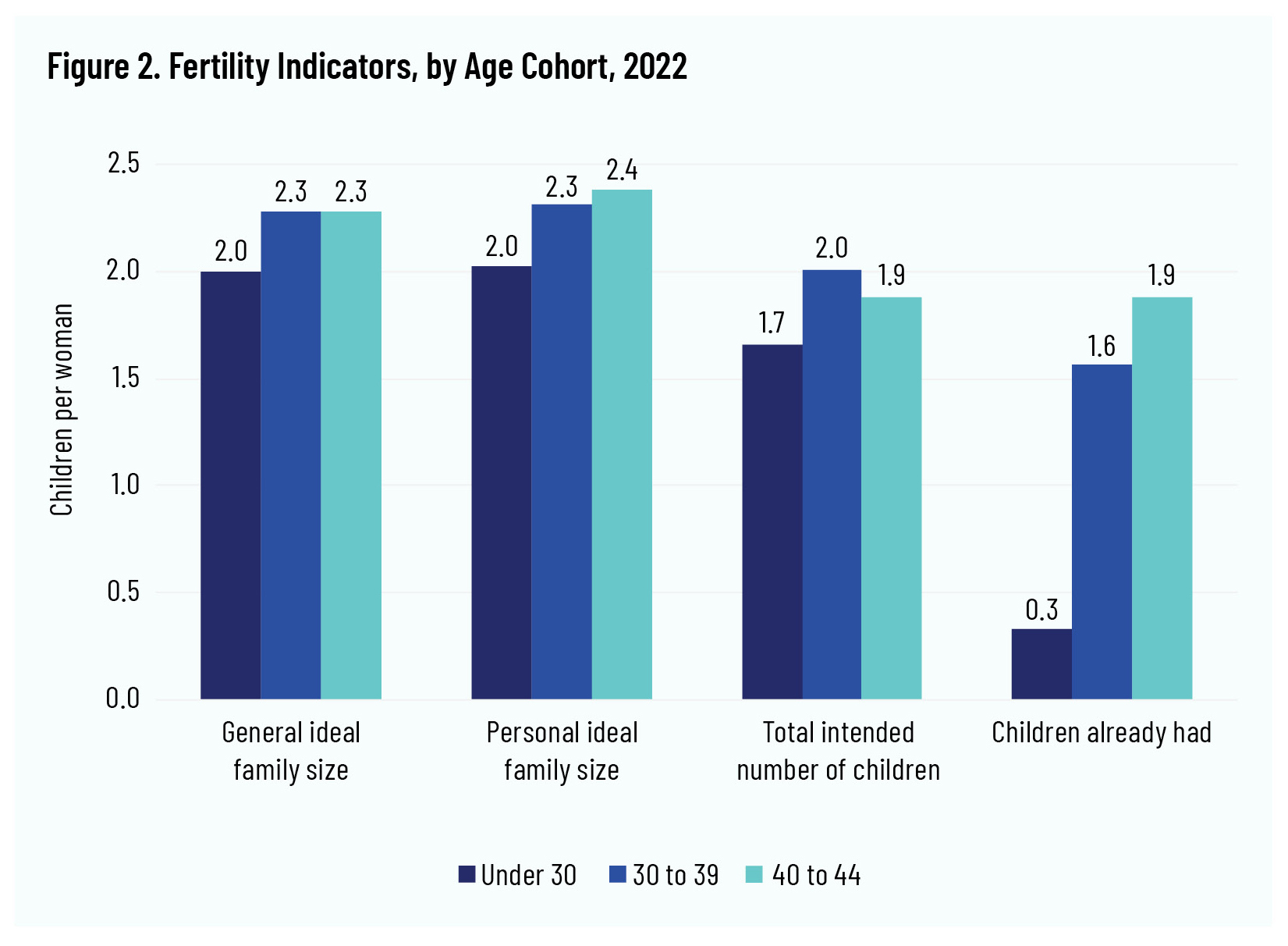

Figure 2 shows selected fertility indicators by broad age groups for Canadian women. These age groups were selected to ensure meaningful sample sizes in each group; the under-30 group in particular was pooled because many women in that age group have not yet begun pursuing their family goals and their survey responses may be more erratic.

In general, older Canadian women have higher fertility desires and intentions than younger women. It is not possible to say to what extent this difference is driven by changes in women’s family-size desires as they age, versus differences in cohorts. Overall, older women want more children for themselves (the personal ideal family size) than they say is ideal for women in general. At the same time, fertility intentions are well below fertility ideals: women in their 30s intend just two children (including those they already have), while women aged 40 to 44 intend even fewer. Women under 30 years of age intend about 1.6 children. It is worth noting, however, that Canada’s current fertility rate suggests that women under 30 years of age will actually have only about 1.4 children on average, if current trends continue. Thus, even Canadian women with these very low intentions will tend to undershoot their intentions, to say nothing of their desires.

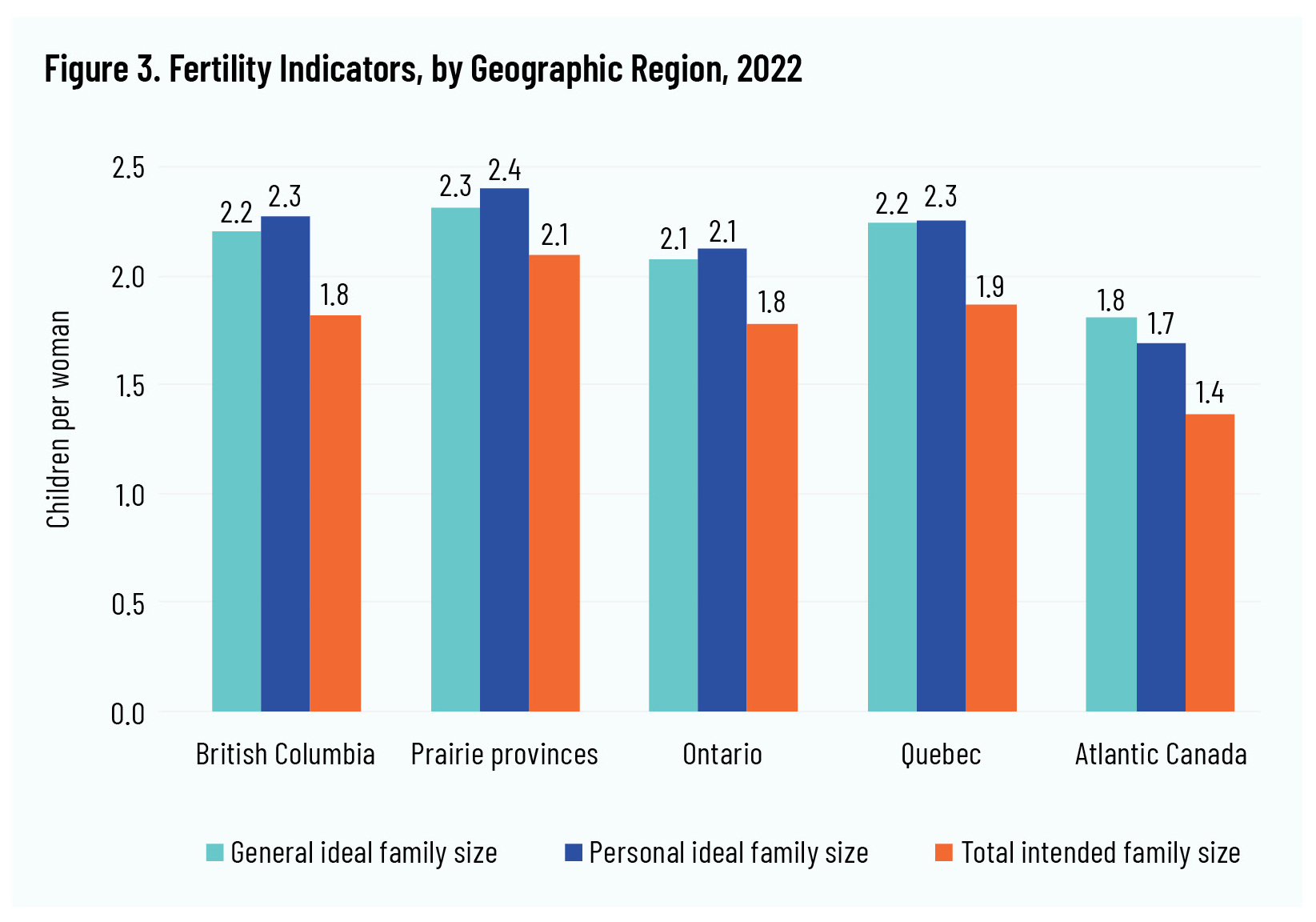

There are also important regional differences in fertility preferences, as shown in figure 3.

Women in the prairie provinces report the highest fertility desires and are the only geographic grouping who have actual intentions to have at least two children. Meanwhile, women in Atlantic Canada have unusually low fertility preferences and even lower intentions. We find that these regional patterns are similar to those found in the latest Canadian General Social Survey Family Cycle, except that fertility intentions in Quebec have fallen more than in other provinces. In general, across every province, women intend to have fewer children than they say would be ideal for them.

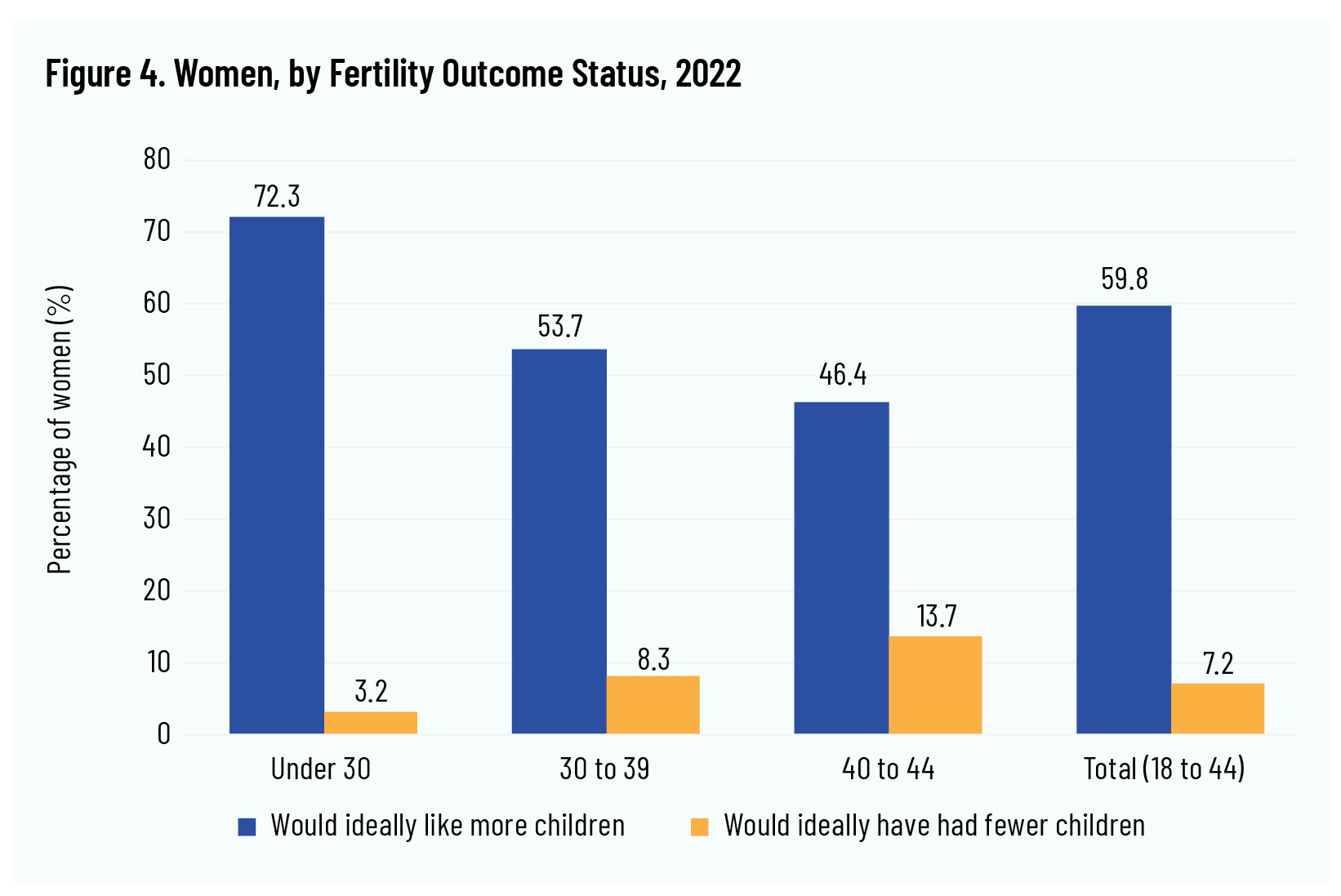

But exactly how common is such undershooting? Figure 4 shows the share of women in each age group who report having had more children than they consider ideal for them versus those who report having had fewer.

Naturally, a large share of women under the age of 30 report that their ideal number of children is higher than their childbearing to date: these are young women with childbearing years ahead of them. But even among women in their early 40s, about 45 percent report a personal fertility ideal higher than their current number of children, whereas just 14 percent report that they would have preferred fewer children. In other words, even among women near the end of their reproductive years, “missing” births are over three times as common as “excess” births. These 14 percent who would “ideally have had fewer children” are not necessarily expressing regret about their outcomes. We asked women how many children they would have if they had their life to do over again. Women might be perfectly happy with the number of children they had, even if, were they to replay their life with knowledge acquired through it, they might have made different choices.

Helping women avoid undesired childbearing is an important interest, which policymakers should care about. However, our survey reveals that there are far more women who struggle with age-related infertility or miscarriage or who feel daunted by the demands of childbearing, and they also represent an important social interest. As much as society and policymakers may devote resources to helping avoid undesired pregnancies, it would be reasonable to devote resources to helping achieve desired pregnancies. A society in which women have agency over their reproduction is one in which they can avoid undesired childbearing and achieve desired childbearing. Currently, one half of the women in Canada effectively achieve only one side of that equation by the end of their reproductive years. They are having fewer children than they say would be ideal for them, and indeed are not even planning to achieve their ideals, for reasons we discuss below.

Fertility and Life Satisfaction

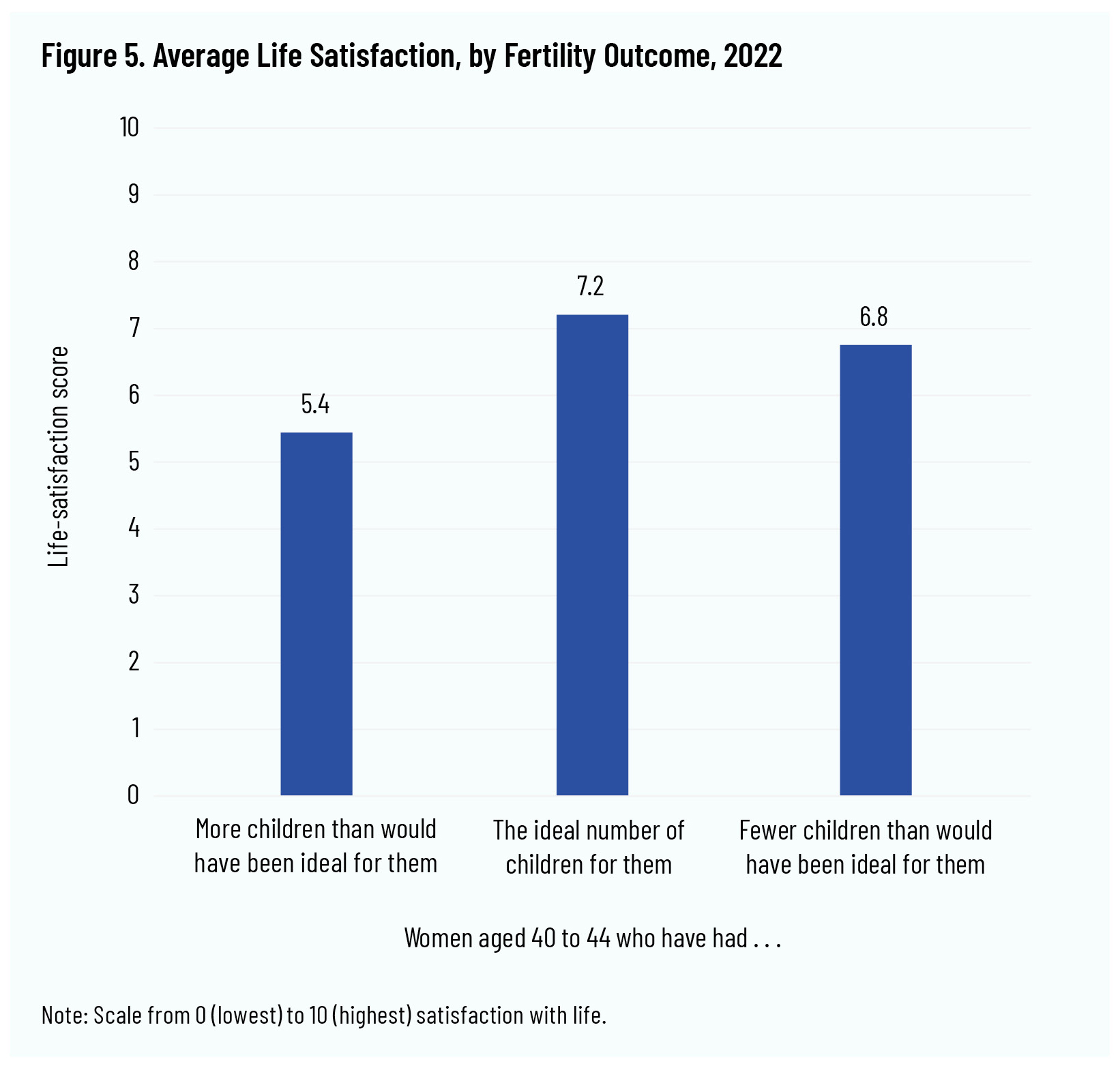

How are “missing” and “excess” children related to a woman’s satisfaction with life? Figure 5 shows the average life satisfaction reported by women in each category. The wording of the question that we used to measure life satisfaction comes from a well-tested survey instrument in use around the world. Higher life satisfaction is strongly correlated with better physical and mental health. 6 6 F. Cheung and R.E. Lucas, “Assessing the Validity of Single-Item Life Satisfaction Measures: Results From Three Large Samples,” Quality of Life Research 23, no. 10 (2014): 2809–18, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11136-014-0726-4; D.M. Fergusson et al., “Life Satisfaction and Mental Health Problems (18 to 35 years),” Psychological Medicine 45, no. 11 (2015): 2427–36, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291715000422; M. Luhmann et al., “The Prospective Effect of Life Satisfaction on Life Events,” Social Psychological and Personality Science 4, no. 1 (2013): 39–45, https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612440105; C.L. Chei et al., “Happy Older People Live Longer,” Age and Ageing 47, no. 6 (2018): 860–66, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy128.

Women aged 40 to 44 who have achieved their ideal number of children have an average life-satisfaction rating of 7.2 out of 10. Women who have had “excess” births report a much lower value on average, 5.44. But women who have had fewer children than desired also report an average lower life satisfaction: a score of just 6.8. Thus the decrease in average life satisfaction associated with “excess” births is 1.8 points and that associated with “missing” births is 0.46.

Knowing the approximate share of women who complete their reproductive years with “excess” or “missing” children, and knowing how much lower life satisfaction is for those two groups than for women who achieve their fertility target, it is possible to very roughly approximate the general social scale of each side of the fertility problem. No exact calculation of life satisfaction is credible, but when comparing two problems, if they have similar severity but one is three times as common, it’s reasonable to suggest that policymakers should give at least equal attention to the more common problem. So it is for fertility: women who experience “excess” childbearing have the lowest life satisfaction, but the share of these women is so much smaller than the share who experience “missing” childbearing that, on the whole, more lost-life-satisfaction is associated with “missing” than with “excess” fertility. The straightforward conclusion is that policymakers should consider “missing” children at least as serious a policy problem as “excess” or unwanted childbearing.

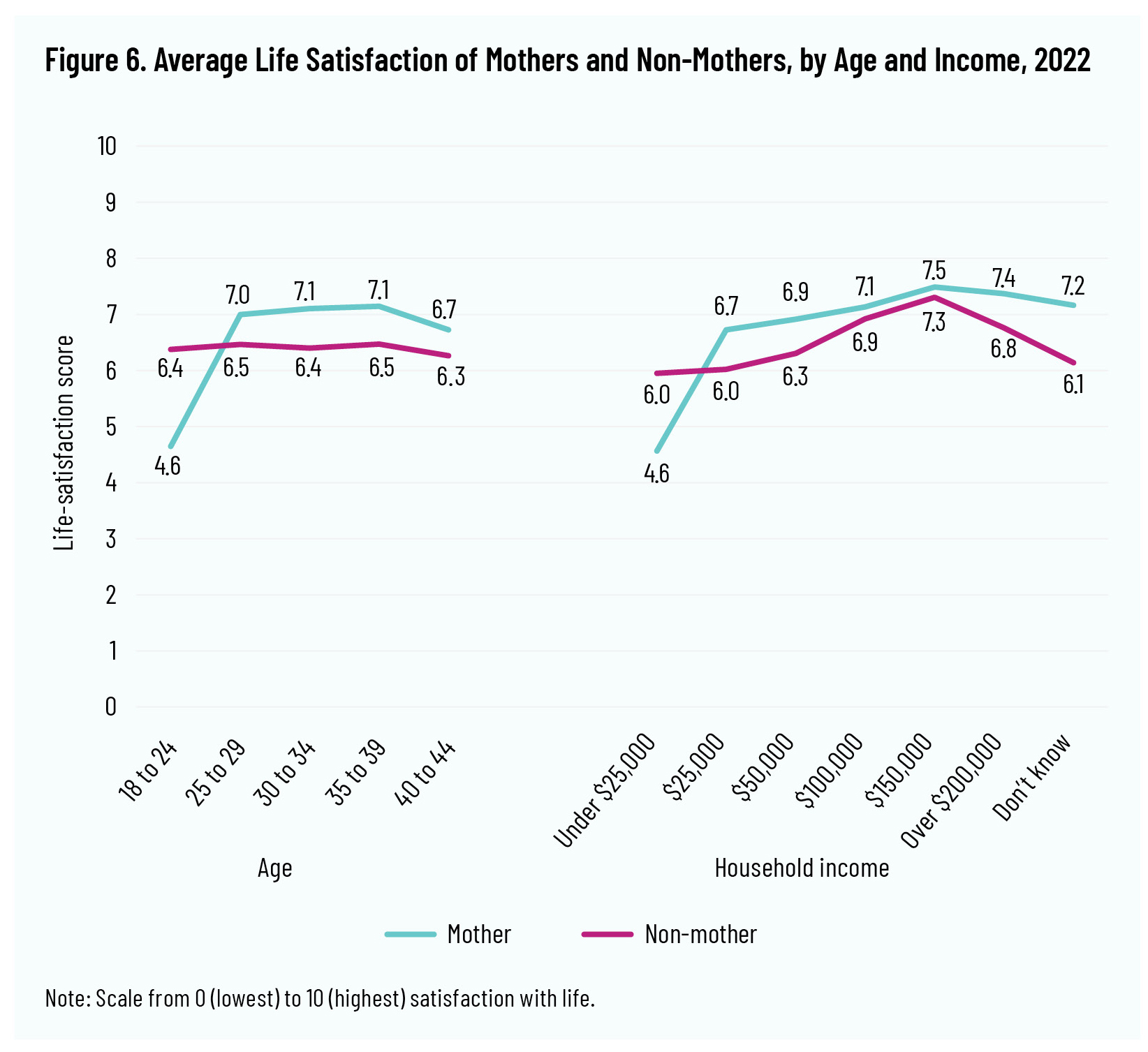

Numerous studies have analyzed how childbearing relates to happiness; it is not our goal here to assess them all. Most studies find rather modest effects, with no large change in happiness associated with having children. However, no study has assessed the role that childbearing preference plays in maternal happiness: having another child may have a different effect on the happiness of a woman who wants more children, compared to one who does not. Nonetheless, we did review how life satisfaction varies between mothers and non-mothers, by income and age, as shown in figure 6.

The relationship between motherhood and life satisfaction is highly dependent on contextual factors. Mothers under the age of 25 tend to be less happy on average than non-mothers in that age group. But women in their late 20s and older are appreciably happier than non-mothers. Likewise when it comes to household income, mothers in households earning under $25,000 annually are substantially less satisfied with their lives than non-mothers in the same income range. For every higher income level, mothers have similar or higher life satisfaction than non-mothers.

In sum, then, we find two important facts about life satisfaction among women in Canada. Women who have more or fewer children than they say would be ideal for them are less happy than women who have their ideal number of children, and among women in households earning more than $25,000 or over age 25, motherhood in general is associated with greater life satisfaction.

Differences by Income Level

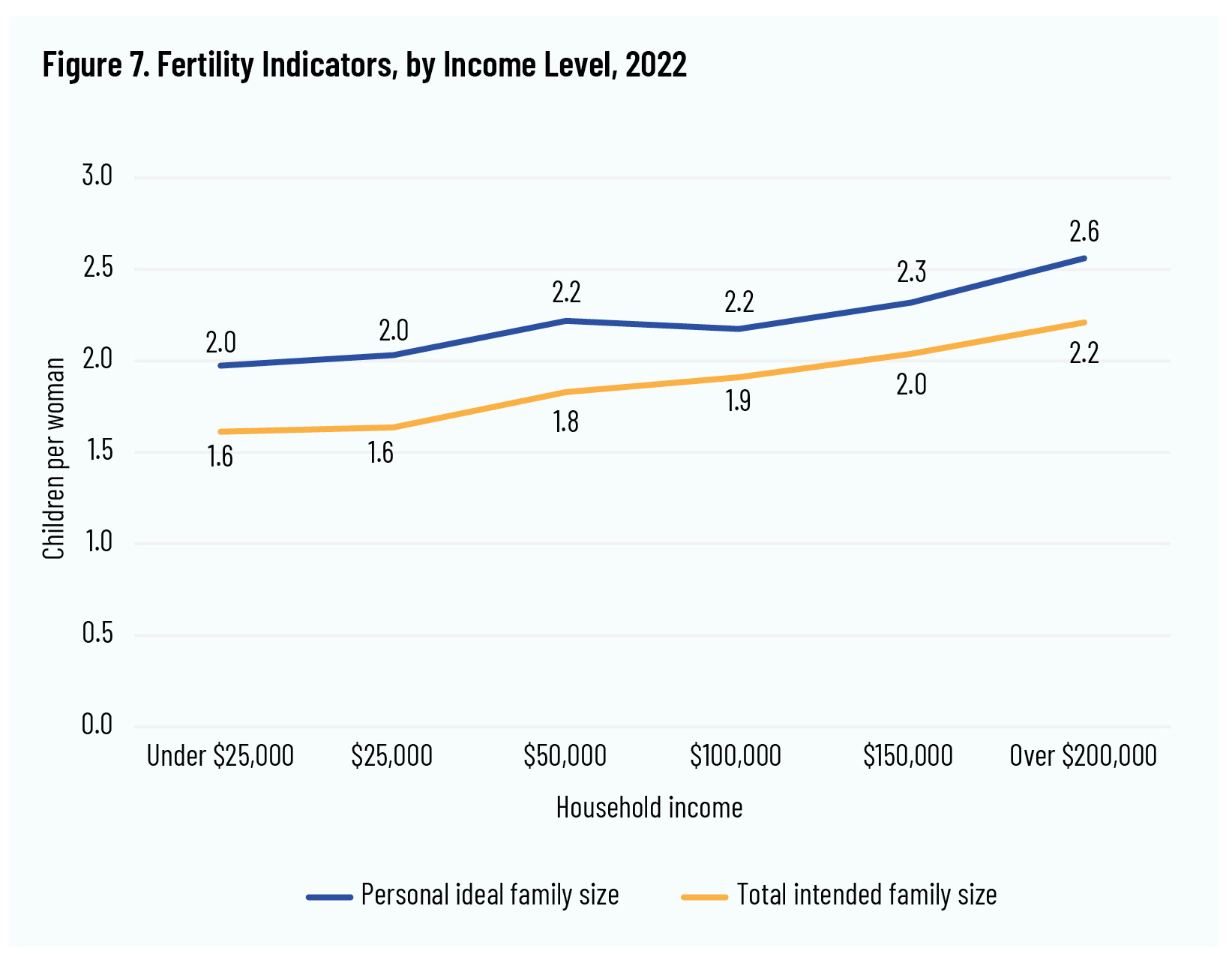

What differences in family life exist across women of different income groups? Figure 7 shows personal fertility ideals and intentions for women at each broad household-income grouping.

As can be seen, women in higher-income households both desire and intend to have larger families. What is somewhat less visually obvious is that the absolute gap between personal intentions and desires, which in essence measures the extent to which women expect their family plans to go unfulfilled, is largest for the poorest women. This is unusual, since in most countries, fertility tends to be lower among women in richer households. There are few international surveys that can produce comparable statistics, but a review of data for the US did not show a similar income gradient. Canada appears to be in an unusual position with respect to the relationship between income and fertility.

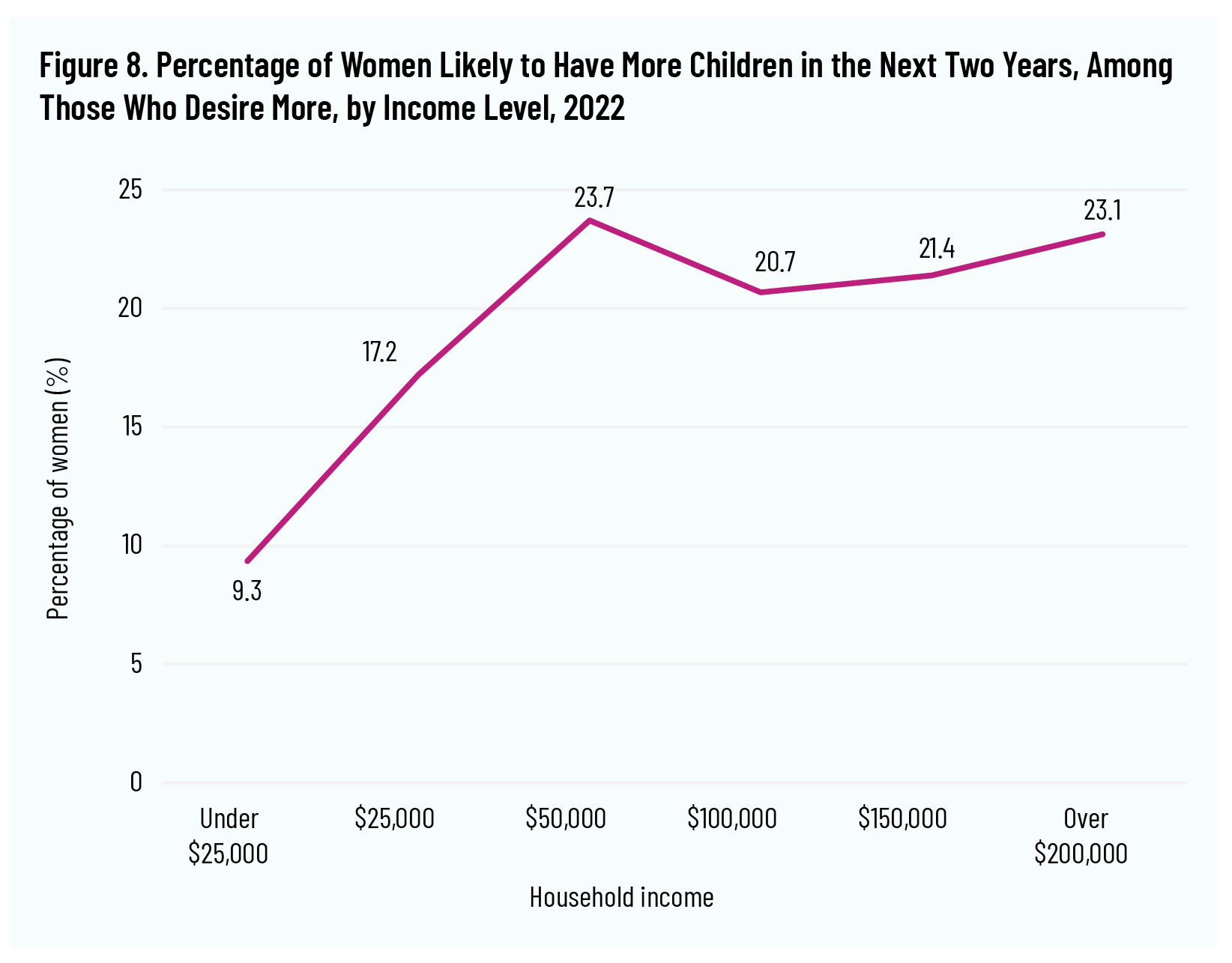

Other measures of fertility further support the idea that poorer Canadian women have a harder time achieving their fertility goals. Figure 8 looks at only those women who report a personal fertility ideal higher than their current number of children, and then shows what share of them think they are likely to have a child in the next two years. In other words, this question assesses the extent to which women have near-term plans to try to achieve their family goals. Demographic research suggests that these kinds of near-term expectations are fairly accurate projections. 7 7 Cleland, Machiyama, and Casterline, “Fertility Preferences.”

Poorer Canadian women have much lower expectations of children in the near future. This points to a vitally important reality: childbearing in Canada is becoming more associated with wealth than it is in other countries, and than it was in Canada in the past, as poorer women face difficulties manifesting their family desires. Poorer Canadian women don’t want, don’t intend, and aren’t having as many children. This is reminiscent of the growing inequality in marriage. Lower-income Canadians are less likely to marry than are higher-income Canadians. 8 8 P. Cross and P.J. Mitchell, “The Marriage Gap Between Rich and Poor Canadians,” Institute of Marriage and Family Canada, February 2014, https://www.cardus.ca/assets/data/files/IMFC/TheMarriageGapBetweenRichandPoorCanadians.pdf. These points may be related insofar as marriage is correlated with higher fertility. 9 9 L. Stone and S. James, “For Fertility, Marriage Still Matters,” Institute for Family Studies, October 2022, https://ifstudies.org/blog/new-report-for-fertility-marriage-still-matters.

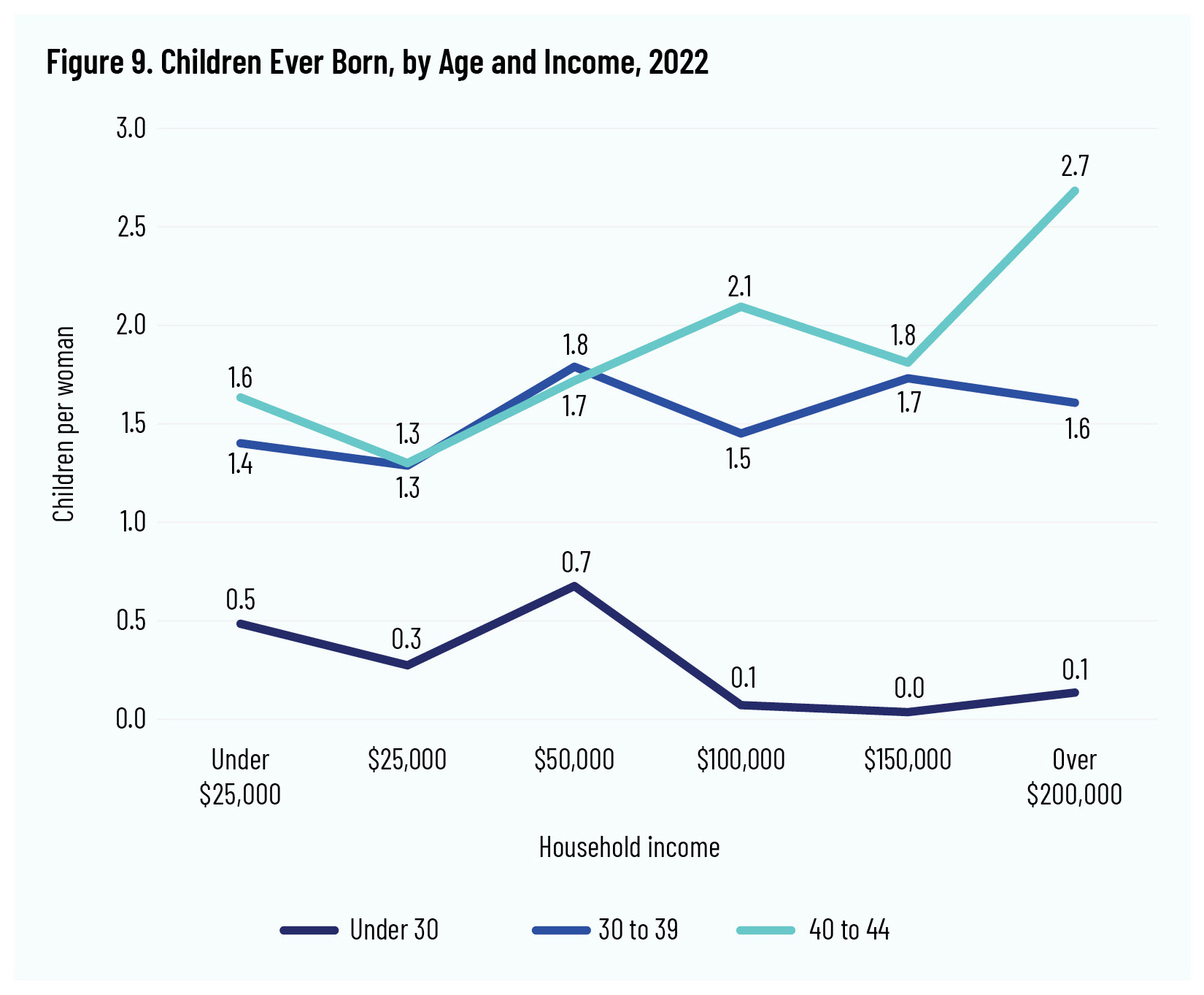

Figure 9 shows how differences in preferences shown in figure 8 are mirrored by differences in outcomes.

For women under 30, poorer women have had more kids. This may be because childbearing tends to come earlier for lower-income women in Canada, as it does for poorer women around the world, especially since pregnancy can interrupt schooling and lead to low income. For women in their 30s, there is little to no income gradient, but by their early 40s, richer women have appreciably more children than poorer women. This is consistent with timing differences as well. Richer women spend more years in school, get married later, and then tend to have children at a later age.

Differences by Ethno-Cultural Groups

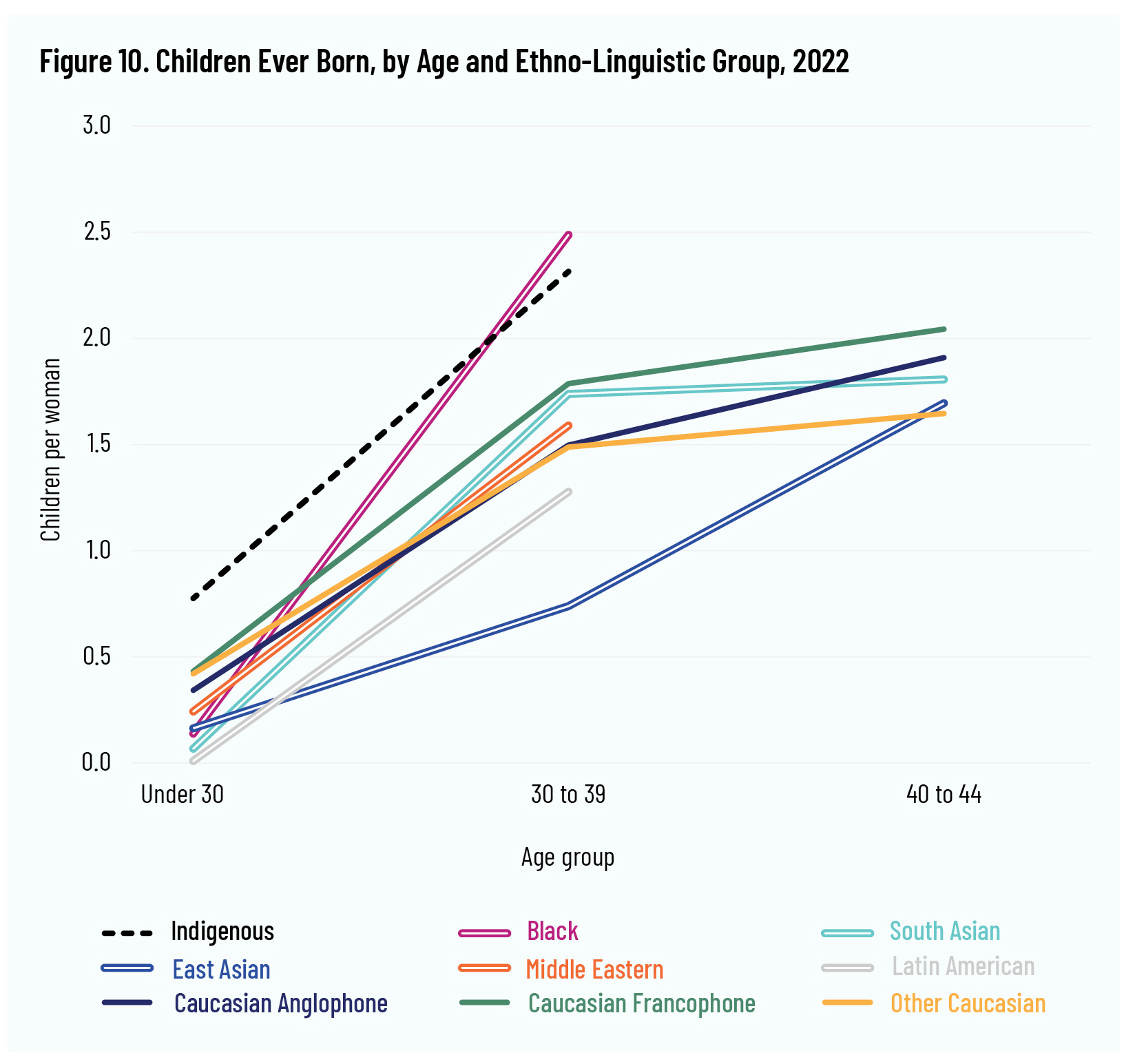

There are also meaningful differences in fertility across Canada’s ethnic, linguistic, and cultural groups. For this study, we group respondents based on ethnicity and language into nine categories: three language groups of Caucasians (Anglophone, Francophone, and other), and then six major groupings of non-Caucasian women. Figure 10 shows the number of children that women in each group had had at various ages. For some groups, not enough women at ages 40–44 were sampled to provide a valid estimate.

Although, in general, poorer Canadian women are having fewer children, some ethnic groups with very low average incomes nonetheless have rather high fertility. For example, Indigenous and Black women in Canada report considerably higher fertility by their 30s than Caucasian women do. On the other hand, women of East Asian descent report quite low fertility by their 30s, though they mostly catch up to Caucasian women by their 40s. Caucasian Francophone women (those who identified French as “the first language they learned as a child which they still speak today”) generally report more children than Caucasian Anglophone women, though the difference is modest for those nearest the end of their childbearing years, suggesting that Caucasian Francophone women may simply have their children earlier in life.

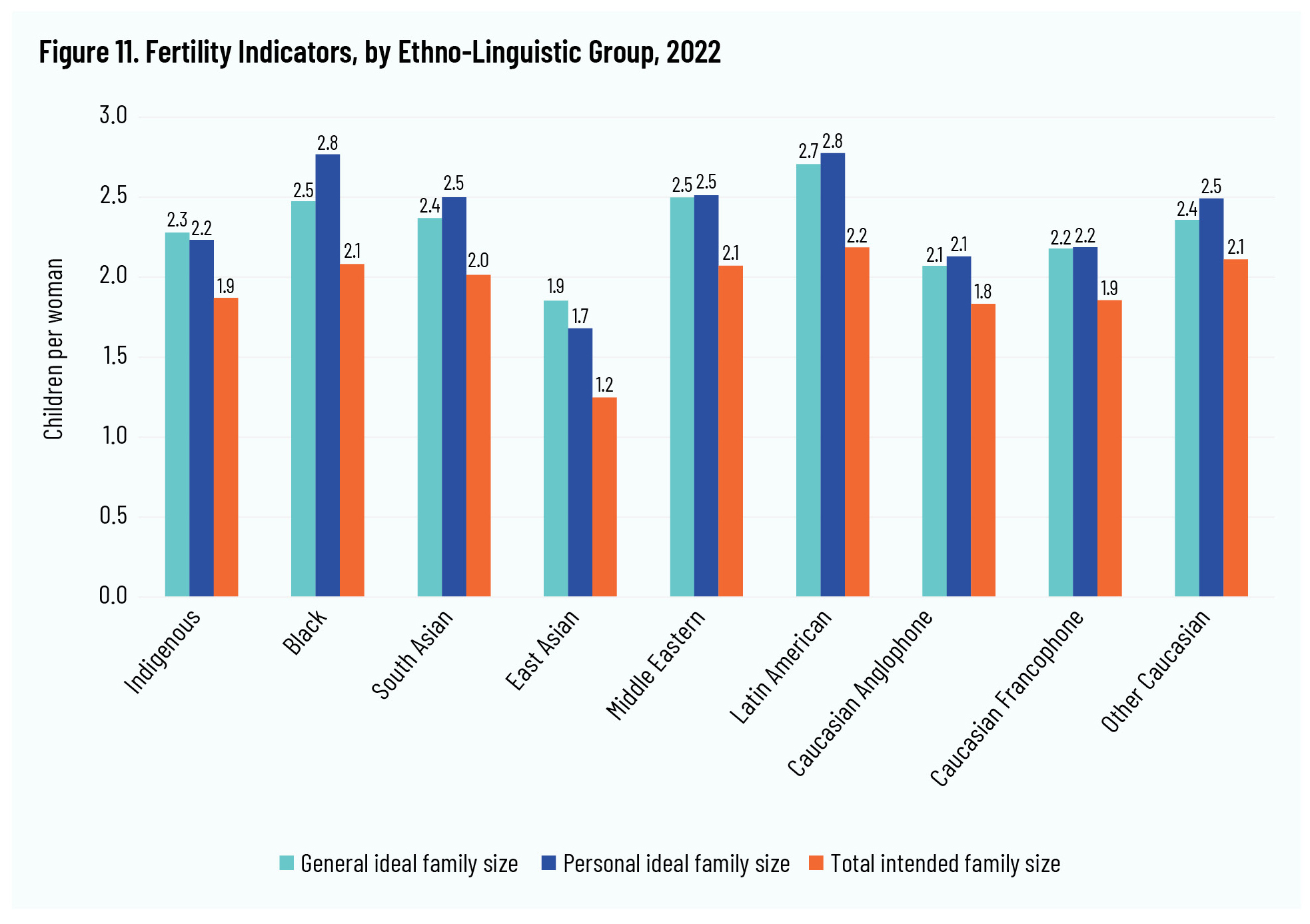

Why ethno-linguistic groups vary in their fertility is an important question for considering policy responses. Figure 11 shows that fertility indicators differ across groups.

Across all groups, total intended family size falls short of both general and personal ideal family size. Women of East Asian descent report very low fertility desires and intentions, similar to the low levels reported in China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong in recent surveys. 10 10 S. Gietel-Basten, J. Casterline, and M.K. Choe, eds., Family Demography in Asia: A Comparative Analysis of Fertility Preferences (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018). On the other hand, Black women and those of South Asian, Middle Eastern, and Latin American ethnicities report relatively high fertility preferences and intentions. High fertility among Black women in Canada, therefore, may result from these women desiring more children. But for Indigenous women, a different story emerges: in their 30s these women average 2.3 children (figure 10), yet report desiring just 2.2 (figure 11), indicating that Indigenous women may be concerned about “excess” fertility. This may seem to provide some justification for contraception promotion among Indigenous women, but it should be kept in mind that a difference of 0.1 between desires and outcomes is quite small. Small differences between fertility ideals and outcomes should not be used to justify major policies.

Factors Influencing Family Plans

In the final section of our survey, we asked women to identify any concerns, worries, or issues that may influence their family plans. They were offered a structured list of thirty-four possible items, and could also volunteer their own responses. All respondents faced an initial question about broad factors influencing family plans, with options related to finances, work-life balance, stage of life, and general social worries. Any option that a woman selected then provided her a more detailed set of options. Thus, for example, women who indicated financial concerns were then asked about specific concerns such as housing costs or childcare costs. Women who indicated time-availability issues were shown more detailed options such as maternity-leave availability and childcare access. All women were also given a chance to write in responses for issues that they were not asked about, and all write-in responses were coded into the appropriate categories. Over 1,700 women selected at least one issue, and over 800 provided a written response. Most women who did not select any issue were older and had already completed or nearly completed their childbearing. As a result, we focus our analysis on the concerns of women under the age of 30—women at an age where few face biological infertility and so could have children, but for whom various financial and other factors may make childbearing and rearing difficult.

Specifically, we assess the extent to which women who selected a specific issue (or who described that issue using their own words) have a lower likelihood of having a child in the next two years, among women who want any more children.

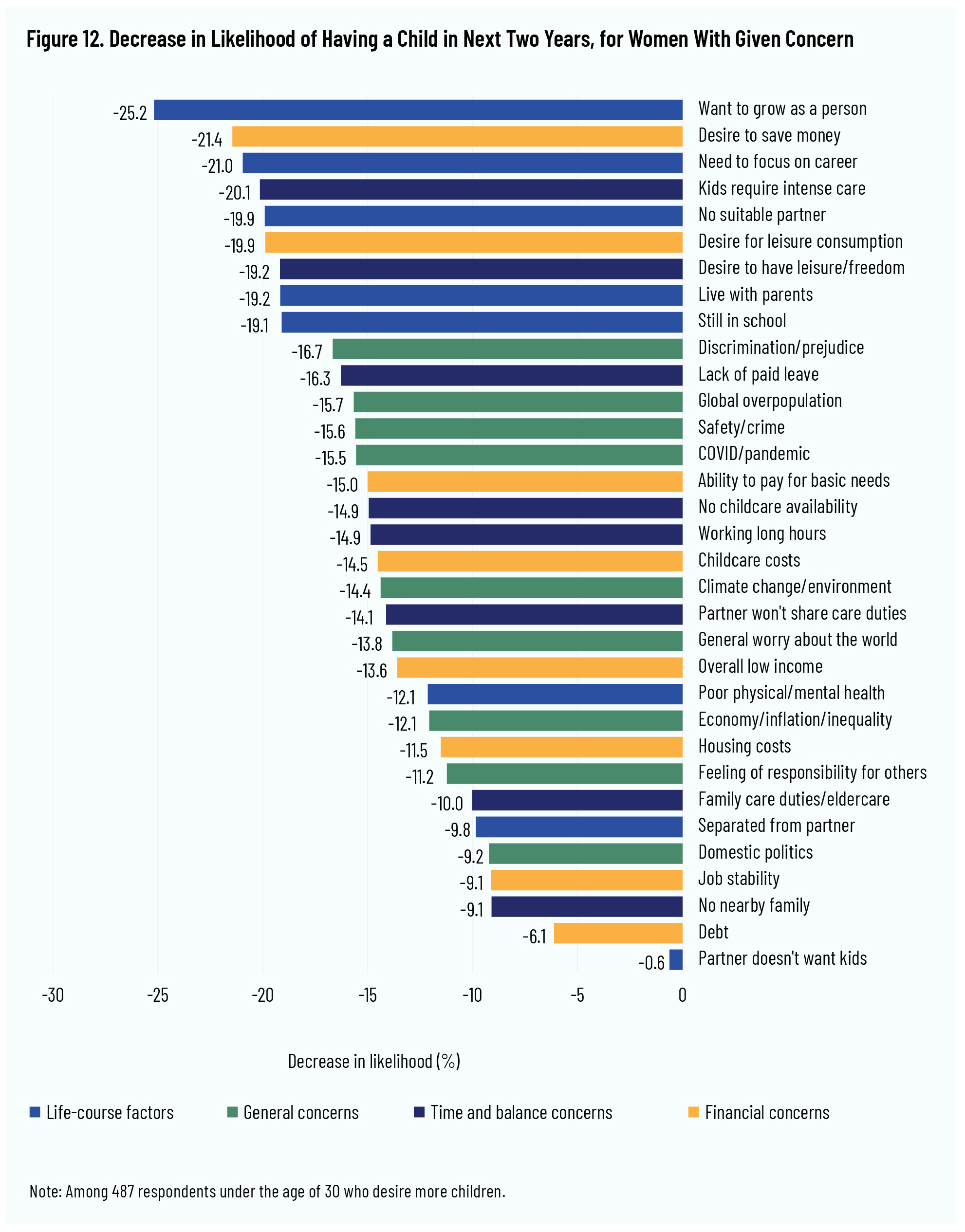

In principle, then, we assess exclusively the association between a given issue (for example, “I still live with my parents” or “Housing is just too expensive”) and self-perceived reduced likelihood of childbearing in the next two years, among women under the age of 30 who want more children. This is a fairly narrow window of analysis, but it represents a vitally important segment of the population, namely, women in the immediate process of making decisions about their fertility and family before too much is “locked in” by the passing of time. Figure 12 shows how much lower the self-rated likelihood of having a child in the next two years is for women who chose one or more options from the structured list of thirty-four possible issues, versus those who did not.

In figure 12, different concerns or worries have been colour-coded according to the four detailed menu groups that the concern appeared in. Some similar options appeared across groups. For example, women who indicated financial concerns could select the more detailed concern “It’s important to me to have money to pay for the good things in life, like travel and hobbies, and a child would make that too difficult,” a concern that we have abbreviated for length in figure 12 as “desire for leisure consumption.” Women who selected concerns relating to time and work-life balance were offered a menu of options that included “It’s important to me to maintain plenty of leisure time for myself,” which we have abbreviated as “desire to have leisure/freedom.” These are closely related concerns, and women could (and many did) select both options. But they are subtly different in that one concern focuses on financial aspects of leisure, and the other on time aspects.

The results shown represent simple differences in likelihood of having a child in the next two years, between women who do or do not have the given concern. Thus, for example, among women under the age of 30 whose ideal family size exceeds their childbearing to date, 45 percent of women indicate agreement with the statement “I’m still exploring myself and want to develop as a person before I become a parent,” which we abbreviate as “Want to grow as a person.” Among the women who expressed that concern, just 2 percent say they were likely to have a child in the next two years, versus 27 percent among women who did not report that concern. This yields a difference of 25 percent, the value shown in figure 12. The bars, then, represent how much less likely women who have a given concern are to expect a child in the near future, compared to women who do not have that concern. We focus on this indicator because near-term expectations are the strongest survey-based predictor of actual behaviour, and because virtually none of the women in this subsample reported infertility and all of the women in the subsample do desire more children.

Blue bars, representing “life-course factors” or what might be called “stage of life” concerns, generally have the largest effects for reducing likelihood of having children soon. The single most influential life-course factor was the statement “I’m still exploring myself and want to develop as a person before I become a parent.” Some may have responded in this way because they see children as a barrier to self-exploration and self-development. Others may not see the two as incompatible, but are enjoying their present lives and think that they have lots of time yet to have a family—that in the end, both goals will be achieved. Another major life-course concern is the statement “I’m just starting out in my career and need to focus on advancement first.” It is interesting that these responses are more influential than financial concerns about housing or childcare. The most influential financial worry is not some specific cost but “I need to be able to save money for my future goals, including retirement.” The desire to get to a certain place financially in life before children arrive is extremely influential for Canadian women’s family planning.

As far as concerns related to time and work-life balance, the most determinative challenge is not leave time, eldercare, childcare availability, or working hours, but rather agreement with the statement “Children simply require lots of intense care, and I don’t have time for that.” It appears that what makes women forgo desired childbearing is not childcare, leave, or working hours per se but an underlying belief that having a child is time-intensive. Work-life balance issues are, of course, real problems for families, and children do create real demands on their parents’ time. We wonder, however, if some respondents believe that children necessarily mandate a very high intensity of care. Prior research has found that people in Western countries, particularly those of higher socioeconomic status, are adopting ever-more-intense parenting norms, resulting in the total time burden of unpaid domestic work actually rising toward levels seen before modern electrical appliances were invented. 11 11 J.R. Pepin, L.C. Sayer, and L.M. Casper, “Marital Status and Mothers’ Time Use: Childcare, Housework, Leisure, and Sleep,” Demography 55, no. 1 (2018): 107–33; E.C. Rubiano-Matulevich, and M. Viollaz, “Gender Differences in Time Use: Allocating Time Between the Market and the Household,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8981, 2019, 1–51, https://ssrn.com/abstract=3437824; G.M. Dotti Sani and J. Treas, “Educational Gradients in Parents’ Child-Care Time Across Countries, 1965–2012,” Journal of Marriage and Family 78 (2016): 1083–96, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12305; J. García-Manglano, N. Nollenberger, and A. Sevilla Sanz, “Gender, Time-Use, and Fertility Recovery in Industrialized Countries,” IZA Discussion Paper No. 8613, 2014, 1–19, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2529322. In reality, although many people in the Western world believe that intensiveness is the sine qua non of parenting, actual hours spent on childcare vary enormously both within and across countries. 12 12 Pepin, Sayer, and Casper, “Marital Status,” 107–33; Rubiano-Matulevich and Viollaz, “Gender Differences,” 1–51; Dotti Sani and Treas, “Educational Gradients,” 1965–2012; García-Manglano, Nollenberger, and Sevilla Sanz, “Gender, Time-Use,” 1–19. If intensive forms of parenting deepen their hold on Canadian culture, fertility will suffer as parents feel more stressed by the ever-increasing burden of parenting tasks. People who believe that good parenting requires (rather than simply may include) extended breastfeeding, numerous extracurriculars, carefully curated cognitive-developmental experiences, and large amounts of time spent to strengthen parent-child bonds will naturally feel more overwhelmed by parenting and thus more daunted by childbearing.

Going down the list of factors influencing near-term family plans, most of the highly rated reasons are related to intensive parenting or to a second important concept this report introduces, that of “capstone kids.” An extensive literature has arisen identifying a shift in marriage norms in the Western world, with marriage no longer construed as a foundation for building an adult life together but instead as a capstone that crowns a successful life already having been achieved. 13 13 A.J. Cherlin, “Degrees of Change: An Assessment of the Deinstitutionalization of Marriage Thesis,” Journal of Marriage and Family 82, no. 1 (2020): 62–80, https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12605; J.A. Holland, “Love, Marriage, Then the Baby Carriage? Marriage Timing and Childbearing in Sweden,” Demographic Research 29, no. 11 (2013): 275–306, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26348155. This survey uncovers evidence that children may be beginning to acquire the same status.

Responses such as “It’s important to me to have money to pay for the good things in life, like travel and hobbies, and a child would make that too difficult” had more influence than housing costs or low-income status in this cohort. Likewise, “It’s important to me to maintain plenty of leisure time for myself” is more influential than reporting that a partner is unwilling to share childcare. Where children are viewed as incompatible with one’s current pursuit of self-development, leisure time, and spending, or as an equally important life goal but one that can be pursued later, some women may find that in the end they do not have the number of children that they desired. Further research would help to answer this important question: For women close to the end of their reproductive years who do not have as many children as they desired, to what do they attribute that gap? Answers to this question would be of great value for determining which policy levers might best help to increase fertility in Canada and help women achieve the lives that they want for themselves.

Of course, other factors also matter for fertility. Women in this cohort who are worried about COVID-19, or the economy, climate change, discrimination against potential children, or their finances, do correspondingly curtail their family plans. They just do so less than women who espouse the “capstone kids” or “intensive parenting” ideas.

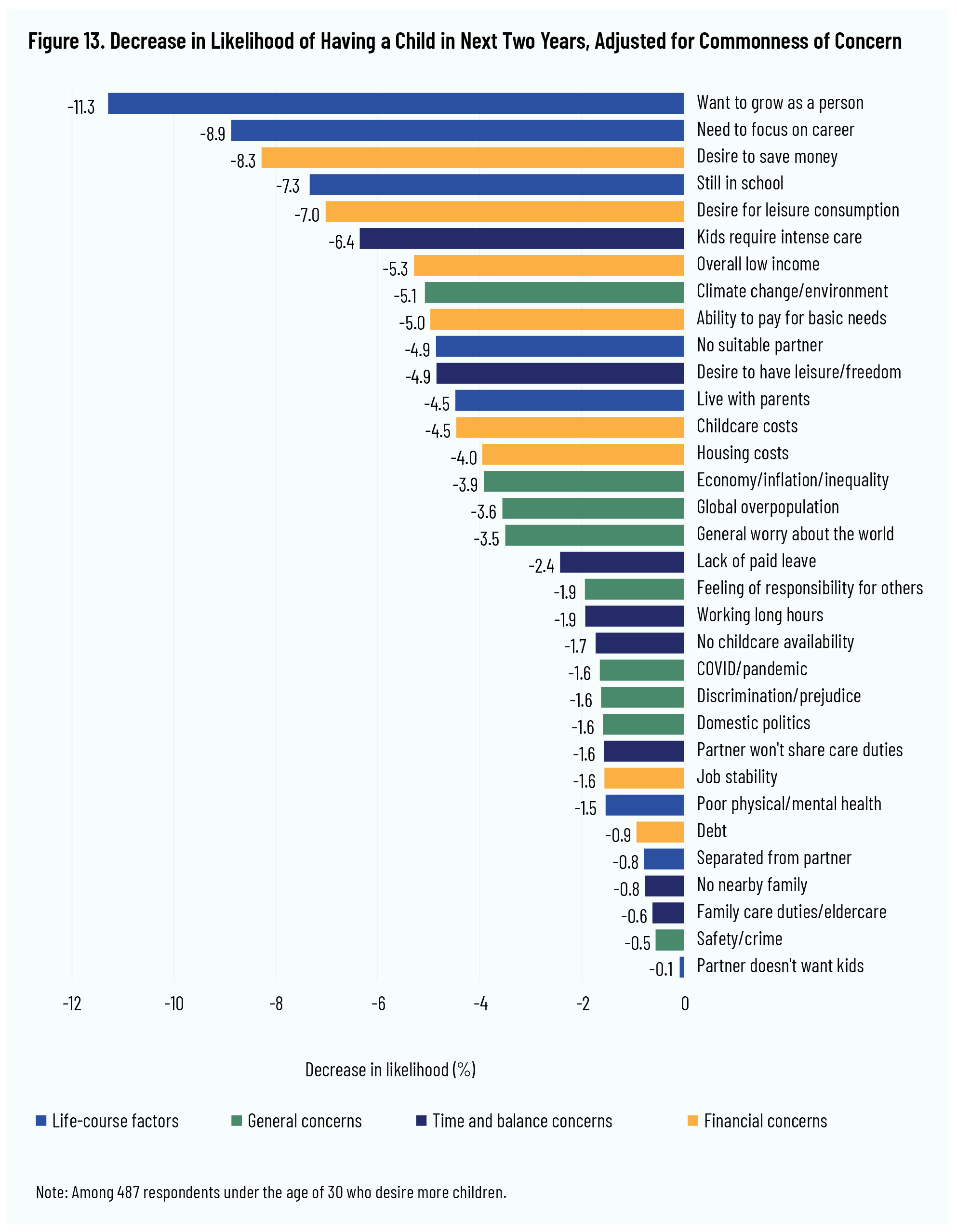

And of course, not all worries are equally common. About 45 percent of women in this cohort agree that “I’m still exploring myself and want to develop as a person before I become a parent,” while just 4 percent say that worries about safety or crime influence their family planning. Figure 13 presents the same data as figure 12 but reduces each likelihood effect by the share of respondents who did not express a given worry or concern. This shows which concerns or worries are both severe and common, and thus key drivers of “missing” births.

Life-course factors predominate in figure 13: they tend to be common issues and to have large effects. Self-exploration, career advancement, and educational completion all supply women in this cohort with strong reasons to postpone childbearing. So does desire for saving and leisure consumption. Overall, this figure reinforces the conclusions of figure 12 in its broad outlines. That said, there are some concerns that, while not individually in the top ranks of influence in figure 12, are sufficiently widespread that their overall social effect is large. Housing costs, worries about the economy, having wages barely high enough to meet their existing needs, and worries about climate change all fall into this group of moderately influential but widely shared concerns. These concerns may not be most women’s top concern, but operate in the background for so many women that they remain socially important. On the other hand, some concerns are very influential on the women who have them but are not widely shared, and so are not as highly ranked in figure 13 as in figure 12. The COVID-19 pandemic, worries about personal safety or crime or about facing discrimination or prejudice, and insufficient leave time from work are all examples of this type of more niche concern. These are issues that are influential in the decision-making of the women who have them, but they are not shared by larger swathes of Canadian women.

In additional statistical tests not presented here, we confirmed that these lists were approximately similar if instead of analyzing likelihood of children in the next two years we assessed effects on intentions to ever have any (or more) children. This analytic change has little effect on overall conclusions. It is notable to mention here as well that relatively few respondents at any age selected infertility or poor health as reasons to not have any (or more) children, and only one of 2,700 respondents wrote in a concern about availability of in vitro fertilization (IVF). Thus, we do not find evidence that increasing support for IVF or other similar supports would do very much to address the concerns that women report, which mostly relate to social, cultural, and economic factors.

Conclusion

Canadian fertility rates are low. All too often, low fertility is presented as both a choice and a success for women. Our research indicates, however, that fertility is much lower than Canadian women say they desire for themselves. These family desires are not being thwarted because Canadian women are making great strides in other areas of their life, as recent public commentary infers. 14 14 S. Paikin, “Is COVID Causing Canada’s Birth Rate to Fall?,” The Agenda with Steve Paikin, February 3, 2022, https://www.tvo.org/video/is-covid-causing-canadas-birth-rate-to-fall. Instead, it appears that the thwarting arises due to the sequence in which Canadian women pursue their goals. When having children is viewed as hampering the pursuit of one’s career, self-development, or financial goals, as a capstone to be achieved once these other goals have been reached, women’s wishes for children, or for the number of children they consider ideal, may be deferred to the point of permanence. We are concerned that a combination of intensive-parenting norms and “capstone childbearing” means that only women with considerable financial resources at their disposal feel confident about pursuing larger families. As a result, and perhaps uniquely among industrialized societies, Canadian fertility outcomes and intentions are highest among the wealthiest women.

To the extent that policymakers care about what women want for their own lives, they would do well to shift away from the pervasive mythology that women always desire to prevent pregnancy or have fewer children, and consider addressing the concerns that actually put the brakes on women’s family goals. Some of these may be amenable to conventional policy reforms: for example, by finding ways to help people complete higher education and get a stable job faster (as with Quebec’s CÉGEP program), addressing high housing costs by expanding housing supply, and encouraging economic growth, which can boost salaries.

Other issues are much harder to address. Would-be parents need support and encouragement that they have what it takes to raise children. Initiatives aimed at parents, whether by government or civil society, should focus less on giving parents a list of items they should do and focus more on messages of empowerment and competence. Public health and education initiatives should take care to avoid promoting monolithic, high-intensity models of parenting as normative. Because the government interacts with parents at numerous levels throughout a child’s life, it is vital to consider what messages about parenting are being passed on. Any message besides “Parenting is something virtually every adult is able to do well” is a discouragement.

Initiatives aimed at parents, whether by government or civil society, should focus less on giving parents a list of items they should do and focus more on messages of empowerment and competence.

When it comes to capstone children, it isn’t clear what policymakers can do. Social norms that present children as barriers to achievement in other areas of life, rather than as adventures in meaning-making for the parents themselves, will discourage fertility regardless of what policy measures are put in place. Unless Canadian women see children as part of the process of self-development and discovery, rather than a prize for successful completion of it, the capstone model will continue to weigh on many women’s ability to achieve their family aspirations.

Further research should explore parenting norms and the capstone model of childbearing further, to better understand these belief sets. But research should also focus on more tractable issues such as housing costs or family policy, including child care. To that end, we hope to produce further reports based on this survey data, covering household-budget issues and regional differences in Canadian fertility.

References

Bumpass, L., and C.F. Westoff. “The Prediction of Completed Fertility.” Demography 6, no. 4 (1969): 445–54.

Chei, C.L., J. M.L. Lee, S. Ma, and R. Malhotra. “Happy Older People Live Longer.” Age and Ageing 47, no. 6 (2018): 860–66. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy128.

Cherlin, A. J. “Degrees of Change: An Assessment of the Deinstitutionalization of Marriage Thesis.” Journal of Marriage and Family 82, no. 1 (2020): 62–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12605.

Cheung, F., and R.E. Lucas. “Assessing the Validity of Single-Item Life Satisfaction Measures: Results From Three Large Samples.” Quality of Life Research 23, no. 10 (2014): 2809–18. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11136-014-0726-4.

Cleland, J., K. Machiyama, and J.B. Casterline. “Fertility Preferences and Subsequent Childbearing in Africa and Asia: A Synthesis of Evidence From Longitudinal Studies in 28 Populations.” Journal of Population Studies 74, no. 1 (March 2020): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2019.1672880.

Coombs, L.C. “Reproductive Goals and Achieved Fertility: A Fifteen-Year Perspective.” Demography 16, no. 4 (1979): 523–34.

Cross, P., and P.J. Mitchell. “The Marriage Gap Between Rich and Poor Canadians.” Institute of Marriage and Family Canada, February 2014. https://www.cardus.ca/assets/data/files/IMFC/TheMarriageGapBetweenRichandPoorCanadians.pdf.

Dotti Sani, G.M., and J. Treas. “Educational Gradients in Parents’ Child-Care Time Across Countries, 1965–2012.” Journal of Marriage and Family 78 (2016): 1083–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12305.

Fergusson, D.M., G.F.H. McLeod, L.J. Horwood, N.R. Swain, S. Chapple, and R. Poulton. “Life Satisfaction and Mental Health Problems (18 to 35 years).” Psychological Medicine 45, no. 11 (2015): 2427–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291715000422.

Fostik, A., and N. Galbraith. “Changes in Fertility Intentions in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Statistics Canada, December 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2021001/article/00041-eng.htm.

García-Manglano, J., N. Nollenberger, and A. Sevilla Sanz. “Gender, Time-Use, and Fertility Recovery in Industrialized Countries.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 8613, 2014, 1–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2529322.

Gietel-Basten, S., J. Casterline, and M.K. Choe, eds. Family Demography in Asia: A Comparative Analysis of Fertility Preferences. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2018.

Holland, J.A. “Love, Marriage, Then the Baby Carriage? Marriage Timing and Childbearing in Sweden.” Demographic Research 29, no. 11 (2013): 275–306. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26348155.

Luhmann, M., R.E. Lucas, M. Eid, and E. Diener. “The Prospective Effect of Life Satisfaction on Life Events.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 4, no. 1 (2013): 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550612440105.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Fertility Rates.” 2023. https://data.oecd.org/pop/fertility-rates.htm.

Paikin, S. “Is COVID Causing Canada’s Birth Rate to Fall?” The Agenda with Steve Paikin, February 3, 2022. https://www.tvo.org/video/is-covid-causing-canadas-birth-rate-to-fall.

Pepin, J.R., L.C. Sayer, and L.M. Casper. “Marital Status and Mothers’ Time Use: Childcare, Housework, Leisure, and Sleep.” Demography 55, no. 1 (2018): 107–33.

Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights. “Forced and Coerced Sterilization of Persons in Canada.” June 2021. https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/432/RIDR/reports/2021-06-03_ForcedSterilization_E.pdf.

Rubiano-Matulevich, E.C., and M. Viollaz. “Gender Differences in Time Use: Allocating Time Between the Market and the Household.” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8981, 2019, 1–51. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3437824.