The 2018 Cardus Education Survey (CES) marks nearly a decade’s worth of research into the effects of various school sectors on the academic, social, religious, and civic development of graduates in the United States. The Survey is now considered one of the most significant measures of nongovernment school outcomes. CES reports capture the views from a representative sample of 1,500 randomly selected American high school graduates ages twenty-four to thirty-nine who were asked to complete a thirty-five to forty-five-minute survey. The assessment comes at an important time—far enough away for these graduates to have had experiences in other educational institutions, in family and relationships, and in the workplace, and yet close enough to allow for some maturity, reflection, and recollection. The CES instrument includes a large number of controls for many factors in graduate development, such as parental education, religion, and income, in order to isolate a school sector’s particular impact (“the schooling effect”). 1 1 The 2018 CES respondents include 904 graduates who primarily attended public high school, 83 respondents who primarily attended non-religious private school, 303 graduates of a Catholic high school, 136 graduates of an evangelical Protestant school, and 124 who were homeschooled. In order to isolate the school effect for each of these sectors, the analysis includes a large number of control variables for basic demographics (gender, race and ethnicity, age and region of residence), family structure (not living with each biological parent for at least sixteen years, parents divorced or separated, not growing up with two biological parents), parent variables (educational level of mother and father figure, whether parents pushed the respondent academically, the extent to which the respondent felt close to each parent figure), and the religious tradition of parents when the respondent was growing up (mother or father was Catholic, conservative Protestant, conservative or traditional Catholic). A control was also included for the number of years a private school graduate spent in public school. Despite our efforts to construct a plausible control group, because families who send their children to religious schools or non-religious independent schools make a choice, they may differ from those who do not exercise school choice in unobservable ways that are therefore not accounted for in our study. Despite this, the CES use of an extensive survey instrument, together with its comprehensive application of control variables and resulting patterns of outcomes, assures us with some confidence of the accuracy of our school sectoral outcomes. Five smaller reports summarize the results of the 2018 survey. They focus on particular outcomes and themes of interest, including the following: (1) education and career pathways; (2) faith and spirituality; (3) civic, political, and community involvement and engagement; (4) social ties and relationships; and (5) perceptions of high school.

This CES report provides a glimpse into the strength and diversity of the social ties held by American graduates and the influence of the various school sectors on these social outcomes. Loneliness and social isolation are pervasive in American life today. In Bowling Alone (2000), a landmark study of America’s dwindling social capital, sociologist Robert Putnam found that more and more Americans inhabit an impoverished life due to the breakdown of once-strong communal ties. Not only did Putnam’s research find that people were involved in fewer organizations and institutions, but he also found that they had weaker social ties to their friends, co-workers, and even immediate family members. In the years since Putnam’s work, studies and reports have attempted to measure and analyze the fraying of the American social fabric and the consequent concerns about public health and civic viability for a democratic republic. The pervasiveness of this modern social ill has begun to infiltrate the policy domain. Perhaps most notably, the United Kingdom has recently appointed a minister for loneliness. In Canada, the National Seniors Council, established to provide advice for the federal government, has focused on the issue of social isolation in its most recent 2014 and 2017 reports.

Social cohesion matters for individual wellness and health as well as for the public good; there are individual and communal repercussions, for good or ill, of the strength of social connectedness. What are the factors that place individuals on a path toward social health, or conversely, toward social disconnection? According to Putnam’s work, social ties can be significant for their “bonding” characteristics, as well as for their ability to help “bridge” across traditional social divides. It is important to understand the nature of these networks in order to better understand their function within society. The following report uses similar categories to report on the 2018 CES. Survey questions sought to gain a deeper understanding of the respondents’ four closest ties in order to draw a number of conclusions. The survey then asks respondents for broader connections in order to draw further inferences about the influence of school sector on the capacity to form ties across social boundaries. By analyzing both the graduates’ closest ties as well as broader connections, we are able to draw certain inferences regarding the proximity of the graduate to positions of power and connections to more diverse networks.

Bonding: Close Ties

The 2018 CES US asked extensive questions about social relationships, including the characteristics of younger Americans’ closest ties. Respondents were asked to provide the first name or initials of their four closest friends or social ties, as well as how these friends were connected to the respondent, the extent and type of interaction, the race and ethnicity of each friend, and a number of other questions designed to probe more deeply into the nature of these relationships.

Number and Strength of Close Ties

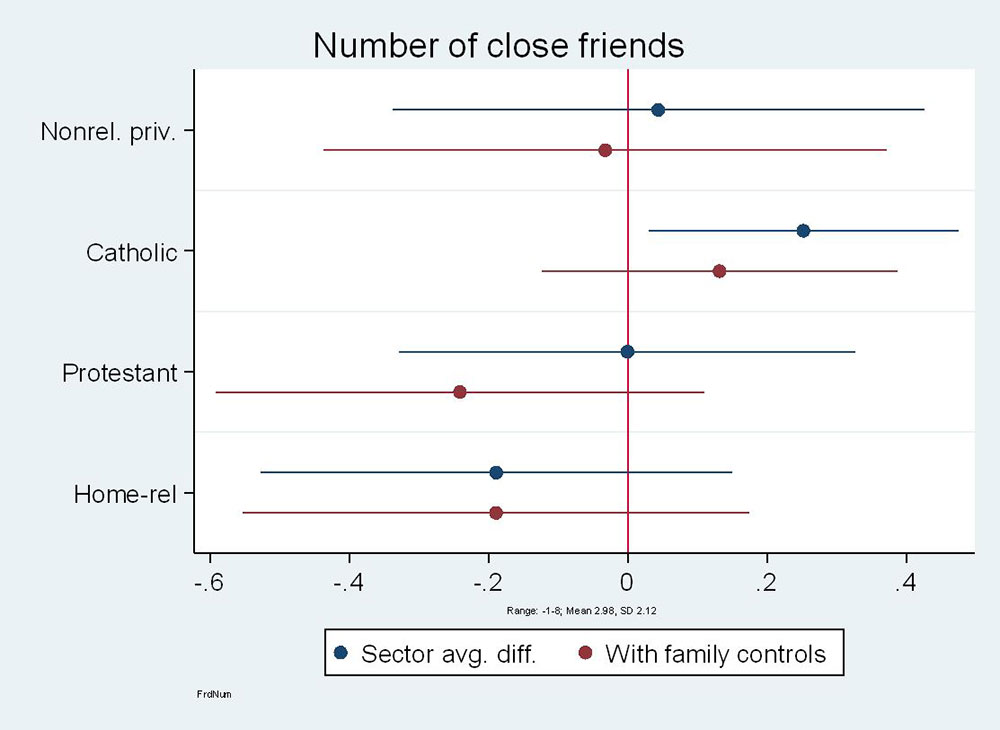

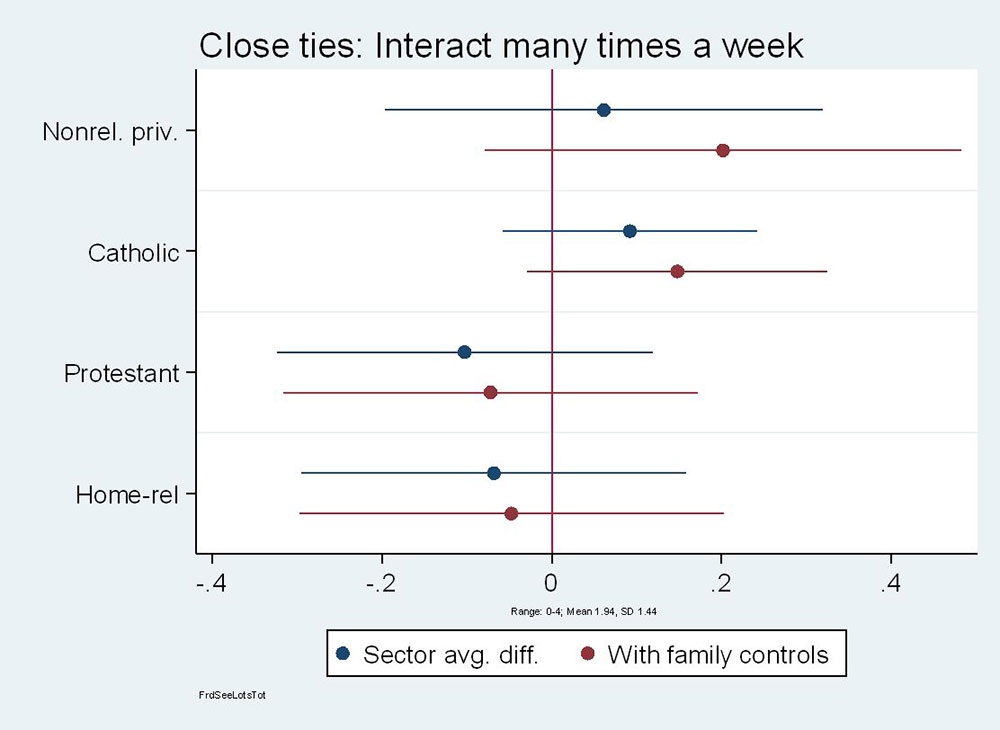

The 2018 CES data indicates that a graduate’s total number of close friends, as well as the strength of these close-tie friendships, does not vary by school sector. Catholic-school graduates report a slightly higher number of close ties, but this is not statistically significant after accounting for family background. Further, the frequency of these close-tie interactions and the willingness to confide in the close friend does not vary according to school sector, with one exception being, again, the Catholic graduate. These graduates are more likely to have at least one friend with whom they interact many times a week. Religious homeschool graduates are not distinctive in the nature of interactions with friends, and non-religious private school graduates are similar to catholic graduates, but this effect is only marginally significant. Overall then, the school-sector difference in the intensity and trust in social ties does not vary substantially, with the possible (but inconsistent) exception of Catholic school graduates.

Relationships to Family and Religion

The 2018 CES also attempts to better understand the nature of these close ties by assessing to what extent these bonding relationships can be explained by family ties and religious similarities. After asking respondents to list closest ties, the 2018 survey asks respondents to indicate whether any close ties are family members, in this way gaining a deeper understanding into the nature of these relationships. Perhaps the strongest finding here is that religious homeschool graduates were much more likely—indeed one and a half times more likely—to include an immediate family member as one of their four closest ties than were public school graduates. Graduates from all other school sectors were neither more nor less likely to name family members than their peers who went to a public school. Interestingly, when considering parents alone (as opposed to siblings or grandparents) as close ties, homeschool graduates are about 1.8 times more likely to include a parent as a close tie than are public school graduates. Catholic school graduates are also more likely than public school graduates to mention a parent as a close tie.

In terms of close ties to others who share a similar faith, all religious school graduates report having more friends who share their religion and who attend religious services, suggesting that perhaps religious family background is more correlated to these outcomes than is school sector, though there are interesting differences among the different school sectors. The number of close-tie relationships to others of the same faith is highest for Protestant and religious homeschool graduates, but is substantial for Catholic school graduates as well. Interestingly, the religious homeschooling effect is strongly positive for the number of close ties who hold the same religion, but not statistically significant as a predictor of whether the respondent has at least one close tie who shares their religion.

Similarly, Protestant and religious homeschool graduates are quite similar in their likelihood of having a close friend who attends their congregation—both are more than one and a half times more likely to mention a congregational friend than is a public school graduate. Interestingly, Catholic school graduates are statistically no more likely to mention a congregational friend among their close ties, despite having a larger proportion of overall friends who are from their congregation.

As we might expect, Protestant and religious homeschool graduates are much more likely than public school graduates to say that one or more of their close ties is an evangelical or born-again Christian. Catholic school graduates are less likely to have a born-again friend. Catholic school graduates are also more likely than are public school graduates, though less likely than Protestant and religious homeschool graduates, to have at least one or more than one born-again Christian friend. Interestingly, the Catholic-school-sector effect seems to counter the (somewhat negative) family effect for this particular outcome.

Relationship to Spouse

The 2018 CES survey also asks graduates about the nature of the relationship with their spouse. Non-religious private school graduates are more likely to have a spouse with a university degree and who attended the same university as public school graduates. Interestingly, these graduates are not more or less likely than public school graduates to report that their spouse is religious or nonreligious, perhaps because religion is less salient for marital decisions among this group.

Catholic school graduates also tend to have spouses with a university degree, though this is only marginally significant after accounting for family background. These graduates are also more likely to have a spouse of the same religion and the same religious beliefs. Interestingly, while Catholic school graduates are more likely to share religious talk with their spouses and to have spouses who attend religious services than are public school graduates, they are also significantly more likely to be married to an atheist, though this effect is only marginally significant after including controls for family background.

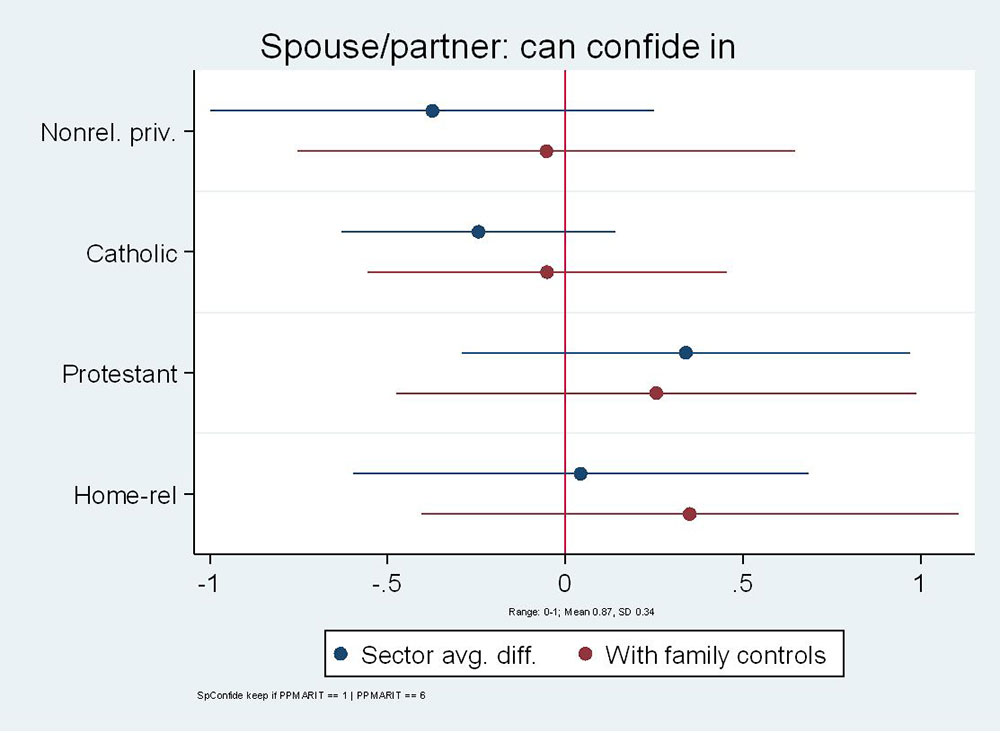

Protestant school graduates tend not to have met their spouse in high school. Their spouse is equally likely to have a university or advanced degree as public school graduates’ spouses, though they are much more likely to have a spouse that shares the same religious beliefs and/or attends religious services. These spouses are also much more likely to attend a congregation, and the couple is much more likely to talk about religion as a married couple than are public school graduates and their spouses. They are also more likely to be born-again Christians, and, not surprisingly, are least likely to identify as atheist. Protestant school graduates are also more likely than public school graduates to be married to someone who shares their race and ethnicity. Interestingly, however, religious homeschool graduates are just as likely to be in an interracial marriage as are public school graduates. Protestant graduates are the most likely to report having a spouse or partner that they can confide in.

Bridging Capital: Interaction Across Social Divides

Bonding social capital—that which binds people together and offers a feeling of belonging—is very necessary to both individual and societal well-being. These small communities of family and faith provide the necessary conditions for human beings to flourish and to learn how to engage more broadly. But, as democratic theorists point out, in order for these groups of individuals to feel a sense of belonging to broader society and to want to contribute to the broader common good, it is important that these spaces and relationships also “bridge” across these close ties to “others” who may be quite different from oneself. These connections are integral to learning how to live together and to share a sense of common humanity despite the various divides. We now turn to the other side of the coin—an exploration of the diversity and breadth of these social ties and of the role of the school sector in these social outcomes.

Close Ties and Bridging Across the Social Divides

In seeking to better understand whether relationships are bridging across social divides, the 2018 CES asks a series of questions about the nature of close ties and a series of questions about the graduates’ wider networks. One way that the 2018 CES tries to better understand interaction across social divides is to ask whether religious school graduates have at least one friend within their close ties who is an atheist. Not surprisingly, non-religious private school graduates are more likely to have at least one friend who is an atheist than public school graduates, though this is not statistically significant after accounting for their family background. Interestingly, however, Catholic school graduates are also more likely—one and a half times more likely in fact—to be closely associated with an atheist than public school graduates. Protestant and religious homeschool graduates are much less likely to be closely tied to an atheist, indeed about half as likely to have at least one close tie who is an atheist.

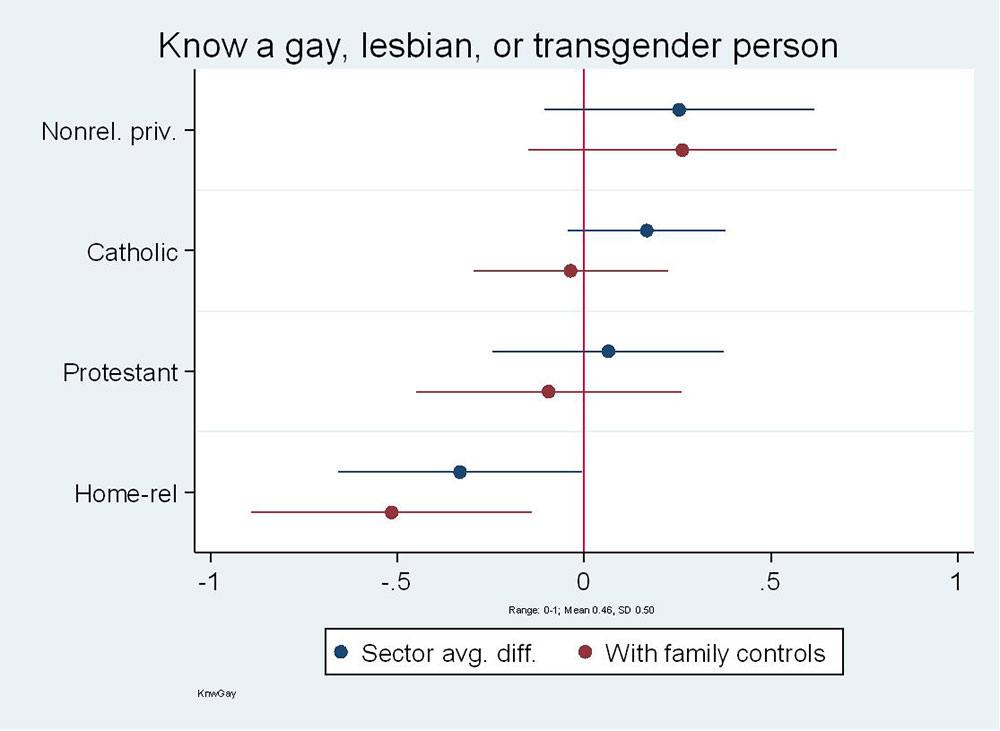

These similar patterns are reflected to some extent in the likelihood of having friends who are gay or lesbian. Catholic school graduates are more likely than public school graduates to have at least one gay or lesbian friend, though this is accounted for by family differences and not school sector. Protestant school graduates, however, are about half as likely as public school graduates to have at least one gay or lesbian close tie.

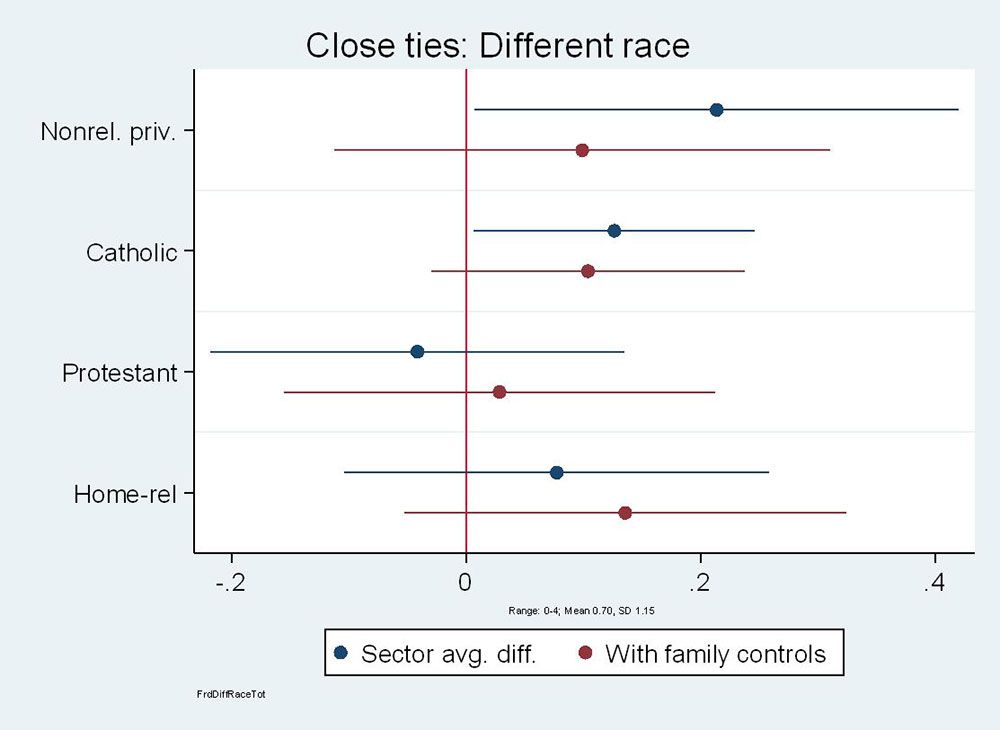

Another social difference of particular interest is the extent to which close ties reflect broader patterns of racial and ethnic segregation. Our findings reveal that Catholic school graduates are more likely than public school graduates to have at least one friend of a different race or ethnicity, and to have a greater proportion of friends of a different race and ethnicity. The other private school sectors have wide variation in the likelihood of having a close tie whose race and ethnicity is different from their own. Interestingly, there is no difference between Protestant and religious homeschool graduates, and public school graduates, in the racial and ethnic diversity of their friends.

Looking more deeply into the nature of these diverse friendships, Catholic school graduates are more likely to have an African American close tie and much more likely to have a Hispanic close tie than are public school graduates. In general, non-religious private school graduates are not significantly different from public school graduates on the race and ethnic measures of their friendships. They are much more likely to have an Asian friend, though this effect is only marginally significant after adjusting for family background of respondents. The non-religious private school graduates are also more likely than public school graduates to have an Indigenous friend.

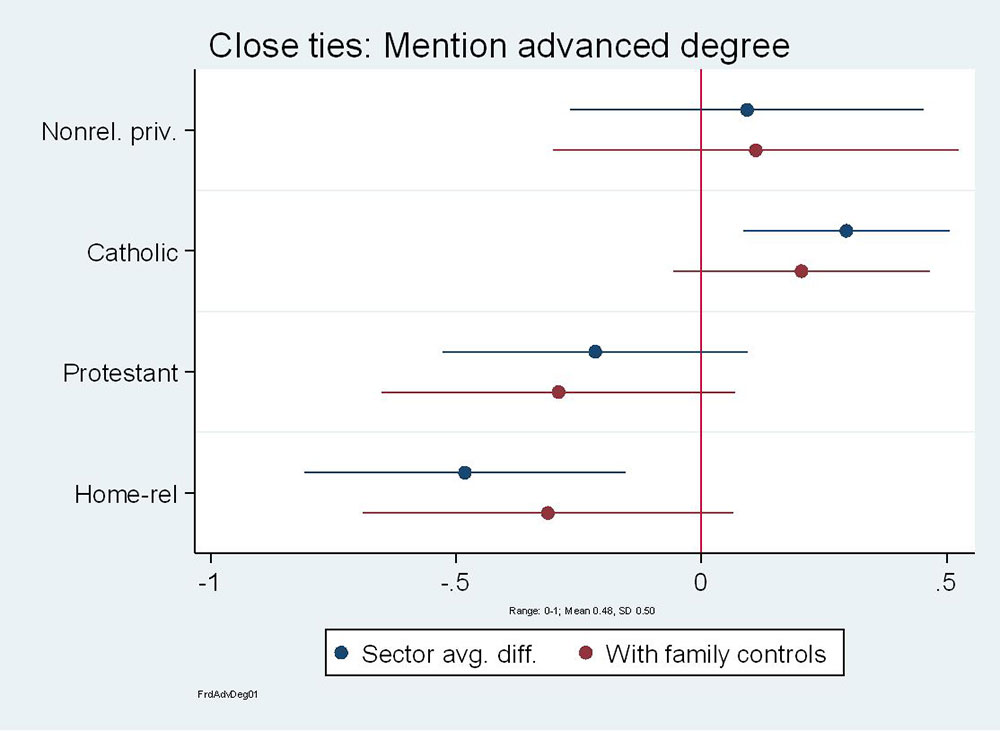

Another way of understanding interactions across social divides is to look at whether close ties include those with university and graduate degrees. Non-religious private and Catholic school graduates are more likely than public school graduates to have a higher proportion of friends with university degrees. Religious homeschool graduates are significantly lower than public school graduates in terms of the average number of friends with a university degree. These measures are also used to determine someone’s position in relation to power and influence within society, especially when looking at whether one’s close ties have advanced degree (beyond a BA/BS). Here the schoolsector differences are less clear. Catholic school graduates are slightly more likely than public school graduates to have at least one friend with an advanced degree, but this is only marginally significant; and religious homeschool graduates are less likely to have at least one friend with an advanced degree.

When respondents were asked instead about the proportion of friends who have an advanced degree, the findings reveal that non-religious private school graduates are much higher on this measure— about .3 additional “friends” with an advanced degree—while Protestant school graduates trend lower on this measure when compared to public school graduates. Religious homeschool graduates are noticeably lower on this measure; indeed, they have .5 less friends with advanced degrees as compared to public school graduates.

The 2018 CES also asks how the mention of high school and college friends among close ties differ across school sectors. For instance, do some sectors have more ties to high school friends while other school sectors have more ties to college friends? Data results indicate that non-religious private school graduates appear much less likely to mention a high school classmate than do public school graduates, though this is only marginally significant. Having at least one close tie from university is significantly more likely for Catholic school graduates than public school graduates. Protestant school graduates are also higher on this score, but this is accounted for by family background rather than by school sector. The findings vary when considering the total number of close ties that attended the respondent’s college or university. Non-religious private school graduates are more likely than public school graduates to have a higher proportion of close ties from their university. Catholic school graduates are also more likely on these measures, but this is only marginally significant. Overall, all school sectors, other than non-religious private school graduates, seem to socialize with peers from secondary school and university to the same degree as public school graduates.

Beyond Close Ties and Bridging Across Social Divides

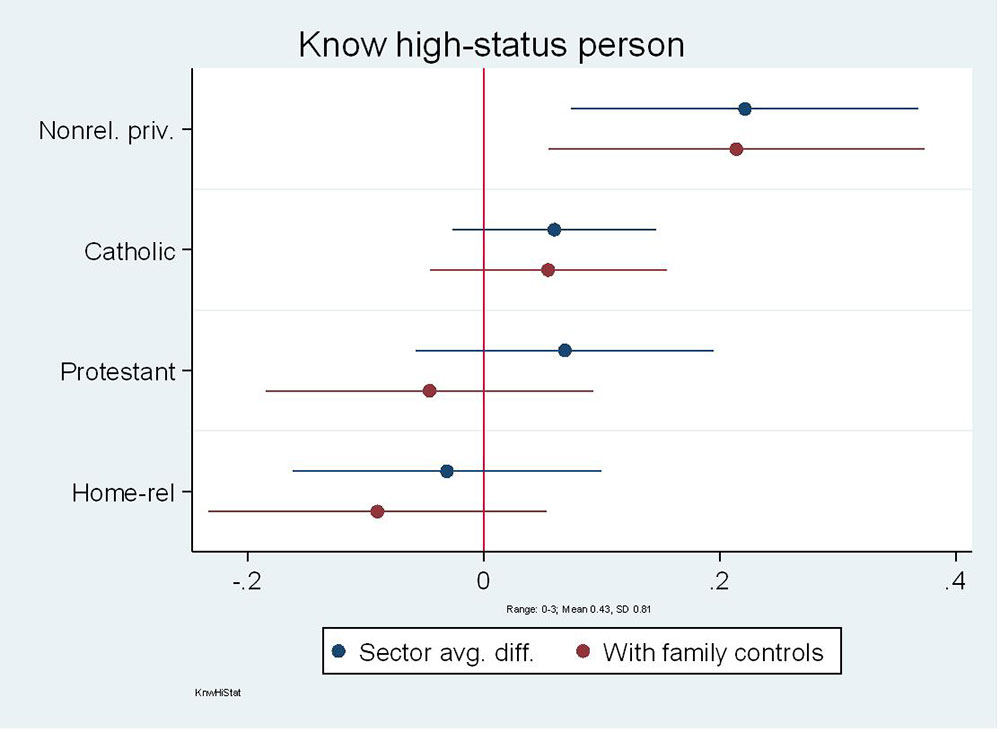

A second set of questions on the 2018 CES asked respondents to consider social ties beyond their four closest ties. The purpose of such questions is to assess the proximity of graduates to those in positions of power or influence.

Interestingly, non-religious private school graduates are much more likely—in fact, more than twice as likely—to know someone who is an elected public official than are public school graduates. Non-religious private school graduates are also more likely to know a corporate executive and much more likely to say that they know a community leader. When considering the likelihood of knowing someone in any of these three “high-status” positions, non-religious private school graduates know more people on average in these positions than do public school graduates, reflecting the fact that they are more closely connected to those in positions of power than are public school graduates. In raw percentage terms, about 34 percent of non-religious private school graduates report knowing a high-status person, while 26 percent of public school graduates report the same.

Catholic school graduates are also more likely to know an elected public official or a corporate official than are public school graduates, though this school-sector effect is not nearly as strong as the nonreligious private school effect. Interestingly, there is no Catholic-school-sector effect on the likelihood of knowing a community leader.

Protestant school graduates are less likely to know an elected public official than public school graduates, but there is no difference between Protestant and public school graduates on the likelihood of knowing a corporate executive. The likelihood of knowing a community leader is also nearly identical between these two groups. All told, Protestant school graduates are somewhat more likely to know a high-status person than are public school graduates, but this is due to family background rather than school sector.

Religious homeschool graduates are less likely to know a corporate executive than public school graduates, though this is only marginally significant. The other religious homeschooler outcomes are not significantly different from those of public school graduates.

Moving to ties across social differences, we find that non-religious private school graduates and Catholic school graduates are somewhat more likely to know a person who is atheist, gay, or lesbian than public school graduates. Protestant school graduates are less likely than Catholic and nonreligious private school graduates to know someone who identifies as atheist, gay, or lesbian, but just as likely as public school graduates to know someone who is gay or lesbian. Religious homeschool graduates are less likely to know an atheist or someone who is gay or lesbian.

Conclusion

In an era of declining trust and rising loneliness, 2018 CES findings are particularly salient, though they are difficult to fit into a single grand narrative. Nevertheless, a number of themes emerge. Both religious and non-religious school graduates have diverse social ties. More generally, non-religious private and Catholic school graduates are most likely to have relationships with a diverse group of people. Protestant school graduates are less likely to connect to some minority groups, but are equally as likely as public school graduates to have ties across racial and ethnic differences.

The relation between school sector and social stratification is another important finding. Nonreligious private school graduates tend to be connected to more highly educated and higher-status people. Catholic school graduates trend in this direction, though the findings are less strong and consistent. Protestant and religious homeschool graduates mirror public school graduates in terms of social stratification. Though, one notable finding is the less strong connections of Protestant school graduates to elected public officials, which contrasts somewhat with findings that this group has strong connections to corporate executives. These patterns may reflect certain views and values regarding the levers of change or control, but they also have important implications for citizenship and political engagement.

American society is suffering from a decline of social capital. The key challenge for all school sectors is the cultivation of graduates who are capable of maintaining deep and meaningful connections while also being able to engage within a pluralist society. The recent round of CES data suggests that religious homeschool graduates may have closer connections with family while Catholic school graduates seem to have a higher number of close ties. In an era of rising social isolation, depression, and anxiety, the importance of these findings cannot be overlooked.

The relationship between bonding capital and bridging capital is a crucial one and one deserving of much more attention than this report provides. The ends of all of this social activity must surely be human flourishing and building of the common good. While the CES 2018 data highlights certain relationship patterns, we are hesitant to draw broad conclusions beyond the need for all school sectors to be increasingly intentional in cultivating graduates that are capable of meaningful relationships and respecting and loving others.