Experiential Learning in Faith-Based Schools

Experiential learning that happens beyond the school walls has received significant attention in the literature. For the purpose of this case study, we use the terms “experiential learning” and “outreach” interchangeably. David Kolb (1984), drawing on the work of classic education thinkers such as John Dewey and Jean Piaget, has played a key role in developing the modern theory of experiential learning, which centres on the process of learning through experience and, importantly, through reflection on that experience. Kolb argues that because it relates to the meaning-making process of an individual’s direct experience, experiential learning can even take place without a teacher; indeed, it often relies on other adults as facilitators to guide the experience and encourage meaningful reflection. Kolb and Kolb (2009, 315) state that, in order to gain genuine knowledge from an experience, the learner must

- be willing to be actively involved in the experience;

- be able to reflect on the experience;

- possess and use analytical skills to conceptualize the experience; and

- possess decision-making and problem-solving skills in order to use the new ideas gained from the experience.

“Jesus served, and we want to teach our students to follow this example.”

When implemented well, experiential learning can benefit students in a variety of ways. In their study of project based learning in children, Kaldi, Filippatou, and Govaris (2011) find evidence that experiential learning may increase primary-school students’ motivation, content knowledge, and group-work skills. Related to experiential learning— and also offering unique benefits to students—is service learning. Billig (2000) argues that service learning is most effective when students are actively involved in their own learning and, further, when the learning has a distinct purpose in the community. “Service learning” is a method by which students or participants learn and develop through active participation in thoughtfully organized service that:

“is conducted in and meets the needs of a community; is coordinated with an elementary school, secondary school, institution of higher education, or community-service program and with the community; helps foster civic responsibility; is integrated into and enhances the (core) academic curriculum of the students, or the educational components of the community-service program in which the participants are enrolled; and provides structured time for the students or participants to reflect on the service experience.” (Billig, 659)

“Outreach is our DNA. It’s been part of our beginning, theologically, philosophically, and methodologically. It’s so much a part of us that we don’t think outside of the outreach perspective.”

In faith-based schools, the goal of service learning is not only to add depth of learning for students but also to instill in students a particular charitable posture in the world. Some Christian schools, including Pacific Academy, use the term “outreach” to describe living one’s faith by loving others—others both near and far away from students’ local experiences. These schools believe that students have deeper learning experiences when they are caring for others and living out their faith in real-world contexts. When it comes to Christian service learning and outreach (Lavery and Hackett 2008), the gospel’s call to serve is central. Lavery and Hackett (2008) identify four categories of community outreach: community service, Christian service, service learning within a Christian context, and a faith-focused service-learning experience. Outreach at Pacific Academy is committed to experiential and service learning for each student—and for the sake of others. The school’s Outreach Handbook cites the approach frequently attributed to St. Francis of Assisi: “Preach the gospel at all times. Use words if necessary” (Drisner 2007, 2–3).

Outreach and Service Learning at Pacific Academy

Experiential learning is a core component of Pacific Academy’s educational philosophy. The school involves as many students as possible in local service opportunities as well as various education and mission initiatives in over thirty different countries. All students are highly encouraged to participate in service learning in some way so that each student has an outreach experience at least once.

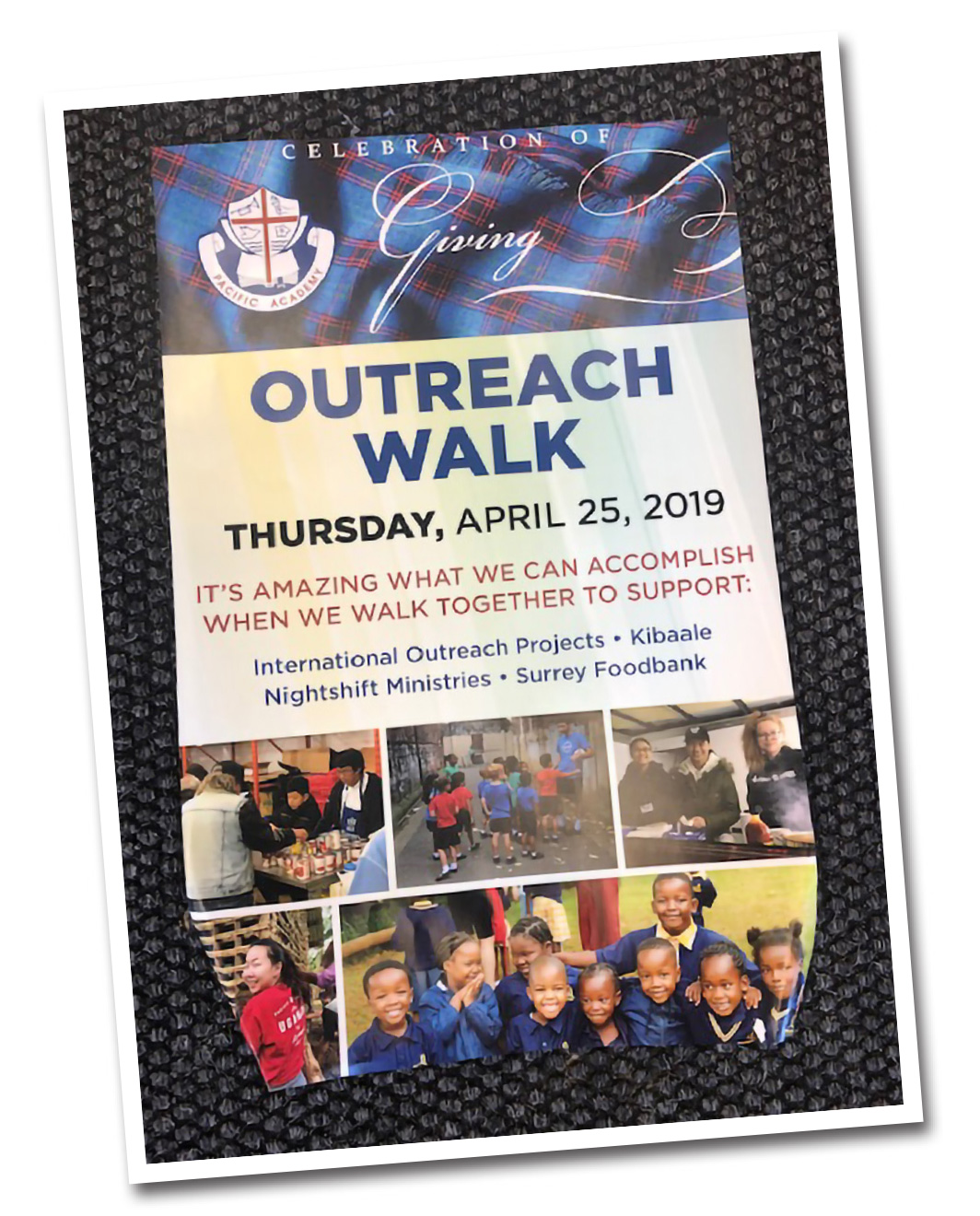

Outreach at Pacific Academy is student-centred, focusing on the development of students through service and discipleship activities (Drisner 2007, 1–1). From kindergarten through grade 12, participation in outreach is designed to enlarge students’ worldviews; increase their awareness and understanding of poverty, justice, and economics; enhance their compassion; enable them to live, develop, and express their faith; and equip them with leadership skills. These service initiatives begin within the school: all students “buddy” with their peers in different grade levels as a form of “internal outreach.” The buddy system helps to develop relationships across grades and enables peer coaching and support. The entire student body also comes together for “regular school-wide outreach opportunities such as Nightshift Ministries, the Outreach Walk, and the collection of food for various food banks” (Pacific Academy 2020c).

For external outreach, younger children start with projects that are closer to home, such as donating food to local food banks and helping support environmental causes based in the region. The most important outreach program for students in grades 1 and 2 involves visiting local senior housing centres: “Each class goes on a rotational basis, and when they go they spend about 30–35 minutes depending on the day. They sing to the seniors, they take artwork and books along to read, and they make cards for them at Christmas and Easter.” Primary- and intermediate-age children work with municipal authorities to do environmental outreach at a local park: using bags and tongs provided by the city, students clean up the park once a week. Grade 5 students lead a popular fundraiser in which they sell hot chocolate to their fellow students and teachers to raise money for a school in Africa.

Students in the middle-school division also participate in various forms of outreach. Members of the student council serve meals to the homeless at a local food bank. Some students volunteer at their home churches; others serve at Pacific Academy’s primary school by giving up their lunch break to monitor their younger peers. The school offers an award of excellence that recognizes student excellence across five categories: academics, conduct, community service, leadership, and creativity. It has successfully inspired students to set and achieve their own service goals: “One boy in grade 6 decided to start up a sock drive, and his goal was to collect 250 socks. He met his goal and then the next year collected 1000 socks. He has done the same thing year after year.”

As Pacific Academy students grow and mature, they have opportunities to serve farther afield. Within Canada, the high school has sent outreach teams to Québec and, even closer to home, to build relationships with First Nations people in Lillooet, British Columbia. Globally, Pacific Academy teams have worked on almost every continent.

“Foster a culture of service and have a strong biblical foundation. Pray for guidance and direction from the Holy Spirit. Then step out with faith and commitment to make it happen.”

According to the director of outreach, “Teams [will typically be] involved in some form of physical labour, but will spend the bulk of their time conducting some form of traditional short-term ministry.” Their work has ranged from building projects—including classrooms, clinics, churches, and houses—to digging wells, helping on child immunization campaigns, and delivering emergency food aid to crisis areas. In addition to encouraging students to grow spiritually, emotionally, and mentally, these experiences are designed to develop students’ leadership skills. The staff at Pacific Academy highlight the profound impact that international outreach experiences have on their students:

“After they have returned from an Outreach trip . . . they often express a greater sense of appreciation as well as a growing tension for the things that they feel are missing in Western culture. Furthermore, many of our students experience a greater awareness of the needs of others around them, both in their larger community and beyond.”

“If the staff members are inspired to support the program in any way they can, then the program will flourish.”

A Role for Administrators and School Leadership

Pacific Academy’s Christian faith is the foundation of its outreach initiatives. The school was founded in the Pentecostal tradition, which is philosophically and spiritually focused on the Great Commission (Matthew 28 and Acts 1:8). As such, Pacific Academy emphasizes local and global mission empowered by the Holy Spirit. This vision has been a “driving force which informs everything the school does.” As the school’s outreach director explains,

“The vision to be global servants through Christian education . . . is empowered by the Holy Spirit. Pacific Academy seeks to create an inspiring community of Christ-centred learners equipped to lead and serve. So the key words ‘to lead and serve’ are the crux of what we do. It is in the fabric of why we exist.”

The school attracts staff who want to serve, and there is strong support for the outreach focus of the school among teachers. Some teachers take on a more hands-on role by leading service teams overseas, while others play a more supportive or logistical role; all have outreach as a core component of classroom lessons. In their survey responses, Pacific Academy staff report that their goal as Christian educators is to raise students to be global citizens, focusing not only on academics but on character development as well. Outreach offers a way to teach students generosity, kindness, and empathy while partnering in God’s mission—a way of putting their faith into action: “Outreach is embedded in the vision and mission statement of the school, and undergirds much of what we do on a day to day basis. It is at the ‘heart’ of PA.”

The school’s leadership team and board of directors are an invaluable source of support for teachers who participate in outreach activities. The administration helps organize projects and source materials, provides teachers with information related to supporting local and international ministries, ensures that teachers’ classes are covered when needed, plans fundraisers, and raises awareness of initiatives. Teachers emphasize that their participation in Pacific Academy’s outreach is possible because of the administration’s enthusiastic support.

One of the staffing structures that Pacific Academy has adopted to strengthen its outreach program has been the director of outreach position: “Having a point person at the school to plan and organize and oversee outreach is vital.” The director of outreach works with the school’s leadership team to ensure that the general goals of the program are met and the experience is a positive one for students and staff. For every outreach trip, the director’s responsibilities include establishing budgets, ordering local currency, facilitating passport and deposit collection, organizing fundraisers, arranging transportation, applying for visas as necessary, and setting up an immunization clinic at the school. All team leaders work through a common devotional series prepared by the director, and one leader from each team is required to take a first-aid training course along with further sessions on risk management led by the director. The director also coordinates the delegation of tasks to team leaders, administrative support staff, and parents, who are kept informed and are encouraged to be involved in the preparation as they are able.

Pacific Academy stresses that leading any outreach activity—whether through weekly food-bank support, visits to seniors’ homes, environmental-sustainability efforts, or international service trips—“requires a great deal of organization and preparation in order to be successful” (Drisner 2007, 2–1). Pacific Academy has designed its schedule to create space for outreach planning. Yearly dates are set aside for an outreach walk, when students and staff do a sponsored walk to raise funds and awareness for outreach activities. Major fundraising campaigns are developed early in the school year to allow families plenty of time to participate.

“One of the most memorable things for me about outreach was just a moment when I was standing chatting with one of our students and he just had this look on his face. We were staying with families in the slum area of a city that we were in, and he said, this entire family is living in a home that’s smaller than my personal bathroom. And it just blew him away. It’s that level of impact that you know his perspective on the world has changed forever.”

Key to the long-term sustainability of Pacific Academy’s outreach has been its comprehensive preparation program, which is outlined in a month-by-month handbook featuring clearly defined tasks and role descriptions for team leaders. For each spring outreach trip, the planning process begins as early as the previous June, when students submit applications and potential leaders indicate interest. After leaders and destinations are finalized, leaders go on a retreat in August. In September, team members are chosen through an interview process; students selected to participate go on a retreat with their leaders and begin weekly team meetings. The school ensures that teachers and students have adequate time to prepare for outreach initiatives by reserving two hours on Monday afternoons for these meetings and other related events; no other activities can be scheduled during that period. In the weeks and months leading up to a team’s outreach project, this time slot is used to discuss expectations for travellers’ behaviour, study the team’s destination (e.g., language, culture, history, geography), prepare for ministry, develop creative lesson plans (such as dramas, puppet shows, or songs), and learn basic evangelism and public-speaking practices for sharing personal testimonies. Following the outreach experience, the meetings are used for debriefing and personal reflection.

Pacific Academy runs chapels before (“commissioning”) and after (“returning”) spring service trips “to inform and celebrate outreach opportunities.” At these chapels, the school community encourages and prays for the service teams, which in turn share slideshows and testimonies. Outreach chapels are key to strengthening the outreach program as a whole: “Fostering a school-wide awareness and focus on outreach helps to support teams as well as build anticipation and planning for students looking ahead to joining an outreach team.”

Key Takeaways

- A well-coordinated, school-wide system that connects every grade together in a system of experiential/service learning is most effective.

- Start service-learning in the early grades and connect those efforts with service and outreach experiences in the upper grades to inspire students to serve throughout their years at school.

- A natural extension of Christian schools’ faith foundation is serving as the hands and feet of Jesus in the world, whether through small initiatives close to home or major international outreach trips.

- Designating one leader to coordinate all outreach-related tasks provides a solid foundation for outreach trips, particularly those that require more intensive preparation.

- Comprehensive preparation is key to the long-term sustainability and effectiveness of outreach and service programs.

- Seeing service as the school’s purpose and having this vision shared by all the community energizes service efforts.

References

Billig, S. 2000. “Research on K–12 School-Based ServiceLearning: The Evidence Builds.” Digital Commons at University of Nebraska Omaha, May. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1003&context=slcek12.

Bergmark, U., and C. Kostenius. 2018. “Appreciative Student Voice Model—Reflecting on an Appreciative Inquiry Research Method for Facilitating Student Voice Processes.” Reflective Practice 19, no. 5: 623–37.

Calabrese, R. 2015. “A Collaboration of School Administrators and a University Faculty to Advance School Administrator Practices Using Appreciative Inquiry.” International Journal of Educational Management 29.2: 213–21.

Drisner, K. 2007. “Pacific Academy Outreach: Living the Adventure Vision and Implementation Guide.” Surrey, BC: Pacific Academy.

Gordon, S.P. 2016. “Expanding Our Horizons: Alternative Approaches to Practitioner Research.” Journal of Practitioner Research 1, no. 1: article 2.

Kaldi, S., D. Filippatou, and Govaris. 2011. “Project-Based Learning in Primary Schools: Effects on Pupils’ Learning and Attitudes.” Education 39, no. 1: 35–47.

Kolb, A.Y., and D.A. Kolb. 2009. “The Learning Way: Metacognitive Aspects of Experiential Learning.” Simulation and Gaming 40, no. 3: 297–327.

Kolb, D.A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lavery, S.D., and C. Hackett. 2008. “Christian Service Learning in Catholic Schools.” Journal of Religious Education 56, no. 3: 18–24.

Pacific Academy. 2020a. “Information for Applicants.” https://www.pacificacademy.net/admissions/information-applicants/.

Pacific Academy. 2020b. “Four Schools in One.” https://www.pacificacademy.net/experience-pa/four-schools-one.

Pacific Academy. 2020c. “Outreach.” https://www.pacificacademy.net/experience-pa/outreach/.

Ryan, F.J., M. Soven, J. Smither, W.M. Sullivan, and W.R. Van Buskirk. 1999. “Appreciative Inquiry: Using Personal Narratives for Initiating School Reform.” The Clearing House 7, no. 3: 164–67.

Stavros, J., L. Godwin, and D. Cooperrider. 2015. “Appreciative Inquiry: Organization Development and the Strengths Revolution.” In Practicing Organization Development: A Guide to Leading Change and Transformation, edited by W. Rothwell, R. Sullivan, and J. Stavros, 96–115. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Tittle, M.E. 2018. “Using Appreciative Inquiry to Discover School Administrators’ Learning Management Best Practices Development.” Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks, Walden University.

Waters, L., and M. White. 2015. “Case Study of a School Wellbeing Initiative: Using Appreciative Inquiry to Support Positive Change.” International Journal of Wellbeing 5, no. 1. https://www.internationaljournalofwellbeing.org/index.php/ijow/article/view/328.

Zepeda, S.J., and J.A. Ponticell. 2018. The Wiley Handbook of Educational Supervision. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.