Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Introduction

As a nation known globally for its diversity and openness, Canada continues to welcome to its shores immigrants who contribute their knowledge and skills to Canadian society and help the country to prosper. As of 2021, nearly one in four Canadians (23 percent) were born in another country. 1 1 Statistics Canada, Immigrants Make Up the Largest Share of the Population in over 150 Years and Continue to Shape Who We Are as Canadians (October 26, 2022), https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221026/dq221026a-eng.htm. This paper offers insights into the relationship between immigrants and faith communities by drawing on current research and on interviews of nine pastors of Christian churches across the country that serve immigrant communities. The paper offers these pastors’ perceptions of how various levels of government currently interact with immigrants and their recommendations for strengthening that interaction. Stronger collaboration between faith communities and government agencies has an important role to play in supporting immigrants in successfully settling and making Canada their new home.

Key Findings from Cardus Research

Since 2017, Cardus, in partnership with the Angus Reid Institute, has conducted polling to learn about Canadians’ religious beliefs, religious practices, and views regarding religion. The Spectrum of Spirituality Index was developed by Cardus and the Angus Reid Institute in order to provide greater nuance about Canadians’ religious identities and their spiritual lives.

Consider two hypothetical Canadians who select “Protestant” when responding to a survey question asking them what their religion is. One respondent selects Protestant because they were baptized in a church but otherwise have no involvement with the faith. The other respondent selects Protestant because they follow their church’s teachings and practices on a weekly basis. The Spectrum of Spirituality seeks to reveal these types of distinctions within Canadians’ religious self-understanding and to explore the role that spirituality and religious beliefs and practices play in Canadians’ lives.

Canadians are asked these questions about their beliefs and practices:

- whether they believe in God or a higher power

- whether they believe in life after death

- how important they think it is for a parent to teach their children about religious beliefs

- how often, if at all, the person feels they experience God’s presence

- how often, if at all, the person prays to God or a higher power

- how often, if at all, the person reads the Bible, Qu’ran, or other sacred text

- how often, if at all, the person attends religious services (other than weddings or funerals) 2 2 To respondents who indicated they do not think or do not believe God or a higher power exists, an eighth question was asked about their feelings of personal faith or spirituality.

Based on their answers, respondents are placed into one of four categories along a continuum, named Non-religious, Spiritually Uncertain, Privately Faithful, and Religiously Committed. As of spring 2022, the Spectrum enables reporting not only that 18 percent of Canadians identify as Protestant, for example, but that 10 percent of these Protestant Canadians are Non-religious, 56 percent are Spiritually Uncertain, 25 percent are Privately Faithful, and 9 percent are Religiously Committed.

The Spectrum was designed to incorporate a wide continuum of faith and spirituality across Canada’s main religious traditions. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that some of the index’s indicators may be less applicable measures of religious commitment for religions that place less emphasis on (for example) institutional religious practices or sacred texts. 3 3 For more information about the Spectrum of Spirituality Index, see Angus Reid Institute, “A Spectrum of Spirituality: Canadians Keep the Faith to Varying Degrees, But Few Reject It Entirely,” April 13, 2017, https://angusreid.org/religion-in-canada-150/; R. Pennings and J. Los, “The Shifting Landscape of Faith in Canada,” Cardus, 2022, https://cardus.ca/research/spirited-citizenship/reports/the-shifting-landscape-of-faith-in-canada/.

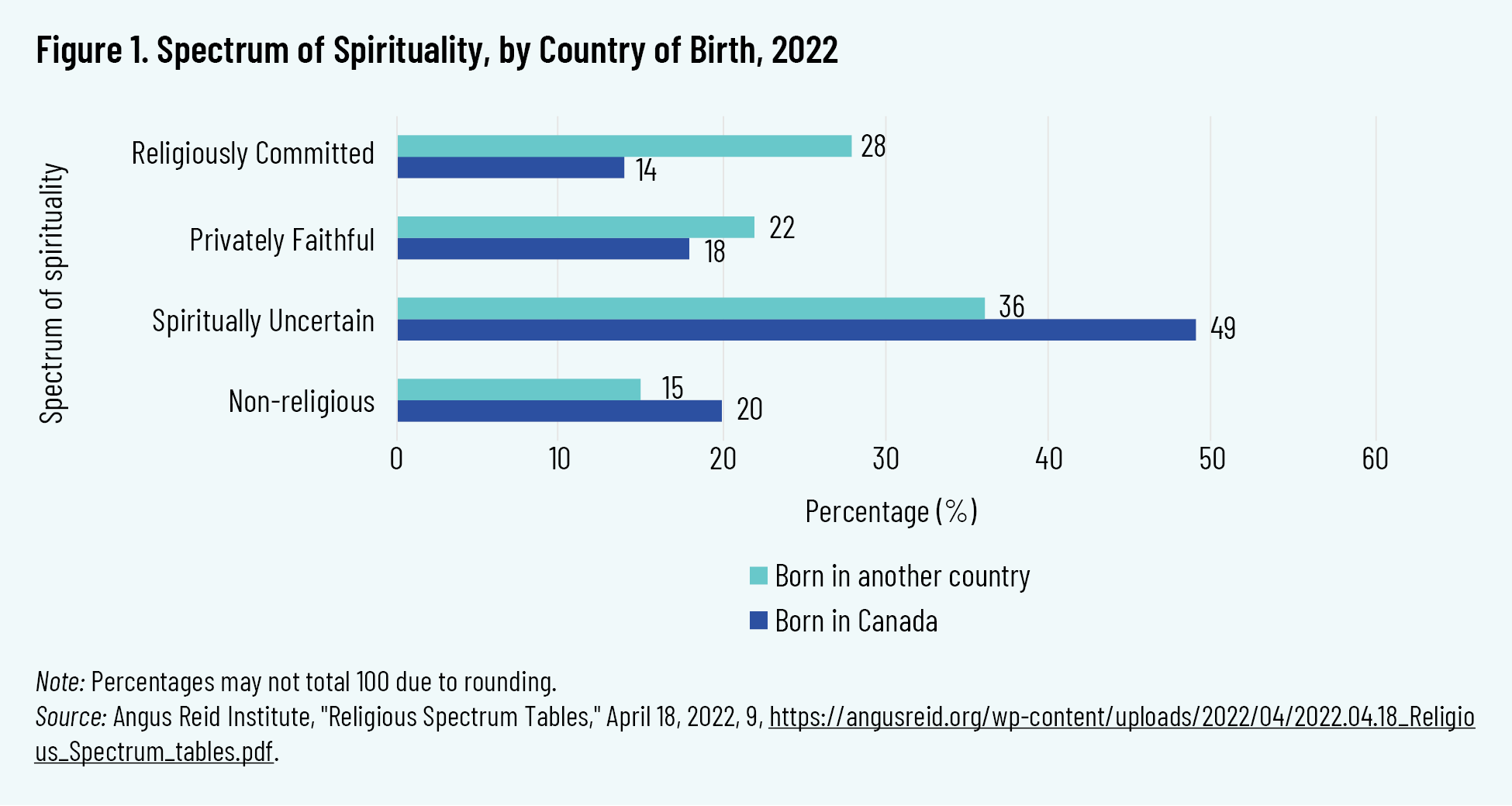

According to almost every metric in the Spectrum of Spirituality Index, immigrant Canadians displayed greater religious commitment than non-immigrants.

Of the Religiously Committed (16 percent of the total Canadian population), about one in four (26 percent) are immigrants and seven in twenty (34 percent) are visible minorities, the highest percentages among all groups. Immigrants are twice as likely as those born in Canada to be in this category (28 percent versus 14 percent). 4 4 Pennings and Los, “Shifting Landscape, 12.”

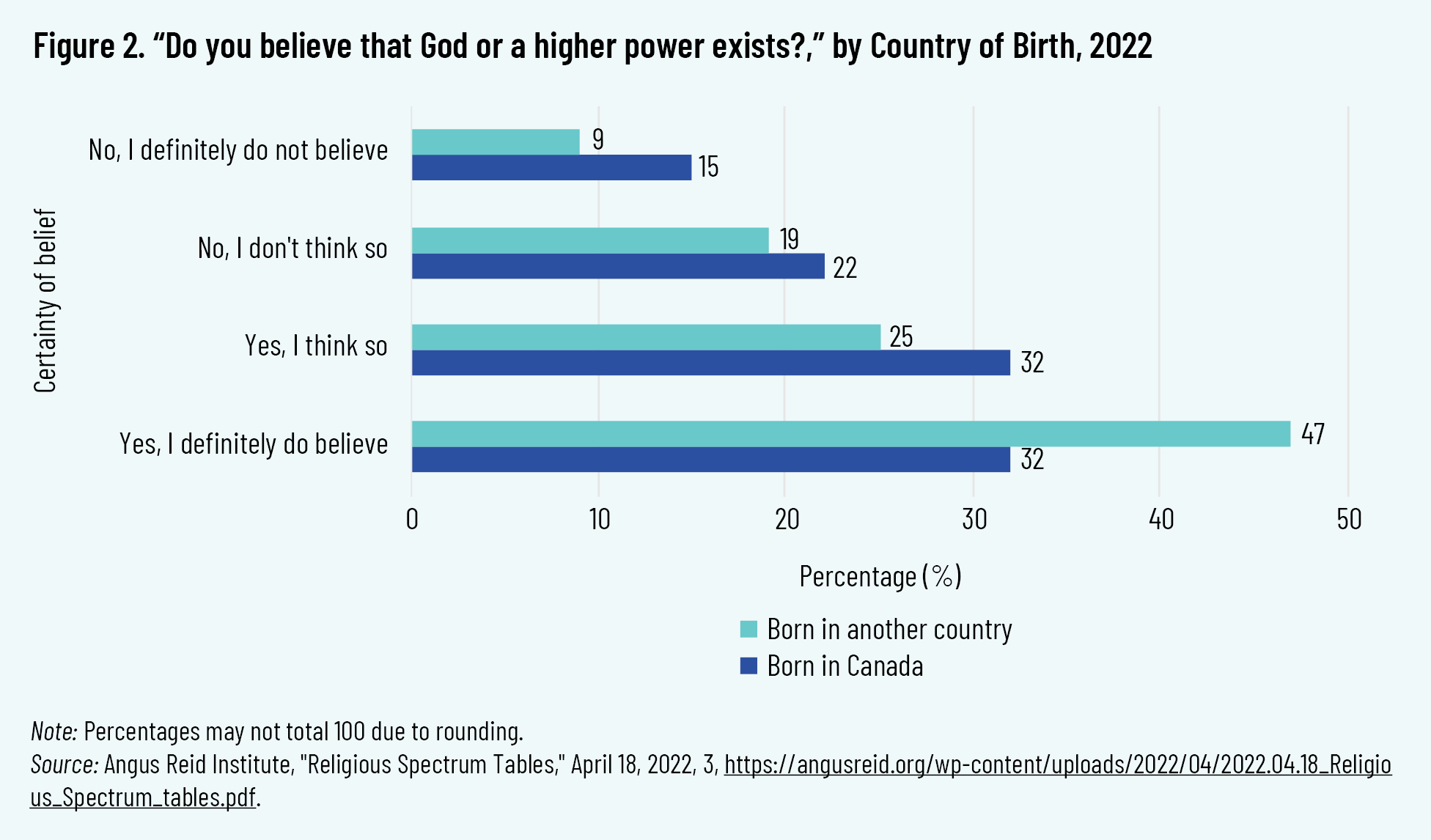

When asked whether they believe that God or a higher power exists, 47 percent of respondents born in another country say they definitely believe this, compared to 32 percent of respondents born in Canada. 5 5 J. Lewis, “Religion and Belief Among Immigrants to Canada,” July 2023, 4, https://cardus.ca/research/faith-communities/research-brief/religion-and-belief-among-immigrants-to-canada/.

When asked how often they experience God’s presence, if at all, immigrants report having this experience more often than their Canadian-born counterparts. Immigrants are about twice as likely to say that they experience God’s presence every day (29 percent, compared to 15 percent of non-immigrants). At the other end of the response range, 31 percent of immigrants report that they never have this experience, compared with 45 percent of respondents born in Canada. 6 6 Lewis, “Religion and Belief,” 5.

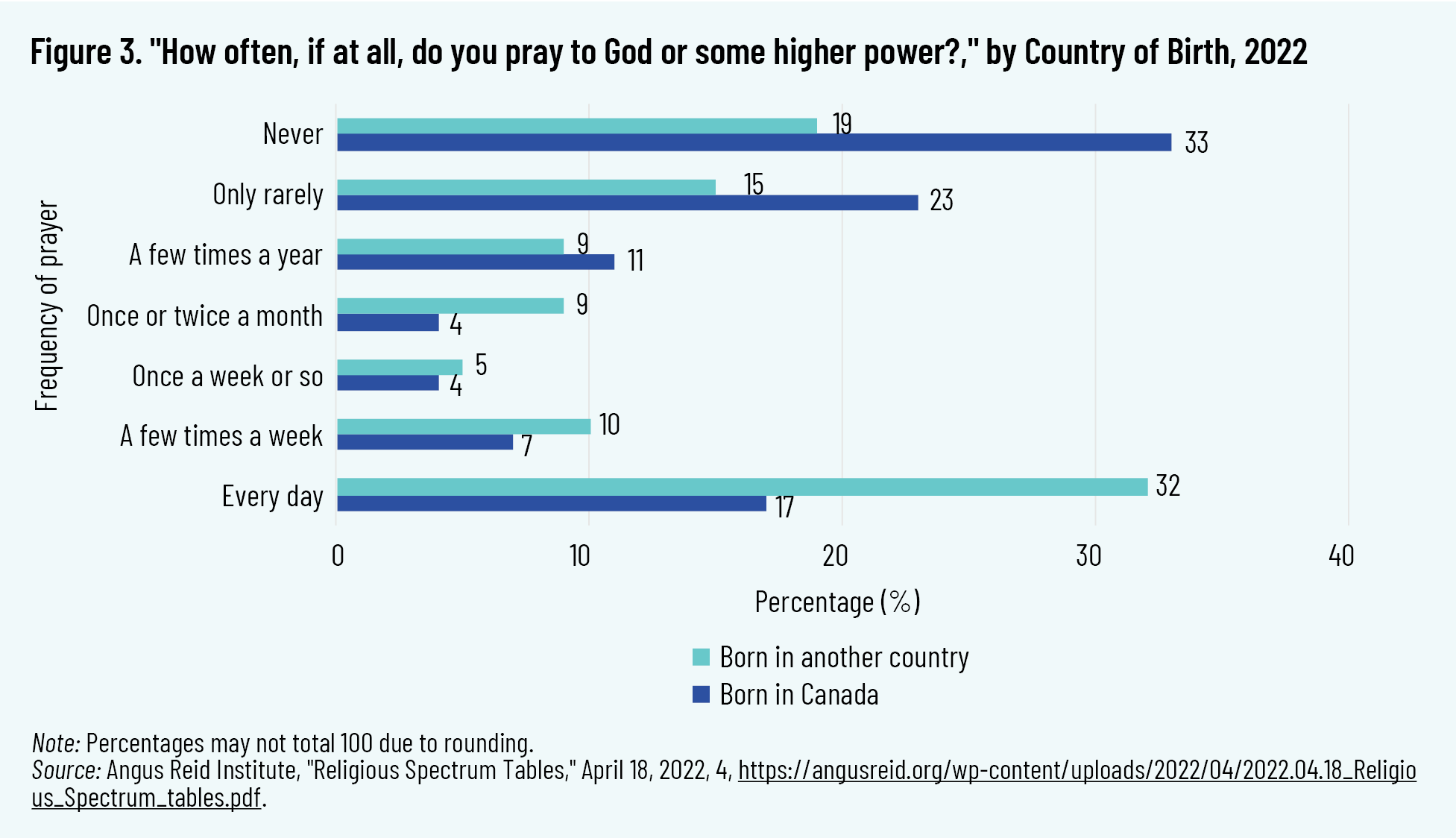

Thirty-two percent of immigrant respondents report that they pray every day, compared to 17 percent of non-immigrant respondents. 7 7 Lewis, “Religion and Belief,” 6.

When asked “How often, if at all, do you attend religious services apart from weddings and funerals?,” 43 percent of those born in Canada report that they never do, compared to 32 percent of those born in another country. Twenty-seven percent of immigrant respondents report that they attend at least once a month, compared with 13 percent of non-immigrants who report doing so. 8 8 Lewis, “Religion and Belief,” 7.

Views on whether “we should keep God and religion completely out of public life” also differ between immigrants and non-immigrants. Just over half (56 percent) of those born outside Canada agree with this statement, while two thirds (67 percent) of those born in Canada agree. 9 9 Lewis, “Religion and Belief,” 8.

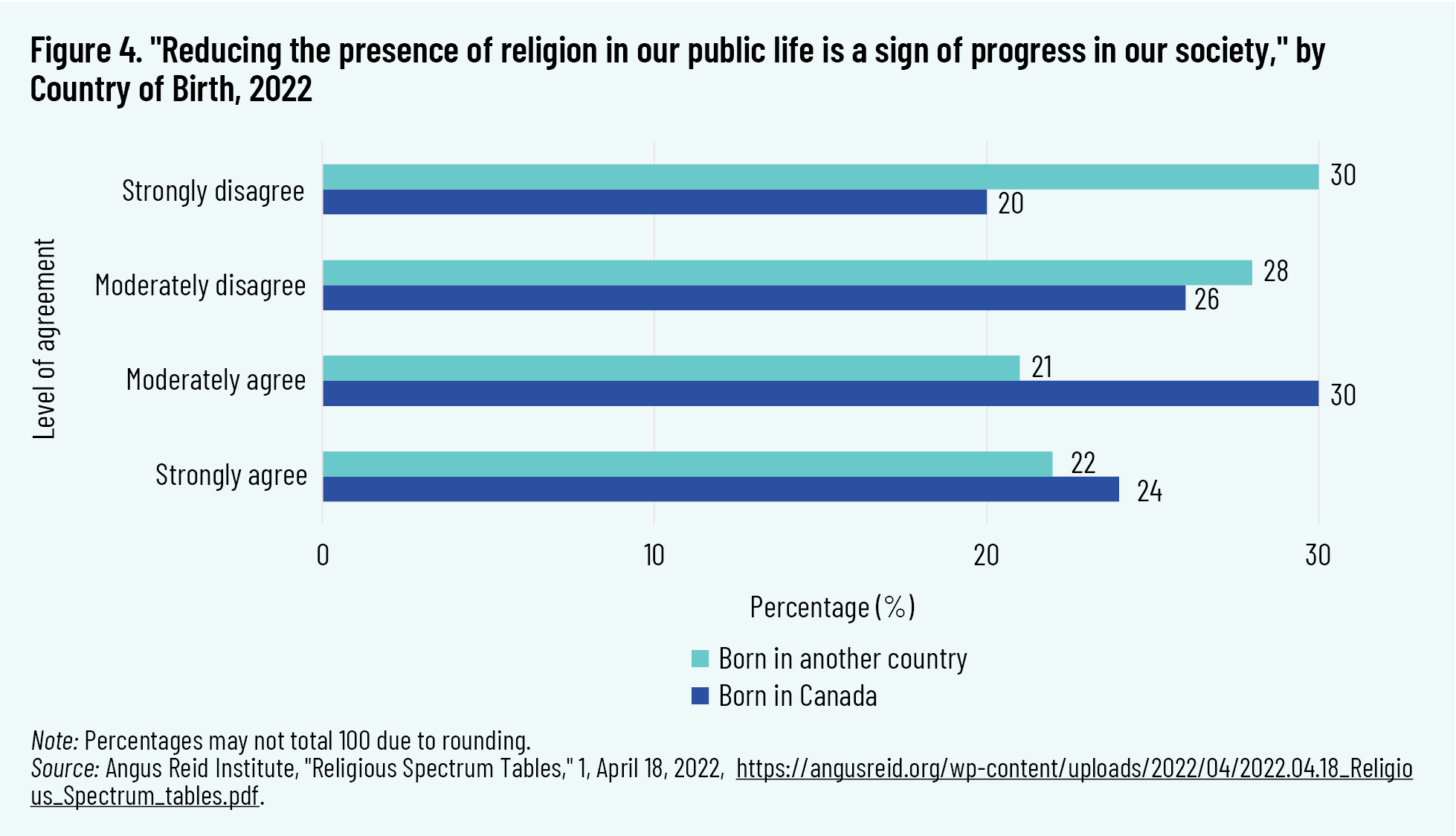

When asked to agree or disagree with the statement, “Reducing the presence of religion in our public life is a sign of progress in our society,” 58 percent of those born outside Canada disagree either strongly or somewhat, compared to 46 percent of Canadian-born respondents. 10 10 Lewis, “Religion and Belief,” 9.

In comparison to respondents born in Canada, immigrant respondents are more likely to agree with the statement that “the overall presence of each of these [named religions] in Canadian public life is benefiting Canada and Canadian society.” 11 11 Pennings and Los, “Shifting Landscape,” 49.

In 2023, Cardus examined the problem of religiously motivated hatred, in the wake of church burnings across the country and the rise in hate-motivated crime targeting the Jewish community. In addition to producing fear, anxiety, or worse, these hate crimes make it more difficult for churches or other targeted groups to serve the broader community. When a church is vandalized or targeted by arson, it can disrupt or halt its ability to deliver key services such as support to new immigrants, language-learning, and daycare programs. 12 12 A.P.W. Bennett and J. Lewis, “Toward a Hopeful Future: Facing Down Religious Hate,” Cardus, 2023, https://cardus.ca/research/faith-communities/research-brief/toward-a-hopeful-future-facing-down-religious-hate/. These programs are emblematic of the rich array of services that faith communities provide in cities, as highlighted in Cardus’s Halo Project. 13 13 “Halo Project,” Cardus, https://haloproject.ca/.

Key Findings from Interviews of Faith Leaders

Faith leaders provide unique perspectives on how churches serve as bridges between immigrants and Canadian society. Their responses highlight the challenges and opportunities that their congregants face.

Church Demographics and Ethnic Make-up

In 2024 we surveyed nine Christian pastors, selected as a convenience sample, who work in various contexts in British Columbia and Ontario: urban and suburban congregations, small (< 250) and large (>1,000) congregations, and representing Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholic, Oriental Orthodox, Evangelical, and Mainline Protestant traditions. Pastors shared detailed descriptions of their congregations, highlighting the diversity in their communities:

- Church 1 is in rural Ontario. According to its pastor, the congregation comprises approximately 60 percent white Canadians and 40 percent West African and South Asian immigrants.

- Church 2 is in urban British Columbia. The pastor noted that the church serves over 6,000 congregants from seventy-five countries, with services translated into eleven languages. The linguistic diversity underscores the church’s efforts to create inclusive worship experiences for immigrants.

- Church 3 is in urban British Columbia. The pastor described the congregation as having over thirty-five ethnicities, with an estimated 60 percent of members identifying as visible minorities. He noted that approximately 40 percent of congregants do not consider English their first language. There is significant representation from South America and Asia.

- Church 4 is in suburban British Columbia. The pastor provided detailed demographic data: 60 percent Filipino, 15 percent Vietnamese, and smaller percentages of congregants of Indian, Sri Lankan, African (mainly Nigerian), and European backgrounds.

- Church 5 is in urban Ontario. The pastor described the congregation as a multicultural ministry embracing attendees from Jamaica, Costa Rica, Trinidad and Tobago, Argentina, and Mexico, among other countries. He emphasized the church’s vision: “To embrace each congregant and make them find a home through the culture of the church that comes out of the heart of our Father in Heaven.”

- Church 6 is in suburban Ontario. The pastor explained that the church, established seven years ago, primarily serves Coptic families from Egypt, with smaller percentages of congregants from Sudan, Eritrea, and Iraq. A handful of members are converts of European ancestry. The church has grown to include more than two hundred families and acts as a cultural anchor for Egyptian immigrants in the region.

- Church 7 is in urban Ontario. The pastor reported that this church includes approximately 1,400 households, predominantly immigrants of Middle Eastern origin. The pastor noted that two thirds of the congregation are of Lebanese origin, with others being of Syrian, Palestinian, Iraqi, and Jordanian descent. Recent converts form a small but growing portion of the congregation.

- Church 8 in urban Ontario is a multilingual church serving a diverse community. While its services are conducted in Ukrainian and English, Polish and Russian are also commonly spoken among parishioners. The pastor highlights the church’s inclusivity: “A substantial number of parishioners have no Ukrainian background. Many join the church community for spiritual and cultural connection, regardless of their ethnicity.”

- Church 9 in urban Ontario is one of the largest churches in its denomination. Its location attracts a diverse congregation, including urban professionals, students, and families. While around two thirds are of European origin, it also includes significant numbers of Afro-Caribbean, Chinese, South Asian, and African attendees. The pastor explains, “Afro-Caribbeans arrived first in the 1970s–80s, followed by subsequent generations. The Chinese diaspora includes earlier families from Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, with an increasing segment from mainland China. South Asians, primarily Indian and some Sri Lankan, and Africans, notably Nigerian and Ugandan, are the newest and fastest-growing groups, often returning to familiar liturgy from home.”

The testimonies of these pastors underscore the vital role that Canadian churches play as hubs of cultural promotion, integration, and community building. By addressing both the spiritual and practical needs of immigrants, these churches help them navigate life in a new country while fostering connections with their religious and cultural heritage. This dual role solidifies their importance as bridges linking diverse newcomers to Canadian society more broadly.

Challenges that Immigrants Face

Immigrant congregants in Canadian churches face a range of challenges that reflect the difficulties of navigating a new society. The pastors surveyed provide a nuanced understanding of these issues, shedding light on the barriers that members of their communities encounter on their integration journey.

Fear and Uncertainty

A significant obstacle for many immigrants is the hesitation to engage with government services, due to the fear of negative repercussions on them and their immigrant status. Pastor 1 highlights this concern: “There’s fear, particularly among our immigrant members. Many have worked hard to gain entry into Canada, seeking a better future for their children or fleeing dangerous situations in their home countries. The last thing they want is to jeopardize their status by raising concerns, especially if it could seem contrary to those in power.”

This apprehension creates a barrier to accessing necessary support or voicing legitimate concerns, leaving some immigrants feeling vulnerable.

Language Barriers

Language barriers are a pervasive issue across the congregations surveyed, limiting immigrants’ ability to access essential services and support systems. Pastor 8 articulates this challenge in relation to government services: “Many new immigrants, particularly those with limited English skills, face significant challenges navigating government processes. Understanding the specialized terminology on government websites can be difficult, compounded by the inaccurate translations provided by tools like Google Translate for languages such as Ukrainian. Communicating over the phone is also challenging, as strong accents of government employees can be hard to understand, even for individuals with a reasonable command of English.”

Pastor 5 concurs, noting, “For many, one of the challenges they have as new immigrants is obviously the language, and how to find support to join socially with a stable job or with aids that give them emotional security in the challenges to establish in a new country.”

Similarly, Pastor 3 highlights the same concern, identifying “language barriers when navigating government services” as a persistent issue.

Systemic Issues

Immigrants grapple with complex bureaucratic systems, health care inaccessibility, and the general challenges of integrating into the socioeconomic, civic, and cultural fabric of Canadian society. Pastor 2 notes discrepancies in how different levels of government engage with his congregation’s community initiatives: “When we have engaged our federal MPs, they are seemingly unaware of [our church’s] active engagement in the wider community. Some of our provincial MLAs, on the other hand, are more appreciative. For example, one of our provincial MLAs opened doors for us to serve

in senior care homes.” This comment highlights the desire of immigrants in this congregation to contribute their time and talents to serve their new community, and a pastor’s desire for that civic participation to be recognized and encouraged.

Pastor 4 highlights concerns: “[Newcomers have] difficulty in applying for permanent residency—requirements are hard to meet. [They have] limited health care. Lack of knowledge of how to access government services is often aggravated by language barriers.”

Pastor 7 observes cultural differences that exacerbate these challenges: “Many feel that they prefer how the government in Canada deals with them versus back home, and they appreciate the rule of law and organization. However, they often face barriers, not necessarily with language, but more with mentality and mindset. A lot of times they feel that the government assumes that everyone has a Western mindset to things and does not take into consideration that people think differently. Many don’t understand how a country as advanced as Canada can have a health system that means they are unable to find a family doctor.”

Pastor 7 also emphasized frustrations with long wait times and systemic inefficiencies, compounded by inflation and limited health care access.

Socioeconomic Strains

High housing costs and underemployment affect immigrant communities. Churches 1 and 9 highlight how socioeconomic pressures can often limit the ability of immigrants to address some of the challenges they might face when interacting with government. Pastor 1 said, “With both spouses often working hard to stay afloat, especially given the mortgage rates, the idea of taking on the additional burden of engaging with the government can seem overwhelming.”

Pastor 5 adds that even those born in Canada face systemic barriers. His concern perhaps reflects a general frustration (which some other Canadians also experience) with what is perceived as excessively bureaucratic or inaccessible government programs and a lack of job opportunities: “There is another group whose parents immigrated to Canada when they were kids, and some were born here. Even when they study and try to find a job, they don’t feel the support and back-up from the government, finding themselves applying for long periods of time without success.”

These challenges, rooted in fear, language barriers, systemic inefficiencies, and socioeconomic pressures, highlight the complex realities that immigrant parishioners face. Faith leaders are uniquely positioned to advocate for their communities, bridging gaps and fostering resilience in the face of these obstacles.

Faith Leaders’ Recommendations for Government

Faith leaders emphasize the critical role of churches in supporting immigrant communities and bridging gaps between newcomers and Canadian society. Based on these pastors’ insights, we summarize their recommendations here for how government agencies could strengthen collaboration with faith organizations, streamline services, and provide targeted support for immigrant-focused initiatives.

Build Bridges Through Faith Leaders

Governments at all levels should recognize churches and other faith communities as trusted partners in immigrant integration. Faith leaders are uniquely positioned to provide cultural and spiritual insights, advocate for marginalized groups, and facilitate dialogue between immigrant communities and government agencies.

Pastor 4 highlights the need for practical support: “More legal guidance and information, so we can better avail [ourselves] of what is out there to help our parishioners, as well as greater social support.”

These partnerships can enhance the reach and efficacy of government programs, ensuring that they align with the needs of diverse populations.

Streamline Processes

To address systemic barriers that immigrants face, government agencies should simplify and optimize administrative processes.

- Simplify immigration procedures: Streamline applications for permanent residency and set clearer expectations regarding timelines. As Pastor 3 suggests, “[We need] clearer expectations of timelines. Example: when to expect a visa.”

- Expand language support programs: Providing robust language support is essential for improving accessibility. Pastor 5 recommends “support for new immigrants in the area of language translators.”

- Increase transparency in service delivery: Clear and consistent communication from government agencies can reduce frustration and build trust among immigrant communities.

Provide Financial and Structural Support

Pastors emphasized the need for enhanced funding and structural support to expand immigrant-focused programs that churches offer.

- Provide grants for immigrant-support programs: Funding should prioritize initiatives such as ESL classes, job training, and housing assistance. Pastor 5 stresses the need for “grants for churches who have multiple cultures to help and support [immigrants] get established.”

- Support job creation and housing affordability: Pastor 2 advocates for policies that “encourage job creation and lower the costs of food and housing.”

- Expand language services and social guidance: Expanding access to translators and offering guidance in finding jobs and accessing resources is crucial. As Pastor 5 states, immigrants need “more social guidance in finding a job and applying for any resource or benefit to support and help them to keep going.”

Conclusion

Canada’s religious diversity is both a gift and an opportunity. Churches and other faith communities are trusted institutions within immigrant communities, serving as bridges between immigrants and broader society. They provide invaluable support in addressing spiritual, social, and systemic challenges at the most local level.

Government agencies and church leaders can and should be partners in striving to achieve a shared goal: building a society in which everyone can thrive. By encouraging collaboration, simplifying

processes, and enabling faith communities as key partners in immigrant integration, Canada can ensure that our public square reflects the ideals of inclusivity and compassion—all buttressed by religious freedom.