Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Government-run gambling is ripe for reform. In our previous report, “Pressing Its Luck,” we examined the ways in which the state’s gambling monopoly operates as a tax on the marginalized—preying on the poor and those who are playing hard to join them. We concluded by offering four policy reforms that could help provinces kick their addiction to regressive gambling profits and build a system that works for, not against, low-income households. Here, we provide a more detailed framework for recovery by exploring each policy option in depth. Returning annual gambling profits to the poor through cash transfers is one option. A second is to promote asset building through a matched savings program. Governments can also work with financial institutions to offer prize-linked savings products, an innovative way to help families build emergency savings funds. Finally, given that gambling profits are drawn disproportionately from problem gamblers, we argue that governments should increase funding for problem-gambling research, prevention, and treatment out of provincial gambling corporations’ marketing budgets.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people who served as members of the advisory committee for this work:

Livio Di Matteo – Professor of Economics, Lakehead University

Ben Eisen – Adjunct Instructor in Public Policy, Drexel University

Brian Gilmore – Director, Commonwealth

Courtney Mo – Public Policy, Research & Evaluation Manager, Momentum

Michelle Pommels – CEO, Credit Counselling Canada

Michael Ras – Director, Government and Stakeholder Relations, Meridian Credit Union

Aaron Wudrick – Federal Director, Canadian Taxpayers Federation

We would like to publicly acknowledge their invaluable advice, constructive criticism, and feedback. The paper was strengthened by these contributions, and any fault with the paper should be a reflection on the authors, not on the committee.

Governments have a gambling problem. Across Canada, provinces have become addicted to the cash that state-run gambling provides to their treasuries each year. But a government’s gambling monopoly is more than just a lucrative form of entertainment: it functions as a hidden and regressive tax on the poor and the addicted. If government will continue deriving revenues in this manner, how could this gambling money be put to better use? How might government build a gambling structure that empowers those on the economic margins, rather than preying on them? This paper explores policy options to put this money back in the hands of those whom government-run gambling harms most, and to ensure that the government’s use of these funds is open, transparent, and accountable.

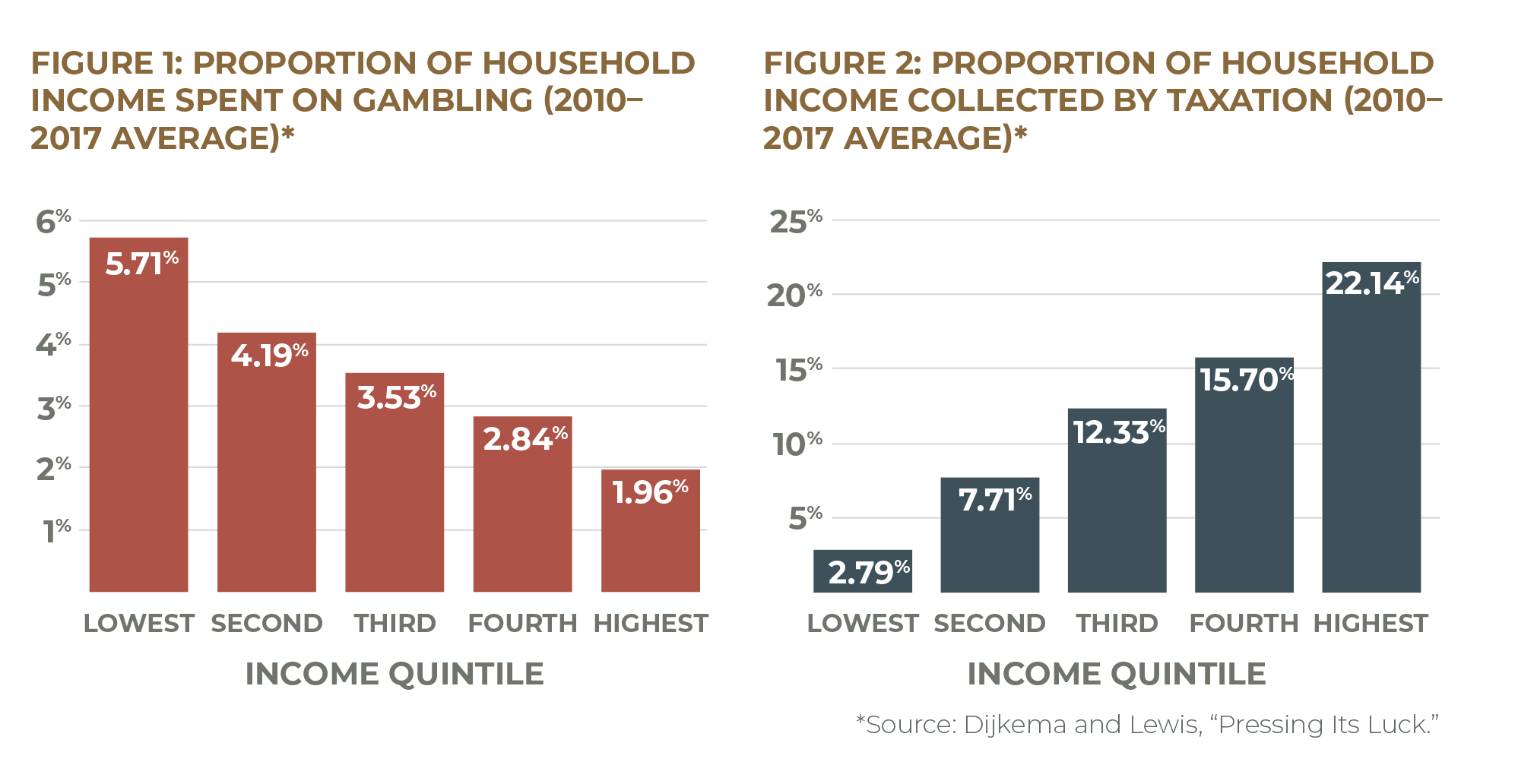

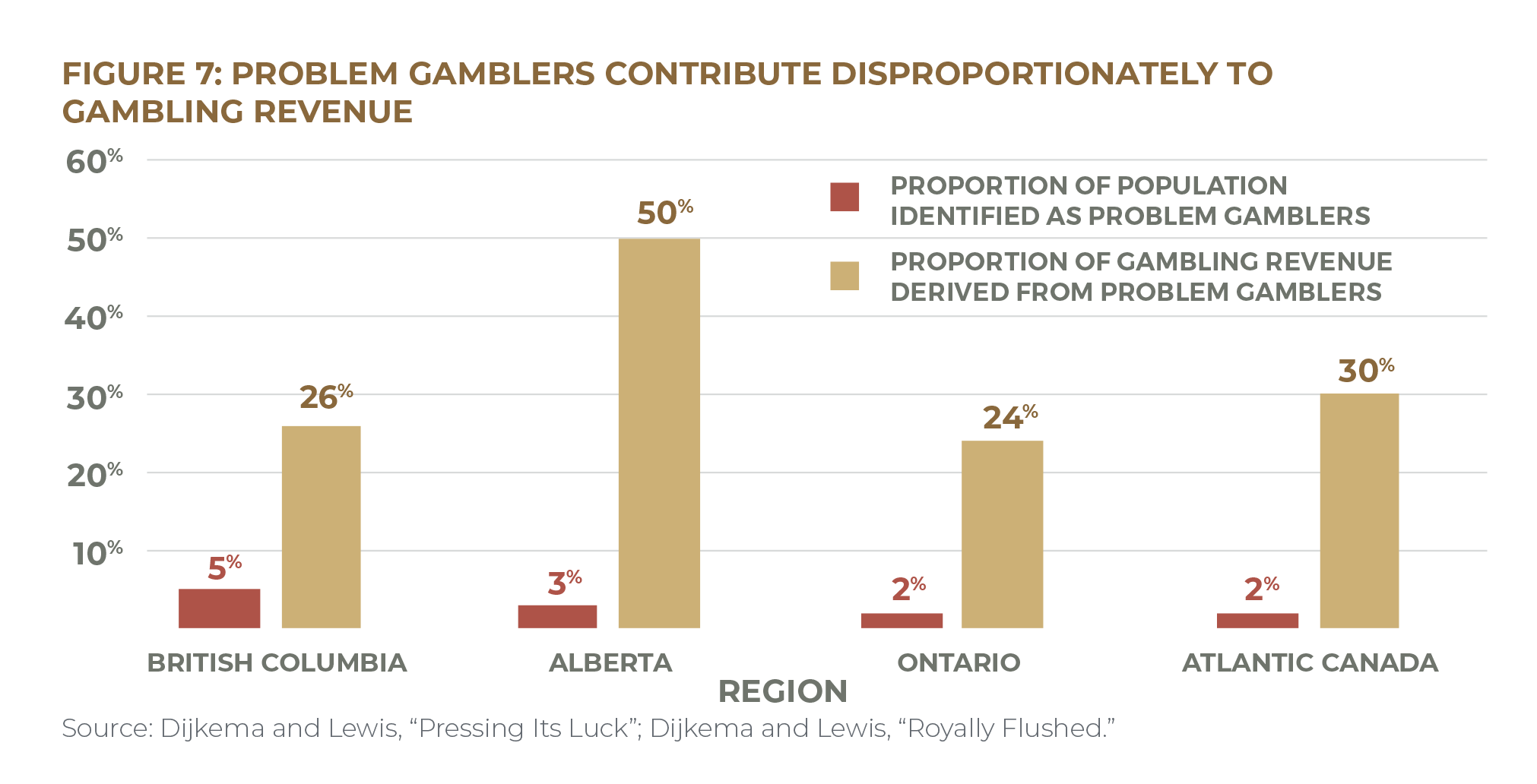

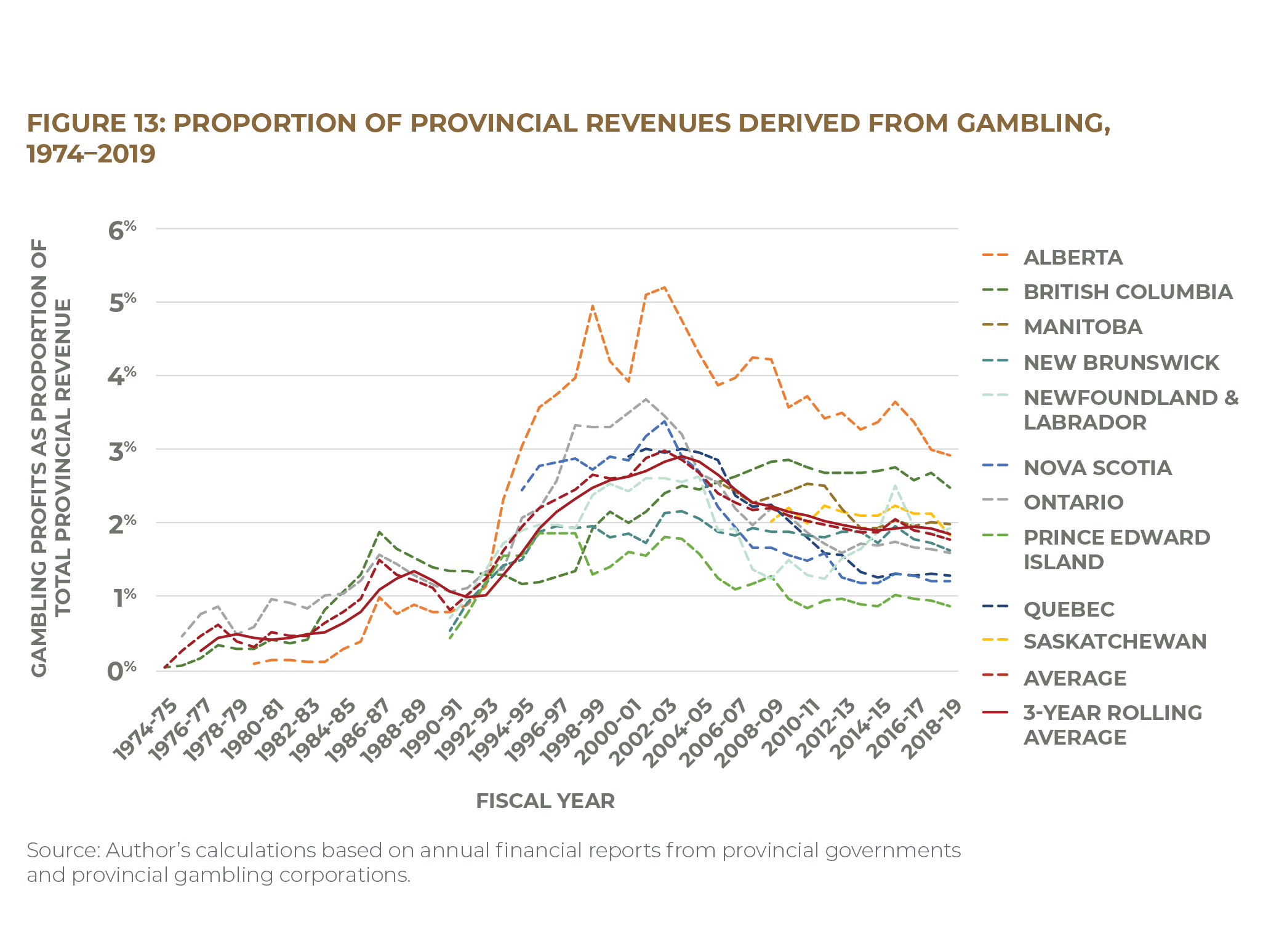

As noted in Cardus’s major study on provincial gambling policy in Canada, 1 1 Dijkema and Lewis, “Pressing Its Luck”; Dijkema and Lewis, Royally Flushed. gambling profits are treated just like tax revenues. Yet there is a significant difference in the way that these two types of revenue sources are collected, and in the burden that they place on citizens. Income and sales taxes are carefully designed to ensure that the poor shoulder a lighter tax burden than those with more: the proportion of income collected in income taxes from the wealthiest quintile is nearly ten times higher than that collected from the poorest quintile, and low- to moderate-income taxpayers receive regular rebates from the government to prevent their being disproportionately affected by sales taxes. Gambling, however, is a regressive revenue source—that is, relative to income it taxes the poor more heavily than the rich. Households in Canada’s lowest income quintile spend an average of 5.7 percent of their income on gambling each year. This is nearly three times the rate paid by the country’s highest-quintile households (see Figures 1 and 2). 2 2 Author’s calculations based on data from Statistics Canada, “Table 11-10-0193-01,” and Statistics Canada, “Table 11-10-0223-01.” For details on calculation methodology, see Dijkema and Lewis, “Pressing Its Luck.” Meanwhile, between 15 and 50 percent of gambling revenue comes from problem gamblers, even though they make up only 1–4 percent of the population (see Figure 7). 3 3 Williams and Wood, “What Proportion of Gambling Revenue”; Alberta Gambling Research Institute, “Adult Prevalence Studies of Problem Gambling.” Estimates of problem gambling prevalence can vary by jurisdiction and the way that problem gambling is defined and measured in a given study.

As we argue extensively in our earlier paper, money extracted disproportionately from the most vulnerable should not be lumped in with general tax revenue. No government should be using a system that hurts the poor to finance its policy agenda. The harmful way in which gambling profits are collected requires that these funds should be kept separate from tax revenue. Ontario’s government should properly account for its reliance on these hidden taxes. Moving gambling revenue out of the consolidated fund and into a specific fund would be the equivalent of the government admitting that it has a problem, admitting that it is harming the public that it is intended to protect, and forming the first steps to making direct amends. 4 4 Gamblers Anonymous, “Recovery Program.”

The best way for government to make amends is to take these funds and direct them toward policies aimed at addressing the savings gap: poorer Canadians have much more difficulty saving and building assets than do their middle- and upper-class counterparts, not only because they have lower incomes but also because government incentives to save are tailored to higher earners. The impetus for our project was to help make saving easier for people like Alice, whom we met (as readers may remember) during previous Cardus research on payday loans. We learned that one of the factors that made Alice vulnerable was low levels of liquid savings in the bank, making an expensive and risky payday loan her only option when a financial emergency struck. “Alice” is not a single person but an acronym used by DFC Global Corporation, one of the world’s largest providers of payday loans, to describe its target customer: “asset-limited, income-constrained, employed.” 5 5 Dijkema and McKendry, “Banking on the Margins,” 19–20. This is the demographic—those who are financially vulnerable due to low incomes and few assets—that we have in mind when we say that our goal is to help the poor save.

Provinces spend millions of dollars each year on gambling advertisements that urge players to spend their extra dollars rather than putting them away (see Figures 3 through 5). Lottery ads urge ticket buyers to dream of the financial freedom and security that winning might bring, a dream particularly tantalizing for those who feel locked out of traditional pathways to wealth. Polls have found that around a third of Canadians plan to fund their retirement with lottery winnings. Meanwhile, American data suggest that lower-income families are particularly likely to believe that hitting the jackpot is their best shot at wealth: nearly two-fifths (38 percent) of households with annual incomes below $25,000 said that winning the lottery was the most practical way for them to accumulate several hundred thousand dollars, while only 21 percent of the total sample said the same. 6 6 Scott, “34% of Canadians Plan to Retire by Winning the Lottery”; TD, “Ontario Boomers Not Ready for Retirement”; CFA and FPA, “How Americans View Personal Wealth”; see also Kingston, “Retirement 6/49.” Yet rather than fulfill these hopes, the gambling system siphons wealth from citizens’ bank accounts: governments make money from casinos and lotteries only because gamblers come out poorer in the long run.

Meanwhile, the families disproportionately harmed by the gambling system are the same families that benefit least from government policies designed to encourage saving. The federal government spends $45 billion on tax-advantaged registered savings plans such as RRSPs, which proportionately are used by and benefit middle- and upper-income Canadians with higher taxable incomes and who thus have more to gain from income-tax exemptions, deferrals, and deductions. 7 7 Côté, Mazer, and Weisstub, “Canada Saver’s Credit,” 3; Rothwell and Robson, “Prevalence and Composition,” 18. Even TFSAs, which were meant to fill this savings-policy gap, remain underused by lower-income savers. 8 8 Shillington, “Are Low-Income Savers Still in the Lurch?” The upshot is that those who could most use some extra help building savings are the least likely to get it. Restructuring Ontario’s gambling system to ensure that funds are used to incentivize savings for those on the economic margins would rectify the injustice inherent in our current system and further the prospects of Ontario’s poor.

Canada’s household savings rate has fallen dramatically over the last few decades. 9 9 Rothwell and Robson, “Prevalence and Composition,” 17. (The household saving rate spiked in 2020 as a result of government income-support programs and lockdown-related restrictions on spending, 10 10 Statistics Canada, “Household Economic Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” but whether high savings rates will continue as COVID-19 subsides is unclear.) Canadian families saved around 20 percent of their income in the 1980s compared to just 5 percent in 2018. 11 11 Côté, Mazer, and Weisstub, “Canada Saver’s Credit,” 10. In one 2019 survey, one-quarter of Canadians reported that they didn’t save anything at all in the past year. 12 12 Bank of Montreal, “BMO Household Savings Report.” Meanwhile, household debt levels have soared from 85 percent of disposable income in the 1990s to 170 percent today. 13 13 Côté, Mazer, and Weisstub, “Canada Saver’s Credit,” 10. Canadian households’ debt service ratio—the proportion of disposable income spent on debt payments—is projected to rise. 14 14 Parliamentary Budget Officer, “Household Indebtedness and Financial Vulnerability.”

And it’s not just savings writ large that is a challenge. Short-term saving for financial emergencies is critical for families with lower incomes: “While a low savings rate can slow the economic progress of middle- and upper-income families, the absence of savings can prove disastrous for lower-income households. That is because one function of savings is as a cushion for emergencies, such as losing a job or to cover an automobile repair in order to get to work.” 15 15 John, Butler, and Rust, “Boosting Economic Mobility Through Prize-Linked Savings.” A lack of assets may put families at greater risk of falling into poverty in the future, even though their current incomes put them above the poverty line. 16 16 Côté, Mazer, and Weisstub, “Canada Saver’s Credit,” 11. Even a small amount of savings can reduce financial vulnerability significantly, especially for those who lack access to good credit.

The Urban Institute, for example, found that a buffer of just $250–$749 makes families less vulnerable to hardship in the face of income loss. 27 27 McKernan et al., “Thriving Residents, Thriving Cities.” After controlling for other characteristics, households with $500 or less in liquid savings in their bank accounts are 2.6 times more likely to use payday loans than households with $2,000 to $8,000 in the bank. 28 28 Dijkema and McKendry, “Banking on the Margins,” 20; Pyper, “Payday Loans,” 8. Yet many Canadians are struggling to build up even a small buffer of emergency savings. In 2015, 29 percent of Canadians reported that their emergency savings would last a month or less. Almost half (44 percent) said that they had $5,000 or less in emergency savings. And 46 percent of Canadians said the lack of an emergency savings fund, either past or present, caused their debt to increase. 29 29 Bank of Montreal, “BMO Rainy Day Survey.”

The economic calamity induced by the COVID-19 pandemic has drawn fresh attention to the importance of a savings buffer. Sudden layoffs on an unprecedented scale have demonstrated that a loss of income can strike anyone at any time. 30 30 Many Canadians are asset-poor, making them particularly vulnerable to the loss of income accompanying an unexpected layoff. See Robson, “Assets in the New Government of Canada Poverty Dashboard”; Compass Working Capital, “Why Asset Poverty Matters”; Robson and Rothwell, “A Tale of Two Trends.” Yet claims for unemployment benefits spiked into the millions at a time when close to half of working-age Canadians do not have enough financial assets to cover their basic living expenses for three months. 31 31 Financial assets include “all non-pension financial assets at market value, i.e., all bank accounts, term deposits, mutual funds, stocks, bonds, and registered savings plans.” The ability to cover basic living expenses is defined as the ability to maintain a household at 50 percent of the median income. Rothwell and Robson, “Prevalence and Composition”; see also Alini, “Coronavirus.” Evidence from the United States suggests that savers have weathered the economic storm better than those without anything set aside: even after losing half of their pre-COVID income, families with savings were less likely to have to borrow, take on credit-card debt, or postpone bill payments to make ends meet compared to those whose incomes were similarly reduced but had no savings. 32 32 Gopnik and Collins, “Emergency Savings.”

Saving is an important way for households to build assets over the long term, improving financial stability and economic mobility. Research has found that the possession of assets has positive effects on individuals, families, and communities—such as increased confidence and higher rates of social and civic engagement—that are distinct from the effects of income. Assets have been linked to positive educational outcomes for children, 33 33 Rothwell and Robson, “Prevalence and Composition,” 18; Momentum, “Asset Building.” and “children of low-income, high-saving parents are more likely to experience upward income mobility” compared to children of low-income, low-saving parents. 34 34 Cramer et al., “A Penny Saved Is Mobility Earned,” 2. Low-income families with savings have better financial resilience than middle-income families without savings. 35 35 McKernan et al., “Thriving Residents, Thriving Cities.” And apart from any long-term impact on net worth, the habit of saving may itself “provide a sense of accomplishment that counteracts feelings of financial distress,” a security separate from and in addition to the security that the income and savings themselves provide. 36 36 Loibl, Kraybill, and DeMay, “Accounting for the Role of Habit in Regular Saving.”

Building financial security for all Canadians, but especially for the most vulnerable, is widely recognized as an important policy priority. With public budgets already upended by the pandemic, governments have a unique opportunity to kick their gambling addiction with relatively little disruption to provincial balance sheets. It’s time to reform the provinces’ gambling scheme to work for, not against, low-income households. But how? We examine four options below.

Option 1: Return gambling profits to the poor through cash transfers

The simplest option for policy-makers would be to give gambling money back to the poor. Instead of subsidizing general spending with a regressive tax taken from the pockets of the poor, the group disproportionately providing the tax would be the group that benefits from the tax. This policy would in many respects be no different from existing sales-tax rebate programs like the GST/HST tax credit: in order to prevent sales taxes from disproportionately burdening low- and moderate-income families, households whose incomes fall below a certain cut-off receive a quarterly payment from the government to offset the amount of sales tax they pay. 37 37 Canada Revenue Agency, “GST/HST Credit.”

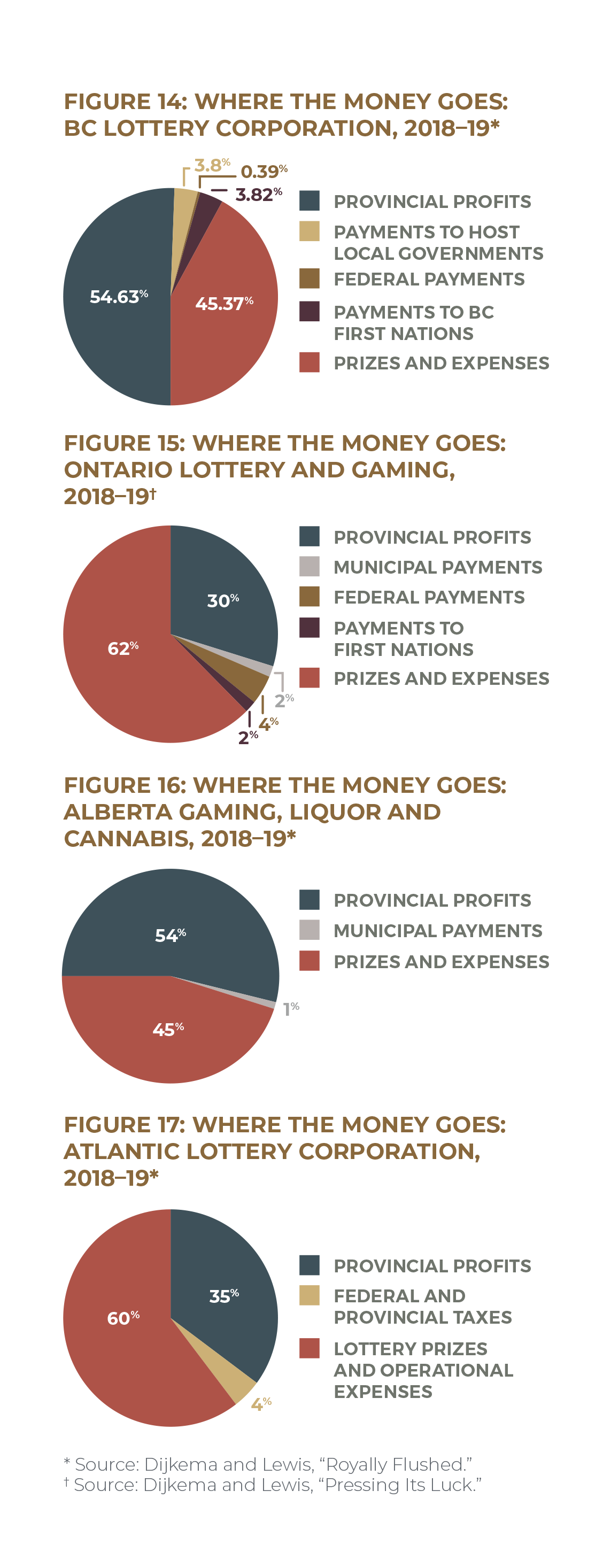

Cash-transfer programs are a common policy tool for both federal and provincial governments. Canadian examples include the Canada Workers Benefit (successor to the Working Income Tax Benefit), 38 38 Government of Canada, “Canada Workers Benefit.” Old Age Security 39 39 Government of Canada, “Old Age Security.” and the Guaranteed Income Supplement, 40 40 Government of Canada, “Guaranteed Income Supplement.” the Canada Child Benefit, 41 41 Government of Canada, “Canada Child Benefit.” and various provincial income-assistance programs. These can be paid out as a monthly income supplement (like the Guaranteed Income Supplement or Canada Child Benefit) or as an annual lump sum based on an individual’s income-tax return (like the Canada Workers Benefit). Most transfers are means-tested, with payments phasing out above a given income level. A new cash transfer funded by gambling profits—called, say, the Gaming Savings Credit (GSC)—could follow the same structure as existing transfers. Each year, a province’s total gambling profits would be divided among all households below a certain income cut-off, and the province would send a GSC cheque to each one. This benefit would be real money for low-income families: in Ontario, the GSC would have been worth around $1,886 per low-income adult in 2018; in Atlantic Canada, $1,888; in Alberta, $4,469; in British Columbia, $2,875. 42 42 Author’s calculations based on the number of adults (eighteen years and older) living below the poverty line, defined using Statistics Canada’s market-basket measure. Statistics Canada, “Table 11-10-0135-01: Low Income Statistics by Age, Sex and Economic Family Type”; Ontario Lottery and Gaming, “Annual Report 2017–18”; Atlantic Lottery Corporation, “Annual Report 2017–18”; Alberta Gaming, Liquor and Cannabis Corporation, “Annual Report 2017–18”; British Columbia Lottery Corporation, “2017/18 Annual Service Plan Report.” (It should be noted that these totals are similar to the amount of liquid savings in bank accounts linked to a significantly lower risk of using a payday loan.)

Policy benefits and disadvantages

The chief advantage of this policy option is its familiarity, which makes it easy to design and administer. Policy-makers could take advantage of existing infrastructure for determining eligibility for the benefit and delivering payments. The administration of the program would be particularly efficient if eligibility were tied to another transfer program—for instance, everyone receiving Ontario Works payments could be made eligible for the GSC. Another advantage to bundling the GSC with an existing program is that policy-makers would have flexibility in setting the parameters of the new transfer. If a government wanted to design the program to give a larger benefit to people with disabilities or to families with children, it could use the same sliding scale and supplements that have already been established in other programs: everyone who receives the disability supplement of the Canada Workers Benefit, for example, could receive a higher GSC payment.

Another major benefit of creating a new transfer is the opportunity to directly boost income equality by increasing the incomes of the poor. Research suggests that Canada’s tax and transfer system has helped reduce inequality over the last few decades. 43 43 Fortin et al., “Canadian Inequality.” An analysis by Statistics Canada estimated that in 2016, government transfers reduced low-income rates from 30 percent to 14 percent for women and from 28 percent to 12 percent for men; put another way, low-income rates would have been around 16 percent higher without the transfers. 44 44 Harding, “The Effect of Government Transfer Programs.” This analysis did not account for behavioural effects of transfer programs, such as labour market or social decisions made in response to government transfer policies.

Researchers have studied cash transfers extensively and have found positive effects on the well-being of low-income families and on children in particular. Unconditional transfers have been linked to positive educational outcomes, especially for poorer children. 45 45 Marinescu, “No Strings Attached.” There is modest evidence to suggest that unconditional cash transfers improve some health outcomes, increase the likelihood of enrolling in and attending school, and lead to higher spending on health care in low- and middle-income countries. 46 46 Pega et al., “Unconditional Cash Transfers”; Baird et al., “Conditional, Unconditional and Everything in Between”; Bastagli et al., “Cash Transfers.” In Canada, child benefits have grown increasingly effective at reducing low-income rates over the past two and a half decades, especially for women. 47 47 Harding, “The Effect of Government Transfer Programs.” Following the introduction of the Canada Child Benefit, food insecurity declined among Canadian families, with the effect most pronounced among financially vulnerable families. 48 48 Brown and Tarasuk, “Money Speaks.” The Canada Child Benefit has been associated with better maternal health as well as improved test scores and mental health for children. 49 49 Lebihan and Mao Takongmo, “Unconditional Cash Transfers and Parental Obesity”; Milligan and Stabile, “Do Child Tax Benefits Affect the Well-Being of Children?”; Daley, “Income and the Mental Health of Canadian Mothers.” Low-income pregnant women receiving an unconditional cash benefit in Manitoba had better birth outcomes than their comparable counterparts who did not receive the benefit, resulting in a narrower outcomes gap between high-income women and low-income women receiving the benefit. 50 50 Brownell et al., “An Unconditional Prenatal Income Supplement.” When researchers examined how the benefit contributed to the improved outcomes, they found that the unconditional nature of the transfer was key to the program’s success: women “were empowered to choose how to use the benefit to best meet their needs.” 51 51 Struthers et al., “Understanding the Particularities of an Unconditional Prenatal Cash Benefit.”

Consistent with these improved outcomes, researchers have found that cash-transfer income is generally used well and in line with the intention of the policy. Some studies have found that benefit recipients save a portion of their transfer payments or use them to pay down debt. 52 52 Halpern-Meekin, “It’s Not Like I’m Poor”; Edin, Tach, and Halpern-Meekin, “Tax Code Knowledge and Behavioural Responses among EITC Recipients”; Mendenhall et al., “The Role of Earned Income Tax Credit”; Shaefer, Song, and Williams Shanks, “Do Single Mothers in the United States Use the Earned Income Tax Credit to Reduce Unsecured Debt?”; Despard et al., “Do EITC Recipients Use Tax Refunds to Get Ahead?”; Smeeding, Ross Phillips, and O’Connor, “The EITC”; Jones and Michelmore, “The Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Household Finances.” The effect of policies like the Working Income Tax Benefit or Earned Income Tax Credit on savings behaviour is not necessarily due to the payment alone—their labour-market incentives, for instance, may also contribute to regular saving by encouraging recipients to enter the labour force, which could increase income and the amount these recipients can put away. In other words, it may not be the money from the benefit itself that leads to saving, but the labour-supply effect of the benefit. Jones and Michelmore, “The Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit,” for instance, finds evidence of substantial saving after receiving the Credit only when expansions to the benefit also increased earned income. McGranahan, “Tax Credits and the Debt Position of U.S. Households,” finds that households use their refunds to pay down delinquent debt—i.e., debt for which households are overdue on payment deadlines—but also to increase auto and credit card debt. Evidence from the Working Income Tax Benefit, Canada Child Benefit, and the Earned Income Tax Credit, an American transfer program, indicates that while most recipients spend at least a portion of their refund and benefit income immediately, much of the money is used for necessities such as food, housing, and school supplies. 53 53 Despard et al., “Do EITC Recipients Use Tax Refunds to Get Ahead?”; Goodman-Bacon and McGranahan, “How Do EITC Recipients Spend Their Refunds?”; Smeeding, Phillips, and O’Connor, “The EITC”; for similar international evidence, see Raschke, “The Impact of the German Child Benefit on Child Well-Being”; Raschke, “The Impact of the German Child Benefit on Household Expenditures and Consumption.” Jones, Milligan, and Stabile demonstrate that low-income families in Canada spend their Canada Child Benefit income on tuition and educational supplies and on household essentials, including child care, basic food in stores, and transportation. They also find evidence that receiving the Canada Child Benefit causes families to reorganize their budgets in financially healthy ways, observing decreases in spending on restaurant meals, alcohol, and tobacco. 54 54 Jones, Milligan, and Stabile, “Child Cash Benefits and Family Expenditures.” Similarly, Adams, Amedah, and Fougère examine the Canada Child Benefit and find that families use their benefit to pay for child care and school-related expenses. 55 55 Adams, Amedah, and Fougère, “Measuring the Effect of Child Benefit on Household Expenditures.”

Yet the GSC also has its drawbacks. Perhaps the most problematic is a corruption of purpose—money is being taken from the same vulnerable groups that it is then used to support. Our response to such an argument would be that since gambling is here to stay, and the best place for the profits to go is to the government (rather than a corporation whose primary duty is to enrich shareholders rather than promote the common good, or even worse, organized crime), these profits should be used to benefit the people most harmed before any other group. Another concern is that supplementing income assistance with gambling profits might simply mean a reallocation (i.e., a lowering) of other expenditures related to income support, leaving the government’s gambling addiction intact. The recent recommendation of creating a type of sovereign wealth fund with “sin taxes” 56 56 Di Matteo, “The Fiscal Wages of Sin.” is particularly vulnerable to this concern. If the government uses the GSC as an excuse to cut program costs elsewhere, the GSC will have done little more than move money around. It may even make the situation worse, by causing policy-makers to think that they have succeeded at solving the problem—or by strengthening the incentive to increase gambling revenues in order to support a good cause. In this case, the only potential success of the policy would be if GSC funds were kept separate from general revenues, which would increase transparency in the use of gambling money and thus improve government accountability.

As with other cash-transfer programs, the GSC could have negative labour-market effects if not carefully designed. The new means-tested benefit income could act as a disincentive to employment for households receiving it, particularly if this income is clawed back as earnings rise (or interacts with other transfer programs to have a similar effect). 57 57 See, e.g., Laurin, “Two-Parent Families with Children.” But this danger is not inherent in the transfer itself, simply a consideration for program design. Other cash-transfer programs such as the Working Income Tax Benefit / Canada Workers Benefit and the Earned Income Tax Credit were carefully—and, as research has demonstrated, fairly successfully—designed to encourage labour-market participation. 58 58 See, e.g., Eissa and Hoynes, “Behavioral Responses to Taxes”; Eissa and Liebman, “Labour Supply Response to the Earned Income Tax Credit”; Hotz and Scholz, “The Earned Income Tax Credit,”; Agostinelli, Borghesan, and Sorrenti, “Welfare, Workfare and Labor Supply”; Hasan, “Labour Supply Response to the Working Income Tax Benefit”; Annabi, Boudribilia, and Harvey, “Labour Supply and Income Distribution Effects of the Working Income Tax Benefit.” One possible solution would be to tie eligibility for the GSC to receipt of existing transfer programs with work incentives. In addition to reducing potential labour-market barriers, bundling these credits would streamline the administrative process. Moreover, while the GSC would be large enough to have a meaningful positive impact on a low-income household’s finances, it is still a relatively modest sum at just under $2,000.

Even more relevant to the other goals of this paper, a transfer is not biased in favour of savings habits. Both Ottawa and the provinces already have a suite of transfer policies that provide income assistance to the poor, but as mentioned above, the existing policy framework does very little to help low-income Canadians save (and in many cases includes strong disincentives for saving, such as asset limits in means-tested programs). Those whose financial vulnerability stems from asset poverty rather than income poverty won’t be helped by another transfer program designed to boost income. 59 59 Rothwell and Robson, “Prevalence and Composition,” 25.

The GSC could however be oriented toward saving by including in the program an incentive to save the benefit payment. Rather than issuing monthly cheques, the government could pay out a lump sum once a year so as to prevent dependence on these funds to pay bills. As a further nudge toward savings, the credit could be deposited directly into a recipient’s TFSA. 60 60 See also Côté, Mazer, and Weisstub, “Canada Saver’s Credit.” Though this approach would involve some additional administrative work for those who had not yet set up a TFSA, this barrier would be relatively low since almost all Canadian adults have at least one account at a bank or other financial institution. 61 61 World Bank, “The Global Findex Database 2017.” Another way to deliver this payment would be to bundle it with a person’s annual income-tax refund. Low-income families could be encouraged to save some (or all) of their refund when they receive it. Indeed, many organizations working to build financial security have targeted tax time as a valuable window to incentivize saving by offering a matching credit to those who save some of their refund. Tax refunds are the largest single chunk of money many low-income households can expect to receive in a year. While they may not have much left over to save after paying the bills in a typical month, their refund gives them some extra cash that could be put away, placing them in a better position to handle a financial emergency if one strikes later in the year. 62 62 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Increasing Saving at Tax Time.” Tax-time incentivized savings programs have met with moderate success in both Canada and the United States. 63 63 Momentum, “Incentivized Saving”; Azurdia and Freedman, “Encouraging Nonretirement Savings,” ES1–9.

As with the transfer program itself, there are both benefits and drawbacks to enhancing the GSC with a tax-time savings incentive. On the one hand, it would help meet the need for savings incentives targeted to income- and asset-poor Canadians, and it would be a relatively low-touch program compared to other matched savings initiatives (which we turn to next). But on the other hand, such a program would need to be administered in cooperation with community services organizations (to promote and explain the savings option, provide tax-filing assistance, and help interested participants deposit their benefit and withdraw their match a year later) and/or financial institutions (to deliver the savings accounts and monitor which account holders maintain their balance long enough to be eligible for a match). There are many non-profit organizations and financial institutions already doing this kind of work across Canada, so a government interested in exploring this option would have plenty of partners with whom it could initiate a tax-time saving-program trial. Nevertheless, the involvement of multiple players and the year-long timeline eliminate the very simplicity that might make this policy option more appealing than the others.

Conclusion

As with existing sales-tax rebate programs, returning gambling profits to low-income Canadians through a cash-transfer program like the GSC would help prevent governments from relying on a regressive revenue source that disproportionately burdens the poor. It could work with other transfer programs to improve the financial well-being of vulnerable households. Policy-makers would need to design the program carefully to ensure transparency and avoid unintended negative effects. While the GSC does not directly address the lack of savings incentives tailored to low-income households, there are nevertheless several options available to build savings nudges into the program in partnership with civil-society organizations.

Option 2: Promote asset building with matched savings

A second policy option is to use gambling profits to fund a matched savings program. At its most basic level, this program would use gambling dollars to reward saving by matching participants’ contributions to designated savings accounts. Many governments and non-profit organizations use a wide variety of matched savings programs to encourage saving. One of the most well-known Canadian examples is the Registered Education Savings Plan, a program in which the government adds money to a savings account designated for a child’s education. On the more intensive side are programs modelled after individual development accounts (IDAs), an asset-based welfare initiative developed by Michael Sherraden in his seminal 1991 book Assets and the Poor: A New American Welfare Policy. 64 64 Sherraden, Assets and the Poor. IDA programs generally have several common components. At their core is a savings account for low-income individuals, who can earn matching credits on every dollar they save up to a maximum or match cap. Eligibility is means-tested, restricted to those below a certain income threshold and holding a limited amount of liquid assets. Participants have a designated period of time in which to save toward a specific goal. During this time, they receive training—sometimes voluntary, sometimes mandatory—in financial management, such as budgeting skills and different types of credit. Participants receive matching credits with their deposits only if they use their withdrawals for designated investments, typically education or training, starting a small business, or homeownership.

IDAs and similar matched savings programs are designed to accomplish several interrelated objectives. They directly fill the gap in tax-based and other financial incentives for saving that low-income households experience. They are designed to help participants reach a financial goal that will improve their long-term earning potential and, ideally, net worth. The program is generally structured in such a way as “to kick-start a savings habit,” 65 65 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 12. encouraging participants to save regularly during and after the program. The financial education and coaching help improve participants’ financial literacy. Tying the matching credits to a formal savings account also works to strengthen participants’ connection to mainstream financial institutions, which tends to be weaker among low-income households (whose lower levels of income, financial capital, and assets make accessing credit more difficult, since banks have less information and fewer indicators with which to evaluate their credit risk). 66 66 Leckie, Dowie, and Gyorfi-Dyke, “Early Impacts,” 3.

Several developed countries have tested asset-building policies on a large scale in recent years. The American Dream Demonstration followed fourteen IDA programs, representing about 2,400 accounts across the country, from 1997 to 2002, and found that the poor can save: the average participant saved US$16 (CA$21) per month—nearly US$200 (over CA$250) per year—and the poorest participants saved a higher proportion of their income than others. IDAs are now offered by hundreds of social-service organizations across the United States. 67 67 Sherraden, “Innovations in Asset Building”; Feldman, “Saving from Poverty,” 185–88. Another matched savings program is the United Kingdom’s Help to Save program (a successor to the extensively piloted, but ultimately axed, Saving Gateway). 68 68 BBC News, “Budget: Saving Gateway Scheme Is Scrapped”; Kelly, “Welcome Back, Help to Save.” The program offers 50p for every £1 saved by eligible participants. Participants have four years in which to save and can earn up to £1,200 in matching bonuses on their savings. 69 69 GOV.UK, “Get Help with Savings if You’re on a Low Income (Help to Save).” Eligibility for Help to Save is tied to eligibility for other means-tested credits. 70 70 GOV.UK, “Get Help with Savings if You’re on a Low Income (Help to Save): Eligibility.” Participants can continue using their Help to Save accounts if they stop claiming benefits. While asset limits for some (though not all) means-tested programs are sensitive to participants’ contributions to their Help to Save accounts (i.e., the amount of benefits participants receive will be affected if their own deposits exceed the asset limits of these programs), benefit payments are not affected by the bonuses paid through Help to Save. 71 71 GOV.UK, “Get Help with Savings if You’re on a Low Income (Help to Save): How It Will Affect Your Benefits.”

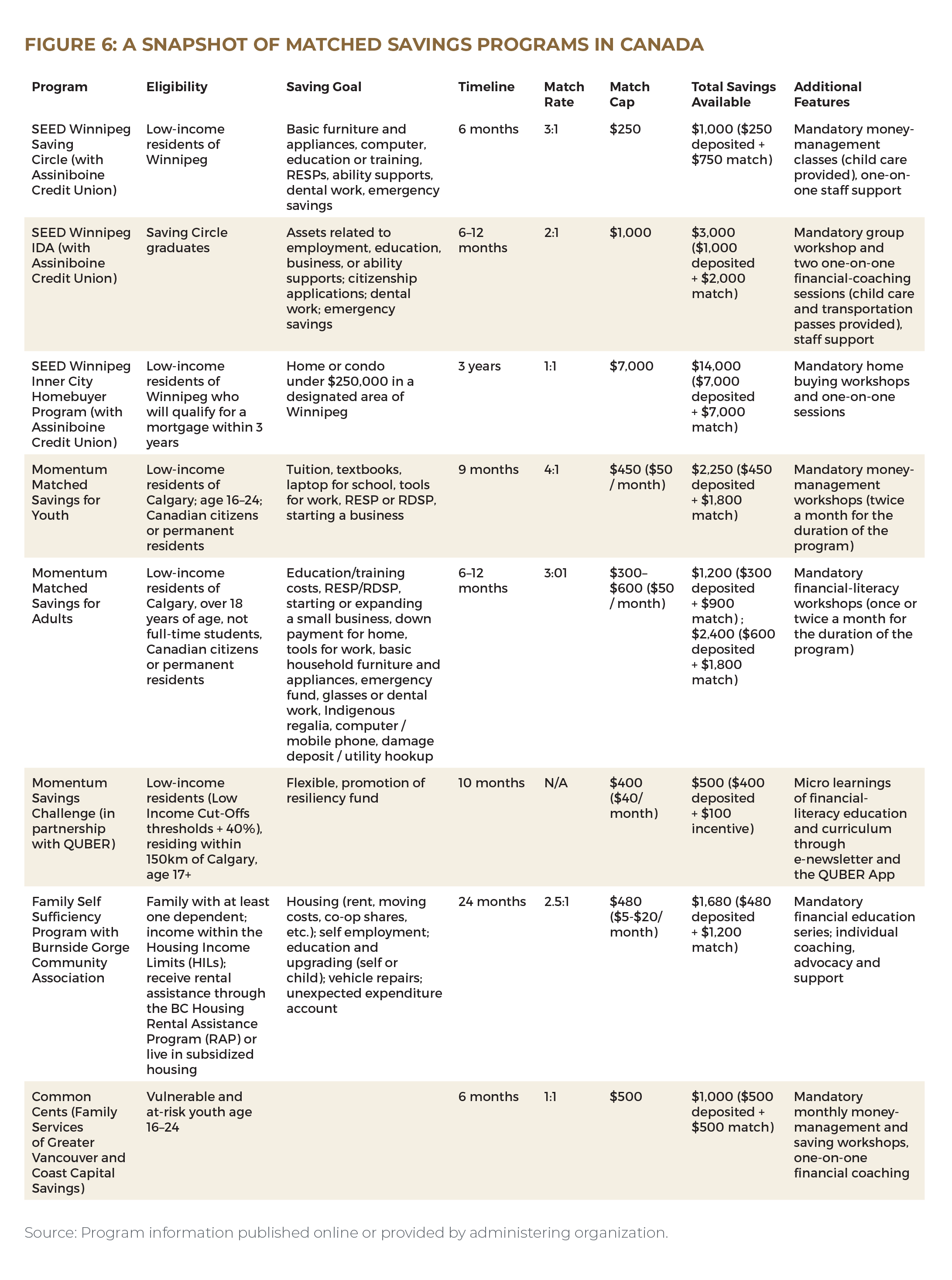

IDAs or similar matched savings accounts are also available in certain parts of Canada, where they are offered by non-profit organizations including SEED Winnipeg (Saving Circle, 72 72 SEED Winnipeg, “Saving Circle”; SEED Winnipeg, “Saving Circle Booklet.” IDA, 73 73 SEED Winnipeg, “Individual Development Account”; SEED Winnipeg, “IDA Booklet.” Inner City Homebuyer Program 74 74 SEED Winnipeg, “Inner City Homebuyer Program.” ), Momentum Calgary (Matched Savings for Youth, formerly Youth Fair Gains 75 75 Momentum, “Matched Savings for Youth”; Peariso, “Youth Fair Gains.” ; Matched Savings for Adults 76 76 Momentum, “Matched Savings for Adults.” ; Savings Challenge 77 77 Information provided by Momentum. ), Burnside Gorge Community Association (Family Self Sufficiency Program 78 78 Information provided by Burnside Gorge Community Association. An additional asset-development opportunity exists for those living in subsidized non-profit housing. If their household income increases (and rent goes up) during the program, an escrow savings program will kick in: the difference between their rent rate at the start of the program and the higher rent rate will be set aside by the subsidy provider until the end of the three-year program, up to a cap of $7,500. Not all participants will be eligible for this program as rents do not often change. ), and Family Services of Greater Vancouver (Common Cents 79 79 Family Services of Greater Vancouver, “Coaching and Workshops.” Saving goal not specified. ), often in partnership with credit unions such as Vancity, 80 80 Vancity, “Savings and Investments.” Assiniboine, 81 81 Assiniboine Credit Union, “Asset Building Programs.” and Coast Capital Savings (see Figure 6).

The learn$ave demonstration project

By far the most significant IDA program in Canada was the learn$ave demonstration project, a matched savings pilot program that began in June 2000 and issued its final report in November 2010. In total, the project enrolled 4,802 low-income working adults, including 3,808 participants at three experimental sites set up as a randomized control trial. 82 82 Applicants’ household income could not be above 120 percent of the low income cut-off, and the program included liquid-asset limits to ensure that participants used the program to build new savings rather than moving their existing assets into the high-yielding learn$ave accounts. If an applicant owned a home—which would give him or her access to relatively cheap credit—it could not exceed the median value of homes in the area. Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 9–10, 26. Applicants selected for the program at those sites were randomly sorted into one of three groups: learn$ave plus (who received matching savings credits plus financial-management training and case management), learn$ave only (who received matching savings credits without any additional training), or the control group (who received neither financial management training nor matching credits). 83 83 Leckie, Dowie, and Gyorfi-Dyke, “Early Impacts,” xi.

Most features of the program followed the traditional IDA model closely. Participants opened their learn$ave accounts at partner financial institutions, which included one bank and several credit unions. All learn$ave participants (i.e., not the control group) received basic administrative support, but learn$ave-plus group received more intensive case management and financial-skills training. 84 84 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 15. Financial training was not specific to education and/or small business requirements. Both learn$ave-only and learn$ave-plus participants received three dollars in matching credits for every dollar they deposited and had three years to save. 85 85 The match rate was 3:1 at the three experimental sites, but some other sites offered match rates ranging from 2:1 to 5:1. To combat the risk of participants simply moving existing liquid assets into their learn$ave accounts rather than building a genuinely new saving habit, participants would qualify for matching credits only after making net deposits of at least $10 in each of twelve months (though these did not have to be consecutive). The program also included a match cap—the maximum deposit that would qualify for matched credits—of $250 per month. Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 11. After the project ended, participants could convert their learn$ave accounts into a regular deposit account at the same institution. 86 86 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 12–13.

The demonstration showed that even those with relatively constrained finances can save. Most participants opened an account, saved in it (an average of $1,100 over three years), and used their matched credits. 87 87 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 104. Based on learn$ave participants’ self reports, there was a small but statistically significant increase in the proportion of self-identified savers after the financial incentive expired. The program also helped participants save more regularly, with the combination of credits and services having a modest impact on regular saving. Program participants were more likely to report an intention to save in the future. 88 88 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 69–70. Families did not give up essentials to max out their savings—participation in learn$ave did not lead to increased hardship. 89 89 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 75. Measures of hardship included difficulty meeting expenses, needing to borrow to meet needs, food bank use, bankruptcy, and overdue bills at month forty. Participants also rated their life satisfaction on a scale of one to ten. Nevertheless, there was a significant proportion of participants whose early saving behaviour indicated that they would likely have been able to save without learn$ave’s added incentives; there were also several participants who failed to use all their earned credits. 90 90 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 104.

Policy benefits and disadvantages

The matched savings policy option has the advantage of being highly customizable to the policy goals of various governments. Policy-makers would have the flexibility to determine the program’s match rate—for every dollar deposited by a low-income saver, government could contribute between, say, 50 cents (under a more modest program) and $3 (a more ambitious program)—and match cap. The program could be high-touch, with financial training and intensive case-management services offered to a select group of participants as featured in the conventional IDA model; alternatively, policy-makers could implement something more akin to Help to Save, offering a simple saving match to a broader group. Matching credits could be restricted to long-term investments such as buying a home, starting a small business, or enrolling in post-secondary education, or use of the credits could be unrestricted. Regardless of which model is used, the benefits are simple and easy for all users to understand—“anyone who saves $1 gets $2 from the government,” 91 91 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 3. compared to, say, “depending on your annual income and family structure, you may be eligible for some or all of this new tax credit.”

Matched savings programs can help participants get into the habit of saving if they are designed with the right rules and incentives. Including monthly deposit requirements may help encourage regular and genuinely new saving rather than reallocation of assets. 92 92 See Harvey et al., “Final Evaluation,” 5. The income constraints experienced by poor households mean that policy-makers will have to design withdrawal rules carefully—restrictions should not be so strict that funds cannot be withdrawn if there is a real emergency, and there should be opportunities for both short- and medium-term savings. 93 93 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 54. If the use of matched credits is restricted to certain purposes, there should still be some flexibility and the cash-out process should be made as easy as possible. 94 94 See, e.g., Proactive Information Services, “Matched Savings Programs.” An essential part of program setup is coordinating with different levels and departments of government on asset rules for means-tested programs so as to ensure that asset limits on income-assistance eligibility are not a disincentive to participate. 95 95 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 103; see also Elliot, “IDA Accessibility,” 1–2. It will be difficult to convince a low-income household to sign up for a matched savings program if they believe it could jeopardize their existing benefits.

In addition to the promising results of learn$ave, evidence from other matched savings programs suggests that these programs are effective for building savings habits. In one of the relatively few studies of IDA participants’ longer-term savings outcomes, Loibl et al. found that after controlling for other variables, IDA program completion was a significant predictor of household saving and had a long-term effect on asset accumulation after the program ended, leading the researchers to conclude that “successful IDA program completion may improve the financial dispositions and behaviors associated with long-term savings.” 96 96 Loibl et al., “More than a Penny Saved,” 122. Another study of IDAs found that participants showed stronger habits of saving than comparable non-participants; this habit strength grew over time to peak at nineteen to twenty-four months, approximately the length of most IDA programs. 97 97 Loibl, Kraybill, and DeMay, “Accounting for the Role of Habit in Regular Saving.” American Dream Demonstration participants have also reported in qualitative interviews that the program helped them develop a saving habit. 98 98 Sherraden and McBride, Striving to Save. In the second Saving Gateway pilot, a large majority (71 percent) of account holders made net deposits in at least sixteen of the program’s eighteen months, and three in five (61 percent) saved enough to earn the maximum government match (two-thirds of whom continued to save even after reaching the limit). 99 99 Harvey et al., “Final Evaluation,” 5.

Even small-scale programs run by private non-profit organizations have experienced great success with matched savings programs. Participants in SEED Winnipeg’s Saving Circle experienced a statistically significant increase in money management and budgeting, among other financial behaviours; financial literacy increased as well. 100 100 Proactive Information Services, “Matched Savings Programs,” iii. Participants in both the Saving Circle and SEED’s IDA programs reported that they continued to practice the financial habits (saving, money management) they learned after cash-out and had increased confidence managing their money. 101 101 Proactive Information Services, “Matched Savings Programs,” iv. Momentum surveyed graduates of its matched savings program and found that 92 percent of respondents continued to save after exiting the program, 72 percent had emergency savings of at least $500, and 77 percent contributed to a registered savings account. 102 102 Momentum, “The Impact of Matched Savings.” Almost all (97 percent) responding alumni of Momentum’s Fair Gains program, which helps low-income youth save for post-secondary education, said they still save money every month; 86 percent of alumni reported that their financial situation had improved since they took the program, and 86 percent said they felt confident to deal with a financial emergency. 103 103 Momentum, “Investing in Youth.”

Alumni of more intensive matched savings programs have cited social support from program staff and other participants as one of the most important non-financial factors contributing to their saving success. Graduates of SEED’s matched savings programs, for example, reported that a major strength of the program was the opportunity to work toward their saving goal in a group, the other members of which were in a similar situation and faced the same financial barriers. 104 104 Proactive Information Services, “Matched Savings Programs,” 26. Participants valued the money-management training not just for the skills and habits they learned but also for the social support it provided. Through the training sessions, participants had the opportunity to make friends with others who faced similar barriers and challenges related to living in poverty. 105 105 Proactive Information Services, “Matched Savings Programs,” 32–33. American IDA research has also found that social and psychological factors, not just economic factors, matter when it comes to saving success. 106 106 Sherraden, “Innovations in Asset Building,” 198.

Even the most intensive, IDA-style matched savings programs offer opportunities for cost savings and cost sharing. The combination of private deposits and public match credits leverages participants’ own capital and government investment, stretching both public and private dollars. Depending on the program, administrative costs may be lower, because the accounts are administered through private financial institutions. The free-rider effect that can occur in many social-assistance programs may be reduced in a matched savings system, since a private contribution is required to trigger a public contribution. There may be more opportunities for employers or private third parties to participate in the program given the shared risk and lower administrative cost. 107 107 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 3. Indeed, many IDAs operate as public-private partnerships: governments develop the structure of the programs, non-profit organizations deliver the programs, and banks or credit unions hold participants’ deposits; funding is provided by both government and private sources. 108 108 Loibl et al., “More than a Penny Saved,” 100. Expanding the role of financial institutions in order to streamline the delivery of matched savings programs may be an opportunity for efficiency gains. 109 109 Voyer, “Impacts of a Matched Saving Program.” Banks and credit unions would not incur any extra expenses, since governments would use gambling profits to cover program costs. 110 110 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 44.

The government could reduce costs associated with the high-touch elements of the program by working with organizations that are already embedded in and have built high-touch relationships with their clients and communities, such as tax-filing volunteers, debt counsellors, and financial-assistance programs run by faith-based communities. IDA participants have stated in interviews and focus groups that it was the financial incentive that drew them to apply for the program, but it was the personal support they received that enabled them to succeed. 111 111 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 13. Since this personalized support is both important and expensive, high-touch (and therefore high-cost) services should be carefully targeted to where they will have the greatest impact. 112 112 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 45.

Policy-makers could likewise reduce costs by taking advantage of existing administrative structures. If eligibility for future IDA programs were tied to existing means-tested programs with their own administrative databases, it might be possible to substantially reduce costs associated with recruitment, verification of eligibility, and enrolment. 113 113 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 101–2. Targeted recruitment may help reduce windfall gains. 114 114 For example, Rablen, “The Saving Gateway,” finds that the Saving Gateway program would be effective at increasing assets for credit-constrained agents, but not for those with access to credit.

Streamlining or eliminating the financial-management curriculum is another way to lower costs. One of the somewhat surprising findings of the learn$ave demonstration was that financial-management training had only a small incremental impact on savings outcomes, though participants expressed appreciation for the training. The program evaluation suggests several potential reasons for this result. The act of saving itself—as incentivized by the matching credits—may have been more important than learning about saving. 115 115 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 105. Participants may have already been familiar with the content (many had fairly high levels of education). The training might have been effective for the very people who did not or could not apply. Participants might not have been able to apply the lessons they learned to their everyday financial lives due to economic hardship—institutional barriers rather than lack of knowledge may be more important in shaping saving behaviour. 116 116 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 75. Moreover, while IDAs and other programs that include financial-management training often assume that low-income households have lower financial literacy and are less skilled at practices like budgeting, they may in fact be more skilled than are middle- and higher-income households. 117 117 Loibl et al., “More than a Penny Saved,” 119; SEDI, “Financial Capability and Poverty,” 6.

Despite these cost-saving opportunities, however, intensive matched savings programs tend to be quite expensive to administer. The high costs of getting participants started on the program—recruitment challenges are common, and verifying applicants’ eligibility is a labour-intensive (and thus expensive) process—mean fewer funds end up in participants’ pockets. 118 118 See Leckie, Dowie, and Gyorfi-Dyke, “Early Impacts,” 21. The cash-out process and assistance provided to participants throughout the program also drive up costs. American IDAs, for example, were found to cost $64 per participant per month to administer (i.e., excluding the cost of the match), much more than other major savings products such as 401(k)s. 119 119 Boshara, “Individual Development Accounts.” Feedback from IDA alumni suggests that high-cost services are essential to the program—participants express appreciation for the personalized support, so eliminating the extra services to administer the program through the tax system would likely reduce its effectiveness.

High costs were a significant finding of the learn$ave demonstration: “The estimated cost per additional person prompted to enrol in an education program by learn$ave matched saving credits and services would be fairly high—around $38,000, at best.” 120 120 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 105. The authors note that learn$ave’s per-person price tag appears more reasonable when you consider the corresponding benefits over the long term: a thirty-three-year-old who enrols in additional education as a result of participating in the program needs to experience an earnings boost of only $2,400 per year over the rest of his or her career to cover this cost. The most expensive activities were recruiting participants, processing withdrawals, and case-management services (particularly for learn$ave-plus participants). 121 121 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 94. However, the main reason the cost is so high is windfall gains—outcomes from the control group showed that the program funded many who would have enrolled in education without the added funds they accumulated through the program. 122 122 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 105. Windfall gains are a common policy challenge, since participants in many publicly funded programs self-select: “The most motivated participate and benefit when they might have succeeded on their own without the program.” 123 123 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 3. The total cost of the learn$ave demonstration was $30 million. 124 124 SEDI, “Financial Empowerment,” 6. Even if running a similar matched savings program did not involve any cost savings, provinces’ annual gambling profits run into the hundreds of millions (surpassing $1 billion in several provinces) and would provide ample revenue for a very substantial expansion of the program.

Critics have also raised questions about matched savings programs’ effectiveness at alleviating poverty. As discussed above, the government’s existing low-touch matched savings programs are underused by poorer Canadians. But high-touch, IDA-style programs do not appeal equally to all eligible low-income families—learn$ave participants were younger, had higher levels of formal education, were more likely to be single, were more likely to be employed, had higher incomes, and were more likely to have recently immigrated to Canada. 125 125 Kingwell et al., “Helping People Help Themselves,” 17–19. This is consistent with other IDA and matched savings programs, which have found those with higher levels of education are disproportionately attracted to the program (and are more likely to complete it). 126 126 Loibl et al., “More than a Penny Saved,” 106; Harvey et al., “Final Evaluation,” 3, 137. These findings suggest a new matched savings program might leave some behind, including those who could most benefit from it. IDAs have also been criticized for not paying enough attention to the structural causes of poverty. 127 127 Elliot, “IDA Accessibility”; Feldman, “Saving from Poverty.”

Many participants are unsuccessful at saving. High dropout rates are common in IDAs: almost half (48 percent) of American Dream Demonstration participants were classified as non-savers (they saved nothing or less than $100). 128 128 Feldman, “Saving from Poverty,” 189; Loibl et al., “More than a Penny Saved,” 101. For those participants who do save, it is unclear whether they actually decrease consumption to meet their saving goals. 129 129 Most participants in the Saving Gateway pilot, for example, reported that their contributions did not come from existing savings. At the same time, however, most participants did not report cutting back their spending to finance their contributions, raising questions about where the money for deposits came from. There was, however, a significant link between participation in the program and a reduction in spending on food consumed outside the home (i.e., eating out) among certain participants, namely, the lower-income group and those in rented accommodation. Harvey et al., “Final Evaluation,” 6. Saving in the program does not necessarily prepare participants for other kinds of saving available outside the program, where the return on deposits will be much lower and financial coaching is less readily available. In the Saving Gateway evaluation, for example, participants wondered whether the match rate was the best way to build a saving habit that would persist after the program ended. They noted that the matching credits were quite different from and substantially higher than interest rates that would be available for conventional saving products. 130 130 Harvey et al., “Final Evaluation,” 5.

Evidence is mixed at best as to whether IDAs have a significant impact on asset accumulation or net worth in the long term. 131 131 Feldman, “Saving from Poverty,” 190–91. Though Loibl et al. found a positive association between program completion and household saving, the report also notes that it can’t determine causality: it may be that people who were already savers were more likely to complete the program. 132 132 Loibl et al., “More than a Penny Saved,” 117. There is no statistically significant evidence of any link between participation in Saving Gateway—in which participants did not have to cash out their matched credits by the end of the program—and increased net worth. 133 133 Harvey et al., “Final Evaluation,” 7. At least two follow-up studies of matched savings programs did not find any relationship between program participation and saving. 134 134 Rothwell and Sultana, “Cash-Flow and Savings Practices of Low Income Households”; Tucker, Key, and Grinstein-Weiss, “The Benefits of Saving at Tax Time”; see also Feldman, “Saving from Poverty,” 189. Yet it is important to note the influence of program design on evaluations of net worth. The relatively short time frame of many IDAs and the requirement that participants cash out their savings mean that the long-term impact of the investment purchased through the program will likely not be evident until months if not years after the program’s end. For instance, learn$ave was expected to increase earnings in the long term, but researchers expected that these results, if they were to emerge, could not be observed by the fifty-four-month mark (which turned out to be true). 135 135 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 87. Moreover, IDAs are premised on the assumption that the act of saving itself, rather than just the assets accumulated through saving, benefits the saver. Indeed, research suggests that the habit of saving is linked to improved feelings of accomplishment, financial control, independence, and security, as well as higher levels of perceived financial well-being. 136 136 Leckie et al., “Final Report,” 4; Loibl, Kraybill, and DeMay, “Accounting for the Role of Habit in Regular Saving,” 590; Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Perceived Financial Preparedness, Saving Habits, and Financial Security”; Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Financial Well-Being in America.”

Conclusion

A matched savings program for low-income Canadians is one way to get gambling money out of provincial coffers and (back) into the bank accounts of the poor. Implementing such a program would not be without challenges, as the issues outlined in the previous section make clear. Nevertheless, there are several important advantages to using gambling profits to help low-income families build assets rather than using these funds to supplement income transfers. First, it helps fill the policy gap related to low-income savings incentives described above. Second, this approach avoids the problem of earmarked funds becoming expected funds—casino and lottery profits are a more volatile, less reliable source of provincial revenue than taxes, and an unexpected shortfall could be devastating for those who have razor-thin margins in their household budget and rely on government benefits to pay their monthly bills. If gambling profits fall, providers may not be able to offer matched savings accounts to as many clients or at as high a match rate that year, but no family will find their expected supply of income cut back.

A third, related advantage of the matched savings option is that, because it does not touch the existing income transfers and benefits system, the government is less likely to be tempted to avoid meaningful gambling reform by cutting expenses elsewhere. One of the dangers we hope to avoid is mere cosmetic tweaks that render pointless the very structural transformation of gambling finances that this report urges. If policy-makers put gambling profits in a separate poverty-alleviation fund, but then decrease the amount spent on poverty alleviation from the consolidated revenue fund, nothing will have changed. The government may have moved some money around, but it is still using gambling money to fund its core services. Adopting a matched savings approach would not eliminate this possibility, of course. But real change is possible: governments currently spend relatively little on asset-building for low-income families (compared to income transfers), and the community organizations and financial institutions delivering the matched savings programs would likely welcome an investment in their program, or at the very least have significant learnings to share and potential support to offer.

Option 3: Help build emergency funds by offering prize-linked savings

The government could also use gambling profits to fund a prize-linked-savings (PLS) initiative. PLS programs are offered by both governments and financial institutions in a variety of forms, but all encourage saving by offering participants the chance to win. In a PLS system, the money that would normally be paid separately to each participating savings account as fixed interest is pooled into a single prize fund; instead of earning regular interest, every participating saver has a chance to win. As with a traditional lottery, participants have the chance to hit the jackpot, but every PLS account holder keeps their deposits—the interest is awarded randomly, but the principal is never lost. 137 137 Some PLS products also include guaranteed interest in addition to the prize pool.

Though relatively little-used in Canada, PLS programs are quite popular worldwide. From bank accounts featuring the chance to win a car in Brazil, to prize bonds in Ireland or Denmark, to the “multimillionaire” accounts offered by Pakistani banks, to the Kenya Post Office Savings Bank’s premium bonds, to the special draws for a Mercedes at Oman International Bank, the opportunity to win big has inspired savers across the globe. 138 138 Kearney et al., “Making Savers Winners,” 31–32. This paper will focus on three different PLS programs available in jurisdictions similar to Canada—namely, the United States and the United Kingdom.

In the past decade or so, PLS programs have become a major initiative among American credit unions. Save To Win, the largest of these programs, has seen great success across the United States since its launch by Michigan credit unions and the non-profit Commonwealth (formerly Doorway to Dreams or D2D Fund) in 2009. With only a small deposit of $25, members can open a twelve-month share certificate and earn entries into drawings for prizes, which usually range from $25 to $5,000. Every $25 deposited earns account holders an additional entry into the prize draw, up to a maximum of ten entries each month. 139 139 Save To Win, “Frequently Asked Questions”; Michigan Credit Union League, “Save To Win.” Organizations advocating for improving Americans’ financial security convinced Congress of the policy potential of PLS programs, leading to the passage of the American Savings Promotion Act with broad support in December 2014. 140 140 Cole, Iverson, and Tufano, “Can Gambling Increase Savings?,” 2. This legislation enabled PLS products at the federal level in the United States, paving the way for authorizing legislation at the state level and an expansion of PLS. At time of writing, thirty-three states allowed PLS. 141 141 Commonwealth, “Prize-Linked Savings Policy.”

More recently, American retail giant Walmart introduced PLS to millions of Americans through its highly successful MoneyCard Vault. Customers with a Walmart MoneyCard, a prepaid debit card, can transfer a portion of their balance into the Vault, a free savings feature from which funds cannot be spent directly. Every dollar saved in the MoneyCard Vault earns the saver an entry in the month’s prize drawing, up to a maximum of five hundred entries. There are 1,000 prizes to be won each month: 999 prizes worth $25 each, and one $1,000 grand prize. 142 142 Walmart, “Walmart and Green Dot Unveil First National Prize-Linked Savings Program”; Walmart, “Two Years Later”; Walmart, “Walmart MoneyCard Prize Savings Sweepstakes.” If someone has more than $500 in the Vault, they will still earn only five hundred entries, based on a calculation of average daily balance. This feature prevents cardholders with very large Vault balances receiving a disproportionate share of entries in each draw. In spring 2020, Walmart encouraged MoneyCard holders to deposit their pandemic stimulus checks directly into their Vault, offering waived maintenance fees and quick access. 143 143 PYMNTS, “Walmart to Customers.”

Among the largest and most popular national PLS products are Premium Bonds, offered by Britain’s National Savings and Investments, a government department and Executive Agency of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The program’s history stretches back to UK “Million Adventure” of 1694, which Britain developed to manage its debt from the Nine Years’ War of 1689–1697. A total of 100,000 tickets, sold at £10 apiece, offered their holders £1 each year until 1710. A small percentage of the tickets would win their holders between £10 and £1,000 each year for those sixteen years. 144 144 Watson, “Save Now, Win Later,” 913; Kearney et al., “Making Savers Winners,” 9–12. The current Premium Bonds program officially launched in 1956 to curb inflation and encourage saving in the aftermath of World War II. On the first day of the program alone, eager investors bought £5 million worth of bonds (nearly $218 million in 2020 Canadian dollars). 145 145 National Savings and Investments, “Our Story.” Today, customers can buy prize-linked Premium Bonds from National Savings and Investments for £1 each. The annual prize fund interest rate is 1.40 percent; instead of earning this interest on their bonds directly, buyers have a shot at winning between £25 and £1 million in tax-free prizes each month. Every bond number gets a separate entry in the draw, an incentive to save more. 146 146 National Savings and Investments, “Premium Bonds.”

Policy benefits and disadvantages

PLS programs have proved popular among customers. Credit union members saved almost $200 million—and were awarded $3 million in prizes—in Save To Win’s first decade of operation. Since 2009, the program has expanded from eight credit unions in Michigan to 127 credit unions in sixteen states, with an additional 107 credit unions in nine other states introducing their own versions of PLS products; over 110,000 cumulative individual PLS accounts have been opened, and the average member saved over $2,000. 147 147 Michigan Credit Union League, “Save To Win”; Commonwealth, “Prize Linked Savings in Credit Unions: 2019.” Walmart customers moved more than $2 billion through the MoneyCard Vault after the program’s launch in August 2016. 148 148 Walmart, “Two Years Later.” Premium Bonds are immensely popular in the UK: twenty-one million Britons—almost a third of the country’s population—had nearly £80 million (CA$137 million) invested in these bonds at the start of 2019. 149 149 Barker, “Premium Bonds.” The Million-a-Month Account (MaMa), a PLS program offered by First National Bank in South Africa, was another hugely popular product. Within 18 months of the program’s launch, PLS accounts outnumbered the bank’s regular saving accounts. 150 150 Cole, Iverson, and Tufano, “Can Gambling Increase Savings?,” 3. In fact, evidence from several lab-based experiments suggests that PLS products encourage individuals to save at a higher rate than do accounts offering standard interest. 151 151 Filiz-Ozbay et al., “Do Lottery Payments Induce Savings Behavior?”; Atalay et al., “Saving and Prize-Linked Savings Accounts.”

Studies of PLS products have consistently found that PLS is particularly appealing to low-income savers. Among PLS account holders in American credit unions, 85–93 percent were classified as financially vulnerable: “not regular savers, asset poor, low to moderate income, had high debt, or had no emergency savings.” 152 152 Commonwealth, “Prize-Linked Savings in Credit Unions in 2018.” The relative appeal of Premium Bonds is strongest among lower-income households. 153 153 Kearney et al., “Making Savers Winners,” 12. Tufano, De Neve, and Maynard surveyed Walmart customers and found that respondents with less than $2,000 in assets were two and a half times more likely to express interest in PLS programs than those with $50,000 or more. 154 154 Tufano, De Neve, and Maynard, “U.S. Consumer Demand for Prize-linked Savings,” 117. In an online lab experiment, Atalay et al. found that the introduction of PLS increased total saving and that the result was stronger among participants with the lowest reported income. 155 155 Atalay et al., “Savings and Prize-Linked Savings Accounts.” The strong appeal of PLS among lower-income savers may be related to the low return these savers can expect from conventional interest, particularly if the account is intended to serve as an emergency fund. Compound interest can yield a significant return over time, but those with constrained incomes are likely to have smaller balances and need more liquidity in their savings. 156 156 Tufano, “Saving Whilst Gambling,” 322; Kearney et al., “Making Savers Winners,” 5. Regular interest would provide little more than pocket change for a low-income single mother who’s able to accumulate only $1,000 and needs to withdraw most of it for an emergency car repair after six months. Losing the few dollars she would earn by putting her money in a standard savings account won’t have a noticeable impact on her standard of living. Winning a $1,000 prize, in contrast, would significantly improve her financial situation.

PLS can also help non-savers develop a saving habit. Evidence suggests that PLS products are attractive to those who report low to nonexistent rates of formal saving. 157 157 See, e.g., Kearney et al., “Making Savers Winners,” 18; Cole, Iverson, and Tufano, “Can Gambling Increase Savings?”, 2; Doorway to Dreams Fund, “A Winning Proposition.” The survey conducted by Tufano, De Neve, and Maynard, for instance, found that those without regular savings plans were 70 percent more likely to express interest in PLS. 158 158 Tufano, De Neve, and Maynard, “U.S. Consumer Demand for Prize-Linked Savings,” 117. In Atalay et al.’s experiment, the increase in saving observed after the introduction of PLS was stronger among participants with the lowest reported savings. 159 159 Atalay et al., “Saving and Prize-Linked Savings Accounts.” Another lab experiment, conducted by Filiz-Ozbay et al., found evidence that the appeal of PLS was strongest among those with low bank-account balances. 160 160 Filiz-Ozbay et al., “Do Lottery Payments Induce Savings Behavior? Evidence from the Lab,” 17. A survey of participants in WINcentive, a PLS account offered by the Minnesota Credit Union Network, found that one-third (33 percent) did not save before opening their WINcentive account. The majority (57 percent) of these non-savers said they now save a fixed amount regularly; only 8 percent reported that they still do not save. 161 161 Commonwealth, “WINcentive Savings 2019,” 7. Given their appeal to non-savers, many PLS products are designed to encourage savers to start small and contribute what they can. The minimum Premium Bond investment is £25 (CA$44), manageable even for those with constrained incomes. 162 162 National Savings and Investments, “Premium Bonds.” Opening a WINcentive account requires just $5. Savers earn an entry into the monthly, quarterly, and yearly prize draws with each $25 deposit and can earn up to four entries each month. 163 163 Commonwealth, “WINcentive Savings 2019 Report,” 3. Customers who took advantage of the WINcentive option generally saved more than their comparable counterparts who didn’t use the program. 164 164 Pew Charitable Trusts, “Can Contests Help Fill Americans’ Savings Gap?”

It can be difficult to discern whether observed saving in PLS is genuinely new saving or simply moving accounts from one form of saving to another (i.e., cannibalizing existing saving), but evidence so far points to saving in PLS as new saving. High rollover levels—account holders reopening their certificates of deposit after the original twelve-month term ends—also point to the potential of PLS products to incentivize long-term saving. 165 165 Watford, “Save Now, Win Later,” 911. Indeed, the introduction of PLS may encourage other kinds of saving as well. At least two recent studies have found that offering PLS increases saving in both PLS and conventional savings accounts. Cole, Iverson, and Tufano’s analysis of account-level data on First National Bank’s MaMa program supports this result: “We do not see any evidence that the MaMa program cannibalized savings, and instead find the reverse: branches with higher MaMa usage also saw expansion of regular savings, and individuals who opened MaMa accounts typically increased their balances in standard savings accounts. Evidence from the random awarding of prizes suggest that these relationships may be causal.” 166 166 Cole, Iverson, and Tufano, “Can Gambling Increase Savings?,” 37. Similarly, Jindapon, Sujarittanonta, and Viriyavipart find that the introduction of PLS increases saving in both PLS and traditional savings (TS) vehicles: “When subjects are allowed to save in a PLS account in addition to a TS account, most of them choose to save in both. Most importantly, their total savings increase.” 167 167 Jindapon, Sujarittanonta, and Viriyavipart, “Prize-Linked Savings Games.”