Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the advisory panel members, Angus Reid, Shachi Kurl, Mag Burns, Lisa Richmond, and Andrew Bennett for their various contributions to this report and expertise given throughout this project. This work has been generously supported by the Canadian Bible Society and the John & Rebecca Horwood Fund.

Testing (Naomi)

Executive Summary

This paper builds on previous research on faith in Canada conducted in partnership with the Angus Reid Institute and explores the role of faith in Canadians’ lives and their relationships to faith communities and public life since 2017. In undertaking this study, we compiled data from nine representative surveys of the Canadian population to paint a broad picture of the past, present, and future of spirituality across the country with the hope of equipping faith leaders and strengthening faith communities and their role as social institutions in society.

The substance of this paper was prepared in the spring of 2022, and a summary of the findings was formally presented to nine groups of religious leaders across the country, for discussion and feedback. Each gathering was intentionally composed of leaders from a variety of Christian churches or denominations, and some included leaders from other faiths as well, although approximately 90 percent of the attendees overall were Christian. A summary of the themes and analysis we heard in these discussions is included in this paper.

These reported trends are not intended to be the final word on faith in Canada, but rather to start an ongoing dialogue about how to navigate a rapidly shifting spiritual landscape in Canada. In this way, this report aims to be a tool for faith leaders and communities that also helps inform them about what kinds of tools they should have in their toolbox.

The paper ends with a discussion for faith leaders on areas of opportunity and future challenges. We do not propose a roadmap back to the previous role of religion in Canada, but rather suggest that in building a greater, more nuanced understanding of the journey of faith of our congregants, communities, and fellow Canadians, perhaps we can be better prepared in finding our footing as models and ministers of the common good among institutions, government, and society.

Introduction

In 2022, Canadians’ relationship to faith, spirituality, and organized religion cannot be described as a linear path but rather is better categorized as a journey of faith that is continually shifting over time. At the core, certain key questions highlight Canadians’ complicated journey of faith: How have Canadians’ understanding of God or a higher power changed over time? Are Canadians practicing religion in a public and private manner today? Are Canadians who identify as religious public about their faith? How do Canadians view faith communities that are different from their own? What factors draw Canadians toward and away from religion? Not everyone who was born in a religious tradition stays in that tradition, but neither do those who were born in a non-religious background. In the midst of this two-way traffic and journey of faith, what can be said about the future of faith institutions and their impact in the public square?

In exploring these questions, Cardus maintains that faith is a core part of human life. Every Canadian has a belief system that guides how they make sense of the world around them, and previous studies have shown how these beliefs predict people’s behaviour. So, while this paper may be of particular interest to faith leaders, it also has important implications for all Canadians.

Canada’s religious landscape remained largely unchanged from the mid-nineteenth century until the end of World War II, when the majority of Canadians identified as Roman Catholic or Protestant. Previous research has explored how Canada’s religious landscape has changed shape through the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s, which weakened the Catholic Church’s influence over social institutions; rising secularization; and an increasing number of immigrants from countries in which Christians are in a minority. 1 1 R.W. Bibby and A. Reid, Canada’s Catholics: Vitality and Hope in a New Era (Ottawa: Les Éditions Novalis, 2016): 33, 35; S. Wilkins-Laflamme, “How Unreligious Are the Religious ‘Nones’? Religious Dynamics of the Unaffiliated in Canada,” The Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie 40, no. 4 (2015): 478; L. Cornelissen, “Religiosity in Canada and Its Evolution from 1985 to 2019,” Insights on Canadian Society, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 75-006-X, October 2021, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2021001/article/00010-eng.htm. While Statistics Canada data indicates an increasingly diverse religious landscape and a growing number of Canadians who have no religious affiliation (23.9 percent in 2011 versus 12.5 percent in 1991), 2 2 Statistics Canada, “2011 National Household Survey, Table no. 99-010-X2011032,” https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/99-010-X2011032; Statistics Canada, “1991 Census, R9101—Population by Religion,” https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/English/census91/data/tables/Rp-eng.cfmANG=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=1&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=1&GC=0&GID=0&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=66&PRID=0&PTYPE=4&S=0SHOWALL=No&SUB=0&Temporal=1991&THEME=114&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=. Cardus’s research has illustrated that the religious affiliation Canadians report may not be an accurate depiction of their overall spirituality, religious beliefs, or practices. Over the past five years, Cardus has worked with the Angus Reid Institute to develop a tool not only to understand these shifts away from religious life but also to identify where these shifts are taking place within and between religious groups in terms of personal and group spiritual beliefs and religious activities.

Several macro-scale theories and their supportive evidence have been presented in social-science research to explain why Western societies are moving away from religion and organized religious activities altogether as well as the reasons for a “shrinking middle category” of those who are religiously affiliated but are less likely to fall on one of the two ends of the religious spectrum. 3 3 For example, see J. Thiessen and S. Wilkins-Laflamme, None of the Above: Nonreligious Identity in the US and Canada (New York: New York University Press, 2020). That said, on a micro-scale, there is a lack of understanding about the push-and-pull factors within faith groups and the journey to and away from faith in Canada. What factors draw Canadians to a faith group, and what pushes them away from their childhood religion? How might being raised in a religious tradition predict their religiosity?

Cardus’s research is dedicated to filling these gaps, with the aim of fostering a greater commitment to pluralism in public life for the flourishing of Canadian society. This analysis will first evaluate the most recent Spectrum of Spirituality index results from 2021 to 2022, particularly focused on each religious indicator by sociodemographic characteristics and religious affiliation, and then present a broad overview of how the seven Spectrum indicators have changed since the index’s inception. The study will also explore individuals’ journey from the faith tradition they were raised in to their current religious identity, followed by a brief look at correlations between religiosity and their answers to questions about faith in the public square.

Methodology

This study draws from nine online surveys (two of which had two separate field samplings resulting in eleven survey rounds) ranging from 1,290 to 5,003 respondents per survey. These surveys were not intended to be longitudinal in their initial phases, which has resulted in slight changes in wording to questions and weighting judgments between different snapshots. While some real shifts appear to be occurring in a brief span of five years, we acknowledge that further research is needed to determine both whether these trends are long-lasting and how concrete these shifts are. Although careful readers will find slight variances between this report and each of the previous reports publicly available online, almost all those differences are slight, and therefore the conclusions and narrative presented in this report can be validly backed by the data. For comparison purposes only, a detailed overview of each survey’s representative sample size and margin of error has been included in the appendix.

The substance of this paper was prepared in the spring of 2022, and a summary of the findings was formally presented to nine groups of religious leaders for discussion and feedback. One gathering was held in May 2022 in Ottawa, with about fifty faith leaders attending, and eight regional gatherings were held between May and September 2022, with about twenty-five leaders at each one. The regional gatherings were held in Vancouver, Langley, Calgary, Saskatoon, Hamilton, Toronto, Montreal, and Halifax. Each gathering was intentionally composed of a variety of leaders from Christian churches or denominations, and some included leaders from other faiths as well, although approximately 90 percent of the attendees overall were Christian.

Summary themes and analysis from these sessions are featured on yellow pages throughout this document, based on our notes. Where we present direct quotations, our intent is to pass along what we consider to be a particularly memorable comment. While we are confident that these quotations are substantively accurate, the exact wording may have been slightly different.

The Spectrum of Spirituality Index

The Spectrum of Spirituality was developed in 2017 by Cardus and the Angus Reid Institute to highlight the nuances of personal faith and public faith within religious affiliations and to recognize that a range of commitments and practices exists both within and between religious groups. Although there was some other publicly available data focused on individual religious beliefs and practices, relatively little attention had been given to how religious individuals and institutions influence the public square and how they are understood by others. The index was created to help understand religion in Canada along a spectrum of commitment, rather than a binary religious-secular divide. Drawing from previous social-science research on key indicators of spirituality, the Spectrum contains seven spiritual indicators that are split between personal and public religious practices and beliefs:

- Belief in God or a higher power

- Belief in life after death

- How important it is for a parent to teach their children about religious beliefs

- How often, if at all, a person feels they experience God’s presence

- How often, if at all, a person prays to God or a higher power

- How often, if at all, a person reads the Bible, Qur’an, or other sacred text

- How often, if at all, a person attends religious services (other than weddings or funerals)

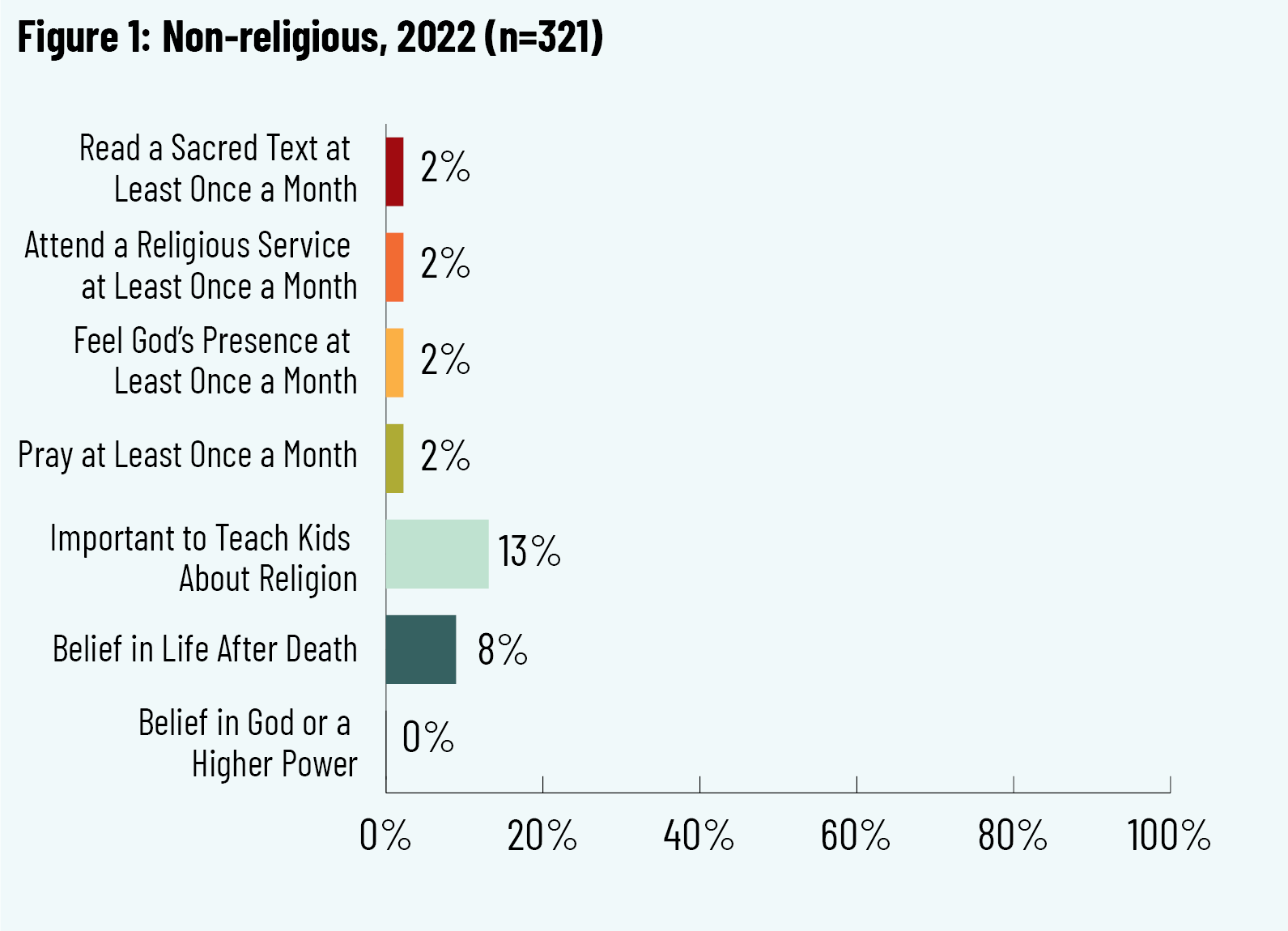

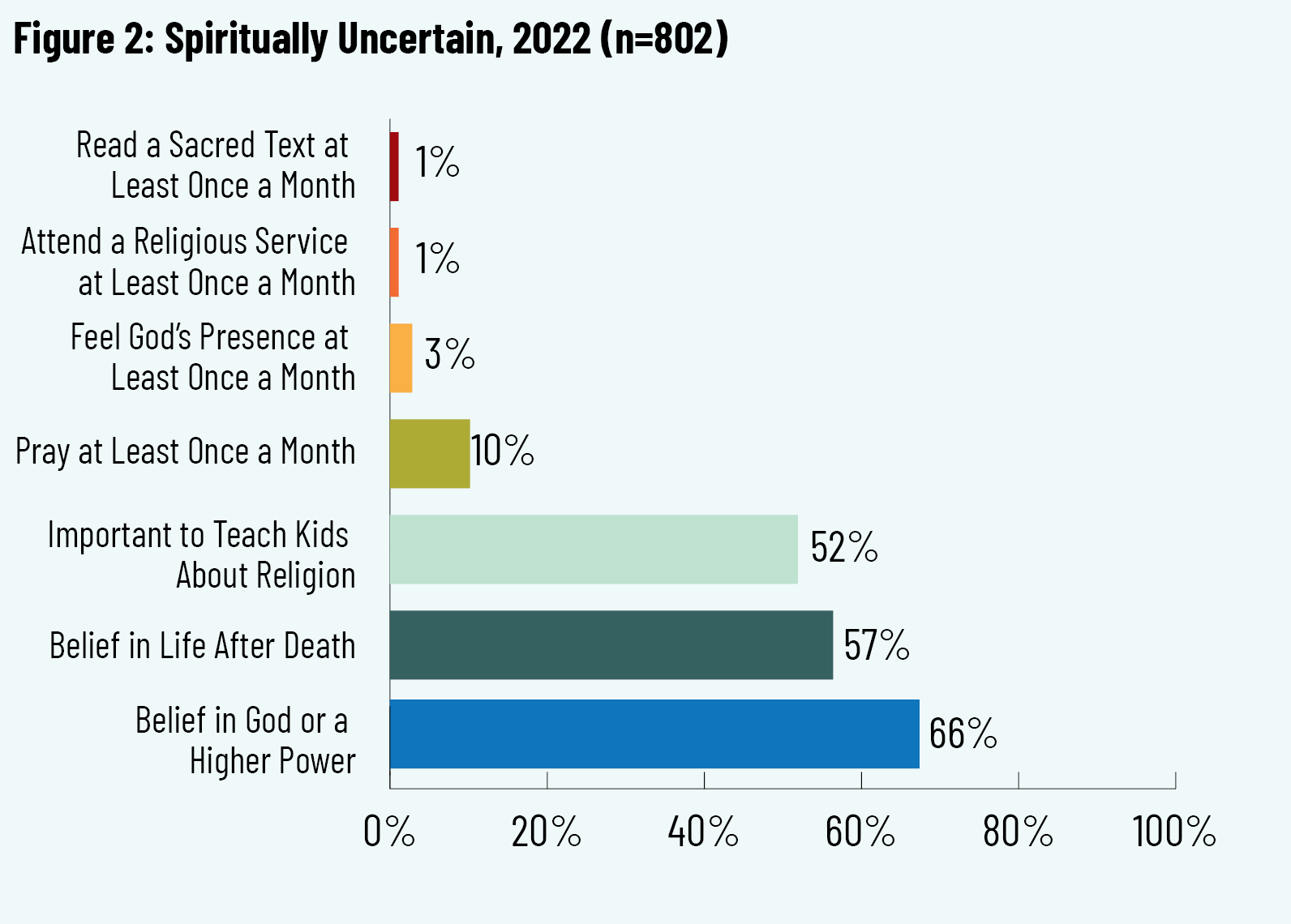

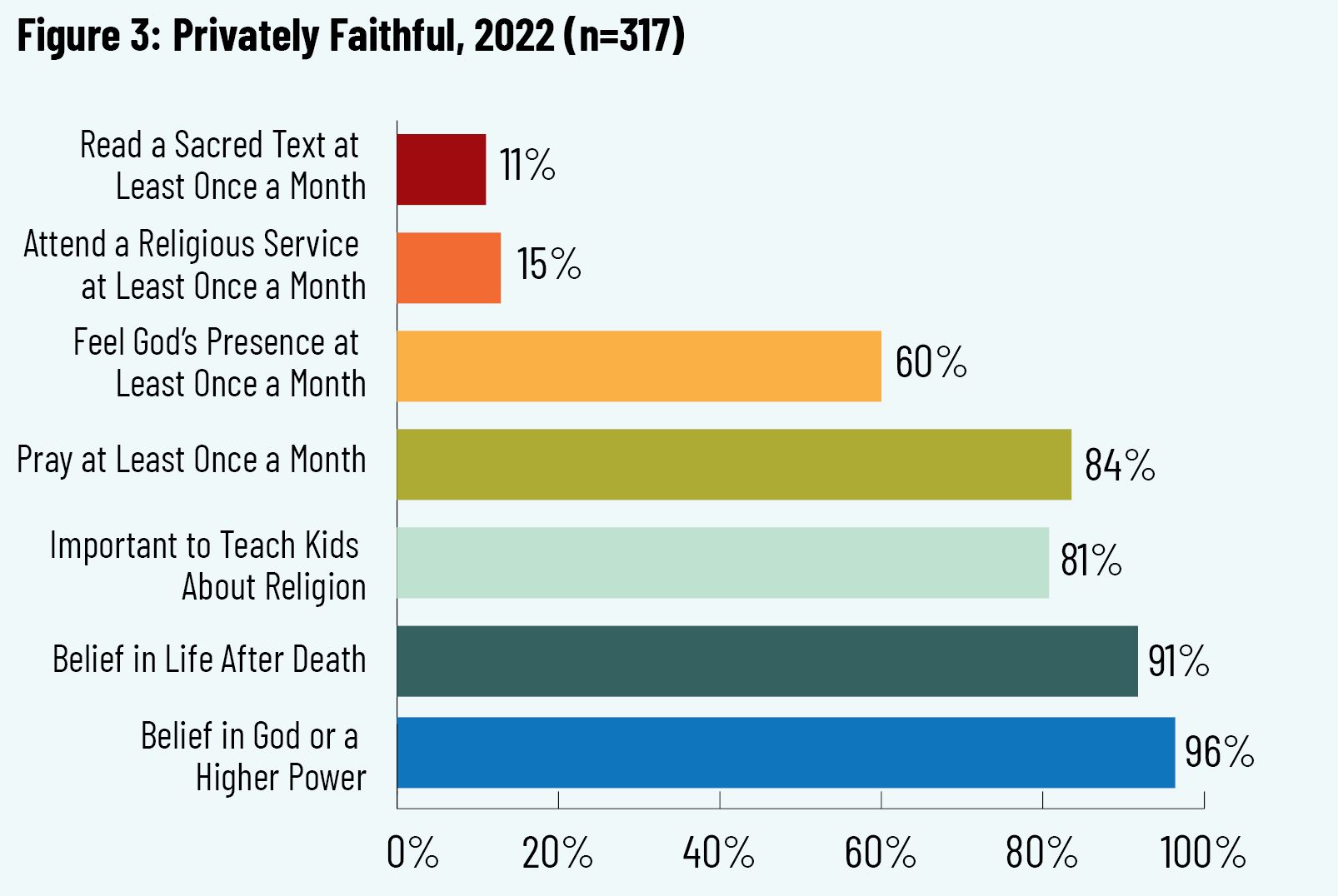

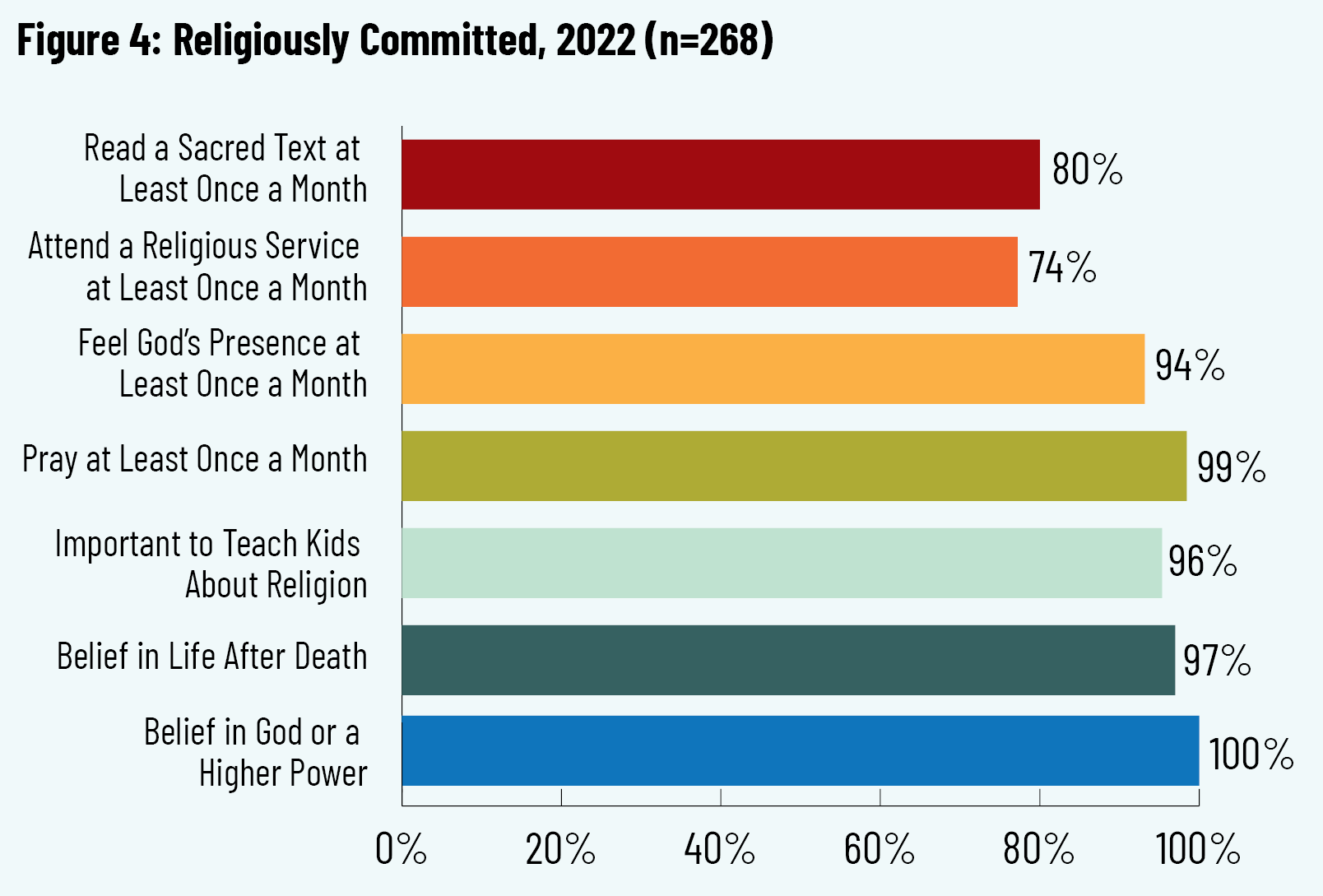

Higher scores in each indicator indicate a higher commitment to religion in everyday life, whereas lower scores suggest a lesser degree of religious practice, if any at all. Four groups emerge from the index, with each of the seven indicators weighted equally: Religiously Committed, Privately Faithful, Spiritually Uncertain, and Non-religious. 4 4 An eighth question was also asked to respondents who indicated they do not think or do not believe God or a higher power exists about their feelings of faith or spirituality. Those who reported no feelings of faith or spirituality are given a negative score of 100 and almost always fall within the Non-religious category. For a full list of these indicators, see the appendix. These labels have been assigned according to the total composite score received on these indicators.

A Portrait of Spirituality in 2022

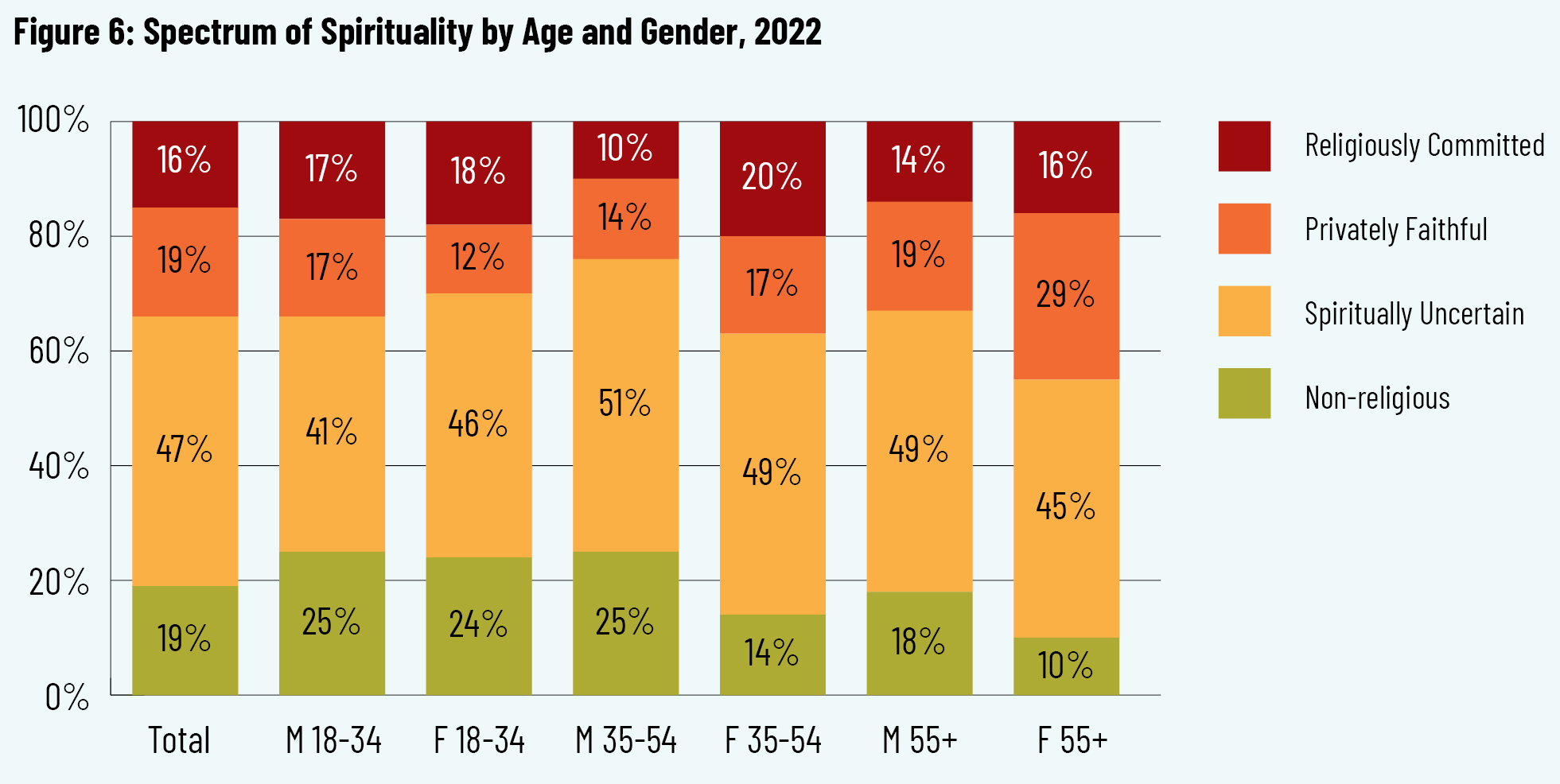

A brief snapshot into where Canadians land in their spirituality from 2017 to 2022 suggests a shift among younger Canadians, women, and certain income earners since 2017. 5 5 For a complete list of reports released in partnership with the Angus Reid Institute, see Cardus, “Research with the Angus Reid Institute,” 2022, https://www.cardus.ca/research/spirited-citizenship/research-with-the-angus-reid-institute/.

- Religiously Committed (n=268, 16 percent of the total population):

- This group is more likely to be female than male (58 percent versus 42 percent) and aged fifty-five years and older (37 percent).

- They are also the most public about their faith (92 percent).

- About one in four (26 percent) are immigrants and seven in twenty (34 percent) are visible minorities, the highest percentages among all groups. Immigrants are twice as likely as those born in Canada to find themselves in this category (28 percent versus 14 percent).

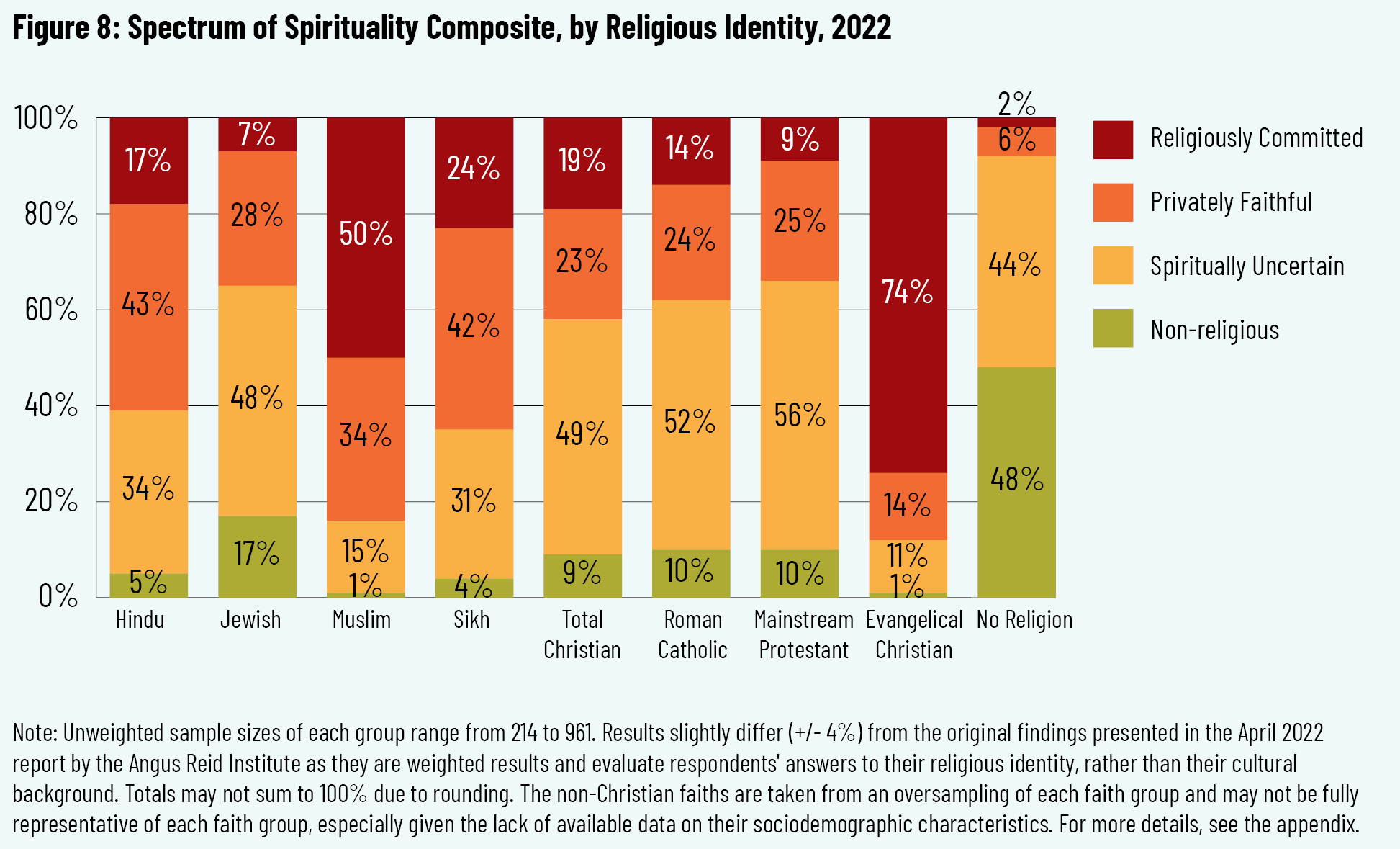

- Almost three in four (74 percent) of Canadians who identify as Evangelical Christians and one in two (50 percent) Muslims find themselves here, in contrast to slightly under one in ten (9 percent) Mainline Protestants and three in twenty (14 percent) Roman Catholics.

- Privately Faithful (n=317, 19 percent of total population):

- Nearly three in ten (31 percent) in this group are women aged fifty-five years and older, an increase of 8 percent since 2017.

- Around one-third (32 percent) have an annual household income of less than $50,000, the highest percentage of lower income earners in the index.

- More than two in five Sikhs (42 percent) and Hindus (43 percent) are found here.

- Spiritually Uncertain (n=802, 47 percent of total population):

- Nearly half (49 percent) of native-born Canadians are in this group.

- The composite remains about evenly distributed among all genders and annual household incomes.

- Over half (54 percent) of Canadians who were not raised in a faith tradition are found here, compared to 44 percent of those who were.

- About 50 percent of all Jews (48 percent), Roman Catholics (52 percent), and Mainline Protestants (56 percent) are Spiritually Uncertain.

- Regionally, nearly three in five (57 percent) Quebec residents are here.

- Non-religious (n=321, 19 percent of total population):

- This group has the highest percentage of younger Canadians: 46 percent of this group are between the ages of eighteen and forty.

- Over half (58 percent) of this group is male.

- About seven in twenty (36 percent) have a household income of more than $100,000 a year, which is an increase of 15 percent since 2017.

- Since 2017, the percentage of women aged 18 to 34 who find themselves here has increased by 8 percent, from 16 percent in 2017 to 24 percent in 2022.

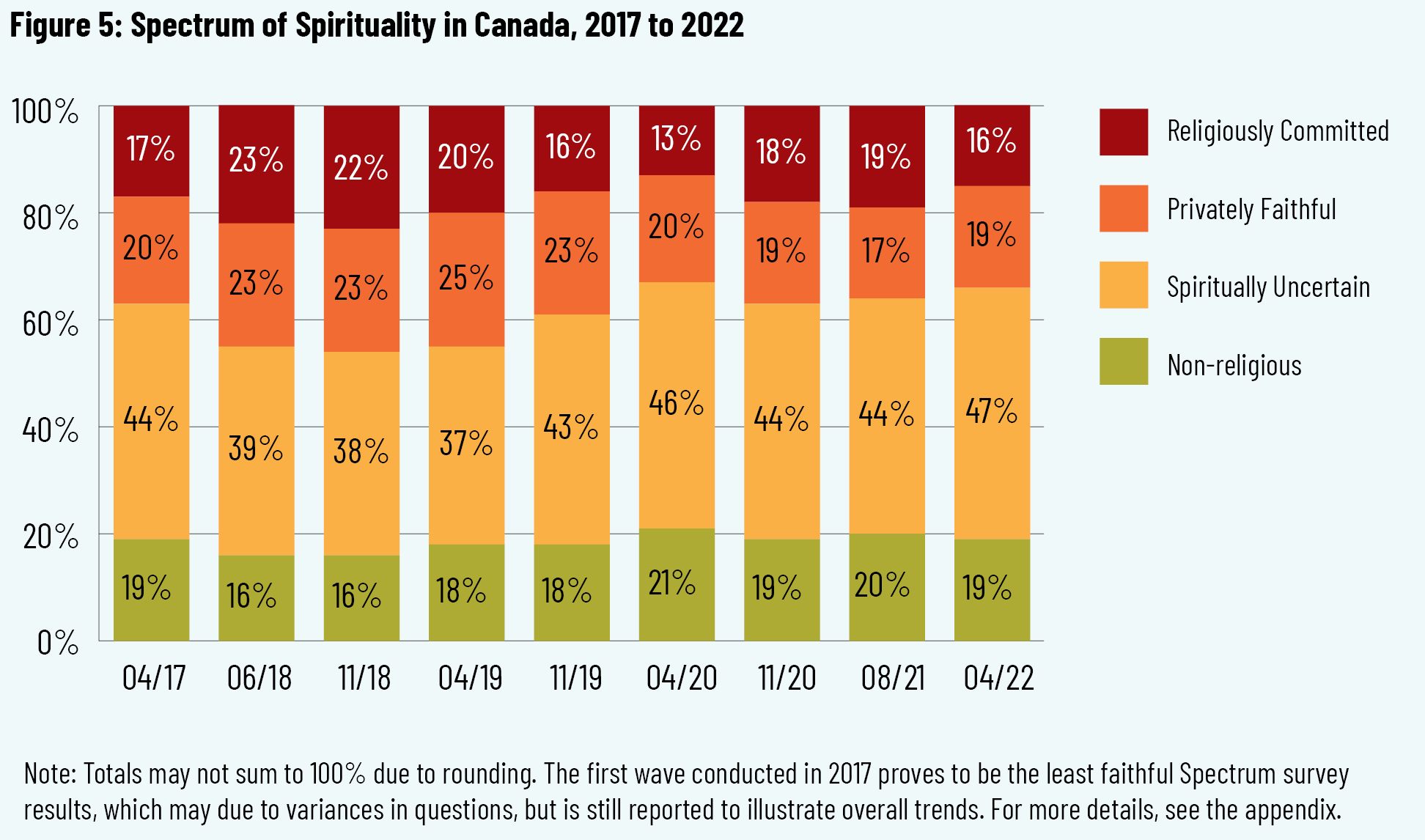

Canada’s Spiritual Landscape: 2017 to 2022

While the percentage of Canadians who find themselves in the Religiously Committed and Privately Faithful categories has been in overall decline since the Spectrum’s inception, the Spiritually Uncertain group has seen the largest growth of any group since the index was initiated, increasing from 39 percent of Canadians in 2018 to nearly half (47 percent) of the Canadian population in 2022. Although there are certain shifts in these indicators relating to the COVID-19 pandemic, the cause of these changes is beyond the scope of this paper.

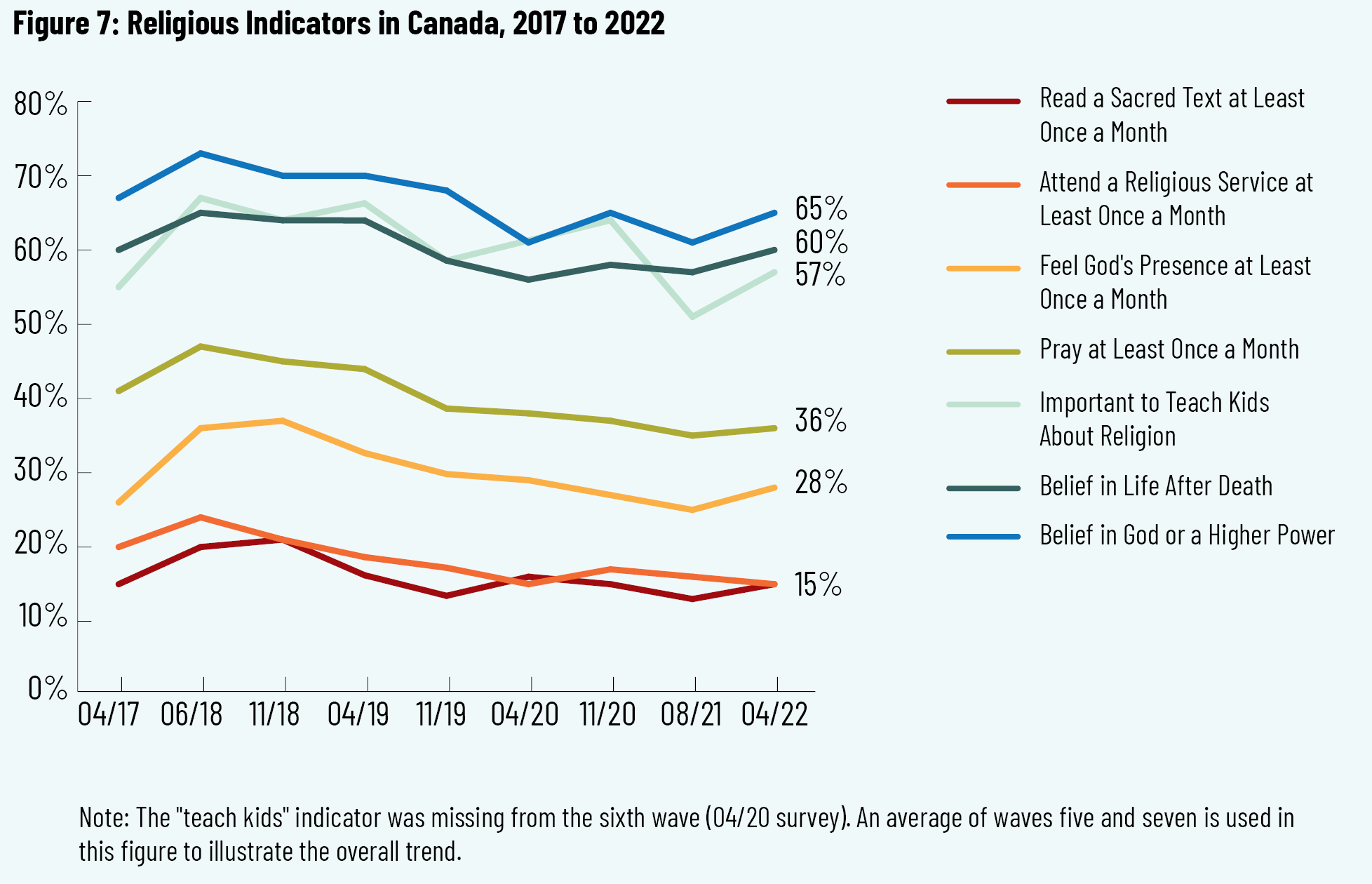

While there has been an overall decline in Canadians who land on the religious end of the continuum, a closer look reveals that certain religious indicators have seen slight increases, while others faced much sharper declines. Though all religious indicators among Canadians surveyed are lower than they were in 2018, there has been a slight increase in personal spiritual beliefs since April 2020, a reversal in the overall declining trend. More Canadians expressed belief in life after death in 2022 than they did two years ago (56 percent in April 2020 versus 60 percent in 2022).

Public and individual religious practices are particularly declining in Canada: about 46 percent of Canadians indicated they pray at least once a month in 2018, compared to 36 percent in 2022. From 2020 to 2022, around 16 percent of Canadians said they attend a religious service other than a wedding or funeral once a month or more, compared to about 22 percent in 2017 to 2018. Over three-quarters (85 percent) of Canadians in 2022 suggested they read a sacred text a few times a year or less often, while nearly three in five (57 percent) thought it is important for parents to teach their children about religion. These results suggest that most Canadians score higher on indicators of personal spiritual beliefs than they do on group or individual religious activities.

Belief in God or a Higher Power

As previous research revealed, younger Canadians under thirty-five years of age are less likely than their older counterparts to believe in a higher power (57 percent versus 67 percent in 2022). Women aged thirty-five years and older tend to have this belief (73 percent do), as well as Canadians with a household income of less than $50,000 a year (70 percent do). Polling suggests that belief in God or a higher power has increased since 2020 for some Canadians, bouncing back from an initial decline in 2019 and reversing the overall trend. This rebound is particularly evident in men under thirty-five years of age, whose belief in God or a higher power jumped from 46 percent in April 2020 to 56 percent two years later, as well as women aged thirty-five to fifty-four years, who polled at 63 percent in 2020 versus 70 percent in 2022.

Regionally, the number of Quebec residents who share a belief in God or a higher power has steadily declined from 61 percent in 2017 to 51 percent in 2022. Those who live in British Columbia and Quebec typically have the highest percentage of residents who do not believe in God or a higher power (37 percent and 49 percent, respectively in 2022).

Belief in Life after Death

Results from the August 2021 survey show that immigrants who arrived in Canada more recently are more likely to believe in life after death than those who have lived in Canada for a longer period. About half (54 percent) of immigrants who have lived in Canada for twenty-one years or more hold this belief, compared to 66 percent of more recent immigrants. Over one in two (51 percent) of Canadians who were not raised in a faith tradition indicated they do not believe in life after death, compared to 35 percent of those who were raised in a religious background.

The largest increase in belief in life after death since November 2019 has been among female Canadians aged thirty-five to fifty-four, who polled at 66 percent in that survey and at 73 percent in 2022.

In 2022, income earners of $100,000 a year or more are less likely to believe in God, at 56 percent, compared to 65 percent of those who have a household income of less than $50,000 a year. This belief has increased among all income levels since the survey was conducted in April 2020, with the most growth among the lowest income earners (58 percent in 2020 versus 65 percent in 2022). For Canadians who have a university degree or more education, belief in life after death remained at 51 percent from November 2019 to 2021 and increased to 59 percent in April 2022. In contrast to the other religious indicators, these slight increases among age groups, income levels, and education level are a reversal of the overall decline trend found in most of the Spectrum indicators.

Importance for Parents to Teach Their Children Religious Beliefs

Canadians surveyed aged fifty-five years and older indicated the highest agreement among other age groups about the importance of teaching children about their religious beliefs (69 percent compared to 45 percent of Canadians younger than thirty-five years of age). Declines in this belief are prominent among younger Canadians under thirty-five who polled at around 54 percent from 2017 to 2018 to 45 percent in 2022.

Three in four (76 percent) who are unaffiliated with a religion suggested they do not think it is important for parents to teach their kids religious beliefs in 2022. Across Canada, 51 percent of Atlantic Canada residents also share this sentiment, the highest percentage among all regions. On the other hand, Canadians who reside in Alberta are most likely to agree that it is important for parents to teach their kids about faith beliefs, at 67 percent, compared to 57 percent of the total population.

Those raised in a faith tradition are more likely than those who are not to convey agreement with this dimension: 61 percent of those raised religious are in favour of parents teaching their children religious beliefs, compared to 47 percent who were not.

How Often a Person Feels They Experience God’s Presence

Men aged thirty-five to fifty-four are less likely than any other age and gender group to feel God’s presence: more than half (56 percent) suggest they have never felt God’s presence, followed by 48 percent of men and women under the age of thirty-five.

Immigrants to Canada are more likely than those born in the country to express a higher occurrence of feeling God’s presence: 45 percent indicate they have this experience at least once a month, compared to a quarter (25 percent) of Canadian-born respondents. Over half (53 percent) of Quebec residents indicated they never experience God’s presence in 2022, as well as 49 percent of those who earned more than $100,000 annually in contrast to 37 percent of the lowest income earners.

Frequency of Prayer to God or a Higher Power

In 2022, 36 percent of the Canadian population reported that they pray once a month or more, with more than half (53 percent) praying rarely or never. Based on the 2022 survey results, women are more likely than men to frequently pray to God or a higher power (42 percent versus 30 percent), as well as Canadians aged fifty-five years and older compared to their younger counterparts (41 percent versus 33 percent).

Almost half (49 percent) of women aged fifty-five years and older conveyed they pray at least once a month. The opposite is true for men aged thirty-five to fifty-four: nearly half (46 percent) never pray. Interestingly, over half (56 percent) of immigrants indicated they pray at least once a month, compared to 33 percent of native-born Canadians.

Since April 2020, the largest increase of Canadians who indicated they pray at least once a month is among men under thirty-five years old: men in this group polled at 33 percent in 2022, an increase from 21 percent in 2020.

Frequency of Reading Bible, Qur’an, or Other Sacred Texts

In 2022, 15 percent of Canadians say they read a sacred text at least once a month, while half of the population (56 percent) report they never read a sacred text. Regionally, 73 percent of Quebec residents fall into this category—the highest percentage in Canada of those who never read a sacred text.

In our 2022 survey, men and women under thirty-five years old are more likely to read a sacred text once a month or more than other age groups (20 percent do). Canadians between the ages of thirty-five to fifty-four are less likely to read these scriptures (about 61 percent never read a sacred text) than any other age group. Men aged thirty-five to fifty-four have the lowest percentage of monthly reading compared with other cohorts (at 9 percent in 2022 and 20 percent in 2018).

Canadians who make $100,000 or more a year tend to read scriptures the least amount in comparison to other income earners: 60 percent say they never read a sacred text, compared to 51 percent who earn less than $50,000 a year. Overall, these numbers have not changed significantly across gender, education, age, and income levels since Cardus and the Angus Reid Institute started polling in 2017.

Frequency of Attending Religious Services

In 2022, about 15 percent of the Canadian population indicated they attend a religious service other than weddings and funerals at least once a month, a decline from 24 percent in June 2018. Those raised in a religious tradition are more than twice as likely than those not raised in a faith background to attend a religious service at least once a month (18 percent versus 7 percent). The same can be said of immigrants compared to native-born Canadians (28 percent versus 13 percent). In 2022, 8 percent of Canadians who identified their religion as Jewish and 15 percent of those who identify as Christians attend religious services weekly or more often. Of those who identify as Christian, 9 percent of Roman Catholics, 7 percent of Mainline Protestants, and 59 percent of Evangelical Christians reported they attend religious services at least once a week. Over one in four (27 percent) of those who identify as Muslim attend religious services weekly or more often.

Of note, there has been a slight increase in men under thirty-five years who attend religious services once a month or more (from 14 percent in April 2020 to 22 percent in April 2022), a reversal of the overall decline trend. While attendance among most age groups has declined overall, younger Canadians are more likely than any other age group to report they attend religious services at least once a month (20 percent compared to 13 percent of Canadians aged thirty-five and older).

Religiosity of Canada’s Main Faith Groups

The Spectrum of Spirituality was designed to highlight a wide continuum of Canadians’ spirituality and help explore how commitment to personal and organized religious practices may be correlated with responses or sentiments to certain issues in public life. The index arguably can apply to most, if not all, of the main religious traditions in Canada, but for some religions that place less emphasis on institutional religious practices or evangelism, such as Hinduism and Judaism, certain index indicators such as religious-service attendance or reading sacred texts may be less applicable in measuring their commitment to faith. Of note, the sixth wave did not ask participants about their religious identity and has been omitted from this analysis, which may slightly affect the results presented in this study.

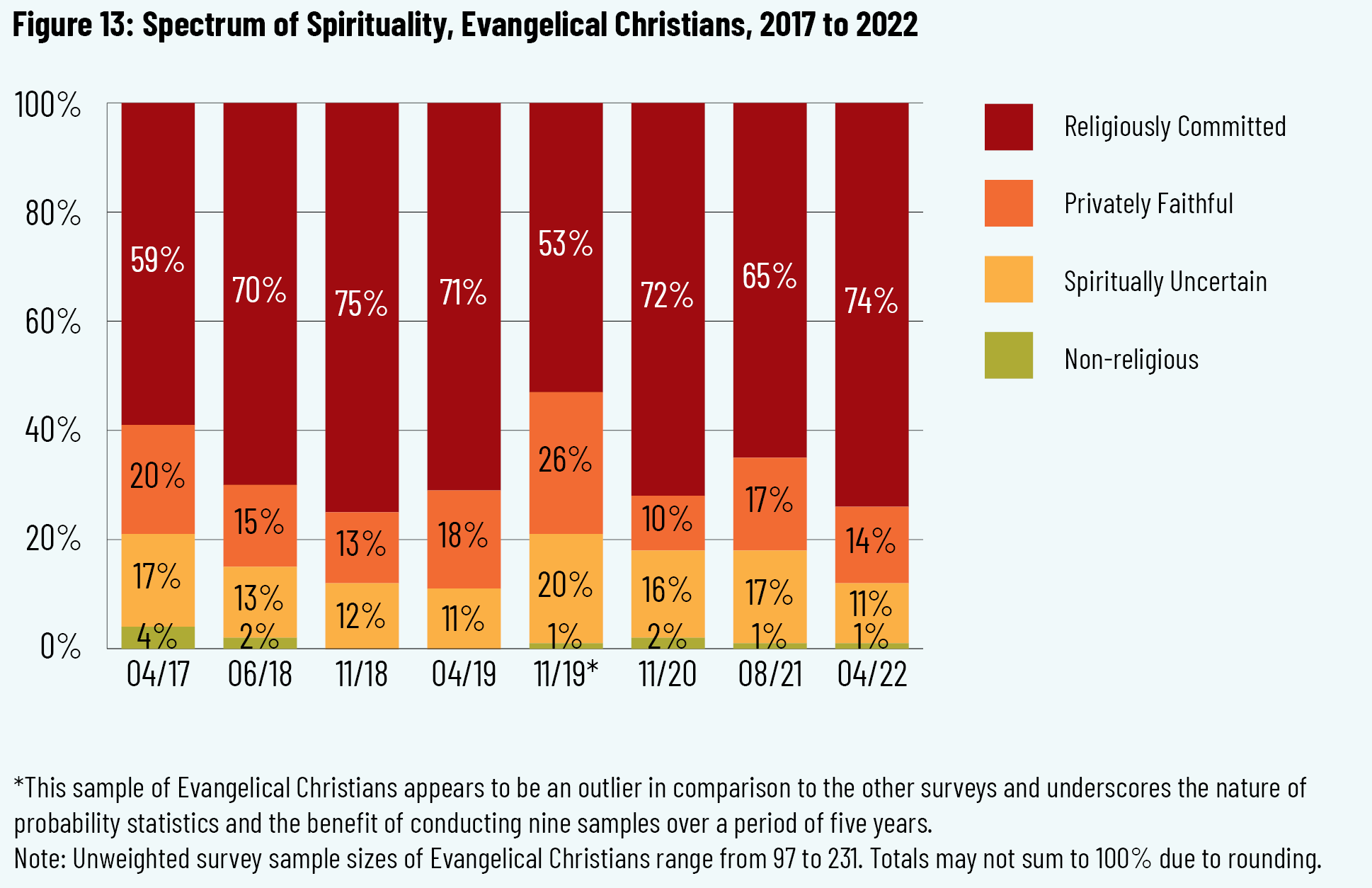

In 2022, 74 percent of those who identify as Evangelical Christian fell into the Religiously Committed group, followed by Canadians who identify as Muslims (50 percent) and Sikhs (24 percent). Canadians who identified their religion as Mainline Protestants have the highest percentage of any other religious group in the Spiritually Uncertain category (at 56 percent), followed by those who identify as Roman Catholics (52 percent) and Jews (48 percent). 10 10 For a full description of these groups, see the appendix.

Roman Catholics

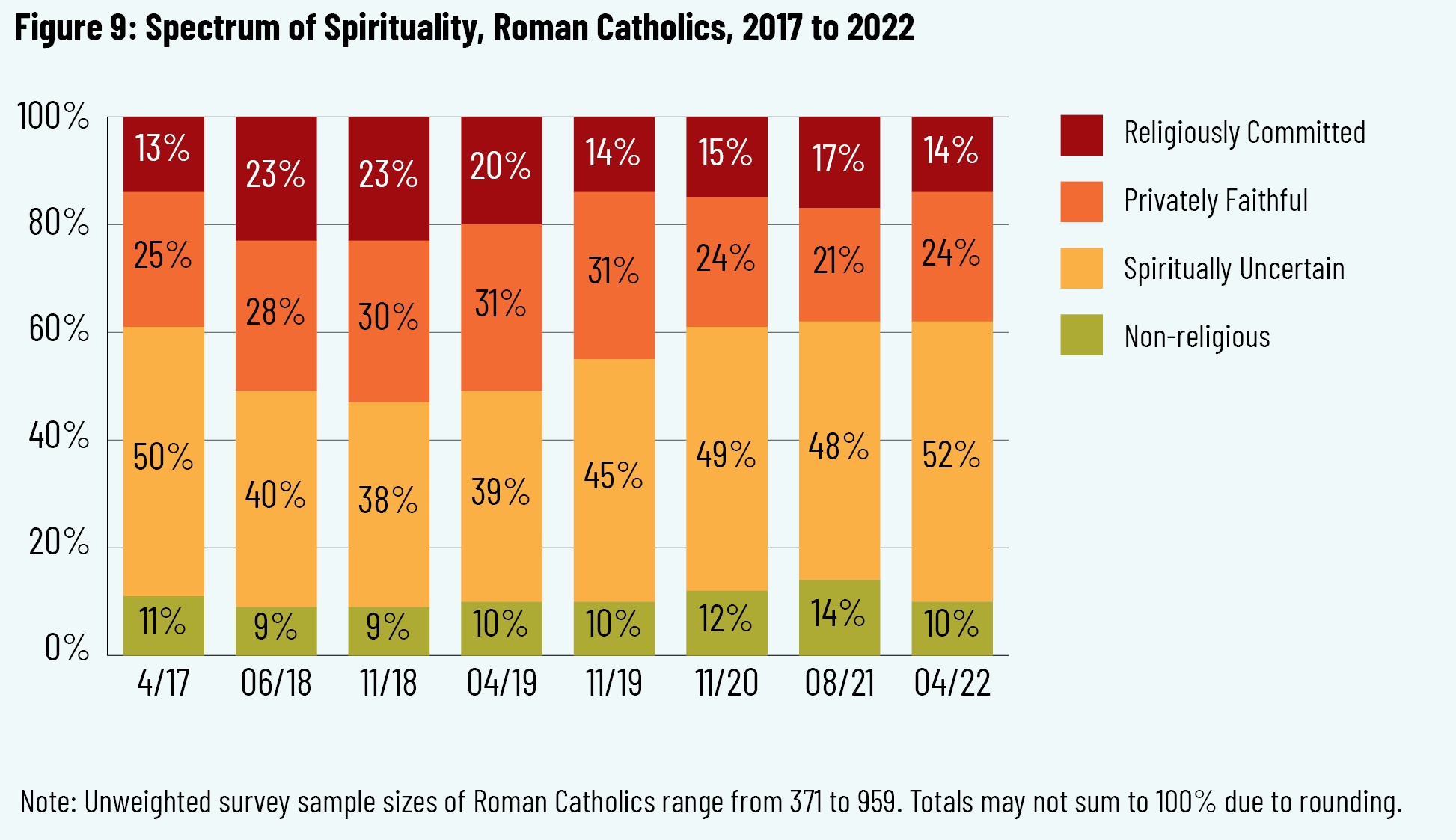

Since 2018, the number of Spiritually Uncertain Roman Catholics has grown from 40 percent to 52 percent in 2022, while those who find themselves in the Religiously Committed and Privately Faithful groups combined have fallen by 13 percent overall.

A profile of Roman Catholics’ religiosity seems to suggest that those under thirty-five years of age score higher on the Spectrum in 2022 in certain private-belief indicators in comparison to other age groups, and score lower in public and individual religious activities. In 2022, younger women who identify as Roman Catholic exhibited a higher percentage of belief in God than any other gender and age group (87 percent do), compared to 84 percent of women aged fifty-five years and older who identify as Roman Catholic and 67 percent of men of the same age and faith.

About 81 percent of young Canadians who identify as Roman Catholic believe in life after death, with 91 percent of female Roman Catholics under 35 years of age having this belief, compared to 60 percent of their senior counterparts. Older males who identify as Roman Catholic are less likely to believe in life after death, with about 48 percent not believing in life after death.

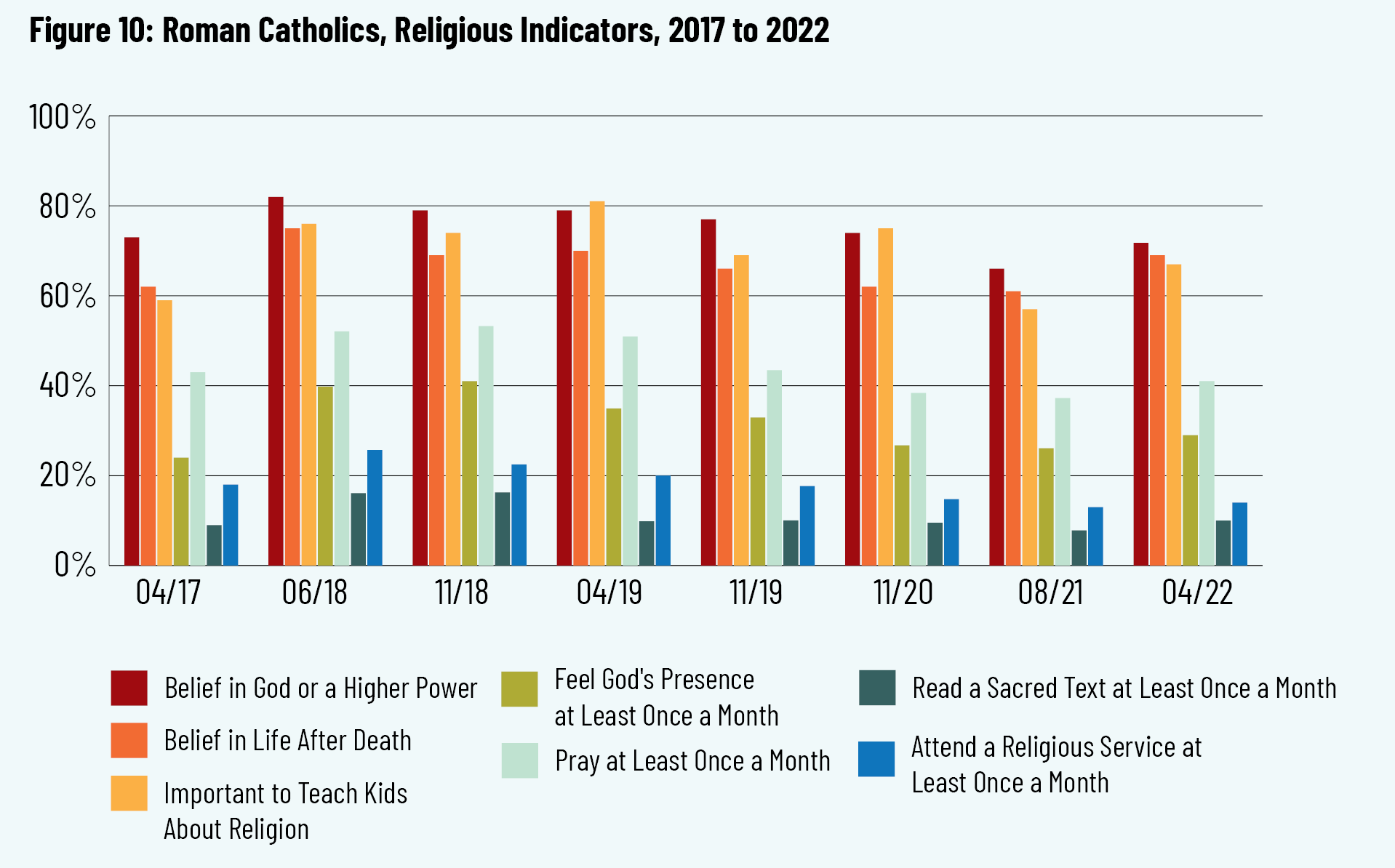

All religious indicators among those who identify as Roman Catholic have declined overall since 2017, with certain exceptions in younger demographics and females. Canadians who identified their religion as Roman Catholic and are under forty years of age are nearly twice as likely as older Roman Catholics to attend religious services at least once a month (23 percent versus 12 percent). Immigrants to Canada in this group are more than twice as likely as those born in Canada to attend religious services once a month or more (32 percent versus 12 percent).

Four in ten (41 percent) of those who identify as Roman Catholic pray once a month or more, compared to about one in two (52 percent) in the 2018 waves. In 2022, 68 percent of immigrants who identify as Roman Catholic pray at least once a month, compared to 37 percent of those born in Canada.

A profile of Roman Catholics’ religiosity seems to suggest that those under thirty-five years of age score higher on the Spectrum in 2022 in certain private-belief indicators in comparison to other age groups, and score lower in public and individual religious activities. In 2022, younger women who identify as Roman Catholic exhibited a higher percentage of belief in God than any other gender and age group (87 percent do), compared to 84 percent of women aged fifty-five years and older who identify as Roman Catholic and 67 percent of men of the same age and faith.

About 81 percent of young Canadians who identify as Roman Catholic believe in life after death, with 91 percent of female Roman Catholics under 35 years of age having this belief, compared to 60 percent of their senior counterparts. Older males who identify as Roman Catholic are less likely to believe in life after death, with about 48 percent not believing in life after death.

All religious indicators among those who identify as Roman Catholic have declined overall since 2017, with certain exceptions in younger demographics and females. Canadians who identified their religion as Roman Catholic and are under forty years of age are nearly twice as likely as older Roman Catholics to attend religious services at least once a month (23 percent versus 12 percent). Immigrants to Canada in this group are more than twice as likely as those born in Canada to attend religious services once a month or more (32 percent versus 12 percent).

Four in ten (41 percent) of those who identify as Roman Catholic pray once a month or more, compared to about one in two (52 percent) in the 2018 waves. In 2022, 68 percent of immigrants who identify as Roman Catholic pray at least once a month, compared to 37 percent of those born in Canada.

The percentage of those who reported their religion as Roman Catholic and never read a sacred text was higher than the percentage of the total population of Canada that never did (60 percent versus 56 percent in 2022). They are also more likely to never read a sacred text than any other major faith group. About 1 percent read their Bible every day and 10 percent read it at least once a month. Conversely, 33 percent of immigrants who identify as Roman Catholic read their Bible at least once a month.

Mainline Protestants

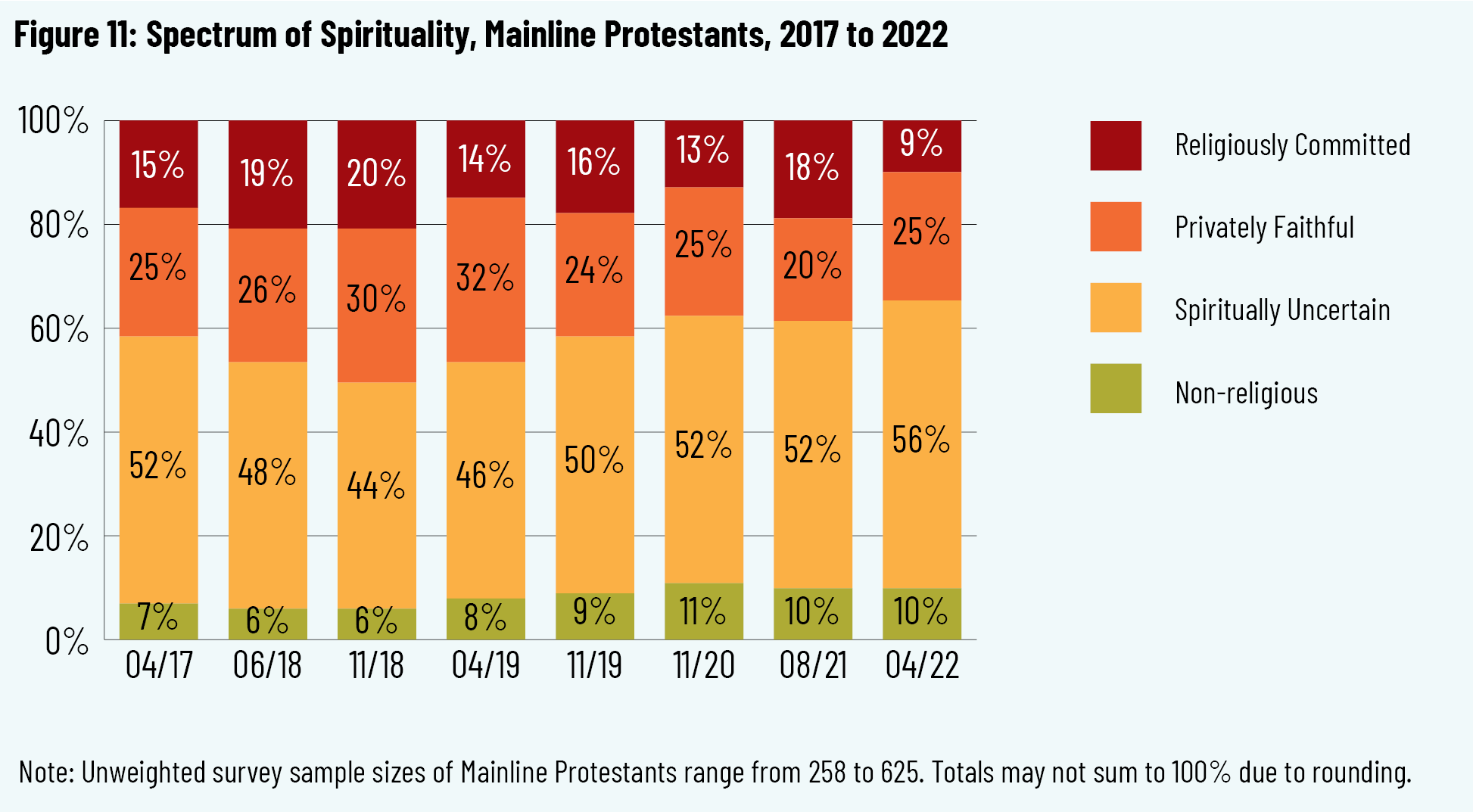

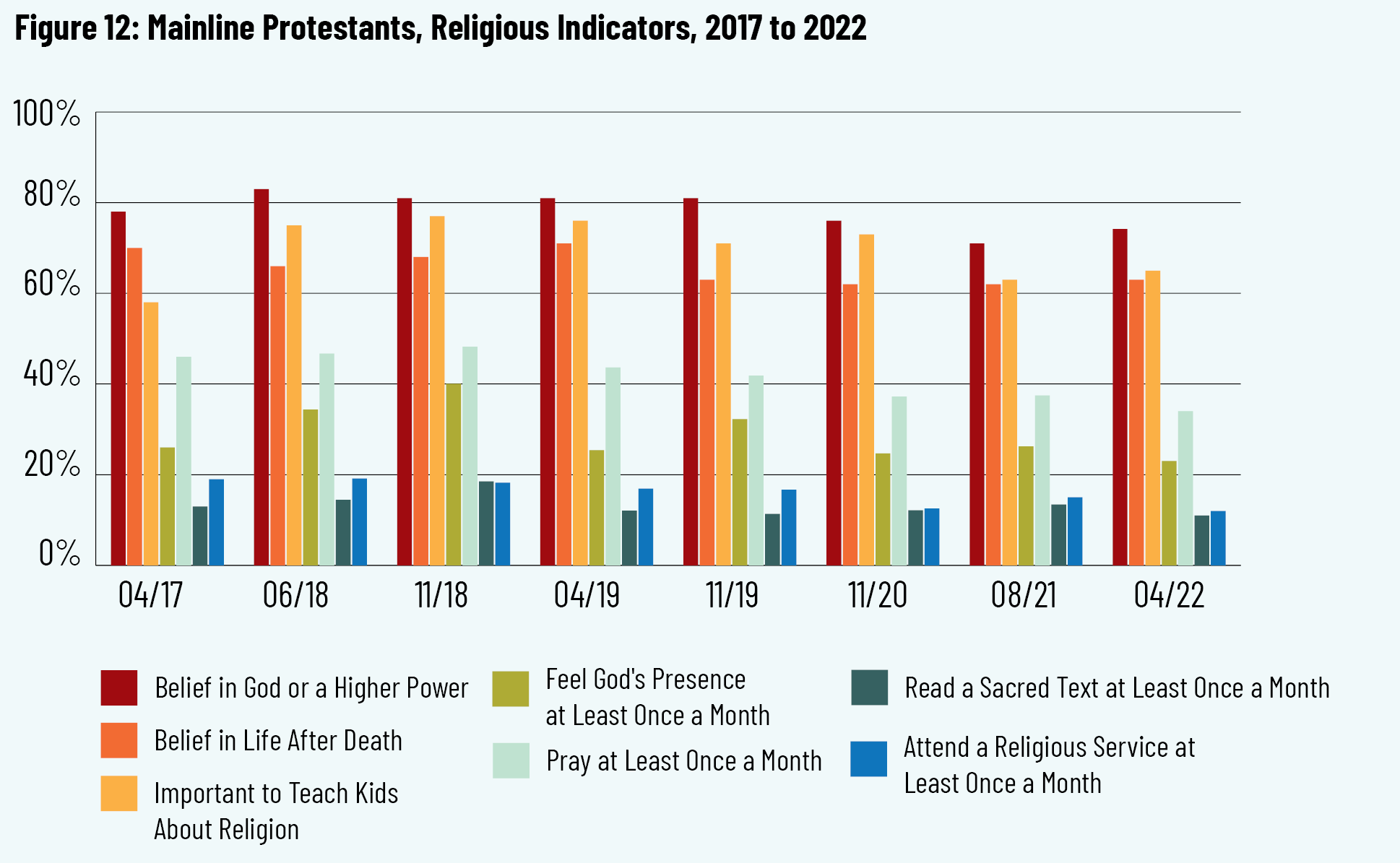

Canadians who indicated their religion as Mainline Protestant tend to score lower on personal and public spiritual indicators since 2017. Bible reading at least once a month and belief in life after death have remained relatively unchanged since 2019, at around 12 percent and 63 percent, respectively.

Nearly a quarter (23 percent) of those who identify as Mainline Protestant feel they experience God’s presence at least once a month, compared to 21 percent of those who reported their religion as Jewish and 29 percent of those who identify as Roman Catholic.

The number of those identifying as Mainline Protestant who pray more than a few times a year hit an all-time low in 2022 at 34 percent, compared to around 45 percent from 2017 to 2019. This percentage is equal only to those identifying as Jewish, the two main faith groups that pray the least often in Canada. Women who identify as Mainline Protestant are twice as likely as men to pray at least once a month (44 percent versus 22 percent) in 2022.

Since 2017, consistently about half of those who reported their religion as Mainline Protestant never read their Bible. About 1 percent read it every day and 11 percent read it monthly or more often in 2022.

Canadians identifying as Mainline Protestant also attend religious services about as often as those who identify as Roman Catholic, with around 12 percent attending at least once a month. This percentage tends to be higher among Mainline Protestants who have a university degree or more education, at around 21 percent who attend services once a month or more.

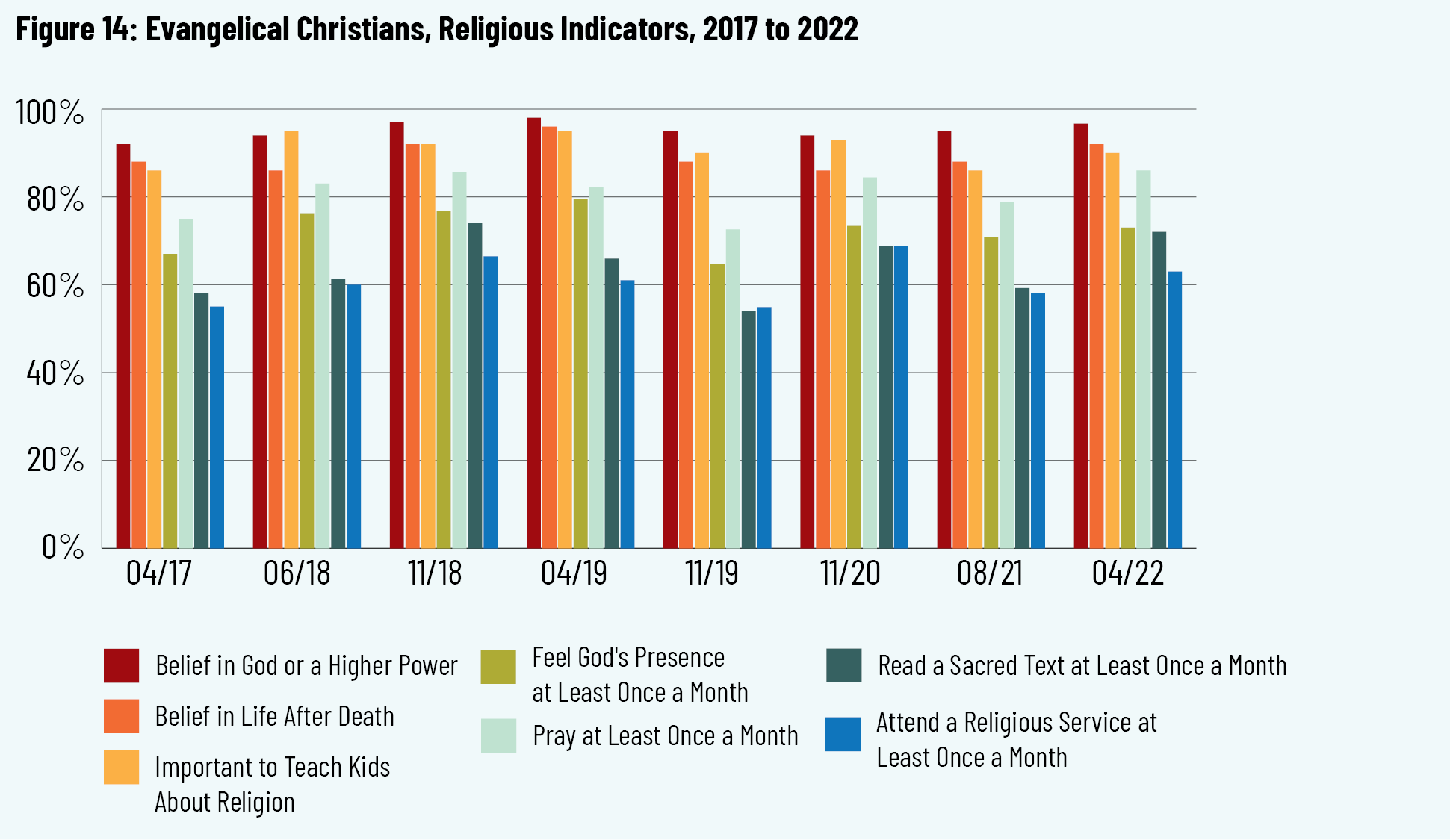

Evangelical Christians

Among the faith groups surveyed in 2022, those who identify as Evangelical Christian had the highest percentage of any major faith group who believe in God or a higher power, at 96 percent. Moreover, 90 percent agree about the importance of parents teaching their children religious beliefs. Since 2017, these numbers have remained relatively stable in the high eighties and mid-nineties.

While Canadians who identify as Evangelical Christian have typically scored high on all index indicators, some religiosity indicators have increased among the group since the April 2019 survey. Moreover, Evangelical Christians are the only faith group surveyed since 2017 that has increased in certain religious indicators and express a higher committed to the faith. Eighty-six percent of those who reported their religion as Evangelical Christian pray at least once a month, an increase from 75 percent in 2017 and 82 percent in April 2019.

Of the main faith groups, those who identify as Evangelical Christian tend to read sacred texts more often. Notably, since 2019, a higher percentage of self-identified Evangelicals read their Bible more frequently. About four in ten (39 percent) read a sacred text every day, an increase of 6 percent from April 2019 and an increase of about 14 percent from 2017.

After experiencing a slight decline in religious-service attendance during the pandemic, a higher percentage of those who identify as Evangelical are attending religious services than they were in 2019. In April 2019, 13 percent of self-identifying Evangelicals indicated they never attend a religious service, compared to 5 percent of Evangelicals in 2022. Nearly half (46 percent) attended religious services once a week in 2022, compared to 37 percent in April 2019.

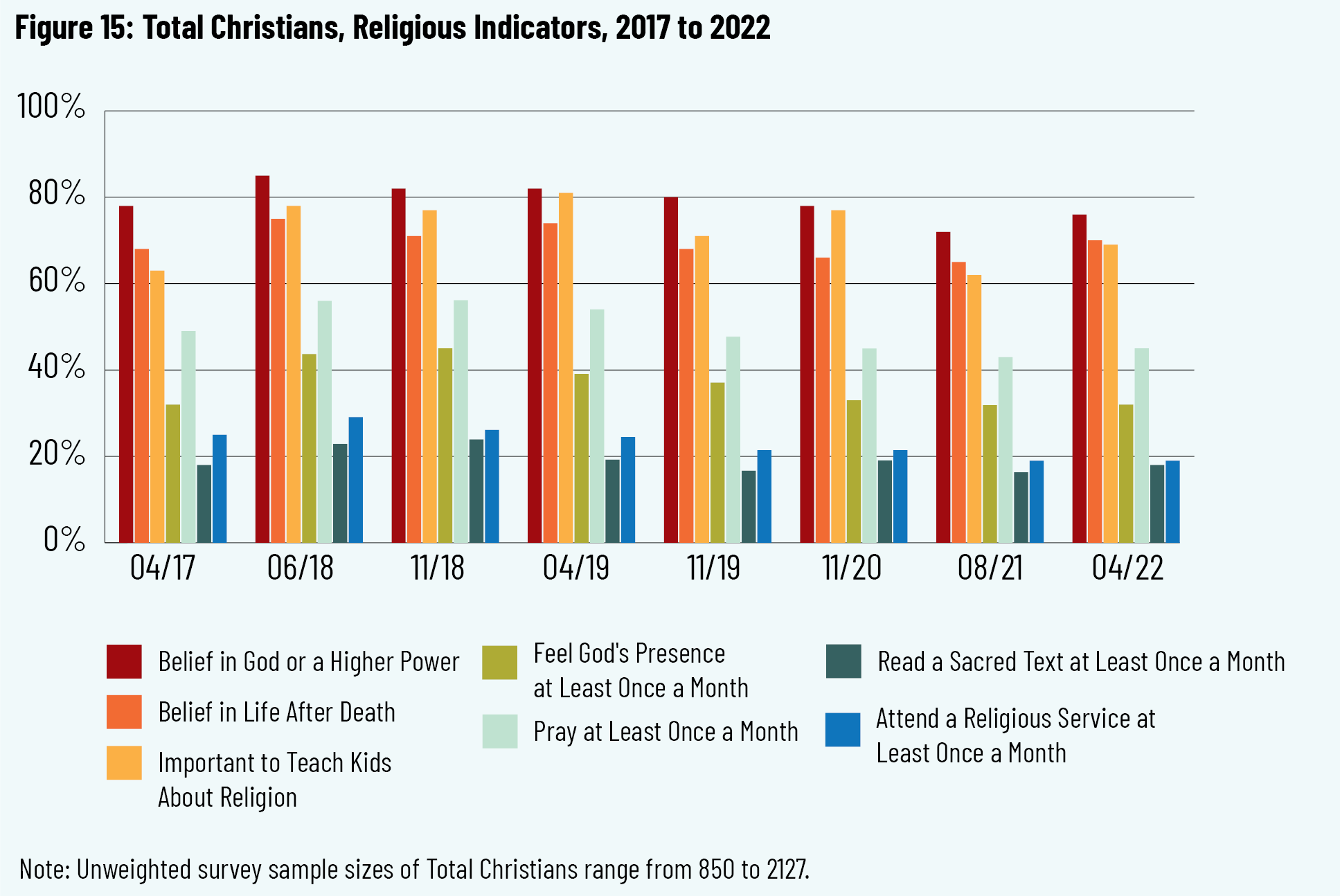

Total Christians

Overall, Canadians who identify as Christian have tended to be less committed to their faith in public and individual religious activities since 2017. That said, the movement in this group is among immigrants and younger Canadians.

Residents of Quebec who self-identify as Christian are less likely to believe in God—about six in ten (58 percent) do, compared with 84 percent of those in Ontario who reported their religion as Christian and 82 percent of Alberta and BC residents who identify as Christian. This suggests that for Quebeckers to say they are Christian is an indication of their cultural heritage rather than their personal beliefs (at least four in ten of the cases). Those who identify as Christian and make less than $50,000 are more likely than those with higher income levels to believe in God (83 percent versus 73 percent). About 78 percent of those who reported their religion as Christian and were raised in a faith background believe in God, compared to 69 percent of those who were not raised in a faith.

Men aged fifty-five years and older who identify as Christian are significantly less likely to believe in life after death (about 55 percent do), compared to 80 percent of women aged thirty-five to fifty-four who reported their religion as Christian and 72 percent of female Christians aged fifty-five years and older in 2022.

The percentage of Canadians who reported their religion as Christian and pray has not significantly changed since 2019. Sixty-four percent of self-identifying Christians who reside in British Columbia pray at least once a month, while a quarter (27 percent) of Quebec residents who identify as Christians never pray. About half (53 percent) of women in this group pray at least once a month, compared with 36 percent of their male counterparts. Sixty-seven percent of immigrants who identified as Christian pray at least once a month, which is lower than those who are Canadian-born Christians in which 41 percent pray once a month or more often.

In 2022, about 18 percent of self-identifying Christians read their Bible once a month or more, with half (50 percent) never reading their Bible or a sacred text. These number have not changed significantly since 2017. About a quarter (24 percent) of those who reported their religion as Christian and are under forty years old read their Bible at least once a month, compared to 16 percent of those over forty years of age. Over one in two (54 percent) of Canadian-born Christians never read their Bible, compared to three of every ten (29 percent) immigrants who self-identify as Christian. British Columbia residents who identified as Christian have the highest percentage of regular Bible readers in all provinces (36 percent). A possible explanation for this data point is that since it may be less socially acceptable to identify as religious in the province of British Columbia, those who identify as religious tend to be those who are not “nominal” Christians.

The total number of those who identify as Christian and attend a religious service once a month or more has declined from one in four (25 percent) in 2017, three in ten (29 percent) in June 2018, to one in five (19 percent) in 2022. About four in ten (39 percent) of Canadians who reported their religion as Christian and reside in British Columbia attend services at least once a month, the highest percentage in all provinces. Similar to overall trends across the country, younger Canadians aged thirty-five years or younger who identify as Christian are twice as likely to attend religious services more regularly than any other age group. Three in ten (30 percent) of this younger group regularly attend religious services as well as immigrants who identify as Christian (31 percent), compared to 16 percent of older Christians and 18 percent of Christians born in Canada. About four in ten (39 percent) of those who identify as Christians and were not raised in a religious tradition never attend a religious service, compared to one in four (25 percent) of Christians who were.

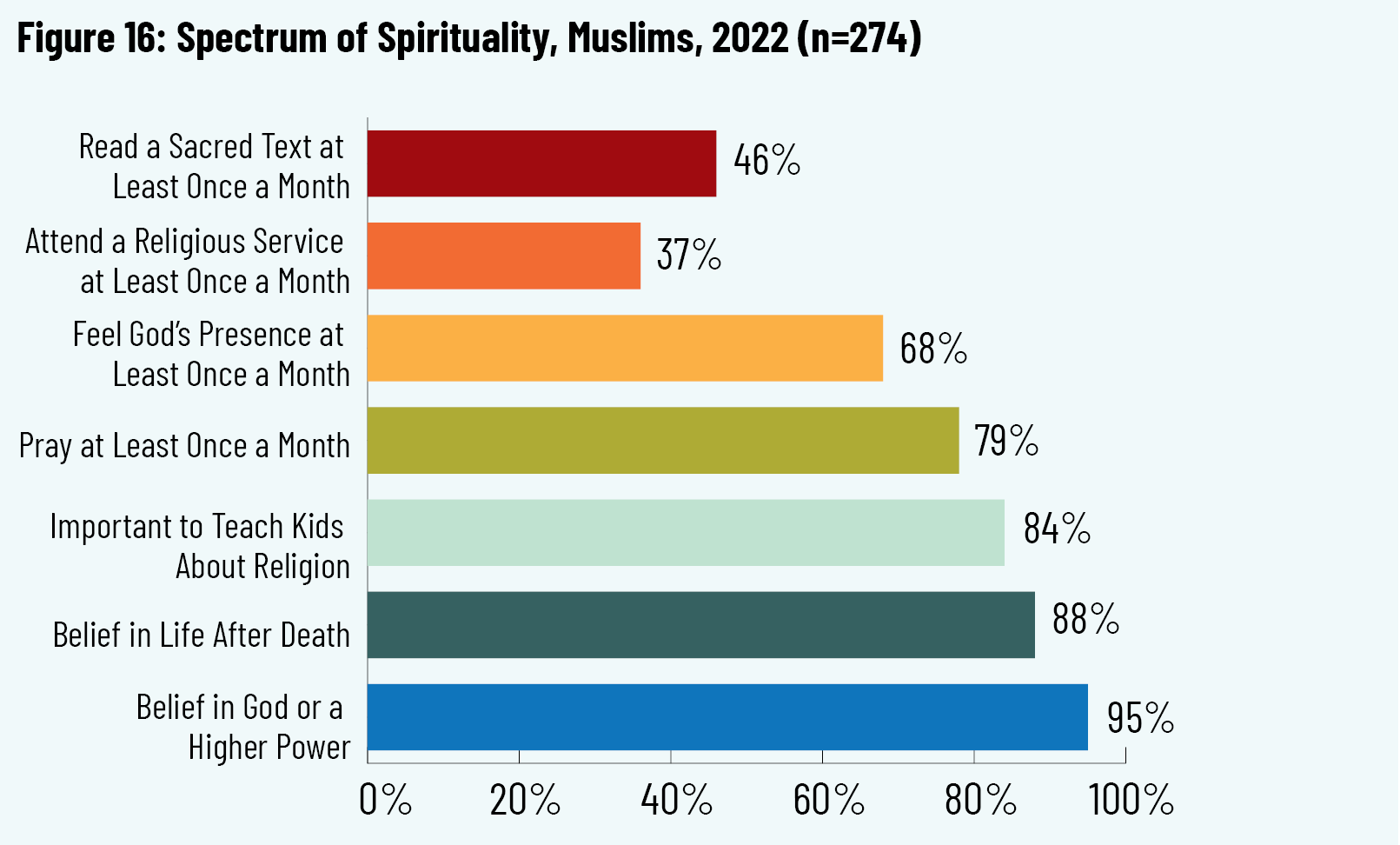

Muslims

While sample sizes are not large enough to track how the spirituality of those who identify as Muslim has changed over time, an oversampling in 2022 has helped shape a broad profile of Muslims in Canada today. Of the main faith groups surveyed, Canadians who identified as Muslim are the second most likely faith group to score highly on the questions that ask about their religious practices. The majority (95 percent) of self-identifying Muslims express a belief in God or a higher power, while 88 percent conveyed a belief in life after death. It can be assumed that when a Canadian identifies as Muslim they hold to the basic Muslim beliefs. However, the same cannot be said of those who identify as Roman Catholic or Protestant: without further information, it should not be assumed that they hold their religion’s basic beliefs.

When asked about how frequently they pray, Canadians who identify as Muslim are the next most likely after those who identify as Evangelical Christian to pray (79 percent pray once a month or more), read the Qur’an or a sacred text at least once a month (46 percent do), and attend religious services at least once a month (37 percent do). About 17 percent of self-identifying Muslims read the Qur’an or another sacred text every day.

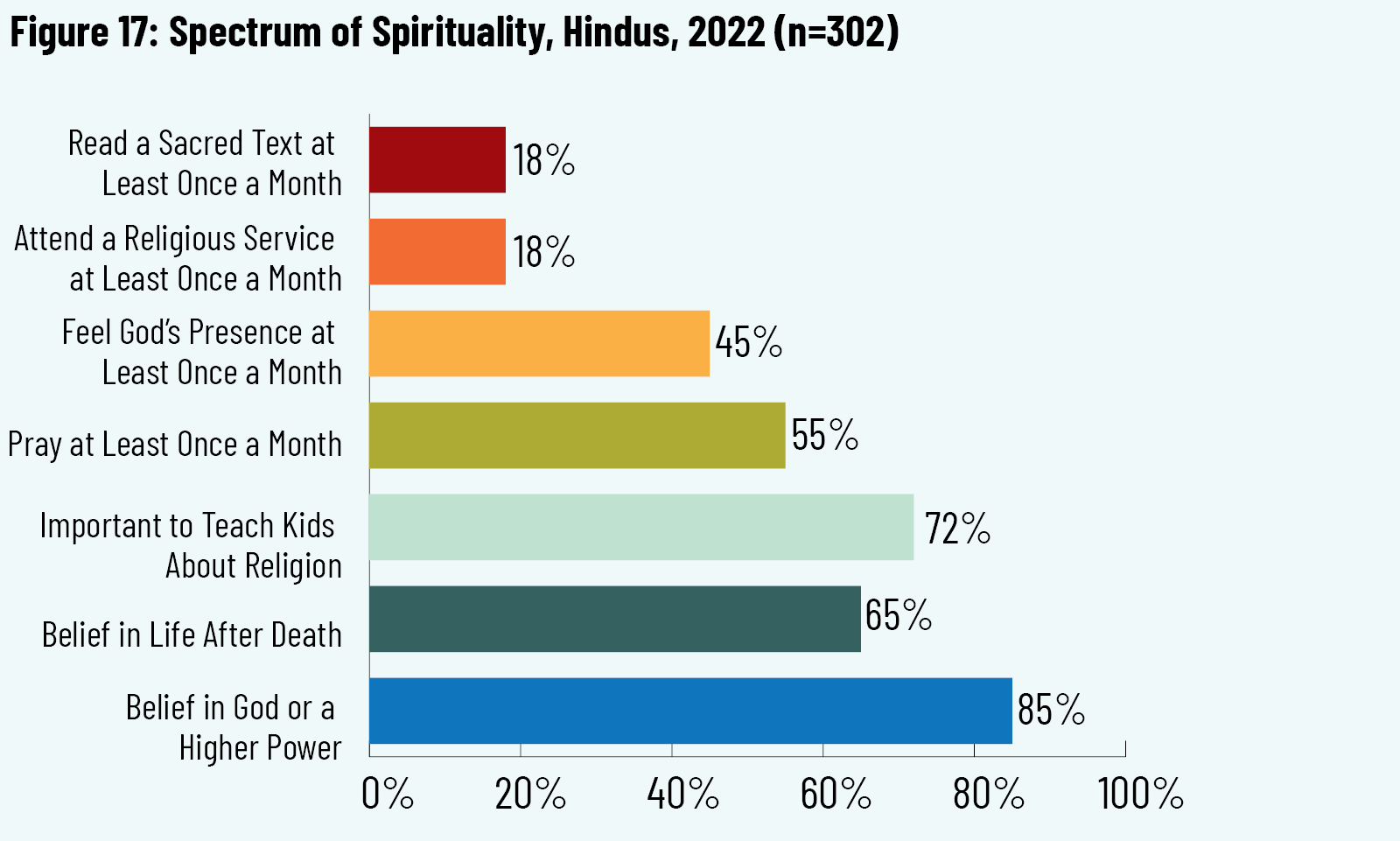

Hindus

Eighty-five percent of Canadians who identify as Hindu expressed belief in God or a higher power, compared with nearly the same percentage of those who identify as Sikh, at 84 percent. About 63 percent of those who reported Hinduism as their religion pray once a month or more, equal to those who self-identify as Sikh. Nearly four in ten (37 percent) never read a sacred text, the same percentage of those who described their religion as Jewish.

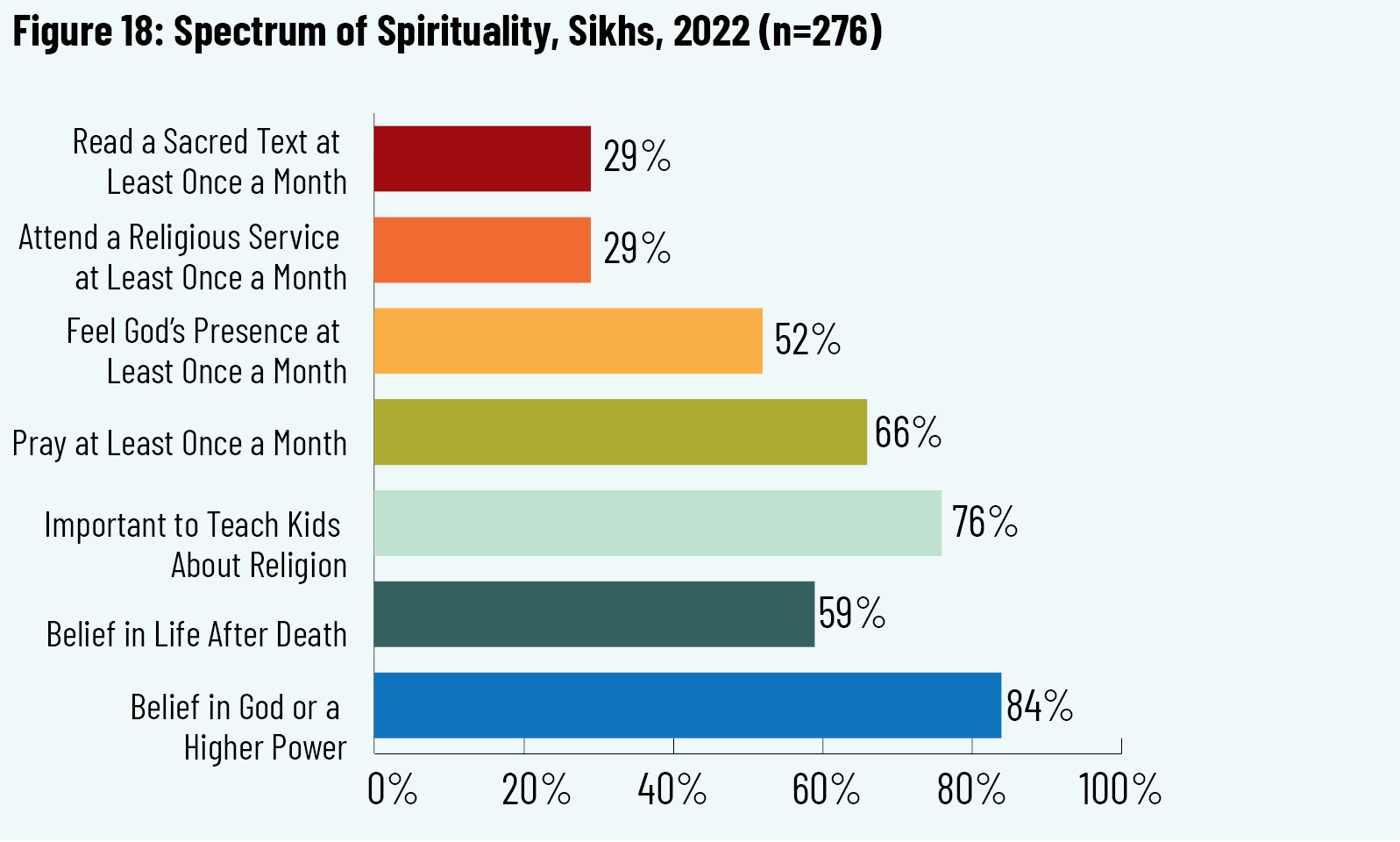

Sikhs

Of the major faith groups surveyed, Canadians who identify as Sikh score relatively high on religiosity indicators: nearly three in ten (29 percent) of Sikhs read a sacred text once a month or more, with about 10 percent reading the text every day and 28 percent attending religious services at least once a month.

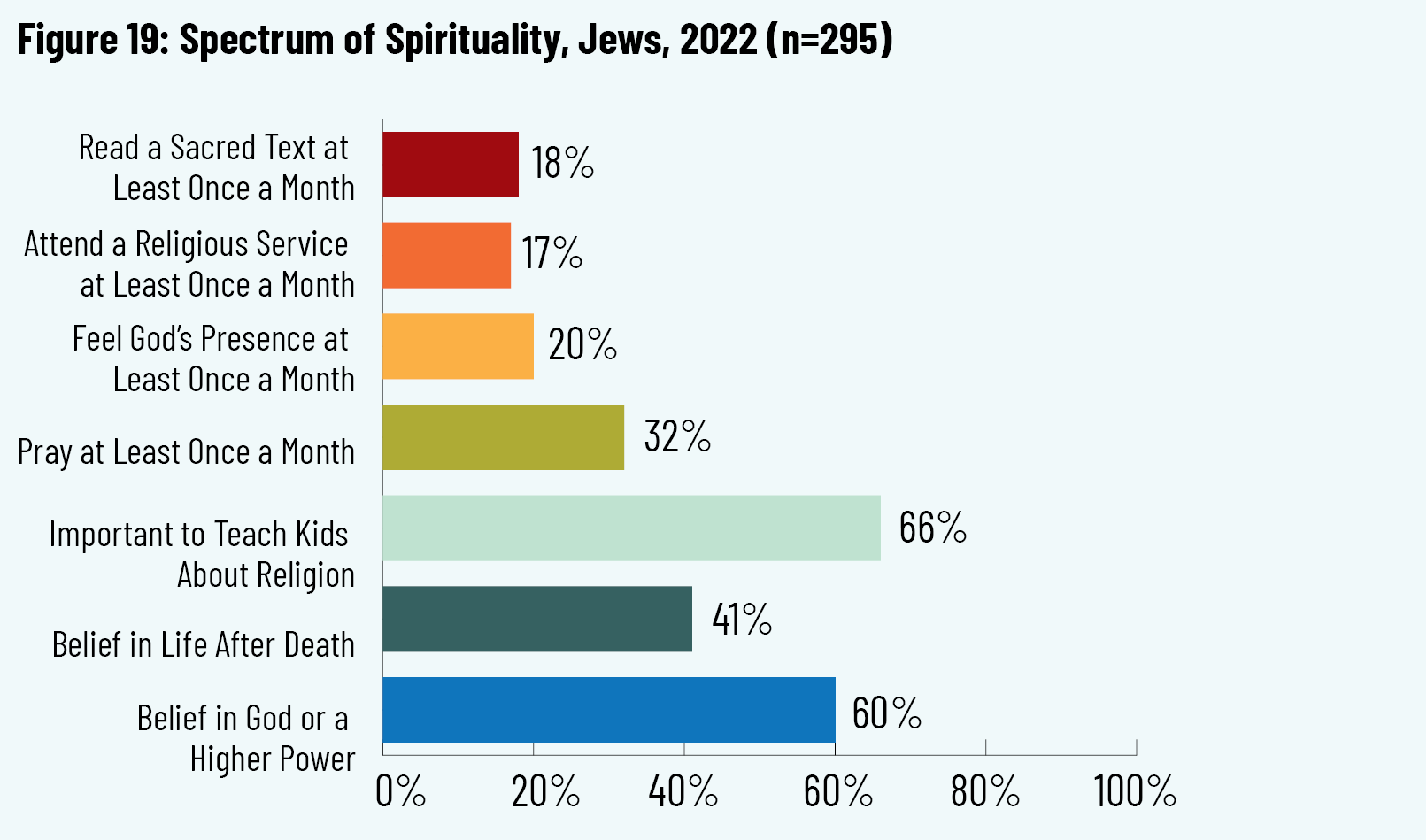

Jews

Those who identified their religion as Judaism in the 2022 survey had the lowest belief in God or a higher power and belief in life after death than any other main faith group, at 60 percent and 41 percent respectively. They are more likely than any other faith group to feel they never experience God’s presence: 42 percent indicated this feeling has never occurred, compared to 43 percent of the total population in 2022. Canadians who find themselves in this faith group are less likely to pray than other faith groups, with the exception of Mainline Protestants: half (51 percent) of self-identifying Jews never or rarely pray, compared to 53 percent of Canadians who identify as Mainline Protestant.

Journey of Faith in Canada

Survey data from 2021 and 2022 have been combined to answer questions relating to who is leaving, joining, or staying in their childhood tradition and the reasons for these changes. 11 11 Given various sample sizes, some subgroups are too small to be able to make meaningful conclusions about them, and therefore we have only reported data points where the sample sizes are reliable, even though that means different reporting for different groups. For example, a deeper dive into the sociodemographic characteristics of each of those who lapsed, stayed, and found faith and their reasons for leaving the faith were not explored for all major religious traditions. Moreover, due to the nature of the survey screener question for the survey conducted in January 2022, an accurate sociodemographic profile of those who stayed, lapsed, and found faith within the Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, and Jewish faith traditions was not examined. Further research is needed to understand the nature of “non-Christian” faith traditions and how these groups are evolving in Canada. For those who were raised in a religious tradition, a particular focus is given to their formal entry process and the frequency of attendance of religious events, ceremonies, and religious instruction as a family to see if there is any difference among those who stayed in their tradition and those who left. Typically, a higher percentage of those who are raised in a religious tradition and stay in their faith go through a formal entry process and attend religious ceremonies more frequently with their families. This pattern is shown across all the faith groups where data was available.

This section also focuses on Canadians who joined a tradition from no religion (found faith) and those who left their childhood tradition for no religion (lapsed). For those who found faith, the main reason for joining a faith typically was a belief in that faith across most of the faith groups.

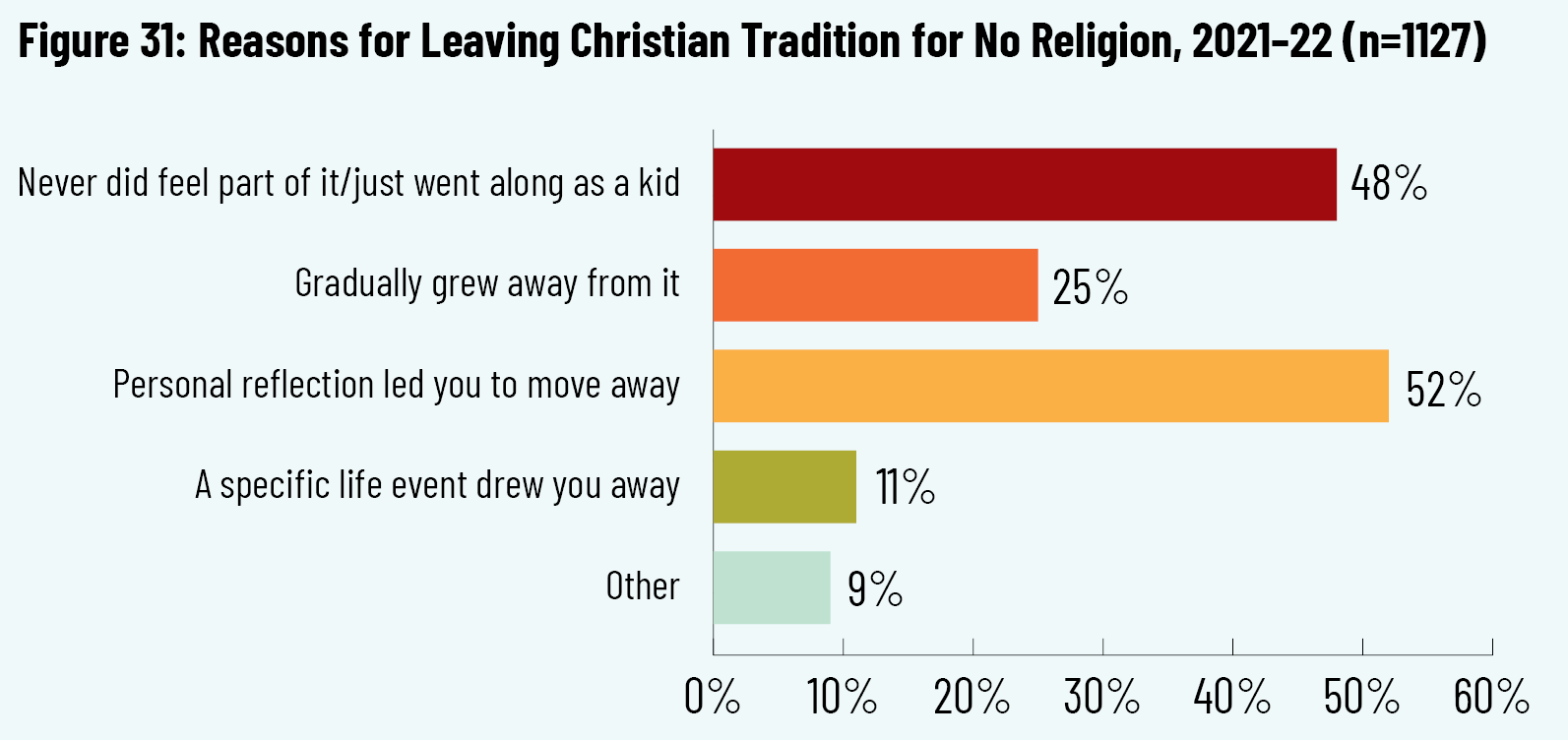

The majority of Canadians who were raised in a particular faith tradition report that they have stayed in that tradition. Those who joined a faith are more likely to have joined from a non-religious background than from another faith. The vast majority (over 90 percent) of these lapsed Canadians indicate no intention of returning and typically do not miss anything about the faith of their childhood. Available data suggest that the main reasons for leaving a childhood tradition in Canada are that personal reflection led them to move away and that they never felt a part of it as a child.

Faith Journey of Roman Catholics

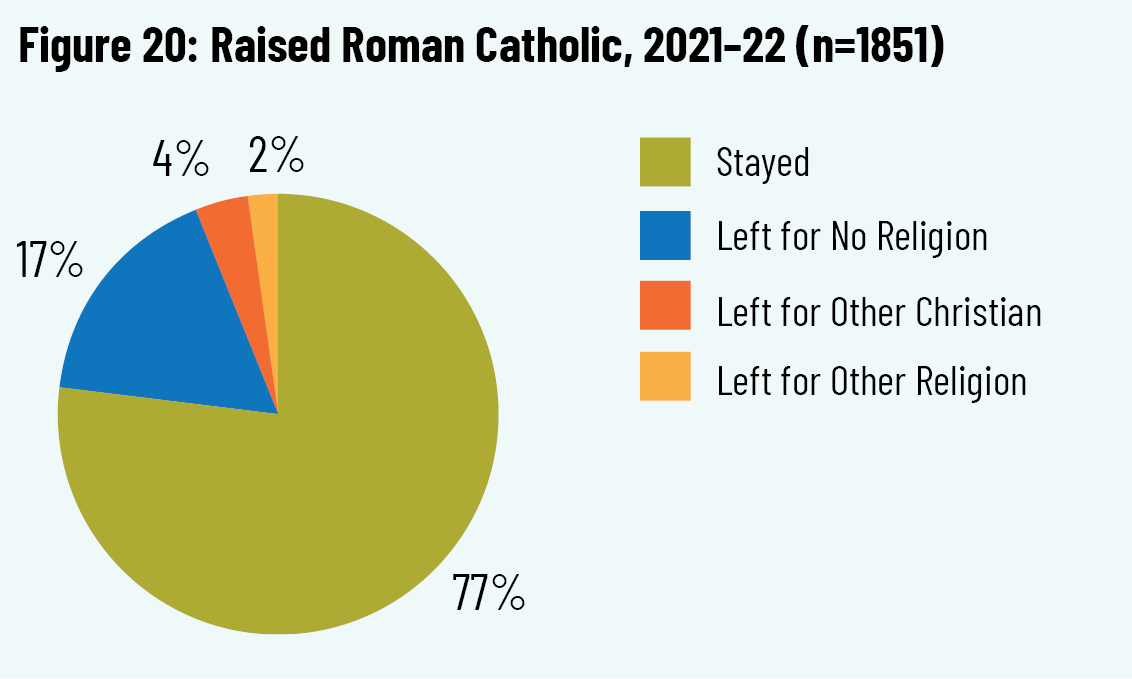

Raised in Roman Catholic Tradition

Of those who were raised in the Roman Catholic tradition, 77 percent identify as Roman Catholic in 2022, 17 percent no longer have a religious identity, 4 percent identify as either Evangelical Christian, Mainline Protestant, or another Christian denomination, and 2 percent left for a non-Christian faith.

It appears that frequent instruction in religion during one’s early years has no correlation with whether they leave or remain in the Roman Catholic faith. The data also suggest that going through a formal entry process and more frequently participating in religious ceremonial holidays as a family were particularly prevalent in those who stayed in the faith compared to those who left.

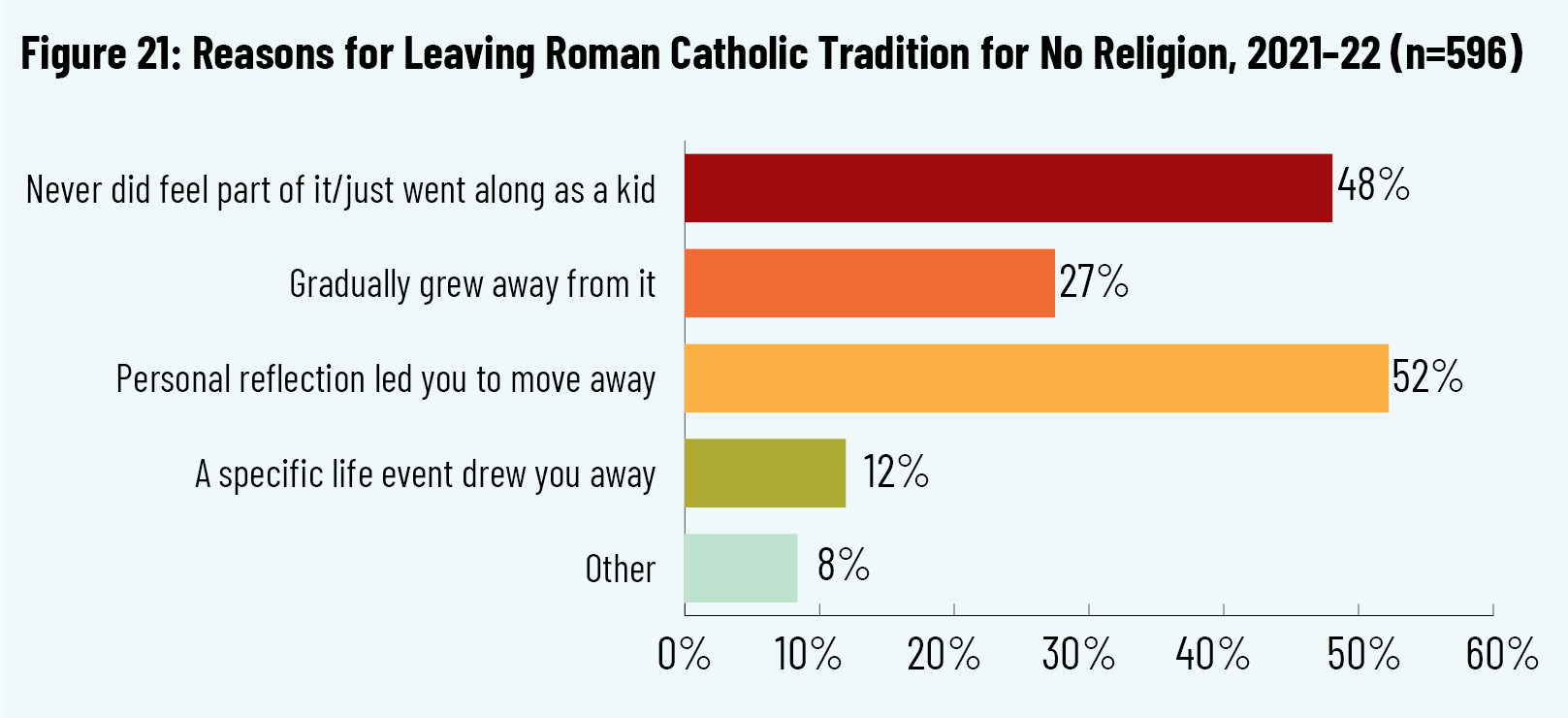

Of those who lapsed, the top two reasons for leaving the Roman Catholic tradition were that personal reflection led them to move away (52 percent) and never feeling a part of it and just going along with it as a kid (48 percent). Seven in ten (72 percent) indicated they did not miss anything about the Roman Catholic tradition, and 95 percent expressed that they never planned to return to their childhood faith. About half (47 percent) noted that their family did not care one way or another that they had left the faith, while three in ten (29 percent) suggested their family was fine with their choice.

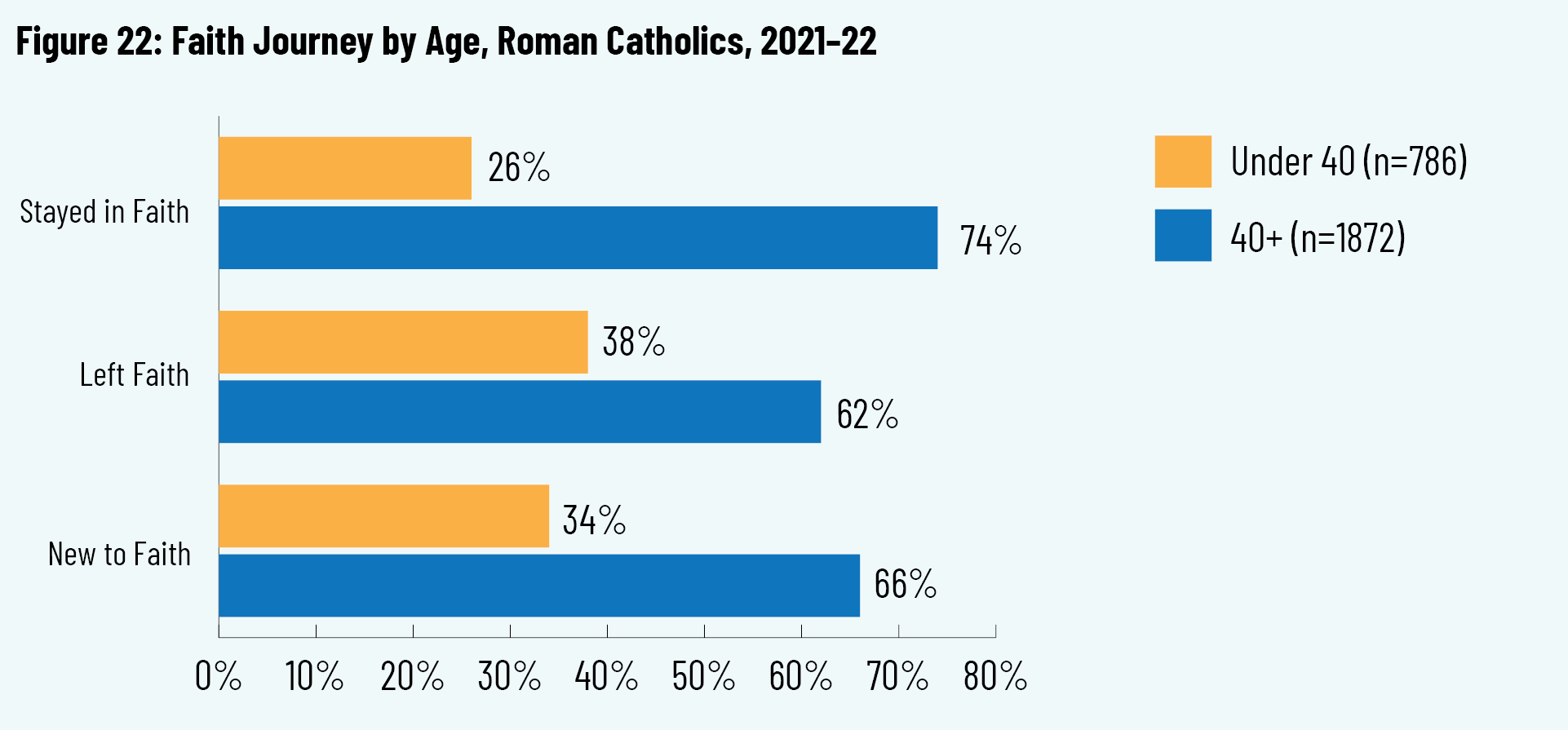

About one in four (26 percent) of those who stayed in the Roman Catholic faith are under forty years of age, compared with 38 percent of those who left the faith.

Journey to Roman Catholicism

Of those who identify as Roman Catholic, 77 percent grew up in the tradition, while about 21 percent joined from no religion and 2 percent joined from a different Christian denomination.

About one in four (27 percent) of those who converted to a religion (found faith) joined because of belief in the faith, while 21 percent joined for marriage, and another 35 percent for other reasons. In this group, 42 percent appreciate the traditions most about their faith, while one-quarter (27 percent) indicated they value belonging to something larger or that it provides a framework for understanding the world.

Of those who were new to Catholicism from no religious tradition, 38 percent said their family is fine with their choice of joining the Roman Catholic tradition, compared to 39 percent who said they do not care one way or another.

Faith Journey of Mainline Protestants

Raised in Mainline Protestant Tradition

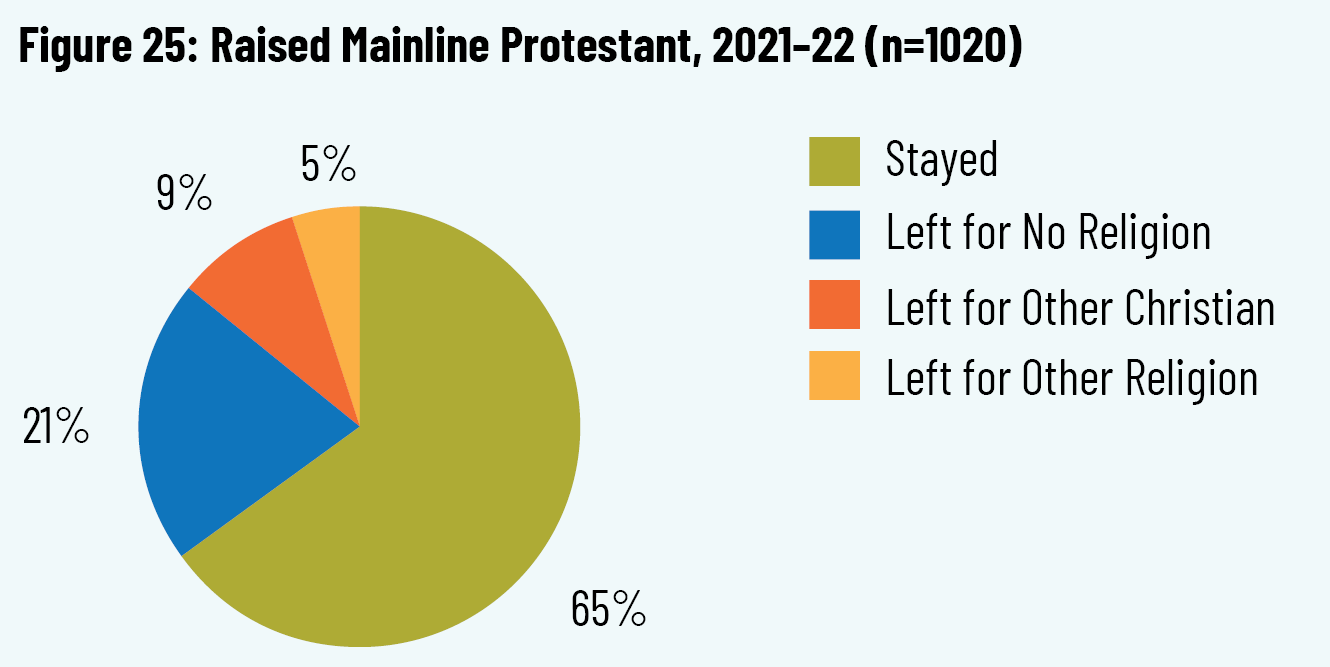

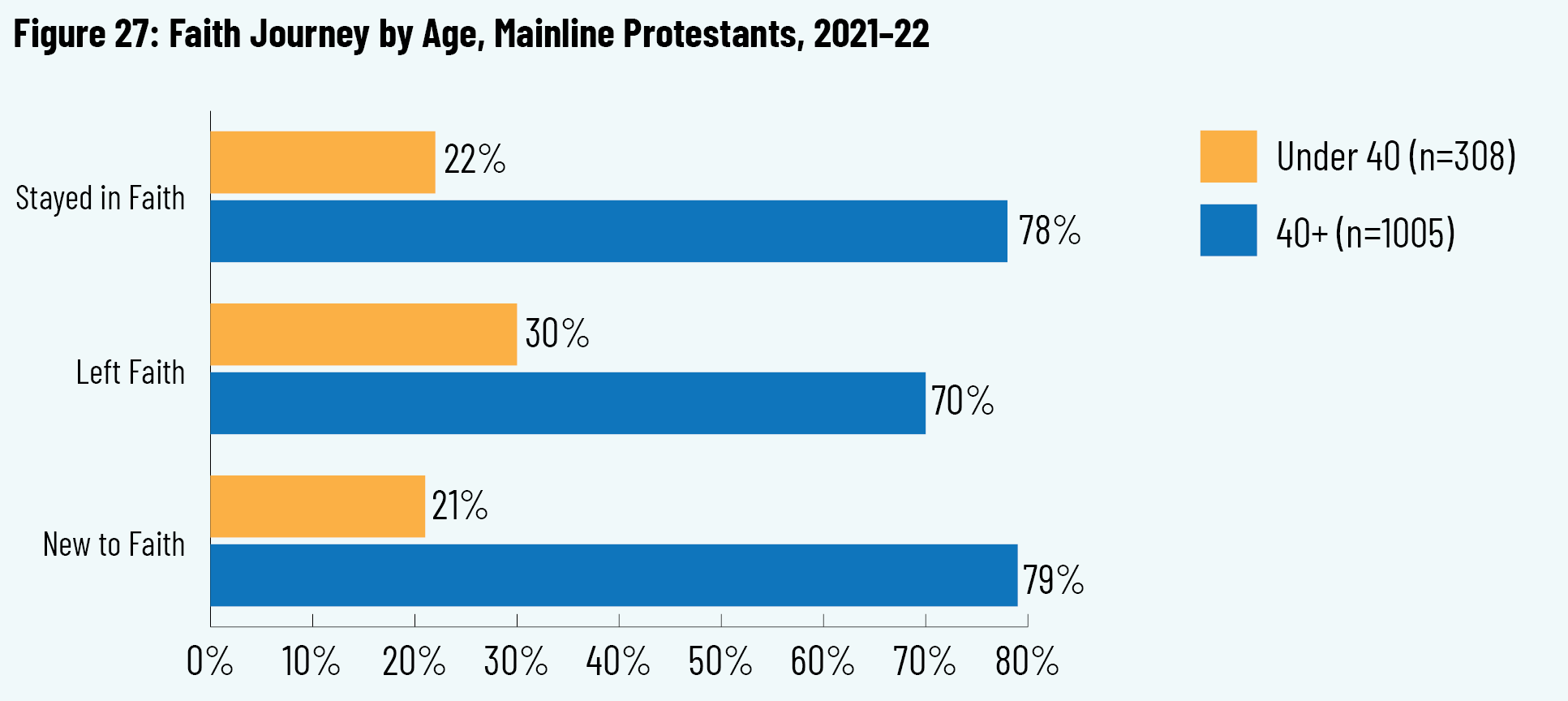

Of those who were raised Mainline Protestant, 65 percent stayed in the faith, 21 percent left for no religion, 9 percent left for another Christian faith, and 5 percent converted to a different religion.

About 69 percent of those raised Mainline Protestant had monthly or more religious instruction, with little to no difference between those who left the faith and those who stayed in the faith. Similar to those who stayed in the Roman Catholic tradition, about 63 percent of those who stayed in the faith fully went through a formal entry process, compared to 47 percent of those who left the Christian faith altogether. While around 67 percent indicate they participated in ceremonies relating to religious holidays a few times a year or less, a higher percentage of those who left the faith participated in these ceremonies less frequently than those who stayed (76 percent of those who lapsed did a few times a year or less versus 65 percent of those who stayed).

About three in four (74 percent) of those raised Mainline Protestant participated in religious events as a family a few times a year or less. Nineteen percent who lapsed participated in religious events monthly or more often, compared to 26 percent of those who stayed in the faith.

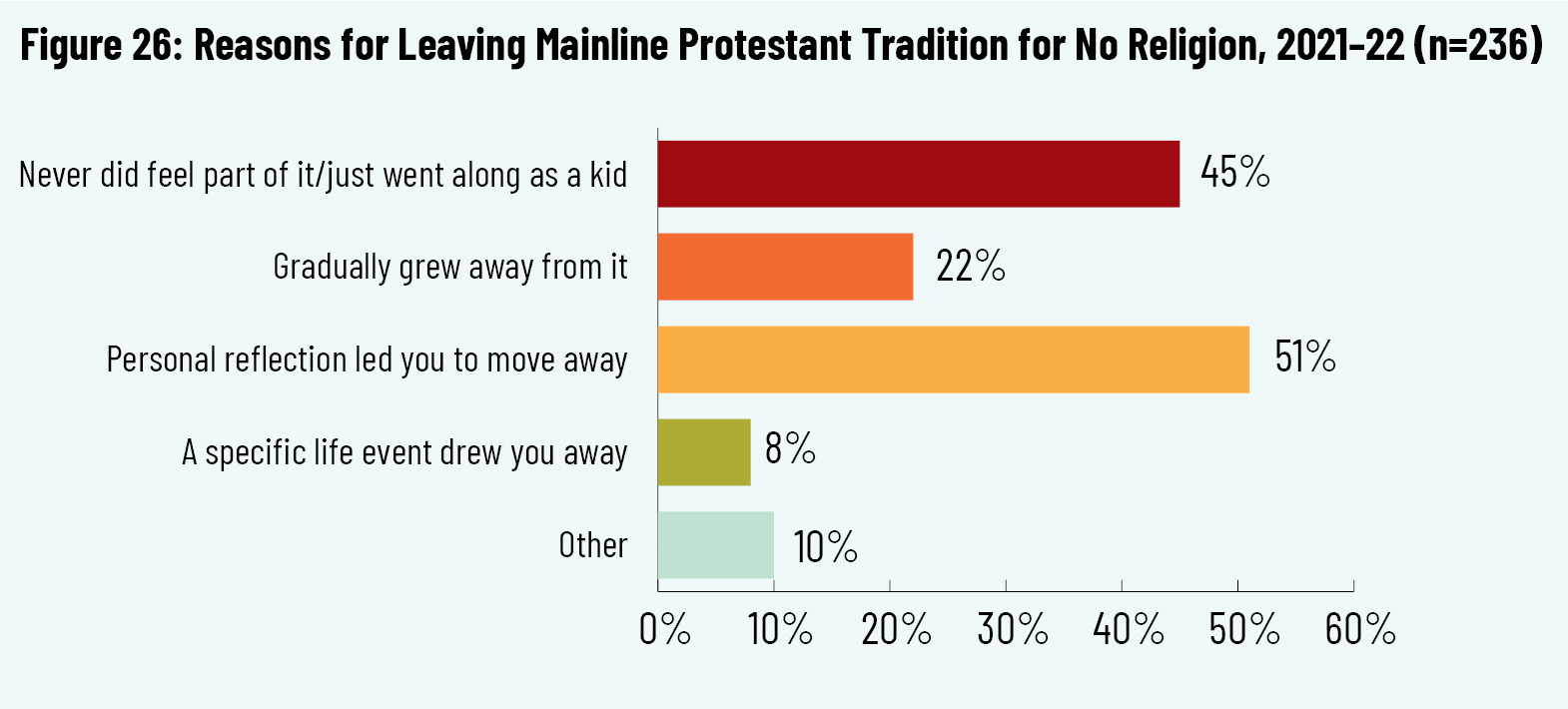

The top reasons for those who left their Mainline Protestant childhood tradition for no religion were similar to the reasons of those who lapsed from the Roman Catholic tradition: 45 percent stated they never felt a part of it, and about half (51 percent) expressed that personal reflection led them to leave the faith.

Nearly three-quarters (74 percent) of lapsed Mainline Protestants indicated they do not miss anything about their faith. Like those who lapsed from Roman Catholicism, 95 percent said that it is unlikely they will return to their childhood faith tradition and 93 percent did not think they would return to any faith in general. Half (50 percent) of those who lapsed said their family does not care that they left, while 32 percent say they are fine with their choice.

Of those who stayed in their childhood faith, 55 percent are female and 78 percent are forty years and older. Conversely, those who left the faith tend to be male (55 percent are). A higher percentage of those who left the faith are under forty years of age, compared to those who stayed (30 percent versus 22 percent).

Journey to Mainline Protestantism

About six in ten (62 percent) of those who identified as Mainline Protestants today were raised in the faith, while 33 percent joined from no religion and about 5 percent from a different Christian tradition.

The top three reasons for joining the Mainline Protestant faith from no faith background were belief in the faith (25 percent), marriage/relationship (22 percent), and other reasons not listed (33 percent). Four in ten (41 percent) of those who found faith expressed that traditions were the most important thing about their newfound faith, while one-quarter (25 percent) indicated other things were important, and 23 percent appreciated belonging to something larger.

Faith Journey of Evangelical Christians

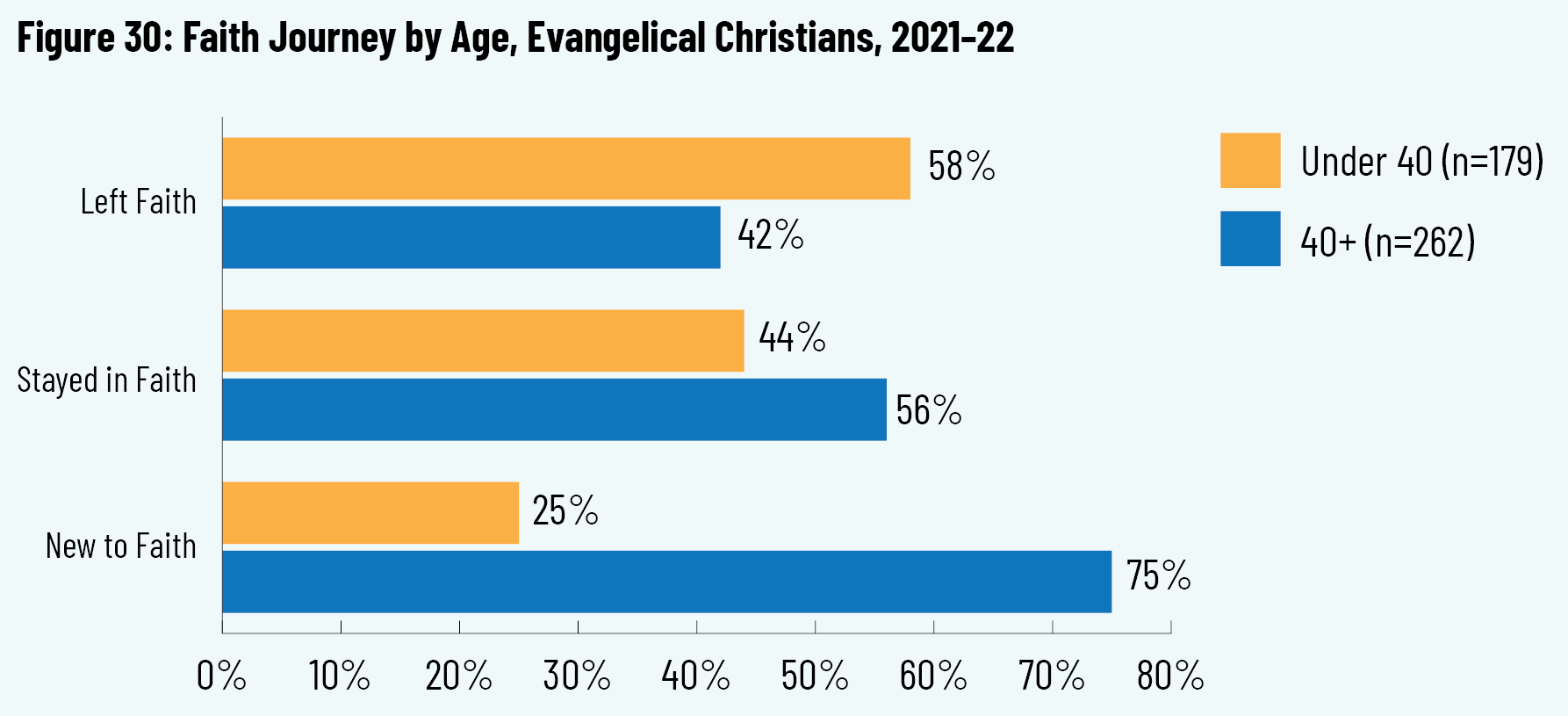

Of those who were raised in an Evangelical Christian tradition, six in ten (63 percent) stayed in the faith, while about 17 percent left for no religion, and 17 percent left for another Christian tradition.

About 76 percent of those raised in the Evangelical Christian tradition received monthly or more frequent religious instruction and about 63 percent participated in religious events as a family at least once a month. Nearly half (49 percent) fully went through a formal entry process, while 18 percent did not.

Journey to Evangelical Christianity

One in four (25 percent) of self-identifying Evangelical Christians today converted from no religious tradition, compared to 18 percent of those who joined from a different Christian denomination. Three in four (75 percent) who joined the faith are over forty years old, while 58 percent of those who left are under the age of forty.

Faith Journey of Christians

Of those who were raised in a Christian tradition, slightly more than seven in ten (71 percent) stayed in the faith, while about 7 percent changed denominations, about a one in five (19 percent) left for no religion, and 3 percent changed faiths entirely.

About half (47 percent) of those who stayed in their denomination participated in ceremonies relating to religious holidays, compared to 35 percent who left the faith for no religion. Seventy-nine percent of those who stayed in their denomination fully went through a formal entry process, compared with 59 percent of those who left.

The top two reasons for leaving the Christian faith for no religion are (1) personal reflection led them to move away (52 percent) and (2) never feeling a part of it (48 percent). Over three in five (66 percent) who left the Christian faith for another faith tradition indicated they did not miss anything about the faith, compared to 77 percent of those who left for no religion. Of those who converted to a non-Christian faith, one in three (33 percent) indicated they appreciate belonging to something larger as the most important thing about their new faith, while 41 percent said there are other things not listed they appreciated, and 21 percent said they appreciate the traditions. Four in ten (40 percent) of those who left the faith said their family is fine with their choice, while 36 percent noted that their family does not care one way or another.

Journey to Christianity

Of those who identify as Christian today, 67 percent stayed in their denomination, 7 percent shifted from a different denomination to their current one, 25 percent found faith from no religious background, and about 1 percent converted from a different religion. It appears that in contemporary Canada, which we tend to think of as a predominantly secular society, there are many Canadians who have moved from a position of no religion to a position of Christian adherent.

Three in ten (29 percent) of those who chose to adopt the Christian faith from no religion came because of belief in faith, while 33 percent came for other reasons and 21 percent came because of marriage or a relationship. The top things they appreciate about their new faith are the traditions (39 percent) and belonging to something larger (29 percent).

Nearly 70 percent of those who came to faith from no religion are over forty years of age, while 45 percent of those who left for no religion are under the age of forty years old. Seven in ten of those who stayed in the faith are over the age of forty.

Faith Journey of Non-Christians

It is recognized that the data gathered on non-Christian faith groups are too incomplete to paint a rich profile of these faiths, but the hope is that future research can fill in these gaps. Where sample sizes were large enough, conclusions are noted in this section. Due to the small number of participants who indicated they found the Muslim faith in our 2022 survey, no conclusions could be made regarding the reasons for joining the faith and things appreciated about that faith.

Raised in Non-Christian Faith Tradition

Slightly more than half (58 percent) of those who were raised Muslim participated in religious instruction at least once a week and 42 percent attended religious events as a family weekly in their childhood.

About 33 percent of those who were raised in a Hindu faith tradition never attended religious instruction in the religion’s teaching, while 29 percent attended instruction at least once a month. Conversely, 36 percent of those raised in the Sikh tradition attended religious instruction at least monthly, and 41 percent participated in monthly or more religious ceremonies as a family. Fifty-eight percent of those raised in the Hindu faith participated in religious ceremonies relating to religious holidays a few times a year, and about half (48 percent) in religious events such as group prayer with their families. Of those who were raised in a Jewish faith tradition, 69 percent attended religious instruction weekly. About 42 percent participated in religious ceremonies as a family weekly.

Journey to Faith

Belief in faith among converts to non-Christian religions appears to be the main reason for joining from no religion. Of those who converted to Hinduism from no religion, the top reason for joining was a belief in that faith (32 percent). Forty-eight percent of those who found Sikhism came for the same reason. The top reasons for those who converted to Judaism from no faith were also a belief in that faith (30 percent), other reasons (49 percent), and a long-standing interest in religion (18 percent).

Most Canadians who found faith in these religions appreciated the traditions of their newfound faith. Those who converted to Hinduism indicated they appreciate the traditions, belonging to something larger, and the community the most about their faith, while those who converted to Judaism from no religion appreciate the traditions, community, and other things not listed in the survey. Those who found Sikhism indicated that they appreciate the traditions and belonging to something larger.

The family response of those who converted to these faiths from a non-religious background suggests that most families are fine with their choice of conversion. About half (51 percent) indicated their family is fine with their choice of joining Hinduism, along with 46 percent of Jews and 55 percent of Sikhs.

Faith in Public Life

While most of this paper has been dedicated to understanding shifts in Canadians’ spirituality and journey of faith over time, it is also important to underscore how Canadians with these religious beliefs relate to and contribute to public life. The faith groups that tend to score higher on the religiously committed end of the Spectrum are also the most public about their faith: Canadians who identify as Evangelical Christian expressed the highest propensity to be public about their faith, followed by those identifying as Muslim and Sikh.

![Figure 23: [Found Faith] Reasons for Joining Roman Catholic Faith from No Religion, 2021–22 (n=280)](https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Figure-23.png)

![Figure 24: [Found Faith] Appreciate about Roman Catholic Faith, 2021–22 (n=280)](https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Figure-24.png)

![Figure 28: [Found Faith] Reasons for Joining Mainline Protestant Faith from No Religion, 2021–22 (n=269)](https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Figure-28.png)

![Figure 29: [Found Faith] Appreciate about Mainline Protestant Faith, 2021–22 (n=268)](https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Figure-29.png)

![Figure 32: [Found Faith] Reasons for Joining Christianity from No Religion, 2021–22 (n=772)](https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Figure-32.png)

![Figure 33: [Found Faith] Appreciate About Christian Faith, 2021–22 (n=772)](https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Figure-33.png)

![Figure 34: [Found Faith] Reasons for Joining Faith from No Religion, 2022](https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Figure-34.png)

![Figure 35: [Found Faith] Appreciate about New Faith, 2022](https://www.cardus.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Figure-35.png)