Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Values of generosity, giving, and participation in community are considered essential by many Canadians. For many, the giving of both time and resources in the form of volunteering and charitable donations is a part of the fabric of a way of life: a mark of healthy citizenship and flourishing society. Many Canadians volunteer in informal ways in their daily lives. Formal volunteering, however, is in decline in Canada. This decline among younger generations of Canadians is having a profound impact on Canada’s charitable sector, a sector that generates more than 7 percent of Canada’s GDP and employs more than two million people every year.

The ease with which one can participate as a volunteer is important for the growth and encouragement of formal volunteering in Canada. Policy options that serve to facilitate this growth are not hard to find. We propose that one such area is evaluation of the purpose, methods, and access to vulnerable sector checks for prospective volunteers and charitable organizations.

Employers and charitable organizations use vulnerable sector checks as part of the volunteer screening process. These checks are required by most organizations or employers for anyone working or fulfilling a role in which they are in a position of trust or accountability for vulnerable persons, such as children, the elderly, or persons with disabilities. In this research report, we present an overview of vulnerable sector checks in Canada and describe the ways in which these checks present challenges and barriers to prospective volunteers and to the charitable sector.

In this paper we also offer a brief perspective on the Ontario government’s announcement on March 30, 2022, that some police checks will be free for volunteers, and we suggest ways in which Ontario can further support prospective volunteers and employees who require vulnerable sector checks. Finally, we suggest areas for future research and investigation to strengthen the process of vulnerable-sector screening and to support the charitable sector.

Volunteering in Canada: An Overview

Values of generosity, giving, and participation in community are considered essential by many Canadians. For many, the giving of both time and resources in the form of volunteering and charitable donations is a part of the fabric of a way of life: a mark of healthy citizenship and flourishing society. Research consistently demonstrates the intangible benefits of volunteering. Volunteers describe increased self-esteem and self-confidence, a greater sense of worth, and a contribution toward something meaningful. 1 1 S. Baines and I. Hardill, “‘At Least I can Do Something’: The Work of Volunteering in a Community Beset by Worklessness,” Social Policy and Society 7, no. 3 (2008): 307–17 (here 314). This social benefit multiplies into the workplace: employees who volunteer find greater meaning in both their workplace and their place of volunteering compared with those who do not volunteer. 2 2 J.B. Rodell, “Finding Meaning Through Volunteering: Why Do Employees Volunteer and What Does It Mean for Their Jobs?,” Academy of Management Journal 56, no. 5 (2013): 1274–94 (here 1287–9). In recent years, the importance of volunteers to the emergency-management sector has been highlighted as Canada has faced numerous natural crises on top of a pandemic. Western provinces have faced deadly wildfires and significant flooding, and as the effects of climate change multiply, the prospect of future natural disasters becomes more likely. The navigation of these emergencies by first responders is critical, and local volunteers often play a critical role. In fact, in these situations, local knowledge becomes critical to the success of crisis management, illustrated especially in the fact that “community volunteerism leverages participants’ intimate knowledge of their respective communities, as well as their ability to provide situational awareness on local situations and demographics.” 3 3 A. Landry, C. Price, and R. Colwell, “The Rising Importance of Volunteering to Address Community Emergencies,” Canadian Journal of Emergency Management 2, no 1 (2022): 56–67 (here 57). The argument that emergency response should institutionalize volunteerism, developing regular volunteer training and disaster response preparedness in anticipation of future emergencies, demonstrates integral and core elements of volunteer work to social architecture. 4 4 Landry, Price, and Colwell, “Rising Importance,” 62.

Research on the involvement of immigrant communities in local charities in their new countries has at times advanced the perspective that volunteer labour is exploitative, serving to increase the performance of non-government organizations and to weaken the state’s responsibility toward the welfare of its newcomers. However, researchers have found that migrants and immigrants who volunteer in Italy view their involvement as a claim to agency and engagement in citizenship activity. Immigrant volunteers suggest that their involvement in the charitable sector enabled them to build social capital, to gain recognition among their peers and within their new country, and to assume the role of benefactor, boosting self-perception and feelings of value as members of society with “something to give.” In a direct response to the increased role and responsibility of the state, these immigrants use volunteering as a form of “lived citizenship” or “citizenship from below,” in which ideas and concepts of citizenship are re-engaged and reorganized. This active involvement in shaping the new society in which they now live is itself an expression of the socially generative function of volunteering and offers a perspective rooted in the agency and whole humanity of newcomers to a host country. 5 5 M. Ambrosini and M. Artero, “Immigrant Volunteering: A Form of Citizenship From Below,” International Society for Third-Sector Research, January 26, 2022, 2, 6, 7, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00454-x.

These examples demonstrate that within highly variable contexts and diverse populations, volunteering has a generative effect on civic society. The importance of volunteering in the contexts of emergency management and the preservation of natural resources, and for newcomers and immigrant communities, are two areas relevant to our collective conceptions of Canada and to its future.

Statistics Canada’s current measurement of volunteering encompasses both formal and informal volunteering. Formal volunteering, or volunteering within a civic context, is voluntary participation mediated by an organization to benefit groups, individuals, or the community at large. Informal volunteering is direct help toward another group or individual without the involvement of an intermediary or charitable organization. 6 6 T. Hahmann, “Volunteering Counts: Formal and Informal Contributions of Canadians in 2018,” Statistics Canada, April 23, 2021, 1, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2021001/article/00002-eng.pdf?st=a1wMYxaz.[/footnote]Statistics Canada has been measuring formal volunteering longer than informal volunteering, and the Canadian definition of informal volunteering is broader than that of the International Labour Organization.[footnote]See Hahmann, “Volunteering Counts,” 11. The International Conference of Labour Statisticians defines volunteer work as “work performed by persons of working age who . . . performed any unpaid, non-compulsory activity to produce goods or provide services to others” and differs from the Canadian definition of volunteer work by stipulating that the goods and/or services provided must be for longer than a period of one hour, and excludes activities mandated by an employer or direct help provided for relatives outside of one’s household. The volunteer rate in Canada according to the international definition of volunteering was 66 percent in 2018. Data from the most recent General Social Survey: Giving, Volunteering, and Participating suggest that 74 percent of Canadians engage in informal volunteering, encompassing such activities as direct help with housework, home maintenance, outdoor work, and personal care. 7 7 Hahmann, “Volunteering Counts,” 1; M. Sinha, “Volunteering in Canada, 2004 to 2013,” Statistics Canada, June 18, 2015, 17 https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2015003-eng.pdf?st=1TPNDJGh.The Canadian definition includes in-home assistance when the volunteer is a relative but not living in the same household.

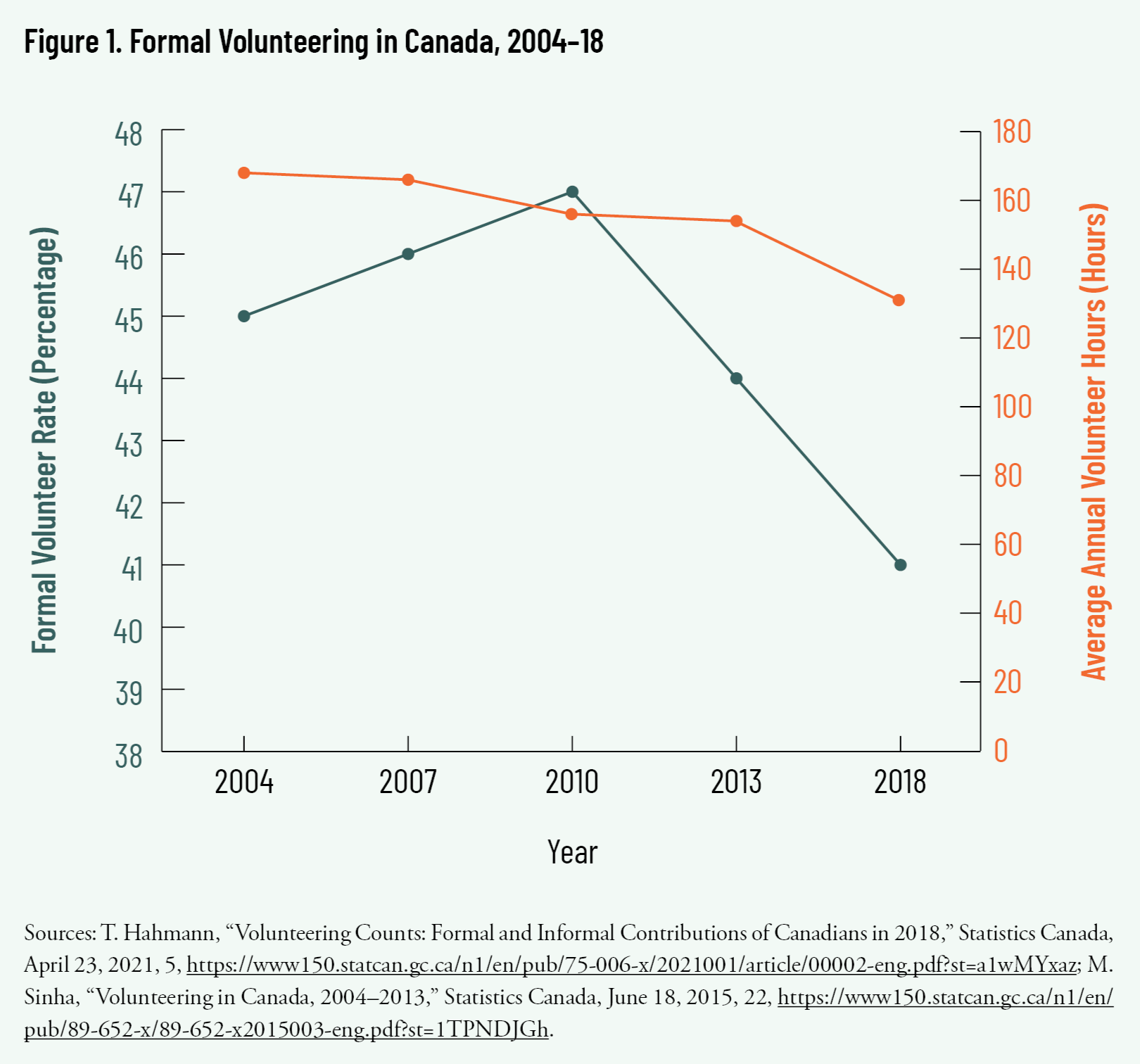

Volunteering in a civic context, or formal volunteering, is in decline in Canada. Since 2004, both the rate of volunteering, measured as the percentage of the population aged fifteen or older that engages in formal volunteering, and the average annual volunteer hours have declined (figure 1). Additionally, previous research suggests that the profile of the average civic volunteer is aging, as older volunteers are more likely to prefer weekly or daily commitments and younger volunteers are more likely to prefer short-term or one-time volunteer commitments. 8 8 Vancouver Foundation, “Vital Signs 2019,” 2019, https://vancouverfoundationvitalsigns.ca/reports/. In 2018, younger Canadians aged fifteen to twenty-two had the highest proportion of volunteers engaged in either formal or informal volunteering, or both (87 percent) but had fewer hours of volunteering, while older Canadians aged seventy-three to one hundred had the lowest proportion of volunteers (64 percent), but maintained consistent and significant hourly commitments. 9 9 Hahmann, “Volunteering Counts,” 12.

The COVID-19 crisis has had a further impact on volunteering and the charitable sector. While most forms of in-person volunteering were suspended, it is possible that older Canadians engaged in less in-person volunteering due to their elevated risk of contracting the virus, whereas younger people may have found creative ways to increase their volunteering online, by helping to solve some of the pandemic challenges faced by Canadians. 10 10 Hahmann, “Volunteering Counts,” 2. Examples could include finding local vaccine providers and connecting seniors with available appointments or facilitating the delivery of essential goods. In the absence of in-person connection, the proliferation of “digital helpers” who donated their time and resources to promote digital literacy among their fellow citizens elevated technology as a new platform for altruistic behaviour. 11 11 F. Mata and J. Dumoulin, “The New ‘Good Samaritans’: Digital Helpers During Pandemic Times in Canada,” SOCARXIV, March 28, 2021, 3.

However, the associated reduction in formal volunteer hours and decrease in volunteering within a civic context presents immediate concern for the charitable sector’s recovery. The charitable sector in Canada remains a key provider of social services and supports the health and well-being of members of society who may find it challenging to access the services they need. The charitable sector needs support to strengthen both the number and integration of volunteers, to access new forms of volunteering, and to combine intergenerational strengths in altruism and volunteerism. Many of the charities that serve the most vulnerable members of our society will continue to rely on formal volunteering, and the work that these charities do would benefit from the technological integration that younger volunteers have facilitated in informal settings. Moreover, the supervision, support, and screening available to volunteers within a formal volunteering context provides safeguards against exploitation of both volunteers and vulnerable members of society. The growth of formal volunteering, therefore, is something the government should actively encourage. The recovery of the charitable sector and the continued creation of a “culture of generosity” 12 12 R. Pennings, M. Van Pelt, and S. Lazarus, “A Canadian Culture of Generosity: Renewing Canada’s Social Architecture by Investing in the Civic Core and the ‘Third Sector,’” Cardus, October 2, 2009, 6, https://www.cardus.ca/research/communities/reports/a-canadian-culture-of-generosity/. among Canadians requires that volunteering be understood as socially generative: a contribution toward the public good.

The decline in total hours of formal volunteering by younger generations of Canadians is having a profound impact on Canada’s charitable sector, a sector that generates more than 7 percent of Canada’s GDP and employs more than two million people every year. 13 13 Report of the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector, “Catalyst for Change: A Roadmap to a Stronger Charitable Sector,” June 2019, 11, https://sencanada.ca/en/info-page/parl-42-1/cssb-catalyst-for-change/. This sector exists at the heart of Canadian civic society, occupying a space that mediates social policy and civic generosity, at its best an expression of the culture and identity of Canadians and Canadian values. 14 14 Pennings, Van Pelt, and Lazarus, “A Canadian Culture of Generosity,” 7. Its diminishment is undesirable, and policy that facilitates its growth and strength is more important than ever.

The perspective that volunteering is a social good is shared by the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector, which in the course of its initial investigation into the sector heard directly from 160 witnesses, received 90 written submissions from individuals and organizations, and received 695 electronic survey submissions, representing a range of organizations across the country. The committee’s conclusion in this initial report is direct and exacting: “The overall lack of respect for the enormous economic and social contributions of these organizations, their volunteers and their staff undermine its potential. Taken together, these impediments bar the road to finding better answers to complex problems and richer communities for all Canadians, in all regions of the country.” 15 15 Report of the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector, “Catalyst for Change,” 127.

The ease with which one can participate as a volunteer, then, is an important factor in the growth and encouragement of formal volunteering in Canada. Policy options that serve to facilitate this growth are not hard to find. We propose that one such area is evaluation of the purpose, methods, and access to vulnerable sector checks for prospective volunteers and charitable organizations.

A Case for Re-evaluation: The Context of Vulnerable Sector Checks

Volunteer screening is an important process for charitable organizations, to protect the clients they serve and to ensure the legitimacy and integrity of the organization. Volunteer screening is a broad, ten-step process that Public Safety Canada recommends charitable organizations use for screening prospective volunteers. 16 16 Public Safety Canada, “Best Practice Guidelines for Screening Volunteers,” January 31, 2018, https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/bpg-scrng-vls/index-en.aspx. These ten steps include safeguards such as completing reference checks for volunteers, engaging volunteers in safety and policy training, and maintaining regular and ongoing volunteer supervision as they perform their roles.

The process of obtaining a vulnerable sector check is the seventh step in this process and is mediated in Ontario by local police organizations or by the Ontario Provincial Police if the prospective volunteer lives in a rural location. Volunteer Canada originally developed this comprehensive screening process in partnership with the RCMP in the mid-1990s. It preceded and served as a resource for the development of the National Sex Offender Registry, one of the databases that police now consult when doing a vulnerable sector check. 17 17 Volunteer Canada, “Screening,” https://volunteer.ca/index.php?MenuItemID=368.

A vulnerable sector check is required when the applicant will be volunteering in a position of relative authority over or trust with vulnerable persons, as defined by the Criminal Records Act. 18 18 Government of Canada, Criminal Records Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-47, https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-47/page-2.html#h-135308. A vulnerable person is defined as any person who is dependent on others, or who may be at greater risk of being harmed by a person in a position of authority or trust over them. 19 19 Government of Canada, Criminal Records Act. Though not an exhaustive definition, this mainly refers to children and youth, the elderly, and those living with disability.

A vulnerable sector check is the most comprehensive of the three main types of police checks in Ontario. It involves searches of national and local police databases, and the information disclosed is governed by law. The results of the check are disclosed only to the applicant, and the applicant can then choose to disclose these results to the requesting organization or employer. The other two types of police checks in Ontario are a criminal record check and a criminal record and judicial matters check. Table 1 describes the information that is disclosed for each of these in Ontario.

Vulnerable Sector Checks: The Impact on Volunteering

As vulnerable sector checks form part of the screening process, then, it is important to consider other ways in which they may affect the charitable sector. Do they present barriers to volunteers and affect the ability of Ontarians to engage in volunteerism?

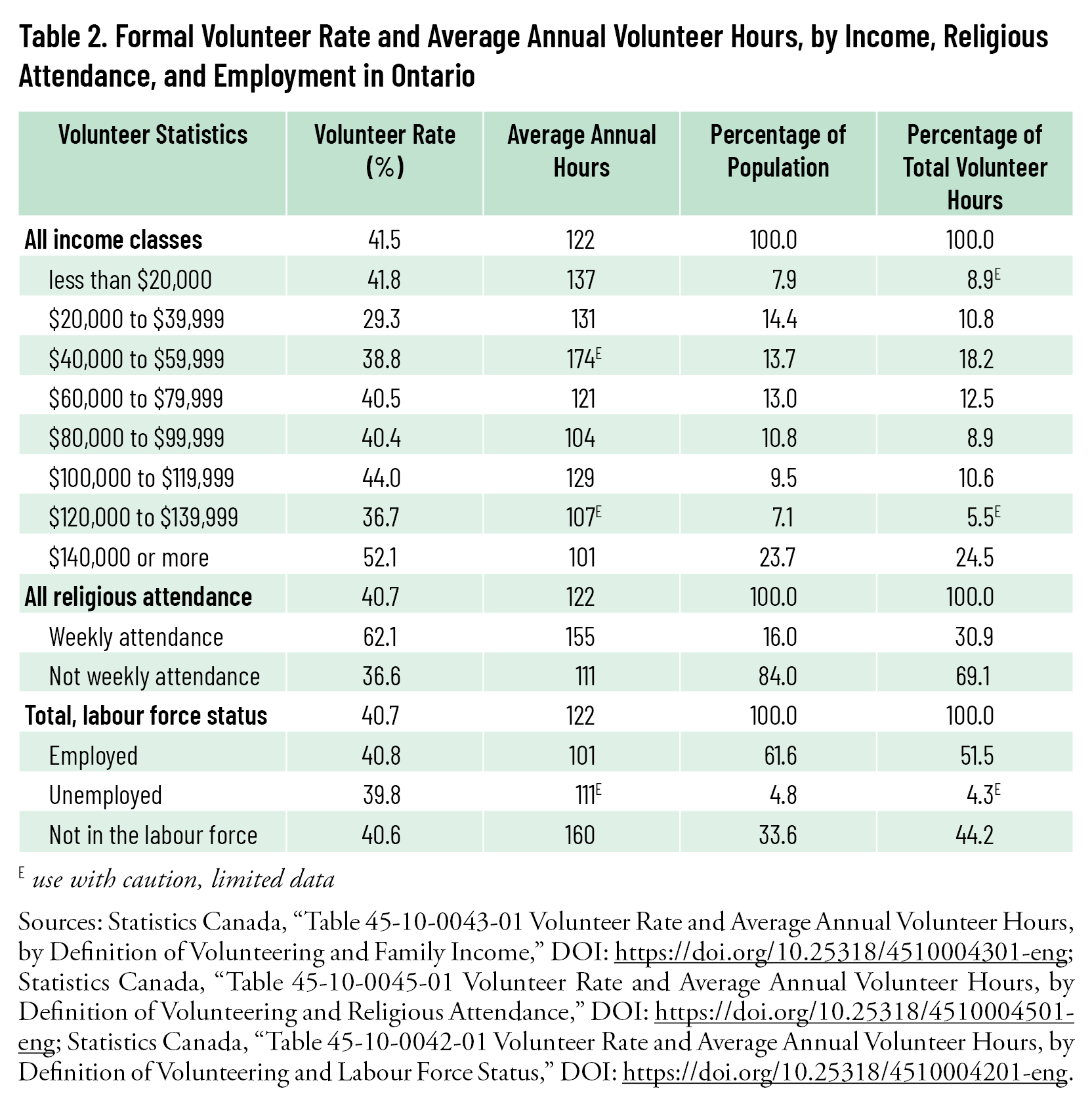

Table 2 demonstrates the most recent data on volunteer rate and average annual volunteer hours by income, religion, and employment in Ontario. These Statistics Canada data describe engagement in formal volunteering across society. Notably, those whose income is less than $20,000 contribute one of the highest average annual hours toward formal volunteering, as do those who are unemployed or not in the labour force, 40 percent of whom engage in formal volunteering. Those who attend weekly religious services have the highest rate of formal volunteering, with 62.1 percent of this population contributing an average of 155 annual hours to the charitable sector.

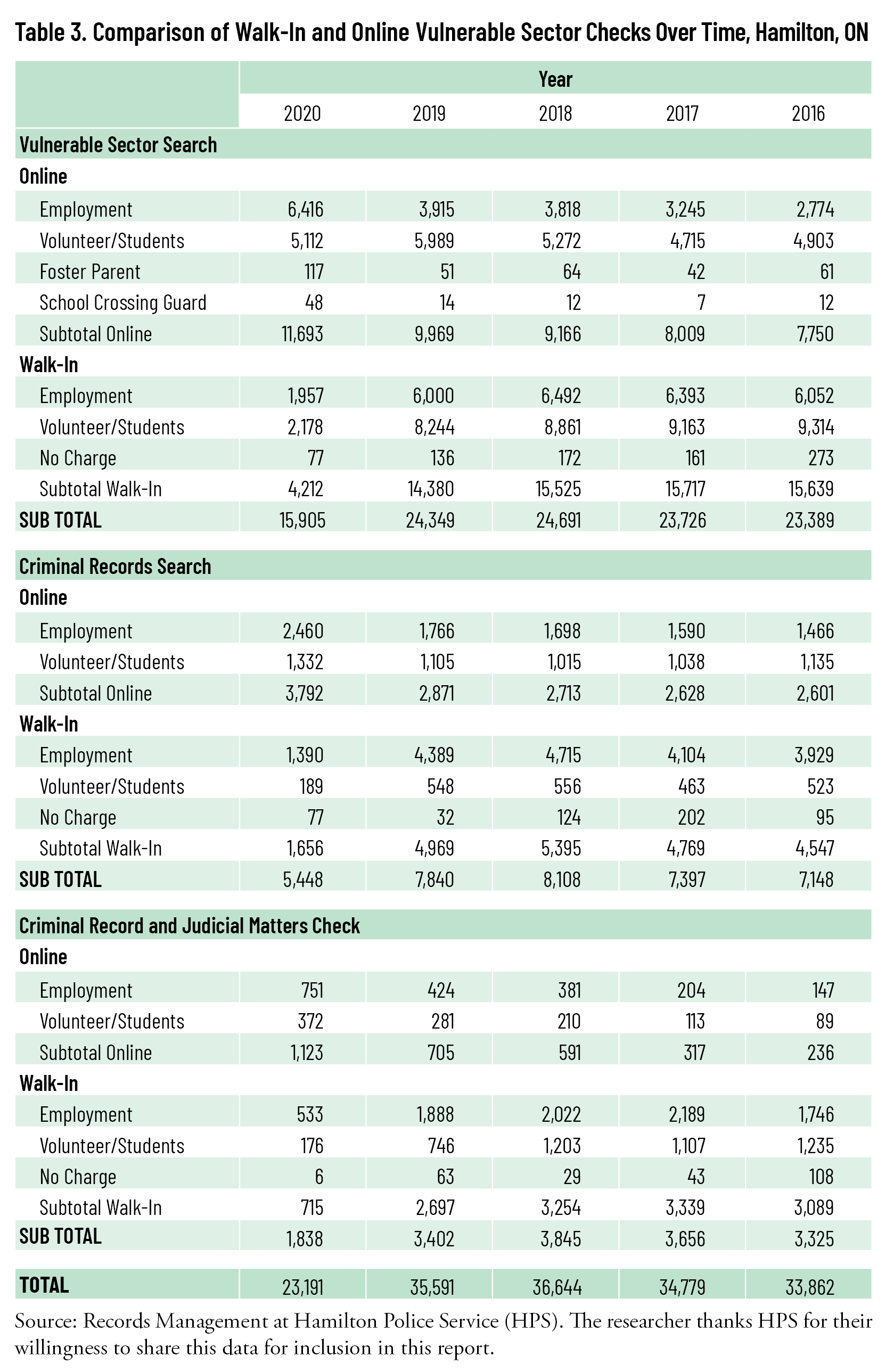

It is unclear what percentage of these volunteers contribute in roles that require a vulnerable sector check. As demonstrated in table 3, the Hamilton Police Service processes approximately 25,000 vulnerable sector checks each year for both volunteer and employment purposes, suggesting the number of vulnerable sector checks processed for volunteers in Ontario overall is significant. Notably, in 2019, the last non-pandemic year, the number of vulnerable sector checks processed in Hamilton exceeded the number of criminal record checks and criminal record and judicial matters checks by 16,000 and 20,000 respectively.

It is challenging to quantify the impact of the process of vulnerable-sector screening and the requirement for vulnerable sector checks on the volunteer population that drives the charitable sector. However, there are several arguments that acknowledge the complexity and burden the vulnerable sector check requirement places on potential volunteers and on the charitable organizations they serve.

While quantitative investigation into the efficacy of vulnerable sector checks is beyond the scope of this paper, in what follows we provide a qualitative description of both personal barriers for prospective volunteers and systemic challenges for charitable organizations. Nevertheless, the embedded place of vulnerable sector checks within the vulnerable-sector screening process is a current reality and a valuable step in the process. The commitment to transparency in the protection of children, youth, and vulnerable members of society is both admirable and essential. We do not here advocate for their removal. Indeed, it is possible that the presence of vulnerable sector checks acts as a deterrent to those who might otherwise seek to use volunteer pathways to harm children, youth, or other vulnerable persons, and that self-selection out of the process of getting a vulnerable sector check will offer some protection for charitable organizations and employers.

Personal Barriers to Vulnerable Sector Check Requirements for Prospective Volunteers

There are various requirements that applicants must meet in order to apply for a vulnerable sector check in Ontario.

Cost

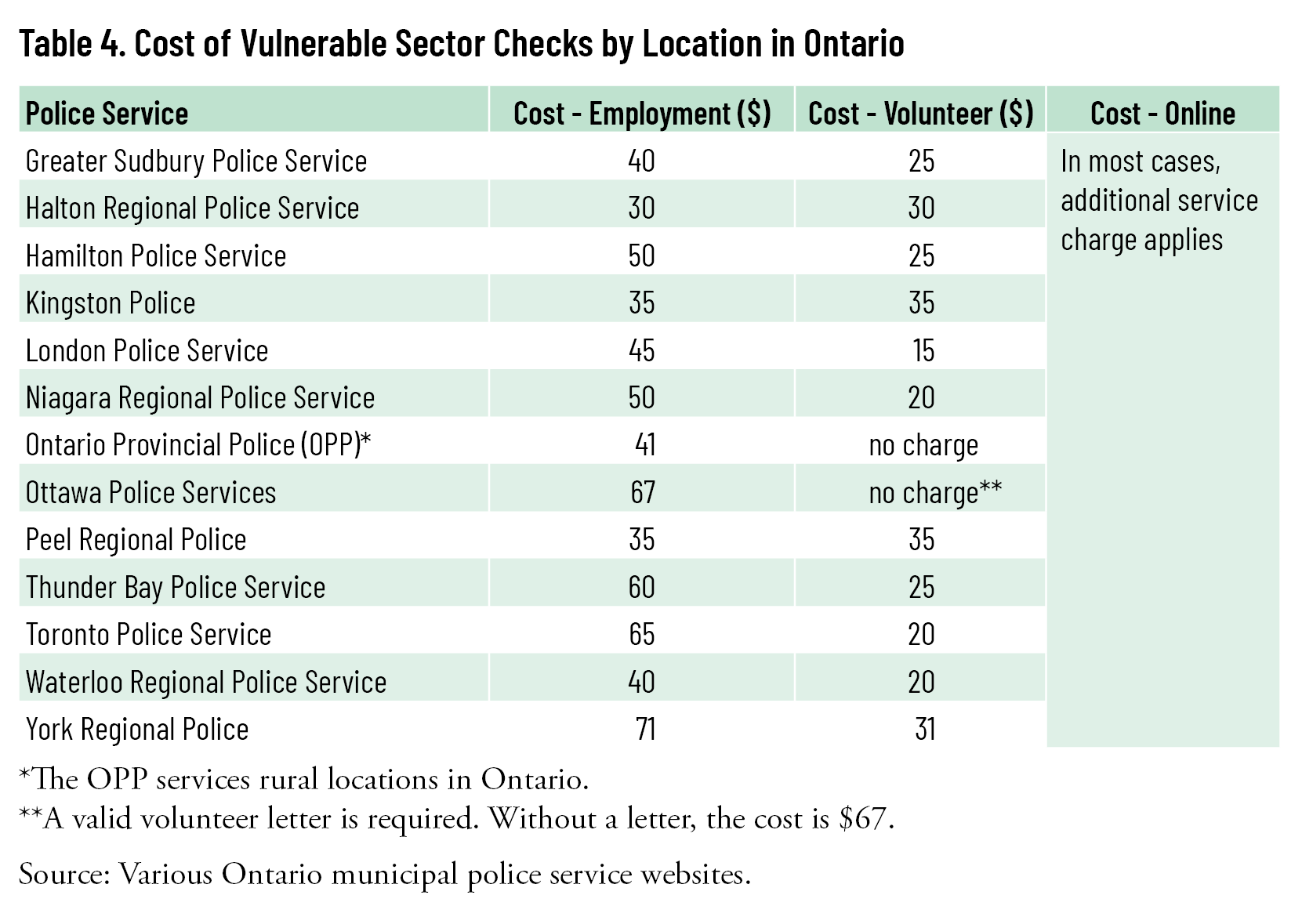

The cost to apply varies. Usually the cost is significantly higher to obtain a vulnerable sector check for employment purposes than it is for volunteer purposes, and some organizations will choose to absorb the cost on behalf of their employees or volunteers. In some cases, rates are reduced or waived for applicants under the age of eighteen. Most volunteers, however, pay out of pocket for their own vulnerable sector check, and must do this as often as an updated check is required by their charitable organization. The cost to obtain a vulnerable sector check for volunteer purposes can vary by region within Ontario. The cost from a sample of regional police services is listed in table 4. In most cases where an online option to obtain a vulnerable sector check is a possibility, additional service charges are added by the company that has been outsourced to verify identity through the credit history of the applicant.

There are also private services that provide police-record checks. Vulnerable sector checks obtained from these services, however, may be limited in the information they are able to supply. The cost associated with these services may vary; one example is $33 for an enhanced criminal record check. 20 20 Plan to Protect, “Criminal Record Checks—Canada,” https://www.plantoprotect.com/en/services/screening-and-crim-checks/criminal-record-checks-canada/.

Identification

Whether applying in person or online, applicants must provide two verified government-issued pieces of identification. In some cases, identification must be verified in person or by a current photograph. In Ontario, in order to qualify for a lower fee for the check, an identification letter submitted by the charitable organization stating the applicant’s role and relevancy must accompany the application.

Credit History

Online applications for vulnerable sector checks require verification of identification. In provinces that provide this option, including Ontario, credit history is used to verify the government identification that the applicant provides, through external security services. In order to gauge the accessibility of this process, we engaged the process of ordering a vulnerable sector check through local police service online. We found that in addition to a ready knowledge of one’s credit history, this process requires fluency in English and an ability to respond quickly under the pressure of timed questions.

Time and Accessibility

Besides the time spent in applying, the processing time can vary depending on findings. If a match is found between the applicant’s information (name, date of birth, etc.) and information in the National Sex Offender Registry, the applicant will have to come to the police station for fingerprinting. The cost for fingerprinting can vary but is usually over and above the initial vulnerable sector check cost.

The ability to apply online can save time for some applicants. Yet this option may be inaccessible to those who do not have secure internet access, who cannot verify their identification with credit history, or who may find the process inaccessible due to language or other barriers.

Systemic Challenges of Vulnerable Sector Check Requirements for Charitable Organizations

Despite the recommendations of many police services that additional steps for volunteer screening should be undertaken, vulnerable sector checks in their current form are a core component for organizations in their commitment to protect vulnerable persons and as a safeguard against legal liability. It is worth considering that many factors limit the efficacy of these checks in accomplishing their purpose.

Time

First, they are time-limited, valid only up to the date they are issued. 21 21 Halton Regional Police Service, “Police Record Checks, FAQ,” https://www.policesolutions.ca/checks/services/halton/index.php?page=faq#q05; Hamilton Police Services, “Get a Background Check, FAQ,” https://hamiltonpolice.on.ca/how-to/get-background-check; London Police Service, “Police Record Checks, FAQ,” https://www.policesolutions.ca/checks/services/london/index.php?page=faq#q06. This necessitates repeated access to and requirements for vulnerable sector checks, and each organization may have slightly different standards in this regard. Some require a renewed check each year, while others may require it every two or three years. Second, vulnerable sector checks can take time to complete, especially if a match is found to a prospective volunteer’s birth date or other information and subsequent fingerprinting is required. The importance of volunteers in emergency response to natural disasters is one example of a situation in which it would is not be possible to wait for a police check to be completed. As Ontario together with the rest of Canada faces increasing severe weather events due to climate change, recognizing the potential for an established immediate volunteer base (with appropriate screening completed) is essential.

Applicability to Youth

For Ontario’s youth, volunteering is currently a requirement for a high school diploma, ostensibly to encourage the development of patterns of civic engagement and generosity. The elimination of cost barriers for these youth aligns with the intent of this goal. Additionally, it is worth noting the limited relevance of vulnerable-sector screening for youth. 22 22 Hamilton Police Services, “Get a Background Check, FAQ.” For those under eighteen, it is unnecessary to apply for a vulnerable sector check, as records are protected under the Youth Criminal Justice Act. These checks are also highly unlikely to provide meaningful results for volunteer applicants between eighteen and twenty-five years of age. 23 23 In the mid-1990s, the RCMP eliminated the possibility of record suspensions (pardons) for Schedule 1 sex offenses—sexual offences against children and vulnerable persons. The National Sex Offender Registry includes names of those convicted and pardoned prior to this decision, or of those who have been pardoned for other indictable offences. Since this decision, Schedule 1 sexual offences for which there has been a conviction will appear on all types of criminal background checks—greatly narrowing the relevancy of vulnerable-sector checks for younger applicants. When the trend toward shorter, one-time volunteer commitments for youth is considered in conjunction with the reality that vulnerable sector checks have limited applicability for this age group, it is possible the high volume and cost of vulnerable sector checks could be reduced through alternative requirements such as criminal record checks and reference requirements.

The Limitations of Justice in Prosecuting Sexual Offence

Third, given that sexual assault is both under-reported and under-prosecuted, the criminal justice system is limited in apprehending, charging, and prosecuting sexual offenders. 24 24 Recent Statistics Canada reports indicate that only 6 percent of sexual assaults are reported to police. Of those that are reported, only one in ten (12 percent) result in a criminal conviction. Women are five times more likely than men to be victims of sexual assault and account for 92 percent of police reported sexual assaults; women with a disability are victims of sexual assault at rate of four times higher than able-bodied women. Indigenous women and girls are victims of sexual assault at a rate of three times higher than non-Indigenous women and girls. Data from A. Cotter, “Criminal Victimization in Canada, 2019,” Statistics Canada, August 25, 2021, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00014-eng.pdf?st=enrYdaE7; C. Rotenberg, “From Arrest to Conviction: Court Outcomes of Police-Reported Sexual Assaults in Canada, 2009 to 2014,” Canadian Center for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada, October 26, 2017, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/54870-eng.pdf?st=WIoUIAzk; S. Conroy, “Family Violence in Canada: A Statistical Profile, 2019,” Statistics Canada, March 2, 2021; Canadian Women’s Foundation, “The Facts About Sexual Assault and Harassment,” https://canadianwomen.org/the-facts/sexual-assault-harassment/. Employers and charitable organizations need to engage in more robust screening than relying solely on vulnerable sector checks. In addition, an intersectional understanding of who gets charged, who gets pardoned, and who does not is important when considering the results of vulnerable-sector screening for charitable organizations. 25 25 T.C. Paisana, “Criminal Record Checks—Report of the Working Group” (presented at a joint session of the Civil and Criminal Sections, Uniform Law Conference of Canada, August 2017), https://www.ulcc-chlc.ca/ULCC/media/EN-Annual-Meeting-2017/Criminal-Records-Check.pdf. The necessity to obtain a vulnerable sector check can limit the ability of those who may have had interactions with police to volunteer, particularly those of marginalized populations. As some charitable organizations, such as anti-human-trafficking organizations and victim services, seek to include as valuable and essential voices representation from the same populations they serve, these potential volunteers face barriers in obtaining this requirement.

Eligibility of Minority Populations

Vulnerable sector checks require a history within Canada in order to be effective, and thus they exclude those who have recently arrived in the country. Immigrants and refugees may also encounter barriers of cost, language, or absence of a credit history. Considering Ambrosini and Artero’s argument for volunteering as acts of citizenship, 26 26 Ambrosini and Artero, “Immigrant Volunteering,” 14. the skill and talent of many new Canadians remains an untapped resource.

Geography

Vulnerable sector checks rely on databases that are limited in geography, meaning that significant past history may not be uncovered if the applicant has moved from one region to another. Foreign criminal history is not included, as per international regulations of INTERPOL. 27 27 Royal Canadian Mounted Police, “Dissemination of Criminal Record Information Policy,” June 24, 2014, https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/dissemination-criminal-record-information-policy. Canada’s National Sex Offender Registry contains data only on offences committed in Canada. Because an applicant may apply for a vulnerable sector check only within the locale in which they live, limited information may be uncovered for applicants with international or otherwise geographically varied backgrounds.

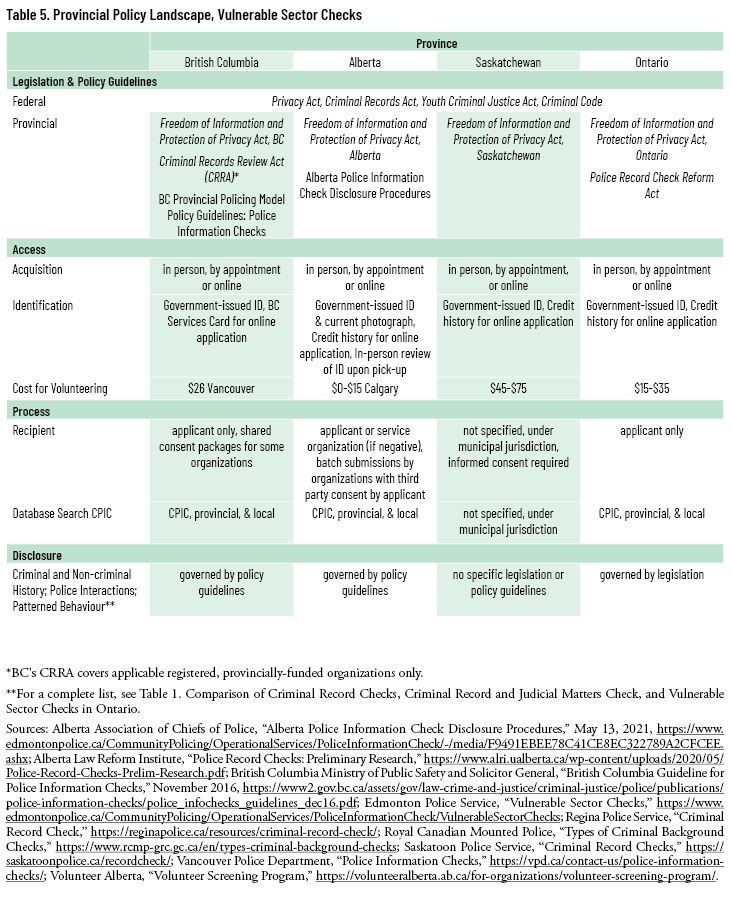

Furthermore, Canada has not standardized the process of obtaining a vulnerable sector check. While there are some basic similarities, who can access, how they can be accessed, and what is included or not included on these checks can vary by province and municipality (table 5). The presence of provincial policing services in some provinces but not others (for example in Ontario but not in Alberta) adds another layer of communication challenge between municipal services and federal policing. In 2015, Ontario passed the Police Record Check Reform Act in order to standardize the process across the province and safeguard the privacy of youth and adults who may have had encounters with law enforcement that have no relation to concerns about vulnerable persons. This legislation defined the different types of police checks (of which vulnerable sector checks are the most comprehensive), limited and standardized the type of information released on each type of police check, and ensured that disclosure practices recognized the applicant as the primary recipient of results. 28 28 Solicitor General of Ontario, “Ontario Passes Police Record Checks Legislation,” December 1, 2015, https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/35142/ontario-passes-police-record-checks-legislation.

While these reforms helped to standardize the process in Ontario, they highlight a tension between the aims of vulnerable-sector screening and the protection of privacy, and demonstrate a need for deep understanding of multiple factors that affect the efficacy of the check in achieving its goals. There are many areas for future research to explore the real ability of vulnerable sector checks to safeguard the charitable sector and vulnerable populations.

Liability Concerns for Charitable Organizations and Employers

Even though the vulnerable sector check is one small component of a larger volunteer screening process, for many charitable organizations, these checks have been viewed as a gold standard in their own right, taking on an outsized role within the screening process in importance and efficacy in protection of vulnerable clients. Vulnerable sector checks are required by employers and charitable organizations far more often than other types of police checks. In part, this is clearly due to the fact that most charitable organizations serve vulnerable populations. However, an unintended effect of vulnerable sector check requirement policy may be that an organization’s leadership adopts a perspective that because this check is the most comprehensive police check available, it provides the greatest amount of protection to the organization. The result is an over-reliance on vulnerable sector checks, in many instances due to the reality that most charitable organizations are small and lack the capacity to engage in the robust volunteer education, training, and supervision that the full volunteer screening process requires. The requirement of most charitable organizations for renewed or regular vulnerable sector checks, for example, is not necessary: after the first vulnerable sector check has been completed, any conviction will show up on a regular criminal record check long before a pardon has been issued. These additional vulnerable sector checks add cost and redundancy to the application process.

Additionally, vulnerable sector checks are typically valid only for the organization that has requested the check, meaning that some applicants must apply for multiple vulnerable sector checks to fulfill the variety of volunteering or employment obligations they may have. 29 29 Halton Regional Police Service, “Police Record Checks.” Charitable organizations that accept a vulnerable sector check fulfilled for other volunteer purposes may accept a level of increased risk to their organization. For charitable organizations, the secure storage and management of vulnerable sector checks requires staff time, and for organizations that subsidize a portion or all of the vulnerable sector check cost, a significant portion of their allocated budget is affected.

In its report titled “Catalyst for Change: A Roadmap to a Stronger Charitable Sector,” the Senate Special Committee on the Charitable Sector made several recommendations for improvement. It is noteworthy that the Senate Committee’s third recommendation is as follows:

That the Government of Canada, through the Public Safety Minister, work with provincial and territorial counterparts and the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police to seek ways to alleviate a financial burden on low-budget organizations for needed police checks on volunteers. 30 30 Report of the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector, “Catalyst for Change,” 14.

Policy Options for Increased Volunteerism

The longevity and vibrancy of Canada’s charitable sector and volunteerism is indicative of its culture of generosity. Traditionally a sector celebrated for its diversity and innovation, today it needs strengthening and attention, as volunteer rates decline and the charities struggle to maintain their presence in local communities. 31 31 Report of the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector, “Catalyst for Change,” 127. The role of government in creating conditions for increased volunteer participation is important and relevant for strengthening the charitable sector as a whole. Providing effective inducements toward volunteering capacity is one such policy goal.

Previous policies that sought to incentivize giving include the first-time-donor super credit, in effect between 2013 and 2017, as well as the ongoing requirement for high school students to complete forty hours of volunteer service in order to obtain a high school diploma. Research demonstrates that the first-time-donor super credit was not a successful incentive for financial giving; the number of donors stayed consistent during that time. 32 32 R. Buchanan, “Charitable Donation Tax Credits in Canada: Equitable Concerns and Options for Reform,” Canadian Bar Association, July 15, 2020, 9, https://www.cba.org/Sections/Charities-and-Not-for-Profit-Law/Resources/Resources/2020/Winner-of-2020-Charity-Law-Student-Essay-Contest. Additionally, it is unclear whether the high school requirement is effective beyond an initial increase in the number of short-term commitments of young people. 33 33 S.M. Pancer, S.D. Brown, A. Hendersen, K. Ellis-Hale, “The Impact of High School Mandatory Community Service Programs on Subsequent Volunteering and Civic Engagement,” Knowledge Development Centre, Imagine Canada, February 7, 2007, 25, http://sectorsource.ca/sites/default/files/resources/files/WLU_MandatoryVolunteering_Feb07_2007.pdf. Further research is needed to understand whether there is a lasting or cultural impact on a renewed civic engagement for these youth, and whether this requirement increases or decreases volunteer involvement over time.

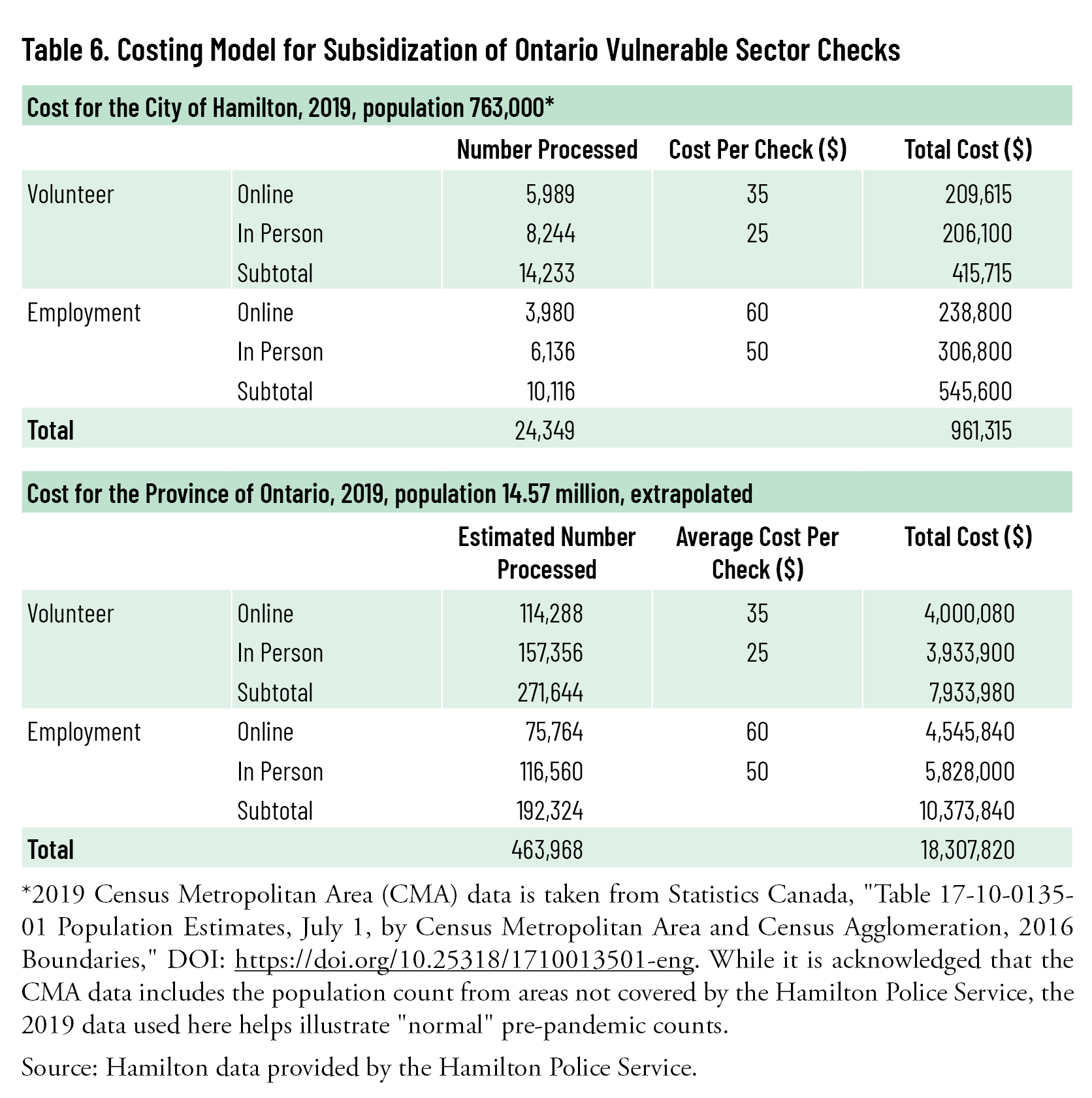

A straightforward though modest policy proposal of this research paper is that the provincial government fully subsidize the cost of vulnerable sector checks, and any associated fingerprinting requirement, when accessed for volunteer purposes, across the province. If funding for this cost is transferred to municipal police services based on the number of checks processed each year, those charitable organizations that currently absorb the cost for prospective volunteers will see this burden alleviated. A costing model for this policy proposal is detailed in table 6. Based on our model, the cost to the province for subsidizing vulnerable sector checks for volunteers, at $8 million, is just 0.005 percent of the total $173 billion provincial budget for program expenses for 2021–2022. 34 34 Government of Ontario, “2021 Ontario Budget, Chapter 3: Ontario’s Fiscal Plan and Outlook,” https://budget.ontario.ca/2021/chapter-3.html#section-2. This policy would eliminate one potential barrier to the vulnerable screening process for many who currently cannot access it.

A Brief Response to Ontario’s Recent Announcement

In March 2022, the Ontario government announced that it would eliminate all fees for criminal record checks and criminal records and judicial matters checks for volunteer purposes. 35 35 H. Alberga, “Police Record Checks Will Soon Be Free for Volunteers in Ontario,” CTV News, March 30, 2022, https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/police-record-checks-will-soon-be-free-for-volunteers-in-ontario-1.5840877. This announcement came into effect on April 1, 2022. While this effort to reduce the burden on volunteers is welcome, it should be noted that it does not apply to vulnerable sector checks, which are the largest proportion of checks processed for volunteer and employment purposes. Table 5 demonstrates the significantly higher proportion of vulnerable sector check requirements, meaning this announcement makes little headway in providing help to the charitable sector. Moreover, additional processing fees remain for online services and for fingerprinting, regardless of government legislation. Last, it should be recognized that this was a legislative elimination of fees only: the government has not provided any actual subsidy to municipal police services or to the charitable sector but has simply required municipalities to absorb this cost through their tax base. The consequence is that some police services have increased the fee for criminal record checks for employment purposes: Hamilton Police Services, for example, has increased the cost of criminal record checks from $40 to $50, and of criminal record and judicial matters checks from $45 to $50. While our paper focuses on the burden of vulnerable sector checks on volunteers and the charitable sector, it is worth considering that employment sectors requiring vulnerable sector checks usually fall within the care industries: long-term care, education, disability services, and health care. Many of the jobs in these sectors are low pay and employ disproportionate numbers of women and immigrants—meaning that this announcement creates an increased barrier for these essential workers.

By far the best policy model for the government of Ontario to adopt would be to subsidize all police-record checks, including vulnerable sector checks for both employment and volunteer purposes. According to our model, the combined cost to subsidize both volunteer and employment vulnerable sector checks would be approximately $18.3 million, or 0.01 percent of Ontario’s $173 billion budget for 2021.

This is a policy that can be implemented at relatively low cost to government and offers immediate, significant cost relief for volunteers and charitable organizations. Additionally, intangible, long-term benefits of increased volunteer participation and engaged citizenry will strengthen social cohesion and permeate communities with active bonds of trust and relationship. The benefits of volunteers to local communities are significant and provide government with deep return on a small investment.

Long term, we propose that the government partner with the charitable sector to evaluate the ongoing efficacy of vulnerable sector checks and the ability of the charitable sector to maintain effective volunteer screening, and work toward creating a national standardized process by which vulnerable sector checks remain current and effective. Toward this end, we propose consideration of such international volunteer registry programs as Scotland’s Protecting Vulnerable Groups Scheme managed by Disclosure Scotland 36 36 Government of Scotland, “The Protecting Vulnerable Groups Scheme,” May 9, 2022, https://www.mygov.scot/pvg-scheme. or the Blue Card Services system in Queensland, Australia. 37 37 Queensland Government, “The Blue Card System Explained,” February 6, 2022, https://www.qld.gov.au/law/laws-regulated-industries-and-accountability/queensland-laws-and-regulations/regulated-industries-and-licensing/blue-card/system/system-explained.

Finally, we advocate for the development and strengthening of the ten-step volunteer screening process recommended by Public Safety Canada throughout the charitable sector, in order to reduce reliance on vulnerable sector checks and to increase the methods and capacity of the charitable sector and employers for the protection of vulnerable persons. There are various ways this could be mediated, ideally through an organization with national reach or through a national volunteer registry program. 38 38 Volunteer Scotland is an excellent example serving multiple functions: as a national volunteer registry that connects volunteers to local organizations, and as a resource and training center for volunteers and charitable organizations: www.volunteerscotland.net. Given Canada’s size and variation within provincial jurisdictions, a two-tiered approach may be necessary.

Conclusion

The strength and vitality of Canada’s charitable sector depends on civic engagement and the support of formal volunteering commitments. As Canada welcomes new immigrants to its cities and continues to face challenges in climate emergency events, more formal volunteering will be needed in these areas and therefore should be encouraged and thus should be encouraged in these areas. While volunteer screening is necessary and important, vulnerable sector checks present a barrier for volunteers and charitable organizations in terms of cost and accessibility. To mitigate this, we propose a government subsidy of vulnerable sector checks for volunteer purposes, and a long-term commitment to the evaluation of vulnerable sector checks and their use, and capacity-building within the charitable sector toward robust understanding of volunteer screening.

References

Alberta Association of Chiefs of Police. “Alberta Police Information Check Disclosure Procedures.” May 13, 2021. https://www.edmontonpolice.ca/CommunityPolicing/OperationalServices/PoliceInformationCheck/-/media/F9491EBEE78C41CE8EC322789A2CFCEE.ashx.

Alberta Law Reform Institute. “Police Record Checks: Preliminary Research.” March 2020. https://www.alri.ualberta.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Police-Record-Checks-Prelim-Research.pdf.

Alberga, H. “Police Record Checks Will Soon Be Free for Volunteers in Ontario.” CTV News, March 30, 2022. https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/police-record-checks-will-soon-be-free-for-volunteers-in-ontario-1.5840877.

Ambrosini, M., and M. Artero. “Immigrant Volunteering: A Form of Citizenship From Below.” International Society for Third-Sector Research, January 26, 2022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-022-00454-x.

Baines, S., and I. Hardill. “‘At Least I Can Do Something’: The Work of Volunteering in a Community Beset by Worklessness.” Social Policy and Society 7, no. 3 (2008): 307–17.

British Columbia Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General. “British Columbia Guideline for Police Information Checks.” November 2016. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/criminal-justice/police/publications/police-information-checks/police_infochecks_guidelines_dec16.pdf.

Buchanan, R. “Charitable Donation Tax Credits in Canada: Equitable Concerns and Options for Reform.” Canadian Bar Association, July 15, 2020. https://www.cba.org/Sections/Charities-and-Not-for-Profit-Law/Resources/Resources/2020/Winner-of-2020-Charity-Law-Student-Essay-Contest.

Canadian Women’s Foundation. “The Facts About Sexual Assault and Harassment.” https://canadianwomen.org/the-facts/sexual-assault-harassment/.

Conroy, S. “Family Violence in Canada: A Statistical Profile, 2019.” Statistics Canada, March 2, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00001-eng.pdf?st=Zn00A3w7.

Cotter, A. “Criminal Victimization in Canada, 2019.” Statistics Canada, August 25, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2021001/article/00014-eng.pdf?st=enrYdaE7.

Edmonton Police Service. “Vulnerable Sector Checks.” https://www.edmontonpolice.ca/CommunityPolicing/OperationalServices/PoliceInformationCheck/VulnerableSectorChecks.

Government of Canada. Criminal Records Act. R.S.C. 1985, c. C-47. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/C-47/page-2.html#h-135308.

Government of Ontario. “Police Record Checks.” April 1, 2022. https://www.ontario.ca/page/police-record-checks#section-1.

———. “2021 Ontario Budget, Chapter 3: Ontario’s Fiscal Plan and Outlook.” https://budget.ontario.ca/2021/chapter-3.html#section-2.

Government of Scotland. “The Protecting Vulnerable Groups Scheme.” May 9, 2022. https://www.mygov.scot/pvg-scheme.

Hahmann, T. “Volunteering Counts: Formal and Informal Contributions of Canadians in 2018.” Statistics Canada, April 23, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2021001/article/00002-eng.pdf?st=a1wMYxaz.

Halton Regional Police Service. “Police Record Checks, FAQ.” https://www.policesolutions.ca/checks/services/halton/index.php?page=faq#q05.

Hamilton Police Service. “Get a Background Check, FAQ.” https://hamiltonpolice.on.ca/how-to/get-background-check.

———. “Report Comparison.” https://www.policesolutions.ca/checks/services/hamilton/business.php?page=compare.

Landry, A., C. Price, and R. Colwell. “The Rising Importance of Volunteering to Address Community Emergencies.” Canadian Journal of Emergency Management 2, no 1 (2022): 56–67.

London Police Service. “Police Record Checks, FAQ.” https://www.policesolutions.ca/checks/services/london/index.php?page=faq#q06.

Mata, F., and J. Dumoulin. “The New ‘Good Samaritans’: Digital Helpers During Pandemic Times in Canada.” SOCARXIV, March 28, 2021.

Paisana, T.C. “Criminal Record Checks—Report of the Working Group.” Presented at a joint session of the Civil and Criminal Sections, Uniform Law Conference of Canada, August 2017. https://www.ulcc-chlc.ca/ULCC/media/EN-Annual-Meeting-2017/Criminal-Records-Check.pdf.

Pancer, S.M., S.D. Brown, A. Hendersen, and K. Ellis-Hale. “The Impact of High School Mandatory Community Service Programmes on Subsequent Volunteering and Civic Engagement.” Knowledge Development Centre, Imagine Canada, February 7, 2007. http://sectorsource.ca/sites/default/files/resources/files/WLU_MandatoryVolunteering_Feb07_2007.pdf.

Pennings, R., M. Van Pelt, and S. Lazarus. “A Canadian Culture of Generosity: Renewing Canada’s Social Architecture by Investing in the Civic Core and the ‘Third Sector.’” Cardus, October 2, 2009. https://www.cardus.ca/research/communities/reports/a-canadian-culture-of-generosity/.

Plan to Protect. “Criminal Record Checks—Canada.” https://www.plantoprotect.com/en/services/screening-and-crim-checks/criminal-record-checks-canada/.

Public Safety Canada. “Best Practice Guidelines for Screening Volunteers.” January 31, 2018. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/bpg-scrng-vls/index-en.aspx.

Queensland Government. “The Blue Card System Explained.” February 6, 2022. https://www.qld.gov.au/law/laws-regulated-industries-and-accountability/queensland-laws-and-regulations/regulated-industries-and-licensing/blue-card/system/system-explained.

Regina Police Service. “Criminal Record Check.” https://reginapolice.ca/resources/criminal-record-check/.

Report of the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector. “Catalyst for Change: A Roadmap to a Stronger Charitable Sector.” June 2019. https://sencanada.ca/en/info-page/parl-42-1/cssb-catalyst-for-change/.

Rodell, J.B. “Finding Meaning Through Volunteering: Why Do Employees Volunteer and What Does It Mean for Their Jobs?” Academy of Management Journal 56, no. 5 (2013): 1274–94.

Rotenberg, C. “From Arrest to Conviction: Court Outcomes of Police-Reported Sexual Assaults in Canada, 2009 to 2014.” Canadian Center for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada, October 26, 2017. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/85-002-x/2017001/article/54870-eng.pdf?st=WIoUIAzk.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police. “Dissemination of Criminal Record Information Policy.” June 24, 2014. https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/dissemination-criminal-record-information-policy.

———. “Types of Criminal Background Checks.” https://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/types-criminal-background-checks.

Saskatoon Police Service. “Criminal Record Checks.” https://saskatoonpolice.ca/recordcheck/.

Sinha, M. “Volunteering in Canada, 2004 to 2013.” Statistics Canada, June 18, 2015. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2015003-eng.pdf?st=1TPNDJGh.

Solicitor General of Ontario. “Ontario Passes Police Record Checks Legislation.” Government of Ontario, December 1, 2015. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/35142/ontario-passes-police-record-checks-legislation.

Statistics Canada. “Table 45-10-0042-01 Volunteer Rate and Average Annual Volunteer Hours, by Definition of Volunteering and Labour Force Status.” DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/4510004201-eng.

———. “Table 45-10-0043-01 Volunteer Rate and Average Annual Volunteer Hours, by Definition of Volunteering and Family Income.” DOI:https://doi.org/10.25318/4510004301-eng.

———. “Table 45-10-0045-01 Volunteer Rate and Average Annual Volunteer Hours, by Definition of Volunteering and Religious Attendance.” DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/4510004501-eng.

———. “Table 17-10-0135-01 Population Estimates, July 1, by Census Metropolitan Area and Census Agglomeration, 2016 Boundaries.” DOI: https://doi.org/10.25318/1710013501-eng.

Vancouver Foundation. “Vital Signs 2019.” 2019. https://vancouverfoundationvitalsigns.ca/reports/.

Vancouver Police Department. “Police Information Checks.” https://vpd.ca/contact-us/police-information-checks/.

Volunteer Alberta. “Volunteer Screening Program.” https://volunteeralberta.ab.ca/for-organizations/volunteer-screening-program/.

Volunteer Canada. “Screening.” https://volunteer.ca/index.php?MenuItemID=368.

Volunteer Scotland. “About Us.” https://www.volunteerscotland.net/about-us/.