Education in America

it doesn’t matter where you identify on the political spectrum, there is consensus that America’s education system is facing a crisis.

Unfortunately, that is where the consensus often ends.

For some, it’s a lack of resources, inequality, and the capacity for American educators to deliver desired outcomes. For others, the blame goes to bloated bureaucracies, powerful unions, and abandoned educational basics that contribute to unsatisfactory results. Mention standardized tests, classroom sizes, or pedagogical approaches, and divided opinion follows. Despite the disagreement, however, almost all agree that the current state of affairs is not acceptable. Experts and advocates reference international studies that show the United States trailing behind other countries in educational outcomes. There is need for change.

Part of this debate concerns the place of a centralized, government-run public school system. Education delivery in the United States typically began in local communities and missionary schools. However, “common” schools, often associated with the pioneering work of Horace Mann in the nineteenth century became the norm early on in American history. What is significant about this move is the contention not only that common schools were necessary to ensure that all children received a quality education to enhance their personal prospects of success, but also that society needed a common education system to promote a common set of civic values and democracy. From its inception, the notion of a shared common good was embedded in the very concept of the public school system.

The US Department of Education’s report A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform is perhaps even more imperative today than when it was first written.

THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES need to know that individuals in our society who do not possess the levels of skill, literacy, and training essential to this new era will be effectively disenfranchised, not simply from the material rewards that accompany competent performance, but also from the chance to participate fully in our national life. A high level of shared education is essential to a free, democratic society and to the fostering of a common culture, especially in a country that prides itself on pluralism and individual freedom. 1 1 US Department of Education, A Nation at Risk, (April 1983), https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/NatAtRisk/risk.html.

This norm, however, does not negate the reality that from its earliest beginnings, this sense of the common good has also found expression in a plurality of delivery models, in both government and non-government run schools. America’s educational story is one of change, diversity, and innovation from the earliest days to the present. This is witnessed with the first colonists to land in New England and the growth of missionary schools established by Protestants and Catholics reflecting distinct confessional outlooks, to the ascendance of Horace Mann’s common schools in the nineteenth century, to the Jewish and Islamic schooling movements in the twentieth century, and the growth today of state-sponsored parental-choice programs and charter schools, as well as the independent school sector. Schools today in their many varieties must now prepare students not only for an increasingly complex and competitive global economy but also equip them with the civic virtues and skills necessary for an increasingly complex and diverse democracy.

The last few decades have seen an appreciable expansion of educational options within both government and non-government sectors. The traditional “public” school district has become more diverse with the growth of charters, virtual models, and inner-district choice programs. 2 2 Ray Pennings, David Sikkink, and Ashley Berner, Cardus Education Survey 2014: Private Schools for the Public Good, Cardus, 2014, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/cardus-education-survey-2014-private-schoolsfor-the-public-good/. The result at this particular juncture, however, as Lindsey Burke, Director for Educational Policy at the Heritage Foundation, asserts, “is a confusing and unjust system where middle to high income families have a broader range of choices both within and outside of the public system.” 3 3 Lindsey M. Burke, Universal School Choice is Needed – Your Address Shouldn’t Limit Your Child’s Future (The Heritage Foundation, September 2019) https://www.heritage.org/education/commentary/universal-school-choice-neededyour-address-shouldnt-limit-your-childs-future. For many families, especially those on the lower end of the income spectrum, choices are still very much constrained by their zip code.

There are also a growing number of options outside of the public system. Religiously and pedagogically defined schools, homeschools, technologically propelled models of education that look very different from traditional schools—these reflect the growing panoply of educational delivery types that are educating America’s young today. Also, the existence of school systems (plural) is controversial too. For the better part of a century, the focus has been on centralized, consolidated public institutions and, as Yuval Levin points out in The Fractured Republic, these technocratic “onesize-fits-all solutions . . . are all very poorly suited to our diffuse and decentralizing society, and they are all in varying states of dysfunction.” 4 4 Yuval Levin, The Fractured Republic: Renewing America’s Social Contract in the Age of Individualism (New York: Basic Books, 2016), 84 Levin points out how this results in a decline of trust in our institutions as well as a “detachment from some core sources of social order and meaning.”

This introductory essay to the release of the third round of graduate outcome data that Cardus has collected over the past decade makes a simple argument: Perhaps it is time to rethink our categories. Maybe the term “public education” should no longer be shorthand for a single centralized system of education. After all, teaching and learning takes place in classrooms, not systems. And, as we will argue in what follows, the common-good outcomes that are essential to maintaining our democratic vibrancy are being produced by schools of varying types. Add to this the fact that in our growing pluralistic society we are increasingly becoming aware that formative institutions (which we desire schools to be) function best when there is a “thick” community of coherent culture and practice.

Perhaps the modern expression of “the common school” is in fact far more decentralized and diverse than what our familiar categories would suggest.

This proposition of educational pluralism for the sake of the common good is admittedly a reframing of the traditional debate about school choice. This can however be a uniting rather than dividing proposition. The foundation of the debate has historically been parental rights. The right and responsibility of parents to educate their children is foundational to Western civilization. The UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights boldly affirms that “parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.” 5 5 United Nations, Universal Declaration of Human Rights, December 10, 1948, article 26.3, https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/. The 2018 European Union report on the modernization of education in the EU affirms that “the right to education includes the freedom to set up educational establishments, on a basis of due respect for democratic principles and for the right of parents to ensure that their children are educated and taught according to their religious, philosophical and pedagogical convictions.” 6 6 “On Modernisation of Education in the EU,” European Parliament, May 17, 2018, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2018-0173_EN.html?redirect. The historical principle of schools carrying out their responsibility in loco parentis remains foundational.

More recent arguments have tended to involve “choice” language. There is significant debate about the value of competition, whether markets should be allowed to drive educational innovation and efficiency, and the balance between regulating inputs and measuring outputs in the educational enterprise. Concurrent with this debate has been the continued diversification of society and the onthe-ground choices of some to seek (and where they didn’t exist, create) educational options having features that the centralized educational model does not provide.

It is valuable to reflect on American education in a global context. Ashley Berner, a Cardus Senior Fellow and the Deputy Director of the Johns Hopkins University Institute for Education Policy, has highlighted how educational pluralism is the democratic norm around the world: “The list of educational plural systems is long, and includes the United Kingdom, Hong Kong, Belgium, Denmark, Indonesia, Israel, Sweden, and France.” 7 7 Ashley Rogers Berner, The Case For Educational Pluralism in the U.S. (John Hopkins University, 2019, executive summary), https://media4.manhattan-institute.org/sites/default/files/R-0719-ARB.pdf. In the Netherlands, for example, schooling has come to be seen as primarily a function of civil society rather than of the state; educational pluralism is the unchallenged norm. As it turns out, the American educational system is an outlier among diverse democracies, most of which offer some combination of public financing to schools that are not operated by the state. Educational pluralism, Berner argues, is a system of education “in which the government funds and regulates, but does not necessarily provide, public education.” 8 8 Berner, 2019, executive summary. Educational pluralism seeks to balance the needs of parents and communities with those of the state, to provide a more principled, diverse, and just educational system.

Alongside these educational debates there is a growing concern over how to chart a common path forward in the face of America’s distinct and particular communities, often holding deep and religious convictions. How does the American creed of liberty, justice, and equality play out in modern-day, diverse America? Motivated by this question, the Cardus Education Survey (CES) has sought to understand the intellectual, social, cultural, and spiritual outcomes of graduates who attended non-government schools and the ways in which different school sectors influence the choices and perceptions of these graduates in their young-adulthood years. The CES is designed to gauge whether these independent-school sectors, with their particular cultures, values, and practices, are ultimately contributing to the common good or detracting from it. After three iterations over nearly ten years (2011, 2014, 2018), the CES is considered one of the most comprehensive and representative surveys of independent-school-sector outcomes in the United States. Based on this data, we can now say with confidence that while distinct patterns of thought and behaviour emerge according to which schools these young adults attended, the public-good contributions of these school sectors (Protestant, Catholic, non-religious, and homeschool), when broadly viewed, are overwhelmingly positive.

In suggesting a reconceptualization of “public education,” we argue that “public” more appropriately refers to outcomes than to inputs and delivery mechanism. In this important sense, non-government schools are part of the “public system.” The key debate now is not whether these schools contribute to the common good but rather how important they have become to the common good and the workings of a modern and diverse democracy.

The following report marks nearly ten years of Cardus research into graduate outcomes in the United States. The report situates these findings, with emphasis on those from the most recent 2018 survey, at our particular moment in the United States. A modern, principled, and sustainable educational system is also a diverse one. Such a system values the full dignity of those within an increasingly diverse society, including their most deeply held convictions, and leverages these convictions for a vision of citizenship and the common good. Moreover, such a system of deep educational pluralism is necessary for child flourishing because it allows school communities to offer a particular and coherent culture of meaning and practice, thereby forming students to live respectfully within the school community and then beyond.

Pluralism, Flourishing, and the Common Good

The historical argument for the common school was based on the argument that one centralized school system would be most effective for forming a shared sense of citizenship and the common good. We argue that while government-run schools remain important and essential to the common good, we provide ample evidence that an exclusive or monopoly education-delivery model is not required.

Indeed, we argue that as society moves toward greater atomization and loneliness, the perennial quest for belonging, meaning, and purpose grows. Moreover, as society becomes more deeply plural, a coherent school culture becomes all the more important to effective education, to healthy participation in a democratic society, and to understanding what unites us.

School culture, the conditions for its success or failure, and the importance of strong leadership in motivating change are at the heart of a number of promising research initiatives today. 9 9 Charles Glenn (2002, 2004); James Davidson Hunter (2000), Ashley Berner (2019). Where can we find these school communities of trust and reciprocity? The ones that cultivate deep character and the capacity to contribute and sacrifice even at personal expense? What can we learn from these communities, and how do we leverage these habits and virtues for citizenship? The CES aims to go beyond the politics to understand the building blocks of society itself. What are the conditions for student flourishing? Where do students learn to respect and love one another and others? How can we scale these lessons to maximize their potential for democratic citizenship?

James Davison Hunter, Distinguished Professor of Religion, Culture, and Social Theory at the University of Virginia, studies the relationship between particular moral cultures (defined broadly to include the following: expressivists, theists, utilitarians, humanists, and conventionalists) and character formation. “Morality is always situated,” Hunter explains, “historically situated in the narrative flow of collective memory and aspiration, socially situated within distinct communities, and culturally situated within particular structures of moral reasoning and practice.”

10

10

James Davison Hunter, The Death of Character: Moral Education in an Age without Good or Evil (New York: Basic

Books, 2000), 11.

The particular manifestations of moral culture mean that each community will embody different social expectations and place different demands on the individuals living within it. Importantly, character is formed in relation to the convictions of these particular moral cultures and “is manifested in the capacity to abide by those convictions even in, especially in, the face of temptation.”

11

11

Hunter, Death of Character, xiii.

Based on an empirical study of the moral cultures of over five thousand children from over two hundred schools across the country, a significant finding from Hunter’s research is that while social scientists typically favour a range of background factors, such as race, class, and gender, to account for differences, “children’s underlying attachments to a moral culture were the single most important factor in explaining the variation in their moral judgments.” 12 12 Hunter, Death of Character, 163 Moral cultures “provide the reasons, restraints, and incentives for conducting life in one way rather than another” and act very much like moral compasses in providing the bearings to navigate the complex moral terrain of life. 13 13 Hunter, Death of Character, 22

Anne Snyder’s work, The Fabric of Character, affirms the value of particular cultures of meaning and practice for character formation and the “shared pursuit of the good.”

14

14

Anne Snyder, The Fabric of Character: A Wise Giver’s Guide to Supporting Social and Moral Renewal (Washington, DC:

The Philanthropy Roundtable, 2019).

Snyder offers sixteen crucial features that truly formative institutions tend to possess, which include a particular identity, a clear and strong reason for being in the world, a covenant or creed that is affirmed regularly, and communal rhythms, routines, and rituals. Charles Glenn, Professor Emeritus of Educational Leadership at Boston University, refers to these as “thick communities” and describes their importance for forming moral habits, virtues, and “the settled disposition to act in accordance with the common good rather than with selfish interests at critical junctures.”

15

15

Charles Glenn, “Democratic Pluralism in Education” Journal of Markets and Morality 21.1 (Spring 2018), p. 132.

Glenn adds further that “thick communities” are not places where “differences peacefully coexist” but rather where “people work together toward some serious end.”

16

16

Glenn, Democratic Pluralism in Education, 134.

Paradoxically, we learn from the work of Glenn, Hunter, Snyder, and others that pluralism may in fact engender the need for particularity at the local level; schools with particular and coherent cultures of meaning and practice, capable of cultivating moral character and civic virtue, play an increasingly important role in the fractured America of today. In other words, might the very imperative of civic good and social flourishing for all, which in a previous era led to arguments for a common system of education delivery, now lead us to consider a system that provides diverse options, reflecting the diversity of the culture in which we now find ourselves?

The Cardus Education Survey

he Cardus Education Survey has become recognized as one of the most comprehensive and valuable surveys of its kind among schools practitioners, leaders, and policy-makers alike. These surveys, conducted in 2011, 2014, and 2018, contribute to an understanding of school-sector influence on a number of academic, spiritual, cultural, civic, and relational outcomes. More broadly, the CES seeks to understand the life patterns, views, and choices of graduates from various kinds of non-government schools in order to assess their contributions to a shared good. The CES collects responses from a nationally representative sample of over 1,500 high-school graduates between the ages of twenty-three and forty from government schools and non-government schools, including non-religious independent schools, Catholic and Protestant schools, and homeschoolers, in both Canada and the United States. 17 17 Detailed reports of survey outcomes, organized by various themes, as well as a summary of the survey’s methodology can be found on the Cardus website, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/. While the survey design heavily oversampled graduates of independent schools, only a very small number of respondents attended Jewish and Islamic high schools, which constitute increasingly important and growing sectors. Graduate responses from these schools were not included in the analysis due to the small sample sizes available. Though the charter-school movement is growing rapidly, it was in its infancy when graduates were in high school. The sample size of these graduates is also insufficient for separate analysis. 18 18 The 2018 CES respondents include 904 graduates who primarily attended public high schools, 83 respondents who primarily attended non-religious private schools, 303 graduates of a Catholic high school, 136 graduates of an evangelical Protestant school, and 124 who were homeschooled. In order to isolate the school effect for each of these sectors, the analysis includes a large number of control variables for basic demographics (gender, race and ethnicity, age and region of residence), family structure (not living with each biological parent for at least sixteen years, parents divorced or separated, not growing up with two biological parents), parent variables (educational level of mother and father figure, whether parents pushed the respondent academically, the extent to which the respondent felt close to each parent figure), and the religious tradition of parents when the respondent was growing up (mother or father was Catholic, conservative Protestant, conservative or traditional Catholic). A control was also included for the number of years a private school graduate spent in public school. Despite our efforts to construct a plausible control group, because families who send their children to religious schools or non-religious independent schools make a choice, they may differ from those who do not exercise school choice in unobservable ways that are therefore not accounted for in our study. Despite this, the CES use of an extensive survey instrument, together with its comprehensive application of control variables and resulting patterns of outcomes, assures us with a 90 percentile confidence interval for each coefficient of the accuracy of our school sectoral outcomes.

By virtue of their “non-public” status, independent schools often have well-defined reasons for existing and “thick” school communities. While we’re hesitant to draw strong conclusions about culture at a sectoral level, nearly ten years of CES data paints a fairly consistent picture of the most common patterns and choices of graduates from each high-school sector. 19 19 The following 2018 CES reports, with a more detailed summary of outcomes, are available on the Cardus website: “From the Classroom to the Workplace,” August 19, 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/cardus-education-survey-2018-from-the-classroom-to-the-workplace/; “Involved and Engaged,” August 23, 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/cardus-education-survey-2018-involved-and-engaged/, “Spiritual Strength, Faithful Formation,” August 29, 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/2018-us-cardus-education-survey-spiritual-strength-faithful-formation/; “The Ties that Bind,” September 4, 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/2018-us-cardus-education-survey-the-ties-that-bind/; and “Perceptions of High School and Preparedness for Life,” September 19, 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/cardus-education-survey-2018-perceptions-of-high-school-experience-and-Preparedness-for-life/. In this way, while recognizing that these sectors likely include large variation at the school level, we are able to draw a number of high-level conclusions about the broad cultures of various independent-school sectors, the choices and perceptions of graduates in their young-adult years, and how these ways of living might have implications for life together and the common good.

The CES uses public-school-graduate outcomes as a baseline from which to compare other sectoral responses. The discussion that follows often describes particular measures as being “higher” or “lower,” and the reader should keep in mind that this is always in reference to average public-school-sector outcomes. Thus our analysis highlights the key outcomes of particular independent-school sectors but underemphasizes, perhaps, those of government-run schools. The five 2018 CES thematic reports capture both the raw school-sector averages (including family), and the school-sector influence that accounts for family controls. For the particular argument we are making here, however, we highlight raw sectoral averages, recognizing that a key feature of a “formative” school culture is coherence between family and school. We include a number of charts to illustrate these key themes and relationships.

The Journey and Mindset of the Protestant School Graduate

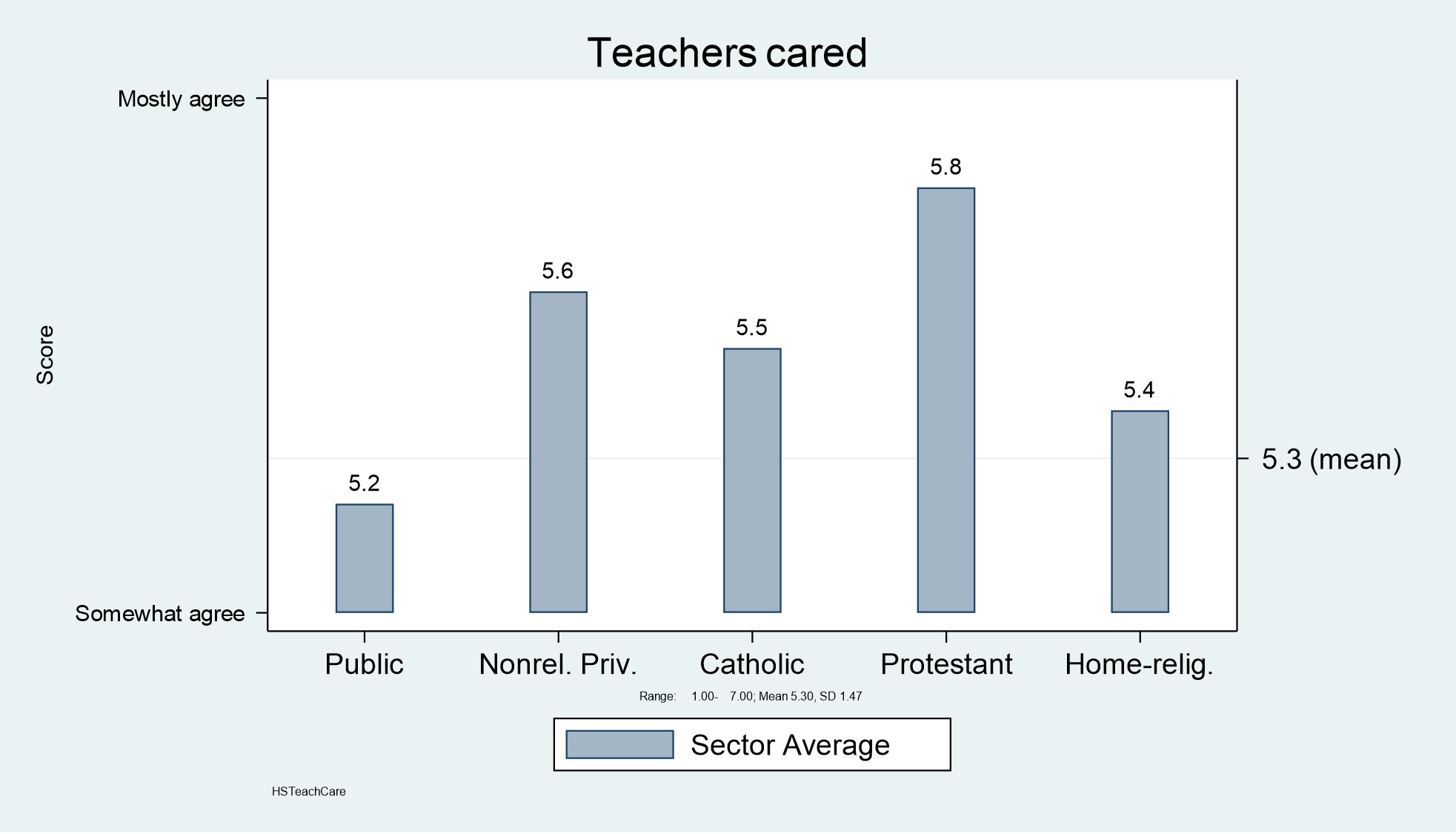

Protestant school graduates were much more likely than their public-school cohorts to look back favorably on their high school years. Indeed, forty percent of Protestant school graduates “completely agree” that their teachers cared, as compared to only fifteen percent of public-school graduates. Relationships with administrators and with other students were also much higher among Protestant graduates, who were in strongest agreement with the sentiment that “their high school was closeknit.” Indeed, by far the strongest divide in responses is found between public-school graduates and non-government school graduates when asked whether they felt that their high school prepared them well for relationships in life. Interestingly, Protestant-school graduates are also slightly higher than public-school graduates in their assessment of how well they were prepared for interaction with the dominant American culture and society.

They have among the highest number of close ties that they can confide in, and these close-tie relationships extend to their family life. A number of measures point to these graduates being very family oriented and holding the most traditional views on marriage. Indeed, a 2017 Cardus report concludes that Protestant-school graduates are most likely to stay married. 20 20 David Sikkink and Sara Skiles, Making the Transition: The Effect of School Sector on Extended Adolescence (Cardus, 2018), https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/making-the-transition-the-effect-of-school-sector-on-extended-adolescence/ There is no question that in terms of relationships, Protestant-school graduates experience a more nurturing environment during their high-school years than most, that these graduates recognize the value of this environment, and that they go on to have strong, healthy relationships in their young-adult years.

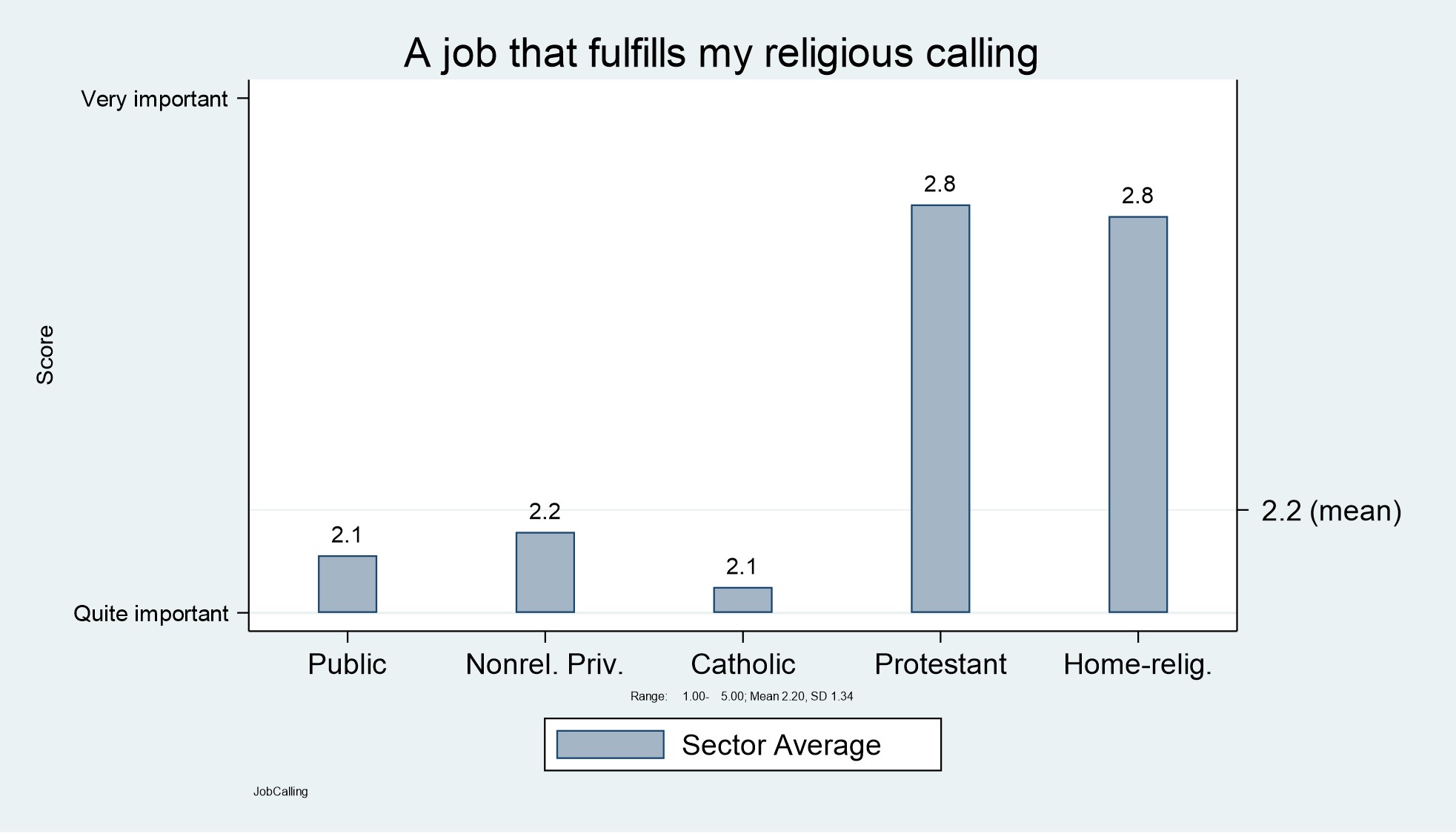

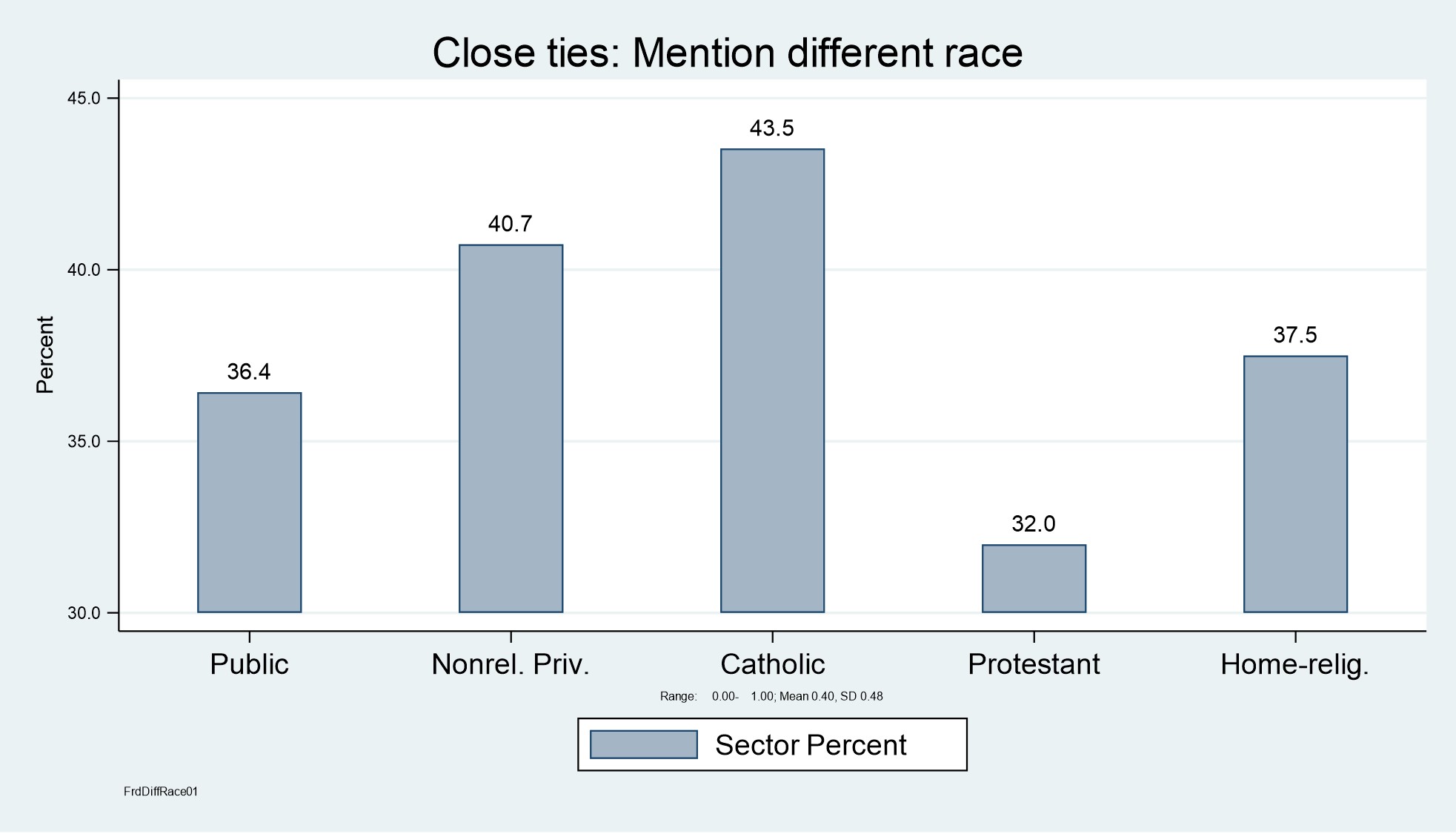

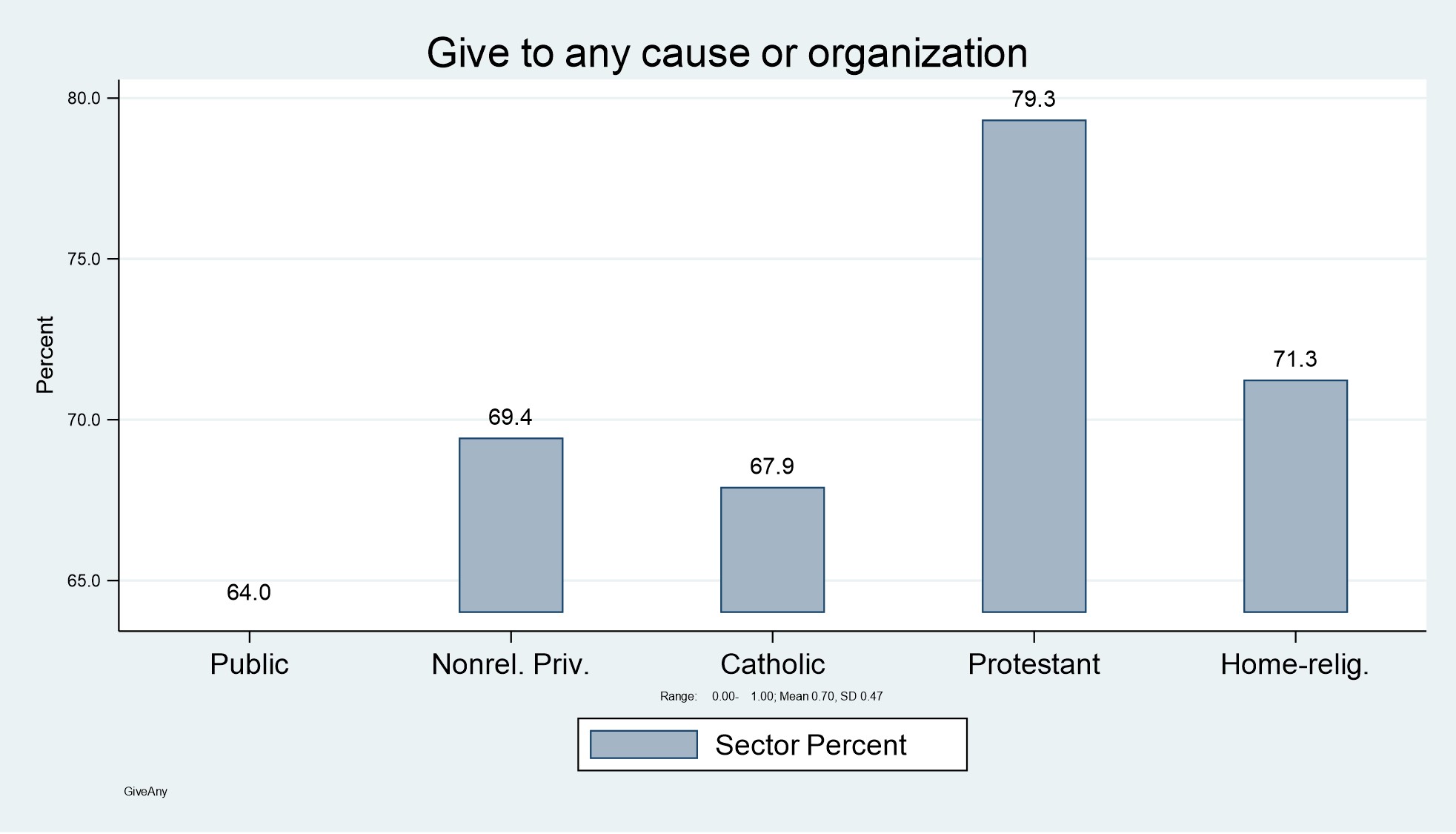

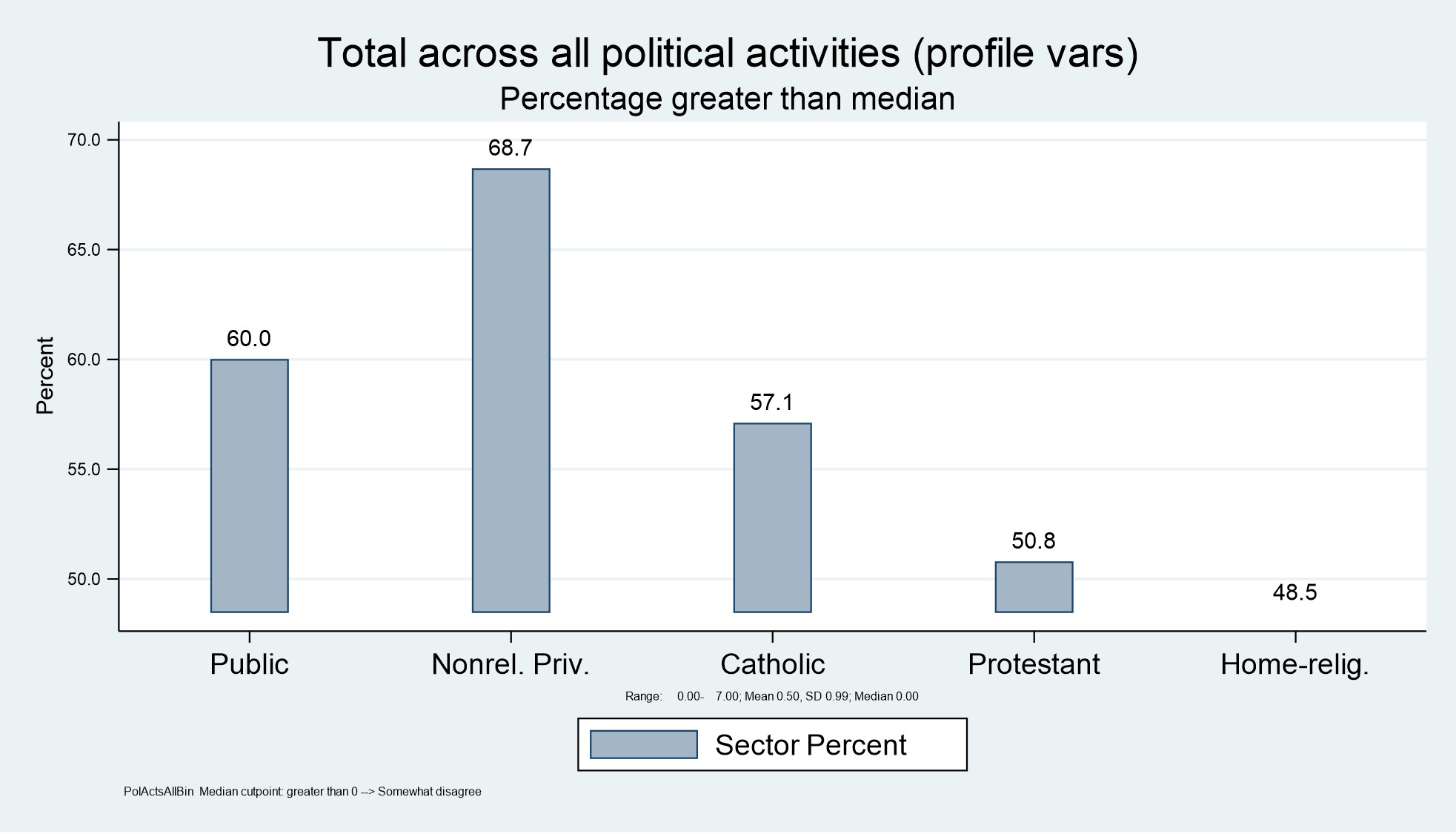

Interestingly, despite having among the lowest levels of trust in public officials and the media, these graduates remain as engaged civically as, if not more than, the average public-school graduate. They are also most likely to “give to any cause or organization” and least likely to feel that they are “more a citizen of the world than a country.” In addition, on several measures, Protestant-school graduates express a greater sense of obligation. For example, Protestant-school graduates express a high sense of obligation to participate in politics and also have a stronger sense of obligation to take action against wrongs or injustice in life than does the average public-school graduate. The Protestant-school sector is also effective in cultivating in its graduates a strong sense of obligation to help the poor in other countries. However, these graduates are also among the least politically engaged and least likely to know public officials. They are also among the least likely to have a close relationship with someone of a different race, though it is important to remember that many Protestants likely attended schools in rural areas when growing up and that this likely has a bearing on this measure. Protestant-school graduates seem to be very family oriented and express a strong desire for a job that fulfills their vocational calling. These graduates are much more likely to be employed in the health-care industry—in fact, about 1.8 times more likely than are public-school graduates. In terms of employment level, Protestant-school graduates are less likely to have a managerial or executive position than a public-school graduate. Despite this, however, Protestant-school graduates are no different from public-school graduates in reported household income.

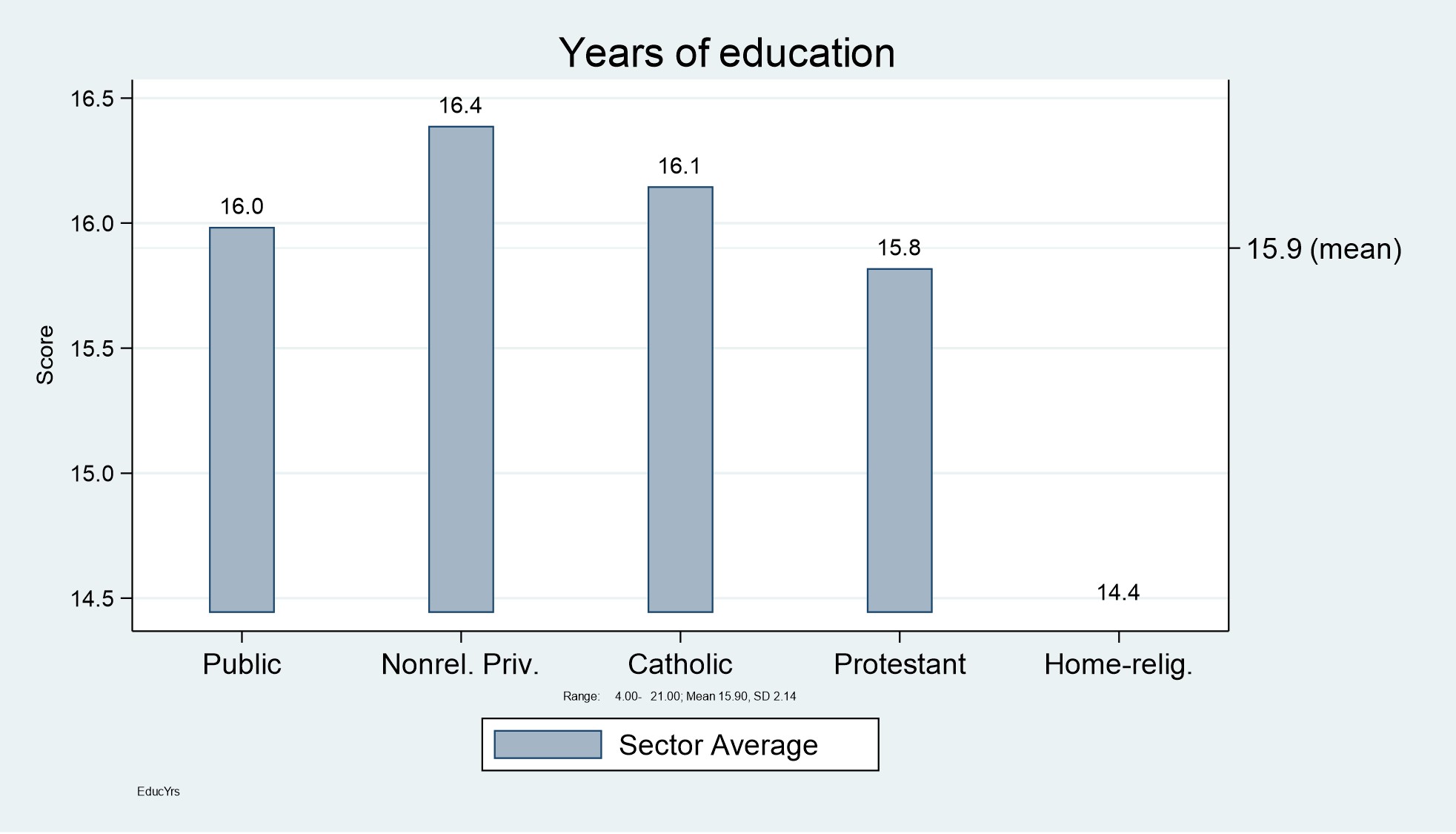

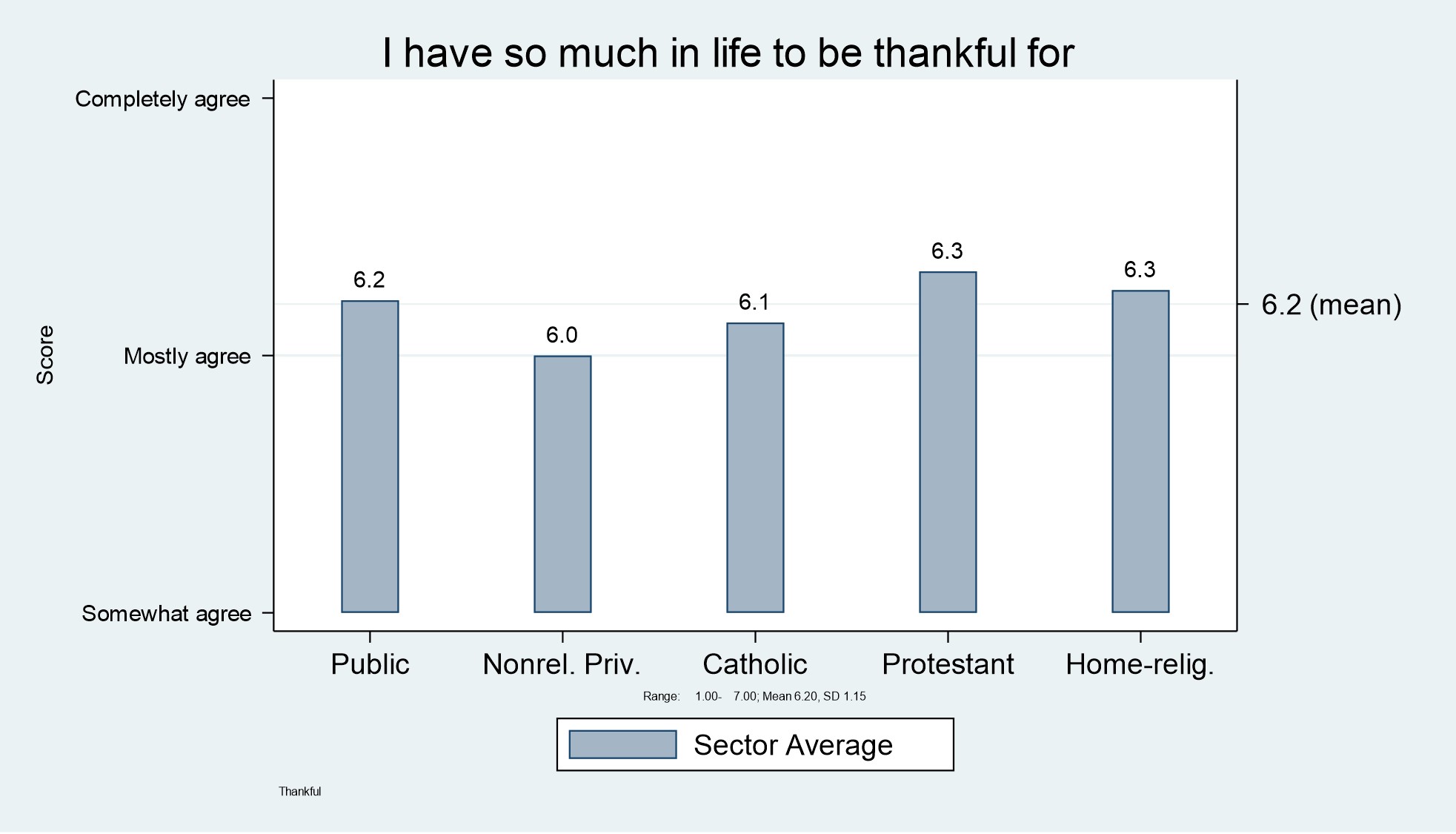

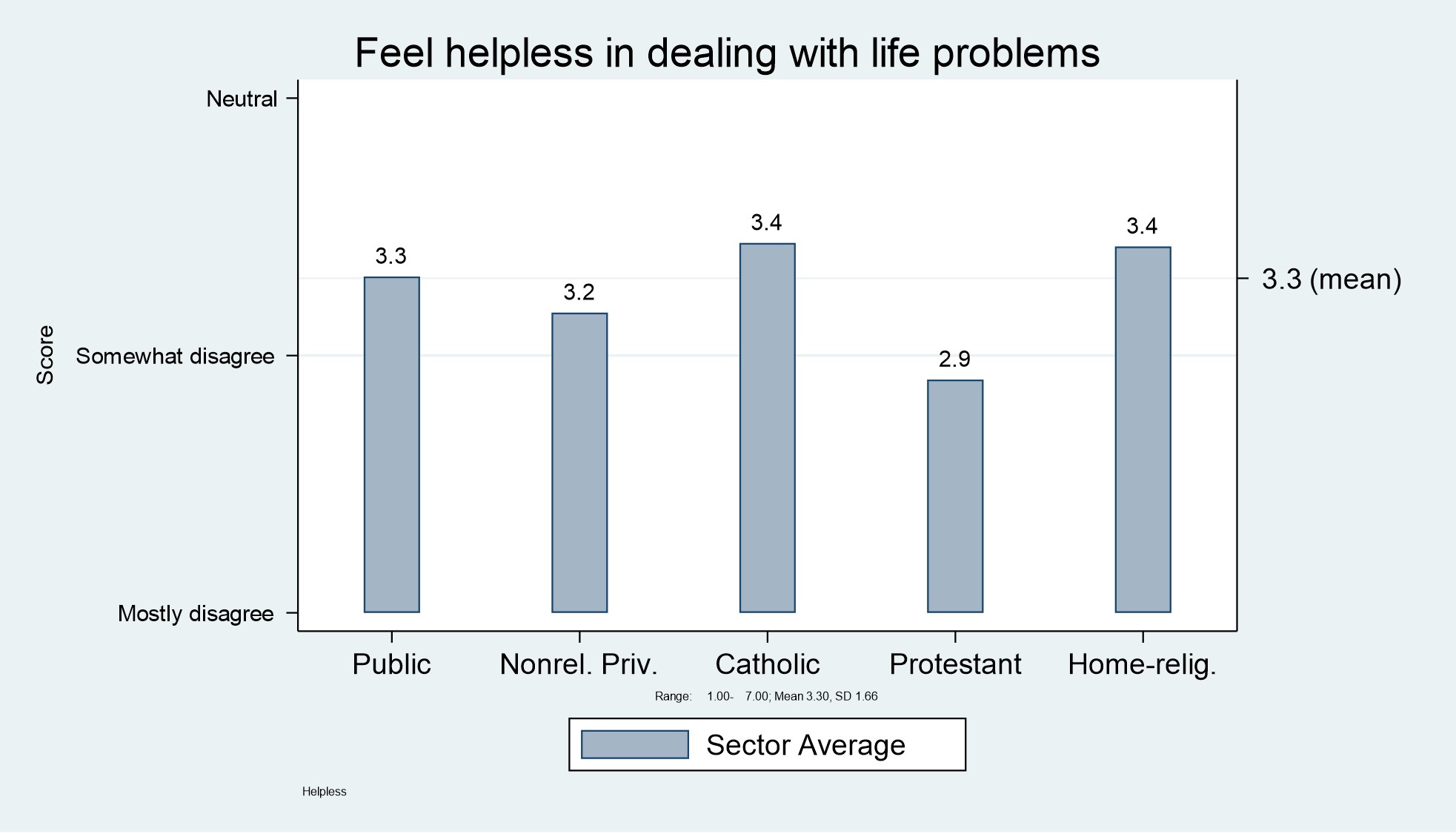

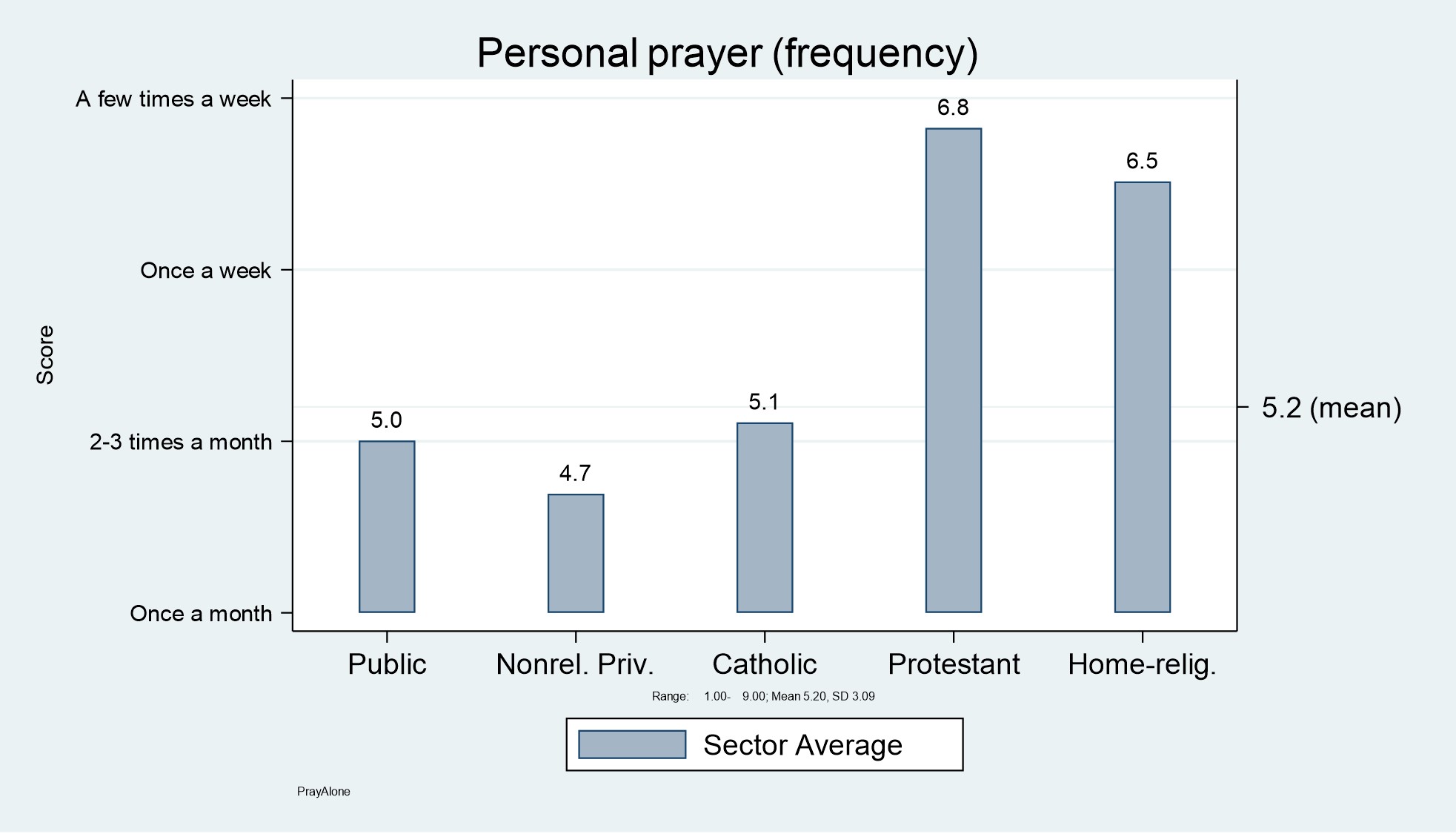

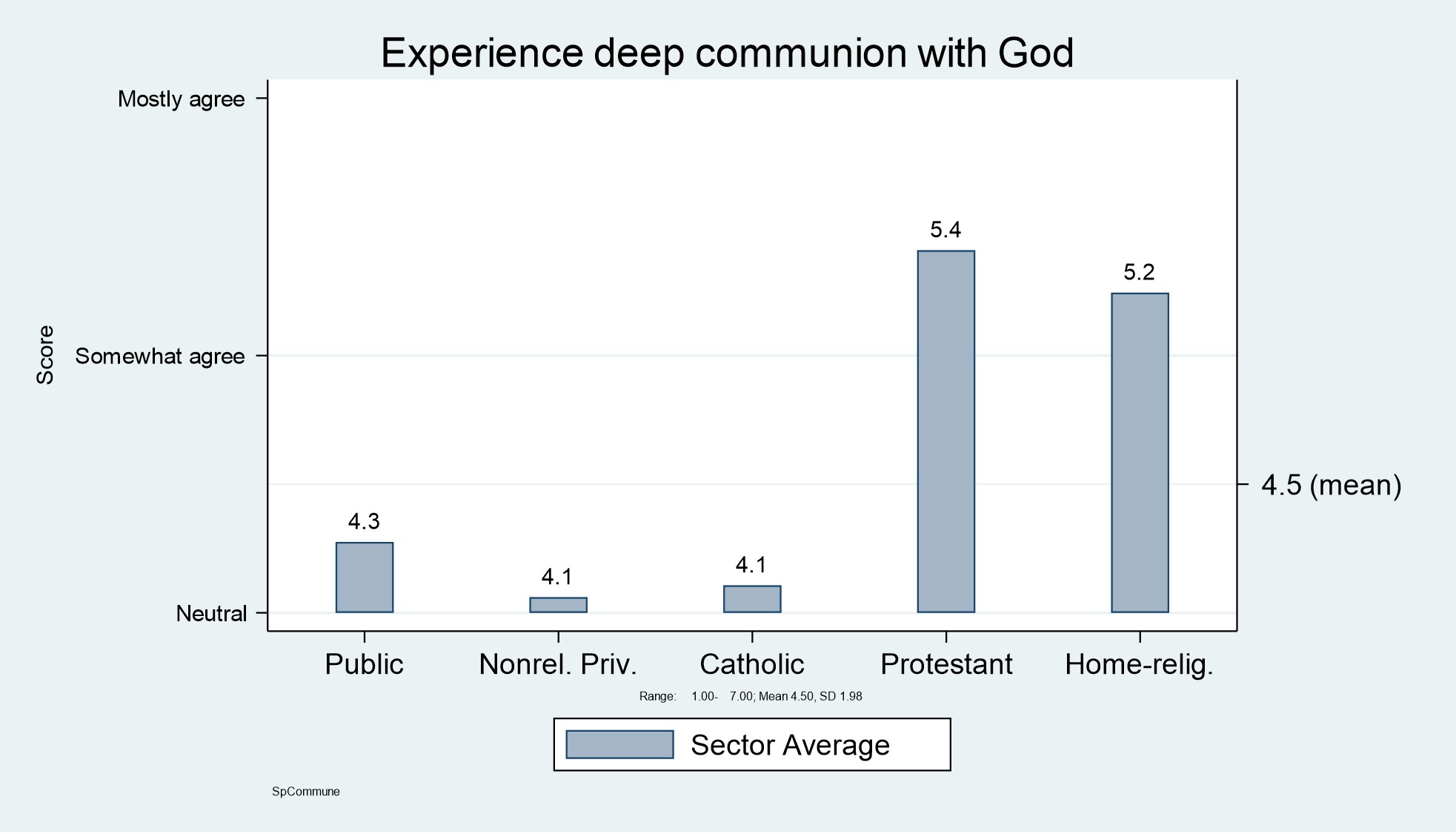

Protestant-school graduates seem to balance personal motivations with family and communal obligations. While they tend to be slightly lower than public-school graduates in educational attainment and employment status, they express the highest levels of gratitude and sense of purpose and are least likely to feel they are lacking direction in life. Thirty-seven percent of public-school graduates, compared to 48 percent of Protestant-school graduates, completely or mostly disagree that they feel helpless in dealing with life’s problems. Fifty-four percent of Protestant-school graduates and 43 percent of public-school graduates mostly or completely disagree that they lack clear goals or direction in life. Sixty-three percent of Protestant-school graduates completely agree that they have much to be thankful for, while 54 percent of public-school graduates completely agree with this view. Interestingly, Protestant graduates also seem to watch the least amount of TV. Protestant-school culture at a sectoral level seems to be one of meaning and relationships. These graduates are embedded in cultures that give meaningful shape to their lives and help mitigate the competitive pressures and lack of purpose that others in society may feel. These graduates also tend to have traditional and family-oriented worldviews and are most likely to experience a deep communion with God. These outcomes seem in keeping with what parents who send their children to Protestant schools say that they want. A Cardus study, “What Religious School Parents Want,” carried out in conjunction with the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, finds that religious-school parents care most about moral formation and student behaviour and place less emphasis on life skills and vocational training. 21 21 David Sikkink, “What Religious School Parents Want,” Cardus, January 13, 2014, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/what-religious-school-parents-want/. These parents tend to put less emphasis than the average parent on “developing students who pursue their individual interest and talents.”

The Journey and Mindset of the Catholic-School Graduate

The average Catholic-school graduate is distinct from both the Protestant-school graduate and the public-school graduate in a number of important ways. All independent-school graduates are more likely to view their high-school experience and culture as positive than does the public- school graduate, and Catholic responses are among the most positive here. These graduates are more likely to report that their high school was close-knit, and that there were very positive relationships with administrators. These graduates were slightly less likely to report that their teachers cared and that students got along than non-religious private school and Protestant-school graduates, but these assessments were still much higher than those of public-school graduates. Catholic-school graduates felt among the best prepared for university and relationships, just behind the non-religious independent-school graduates, who tended to feel most prepared in these areas.

Catholic-school graduates move within diverse circles. Interestingly, Catholic-school graduates are more likely—1.5 times more likely, in fact—to have close ties with an atheist than public-school graduates. Our findings reveal that Catholic-school graduates are also more likely to have a greater proportion of friends of a different race and ethnicity. On average, these graduates report having the highest number of close friends and more interactions weekly with these friends. These graduates are also most likely to consider a parent, a co-worker, or someone who is gay or lesbian as a close friend.

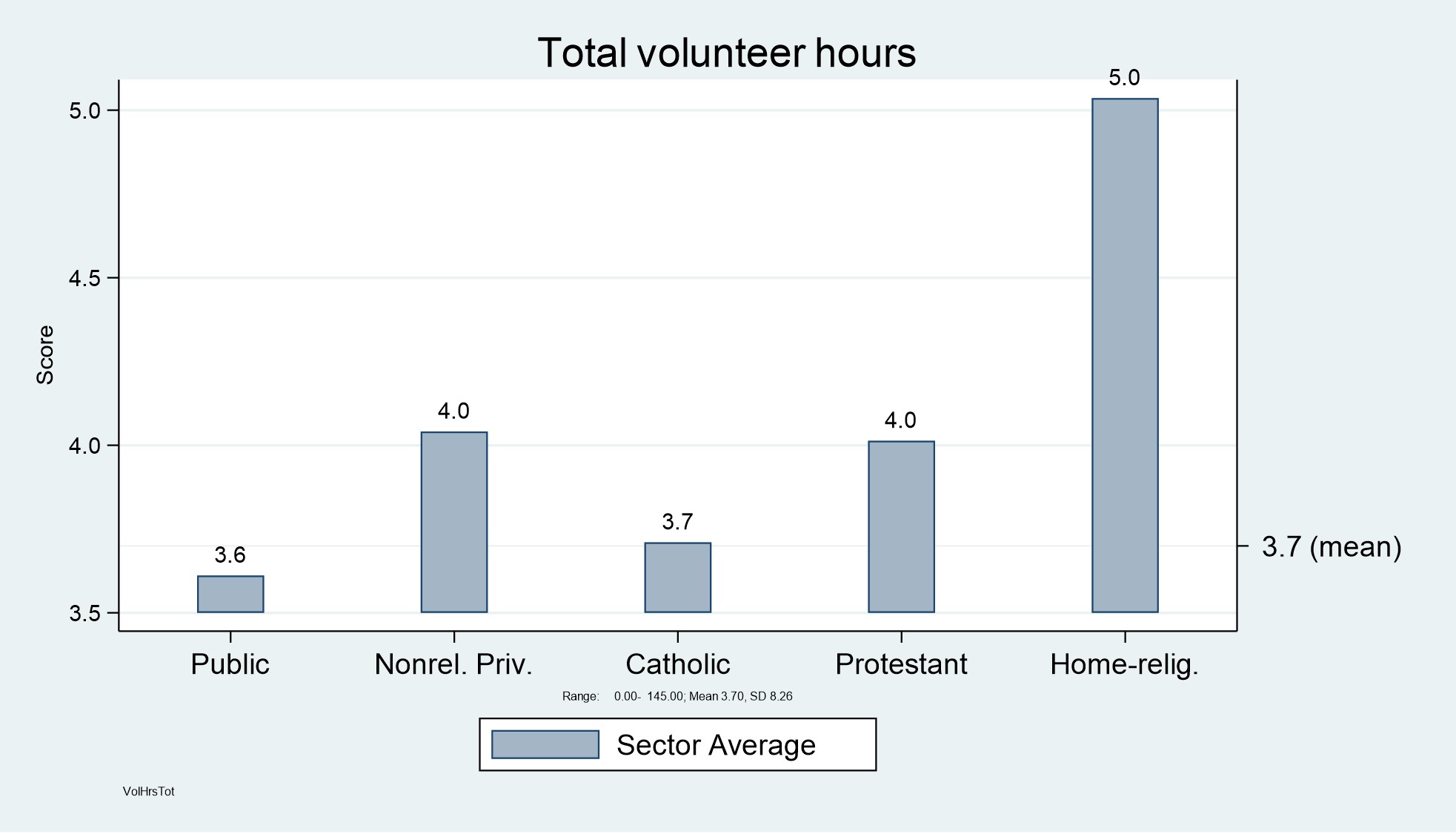

Catholic-school graduates report a higher incidence of volunteering outside the congregation and donating to charity, including to secular and political causes. These graduates tend to be involved in a wide variety and number of volunteer causes and organizations, including health care, poverty, and the elderly and youth. In addition, Catholic-school graduates are somewhat more likely to participate in mission and social-service trips than are public-school graduates and much more likely—indeed, four times more likely—to be registered to vote.

The Catholic-school sector clearly cultivates a culture of academic excellence. Strong academic outcomes are evident across a number of measures. Graduates on average have attained more education than public-school graduates by about .3 years, though this difference is only marginally significant. These graduates are also about 33 percent less likely to be unemployed than are public school graduates and about 1.5 times more likely to be in a professional or scientific occupation. In fact, Catholic-school graduates are about 40 percent less likely than public-school graduates to be in entry-level positions, and they are also more likely to know an elected public official or a corporate executive.

Catholic-school graduates are not distinct, however, from public-school graduates on a number of measures. These graduates express similar levels of trust in the federal government and only slightly lower levels of trust in the mass media. These graduates also express similar levels of agreement with the statement that they feel more like a citizen of the world than of a country.

Interestingly, Catholic-school graduates are also in line with public school graduates on their views of religion and spirituality. Here, our survey asks a number of questions such as whether graduates feel a deep communion with God, whether they feel an obligation to regularly practice spiritual disciplines, and how often they read the Bible. In the 2018 data, the Catholic-school sector seems to have a much smaller impact on the religion and spirituality of its graduates than does the Protestant-school sector, but differences from public-school graduates appear to be more positive and consistent than we have seen for past cohorts. Interestingly, while almost 20 percent of US Catholic school students are not Catholic, the Catholic-school sector seems to influence the formation of its students towards a deeper spirituality on a number of measures than family-background averages would suggest.

The Catholic-school sector is doing a particularly good job of offering a lower-cost independent school model and excellent quality of education for a diverse population. A recent National Catholic Education Association (NCEA) report reports, for example, that “a child who is black or Latino is 42% more likely to graduate from high-school and 2.5 times more likely to graduate from college if he or she attends a Catholic school.” 22 22 National Catholic Educational Association - Catholic School Fact Sheet, ttps://www.ncea.org. The high academic outcomes of the Catholic-school sector are widely acknowledged, as is its distinctive emphasis on self-discipline, as captured in a 2018 Thomas B. Fordham Institute report “Self-Discipline and Catholic Schools.”

The Journey and Mindset of the Non-Religious Independent-School Graduate

The non-religious independent-school sector is distinctive in a number of important ways. First, these graduates tend to hold the most-positive views of their high-school years, not only of the relationships during these years but also in terms of how well prepared they felt for the years that followed.

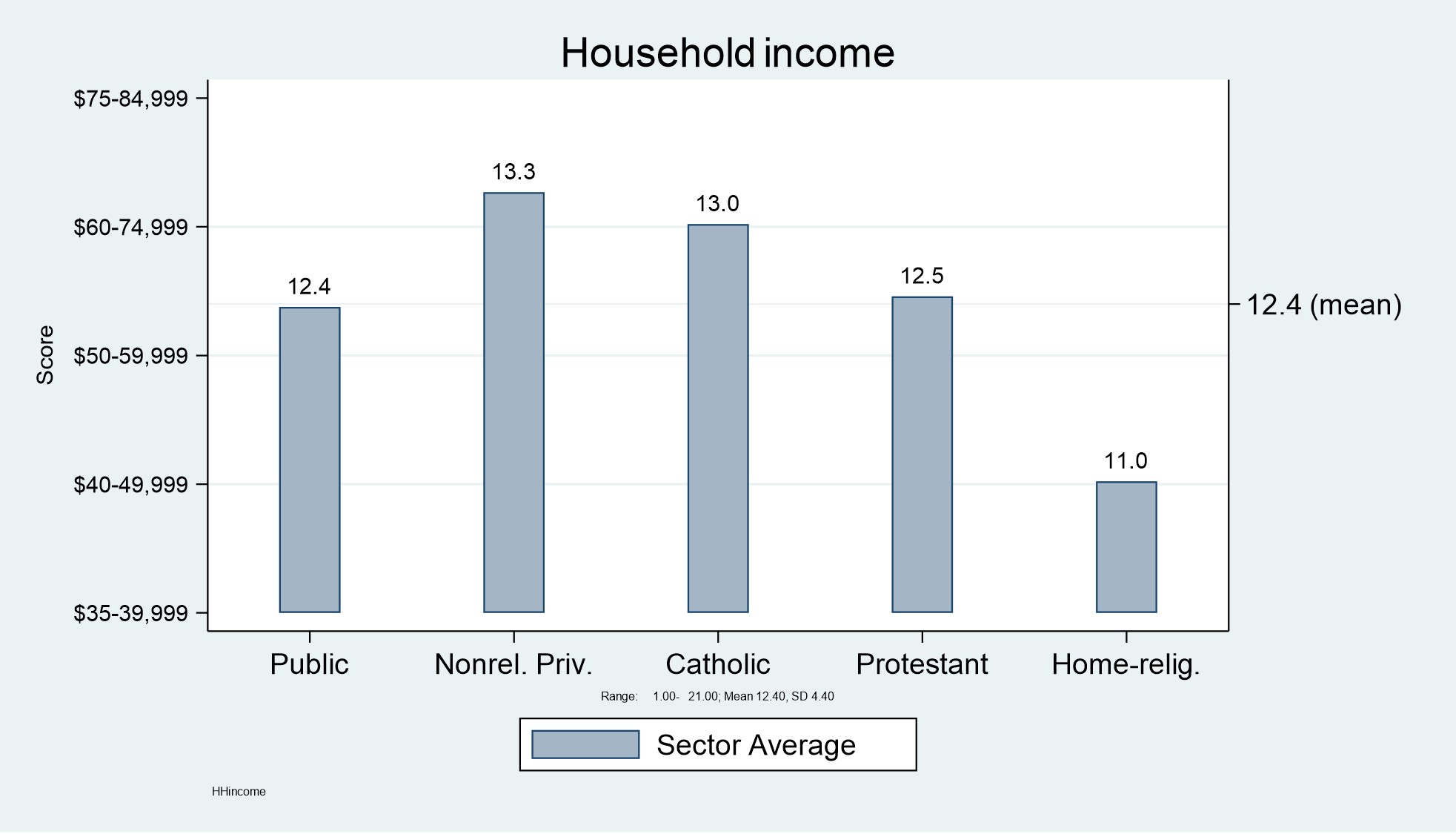

Non-religious independent-school graduates have a significant advantage in terms of educational attainment. These graduates have just over a half-year advantage in years of education when compared to public-school graduates. They are significantly more likely to attain a BA and significantly more likely to attain a post-baccalaureate degree. Non-religious private-school graduates are also much more likely to hold a position as a manager, supervisor of staff, director, or executive. In fact, they are twice as likely as public-school graduates to report this type of employment. As we would expect, household income is significantly higher for non-religious independent-school graduates relative to public-school graduates; indeed, these graduates report an average of about $20,000 more in household income.

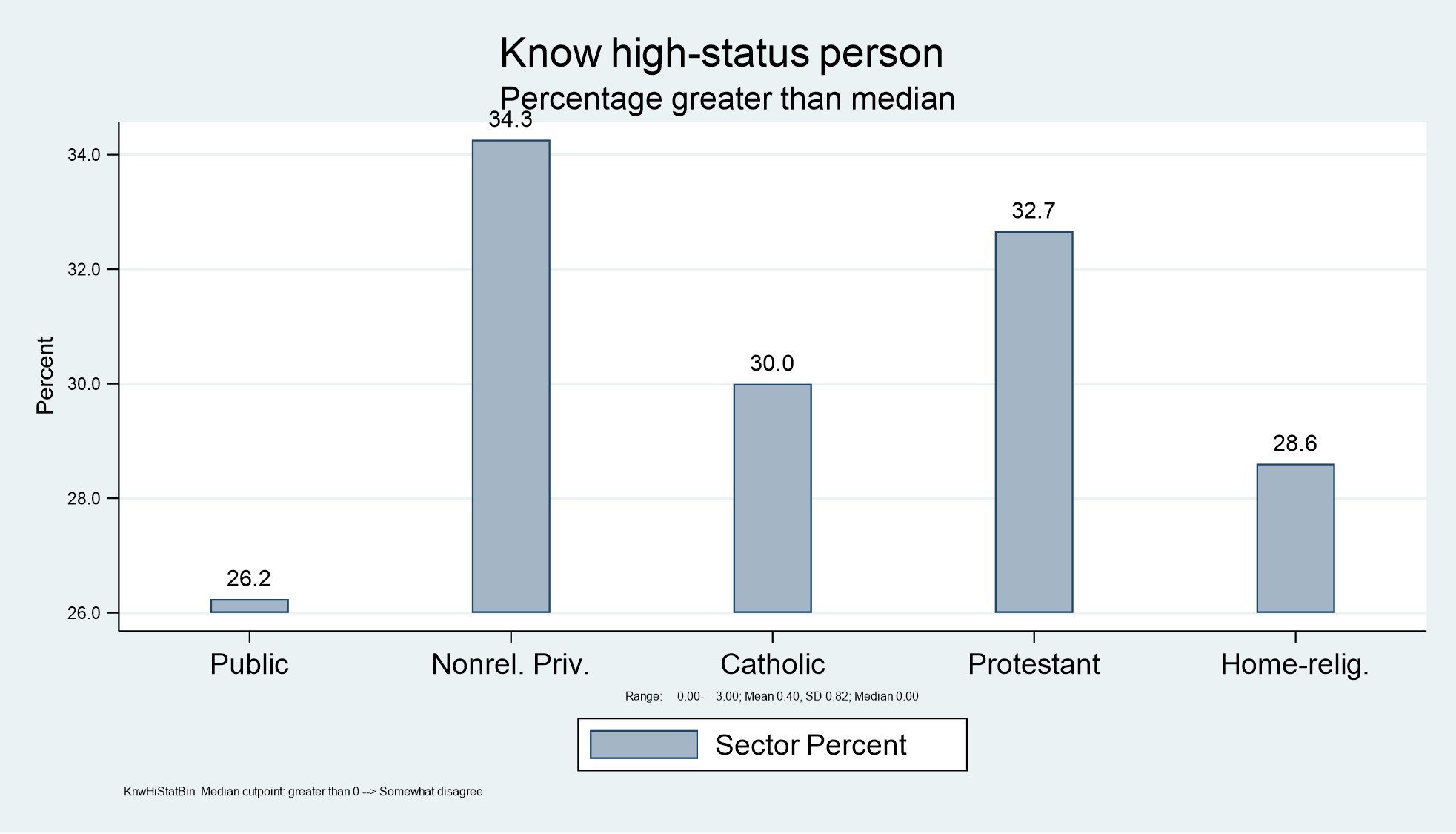

Interestingly, non-religious private-school graduates are much more likely—in fact, more than twice as likely—to know someone who is an elected public official than are public-school graduates. Non-religious independent-school graduates are also more likely to know a corporate executive and much more likely to say that they know a community leader. These graduates are clearly more-closely connected to those in positions of power than are public-school graduates. In raw percentage terms, 34 percent of non-religious private-school graduates report knowing a high-status person, while 26 percent of public-school graduates report the same.

Non-religious independent-school graduates are also the most politically engaged; indeed, they are over twice as likely to volunteer for a political cause or organization as is a public-school graduate. These graduates are also more likely than public-school graduates to donate to charity and to volunteer in the areas of health care, arts and culture, and political and international causes and organizations, often being the most engaged on these fronts. Finally, these graduates are also more likely to trust the federal government, scientists, and the mass media than are all other types of graduates and much more likely than public-school graduates to consider themselves as citizens of the world.

In terms of relationships, however, these graduates tend to report lower levels of close ties with family members or co-workers. They report having the lowest levels of relationships with people that they can confide in. They are also the least likely to talk about religion and least likely to express that their spirituality gives them a feeling of fulfillment. Surprisingly, these graduates report watching the highest amount of TV daily and express lower levels of feeling obligated to take action against a wrong or injustice and to help the poor in other countries than is the average public-school graduate. Perhaps most surprising of all, these graduates are the least likely of all graduates to agree with the statement that they have so much in life to be thankful for.

The average non-religious independent-school graduate enjoyed a privileged experience of highquality relationships and academic excellence while in high school, followed by further academic and career success. In their young-adult years, these graduates are the most-highly engaged, politically and civically, and most-closely connected to centres of power. But the picture is nuanced. These graduates’ responses also fall lower on a number of relationship measures and they are least likely to say that they feel grateful for their lives. The nonreligious independent-school sector is clearly cultivating accomplished and engaged young adults, but the low reported outcomes for measures having to do with close ties and a feeling of gratitude and purpose are somewhat surprising.

Religious-Homeschool Graduate Pathway

The religious-homeschool graduate pathway is similar to that of the Protestant-school graduate on a number of measures and similarly distinct from the public-school graduate. Religious-homeschool graduates complete significantly fewer years of education than do public-school graduates; indeed, they are on the lowest end of our graduate spectrum on this measure, completing on average just over one year less of schooling than public-school graduates. Religious-homeschool graduates are also about four times more likely to leave schooling entirely after graduating from high school. These graduates are more likely to be unemployed—in fact, over twice as likely to be unemployed as are publi-school graduates—and they report significantly lower household income as compared to the public-school graduate—in fact, about $10,000 lower.

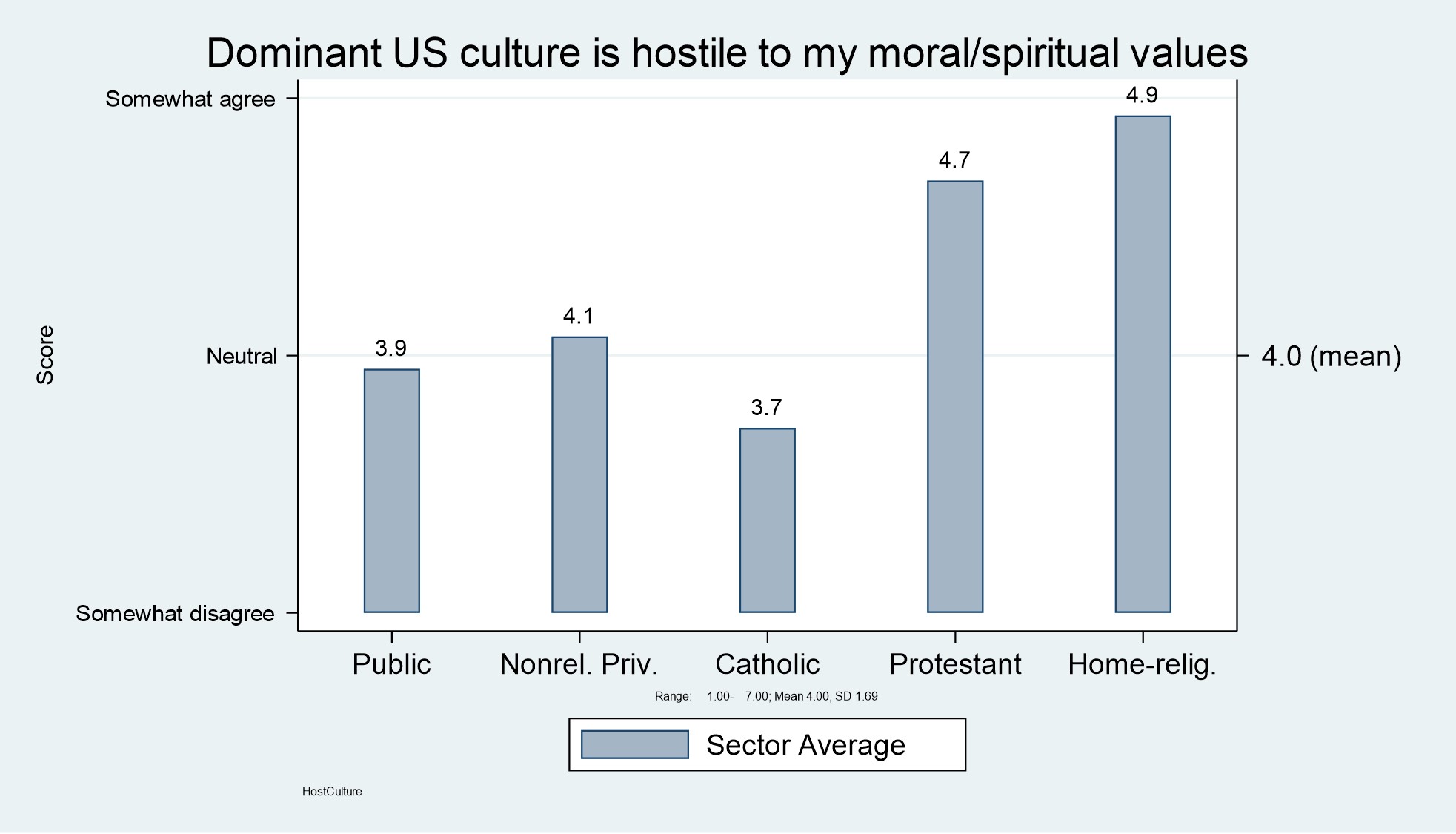

These graduates tend to trust the federal government, scientists, publicschool teachers or administrators, and the media the least of all graduates and were most in agreement with the view that the dominant US culture is hostile to their moral/ spiritual values. They are less likely to be registered to vote in national elections and significantly less likely to vote in local elections than are public school graduates. They are similar to public-school graduates, however, in terms of volunteering for political causes and with arts and cultural organizations.

In terms of their relationships, religious-homeschool graduates were much more likely—indeed 1.5 times more likely—to include an immediate family member as one of their four closest ties. These graduates tend to have close ties with people of similar religious beliefs and traditional worldviews, and they report having lower numbers of close-ties they can confide in. They are also the least likely to have close ties with a university degree, and less likely to know an elected official or a corporate executive. Interestingly, these graduates were most likely to report that they have so much in life to be thankful for and less likely than all graduates, except for Protestant school graduates, to think that life often lacks clear goals or a sense of direction.

The homeschooling sector is marked by a high degree of variation, making it difficult to discuss this as a “sector” in the same way. Home-schooling graduates seem to have a wide range of views and experiences, making it more difficult to draw a coherent picture of the typical pathway.

School Sector Outcomes, Culture, Character, and the Common Good

Taking a high-level view of outcomes, an analysis of three cohorts of non-government-school graduates over nearly ten years illustrates how broad school-sector cultures tend to cultivate particular pathways, lived norms, and choices that make important contributions to civil society.

Catholic-school cultures are most diverse and exceptional in fostering high academic outcomes and a culture of civic and political engagement. Homeschool graduates and Protestant-school graduates seem to be the least materially driven and most family oriented. The Protestant-school culture cultivates faith and relationships, a sense of obligation to others, and a culture of civic engagement. While it is difficult to draw many conclusions from the homeschooling sector, it is fair to say that this is a family-oriented culture that also seems highly innovative, civically engaged, and content. The non-religious independent-school culture undoubtedly fosters a culture of academic excellence, its graduates are the most politically engaged, and they have the highest income and educational levels, although they are also the least likely to agree that they have much to be grateful for.

The thick cultures of many of these independent schools cultivate graduates that contribute in different ways to the public square. By virtue of their non-publicly funded status, independent schools are clear and intentional about who they are, and they draw families that agree with their particular worldview and pedagogical approaches. For this reason, independent schools often offer thick communities, with strong and coherent cultures of both meaning and practice; school community members collectively understand and live out these norms of behaviour. Nearly ten years of Cardus Education Survey data make clear the fact that well-functioning independent schools form important middle and mediating layers of society. At their best, these formative school communities cultivate reciprocity and the ability of members to place the common interests of the community ahead of those of the individual. A modern, just, and principled pluralism will recognize the value and deeply held convictions of these particular educational communities and leverage their capacities for the greater common good.

Moving Forward with Educational Pluralism:

Balancing the Particular with the Common Good

Alexis de Tocqueville aptly wrote, “Without local institutions a nation may give itself a free government, but it has not got the spirit of liberty.” 23 23 Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, 1831 “Educational freedom,” writes Charles Glenn, “is one of the ways in which society provides itself with local institutions capable of engaging commitment on the part of ordinary citizens, especially parents. It also creates the social space to create institutions where children can be nurtured on the basis of a coherent worldview of the sort that, in a pluralistic society, no democratic government would be able—should be able—to impose. A diverse provision of schools is thus a necessary response to the growing diversity of cultural, worldview, and educational demands in a free society, and does justice to societal pluralism.” 24 24 Charles Glenn, Finding the Right Balance: Freedom, Autonomy and Accountability in Education (Utrecht: Lemma, 2002), 22.

Explaining further, Dr. Glenn writes,

A healthy society has communities of memory and mutual aid, of character and moral discipline, of transcendent truth and higher loyalty. . . . American society is best conceived as a community of communities. Citizens move in and out of communities, crossing line and languages in often confusing ways—confusing to themselves and to others. The resulting dissonance is called democracy. The national community, to the extent it can be called a community, is a very “thin” community. The myriad communities that constitute civil society are where we find the “thick” communities that bear heavier burdens of loyalty. 25 25 Glenn, Democratic Pluralism in Education (Journal of Markets and Morality Vol 21, N.1, Spring 2018), p. 134.

American society must not fear the moral and often religious convictions of its people but instead see these as wells of civic potential when properly integrated. A principled pluralism means engaging with differences—both in and between religious and secular communities—in a deeper way. Building a society that is deeply diverse and also just means thinking about those particular spaces or communities of practice that are poised to help cultivate important civic virtues. These spaces of coherence, which connect the need for belonging with human flourishing and civic formation, are vital at both the personal and societal levels.

A system that allows for educational pluralism aligns with a posture of deep respect for cultural diversity and the religious convictions that play an important role in shaping American democracy; it allows for the deep integration of these convictions and also ensures that the formative capacities of these communities are leveraged for the wider common good. In this way, a system of educational pluralism seeks to balance the needs of the state with those of the family and the community.

By combining what we have learned from nearly ten years of Cardus Education Survey data and recent thinking on educational pluralism, school culture, and citizenship, this paper hopes to inspire confidence in the valuable contributions of the non-government school sector while advancing a deeper argument for why a public system of educational pluralism is especially necessary in a deeply fractured America today. While the Cardus Education Survey data contributes to an understanding of the school-sector influence relationship to graduate outcomes, it also allows us to draw broad conclusions about the culture of these non-government school sectors based on a general pattern of living life, while recognizing that there is likely broad variation at the school level. The path forward requires a political strategy as well as a communal one, working in tandem: On the one hand, we need to rehumanize American politics, promote the respectful listening and partnership between state education departments and independent-school associations, remove impediments to the fuller participation of non-government-run schools, and ultimately create a legislative and administrative framework to govern and regulate education in the United States that advances the needs of schools and children over those of a system. On the other hand, we need thick and formative communities to engender a generative and generous spirit so that the beauty and goodness of these communities are widely felt beyond them. The hope for change in America ultimately lies in its people and communities, and in the networks that foster high moral character and the commitment to something bigger than oneself.

Cardus Education exists to provide reliable, credible

data for non-government types of education.