Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

This research study delves into the impact of the massive COVID-19 education disruption on schooling across Canada and the collateral damage now affecting the pandemic generation of students. Approaching four years after the initial shock, the fallout from “education’s long COVID” lingers on in the form of measurable learning loss, stunted social development, and mental-health side effects. Widening knowledge gaps, and attendant problems such as increased school violence and chronic student absenteeism, cry out for more visible, effective, better-coordinated plans for learning recovery.

Learning loss is real, and the latest research confirms that a substantial learning deficit arose early in the pandemic and has persisted over time. It is widespread, affecting student from elementary grades through high school, and is more pronounced in mathematics than in reading. Children with special needs suffered the most. As many as 200,000 students went missing from school at the height of the first COVID-19 wave of infections. Lower-income families were disproportionately affected, increasing the knowledge gap between students from affluent households and those from disadvantaged households. Smaller and more autonomous schools fared better and provided more consistent, mostly uninterrupted, learning. No one emerged unscathed.

Drawing on extensive research and analysis of the pandemic’s impact on education, this report provides a comprehensive diagnosis of what happened, pieces together the damage, compares the responses of schools across the educational spectrum, and identifies the most effective strategies in closing the persistent learning gap in post-pandemic times. It provides plenty of lessons for education policymakers, school-district leaders, parents, teachers, and families.

Introduction: Flying Blind through the Pandemic Crisis

School lockdowns and the unscheduled default to “emergency home learning” during the COVID-19 pandemic upset the lives of some 5.7 million Canadian students and their families. Schools across the country toggled between online and in-person learning as education authorities, acting mostly on public-health directives, imposed “circuit-breaking” quarantines and struggled to provide a modicum of “continuous learning.” 1 1 See T. Vaillancourt et al., “Children and Schools During COVID-19 and Beyond: Engagement and Connection Through Opportunity,” Royal Society of Canada, August 2021, https://rsc-src.ca/en/covid-19-policy-briefing/children-and-schools-during-covid-19-and-beyond-engagement-and-connection; P.W. Bennett, “Righting the Education Ship: Learning from the Powerful Lessons of the Pandemic,” Macdonald-Laurier Institute, April 18, 2023, https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/righting-the-education-ship-learning-from-the-powerful-lessons-of-the-pandemic/. Nearly four years after the initial global shock, a new form of “long COVID” has been diagnosed—“a substantial overall learning deficit” affecting the entire pandemic generation of school children. 2 2 See B. Walsh, “The Other Long Covid,” Vox, February 21, 2023, https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/23584869/covid-coronavirus-school-closures-remote-education-learning-loss-psychological-depression-teens; B.A. Betthäuser, A.M. Bach-Mortensen, and P. Engzell, “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Evidence on Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Nature Human Behaviour 7, no. 3 (2023): 375–85, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01506-4. Yet “learning loss” remains an undiagnosed problem in Canada and an understudied research topic.

Initial global studies of the pandemic’s impact on learning did not in most cases include Canada. While the education crisis registered with the popular media, students, and families, provincial education authorities, school-district superintendents, and university-based researchers were slow to come to terms with it. 3 3 J. Wise, K. Yamada, and P. Milton, “School Beyond COVID-19: Accelerating the Changes That Matter for K to 12 Learners in Canada,” Canadians for 21st Century Learning & Innovation, September 2021, https://c21canada.org/school-beyond-covid-19/. See also A. Hargreaves, “What the COVID-19 Pandemic Has Taught Us About Teachers and Teaching,” FACETS 6 (2021): 1835–63, https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0084; J. Whitley, M.H. Beauchamp, and C. Brown, “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Learning and Achievement of Vulnerable Canadian Children and Youth,” FACETS 6 (2021): 1693–1713, https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0096.

Leading Canadian education researchers were also loath to focus on “learning loss,” pursuing instead a “build back better” strategy of long-term transformation in teaching and learning. 4 4 See T. Vaillancourt, P. Szatmari, and J. Whitley, “Academically Speaking, the Kids Are Going to Be Okay,” Royal Society of Canada, July 13, 2020, https://rsc-src.ca/en/voices/academically-speaking-kids-are-going-to-be-okay. For a recent analysis of the prevailing mindset, see J. Jacobs, “Education’s ‘Long Covid’—Students Aren’t Catching Up,” Thinking and Linking (blog), July 13, 2023, https://www.joannejacobs.com/post/education-s-long-covid-students-aren-t-catching-up. That explains, in large part, why education authorities were left flying blind without much student-assessment data to track the pandemic’s impact on curricular delivery or student achievement.

Large-scale assessment research, which is used to draw reliable and comparative measures of student achievement and system-level judgments, was either suspended or limited during the pandemic. 5 5 K. Gallagher-Mackay and S. Sider, “Educational Recovery and Reimagining in the Wake of COVID-19: Principles and Proposals from a Multi-Stakeholder Workshop,” Laurier Centre for Leading Research in Education, 2022, https://researchcentres.wlu.ca/centre-for-leading-research-in-education/events.html. Regular student assessments at international, national, and provincial levels were substantially affected, largely as a result of the extraordinary extent of school-day cancellations and regular disruptions during the onslaught of the pandemic. The assessments that did take place did not have large participation levels, thereby affecting sampling designs. Without the benefit of aggregated student data, we are left to piece together how the pandemic affected student achievement. 6 6 L. Volante and D.A. Klinger, “COVID-19 and the Learning Loss Dilemma: The Danger of Catching Up Only to Fall Behind,” Education Canada Magazine, Spring 2023, https://www.edcan.ca/articles/covid-19-and-the-learning-loss-dilemma/. For an analysis on Canadian student performance on the 2021 grades 4–5 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study assessment, see P.W. Bennett, “The Unranking of Canada in Reading: Why Were Canada’s Students Unable to Keep Pace?,” Educhatter (blog), May 21, 2023, https://educhatter.wordpress.com/2023/05/21/the-unranking-of-canada-in-reading-why-were-canadas-students-unable-to-keep-pace/.

Most of the research demonstrates that public school systems were not only caught off-guard by the global upheaval but also mostly ineffective in their “pivot” to the “new normal” in the post–COVID-19 era. 7 7 Bennett, “Righting the Education Ship.” This report tackles the question of whether smaller and more autonomous schools outside the public system performed better and students experienced better instruction in alternative educational settings. 8 8 P. Marcus, D. Van Pelt, and T. Boven, “Pandemic Pivot: Christian Independent Schooling During the Initial 2020 Lockdown,” Cardus, 2021, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/research-report/pandemic-pivot/. It also assesses the impact on public system enrollment and the student fallout in terms of “lost” school children, and the size of the homeschool population.

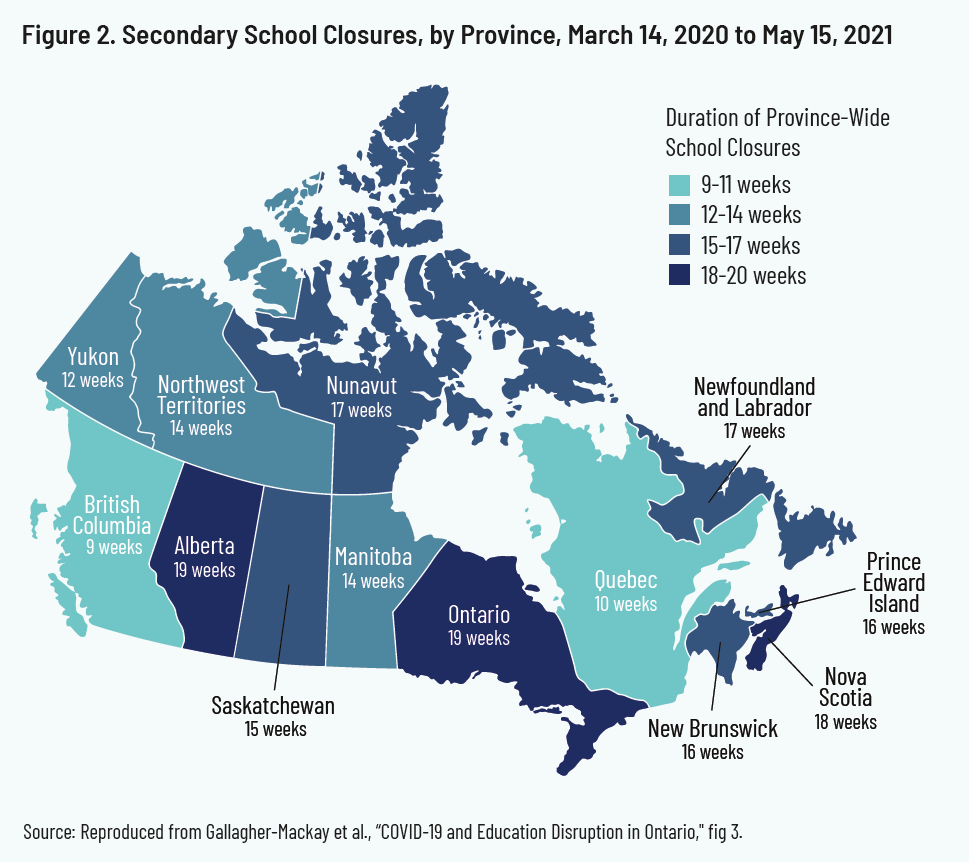

The COVID-19 education disruption was not short lived, and students did not bounce back. School closures were extended and widespread, claiming between eight and twenty weeks of in-school instruction from March 2020 until May 15, 2021. In the end, Canadian schools were closed or partially closed for a total of fifty-two weeks—placing the nation in the highest bracket globally for school closures. 9 9 Volante and Klinger, “COVID-19 and the Learning Loss Dilemma.” Most recently, researchers associated with the August 2021 Royal Society of Canada study, “Children and Schools During COVID-19 and Beyond,” concede that parental worries about learning loss and teachers’ concerns about widening inequalities were justified and warrant further study to assess the damage affecting children and teens. 10 10 T. Vaillancourt, S. Davies, and J. Aurini, “Learning Loss While Out of School—Is It Now Time to Worry?,” Royal Society of Canada, April 28, 2021, https://rsc-src.ca/en/voices/learning-loss-while-out-school-%E2%80%94is-it-now-time-to-worry. This report rises to that challenge, tackles many of the critical questions, and takes stock of the lessons.

Education in Crisis: The Shutdown, Learning Loss, and Lingering Effects

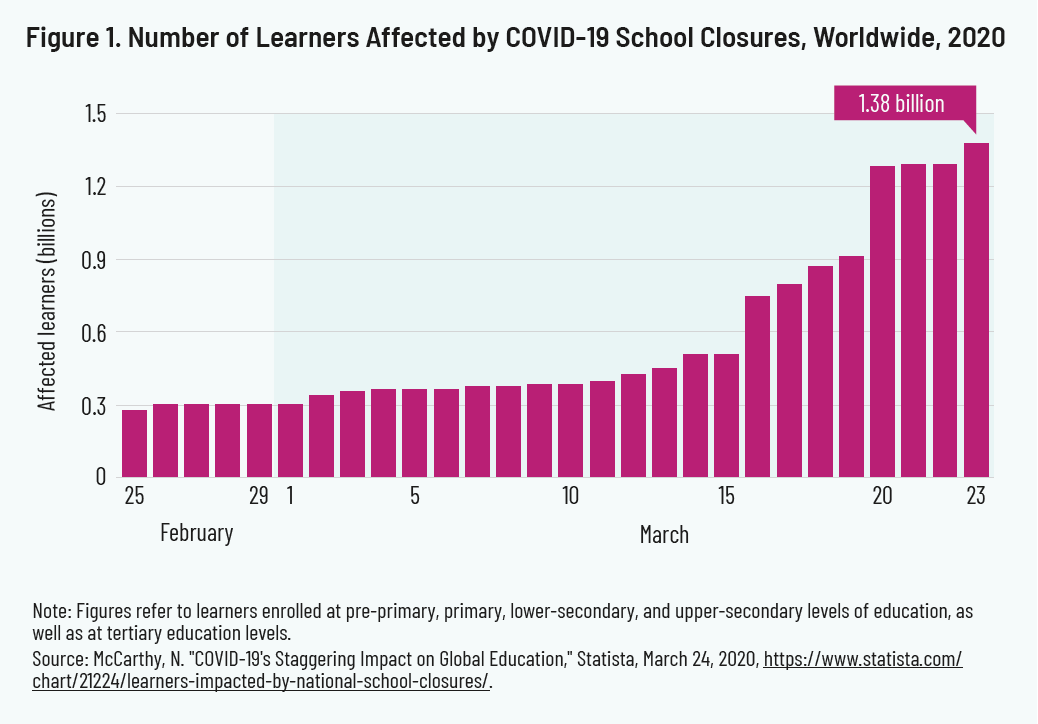

The shock of the COVID-19 pandemic turned the K–12 education world upside down and then unleashed a succession of school disruptions. UN Secretary-General António Guterres, speaking in August 2020, predicted that the effects were destined to become a “generational catastrophe” in education. 11 11 UNESCO, “UN Secretary-General Warns of Education Catastrophe, Pointing to UNESCO Estimate of 24 Million Learners at Risk of Dropping Out,” press release no. 2020/73, August 6, 2020, https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/un-secretary-general-warns-education-catastrophe-pointing-unesco-estimate-24-million-learners-risk. Since the pandemic first hit, the full extent of the learning slide affecting the world’s students, particularly the most disadvantaged, has become more and more visible. The initial North American research news alerts came from the Netherlands, the UK, and McKinsey & Company in the US. Eventually, mainstream news and social media shattered any sense of complacency, with an intermittent stream of Canadian research reports and surveys testifying to the combined academic and psychosocial effects on children and families. 12 12 E. Dorn, B. Hancock, J. Sarakatsannis, and E. Viruleg, “COVID-19 and Learning Loss—Disparities Grow and Students Need Help,” McKinsey & Company, December 8, 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-learning-loss-disparities-grow-and-students-need-help/; P.W. Bennett, “How Will the Education System Help Students Overcome COVID Learning Loss?,” IRPP Policy Options, February 1, 2021, https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/february-2021/how-will-the-education-system-help-students-overcome-covid-learning-loss/.

Canadian policy analyst Irvin Studin claimed that the public-health and economic “catastrophes” were accompanied by a crisis in education, as school systems suffered collapse. The pandemic had “thrown the world’s children, poor and rich alike, into three essential ‘buckets’” from September 2020 until June 2021: “Bucket 1 is those in physical (‘classical’) school; Bucket 2 is those in online (‘virtual’) schooling; and Bucket 3 is those NOT in ANY school AT ALL.” 13 13 I. Studin, “Third Bucket Kids and the Future of the Post-Pandemic World,” Institute for 21st Century Questions (blog), July 2021, https://www.i21cq.com/publications/third-bucket-kids-and-the-future-of-the-post-pandemic-world/. The biggest victims of the systems collapse were the “third-bucket kids,” who were “easily estimated to be in the hundreds of millions.” 14 14 Studin, “Third Bucket Kids and the Future of the Post-Pandemic World.” Out of an estimated 1.6 billion children worldwide, at least one million American children were “lost” in enrolment counts by some estimates, and according to Studin, an estimated 200,000 “third-bucket kids” were missing in Canada. 15 15 Studin, “Third Bucket Kids and the Future of the Post-Pandemic World”; I. Studin, “How to Fix Canada’s Education Catastrophe in Five Steps,” Globe and Mail, August 28, 2021, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-how-to-fix-canadas-education-catastrophe-in-five-steps/. See also I. Studin, Canada Must Think for Itself: 10 Theses for Our Country’s Survival & Success in the 21st Century (Richmond Hill, ON: Institute for 21st Century Questions, 2022). In the UK, the Centre for Social Justice delved more deeply, identifying some 100,000 “lost children” and the relative impact by school district, a condition that persisted post-pandemic. 16 16 Centre for Social Justice, “Lost but Not Forgotten: The Reality of Severe Absence in Schools Post-Lockdown,” January 2022, https://www.centreforsocialjustice.org.uk/library/lost-but-not-forgotten.

Canada’s most populous province was the only one subjected to thorough academic analysis, and that explains why Ontario became the test case for gauging the profound impact on children, teachers, and families. Ontario schools were closed for some twenty weeks from March 14, 2020 to May 15, 2021, more weeks than any other Canadian province or territory. The disruption was accompanied by multiple forms of educational provision, gaps in support for students with disabilities, and spikes in mental-health issues. The impact fell unevenly on children from low-income families, including those from racialized, Indigenous, and newcomer groups, deepening and accelerating inequities in education outcomes. 17 17 K. Gallagher-Mackay et al., “COVID-19 and Education Disruption in Ontario: Emerging Evidence on Impacts,” Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, June 2021, https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.34.1.0. See also J. DeJong VanHof, “Assessing Ontario’s Pandemic School Closures and What Students Need,” Cardus, 2022, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/perspectives-paper/assessing-ontario-s-pandemic-school-closures-and-what-students-need/.

Seeing the impact firsthand on her two increasingly tuned-out children, Vancouver mother Nancy Small cut to the heart of the matter: “Our kids are falling behind.” 18 18 C. Alphonso, “The COVID-19 Grading Curve: Schools Rethink Expectations for Students Who Have Lost Time,” Globe and Mail, February 16, 2021, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-the-covid-19-grading-curve-schools-rethink-expectations-for-students/. While the educational damage varied along regional, economic, and racial lines, provincial governments and district education authorities proved slow and uncoordinated in 2020–21 in their approach to closing the learning gap.

The COVID-19 school disruption caught everyone off guard, and provincial school systems, for the most part, continued to pursue pre-pandemic priorities. A whole generation of Canadian educational leaders steeped in school-transformation theories remained absorbed in hybrid “pedagogical and political projects” and were slow to address the immediate crisis. 19 19 See M. Fullan, “Large-Scale Reform Comes of Age,” Journal of Educational Change 10, no. 2 (2009): 101–13, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-009-9108-z; M. Fullan, “The Right Drivers for Whole System Success,” Centre for Strategic Education, 2021. School-change theorists and academic allies associated with the Canadian Education Association were quick to offer up familiar solutions dipped in COVID-19 and accompanied by a “build back better” narrative. 20 20 C. Chapman and I. Bell, “Building Back Better Education Systems: Equity and COVID-19,” Journal of Professional Capital and Community 5, no. 3/4 (2020): 227–36, https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-07-2020-0055. For a Canadian equivalent, see P. Osmond-Johnson, C. Campbell, and K. Pollock, “Moving Forward in the COVID-19 Era: Reflections for Canadian Education,” EdCan Network, May 6, 2020, https://www.edcan.ca/articles/moving-forward-in-the-covid-19-era/. The post-pandemic future, viewed through that lens, would be a clash between two mutually exclusive visions: social equality and student well-being, versus austerity and academic standards—good versus bad. 21 21 See A. Hargreaves, “Austerity and Inequality; Or Prosperity for All? Educational Policy Directions Beyond the Pandemic,” Educational Research for Policy and Practice 20, no. 1 (2020): 3–10, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-020-09283-5. This was not only a false dichotomy but also a misreading of the predicament confronting Canada’s schools and students.

A far better point of departure is provided in the World Bank’s report “The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses,” which surveyed the damage affecting school systems around the world. The immediate impacts were easier to spot, such as the economic and social costs, greater inequalities in access, and school-level health and safety concerns. Less evident was the longer-term impact of “learning loss” and its worst-case mutation, “learning poverty,” marked by the inability to read and understand a simple text by ten years of age. 22 22 World Bank, “The COVID-19 Pandemic: Shocks to Education and Policy Responses,” 2020, http://hdl.handle.net/10986/33696.

International research led the way, exposing the realities of learning losses that students experienced, shifts toward online and hybrid learning, and other effects associated with successive waves of the pandemic. While these studies remain scattered, a few reliable studies from Western nations such as the Netherlands, 23 23 Engzell, P., A. Frey, and M.D. Verhagen, “Learning Loss Due to School Closures during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” PNAS 118, no. 17 (2021): 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118. Germany, 24 24 D. Depping et al., “Kompetenzstände Hamburger Schüler*innen vor und während der Corona-Pandemie,” Die Deutsche Schule 17 (2021), https://doi.org/10.25656/01:21514. Belgium, 25 25 J.E. Maldonado and K. De Witte, “The Effect of School Closures on Standardised Student Test Outcomes,” British Educational Research Association 48, no. 1 (2021): 49–94, https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3754. and the US 26 26 Bailey, D.H. et al., “Achievement Gaps in the Wake of COVID-19,” Educational Researcher 50, no. 5 (2021): 266–75, https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211011237. confirm that learning stalled during the pandemic. They also add credence to the claim that the pandemic exacerbated existing inequalities, with students of lower socioeconomic status falling even further behind their more affluent peers. It is safe to conclude that students’ learning and academic resilience globally have been particularly threatened. 27 27 Volante and Klinger, “COVID-19 and the Learning Loss Dilemma.” For visual depictions of the estimates of learning losses during the COVID-19 pandemic, see H.A. Patrinos, “The Longer Students Were Out of School, the Less They Learned,” Journal of School Choice 19, no. 2 (2023): 161–75, https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2023.2210941; Bach-Mortensen, and Engzell, “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” fig 4.

Post-pandemic problems have surfaced and been diagnosed as signs of lingering effects. Schools are not as safe, and at times have many empty desks. Highly publicized outbreaks of school violence from 2021 onward in the greater Toronto area, Ottawa, and southwestern Ontario broke the normal pattern of silence and drew attention to ongoing physical violence, workplace safety concerns, and chaos in and out of classrooms. 28 28 H. Rivers, “Violence in Local Elementary Schools Has Doubled Since Last Year: Union,” London Free Press, November 10, 2022, https://lfpress.com/news/local-news/violence-in-london-area-schools-becoming-normalized-teacher-union-leader; P.W. Bennett, “Canada’s Schools Have Descended into a Violent Hell and We Let It Happen,” National Post, February 27, 2023, https://nationalpost.com/opinion/paul-w-bennett-canadas-schools-have-descended-into-a-violent-hell-and-we-let-it-happen; J. Brean, “‘We’re All Traumatized’: The Inside Story of a Middle School in Crisis,” National Post, June 26, 2023, https://nationalpost.com/feature/a-toronto-area-middle-school-is-in-crisis-administrators-pin-the-blame-on-teachers. A March 2023 stabbing incident at C.P. Allen High School in Bedford, Nova Scotia, drew national attention to the high incidence of violence in schools. Surveys conducted by the Nova Scotia Teachers Union and the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario testified to the rise in reported physical violence, witnessed and personally experienced by teachers and education assistants. 29 29 See national media coverage of C.P. Allen stabbings in M. Macdonald and M. Tutton, “Halifax High School Student Charged with Attempted Murder After School Stabbings,” Globe and Mail, March 21, 2023, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-halifax-high-school-student-charged-with-attempted-murder-after-school/; CBC News, “Most Ontario Elementary School Teachers Experienced or Witnessed School Violence, Survey Finds,” May 15, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ontario-elementary-school-violence-1.6843765; A. Cooke, “Almost 90% of N.S. Teachers Believe School Violence on the Rise: Survey,” Global News, April 27, 2023, https://globalnews.ca/news/9654975/nova-scotia-teachers-union-school-violence-survey/.

Monitoring and analyzing post-pandemic issues remains compromised in our school systems. School violence is not tracked nationally, so we are left to piece it together from disparate provincial data, PREVNet resources, media coverage of school-district crises, or periodic commentaries. 30 30 See PREVNet, “Bullying: Facts and Solutions,” https://www.prevnet.ca/bullying/facts-and-solutions; W.M. Craig and D.J. Pepler, “Understanding Bullying: From Research to Practice,” Canadian Psychology 48, no. 2 (2007): 86–93, https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/cp2007010. Education researcher Anton Birioukov has claimed that education research is “absent on absenteeism” and calls for Canadian academics to begin filling the gap to assist in reducing its incidence. 31 31 A. Birioukov, “Absent on Absenteeism: Academic Silence on Student Absenteeism in Canadian Education,” Canadian Journal of Education 44, no. 3 (2021): 718–23, https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/4663.

Chronic student absenteeism is now rife right across North America. “Staying home” during the pandemic has morphed into “long COVID,” in the form of alarming rates of student absence, in which missing 10 percent of school days appears to be normalized in provincial school systems. 32 32 B.V. Tonnez, “Millions of Kids Are Missing Weeks of School as Attendance Tanks Across the US,” Associated Press, August 11, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/back-to-school-attendance-pandemic-chronic-absenteeism-90c05e3013b72802439565250d1adc33_2; M. Rogers, “For the Sake of Our Kids, We Can’t Let Absenteeism Become Normalized,” Globe and Mail, December 12, 2022, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-for-the-sake-of-our-kids-we-cant-let-absenteeism-become-normalized/. Absenteeism remains widespread but mostly underreported in Canadian K–12 education.

Piecing It Together: Learning Loss, Social Harms, Disparities

School closures caused major disruptions, but the upheaval also precipitated policy responses relating to public health that fundamentally altered the K–12 experience in Canada. Social distancing and other health directives wrought fundamental changes in the so-called grammar of schooling, including smaller cohorts, spaced classroom seating, and masking in halls and classrooms. Changes were also made in the ways in which the curriculum was delivered from province to province.

Public-health directives drove much of the education-policy agenda from March 2020 to June 2021. The provision of in-person, blended, or full-time virtual learning was dependent on the identified local and provincial risk levels of COVID-19 infection. Provincial and district responses ranged all over the map. 33 33 See L. Volante, C. Lara, D.A. Klinger, and M. Siegel, “Academic Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Triarchic Analysis of Education Policy Developments Across Canada,” Canadian Journal of Education 45, no. 4 (2023): 1112–140, https://doi.org/10.53967/cje-rce.5555.

Parents of elementary-school students in Ontario and other provinces and territories could choose between in-person and virtual learning environments for their children. Students in secondary school had split schedules in a blended-learning model. Under those experimental schedules, smaller class cohorts of students attended school part of the time in person and the other part online, under what was termed “emergency home learning.”

Full-time e-learning was implemented for older students in secondary schools in New Brunswick and some other areas of the country. In some New Brunswick school districts, in-person attendance was the expectation with few exceptions (e.g., high-risk or living with high-risk individuals). In others, attendance-taking was irregular and largely unreported, especially during the early phase of “triage” remote learning. 34 34 M.K. Barbour et al., “Understanding Pandemic Pedagogy: Differences Between Emergency Remote, Remote, and Online Teaching,” Virginia Tech and Canadian eLearning Network, December 2020, http://hdl.handle.net/10919/101905.

All provinces and territories developed reactive contingency plans as COVID-19 risk spiked and fluctuated in local communities. Toggling between in-person and online learning emerged as the “new normal” for large chunks of two school years. Health-and-safety directives and protocols reshaped classrooms and disrupted student life. Social-distancing measures affected students’ opportunities to interact with their peers and teachers. Mandatory mask-wearing was implemented in most schools, as was smaller class sizes, although the particular directives were dependent on the local degree of risk or educational jurisdiction. 35 35 T. Vaillancourt, P. Szatmari, K. Georgiades, and A. Krygsman, “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Mental Health of Canadian Children and Youth,” FACETS 6, no. 1 (2021): 1628–648, https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0078. For example, mandatory mask-wearing was implemented in Ontario for grades 1 to 12, but in Alberta for grades 4 to 12 during certain periods during those two school years. Mask-wearing was also dependent on location and activity (required on buses and for large gatherings) and on community level of risk tolerance, with significant differences across urban-rural lines. The school disruptions were prolonged, unpredictable, and unsettling for students, teachers, and families.

Actual data from parent surveys, school-district reports, and quantitative studies reveal a major disconnect in perspectives between most educational experts and those at the school level: parents and classroom teachers. Surveys conducted by the Alberta Teachers’ Association and the Canadian Teachers’ Federation demonstrate the depth of parent and teacher concerns over erosions of children’s skills and mental health. After the first phase of COVID-19 shutdowns, parents in the Hamilton-Wentworth Board also expressed a strong desire for more teacher-led synchronous learning activities during regular school hours. The vast majority of the parents, when given the choice, still opted for in-person schooling, with the possible exception of those who lived in multigenerational households. 36 36 P.W. Bennett, “End of Topsy-Turvy School Year: 5 Education Issues Exposed by the COVID-19 Pandemic,” The Conversation Canada, June 6, 2021, https://theconversation.com/end-of-topsy-turvy-school-year-5-education-issues-exposed-by-the-covid-19-pandemic-161145. Learning loss became a major preoccupation as the evidence accumulated that the “pandemic generation” was off track and struggling to catch up in their schooling in the wake of the shutdowns. 37 37 P.W. Bennett, “Why Education Policy Is Failing Us in COVID-19 Times,” The Hub, October 28, 2021, https://thehub.ca/2021-10-28/paul-w-bennett-why-education-policy-is-failing-us/.

COVID-19 responses were all over the map and lacking in any sense of coordination. Given the disaggregated nature of the educational research, piecing it all together is a formidable challenge. Indeed, much of the post-pandemic analysis mirrors the priorities and concerns of the researchers. The overall approach reflects a child-development orientation, focusing on fostering optimal conditions for growth and wellness rather than academic skills and recovery. Students’ learning and academic achievement may have been adversely affected, but the focus has been on learners who were academically vulnerable before the pandemic, the need for healthy outdoor play, and the immediate damage in terms of child mental and physical health. 38 38 See Whitley, Beauchamp, and Brown, “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Learning and Achievement of Vulnerable Canadian Children and Youth”; L. McNamara, “School Recess and Pandemic Recovery Efforts: Ensuring a Climate that Supports Positive Social Connection and Meaningful Play,” FACETS, November 4, 2021, https://www.facetsjournal.com/doi/10.1139/facets-2021-0081; S. Moore et al., “Impact of the COVID-19 Virus Outbreak on Movement and Play Behaviours of Canadian Children and Youth: A National Survey,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 17, no. 1 (2020): 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-00987-8.

Identified Types of Impact

Learning Loss for All Children

Public concerns about learning loss dominated the news media, policy briefs, and opinion sections of newspapers and electronic media. For the vast majority of Canada’s 5.7 million students in kindergarten through grade 12, the biggest impact was on identifiable shortfalls in academic skills and curricular knowledge, most evident in the gaps between the academic performance of some groups of students compared with others. Canada’s leading university-based education researchers’ first reaction was to discount claims of “learning loss” and generally downplay the problem. 39 39 See P. Osmond-Johnson, C. Campbell, and K. Pollock, “Moving Forward in the COVID-19 Era: Reflections for Canadian Education,” EdCan Network, May 6, 2020, https://www.edcan.ca/articles/moving-forward-in-the-covid-19-era/; A. Hargreaves and D. Shirley, Well-Being in Schools: Three Forces That Will Uplift Your Students in a Volatile World, ASCD, December 2021. For the background analysis, see Y. Zhao, “Build Back Better: Avoid the Learning Loss Trap,” Prospects 51, no. 4 (2022): 557–61, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-021-09544-y; A. Hargreaves, “Large-Scale Assessments and Their Effects: The Case of Mid-Stakes Tests in Ontario,” Journal of Educational Change 21, no. 3 (2020): 393–420, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09380-5. Judging from their initial responses, much of that antipathy was rooted in a passive resistance to giving priority to the core function of academic learning, the “narrowness” of standardized student assessments, and the unintended effects of standards-based education for students from racialized and marginalized communities.

Impact on Vulnerable Canadian Children and Youth

Learning gaps were more pronounced for vulnerable students during and immediately after the COVID-19 school shutdowns. In the words of researchers Whitley, Beauchamp, and Brown, “Many children and youth in Canada [who were] identified as vulnerable due to educational, environmental, and social factors . . . [were] more likely to be negatively affected by events that cause significant upheaval in daily life,” such as COVID-19. “Physical distancing, school closures, and reductions in community-based services [had] the potential to weaken the systems of support necessary for these children to learn and develop. Existing inequities in educational outcomes . . . [were] greatly exacerbated as cracks in our support structures [were] revealed.” 40 40 J. Whitley, M.H. Beauchamp, and C. Brown, “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Learning and Achievement of Vulnerable Canadian Children and Youth,” FACETS 6 (2021): 1693–1713, https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2021-0096. Media stories and anecdotal reports testified to the severity of student disengagement, chronic attendance problems, declines in academic achievement, and decreased credit attainment during the pandemic—most acute among those already at risk. 41 41 Whitley, Beauchamp, and Brown, “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Learning and Achievement of Vulnerable Canadian Children and Youth”; P. Srivastava, T. Tan Lau, D. Ansari, and N. Thampi, “Effects of Socio-Economic Factors on Elementary School Student COVID-19 Infections in Ontario, Canada,” MedRxiv (2022): 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.04.22270413. Many families struggled mightily during the pandemic lockdowns, and this contributed to increased stress, and, in some cases, trauma, which in turn affected the educational well-being of children.

School systems did prioritize the provision of extra resources for at-risk children and their families. School re-opening was delayed in March 2020 in some regions until students in impoverished communities or identified by social-service agencies as vulnerable were provided with laptops and assisted in finding reliable home-based Internet access. In some cases, smaller class cohorts found favour with teacher-educators committed to providing safe, inclusive, and supportive classrooms integrating social-service supports. Much of that social-service support network was disrupted and vulnerable, with children and teens sometimes left to fend for themselves, joining the swollen ranks of “third-bucket kids.” These lost schoolchildren gradually returned, but generally only with the resumption of regular, consistent, in-person schooling. 42 42 S. Subramanian, “The Lost Year in Education,” Maclean’s, June 4, 2021, https://macleans.ca/longforms/covid-19-pandemic-disrupted-schooling-impact/.

Impact on Children and Youth with Special Education Needs

Children with special education needs were hardest hit by the school lockdowns and the regular and ongoing interruption of education and community support services. An estimated one million Canadian children have been diagnosed with special needs, representing some 10 percent to 20 percent of total student enrollment. 43 43 J. Whitley, “Coronavirus: Distance Learning Poses Challenges for Some Families of Children with Disabilities,” The Conversation, June 1, 2020, https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-distance-learning-poses-challenges-for-some-families-of-children-with-disabilities-136696. Many of these disabilities, such as dyslexia, autism spectrum disorder, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, affect cognition or academic functioning. Before the pandemic, these students typically received a range of services, from formal and informal support to individualized instruction and support from the school and other providers. 44 44 Whitley, Beauchamp, and Brown, “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Learning and Achievement of Vulnerable Canadian Children and Youth,” 1696. All of this was imperiled by the pandemic and shutdowns.

Most of the authoritative research on impacts reflects the perspectives of parents and caregivers. One American study in 2020, based on a small sample of seventy-seven families with special-needs children in California and Oregon, documented significant challenges, including reduction in services and the burden of staying home from work to care for the children. 45 45 See C. Neece, L.L. McIntyre, and R. Fenning, “Examining the Impact of COVID-19 in Ethnically Diverse Families with Young Children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities,” Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 64, no.10 (2020): 739–49, https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12769. Other studies show that the pandemic worsened symptoms of the disorders themselves and associated comorbidities, such as student-behaviour difficulties for students with ADHD, and increased anti-social behaviour among those with autism spectrum disorder. Online schooling and video-conferencing platforms presented additional difficulties for children with pre-existing attentional or perceptual impairments. 46 46 Whitley, Beauchamp, and Brown, “The Impact of COVID-19 on the Learning and Achievement of Vulnerable Canadian Children and Youth,” 1696–7. One of the few Canadian studies, led by University of Ottawa researcher Jess Whitley, based on a survey of 265 parents and twenty-five in-depth interviews, testifies to the experiences of parents as educator-caregivers and increased stress levels in the home. 47 47 J. Whitley et al., “Diversity via Distance: Lessons Learned from Families Supporting Students with Special Education Needs During Remote Learning,” Education Canada Magazine, Winter 2020, https://www.edcan.ca/articles/diversity-via-distance/.

Uneven Impact: On Struggling and Marginalized Communities

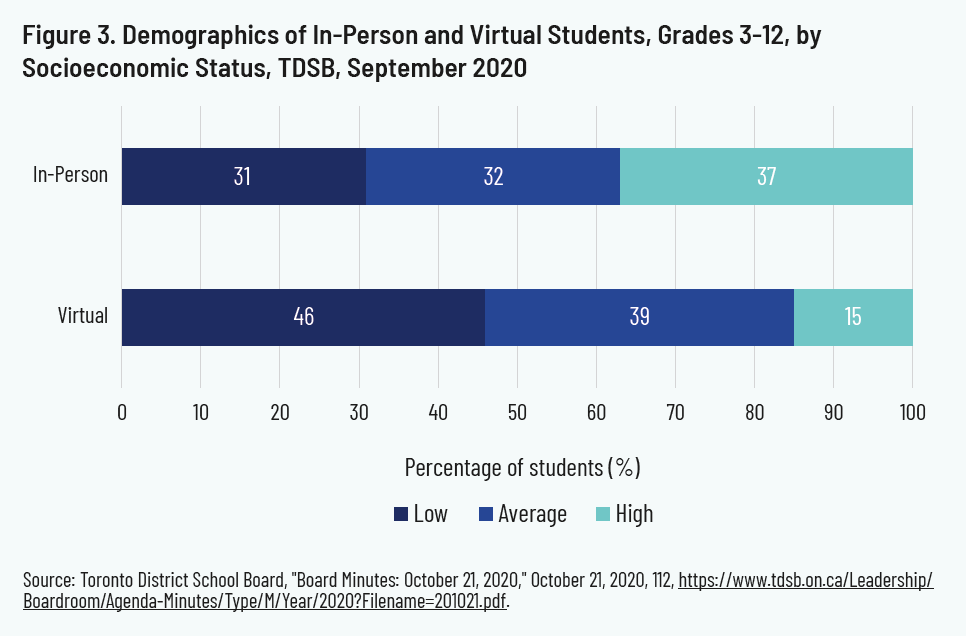

Public-health measures put in place to curb waves of COVID-19 infections affected individuals, groups, and communities to varying degrees. Surveying infection-rate data, it was clear that the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infections was also disproportionately concentrated in residential areas with lower-income and racialized groups. 48 48 See, for example, J. Kerr and C. Wang, “Surge of Cases in Coronavirus Hot Spots Threatens to Close Schools in Major Cities,” Globe and Mail, October 22, 2020, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-surge-of-cases-in-coronavirus-hot-spots-threatens-closure-of-major/. “As with most systemic challenges,” one US study reminded us, “those who are most impacted by crises are those who are already the most vulnerable.” 49 49 N.G. Wilke, A.H. Howard, and D. Pop, “Data-Informed Recommendations for Services Providers Working with Vulnerable Children and Families during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Child Abuse & Neglect 110, part 2 (2020), 104642, 2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104642. Newcomers, refugee children, and the poor were the most susceptible to the significant upheaval in daily life. 50 50 K. Choi et al., “Studying the Social Determinants of COVID-19 in a Data Vacuum,” Canadian Review of Sociology 58, no. 2 (2021): 146–64, https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12336; S. Craig et al., “The Unequal Effects of COVID-19 on Multilingual Immigrant Communities,” Royal Society of Canada, March 24, 2021, https://rsc-src.ca/en/voices/unequal-effects-covid-19-multilingual-immigrant-communities. The closing of community centres, ice rinks, and supervised playgrounds weakened the community network and systems of support, particularly in larger cities and towns. Geographic analyses revealed that school closures adversely affected lower-income and racialized groups in Canada’s largest city, Toronto, and hit hard in isolated rural places and Indigenous communities. 51 51 J. Clinton, “Supporting Vulnerable Children in the Face of a Pandemic,” Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, 2020, https://apo.org.au/node/303563; see also R.I. Silliman Cohen and E.A. Bosk, “Vulnerable Youth and the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Pediatrics 146, no. 1 (2020): 1–3, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1306. For a Canadian case study, see D. Bascaramurty and C. Alphonso, “How Race, Income, and ‘Opportunity Hoarding’ Will Shape Canada’s Back-to-School Season,” Globe and Mail, September 5, 2020, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-how-race-income-and-opportunity-hoarding-will-shape-canadas-back/.

Comparing School Sector Responses: What Were the Lessons?

Public schools bear a heavy responsibility: to educate all children wherever they live and from every segment of society. In normal times, reaching and properly serving everyone seeking a K–12 education is a challenge, and more so when a global pandemic precipitates radical public-health measures, including system-wide school shutdowns. 52 52 For an early forecast, see P.W. Bennett, “Lessons on E-Learning from the Front Lines of the Pandemic,” National Post, March 17, 2020, https://nationalpost.com/opinion/paul-w-bennett-lessons-on-e-learning-from-the-front-lines-of-the-pandemic. During such crises, media coverage tends to focus on mainstream public schools, leaving alternative forms of schooling out or reducing them to stereotypes. From March 2020 to the end of June 2021, during the first phase of the disruption, the glare of public scrutiny shone on mainstream schooling, rendering alternative forms or other education sectors all but invisible. Shining the light on the responses of each segment provides a few possible lessons.

Pandemic Pivot in Public Schools

Canada’s largest school district, the Toronto District School Board (TDSB), became the lightning rod when COVID-19 hit and knocked out most schools and exemplified the problems, writ large, afflicting every public school system from coast to coast. One stinging Toronto Life article, described the transition and roll-out of remote (home) learning as an “unmitigated disaster” for students, families, and teachers. 53 53 R. Robin, “Class Dismissed: The TDSB’s Rollout of Online Learning Was an Unmitigated Disaster,” Toronto Life, August 11, 2020, https://torontolife.com/city/the-tdsbs-rollout-of-online-learning-was-an-unmitigated-disaster/. In Ontario, the COVID-19 upheaval came on top of a protracted and turbulent labour war between the Doug Ford government and the teachers’ unions.

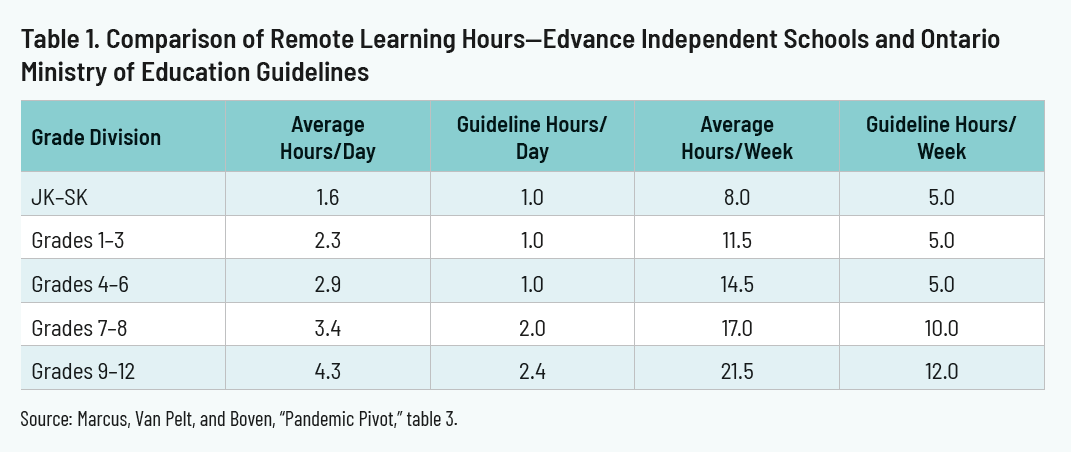

Public school systems such as the TDSB were caught in limbo after the March school break in 2020. In late March, in-person schooling was suspended, and the Ontario Ministry of Education weighed in with general guidelines for the provision of student work to be carried out during remote learning. Those guidelines set out minimum expectations, which recommended five hours of work a week for kindergarten to grade 6, ten hours a week for grades 7 and 8, three hours a week per course for semestered high-school students, and one and a half hours a week per course for non-semestered students. 54 54 Ontario Office of the Premier, “Ontario Extends School and Child Care Closures to Fight Spread of COVID-19,” news release, Government of Ontario, March 31, 2020, https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/56529/ontario-extends-school-and-child-care-closures-to-fight-spread-of-covid-19; K. Rushowy and I. Teotonio, “Ontario Launches ‘Learn at Home’ Online Program for Students During School Shutdown,” Toronto Star, March 20, 2020, https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/ontario-launches-learn-at-home-online-program-for-students-during-school-shutdown/article_5bbc5a0b-a848-5a93-9ac9-f987a97555a5.html; see also T. Huynh and I. Roy, “Tracking COVID-19 in Toronto Schools,” The Local, September 8, 2021 to March 10, 2022, https://thelocal.to/school-tracker/. In the government’s initial announcement in March 2020, no mention was made of providing continuity of learning through synchronous instruction, using video conferencing platforms such as Zoom, which was initially resisted by many teachers with the support of their federations.

Alberta was the first province out of the gate with pandemic education transition plans, and they spelled out more clearly the expectations of teachers in the provision of student work. Most provinces elected to adopt guidelines modelled after the Ontario framework and were looser about expectations during at-home “remote learning.” The labour turmoil in Ontario compounded the problem of trying to chart a consistent and effective form of alternative provision. One teachers’ union rep in Toronto’s east end advised teachers to do the minimum. “Don’t go above and beyond” was the message, and it ended up in email communications sent to teachers. A few vocal parents in the TDSB testified to the complete breakdown in their children’s education and attributed it to teachers’ unions throwing up roadblocks to the provision of continuous learning. 55 55 M. Schatzker, “Teachers’ Unions Are Blocking Better Education During the Pandemic,” National Post, June 2, 2020, https://nationalpost.com/opinion/opinion-teachers-unions-are-blocking-better-education-during-the-pandemic. Identifying an estimated 100,000 children by some accounts without laptops or reliable internet access, and then providing those resources, delayed the resumption of schooling and rendered the provision of home learning doubly difficult. As late as August 19, 2020, the chair of the TDSB stated that, “We just do not have enough resources to provide [remote learning] on an individual school basis.” 56 56 CBC News, “TDSB Wants to Centralize Remote Learning in a ‘Virtual School’ as Part of COVID-19 Plan,” August 19, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/tdsb-remote-learning-virtual-school-1.5691770.

Executing the pandemic pivot presented problems for public school systems. Access to comprehensive Canadian research data is problematic, so information must be gleaned from the United States as provided by the US Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics. One national survey found that only 4 percent of American public school principals reported that their students could get access to the internet in spring 2020, versus 58 percent of private-school principals. Both public and private schools reported that roughly half of their students learned with paper materials. The biggest difference was in the provision of direct and synchronous instruction. Only 47 percent of public school teachers reported that they regularly employed video or telephone conferencing, but roughly two out of three (63 percent) private-school teachers reported doing so. 57 57 M. Berger et al, “Impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic on Public and Private Elementary and Secondary Education in the United States (Preliminary Data): Results from the 2020–21 National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS),” National Center for Education Statistics, February 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2022/2022019.pdf. That, in all likelihood, was the case in Canada, as well.

Publicly funded schools struggled during the first phase of the COVID-19 disruption. From March 14 through to April 5, 2020, Ontario’s approximately 4,000 schools went entirely without teacher-led instruction. 58 58 Ontario Office of the Premier, “Statement from Premier Ford, Minister Elliott, and Minister Lecce on the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19),” statement, March 12, 2020, https://news.ontario.ca/en/statement/56270/statement-from-premier-ford-minister-elliott-and-minister-lecce-on-the-2019-novel-coronavirus-covid-19. The vast majority of public schools remained closed until the fall of 2020. In some schools, student grades were essentially frozen, few if any tests were administered, and final grades were based on estimates of achievement. Critics and many parents of school-age children claimed that little formal education took place in Ontario’s publicly funded schools from March 12, 2020 to the end of the school year. According to a spring 2021 survey of 9,500 Canadian elementary and secondary teachers from CBC News, 55 percent of these educators noted that fewer students were fulfilling learning objectives than students in previous years, while 75 percent said students were not on track with curriculum schedules, and 70 percent expressed concern that some students would stay behind academically. 59 59 See Ontario Ministry of Education, “Letters to Ontario’s Parents from the Minister of Education,” Government of Ontario, March 24, 2020, https://www.ontario.ca/page/letter-ontarios-parents-minister-education. See also Gallagher-Mackay and Srivastava et al., “COVID-19 and Education Disruption in Ontario”; J. Wong, “With Summer Vacation Looming, Educators Worry about Lasting Fallout of Pandemic Schooling,” CBC News, May 17, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/teacher-questionnaire-pandemic-yearend-1.6025149.

Pandemic Response of Independent Schools

Most independent schools enjoyed the advantages of clarity in mission, size, and agility to pivot to online learning and providing continuity of educational services. One thing is abundantly clear: the best-known independent schools, most of which are associated with the “top-tier” Canadian Accredited Independent Schools, number only 94 schools and represent a rather small segment of the total independent-school student enrolment. Indeed, based on the research available, the vast majority of independent schools in Canada serve students and families drawn from middle- to upper-middle-income households, not dissimilar from the majority of families who send their children to “free,” or publicly funded, schools. Three different studies, undertaken in Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia, confirm that pattern and the fact that the most typical family profile consists of two working parents in the middle- to upper-middle range of income. The 2019 Cardus study “Who Chooses Ontario Independent Schools and Why?” found that two-thirds or more of independent-school parents surveyed reported making “major financial sacrifices” to pay the tuition fees. 60 60 D. Hunt, J. DeJong VanHof, and J. Los, “Naturally Diverse: The Landscape of Independent Schools in Ontario,” Cardus, 2022, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/naturally-diverse/; J. Clemens, S. Parvani, and J. Emes, “Comparing the Family Income of Students in British Columbia’s Independent and Public Schools,” Fraser Institute, 2017, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/comparing-family-income-of-students-in-BCs-independent-and-public-schools.pdf; A. MacLeod, S. Parvani, and J. Emes, “Comparing the Family Income of Students in Alberta’s Independent and Public Schools,” Fraser Institute, 2017, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/comparing-the-family-income-of-students-in-albertas-independent-and-public-schools.pdf; D. Van Pelt, D. Hunt, and J. Wolfert, “Who Chooses Ontario Independent Schools and Why?,” Cardus, 2019, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/who-chooses-ontario-independent-schools-and-why/.

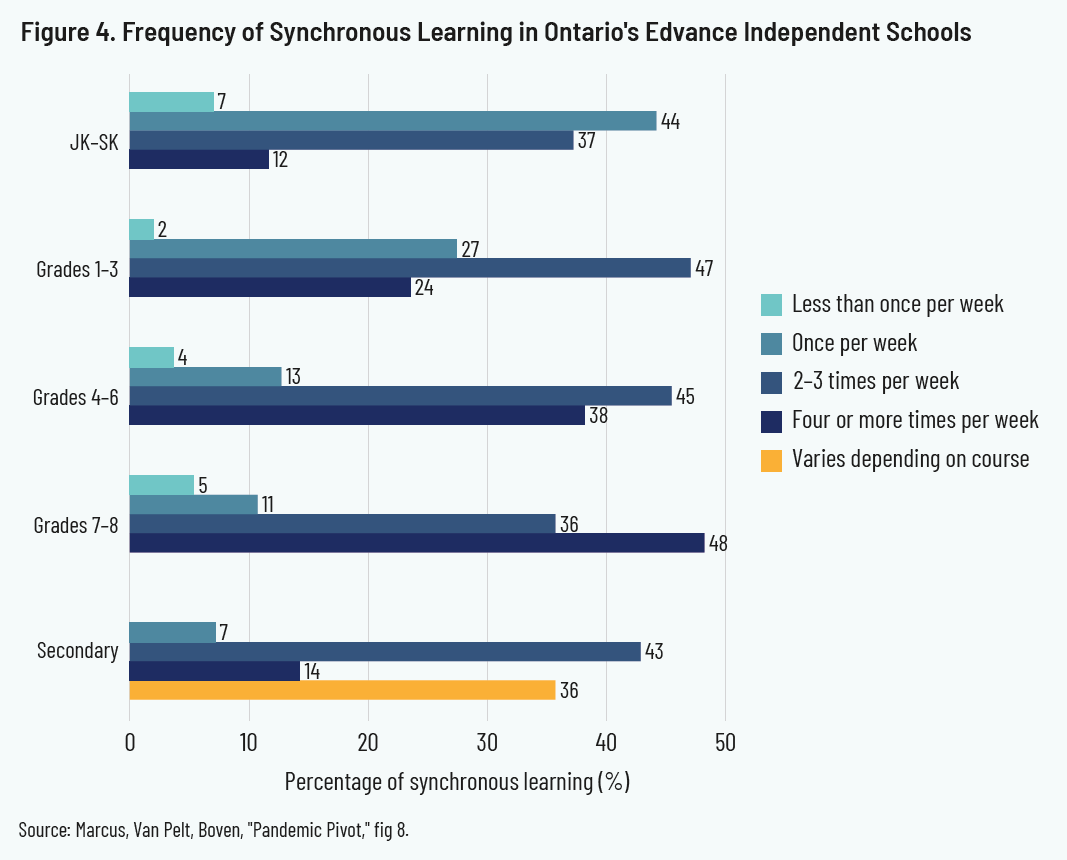

Cardus’s June 2021 research report, aptly titled “Pandemic Pivot,” delved into the performance of one large and fairly representative network of Ontario independent schools, providing us with evidence that smaller schools likely managed the pandemic more successfully than the public schools did. The report was based on a survey conducted in June 2020 of eighty-one schools (sixty-nine of which participated) affiliated with the Edvance Christian Schools Association in Ontario and Prince Edward Island. It examined how these schools pivoted from offering face-to-face education to remote learning from March to June 2020. 61 61 P. Marcus, D. Van Pelt, and T. Boven, “Pandemic Pivot: Christian Independent Schooling During the Initial 2020 Lockdown,” Cardus, 2021, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/research-report/pandemic-pivot/.

The key finding was that despite the sudden closure of all school buildings, almost half of the schools surveyed did not miss a single day of instruction. In fact, on average, these schools missed less than four days of instruction during the transition to emergency remote learning. In addition, for the remainder of the school year, the majority of schools exceeded the government’s recommended daily instructional time. One side benefit was that some highly motivated students reportedly thrived during the shutdown, mainly those with the skills and capabilities to embrace project-based learning activities. Some Edvance schools also prioritized the maintenance of special-education services. Almost all of the schools offered special-education services (97 percent), and, of these schools, most continued offering those support services for their students (88 percent) during the massive disruption.

From March to June 2020, students in the Edvance independent schools fared better than their public-school counterparts. School resumed quickly, and educators worked hard from the beginning of the pandemic to make online learning better. While all students in every education sector suffered from disrupted school and social relationships, those in the Edvance schools continued to participate in community online gatherings, including weekly chapel services. Graduation ceremonies were not cancelled for most students, and the majority of schools ended the year with unique drive-by or virtual graduation and learning celebrations. Schools were sustained by financial belt-tightening, including staff layoffs, in order to provide financial aid to support those struggling to pay tuition fees. Some 83 percent of the schools provided financial assistance to those in need.

Smaller schools, such as those in the Edvance network, with mostly 100 to 400 students, demonstrated the advantages of smaller, more agile and responsive schools. Parents worked closely with teachers, and community members simply rolled up their sleeves, doing whatever it took to ensure learning continuity as the school and the students persevered throughout the crisis. 62 62 Marcus, Van Pelt, and Boven, “Pandemic Pivot,” 9–12, 27–29.

The findings of the June 2021 Cardus study reflect a consensus based upon commentaries and feedback from a broader cross-section of independent schools. Enrolments in independent schools grew during the pandemic, as parents with the financial means sought more continuity in learning, safer and more protected learning spaces, and a welcome break from the protracted duration of hybrid learning in public school systems. Canada’s private school directory, Our Kids, provided a rather rosy assessment of private schools’ response to COVID-19, but anecdotal evidence supported the claim that their small size and agility made a difference. Most of the evidence suggests that students received more teacher instruction, experienced fewer cancellations, and private schools used video conferencing more effectively to maintain a sense of shared community compared to public schools in Canada. 63 63 Our Kids Media, “An Unscheduled Revolution Is Taking Place at Canadian Independent Schools,” news release, April 9, 2020; Our Kids, “Private Schools’ Responses to COVID-19,” spring 2020, https://www.ourkids.net/school/responding-to-covid-19; G. Livingston, “Pandemic Learning Gaps Have Parents Digging Deep to Put Their Kids in Private School,” Globe and Mail, June 18, 2022, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/investing/personal-finance/household-finances/article-private-school-enrollment-rising-can-you-afford-it/.

Impact on Homeschool Population

Home education flew below the radar and, even in the midst of the pandemic, attracted little or no attention. Surveying the media coverage, one might assume that from March 2020 through the 2020–21 school year, most if not all families never tried educating their kids themselves. That is precisely why one of the unanswered questions is, What impact did school shutdowns, hybrid schedules, and disruptions have on “leakage” from the public school system? The general pattern is beginning to emerge as a result of two recent reports, the latest Statistics Canada data, and a preliminary August 2022 assessment generated by Joseph Woodard of the Canadian Centre for Home Education. 64 64 See Statistics Canada, “Homeschool Enrollment Doubled in Canada during COVID-19 Lockdowns,” November 8, 2022, https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/2210-homeschool-enrollment-doubled-canada-during-covid-19-lockdowns; J. Woodard, “Growth in the Homeschooled Population,” Canadian Centre for Home Education, August 8, 2022, https://cche.ca/growth-in-the-homeschooled-population/.

Public school shutdowns of such duration generated a parent backlash and growing demands for the return of in-person school after each successive wave of COVID-19 from the initial spike through the highly contagious Omicron variant. Out-migration from public schools created what was termed a “COVID bounce” in homeschool enrolment, most evident in the United States. 65 65 J. Woodard, “Growth in the Homeschooled Population,” Canadian Centre for Home Education, August 8, 2022, https://cche.ca/growth-in-the-homeschooled-population/. Enrolment in homeschooling in Canada also experienced a similar spurt, albeit from a smaller initial baseline of children, registered with provinces and territories.

Comprehensive data was hard to aggregate, but the Canadian Centre for Home Education did mine provincial education databases to trace the growth of homeschooling before and after COVID-19, to the extent possible. Seven provinces (Alberta, BC, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, PEI, and New Brunswick), with just under 2 million of Canada’s 5.7 million school-aged children, provided reasonably reliable numbers under more-or-less restrictive regulations. The data do not include Ontario, Quebec, or Newfoundland and Labrador, where homeschool enrolment is based on estimates rather than hard numbers.

Out of the seven reporting provinces, the school-age population of children totaled 1,923,000 in 2019–20, the year before COVID. In 2019–20, 48,800 were reportedly being homeschooled, and that number spiked to 82,400 (a rise of 69 percent) during 2020–21, representing 4.3 percent of all school-aged children. Post-Covid (2021–22), this number slid to 72,700, or 3.8 percent of all school-aged children, significantly above the pre-pandemic numbers. While regulatory regimes vary, it is possible to estimate the retention rate. Out of the 33,600 families of children newly exposed to home education, the study estimates that some 23,900 or 71 percent, almost three-quarters, stuck with their plans to homeschool their children.

One province with a notable “COVID bounce” in home education was New Brunswick. Growth in that province’s anglophone homeschooling sector was quite dramatic from 2019 to 2020 (pre-COVID) and throughout 2020–21. Numbers of registered students rose from 902 (1.3 percent) to 2,322 students (3.3 percent) out of some 70,000 school-aged children. While homeschooling dipped post-COVID to 1,981 students (2.8 percent), it more than doubled during the pandemic disruptions. However, homeschool is far less popular in New Brunswick’s francophone sector; the numbers have swelled from thirty in 2019–20 to 271 in 2021–22, reaching 0.9 percent of the 29,800 kids in the francophone system, close to the pre-COVID national average across Canada. 66 66 P.W. Bennett, “Homeschooling Is Growing and Deserves More Attention,” Telegraph Journal, March 24, 2023, https://web.archive.org/web/20230604034256/https://tj.news/telegraph-journal/102084169.

One of the unique homeschool experiments that appeared was homeschooling collectives, dubbed “learning pods.” They sprouted up during the pandemic while schools were experiencing closures. “Parents (and sometimes educators) organized these mini schools at home or in a rented space, typically consisting of five students or fewer on site, or ten students or fewer in a distanced (virtual) pod.” 67 67 N. Boisvert, “Ontario Families Scramble to Set Up Private ‘Learning Pods’ as New School Year Draws Closer,” CBC News, August 20, 2020, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/learning-pods-challenges-risk-factors-1.5692551; P. MacPherson, “‘Learning Pods’ Prove that Governments Should Fund Students—Not Systems,” Fraser Institute, December 30, 2020, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/article/learning-pods-prove-that-governments-should-fund-students-not-systems. Some learning pods were short lived and disappeared when in-person school resumed in 2021–22.

The COVID-19 disruption did increase the popularity of home education. While many families new to homeschooling found it a significant burden, surprising numbers, in the seven provinces profiled in the Canadian Centre for Home Education’s 2022 study, continued on after the pandemic. Lingering “COVID anxieties” were a factor, according to Woodard, but one major motive was “dissatisfaction with the public school culture or the “progressive ideology” in the public schools.” 68 68 Woodard, “Growth in the Homeschooled Population.” Whether it lasts or not, many more parents have embraced the concept of homeschooling and gained practical experience guiding their children’s education.

The Implementation Gap: Learning Recovery and Its Challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic shock knocked out Canada’s provincial and territorial school systems and exposed hidden vulnerabilities. Speaking in January 2022 on TVO’s The Agenda, Western University education professor Prachi Srivastava was quite frank about the absence of anticipatory thinking and preparation: “We’ve just been shocked at the lack of planning, at the lack of forward planning in the face of what is quite a predictable outcome,” referring to the short- and long-term consequences of mass school closures. 69 69 N. Kiwanuka, “Return to Online Learning, Again,” The Agenda with Steve Paikin, January 6, 2022, https://www.tvo.org/transcript/2684838/return-to-online-learning-again.

Four mass school closings in Ontario cost K–12 students some twenty-eight weeks of schooling from March 2020 onward, roughly double the average lost time (fourteen to sixteen weeks) across all advanced industrial societies. 70 70 Gallagher-Mackay and Srivastava et al., “COVID-19 and Education Disruption in Ontario.” While Ontario led in weeks claimed by school closures, most other provinces were close behind, with Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, for example, checking in at twenty to twenty-two weeks of disrupted instructional time by June of 2021. 71 71 P.W. Bennett, “Righting the Education Ship: Learning from the Powerful Lessons of the Pandemic.” Macdonald-Laurier Institute, April 18, 2023, https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/righting-the-education-ship-learning-from-the-powerful-lessons-of-the-pandemic/. A follow-up report confirmed the cumulative learning loss and social harms inflicted since March 2020 and recommended that, barring catastrophic circumstances, schools should remain open for in-person learning for the foreseeable future. 72 72 M. Science et al, “School Operation for the 2021–2022 Academic Year in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, 2022, https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.39.1.0.

Three years after the pandemic shock, it is becoming clear that Canada’s provinces have been slow to recognize the learning loss and lag behind in producing educational-recovery plans. “Uncertainty around the pandemic,” an Equitable Learning research team discovered, made it very difficult for system leaders “to prepare and plan for the 2020–21 school year and beyond,” and the relative absence of student data hampered their efforts. 73 73 J. Rizk, R. Gorbet, J. Aurini, A. Stokes, and J. McLevey, “Canadian K–12 Schooling during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons and Reflections,” Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy 201 (2022): 90, 97–98, https://doi.org/10.7202/1095485ar.

A February 2022 pan-Canadian scan of K–12 COVID-related education plans conducted by Toronto-based People for Education produced spotty results. Only four of the provinces and territories, British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick, were then engaged (even in the 2021–22 school year) in any form of data collection, and it occurred irregularly at best. Only two of the provinces had adopted anything approaching a vision or plan to manage, assess, or respond to learning loss or the psychosocial impact of mass school closures, and none have allocated sufficient funding to prepare for post-pandemic recovery. 74 74 People for Education, “Pan-Canadian Tracker: Education Strategies in Response to COVID-19 (2021–2022),” February 3, 2022, https://peopleforeducation.ca/pan-canadian-tracker-education-strategies-in-response-to-covid-19-2021-2022/; C. Alphonso, “Provinces and Territories Urged to Put Forward an Education Recovery Plan,” Globe and Mail, February 3, 2022, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-new-report-calls-on-provinces-and-territories-to-put-forward-an/.

A near-total lack of baseline student data, according to Western University researcher Srivastava, seriously hampered our capacity to assess how the pandemic had affected student learning over the initial two years. She told CBC News that it was hard to fathom when Canada, as a G7 country (one of the world’s seven most highly industrialized and relatively well-resourced liberal democracies), possessed an extensive educational bureaucracy, and had, relatively speaking, one of the smallest cohorts of children, with some 5.7 million, in elementary and secondary school. 75 75 H. Rivers, “COVID-19 Pandemic Learning Loss Hard to Measure: Western Researcher,” London Free Press, December 3, 2021, https://lfpress.com/news/local-news/covid-19-pandemic-learning-loss-hard-to-measure-western-researcher; P. Srivastava on Fresh Air, “Surprise Learning Losses Mounting in Ontario Schools,” CBC Radio, 2021.

Suspending or curtailing system-wide student assessments compounded the problem. With Ontario’s Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) testing cancelled during the pandemic, there was no way to assess how that province’s 2 million students were performing or whether they were recovering. “My assessment,” Srivastava said, “is that we could have used the EQAO in a different way. We could have used it to monitor what the baseline was . . . then we could have rerun the EQAO.” 76 76 Rivers, “COVID-19 Pandemic Learning Loss Hard to Measure.”

The Ontario pattern was repeated elsewhere, as provinces, one after another, abandoned large-scale student assessments and suspended high-school examinations. Maintaining consistent and credible benchmark assessments would certainly have been preferable, leaving provincial and district authorities better prepared to plan for recovery. Some provinces, including Ontario and Nova Scotia, restored testing in 2021–22, but it is proving difficult to assess changes in performance because of the lack of consistent baseline data. 77 77 Education Quality and Accountability Office, “EQAO Releases First Provincial Assessment Results Since Before Pandemic,” October 22, 2022, https://www.eqao.com/about-eqao/media-room/news-release/2022-highlighted-provincial-results/; Nova Scotia Education and Early Childhood Development, “Results,” Government of Nova Scotia, https://plans.ednet.ns.ca/results.

School authorities struggled to find their way during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it proved costly for the pandemic generation of children. A child who was in kindergarten in March 2020 is now in grade 4. Students in grade 9 when COVID-19 hit will have completed most of their high-school years disrupted by closures and mostly ineffective online-learning experiments.

Repeated pivots to emergency home learning were detrimental to school-aged children and families, and education was used as a “pandemic control” instrument without sufficient recognition of the academic and social impacts on children and teens. Public policy devolved into complying with public-health dictates, and responding—in ad hoc, reactive fashion—to educator and parent concerns, applying band-aid upon band-aid, from social distancing, to bubble, to HEPA filter units, to secure a modicum of consent, several times, to restart in-person school. 78 78 M.K. Barbour et al., “Understanding Pandemic Pedagogy”; K. Gallagher-Mackay and C. Corso, “Taking Action to Limit Learning Impacts from the Pandemic,” Education Canada Magazine, spring 2022, https://www.edcan.ca/articles/taking-action-to-limit-learning-impacts-from-the-pandemic/.

Outright resistance to system-wide student testing and data collection hampered provincial efforts to produce educational-recovery plans. When Laurier University’s Centre for Leading Research in Education assembled a multi-stakeholder symposium in January 2022, the group of well-connected Ontario informants responded with the usual remedies, with one notable exception: a clear recognition of the critical need for educational data and evidence. While a few participants reverted back to calling for a “pause” on provincial testing, there was, for the first time, a recognition that student assessment provides the basis for developing education-recovery plans and a proven means for targeting resources at the school level. 79 79 K. Gallagher-Mackay and S. Sider, “Educational Recovery and Reimagining in the Wake of COVID-19.”

Learning loss while students were out of school affected students right across Canada, at all grade levels. Given their centralized management, bureaucratic structure, labour-contract issues, and the sheer diversity of the student population, public schools struggled throughout the worst of the pandemic. Smaller and more autonomous schools, such as those affiliated with recognized independent-school associations, outperformed their public-school counterparts. Far fewer days were lost in private and independent schools in the initial start-up and during the interruptions, and students received far more teacher instruction and daily teacher interactions. Leakage from public schools to homeschooling was significant, as the homeschool population nearly doubled before stabilizing at above-pandemic levels when in-person schooling returned in public systems during 2021–2022. 80 80 K. Onstad, “The Miserable Truth About Online School,” Toronto Life, February 18, 2021, https://torontolife.com/city/the-miserable-truth-about-online-school/; D. Van Pelt, “Some Schools Thrived during the COVID-19 Crisis. What Can They Teach Us?,” The Hub, June 16, 2021, https://thehub.ca/2021-06-16/deani-van-pelt-some-schools-thrived-during-the-covid-19-crisis-what-can-they-teach-us/; P. MacPherson, “Student Enrolment in Canada, Part 3: More Families Choosing to Homeschool,” Fraser Institute, March 2, 2022, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/blogs/student-enrolment-in-canada-part-3-more-families-choosing-to-homeschool.

Canadian education researchers are now coming to terms with the realities of learning loss. Lead Royal Society of Canada researcher Tracy Vaillancourt and two Ontario scholars Scott Davies and Janice Aurini are taking a second look at the pandemic impact using evidence gathered from the most credible learning-loss forecast studies. Building on earlier work assessing the so-called summer slide, they project that average students likely experienced a three-month shortfall due to COVID-19 school closures, and students in the lower socioeconomic range may be behind by as much as six-and-a-half months. That would be consistent with the statistical projections of a November 2020 American study and an April 2021 Dutch study, which concluded that “students made little or no progress while learning from home.” Once again, the learning loss was most evident for students from disadvantaged homes. 81 81 Vaillancourt, Davies, and Aurini, “Learning Loss While Out of School”; M. Kuhfeld et al., “Learning during COVID-19: Initial Findings on Students’ Reading and Math Achievement and Growth,” NWEA, November 2020, https://www.nwea.org/research/publication/learning-during-covid-19-initial-findings-on-students-reading-and-math-achievement-and-growth/; P. Engzell, A. Frey, and M.D. Verhagen, “Learning Loss Due to School Closures during the COVID-19 Pandemic,” PNAS 118, no. 17 (2021): 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118.

Recognizing the problem is the first step, but actually tackling learning recovery is proving to be a formidable challenge. Three immediate responses were proposed by leading research authorities, strongly supported by McKinsey consultants: revamp the entire K–12 curriculum to facilitate students catching up, focus on the core competencies of reading and literacy as well as pro-social skills, and initiate targeted interventions, including intensive tutoring and summer catch-up sessions. 82 82 Dorn, Hancock, Sarakatsannis, and Viruleg, “COVID-19 and Learning Loss,” 9–16; P. Srivastava, “Considerations for School Reopening in Ontario: Building a More Resilient Education System for Recovery,” Western University, June 2020, https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/edupub/173/.

Many of the vital lessons will come from tapping into research and strategies from elsewhere. A “crisis-sensitive approach” for pandemic educational-policy planning and recovery, according to Prachi Srivastava and international education-development researchers, will involve four key considerations:

(i) managing a crisis and instituting first responses; (ii) planning for (interrupted) reopening with appropriate measures; (iii) sustained crisis-sensitive planning with considerations for assessing risks for the most vulnerable; (iv) adjusting existing policies and strengthening policy dialogue. . . Collective planning exercises with cross-sectoral collaboration and community engagement from marginalised groups should be a sustained part of [pandemic-recovery] planning exercises. 83 83 P. Srivastava et al., “Education Recovery for Stronger Collective Futures,” T20 Indonesia 2022, 2022, 11, https://www.t20indonesia.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/TF5_Education-recovery-for-stronger-collective-futures.pdf.

Post-pandemic recovery plans have encountered stiff resistance, mostly at the regional district and school level. Winning support is an uphill battle because, as Vaillancourt, Davies, and Aurini put it, teachers were “burned out” and students were “keen to return to the pre-pandemic status quo, a routine that does not include summer learning.” 84 84 Vaillancourt, Davies, and Aurini, “Learning Loss While Out of School.” While it is next to impossible to get a progress report on Canadian academic-recovery initiatives, American states, school districts, and research institutes are more forthcoming with preliminary assessments.

The latest NWEA report, “Education’s Long COVID,” based upon data from 6.7 million US students, shows that billions of dollars in federal aid invested in tutoring and catch-up interventions have not closed the gap, particularly in mathematics. Pandemic recovery has reportedly stalled for most of America’s 50 million students, and based upon NWEA data analysis, upper elementary and middle school students may actually have lost ground in 2022–23. Student behaviour, academic and staffing challenges, including post-pandemic chronic absenteeism, are cited as likely reasons students are still lagging and the gaps still exist. 85 85 K. Lewis and M. Kuhfeld, “Education’s Long COVID: 2022–23 Achievement Data Reveal Stalled Progress toward Pandemic Recovery,” Center for School and Student Progress, July 2023, https://www.nwea.org/uploads/Educations-long-covid-2022-23-achievement-data-reveal-stalled-progress-toward-pandemic-recovery_NWEA_Research-brief.pdf. For a visual depiction of the months required to catch-up to pre-COVID status quo, see figure 3 of this study.

Two American studies, released in August 2023, focused on learning-recovery strategies and demonstrated that getting implementation right is a formidable challenge. One Calder Center working paper, examining 2022 summer-school programs across eight districts and serving 400,000 students, found that the programs had a small but positive effect on student math scores but little effect on reading. A second paper, from researchers at Vanderbilt University and Stanford University, examined intensive tutoring programs and identified some critical success factors. Like any initiative, academic-recovery strategies required effective program management as well as sustained and coordinated effort to exert much of an impact in closing the learning gaps. Up to one-third of schools did not have the capacity or resources and could not spare the time to provide high-dosage tutoring to students who needed help to close the gaps. 86 86 S. Schwartz, “What Two New Studies Reveal about Learning Recovery,” Education Week, August 10, 2023, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/what-two-new-studies-reveal-about-learning-recovery/2023/08.

Scattered and mostly anecdotal evidence suggests that Canada’s highly variable and disaggregated provincial recovery plans initiated in 2021–22 may well have suffered the same fate. Since a 2010 McKinsey study, Ontario had laid claim to being one of the “world’s leading school systems.” 87 87 M. Barber, C. Chijioke, and M. Mourshed, “How the World’s Most Improved School Systems Keep Getting Better,” McKinsey & Company, November 1, 2010, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/how-the-worlds-most-improved-school-systems-keep-getting-better; P.W. Bennett, “Ontario’s ‘Leading School System’ Mirage,” National Post, July 10, 2015, https://nationalpost.com/opinion/paul-bennett-ontarios-leading-school-system-mirage. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, provincial student-achievement levels in grades 3 and 6 are down in Ontario, as in every province and territory. On the 2021–22 Ontario student tests, students declined more in literacy but have remained stable in mathematics, relative to those from 2018–19. In the 2021 PIRLS assessment (the definitive mathematics assessment used around the globe), grade 4 and 5 students slipped, and two provinces (Ontario and New Brunswick) were so destabilized by disruptions that they were unable to conduct the mathematics tests. 88 88 See Education Quality and Accountability Office, “School, Board and Provincial Results,” https://www.eqao.com/results/; International Education Association, “PIRLS 2021 International Results in Reading,” TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, https://pirls2021.org/results.

One of the few publicly accessible pandemic-recovery plans, that of the Toronto District School Board, focused more on fostering “joy, engagement and belonging within the classroom.” Some 40 percent of grade 1 students in 2021–22 from “low-income households” were at risk of not meeting grade-level reading benchmarks, up from 27 percent in 2012–13. Declining percentages of students from grade 4 to 9 were attaining at minimum satisfactory grades (B-) in mathematics and science, with significant disparities among students from various racial groups. While “learning loss” was downplayed in the TDSB report, the declines were more pronounced among students from lower-income and racial minority households. 89 89 Toronto District School Board, “COVID-19 Pandemic Recovery Plan Update: October 2022,” October 2022, 4–5, https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/docs/Update_%20October%202022.pdf.

Conclusion: Long COVID and the Pandemic Generation

Education’s “long COVID” threatens Canada’s international reputation for having one of the world’s best school systems. Public-health directives shutting down schools, and lapses in post-pandemic planning and recovery efforts, have delivered setbacks, most clearly reflected in the latest round of international, national, and provincial student assessments. 90 90 See International Education Association, “PIRLS 2021 International Results in Reading.” That’s of broader public concern because the quality of education is critical to our nation’s productivity, health, adaptability, and innovation, and to the resilience required to thrive in our competitive global society. 91 91 E.A. Hanushek and L. Woessmann, “The Economic Impacts of Learning Losses,” Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, September 10, 2020, https://www.oecd.org/education/the-economic-impacts-of-learning-losses-21908d74-en.htm; World Bank, “The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update,” June 23, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/education/publication/state-of-global-learning-poverty.