Table of Contents

Table of Contents

Key Points

- Alberta has a plural education model, offering what is perhaps the most diverse approach to K–12 schooling in Canada. Despite the pluralism that exists across Alberta’s fully taxpayer-funded schools, some families still choose to send their children to independent schools.

- This paper applies a typology of independent schools, developed in previous Cardus research, to identify the types of independent schools that exist in Alberta, and the number of schools and enrolment in each type.

- While the enrolment growth in the independent school sector is outpacing the enrolment growth in the province as a whole, only one net new independent school has been created in Alberta since 2013–14. Data suggests that growth in enrolment is due to existing schools becoming larger and more students enrolling as supervised home education or shared-responsibility students. That said, growth has not translated to an increase in pluralism understood as additional school choices and options.

- “Elite” schools are uncommon in the sector. Alberta independent schools tend to be small community-oriented schools: Seventy-five percent of all independent schools in the province enrol fewer than 300 students, and most of these are Religious and Special Emphasis schools.

- Three-quarters of independent schools belong to a school association. Membership within school associations provides an additional layer of accountability beyond that of government regulation, and contributes to robust expressions of educational pluralism.

- The Alberta government should continue to encourage the presence of meaningful pluralism by supporting new and existing independent schools that meet requirements, so that families have access to options that best fit their education needs.

Introduction

Alberta has a plural education model, offering what is perhaps the most diverse approach to K–12 schooling in Canada. 1 1 A. von Heyking, “Alberta, Canada: How Curriculum and Assessments Work in a Plural School System,” Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, June 2019, http://jhir.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/62962; A. Berner, “Good Schools, Good Citizens: Do Independent Schools Contribute to Civic Formation?,” Cardus, June 2021, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/good-schools-good-citizens/. Across the landscape of fully taxpayer-funded schools, there are district (public) schools, constitutionally protected separate (e.g. Catholic) schools, constitutionally protected Francophone schools, and schools run by First Nations on reserves, among others. Within the district, separate, and Francophone systems, there are schools with particular pedagogical or religious programs, known as alternative schools. In addition, Alberta is the sole jurisdiction in Canada that has charter schools.

Beyond these fully taxpayer-funded options, a variety of independent schools also exist. The enrolment growth in the independent sector is outpacing the enrolment growth in the province as a whole. This paper applies a typology of independent schools, developed in previous Cardus research that is focused on schools in Ontario, to identify the types of independent schools that exist in Alberta, and the number of schools and enrolment in each type. 2 2 D. Hunt, J. DeJong VanHof, and J. Los, “Naturally Diverse: The Landscape of Independent Schools in Ontario,” Cardus, 2022, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/naturally-diverse-the-landscape-of-independent-schools-in-ontario/. In addition, the paper examines the schools’ geographic distribution, how they deliver the education, and other key factors that define Alberta’s independent school landscape.

Research Method

Replicating the earlier Cardus study, a framework-analysis methodology was used to design and apply a typology of schools. Although typically used in the field of health care, this methodology has been used in education research and for assessing website content. It involves a five-stage process: familiarization, thematic-framework identification, indexing, charting, and mapping and interpretation. The process is both a logical and intuitive one, involving judgements about meaning. 3 3 J. Ritchie and L. Spencer, “Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research,” in Analyzing Qualitative Data, ed. A. Bryman and R.G. Burgess (London: Routledge, 1994), 173–94, as cited in A. Srivastava and S.B. Thomson, “Framework Analysis: A Qualitative Methodology for Applied Policy Research,” Journal of Administration and Governance 4, no. 2 (2009): 72–79, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14078/730.

The researchers used the most recent list of schools available at the time of writing (June 27, 2023) from Alberta Education’s schools and school authority information reports, along with the most recent enrolment data (October 31, 2022). 4 4 Alberta Education, “School and Authority Information Reports,” Government of Alberta, June 2023, https://education.alberta.ca/alberta-education/school-authority-index/everyone/school-authority-information-reports/; Alberta Education, “School and Authority Student Population Data,” Government of Alberta, accessed October 2022, https://www.alberta.ca/assets/documents/educ-school-enrolment-data-2022-2023.xlsx In the second step, the researchers began identifying and coding for emerging themes, based on information about the schools that was included in the school and school authority information reports. A provisional set of themes and definitions were already in existence from the earlier study, which was used as the starting point for the indexing step of visiting school websites, social-media profiles, publicly accessible school-association membership listings, and performing other search-engine queries to further develop, refine, and test categories and assign schools to them. School addresses were entered into Google Maps (or equivalent) to identify a school’s location and confirm its existence. For most of the 221 independent schools in the school and school authority information reports, this process provided sufficient information for the purposes. For twenty-one listings for which no information was available online, the street-address search was the only source of data outside of the entry in the report. Of these, the researchers could confidently identify twenty as parochial or Mennonite schools, but could not make a judgement on one school and therefore typed it as Unclassified.

Prior to the third step, indexing, the researchers agreed on a provisional revised set of categories and definitions specific to the Alberta context. Indexing was then done by each researcher working and coding independently. At stage four, charting, the researchers went back through each type, debating its relevance, attributes, and alignment with the literature, with the goal of seeking intercoder agreement (that is, each coder assigning the same codes to the same items), to gauge and help strengthen the reliability of the typing and coding. The intent was to achieve definitions that are precise and objective enough to be replicable but also flexible enough to capture the diversity of the sector and the uniqueness of individual schools. This fourth stage was done collaboratively, performing data analysis on each type and subtype, and on each school that was assigned multiple types. Where the researchers disagreed, the typology was refined until its coding application resulted in agreement at least 95 percent of the time. For the remaining few schools, the lead author made the final decision.

After coding for the entire data set, the last step was mapping and interpretation. At this stage, the final draft of the typology was written. The schools were then aggregated according to the final set of types and subtypes and the researchers performed data analysis through frequency reporting and cross-tabulation. Crosstab analyses were performed in selected instances to better understand the characteristics and distribution of schools in the sector, such as comparison of school type by school size.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is its reliance on schools’ self-reported information, presented in Alberta Education’s school and school authority information reports and on school websites, social media, and elsewhere. These latter media serve an important marketing purpose and, to that end, may express a school’s goals and aspirations more than its current reality or may otherwise misrepresent important elements. The researchers sought to mitigate this limitation in four ways. (1) The framework-analysis approach ensured multiple touchpoints and perspectives of the data. (2) The types and subtypes were written to be as specific and objective as possible. (3) The researchers sought to identify not merely surface characteristics but the underlying evidence for placement in the various types and subtypes (this required deep familiarity with the sector). And (4) the interpretive data analysis was controlled through intercoder reliability, feedback, and subsequent adjustment.

A second limitation is that in visiting each school’s website and other online assets, the researchers relied on what accumulates to hundreds of data sources. It is possible that the researchers missed some features of some schools or miscategorized some schools purely due to researcher error.

Typology

Defining Independent Schools

For the purpose of this study, an independent school in Alberta is—to use the government’s terminology—a private school that is accredited funded, accredited non-funded, or registered. The meaning of these three terms is explained further below. Independent schools are governed by Alberta’s Education Act and Private Schools Regulation. 5 5 Education Act, SA 2012, c E-0.3, https://open.alberta.ca/publications/e00p3; Private Schools Regulation, Alta Reg 127/2022, https://www.alberta.ca/education-guide-regulations.

Following Allison, Hasan, and Van Pelt, this research views independent schools as distinct from other kinds of schools in four fundamental ways. 6 6 D.J. Allison, S. Hasan, and D. Van Pelt. “A Diverse Landscape: Independent Schools in Canada,” Fraser Institute, June 2016, https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/a-diverse-landscape-independent-schools-in-canada.

- Ownership and Operation. In Alberta, all independent schools are owned and operated independently of the government.

- Financing. Independent schools in Alberta are typically non-profit charities. Partial taxpayer funding is available to accredited funded schools, to be used for operating expenses only. Capital expenses, such as buildings and equipment, must be met entirely through tuition or donations.

- Governance. Whereas district schools have publicly elected or appointed boards, independent schools are governed by boards that are accountable to the schools’ parents, donors, and others in its specific community of support.

- Purpose. District schools exist to provide an education that meets the needs of the province’s population as a whole. Within this population, however, some parents and their children have needs or desires that the universal system does not or cannot meet. Most independent schools therefore provide a more targeted school experience. They offer a particular pedagogy or curriculum, integrate the education with a particular religious identity, or serve a particular type of student.

The sources of school-count data and enrolment data used in this study do not indicate the designation of accredited funded, accredited non-funded, and registered. A Freedom of Information request provided the researchers with the school counts and enrolment counts of the three types of schools for the 2021–22 school year. These counts are given in the following paragraphs in order to reveal the general distribution across the three types. These counts are not used elsewhere in this report as they did not allow for analysis across type or subtype.

The majority of independent schools in the province are accredited funded, with 129 schools (77.7 percent of the independent school sector) in this category, and 36,857 students (98.0 percent of the independent school sector’s reported enrolment). 7 7 Some schools do not report enrolment. To be eligible for funding, accredited funded schools must have been in operation for at least one year, employ provincially certificated teachers, use the government curriculum, and have a certificated principal, among other requirements. They must be registered as a non-profit or be incorporated under the Societies Act, which has specific governance and fiscal requirements. Parents’ participation in the school’s governance must be ensured through positions on an operating board or advisory council.

Based on counts from the 2021–22 school year, thirteen independent schools (7.8 percent of the independent school sector) are accredited non-funded, with 459 students (1.2 percent of the sector’s reported enrolment). They do not receive any taxpayer funding. They are not required to use the government curriculum, and their principals do not need certification, but they must employ provincially certificated teachers. 8 8 Alberta Education, “Establishing an Independent (Private) School: Application Process and Requirements,” Government of Alberta, March 2024, https://open.alberta.ca/publications/establishing-an-independent-private-school-application-process-and-requirements.

There are twenty-four (14.5 percent of the sector) registered schools, with 281 students (0.7 percent of the sector’s reported enrolment). These schools do not receive any taxpayer funding and are not authorized to grant credit for senior-high school courses.

Within the accredited funded and accredited non-funded categories, Alberta Education recognizes several further categories: heritage-language schools, early childhood services (ECS) private operators, and designated special education schools.

The present report excludes heritage language schools from all school-count data and enrolment data. Heritage-language schools are accredited funded or accredited non-funded schools that operate outside of regular school hours and provide language and culture courses only. Students enrolled in them are also enrolled in another school for courses in other subjects.

The present report also excludes ECS private operators from all school-count data and enrolment data. Note, however, that some ECS private operators offer kindergarten and grade 1 in addition to pre-school programs. These students are excluded from the enrolment counts reported in this study, because the researchers did not have a way of disaggregating them from the pre-school enrolments. Further, some K–12 independent schools also offer early childhood education. These ECS students are included in the enrolment counts because the researchers did not have a way of disaggregating them from the K–12 enrolments.

The present report includes designated special-education schools in all school-count data and enrolment data. These are accredited funded schools that serve mostly or entirely students with disabilities, and receive additional funding from Alberta Education in support of student needs.

Data on homeschooling is excluded from this study, but it is important to note that Alberta Education recognizes forms of homeschooling in which the student has some involvement with a school (“supervised home education” and “shared responsibility” programs). These students are presumably included in the schools’ enrolment numbers. The researchers did not have a way of disaggregating these students from the data.

School Types

This study uses the typology created for the previous Cardus research on the independent school landscape in Ontario. 9 9 See the discussion of the typology in Hunt, DeJong VanHof, Los, “Naturally Diverse,” 13–14. All schools listed in Alberta’s school and school authority information reports were assigned to distinct types that the researchers believed best described the school’s nature and purpose. Information concerning nature and purpose was collected from each school’s website, from any description provided by a school association to which it belonged, and from other reports and descriptions discovered through web searches. Most of the pertinent information was collected from the website sections titled “Home,” “About,” “Mission,” or similar.

For the large majority, the school type was readily evident. For some, more than one type was identified (as a hypothetical example, Islamic Montessori). These multi-type schools were assigned a primary type and a secondary type. No school was identified as having a tertiary type (unlike in the Ontario study). The schools’ primary purpose was usually readily evident, but in a very small minority of instances, judgment calls were ultimately made. For example, is the purpose of a hypothetical Islamic Montessori school to provide an Islamic education via the Montessori method, or is it a Montessori school that incorporates the Islamic faith (or some aspect of the Islamic religion or culture)? The former would be coded as Religious (primary type), Islamic (subtype), as well as Special Emphasis (secondary type), Montessori (subtype). The latter would be coded as Special Emphasis (primary type), Montessori (subtype), as well as Religious (secondary type), Islamic (subtype). In each instance, such judgements took considerable investigation, but using the school’s own mission statement, vision statement, core values statement, program and course offerings, history, and other purpose-identifying factors, the researchers attempted to make such distinctions.

Unless otherwise indicated below, the resulting typology is identical to that used in the previous Ontario study.

1. Religious

A religious independent school is defined as one having a primarily religious identity, purpose, or formal affiliation that is clearly stated or emphasized in the school’s mission statement, name, or in the About, Educational Philosophy, or similar section of the school’s website.

If the school described itself as having a religious connection, founding, or heritage but did not meet the criteria of the paragraph above, it was assigned another type as its primary type, and Religious was assigned as its secondary type.

2. Special Emphasis

Special Emphasis type is defined as a school that serves a specific student population (such as special needs), offers a particular curricular emphasis (such as music), or operates with a distinct educational philosophy or pedagogical approach (such as Waldorf). The special emphasis is clearly stated or emphasized in the school’s mission statement, name, or in the About, Educational Philosophy, or similar section of the school’s website. The special emphasis is not an optional track or appendage to the school’s overall identity but appears to be a core purpose for the school’s existence.

If a special emphasis was judged to exist, but not as the school’s primary purpose or identity, another type was assigned as primary, and Special Emphasis as secondary.

3. Top Tier

Top Tier is the name chosen for those schools that are commonly thought of as “elite,” with competitive admissions policies, high academic standards, excellent facilities, and tuition rates that are significantly higher than that typically found in other independent school types. Although the researchers believe that the “top” school for each student is the one that is the best fit for them, the term Top Tier is used for this type as a better descriptor than “elite.”

In the earlier Ontario-based research, membership in one of five independent school associations that are generally viewed as the most prestigious was used as a proxy for inclusion in this type. However, the analysis of Alberta generated very few schools that maintain these memberships. Thus, in this study, Top Tier type was applied, at the researchers’ discretion, to schools whose admissions, academic standards, facilities, and tuition rates are as described in the previous paragraph.

4. Preparatory

Preparatory type are those schools that operate conventional models of schooling but whose primary identity is not Religious, Special Emphasis, Top Tier, or Credit Emphasis. Although “preparatory” language on the school’s website was not a requirement in the coding process, this term is used because all of these schools presented themselves as university preparatory schools. They emphasize academics, preparation for university, or university placement. The researchers recognize that many of the schools placed in these four other categories may be emphasizing and preparing their students for post-secondary education to the same or even greater degree, but a category was needed for preparatory schools that are neither Top Tier nor Credit Emphasis. These schools typically operate in more modest facilities than the typical district schools, but they seek to attract students by the quality of instruction.

5. Credit Emphasis

In the earlier Ontario-based research, Credit Emphasis were typed as those schools that emphasize offering courses or credits toward the Ontario Secondary School Diploma (OSSD) in such a way or to such an extent that this was judged to be the school’s primary purpose or identity. The acquisition of credits toward the OSSD was clearly emphasized on the school’s home page, About, Purpose, or similar section of the school’s website. It was observed that these schools also tended to charge their fees on a by-the-credit basis and focus their recruitment on international students.

Given operators’ low bar to entry into the independent school sector in Ontario, there were numerous such schools in Ontario. There are few such schools in Alberta, likely due to the stricter regulations in this province. However, this type was maintained and its definition was adjusted for the Alberta context. In this study, Credit Emphasis is defined as those schools that exist to market an Alberta high school diploma, either on a by-the-credit basis, or primarily to international students, or both. Note that these are distinct from schools that specialize in providing an internationally based or global curriculum (which is a subtype of Special Emphasis).

6. Other

Other type was maintained for those schools for which information could be obtained beyond their listing in the school and authority information reports, but that exist for a purpose other than the six purposes described above. Although there were such schools in Ontario, no Alberta independent schools matched this type.

7. Unclassified

Unclassified type was used for one school listed in the reports but for which the researchers could not obtain any or enough information to place within another type.

8. Auxiliary

Auxiliary type was assigned to twenty-four entries in the Reports that did not fit the definition of independent school used in this research. Most of them are school-adjacent programs. Examples include tutoring services, after-school programs, daycares, summer camps, adult education, and heritage-language schools. If a school’s website revealed that courses in a heritage language were offered only on Saturdays, the researchers deemed it to be a heritage-language school. The researchers could not be certain that all heritage-language schools were typed as Auxiliary, however, because Alberta Education does not provide a list of schools with this designation.

Subtypes

Within the Religious and Special Emphasis types, further categorization illuminated a variety of subtypes within them.

Religious Subtypes

- Adventist (Christian). A self-identified or formal association with the Seventh-day Adventist tradition of the Christian faith.

- Alliance (Christian). A self-identified or formal association with the Christian and Missionary Alliance tradition of the Christian faith.

- Islamic. A self-identified or formal association with the Islamic faith.

- Jewish. A self-identified or formal association with the Jewish faith.

- Mennonite (Christian) and/or Parochial. Parochial and/or an identity or formal association with the Mennonite, Orthodox Mennonite, Old Colony Christian, Amish, or a similar tradition within the Christian faith. Note that it is possible that a given parochial independent school is not religious. Given limited available information, and since almost all parochial schools were identified as some form of Christian, all parochial independent schools were merged into this subtype with the various Mennonite traditions.

- Non-denominational Christian. Self-identified with the Christian faith but without reference to any particular denomination, diocese, or sect. The great majority of these schools are evangelical, and many are members of the Association of Christian Schools International or the Koinonia Christian Education Society.

- Reformed (Christian). A self-identified or formal association with the Reformed tradition of the Christian faith.

- Roman Catholic. A self-identified or formal association with the Roman Catholic Church.

- Other Christian. A self-identified or formal association with a particular denomination, diocese, or sect not included above, within the Christian faith (such as Baptist, Brethren, Lutheran).

- Sikh. A self-identified or formal association with the Sikh faith. (In the Ontario study, Sikh schools were included under Other Religion.)

- Other Religion. A self-identified or formal association with a religion or faith tradition that is not included above (such as Hindu, Bahá’í, interfaith).

Special Emphasis Subtypes

Initially, two dozen special emphases were identified. They were then reduced to a smaller set: subtypes that had fewer than four schools were combined into one subtype (Arts, Sports, and STEM) or were coded as Other Special Emphasis. 10 10 The subtypes used in the previous Ontario study that did not meet the four-school threshold in Alberta and were placed in Other Special Emphasis are Boys/Girls, First Nation, Holistic, Micro School, Nature, Reggio Emilia, and Waldorf. The Ontario study also grouped Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate schools together. In this Alberta study, Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate are two subtypes, since the researchers judged these to be different pedagogical and philosophical approaches to education that should remain distinct types. Although the intent was to define the subtypes in such a way that any given school fit only one, some schools are genuinely multi-emphasis and thus fall under more than one subtype (for example, a French Montessori school). The resulting thirteen subtypes are presented below, with reference to the literature used to develop this framework.

In some cases, a Special Emphasis school was judged to belong in more than one subtype equally. Consider the hypothetical case of an all-boys hockey-emphasis school. Would this school be best typed as Sports or as Boys-Only? How about a Distributed-Learning Nature school? These questions could likely be resolved by interviewing principals, for example, but this was beyond the study’s methodological scope. In all, multiple Special Emphasis subtypes were coded for eighteen Special Emphasis schools.

- Advanced Placement (AP). These schools offer university-level courses through the Advanced Placement program, which is governed by the College Board. Advanced Placement programs offer a head start and increased access to American post-secondary institutions. 11 11 College Board, “AP Program,” https://ap.collegeboard.org/.

- Arts, Sports, or STEM. The Ontario study reported three distinct subtypes here, but since each of these groups had fewer than four schools, following Allison, Hasan, and Van Pelt they were collapsing into one subtype. 12 12 Allison, Hasan, and Van Pelt, “A Diverse Landscape.” Arts schools offer a fine-arts emphasis. 13 13 C.J. Stufft, “Reading to the Rhythm: Integrating Music into Literacy Instruction,” English in Texas 45, no. 1 (2015): 21–26; K. Walker, “Fine Arts Education,” Education Partnerships, January 3, 2006, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED537918.pdf. Sports schools emphasize sports, physical education, or athletic development. Sports schools are not also counted as Individualized or Experiential Learning. 14 14 M.A.F. Lounsbery and T.L. McKenzie, “Physically Literate and Physically Educated: A Rose by Any Other Name?,” Journal of Sport and Health Science 4, no. 2 (2015): 139–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2015.02.002. STEM schools emphasize science, technology, engineering, and math. Typically, STEM education is directly linked to career preparation and the development of a workforce that is scientifically and technologically literate. It is rooted in a philosophy that places a high value on the ability of science and technology to solve complex, global problems. 15 15 National Research Council, Successful STEM Education: A Workshop Summary (Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011), https://doi.org/10.17226/13230.

- Classical. Rooted in the classical liberal arts tradition, these schools focus on the habits of thought through what Dorothy Sayers called “the lost tools of learning,” the trivium (grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric) and quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music), or an interdisciplinary study of the great books (the “classics”) through the ages. Latin is typically offered as a core element of the curriculum. 16 16 D.L. Sayers, “The Lost Tools of Learning,” Hibbert Journal: A Quarterly Review of Religion, Theology, and Philosophy 46 (1948); K.W. Clark and R.S. Jain, The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Philosophy of Christian Classical Education (Camp Hill, PA: Classical Academic Press, 2013); S.W. Bauer, “What Is Classical Education?,” Well-Trained Mind, June 3, 2009, https://welltrainedmind.com/a/classical-education/.

- Distributed Learning. These schools offer a non-traditional model of education delivery, such as homeschool partnerships, a hybrid of blended online and in-person offerings, distance learning, or a primarily remote- or home-based learning that is still connected to a teacher and school community. It is likely that distributed-learning schools enrol homeschool students in supervised home education and shared-responsibility programs. 17 17 D.L. Stirling, “Distributed Learning Environments,” December 8, 1997, http://www.stirlinglaw.com/deborah/DLE.htm; J.A. Converso, S.P. Schaffer, and I.J. Guerra, “Distributed Learning Environment: Major Functions, Implementation, and Continuous Improvement,” Learning Systems Institute, Florida State University, October 1999, 17.

- Experiential Learning. These schools adopt a philosophy of education that roots learning within experience, contrasted with traditional models that emphasize concepts and memorization. It focuses on exploratory, play-based, and/or place-based learning, and posits that children benefit from kinesthetic development. In upper elementary and secondary schools, experiential learning can include co-op placements, real-world business and research applications in project-based learning, or travel experiences. This subtype was applied only when other experiential emphases do not apply. For example, it was not applied for Montessori, Waldorf, Nature, Sports, or Arts schools. 18 18 J.S. Coker et al., “Impacts of Experiential Learning Depth and Breadth on Student Outcomes,” Journal of Experiential Education 40, no. 1 (2017): 5–23, https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825916678265; P. Hernández-Ramos and S. De La Paz, “Learning History in Middle School by Designing Multimedia in a Project-Based Learning Experience,” Journal of Research on Technology in Education 42, no. 2 (2009): 151–73, https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2009.10782545; H.A. Hadim and S.K. Esche, “Enhancing the Engineering Curriculum through Project-Based Learning” (paper presented at the 32nd Annual Frontiers in Education Conference, Boston, MA: IEEE, November 6–9, 2002), https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2002.1158200.

- International Baccalaureate (IB). These schools are accredited for one or more of the IB programmes: Primary Years, Middle Years, Diploma, or Career-related. 19 19 International Baccalaureate, “International Education,” https://www.ibo.org/. IB world schools offer internationally recognized academic programs that promote cultural awareness, second-language learning, critical thinking, and global problem solving. If a school was identified as IB-accredited on the association’s website, it was coded both as a Special Emphasis type and as affiliated with a school association. 20 20 International Baccalaureate, “Find an IB School,” https://www.ibo.org/programmes/find-an-ib-school/. If a school self-reported an IB-integrated curriculum but was not listed as accredited on the association’s website, it was included under the Special Emphasis type only. It is important to note that this subtype includes schools that offer IB as their only program of study and schools that offer it as one of their programs. This is one of the judgment calls made in order to reduce the overall number of subtypes.

- Individualized. These schools adhere to a philosophy of personalized education, in which they tailor learning experiences to each student’s needs. They typically develop differentiated learning plans and provide students the opportunity to make personal decisions about their learning. Specific curricular approaches can include Universal Design for Learning, digital management of learning, and others. Most if not all Special Education schools also fit the definition of Individualized, as do some Other Special Emphasis schools. Those subtypes are excluded from the Individualized count. 21 21 S. Patrick, K. Kennedy, and A. Powell, “Mean What You Say: Defining and Integrating Personalized, Blended and Competency Education,” International Association for K–12 Online Learning, 2013, 37, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED561301.pdf; J.D. Basham et al., “An Operationalized Understanding of Personalized Learning,” Journal of Special Education Technology 31, no. 3 (2016): 126–36, https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643416660835.

- International. This subtype includes schools with either an international or a global emphasis, and excludes IB and AP schools. International schools are defined primarily in terms of student body and target audience (i.e., enrolling non-domestic students). These schools’ websites typically refer to visa requirements and have portions of their site in a language other than English. Global schools “[aim] to empower learners of all ages to assume active roles, both locally and globally, in building more peaceful, tolerant, inclusive, and secure societies.” 22 22 UNESCO, “What Is Global Citizenship Education?” January 9, 2018, https://en.unesco.org/themes/gced/definition. Global schools may provide a globally focused curriculum, and their mission often specifies ideas of “global citizenship” or “world school.” 23 23 E. Moizumi, “Examining Two Elementary-Intermediate Teachers’ Understandings and Pedagogical Practices About Global Citizenship Education,” Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, 2010, https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=MR72914&op=pdf&app=Library&oclc_number=1019483268; J. Duarte and C. Robinson-Jones, “Bridging Theory and Practice: Conceptualisations of Global Citizenship Education in Dutch Secondary Education,” Globalisation, Societies and Education (March 6, 2022): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2022.2048800. Many independent schools have an international or student-exchange program, and many recruit international students, but the International special emphasis was applied only if the global focus or international student body was a core emphasis.

- Language/Culture. This subtype encompasses language- or culture-immersion (for example, Ukrainian), French-only, and bilingual education. Bilingual schools provide dual-language learning, either offering curriculum taught in two languages (e.g., in a 50-50 ratio) or through immersion in a second language. Alberta has one French independent school, governed by the Agency for French Education Abroad, under France’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 24 24 R.L. Oxford and C. Gkonou, “Interwoven: Culture, Language, and Learning Strategies,” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 8, no. 2 (2018): 403–26, https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.2.10.

- Montessori. Rooted in the pedagogy of Maria Montessori, these schools offer an individualized approach to education that encourages children’s innate creativity and curiosity. Typically, Montessori schools focus on early and/or elementary education. While accredited Montessori schools complete a rigorous accreditation process with an accrediting body (for example, the Canadian Council of Montessori Administrators), other schools may self-identify as Montessori without formal accreditation. Schools categorized as Montessori consist of both accredited and self-identified Montessori schools. 25 25 Canadian Council of Montessori Administrators, “CCMA Schools,” https://www.ccma.ca/ccma-schools/.

- Self-Directed Learning. This is a pedagogical approach that centres the student as the primary author of their learning. It involves learning at one’s own pace and emphasizes the use of technology in learning, with educators providing supervisory or tutoring support. 26 26 T. Timothy et al., “The Self-Directed Learning with Technology Scale (SDLTS) for Young Students: An Initial Development and Validation,” Computers & Education 55, no. 4 (2010): 1764–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.001.

- Special Education. While schooling that is inclusive of neurodiverse learning is increasingly becoming the norm within schools generally, some schools exist to provide education that is tailored for students with special needs, neurodiversity, or giftedness. These may include specific curricular approaches such as Arrowsmith programming or the Orton-Gillingham method. Special Education schools were not included under the Individualized subtype, or vice versa. 27 27 K. McCarty, “Full Inclusion: The Benefits and Disadvantages of Inclusive Schooling; An Overview,” Azusa Pacific University, 2006, 11, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED496074.pdf. It is likely that all designated Special Education schools were placed in this subtype, but the researchers were not able to confirm this because Alberta Education does not provide a list of schools with this designation.

- Other Special Emphasis. Any school that did not fit into one or more of the aforementioned subtypes, but that has an identifiable educational specialty, pedagogical approach, or student demographic that is central to its purpose or identity was given the Other Special Emphasis classification.

Results

Number of Schools

Alberta Education maintains publicly available data in separate lists for school information and for student enrolment. These data sets are not reconciled. There are more schools listed in the school and school authority information reports than are present in the separately reported enrolment data.

The school and school authority information reports of June 27, 2023 list 221 independent schools. After excluding closures and schools typed as Auxiliary, 180 independent schools were identified in Alberta.

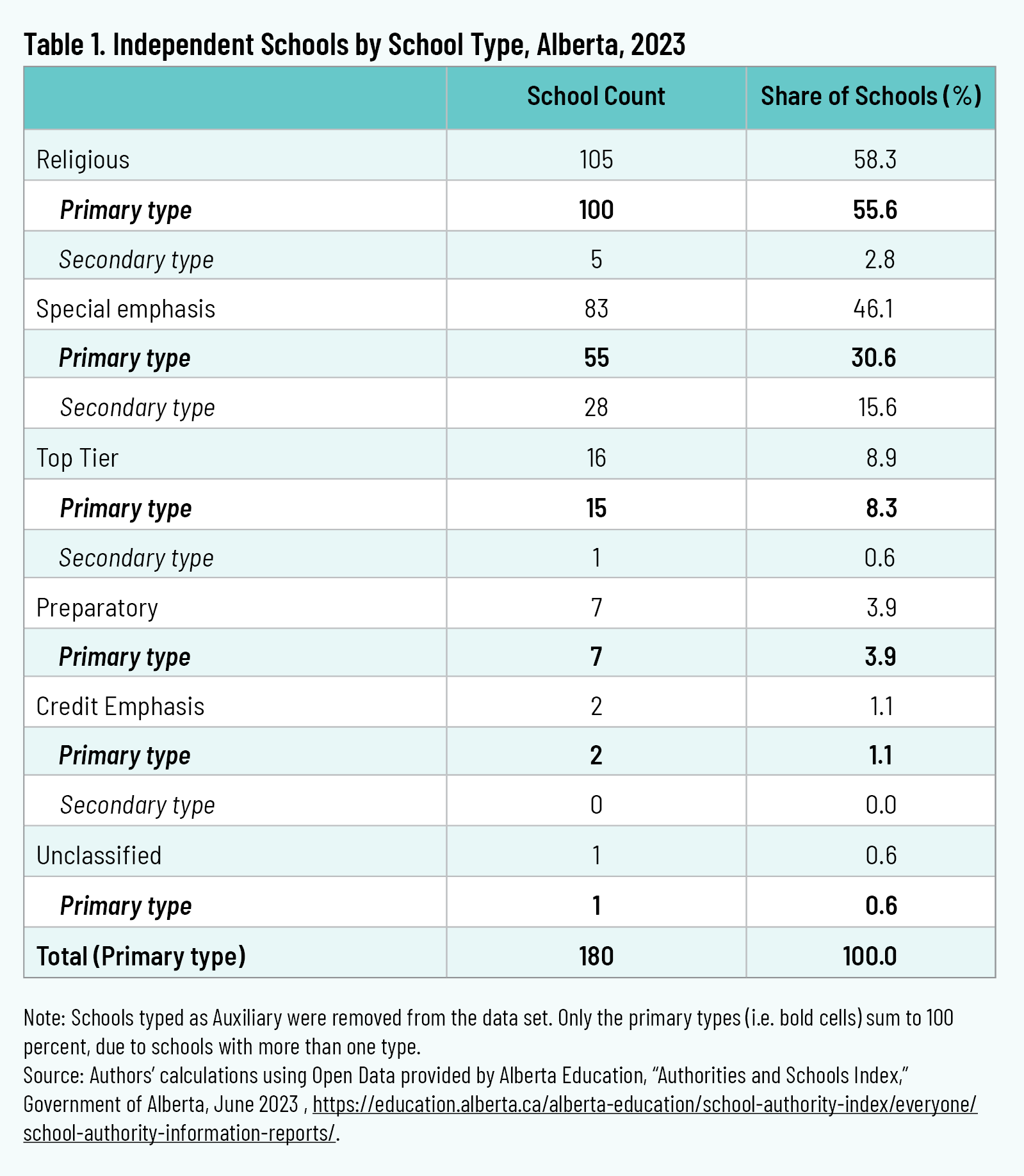

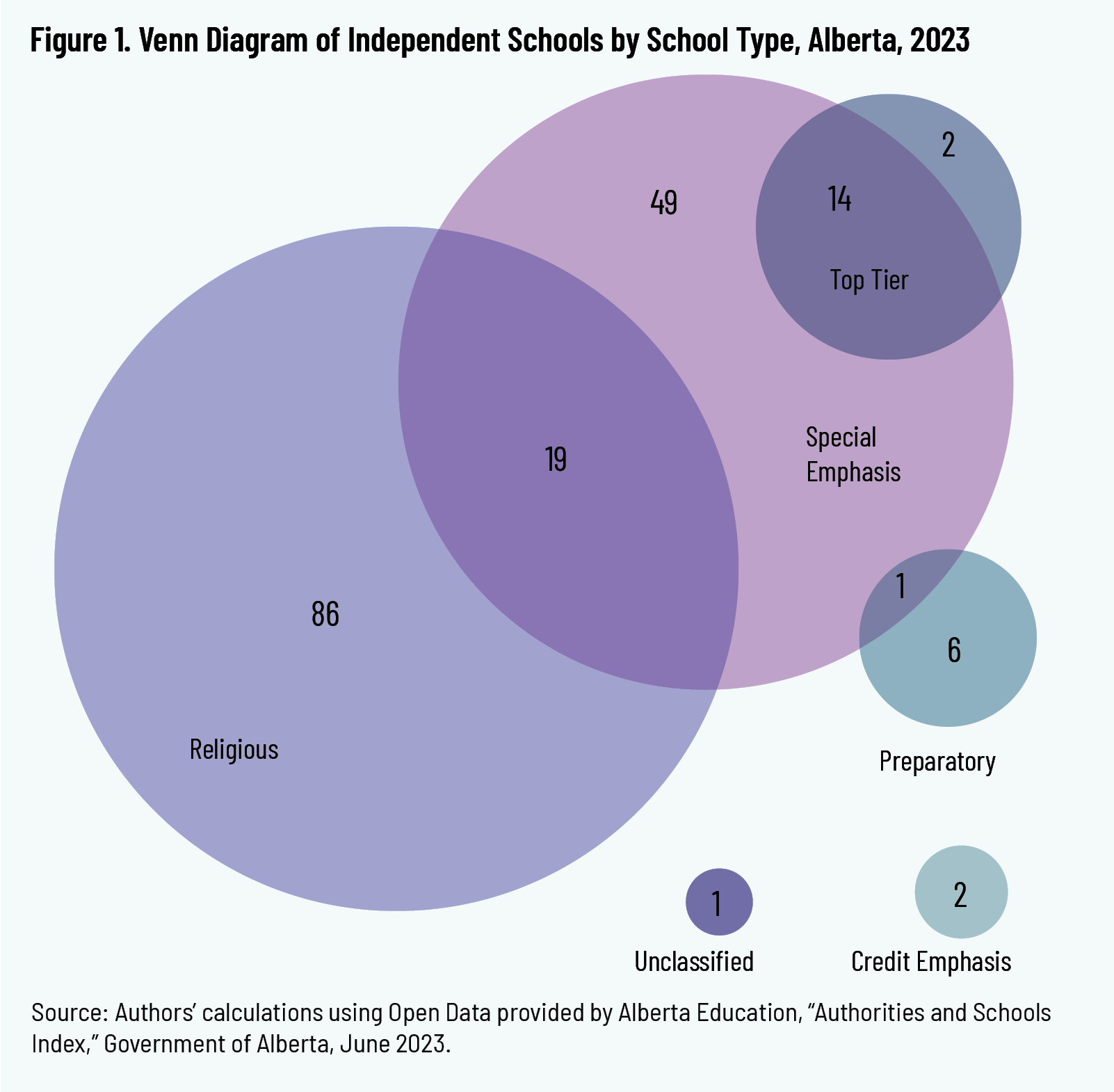

Of these 180 schools, 105 are Religious, eighty-three are Special Emphasis, sixteen are Top Tier, seven are Preparatory, two are Credit Emphasis, and one is Unclassified. These numbers add up to 214 because thirty-four schools fit more than one type. The remaining 146 are of just one type. Table 1 presents the 180 independent schools by primary and secondary type.

Figure 1 uses a Venn diagram to visualize the overlap of types (that is, the distribution of multi-type schools) and the share of each type in the sector.

Enrolment

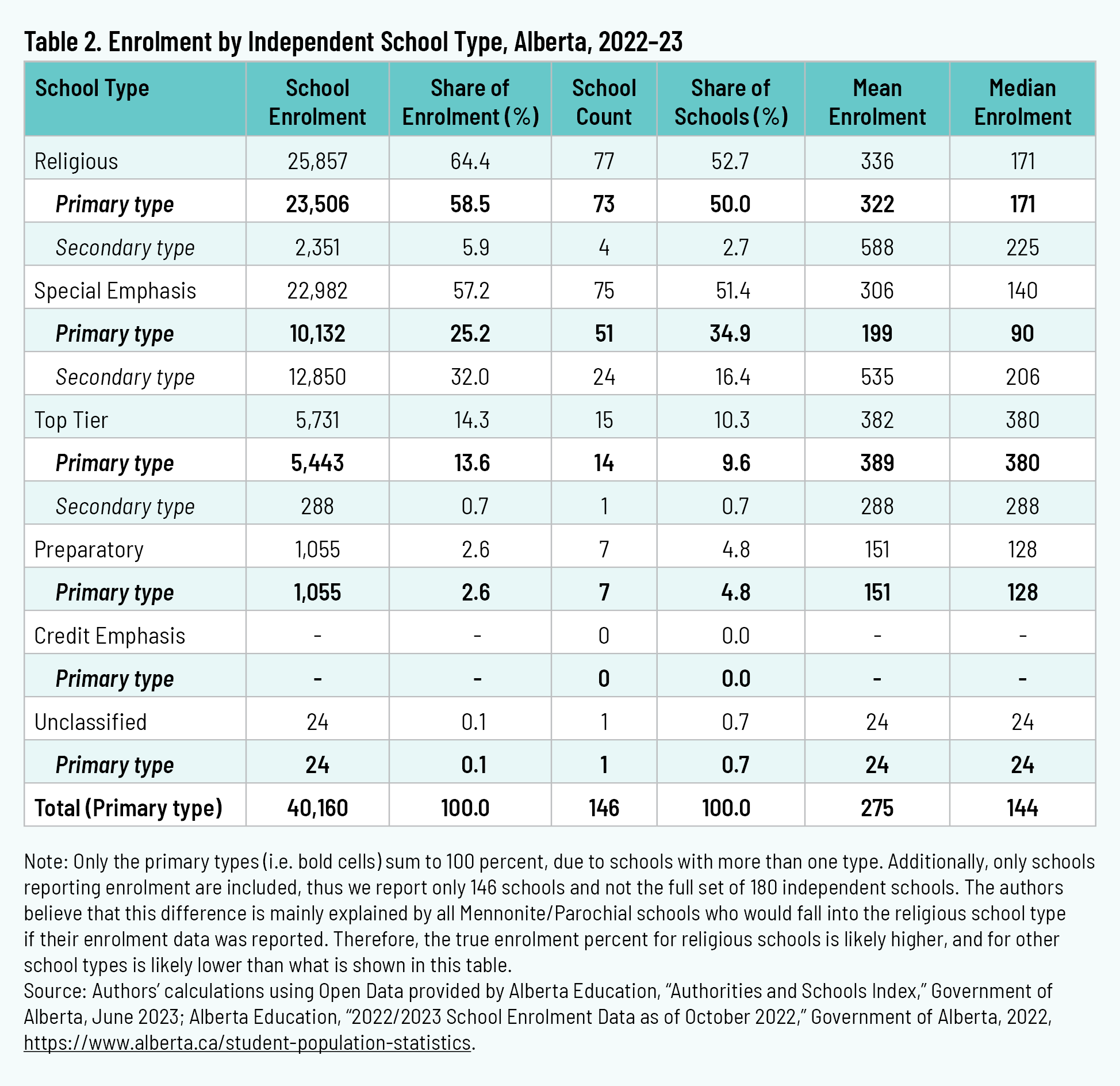

The most recent enrolment data was for the 2022–23 year (dated October 31, 2022). Some independent schools do not report enrolment numbers to Alberta Education. The researchers observed that these are mainly Mennonite/Parochial schools, along with a small number of Special Emphasis and Credit Emphasis schools. After excluding ECS private operators, schools that were closed, or schools typed Auxiliary, 146 schools were left for analysis.

Table 2 presents the enrolment for these 146 schools, by school type. The total enrolment is at least 40,160 students, since some schools do not report enrolments.

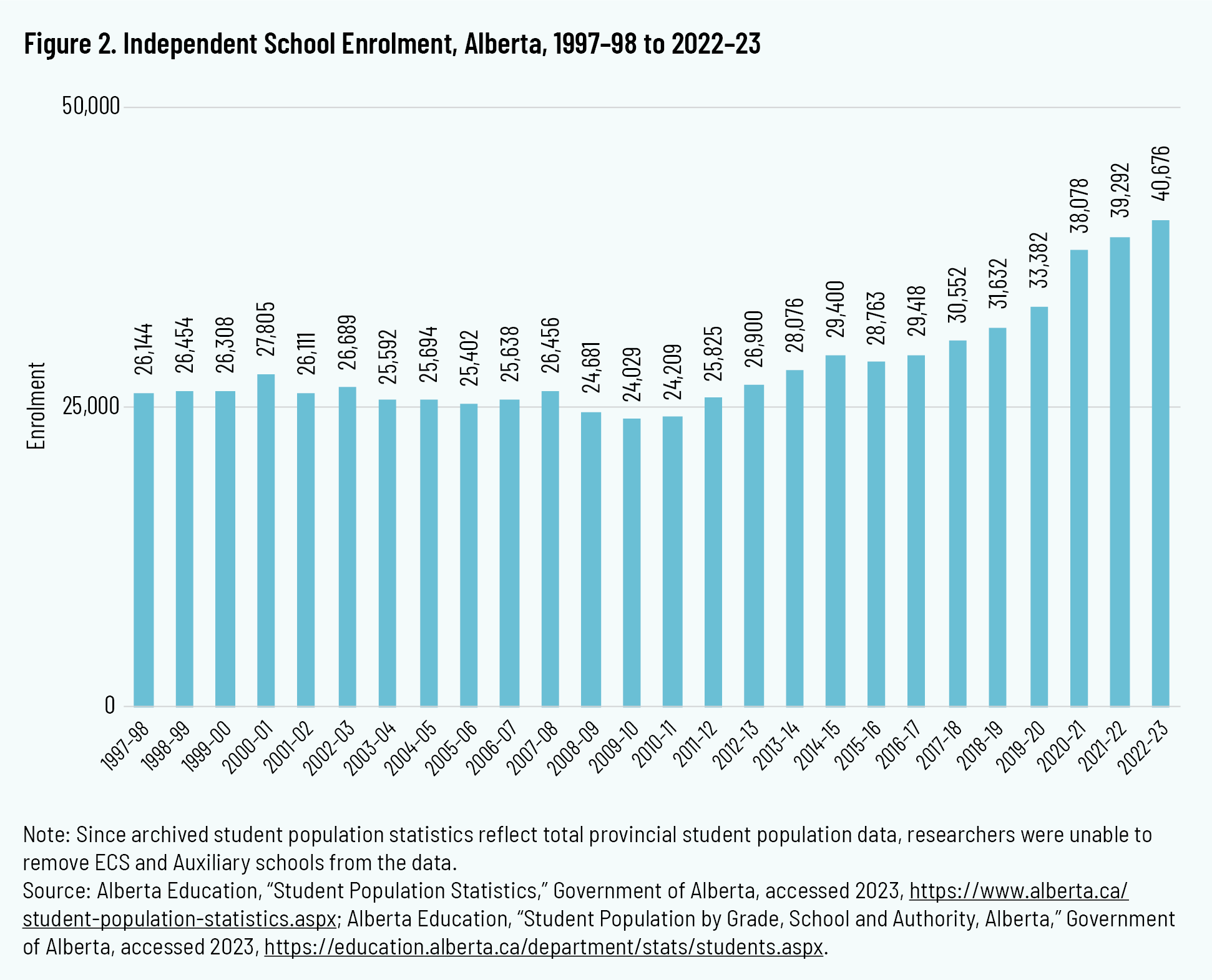

Growth Trends

The current enrolment of independent students in Alberta can be situated within a context of about ten years of steady growth. Figure 2 shows independent school enrolment over the past twenty-six years. The enrolment increased 55.6 percent between 1997–98 (earliest available data) and 2022–23. The number of students increased from 26,144 to at least 40,676 (the actual count is likely higher). 28 28 The total enrolment numbers for this figure are slightly higher than the total enrolment for the 146 schools in our final data set. This may be due to the inclusion of heritage language schools by the government in their total enrolment numbers, whereas these schools were excluded and therefore not included in school enrolment figures. Enrolment was relatively flat in the 2000s, dipped below 25,000 students from 2008–09 through 2010–11, and has been trending upward since then, with a particularly large increase in 2020–21, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

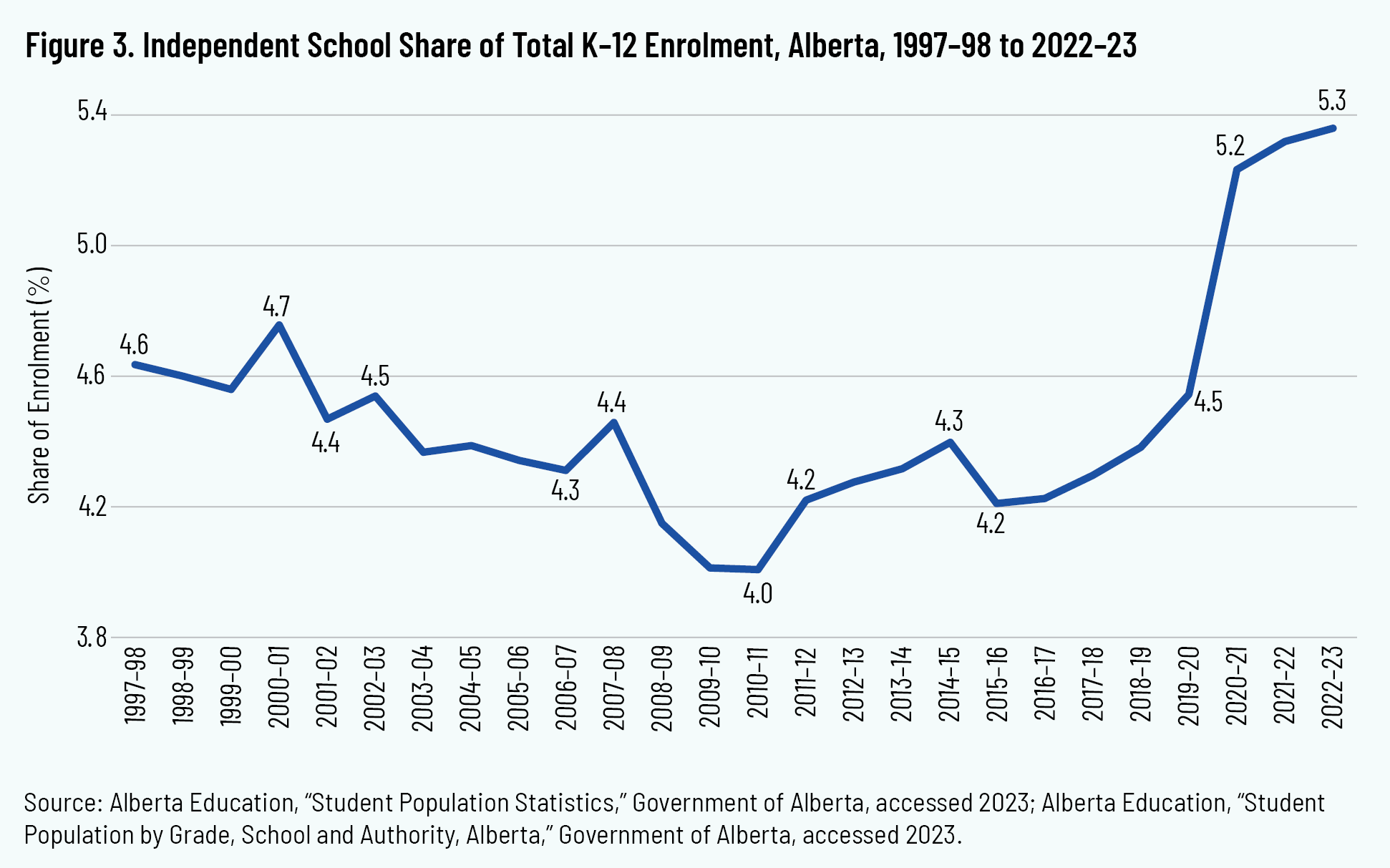

Enrolment growth has not been specific to independent schools. Enrolment at all other Alberta schools also increased during this period, albeit to a lesser extent (the percent increase was 33.4). Figure 3 shows that in the 2000s (when many large Christian independent schools merged into the district system as fully funded alternative schools), the share of independent schools declined from 4.7 percent of provincial enrolment in 2000–01 to 4.0 percent in 2009–10. Since 2010–11, the independent share of enrolment has risen to 5.3 percent today. The pandemic appears to have accelerated this growth trend.

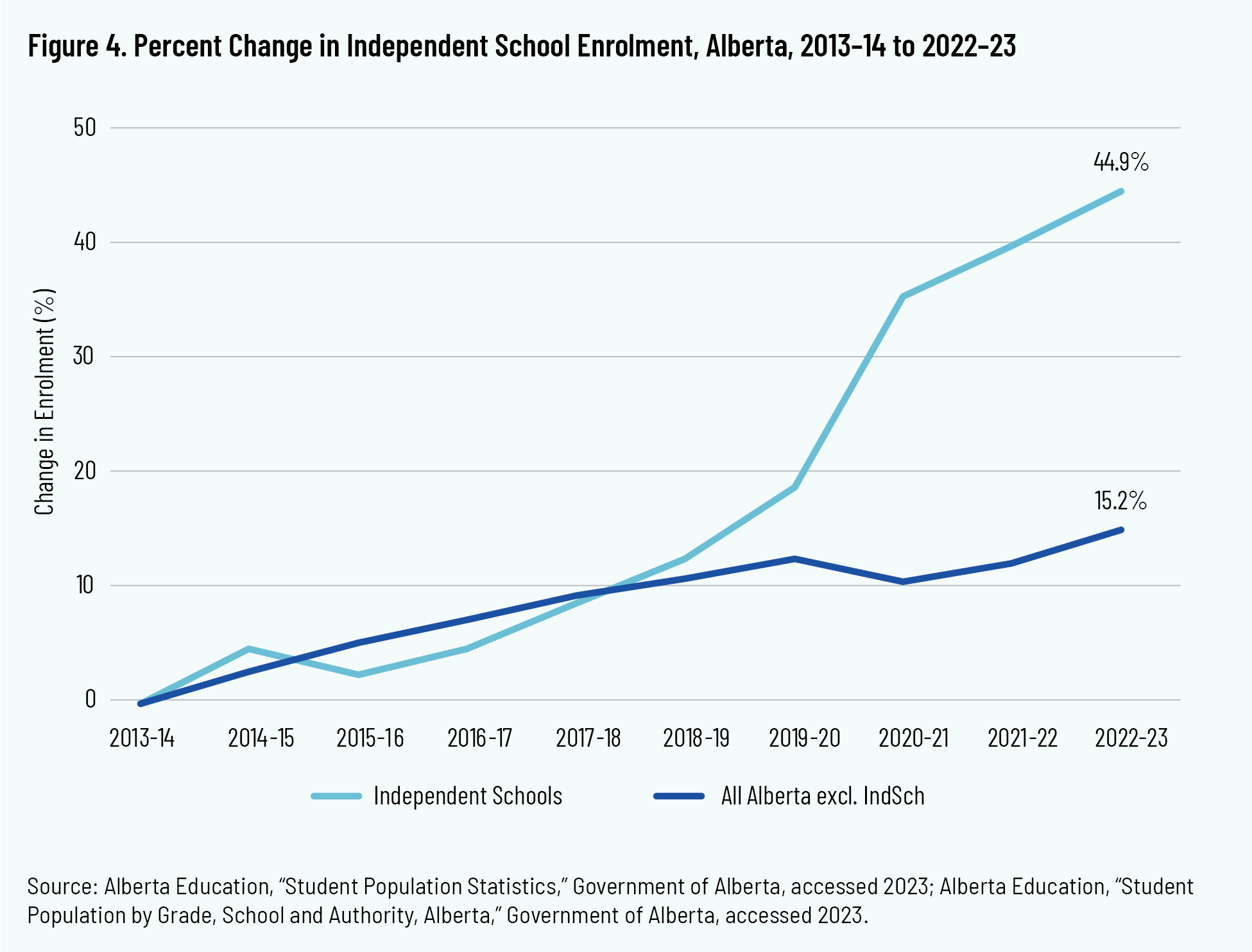

Figure 4 shows the enrolment growth across independent and non-independent schools. Enrolment in independent schools has grown nearly three times as fast as it has in other schools. Independent school enrolment grew 44.9 percent, compared to 15.2 percent for the other school types. Prior to 2019–20, the growth patterns looked similar, but beginning in 2019–20, the pandemic seems to have generated a surge in enrolment in independent schools.

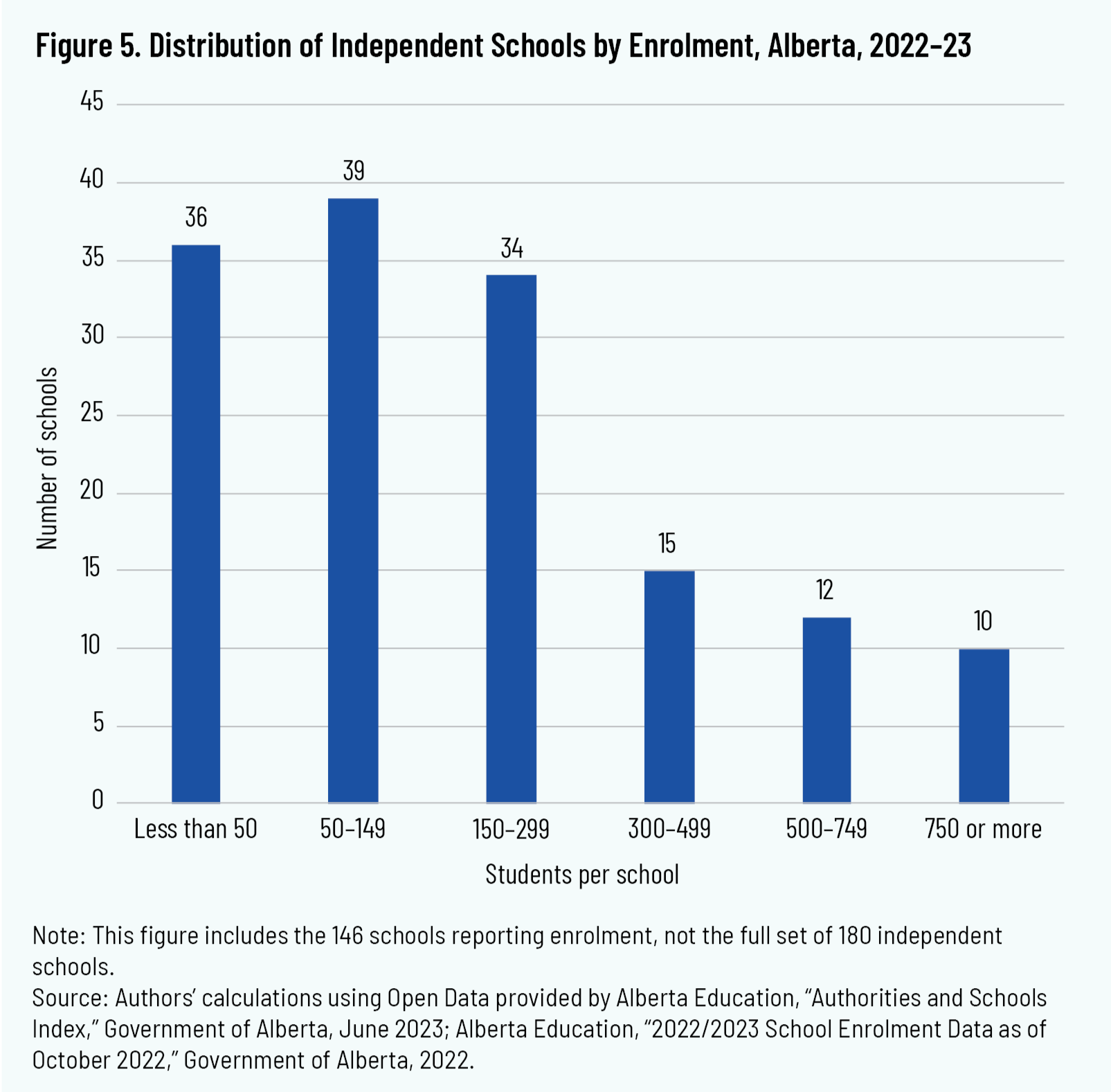

Distribution by School Size

Figure 5 demonstrates the distribution of schools by size. Of the 146 schools for which enrolment data are available, 109 schools (75 percent) have fewer than 300 students. These schools are nearly evenly distributed across the first three size categories: 24.7 percent of the schools have fewer than fifty students, 26.7 percent have 50–149 students, 23.3 percent have 150–299 students. The remaining thirty-seven schools (25.3 percent) enrol 300 or more students.

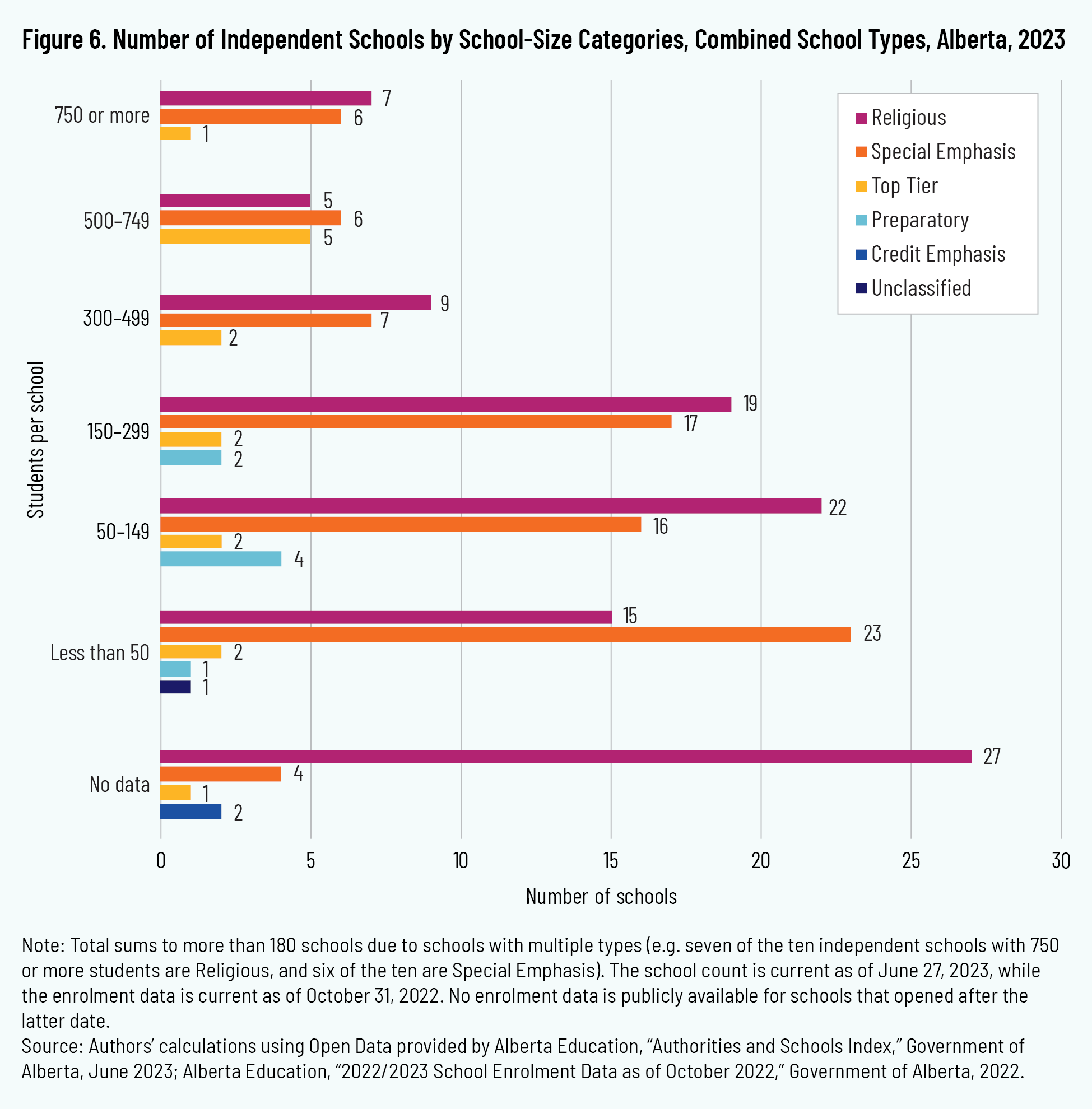

Figure 6 identifies the type of school according to school size. Religious, Special Emphasis, and Top Tier schools are represented in each size level. Of fifteen Top Tier schools, six have more than 500 students, and over half have 300 and more students. The only other types that have schools this large are Religious (at 20 percent) and Special Emphasis (at 21.6 percent). Four of the ten schools with over 750 students are Special Emphasis Distributed Learning schools, three are Religious, and one is Top Tier. There is only a handful of large-campus independent schools in Alberta. Also of note, twenty of the twenty-seven Religious schools with no data are Mennonite and/or Parochial schools, which do not publicly report enrolments.

Distribution by Program Type

Alberta Education’s School and Authorities Information Reports include a data point on whether the school provides home-education supervision, shared responsibility, outreach programs, and online learning. The data do not distinguish between partial, blended, and full-time online learning, but hybrid schooling is at least implicitly recognized by the government’s differentiation between home education and shared-responsibility programs. 29 29 E. Wearne, “National Hybrid Schools Project,” Kennesaw State University, Georgia. https://www.kennesaw.edu/coles/centers/education-economics-center/national-hybrid-schools-project/. In schools that offer shared-responsibility programs, “the school authority is responsible for a minimum of 20 percent to a maximum of 80 percent of the student’s program in Grades 1 to 12.” 30 30 Alberta Education, “Shared Responsibility Program,” Government of Alberta, https://www.alberta.ca/shared-responsibility-program. Students below this range are enrolled as home-education students (omitted from our analysis), and above this range they are enrolled as regular or online students.

In some cases, outreach programs are offered as an educational alternative for high school students for whom traditional schooling does not meet their needs. 31 31 Alberta Education, “Outreach Programs,” Government of Alberta, https://www.alberta.ca/outreach-programs. Since these programs are not mutually exclusive of online learning, and since the province counts students enrolled in home education and shared-responsibility programs as both homeschool students and students registered at a school, this paper reports on online-learning programs only.

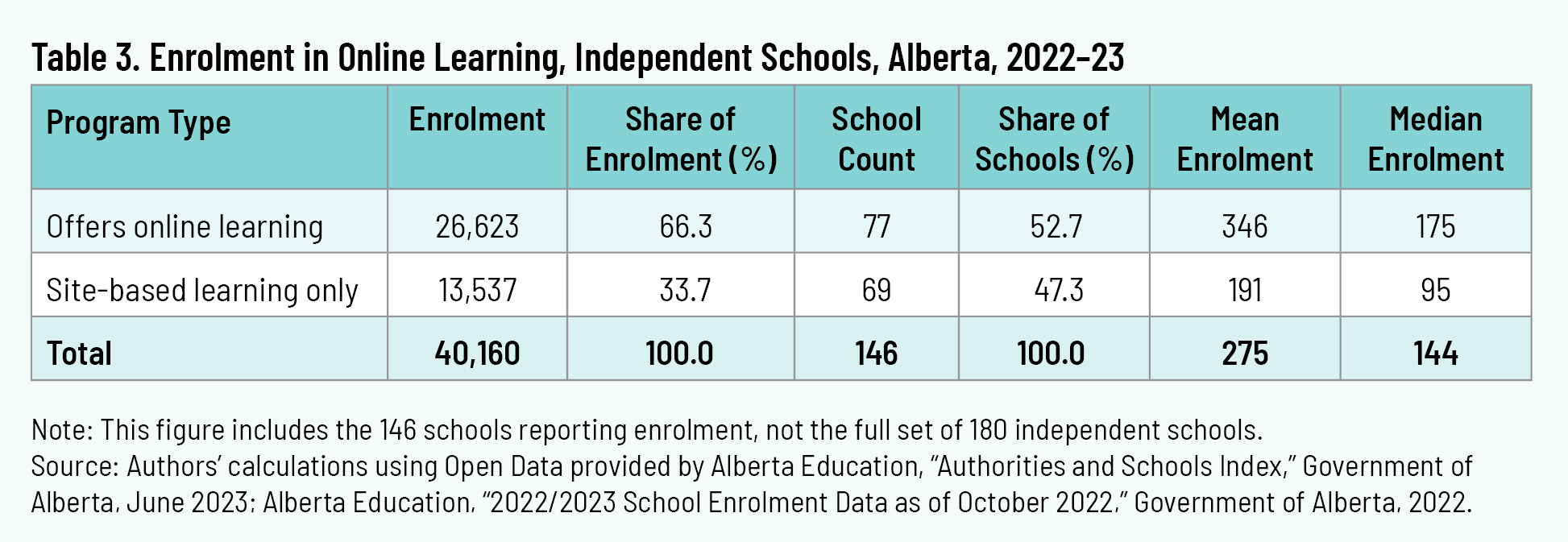

Eighty-one schools (45.0 percent) offer online learning in some capacity, but this count decreases to seventy-seven schools when schools without reported enrolment are excluded (table 3). In total, schools that offer online options enrol about two-thirds of the students with reported enrolments.

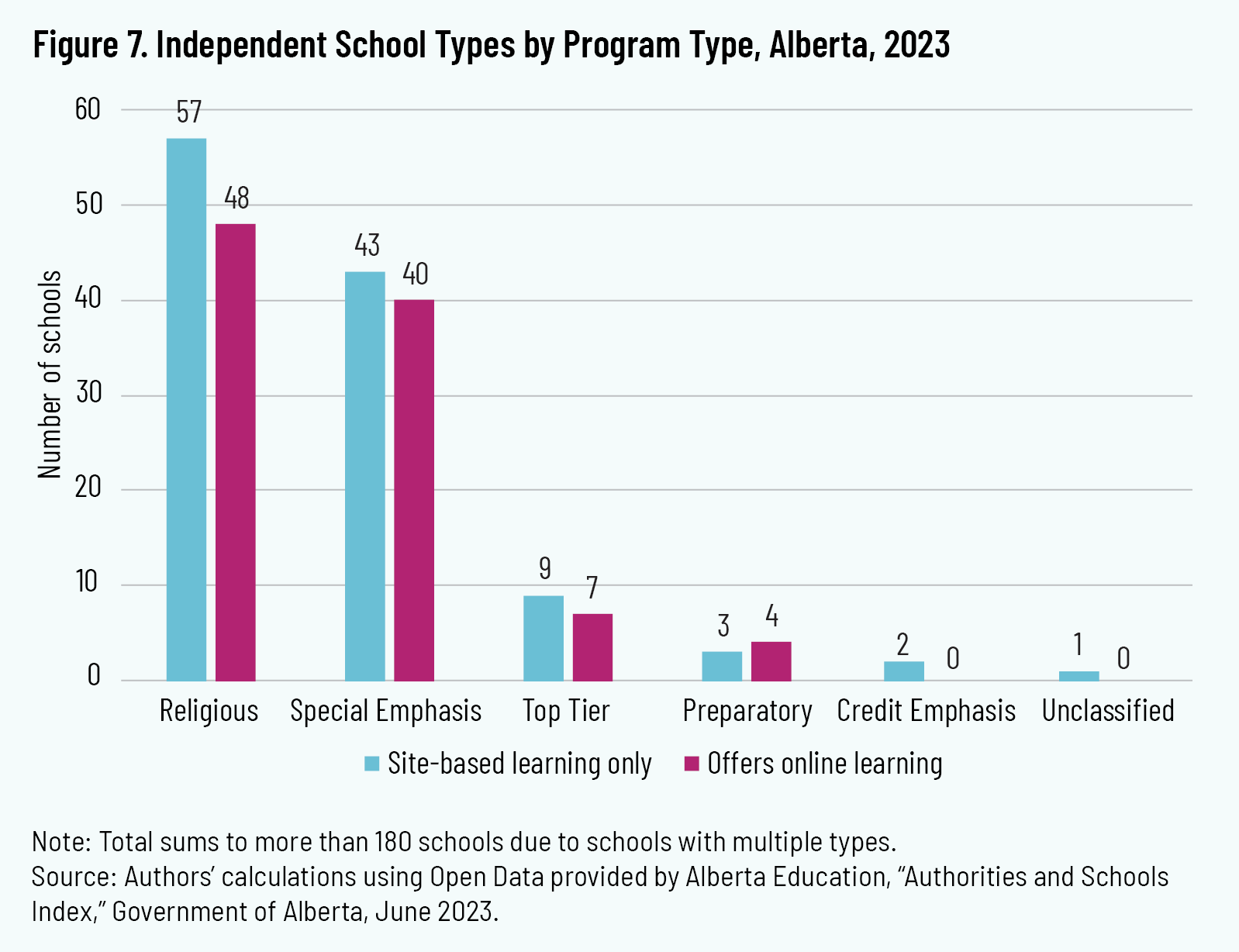

When cross-tabulating program type by school type (figure 7), the share of schools offering online learning is nearly the same between Religious, Special Emphasis, and Top Tier schools, at 45.7 percent, 48.2 percent, and 43.8 percent, respectively.

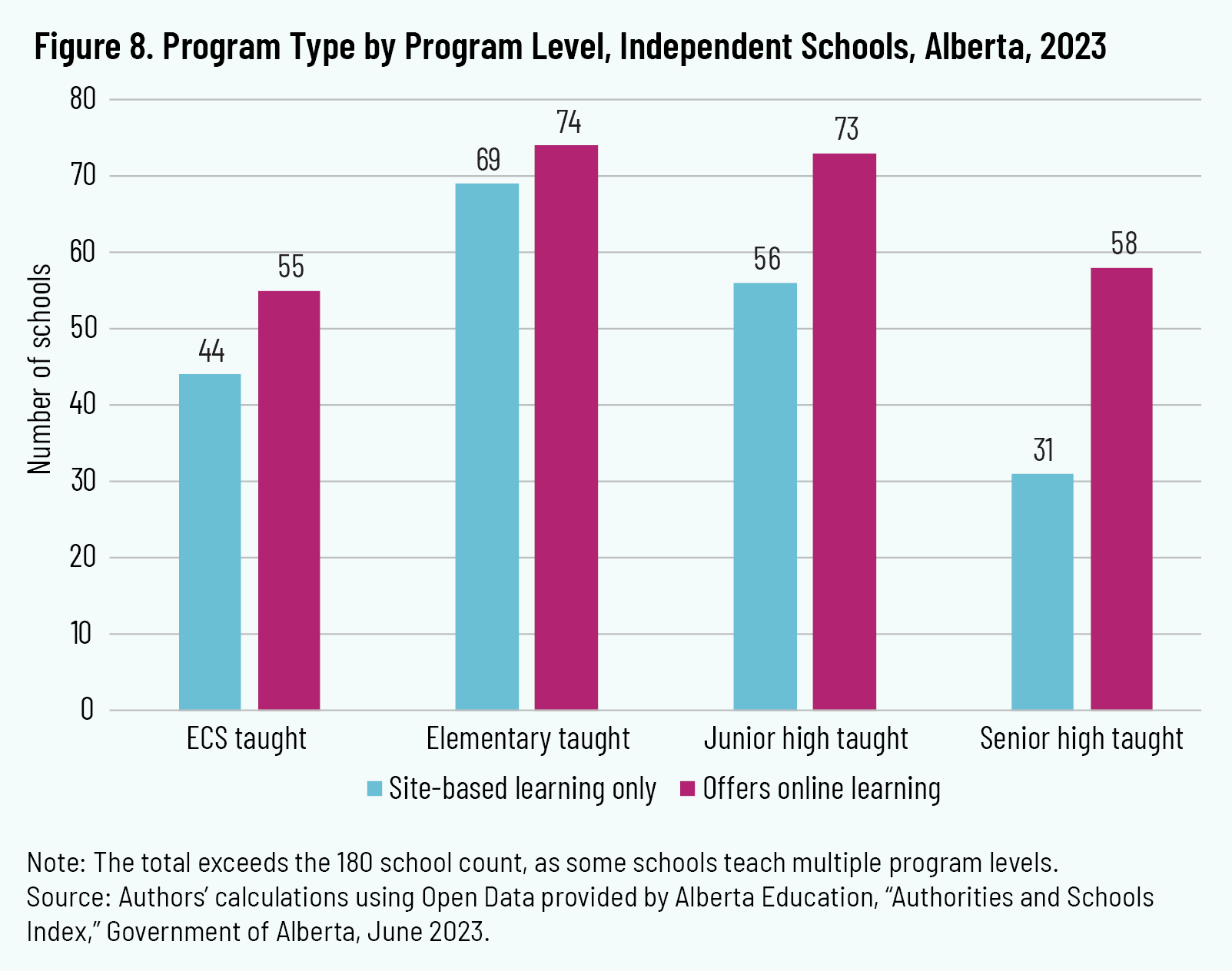

Figure 8 demonstrates the program level for which online learning takes place, whether in kindergarten, elementary, junior high, or senior high. Online-learning programs are slightly more prevalent in schools with junior and senior high program levels.

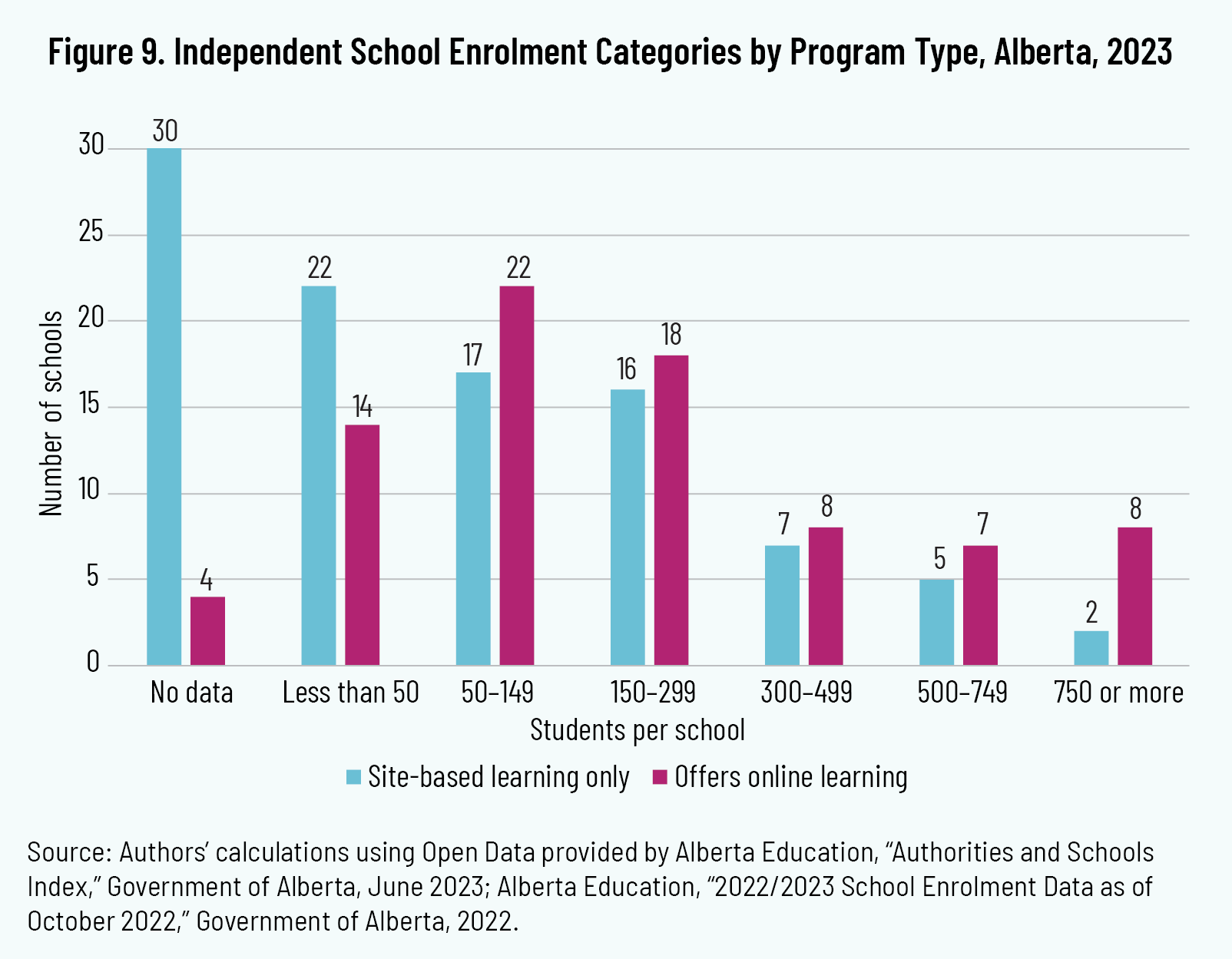

Crosstab analysis of school size, or enrolment categories, by online learning demonstrates that schools with higher enrolments are slightly more likely to offer online-learning programs (figure 9). Eight of ten schools (80.0 percent) with 750 or more students, and seven of twelve schools (58.3 percent) with 500–749 students, offer online programs. On the other hand, schools with less than fifty students tend to be site-based (twenty-two of thirty-six schools, or 61.1 percent). Schools with no enrolment data (mostly Mennonite/Parochial schools) are likely to be site-based only.

Distribution by Program Level

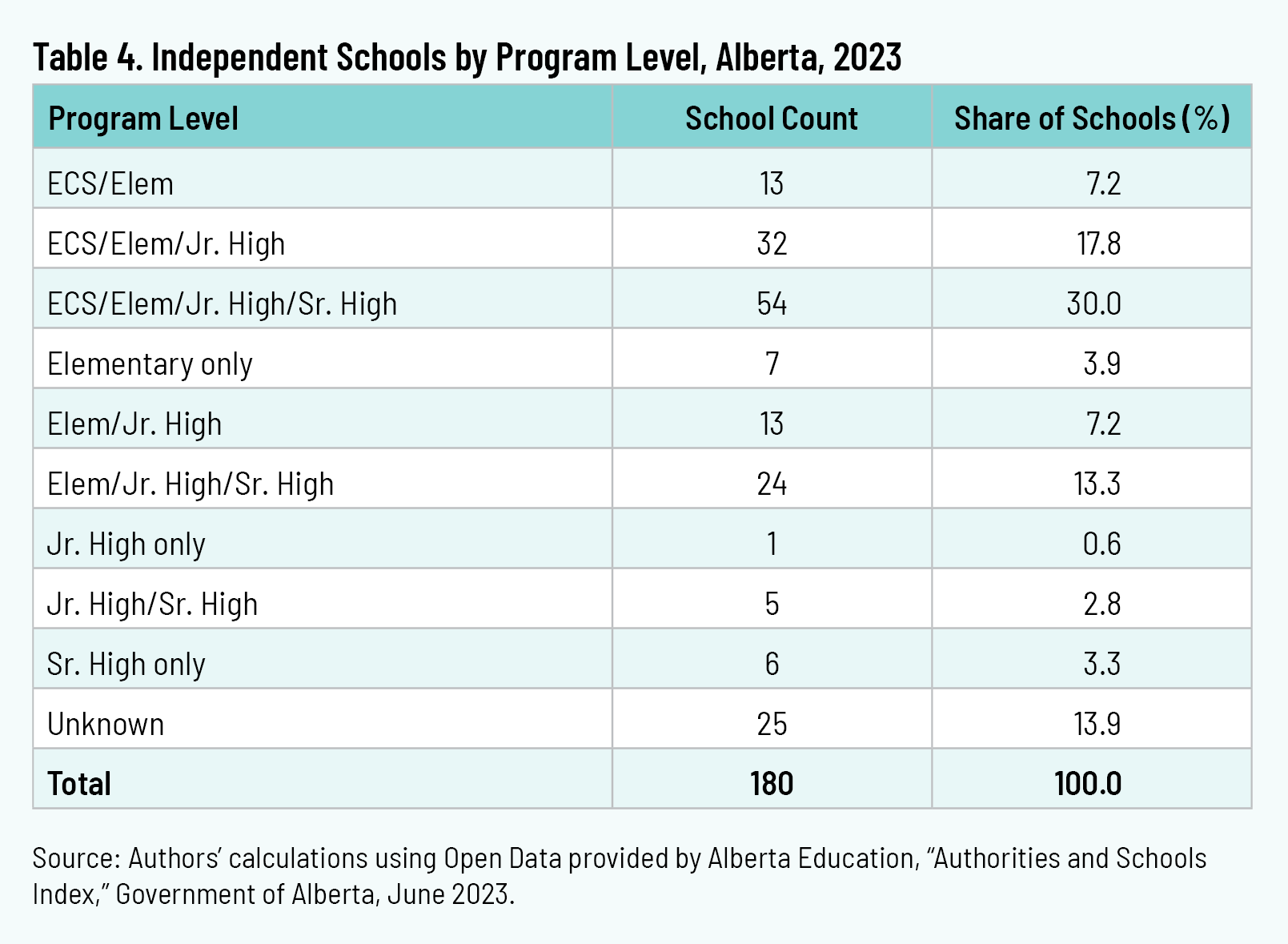

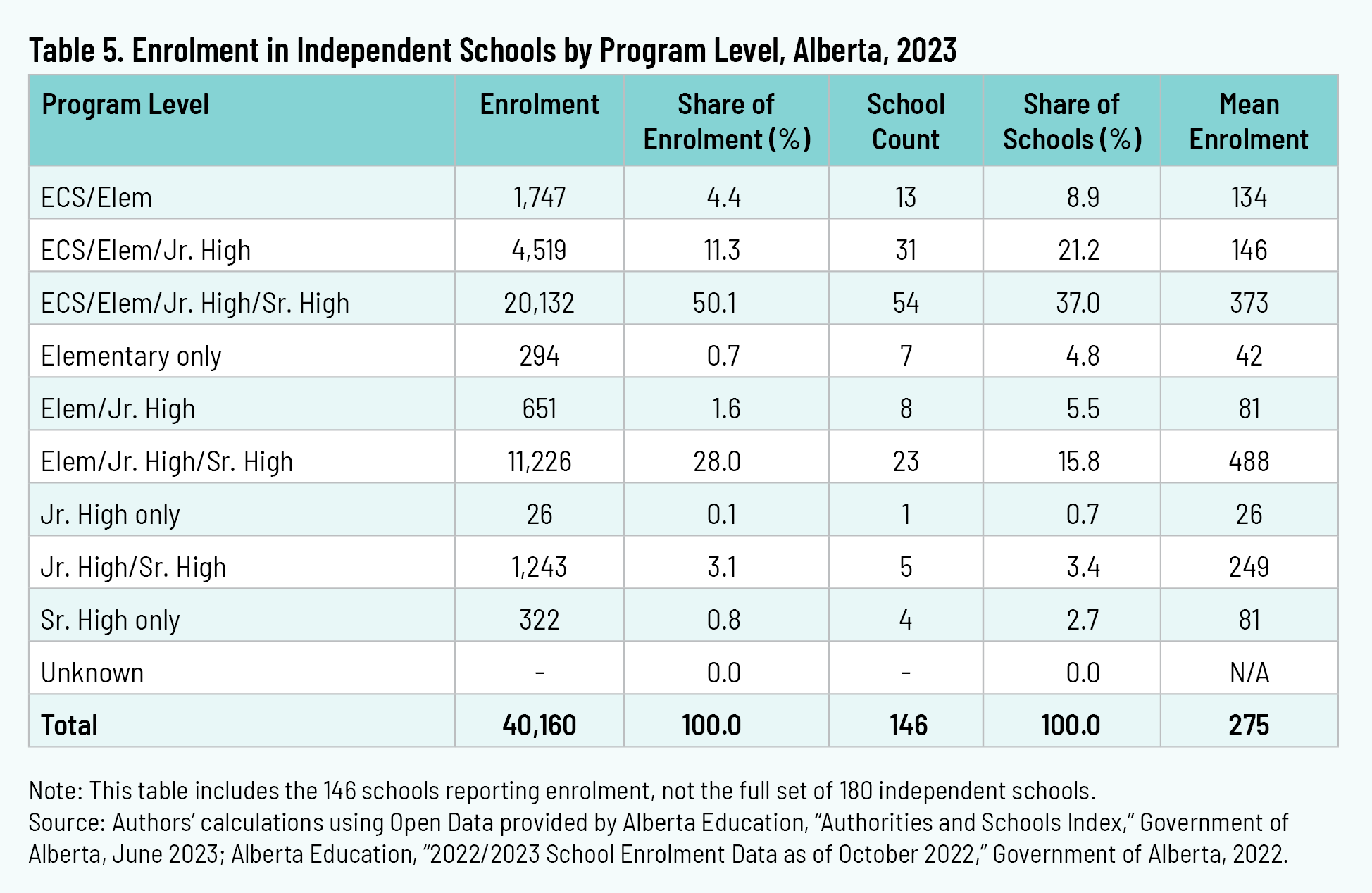

Program level is delineated according to an extensive number of categories, as table 4 shows. Schools that span all program levels (ECS to senior high) are the highest share of schools (fifty-four schools, 29.2 percent). Schools that offer a full elementary and secondary experience make up a combined 43.3 percent (78 schools) of the sector. When excluding schools without reported enrolment, combined elementary and secondary schools are over half the sector (52.7 percent) and enrol 78.1 percent of the sector’s students (table 5).

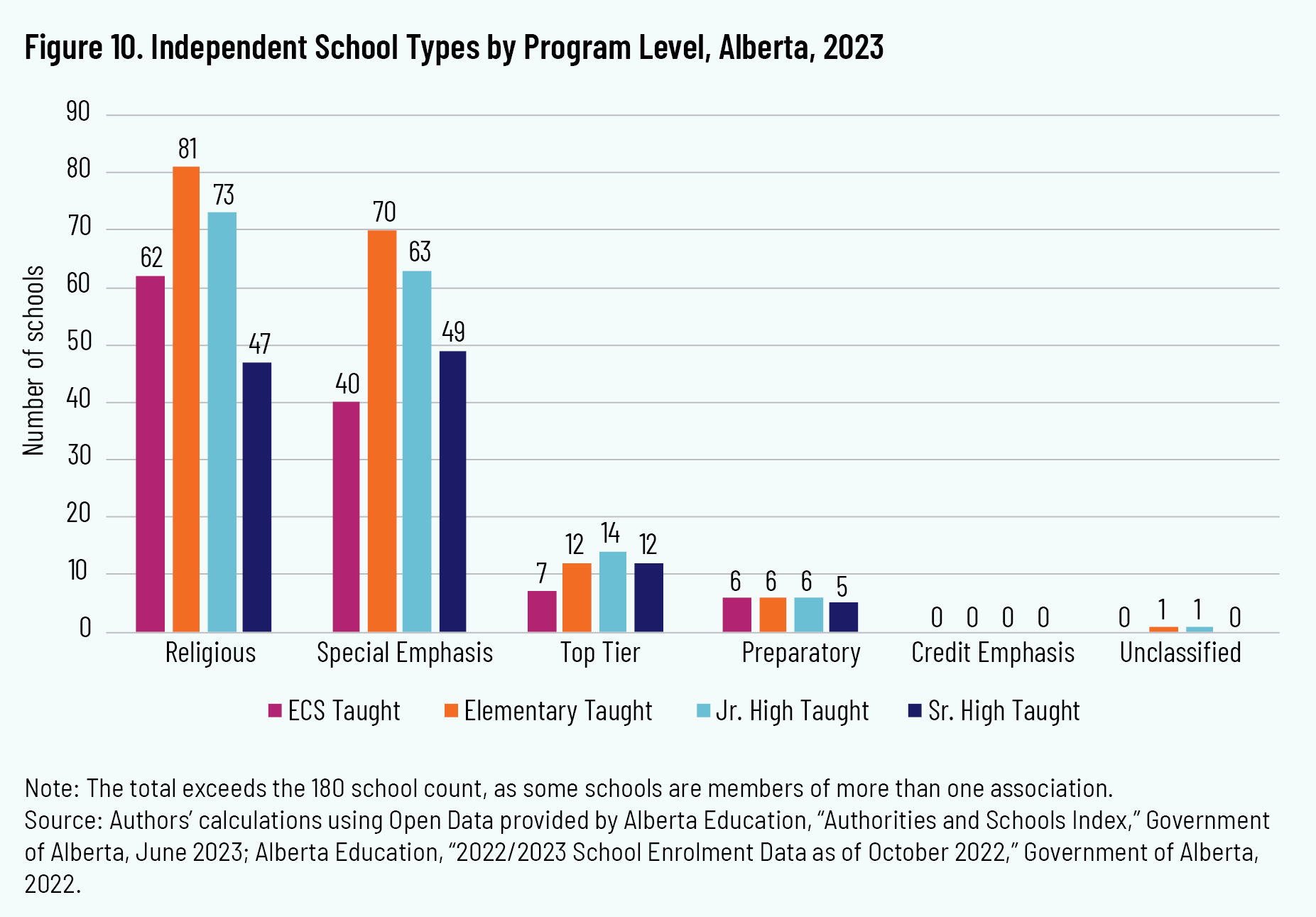

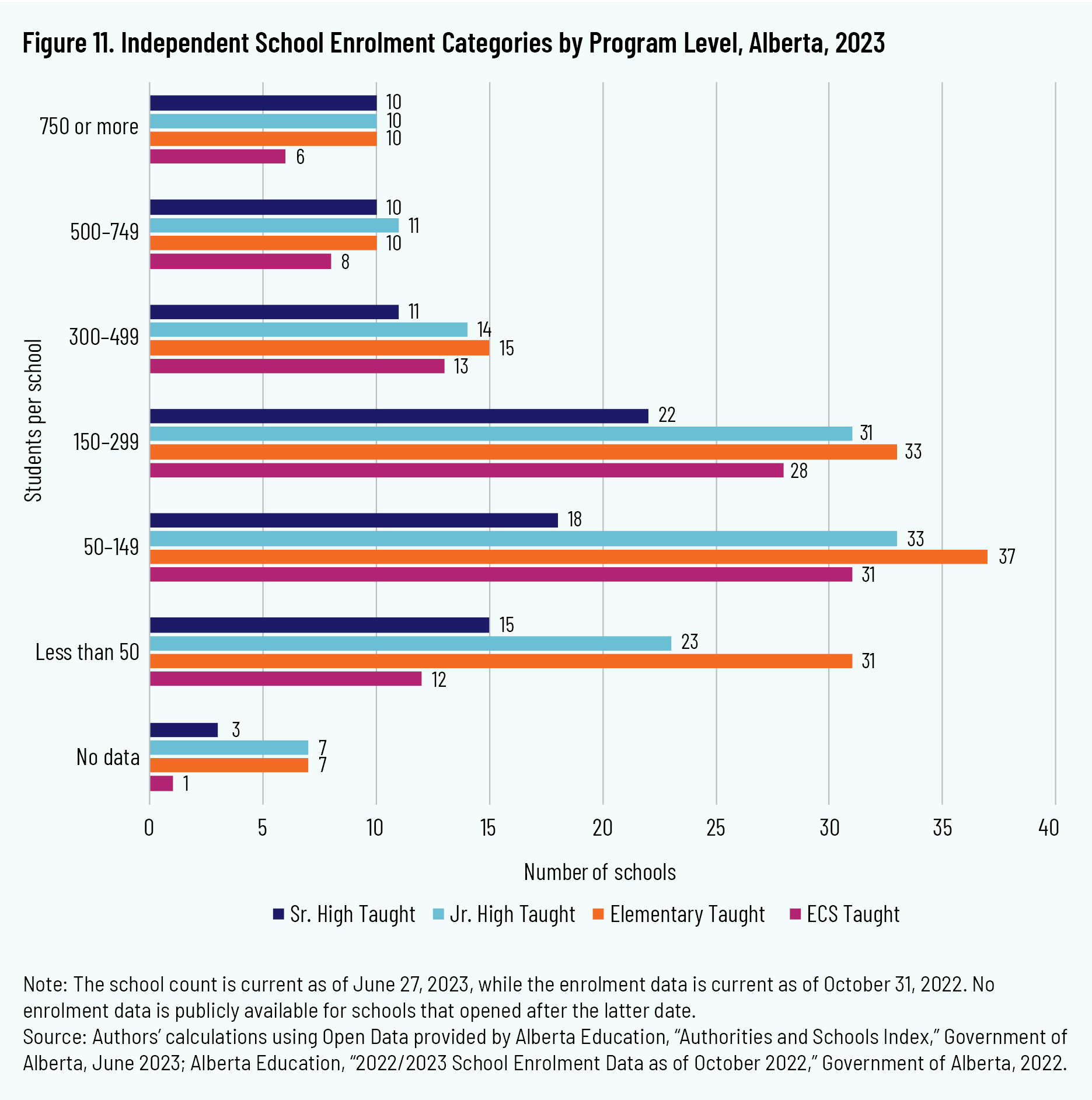

Figures 10 and 11 provide more nuance about the distribution of schools and enrolments by program level. Five of seven Preparatory schools and twelve of sixteen Top Tier schools offer senior high programs, compared to forty-nine of eighty-three (59.0 percent) Special Emphasis and forty-seven of 105 (44.8 percent) Religious schools. Since only accredited schools can offer senior high level courses, these can be assumed to be accredited schools. For Special Emphasis and Religious school types, the most common program levels are elementary, followed by junior high (figure 10). Figure 11 shows that smaller schools have a higher proportion of junior high, elementary, and ECS offerings than do larger schools with more than 300 students. In other words, it is more common for schools without a senior high level program to be smaller in size.

Of the schools with 500 or more students, there is a fairly even distribution across ECS, elementary, junior high, and senior high programs.

Distribution by School Subtypes

For two school types, Religious and Special Emphasis, the typology included subtypes.

Religious

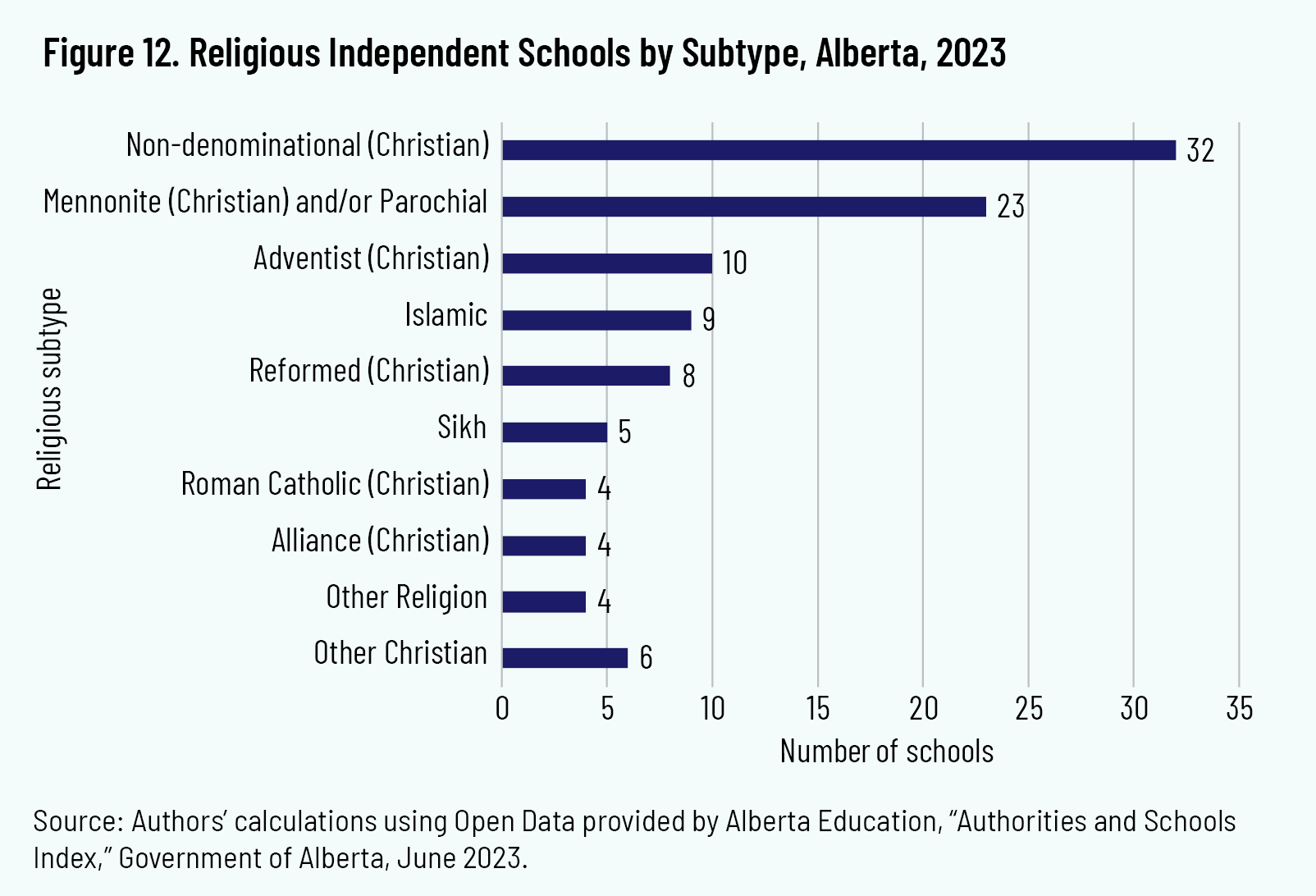

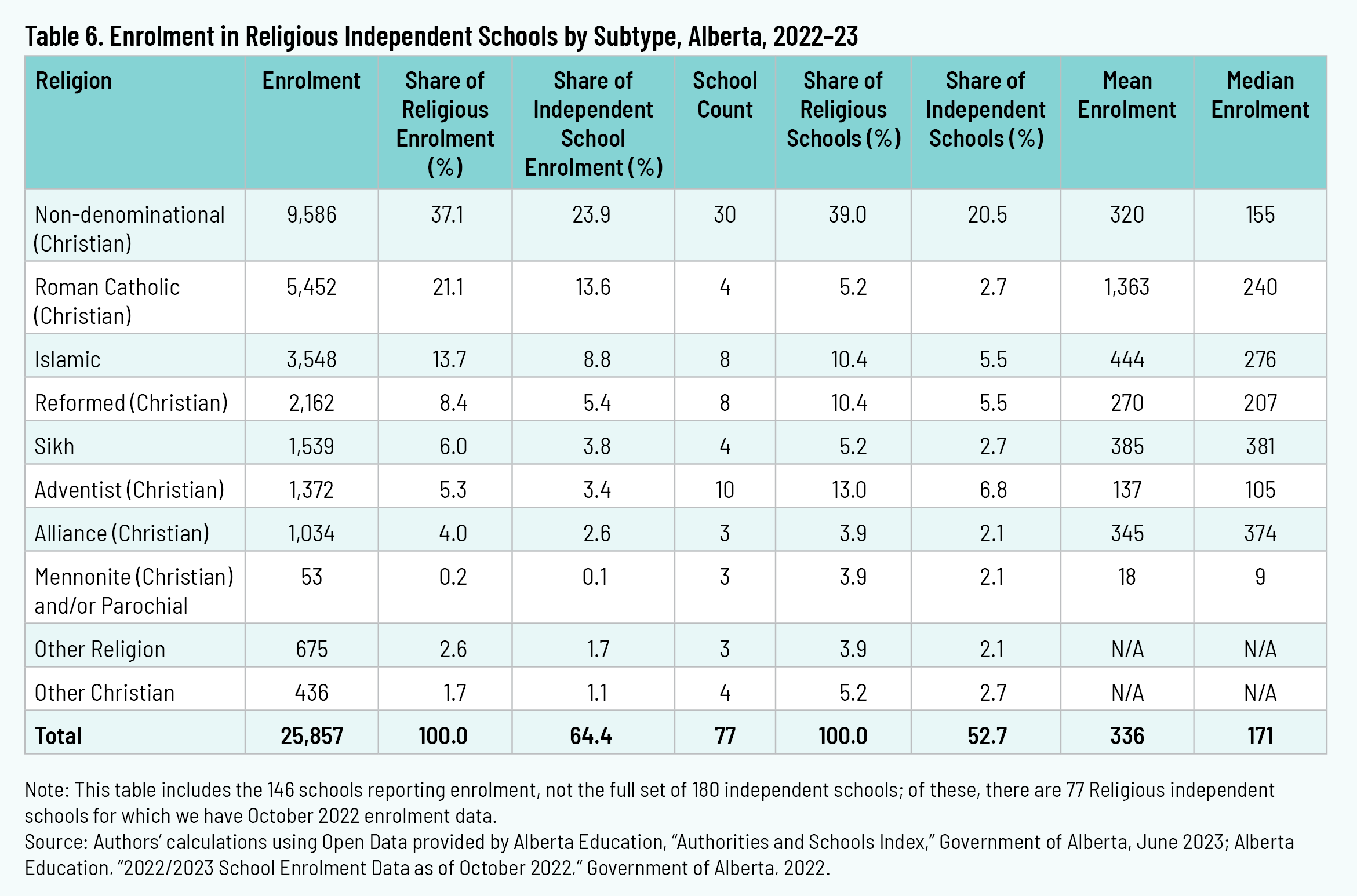

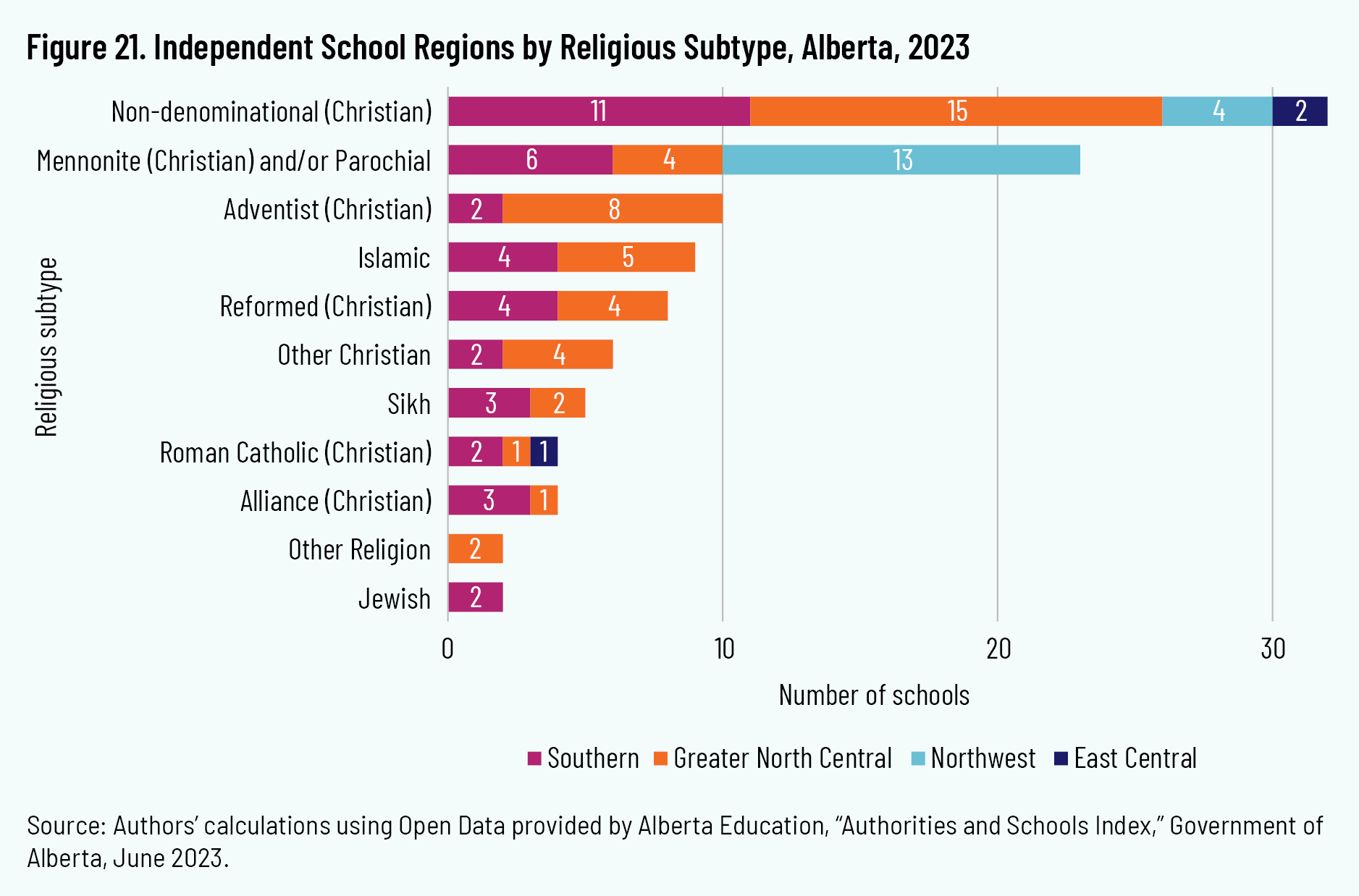

The most common independent school type in the province is Religious, at 105 schools (58.3 percent of the sector). The religious diversity within this type is considerable. There are schools reflecting the faith of six religions and, within Christianity, eleven denominations (including non-denominational and inter-denominational schools). Any religious affiliation or denomination with fewer than four schools was grouped into Other Religion or Other Christian.

Figure 12 and table 6 show the school count and enrolments of the Religious subtypes. The largest subtype is Non-denominational Christian, which encompasses nearly one-third of Religious independent schools (figure 12) and 37.1 percent of the Religious enrolment (table 6). Over 22 percent of Religious school enrolments are in Non-Christian schools, with a majority of these being in Islamic schools.

Three other observations are worth noting. Data are not available for twenty of the twenty-three Mennonite (Christian) and/or Parochial schools, so despite being the second largest in terms of school count, their rank in terms of enrolment is unknown. Second, although there are only four Roman Catholic (Christian) schools in the independent sector, these schools are also typed as Distributed Learning schools (which offer hybrid programs). It is likely that students enrolled in these schools are also enrolled in shared-responsibility or supervised home-education programs. These four schools enrol more than one in five students in Religious schools. And third, religious subtypes that were prevalent in the previous Ontario study, such as Jewish and Anglican, are minimal or non-existent in Alberta. Three Christian school subtypes were identified in Alberta that are not present in Ontario: Alliance, Lutheran, and Brethren. Since they each had fewer than four schools, they were included in Other Christian.

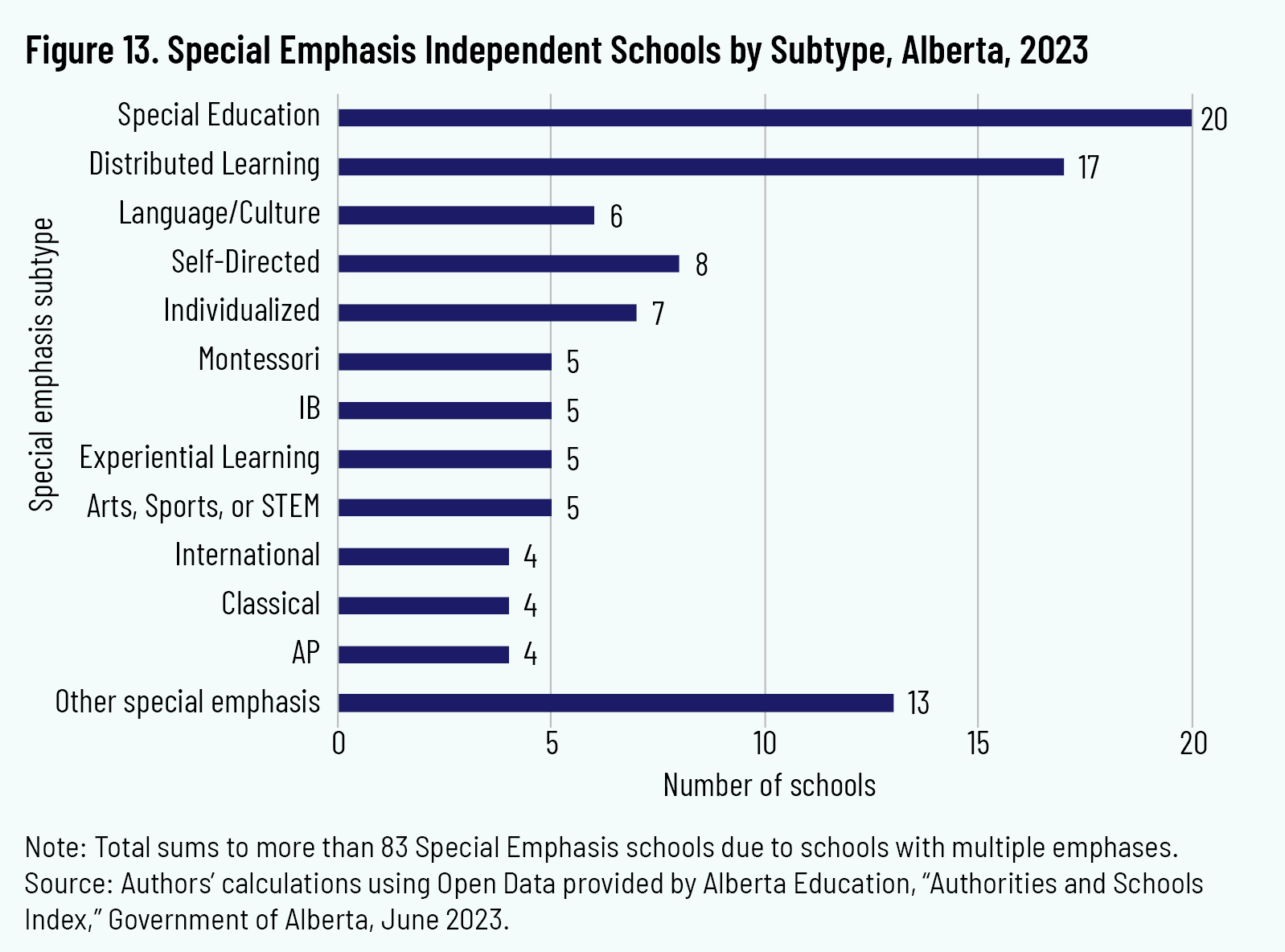

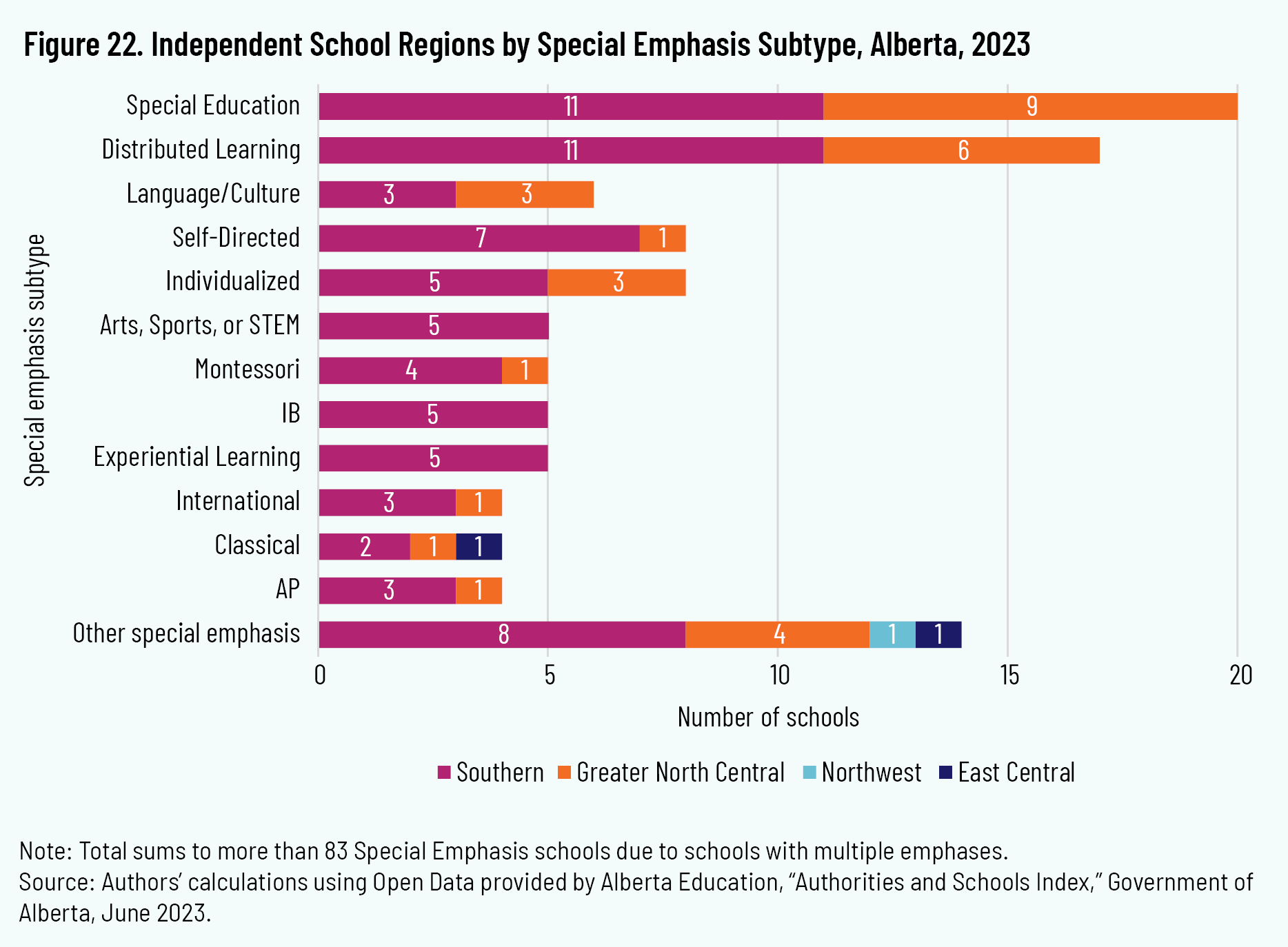

Special Emphasis

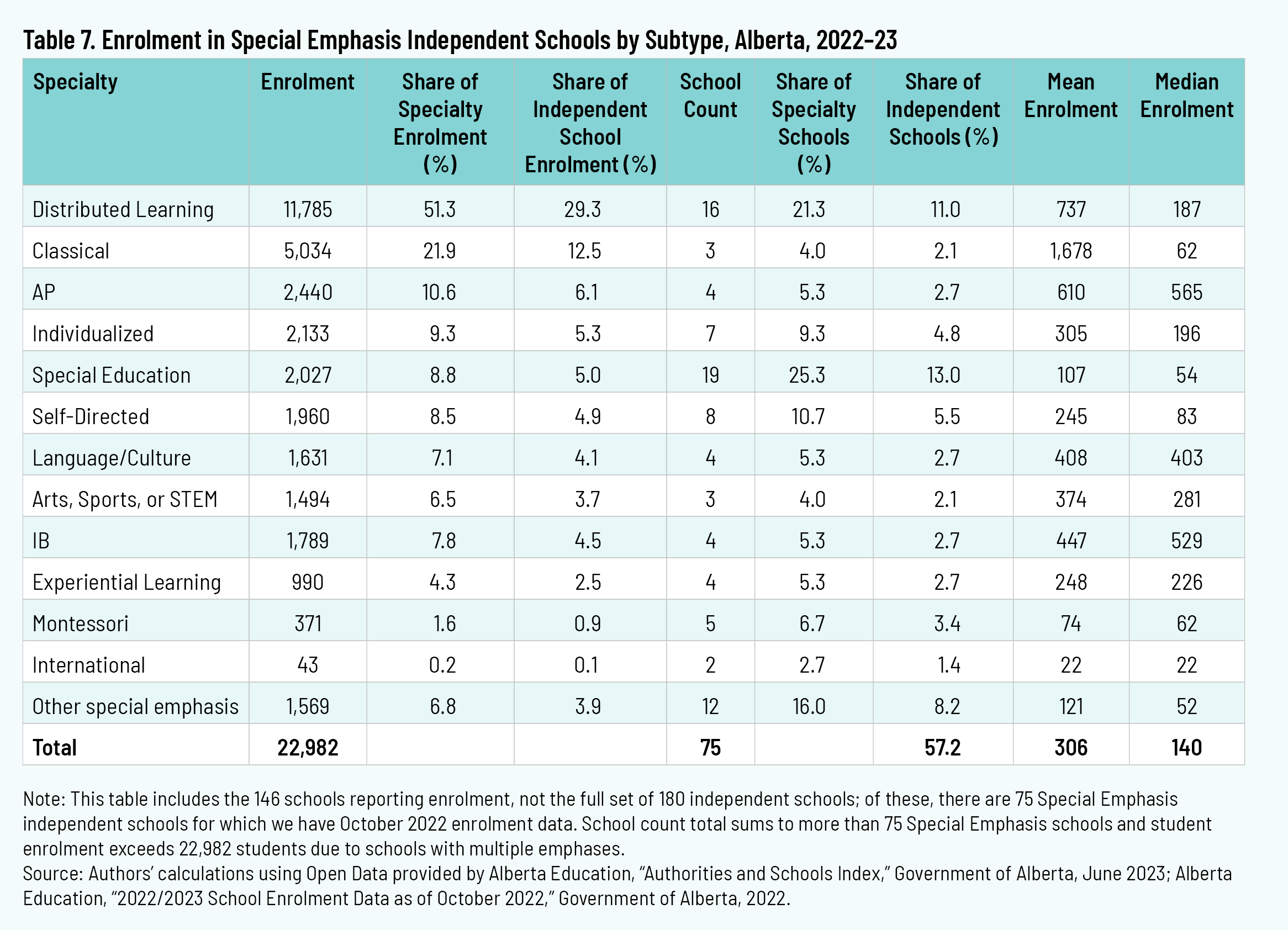

At eighty-three schools, 46.1 percent of Alberta’s independent schools have a Special Emphasis. Figure 13 ranks by school count the Special Emphasis subtypes that have four or more schools, and table 7 ranks by enrolment all subtypes with four or more schools. By school count, the most common Special Emphasis subtype is Special Education. Over half of Special Emphasis enrolment, and nearly one-third of all independent school enrolment, is in Distributed Learning schools.

Distribution by Association Memberships

School Associations

Many independent schools share resources and form bodies of accreditation and accountability to facilitate stability and growth, and to provide a cohesive voice in the public square. There are at least two reasons to categorize by school association. First, such affiliations help reveal shared aspects of identity. Second, examining school communities through the lens of associational affiliation reveals an additional layer of oversight, accountability, and independence beyond that of the individual school’s governing board. 32 32 The first study of Canada’s independent school associations was D. Van Pelt and P.J. Mitchell, “Mapping Independent School Associations in Canada,” Cardus, September 2018, https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/mapping-independent-school-associations-in-canada/.

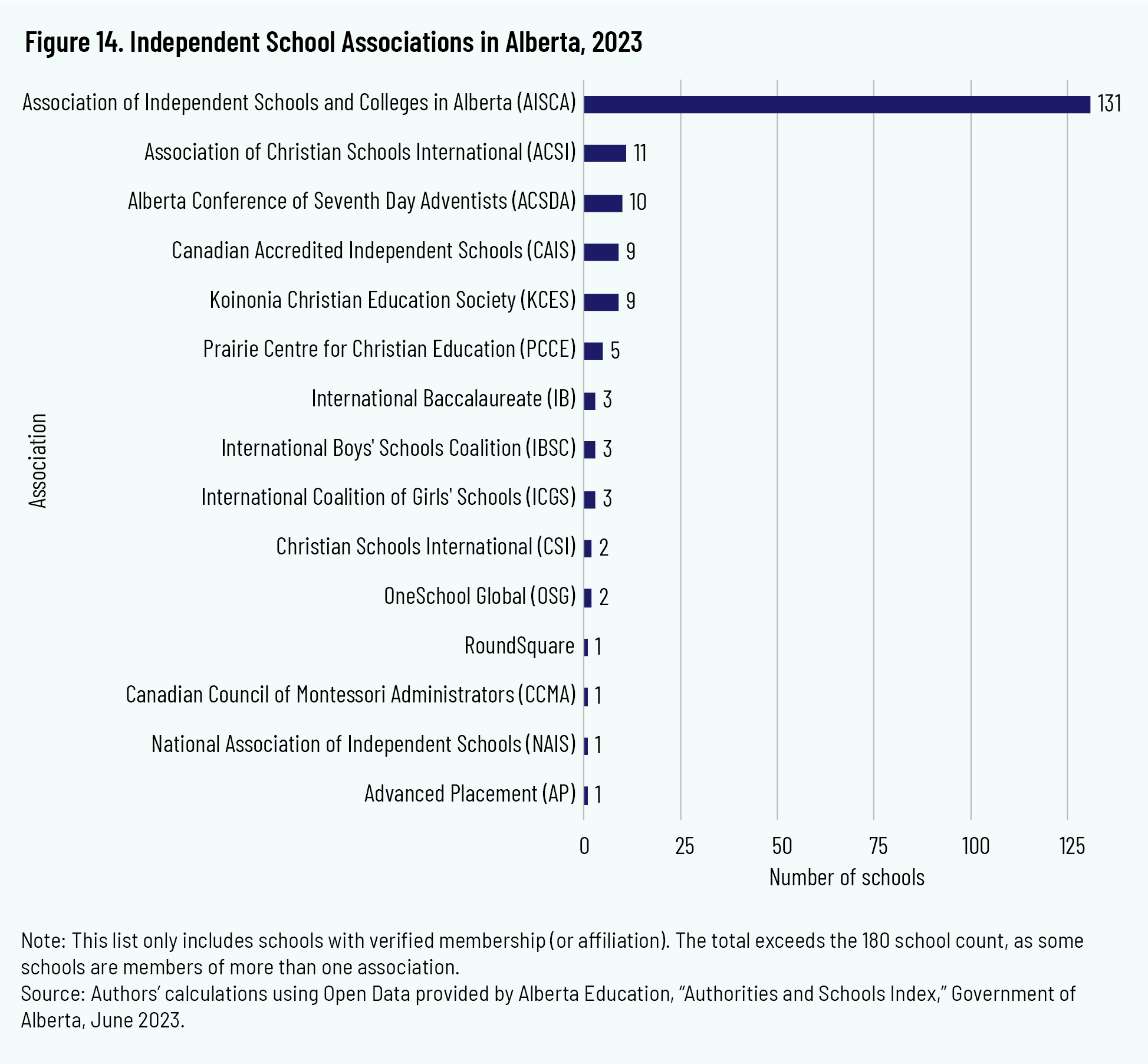

In total, fifteen associations were identified with which at least one independent school in Alberta claims a relationship. Some of these associations offer more than one level of relationship (“member,” “affiliate,” and so on), each of which has its own definition. The present study does not extend to examining this more granular level of relationship. For the five associations that operate a website and that have at least five Alberta member or affiliate schools, school relationship was verified from their web-based directories.

In total, 133 (73.9 percent) of Alberta’s 180 independent schools are members of a school association. Eighty-three (46.1 percent) belong to one school association, 50 (27.8 percent) belong to more than one, and forty-seven (26.1 percent) do not belong to any.

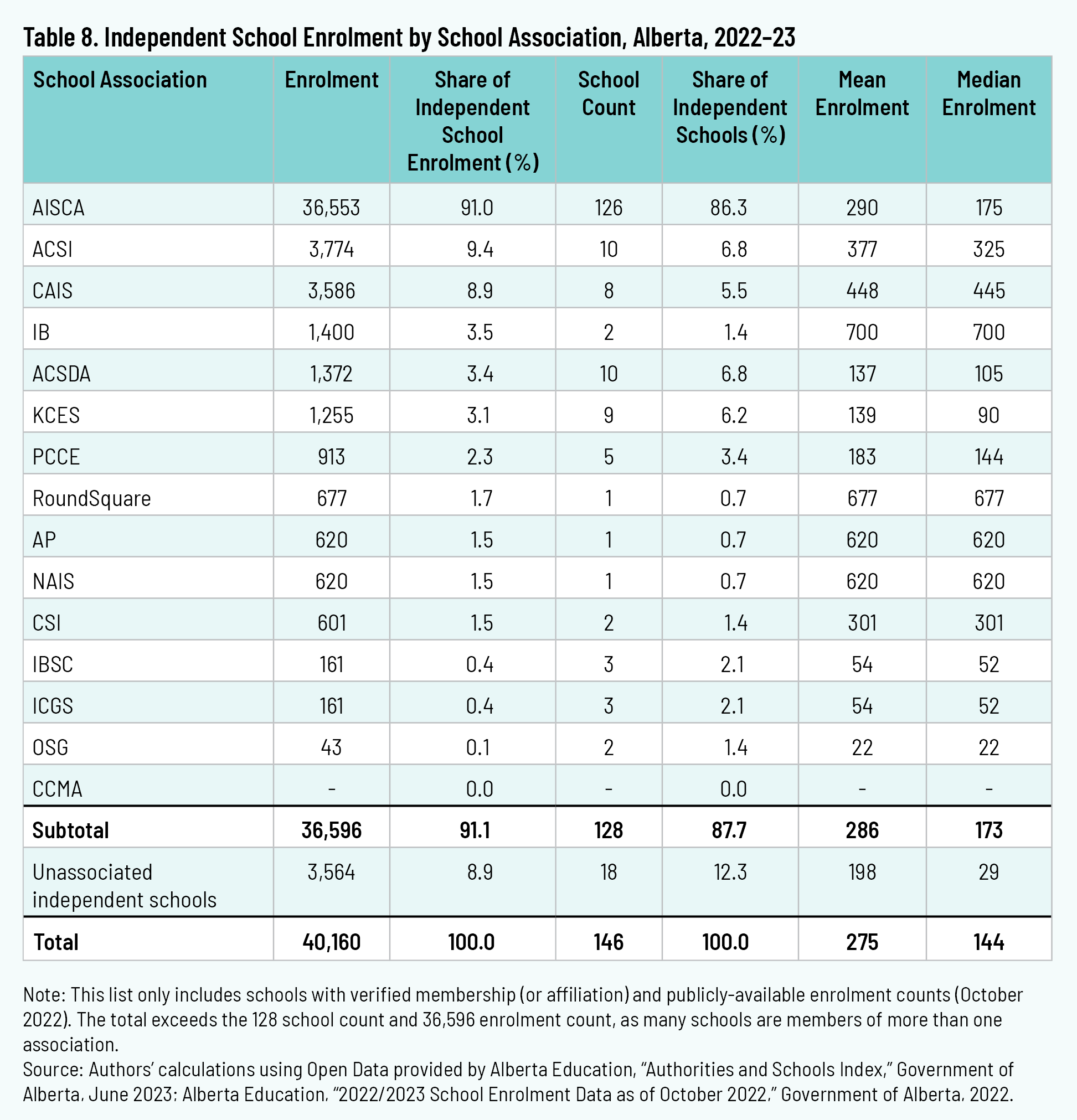

The Association of Independent Schools and Colleges in Alberta (AISCA) serves and represents 72.8 percent of all schools in the sector (figure 14), and 86.3 percent of the schools for which enrolment data are available (table 8). For context, of all schools that have membership in an association and for which enrolment data are available, all but two are members of AISCA. Fully 91 percent of the sector’s students are enrolled in an AISCA school. Every school that is a member of a non-AISCA association is also a member of AISCA.

By school type, of associations with at least five schools or 1,000 students, four consist entirely of Religious schools: Association of Christian Schools International, Alberta Conference of Seventh Day Adventists, Koinonia Christian Education Society, and the Prairie Centre for Christian Education. Two are exclusively Top Tier schools: Canadian Accredited Independent Schools and International Baccalaureate. The Association of Independent Schools and Colleges in Alberta is a mix of school types.

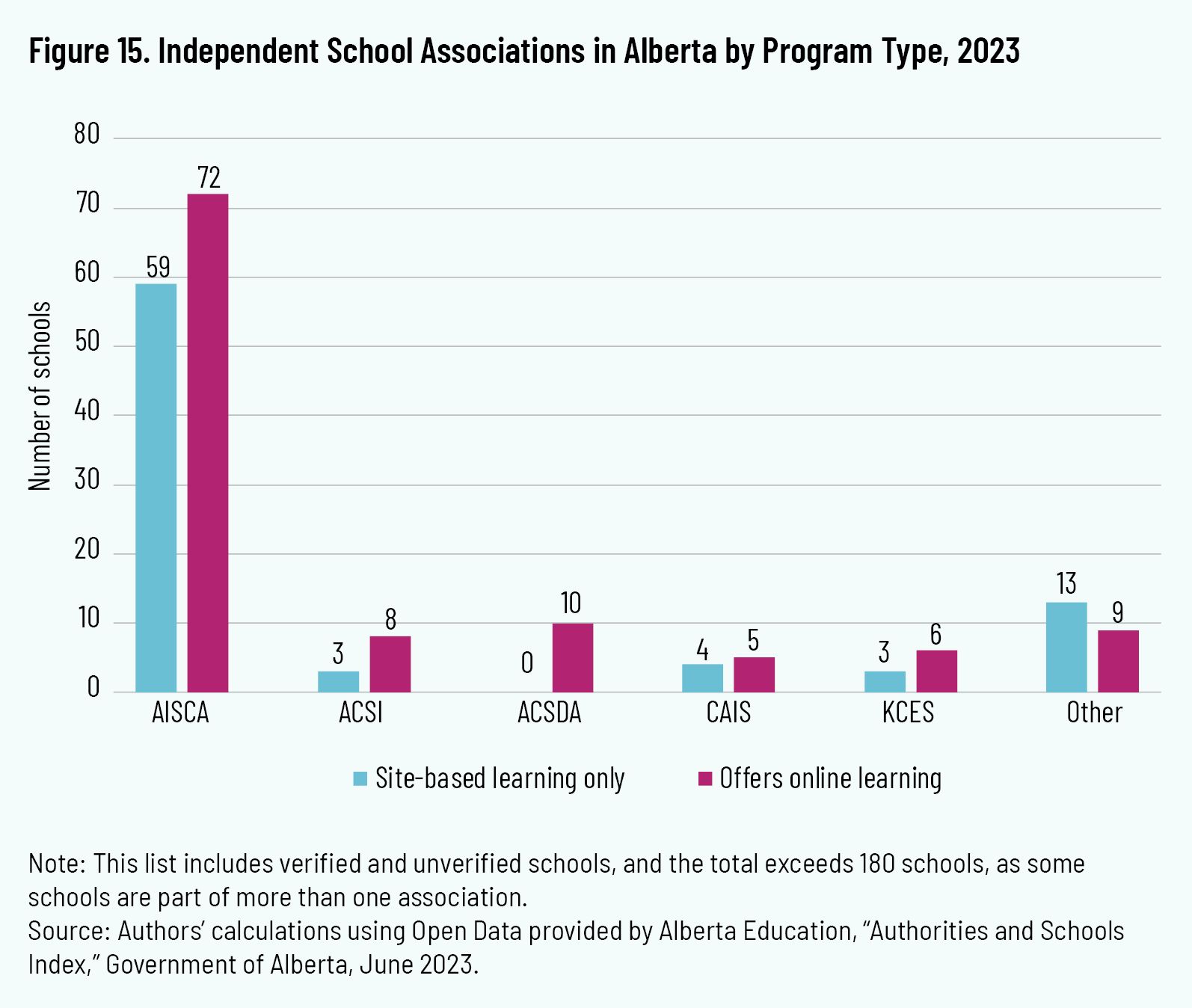

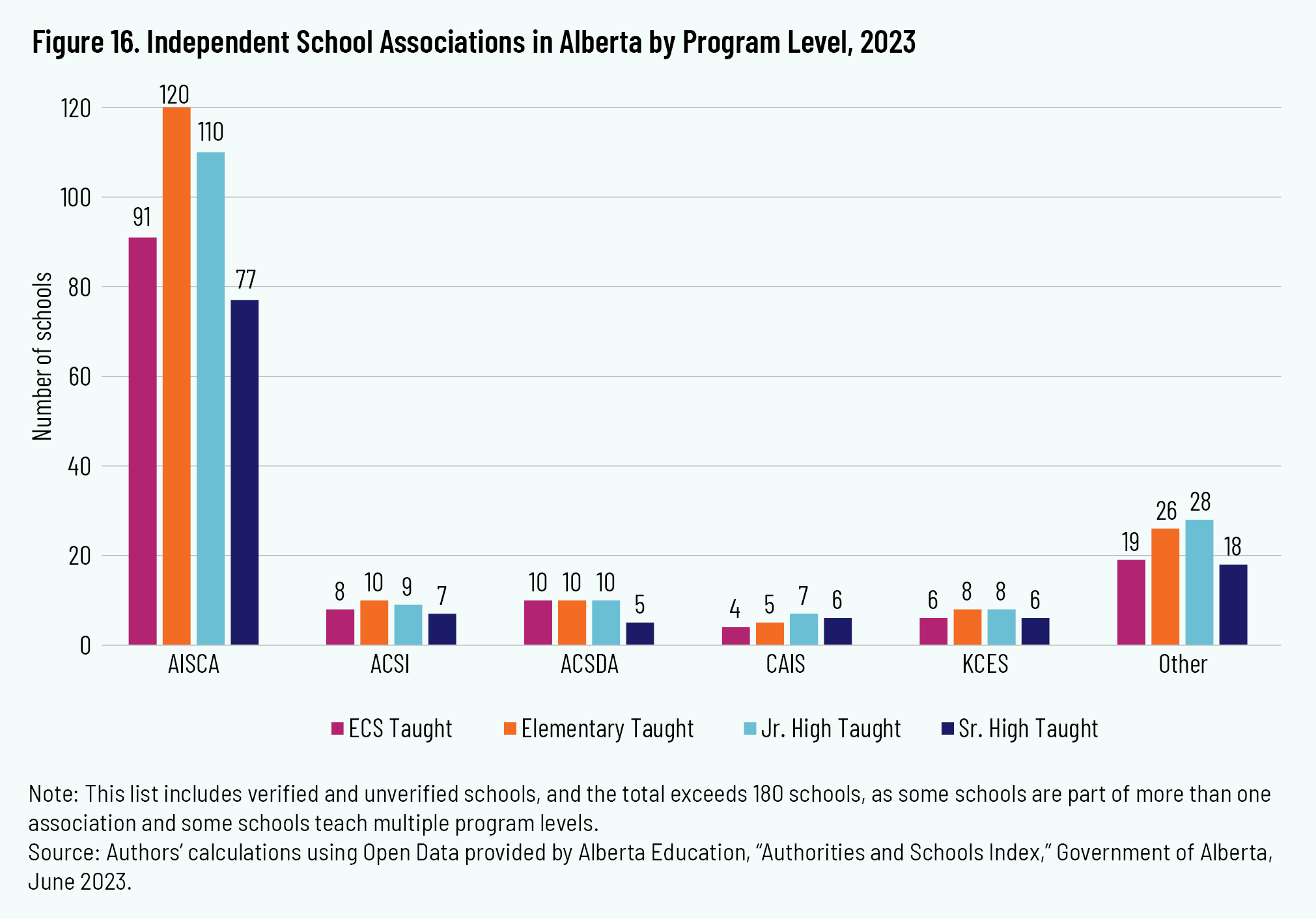

Figures 15 and 16 segment association relationship further, by school program type and program level. About half (54.9 percent) of AISCA schools offer online learning, and seventy-seven AISCA schools offer senior high courses.

Distribution by Geographic Location

There are several ways in which schools may be categorized geographically for meaningful distinctions and comparisons. Three methods are used in this study: sub-provincial region, population centre, and urbanicity.

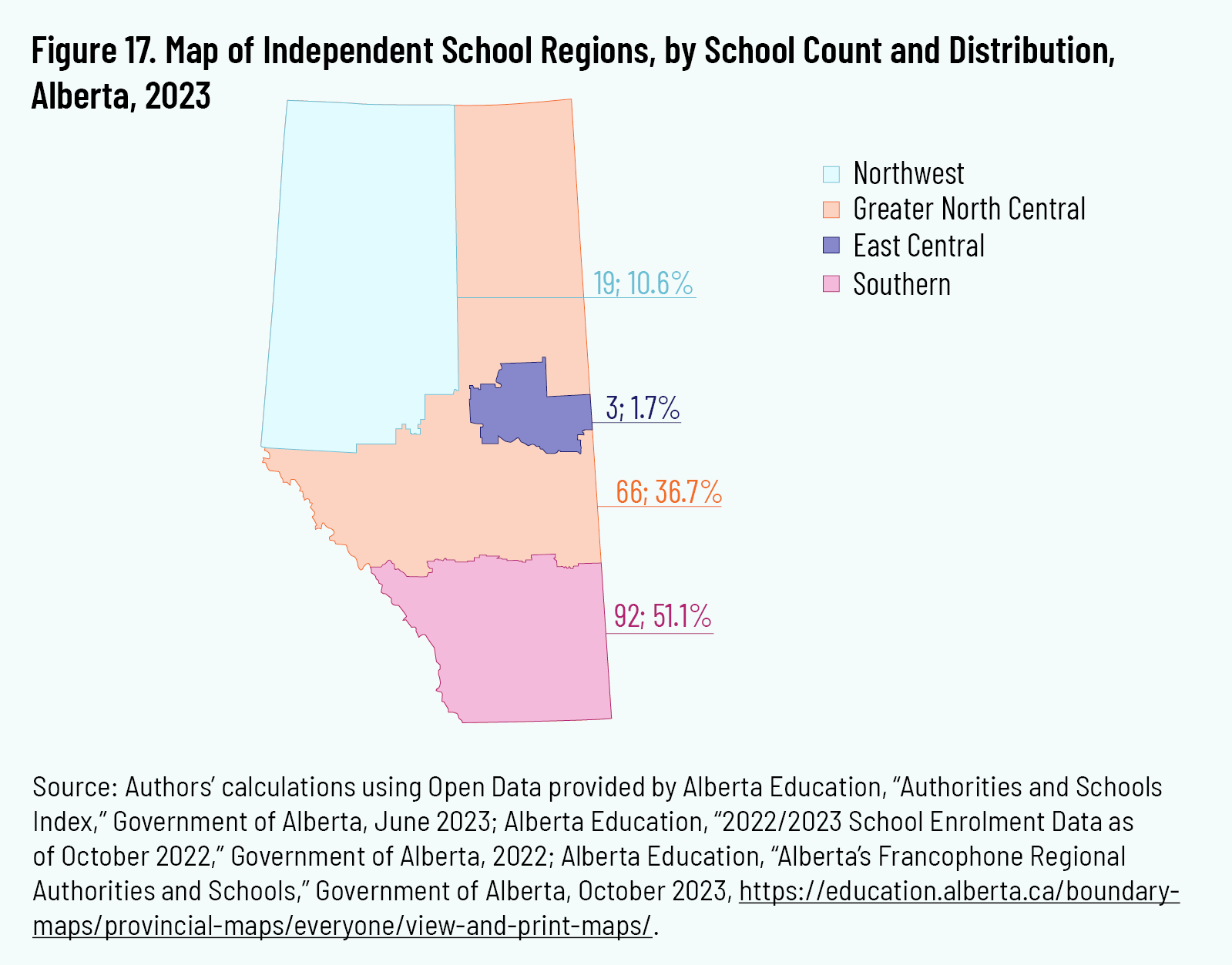

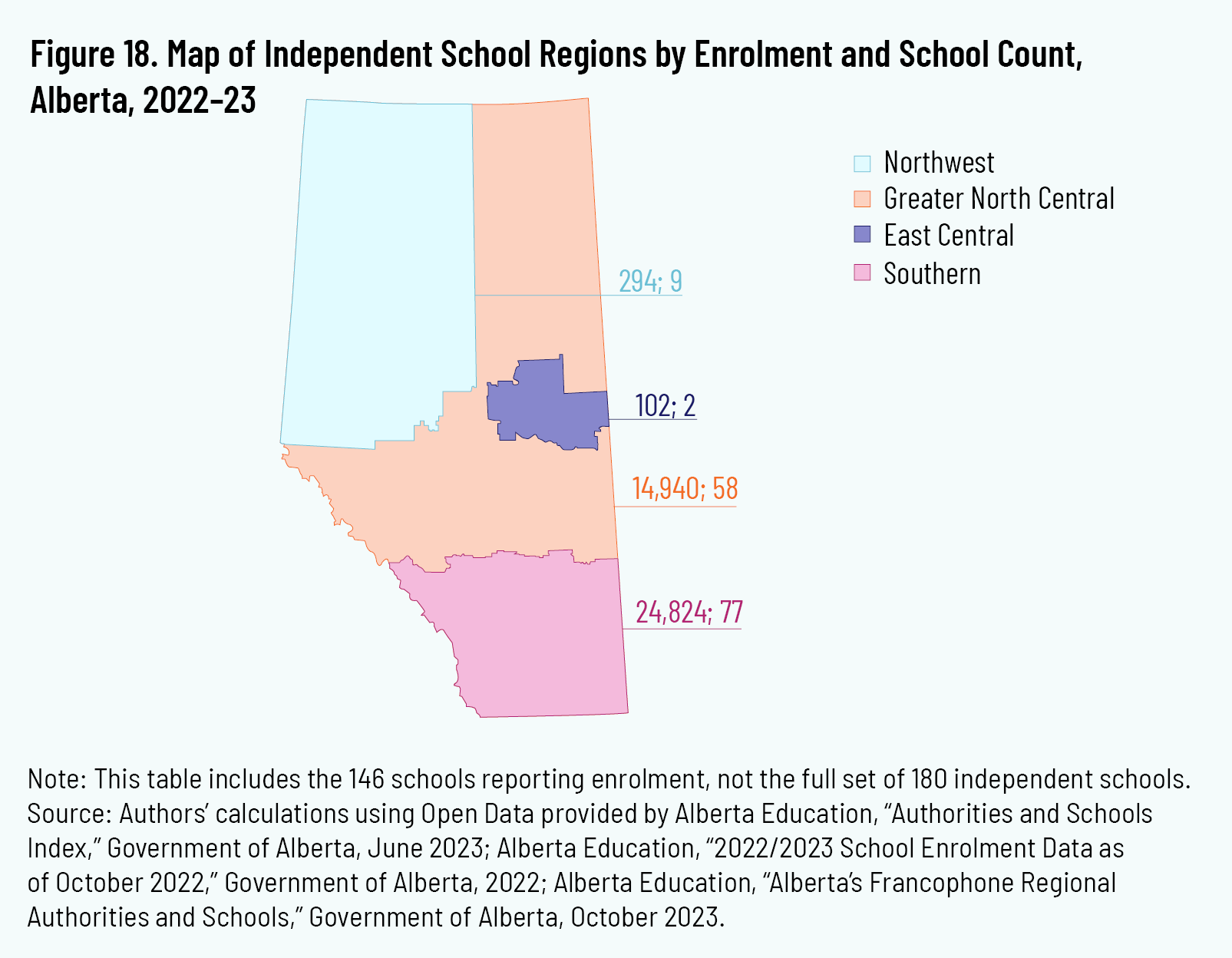

Region

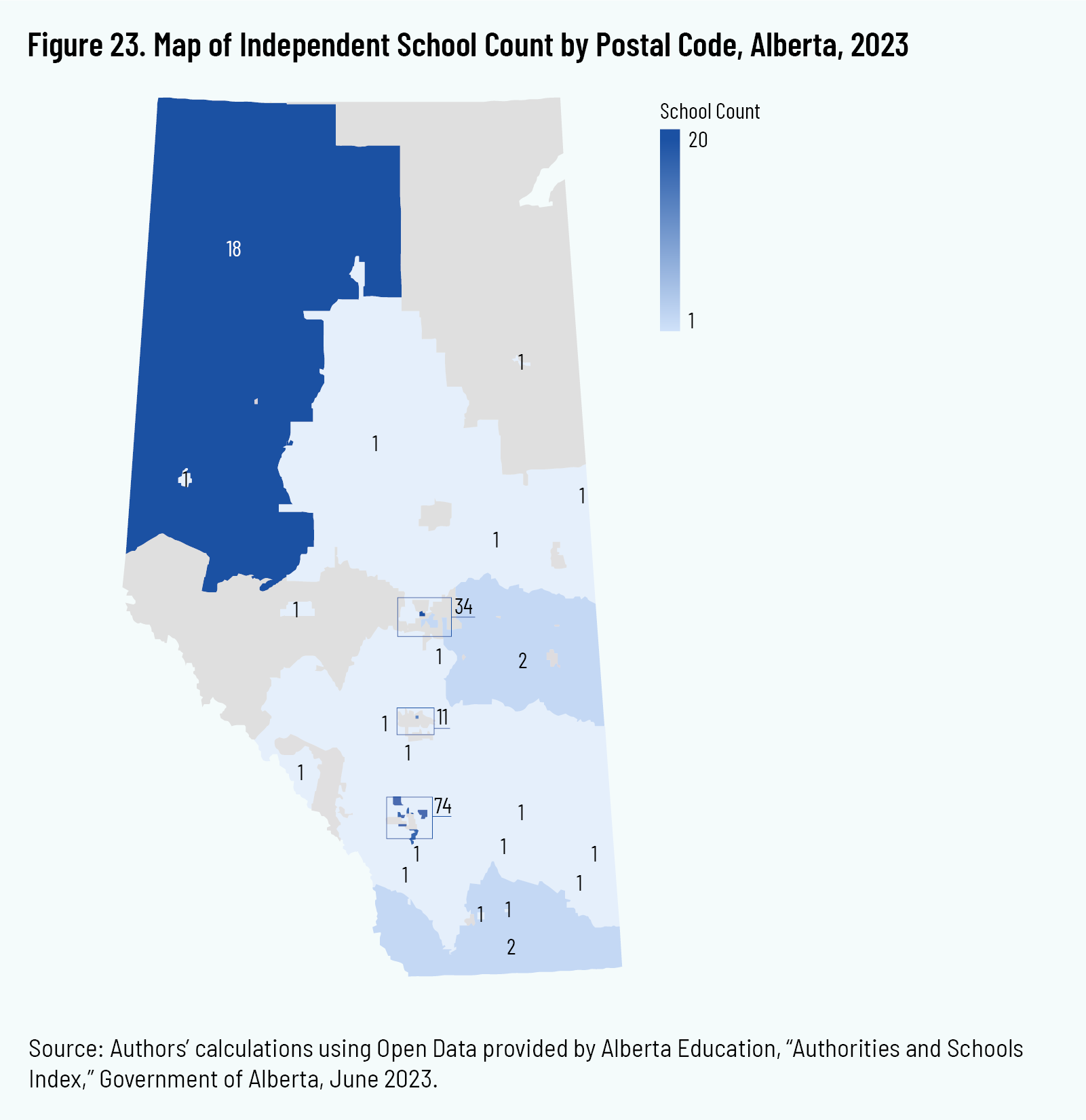

This research applies the four regional boundaries that Alberta Education uses for public (district), Francophone, and charter schools. 33 33 The map is available on the Alberta Education website, “Provincial Maps,” Government of Alberta, https://education.alberta.ca/boundary-maps/provincial-maps/. The June 2023 school count by region is shown in figure 17, and the 2022–23 enrolments are shown in figure 18. The Southern region accounts for roughly half of Alberta’s population, and its ninety-four independent schools reflect this, with 51.1 percent of schools in the sector. Yet Alberta’s largest independent schools are in the Southern region, and its 24,824 students are an outsized share of the sector, at 61.8 percent.

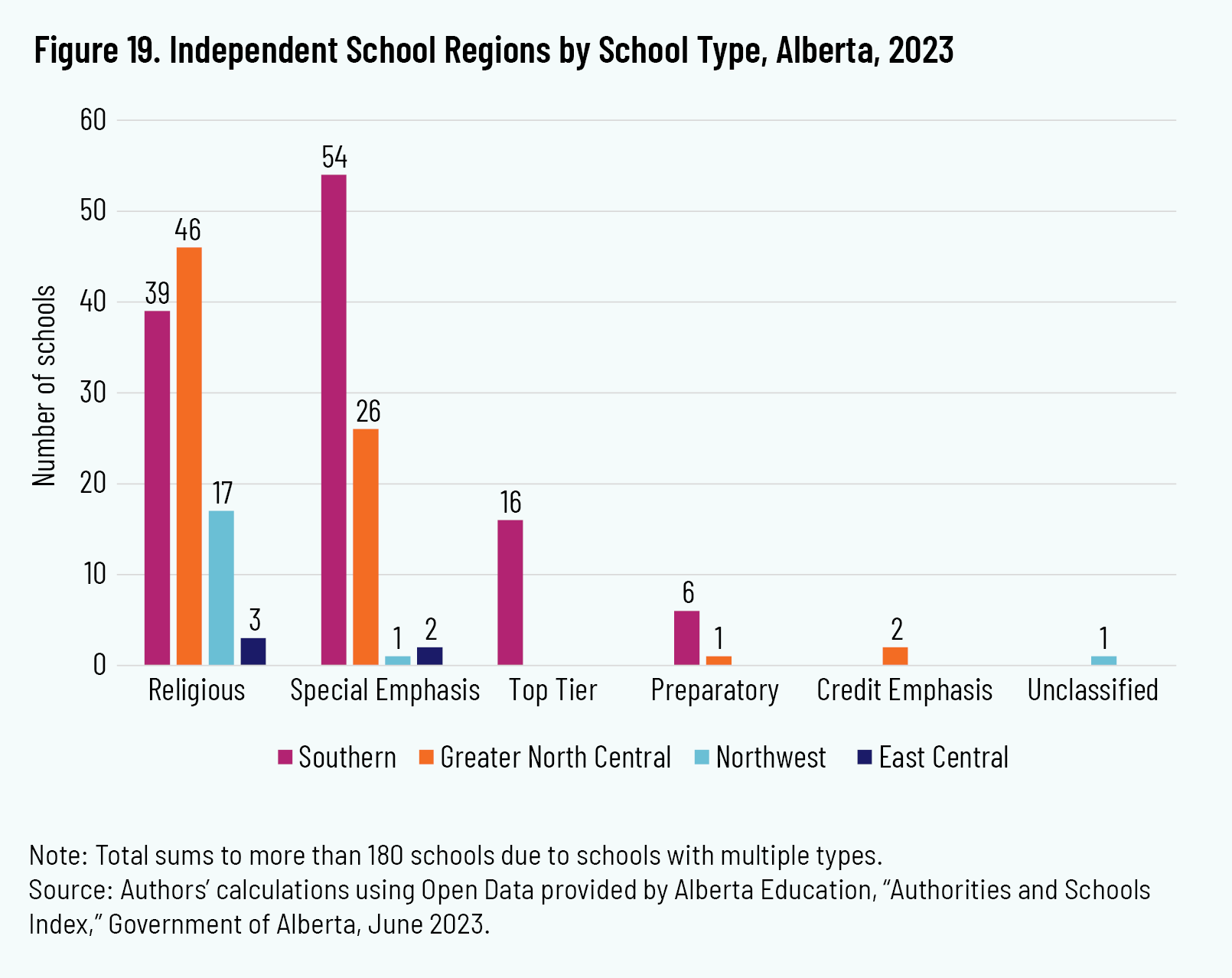

Nineteen schools (10.6 percent) are in the Northwest, despite this region making up only a small percent of the province’s population. Enrolments in the Northwest are underreported, however, as over two-thirds of the nineteen Northwest schools are Mennonite (Christian) and/or Parochial schools that do not report enrolments (figure 19).

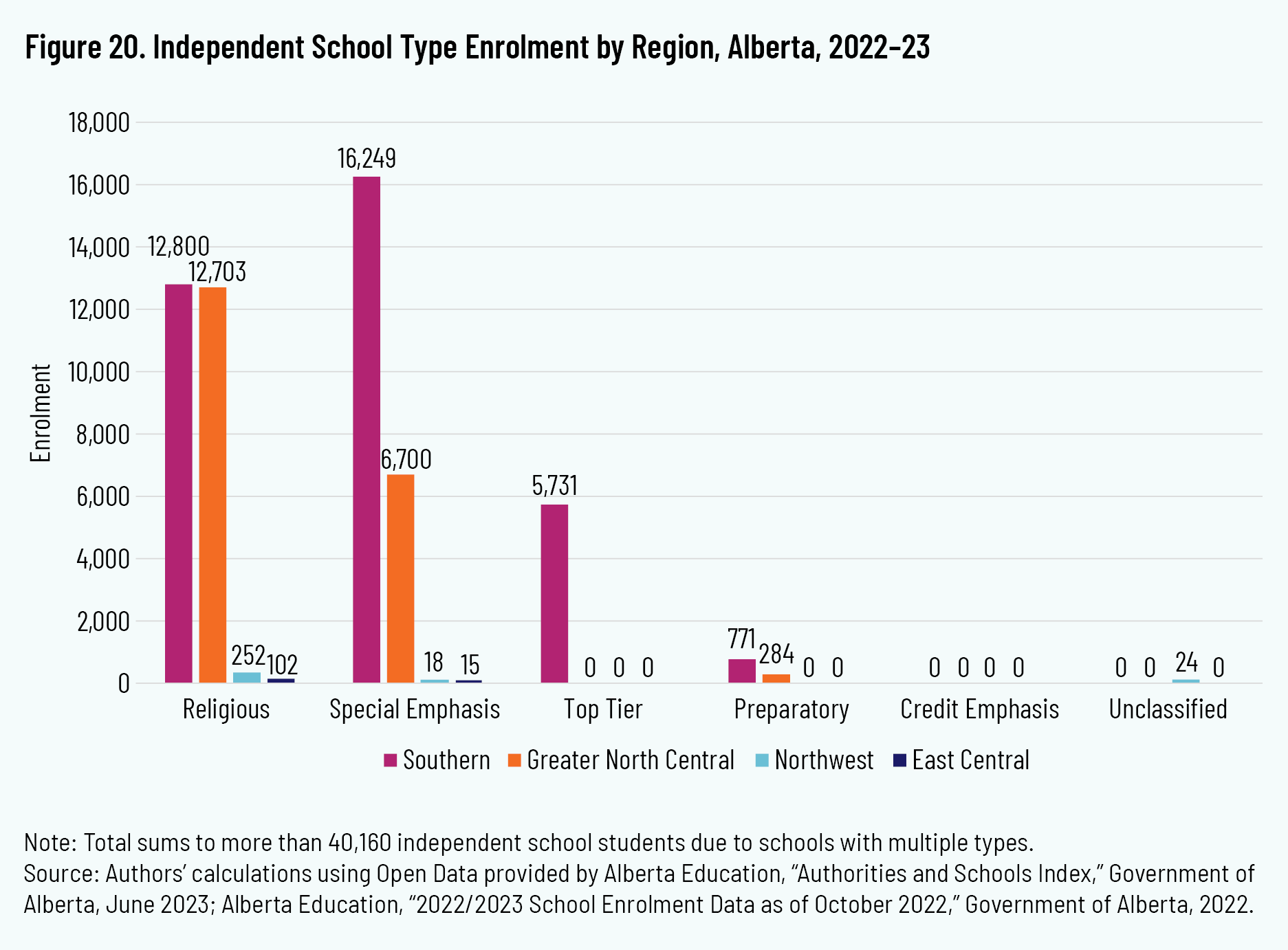

The regional distribution by school type is particularly interesting. Forty-six (61.3 percent) of the schools in the Greater North Central region are Religious schools. Similarly, seventeen (89.5 percent) of the schools in the Northwest and three (60 percent) in East Central are Religious. Conversely, just one-third of the schools in the Southern region are Religious. All of the province’s schools typed Top Tier and Preparatory, and nearly two-thirds (65.0 percent) of those typed Special Emphasis, are in the Southern region (figure 20 and 21). The Special Emphasis schools in this region include all of Alberta’s IB, Experiential, and Arts, Sports, or STEM schools (figure 22).

Population Centre

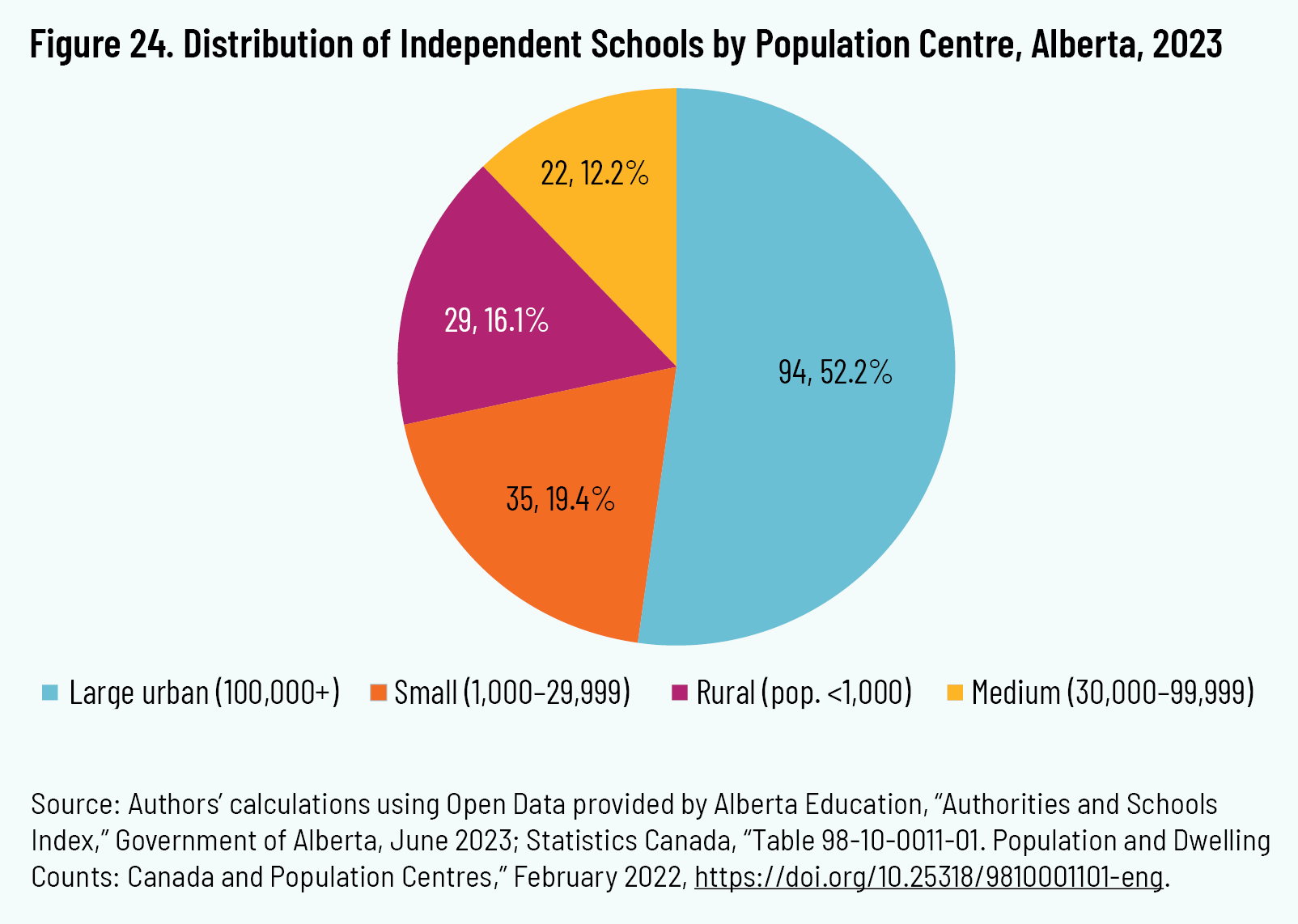

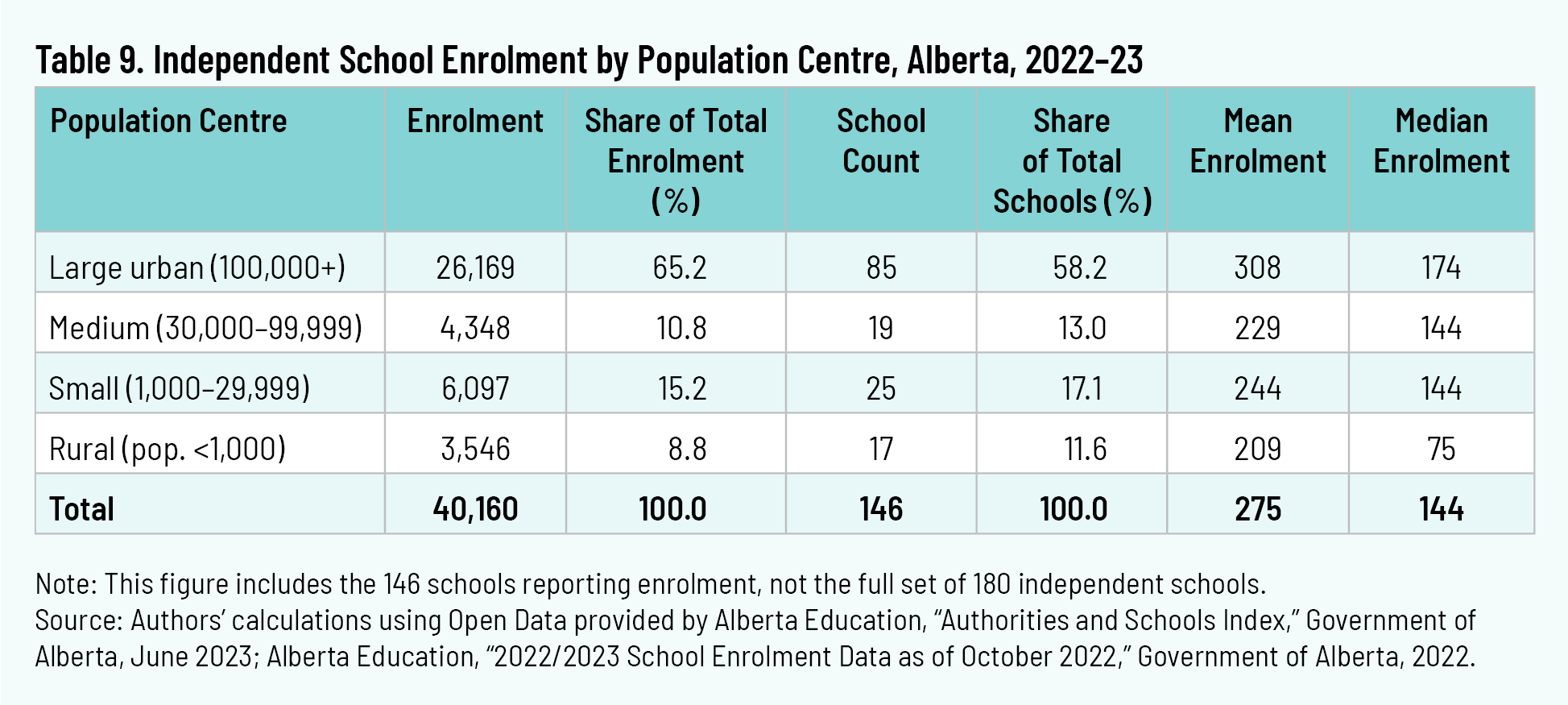

Using Statistics Canada data from the 2021 Census, population-centre data were retrieved and matched with the school’s city according to definitions outlined in the Census Dictionary. 34 34 Statistics Canada, “Dictionary, Census Population, 2016,” October 11, 2018, 94, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/ref/dict/98-301-x2016001-eng.pdf. A “population centre” is defined as having a density of 400 persons or greater per square kilometre and at least 1,000 persons within its boundary. Population centres of 1,000 to 29,999 persons were considered small, those with 30,000 to 99,999 persons were considered medium, and those with 100,000 persons or more were considered large. Regions outside of population centres were categorized as rural.

Figure 23 maps the schools by postal code. It is interesting to see the visual contrast between Alberta’s two major cities. The Calgary metropolitan area (including Airdrie, Cochrane, and Okotoks) has more than double the number of schools as similar-population Edmonton (including Devon, Spruce Grove, and Stony Plain). Many of the rural and small town schools do not show up on the map, but those that are visible reveal distribution across the province.

Fully 52 percent of the schools (figure 24) and 65.2 percent of the enrolment (table 9) are in large population centres, compared to 47.8 percent of schools and 34.9 percent of enrolment in rural, small, and medium population centres combined.

Urbanicity

There are limitations to population-centre classifications. If the purpose of coding schools by geography is to assess whether independent schools serve an urban elite, surely population-centre classifications alone are insufficient. They tell us little about the kind of neighbourhood in which the schools are located, and the neighbourhood surely affects the nature of schools and who attends them—even if families commute to attend. Moreover, boundaries can and do get redrawn, even in neighbourhoods where the population or nature of its social and economic activity have not substantively changed. 35 35 M. Turcotte, “Life in Metropolitan Areas,” Statistics Canada, April 2014, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-008-x/2008001/article/10459-eng.htm. Therefore, urbanicity was also studied, that is, the nature of the urban/suburban environment that the school is located in, taking into account factors such as the degree of density and modes of transportation available.

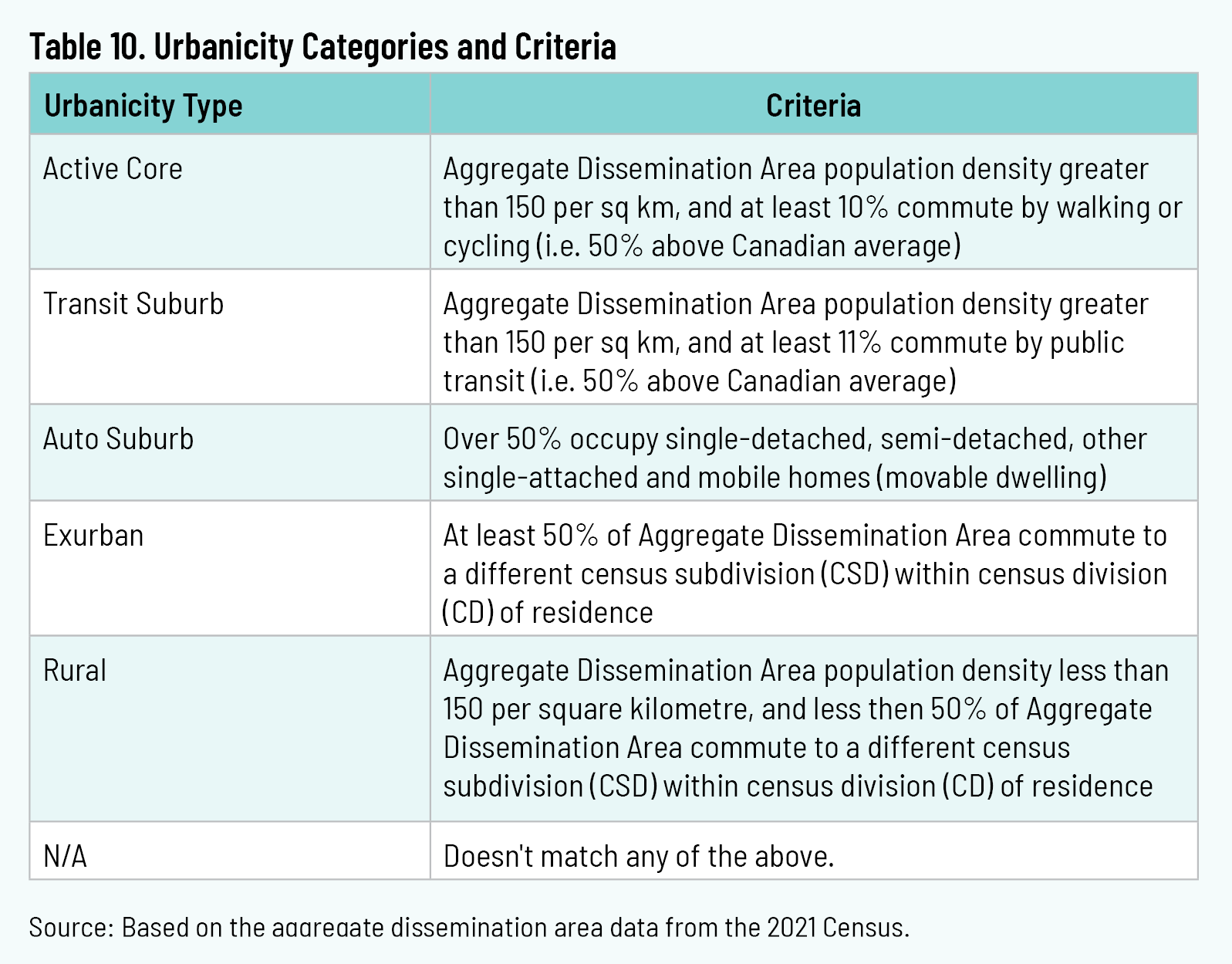

To code schools by urbanicity, David Gordon and Mark Janzen’s classifications 36 36 D.L.A. Gordon and M. Janzen, “Suburban Nation? Estimating the Size of Canada’s Suburban Population,” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 30, no. 3 (2013): 197–220, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43031005. were adopted and then modified, as displayed in table 10. To apply this typology to the entire province, including areas outside census metropolitan areas, schools’ urbanicity was coded by postal code, based on each school’s Aggregate Dissemination Area data. 37 37 Statistics Canada, “Census of Population, 2021,” September 12, 2023, https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm. The postal code of each school was used to find its relevant aggregate dissemination area and then sorted for its “mode of transportation” and “household and dwelling characteristics.” To determine the dwelling type, a combination of each structural type of dwelling was divided by the total occupied dwelling type. Modes of transportation were combined according to their definitions and divided by the total mode of transportation. The outputs of each dwelling type and journey-to-work together were used to calculate the urbanicity. To verify the classification of each school’s neighbourhood and test urbanicity definitions, a qualitative assessment of the schools’ surroundings was completed using Google Maps (or equivalent).

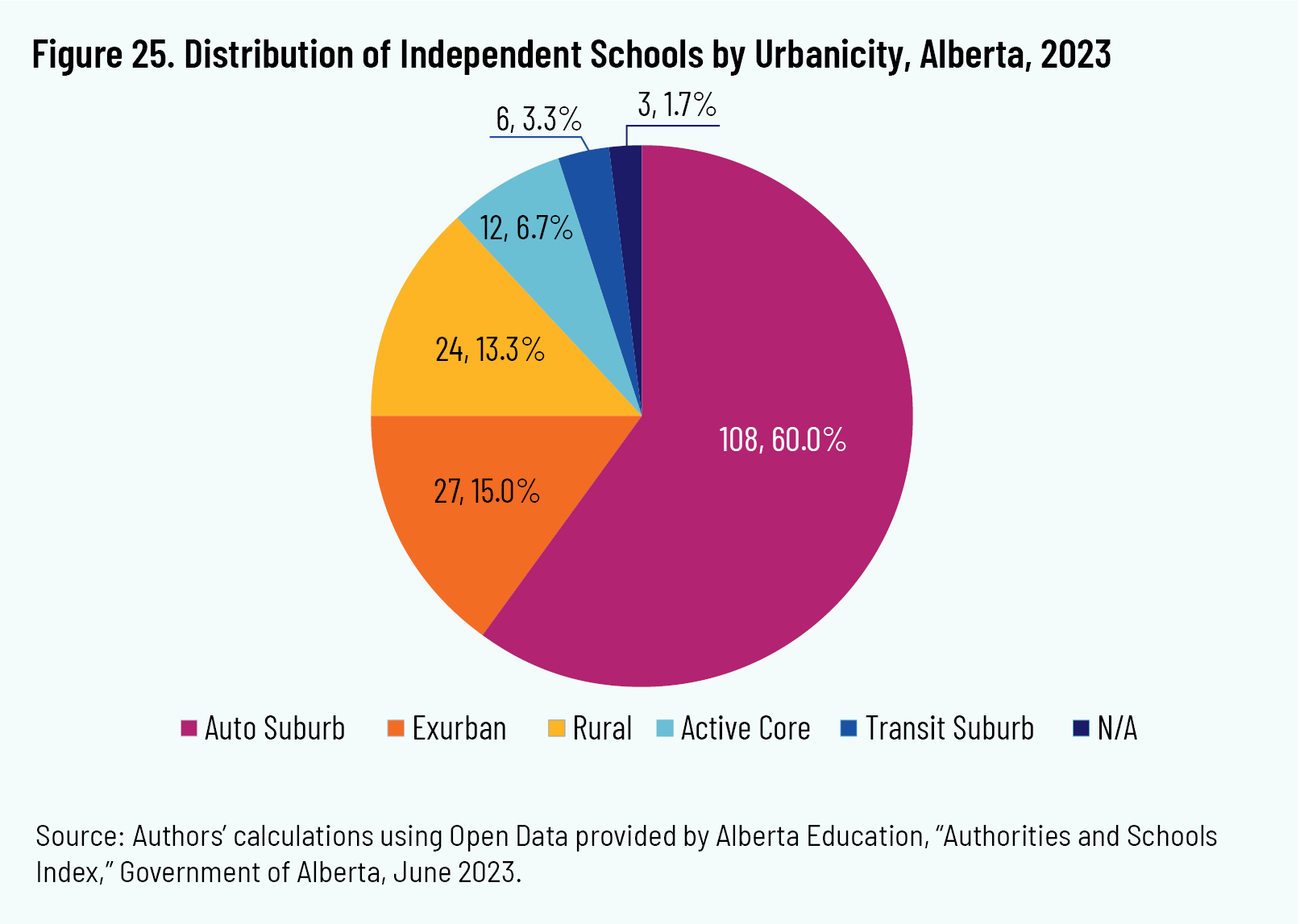

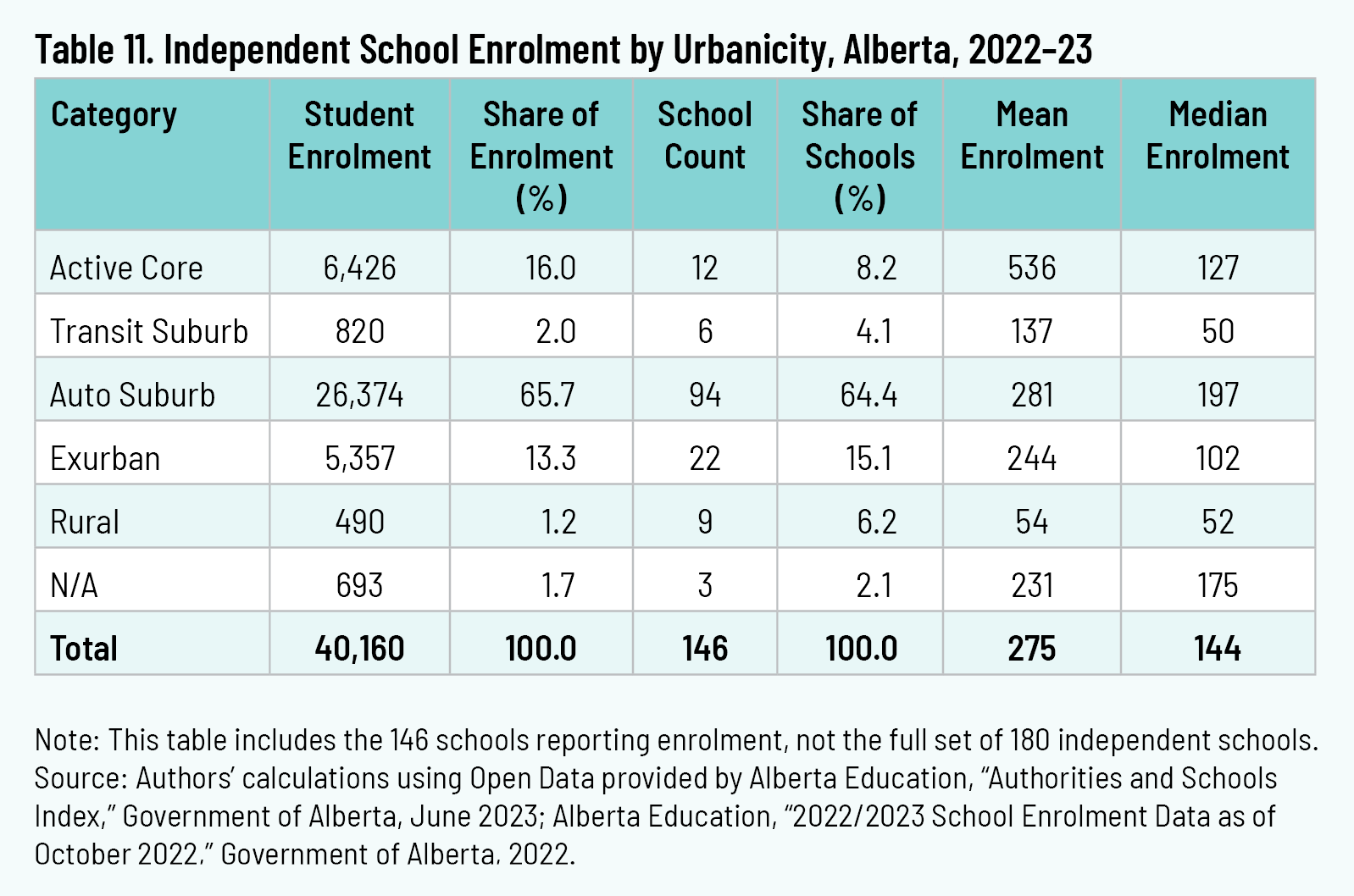

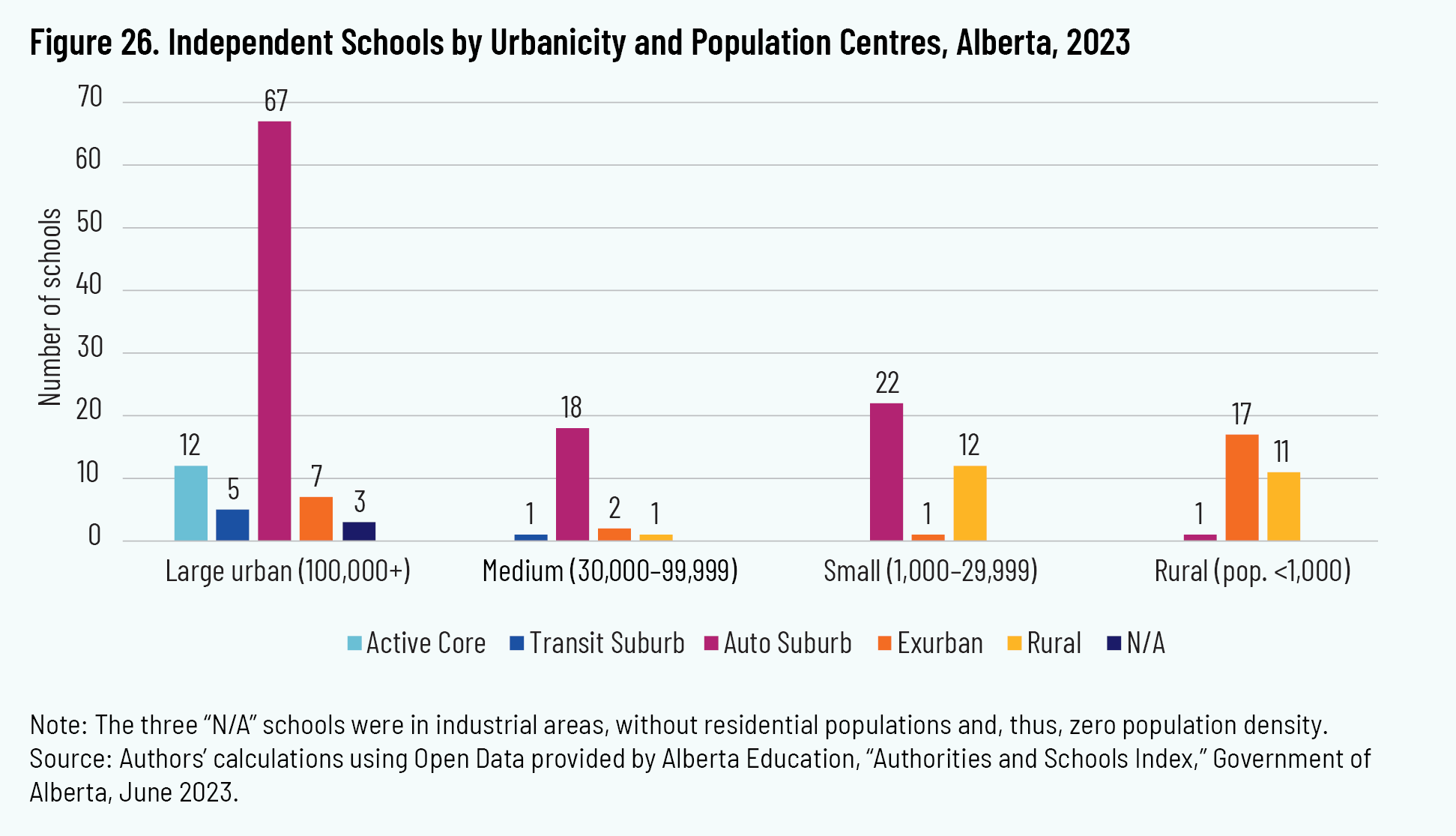

Figure 25 presents an overview of the urbanicity of the sector’s schools. Ninety percent fall into one of two groups: exactly 60 percent are in Auto Suburbs, and nearly 30 percent are in Rural or Exurban areas. Table 11 reveals this distribution by enrolment. Nearly two-thirds of the students attend schools in Auto Suburbs. Despite their low count, however, schools in Active Cores are nearly twice the size of the average school in the sector, with 16 percent of the enrolment. (Due to Mennonite/Parochial schools not reporting enrolments, Rural numbers are underrepresented).

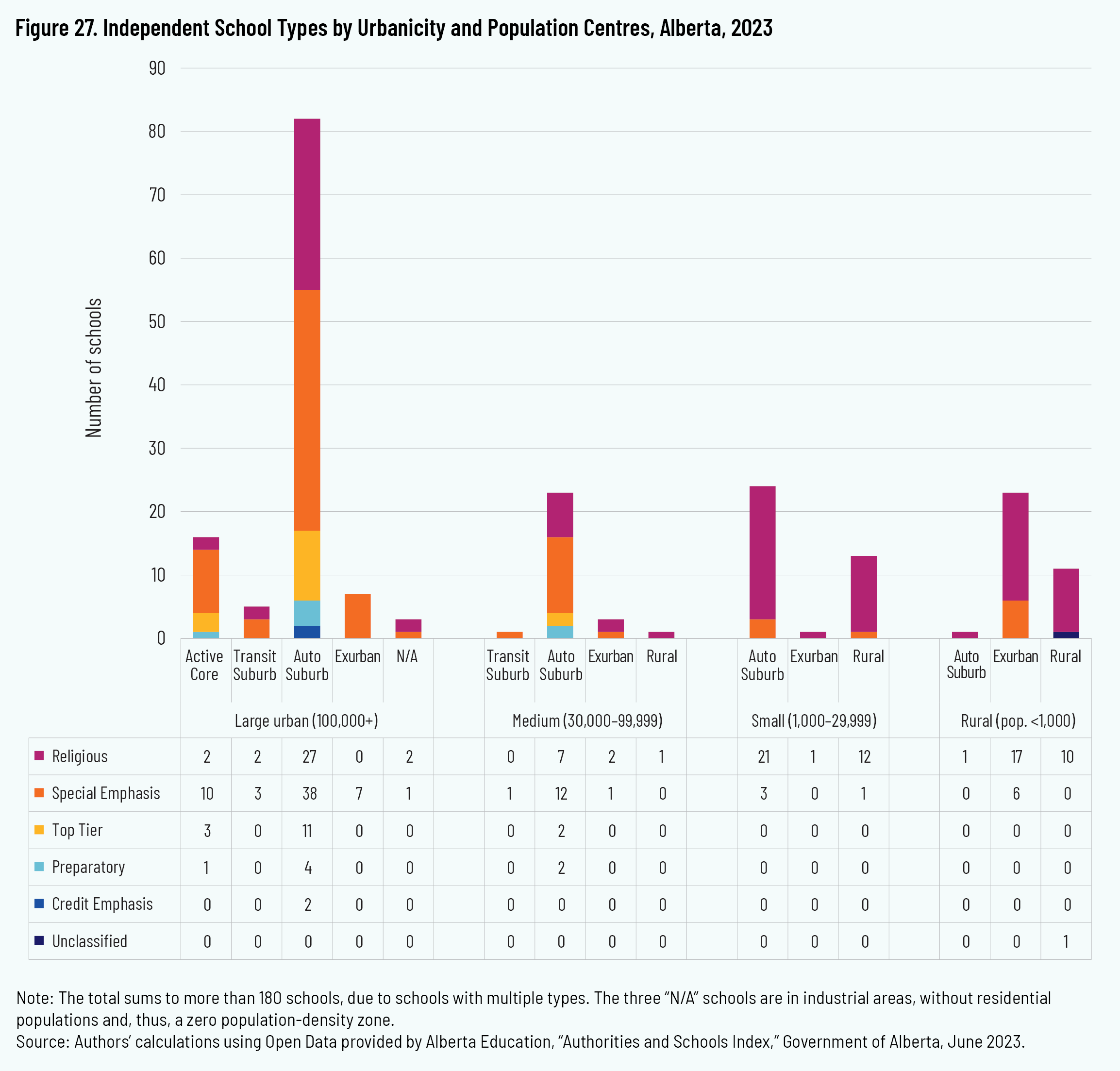

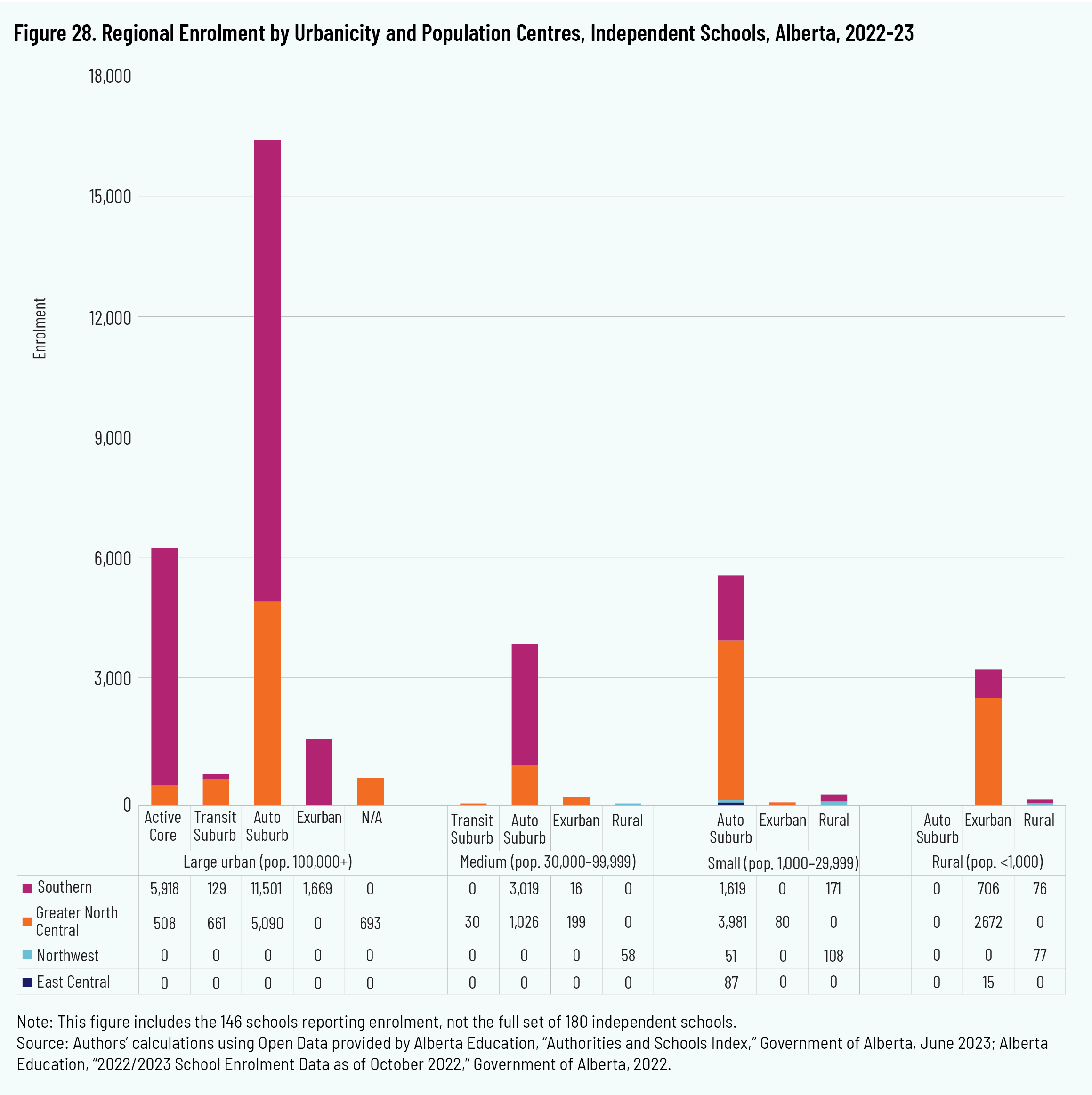

Cross-tabulating population centres with urbanicity, figure 26 shows that only twelve schools (6.7 percent) are in the Active Cores of large urban centres. Of these, three are Top Tier (figure 27). There are nearly the same number of independent schools in “Rural, Rural” Alberta as there are in the Active Cores of large urban centres. The great majority of Alberta’s independent schools and enrolments are in Auto Suburban neighbourhoods (figures 27 and 28).

Change Over Time

Allison, Hasan, and VanPelt charted the independent school landscape across Canada using data from 2013–14, which was used in the present study to make like-to-like comparisons between then and now. It is worth noting that some of the growth may be because schools in the present study are identified with multiple categories, whereas Allison, Hasan, and Van Pelt grouped each schools into just one category. Thus it is possible that the 2013–14 numbers are understated. Also, it is unknown whether heritage-language schools were included or excluded (the present study excludes them).

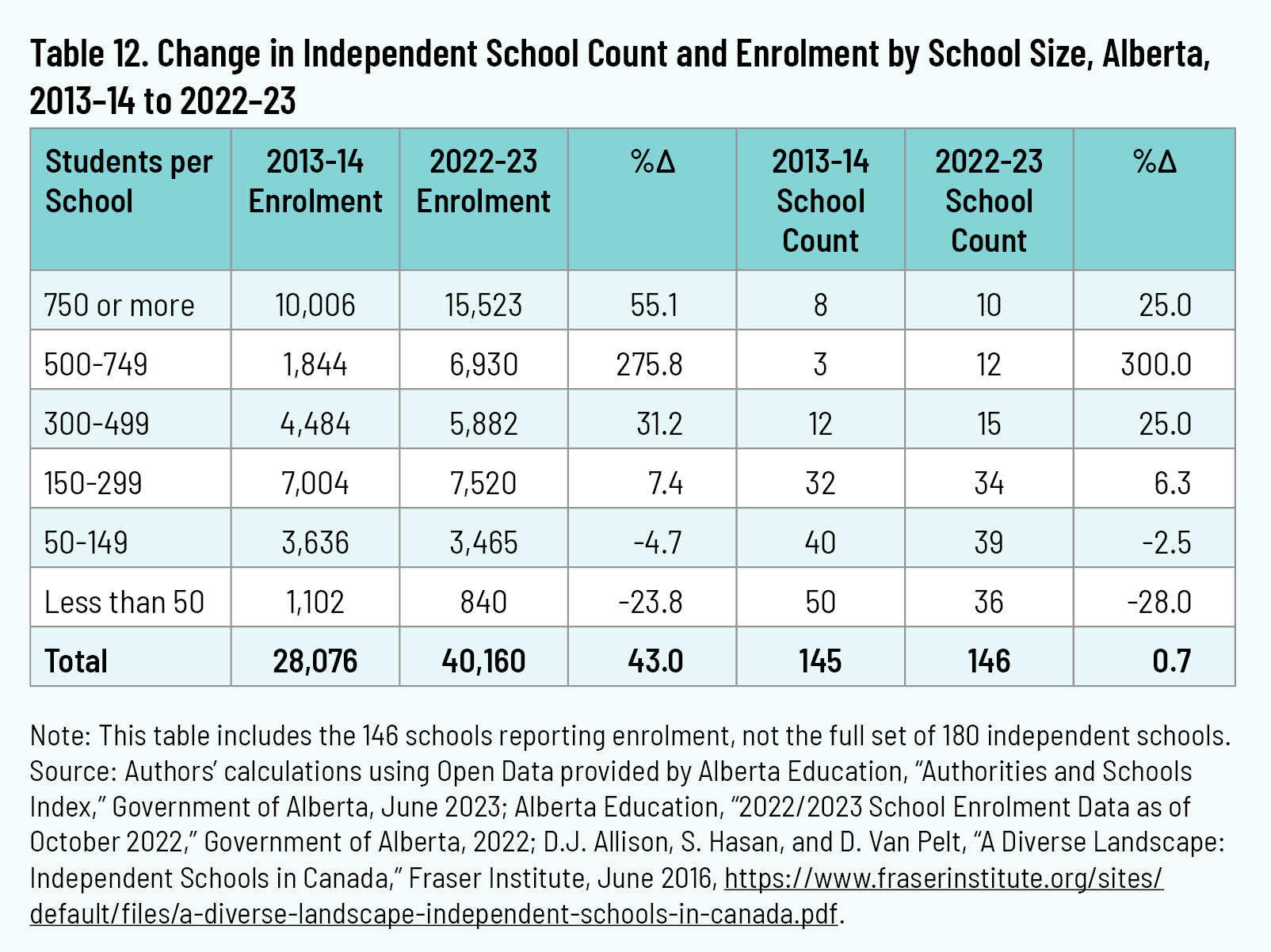

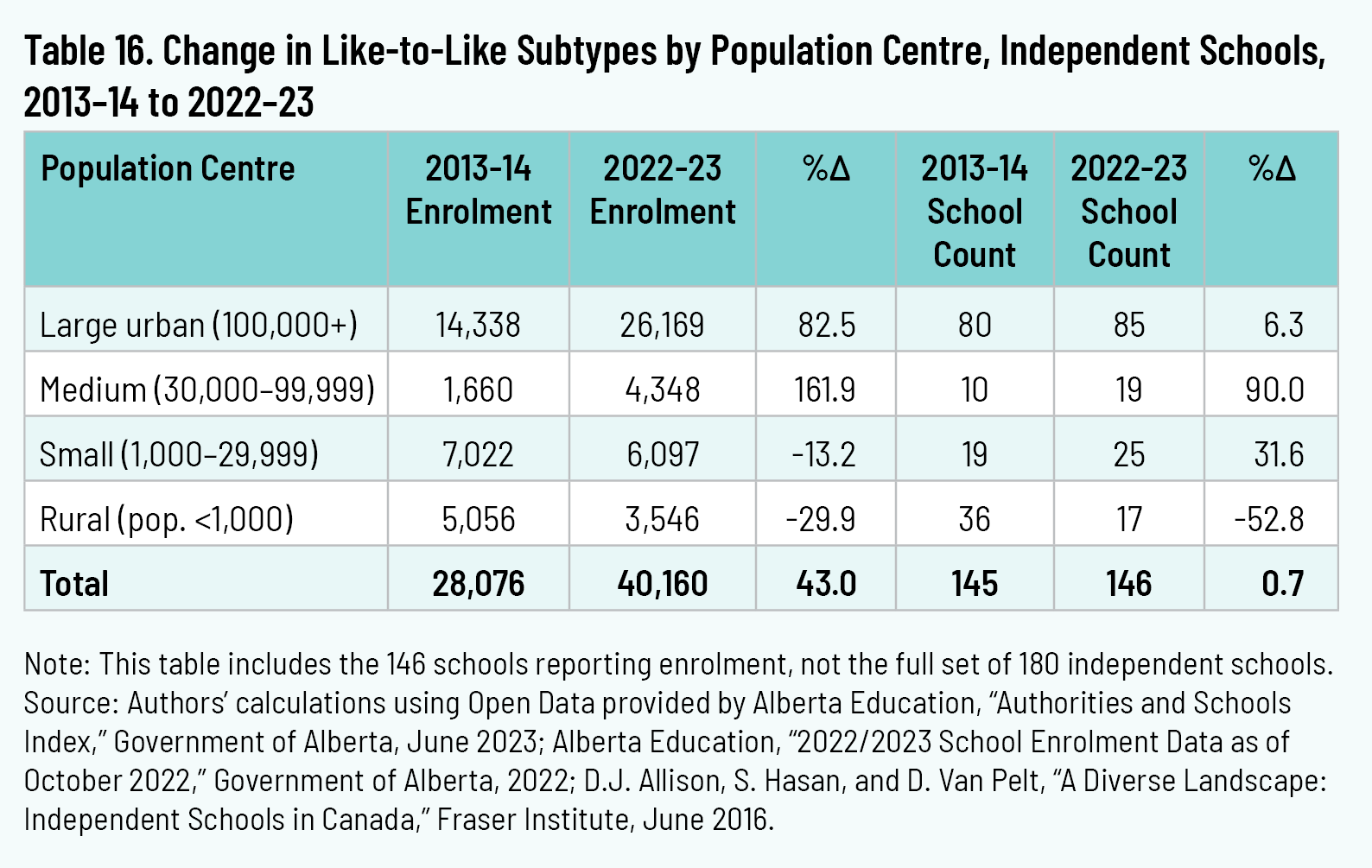

Change in School Count and Enrolment by School Size

Table 12 charts the change in school count and enrolment by school size, from 2013–14 to 2022–23. While school count has remained almost unchanged (just one net new school over ten years), enrolment has increased by 43.0 percent. When the breakdown by school size is considered, it can be seen that the number of schools with fewer than fifty students have decreased over time. There were fifty schools in 2013–14, and thirty-six in 2022–23. Schools with 500 or more student have increased, from three schools in 2013–14 to twelve in 2022–23. There are two additional schools in the over 750 enrolment category. This suggests that the increase in enrolment in the sector is due not to new schools being opened but to existing schools becoming larger.

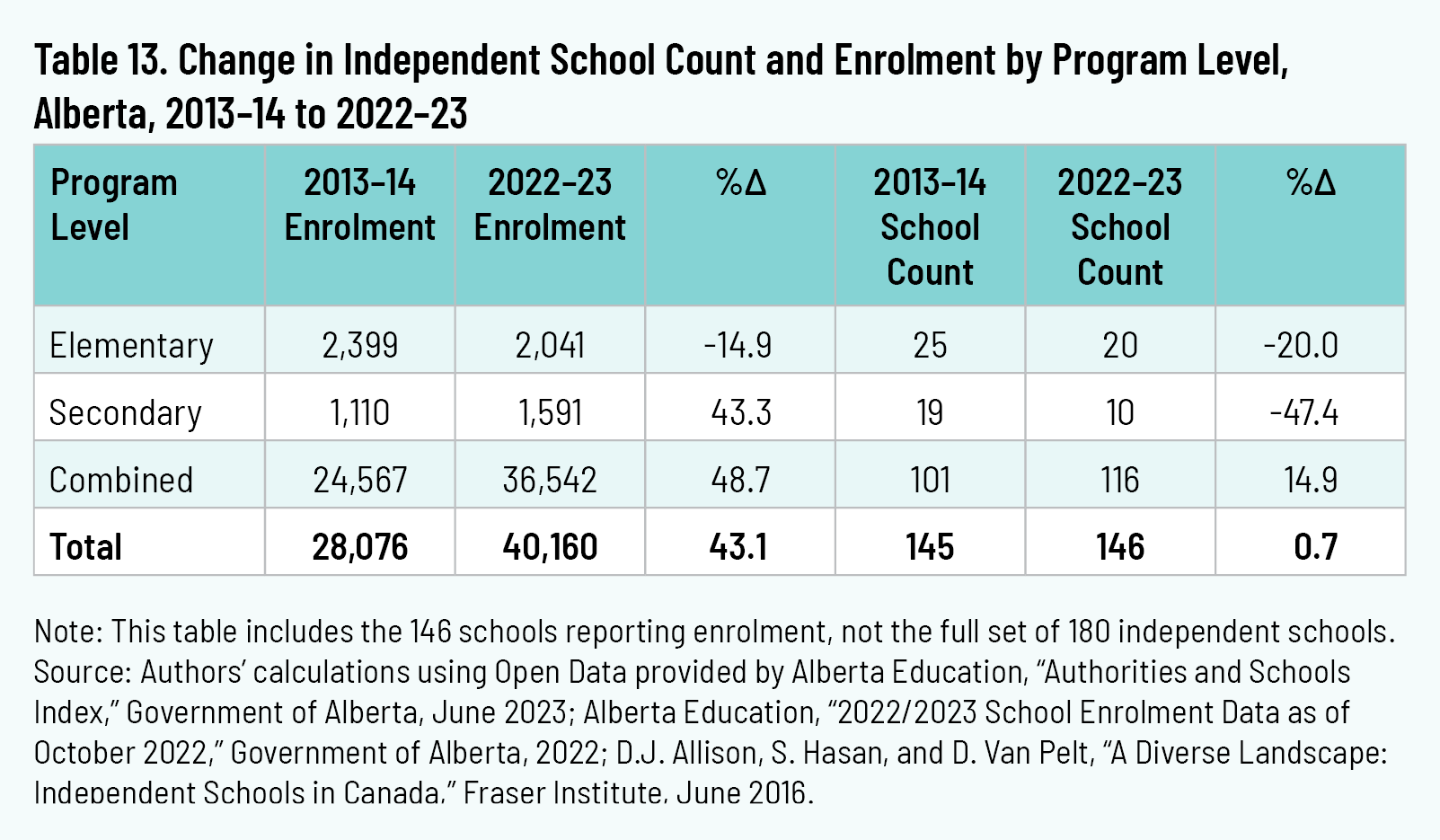

Change in School Count and Enrolment by Program Level

The change in school count and enrolment by program level is collapsed into elementary, secondary, and combined levels in table 13, to enable comparison with 2013–14. The largest change in enrolment is in combined program levels, or schools that offer a K–12 curriculum, with enrolment increasing 48.7 percent, and school count increasing by 14.9 percent. Over the same period, the number of and enrolment in elementary schools decreased. And while secondary school enrolment increased from 1,100 to almost 1,600 students, the number of secondary schools decreased. The significant increase in combined K–12 programs is another possible indicator of growth within schools rather than new school starts.

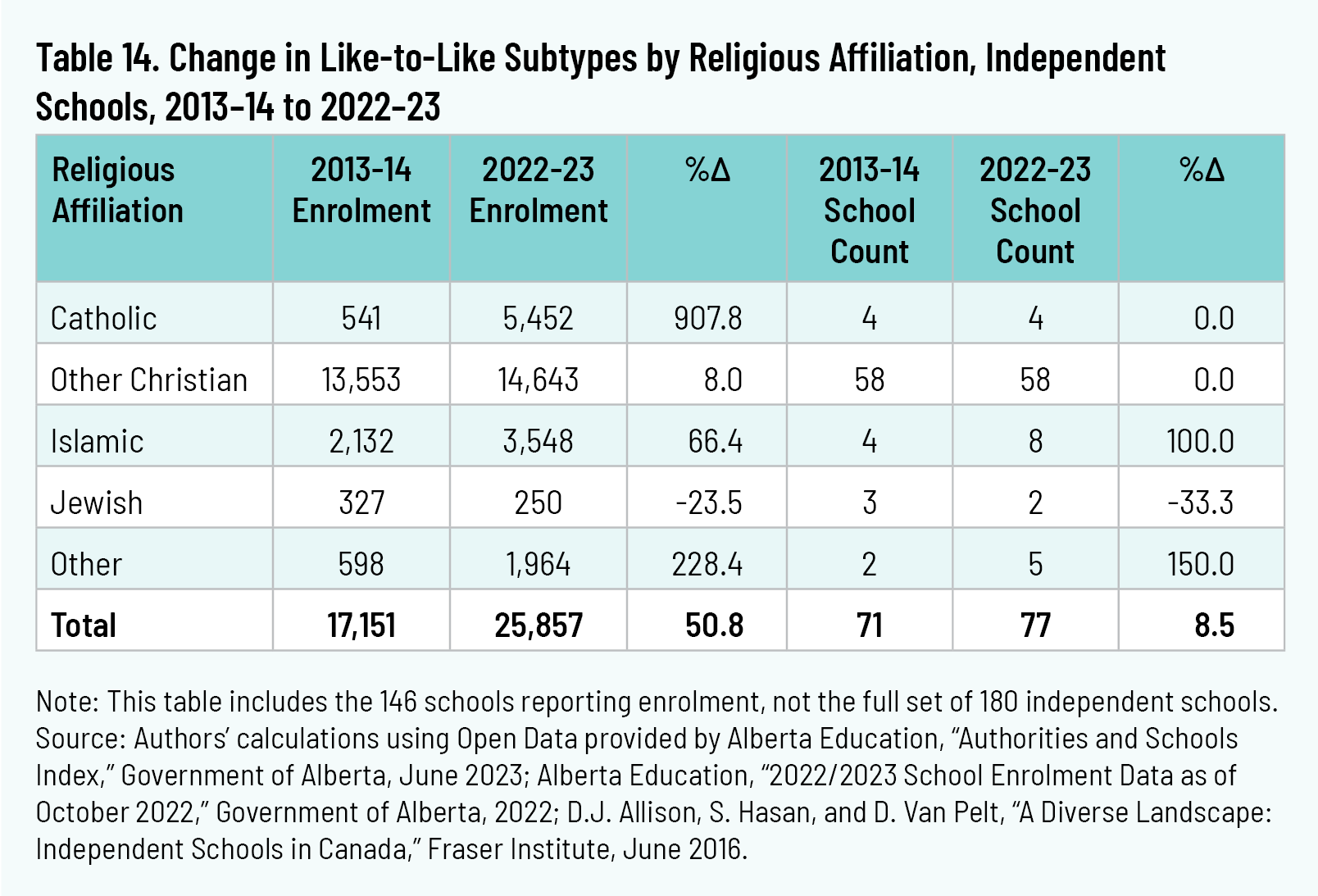

Change in School Count and Enrolment by Religious Subtype

The change in Religious schools is worthy of note (table 14). Without adding any net new schools, Catholic enrolment has increased tenfold, from 541 to 5,452 students, almost entirely through distributed learning. Islamic schools have doubled in count and increased in enrolment by two-thirds. There has also been considerable growth in Sikh schools, which were not observed in Allison and Van Pelt’s study but which have arisen in the intervening years. Jewish schools and enrolments have declined. It is possible that Jewish schools, like many Christian schools, took advantage of policy and funding changes to become part of the district (public) system as alternative schools.

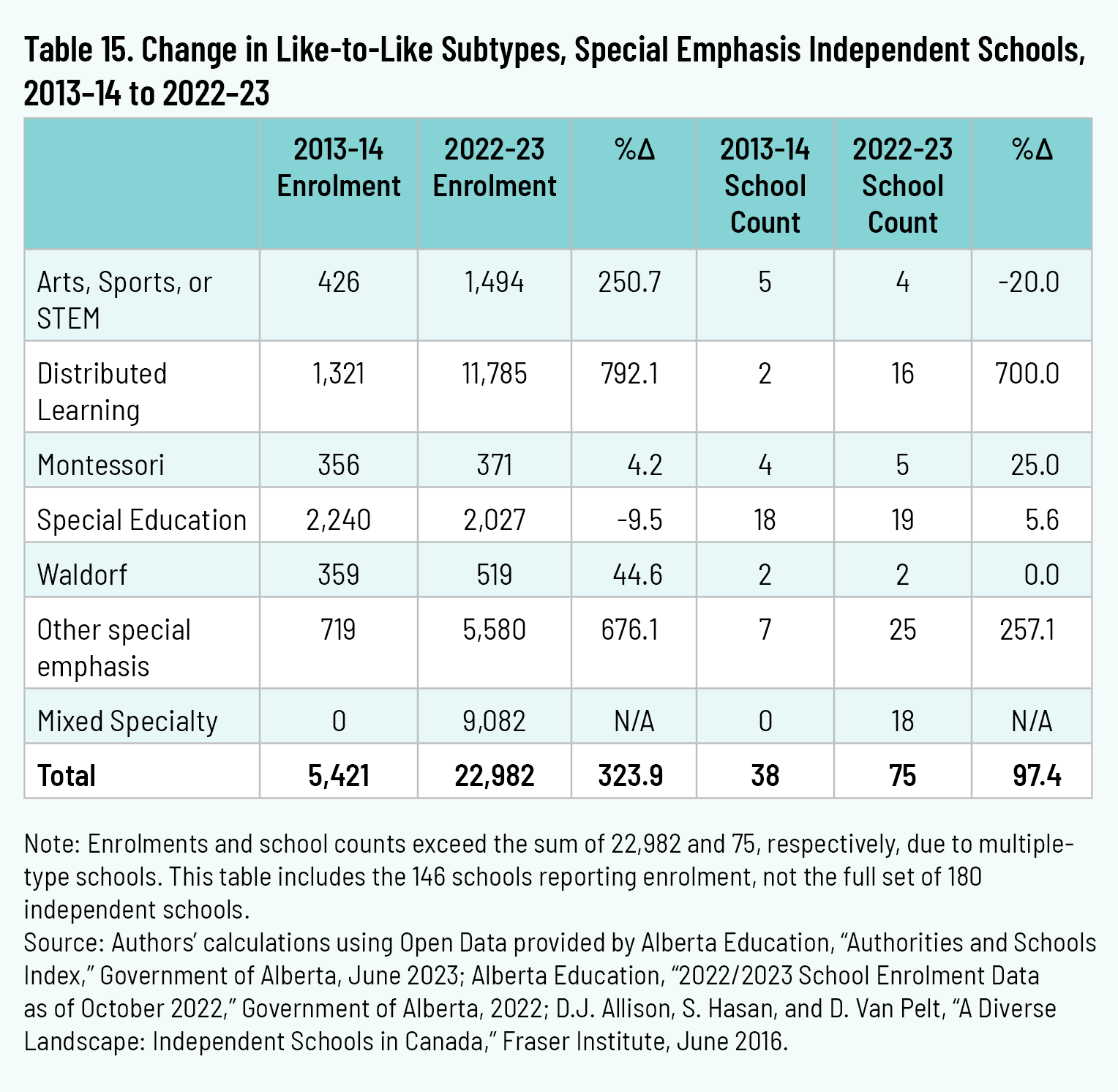

Change in School Count and Enrolment by Special Emphasis Subtype

As a whole, Special Emphasis schools have seen the largest growth in the sector. These schools have more than quadrupled their enrolment, from 5,421 to 22,982 students (table 15). Their number has also more than doubled, from thirty-eight to seventy-five schools. Distributed Learning schools have seen the greatest gains, increasing from two to sixteen schools, with nearly eightfold enrolment gains. Other Special Emphasis and Mixed Specialty schools have also experienced substantial growth, from a combined seven schools enrolling 719 students to forty-three schools enrolling 14,662 students. The increases in these categories suggest that there has been some increase in innovative approaches to education, for example, through Nature schools and Micro schools. The apparent decline in Special Education school enrolment may be due to the fact that it is now more common for schools of all kinds to serve students with special needs or neurodiverse learning styles.

Change in School Count and Enrolment by Urbanicity/Population Centre

A look at the change in school count and enrolment by population centre yields some interesting observations (table 16). Given that there is only one net new school, and that few schools have opened in recent years, it is unlikely that half of rural independent schools have closed and that medium population centres have doubled their count with new schools. What is more likely, given Alberta’s growing population, is that the overall population increased in these population centres. For example, a rural community of 800 residents increasing to 1,100 would become a small population centre. A town of 27,000 residents increasing to 32,000 would become a medium population centre. Further investigation is needed to confirm or reject this hypothesis.

Discussion

Several observations stand out from this research. First, despite the pluralism that exists across Alberta’s fully taxpayer-funded schools, some families still choose independent options for their children. The diverse approaches to education evidenced by the high numbers of Religious and Special Emphasis schools suggest that robust educational pluralism requires real options within the district systems as well as real options beyond them.

Second, as was the case in the earlier Ontario-based research, only a small proportion of the independent schools are of the Top Tier type. The view that independent schools tend to be “elite” schools is inaccurate. Seventy-five percent of all independent schools in the province enrol fewer than 300 students, and most of these are Religious and Special Emphasis schools. The small community-oriented school is typical of the sector.

Third, since 2013–14, just one net new independent school has been created in the province. This is in stark contrast to Ontario, where 491 net new independent schools were created during this period. What accounts for this difference? It cannot primarily be a matter of funding, since independent schools in Alberta can apply for public funding after one year of operation, and in Ontario no public funding is available. Perhaps the difference arises from the fact that with funding comes a degree of government regulation. It seems evident that the minimal regulation in Ontario is related to that province’s higher proportion of Credit Emphasis schools. Is the level of school regulation in Alberta perceived as too onerous to those who might wish to found Religious or Special Emphasis schools? On the other hand, Alberta Education appears to approve few applications to create new independent schools. For example, only a small number of the more than two dozen new-school applications was approved between 2015 to 2019. The reasons deserve further study.

Fourth, enrolment in independent schools has increased not due to new school starts but to existing schools becoming larger. The data presented in this report suggests that schools are becoming larger because schools are expanding their grade level offerings, and because as homeschool is growing, more students are enrolled in schools as supervised home education or shared-responsibility program students. As noted in the report, half of the enrolment in Special Emphasis schools is in the Distributed Learning subtype (where most of these homeschool students presumably are enrolled). To the extent that existing schools become larger, growth in the sector does not translate to an increase in pluralism understood as additional choices and options.

And finally, it is remarkable that close to three-quarters of the independent schools belong to a school association. Membership within school associations, which are an instrument of civil society, provides an additional layer of accountability beyond that of government regulation, and contribute to robust expressions of educational pluralism.

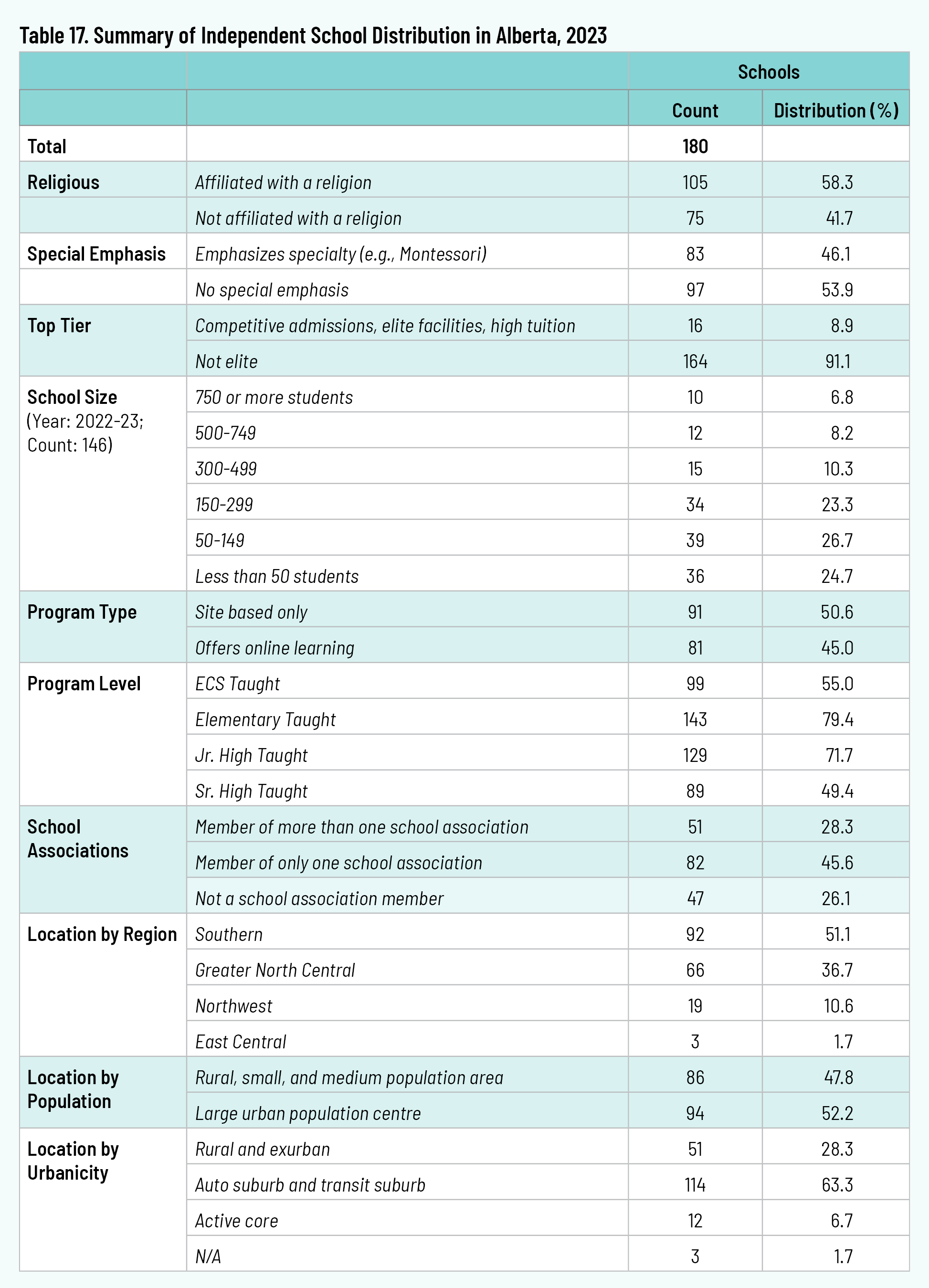

Table 17 summarizes the overall findings. Independent schools in Alberta serve an important and growing segment of its population. Alberta is a province committed to deep choice in its variety of fully funded school types. The government should continue to encourage the presence of meaningful pluralism through support of new and existing independent schools that meet requirements, so that Alberta families have access to options that best fit their education needs.

References

Alberta Education. “Boundary Maps.” Government of Alberta. https://education.alberta.ca/boundary-maps/provincial-maps/.

———. “Establishing an Independent (Private) School: Application Process and Requirements.” Government of Alberta, March 2024. https://open.alberta.ca/publications/establishing-an-independent-private-school-application-process-and-requirements.

———. “Outreach Programs.” Government of Alberta. https://www.alberta.ca/outreach-programs.

———. “School and Authority Information Reports.” Government of Alberta, June 2023. https://education.alberta.ca/alberta-education/school-authority-index/everyone/school-authority-information-reports/.

———. “School and Authority Student Population Data.” Government of Alberta, accessed October 2022. https://www.alberta.ca/assets/documents/educ-school-enrolment-data-2022-2023.xlsx.

———. “Shared Responsibility Program.” Government of Alberta. https://www.alberta.ca/shared-responsibility-program/.

Allison, D.J., S. Hasan, and D. Van Pelt. “A Diverse Landscape: Independent Schools in Canada.” Fraser Institute, June 2016. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/a-diverse-landscape-independent-schools-in-canada.

Basham, J.D., T.E. Hall, R.A. Carter, Jr., and W.M. Stahl. “An Operationalized Understanding of Personalized Learning.” Journal of Special Education Technology 31, no. 3 (2016): 126–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643416660835.

Bauer, S.W. “What Is Classical Education?” Well-Trained Mind, June 3, 2009. https://welltrainedmind.com/a/classical-education/.

Berner, A. “Good Schools, Good Citizens: Do Independent Schools Contribute to Civic Formation?” Cardus, June 2021. https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/good-schools-good-citizens/.

Canadian Council of Montessori Administrators. “CCMA Schools.” https://www.ccma.ca/ccma-schools/.

Clark, K.W., and R.S. Jain. The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Philosophy of Christian Classical Education. Camp Hill, PA: Classical Academic Press, 2013.

College Board. “AP Program.” https://ap.collegeboard.org/.

Converso, J.A., S.P. Schaffer, and I.J. Guerra. “Distributed Learning Environment: Major Functions, Implementation, and Continuous Improvement.” Learning Systems Institute, Florida State University, October 1999.

Duarte, J., and C. Robinson-Jones. “Bridging Theory and Practice: Conceptualisations of Global Citizenship Education in Dutch Secondary Education.” Globalisation, Societies and Education (March 6, 2022): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2022.2048800.

Gordon, D.L.A., and M. Janzen. “Suburban Nation? Estimating the Size of Canada’s Suburban Population.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 30, no. 3 (2013): 197–220. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43031005.

Hadim, H.A., and S.K. Esche. “Enhancing the Engineering Curriculum through Project-Based Learning.” Paper presented at the 32nd Annual Frontiers in Education Conference. Boston, MA: IEEE, November 6–9, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1109/FIE.2002.1158200.

Hernández-Ramos, P., and S. De La Paz. “Learning History in Middle School by Designing Multimedia in a Project-Based Learning Experience.” Journal of Research on Technology in Education 42, no. 2 (2009): 151–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2009.10782545.

Hunt, D., J. DeJong VanHof, and J. Los. “Naturally Diverse: The Landscape of Independent Schools in Ontario.” Cardus, 2022. https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/naturally-diverse/.

International Baccalaureate. “Find an IB School.” https://www.ibo.org/programmes/find-an-ib-school/.

———. “International Education.” https://www.ibo.org/.

Lounsbery, M.A.F., and T.L. McKenzie. “Physically Literate and Physically Educated: A Rose by Any Other Name?” Journal of Sport and Health Science 4, no. 2 (2015): 139–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2015.02.002.

McCarty, K. “Full Inclusion: The Benefits and Disadvantages of Inclusive Schooling; An Overview.” Azusa Pacific University, 2006. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED496074.pdf.

Moizumi, E. “Examining Two Elementary-Intermediate Teachers’ Understandings and Pedagogical Practices About Global Citizenship Education.” Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, 2010. https://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.item?id=MR72914&op=pdf&app=Library&oclc_number=1019483268.

National Research Council. Successful STEM Education: A Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.17226/13230.

Oxford, R.L., and C. Gkonou. “Interwoven: Culture, Language, and Learning Strategies.” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 8, no. 2 (2018): 403–26. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.2.10.

Patrick, S., K. Kennedy, and A. Powell. “Mean What You Say: Defining and Integrating Personalized, Blended and Competency Education.” International Association for K–12 Online Learning, 2013. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED561301.pdf.

Sayers, D.L. “The Lost Tools of Learning.” Hibbert Journal: A Quarterly Review of Religion, Theology, and Philosophy 46 (1948).

Srivastava, A., and S.B. Thomson. “Framework Analysis: A Qualitative Methodology for Applied Policy Research.” Journal of Administration and Governance 4, no. 2 (2009): 72–79. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14078/730.

Statistics Canada. “Census of Population, 2021.” September 12, 2023. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm.

———. “Dictionary, Census Population, 2016.” October 11, 2018. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/ref/dict/98-301-x2016001-eng.pdf.

Stirling, D.L. “Distributed Learning Environments.” December 8, 1997. http://www.stirlinglaw.com/deborah/DLE.htm.

Stufft, C.J. “Reading to the Rhythm: Integrating Music into Literacy Instruction.” English in Texas 45, no. 1 (2015): 21–26.

Timothy, T., T.S. Chee, L.C. Beng, C.C. Sing, K.J. Hwee Ling, C.W. Li, and C.H. Mun. “The SelfDirected Learning with Technology Scale (SDLTS) for Young Students: An Initial Development and Validation.” Computers & Education 55, no. 4 (2010): 1764–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.001.

Turcotte, M. “Life in Metropolitan Areas.” Statistics Canada, April 2014. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-008-x/2008001/article/10459-eng.htm.

UNESCO. “What Is Global Citizenship Education?” January 9, 2018. https://en.unesco.org/themes/gced/definition.

Van Pelt, D., and P.J. Mitchell. “Mapping Independent School Associations in Canada.” Cardus, September 2018. https://www.cardus.ca/research/education/reports/mapping-independent-school-associations-in-canada/.

von Heyking, A. “Alberta, Canada: How Curriculum and Assessments Work in a Plural School System.” Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, June 2019. http://jhir.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/62962.

Walker, K. “Fine Arts Education.” Education Partnerships, January 3, 2006. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED537918.pdf.

Wearne, E. “National Hybrid Schools Project.” Kennesaw State University, Georgia. https://www.kennesaw.edu/coles/centers/education-economics-center/national-hybrid-schools-project/.