Father Robinson and Holy Cross schools are part of the Greater Saskatoon Catholic School (GSCS) division, which consists of forty-three elementary schools and seven high schools. GSCS has an open enrollment policy, meaning that all students who choose Catholic education are welcome, including those who are not Catholic.

1

1

The funding model that allows this policy was challenged in April 2017 by a Court of Queen’s Bench ruling which held that The Constitution Act, 1867 does not provide a constitutional right to separate schools in Saskatchewan to receive provincial government funding respecting non-Catholic students. The Saskatchewan Catholic School Boards Association and the provincial government have appealed the decision. In the meantime, the government of Saskatchewan has invoked the

notwithstanding clause and indicated that it will continue to fund non-Catholic students in Catholic schools.

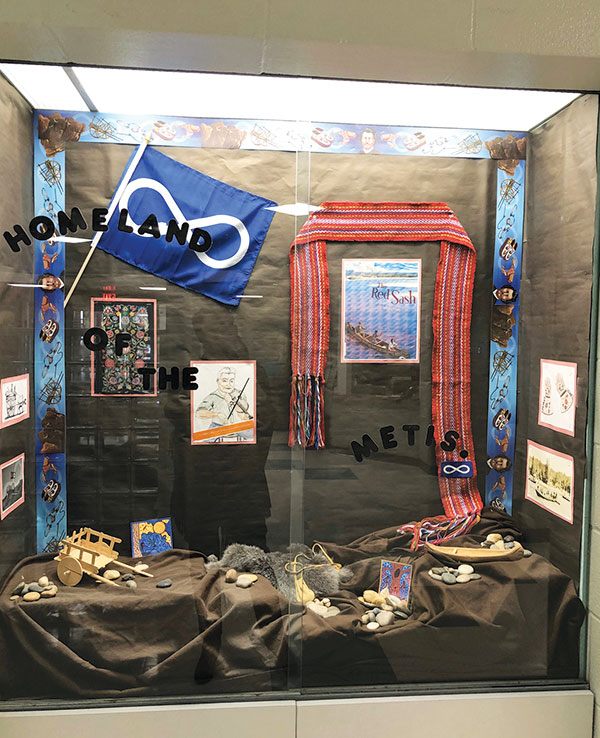

Both Father Robinson and Holy Cross are located on territory covered by Treaty 6 (signed by Cree, Assiniboine, and Ojibwa leaders and Crown representatives in 1876) and the Homeland of the Métis, near Cree, Dakota, Dene, Nakota (Assiniboine), and Nakawe (Saulteaux) First Nations lands (Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada 2019; Filice 2016).

Indigenous Perspectives and Christian Schools

Educators have an important role to play in pursuing truth and reconciliation among Indigenous peoples and Canadians. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls educators to “integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms” (clause 62) and “build student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy and mutual respect” (clause 63) (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). As Potlotek First Nation scholar Marie Battiste argues, “Integrating Indigenous knowledge into Canadian schools [balances] the educational system to make it a transforming and capacity-building place for First Nations students” (Battiste 2002, 29).

Christian schools may have a particular moral imperative to pursue Indigenous reconciliation given their commitment to Christian anthropology based on the dignity of the human person as well as the negative history between many Christians and Indigenous peoples. While much of the public conversation surrounding faith-based schools and Indigenous Peoples in Canada has not been positive, Father Robinson and Holy Cross are seeking to be agents of renewal and reconciliation through their efforts to respond to the calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Integration and Innovation in Action

GSCS leaders work with First Nations and Métis organizations to offer education from an Indigenous perspective to Indigenous and non-Indigenous students alike: “The knowledge, cultures and languages of FNMI [First Nations, Métis, and Inuit] families help us to develop learning programs that are part of all students’ growth, both FNMI and non-FNMI” (Greater Saskatoon Catholic Schools 2017a). Staff believe that students have become more well-rounded, accepting, appreciative, and knowledgeable of FNMI culture and its contributions to Canadian society through integrating Indigenous perspectives into their worldview.

Though neither Father Robinson nor Holy Cross are designated First Nations schools (schools for students living on reserve that are funded by the federal government and operated directly by First Nations [Government of Canada 2019]) or have large populations of Indigenous students, the schools were chosen for the research project because of their commitment to reconciliation. Indeed, staff at both schools do not view the non-FNMI majority as a barrier to change but rather as an “opportunity to build within these students the foundation and knowledge to create change and move toward healing and reconciliation.” 2 2 Unattributed quotations are from the survey responses. The case study is thus applicable to the many other schools in Canada without large populations of Indigenous students.

“The children of today, who are being educated about the story of Indigenous people in Canada, will become the voting citizens of tomorrow. Hopefully, they will have more accurate information, and fewer stereotypes, about our Indigenous fellow Canadians than previous generations.”

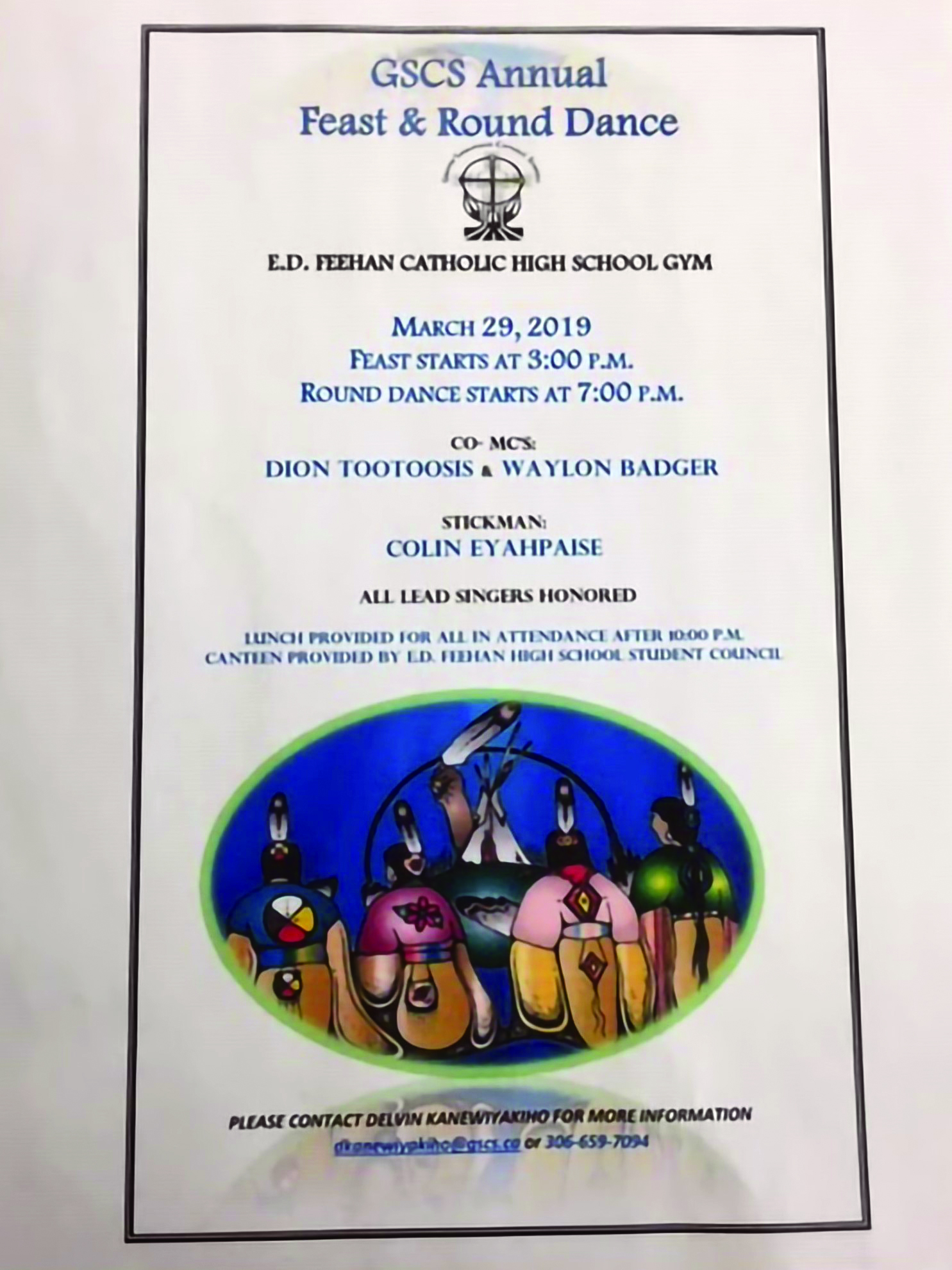

Father Robinson and Holy Cross, along with all other schools in the GSCS district, have access to a team of Indigenous education consultants. These specialists have established an in-school consultation schedule and are available to meet with teachers to co-plan and coteach lessons, locate authentic FNMI resources, and plan for thoughtful integration of FNMI content across all subjects. Consultants can invite knowledge keepers to the school to lead powwows, smudge ceremonies, sweats, drumming, and hoop dancing. This structure is intended to provide a consistent framework for access to supports in order to most effectively serve the needs and goals of students, teachers, and the school. The board office also sends guest speakers to provide support and encouragement to staff.

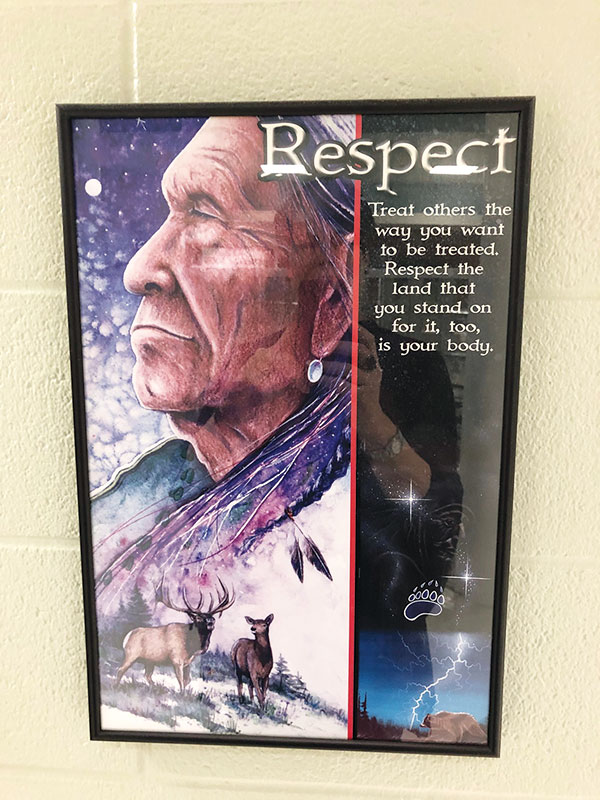

At Father Robinson, teachers include Indigenous content in a wide variety of subject areas: health class includes exploring the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Canada Food Guide; English classes read texts by Indigenous authors; and social studies students learn about First Nations and Métis medicine, treaties, and residential schools. Indigenous practices are integrated into the classroom beyond the curriculum as well: “Sharing circles are incorporated into religion time and, during dance and body breaks, different Métis dances are explored including the Seven Step and Jigging.” Students are also exposed to FNMI perspectives through experiential learning in drama, art, song, and dance; authentic Indigenous resources; and Indigenous guest speakers. Schoolwide initiatives like Orange Shirt Day, a day to remember the impact of residential schools, are part of a “First Nation Métis Inuit Content Learning Improvement Plan,” which the school developed in collaboration with the GSCS board as a guide for the implementation of Indigenous content. Permanent displays showcase Métis and First Nations artwork throughout the school.

Father Robinson uses a variety of additional methods and strategies to facilitate the integration of Indigenous content and pedagogy. The school’s growth plan designates FNMI content as one of its three main focus areas (alongside English and math); this arrangement encourages teachers to collaborate toward a school goal. Teachers note the need for access to up-to-date, teacher friendly resources and good resource people, implying that Father Robinson’s “library resources [and] supportive FNMI leadership team” are particularly useful.

“Through honouring and respecting Indigenous heritage, students seem to honour and respect their own heritage. Through reconciliation the students seem to understand the need to honour Indigenous people and all people, ourselves, our classmates, settlers, immigrants, our history and the worldviews of new immigrants and their countries as well.”

Holy Cross also integrates Indigenous content across subject areas. English classes include FNMI creation stories, novels, and short stories; one teacher describes connecting To Kill a Mockingbird with past and present FNMI experiences. Students study First Nations artists and learn Métis beadwork in art class; various FNMI traditions are used to interpret artwork, and Jerry Whitehead, a local Indigenous artist, has been invited to display his work around the school. Students are introduced to FNMI music and spiritual ceremonies in music and religion class, respectively. Holy Cross offers Indigenous-studies classes as well. Outside the classroom, Holy Cross teachers have regular discussions about treaties, the Indian Act, residential schools, reserves, reconciliation, and Indigenous culture. Sharing circles and medicine wheels are used to organize related topics during group discussions and brainstorming sessions. Numerous posters on the school walls call attention to Indigenous ways of knowing; medicine wheels are used as teaching tools in multiple classes to map and convey information to students; and every classroom receives a Métis flag. The school runs events such as an annual multicultural day and the blanket exercise, an experiential learning activity that teaches participants about the impact of colonization, which one teacher highlighted as “a moving and memorable experience for the students.” Some teachers take their students on outdoor education field trips to visit Wanuskewin, a provincial historic site that focuses on the Plains Indigenous people (Wanuskewin 2019), including an art teacher whose class received research-grant funding to work with Indigenous artist Leah Dorian.

In addition, Holy Cross has a partnership with the University of Saskatchewan, which provides the high school with expertise and financial support for FNMI students. Staff say this collaboration has helped broaden their understanding and equipped them with practical ways to “help educate students in FNMI content.” Holy Cross administration and staff are vigilant in acknowledging that they are on treaty land. The school’s goal to integrate Indigenous perspectives features in discussions of curriculum outcomes and influences professional development initiatives. The school uses Learning Sprints, an instructional initiative developed by GSCS that helps guide teachers to build on a “culturally responsive pedagogy,” which describes “teaching that recognizes all students learn differently and that these differences may be connected to background, language, family structure and social or cultural identity” (Hodson 2018; Ontario Ministry of Education 2013). GSCS also supplies resources for in-class instruction—“treaty kits,” for example, teach students about treaties made between Indigenous groups and the government. The library’s collection of Indigenous titles is available to all students and staff as well.

An Expanding Impact

Being able to incorporate a faith dimension into the curriculum has helped Father Robinson and Holy Cross adopt Indigenous content and pedagogy. One staff member from Holy Cross noted, “The important thing is that we meet Jesus in all we encounter, and the Indigenous content and pedagogy follow naturally from that understanding and appreciation.” Despite religious differences, the recognition that spirituality is part of a holistic education may give faith-based schools an advantage as they seek to integrate Indigenous perspectives: “It may be easier for us to include the spiritual aspects in our teaching as this is already a part of our culture.” Novalis (2018) argues that Christian educators can explore parallels to their faith in Indigenous spiritual traditions, such as stewardship of the natural world—connections that Father Robinson and Holy Cross have emphasized. Staff believe that by incorporating Indigenous worldviews into the curriculum they are upholding their Catholic Christian faith: “Our Christian belief of welcoming and being a good servant is an essential teaching of our Catholic faith.” Staff also believe that their integration of FNMI perspectives is making a positive contribution to the common good and future of Canada, shaping students to be more informed citizens.

Since examining different worldviews may be considered sensitive content, Father Robinson and Holy Cross staff are careful to inform parents of Indigenous cultural activities practiced at the school and invite their involvement. Several GSCS-division schools invite students to participate in the traditional Indigenous blessing ceremony of smudging, for example; school division policy requires that schools inform and obtain a signature of consent from parents prior to each student’s participation in the ceremony.

By embracing Indigenous content and pedagogy, Father Robinson and Holy Cross schools are making a significant impact not only on the school itself but also on the community at large. One teacher remarked, “Hopefully the fruits of our labour will have a lasting impact in the community as time goes by.” The schools’ efforts are also bringing an awareness about the deep wounds inflicted by residential schools. As students learn about the historical damage done to Indigenous communities, they can also pass this new knowledge on to their parents (Castellon 2017). A number of parents at Father Robinson and Holy Cross have embraced this new learning through participation in various school activities. The education students receive at Father Robinson and Holy Cross contributes to the good of the country as a whole, since learning about Indigenous history, as one teacher reflects, is important for every Canadian:

“I think the key to remember is that everyone is part of the community, no matter what race, religion, gender or views, and that there must be open, truthful, and informative dialogue about the issues and concerns of all Canadians. Indigenous history is Canadian history; we cannot separate the two or choose to overlook the impact that our historical relationships have on our current Canadian identity.”

Key Takeaways

- Educators have an important role in advancing reconciliation in Canada, including responding to the calls to action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

- Christian schools are included in the call to seek reconciliation, even schools that do not have large populations of Indigenous students.

- In order to ensure that Indigenous perspectives are integrated in an accurate and respectful way, it is important for schools to seek guidance from members of Indigenous communities.

- Indigenous perspectives can be integrated into all subject areas, both through including FNMI content in the curriculum and introducing students to traditional Indigenous practices.

- Schools can deepen students’ and staff’s appreciation of FNMI culture by showcasing the work of Indigenous artists.

- When introducing students to traditional Indigenous practices, schools should communicate with parents about their children’s participation in these activities, including providing them with information, obtaining their consent, and inviting their involvement.

- Learning about Indigenous perspectives helps students become more informed and conscientious members of their civic communities, equipping them to contribute to the common good.

References

Battiste, M. 2002. Indigenous Knowledge and Pedagogy in First Nations Education: A Literature Review with Recommendations. National Working Group on Education and the Minister of Indian Affairs. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education/24._2002_oct_marie_battiste_Indigenousknowledgeandpedagogy_lit_review_for_min_working_group.pdf.

Bergmark, U., and C. Kostenius. 2018. “Appreciative Student Voice Model—Reflecting on an Appreciative Inquiry Research Method for Facilitating Student Voice Processes.” Reflective Practice 19, no. 5:623–37.

Calabrese, R. 2015. “A Collaboration of School Administrators and a University Faculty to Advance School Administrator Practices Using Appreciative Inquiry.” International Journal of Educational Management 29, no. 2:213–21.

Castellon, A. 2017. Indigenous Integration: 101+ Lesson Ideas for Secondary and College Teachers. Victoria: Tellwell.

Filice, Michelle. 2016. “Treaty 6.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/treaty-6.

Gordon, S.P. 2016. “Expanding Our Horizons: Alternative Approaches to Practitioner Research.” Journal of Practitioner Research 1, no. 1: article 2.

Government of Canada. 2019. “First Nations Education Transformation.” https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/ eng/1476967841178/1531399315241.

Greater Saskatoon Catholic Schools. 2017a. “First Nations, Métis & Inuit Self-Declaration Form.”https://www.gscs.ca/studentsandfamilies/schools/DOM/Forms/FNMISelfDeclarationBrochure.doc.

———. 2017b. “Father Robinson School Mission.” https://www.gscs.ca/studentsandfamilies/schools/RBI/Pages/SchoolMission.aspx.

———. 2017c. “Holy Cross High School Mission.” https://www.gscs.ca/studentsandfamilies/schools/HCH/Pages/SchoolMission.aspx.

Hodson, L. 2018. Personal communication. December 15.

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. 2019. “First Nations Map of Saskatchewan.” https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100020616/1100100020653.

Novalis. 2018. Indigenous Spirituality and Catholicism: Fostering Healing and Reconciliation. We Are All Children of God. Toronto: Novalis.

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2013. “Culturally Responsive Pedagogy: Towards Equity and Inclusivity in Ontario Schools.” Capacity Building Series: Secretariat Special Edition 35. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/CBS_ResponsivePedagogy.pdf.

Ryan, F.J., M. Soven, J. Smither, W.M. Sullivan, and W.R. Van Buskirk. 1999. “Appreciative Inquiry: Using Personal Narratives for Initiating School Reform.” The Clearing House 7, no. 3:164–67.

Stavros, J., L. Godwin, and D. Cooperrider. 2015. “Appreciative Inquiry: Organization Development and the Strengths Revolution.” In Practicing Organization Development: A Guide to Leading Change and Transformation, edited by William Rothwell, Roland Sullivan, and Jacqueline Stavros, 96–115. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley

Tittle, M.E. 2018. Using Appreciative Inquiry to Discover School Administrators’ Learning Management Best Practices Development. Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. Minneapolis: Walden University.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf.

Wanuskewin. 2019. “Group Tours.” https://wanuskewin.com/discover/tours/.

Waters, L., and M. White. 2015. “Case Study of a School Wellbeing Initiative: Using Appreciative Inquiry to Support Positive Change.” International Journal of Wellbeing 5, no. 1:19–32.

Zepeda S.J., and J.A. Ponticell. 2018. The Wiley Handbook of Educational Supervision. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.